CHAPTER 65 Preparation of the Periodontium for Restorative Dentistry

Periodontal health is the “sine qua non,” a prerequisite, of successful comprehensive dentistry.23 To achieve the long-term therapeutic targets of comfort, good function, treatment predictability, longevity, and ease of restorative and maintenance care, active periodontal infection must be treated and controlled before the initiation of restorative, esthetic, and implant dentistry. In addition, the residual effects of periodontal disease or anatomic aberrations inconsistent with realizing and maintaining long-term stability must be addressed. More recently, this phase of treatment includes techniques performed in anticipation of esthetic or implant dentistry, such as clinical crown lengthening, covering denuded roots, alveolar ridge retention or augmentation, and implant site development.

Rationale for Therapy

The many reasons for establishing periodontal health before performing restorative dentistry include the following45:

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

During phase I therapy, clinicians should correct any faulty restorative problems and position malposed teeth for optimization of periodontal health. In phase II therapy, crown lengthening procedures are utilized to allow proper retention of crowns. Generally this will involve flap surgery combined with osseous surgery, but in a few cases with pockets 5 mm or deeper and a wide band of keratinized gingiva, gingivectomy may be used. Clinicians should establish the level of the subgingival restorative margin and then remove bone so that it is 2 to 3 mm apical to this margin. Mucogingival procedures to correct inadequate attached keratinized gingival tissue should be completed before restorative treatments in that region. The use of regenerative materials during extractions to maintain alveolar ridge dimensions provides optimal forms of edentulous regions for idealized implant placement and pontic form.

Sequence of Treatment

Treatment sequencing should be based on logical and evidenced-based methodologies, taking into account not only the disease state encountered but also the psychologic and esthetic concerns of the patient. Because periodontal and restorative therapy is situational and specific to each patient, a plan must be adaptable to change depending on the variables encountered during the course of treatment. For example, teeth initially determined to be salvageable may be judged “hopeless,” thus altering the established treatment scheme.

Generally, the preparation of the periodontium for restorative dentistry can be divided into two phases: (1) control of periodontal inflammation with nonsurgical and surgical approaches and (2) preprosthetic periodontal surgery (Box 65-1).

Control of Active Disease

Periodontal therapy is intended to control active disease (see Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 ). In addition to the removal of root surface accretions that are primary etiologic agents, secondary local factors, such as plaque-retentive overhanging margins and untreated caries, must be addressed.13,18

Emergency Treatment

Emergency treatment is undertaken to alleviate symptoms and stabilize acute infection. This includes endodontic as well as periodontal conditions (see Chapters 42 and 51).

Extraction of Hopeless Teeth

Extraction of hopeless teeth is followed by provisionalization with fixed or removable prosthetics. Retention of hopeless teeth without periodontal treatment may result in bone loss on adjacent teeth.30 Restorative margins are refined and provisional restorations refitted after the completion of active periodontal therapy.

Oral Hygiene Measures

Oral hygiene measures, when properly applied, have been shown to reduce plaque scores and gingival inflammation28,44 (see Chapter 44). However, in patients with deep periodontal pockets (>5 mm), plaque control measures alone are insufficient in resolving subgingival infection and inflammation.5,28

Scaling and Root Planing

Scaling and root planing combined with oral hygiene measures have been demonstrated to significantly reduce gingival inflammation and the rate of progression of periodontitis3,4,29 (see Chapter 45). This applies even to patients with deep periodontal pockets5,14 (Figure 65-1).

Reevaluation

After 4 weeks the gingival tissues are evaluated to determine oral hygiene adequacy, soft tissue response, and pocket depth (see Chapter 52). This permits sufficient time for healing, reduction in inflammation and pocket depths, and gain in clinical attachment levels. in deeper pockets (>5 mm); however, plaque and calculus removal is often incomplete,42,46 with risk of future breakdown7 (Figure 65-2). As a result, periodontal surgery to access the root surfaces for instrumentation and to reduce periodontal pocket depths must be considered before restorative care may proceed.

Periodontal Surgery

Periodontal surgery may be required for some patients (see Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Chapter 59 Chapter 60 Chapter 61 Chapter 62 Chapter 63 Chapter 64 ). This should be undertaken with future restorative and implant dentistry in mind. Some procedures are intended to treat active disease successfully,11,34 and some are aimed at the preparation of the mouth for restorative or prosthetic care.47

Adjunctive Orthodontic Therapy

Orthodontic treatment has been shown to be a useful adjunctive to periodontal therapy6,16,17,22 (see Chapter 50). It should be undertaken only after active periodontal disease has been controlled. If nonsurgical treatment is sufficient, definitive periodontal pocket therapy may be postponed until after the completion of orthodontic tooth movement. This allows for the advantage of the positive bone changes that orthodontic therapy can provide. However, deep pockets and furcation invasions may require surgical access for root instrumentation in advance of orthodontic tooth movement. Failure to control active periodontitis can result in acute exacerbations and bone loss during tooth movement.9 As long as they are periodontally healthy, teeth with preexisting bone loss may be moved orthodontically without incurring additional attachment loss.36,37

Soft tissue grafting procedures are often indicated in anticipation of orthodontic therapy to increase the dimension of attached tissue.47

Preprosthetic Surgery

Management of Mucogingival Problems

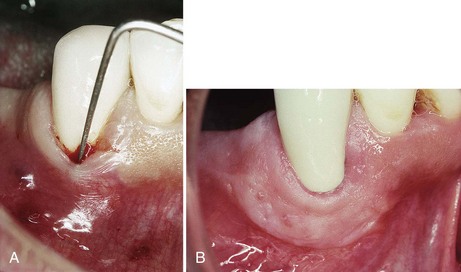

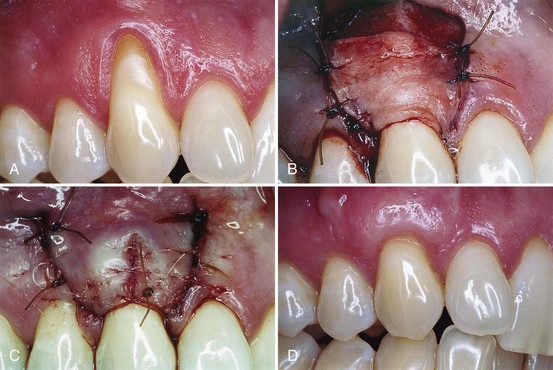

Periodontal plastic surgical procedures may be undertaken for a variety of reasons. The most common techniques include those that increase gingival dimensions and achieve root coverage. These procedures are often indicated before restoration for prosthetic reasons (Figure 65-3) and in conjunction with orthodontic tooth movement. Root coverage procedures may also be undertaken for purposes of comfort and esthetics (Figure 65-4).

Figure 65-3 In preparation for a removable partial denture, this canine has received a gingival graft to increase attached gingiva and deepen the vestibule. A, Before therapy. Note minimal attached gingiva. B, After therapy, there is abundant attached gingiva and vestibular depth.

Figure 65-4 Connective tissue graft placed under a double-papilla flap has been used to provide root coverage for a maxillary right canine. A, Maxillary canine before therapy. B, Connective tissue graft placed over denuded root surface. C, Papilla placed over connective tissue. D, Final result.

At least 2 months of healing is recommended after soft tissue grafting procedures before initiating restorative dentistry47 (see Chapter 63).

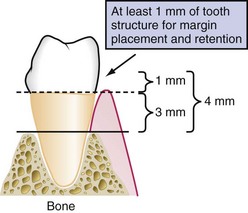

Preservation of Ridge Morphology after Tooth Extraction

Alveolar ridge resorption is a common consequence of tooth loss.1,2 Ridge preservation procedures have been shown to be useful in anticipation of the future placement of a dental implant or pontic, as well as in cases where unaided healing would result in an unesthetic deformity15,24,25,31,33 (Figure 65-5).

Figure 65-5 A, The maxillary right lateral incisor has failed endodontically, with a fistulous tract noted exiting from the attached gingiva. B, The tooth is atraumatically removed and the socket debrided while maintaining the surrounding anatomic integrity. C, In an effort to reduce ridge collapse, the socket is grafted with a combination of deproteinized bovine bone and calcium sulfate. D, Provisional fixed partial denture is placed, with an ovate pontic extending 2 mm into the socket and supporting the surrounding tissues. E and F, After 8 weeks the socket has healed, preserving the gingival and papillary architecture, in preparation for an esthetic final prosthesis. G, Final restoration.

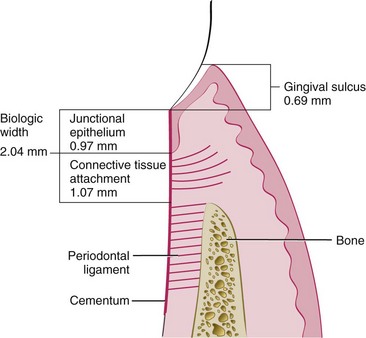

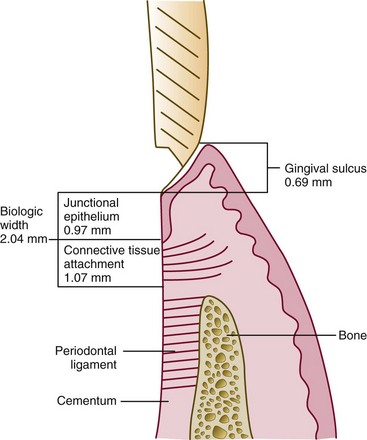

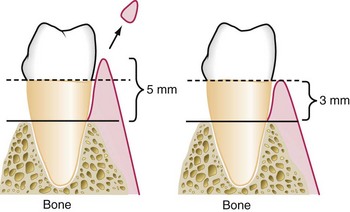

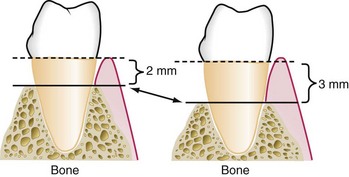

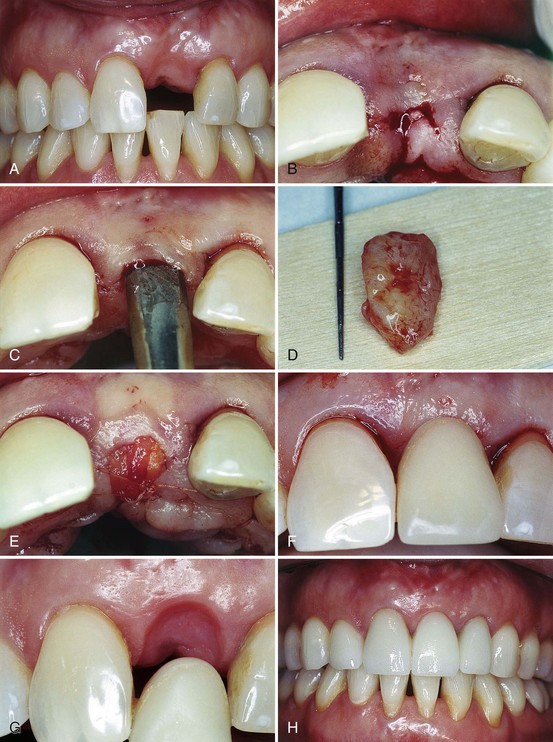

Surgical crown-lengthening procedures are performed to provide retention form to allow for proper tooth preparation, impression procedures,21 and placement of restorative margins (Figure 65-6)21 and to adjust gingival levels for esthetics.32,43 It is important that crown-lengthening surgery is done in such a manner that the biologic width is preserved. The biologic width is defined as the physiologic dimension of the junctional epithelium and connective tissue attachment (see Chapter 66). This measurement has been found to be relatively constant at approximately 2 mm (±30%).10 The healthy gingival sulcus has shown an average depth of 0.69 mm (Figure 65-7).19 It has been theorized that infringement on the biologic width by the placement of a restoration within its zone may result in gingival inflammation,19 pocket formation, and alveolar bone loss35 (Figure 65-8). Consequently, it is recommended that there be at least 3.0 mm between the gingival margin and bone crest.12,38,39,41 This allows for adequate biologic width when the restoration is placed 0.5 mm within the gingival sulcus39,41 (Figure 65-9).

Figure 65-6 Surgical crown lengthening has provided these otherwise unrestorable mandibular molars with improved retention and restorative access for successful restorations. A, Before crown lengthening. B, Crown-lengthening surgery completed. Note increased clinical crown. C, Buccal view after surgery. D, Final restorations.

Figure 65-7 The biologic width has been estimated to be about 2 mm. Efforts should be made to preserve its integrity.

Figure 65-8 Although gingival inflammation around crowns may have a variety of causes, infringement of biologic width must be considered.

Figure 65-9 Placement of the restorative margin 0.5 mm into the sulcus allows for the maintenance of the biologic width.

Surgical crown lengthening may include the removal of soft tissue or both soft tissue and alveolar bone. Reduction of soft tissue alone is indicated if there is adequate attached gingiva and more than 3 mm of tissue coronal to the bone crest (Figure 65-10). This may be accomplished by either gingivectomy or flap technique (see Chapter 58 Chapter 59 Chapter 60 Chapter 61 Chapter 62 Chapter 63 Chapter 64 Chapter 66 ). Inadequate attached gingiva and less than 3 mm of soft tissue require a flap procedure and bone recontouring (Figure 65-11). In the case of caries or tooth fracture, to ensure margin placement on sound tooth structure and retention form, the surgery should provide at least 4 mm from the apical extent of the caries or fracture to the bone crest (Figure 65-12).

With the advent of predictable implant dentistry, it is important to weigh carefully the value of crown lengthening for restorative ease as opposed to tooth removal and replacement with a dental implant (Box 65-2).

Figure 65-10 Greater than 3 mm of soft tissue between the bone and gingival margin, with adequate attached gingiva, allows crown lengthening by gingivectomy.

Figure 65-11 With less than 3 mm of soft tissue between the bone and gingival margin, or less-than-adequate attached gingiva, a flap procedure and osseous recontouring are required for crown lengthening.

Figure 65-12 In the case of caries or fracture, at least 1 mm of sound tooth structure should be provided above the gingival margin for proper restoration.

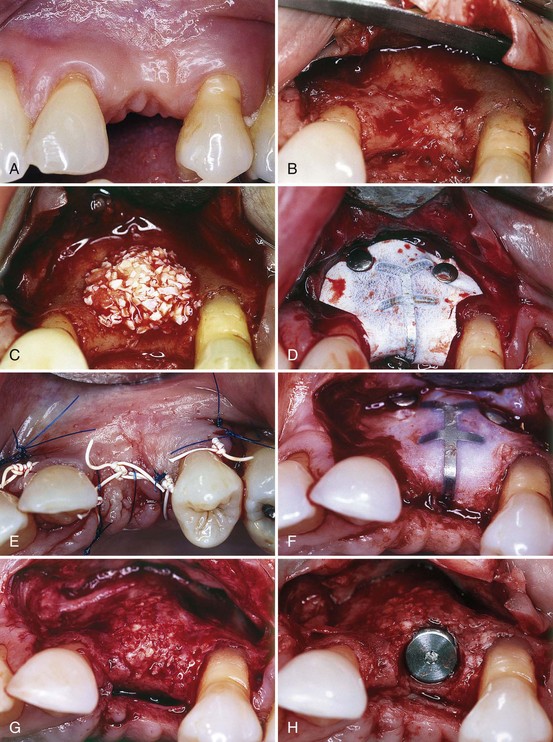

Patients are frequently seen after tooth loss and alveolar ridge resorption have occurred (see Chapter 72). to provide for adequate anatomic dimensions for the construction of an esthetic pontic (see Chapter 66) or the placement of dental implants (see Chapter 71), alveolar ridge reconstruction is undertaken. In the case of esthetic pontic construction, small defects may be treated with soft tissue ridge augmentation (Figure 65-13). For larger defects and in those sites receiving dental implants, hard tissue modalities are used (Figure 65-14).

Figure 65-13 A, Loss of the maxillary left central incisor has resulted in an unesthetic alveolar ridge defect. B to E, An incision is made at ridge crest, a pouch is created, and a soft tissue graft harvested from the palate is placed into the pouch. F to H, A removable appliance with an ovate pontic is placed in light contact with the grafted site. Swelling around the pontic apex results in a tissue concavity from which the more natural-appearing final restoration emerges.

Figure 65-14 Postextraction ridge defect is grafted with a combination of autogenous and deproteinized bovine bone and contained by nonresorbable barrier membrane. After 8 months, the site is reopened and the membrane removed. A comparison of B and G shows significant reconstitution of hard tissue, in this case used for the installation of a dental implant. A, Edentulous ridge before surgery. B, Flap reflection to visualize defect. C, Graft material placed over resorbed ridge. D, Nonresorbable titanium-reinforced membrane placed over graft material. E, Graft site sutured. F, Surgical site reopened 8 months after surgery. G, New bone over ridge. H, Implant placed into augmented ridge.

Conclusion

As described in this and other sections of this textbook, the therapeutic goals of patient comfort, function, esthetics, predictability, longevity, and ease of restorative and maintenance care are attainable only by a carefully constructed interdisciplinary approach, with accurate diagnosis and comprehensive treatment planning serving as cornerstones. The complex interaction between periodontal therapy and successful restorative dentistry only serves to underscore this premise.

1 Abrams H, Kopczyk RA, Kaplan AL. Incidence of anterior ridge deformities in partially edentulous patients. J Prosthet Dent. 1987;57:191.

2 Amler MH, Johnson PL, Salman I. Histological and histochemical investigation of human alveolar socket healing in undisturbed extraction wounds. J Am Dent Assoc. 1960;61:32.

3 Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on caries and periodontal disease in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:133.

4 Axelsson P, Lindhe J. The significance of maintenance care in the treatment of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1981;8:281.

5 Badersten A, Nilvens R, Egelberg J. Effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy. II. Severely advanced periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:63.

6 Brown SI. The effect of orthodontic therapy on certain types of periodontal defects. I. Clinical findings. J Periodontol. 1973;44:742.

7 Claffey N, Egelberg J. Clinical indicators of probing attachment loss following initial periodontal treatment in advanced periodontitis patients. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:690.

8 Ericsson I, Lindhe J. The effect of longstanding jiggling on experimental marginal periodontitis in the beagle dog. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9:497.

9 Folio J, Rams TE, Keyes PH. Orthodontic therapy in patients with juvenile periodontitis: clinical and microbiological effects. Am J Orthodont. 1985;87:421.

10 Gargiulo AW. Dimensions and relations of the dentogingival junction in humans. J Periodontol. 1961;32:261.

11 Garret S. Periodontal regeneration around natural teeth. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:621.

12 Herrero F, Scott JB, Maropis PS, Yukna RA. Clinical comparison of desired versus actual amount of surgical crown lengthening. J Periodontol. 1995;66:568.

13 Highfield JE, Powell RN. Effects of removal of posterior overhanging metallic margins of restoration upon the periodontal tissues. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:169.

14 Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B. A long-term survey of tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1978;5:225.

15 Iasella JM, Greenwell H, Miller RL, et al. Ridge preservation with freeze-dried bone allograft and a collagen membrane compared to extraction alone for implant site development: a clinical and histologic study in humans. J Periodontol. 2003;74:990.

16 Ingber JS. Forced eruption. Part I. A method of treating isolated one and two wall infrabony osseous defects: rationale and case report. J Periodontol. 1974;45:199.

17 Ingber JS. Forced eruption. Part II. A method of treating non-restorable teeth: periodontal and restorative considerations. J Periodontol. 1976;47:203.

18 Jeffcoat MK, Howell TH. Alveolar bone destruction due to overhanging amalgam in periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1980;51:599.

19 Kois JC. The gingiva is red around my crowns.”. Dent Economics. April 1993:100.

20 Kois JC. The restorative-periodontal interface: biological parameters. Periodontol 2000. 1996;11:29.

21 Kois JC. Clinical techniques in prosthodontics: relationship of the periodontium to impression procedures. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2000;21:684.

22 Kokich VG. Esthetics: the orthodontic-periodontic restorative connection. Semin Orthodont. 1996;2:21.

23 Kramer JM, Nevins M. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 1981;1:4. (editorial)

24 Lekovic V, Camargo PM, Klokkevold PR, et al. Alterations of the position of the marginal soft tissue following periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:525.

25 Lekovic V, Kenney EB, Weinlaender M, et al. A bone regenerative approach to alveolar ridge maintenance following tooth extraction: report of 10 cases. J Periodontol. 1997;68:563.

26 Lindhe J, Nyman S. Alterations of the position of the marginal soft tissue following periodontal surgery. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:525.

27 Lindhe J, Westfelt E, Nyman S, et al. Healing following surgical/non-surgical treatment of periodontal disease: a clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1982;9:115.

28 Listgarten MA, Lindhe J, Hellden L. Effect of tetracycline and/or scaling on human periodontal disease: clinical, micro-biological and histological observations. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:246.

29 Lövdal A, Arno A, Schei O, Waerhaug J. Combined effect of subgingival scaling and controlled oral hygiene on the incidence of gingivitis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1961;19:537.

30 Machtei E, Zubrey YI, Ben Yahuda A, Soskolne W. Proximal bone loss adjacent to periodontally “hopeless” teeth with and without extraction. J Periodontol. 1989;60:512.

31 Melnick PR, Camargo PM. Preservation of alveolar ridge dimensions and interproximal papillae through periodontal procedures: long-term results. Contemp Esthet Restor Pract. November 2004:2.

32 Minsk L. Clinical techniques in periodontics: esthetic crown lengthening. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2001;22:562.

33 Nedic M. Preservation of alveolar bone in extraction sockets using bioabsorbable membranes. J Periodontol. 1998;69:1044.

34 Palcanis KG. Surgical pocket therapy. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:589.

35 Parma-Benfenati S, Fugazzotto PA, Ruben MP. The effect of restorative margins on the postsurgical development and nature of the periodontium. Part I. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 1985;6:31.

36 Polson AM, Reed BE. Long-term effects of orthodontic treatment on crestal bone levels. J Periodontol. 1984;55:28.

37 Polson AM, Caton J, Polson A, et al. Periodontal response to tooth movement into intrabony defects. J Periodontol. 1984;55:197.

38 Pontoriero R, Carnevale G. Surgical crown lengthening: a 12-month clinical wound healing study. J Periodontol. 2001;72:841.

39 Rosenberg ES, Cho SC, Garber DA. Crown lengthening revisited. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1999;20:527.

40 Sato S, Ujiie H, Ito K. Spontaneous correction of pathologic tooth migration and reduced infrabony pockets following nonsurgical periodontal therapy: a case report. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 2004;24:456.

41 Smukler H, Chaibi M. Periodontal and dental considerations in clinical crown extension: a rational basis for treatment. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 1997;17:465.

42 Stambaugh RV, Dragoo M, Smith DM, Carasali L. The limits of subgingival scaling. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 1981;1:31.

43 Studer S, Zellweger U, Schärer P. The aesthetic guidelines of the mucogingival complex for fixed prosthodontics. Pract Periodontics Aesthetic Dent. 1996;4:333.

44 Tagge DL, O’Leary TJ, El-Kafrawy AH. The clinical and histological response of periodontal pockets to root planing and oral hygiene. J Periodontol. 1975;46:527.

45 Takei HH, Azzi RR, Han TJ. Preparation of the periodontium for restorative dentistry. In Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA, editors: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 9, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

46 Waerhaug J. The furcation problem: etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, therapy and prognosis. J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:73.

47 Wennström JL. Mucogingival therapy. In Proceedings of the World Workshop on Periodontics. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:671.