CHAPTER 58 Treatment of Gingival Enlargement

Treatment of gingival enlargement is based on an understanding of the cause and underlying pathologic changes (see Chapter 9). Gingival enlargements are of special concern to the patient and dentist because they pose problems in plaque control, function (including mastication, tooth eruption, and speech), and esthetics. Because gingival enlargements differ in cause, treatment of each type is best considered individually.

Chronic Inflammatory Enlargement

Chronic inflammatory enlargements are soft and discolored and are caused principally by edema and cellular infiltration. These gingival enlargements are treated by scaling and root planing, provided the size of the enlargement does not interfere with complete removal of deposits from the involved tooth surfaces.

When chronic inflammatory gingival enlargements include a significant fibrotic component that does not undergo shrinkage after scaling and root planing or are of such size that they obscure deposits on the tooth surfaces and interfere with access to them, surgical removal is the treatment of choice. Two techniques are available for this purpose: gingivectomy and flap operation.

Selection of the appropriate technique depends on the size of the enlargement and character of the tissue. When the enlarged gingiva remains soft and friable even after scaling and root planing, a gingivectomy is used to remove it because a flap requires a firmer tissue to perform the incisions and other steps in the technique. However, if the gingivectomy incision removes all of the attached, keratinized gingiva, which will create a mucogingival problem, then the flap technique is indicated.

Tumorlike inflammatory enlargements are treated by gingivectomy as follows:

For the flap operation, see Chapters 57 and 59 and the following discussion of the flap technique for drug-induced enlargements.

Periodontal and Gingival Abscesses

The reader is referred to Chapter 42 for a complete discussion of abscess treatment.

Drug-Associated Gingival Enlargement

Gingival enlargement has been associated with the administration of three different types of drugs: anticonvulsants, calcium channel blockers, and the immunosuppressant, cyclosporine. Chapter 9 provides a comprehensive review of the clinical and microscopic features and pathogenesis of gingival enlargement induced by these drugs.

Examination of cases of drug-induced gingival enlargement reveals the overgrown tissues to have two components: a fibrotic type caused by the drug and an inflammatory type induced by bacterial plaque. Although the fibrotic and inflammatory components present in the enlarged gingiva are the result of distinct pathologic processes, they almost always are observed in combination. The role of bacterial plaque in the overall pathogenesis of drug-induced gingival enlargement is not clear. Some studies indicate that plaque is a prerequisite for gingival enlargement,10 whereas others suggest that the presence of plaque is a consequence of its accumulation caused by the enlarged gingiva.

Treatment Options

Treatment of drug-induced gingival enlargement should be based on the medication being used and the clinical features of the case.

First, consideration should be given to the possibility of discontinuing the drug8,11 or changing the medication. These possibilities should be examined with the patient’s physician. Simple discontinuation of the offending drug is usually not practical, but its substitution with another medication might be an option. If any drug substitution is attempted, it is important to allow a 6- to 12-month period to elapse between discontinuation of the offending drug and the possible resolution of gingival enlargement. The decision to implement surgical treatment is made after this time period has elapsed.

Alternative medications to the anticonvulsant phenytoin include carbamazepine7 and valproic acid, both of which have been reported to have a lesser effect in inducing gingival enlargement.

For patients taking nifedipine, which has a reported prevalence of gingival enlargement of up to 44%, other calcium channel blockers, such as diltiazem or verapamil, may be viable alternatives.22 Their reported prevalence of inducing gingival enlargement is 20% and 4%, respectively.4,9,15 Also, consideration may be given to the use of another class of antihypertensive medications rather than calcium channel blockers, none of which is known to induce gingival enlargement.

Drug substitutions for cyclosporine are more limited. Tacrolimus is another immunosuppressant that has been used on organ transplant recipients. The incidence of gingival enlargement in patients under tacrolimus therapy is approximately 65% lower than in those taking cyclosporine.2 Clinical trials have also shown that the substitution of cyclosporine by tacrolimus results in a significant decrease in the severity of gingival enlargement when compared to patients who are kept on cyclosporine therapy24; in another study,13 the same drug substitution resulted in a strong decrease or complete resolution of gingival enlargement in over 70% of the patients initially presenting with cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement.13 Therefore the dental practitioner should consult with the treating transplantation physician to investigate the possibility of a change in immunosuppressant therapy as one of the steps in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement.

Administration of the antibiotic azithromycin has been shown to decrease the severity of gingival enlargement induced by administration of cyclosporine. A 3-day course of systemic azithromycin significantly decreased gingival enlargement, and the effect was observed as early as 7 to 30 days after initiation of antibiotic therapy.23 The effect of azithromycin in decreasing cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement is significantly greater than that observed with an improvement in oral hygiene.18 Topical administration of azithromycin in the form of a toothpaste also decreased the severity of cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement.2

Second, the clinician should emphasize plaque control as the first step in the treatment of drug-induced gingival enlargement. Although the exact role played by bacterial plaque is not well understood, evidence suggests that good oral hygiene and frequent professional removal of plaque decrease the degree of gingival enlargement and improve overall gingival health.8,10,22 The presence of drug-induced enlargement is associated with pseudopocket formation, frequently with abundant plaque accumulation. This may lead to the development of periodontitis. Therefore meticulous plaque control helps maintain attachment levels. Also, adequate plaque control may aid in preventing the recurrence of gingival enlargement in surgically treated cases.

Third, in some patients, gingival enlargement persists even after careful consideration of the previous approaches. These patients may require surgery, either gingivectomy or the periodontal flap.

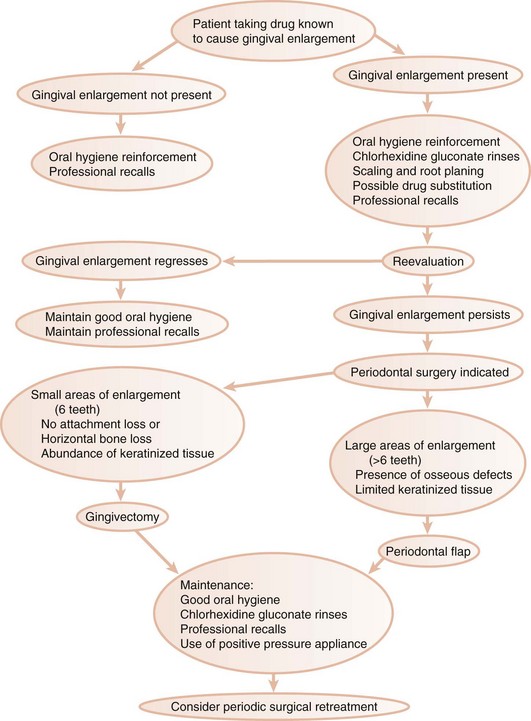

Figure 58-1 presents a decision tree outlining the sequence of events and options in the treatment of drug-induced gingival enlargement.

Gingivectomy

Gingivectomy has the advantage of simplicity and quickness but presents the disadvantages of postoperative discomfort and increased chance of postoperative bleeding. It also sacrifices keratinized tissue and does not allow for osseous recontouring if it is necessary. The clinician’s decision between the two surgical techniques available must consider the extent of the area to be operated, the presence of periodontitis and osseous defects, and the location of the base of the pockets in relation to the mucogingival junction.

In general, small areas (up to six teeth) of drug-induced gingival enlargement with no evidence of attachment loss (and therefore no anticipated need for osseous surgery) can effectively be treated with the gingivectomy technique. An important consideration is the amount of keratinized tissue that is present. At least 3 mm of keratinized gingiva in the apicocoronal direction should remain after the surgery is completed.

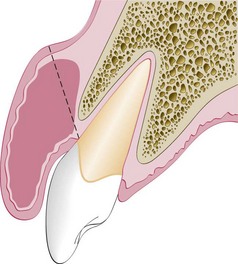

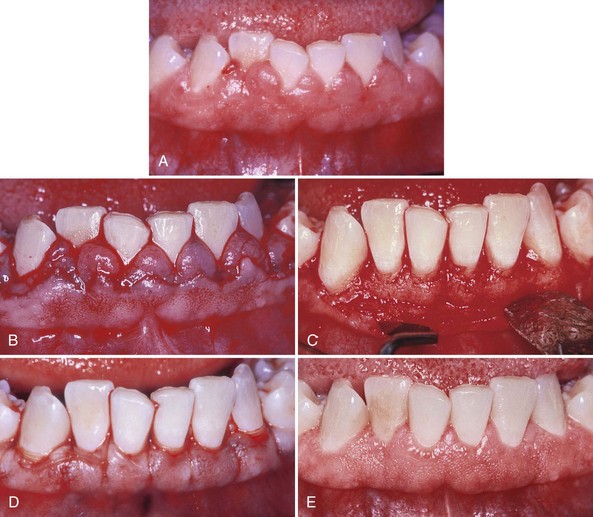

Chapter 56 describes the gingivectomy technique in detail. Figure 56-6 Figure 56-7 Figure 56-8 and Figure 58-2 depict the procedure diagrammatically, and Figure 58-3 illustrates a case of cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement treated with the gingivectomy technique.

Figure 58-2 Gingivectomy technique as used in treating patients with drug-induced gingival enlargement. The dotted line represents the external bevel incision, and the shaded area corresponds to the tissue to be excised. Gingivectomy incision may not remove the entire hyperplastic tissue (shaded area) and may leave a wide wound of exposed connective tissue.

Figure 58-3 Surgical treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement using the gingivectomy technique on a 16-year-old girl who had received a kidney allograft 2 years earlier. A, Presence of enlarged gingival tissues and pseudopocket formation; no attachment loss or evidence of vertical bone loss existed. B, Initial external bevel incision performed with a Kirkland knife. C, Interproximal tissue release achieved with an Orban knife. D and E, Gingivoplasty performed with tissue nippers and a round diamond at high speed with abundant refrigeration. F, Aspect of the surgical wound at conclusion of the surgical procedure. G, Placement of noneugenol periodontal dressing. H, Surgical area 3 months postoperatively. Note the successful elimination of enlarged gingival tissue, restoration of a physiologic gingival contour, and maintenance of an adequate band of keratinized tissue.

Gingivectomy or gingivoplasty can also be performed with electrosurgery, using a laser device (see Chapter 56). There is some preliminary evidence that the recurrence of drug-induced gingival enlargement is slower on patients treated via laser when compared to conventional gingivectomy or flap surgery.14

Flap Technique

Larger areas of gingival enlargement (more than six teeth) or areas where attachment loss and osseous defects are present should be treated by the flap technique, as should any situation in which the gingivectomy technique may create a mucogingival problem.

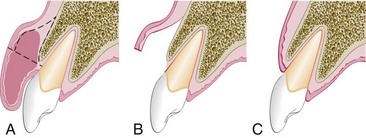

The periodontal flap technique used for the treatment of gingival enlargements is a simple variation of the one used to treat periodontitis (see Chapters 57 and 59). Figure 58-4 describes the basic steps in the technique, described as follows:

Figure 58-4 Diagram of periodontal flap treatment for drug-induced gingival enlargement. A, Initial reverse bevel incision followed by thinning of the enlarged gingival tissue; dotted lines represent incisions, and the shaded area represents the tissue portion to be excised. B, After flap elevation, enlarged portion of the gingival tissue is removed. C, The flap is placed on top of the alveolar bone and sutured.

Sutures and dressing are removed after 1 week. The patient is then instructed to initiate plaque control methods. Usually it is convenient for the patient to use chlorhexidine oral rinses once or twice daily for several weeks. Figure 58-5 illustrates a patient treated with the flap technique.

Figure 58-5 Treatment of combined cyclosporine and nifedipine–induced gingival enlargement with a periodontal flap on a 35-year-old female who had received a kidney allograft 3 years earlier. A, Presurgical clinical aspect of the lower anterior teeth, showing severe gingival enlargement. B, Initial scalloped reverse bevel incision, including maintenance of keratinized tissue and creation of surgical papillae. C, Elevation of a full-thickness flap and removal of the inner portion of the previously thinned gingival tissue. After scaling and root planing, osseous recontouring can be performed if necessary. D, The flap is positioned on top of the alveolar crest. E, Postsurgical aspect of the treated area at 12 months. Note the reduction of enlarged tissue volume and acceptable gingival health.

Recurrence of drug-induced gingival enlargement is a reality in surgically treated cases.19 As stated previously, meticulous home care,6,16 chlorhexidine gluconate rinses,16,21 and professional recall therapy can decrease the rate and the degree to which recurrence occurs. A hard, natural rubber fitted bite guard worn at night may help to control the recurrence.1,3

Even though the periodontal flap approach may be technically more difficult than the gingivectomy procedure, the postsurgical healing of the flap technique presents less discomfort and alleviates hemorrhagic problems. The primary closure of the surgical site with the flap procedure is a great advantage over the secondary open wound resulting from the gingivectomy technique. Also, postsurgical home care can be instituted earlier with the periodontal flap.5

Recurrence may occur as early as 3 to 6 months after the surgical treatment. In general, surgical results are maintained for at least 12 months. In one study, 6-month postsurgical examination of the recurrence of cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement after periodontal flap surgery or gingivectomy determined the return of increased pocket depth was slower with the flap technique.17 However, the recurrence of increased thickness of the periodontal tissue has not been objectively evaluated.

Leukemic Gingival Enlargement

Leukemic enlargement occurs in acute or subacute leukemia and is uncommon in the chronic leukemic state. The medical care of leukemic patients is often complicated by gingival enlargement and superimposed painful acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis. This interferes with masticating and creates toxic systemic reactions. The patient’s bleeding and clotting times and platelet count should be checked, and the hematologist should be consulted before periodontal treatment is instituted (see Chapter 54).

Treatment of acute gingival involvement is described in Chapter 41. After acute symptoms subside, attention is directed to correction of the gingival enlargement. The rationale for therapy is to remove the local irritating factors to control the inflammatory component of the enlargement.

The lesion is treated by scaling and root planing performed in stages with topical and local anesthesia. The initial treatment consists of gently removing the loose accumulations of bacterial plaque, performing superficial scaling, and instructing the patient in oral hygiene for plaque control. This portion of the therapy may include, at least initially, the daily use of chlorhexidine mouthwashes. Oral hygiene procedures are extremely important in these patients and should be performed by the nurse if necessary.

Progressively deeper scaling is carried out at subsequent visits. Treatments are confined to a small area of the mouth to facilitate the control of bleeding. Antibiotics are administered systemically the evening before and for 48 hours after each treatment to reduce the risk of infection.

Gingival Enlargement in Pregnancy

Treatment requires elimination of all local irritants responsible for precipitating the gingival changes in pregnancy. Elimination of local irritants early in pregnancy is a preventive measure against gingival disease. This is preferable to treatment of gingival enlargement after it occurs. Marginal and interdental gingival inflammation and enlargement are treated by scaling and root planing (see Chapters 45 and 46). Treatment of tumorlike gingival enlargements consists of surgical excision and scaling and planing of the tooth surface. The enlargement will recur unless all of the irritants are removed. Food impaction is frequently an inciting factor.

Timing of Treatment and Indications

Gingival lesions in pregnancy should be treated as soon as they are detected, although not necessarily by surgical means. Scaling and root-planing procedures and adequate oral hygiene measures may reduce the size of the enlargement. Gingival enlargements will shrink after pregnancy but may not completely disappear. After pregnancy, the entire mouth should be reevaluated, a full set of radiographs taken, and the necessary treatment undertaken.

Lesions should be removed surgically during pregnancy only if they interfere with mastication or produce an esthetic disfigurement that the patient wants removed.

In pregnancy, the emphasis should be on preventing gingival disease before it occurs and treating existing gingival disease before it worsens. All patients should be seen as early as possible in pregnancy. Those without gingival disease should be checked for potential sources of local irritation and should be instructed in plaque control procedures. Those with gingival disease should be treated promptly, before the effects of pregnancy on the gingiva become apparent. Chapter 38 presents the necessary precautions for periodontal treatment of pregnant women.

Every pregnant patient should be scheduled for periodic dental visits. At these appointments, the importance of prevention should be stressed to avoid serious periodontal problems during pregnancy.

Gingival Enlargement in Puberty

Gingival enlargement in puberty is treated by performing scaling and curettage, removing all sources of irritation, and controlling plaque. Surgical removal may be required in severe cases. The problem in these patients is recurrence that results from poor oral hygiene. Chapter 11 discusses the problems encountered during puberty.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Although gingivectomy has been appropriate in the past, most patients with gingival enlargement are better treated with a flap approach that includes resection of hyperplastic tissues. This allows access to bone defects for management, ensures an adequate postsurgical band of keratinized gingiva, and minimizes the risk of postsurgical bleeding.

Some disease entities that cause gingival enlargement have a strong tendency to recur after surgical removal. This can be lessened by adequate posttreatment control of plaque and calculus, and repeated surgical interventions should be restricted to those cases in which functional and esthetic problems caused by excessive gingival tissue are manifest or where there is evidence of ongoing loss of attachment. Gingival enlargements seen in pregnancy tend to resolve postpartum when hormonal balance of estrogen and progesterone occurs, thus, in most of these patients, surgical intervention is not needed during pregnancy.

Recurrence of Gingival Enlargement

Recurrence after treatment is the most common problem in the management of gingival enlargement. Residual local irritation and systemic or hereditary conditions causing noninflammatory gingival hyperplasia are the responsible factors.

Recurrence of chronic inflammatory enlargement immediately after treatment indicates that all irritants have not been removed. Contributory local conditions, such as food impaction and overhanging margins of restorations, are often overlooked. If the enlargement recurs after healing is complete and normal contour is attained, inadequate plaque control by the patient is the most common cause.

Recurrence during the healing period is manifested as red, beadlike, granulomatous masses that bleed on slight provocation. This is a proliferative vascular inflammatory response to local irritation, usually a fragment of calculus on the root. The condition is corrected by removing the granulation tissue and scaling and planing the root surface.

Familial, hereditary, or idiopathic gingival enlargement recurs after surgical removal even after all local irritants have been removed. The enlargement can be maintained at minimal size by preventing secondary inflammatory involvement.

The use of escharotic drugs has been recommended in the past for the removal of gingival enlargements. Their use is currently not recommended because the destructive action of the drugs is difficult to control. Injury to healthy tissue and root surfaces, delayed healing, and excessive postoperative pain are complications that often occur.

1 Aiman R. The use of positive pressure mouthpiece as a new therapy for Dilantin gingival hyperplasia. Chron Omaha Dent Soc. 1968;131:244.

2 Argani H, Pourabbas R, Hassanzadeh D, et al. Treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival overgrowth with azithromycin-containing toothpaste. Exp Clin Transplant. 2006;4:420.

3 Babcock JR. The successful use of a new therapy for Dilantin gingival hyperplasia. Periodontics. 1965;3:196.

4 Barclay S, Thomason JM, Idle JR, et al. The incidence and severity of nifedipine-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:311.

5 Camargo P, Melnick P, Pirih F, et al. Treatment of drug-induced gingival enlargement: aesthetic and functional considerations. Periodontol 2000. 2001;27:131.

6 Ciancio SG, Yaffe SJ, Catz CC. Gingival hyperplasia and diphenylhydantoin. J Periodontol. 1972;43:411.

7 Dahilof G, Preber H, Eliasson S, et al. Periodontal condition of epileptic adults treated with phenytoin or carbamazepine. Epilepsia. 1993;34:960.

8 Dongari A, O’Donnell HT, Langlais RP. Drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:543.

9 Fattore L, Stablein M, Bredfelt G, et al. Gingival hyperplasia: a side effect of nifedipine and diltiazem. Spec Care Dent. 1991;11:107.

10 Hall WB. Dilantin hyperplasia: a preventable lesion. J Periodontal Res. 1969;4:36.

11 Harel-Raviv M, Eckler M, Lalani K, et al. Nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia: a comprehensive review and analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;79:115.

12 Hernandez G, Arriba L, Lucas M, et al. Reduction of severe gingival overgrowth in a kidney transplant patient by replacing cyclosporin A with tacrolimus. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1630.

13 Margreiter R, Pohanka E, Sparacino V, et al. Open prospective multicenter study of conversion to tacrolimus therapy in renal transplant patients experiencing ciclosporin-related side-effects. Transpl Int. 2005;18:816.

14 Mavrogiannis M, Ellis JS, Seymour RA, et al. The efficacy of three different surgical techniques in the management of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:677.

15 Nery EB, Edson RG, Lee KK, et al. Prevalence of nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia. J Periodontol. 1995;66:572.

16 Nishikawa S, Tada H, Hamasaki A, et al. Nifedipine-induced gingival hyperplasia: a clinical and in vitro study. J Periodontol. 1991;62:30.

17 Pilloni A, Camargo PM, Carere M, et al. Surgical treatment of cyclosporine A- and nifedipine-induced gingival enlargement. J Periodontol. 1998;69:791.

18 Ramalho VL, Ramalho HJ, Cipullo JP, et al. Comparison of azithromycin and oral hygiene program in the treatment of cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia. Ren Fail. 2007;29:265.

19 Rees TD, Levine RA. Systemic drugs as a risk factor for periodontal disease initiation and progression. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1995;16:20.

20 Saravia ME, Svirsky JA, Friedman R. Chlorhexidine as an oral hygiene adjunct for cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia. J Dent Child. 1990;57:366.

21 Sekigucchi RT, Paixão CG, Saraiva L, et al. Incidence of tracolimus-induced gingival overgrowth in the absence of calcium-channel blockers: a short-term study. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:545.

22 Seymour RA, Jacobs DJ. Cyclosporin and the gingival tissues. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:1.

23 Tokgöz B, Sari HI, Yildiz O, et al. Effects of azithromycin on cyclosporine-induced gingival hyperplasia in renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:2699.

24 Walker RG, Cottrell S, Sharp K, et al. Conversion of cyclosporine to tacrolimus in stable renal allograft recipients: quantification of effects on the severity of gingival enlargement and hirsutism and patient-reported outcomes. Nephrology (Carlton). 2007;12:607.