CHAPTER 4 Classfication of Diseases and Conditions Affecting the Periodontium

Our understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of oral diseases and conditions is continually changing with increased scientific knowledge. In light of this, a classification can be most consistently defined by the differences in the clinical manifestations of diseases and conditions because they are clinically consistent and require little, if any, clarification by scientific laboratory testing. The classification presented in this chapter is based on the most recent, internationally accepted, consensus opinion of the diseases and conditions affecting the tissues of the periodontium and was presented and discussed at the 1999 International Workshop for the Classification of the Periodontal Diseases organized by the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP).3 Box 4-1 presents the overall classification system, and each of the diseases or conditions are discussed where clarification is needed. In each case, the reader is referred to pertinent reviews on the subject and specific chapters within this book that discuss the topics in more detail.

BOX 4-1 Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions

Developmental or Acquired Deformities and Conditions

* These diseases may occur on a periodontium with no attachment loss or on a periodontium with attachment loss that is stable and not progressing.

† Chronic periodontitis can be further classified based on extent and severity. As a general guide, extent can be characterized as localized (<30% of sites involved) or generalized (>30% of sites involved). Severity can be characterized based on the amount of clinical attachment loss (CAL) as follows: slight = 1 or 2 mm CAL; moderate = 3 or 4 mm CAL; and severe ≥5 mm CAL. Data from Armitage GC: Ann Periodontol 4:1, 1999.

Gingival Diseases

Dental Plaque–Induced Gingival Diseases

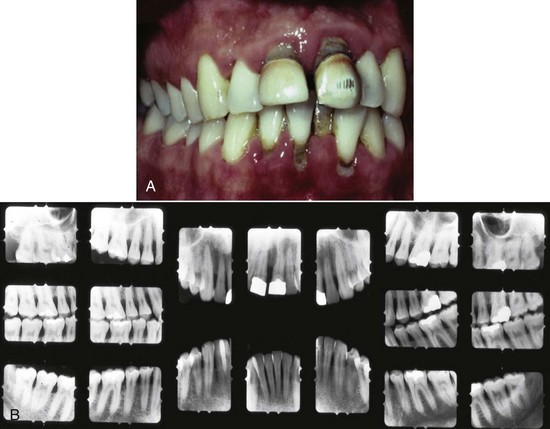

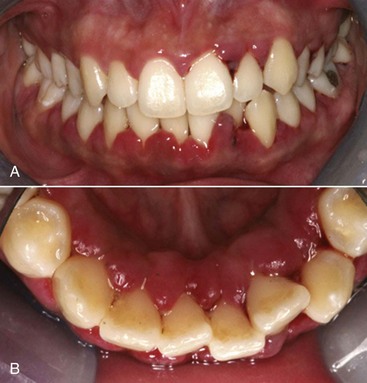

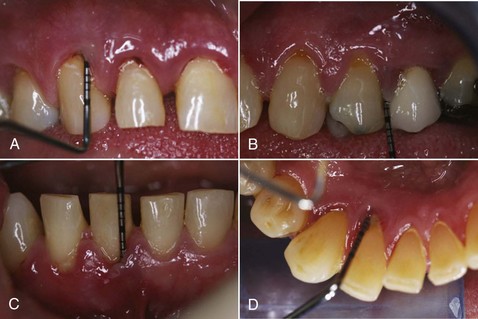

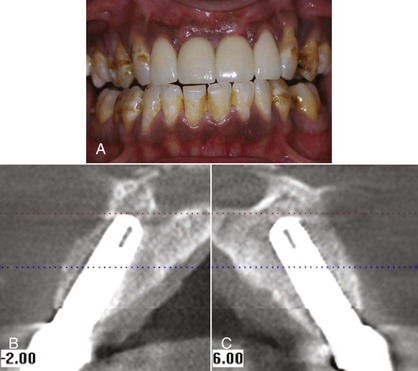

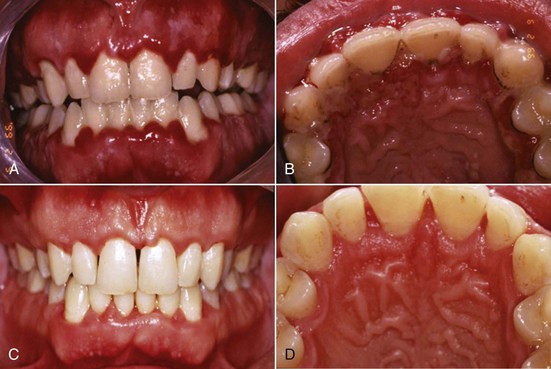

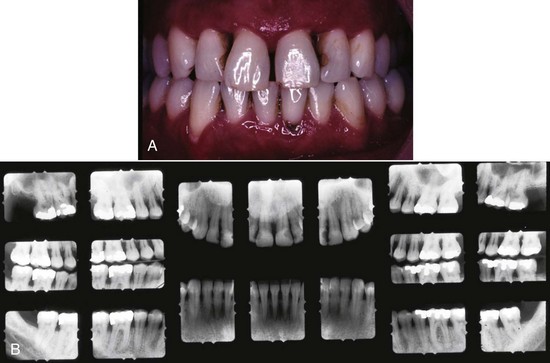

Gingivitis that is associated with dental plaque formation is the most common form of gingival disease (Figure 4-1). Box 4-2 outlines the classifications of gingival diseases. The epidemiology of gingival disease is reviewed in Chapter 5, its etiology is detailed in Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 and elsewhere in this textbook.9,13,14,24,25 Gingivitis has been previously characterized by the presence of clinical signs of inflammation that are confined to the gingiva and associated with teeth showing no attachment loss. Gingivitis also has been observed to affect the gingiva of periodontitis-affected teeth that have previously lost attachment but have received periodontal therapy to stabilize any further attachment loss. In these treated cases, plaque-induced gingival inflammation may recur but without any evidence of further attachment loss.

Figure 4-1 A, Plaque-related gingivitis depicts marginal and papillary inflammation, with 1 to 4 mm probing depths and generalized zero clinical attachment loss, except recession in tooth #28. B, Radiographic images of the patient.

BOX 4-2 Data from Holmstrup P: Ann Periodontol 4:20, 1999; and Mariotti A: Ann Periodontol 4:7, 1999.

Gingival Diseases

Dental Plaque–Induced Gingival Diseases

These diseases may occur on a periodontium with no attachment loss or on a periodontium with attachment loss that is stable and not progressing.

Non–Plaque-Induced Gingival Lesions

From this evidence, it has been concluded that plaque-induced gingivitis may occur on a periodontium with no attachment loss or on a periodontium with previous attachment loss that is stable and not progressing. This implies that gingivitis may be the diagnosis for inflamed gingival tissues associated with a tooth with no previous attachment loss or with a tooth that has previously undergone attachment and bone loss (reduced periodontal support) but is not currently losing attachment or bone, even though gingival inflammation is present (Figure 4-2). For this diagnosis to be made, longitudinal records of periodontal status, including clinical attachment levels, should be available.

Figure 4-2 Maxillary second molar exhibits mild inflammation at mesial-palatal surface. However, the clinical attachment loss has been stable for 15 years after apical positioned flap and periodontal maintenance. Diagnosis is a history of moderate periodontitis, but the case is in remission.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Although plaque-induced gingivitis and periodontitis are the most common diseases of the periodontium, there are many other pathologic processes that are manifested in periodontal tissues. Clinicians need to be cognizant that tissues of the oral cavity can be subjected to a wide range of locally specific diseases and deformities, as well as being an indicator of systemic pathologic entities. Some diseases of the periodontium produce specific diagnostic changes, and others modify the response to the dental bacterial biofilms. These complexities require dentists to develop a broad knowledge and understanding of a wide range of dental and systemic diseases so that their diagnostic skills can give significant benefit to their patients.

The most widely accepted classification of periodontal diseases need to be routinely modified as new diagnostic modalities are developed. In the future there will be an increased utilization of genetic and biotech markets for more accurate and objective diagnoses of periodontal pathology. One group of diseases that are underrepresented in many classifications are the benign and malignant tumors that affect periodontal tissues.

Gingivitis Associated with Dental Plaque Only

Plaque-induced gingival disease is the result of an interaction between the microorganisms found in the dental plaque biofilm and the tissues and inflammatory cells of the host. The plaque-host interaction can be altered by the effects of local factors, systemic factors, medications, and malnutrition, all of which can influence the severity and duration of the response. Local factors that may contribute to gingivitis, in addition to plaque-retentive calculus formation on crown and root surfaces (see Chapter 22). These factors are contributory because of their ability to retain plaque microorganisms and inhibit their removal by patient-initiated plaque control techniques.

Gingival Diseases Modified by Systemic Factors

Systemic factors contributing to gingivitis, such as the endocrine changes associated with puberty (Figure 4-3), the menstrual cycle, pregnancy (Figure 4-4, A), and diabetes, may be exacerbated because of alterations in the gingival inflammatory response to plaque.13,14,24 This altered response appears to result from the effects of systemic conditions on the host’s cellular and immunologic functions. These changes are most apparent during pregnancy, when the prevalence and severity of gingival inflammation may increase, even in the presence of low levels of plaque. Blood dyscrasias, such as leukemia, may alter immune function by disturbing the normal balance of immunologically competent white blood cells supplying the periodontium. Gingival enlargement and bleeding are common findings and may be associated with swollen, spongy gingival tissues caused by excessive infiltration of blood cells (Figure 4-5).

Figure 4-3 Thirteen-year-old female with hormone exaggerated marginal and papillary inflammation, with 1 to 4 mm probing depths yet minimal clinical attachment loss. A, Facial view. B, Lingual view.

Gingival Diseases Modified by Medications

Gingival diseases modified by medications are increasingly prevalent because of the increased use of drugs known to induce gingival enlargement (e.g., anticonvulsant drugs such as phenytoin, immunosuppressive drugs such as cyclosporine (Figure 4-6), and calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine (Figure 4-7), verapamil, diltiazem, and sodium valproate.9,14,24 The development and severity of gingival enlargement in response to medications are patient specific and may be influenced by uncontrolled plaque accumulation, as well as elevated hormonal levels. The increased use of oral contraceptives by premenopausal women has been associated with a higher incidence of gingival inflammation and development of gingival enlargement, which may be reversed by discontinuation of the oral contraceptive.

Gingival Diseases Modified by Malnutrition

Gingival diseases modified by malnutrition have received attention because of clinical descriptions of bright red, swollen, and bleeding gingiva associated with severe ascorbic acid (vitamin C) deficiency or scurvy.14 Nutritional deficiencies are known to affect immune function and may alter the host’s ability to protect itself against some of the detrimental effects of cellular products such as oxygen radicals. Unfortunately, little scientific evidence is available to support a role for specific nutritional deficiencies in the development or severity of gingival inflammation or periodontitis in humans.

Non–Plaque-Induced Gingival Lesions

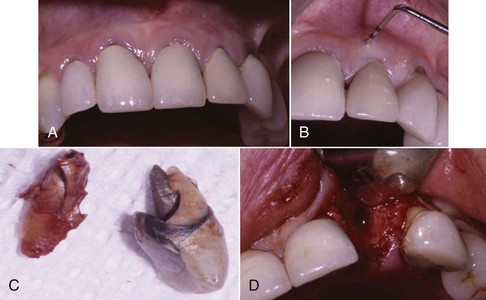

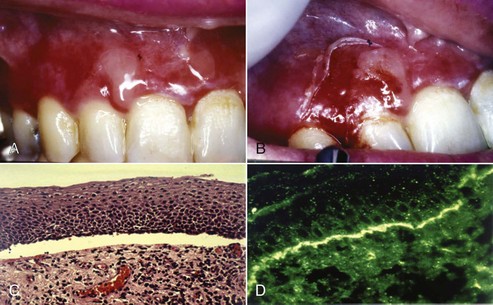

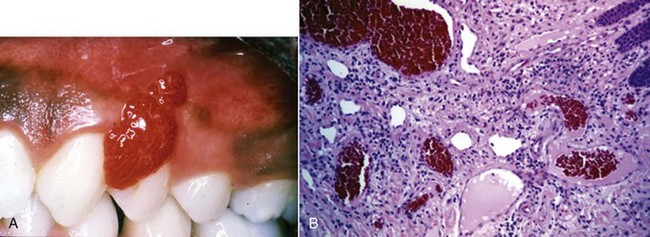

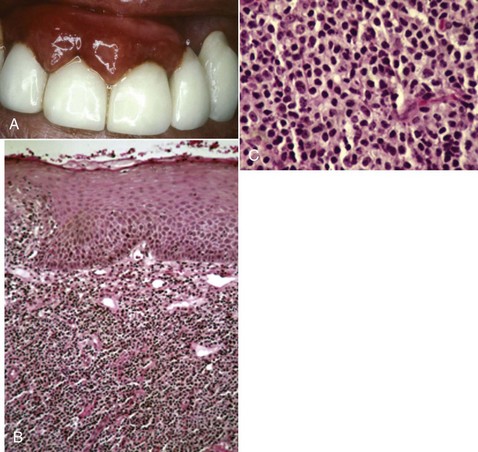

Oral manifestations of systemic conditions that produce lesions in the tissues of the periodontium are rare. These effects are observed more frequently in lower socioeconomic groups, developing countries, and immunocompromised individuals.10 Benign mucous membrane pemphigoid is an example of a non–plaque-induced lesion without socioeconomic implications. Sloughing gingival tissues leave painful ulcerations of the gingiva (Figure 4-8, A and B). Autoimmune antibodies are targeted at the basement membrane and cleave it from the underlying connective tissue. (Figure 4-8, C and D).

Figure 4-8 Sixty-two year-old female with benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. A and B, Clinical image with sloughing epithelial surface. C, Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain depicting separation of epithelium from connective tissue. D, Immunofluorescent-labeled antibodies to basement membrane.

Gingival Diseases of Specific Bacterial Origin

Gingival diseases of specific bacterial origin are increasing in prevalence, especially as a result of sexually transmitted diseases, such as gonorrhea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae), and to a lesser degree, syphilis (Treponema pallidum).26,29 Oral lesions may be secondary to systemic infection or may occur through direct infection. Streptococcal gingivitis or gingivostomatitis is a rare entity that may present as an acute condition with fever, malaise, and pain associated with acutely inflamed, diffuse, red, and swollen gingiva with increased bleeding and occasional gingival abscess formation. The gingival infections usually are preceded by tonsillitis and have been associated with group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infections.

Gingival Diseases of Viral Origin

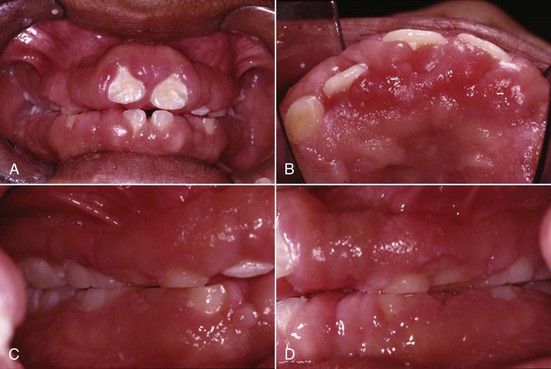

Gingival diseases of viral origin may be caused by a variety of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses, the most common being the herpesviruses (Figure 4-9, A and B). Lesions are frequently related to reactivation of latent viruses, especially as a result of reduced immune function. The oral manifestations of viral infection have been comprehensively reviewed.10,28 Viral gingival diseases are treated with topical and/or systemic antiviral drugs (Figure 4-9, C and D).

Gingival Diseases of Fungal Origin

Gingival diseases of fungal origin are relatively uncommon in immunocompetent individuals but occur more frequently in immunocompromised individuals and those with normal oral flora disturbed by the long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.10,29,30 The most common oral fungal infection is candidiasis, caused by infection with Candida albicans, which also can be seen under prosthetic devices, in individuals using topical steroids, and in individuals with decreased salivary flow, increased salivary glucose, or decreased salivary pH. A generalized candidal infection may manifest as white patches on the gingiva, tongue, or oral mucous membrane that can be removed with gauze, leaving a red, bleeding surface. In individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), candidal infection may present as erythema of the attached gingiva and has been referred to as linear gingival erythema or HIV-associated gingivitis (see Chapter 19).

Diagnosis of candidal infection can be made by culture, smear, and biopsy. Less common fungal infections have also been described.29,30

Gingival Diseases of Genetic Origin

Gingival diseases of genetic origin may involve the tissues of the periodontium and have been described in detail.1 One of the most clinically evident conditions is hereditary gingival fibromatosis, which exhibits autosomal dominant or (rarely) autosomal recessive modes of inheritance. The gingival enlargement may completely cover the teeth, delay eruption, and present as an isolated finding or may be associated with several more generalized syndromes.

Gingival Manifestations of Systemic Conditions

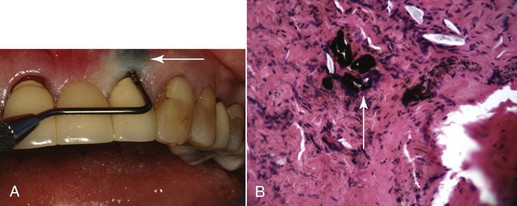

Gingival manifestations of systemic conditions may appear as desquamative lesions, ulceration of the gingiva, or both.10,23,29 Allergic reactions that manifest with gingival changes are uncommon but have been observed in association with several restorative materials (Figure 4-10, A), toothpastes, mouthwashes, chewing gum (Figure 4-11), and foods (see Box 4-2). The diagnosis of these conditions may prove difficult and may require an extensive history and selective elimination of potential causes. Histologic traits of biopsies from gingival allergic reactions include dense infiltrate of eosinophilic cells (Figure 4-10, B and C).

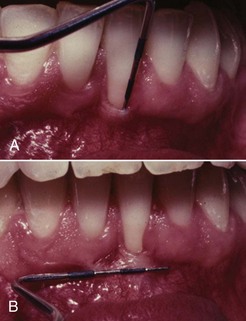

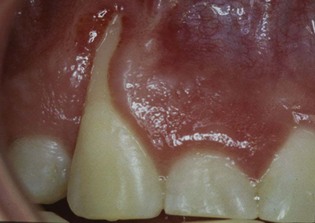

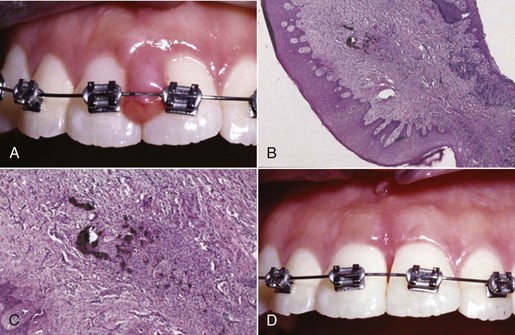

Traumatic Lesions

Traumatic lesions may be self-inflicted and factitious in origin, produced by intentional or unintentional artificial means (Figure 4-12). Other examples of traumatic lesions include toothbrush trauma resulting in gingival ulceration, recession, or both. Iatrogenic trauma (induced by the dentist or health professional) to the gingiva can be caused by induction of orthodontic cement or preventive or restorative materials (Figure 4-13, A). Peripheral ossifying fibroma may develop in response to embedment of a foreign body (Figure 4-13, B and C). Alternatively, accidental damage to the gingiva may occur through minor burns from hot foods and drinks.10

Foreign Body Reactions

Foreign body reactions lead to localized inflammatory conditions of the gingiva and are caused by the introduction of foreign material into the gingival connective tissues through breaks in the epithelium.10 Common examples are the introduction of amalgam into the gingiva during the placement of a restoration, extraction of a tooth, or endodontic apicoectomy with retrofill leaving an amalgam tattoo (Figure 4-14, A) with resultant metal fragments observed in biopsies (Figure 4-14, B), or the introduction of abrasives during polishing procedures.

Periodontitis

Periodontitis is defined as “an inflammatory disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth caused by specific microorganisms or groups of specific microorganisms, resulting in progressive destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone with increased probing depth formation, recession, or both.” The clinical feature that distinguishes periodontitis from gingivitis is the presence of clinically detectable attachment loss. This loss often is accompanied by periodontal pocket formation and changes in the density and height of subjacent alveolar bone. In some cases, recession of the marginal gingiva may accompany attachment loss, thus masking ongoing disease progression if only probing depth measurements are taken without measurements of clinical attachment levels. Clinical signs of inflammation, such as changes in color, contour, and consistency, as well as bleeding on probing, may not always be positive indicators of ongoing attachment loss. However, the presence of continued bleeding on probing at sequential visits has proved to be a reliable indicator of the presence of inflammation and the potential for subsequent attachment loss at the bleeding site. The attachment loss associated with periodontitis has been shown to progress either continuously or in episodic bursts of disease activity.

Although many classifications of the different clinical manifestations of periodontitis have been presented over the past 20 years, consensus workshops in North America in 19896 and Europe in 19934 identified that periodontitis may present in early-onset, adult-onset, and necrotizing forms (Table 4-1). In addition, the AAP consensus concluded that periodontitis may be associated with systemic conditions, such as diabetes and HIV infection, and that some forms of periodontitis may be refractory to conventional therapy. Early-onset disease was distinguished from adult-onset disease by the age of onset (35 years of age was set as an arbitrary separation of diseases), the rate of disease progression, and the presence of alterations in host defenses. The early-onset diseases were more aggressive, occurred in individuals younger than 35 years of age, and were associated with defects in host defenses, whereas adult forms of disease were slowly progressive, became clinically more evident in the fourth decade of life, and were not associated with defects in host defenses. In addition, early-onset periodontitis was subclassified into prepubertal, juvenile, and rapidly progressive forms with localized or generalized disease distributions.

TABLE 4-1 Classification of the Various Forms of Periodontitis

| Classification | Forms of Periodontitis | Disease Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| AAP World Workshop in Clinical Periodontics, 19895 | Adult periodontitis | |

| Early-onset periodontitis (may be prepubertal, juvenile, or rapidly progressive) | ||

| Periodontitis associated with systemic disease | ||

| Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis | Similar to acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis but with associated clinical attachment loss | |

| Refractory periodontitis | Recurrent periodontitis that does not respond to treatment | |

| European Workshop in Periodontology, 19933 | Adult periodontitis | |

| Early-onset periodontitis | ||

| Necrotizing periodontitis | Tissue necrosis with attachment and bone loss | |

| AAP International Workshop for Classification of Periodontal Diseases, 19992 | See Box 4-3 |

AAP, American Academy of Periodontology; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Extensive clinical and basic scientific research of these disease entities has been performed in many countries, and some disease characteristics outlined 10 years ago no longer stand up to rigid scientific scrutiny.7,13,31 In particular, supporting evidence was lacking for the distinct classifications of adult periodontitis, refractory periodontitis, and the various different forms of early-onset periodontitis as outlined by the AAP Workshop for the International Classification of Periodontal Diseases in 19993 (see Table 4-1).

It has been observed that chronic periodontal destruction, caused by the accumulation of local factors, such as plaque and calculus, can occur before age 35 years and that the aggressive disease seen in young patients may be independent of age but has a familial (genetic) association. With respect to refractory periodontitis, little evidence supports that this is indeed a distinct clinical entity because the causes of continued loss of clinical attachment and alveolar bone after periodontal therapy are currently poorly defined and apply to many disease entities. In addition, the clinical and etiologic manifestations of the different diseases outlined in North America in 1989 and in Europe in 1993 were not consistently observed in different countries around the world and did not always fit the models presented. As a result, the AAP held an International Workshop for the Classification of Periodontal Diseases in 1999 to further refine the classification system based on current clinical and scientific data.3 The resulting classification of the different forms of periodontitis was simplified to describe three general clinical manifestations of periodontitis: chronic periodontitis, aggressive periodontitis, and periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic diseases (see Table 4-1 and Box 4-3).

BOX 4-3 Data from Flemmig TF: Ann Periodontol 4:32, 1999; Kinane DF: Ann Periodontol 4:54, 1999; and Tonetti MS, Mombelli A: Ann Periodontol 4:39, 1999.

Periodontitis

The disease periodontitis can be subclassified into the following three major types based on clinical, radiographic, historical, and laboratory characteristics.

Chronic Periodontitis

The following characteristics are common to patients with chronic periodontitis:

Chronic periodontitis may be further subclassified into localized and generalized forms and characterized as slight, moderate, or severe based on the common features described above and the following specific features:

Aggressive Periodontitis

The following characteristics are common to patients with aggressive periodontitis:

The following characteristics are common but not universal:

Aggressive periodontitis may be further classified into localized and generalized forms based on the common features described here and the following specific features:

Localized form

Chronic Periodontitis

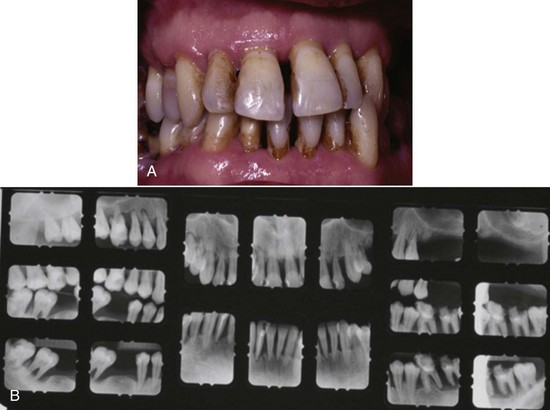

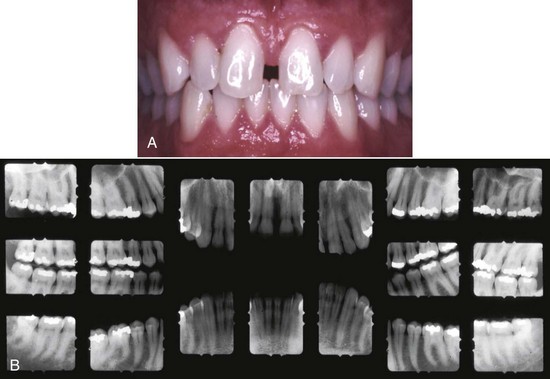

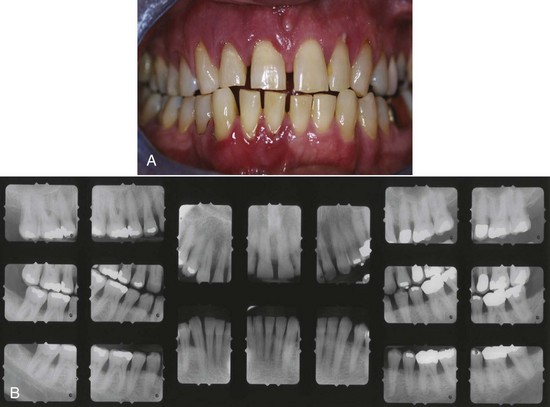

Chronic periodontitis is the most common form of periodontitis7; Box 4-3 includes the characteristics of this form of periodontitis. Chronic periodontitis is most prevalent in adults but can be observed in children; therefore the age range of older than 35 years previously designated for the classification of this disease has been discarded. Chronic periodontitis is associated with the accumulation of plaque and calculus and generally has a slow-to-moderate rate of disease progression, but periods of more rapid destruction may be observed. Increases in the rate of disease progression may be caused by the impact of local, systemic, or environmental factors that may influence the normal host-bacteria interaction. Local factors may influence plaque accumulation (Box 4-4); systemic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus and HIV infection, may influence the host defenses, and environmental factors, such as cigarette smoking and stress, also may influence the response of the host to plaque accumulation. Chronic periodontitis may occur as a localized disease in which less than 30% of evaluated sites demonstrate attachment and bone loss, or it may occur as a more generalized disease in which greater than 30% of sites are affected. The disease also may be described by the severity of disease as slight: 1 to 2 mm (Figure 4-15), moderate: 3 to 4 mm (Figure 4-16), or severe: ≥5 mm (Figure 4-17) based on the amount of clinical attachment loss (see Box 4-3).

BOX 4-4 Data from Blieden TM: Ann Periodontol 4:91, 1999; Halmon WW: Ann Periodontol 4:102, 1999; and Pini Prato GP: Ann Periodontol 4:98, 1999.

Developmental or Acquired Deformities and Conditions

Localized Tooth-Related Factors That Modify or Predispose to Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases or Periodontitis

Figure 4-15 A, Clinical image of plaque-related slight/early chronic periodontitis with 1 to 2 mm clinical attachment loss in 40-year-old female. B, Radiographic images of the patient.

Aggressive Periodontitis

Aggressive periodontitis differs from the chronic form primarily by (1) the rapid rate of disease progression seen in an otherwise healthy individual (Figures 4-18 and 4-19), (2) an absence of large accumulations of plaque and calculus, and (3) a family history of aggressive disease suggestive of a genetic trait20,31 (see Box 4-3). This form of periodontitis was previously classified as early-onset periodontitis (see Table 4-1) and therefore still includes many of the characteristics previously identified with the localized and generalized forms of early-onset periodontitis. Although the clinical presentation of aggressive disease appears to be universal, the etiologic factors involved are not always consistent. Box 4-3 outlines additional clinical, microbiologic, and immunologic characteristics of aggressive disease that may be present. As was previously described for early-onset disease, aggressive forms of periodontitis usually affect young individuals at or shortly after puberty and may be observed during the second and third decades of life (i.e., 10 to 30 years of age). The disease may be localized as previously described for localized juvenile periodontitis (LJP) or generalized as previously described for generalized juvenile periodontitis (GJP) and rapidly progressive periodontitis (RPP) (see Table 4-1). Box 4-3 provides the common features of the localized and generalized forms of aggressive periodontitis.

Periodontitis as a Manifestation of Systemic Diseases

Several hematologic and genetic disorders have been associated with the development of periodontitis in affected individuals12,13 (see Box 4-3). The majority of these observations of effects on the periodontium are the result of case reports, and few research studies have been performed to investigate the exact nature of the effect of the specific condition on the tissues of the periodontium. It is speculated that the major effect of these disorders is through alterations in host defense mechanisms that have been clearly described for disorders, such as neutropenia and leukocyte adhesion deficiencies, but are less well understood for multifaceted syndromes. The clinical manifestation of many of these disorders appears at an early age and may be confused with aggressive forms of periodontitis with rapid attachment loss and the potential for early tooth loss. With the introduction of this form of periodontitis in this and previous classification systems (see Table 4-1), the potential exists for overlap and confusion between periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease and both the aggressive and the chronic form of disease when a systemic component is suspected. At present, periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic disease is the diagnosis to be used when the systemic condition is the major predisposing factor and local factors, such as large quantities of plaque and calculus, are not clearly evident. In the case in which periodontal destruction is clearly the result of local factors but has been exacerbated by the onset of such conditions as diabetes mellitus (Figures 4-20 and 4-21) or HIV infection, the diagnosis should be chronic periodontitis modified by the systemic condition.

Figure 4-20 A, Clinical image of plaque-related severe aggressive periodontitis in 53-year-old male, smoker, with diabetes and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) = 10.7. B, Radiographic images of the patient.

Figure 4-21 Selective probing depths of same 53-year-old diabetic patient shown in Figure 4-20 with severe aggressive periodontitis.

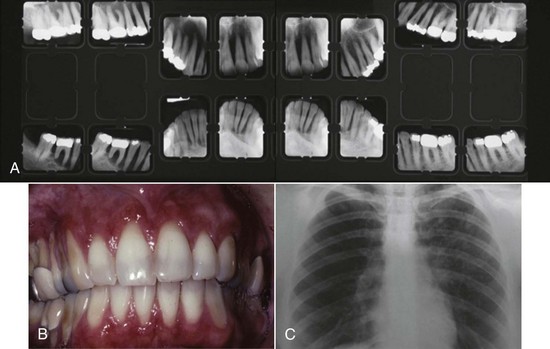

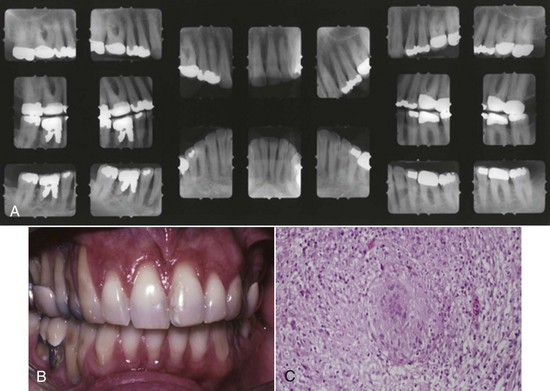

Sarcoidosis is a chronic disease expressed as a cell-mediated delayed-type hypersensitivity that primarily affects the lungs, lymph nodes, skin, eyes, liver, spleen, and small bones of the hands and feet, etc.21 Sarcoidosis rarely affects the oral cavity, with incidence of occurrence in descending order noted in the lymph nodes, lips, soft palate, buccal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, and bone.21 Figure 4-22 depicts the pretreatment pattern of bone loss and recession associated with sarcoidosis, as well as pulmonary parenchymal fibrous infiltrate noted in the lungs as depicted by a white lacy pattern on the chest x-ray (Figure 4-22, C). Histologic features of sarcoidosis include the presence of an intense chronic inflammatory infiltrate with focal areas of noncaseating granulomas and a positive Kveim test2 (Figure 4-23, C). Remineralization of alveolar bone is noted on radiographs obtained 1-year after systemic administration of steroids (Prednisone)18 (Figure 4-23, A).

Necrotizing Periodontal Diseases

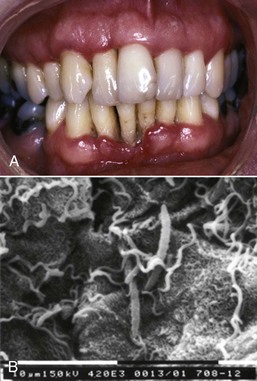

The clinical characteristics of necrotizing periodontal diseases may include but are not limited to ulcerated and necrotic papillary and marginal gingiva covered by a yellowish white or grayish slough or pseudomembrane, blunting and cratering of papillae, bleeding on provocation or spontaneous bleeding, pain, and fetid breath. These diseases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and lymphadenopathy, although these characteristics are not consistent. Two forms of necrotizing periodontal disease have been described: necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) (Figure 4-24) and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) (Figure 4-25). NUG has been previously classified under “gingival diseases” or “gingivitis” because clinical attachment loss is not a consistent feature, whereas NUP has been classified as a form of “periodontitis” because attachment loss is present. Recent reviews of the etiologic and clinical characteristics of NUG and NUP have suggested that the two diseases represent clinical manifestations of the same disease, except that distinct features of NUP are clinical attachment and bone loss. As a result, both NUG and NUP have been determined as a separate group of diseases that have tissue necrosis as a primary clinical feature (see Box 4-1).

Figure 4-24 A, Ulcerative gingivitis illustrating sloughing of marginal gingiva. B, Phase-contrast microscopy reveals spirochetes in subgingival plaque sample.

Figure 4-25 A, Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis with severe clinical attachment loss in 28-year-old male infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). B, Spirochetes noted on surface of sloughed epithelial cells.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

The clinical and etiologic characteristics of NUG27 are described in detail in Chapter 10. The defining characteristics of NUG are its bacterial etiology, its necrotic lesion, and predisposing factors such as psychologic stress, smoking, and immunosuppression. In addition, malnutrition may be a contributing factor in developing countries. NUG is usually seen as an acute lesion that responds well to antimicrobial therapy combined with professional plaque and calculus removal and improved oral hygiene.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis

NUP differs from NUG in that loss of clinical attachment and alveolar bone is a consistent feature.19 All other characteristics appear to be the same between the two forms of necrotizing disease. The characteristics of NUP are described in detail in Chapter 17. NUP may be observed among patients with HIV infection and manifests as local ulceration and necrosis of gingival tissue with exposure and rapid destruction of underlying bone, spontaneous bleeding, and severe pain. HIV-infected patients with NUP are 20.8 times more likely to have CD4+ cell counts below 200 cells/mm3 of peripheral blood than HIV-infected patients without NUP, suggesting that immunosuppression is a major contributing factor. In addition, the predictive value of NUP for HIV-infected patients with CD4+ cell counts below 200 cells/mm3 was 95.1%, and the cumulative probability of death within 24 months of a NUP diagnosis in HIV-infected individuals was 72.9%. In developing countries, NUP also has been associated with severe malnutrition, which may lead to immunosuppression in some patients.

Abscesses of the Periodontium

A periodontal abscess is a localized purulent infection of periodontal tissues and is classified by its tissue of origin.16 The clinical, microbiologic, immunologic, and predisposing characteristics are discussed in Chapters 5 and 23.

Periodontitis Associated with Endodontic Lesions

Classification of lesions affecting the periodontium and pulp is based on the sequence of the disease process.

Endodontic–Periodontal Lesions

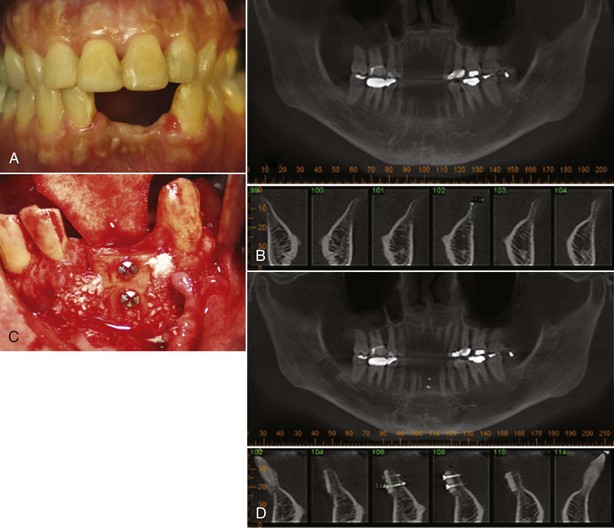

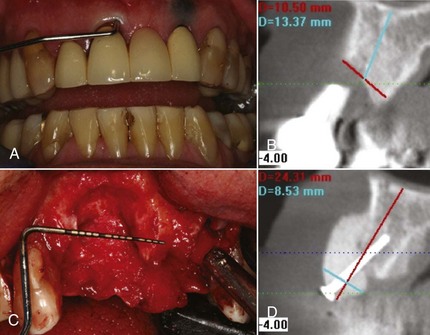

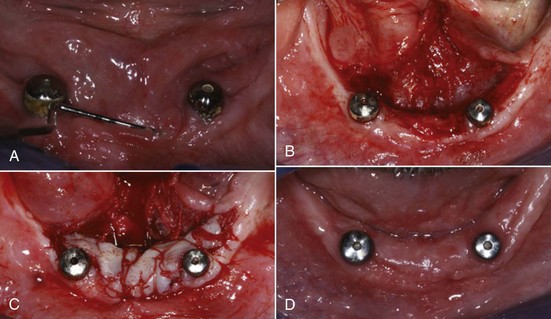

In endodontic–periodontal lesions, pulpal necrosis precedes periodontal changes. A periapical lesion originating in pulpal infection and necrosis may drain to the oral cavity through the periodontal ligament, resulting in destruction of the periodontal ligament and adjacent alveolar bone. This may present clinically as a localized, deep, periodontal probing depth extending to the apex of the tooth (Figure 4-26, A). A resultant extensive alveolar ridge defect (Figure 4-26, B and C) may necessitate reconstructive surgery (Figure 4-26, D) before placement of implants and prosthesis (Figure 4-27) to reestablish a functional and esthetic outcome. Pulpal infection also may drain through accessory canals, especially in the area of the furcation, and may lead to furcal involvement through loss of clinical attachment and alveolar bone.

Figure 4-26 A and C, Clinical image of extensive loss of alveolar ridge secondary to periapical endodontic lesion. B, CT scan depicts alveolar bone loss. D, CT image of regenerated ridge via allogenic bone graft, tenting screw and membrane.

Figure 4-27 Same patient depicted in Figure 4-26. A and B, CT scan of regenerated ridge with implants placed in area 7, 9, and 10. C and D, Clinical image of implant-supported bridge.

Periodontal–Endodontic Lesions

In periodontal–endodontic lesions, bacterial infection from a periodontal pocket associated with loss of attachment and root exposure may spread through accessory canals to the pulp, resulting in pulpal necrosis. In the case of advanced periodontal disease, the infection may reach the pulp through the apical foramen. Scaling and root planing removes cementum and underlying dentin and may lead to chronic pulpitis through bacterial penetration of dentinal tubules. However, many periodontitis-affected teeth that have been scaled and root planed show no evidence of pulpal involvement.

Combined Lesions

Combined lesions occur when pulpal necrosis and a periapical lesion occur on a tooth that is also periodontally involved. An angular intrabony defect that communicates with a periapical lesion of pulpal origin results in a combined periodontal-endodontic lesion.

In all cases of periodontitis associated with endodontic lesions, the endodontic infection should be controlled before beginning definitive management of the periodontal lesion, especially when regenerative or bone-grafting techniques are planned.

Developmental or Acquired Deformities and Conditions

Localized Tooth-Related Factors That Modify or Predispose to Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases or Periodontitis

In general, these localized tooth-related factors contribute to the initiation and progression of periodontal disease through an enhancement of plaque accumulation or the prevention of effective plaque removal by normal oral hygiene measures.5 These factors fall into four subgroups as outlined in Box 4-4.

Tooth Anatomic Factors

Tooth anatomic factors are associated with malformations of tooth development or tooth location. Anatomic factors, such as cervical enamel projections and enamel pearls, have been associated with clinical attachment loss, especially in furcation areas. Cervical enamel projections are found on 15% to 24% of mandibular molars and 9% to 25% of maxillary molars, and strong associations have been observed with furcation involvement.15 Palatogingival grooves, found primarily on maxillary incisors, are observed in 8.5% of individuals and are associated with increased plaque accumulation, clinical attachment, and bone loss. Proximal root grooves on incisors and maxillary premolars also predispose to plaque accumulation, inflammation, and loss of clinical attachment and bone.

Tooth location is considered important in the initiation and development of disease. Malaligned teeth predispose individuals to plaque accumulation with resultant inflammation in children and may predispose to clinical attachment loss in adults, especially when associated with poor oral hygiene habits. In addition, open contacts have been associated with increased loss of alveolar bone, most probably through food impaction.11

Dental Restorations or Appliances

Dental restorations or appliances are frequently associated with the development of gingival inflammation, especially when they are located subgingivally. This may apply to subgingivally placed onlays, crowns, fillings, and orthodontic bands. Restorations may impinge on the biologic width by being placed deep in the sulcus or within the junctional epithelium. This may promote inflammation and loss of clinical attachment and bone, with apical migration of the junctional epithelium and reestablishment of the attachment apparatus at a more apical level.

Root Fractures

Root fractures caused by traumatic forces, restorative or endodontic procedures (Figure 4-28, A to C) may lead to periodontal involvement through an apical migration of plaque along the fracture when the fracture originates coronal to the clinical attachment and is exposed to the oral environment with resultant alveolar ridge defect (Figure 4-28, D).

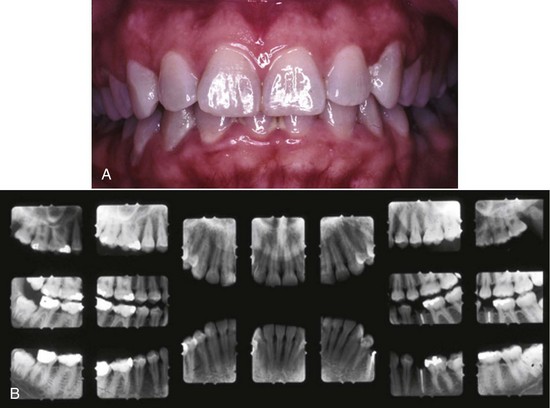

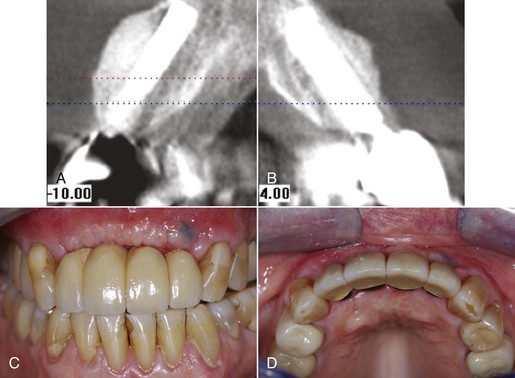

Cervical Root Resorption and Cemental Tears

Cervical root resorption, as noted on the computed tomography (CT) scans in Figure 4-29, A and B, and cemental tears may lead to periodontal destruction when the lesion communicates with the oral cavity and allows bacteria to migrate subgingivally. Avulsed teeth that are re-implants frequently develop ankylosis and cervical resorption many years after re-implantation. Atraumatic removal of such ankylosed teeth and reconstruction of resultant ridge defects with bone grafts, dental implants, and prostheses are viable solutions for such defects (Figure 4-30).

Figure 4-29 A and B, CT scan reveals severe cervical root resorption of maxillary central incisors and periapical abscess. C, Crowns fractured because of resorption. D, Biopsy of soft tissue from resorption.

Figure 4-30 A, Posttreatment clinical image of same patient depicted in Figure 4-29 with implant-supported crowns and veneers on laterals. B and C, CT scan of bone grafts and implants replacing central incisors lost as the result of severe cervical root resorption.

Mucogingival Deformities and Conditions around Teeth

Mucogingival deformity is a generic term used to describe the mucogingival junction and its relationship to the gingiva (Figure 4-31), alveolar mucosa, and frenula muscle attachments. A mucogingival deformity is a significant departure from the normal shape of gingiva and alveolar mucosa and may involve the underlying alveolar bone. Mucogingival surgery corrects defects in the morphology, position, and/or amount of gingiva and is described in detail in Chapter 63. The surgical correction of mucogingival deformities may be performed for esthetic reasons, to enhance function, or to facilitate oral hygiene.22

Mucogingival Deformities and Conditions of Edentulous Ridges

Mucogingival deformities such as lack of stable keratinized gingiva between the vestibular fornices and the floor of the mouth (Figure 4-32, A) may require soft tissue grafting and vestibular deepening before prosthodontic reconstruction (Figure 4-32, B to D). Alveolar bone defects in edentulous ridges (Figure 4-33, A and B) usually require corrective surgery (Figure 4-33, C and D) to restore form and function before placement of implants and prosthesis to replace missing teeth (Figure 4-34).22

Figure 4-32 A, Mucogingival ridge defect from floor of mouth to vestibular fornix. B, Partial thickness flap with vestibular deepening. C, Placement of free gingival graft. D, Reestablishment of vestibular depth and keratinized attached gingiva.

Occlusal Trauma

The etiology of trauma from occlusion and its effects on the periodontium8 is discussed in detail in Chapters 20 and 49.

1 Aldred MJ, Bartold PM. Genetic disorders of the gingivae and periodontium. Periodontol 2000. 1998;18:7.

2 Antunes KB, Miranda AM, Carvalho SR, et al. Sarcoidosis presenting as gingival erosion in a patient under long-term clinical control. J Periodontol. 2008;79:556-561.

3 Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1.

4 Attstrom R, Vander Velden U. Summary of session 1. In: Lang N, Karring T, editors. Proceedings of the 1st European workshop in periodontology. Berlin: Quintessence, 1993.

5 Blieden TM. Tooth-related issues. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:91.

6 Caton J. Periodontal diagnosis and diagnostic aids: consensus report. In: Proceedings of the wold workshop in clinical. American Academy of Periodontology; 1989.

7 Flemmig TF. Periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:32.

8 Hallmon WW. Occlusal trauma: effect and impact on the periodontium. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:102.

9 Hallmon WW, Rossmann JA. The role of drugs in the pathogenesis of gingival overgrowth. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:176.

10 Holmstrup P. Non–plaque-induced gingival lesions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:20.

11 Jernberg GR, Bakdash MB, Keenan KM. Relationship between proximal tooth open contacts and periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1983;54:529-533.

12 Kinane DF. Blood and lymphoreticular disorders. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:84.

13 Kinane DF. Periodontitis modified by systemic factors. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:54.

14 Mariotti A. Dental plaque-induced gingival diseases. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:7.

15 Masters D, Hoskin S: Projection of Cervical Enamel into Molar Furcations, J Periodontol 35:49-53.

16 Meng HX. Periodontal abscess. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:79.

17 Meng HX. Periodontic-endodontic lesions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:84.

18 Moretti AJ, Fiocchi MF, Flaitz CM. Sarcoidosis affecting the periodontium: a long-term follow-up case. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2209-2215.

19 Novak MJ. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:74.

20 Novak MJ, Novak KF. Early-onset periodontitis. Curr Opin Periodonol. 1996;3:45.

21 Pindborg JJ. Atlas of diseases of the oral mucosa. Copenhagen, Denmark: Munksgaard Publication; 1992. pp 156

22 Pini Prato GP. Mucogingival deformities. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:98.

23 Plemons JM, Gonzalez TS, Burkhart NW. Vesiculobullous diseases of the oral cavity. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:158.

24 Porter SR. Gingival and periodontal aspects of diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and malignancy. Periodontol 2000. 1998;18:102.

25 Rees TD. Drugs and oral disorders. Periodontol 2000. 1998;18:21.

26 Rivera Hidalgo F, Stanford TW. Oral mucosal lesions caused by infective microorganisms. I. Viruses and bacteria. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:106.

27 Rowland RW. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:65.

28 Scully C, Laskaris G. Mucocutaneous disorders. Periodontol 2000. 1998;18:81.

29 Scully C, Monteil R, Sposto MR. Infectious and tropical diseases affecting the human mouth. Periodontol 2000. 1998;18:47.

30 Stanford TW, Rivera-Hidalgo F. Oral mucosal lesions caused by infective microorganisms. II. Fungi and parasites. Periodontol 2000. 1999;21:125.

31 Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:39.

5 mm clinical attachment loss in 47-year-old female. B, Radiographic images of the patient.

5 mm clinical attachment loss in 47-year-old female. B, Radiographic images of the patient.