Clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe some of the complexities and uncertainties of clinical practice

• Understand what is meant by the term clinical reasoning

• Be aware of the different perspectives about the concept of ‘evidence’

• Understand the importance of clinical experience for evidence-based practice

• Understand what is meant by the term professional practice

• Explain how clinical reasoning can be used to integrate information and knowledge from the different sources that are required for evidence-based practice

• Understand what is meant by critical reflection and how it might support evidence-based practice

Evidence-based practice aims to improve outcomes for patients.1 This goal appears uncontentious and would generally be accepted by a range of stakeholders in health. Patients, health professionals, funding bodies and policy makers all share in this aim. However, a range of issues make it problematic to uncritically adopt an evidence-based practice approach, and the complexity of the problem becomes clearer when we question how best to achieve optimal health care.

Patient outcomes are dependent on a range of factors, such as:

• the nature of the patient's health problem

• the types of services that are available to and accessible by the patient

• the practices of the health professionals working in those services

• the nature and quality of the interaction between the patient and the health professional

• the attitudes of the patient towards the services offered

• the patient's own conceptualisation of the health problem

• the ease with which any service recommendations that are made can be carried out by patients within the broader context of their lives.

This list illustrates the complexity of the issue of improving patient outcomes. If all of these issues interact together to affect the health outcomes for a particular patient, where should planned improvements focus? Will a change in one factor be sufficient to obtain the desired result, or do factors need to be considered in an integrated way? Health professionals face these kinds of questions on a daily basis, as well as the ever-present question, ‘What can and should I do in this specific situation?’

Professional practice is complex and health professionals need to consider the range of factors that affect patient outcomes when planning and delivering services. They are required to make decisions about what services they can and should offer, given the particular needs of, and circumstances surrounding, the individual patient and the broader organisational and societal context. Making these kinds of decisions requires complex thinking processes, as the ‘problem’ or situation about which decisions have to be made is often poorly defined and the desired outcomes are often unclear.2 This thinking process is often referred to as clinical or professional reasoning, decision making, or professional judgment.

Health professionals need to use their clinical reasoning to gather and interpret different types of information and knowledge from a range of sources to make judgments and decisions regarding complex situations under conditions of uncertainty. In addition to the logical decisions that health professionals make, they also have to make ethical and pragmatic ones. They have to ask themselves questions like: ‘What is the most effective thing I could do?’, ‘What is most likely to work in this situation?’, ‘What is the patient most likely to accept and do?’ and ‘What should I do (ethically) in this situation?’.

This chapter aims to explore the relationship between clinical reasoning and evidence-based practice. As you have seen throughout this book, evidence-based practice is a movement in health that aims to improve patient outcomes by supporting health professionals to incorporate research evidence into their practice. Evidence-based practice also recognises that research evidence alone is not sufficient for addressing the complex nature of professional practice and that the ability to integrate different types of information and knowledge from different sources is also required. Therefore, to practise in an evidence-based way, health professionals need to integrate research with their clinical experience, an understanding of the preferences and circumstances of their patients and the demands and expectations of the practice context. Clinical reasoning is the process by which health professionals integrate this information and knowledge.

In this chapter, we explore the notion of evidence-based practice and the roles that different forms of knowledge and information play in providing evidence for practice; and we highlight how the concept of practice should be viewed as being embedded within particular contexts. We also explore the clinical reasoning processes that occur within practice and provide some brief suggestions for you to consider when critically reflecting on your own practice from the perspective of making it evidence-based.

The evidence-based practice movement's concept of evidence

The assumption underpinning the perceived need for an evidence-based practice is that basing practice on rigorously produced information (often referred to as data) will lead to enhanced patient outcomes. Given the complex range of factors that can affect patient outcomes, how can we be sure that basing our practice on such evidence will improve them, and what kinds of information or knowledge constitutes appropriate and sufficient evidence? These are important questions for health professionals to ask.

The first question about whether basing practice on evidence does lead to better patient outcomes has been examined widely in relation to specific interventions and specific outcomes.

The second key question is: what constitutes evidence? As we saw in Chapter 1, evidence-based practice across the health professions evolved from its medical counterpart, evidence-based medicine, and as a consequence, many of the assumptions of medicine have been adopted in evidence-based practice. In the definition of evidence-based practice by Sackett and colleagues3 that was examined in Chapter 1, the term ‘current best evidence’ was introduced as the criterion for evidence. Predictably, clarifying the nature of ‘best’ evidence has become the central concern of the evidence-based practice and evidence-based medicine movements. As the empirico-analytic paradigm is the dominant philosophy that underpins medicine, this also became the assumed perspective of the evidence-based practice movement.

The empirico-analytic paradigm is also known as the scientific paradigm or the empiricist model of knowledge creation. According to Higgs, Jones and Titchen,4 this paradigm ‘relies on observation and experiment in the empirical world, resulting in generalisations about the content and events of the world which can be used to predict the future’ (p. 155). From the perspective of the empirico-analytic paradigm, the best form of evidence is that produced through rigorous scientific enquiry. It has been assumed that such rigour can be achieved best through the methods of research, especially quantitative research.5

Therefore, information and knowledge generated from research is the concept of evidence that is used by the evidence-based practice movement and is the approach taken throughout this text. Many people take this assumption for granted, and this is highlighted by the fact that some professions use the clarifying term ‘research-based practice’ rather than ‘evidence-based practice’.

The position that scientific knowledge is the sole key to evidence has been questioned by a number of writers5–7 who have argued that research evidence alone is not sufficient for addressing the complexities of professional practice and that the ability to generate and integrate different types of evidence from different sources is also required. While the evidence-based practice movement is centred on evidence derived from rigorously conducted research, early definitions of evidence-based medicine did clearly emphasise that, to practise in an evidence-based way, professionals need to integrate research findings with practical knowledge derived from their clinical experience and an understanding of the preferences and circumstances of their patients.

In some ways, the assumption that ‘evidence equals research findings’ has been problematic for the evidence-based practice movement and has probably contributed to a strong division between those who align themselves with the evidence-based practice movement and those who oppose it. Critics of evidence-based practice argue that there are problems with the production, relevance and availability of research evidence and that it has limited capacity to address the problems of practice and enhance decision making in the context of complex practice and life situations.8 Examples of criticisms include: that the research that is undertaken is often dependent on funding and, therefore, factors other than need and importance can influence what is researched; that the research undertaken can reflect what is easier to measure more than what is important to understand or most important to professional practice; and that, often, research findings are not presented in forms that are easily accessible to health professionals.

Perhaps the situation is summed up best by Naylor9 who, in relation to evidence-based medicine (and his comments are just as relevant to evidence-based practice), stated that ‘A backlash is not surprising in view of the inflated expectations of outcomes-oriented and evidence-based medicine and the fears of some clinicians that these concepts threaten the art of patient care’ (p. 840). Exploring the assumptions about what is meant by the notion of ‘evidence’ can be a good start to examining what evidence-based practice is, and we do this in the next section.

Evidence of what?

What is evidence? The Heinemann Australian Student's Dictionary defines evidence as ‘anything which provides a basis for belief’10 and the Macquarie Dictionary defines it as ‘grounds for belief’.11 In this context, belief refers to acceptance of the credibility or substantiation of a position or argument, for instance providing support for a course of action. Using this definition, evidence would be information or knowledge that supports some sort of belief; and an evidence-based practice, therefore, would be a practice that is based on such information and knowledge. But whose beliefs are referred to? Is it an individual health professional's beliefs, the beliefs of a particular health profession or the beliefs that underpin a particular health service or model of service delivery? Is it the beliefs of those receiving care from a particular service or those funding or providing the service? Are the beliefs of all of these stakeholders in health the same and of equal value?

These questions highlight the argument that the types of information and knowledge that are seen as potentially appropriate to use as evidence for health practice can vary among different stakeholders. For example, if a service measures patient outcomes in terms of reducing (or eliminating) impairments, then it is information about the effectiveness of interventions in reducing impairments that will be used most often as evidence, regardless of the functional and practical implications of using those interventions. However, people using health services might employ other criteria to measure outcomes. For example, they might value services that make an appreciable difference to their health experience, are accessible (physically and financially) and use interventions that are easy to implement within their own life contexts. Healthcare funding bodies might be most concerned with value-for-money and might seek information that substantiates the cost-effectiveness of interventions or services. That is, they might only look favourably on interventions and service provision models that have both evidence to support the effectiveness of the intervention in improving patient outcomes and an acceptable financial cost.

From the perspective of the empirico-analytic paradigm

As explained in the previous section, the evidence-based practice movement has primarily taken its understanding of evidence from the empirico-analytic paradigm that underpins the assumptions of medicine. This paradigm aims to develop a knowledge base generated from a positivist perspective about ‘reality’ or ‘how the world is’ in which the world is taken to be observable (often with the assistance of technology), and information that is valued as knowledge is reliably generated and reproducible. In this perspective, to be dependable as evidence of reality (including how people's health responds to intervention), research data need to be free of bias when collected, the potential effects of the information collection process on the phenomena needs to be minimised and any changes observed must be able to be reliably attributed to particular factors or variables.

To make the empirico-analytic concept of best evidence explicit, a number of hierarchies have been developed, based on the methodology that is used to generate research data. In Chapter 2 the authors explored the hierarchies and levels of evidence for questions about intervention, diagnosis and prognosis in detail. Developing levels of evidence was a strategy used to establish the degree to which information and research findings could be trusted as ‘evidence’. For example, the top two levels of evidence in the hierarchy for intervention effectiveness are randomised controlled trials and their systematic reviews. As we saw in Chapter 4, randomised controlled trials (individual and systematically reviewed) generate knowledge that is considered to have a high degree of validity. By eliminating potential bias and controlling for variables that might influence the outcome, the confidence that any observed change can be attributed to one particular factor is very high. Therefore, in the empirico-analytic paradigm, this study design represents the most trustworthy type of research-generated knowledge to use as ‘evidence’.

Understanding the origins of the evidence-based practice movement in the empirico-analytic paradigm helps to explain its assumption that ‘evidence equals research findings’ and its emphasis on quantitative research methods. However, within the evidence-based practice movement, there are calls to acknowledge the value of other types of research methods such as qualitative research,12 but acceptance of methods other than quantitative research is at times still contested (although acceptance is growing, as explained in Chapters 10 and 12). As the imperative to identify ‘current best evidence’ remains a core value of the evidence-based practice movement, determining ways to assess the quality of such research remains a central endeavour (to ensure that it is ‘best’ evidence). Concern for the development and identification of critical-appraisal tools and strategies of metasynthesis of qualitative research (like the systematic review of quantitative research) are examples.

While the empirico-analytic paradigm focuses on generating knowledge through the rigorous scientific methods with which research is often associated, other stakeholders might value other types of knowledge as evidence. The sections that follow explore some of the other types of information and knowledge that are valued as evidence on which to base practice. As we will discuss later in the chapter, the professional's task of integrating these different types of ‘evidence’ in order to make practice decisions can be difficult.

From the perspective of technical rationality

Technical rationality is a second approach that addresses the type of information that is considered as appropriate evidence for professional practice. This approach aims to improve patient outcomes by regulating practice in order to enhance its efficiency and cost-effectiveness. Schön13 explained that, from the perspective of technical rationality, professional activity involves ‘instrumental problem solving made rigorous by the application of scientific theory and technique’ (p. 21). The major elements of this definition are problem solving and the rigorous use of scientific theory and technique. Whereas the empirico-analytic approach emphasises the trustworthiness of information in representing phenomena, this approach focuses on the problem solving of health professionals. Therefore, a major difference between these two approaches is that the former centres on the quality of the information whereas the latter targets the process of using the information.

From a technical rationalist perspective, human reasoning and judgment is understood in health care as problem solving, which requires the framing and definition of a problem and the search for a solution within a defined problem space. From this approach, efficiency and cost-effectiveness can be improved by providing tools that support the problem-solving process and minimise the likelihood of reasoning errors. As the technical rationalist approach values the rigorous use of the scientific method and technique, information that is generated using this method is incorporated into routines and procedures that aim to lessen and support the professional judgment required. The influence of technical rationality on health care is evident in the use of clinical pathways, protocols, decision trees and other tools that aim to systematise practice decisions. For example, the typical path to be taken by a health professional is clarified when a standard problem definition (often based on a medical diagnosis) can be used. Decision trees work in this way.

A major aim of using reasoning tools and research evidence is to reduce reasoning errors and the potentially biasing effects that can come from clinical opinions. An example of this type of bias is that health professionals can overemphasise the effectiveness of their own interventions because they might only see the short-term effects of the intervention. In addition, they might be overly influenced by situations and outcomes that they have access to, while potentially being unaware of or undervaluing other possibilities (such as interventions offered by other health professionals). In contrast, clinical protocols and research findings are generated from data that are gathered from a broader range of sources. For example, protocols are often developed using information such as research evidence, broader trends in patient outcomes or statistics about adverse incidents, epidemiological trends in population health and patients' opinions and experiences.

The technical rationalist approach shares a similar definition of evidence with the empirico-analytic approach. Both approaches value information that is generated using rigorous scientific methods and consider it to be appropriate evidence upon which to base clinical practice. While they share a concern for effectiveness, they often differ in relation to cost-effectiveness. In the empirico-analytic approach it might be argued that an effective intervention is essential, regardless of the cost. A technical rationalist approach would also include as evidence outcomes such as the reduction of health service costs and adverse incidents that occur during service delivery. However, a criticism of the technical rationalist approach is that it fails to give due attention to the complexity of professional practice and the individual nature of patient experience.14 This criticism is derived from the argument that the problems of professional practice are both specific and varied, which makes it impossible to develop protocols and procedures to cover the variety of situations that health professionals face.

What information helps health professionals to address the dilemmas of their practice?

A third approach to the matter of what constitutes evidence is to consider the question, ‘What information helps professionals to address the specific and varied dilemmas of their practice?’ Health professionals use judgment to deal with the complexity of professional practice,15 which relies on their clinical or professional expertise. The concept of professional expertise is central to the evidence-based practice process. This is illustrated in Sackett and colleagues' 19963 definition of evidence-based medicine that was presented in Chapter 1. The beginning of this definition of evidence-based medicine, pertaining to the judicious and conscientious use of research evidence, is well known. However, the section that follows has been quoted infrequently when definitions of evidence-based medicine (or practice) are presented. It reads:

The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgement that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experiences and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients' predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care. (p. 71)

As was pointed out in Chapter 1, this definition makes it clear that an evidence-based practice requires professional expertise, which includes thoughtfulness and compassion as well as effectiveness and efficiency.

Socio-cultural theories of learning suggest that professional expertise is developed through interaction with communities of practice.16,17 Health professionals learn the practices, activities and ways of thinking and knowing of their profession through participation in the community of practice. Expertise develops ‘as an individual gains greater knowledge, understanding and mastery’ (p. 24)17 in their practice area.

The work of Dreyfus and Dreyfus18 has been widely used to understand the concept of professional expertise developing with experience. The different ways that professionals think as they gain experience have been characterised into five stages, namely: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient and expert. Essentially these five stages reflect a movement from a practice that is based on context-free information and generalised rules to a sophisticated and ‘embodied’ understanding of the specific context in which the practice occurs. While the earlier stages focus on the application of generalised knowledge, in the proficient and expert stages health professionals are able to recognise (often subtle) similarities between the current situation and previous ones and use their knowledge of the previous outcomes to make judgments about what might be best in the current situation.

Professional expertise is difficult to quantify, as it is partly determined by the understandings that are shared by members of the community of practice. For example, Craik and Rappolt1 selected health professionals who were ‘deemed by their peers to be educationally influential practitioners’ as a criterion for inclusion into their research study of ‘elite’ practitioners. In nursing, expertise has been associated with holistic practice, holistic knowledge, salience, knowing the patient, moral agency and skilled know-how.19 Fleming20 reported that occupational therapists described expert practitioners (on videotapes) as appearing ‘elegant and effortless’ (p. 27). Jensen and colleagues21 developed a grounded theory of expert practice in physiotherapy and proposed that expertise in physiotherapy is a combination of multidimensional knowledge, clinical reasoning skills, skilled movement and virtue and that all four of these dimensions contribute to the therapist's philosophy of practice. It appears that members of a community of practice are able to recognise expertise, even though it involves unstated and embodied knowledge, skills and attributes that can be difficult to quantify.

As professionals often have to make decisions about what action to take with a particular patient in a particular organisational context, appropriate information could be conceptualised as including health professionals' memories of previous experiences and their specific outcomes. This is not to suggest that expert health professionals no longer use knowledge that is generated from research. Professional communities of practice have codes of ethics that usually include the need to maintain up-to-date knowledge of the field, and some professional bodies require members to undertake formal accreditation processes. Health professionals meet this ethical requirement through a range of activities such as attending conferences and workshops, reading professional journals, sharing this information with one another and discussing cases and experiences with one another. All of these activities can increase professional knowledge through exposure to findings from systematic research as well as expanding practice knowledge through experiential learning. Thus, the use of both knowledge that is generated from research and knowledge that is generated from practical experience is important for health professionals to be more able to undertake practice that is based on a rich evidence base.

Considering evidence from the patient's perspective

A fourth approach is brought into focus when we ask the question, ‘What is going to make the biggest difference to my patient’s life and health?’ This question helps to turn our attention to the patient's perspective. The definition of evidence-based medicine by Sackett and colleagues,3 quoted earlier in the chapter, includes the ‘thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care' (p. 71). Patients seek professional services because they need something that they cannot obtain in other ways. Professional services often come at substantial financial costs (and other costs such as time and effort) to patients. Attending to patients' predicaments, rights and preferences requires a developed ability to understand people, both as individuals and as members of groups within the overall population. Examples of understanding preferences and rights include giving patients choices in relation to interventions (that is, considering their preferences) and understanding and advocating for the rights of marginalised people to participate in social roles such as work. Understanding ‘predicaments’ requires the ability to imagine patients within the context of their living situations and social roles (not just the service contexts in which they are seen). For example, a health professional might have to consider the need for support from a patient's carer, the logistics of whether a patient is able to follow an intervention recommendation when the patient returns to daily life, and the opportunities for social participation that he/she has.

While patients expect health professionals to offer them services that will be effective, they also expect them to listen to their concerns and validate their experiences of health. Therefore, in addition to the effectiveness of the interventions, patients might seek ‘evidence’ of a health professional's interpersonal skills (e.g. a professional's ability to listen to their concerns), ‘value for money’ and the accessibility (physical and temporal) of the services that are being offered. Patients might seek this kind of information from sources such as the internet; friends, relatives and neighbours; and/or another trusted health professional. The importance of health professionals being able to communicate effectively with their patients was discussed in Chapter 14.

Evidence of what? A summary

In summary, asking the question ‘Evidence of what?’ can emphasise the fact that different stakeholders seek different types of information. People who work from an empirico-analytic paradigm are likely to seek information that is accepted as reliable representations of the world. Starting from this position, they are likely to value one kind of information (research findings) over other types of information, as illustrated by the established hierarchies of evidence. People who work from a technical rationalist perspective are most likely to seek information that provides a combination of evidence of efficiency and cost-effectiveness and will aim to use this information to develop tools and strategies to standardise practice according to what is considered best practice. Health professionals are most likely to value and seek information that provides evidence to support the decisions that they need to make about what they, as a member of a specific health profession in a particular organisational context, should offer a certain patient, given his or her life circumstances. Finally, patients are most likely to value and seek information that provides evidence of services and health professionals that offer effective, accessible, value-for-money interventions that they are likely to be able to incorporate into the context of their daily life.

All of these different perspectives are important when considering what an evidence-based practice might look like for health professionals, because they highlight the complexity of professional practice. Health professionals are influenced by and need to consider in their practice all of the different types of knowledge and the different types of information or ‘evidence’ that different stakeholders might consider relevant and valid. Using information that can be ‘trusted’ is a key concern of the evidence-based practice movement and will remain so as the movement explores a broader base upon which to make practice decisions.

In 2000, Sackett and colleagues22 provided a more succinct definition of evidence-based medicine that emphasised the complexity of the task that faces health professionals in striving to create and sustain a practice that is evidence-based. The definition succinctly stated that the process of evidence-based medicine requires ‘the integration of best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values’ (p. 1). To understand this process of integration, it is important to contextualise professional practice as requiring art, science and ethics. In the following section, we explore this process of integration.

Integrating information and knowledge: the forgotten art?

Current conceptualisations of evidence-based practice define it as a process that requires the integration of information from different sources. However, an understanding of how such integration occurs is still evolving. As discussed, much of the early attention of the evidence-based practice movement centred on the nature of evidence that is appropriate for health practice (mainly research evidence), and little systematic investigation was undertaken into how health professionals integrate knowledge and information from different sources such as research, clinical expertise, patient values and preferences, and the practice context. Conceptualising evidence-based practice as a process of integration requires a focus on the activities of health professionals. This section of the chapter will explore the nature of professional practice.

Health professionals provide services to their patients. They think and act within particular contexts, which have been established to provide a particular type of service, and remain accountable to their patients, employers and funding bodies. Health professionals also belong to particular professional groups or communities of practice. Therefore, professional practice needs to be understood within its social, organisational and professional contexts.

Professional practice has been described as a dynamic, creative and constructive phenomenon that flows constantly, like a river that shapes and is shaped by the landscape over which it flows.23 It is more than just a rational or routine practice. It requires the interaction between professions and patients and among professionals from different disciplines, as well as ethical and professional behaviour. As Fish and Higgs24 have stated, ‘as responsible members of a profession, [the] role [of health professionals] is precisely to argue their moral position, utilise their abilities to wear an appropriate variety of hats on different occasions with proper transparency and integrity and exercise their clinical thinking and professional judgement in the service of differing individuals while making wise decisions about the relationship between the privacy of individuals and the common good’ (p. 21).

These descriptions illustrate the complexity of professional practice. It is not just a problem-solving exercise (as technical rationalists might argue), although it requires problem solving. It is not just a process of applying theories and research-generated knowledge to practice (as an empirico-analytic approach emphasises), although these are vital in guiding practice. It includes the fulfilment of role expectations, professional judgment, ethical conduct and the delivery of patient-centred services. As Coles15 has stated, ‘professionals are asked to engage in complex and unpredictable tasks on society’s behalf, and in doing so must exercise their discretion, making judgements’ (p. 3). Professional practice requires systematic thinking, social and contextual understanding, deep listening, good communication and the ability to deal creatively and ethically with uncertainty. Examples of the uncertainty of medical practice that have been described25 include uncertainties about diagnosis, the accuracy of diagnostic tests, the natural history of diseases/disabilities and the effects of interventions on groups and populations. Each health profession has its own complexity and areas of uncertainty.

Health professionals need to use their judgment to make decisions about the best course of action to take under conditions of uncertainty. Part of the complexity is dealing with different and often competing understandings from a variety of data and knowledge sources and considering the individual nature of patient circumstances, needs and preferences. Professional practice is an ethical endeavour tailored to the individual patient that requires the credible use of theory and research, good judgment and problem solving and the ability to implement protocols and procedures. Integrating information from research, clinical expertise, patient values and preferences, and information from the practice context requires judgment and artistry as well as science and logic.

Strategies for combining science and art in practice are embedded in the way that health professionals think about their work. For example, in reference to occupational therapists, it has been stated that ‘when occupational therapists refer to the paired concepts of art and science, they express their moral dissatisfaction with being constrained by either. In isolation, art somehow seems too soft and unquantifiable and science too hard and unyielding’ (p. 482).26 While science is generally associated with rigour, reliability and predictability, artistry is associated with judgment and being able to deal with unpredictability. In Sackett's 1996 definition of evidence-based medicine,3 artistry is evident in the reference to ‘thoughtful identification and compassionate use’ of information that pertains to a particular patient. While various health professions emphasise art and science to different degrees, they all appear to accept that a balance of these approaches is required for professional practice.

Professional practice could be characterised as reasoned action, as it requires both knowing and doing. The concept of ‘art and science’ highlights that different types of knowledge are required for health professionals to undertake such reasoned action. Three types of knowledge that are required for practice can be described as:27

• Propositional knowledge, also known as theoretical knowledge, is an explicit and formal type of knowledge that is generated through research and scholarship and is associated with knowing ‘what’. This type of knowledge is often thought of as ‘scientific knowledge’ and has been emphasised in the main conceptualisation of evidence-based practice to date.

• Professional craft knowledge refers to knowing ‘how’ to carry out the tasks of the profession. It is often associated with the idea of an ‘art’ of practice and includes the particular perspectives that characterise each profession.

• Personal knowledge refers to an individual health professional's knowledge about his or her self in relation to others. This type of knowledge is important for professional practice as the relationships that health professionals build with their patients are often central to that practice.

The last two types of knowledge above ‘may be tacit and embedded either in practice itself or in who the person is’ (p. 5)23 and have been referred to collectively as ‘non-propositional’ knowledge.

Different types of knowledge can be gained from different sources. The definition of evidence-based practice that was explained in Chapter 1 and shown in Figure 1.1 included four sources: research, clinical expertise, the patient's values and circumstances, and the practice context. The practice context, which does not occur in any of Sackett's definitions3,22 as a knowledge source, provides important information about the local context.5 This source draws attention to the context-specific nature of professional practice, to which insufficient attention has been paid historically when conceptualising a practice that is based on evidence. Health professionals need to know what and how things work in a particular context (relating to both the setting and the patient). Taken together, these four sources of knowledge provide objective, experiential and contextual information from researchers, health professionals and patients.

The complexity of professional practice becomes evident if you consider that it requires the ability to obtain and use different types of information from a range of sources; to meet the demands of particular practice environments; to fulfil roles consistent with the perspectives of the professional communities of practice to which the health professional belongs; and to consider the predicaments, preferences and values of individual patients. Thus, the creation of a practice that is ‘evidence-based’, for the purpose of improving patient outcomes, is equally complex. ‘Evidence’ and ‘practice’ are both important for understanding evidence-based practice. The study of clinical reasoning highlights one aspect of practice. As this investigation was initiated by medicine, the term clinical reasoning was used. However, as many of the settings within which various health professionals work are not considered ‘clinical’, the term professional reasoning or professional decision making has also been used.

Approaches to clinical reasoning

Higgs28 defined clinical reasoning (or practice decision making) as:

a context-dependent way of thinking and decision making in professional practice to guide practice actions. It involves the construction of narratives to make sense of the multiple factors and interests pertaining to the current reasoning task. It occurs within a set of problem spaces informed by practitioners' unique frames of reference, workplace contexts and practice models, as well as by patients or patients' contexts.

It utilises core dimensions of practice knowledge, reasoning and meta-cognition and draws upon these capacities in others. Decision making within clinical reasoning occurs at micro-, macro- and meta-levels and may be individually or collaboratively conducted. It involves the meta-skills of critical conversation, knowledge generation, practice model authenticity, and reflexivity. (p. 1)

Earlier approaches to the study of clinical reasoning were influenced by investigations into artificial intelligence, and conceptualised clinical reasoning as a purely cognitive process. These emphasised the iterative process of obtaining cues or information about the clinical situation, forming hypotheses about possible explanations and courses of action, interpreting information in light of these hypotheses and testing them. This process is referred to as hypothetico-deductive reasoning. Beyond this, Higgs' definition28 emphasises that clinical reasoning is a process that involves cognition, meta-cognition (that is, the process of reflective self-awareness) and interactive and narrative ways of thinking.

The work of Higgs and Jones29 presents a current approach to clinical reasoning. They broadly categorised approaches to clinical reasoning as cognitive and interactive. Table 15.1 outlines the main types of thinking that health professionals use. The wide range of clinical reasoning approaches presented in this table is related to the following factors:

TABLE 15.1:

Summary of clinical reasoning approaches

| Model | Description |

| Hypothetico-deductive reasoning34–36 | The generation of hypotheses based on clinical data and knowledge and testing of these hypotheses through further inquiry. It is used by novices and in problematic situations by experts.37 |

| Pattern recognition38 | Expert reasoning in non-problematic situations resembles pattern recognition or direct automatic retrieval of information from a well-structured knowledge base.39 Through the use of inductive reasoning, pattern recognition/interpretation is a process characterised by speed and efficiency.40 |

| Forward reasoning; backward reasoning40,41 | Forward reasoning describes inductive reasoning in which data analysis results in hypothesis generation or diagnosis, utilising a sound knowledge base. Forward reasoning is more likely to occur in familiar cases with experienced health professionals, and backward reasoning with inexperienced health professionals or in atypical or difficult cases.41 Backward reasoning is the re-interpretation of data or the acquisition of new clarifying data invoked to test a hypothesis. |

| Knowledge reasoning integration42,43 | Clinical reasoning requires domain-specific knowledge and an organised knowledge base. A stage theory which emphasises the parallel development of knowledge acquisition and clinical reasoning expertise has been proposed.43 Clinical reasoning involves the integration of knowledge, reasoning and meta-cognition.44 |

| Intuitive reasoning45,46 | ‘Intuitive knowledge’ is related to ‘instance scripts’ or past experience with specific cases which can be used unconsciously in inductive reasoning. |

| Multidisciplinary reasoning47 | Occurs when members of a multidisciplinary team work together to make clinical decisions for the patient, for example at case conferences and in multidisciplinary clinics. |

| Conditional reasoning48–50 | Used by health professionals to estimate a patient's response to intervention and the likely outcomes of management and to help patients consider possibilities and reconstruct their lives following injury or the onset of disease. |

| Narrative reasoning48,51,52 | The use of stories regarding past or present patients to further understand and manage a clinical situation. Telling the story of patients' illness or injury to help them make sense of the illness experience. |

| Interactive reasoning48,49 | Interactive reasoning occurs between health professional and patient to understand the patient's perspective. |

| Collaborative reasoning20,48,53,54 | The shared decision making that ideally occurs between health professionals and their patients. The patient's opinions as well as information about the problem are actively sought and utilised. |

| Ethical reasoning48,55–57 | Those less recognised but frequently made decisions regarding moral, political and economic dilemmas which health professionals regularly confront, such as deciding how long to continue an intervention for. |

| Teaching as reasoning48,58 | When health professionals consciously use advice, instruction and guidance for the purpose of promoting change in the patient's understanding, feelings and behaviour. |

1. The inherently complex nature of clinical reasoning as a phenomenon. Clinical reasoning models are essentially an interpretation or an approximation of a very complex set of thinking processes at both cognitive and meta-cognitive levels. These processes use both domain-specific and generic knowledge. They operate in conjunction with other abilities such as communication and interpersonal interaction and are framed by the health professional's individual values, interests and practice model.

2. The multiple, multi-dimensional ways of reasoning that evolve with growing expertise. Health professionals, both within and across various health professions, do not reason in the same way. The assumption that there is one way of representing clinical reasoning expertise or a single correct way to solve a problem has been challenged.30 The different ways that health professionals think as they gain expertise was explained earlier in this chapter.

3. The embedding of clinical reasoning in decision–action cycles. As discussed, professional practice inherently deals with actions. Decisions and actions in professional practice influence each other. Decision making is a dynamic, reciprocal process of making decisions and implementing an optimal course of action.31 These decision–action cycles form the basis for professional judgment.

4. The influence of contextual factors. It is important to remember that, in practice, health professionals are required to make decisions about particular actions that are going to be taken with particular patients in particular practice settings. The influence of context on clinical decision making has been examined, and it was identified that the nature of the task (such as its difficulty, complexity and uncertainty), the characteristics of the decision maker (including frames of reference, individual capabilities and experience) and the external decision-making context (such as professional ethics, disciplinary norms and workplace policies) all influence the decision-making process.32

5. The nature of collaborative decision making. As presented in Chapter 14, there is a growing trend, and indeed societal pressure, for patients and health professionals to adopt a collaborative approach to clinical reasoning which increases the patient's role and power in decision making.33 Shared decision making and being able to work together are important for creating and providing services that result in satisfactory outcomes for patients.

An interpretative model of clinical reasoning

The above factors attest to the complexity and fluid nature of professional practice, which requires more than just cognitive processes. A model that views clinical reasoning as a contextualised interactive phenomenon has been developed by Higgs and Jones.29

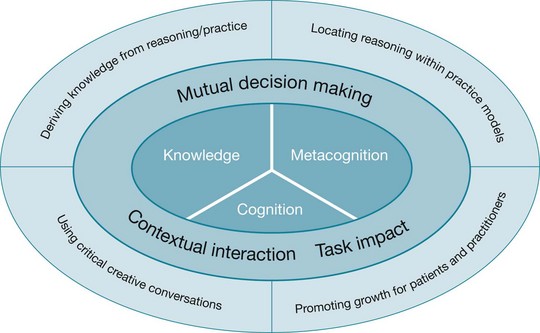

Figure 15.1 portrays the characteristics of this model, which include:

Figure 15.1 An interpretative model of clinical reasoning. Based on Higgs J, Jones M. Clinical decision making and multiple problem spaces, 2008.29

a. Discipline-specific knowledge—propositional knowledge (derived from theory and research) and non-propositional knowledge (derived from professional and personal experience)

b. Cognition—the thinking skills used to process clinical data against the health professional's existing discipline-specific and personal knowledge base in consideration of the patient's needs and the clinical problem

c. Meta-cognition—reflective self-awareness enables health professionals to identify limitations in the quality of information obtained, monitor errors and credibility in their reasoning and practice and recognise inadequacies in their knowledge and reasoning.

2. Interactive/contextual dimensions

a. Mutual decision making—the role of the patient in the decision-making process

b. Contextual interaction—the interactivity between the decision makers and the decision-making situation

c. Task impact—the influence of the nature of the clinical problem or task on the reasoning process.

a. The ability to derive knowledge from reasoning and practice

b. The capacity to locate reasoning within the health professional's chosen practice models

c. The reflexive ability to promote patients' and health professionals' wellbeing and development

d. The use of critical, creative conversations28 to make clinical decisions.

As this model demonstrates, health professionals use a range of cognitive, meta-cognitive and interactive skills to obtain and combine knowledge and data from a range of sources when making clinical judgments. They need access to propositional knowledge that is appropriate to their professional discipline as well as knowledge about health and wellbeing more generally. This type of knowledge has been emphasised in conceptualisations of evidence-based practice to date. They also need access to non-propositional knowledge that is derived from professional and personal experience. They need the cognitive abilities to combine this information and the meta-cognitive skills to evaluate the trustworthiness and relevance of knowledge from these different sources and apply it to the practice decisions they have to make and to make changes to their practice accordingly. The capacity of health professionals to implement practice that aims to improve patient outcomes through the use of ‘evidence’ to substantiate that practice must be developed over time as experience grows and through critical appraisal of one's practice.

How do I make my practice evidence-based?

In this chapter, we have presented professional practice as a complex and fluid process that is characterised by high levels of uncertainty that arise from the context-dependent nature of the tasks that are undertaken. Professional practice is difficult to describe specifically, as it involves fulfilling particular professional roles with particular patients within particular contexts. Each of these factors contributes a unique aspect to the phenomenon, leading to a complex range of variations to what might be considered ‘standard practice’. Therefore, there is no easy answer to the question, ‘How do I make my practice evidence-based?’ However, a number of principles and tools can provide health professionals with strategies for working towards improved patient outcomes through a practice that is evidence-based. The following list provides some ideas that you may wish to use as your practice and professional development requires. The principle of critically reflecting on your practice underpins these ideas. Critical reflection refers to the process of analysing, reconsidering and questioning your experiences within a broad context of issues.

• Be systematic in the way you collect and use information and knowledge so that you can be sure that the information and knowledge you are using is trustworthy and relevant to the decisions you have to make.

• Use sound and logical reasoning as well as compassion and understanding when making decisions, and be clear about the information and knowledge you are basing those decisions on.

• Have a good working knowledge of the current propositional knowledge that is relevant to your professional community of practice or profession and the type of practice in which you are engaged (for example, if you are working as a rehabilitation therapist where you primarily treat people who have neurological disorders, you need to know the propositional knowledge appropriate to your work). Be aware of the limits of your propositional knowledge and plan how you will systematically expand this knowledge to better inform your practice. Plan how you will determine the relevance of this knowledge to your practice more generally and to individual patients more specifically. Remember that evidence from a range of research approaches forms a key component of the propositional knowledge relevant to your practice.

• Be aware of your current non-propositional knowledge. Remember that non-propositional knowledge includes your professional craft knowledge (for example, knowing how to do things) and your personal knowledge (for example, understanding of your strengths, weaknesses, preferences and interests). Ask yourself questions like: How have I systematically tested my practice experiences and derived knowledge from these experiences? Can I communicate this knowledge with credibility to my colleagues and patients and use it as sound evidence to support my practice? Is there personal knowledge derived from my life experiences (for example, working with people from different cultures) that I can use in my practice? What have I learned about communicating with people who speak different languages to me or who experience hardship, disability or illness/injury that I can use to enhance my practice? Planning to systematically enhance or expand this type of knowledge is an excellent way of drawing on your practice expertise and individualising the services that you provide to patients.

• Engage in empathic visioning and collaborative questioning with patients about their experiences, knowledge and values. Listen to your patients' stories and experiences and try to understand their experience of and perspective on the situation. Ask them what they think would make the biggest difference in their life. Practise problem solving and mutual decision making with your patients to expand your collaboration skills and improve your decision making.

• Be aware of the degree to which your actions are informed by the different sources of information and knowledge: research evidence; your own clinical expertise; the patients' values, preferences and circumstances; and an understanding of the practice context and how it shapes your practice (for example, what demands and expectations it places on you; in what ways is constrains what you can and cannot do).

• Critically reflect on and practise articulating your reasoning and your professional practice model.

Much professional expertise becomes ‘embodied’ knowledge or practice wisdom. You might not be aware of the details of this knowledge or be able to articulate this knowledge. To utilise this knowledge effectively as evidence for practice, it is important to raise awareness of those aspects of professional and personal thinking and action that have become taken for granted. This includes an ability to critically evaluate the types of knowledge that are available to health professionals, including the assumptions about knowledge that are unquestioned. By engaging in critical reflection, you can become more systematic in your collection and use of the knowledge upon which you base your practice. To conduct truly evidence-based practice, you need to be aware of the types of knowledge that you are using and how you are using them, and asking yourself whether this constitutes appropriate evidence for the particular questions and problems about which you seek to be informed. You also need to be aware of the cognitive and meta-cognitive processes that you are using to combine information from different sources within the context of your discipline and practice context.

References

1. Craik, J, Rappolt, S. Theory of research utilisation enhancement: a model for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 2003; 70:266–275.

2. Robertson, L. Clinical reasoning, part 1: the nature of problem solving; a literature review. Br J Occup Ther. 1996; 59:178–182.

3. Sackett, D, Rosenberg, W, Gray, J, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't: it's about integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence. BMJ. 1996; 312:71–72.

4. Higgs, J, Jones, M, Titchen, A. Knowledge, reasoning and evidence for practice. In: Higgs J, Jones M, Loftus S, et al, eds. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2008:151–161.

5. Rycroft-Malone, J, Seers, K, Titchen, A, et al. What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? J Adv Nurs. 2004; 47:81–90.

6. Higgs, J, Andresen, L, Fish, D. Practice knowledge—its nature, sources and contexts. In: Higgs J, Richardson B, Abrandt Dahlgren M, eds. Developing practice knowledge for health professionals. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann; 2004:51–69.

7. Jones, M, Grimmer, K, Edwards, I, et al, Challenges in applying best evidence to physiotherapy. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2006;4(3). Online Available ijahsp.nova.edu/articles/vol4num3/jones.pdf [13 Nov 2012].

8. Small, N. Knowledge, not evidence, should determine primary care practice. Clin Governance. 2003; 8:191–199.

9. Naylor, C. Grey zones of clinical practice: some limits to evidence-based medicine. Lancet. 1995; 345:840–841.

10. Heinemann Australian Student's Dictionary. Melbourne: Reed Educational and Professional Publishing, 1992.

11. The Macquarie Concise Dictionary. 3rd ed, Sydney: Macquarie Library; 1998.

12. Pearson, A. Balancing the evidence: incorporating the synthesis of qualitative data into systematic reviews. JBI Reports. 2004; 2:45–64.

13. Schön, D. The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books; 1983.

14. Fish, D, Coles, C. Developing professional judgement in health care: learning through the critical appreciation of practice. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann; 1998.

15. Coles, C. Developing professional judgement. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002; 22:3–10.

16. Lave, J, Wenger, E. Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991.

17. Walker, R. Social and cultural perspectives on professional knowledge and expertise. In: Higgs J, Titchen A, eds. Practice knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann; 2001:22–28.

18. Dreyfus, H, Dreyfus, S. Mind over machine. New York: Free Press; 1986.

19. McCormack, B, Titchen, A. Patient-centred practice: an emerging focus for nursing expertise. In: Higgs J, Titchen A, eds. Practice knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann; 2001:96–101.

20. Fleming, M. The search for tacit knowledge. In: Mattingly C, Fleming M, eds. Clinical reasoning: forms of inquiry in a therapeutic practice. Philadelphia: F A Davis; 1994:22–34.

21. Jensen, G, Gwyer, J, Hack, L, et al. Expertise in physical therapy practice. Boston: Butterworth–Heinemann; 1999.

22. Sackett, D, Straus, S, Richardson, W, et al. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

23. Higgs, J, Titchen, A, Neville, V. Professional practice and knowledge. In: Higgs J, Titchen A, eds. Practice knowledge and expertise in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann; 2001:3–9.

24. Fish, D, Higgs, J. The context for clinical decision making in the 21st century. In: Higgs J, Jones M, Loftus S, eds. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2008:19–30.

25. Hunink, M, Glasziou, P, Siegel, J, et al. Decision making in health and medicine: integrating evidence and values. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

26. Turpin, M. The issue is … recovery of our phenomenological knowledge in occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2007; 61:481–485.

27. Higgs, J, Titchen, A. Propositional, professional and personal knowledge in clinical reasoning. In: Higgs J, Jones M, eds. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann; 1995:129–146.

28. Higgs, J. The complexity of clinical reasoning: exploring the dimensions of clinical reasoning expertise as a situated, lived phenomenon. CPEA, Occasional Paper 6. Collaborations in Practice and Education Advancement. Australia: The University of Sydney; 2007.

29. Higgs, J, Jones, M. Clinical decision making and multiple problem spaces. In: Higgs J, Jones M, Loftus S, eds. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2008:3–17.

30. Norman, G. Research in clinical reasoning: past history and current trends. Med Educ. 2005; 39:418–427.

31. Smith, M, Higgs, J, Ellis, E. Factors influencing clinical decision making. In: Higgs J, Jones M, Loftus S, eds. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. 3rd ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2008:89–100.

32. Smith, M. Clinical decision making in acute care cardiopulmonary physiotherapy. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Sydney: The University of Sydney; 2006.

33. Trede, F, Higgs, J. Re-framing the clinician's role in collaborative clinical decision making: re-thinking practice knowledge and the notion of clinician–patient relationships. Learning Health Social Care. 2003; 2:66–73.

34. Barrows, H, Feightner, J, Neufield, V, et al, An analysis of the clinical methods of medical students and physicians Report to the Province of Ontario Department of Health McMaster University Hamilton, Ont., 1978.

35. Elstein, A, Shulman, S, Sprafka, S. Medical problem solving: an analysis of clinical reasoning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978.

36. Feltovich, P, Johnson, P, Moller, J, et al. LCS: The role and development of medical knowledge in diagnostic expertise. In: Clancey W, Shortliffe E, eds. Readings in medical artificial intelligence: the first decade. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1984:275–319.

37. Elstein, A, Shulman, L, Sprafka, S. Medical problem solving: a ten year retrospective. Eval Health Prof. 1990; 13:5–36.

38. Barrows, H, Feltovich, P. The clinical reasoning process. Med Educ. 1987; 21:86–91.

39. Groen, G, Patel, V. Medical problem-solving: some questionable assumptions. Med Educ. 1985; 19:95–100.

40. Arocha, J, Patel, V, Patel, Y. Hypothesis generation and the coordination of theory and evidence in novice diagnostic reasoning. Med Decis Making. 1993; 13:198–211.

41. Patel, V, Groen, G. Knowledge-based solution strategies in medical reasoning. Cogn Sci. 1986; 10:91–116.

42. Schmidt, H, Norman, G, Boshuizen, H. A cognitive perspective on medical expertise: theory and implications. Acad Med. 1990; 65:611–621.

43. Boshuizen, H, Schmidt, H. On the role of biomedical knowledge in clinical reasoning by experts, intermediates and novices. Cogn Sci. 1992; 16:153–184.

44. Higgs, J, Jones, M. Clinical reasoning. In: Higgs J, Jones M, eds. Clinical reasoning in the health professions. Oxford: Butterworth–Heinemann; 1995:3–23.

45. Agan, R. Intuitive knowing as a dimension of nursing. Adv Nurs Sci. 1987; 10:63–70.

46. Rew, L. Intuition in critical care nursing practice. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1990; 9:30–37.

47. Loftus, S, Language in clinical reasoning: learning and using the language of collective clinical decision making PhD Thesis. The University of Sydney, Australia, 2006. Online Available http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/1165 [13 Nov 2012].

48. Edwards, I, Jones, M, Carr, J, et al, Clinical reasoning in three different fields of physiotherapy—a qualitative study Melbourne. Proceedings of the Fifth International Congress of the Australian Physiotherapy Association, 1998:298–300.

49. Fleming, M. The therapist with the three track mind. Am J Occup Ther. 1991; 45:1007–1014.

50. Hagedorn, R. Clinical decision making in familiar cases: a model of the process and implications for practice. Br J Occup Ther. 1996; 59:217–222.

51. Benner, P, Tanner, C, Chesla, C. From beginner to expert: gaining a differentiated clinical world in critical care nursing. Adv Nurs Sci. 1992; 14:13–28.

52. Mattingly, C, Fleming, MH. Clinical reasoning: forms of inquiry in a therapeutic practice. Philadelphia: F A Davis; 1994.

53. Coulter, A. Shared decision-making: the debate continues. Health Expect. 2005; 8:95–96.

54. Beeston, S, Simons, H. Physiotherapy practice: practitioners’ perspectives. Physiother Theory Pract. 1996; 12:231–242.

55. Barnitt, R, Partridge, C. Ethical reasoning in physical therapy and occupational therapy. Physiother Res Int. 1997; 2:178–194.

56. Gordon, M, Murphy, C, Candee, D, et al. Clinical judgement: an integrated model. Adv Nurs Sci. 1994; 16:55–70.

57. Neuhaus, B. Ethical considerations in clinical reasoning: the impact of technology and cost containment. Am J Occup Ther. 1988; 42:288–294.

58. Sluijs, EM. Patient education in physiotherapy: towards a planned approach. Physiotherapy. 1991; 77:503–508.