CHAPTER 33 Determination of Prognosis

Definitions

The prognosis is a prediction of the probable course, duration, and outcome of a disease based on a general knowledge of the pathogenesis of the disease and the presence of risk factors for the disease. It is established after the diagnosis is made and before the treatment plan is established. The prognosis is based on specific information about the disease and the manner in which it can be treated, but it also can be influenced by the clinician’s previous experience with treatment outcomes (successes and failures) as they relate to the particular case. It is important to note that determination of prognosis is a dynamic process. As such, the prognosis initially assigned should be reevaluated after completion of all phases of therapy, including periodontal maintenance.

Prognosis is often confused with the term risk. Risk generally deals with the likelihood that an individual will develop a disease in a specified period (see Chapter 5). Risk factors are those characteristics of an individual that put the person at increased risk for developing a disease (see Chapter 32). In contrast, prognosis is the prediction of the course or outcome of a disease. Prognostic factors are characteristics that predict the outcome of disease once the disease is present. In some cases, risk factors and prognostic factors are the same. For example, patients with diabetes or patients who smoke are more at risk for acquiring periodontal disease, and once they have it, they generally have a worse prognosis.

Types of Prognosis

Although some factors may be more important than others when assigning a prognosis34,35 (Box 33-1), consideration of each factor may be beneficial to the clinician.

Historically, prognosis classification schemes have been designed based on studies evaluating tooth mortality.2,3,25,33,34 One scheme25,34 assigns the following classifications:

It should be recognized that good, fair, and hopeless prognoses in this classification system could be established with a reasonable degree of accuracy. However, poor and questionable prognoses were likely to change to other categories because they depend on a large number of factors that can interact in an unpredictable number of ways.8,14,47

In contrast to schemes based on tooth mortality, Kwok and Caton25 have proposed a scheme based on “the probability of obtaining stability of the periodontal supporting apparatus.” This scheme is based on the probability of disease progression as related to local and systemic factors (see Box 33-1). Although some of these factors may affect disease progression more than others, consideration of each factor is important in assigning a prognosis. This scheme is as follows:

Because periodontal stability is assessed on a regular basis using clinical measures, it may be more useful in making treatment decisions and prognosis predictions than trying to determine the likelihood that the tooth will be lost.

In many of these cases, it may be advisable to establish a provisional prognosis until phase I therapy is completed and evaluated. The provisional prognosis allows the clinician to initiate treatment of teeth that have a doubtful outlook in the hope that a favorable response may tip the balance and allow teeth to be retained. The reevaluation phase in the treatment sequence allows the clinician to examine the tissue response to scaling, oral hygiene, and root planing, as well as to the possible use of chemotherapeutic agents where indicated. The patient’s compliance with the proposed treatment plan also can be determined.

Overall Versus Individual Tooth Prognosis

Prognosis can be divided into overall prognosis and individual tooth prognosis. The overall prognosis is concerned with the dentition as a whole. Factors that may influence the overall prognosis include patient age; current severity of disease; systemic factors; smoking; the presence of plaque, calculus, and other local factors; patient compliance; and prosthetic possibilities (see Box 33-1). The overall prognosis answers the following questions:

The individual tooth prognosis is determined after the overall prognosis and is affected by it.33 For example, in a patient with a poor overall prognosis, the dentist likely would not attempt to retain a tooth that has a questionable prognosis because of local conditions. Many of the factors listed under local factors and prosthetic and restorative factors in Box 33-1 have a direct effect on the prognosis for individual teeth, in addition to any overall systemic or environmental factors that may be present.

Factors in Determination of Prognosis

Overall Clinical Factors

Patient Age

For two patients with comparable levels of remaining connective tissue attachment and alveolar bone, the prognosis is generally better for the older of the two. For the younger patient, the prognosis is not as good because of the shorter time frame in which the periodontal destruction has occurred; the younger patient may have an aggressive type of periodontitis, or disease progression may have increased because of systemic disease or smoking. In addition, although the younger patient would ordinarily be expected to have a greater reparative capacity, the occurrence of so much destruction in a relatively short period would exceed any naturally occurring periodontal repair.

Disease Severity

Studies have demonstrated that a patient’s history of previous periodontal disease may be indicative of their susceptibility for future periodontal breakdown (see Chapter 5). Therefore the following variables should be carefully recorded because they are important for determining the patient’s past history of periodontal disease: pocket depth, level of attachment, degree of bone loss, and type of bony defect. These factors are determined by clinical and radiographic evaluation (see Chapters 30 and 31).

The determination of the level of clinical attachment reveals the approximate extent of root surface that is devoid of periodontal ligament; the radiographic examination shows the amount of root surface still invested in bone. Pocket depth is less important than level of attachment because it is not necessarily related to bone loss. In general, a tooth with deep pockets and little attachment and bone loss has a better prognosis than one with shallow pockets and severe attachment and bone loss. However, deep pockets are a source of infection and may contribute to progressive disease.

Prognosis is adversely affected if the base of the pocket (level of attachment) is close to the root apex. The presence of apical disease as a result of endodontic involvement also worsens the prognosis. However, surprisingly good apical and lateral bone repair can sometimes be obtained by combining endodontic and periodontal therapy (see Chapter 51).

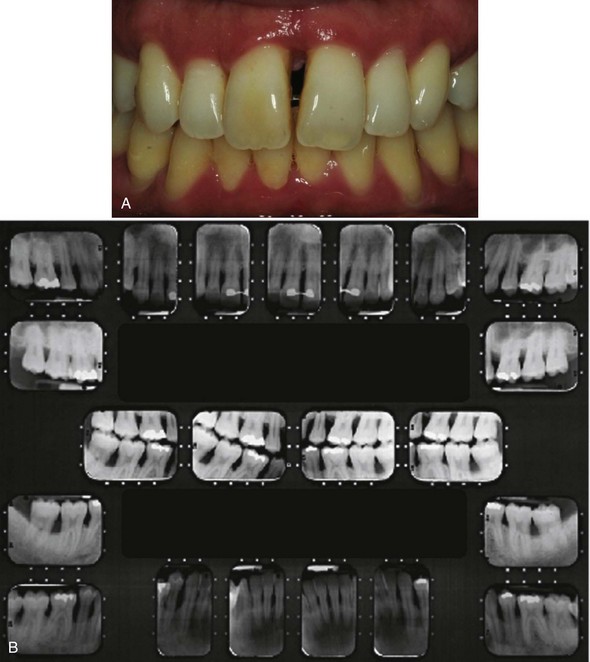

The prognosis also can be related to the height of remaining bone. Assuming bone destruction can be arrested, is there enough bone remaining to support the teeth? The answer is readily apparent in extreme cases, that is, when there is so little bone loss that tooth support is not in jeopardy (Figure 33-1), or when bone loss is so severe that the remaining bone is obviously insufficient for proper tooth support (Figure 33-2). Most patients, however, do not fit into these extreme categories. The height of remaining bone is usually somewhere in between, making bone level assessment alone insufficient for determining the overall prognosis.

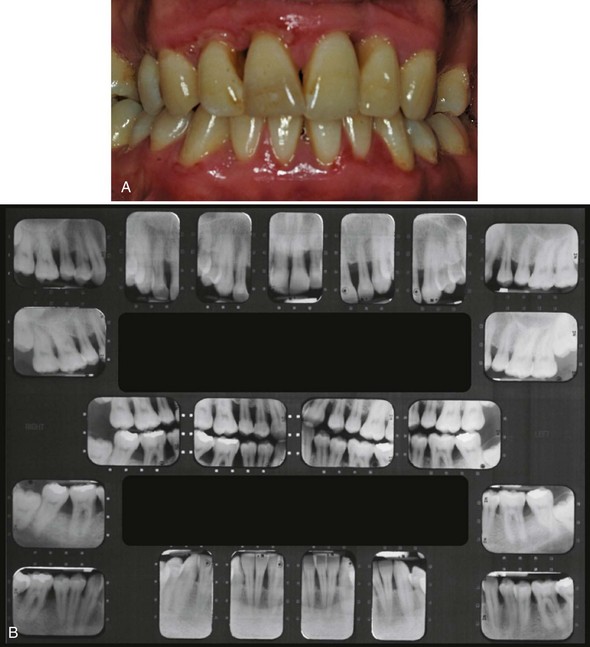

Figure 33-1 Chronic periodontitis in systemically healthy, nonsmoking 42-year-old male; overall prognosis good. A, Gingival inflammation, poor oral hygiene, and pronounced anterior overbite. B, Although local factors are present, the patient presents with adequate remaining bone support and a good prognosis, provided local factors can be controlled.

Figure 33-2 Localized aggressive periodontitis in 17-year-old girl; overall prognosis fair. A, Gingival inflammation, periodontal pockets, and pathologic migration. B, Severe bone destruction.

The type of defect also must be determined. The prognosis for horizontal bone loss depends on the height of the existing bone because it is unlikely that clinically significant bone height regeneration will be induced by therapy. In the case of angular, intrabony defects, if the contour of the existing bone and the number of osseous walls are favorable, there is an excellent chance that therapy could regenerate bone to approximately the level of the alveolar crest.45

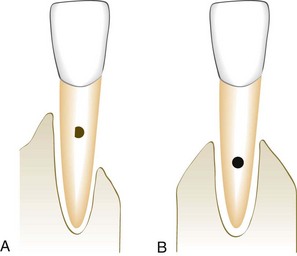

When greater bone loss has occurred on one surface of a tooth, the bone height on the less involved surfaces should be taken into consideration when determining the prognosis. Because of the greater height of bone in relation to other surfaces, the center of rotation of the tooth will be nearer the crown (Figure 33-3). This results in a more favorable distribution of forces to the periodontium and less tooth mobility.49

Figure 33-3 Prognosis for tooth A is better than for tooth B, despite less bone on one of the surfaces of A. Because the center of rotation of tooth A is closer to the crown, the distribution of occlusal forces to the periodontium is more favorable than in B.

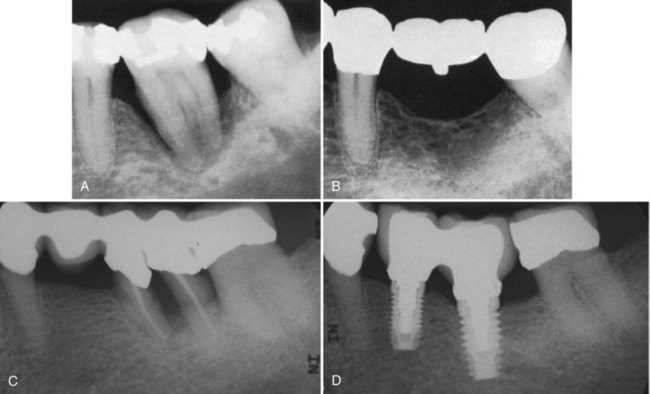

In dealing with a tooth with a questionable prognosis, the chances of successful treatment should be weighed against any benefits that would accrue to the adjacent teeth if the tooth under consideration were extracted. Strategic extraction of teeth was first proposed as a means of improving the overall prognosis of adjacent teeth and/or enhancing the prosthetic treatment plan.9 It has now been expanded to include the extraction of teeth with a questionable prognosis to enhance the likelihood of partial restoration of the bone supporting of the adjacent teeth (Figure 33-4 A to D) or successful implant placement. With the growing evidence of the long-term success of dental implants, it is proposed that a “watch and wait” approach may allow an area to deteriorate to the point that placing an implant is no longer a viable option. This means that the practitioner should weigh the potential success of one treatment option (extraction and implant placement) versus the other (periodontal therapy and maintenance) carefully when assigning a prognosis to questionable teeth.20

Figure 33-4 Extraction of severely involved tooth to preserve bone on adjacent teeth. A, Extensive bone destruction around the mandibular first molar. B, Radiograph made  years after extraction of the first molar and replacement by a prosthesis. Note the excellent bone support. C, Extraction of periodontally involved bicuspid and molar. D, Implant replacement of both teeth.

years after extraction of the first molar and replacement by a prosthesis. Note the excellent bone support. C, Extraction of periodontally involved bicuspid and molar. D, Implant replacement of both teeth.

(Courtesy of Dr. S. Angha, University of California, Los Angeles.)

Plaque Control

Bacterial plaque is the primary etiologic factor associated with periodontal disease (see Chapter 23). Therefore effective removal of plaque on a daily basis by the patient is critical to the success of periodontal therapy and to the prognosis.

Patient Compliance and Cooperation

The prognosis for patients with gingival and periodontal disease is critically dependent on the patient’s attitude, desire to retain the natural teeth, and willingness and ability to maintain good oral hygiene. Without these, treatment cannot succeed. Patients should be clearly informed of the important role they must play for treatment to succeed. If patients are unwilling or unable to perform adequate plaque control and to receive the timely periodic maintenance checkups and treatments that the dentist deems necessary, the dentist can (1) refuse to accept the patient for treatment or (2) extract teeth that have a hopeless or poor prognosis and perform scaling and root planing on the remaining teeth. The dentist should make it clear to the patient and in the patient record that further treatment is needed but will not be performed because of a lack of patient cooperation.

Systemic and Environmental Factors

Smoking

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that smoking may be the most important environmental risk factor impacting the development and progression of periodontal disease (see Chapter 5). Therefore it should be made clear to the patient that a direct relationship exists between smoking and the prevalence and incidence of periodontitis. In addition, patients should be informed that smoking affects not only the severity of periodontal destruction but also the healing potential of the periodontal tissues. As a result, patients who smoke do not respond as well to conventional periodontal therapy as patients who have never smoked.43,44 Therefore the prognosis in patients who smoke and have slight to moderate periodontitis is generally fair to poor. In patients with severe periodontitis, the prognosis may be poor to hopeless.

However, it should be emphasized that smoking cessation can affect the treatment outcome and therefore the prognosis.5,17 Patients with slight-to-moderate periodontitis who stop smoking can often be upgraded to a good prognosis, whereas those with severe periodontitis who stop smoking may be upgraded to a fair prognosis.

Systemic Disease or Condition

The patient’s systemic background affects overall prognosis in several ways. For example, evidence from epidemiologic studies clearly demonstrates that the prevalence and severity of periodontitis are significantly higher in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes than in those without diabetes and that the level of control of the diabetes is an important variable in this relationship (see Chapter 5). Therefore patients at risk for diabetes should be identified as early as possible and informed of the relationship between periodontitis and diabetes. Similarly, patients diagnosed with diabetes must be informed of the impact of diabetic control on the development and progression of periodontitis. It follows that the prognosis in these cases depends on patient compliance relative to both medical and dental status. Well-controlled diabetic patients with slight-to-moderate periodontitis who comply with their recommended periodontal treatment should have a good prognosis. Similarly, in patients with other systemic disorders that could affect disease progression, prognosis improves with correction of the systemic problem.

The prognosis is questionable when surgical periodontal treatment is required but cannot be provided because of the patient’s health (see Chapter 37). Incapacitating conditions that limit the patient’s performance of oral procedures (e.g., Parkinson’s disease) also adversely affect the prognosis. Newer “automated” oral hygiene devices, such as electric toothbrushes, may be helpful for these patients and may improve their prognosis (see Chapter 44).

Genetic Factors

Periodontal diseases represent a complex interaction between a microbial challenge and the host’s response to that challenge, both of which may be influenced by environmental factors such as smoking. In addition to these external factors, evidence also indicates that genetic factors may play an important role in determining the nature of the host response.18 Evidence for this type of genetic influence exists for patients with both chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Genetic polymorphisms in the interleukin-1 (IL-1) genes, resulting in increased production of IL-1β, have been associated with a significant increase in risk for severe, generalized, and chronic periodontitis.24,37 It has been demonstrated that knowledge of the patient’s IL-1 genotype and smoking status can aid the clinician in assigning a prognosis.36 Genetic factors also appear to influence serum immunoglobulin G2 (IgG2) antibody titers and the expression of FcγRII receptors on the neutrophil, both of which may be significant in aggressive periodontitis.18 Other genetic disorders, such as leukocyte adhesion deficiency type 1, can influence neutrophil function, creating an additional risk factor for aggressive periodontitis.18 Finally, the familial aggregation that is characteristic of aggressive periodontitis indicates that additional, as yet unidentified genetic factors may be important in susceptibility to this form of disease (see Chapter 18).

The influence of genetic factors on prognosis is not simple. Although microbial and environmental factors can be altered through conventional periodontal therapy and patient education, genetic factors currently cannot be altered. However, detection of genetic variations linked to periodontal disease can potentially influence the prognosis in several ways. First, early detection of patients at risk because of genetic factors can lead to early implementation of preventive and treatment measures for these patients. Second, identification of genetic risk factors later in the disease or during the course of treatment can influence treatment recommendations, such as the use of adjunctive antibiotic therapy or increased frequency of maintenance visits. Third, identification of young individuals who have not been evaluated for periodontitis, but who are recognized as being at risk because of the familial aggregation seen in aggressive periodontitis, can lead to the development of early intervention strategies. In each of these cases, early diagnosis, intervention, and alterations in the treatment regimen may lead to an improved prognosis for the patient.

Stress

Physical and emotional stress, as well as substance abuse, may alter the patient’s ability to respond to the periodontal treatment performed (see Chapter 5). These factors must be realistically faced when attempting to establish a prognosis.

Local Factors

Plaque and Calculus

The microbial challenge presented by bacterial plaque and calculus is the most important local factor in periodontal diseases. Therefore, in most cases, having a good prognosis depends on the ability of the patient and the clinician to remove these etiologic factors (see Chapters 22 and 23).

Subgingival Restorations

Subgingival margins may contribute to increased plaque accumulation, increased inflammation, and increased bone loss4,40,48 when compared with supragingival margins. Furthermore, discrepancies in these margins (e.g., overhangs) can negatively impact the periodontium (see Chapter 22). The size of these discrepancies and duration of their presence are important factors in the amount of destruction that occurs. In general, however, a tooth with a discrepancy in its subgingival margins has a poorer prognosis than a tooth with well-contoured supragingival margins.

Anatomic Factors

Anatomic factors that may predispose the periodontium to disease and therefore affect the prognosis include short, tapered roots with large crowns; cervical enamel projections and enamel pearls; intermediate bifurcation ridges; root concavities; and developmental grooves. The clinician must also consider root proximity and the location and anatomy of furcations when developing a prognosis.

Prognosis is poor for teeth with short, tapered roots and relatively large crowns (Figure 33-5). Because of the disproportionate crown-to-root ratio and the reduced root surface available for periodontal support,21 the periodontium may be more susceptible to injury by occlusal forces.

Figure 33-5 Generalized aggressive periodontitis and poor crown-to-root ratio in 24-year-old patient; overall prognosis poor. A, generalized periodontal attachment loss and pocket formation. B, Moderate to advanced bone destruction. The contrast between the well-formed crowns and the relatively short, tapered roots worsens the prognosis.

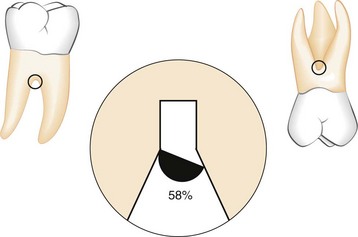

Cervical enamel projections (CEPs) are flat, ectopic extensions of enamel that extend beyond the normal contours of the cementoenamel junction.32 CEPs extend into the furcation of 28.6% of mandibular molars and 17% of maxillary molars.32 CEPs are most likely to be found on buccal surfaces of maxillary second molars.16,50 Enamel pearls are larger, round deposits of enamel that can be located in furcations or other areas on the root surface.39 Enamel pearls are seen less frequently (1.1% to 5.7% of permanent molars; 75% appearing in maxillary third molars39) than CEPs. An intermediate bifurcation ridge has been described in 73% of mandibular first molars, crossing from the mesial to the distal root at the midpoint of the furcation.11 The presence of these enamel projections on the root surface interferes with the attachment apparatus and may prevent regenerative procedures from achieving their maximum potential. Therefore their presence may have a negative effect on the prognosis for an individual tooth.

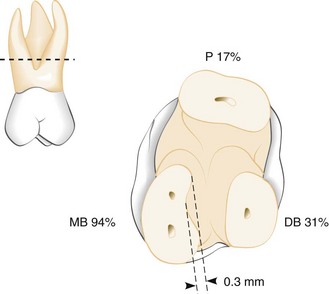

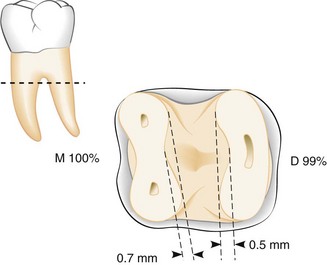

Scaling with root planing is a fundamental procedure in periodontal therapy. Anatomic factors that decrease the efficiency of this procedure can have a negative impact on the prognosis. Therefore the morphology of the tooth root is an important consideration when discussing prognosis. Root concavities exposed through loss of attachment can vary from shallow flutings to deep depressions. They appear more marked on maxillary first premolars, the mesiobuccal root of the maxillary first molar, both roots of mandibular first molars, and the mandibular incisors6,7 (Figures 33-6 and 33-7). Any tooth, however, can have a proximal concavity.13 Although these concavities increase the attachment area and produce a root shape that may be more resistant to torquing forces, they also create areas that can be difficult for both the dentist and the patient to clean.

Figure 33-6 Root concavities in maxillary first molars sectioned 2 mm apical to the furca. The furcal aspect of the root is concave in 94% of the mesiobuccal (MB) roots, 31% of the distobuccal (DB) roots, and 17% of the palatal (P) roots. The deepest concavity is found in the furcal aspects of the mesiobuccal root (mean concavity, 0.3 mm). The furcal aspect of the buccal roots diverges toward the palate in 97% of teeth (mean divergence, 22 degrees).

(Redrawn from Bower RC: J Periodontol 50:366, 1979.)

Figure 33-7 Root concavities in mandibular first molars sectioned 2 mm apical to the furca. Concavity of the furcal aspect was found in 100% of mesial (M) roots and 99% of distal (D) roots. Deeper concavity was found in the mesial roots (mean concavity, 0.7 mm).

(Redrawn from Bower RC: J Periodontol 50:366, 1979.)

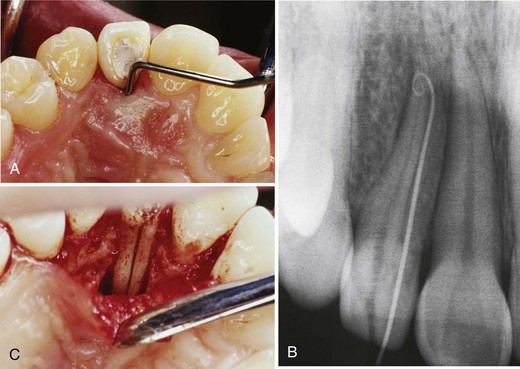

Other anatomic considerations that present accessibility problems are developmental grooves, root proximity, and furcation involvements. The presence of any of these can worsen the prognosis. Developmental grooves, which sometimes appear in the maxillary lateral incisors (palatogingival groove51; Figure 33-8) or in the lower incisors, create an accessibility problem.10,15 They initiate on enamel and can extend a significant distance on the root surface, providing a plaque-retentive area that is difficult to instrument. These palatogingival grooves are found on 5.6% of maxillary lateral incisors and 3.4% of maxillary central incisors.23 Similarly, root proximity can result in interproximal areas that are difficult for the clinician and patient to access. Finally, access to the furcation area is usually difficult to obtain. In 58% of maxillary and mandibular first molars, the furcation entrance diameter is narrower than the width of conventional periodontal curettes7 (Figure 33-9). Maxillary first premolars present the greatest difficulties, and therefore their prognosis is usually unfavorable when the lesion reaches the mesiodistal furcation. Maxillary molars also present some difficulty; sometimes their prognosis can be improved by resecting one of the buccal roots (see Chapter 62), thereby improving access to the area. When mandibular first molars or buccal furcations of maxillary molars offer good access to the furcation area, their prognosis is usually better.

Figure 33-8 Palatogingival groove. A, Probe in place to indicate a deep pocket along the palatogingival groove. B, Radiograph with a gutta percha point placed in the pocket. C, The area is surgically opened. Note the palatogingival groove along the entire palatal portion of the root.

(Courtesy of Dr. Nadia Chugal, University of California, Los Angeles.)

Tooth Mobility

The principal causes of tooth mobility are loss of alveolar bone, inflammatory changes in the periodontal ligament, and trauma from occlusion. Tooth mobility caused by inflammation and trauma from occlusion may be correctable.38 However, tooth mobility resulting from loss of alveolar bone is not likely to be corrected. The likelihood of restoring tooth stability is inversely proportional to the extent to which mobility is caused by loss of supporting alveolar bone. A longitudinal study of the response to treatment of teeth with different degrees of mobility revealed that pockets on clinically mobile teeth do not respond as well to periodontal therapy as pockets on nonmobile teeth exhibiting the same initial disease severity.12 Another study, however, in which ideal plaque control was attained, found similar healing in both hypermobile and firm teeth.45 The stabilization of tooth mobility through the use of splinting may have a beneficial impact on the overall and individual tooth prognosis.

Prosthetic and Restorative Factors

The overall prognosis requires a general consideration of bone levels (evaluated radiographically) and attachment levels (determined clinically) to establish whether enough teeth can be saved either to provide a functional and aesthetic dentition or to serve as abutments for a useful prosthetic replacement of the missing teeth.

At this point, the overall prognosis and the individual tooth prognosis overlap because the prognosis for key individual teeth may affect the overall prognosis for prosthetic rehabilitation. For example, saving or losing a key tooth may determine whether other teeth are saved or extracted or whether the prosthesis used is fixed or removable (see Figure 33-4). When few teeth remain, the prosthodontic needs become more important, and sometimes periodontally treatable teeth may have to be extracted if they are not compatible with the design of the prosthesis.

Teeth that serve as abutments are subjected to increased functional demands. More rigid standards are required when evaluating the prognosis of teeth adjacent to edentulous areas. A tooth with a post that has undergone endodontic treatment is more likely to fracture when serving as a distal abutment supporting a distal removable partial denture. Additionally, special oral hygiene measures must be instituted in these areas.

Caries, Nonvital Teeth, and Root Resorption

For teeth mutilated by extensive caries, the feasibility of adequate restoration and endodontic therapy should be considered before undertaking periodontal treatment. Extensive idiopathic root resorption or root resorption resulting from orthodontic therapy jeopardizes the stability of teeth and adversely affects the response to periodontal treatment. The periodontal prognosis of treated nonvital teeth does not differ from that of vital teeth. New attachment can occur to the cementum of both nonvital and vital teeth.

Relationship Between Diagnosis and Prognosis

Many of the criteria used in the diagnosis and classification of the different forms of periodontal disease1 (see Chapter 4) are also used in developing a prognosis (see Box 33-1). Factors such as patient age, severity of disease, genetic susceptibility, and presence of systemic disease are important criteria in the diagnosis of the condition, as well as important in developing a prognosis. These common factors suggest that for any given diagnosis, there should be an expected prognosis under ideal conditions. This section discusses the potential prognoses of the various periodontal diseases outlined in Chapter 4.

Prognosis for Patients with Gingival Disease

Dental Plaque–Induced Gingival Diseases

Gingivitis Associated with Dental Plaque Only

Plaque-induced gingivitis is a reversible disease that occurs when bacterial plaque accumulates at the gingival margin.29,31 This disease can occur on a periodontium that has experienced no attachment loss or on a periodontium with nonprogressing attachment loss. In either case, the prognosis for patients with gingivitis associated with dental plaque only is good, provided all local irritants are eliminated, other local factors contributing to plaque retention are eliminated, gingival contours conducive to the preservation of health are attained, and the patient cooperates by maintaining good oral hygiene.

Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases Modified by Systemic Factors

The inflammatory response to bacterial plaque at the gingival margin can be influenced by systemic factors, such as endocrine-related changes associated with puberty, menstruation, pregnancy, and diabetes, and the presence of blood dyscrasias. In many cases, the frank signs of gingival inflammation that occur in these patients are seen in the presence of relatively small amounts of bacterial plaque. Therefore the long-term prognosis for these patients depends not only on control of bacterial plaque but also on control or correction of the systemic factor(s).

Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases Modified by Medications

Gingival diseases associated with medications include drug-influenced gingival enlargement, often seen with phenytoin, cyclosporine, and nifedipine and in oral contraceptive–associated gingivitis. In drug-influenced gingival enlargement, reductions in dental plaque can limit the severity of the lesions. However, plaque control alone does not prevent development of the lesions, and surgical intervention is usually necessary to correct the alterations in gingival contour. Continued use of the drug usually results in recurrence of the enlargement, even after surgical intervention (see Chapter 9). Therefore the long-term prognosis depends on whether the patient’s systemic problem can be treated with an alternative medication that does not have gingival enlargement as a side effect.

In oral contraceptive–associated gingivitis, frank signs of gingival inflammation can be seen in the presence of relatively little plaque. Therefore, as seen in plaque-induced gingival diseases modified by systemic factors, the long-term prognosis in these patients depends on not only the control of bacterial plaque but also on the likelihood of continued use of the oral contraceptive.

Gingival Diseases Modified by Malnutrition

Although malnutrition has been suspected to play a role in the development of gingival diseases, most clinical studies have not shown a relationship between the two. One possible exception is severe vitamin C deficiency. In early experimental vitamin C deficiency, gingival inflammation and bleeding on probing were independent of plaque levels present. The prognosis in these patients may depend on the severity and duration of the deficiency and on the likelihood of reversing the deficiency through dietary supplementation.

Non–Plaque-Induced Gingival Lesions

Non–plaque-induced gingivitis can be seen in patients with a variety of bacterial, fungal, and viral infections.19 Since the gingivitis in these patients is not usually attributed to plaque accumulation, prognosis depends on elimination of the source of the infectious agent. Dermatologic disorders, such as lichen planus, pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, erythema multiforme, and lupus erythematosus, also can manifest in the oral cavity as atypical gingivitis (see Chapter 12). Prognosis for these patients is linked to management of the associated dermatologic disorder. Finally, allergic, toxic, and foreign body reactions, as well as mechanical and thermal trauma, can result in gingival lesions. Prognosis for these patients depends on elimination of the causative agent.

Prognosis for Patients with Periodontitis

Chronic Periodontitis

Chronic periodontitis is a slowly progressive disease associated with well-known local environmental factors.27 It can present in a localized or generalized form (see Chapter 16). In cases in which the clinical attachment loss and bone loss are not very advanced (slight-to-moderate periodontitis), the prognosis is generally good, provided the inflammation can be controlled through good oral hygiene and the removal of local plaque-retentive factors (see Figure 33-1). In patients with more severe disease, as evidenced by furcation involvement and increasing clinical mobility, or in patients who are noncompliant with oral hygiene practices, the prognosis may be downgraded to fair to poor.

Aggressive Periodontitis

Aggressive periodontitis can present in a localized or a generalized form.26 Two common features of both forms are (1) rapid attachment loss and bone destruction in an otherwise clinically healthy patient and (2) a familial aggregation. These patients often present with limited microbial deposits that seem inconsistent with the severity of tissue destruction. However, the deposits that are present often have elevated levels of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans or Porphyromonas gingivalis. These patients also may present with phagocyte abnormalities and a hyperresponsive monocyte/macrophage phenotype. These clinical, microbiologic, and immunologic features would suggest that patients diagnosed with aggressive periodontitis would have a poor prognosis.

However, the clinician should consider additional specific features of the localized form of disease when determining the prognosis (see Figure 33-2). Localized aggressive periodontitis usually occurs around the age of puberty and is localized to first molars and incisors. The patient often exhibits a strong serum antibody response to the infecting agents, which may contribute to localization of the lesions (see Chapter 18). When diagnosed early, these cases can be treated conservatively with oral hygiene instruction and systemic antibiotic therapy,42 resulting in an excellent prognosis. When more advanced disease occurs, the prognosis can still be good if the lesions are treated with debridement, local and systemic antibiotics, and regenerative therapy.30,52

In contrast, although patients with generalized aggressive periodontitis also are young patients (usually under age 30), they present with generalized interproximal attachment loss and a poor antibody response to infecting agents. Secondary contributing factors, such as cigarette smoking, are often present. These factors, coupled with the alterations in host defense seen in many of these patients, may result in a case that does not respond well to conventional periodontal therapy (scaling with root planing, oral hygiene instruction, and surgical intervention). Therefore these patients often have a fair, poor, or questionable prognosis, and the use of systemic antibiotics should be considered to help control the disease (see Chapter 47).

Periodontitis as Manifestation of Systemic Diseases

Periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic diseases can be divided into the following two categories22,28:

Although the primary etiologic factor in periodontal diseases is bacterial plaque, systemic diseases that alter the ability of the host to respond to the microbial challenge presented may affect the progression of disease and therefore the prognosis for the case. For example, decreased numbers of circulating neutrophils (as in acquired neutropenias) may contribute to widespread destruction of the periodontium. Unless the neutropenia can be corrected, these patients present with a fair-to-poor prognosis. Similarly, genetic disorders that alter the way the host responds to bacterial plaque (as in leukocyte adhesion deficiency [LAD] syndrome) also can contribute to the development of periodontitis. Because these disorders generally manifest early in life, the impact on the periodontium may be clinically similar to generalized aggressive periodontitis. The prognosis in these cases will be fair to poor.

Other genetic disorders do not affect the host’s ability to combat infections but still affect the development of periodontitis. Examples include hypophosphatasia, in which patients have decreased levels of circulating alkaline phosphatase, severe alveolar bone loss, and premature loss of deciduous and permanent teeth, and the connective tissue disorder Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, in which patients may present with the clinical characteristics of aggressive periodontitis. In both examples the prognosis is fair to poor.

Necrotizing Periodontal Diseases

Necrotizing periodontal disease can be divided into necrotic diseases that affect the gingival tissues exclusively (necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis [NUG]) and necrotic diseases that affect deeper tissues of the periodontium, resulting in loss of connective tissue attachment and alveolar bone (necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis [NUP]).41,46 In NUG the primary predisposing factor is bacterial plaque. However, this disease is usually complicated by the presence of secondary factors such as acute psychologic stress, tobacco smoking, and poor nutrition, all of which can contribute to immunosuppression. Therefore superimposition of these secondary factors on a preexisting gingivitis can result in the painful, necrotic lesions characteristic of NUG. With control of both the bacterial plaque and the secondary factors, the prognosis for a patient with NUG is good. However, the tissue destruction in these cases is not reversible, and poor control of the secondary factors may make these patients susceptible to recurrence of the disease. With repeated episodes of NUG, the prognosis may be downgraded to fair.

The clinical presentation of NUP is similar to that of NUG, except the necrosis extends from the gingiva into the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. In systemically healthy patients, this progression may have resulted from multiple episodes of NUG, or the necrotizing disease may occur at a site previously affected with periodontitis. In these patients, the prognosis depends on alleviating the plaque and secondary factors associated with NUG. However, many patients presenting with NUP are immunocompromised through systemic conditions, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. In these patients the prognosis depends on not only reducing local and secondary factors, but also on dealing with the systemic problem (see Chapter 40).

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Because of the complexity and variability of a patient’s periodontal disease and the individual systemic factors that influence prognosis, it is not possible to develop an accurate methodology for determining long-term success of therapy. The clinician needs to have experience with treating many different patients, as well as the ability to synthesize the data from each patient to develop a prognosis.

Determining the prognosis after assessing a patient’s response to initial therapy will give a more accurate evaluation than the prognosis put together before treatment began. The patient’s ability to maintain low levels of plaque is the most significant factor affecting treatment outcomes. Smoking has a negative influence on prognosis as does the presence of systemic diseases such as diabetes. Single-rooted teeth have a better prognosis than multirooted teeth with the same amount of periodontal destruction. Similarly, advanced tooth mobility, if untreated, can negatively affect prognosis.

In general, younger patients have a greater capacity for healing, repair, and regeneration than older patients, so that in patients with the same diagnosis, systemic status, plaque scores, and anatomic factors, the younger patients will respond better to periodontal treatment. This obviously refers to patients with the same prognosis, since patients with aggressive periodontitis who are frequently younger have a poorer prognosis than older patients with chronic periodontitis.

In advanced cases, prognosis may be better established after reviewing the effectiveness of phase I therapy.

Determination of the prognosis of a tooth or teeth can be difficult, particularly for teeth with previous disease. Many factors can influence disease progression and the response to therapy, and the specific influence of any one factor is unknown and likely different from one patient to another. In addition, each patient can respond differently at different times. All these issues make determination of a prognosis difficult.

Therefore the prognosis is often determined after initial treatment is provided, assuming a favorable outcome. The prognosis is delayed until after initial therapy because the etiology depends on the host response. During initial therapy, the patient’s motivation and commitment, acknowledged as critical in all periodontal therapy, also can be determined, as well as the host response and healing capacity of the patient. Clearly, enhancing the host response to plaque’s microbial challenge will significantly and positively influence the periodontal prognosis. Likewise, an inability to enhance the host response will negatively influence the prognosis. Either outcome, however, will allow the clinician to determine a more accurate prognosis.

Reevaluation of Prognosis after Phase I Therapy

A frank reduction in pocket depth and inflammation after phase I therapy indicates a favorable response to treatment and may suggest a better prognosis than previously assumed. If the inflammatory changes present cannot be controlled or reduced by phase I therapy, the overall prognosis may be unfavorable. In these patients, the prognosis can be directly related to the severity of inflammation. Given two patients with comparable bone destruction, the prognosis may be better for the patient with the greater degree of inflammation because a larger component of that patient’s bone destruction may be attributable to local irritants. In addition, phase I therapy allows the clinician an opportunity to work with the patient and the patient’s physician to control systemic and environmental factors such as diabetes and smoking, which may have a positive effect on prognosis if adequately controlled.

The progression of periodontitis generally occurs in an episodic manner, with alternating periods of quiescence and shorter destructive stages (see Chapter 13). No methods are available at present to determine accurately whether a given lesion is in a stage of remission or exacerbation. Advanced lesions, if active, may progress rapidly to a hopeless stage, whereas similar lesions in a quiescent stage may be maintainable for long periods. Phase I therapy will, at least temporarily, transform the prognosis of the patient with an active advanced lesion, and the lesion should be reanalyzed after completion of phase I therapy.

1 Armitage GC. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:1.

2 Becker W, Becker B, Berg L. Periodontal treatment without maintenance. A retrospective study in 44 patients. J Periodontol. 1984;55:505.

3 Becker W, Berg L, Becker B. The long-term evaluation of periodontal treatment and maintenance in 95 patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1984;4:54.

4 Bjorn AL, Bjorn H, Grkovic B. Marginal fit of restorations and its relation to periodontal bone levels. I. Metal fillings. Odontol Rev. 1969;20:311.

5 Bolin A, Eklund G, Frithiof L, et al. The effect of changed smoking habits on marginal alveolar bone loss: a longitudinal study. Swed Dent J. 1993;17:211.

6 Bower RC. Furcation morphology relative to periodontal treatment: furcation entrance architecture. J Periodontol. 1979;50:23.

7 Bower RC. Furcation morphology relative to periodontal treatment–furcation root surface anatomy. J Periodontol. 1979;50:366.

8 Chace RSr, Low SB. Survival characteristics of periodontally involved teeth: a 40-year study. J Periodontol. 1993;64:701.

9 Corn H, Marks MH. Strategic extractions in periodontal therapy. Dent Clin North Am. 1969;13:817.

10 Everett FG, Kramer GN. The distolingual groove in the maxillary lateral incisor: a periodontal hazard. J Periodontol. 1972;43:352.

11 Everett FG, Jump EB, Holder TD, et al. The intermediate bifurcational ridge: a study of the morphology of the bifurcation of the lower first molar. J Dent Res. 1958;37:162.

12 Flezar TJ, Knowles JW, Morrison EC, et al. Tooth mobility and periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:495.

13 Fox SC, Bosworth BL. A morphological study of proximal root concavities: a consideration in periodontal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;114:811.

14 Ghaia S, Bissada NF. Prognosis and actual treatment outcome of periodontally involved teeth. Periodont Clin Invest. 1996;18:7.

15 Gher ME, Vernino AR. Root morphology: clinical significance in pathogenesis and treatment of periodontal disease. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980;101:627.

16 Grewe JM, Meskin LH, Miller T. Cervical enamel projections: prevalence, location, and extent; with associated periodontal implications. J Periodontol. 1965;36:460.

17 Grossi SD, Zambon J, Machtei EE, et al. Effects of smoking and smoking cessation on healing after mechanical therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:599.

18 Hart TC, Kornman KS. Genetic factors in the pathogenesis of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 1997;14:202.

19 Holmstrup P. Non–plaque-induced gingival lesions. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:20.

20 Kao RT. Strategic extraction: a paradigm shift that is changing our profession. J Periodontol. 2008;79:971.

21 Kay S, Forscher BK, Sackett LM. Tooth root length-volume relationships: an aid to periodontal prognosis. I. Anterior teeth. Oral Surg. 1954;7:735.

22 Kinane D. Periodontitis modified by systemic factors. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:54.

23 Kogan SL. The prevalence, location and conformation of palato-radicular grooves in maxillary incisors. J Periodontol. 1986;57:2312.

24 Kornman KS, di Giovine FS. Genetic variations in cytokine expression: a risk factor for severity of adult periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:327.

25 Kwok V, Caton J. Prognosis revisited: a system for assigning periodontal prognosis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:2063.

26 Lang N, Bartold PM, Cullinan M, et al. Consensus report: aggressive periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:53.

27 Lindhe J, Ranney R, Lamster I, et al. Consensus report: chronic periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:38.

28 Lindhe J, Ranney R, Lamster I, et al. Consensus report: periodontitis as a manifestation of systemic diseases. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:64.

29 Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177.

30 Mabry T, Yukna R, Sepe W. Freeze-dried bone allografts with tetracycline in the treatment of juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56:74.

31 Mariotti A. Dental plaque–induced gingival disease. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:7.

32 Masters DH, Hoskins SW. Projection of cervical enamel into molar furcations. J Periodontol. 1964;35:49.

33 McGuire MK. Prognosis versus actual outcome: a long-term survey of 100 treated periodontal patients under maintenance care. J Periodontol. 1991;62:51.

34 McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. II. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in developing an accurate prognosis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:658.

35 McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. III. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in accurately predicting tooth survival. J Periodontol. 1996;67:666.

36 McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual outcome. IV. The effectiveness of clinical parameters and IL-1 genotype in accurately predicting prognoses and tooth survival. J Periodontol. 1999;70:49.

37 Michalowicz BS, Diehl SR, Gunsolley JC, et al. Evidence of a substantial genetic basis for risk of adult periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1699.

38 Morris ML. The diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of loose tooth. Oral Surg. 1953;6:1037.

39 Moskow BS, Canut PM. Studies on root enamel. 2. Enamel pearls: a review of their morphology, localization, nomenclature, occurrence, classification, histogenesis and incidence. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:275.

40 Newcomb GM. The relationship between the location of subgingival crown margins and gingival inflammation. J Periodontol. 1974;45:151.

41 Novak MJ. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:74.

42 Novak MJ, Polson AM, Adair SM. Tetracycline therapy in patients with early juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1988;59:366.

43 Preber J, Bergström J. The effect of non-surgical treatment on periodontal pockets in smokers and non-smokers. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:319.

44 Renvert S, Dahlen G, Wikström M. The clinical and microbiological effects of non-surgical periodontal therapy in smokers and non-smokers. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:153.

45 Rosling B, Nyman S, Lindhe J. The effect of systematic plaque control on bone regeneration in infrabony pockets. J Clin Periodontol. 1976;3:38.

46 Rowland RW. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:65.

47 Shapiro N. Retaining periodontally “hopeless” teeth: a case report. J Am Dent Assoc. 1994;125:596.

48 Silness J. Periodontal conditions in patients treated with dental bridges. III. The relationship between the location of the crown margin and the periodontal condition. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:225.

49 Sorrin S, Burman LR. A study of cases not amenable to periodontal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1944;31:204.

50 Tsatsas B, Mandi F, Kerani S. Cervical enamel projections in the molar teeth. J Periodontol. 1973;44:312.

51 Withers JA, Brunsvold MA, Killoy WJ, et al. The relationship of palato-gingival grooves to localized periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1981;52:41.

52 Yukna R, Sepe W. Clinical evaluation of localized periodontosis defects with freeze-dried bone allografts combined with local and systemic tetracyclines. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 1982;5:9.