Health and Wellness

• List the two general Healthy People 2020 public health goals for Americans.

• Discuss the definition of health.

• Discuss the health belief, health promotion, basic human needs, and holistic health models to understand the relationship between the patient’s attitudes toward health and health practices.

• Describe variables influencing health beliefs and practices.

• Describe health promotion, wellness, and illness prevention activities.

• Discuss the three levels of preventive care.

• Describe four types of risk factors.

• Discuss risk factor modification and changing health behaviors.

• Describe variables influencing illness behavior.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

In the past most individuals and societies viewed good health, or wellness, as the opposite or absence of disease. This simple attitude ignores states of health between disease and good health. Health is a multidimensional concept and is viewed from a broader perspective. An assessment of the patient’s state of health is an important aspect of nursing.

Models of health offer a perspective to understand the relationships between the concepts of health, wellness, and illness. Nurses are in a unique position to help patients achieve and maintain optimal levels of health. They need to understand the challenges of today’s health care system and embrace the opportunities to promote health and wellness and prevent illness. In an era of cost containment and advanced technology, nurses are a vital link to the improved health of individuals and society. They identify actual and potential risk factors that predispose a person or a group to illness. In addition, the nurse uses risk factor modification strategies to promote health and wellness and prevent illness.

Different attitudes cause people to react in different ways to illness or the illness of a family member. Medical sociologists call this reaction illness behavior. Nurses who understand how patients react to illness can minimize its effects and help patients and their families maintain or return to the highest level of functioning.

Healthy People Documents

Healthy People provides science-based, 10-year national objectives for promoting health and preventing disease. In 1979 an influential document, Healthy People: the Surgeon General’s Report on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention, was published; it introduced a goal for improving the health of Americans by 1990. The report outlined priority objectives for preventive services, health protection, and health promotion that addressed improvements in health status, risk reduction, public and professional awareness of prevention, health services and protective measures, and surveillance and evaluation. The report served as a framework for the 1990s as the United States increased the focus on health promotion and disease prevention instead of illness care. The strategy announced by the Secretary of Health and Human Services required a cooperative effort by government, voluntary and professional organizations, businesses, and individuals. Widely cited by popular media, in professional journals, and at health conferences, it has inspired health promotion programs throughout the country.

Healthy People 2000: National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Objectives, published in 1990, identified health improvement goals and objectives to be reached by the year 2000 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS, Public Health Service], 1990). Healthy People 2010, published in 2000, served as a road map for improving the health of all people in the United States for the first decade of the twenty-first century (USDHHS, 2000). This edition emphasized the link between individual health and community health and the premise that the health of communities determines the overall health status of the nation. Healthy People 2020 was approved in December 2010. Healthy People 2020 promotes a society in which all people live long, healthy lives. There are four overarching goals: (1) attain high-quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death; (2) achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups; (3) create social and physical environments that promote good health for all; and (4) promote quality of life, healthy development, and healthy behaviors across all life stages (USDHHS, 2011).

Definition of Health

Defining health is difficult. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as a “state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (WHO, 1947). Many other aspects of health need to be considered. Health is a state of being that people define in relation to their own values, personality, and lifestyle. Each person has a personal concept of health. Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons (2011) define health as the actualization of inherent and acquired human potential through goal-directed behavior, competent self-care, and satisfying relationships with others while adjustments are made as needed to maintain structural integrity and harmony with the environment.

Individuals’ views of health vary among different age-groups, genders, races, and cultures (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011). Pender (1996) explains that “all people free of disease are not equally healthy.” Views of health have broadened to include mental, social, and spiritual well-being and a focus on health at the family and community levels (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2006).

To help patients identify and reach health goals, nurses discover and use information about their concepts of health. Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons (2011) suggest that for many people conditions of life rather than pathological states define health. Life conditions can have positive or negative effects on health long before an illness is evident (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011). Life conditions include socioeconomic variables such as environment, diet, and lifestyle practices or choices and many other physiological and psychological variables.

Health and illness are defined according to individual perception. Health often includes conditions previously considered to be illness. For example, a person with epilepsy who has learned to control seizures with medication and who functions at home and work may no longer consider himself or herself ill. Nurses need to consider the total person and the environment in which the person lives to individualize nursing care and enhance meaningfulness of the patient’s future health status.

Models of Health and Illness

A model is a theoretical way of understanding a concept or idea. Models represent different ways of approaching complex issues. Because health and illness are complex concepts, models are used to understand the relationships between these concepts and the patient’s attitudes toward health and health behaviors.

Health beliefs are a person’s ideas, convictions, and attitudes about health and illness. They may be based on factual information or misinformation, common sense or myths, or reality or false expectations. Because health beliefs usually influence health behavior, they can positively or negatively affect a patient’s level of health. Positive health behaviors are activities related to maintaining, attaining, or regaining good health and preventing illness. Common positive health behaviors include immunizations, proper sleep patterns, adequate exercise, stress management, and nutrition. Negative health behaviors include practices actually or potentially harmful to health such as smoking, drug or alcohol abuse, poor diet, and refusal to take necessary medications.

Nurses developed the following health models to understand patients’ attitudes and values about health and illness and to provide effective health care. These nursing models allow you to understand and predict patients’ health behavior, including how they use health services and adhere to recommended therapy.

Health Belief Model

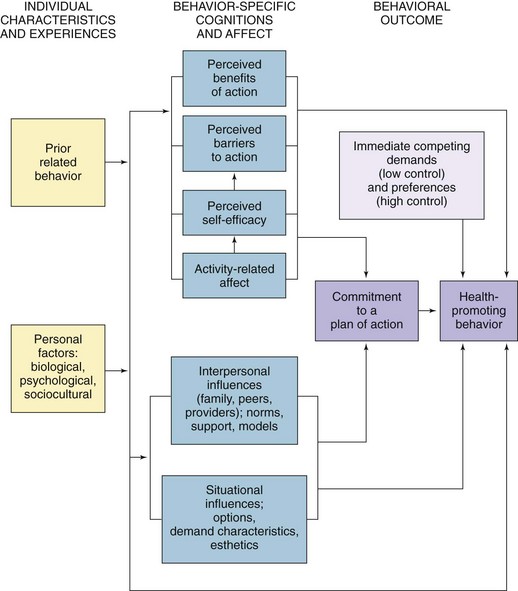

Rosenstoch’s (1974) and Becker and Maiman’s (1975) health belief model (Fig. 6-1) addresses the relationship between a person’s beliefs and behaviors. The health belief model helps you understand factors influencing patients’ perceptions, beliefs, and behavior to plan care that will most effectively assist patients in maintaining or restoring health and preventing illness (Box 6-1).

FIG. 6-1 Health belief model. (Data from Becker M, Maiman L: Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations, Med Care 13[1]:10, 1975.)

The first component of this model involves an individual’s perception of susceptibility to an illness. For example, a patient needs to recognize the familial link for coronary artery disease. After this link is recognized, particularly when one parent and two siblings have died in their fourth decade from myocardial infarction, the patient may perceive the personal risk of heart disease.

The second component is an individual’s perception of the seriousness of the illness. This perception is influenced and modified by demographic and sociopsychological variables, perceived threats of the illness, and cues to action (e.g., mass media campaigns and advice from family, friends, and medical professionals). For example, a patient may not perceive his heart disease to be serious, which may affect the way he takes care of himself.

The third component—the likelihood that a person will take preventive action—results from a person’s perception of the benefits of and barriers to taking action. Preventive actions include lifestyle changes, increased adherence to medical therapies, or a search for medical advice or treatment. A patient’s perception of susceptibility to disease and his or her perception of the seriousness of an illness help to determine the likelihood that the patient will or will not partake in healthy behaviors.

Health Promotion Model

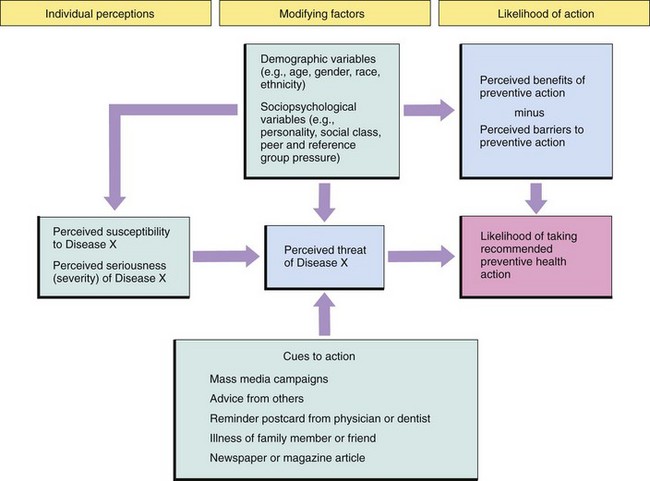

The health promotion model (HPM) proposed by Pender (1982; revised, 1996) was designed to be a “complementary counterpart to models of health protection” (Fig. 6-2). It defines health as a positive, dynamic state, not merely the absence of disease (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011). Health promotion is directed at increasing a patient’s level of well-being. The HPM describes the multidimensional nature of persons as they interact within their environment to pursue health (Pender, 1996; Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011). The model focuses on the following three areas: (1) individual characteristics and experiences, (2) behavior-specific knowledge and affect, and (3) behavioral outcomes. The HPM notes that each person has unique personal characteristics and experiences that affect subsequent actions. The set of variables for behavioral-specific knowledge and affect have important motivational significance. These variables can be modified through nursing actions. Health-promoting behavior is the desired behavioral outcome and is the end point in the HPM. Health-promoting behaviors result in improved health, enhanced functional ability, and better quality of life at all stages of development (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011) (Box 6-2).

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

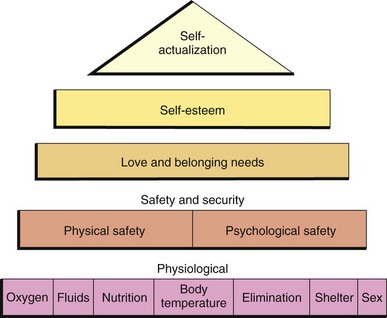

Basic human needs are elements that are necessary for human survival and health (e.g., food, water, safety, and love). Although each person has other unique needs, all people share the basic human needs, and the extent to which basic needs are met is a major factor in determining a person’s level of health.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a model that nurses use to understand the interrelationships of basic human needs (Fig. 6-3). According to this model, certain human needs are more basic than others (i.e., some needs must be met before other needs [e.g., fulfilling the physiological needs before the needs of love and belonging]). Self-actualization is the highest expression of one’s individual potential and allows for continual discovery of self. Maslow’s model takes into account individual experiences, always unique to the individual (Ebersole et al., 2008).

FIG. 6-3 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. (Redrawn from Maslow AH: Motivation and personality, ed 3, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 1970, Prentice Hall.)

The hierarchy of needs model provides a basis for nurses to care for patients of all ages in all health settings. However, when applying the model, the focus of care is on the patient’s needs rather than on strict adherence to the hierarchy. It is unrealistic to always expect a patient’s basic needs to occur in the fixed hierarchical order. In all cases an emergent physiological need takes precedence over a higher-level need. In other situations a psychological or physical safety need takes priority. For example, in a house fire fear of injury and death takes priority over self-esteem issues. Although it would seem that a patient who has just had surgery might have the strongest need for pain control in the psychosocial area, if the patient just had a mastectomy, her main need may be in the areas of love, belonging, and self-esteem. It is important not to assume the patient’s needs just because other patients reacted in a certain way. Maslow’s hierarchy can be very useful when applied to each patient individually. To provide the most effective care, you need to understand the relationships of different needs and the factors that determine the priorities for each patient.

Holistic Health Models

Health care has begun to take a more holistic view of health by considering emotional and spiritual well-being and other dimensions of an individual as important aspects of physical wellness. The holistic health model of nursing attempts to create conditions that promote optimal health. In this model, nurses using the nursing process consider patients to be the ultimate experts concerning their own health and respect patients’ subjective experience as relevant in maintaining health or assisting in healing. In the holistic health model patients are involved in their healing process, thereby assuming some responsibility for health maintenance (Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

Nurses using the holistic nursing model recognize the natural healing abilities of the body and incorporate complementary and alternative interventions such as music therapy, reminiscence, relaxation therapy, therapeutic touch, and guided imagery because they are effective, economical, noninvasive, nonpharmacological complements to traditional medical care (see Chapter 32). These holistic strategies, which can be used in all stages of health and illness, are integral in the expanding role of nursing.

Nurses use holistic therapies either alone or in conjunction with conventional medicine. For example, they use reminiscence in the geriatric population to help relieve anxiety for a patient dealing with memory loss or for a cancer patient dealing with the difficult side effects of chemotherapy. Music therapy in the operating room creates a soothing environment. Relaxation therapy is frequently useful to distract a patient during a painful procedure such as a dressing change. Breathing exercises are commonly taught to help patients deal with the pain associated with labor and delivery.

Variables Influencing Health and Health Beliefs and Practices

Many variables influence a patient’s health beliefs and practices. Internal and external variables influence how a person thinks and acts. As previously stated, health beliefs usually influence health behavior or health practices and likewise positively or negatively affect a patient’s level of health. Therefore understanding the effects of these variables allows you to plan and deliver individualized care.

Internal Variables

Internal variables include a person’s developmental stage, intellectual background, perception of functioning, and emotional and spiritual factors.

Developmental Stage

A person’s thought and behavior patterns change throughout life. The nurse considers the patient’s level of growth and development when using his or her health beliefs and practices as a basis for planning care. The study of development involves finding patterns or general principles that apply to most people most of the time (Murray et al., 2008). The concept of illness for a child, adolescent, or adult depends on the individual’s developmental stage. Fear and anxiety are common among ill children, especially if thoughts about illness, hospitalization, or procedures are based on lack of information or lack of clarity of information. Emotional development may also influence personal beliefs about health-related matters. For example, you use different techniques for teaching about contraception to an adolescent than you use for an adult. Knowledge of the stages of growth and development helps predict the patient’s response to the present illness or the threat of future illness. Adapt the planning of nursing care to these expectations and to the patient’s abilities to participate in self-care.

Intellectual Background

A person’s beliefs about health are shaped in part by the person’s knowledge, lack of knowledge, or incorrect information about body functions and illnesses, educational background, and past experiences. These variables influence how a patient thinks about health. In addition, cognitive abilities shape the way a person thinks, including the ability to understand factors involved in illness and apply knowledge of health and illness to personal health practices. Cognitive abilities also relate to a person’s developmental stage. A nurse considers intellectual background so these variables can be incorporated into nursing care (Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

Perception of Functioning

The way people perceive their physical functioning affects health beliefs and practices. When you assess a patient’s level of health, gather subjective data about the way the patient perceives physical functioning such as level of fatigue, shortness of breath, or pain. Then obtain objective data about actual functioning such as blood pressure, height measurements, and lung sound assessment. This information allows you to more successfully plan and implement individualized care.

Emotional Factors

The patient’s degree of stress, depression, or fear can influence health beliefs and practices. The manner in which a person handles stress throughout each phase of life influences the way he or she reacts to illness. A person who generally is very calm may have little emotional response during illness, whereas an individual unable to cope emotionally with the threat of illness may either overreact to it and assume that it is life threatening or deny the presence of symptoms and not take therapeutic action (see Chapter 37).

Spiritual Factors

Spirituality is reflected in how a person lives his or her life, including the values and beliefs exercised, the relationships established with family and friends, and the ability to find hope and meaning in life. Spirituality serves as an integrating theme in people’s lives (see Chapter 35). Religious practices are one way that people exercise spirituality. Some religions restrict the use of certain forms of medical treatment. You need to understand patients’ spiritual dimensions to involve patients effectively in nursing care.

External Variables

External variables influencing a person’s health beliefs and practices include family practices, socioeconomic factors, and cultural background.

Family Practices

The way that patients’ families use health care services generally affects their health practices. Their perceptions of the seriousness of diseases and their history of preventive care behaviors (or lack of them) influence how patients think about health. For example, if a young woman’s mother never had annual gynecological examinations or Papanicolaou (Pap) smears, it is unlikely that the daughter will have annual Pap smears.

Socioeconomic Factors

Social and psychosocial factors increase the risk for illness and influence the way that a person defines and reacts to illness. Psychosocial variables include the stability of the person’s marital or intimate relationship, lifestyle habits, and occupational environment. A person generally seeks approval and support from social networks (neighbors, peers, and co-workers), and this desire for approval and support affects health beliefs and practices.

Social variables partly determine how the health care system provides medical care. The organization of the health care system determines how patients can obtain care, the treatment method, the economic cost to the patient, and potential reimbursement to the health care agency or patient.

Like social variables, economic variables often affect a patient’s level of health by increasing the risk for disease and influencing how or at what point the patient enters the health care system. A person’s compliance with a treatment designed to maintain or improve health is also affected by economic status. A person who has high utility bills, a large family, and a low income tends to give a higher priority to food and shelter than to costly drugs or treatment or expensive foods for special diets. Some patients decide to take medications every other day rather than every day as prescribed to save money, which greatly affects the effectiveness of the medications.

Cultural Background

Cultural background influences beliefs, values, and customs. It influences the approach to the health care system, personal health practices, and the nurse-patient relationship. Cultural background also influences an individual’s beliefs about causes of illness and remedies or practices to restore health (Box 6-3). If you are not aware of your own cultural patterns of behavior and language, you will have difficulty recognizing and understanding your patient’s behaviors and beliefs. You will also probably have difficulty interacting with patients. As with family and socioeconomic variables, you need to incorporate cultural variables into a patient’s care plan (see Chapter 9).

Health Promotion, Wellness, and Illness Prevention

Health care has become increasingly focused on health promotion, wellness, and illness prevention. The rapid rise of health care costs has motivated people to seek ways of decreasing the incidence and minimizing the results of illness or disability.

The concepts of health promotion, wellness, and illness prevention are closely related and in practice overlap to some extent. All are focused on the future; the difference among them involves motivations and goals. Health promotion activities such as routine exercise and good nutrition help patients maintain or enhance their present levels of health. They motivate people to act positively to reach more stable levels of health. Wellness education teaches people how to care for themselves in a healthy way and includes topics such as physical awareness, stress management, and self-responsibility. Wellness strategies help people achieve new understanding and control of their lives. Illness prevention activities such as immunization programs protect patients from actual or potential threats to health. They motivate people to avoid declines in health or functional levels.

Nurses emphasize health promotion activities, wellness-enhancing strategies, and illness prevention activities as important forms of health care because they assist patients in maintaining and improving health. The goal of a total health program is to improve a patient’s level of well-being in all dimensions, not just physical health. Total health programs are based on the belief that many factors can affect a person’s level of health.

Examples of the health topics and objectives as defined by Healthy People 2020 include physical activity, adolescent health, tobacco use, substance abuse, sexually transmitted diseases, mental health and mental disorders, injury and violence prevention, environmental health, immunization and infectious disease, and access to health care (USDHHS, 2011). A complete list of topics and objectives is available on the Healthy People website (www.healthypeople.gov). These objectives and topics show the importance of health promotion and illness prevention and encourage all to participate in the improvement of health.

Individual practices such as poor eating habits and little or no exercise influence health. Physical stressors such as a poor living environment, exposure to air pollutants, and an unsafe environment also affect health. Hereditary and psychological stressors such as emotional, intellectual, social, developmental, and spiritual factors influence one’s level of health. Total health programs are directed at individuals’ changing their lifestyles by developing habits that improve their level of health.

Other programs are aimed at specific health care problems. For example, support groups help people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Exercise programs encourage participants to exercise regularly to reduce their risk of cardiac disease. Stress-reduction programs teach participants to cope with stressors and reduce their risks for multiple illnesses such as infections, gastrointestinal disease, and cardiac disease.

Some health promotion, wellness education, and illness prevention programs are operated by health care agencies; others are operated independently. Many businesses have on-site health promotion activities for employees. Likewise, colleges and community centers offer health promotion and illness prevention programs. Some nurses actively participate in these programs, providing direct care, and others act as consultants or refer patients to these programs. The goal of these activities is to improve a patient’s level of health through preventive health services, environmental protection, and health education.

Health care professionals who work in the field of health promotion use proactive attempts to prevent illness or disease. Health promotion activities are passive or active. With passive strategies of health promotion, individuals gain from the activities of others without acting themselves. The fluoridation of municipal drinking water and the fortification of homogenized milk with vitamin D are examples of passive health promotion strategies. With active strategies of health promotion, individuals are motivated to adopt specific health programs. Weight-reduction and smoking-cessation programs require patients to be actively involved in measures to improve their present and future levels of wellness while decreasing the risk of disease.

Health promotion is a process of helping people improve their health to reach an optimal state of physical, mental, and social well-being (WHO, 2009). An individual takes responsibility for health and wellness by making appropriate lifestyle choices. Lifestyle choices are important because they affect a person’s quality of life and well-being. Making positive lifestyle choices and avoiding negative lifestyle choices also plays a role in preventing illness. In addition to improving quality of life, preventing illness has an economic impact because it decreases health care costs.

Levels of Preventive Care

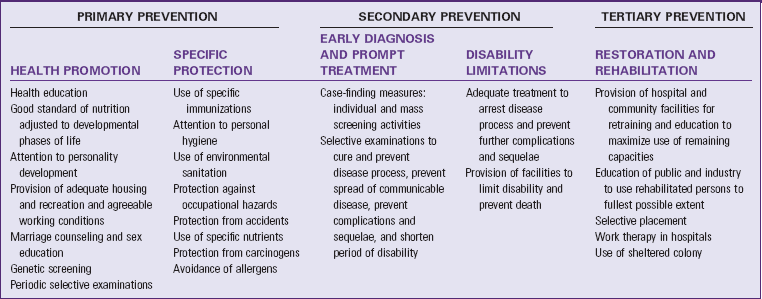

Nursing care oriented to health promotion, wellness, and illness prevention is described in terms of health activities on primary, secondary, and tertiary levels (Table 6-1).

TABLE 6-1

Data from Leavell H, Clark AE: Preventive medicine for the doctors in his community, ed 3, New York, 1965, McGraw-Hill; and modified from Edelman CL, Mandle CL: Health promotion throughout the life span, ed 7, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention is true prevention; it precedes disease or dysfunction and is applied to patients considered physically and emotionally healthy. Primary prevention aimed at health promotion includes health education programs, immunizations, and physical and nutritional fitness activities. Primary prevention includes all health promotion efforts and wellness education activities that focus on maintaining or improving the general health of individuals, families, and communities (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Primary prevention includes specific protection such as immunization for influenza and hearing protection in occupational settings.

Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention focuses on individuals who are experiencing health problems or illnesses and are at risk for developing complications or worsening conditions. Activities are directed at diagnosis and prompt intervention, thereby reducing severity and enabling the patient to return to a normal level of health as early as possible (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). A large portion of nursing care related to secondary prevention is delivered in homes, hospitals, or skilled nursing facilities. It includes screening techniques and treating early stages of disease to limit disability by averting or delaying the consequences of advanced disease. Screening activities also become a key opportunity for health teaching as a primary prevention intervention (Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

Tertiary Prevention

Tertiary prevention occurs when a defect or disability is permanent and irreversible. It involves minimizing the effects of long-term disease or disability by interventions directed at preventing complications and deterioration (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Activities are directed at rehabilitation rather than diagnosis and treatment. Care at this level helps patients achieve as high a level of functioning as possible, despite the limitations caused by illness or impairment. This level of care is called preventive care because it involves preventing further disability or reduced functioning.

Risk Factors

A risk factor is any situation, habit, social or environmental condition, physiological or psychological condition, developmental or intellectual condition, spiritual condition, or other variable that increases the vulnerability of an individual or group to an illness or accident. Risk factors, behavior, risk factor modification, and behavior modification are integral components of health promotion, wellness, and illness prevention activities. Nurses in all areas of practice often have opportunities to help patients adopt activities to promote health and decrease risks of illness.

The presence of risk factors does not mean that a disease will develop, but risk factors increase the chances that the individual will experience a particular disease or dysfunction. Nurses and other health care professionals are concerned with risk factors, sometimes called health hazards, for several reasons. Risk factors play a major role in how a nurse identifies a patient’s health status. They can also influence health beliefs and practices if a person is aware of their presence. Risk factors are often placed in the following interrelated categories: genetic and physiological factors, age, physical environment, and lifestyle.

Genetic and Physiological Factors

Physiological risk factors involve the physical functioning of the body. Certain physical conditions such as being pregnant or overweight place increased stress on physiological systems (e.g., the circulatory system), increasing susceptibility to illness. Heredity, or genetic predisposition to specific illness, is a major physical risk factor. For example, a person with a family history of diabetes mellitus is at risk for developing the disease later in life. Other documented genetic risk factors include family histories of cancer, heart disease, kidney disease, or mental illness.

Age

Age affects a person’s susceptibility to certain illnesses. For example, premature infants and neonates are more susceptible to infections. As a person ages, the risk of heart disease and many types of cancers increases. Age risk factors are often closely associated with other risk factors such as family history and personal habits. Nurses need to educate their patients about the importance of regularly scheduled checkups for their age-group. Various professional organizations and federal agencies develop and update recommendations for health screenings, immunizations, and counseling. Access to scientific evidence, recommendations for clinical prevention services, and information on how to incorporate recommended preventive services into practice can be found at www.ahrq.gov/clinic/prevenix.htm.

Environment

Where we live and the condition of that area (its air, water, and soil) determine how we live, what we eat, the disease agents to which we are exposed, our state of health, and our ability to adapt (Murray et al., 2008). The physical environment in which a person works or lives can increase the likelihood that certain illnesses will occur. For example, some kinds of cancer and other diseases are more likely to develop when industrial workers are exposed to certain chemicals or when people live near toxic waste disposal sites. Nursing assessments extend from the individual to the family and the community in which they live (Murray et al., 2008).

Lifestyle

Many activities, habits, and practices involve risk factors. Lifestyle practices and behaviors often have positive or negative effects on health. Lifestyle choices contribute to seven of the ten leading causes of death (Table 6-2). Practices with potential negative effects are risk factors. Some habits are risk factors for specific diseases. For example, excessive sunbathing increases the risk of skin cancer; smoking increases the risk of lung diseases, including cancer; and a poor diet and being overweight increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Because of lifestyle choices, there is an increased emphasis on preventive care. Lifestyle choices lead to health problems that cause a huge impact on the economics of the health care system. Therefore it is important to understand the effect of lifestyle behaviors on health status. Nurses educate their patients and the public on wellness-promoting lifestyle behaviors.

TABLE 6-2

Causes of Death in the United States in 2007 and Contributing Lifestyle Choices

| LEADING CAUSES OF DEATH | NUMBER (%)* | LIFESTYLE CHOICES |

| Heart disease | 616,067 (25.4) | Physical inactivity, poor nutrition, use of tobacco |

| Cancer | 562,875 (23.2) | Use of tobacco, poor nutrition, excess sun exposure, no use of preventive screenings |

| Stroke (cerebrovascular diseases) | 135,952 (5.6) | Use of tobacco, poor nutrition, physical inactivity |

| Chronic lower respiratory diseases | 127,924 (5.3) | Use of tobacco |

| Accidents (unintentional injuries) | 123,706 (5.1) | Use of alcohol and drugs, no use of seat belt or motorcycle helmet |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 74,632 (3.1) | |

| Diabetes | 71,382 (2.9) | Obesity, poor nutrition |

| Influenza and pneumonia | 52,717 (2.2) | Use of tobacco, lack of immunizations |

| Nephritis, nephrotic syndrome, nephrosis | 46,448 (1.9) | |

| Septicemia | 34,828 (1.4) |

*Data from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Deaths and mortality, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/deaths.htm. Accessed June 30, 2009.

Stress is a lifestyle risk factor if it is severe or prolonged or if the person is unable to cope with life events adequately. Stress threatens both mental health (emotional stress) and physical well-being (physiological stress). Both play a part in the development of an illness and affect the ability to adapt to potential changes associated with the illness and survive a life-threatening illness. Stress also interferes with health promotion activities and the ability to implement needed lifestyle modifications. Some emotional stressors result from life events such as divorce, pregnancy, death of a spouse or family member, and financial instabilities. For example, job-related stressors overtax a person’s cognitive skills and decision-making ability, leading to “mental overload” or “burnout” (see Chapter 37). Stress also threatens physical well-being and is associated with illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, and gastrointestinal disorders (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011). Always review life stressors as part of a comprehensive risk factor analysis.

The goal of risk factor identification is to help patients visualize the areas in their life that can be modified, controlled, or even eliminated to promote wellness and prevent illness. A variety of available health risk appraisal forms can be used to estimate a person’s specific health threats based on the presence of various risk factors (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Implementation of a health risk appraisal tool needs to be linked with educational programs and other community resources if it is to result in necessary lifestyle changes and risk reduction (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011).

Risk-Factor Modification and Changing Health Behaviors

Identifying risk factors is the first step in health promotion, wellness education, and illness prevention. Discuss health hazards with the patient following a comprehensive nursing assessment, then help the patient decide if he or she wants to maintain or improve his or her health status by taking risk-reduction actions (Edelman and Mandle, 2010). Risk-factor modification, health promotion or illness prevention activities, or any program that attempts to change unhealthy lifestyle behaviors is a wellness strategy. Emphasize wellness strategies that teach patients to care for themselves in a healthier way because they have the ability to increase the quality of life and decrease the potential high costs of unmanaged health problems.

Some attempts to change are aimed at the cessation of a health-damaging behavior (e.g., tobacco use or alcohol misuse) or the adoption of a healthy behavior (e.g., healthy diet or exercise) (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011). It is difficult to change health behavior, especially when the behavior is ingrained in a person’s lifestyle patterns. The importance of nurses using an HPM to identify risky behaviors and implement the change process cannot be overemphasized because it is the nurse who spends the greatest amount of time in direct contact with patients. In addition, leading causes of death continue to relate to health behaviors that require a change, and nurses are able to motivate and facilitate important health behavior change when working with individuals, families, and communities (Edelman and Mandle, 2010).

Understanding the process of changing behaviors will help you support difficult health behavior changes in patients. It is believed that change involves movement through a series of stages. DiClemente and Prochaska (1998) describe the stages of change in the transtheoretical model of change (Table 6-3). These stages range from no intention to change (precontemplation), considering a change within the next 6 months (contemplation), making small changes (preparation), and actively engaging in strategies to change behavior (action) to maintaining a changed behavior (maintenance stage). As individuals attempt a change in behavior, relapse followed by recycling through the stages frequently occurs. When relapse occurs, the person will return to the contemplation or precontemplation stage before attempting the change again. Relapse is a learning process, and the lessons learned from relapse can be applied to the next attempt to change. It is important to understand what happens at the various stages of the change process to time the implementation of interventions (wellness strategies) adequately and provide appropriate care at each stage.

TABLE 6-3

Stages of Health Behavior Change

| STAGE | DEFINITION | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| Precontemplation | Not intending to make changes within the next 6 months | Patient is not interested in information about the behavior and may be defensive when confronted with it. |

| Contemplation | Considering a change within the next 6 months | Ambivalence may be present, but patients will more likely accept information since they are developing more belief in the value of change. |

| Preparation | Making small changes in preparation for a change in the next month | Patient believes that advantages outweigh disadvantages of behavior change; needs assistance in planning for the change. |

| Action | Actively engaged in strategies to change behavior; lasts up to 6 months | Previous habits may prevent taking action relating to new behaviors; identify barriers and facilitators of change. |

| Maintenance stage | Sustained change over time; begins 6 months after action has started and continues indefinitely | Changes need to be integrated into the patient’s lifestyle. |

Data from Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC: Stages of change in the modification of problem behaviors, Prog Behav Modif 28:184, 1992; and Conn VS: A staged-based approach to helping people change health behaviors, Clin Nurs Spec 8(4):187, 1994.

Once an individual identifies a stage of change, the change process facilitates movement through the stages. To be most effective, you choose nursing interventions that match the stage of change (DiClemente and Prochaska, 1998). Most behavior-change programs are designed for (and have a chance of success when) people are ready to take action regarding their health behavior problems. Only a minority of people are actually in this action stage (Prochaska, 1991). Changes are maintained over time only if they are integrated into an individual’s overall lifestyle (Box 6-4). Maintaining healthy lifestyles can prevent hospitalizations and potentially lower the cost of health care.

Illness

Illness is a state in which a person’s physical, emotional, intellectual, social, developmental, or spiritual functioning is diminished or impaired. Cancer is a disease process, but one patient with leukemia who is responding to treatment may continue to function as usual, whereas another patient with breast cancer who is preparing for surgery may be affected in dimensions other than the physical. Therefore illness is not synonymous with disease. Although nurses need to be familiar with different types of diseases and their treatments, they often are concerned more with illness, which may include disease but also includes the effects on functioning and well-being in all dimensions.

Acute and Chronic Illness

Acute and chronic illness are two general classifications of illness used in this chapter. Both acute and chronic illnesses have the potential to be life threatening. An acute illness is usually reversible, has a short duration, and is often severe. The symptoms appear abruptly, are intense, and often subside after a relatively short period. An acute illness may affect functioning in any dimension. A chronic illness persists, usually longer than 6 months, is irreversible, and affects functioning in one or more systems. Patients often fluctuate between maximal functioning and serious health relapses that may be life threatening. A person with a chronic illness is similar to a person with a disability in that both have varying degrees of functional limitations that result from either a pathological process or an injury (Larsen, 2009a). In addition, the social surroundings and physical environment in which the individual lives frequently affect the abilities, motivation, and psychological maintenance of the person with a chronic illness or disability.

Chronic illnesses and disabilities remain a leading health problem in North America for older adults and children. Issues of coping and living with a chronic illness can be complex and overwhelming. Chronic illnesses are related to four modifiable health behaviors: physical inactivity, poor nutrition, use of tobacco, and excessive alcohol consumption (CDC, 2009). A major role for nursing is to provide patient education aimed at helping patients manage their illness or disability. The goal of managing a chronic illness is to reduce the occurrence or improve the tolerance of symptoms. By enhancing wellness, nurses improve the quality of life for patients living with chronic illnesses or disabilities.

Patients with chronic diseases and their families continually adjust and adapt to their illnesses. How an individual perceives an illness influences the type of coping responses. In response to a chronic illness, an individual develops an illness career. The illness career is flexible and changes in response to changes in health, interactions with health professionals, psychological changes related to grief, and stress related to the illness (Larsen, 2009b).

Illness Behavior

People who are ill generally act in a way that medical sociologists call illness behavior. It involves how people monitor their bodies, define and interpret their symptoms, take remedial actions, and use the resources in the health care system (Mechanic, 1995). Personal history, social situations, social norms, and past experiences affect illness behavior (Larsen, 2009b). How people react to illness varies widely; illness behavior displayed in sickness is often used to manage life adversities (Mechanic, 1995). In other words, if people perceive themselves to be ill, illness behaviors become coping mechanisms. For example, illness behavior results in a patient being released from roles, social expectations, or responsibilities. A homemaker views the “flu” as either an added stressor or a temporary release from child care and household responsibilities.

Variables Influencing Illness and Illness Behavior

Internal and external variables influence both health and health behavior and illness and illness behavior. The influences of these variables and the patient’s illness behavior often affect the likelihood of seeking health care, compliance with therapy, and health outcomes. Nurses plan individualized care based on an understanding of these variables and behaviors to help patients cope with their illness at various stages. The goal is to promote optimal functioning in all dimensions throughout an illness.

Internal Variables

Internal variables, such as patient perceptions of symptoms and the nature of the illness, influence patient behavior. If patients believe that the symptoms of their illnesses disrupt their normal routine, they are more likely to seek health care assistance than if they do not perceive the symptoms to be disruptive. Patients are also more likely to seek assistance if they believe the symptoms are serious or life threatening. Persons awakened by crushing chest pains in the middle of the night generally view this symptom as potentially serious and life threatening, and they will probably be motivated to seek assistance. However, such a perception can also have the opposite effect. Individuals may fear serious illness, react by denying it, and not seek medical assistance.

The nature of the illness, either acute or chronic, also affects a patient’s illness behavior. Patients with acute illnesses are likely to seek health care and comply readily with therapy. On the other hand, a patient with a chronic illness in which symptoms are not cured but only partially relieved may not be motivated to comply with the therapy plan. Some patients who are chronically ill become less actively involved in their care, experience greater frustration, and comply less readily with care. Because nurses generally spend more time than other health care professionals with chronically ill patients, they are in the unique position of being able to help these patients overcome problems related to illness behavior. A patient’s coping skills and his or her locus of control are other internal variables that affect the way the patient behaves when ill (see Chapter 37).

External Variables

External variables influencing a patient’s illness behavior include the visibility of symptoms, social group, cultural background, economic variables, accessibility of the health care system, and social support. The visibility of the symptoms of an illness affects body image and illness behavior. A patient with a visible symptom is often more likely to seek assistance than a patient with no visible symptoms.

Patients’ social groups either assist in recognizing the threat of illness or support the denial of potential illness. Families, friends, and co-workers all potentially influence patients’ illness behavior. Patients often react positively to social support while practicing positive health behaviors. A person’s cultural and ethnic background teaches the person how to be healthy, how to recognize illness, and how to be ill. The effects of disease and its interpretation vary according to cultural circumstances. Ethnic differences influence decisions about health care and the use of diagnostic and health care services. Dietary practices among ethnic groups, occupations held by certain cultural groups, and cultural beliefs are other factors that contribute to illness and the distribution of disease (Giger and Davidhizar, 2008).

Economic variables influence the way a patient reacts to illness. Because of economic constraints, some patients delay treatment and in many cases continue to carry out daily activities. Patients’ access to the health care system is closely related to economic factors. The health care system is a socioeconomic system that patients enter, interact within, and exit. For many patients entry into the system is complex or confusing, and some patients seek nonemergency medical care in an emergency department because they do not know how otherwise to obtain health services or do not have access to care. The physical proximity of patients to a health care agency often influences how soon they enter the system after deciding to seek care.

Impact of Illness on the Patient and Family

Illness is never an isolated life event. The patient and family deal with changes resulting from illness and treatment. Each patient responds uniquely to illness, requiring you to individualize nursing interventions. The patient and family commonly experience behavioral and emotional changes and changes in roles, body image and self-concept, and family dynamics.

Behavioral and Emotional Changes

People react differently to illness or the threat of illness. Individual behavioral and emotional reactions depend on the nature of the illness, the patient’s attitude toward it, the reaction of others to it, and the variables of illness behavior.

Short-term, nonlife-threatening illnesses evoke few behavioral changes in the functioning of the patient or family. For example, a father who has a cold lacks the energy and patience to spend time in family activities. He becomes irritable and prefers not to interact with his family. This is a behavioral change, but the change is subtle and does not last long. Some may even consider such a change a normal response to illness.

Severe illness, particularly one that is life threatening, leads to more extensive emotional and behavioral changes such as anxiety, shock, denial, anger, and withdrawal. These are common responses to the stress of illness. You can develop interventions to help the patient and family cope with and adapt to this stress when the stressor itself usually cannot be changed.

Impact on Body Image

Body image is the subjective concept of physical appearance (see Chapter 33). Some illnesses result in changes in physical appearance. Patients’ and families’ reactions differ and usually depend on the type of changes (e.g., loss of a limb or an organ), their adaptive capacity, the rate at which changes takes place, and the support services available.

When a change in body image such as results from a leg amputation occurs, the patient generally adjusts in the following phases: shock, withdrawal, acknowledgment, acceptance, and rehabilitation. Initially the patient is in shock because of the change or impending change. He or she depersonalizes the change and talks about it as though it were happening to someone else. As the patient and family recognize the reality of the change, they become anxious and often withdraw, refusing to discuss it. Withdrawal is an adaptive coping mechanism that helps the patient adjust. As the patient and family acknowledge the change, they move through a period of grieving. At the end of the acknowledgment phase, they accept the loss. During rehabilitation the patient is ready to learn how to adapt to the change in body image through use of prosthesis or changing lifestyles and goals.

Impact on Self-Concept

Self-concept is a mental self-image of strengths and weaknesses in all aspects of personality. Self-concept depends in part on body image and roles but also includes other aspects of psychology and spirituality (see Chapters 33 and 35). The effect of illness on the self-concepts of patients and family members is usually more complex and less readily observed than role changes.

Self-concept is important in relationships with other family members. For example, a patient whose self-concept changes because of illness may no longer meet family expectations, leading to tension or conflict. As a result, family members change their interactions with the patient. In the course of providing care, you observe changes in the patient’s self-concept (or in the self-concepts of family members) and develop a care plan to help him or her adjust to the changes resulting from the illness.

Impact on Family Roles

People have many roles in life such as wage earner, decision maker, professional, child, sibling, or parent. When an illness occurs, parents and children try to adapt to the major changes that result. Role reversal is common (see Chapter 10). If a parent of an adult becomes ill and cannot carry out usual activities, the adult child often assumes many of the parent’s responsibilities and in essence becomes a parent to the parent. Such a reversal of the usual situation can lead to stress, conflicting responsibilities for the adult child, or direct conflict over decision making.

Such a change may be subtle and short term or drastic and long term. An individual and family generally adjust more easily to subtle, short-term changes. In most cases they know that the role change is temporary and will not require a prolonged adjustment. However, long-term changes require an adjustment process similar to the grief process (see Chapter 36). The patient and family often require specific counseling and guidance to help them cope with role changes.

Impact on Family Dynamics

As a result of the effects of illness on the patient and family, family dynamics often change. Family dynamics are the processes by which the family functions, makes decisions, gives support to individual members, and copes with everyday changes and challenges. When a parent in a family becomes ill, family activities and decision making often come to a halt as the other family members wait for the illness to pass, or the family members delay action because they are reluctant to assume the ill person’s roles or responsibilities. Women living with spouses who have chronic illness experience a feeling of detachment from the spouse, a sense of loneliness, and a change in their relationship (Eriksson and Svedlund, 2006). The nurse views the whole family as a patient under stress, planning care to help the family regain the maximal level of functioning and well-being (see Chapter 10).

Key Points

• Health and wellness are not merely the absence of disease and illness.

• A person’s state of health, wellness, or illness depends on individual values, personality, and lifestyle.

• The health belief model considers the relationship between a person’s health beliefs and health behaviors.

• The health promotion model highlights factors that increase individual well-being and self-actualization.

• Maslow’s hierarchy of needs model emphasizes identifying a patient’s individual needs, prioritizing the needs, and encouraging the patient’s individual discovery of self (self-actualization).

• Holistic health models of nursing promote optimal health by incorporating active participation of patients in improving their health state.

• Health beliefs and practices are influenced by internal and external variables and should be considered when planning care.

• Health promotion activities help maintain or enhance health.

• Wellness education teaches patients how to care for themselves.

• Illness prevention activities protect against health threats and thus maintain an optimal level of health.

• Nursing incorporates health promotion activities, wellness education, and illness prevention activities rather than simply treating illness.

• The three levels of preventive care are primary, secondary, and tertiary.

• Risk factors threaten health, influence health practices, and are important considerations in illness prevention activities.

• Improvement in health may involve a change in health behaviors.

• The transtheoretical model of change describes a series of changes through which patients progress for successful behavior change rather than simply assuming that all patients are in an action stage.

• Illness behavior, like health practices, is influenced by many variables and must be considered by the nurse when planning care.

• Illness can have many effects on the patient and family, including changes in behavior and emotions, family roles and dynamics, body image, and self-concept.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

Mrs. Hillman is a 28-year-old divorced woman who is a single parent. She has two children, a 2-year-old boy and a 4-year-old girl. She currently does not have a job. She smokes one pack of cigarettes per day. The father of the children has limited involvement in the care of the children and gives her money when he can. Her mother lives 500 miles away, but her sister lives close by. She occasionally stops by to help with the children. Mrs. Hillman regularly takes the children to the local health clinic for care but she has not seen a health care provider since the delivery of her last child. She is experiencing a persistent cough and fatigue.

1. Identify internal and external variables that are impacting Mrs. Hillman’s ability to care for herself.

2. What primary intervention activities are important for Mrs. Hillman and her family?

3. Using the transtheoretical model of change, which question could you ask Mrs. Hillman to determine how to target smoking cessation?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. The nurse is participating at a health fair at the local mall giving influenza vaccines to senior citizens. What level of prevention is the nurse practicing?

2. A patient experienced a myocardial infarction 4 weeks ago and is currently participating in the daily cardiac rehabilitation sessions at the local fitness center. In what level of prevention is the patient participating?

3. Based on the transtheoretical model of change, what is the most appropriate response to a patient who states: “Me, exercise? I haven’t done that since junior high gym class, and I hated it then!”

1. “That’s fine. Exercise is bad for you anyway.”

2. “OK. I want you to walk 3 miles 4 times a week, and I’ll see you in 1 month.”

3. “I understand. Can you think of one reason why being more active would be helpful for you?”

4. “I’d like you to ride your bike 3 times this week and eat at least four fruits and vegetables every day.”

4. A patient comes to the local health clinic and states: “I’ve noticed how many people are out walking in my neighborhood. Is walking good for you?” What is the best response to help the patient through the stages of change for exercise?

1. “Walking is OK. I really think running is better.”

2. “Yes, walking is great exercise. Do you think you could go for a 5-minute walk next week?”

3. “Yes, I want you to begin walking. Walk for 30 minutes every day and start to eat more fruits and vegetables.”

4. “They probably aren’t walking fast enough or far enough. You need to spend at least 45 minutes if you are going to do any good.”

5. A male patient has been laid off from his construction job and has many unpaid bills. He is going through a divorce from his marriage of 15 years and has been seeing his pastor to help him through this difficult time. He does not have a primary health care provider because he has never really been sick and his parents never took him to the physician when he was a child. Which external variables influence the patient’s health practices? (Select all that apply.)

1. Difficulty paying his bills

2. Seeing his pastor as a means of support

3. Family practice of not routinely seeing a health care provider

6. The nurse is conducting a home visit with an older adult couple. She assesses that the lighting in the home is poor and there are throw rugs throughout the home and a low footstool in the living room. She discusses removing the rugs and footstool and improving the lighting with the couple. The nurse is addressing which level of need according to Maslow?

7. When taking care of patients, the nurse routinely asks them if they take any vitamins or herbal medications, encourages family members to bring in music that the patient likes to help the patient relax, and frequently prays with her patients if that is important to them. The nurse is practicing which model?

8. When illness occurs, different attitudes about it cause people to react in different ways. What do medical sociologists call this reaction to illness?

9. A patient at the community clinic asks the nurse about health promotion activities that she can do because she is concerned about getting diabetes mellitus since her grandfather and father both have the disease. This statement reflects that the patient is in what stage of the health belief model?

1. Perceived threat of the disease

2. Likelihood of taking preventive health action

10. A nurse works in a special care unit for children with severe immunology problems and is caring for a 3-year-old boy from Greece. The boy’s father is with him while his mother and sister are back in Greece. The nurse is having difficulty communicating with the father. What action does the nurse take?

1. Care for the boy as she would any other patient

2. Ask the manager to talk with the father and keep him out of the unit

3. Have another nurse care for the boy because maybe that nurse will do better with the father

4. Search for help with interpretation and understanding of the cultural differences by contacting someone from the local Greek community

11. A patient with a 20-year history of diabetes mellitus had a lower leg amputation. Which statement made by the patient indicates that he is experiencing a problem with body image?

1. “I just don’t have any energy to get out of bed in the morning.”

2. “I’ve been attending church regularly with my wife since I got out of the hospital.”

3. “My wife has taken over paying the bills since I’ve been in the hospital.”

4. “I don’t go out very much because everyone stares at me.”

12. The patient states she joined a fitness club and attends the aerobics class three nights a week. The patient is in what stage of behavioral change?

13. The nurse is developing a health promotion program on healthy eating and exercise for high school students using the health belief model as a framework. Which statement made by a nursing student is related to the individual’s perception of susceptibility to an illness?

1. “I don’t have time to exercise because I have to work after school every night.”

2. “I’m worried about becoming overweight and getting diabetes because my father has diabetes.”

3. “The statistics of how many teenagers are overweight is scary.”

4. “I’ve decided to start a walking club at school for interested students.”

14. The nurse assesses the following risk factors for coronary artery disease (CAD) in a male patient. Which factors are classified as genetic and physiological? (Select all that apply.)

15. Which activity represents secondary prevention?

1. A home health care nurse visits a patient’s home to change a wound dressing.

2. A 50-year-old woman with no history of disease attends the local health fair and has her blood pressure checked.

3. The school health nurse provides a program to the first-year students on healthy eating.

4. The patient attends cardiac rehabilitation sessions weekly.

Answers: 1. 1; 2. 3; 3. 3; 4. 2; 5. 1, 3, 4; 6. 2; 7. 1; 8. 2; 9. 4; 10. 4; 11. 4; 12. 4; 13. 2; 14. 2, 3, 5, 6; 15. 1.

References

Becker, M, Maiman, L. Sociobehavioral determinants of compliance with health and medical care recommendations. Med Care. 1975;13(1):10.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Chronic diseases and health promotion. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm, 2009. [Accessed June 17, 2011].

Chodzko-Zajko, W, et al. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2009;41(7):1510.

Cornett, S. Assessing and addressing health literacy. Online J Issues Nurs. 2009;14(3):10913734.

DiClemente, C, Prochaska, J. Toward a comprehensive transtheoretical model of change. In: Miller WR, Healther N, eds. Treating addictive behaviors. New York: Plenum Press, 1998.

Ebersole, P, et al. Toward healthy aging: human needs and nursing response, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Edelman, CL, Mandle, CL. Health promotion throughout the life span, ed 7. St Louis: Mosby; 2010.

Giger, JN, Davidhizar, RE. Transcultural nursing: assessment and intervention. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Larsen, PD. Chronicity. In Lubkin IM, Larsen PD, eds.: Chronic illness: impact and intervention, ed 7, Boston: Jones & Bartlett, 2009.

Larsen, PD. Illness behavior. In Lubkin IM, Larsen PD, eds.: Chronic illness: impact and intervention, ed 7, Boston: Jones & Bartlett, 2009.

Maier-Lorentz, MM. Transcultural nursing; its importance in nursing practice. J Cult Diversity. 2008;15(1):37.

Mechanic, D. Sociological dimensions of illness behavior. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(9):1207.

Murray, RB, et al. Health promotion strategies through the lifespan, ed 8. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2008.

Narayan, MC. Culture’s effects on pain assessment and management. Am J Nurs. 2010;110(4):38.

Pender, NJ. Health promotion and nursing practice. Norwalk, Conn: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1982.

Pender, NJ. Health promotion and nursing practice, ed 3. Stamford, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1996.

Pender, NJ, Murdaugh, CL, Parsons, MA. Health promotion in nursing practice, ed 5. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2006.

Pender, NJ, Murdaugh, CL, Parsons, MA. Health promotion in nursing practice, ed 6. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2011.

Prochaska, JO. Assessing how people change. Cancer. 1991;67(3:suppl):805.

Rosenstoch, I. Historical origin of the health belief model. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:334.

Singleton, K, Krause, EMS. Understanding cultural and linguistic barriers to health literacy. Online J Issues Nurs. 2009;3(2):2.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010: understanding and improving health, ed 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000.

US Department of Health and Human Services: HealthyPeople.gov, 2011. Accessed June 17, 2011.

US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Healthy People 2000: national health promotion and disease prevention objectives. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 1990.

Villaire, M, Mayer, G. Health literacy: the low hanging fruit in health care reform. J Healthcare Finance. 2009;36(2):55.

World Health Organization Interim Commission. Chronicle of WHO. Geneva: The Organization; 1947.

World Health Organization. Milestones in health promotion: statement from global conferences. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2009.

Yeo, G. How will the US healthcare system meet the challenge of the ethnogeriatric imperative? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1278.

Research Reference

Bertera, EM, Bertera, RL. Fear of falling and activity avoidance in a national sample of older adults in the United States. Health Social Work. 2008;33(1):54.

Byam-Williams, J, Salyer, J. Factors influencing the health-related lifestyle of community-dwelling older adults. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2010;28(2):115.

Callaghan, D. Health behaviors, self-efficacy, self-care, and basic conditioning factors in older adults. Journal of Community Health Nursing. 2005;22(3):169.

Eriksson, M, Svedlund, M. “The intruder”: spouses’ narratives about life with a chronically ill partner. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:324.

Lee, H, et al. Do cultural factors predict mammography behavior among Korean immigrants in the USA? J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(12):2574.

Lee, Y, Park, K. Health practices that predict recovery from functional limitations in older adults. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):25.

Lee-Lin, F, et al. Screening practices among Chinese American immigrants. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36:212.

Wu, TY, Ronis, D. Correlates of recent and regular mammography screening among Asian-American women. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(11):2434.