CHAPTER 16 Chronic Periodontitis

Chronic periodontitis, formerly known as adult periodontitis or chronic adult periodontitis, is the most prevalent form of periodontitis. It is generally considered to be a slowly progressing disease. However, in the presence of systemic or environmental factors that may modify the host response to plaque accumulation, such as diabetes, smoking, or stress, disease progression may become more aggressive. Although chronic periodontitis is most frequently observed in adults, it can occur in children and adolescents in response to chronic plaque and calculus accumulation. This observation underlies the recent name change from “adult” periodontitis, which suggests that chronic, plaque-induced periodontitis is only observed in adults, to a more universal description of “chronic” periodontitis, which can occur at any age (see Chapter 4).

Chronic periodontitis has been defined as “an infectious disease resulting in inflammation within the supporting tissues of the teeth, progressive attachment loss, and bone loss.”3 This definition outlines the major clinical and etiologic characteristics of the disease: (1) microbial plaque formation, (2) periodontal inflammation, and (3) loss of attachment and alveolar bone. Periodontal pocket formation is usually a sequela of the disease process unless gingival recession accompanies attachment loss, in which case pocket depths may remain shallow, even in the presence of ongoing attachment loss and bone loss.

Clinical Features

General Characteristics

Characteristic clinical findings in patients with untreated chronic periodontitis may include supragingival and subgingival plaque accumulation (frequently associated with calculus formation), gingival inflammation, pocket formation, loss of periodontal attachment, loss of alveolar bone, and occasional suppuration (Figure 16-1). In patients with poor oral hygiene, the gingiva typically may be slightly to moderately swollen and exhibit alterations in color ranging from pale red to magenta. Loss of gingival stippling and changes in the surface topography may include blunted or rolled gingival margins and flattened or cratered papillae.

Figure 16-1 Clinical features of chronic periodontitis in 45-year-old patient with poor oral home care and no previous dental treatment. Abundant plaque and calculus are associated with redness, swelling, and edema of the gingival margin. Gingival recession is evident, resulting from loss of attachment and alveolar bone. Spontaneous bleeding is present, and there is visible exudate of gingival crevicular fluid. Gingival stippling has been lost.

In many patients, especially those who perform regular home care measures, the changes in color, contour, and consistency frequently associated with gingival inflammation may not be visible on inspection, and inflammation may be detected only as bleeding of the gingiva in response to examination of the periodontal pocket with a periodontal probe (see Figures 16-2, A, and 16-3, A). Gingival bleeding, either spontaneous or in response to probing, is common, and inflammation-related exudates of crevicular fluid and suppuration from the pocket also may be found. In some cases, probably as a result of long-standing, low-grade inflammation, thickened, fibrotic marginal tissues may obscure the underlying inflammatory changes. Pocket depths are variable, and both horizontal and vertical bone loss can be found. Tooth mobility often appears in advanced cases with extensive attachment loss and bone loss.

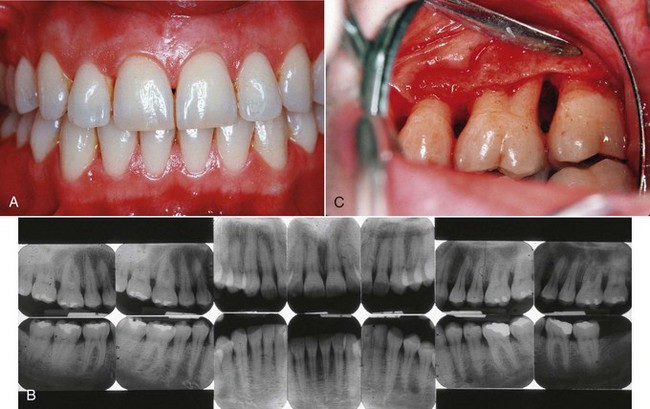

Figure 16-2 Localized chronic periodontitis in 42-year-old female. A, Clinical view of anterior teeth showing minimal plaque and inflammation. B, Radiographs showing presence of localized, vertical, angular bone loss on the distal side of the maxillary left first molar. C, Surgical exposure of the vertical (angular) defect associated with the chronic plaque accumulation and inflammation in the distobuccal furcation.

Figure 16-3 Generalized chronic periodontitis in 38-year-old female with 20-year history of smoking at least one pack of cigarettes per day. A, Clinical view showing minimal plaque and inflammation. Probing produced negligible bleeding, which is common with smokers. Patient complained of spacing between the right maxillary incisors, which was associated with advanced attachment and bone loss. B, Radiographs showing severe, generalized, horizontal pattern of bone loss. Maxillary and mandibular molars have already been lost through advanced disease and furcation involvement.

Chronic periodontitis can be clinically diagnosed by the detection of chronic inflammatory changes in the marginal gingiva, presence of periodontal pockets, and loss of clinical attachment. It is diagnosed radiographically by evidence of bone loss. These findings may be similar to those seen in aggressive disease. A differential diagnosis is based on the age of the patient, rate of disease progression over time, familial nature of aggressive disease, and relative absence of local factors in aggressive disease compared with the presence of abundant plaque and calculus in chronic periodontitis.

Disease Distribution

Chronic periodontitis is considered a site-specific disease. The clinical signs of chronic periodontitis—inflammation, pocket formation, attachment loss, and bone loss—are believed to be caused by the direct, site-specific effects of subgingival plaque accumulation. As a result of this local effect, pocket formation and attachment and bone loss may occur on one surface of a tooth while other surfaces maintain normal attachment levels. For example, a proximal surface with chronic plaque accumulation may have loss of attachment, whereas the plaque-free facial surface of the same tooth may be free of disease.

In addition to being site specific, chronic periodontitis may be described as being localized, when few sites demonstrate attachment and bone loss, or generalized, when many sites around the mouth are affected, as follows:

The pattern of bone loss observed in chronic periodontitis may be vertical (angular), when attachment and bone loss on one tooth surface is greater than that on an adjacent surface (see Figure 16-2, C), or horizontal, when attachment and bone loss proceeds at a uniform rate on the majority of tooth surfaces (see Figure 16-3, B). Vertical bone loss is associated with intrabony pocket formation. Horizontal bone loss is usually associated with suprabony pockets.

Disease Severity

The severity of destruction of the periodontium that occurs as a result of chronic periodontitis is generally considered a function of time. With increasing age, attachment loss and bone loss become more prevalent and more severe because of an accumulation of destruction. Disease severity may be described as slight (mild), moderate, or severe (see Chapter 4). These terms may be used to describe the disease severity of the entire mouth or part of the mouth (e.g., quadrant, sextant) or the disease status of an individual tooth, as follows.

Symptoms

Patients may first become aware that they have chronic periodontitis when they notice that their gums bleed when brushing or eating; that spaces occur between their teeth as a result of tooth movement; or that teeth have become loose. Because chronic periodontitis is usually painless, however, patients may be totally unaware that they have the disease and may be less likely to seek treatment and accept treatment recommendations. In addition, a negative response to questions such as, “Are you in pain?” is not sufficient to eliminate suspicion of periodontitis. Occasionally, pain may be present in the absence of caries caused by exposed roots that are sensitive to heat, cold, or both. Areas of localized dull pain, sometimes radiating deep into the jaw, have been associated with periodontitis. The presence of areas of food impaction may add to the patient’s discomfort. Gingival tenderness or “itchiness” may also be found.

Disease Progression

Patients appear to have the same susceptibility to plaque-induced chronic periodontitis throughout their lives. The rate of disease progression is usually slow but may be modified by systemic or environmental and behavioral factors. Onset of chronic periodontitis can occur at any time, and the first signs may be detected during adolescence in the presence of chronic plaque and calculus accumulation. Because of its slow rate of progression, however, chronic periodontitis usually becomes clinically significant in the mid-thirties or later.

Chronic periodontitis does not progress at an equal rate in all affected sites throughout the mouth. Some involved areas may remain static for long periods,6 whereas others may progress more rapidly. More rapidly progressive lesions occur most frequently in interproximal areas5,7 and may also be associated with areas of greater plaque accumulation and inaccessibility to plaque control measures (e.g., furcation areas, overhanging margins of restorations, sites of malposed teeth, or areas of food impaction).

Several models have been proposed to describe the rate of disease progression.10 In these models, progression is measured by determining the amount of attachment loss during a given period, as follows:

Prevalence

Chronic periodontitis increases in prevalence and severity with age, generally affecting both genders equally. Periodontitis is an age-associated, not an age-related, disease. In other words, it is not the age of the individual that causes the increase in disease prevalence, but rather the length of time that the periodontal tissues are challenged by chronic plaque accumulation.

Risk Factors for Disease

Prior History of Periodontal Disease

Although not a true risk factor for disease but rather a disease predictor, a prior history of periodontal disease puts patients at greater risk for developing loss of attachment and bone, given a challenge from bacterial plaque accumulation.8,9

This means that a patient who presents with persistent gingivitis or periodontitis with pocketing, attachment loss, and bone loss may continue to lose periodontal support if not successfully treated. In addition, a patient with chronic periodontitis who has been successfully treated will develop continuing disease if plaque is allowed to accumulate. This emphasizes the need for continuous monitoring, treatment, and maintenance of patients with persistent gingivitis or periodontitis to prevent recurrence of disease. The risk factors that contribute to patient susceptibility are discussed in the following sections.

Local Factors

Plaque accumulation on tooth and gingival surfaces at the dentogingival junction is considered the primary initiating agent in the etiology of gingivitis and chronic periodontitis.5 Attachment and bone loss are associated with an increase in the proportion of gram-negative organisms in the subgingival plaque biofilm, with specific increases in organisms known to be exceptionally pathogenic and virulent. Porphyromonas gingivalis (formerly Bacteroides gingivalis), Tannerella forsythia (formerly Bacteroides forsythus), and Treponema denticola, otherwise known as the “red complex,” are frequently associated with ongoing attachment and bone loss in chronic periodontitis (see Chapter 23).

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Patients with chronic periodontitis most often show slow progressive attachment and bone loss that extends over decades. This bone loss is initiated by specific groups of periodontal pathogenic gram negative anaerobic bacteria and therefore control of the subgingival plaque biofilm is an essential part of therapy. Some patients are susceptible to more rapid bone and attachment loss including those with a history of smoking, diabetes, or a genetic profile that increases the production of interleukin-1, a potent inflammatory cytokine that plays a pivotal role in bone and tissue destruction.

Attachment loss of 2 mm or more per year is an indicator of accentuated disease progression and these patients should be treated quickly to change the bacterial milieu by pocket depth reduction, and improved daily oral hygiene followed by maintenance recall visits ever 3 or 4 months.

Chronic periodontitis is generally slowly progressive, with some patients having increased susceptibility to attachment and bone loss and pocketing. Some patients who have a genetic profile that accentuates interleukin-1 (IL-1) production may have an increased risk of tooth loss, and if these patients are also smokers, their risk increases. Diabetes is another factor that often leads to severe and extensive periodontal destruction. Also, a specific group of microorganisms is seen in the subgingival biofilm of patients with ongoing bone loss associated with chronic periodontitis, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, and Treponema denticola.

The identification and characterization of these and other pathogenic microorganisms and their association with attachment and bone loss have led to the specific plaque hypothesis for the development of chronic periodontitis. This hypothesis implies that although a general increase occurs in the proportion of gram-negative microorganisms in the subgingival plaque in periodontitis, it is the presence of increased proportions of members of the red complex, and perhaps other microorganisms, that precipitates attachment and bone loss. The mechanisms by which this occurs have not been clearly delineated, but these bacteria may impart a local effect on the cells of the inflammatory response and the cells and tissues of the host, resulting in a local, site-specific disease process. The interactions between pathogenic bacteria and the host and their potential effects on disease progression are discussed in detail in Part 4.

Because plaque accumulation is the primary initiating agent in periodontal inflammation and destruction, anything that facilitates plaque accumulation or prevents plaque removal by oral hygiene procedures can be detrimental to the patient. Plaque-retentive factors are important in the development and progression of chronic periodontitis because they retain plaque microorganisms in proximity to the periodontal tissues, providing an ecologic niche for plaque growth and maturation. Calculus is considered the most important plaque-retentive factor because of its ability to retain and harbor plaque bacteria on its rough surface. As a result, calculus removal is essential for the maintenance of a healthy periodontium. Other factors that are known to retain plaque or prevent its removal are subgingival and overhanging margins of restorations; carious lesions that extend subgingivally; furcations exposed by loss of bone; crowded and malaligned teeth; and root grooves and concavities. These potential risk factors for periodontitis are discussed further in Chapter 32, and their impact on the prognosis of periodontal treatment is discussed in Chapter 33.

Systemic Factors

The rate of progression of plaque-induced chronic periodontitis is generally considered to be slow. However, when chronic periodontitis occurs in a patient who also has a systemic disease that influences the effectiveness of the host response, the rate of periodontal destruction may be significantly increased.

Diabetes is a systemic condition that can increase the severity and extent of periodontal disease in an affected patient. Type 2 diabetes, or non–insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), is the most prevalent form of diabetes and accounts for 90% of diabetic patients.1

In addition, type 2 diabetes is most likely to develop in an adult population at the same time as chronic periodontitis. The synergistic effect of plaque accumulation and modulation of an effective host response through the effects of diabetes can lead to severe and extensive periodontal destruction that may be difficult to manage with standard clinical techniques without controlling the systemic condition. An increase in type 2 diabetes in teenagers and young adults has been observed and may be associated with an increase in juvenile obesity.

In addition, type 1 diabetes, or insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM), is observed in children, teenagers, and young adults and may lead to increased periodontal destruction when it is uncontrolled. It is likely that chronic periodontitis, aggravated by the complications of type 1 and type 2 diabetes, will increase in prevalence in the near future and will provide therapeutic challenges to the clinician.

Environmental and Behavioral Factors

Smoking has been shown to increase the severity and extent of periodontal disease. When combined with plaque-induced chronic periodontitis, an increase in the rate of periodontal destruction may be observed in patients who smoke and have chronic periodontitis. As a result, smokers with chronic periodontitis have more attachment and bone loss, more furcation involvements, and deeper pockets (see Figure 16-3). In addition, they appear to form more supragingival and less subgingival calculus and demonstrate less bleeding on probing than nonsmokers. Initial evidence to explain these effects suggests changes in the subgingival microflora of smokers compared with nonsmokers, in addition to the effects of smoking on the host response. The clinical, microbiologic, and immunologic effects of smoking also appear to influence the response to therapy and the frequency of recurrent disease (see Chapter 26).

Emotional stress has previously been associated with necrotizing ulcerative disease, perhaps because of the effects of stress on immune function. Increasing evidence suggests that emotional stress also may influence the extent and severity of chronic periodontitis, probably through the same mechanisms.

Genetic Factors

Periodontitis is considered to be a multifactorial disease in which the normal balance between microbial plaque and host response is disrupted. This disruption, as described previously, can occur through changes in the plaque composition, changes in the host response, or environmental and behavioral influences on both plaque response and host response. In addition, periodontal destruction is frequently seen among family members and across different generations within a family, suggesting a genetic basis for the susceptibility to periodontal disease. Recent studies have demonstrated a familial aggregation of localized and generalized aggressive periodontitis. In addition, studies of monozygotic twins suggest a genetic component to chronic periodontitis, but the influences of bacterial transmission among family members and environmental effects make it difficult to interpret a complex interaction (see Chapters 24 and 27).

Although no clear genetic determinants have been described for patients with chronic periodontitis, a genetic predisposition to more aggressive periodontal breakdown in response to plaque and calculus accumulation may exist. Studies indicate that a genetic variation or polymorphism in the genes encoding IL-1α and IL-1β is associated with an increased susceptibility to a more aggressive form of chronic periodontitis in subjects of Northern European origin,4 although more recent studies have disputed this association.2 In addition, smokers demonstrating the composite IL-1 genotype are at even greater risk for severe disease. One study suggested that patients with the IL-1 genotype increased the risk for tooth loss by 2.7 times; those who were heavy smokers and IL-1 genotype negative increased the risk for tooth loss by 2.9 times. The combined effect of the IL-1 genotype and smoking increased the risk of tooth loss by 7.7 times.2 With increased characterization of genetic polymorphisms that may exist in other target genes, a complex genotype may be identified for many different clinical forms of periodontitis. However, given the multifactorial nature of periodontal disease, the confounding influence of multiple local, systemic, and environmental conditions and our inability to clearly define the different types of periodontitis, it is unlikely that a clear genetic predisposition to periodontal disease will be found.

1 Diagnosis and classification. In Raskin P, editor: Medical management of non-insulin-dependent (type ii) diabetes, ed 3, Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association, 1994.

2 Fiebig A, Jepsen S, Loos BG, et al. Polymorphisms in the interleukin-1 (IL1) gene cluster are not associated with aggressive periodontitis in a large Caucasian population. Genomics. 2008;92:309-315.

3 Flemmig TF. Periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:32.

4 Kornman KS, di Giovine FS. Genetic variations in cytokine expression: a risk factor for severity of adult periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:327.

5 Lang NP, Schatzle MA, Loe H. Gingivitis as a risk factor in periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:3-8.

6 Lindhe J, Okamoto H, Yoneyama T, et al. Longitudinal changes in periodontal disease in untreated subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:662.

7 Lindhe J, Okamoto H, Yoneyama T, et al. Periodontal loser sites in untreated adult subjects. J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16:671.

8 McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. IV. The effectiveness of clinical parameters and IL-1 genotype in accurately predicting prognoses and tooth survival. J Periodontol. 1999;70:49.

9 Papapanou PN. Risk assessment in the diagnosis and treatment of periodontal diseases. J Dent Educ. 1998;62:822.

10 Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Goodson JM, et al. New concepts of destructive periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:21.