Pain Management

• Discuss common misconceptions about pain.

• Describe the physiology of pain.

• Identify components of the pain experience.

• Explain how the physiology of pain relates to selecting interventions for pain relief.

• Describe the components of pain assessment.

• Be able to perform an assessment of a patient experiencing pain.

• Explain how cultural factors influence the pain experience.

• Describe guidelines for selecting and individualizing pain interventions.

• Explain various pharmacological approaches to treating pain.

• Describe applications for use of nonpharmacological pain interventions.

• Discuss nursing implications for administering analgesics.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Everyone eventually experiences some type or degree of pain. Although it is the most common reason that people seek health care, pain is not well understood. A person in pain feels distress or suffering and seeks relief. As the nurse you cannot see or feel the patient’s pain. It is purely subjective. No two people experience pain in the same way, and no two painful events create identical responses or feelings in a person. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as “an unpleasant, subjective sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (IASP, 2010).

Congress declared 2000 to 2010 the Decade of Pain Control and Research, yet pain continues to be a leading public health problem in the United States. Providing pain relief is a basic human right and is in the Pain Care Bill of Rights (APF, 2007). According to the American Bar Association (2009), pain management is a basic right of people who are seriously ill. Nurses are legally and ethically responsible for managing pain and relieving suffering.

When caring for patients in pain, consider the nurse-patient relationship, patient advocacy, patient empowerment, compassion, and respect (Vaartio et al., 2009). Caring for patients in pain requires recognition that pain can and should be relieved. Effective communication among the patient, family, and professional caregivers is essential to achieve adequate pain management. You show respect for a patient in pain when you accept McCaffery’s classic definition: “Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he says it does” (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Effective pain management improves quality of life; reduces physical discomfort; promotes earlier mobilization and return to previous activity levels; results in fewer hospital and clinic visits; and decreases hospital lengths of stay, resulting in lower health care costs.

Scientific Knowledge Base

The pain experience is complex, involving physical, emotional, and cognitive components. Pain is subjective and highly individualized. Its stimulus is physical and/or mental in nature. Pain uses a person’s energy. It interferes with personal relationships and influences the meaning of life. You cannot measure it objectively. Only the patient knows whether pain is present and how the experience feels. It is not the responsibility of patients to prove that they are in pain; it is a nurse’s responsibility to accept their report (APS, 2003).

Physiology of Pain

There are four physiological processes of nociceptive (normal) pain: transduction, transmission, perception, and modulation (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). A patient in pain cannot discriminate among the processes. Understanding each process helps you recognize factors that cause pain, symptoms that accompany it, and the rationale for selected therapies.

Thermal, chemical, or mechanical stimuli usually cause pain. Transduction converts energy produced by these stimuli into electrical energy Transduction begins in the periphery when a pain-producing stimulus sends an impulse across a sensory peripheral pain nerve fiber (nociceptor), initiating an action potential. Once transduction is complete, transmission of the pain impulse begins.

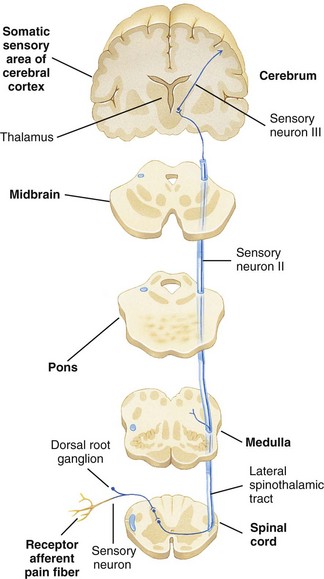

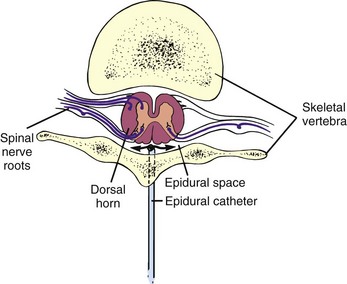

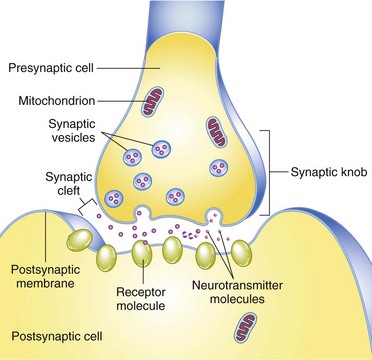

Cellular damage caused by thermal, mechanical, or chemical stimuli results in the release of excitatory neurotransmitters such as prostaglandins, bradykinin, substance P, and histamine (Box 43-1). These pain-sensitizing substances surround the pain fibers in the extracellular fluid, creating an “inflammatory soup,” spreading the pain message and causing an inflammatory response (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). The pain stimulus enters the spinal cord via the dorsal horn and travels one of several routes until ending within the gray matter of the spinal cord. At the dorsal horn substance P is released, causing a synaptic transmission from the afferent (sensory) peripheral nerve to spinothalamic tract nerves, which cross to the opposite side (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011) (Fig. 43-1).

FIG. 43-1 Chemical synapses involve transmitter chemicals (neurotransmitters) that signal postsynaptic cells. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA: Anatomy & physiology, ed 7, St Louis, 2010, Mosby.)

Nerve impulses resulting from the painful stimulus travel along afferent (sensory) peripheral nerve fibers. Two types of peripheral nerve fibers conduct painful stimuli: the fast, myelinated A-delta fibers and the very small, slow, unmyelinated C fibers. The A fibers send sharp, localized, and distinct sensations that specify the source of the pain and detect its intensity. The C fibers relay impulses that are poorly localized, burning, and persistent. For example, after stepping on a nail, a person initially feels a sharp, localized pain, which is a result of A-fiber transmission. Within a few seconds the pain becomes more diffuse and widespread, until the whole foot hurts because of C-fiber innervations (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Along the spinothalamic tract, pain impulses travel up the spinal cord (Fig. 43-2). After the pain impulse ascends the spinal cord, the thalamus transmits information to higher centers in the brain, including the reticular formation, limbic system, somatosensory cortex, and association cortex. Once a pain stimulus reaches the cerebral cortex, the brain interprets the quality of the pain and processes information from past experience, knowledge, and cultural associations in the perception of the pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Perception is the point at which a person is aware of pain. The somatosensory cortex identifies the location and intensity of pain, whereas the association cortex, primarily the limbic system, determines how a person feels about it. There is no single pain center.

As a person becomes aware of pain, a complex reaction occurs. Psychological and cognitive factors interact with neurophysiological ones in the perception of pain. Perception gives awareness and meaning to pain, resulting in a reaction. The reaction to pain includes the physiological and behavioral responses that occur after an individual perceives pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Once the brain perceives pain, there is a release of inhibitory neurotransmitters (see Box 43-1) such as endogenous opioids, serotonin, norepinephrine, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA), which work to hinder the transmission of pain and help produce an analgesic effect (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). This inhibition of the pain impulse is the fourth and last phase of the nociceptive process known as modulation (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

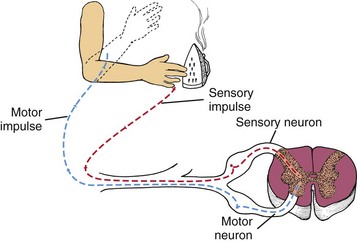

A protective reflex response also occurs with pain reception (Fig. 43-3). A-delta fibers send sensory impulses to the spinal cord, where they synapse with spinal motor neurons. The motor impulses travel via a reflex arc along efferent (motor) nerve fibers back to a peripheral muscle near the site of stimulation, thus bypassing the brain. Contraction of the muscle leads to a protective withdrawal from the source of pain. For example, when you accidentally touch a hot iron, you feel a burning sensation, but your hand also reflexively withdraws from the surface of the iron.

Gate-Control Theory of Pain

Melzack and Wall’s gate-control theory (1965) first suggested that pain has emotional and cognitive components in addition to a physical sensation. According to this theory, gating mechanisms located along the central nervous system regulate or even block pain impulses. Pain impulses pass through when a gate is open and are blocked when a gate is closed. Closing the gate is the basis for nonpharmacological pain-relief interventions. You gain a useful conceptual framework for pain management by understanding the physiological, emotional, and cognitive influences on the gates. For example, factors such as stress and exercise increase the release of endorphins, often raising an individual’s pain threshold (the point at which a person feels pain). Because the amount of circulating substances varies with every individual, the response to pain varies.

Physiological Responses

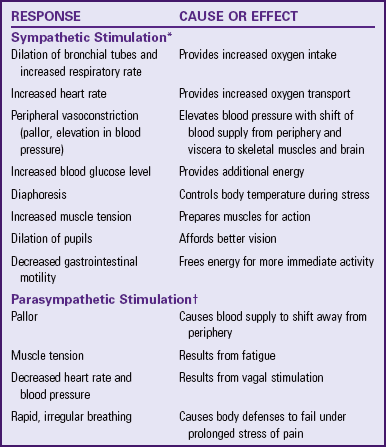

As pain impulses ascend the spinal cord toward the brainstem and thalamus, the stress response stimulates the autonomic nervous system. Pain of low to moderate intensity and superficial pain elicit the fight-or-flight reaction of the general adaptation syndrome (see Chapter 37). Stimulation of the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system results in physiological responses (Table 43-1). Continuous, severe, or deep pain typically involving the visceral organs (e.g., with a myocardial infarction or colic from gallbladder or renal stones) activates the parasympathetic nervous system. Sustained physiological responses to pain sometimes seriously harm individuals. Except in cases of severe traumatic pain, which causes a person to go into shock, most people adapt to their pain, and their physical signs return to normal. Thus patients in pain do not always have changes in their vital signs. Changes in vital signs more often indicate problems other than pain.

Behavioral Responses

If left untreated or unrelieved, pain significantly alters quality of life. It usually interferes with every aspect of a person’s life, which supports why effective pain management is essential. It threatens physical and psychological well-being. Some patients choose not to report pain if they believe that it inconveniences others or if it signals loss of self-control, and some endure severe pain without assistance. Encourage your patients to accept pain-relieving measures so they remain active and continue to maintain daily activities. In contrast, other patients seek relief before pain occurs, having learned that prevention is easier than treatment. A patient’s ability to tolerate pain significantly influences your perceptions of the degree of the patient’s discomfort. Patients who have a low pain tolerance (level of pain a person is willing to accept) are sometimes inaccurately perceived as complainers. Teach patients the importance of reporting their pain sooner rather than later.

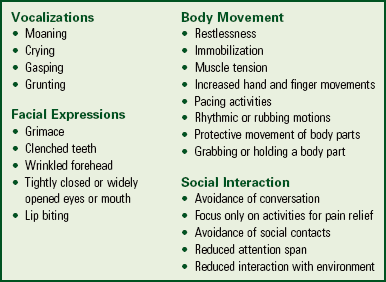

Body movements and facial expressions indicating pain include clenched teeth, holding the painful area, bent posture, and grimacing. Some patients cry or moan, are restless, or make frequent requests of a nurse. You soon learn to recognize patterns of behavior that reflect pain. This becomes especially important in patients who are unable to report their pain such as the cognitively impaired. However, lack of pain expression does not indicate that the patient is not experiencing pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Types of Pain

Pain is categorized by duration (acute or chronic) or pathological condition (e.g., cancer or neuropathic).

Acute/Transient Pain

Acute pain is protective, has an identifiable cause, is of short duration, and has limited tissue damage and emotional response. It eventually resolves, with or without treatment, after an injured area heals. Because acute pain has a predictable ending (healing) and an identifiable cause, health team members are usually willing to treat it aggressively. Unrelieved acute pain can progress to chronic pain (Kehlet et al., 2006).

Acute pain seriously threatens a patient’s recovery by resulting in prolonged hospitalization, increased risks of complications from immobility (see Chapter 47), and delayed rehabilitation. Physical and psychological progress is delayed as long as acute pain persists because a patient focuses all energy on pain relief. Efforts aimed at teaching and motivating the patient toward self-care are often hampered until the pain is successfully managed. Complete pain relief is not always achievable, but reducing pain to a tolerable level is realistic. Thus a primary nursing goal is to provide pain relief that allows patients to participate in their recovery.

Chronic/Persistent Noncancer Pain

Unlike acute pain, chronic pain is not protective and thus serves no purpose. Chronic pain lasts longer than 6 months and is constant or recurring with a mild-to-severe intensity (Ackley and Ladwig, 2011). It does not always have an identifiable cause and leads to great personal suffering. Examples of chronic noncancer pain include arthritis, low back pain, myofascial pain, headache, and peripheral neuropathy. Chronic pain is usually non–life threatening. Sometimes an injured area healed long ago, yet the pain is ongoing and does not respond to treatment.

The possible unknown cause of chronic pain, combined with the unrelenting nature and uncertainty of its duration, frustrates a patient, frequently leading to psychological depression and even suicide. Chronic pain is a major cause of psychological and physical disability, leading to problems such as job loss, inability to perform simple daily activities, sexual dysfunction, and social isolation.

The person with chronic noncancer pain often does not show obvious symptoms and does not adapt to the pain. Rather, he or she seems to suffer more with time because of physical and mental exhaustion. Associated symptoms of chronic pain include fatigue, insomnia, anorexia, weight loss, apathy, hopelessness, and anger. Chronic pain creates the uncertainty of how one will feel from day to day. If there is no objective evidence to confirm the existence of pain, the “burden of proof” lies with the patient (Shaw, 2006). Health care workers are usually less willing to treat chronic noncancer pain with opioids, although a policy statement supports the use of opioids for it (Chou et al., 2009). In addition, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (2010) developed “Practice Guidelines for Chronic Pain Management,” which includes the use of opioids. Often a person with chronic pain who consults with numerous health care providers is labeled a drug seeker, when he or she is actually seeking adequate pain relief. This situation is called pseudoaddiction. Nurses need to discourage patients from having multiple health care providers for treating pain and refer them to pain specialists. Pain centers offer a holistic approach to chronic pain using both nonpharmacological and pharmacological strategies for pain management (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Chronic Episodic Pain

Pain that occurs sporadically over an extended period of time is episodic pain. Pain episodes last for hours, days, or weeks. Examples are migraine headaches and pain related to sickle cell disease (Gruener and Lande, 2006).

Cancer Pain

Not all patients with cancer experience pain. For those who do, as many as 90% are able to have their pain managed with relatively simple means (Lehne, 2010). Some patients with cancer experience acute and/or chronic pain. The pain is nociceptive and/or neuropathic. Cancer pain is usually caused by tumor progression and related pathological processes, invasive procedures, toxicities of treatment, infection, and physical limitations. A patient senses pain at the actual site of the tumor or distant to the site, called referred pain. Assess reports of new pain by a patient with existing pain. Although the treatment of cancer pain has improved, undertreatment of cancer pain continues. Approximately 70% to 90% of patients with advanced cancer experience pain. Sixty percent of them report moderate-to-severe pain (Maxwell et al., 2005).

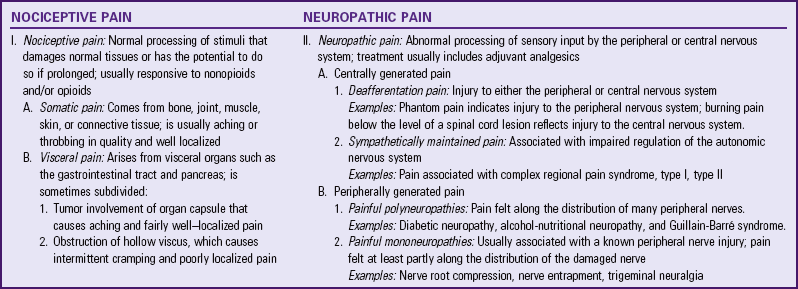

Pain by Inferred Pathological Process

Identifying the cause of pain is the first step in successful treatment. Nociceptive pain includes somatic (musculoskeletal) and visceral (internal organ) pain. Neuropathic pain arises from abnormal or damaged pain nerves (Table 43-2). Each of these pathological processes has distinct pain characteristics. The pain assessment section discusses these further.

Idiopathic Pain

Idiopathic pain is chronic pain in the absence of an identifiable physical or psychological cause or pain perceived as excessive for the extent of an organic pathological condition. An example of idiopathic pain is complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). Research is needed to better identify the causes of idiopathic pain, thus leading to a more effective treatment (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Nursing Knowledge Base

Nursing knowledge of pain mechanisms and interventions continues to grow through nursing research. This section explores factors that influence the pain experience.

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs

Attitudes of nurses and other health care providers affect pain management. The traditional medical model of illness generates attitudes about pain. This model suggests that physical problems result from physical causes. Thus pain is a physical response to organic dysfunction. When there is no obvious source of pain (e.g., the patient with chronic low back pain or neuropathies), health care providers sometimes stereotype pain sufferers as malingerers, complainers, or difficult patients.

Studies of nurses’ attitudes regarding pain management show that a nurse’s personal opinion about a patient’s report of pain affects pain assessment and titration of opioid doses. The amount of analgesia administered varies based on whether a patient is grimacing or smiling during the nurse’s assessment (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Nurses with more than 6 years of work experience, higher job motivation, and perceived higher levels of pain-care skills in themselves often use more patient advocacy skills in providing pain management for patients (Vaartio et al., 2009).

Nurses’ assumptions about patients in pain seriously limit their ability to offer pain relief. Biases based on culture, education, and experience influence everyone. Too often nurses allow misconceptions about pain (Box 43-2) to affect their willingness to intervene. Some nurses avoid acknowledging a patient’s pain because of their own fear and denial. They do not believe a patient’s report of pain if he or she does not look in pain. You are entitled to your personal beliefs; however, you must accept a patient’s report of pain and act according to professional guidelines, standards, position statements, policies and procedures, and evidence-based research findings (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

To help a patient gain pain relief, view the experience through the patient’s eyes. Acknowledging personal prejudices or misconceptions helps you address patient problems more professionally. When you become an active, knowledgeable observer of a patient in pain, you more objectively analyze the pain experience. The patient makes the diagnosis that pain is present, and you apply interventions that ultimately give relief.

Factors Influencing Pain

Pain is a complex process, involving physiological, social, spiritual, psychological, and cultural influences. Thus each individual’s pain experience is different. Consider all factors that affect the patient in pain to ensure a holistic approach to the assessment and care of the patient.

Physiological Factors

Age: Age influences pain, particularly in infants and older adults. Developmental differences found between these age-groups influence how children and older adults react to pain. Young children have trouble understanding pain and the procedures that cause it. If they have not developed full vocabularies, they have difficulty verbally describing and expressing pain to parents or caregivers. Toddlers and preschoolers are unable to recall explanations about pain or associate it with experiences that occur in various situations. With these developmental considerations in mind, you need to adapt approaches for assessing a child’s pain, including what to ask and the behaviors to observe, and how to prepare a child for a painful medical procedure.

Pain is not an inevitable part of aging. However, older adults have a greater likelihood of developing pathological conditions, which are accompanied by pain. Serious impairment of functional status often accompanies pain in older patients. Pain potentially reduces mobility, activities of daily living (ADLs), social activities, and activity tolerance. The presence of pain in an older adult requires aggressive assessment, diagnosis, and management (Box 43-3).

The ability of older patients to interpret pain is complicated. They often suffer from multiple diseases with vague symptoms that affect similar parts of the body. You need to make detailed assessments when there is more than one source of pain. Different diseases sometimes cause similar symptoms. For example, chest pain does not always indicate a heart attack; it also is a symptom of arthritis of the spine or an abdominal disorder. When older adults experience cognitive impairment and confusion, they have difficulty recalling pain experiences and providing detailed explanations of their pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). You need to address misconceptions about pain management in the very young and in older adults before intervening for a patient (Tables 43-3 and 43-4).

TABLE 43-3

| MISCONCEPTION | CORRECTION |

| Infants cannot feel pain. | Infants have the anatomical and functional requirements for pain processing by mid-to-late gestation. |

| Infants are less sensitive to pain than older children and adults. | Term neonates have the same sensitivity to pain as older infants and children. Preterm neonates have a greater sensitivity to pain than term neonates or older children. |

| Infants cannot express pain. | Although infants cannot verbalize pain, they respond with behavioral cues and physiological indicators that are observable. |

| Infants must learn about pain from previous painful experiences. | Pain requires no prior experience; infants do not need to learn it from earlier painful experience. It occurs with the first insult. |

| You cannot accurately assess pain in infants. | You use behavioral cues (e.g., facial expressions, cry, body movements) and physiological indicators of pain (e.g., changes in vital signs) to reliably and validly assess pain in infants. |

| You cannot safely give analgesics and anesthetics to infants and neonates because of their immature capacity to metabolize and eliminate drugs and their sensitivity to opioid-induced respiratory depression. | Infants are very sensitive to drugs. Response to drugs is often intense and prolonged. Absorption is faster than expected. Dosages of drugs excreted by the kidneys need to be reduced (Lehne, 2010). Prescribers carefully select the medication, dosage, administration route, and time. Nurses monitor frequently for desired and undesired effects. Nurses also follow medication orders to titrate and wean medications to minimize adverse effects. |

TABLE 43-4

Misconceptions About Pain in Older Adults

| MISCONCEPTION | CORRECTION |

| Pain is a natural outcome of growing old. | Older adults are at greater risk (as much as twofold) than younger adults for many painful conditions; however, pain is not an inevitable result of aging. |

| Pain perception, or sensitivity, decreases with age. | This assumption is unsafe. Although there is evidence that emotional suffering specifically related to pain is possibly less in older than in younger patients, no scientific basis exists for the claim that a decrease in perception of pain occurs with age or that age dulls sensitivity to pain. |

| If the older patient does not report pain, he or she does not have pain. | Older patients commonly underreport pain. Reasons include expecting to have pain with increasing age; not wanting to alarm loved ones; being fearful of losing their independence; not wanting to distract, anger, or bother caregivers; and believing that caregivers know they have pain and are doing all they can to relieve it. The absence of a report of pain does not mean the absence of pain. |

| If an older patient appears to be occupied, asleep, or otherwise distracted from pain, he or she does not have pain. | Older patients often believe that it is unacceptable to show pain and have learned to use a variety of ways to cope with it (e.g., many patients use distraction successfully for short periods of time). Sleeping is sometimes a coping strategy; alternately, it indicates exhaustion, not pain relief. Do not make assumptions about the presence or absence of pain solely on the basis of a patient’s behavior. |

| The potential side effects of opioids make them too dangerous to use to relieve pain in older adults. | Opioids are safe to use in older adults with moderate-to-severe pain (Arnstein, 2010). Although the opioid-naive older adult is usually more sensitive to opioids, this does not justify withholding their use in pain management. Slow titration prevents potentially dangerous opioid-induced side effects. Regular, frequent monitoring and assessment of a patient’s response are necessary. Adjust dose and interval between doses when you detect side effects. If necessary, administer an opioid antagonist drug to reverse clinically significant respiratory depression. |

| Patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive impairments do not feel pain, and their reports of pain are most likely invalid. | No evidence exists that cognitively impaired older adults experience less pain or that their reports of pain are less valid than those of individuals with intact cognitive function (Herr, 2010). Patients with dementia or other deficits of cognition most likely suffer significant unrelieved pain and discomfort. Assessment of pain in these patients is challenging but possible. The best approach is to accept a patient’s report of pain and treat it as you would treat it in an individual with intact cognitive function. |

| Older patients report more pain as they age. | Even though older patients experience a higher incidence of painful conditions such as arthritis, osteoporosis, peripheral vascular disease, and cancer than younger patients, studies show that they underreport pain. Many older adults grew up valuing the ability to “grin and bear it” (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). |

Fatigue: Fatigue heightens the perception of pain and decreases coping abilities. If it occurs along with sleeplessness, the perception of pain is even greater. Pain is often experienced less after a restful sleep than at the end of a long day.

Genes: Research on healthy human subjects suggests that genetic information passed on by parents possibly increases or decreases the person’s sensitivity to pain and determines pain threshold or pain tolerance. A study of twins by Kato et al. (2006) suggested modest genetic influence in the development of chronic widespread pain without significant differences experienced between men and women.

Neurological Function: A patient’s neurological function influences the pain experience. Any factor that interrupts or influences normal pain reception or perception (e.g., spinal cord injury, peripheral neuropathy, or neurological disease) affects the patient’s awareness of and response to pain. Some pharmacological agents (analgesics, sedatives, and anesthetics) influence pain perception and response and thus require close monitoring.

Social Factors

Attention: The degree to which a patient focuses attention on pain influences pain perception. Increased attention is associated with increased pain, whereas distraction is associated with a diminished pain response. This concept is one that nurses apply in various pain-relief interventions such as relaxation, guided imagery, and massage. By focusing patients’ attention and concentration on other stimuli, their perception of pain declines (see Chapter 32).

Previous Experience: Each person learns from painful experiences. Prior experience does not mean that a person accepts pain more easily in the future. Previous frequent episodes of pain without relief or bouts of severe pain cause anxiety or fear. In contrast, if a person repeatedly experiences the same type of pain that was relieved successfully in the past, the patient finds it easier to interpret the pain sensation. As a result, the patient is better prepared to take necessary actions to relieve the pain.

When a patient has no experience with a painful condition, the first perception of it often impairs the ability to cope. For example, after abdominal surgery it is common for patients to experience severe incisional pain for several days. Unless a patient knows this is a common occurrence following surgery, the onset of pain seems like a serious complication. Rather than participate actively in postoperative breathing exercises (see Chapter 50), the patient lies immobile in bed and breathes shallowly because of fear that something is not right. In the anticipatory phase of the pain experience, you need to prepare a patient with a clear explanation of the type of pain to expect and methods to reduce it. This usually results in a reduced perception of pain.

Family and Social Support: People in pain often depend on family members or close friends for support, assistance, or protection. Although pain still exists, the presence of family or friends can often make the pain experience less stressful. The presence of parents is especially important for children experiencing pain.

Spiritual Factors: Spirituality stretches beyond religion and includes an active searching for meaning to situations in which one finds oneself. Spiritual questions include “Why has this happened to me?” “Why am I suffering?” Spiritual pain goes beyond what we can see. “Why has God done this to me?” “Is this suffering teaching me something?” Other spiritual concerns include loss of independence and becoming a burden to family (Otis-Green et al., 2002). Consider making a referral to pastoral care for patients in pain. Recall that pain is an experience that has physical and emotional components. Thus providing interventions designed to treat both aspects is essential for the best possible pain management (see Chapter 35).

Psychological Factors

Anxiety: A person perceives pain differently if it suggests a threat, loss, punishment, or challenge. For example, a woman in labor perceives pain differently than a woman with a history of cancer who is experiencing a new pain and fearing recurrence. In addition, the degree and quality of pain perceived by a patient influences the meaning of pain. The relationship between pain and anxiety is complex. Anxiety often increases the perception of pain, and pain causes feelings of anxiety. It is difficult to separate the two sensations.

Critically ill or injured patients who perceive a lack of control over their environment and care have high anxiety levels. This anxiety leads to serious pain-management problems. Pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches to the management of anxiety are appropriate; however, anxiolytic medications are not a substitute for analgesia (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

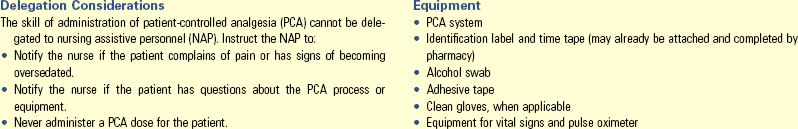

Coping Style: Coping style influences the ability to deal with pain. Persons with internal loci of control perceive themselves as having control over events in their life and the outcomes such as pain. In contrast, persons with external loci of control perceive that other factors in their life such as nurses are responsible for the outcome of events. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) uses this concept. Patients who self-administer small doses of intravenous (IV) pain medication using PCA during an acute episode successfully achieve pain control more quickly than those who rely on nurses to administer intermittent doses of pain medications.

You need to understand patients’ coping resources during painful experiences. Use resources such as communicating with a supportive family, being active, or praying, in your plan of care to support patients and offer a degree of pain relief (see Chapter 37).

Cultural Factors

The meaning that a person associates with pain affects the experience of pain and how one adapts to it. This is often closely associated with a person’s cultural background. Cultural beliefs and values affect how individuals cope with pain. Individuals learn what is expected and accepted by their culture, including how to react to pain. Health care providers often mistakenly assume that everyone responds to pain in the same way. Different meanings and attitudes are associated with pain across various cultural groups. An understanding of the cultural meaning of pain helps you design culturally sensitive care for people with pain (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Culture affects pain expression. Some cultures believe that it is natural to be demonstrative about pain. Others tend to be more introverted. In addition, it is also important to know to what extent a member of a particular culture has assimilated into American society. For example, if several generations of a Hispanic patient’s family have lived in the United States, the influence of the Spanish culture may be limited, whereas newly immigrated patients still embrace their cultural norms.

As a nurse, explore the impact of cultural differences on a patient’s pain experience and make adjustments to the plan of care (Box 43-4). Work with the patient and family to facilitate communication about the assessment and management of pain. Find a culturally appropriate assessment tool and communicate use of that tool to other health care providers.

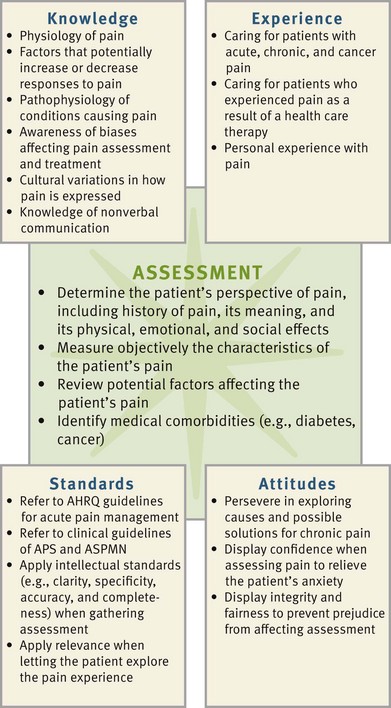

Critical Thinking

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. To make clinical judgments, you anticipate the information you need, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care. A patient’s condition or situation is always changing. During assessment consider all critical thinking elements that lead to appropriate nursing diagnoses.

Knowledge of pain physiology and the many factors that influence pain help you manage a patient’s pain. Previous experience in caring for patients with pain sharpens your assessment skills and ability to choose effective therapies. Critical thinking attitudes and intellectual standards ensure the aggressive assessment, creative planning, and thorough evaluation needed to obtain an acceptable level of patient pain relief. Successful pain management does not necessarily mean pain elimination but rather attainment of a mutually agreed-on pain-relief goal that allows patients to control their pain instead of the pain controlling them.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

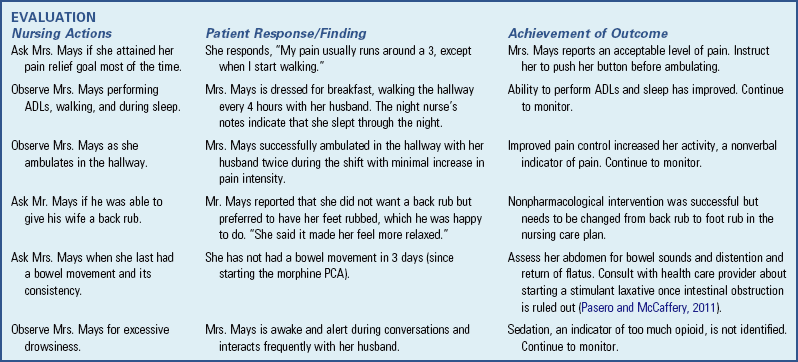

Nurses approach pain management systematically to understand and treat a patient’s pain. Successful management of pain depends on establishing a relationship of trust among health care providers, patient, and family. Pain management extends beyond pain relief, encompassing the patient’s quality of life and ability to work productively, enjoy recreation, and function normally in the family and society.

The American Nurses Association (ANA) (2005) upholds that pain assessment and management is within the scope of every nurse’s practice. Thus the ANA offers a certification examination in pain management to staff nurses (http://www.aspmn.org/certification). Several clinical guidelines are available for managing pain in specific disorders. Guidelines are available through the American Pain Society (APS) on the management of pain in the primary care setting; sickle cell pain; cancer pain in adults and children; and pain in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and juvenile chronic arthritis. Sigma Theta Tau International offers guidelines for the older adult on their website (www.geriatricpain.org). In addition, the National Guidelines Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov) posts a variety of pain-management guidelines, including ones on acute, chronic, spinal, chest, low back, cancer, and pancreatic pain.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Many people view pain as a part of life. Some patients experience it for hours or days before seeking health care assistance. They often expect and even accept a certain amount of pain while being hospitalized. Asking patients about their tolerable pain level is the first step in helping them regain control. Assessing previous pain experiences and effective home interventions provides a foundation on which you can build. Patients expect nurses to accept their reports of pain and be prompt in meeting their pain needs.

When assessing pain, be sensitive to the level of discomfort and determine what level will allow your patient to function. For example, when caring for a patient with pain, you ask, “What level of pain will allow you to walk down the hall?” The patient answers that walking is possible when pain is at a level of 2 on a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being no pain and 10 being worst pain imaginable. You then focus efforts on decreasing the pain to that level. If pain is acute or severe, it is unlikely that the patient is able to provide a detailed description of the entire experience. During an episode of acute pain you primarily assess its location, severity, and quality. Collect a more detailed acute pain assessment when the patient is more comfortable (Box 43-5). For patients with chronic pain, a thorough pain assessment includes affective, cognitive, behavioral, spiritual, and social dimensions. In the home care setting family members assess pain. Using the ABCs of pain management is an effective way to manage pain (Box 43-6).

Because pain is not static but dynamic, you monitor it on a regular basis along with other vital signs. Some institutions treat pain as the fifth vital sign. Pain assessment is not simply a number. Relying solely on a number is unsafe (Vila et al., 2005). Although pain assessment is a nursing function, nursing assistive personnel (NAP) also screen for pain (Schulman-Green et al., 2005). NAP have the responsibility to inform the nurse immediately when a patient is having pain so the nurse is able to confirm the assessment and begin appropriate treatment.

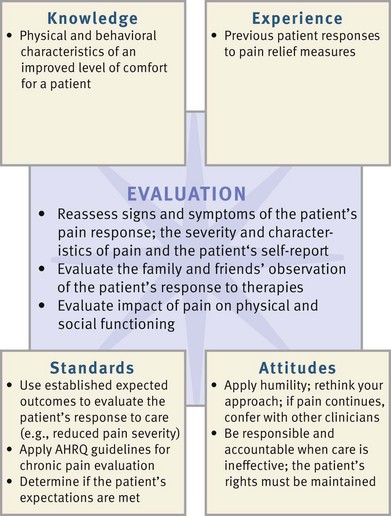

The ability to establish a nursing diagnosis, decide on appropriate interventions, and evaluate the patient’s response (outcomes) to interventions depends on the fundamental activity of a factual, timely, accurate pain assessment (Fig. 43-4). The core of this complex activity is the exploration of the pain experience through the eyes of the patient. Nurses use a variety of tools to assess nociceptive pain and neuropathic pain (Jensen et al., 2006). The goal in using these tools is to identify how much pain exists without interfering with patient function, not to identify how much pain the patient tolerates.

FIG. 43-4 Critical thinking model for pain assessment. AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; ANA, American Nurses Association; ASPMN, American Society for Pain Management Nursing.

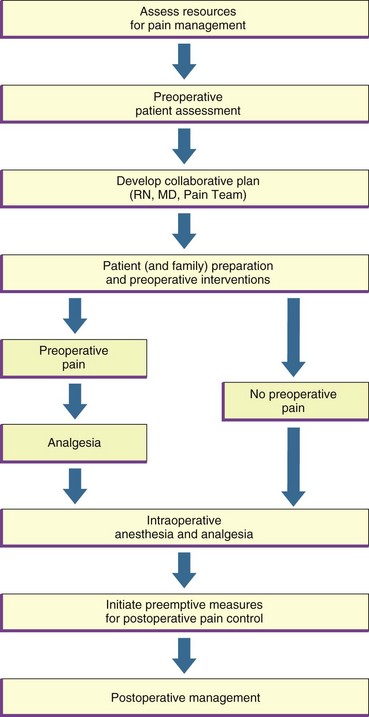

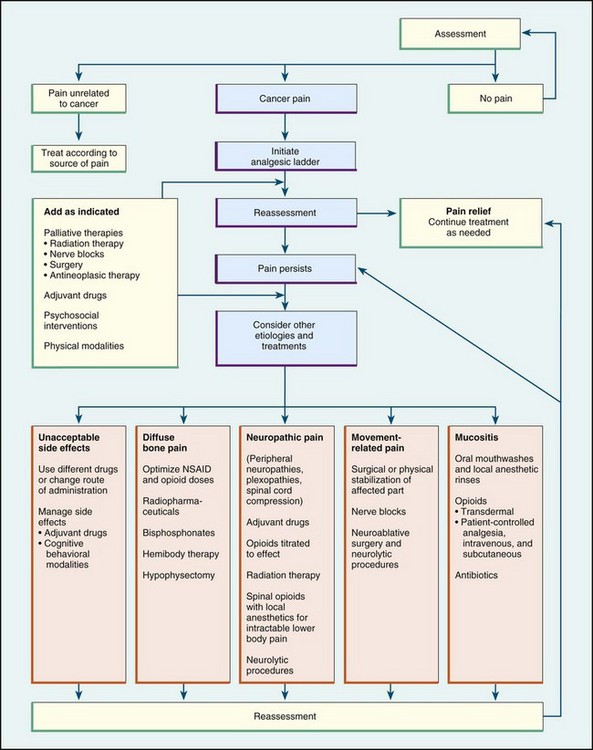

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) established specific guidelines for assessing patients with acute and cancer pain. The focus is on planning successful pain-management interventions before a patient has pain. Because it involves a collaborative approach, the AHRQ pain treatment flow chart (Fig. 43-5) offers a useful conceptual approach to the control of acute pain. Patients need to understand that informed reporting of pain is valuable and necessary if the health care team is to manage it effectively.

FIG. 43-5 Pain treatment flow chart: preoperative and intraoperative phases. MD, Medical doctor; RN, registered nurse. (From Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: Acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma, Clinical Practice Guideline, AHCPR Pub No. 92-0032, Rockville, Md, 1992, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; and Jacox A et al: Management of cancer pain, Clinical Practice Guideline No. 9, AHCPR Pub No. 94-0592, Rockville, Md, 1994, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services.)

Always be aware of possible errors in pain assessment (Box 43-7). Using the right tools and methods helps you avoid errors and ensures that you choose the right pain interventions. Failure of clinicians to assess a patient’s pain, accept the findings, and treat the report of pain is a common cause of unrelieved pain and suffering (Hughes, 2008).

Patient’s Expression of Pain

A patient’s self-report of pain is the single most reliable indicator of its existence and intensity (APS, 2003; Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Pain is individualistic. Many patients fail to report or discuss discomfort. At the same time many nurses believe that patients report pain if they have it. If patients sense that you doubt that pain exists, they share little information about their pain experience or minimize their report. You need to establish a caring therapeutic relationship that allows for open communication. Simple measures such as sitting when talking to patients about pain lets them know that you are sincerely concerned about their pain.

Patients unable to communicate effectively often require special attention during assessment. Children, people who are developmentally delayed, patients who are psychotic, the critically ill, patients with dementia, and patients who do not speak English all require different approaches. Herr et al. (2006a, 2006b) examined various pain behavior assessment tools used with patients who were cognitively impaired. Although no one tool had sufficient reliability and validity, there are clinical practice recommendations (Box 43-8). However, you need to understand that “the number obtained when using a pain-behavior scale is a pain-behavior score, not a pain-intensity rating” (Pasero and McCaffery, 2005). These tools identify the presence of pain but do not determine its intensity.

Patients with cognitive impairments often require simple assessment approaches involving close observation of behavior changes, especially with movement. Patients who are critically ill and have a clouded sensorium or the presence of nasogastric tubes or artificial airways require you to ask specific questions that they can answer with a nod of the head or by writing out a response. If the patient speaks a different language, pain assessment is difficult. An interpreter is often necessary (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Characteristics of Pain

Assessment of common characteristics of pain helps you form an understanding of the type of pain, its pattern, and the types of interventions that bring relief. Use of instruments to quantify the extent and degree of pain depends on a patient being cognitively alert enough to be able to understand your instructions.

Onset and Duration: Ask questions to determine the onset, duration, and sequence of pain. When did it begin? How long has it lasted? Does it occur at the same time each day? How often does it recur?

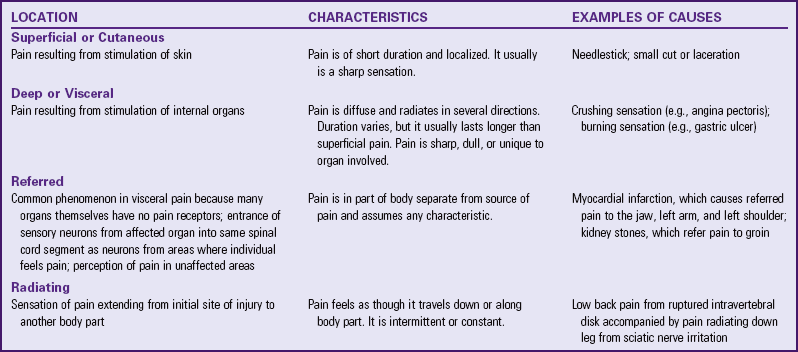

Location: To assess pain location, ask the patient to describe or point to all areas of discomfort. Do not assume that your patient’s pain always occurs in the same location. When describing pain location, use anatomical landmarks and descriptive terminology. The statement “Pain is localized in the upper right abdominal quadrant” is more specific than “The patient states the pain is in the abdomen.” Pain classified by location is superficial or cutaneous, deep or visceral, referred, or radiating (Table 43-5).

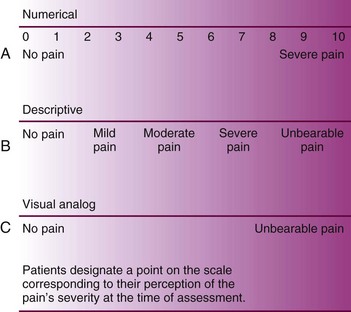

Intensity: One of the most subjective and therefore most useful characteristics for reporting pain is its severity or intensity. Nurses use a variety of pain scales to help patients communicate their pain intensity. Examples of pain intensity scales include the verbal descriptor scale (VDS), the numerical rating scale (NRS), and the visual analogue scale (VAS) (Fig. 43-6). When using the NRS, a report of 0 to 3 indicates mild pain; 4 to 6, moderate pain; and 7 to 10, severe pain, considered a pain emergency (Miaskowski, 2005). These scales work best when assessing pain intensity before and after therapeutic interventions. Many of them are available in several languages to aid nurses when an interpreter is not present (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). In addition to the current pain level, also ask patients to rate their average pain and the worst pain they have had over the past 24 hours.

Although different patients prefer different pain scales, it is important for you to select and consistently use the same scale with a specific patient. Do not use a pain scale to compare the pain of one patient to that of another.

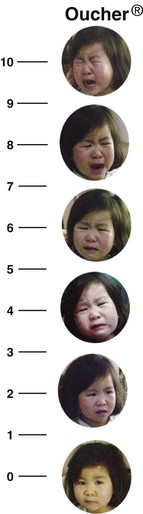

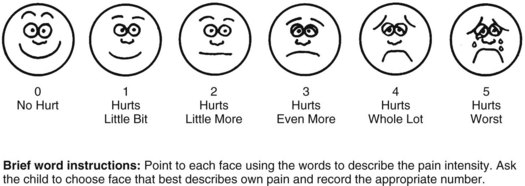

Assessing pain intensity in children requires special techniques. Children’s verbal statements are most important (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Young children do not always know what the word pain means; therefore assessment requires you to use words such as owie, boo-boo, or hurt. Some unique tools are available to measure pain intensity in children. The “Oucher” (Beyer et al., 1992) uses photographs of the face of a child (in increasing levels of discomfort) to cue children into understanding pain and its severity. A child points to a face on the tool, thus simplifying the task of describing the pain. There are ethnic versions of the tool (Fig. 43-7). The FACES scale (Wong and Baker, 1988) assesses pain in verbal children (Fig. 43-8). The scale consists of six cartoon faces ranging from a smiling face (“no hurt”) to increasingly less happy faces; to a final sad, tearful face (“hurts worst”). Children as young as 3 years of age use the scale. Nurses use a variety of other tools to assess pain in neonates, infants, nonverbal toddlers, and children with cognitive impairments.

Quality: Because there is no common or specific pain vocabulary in general use, the words patients choose to describe pain vary. Patients of American descent often use hurt and ache to describe their pain, reserving the word pain for severe discomfort. Always use words other than pain to obtain an accurate report. For example, you say, “Tell me what your discomfort feels like.” The patient likely describes the pain as crushing, throbbing, sharp, or dull. Although a list of descriptive terms is available, it is more accurate to have patients describe the pain in their own words whenever possible.

There is some consistency in the way people describe certain types of pain. The pain associated with a myocardial infarction is often described as crushing or viselike; whereas the pain of a surgical incision is often described as dull, aching, and throbbing, indicating nociceptive pain. Neuropathic pain is usually burning, shooting, or electric-like (Williams, 2006). When a patient’s descriptions fit the pattern forming in the assessment, you then make a clearer analysis of the nature and type of pain. This leads to more appropriate pain management because you treat nociceptive and neuropathic pain differently.

Pain Pattern: Various factors affect the pattern of pain. It helps to assess specific events or conditions that precipitate or aggravate pain. Ask the patient to describe activities that cause pain such as physical movement or food. Also ask him or her to demonstrate actions that cause a painful response such as coughing or turning a certain way. For example, with a ruptured intravertebral disk the low back pain usually radiates down the leg to the foot, and bending over or lifting objects aggravates it. Asking the patient if there is a particular time of day that the pain is worse or if the pain is intermittent, constant, or a combination helps you plan interventions to prevent it from occurring or worsening.

Relief Measures: It is useful to know whether a patient has an effective way of relieving pain such as changing position, using ritualistic behavior (pacing, rocking, or rubbing), eating, meditating, praying, or applying heat or cold to the painful site. The patient’s methods are ones you can use for treatment. Patients gain trust when they know you are willing to try their relief measures. They also gain a sense of control over the pain instead of the pain controlling them. Assessment of relieving factors includes identification of all the patient’s health care providers (e.g., internist, orthopedist, acupuncturist, chiropractor, or dentist).

Contributing Symptoms: Some symptoms (depression, anxiety, fatigue, sedation, anorexia, sleep disruption, spiritual distress, and guilt) cause worsening of pain. You need to assess for these associated symptoms and evaluate their effects on the patient’s pain perception. Reporting and treating associated symptoms contributes to successful pain management.

Effects of Pain on the Patient: Pain alters a person’s lifestyle and affects psychological well-being. Chronic/persistent pain causes suffering, loss of control, loneliness, disabilities, exhaustion, and impaired quality of life. By recognizing the effects that pain has on patients, you better understand the patient’s experience and provide the best pain management. When a patient is in pain, you need to conduct a focused physical and neurological examination and observe for nonverbal responses to pain (e.g., “grimacing, rigid body posture, limping, frowning, or crying”) (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Examine the painful area to see if palpation or manipulation of the site increases pain.

Behavioral Effects: When a patient has pain, assess verbalization, vocal response, facial and body movements, and social interaction. A verbal report of pain is a vital part of assessment. You need to be willing to listen and understand. Many patients are unable to communicate their pain. An infant or a patient who is unconscious, disoriented or confused, aphasic or who speaks a foreign language is unable to explain the pain experience. In these cases it is especially important for you to be alert for behaviors that indicate pain (Box 43-9).

The nonverbal expression of pain either supports or contradicts other information about it. If a woman in labor reports that her labor pains are occurring more frequently and if she begins to massage her abdomen more often, this confirms her report. If a patient reports severe abdominal pain but continues to grasp the chest, a more detailed assessment is necessary.

Influence on Activities of Daily Living: Patients who live with daily pain are less able to participate in routine activities, which results in physical deconditioning. Assessment of these changes reveals the extent of the patient’s disability and adjustments necessary to help patients participate in self-care. Your primary goal as a nurse is to improve patient function.

Ask the patient whether pain interferes with sleep. Some patients experience difficulty in falling asleep and/or staying asleep. The pain awakens the patient during the night and makes it hard to fall back to sleep. Consider giving medications or trying nonpharmacological interventions to promote sleep (see Chapter 42). Do not use medications that promote sleep as a substitute for pain relief.

Depending on the location of the pain, some patients have difficulty independently performing ADLs. For example, some pain restricts mobility to the point at which the patient is no longer able to bathe in a bathtub. Patients with severe arthritis find it painful to grasp eating utensils or lower themselves to a toilet seat. Assess the patient’s need for assistance with self-care activities and collaborate with members of the health care team (e.g., physical and occupational therapy). Also consider the need for family members or friends to assist patients with basic hygiene.

Pain sometimes impairs the ability to maintain normal sexual relations. Include in your assessment the extent to which pain affects the patient’s sexual activity. It also helps to learn whether a patient is physically unable to participate or if pain reduces the desire for sexual intercourse.

Pain threatens a person’s ability to work. The more physical activity required in a job, the greater the risk of discomfort when the pain is associated with movement. Pain related to emotional stress increases in individuals whose jobs involve stressful decision making. Assess the work that patients do and their abilities to function in their jobs. Assess the daily chores of homemakers in the same manner as the duties involved in jobs outside the home. Also assess whether it is necessary for patients to stop activity occasionally because of pain, and then help them select ways to minimize or control it so they are able to remain productive.

Include an assessment of the effect of pain on social activities. Some pain is so debilitating that the patient becomes too exhausted to socialize. Identify the patient’s normal social activities, the extent to which activities have been disrupted, and the desire to participate in these activities.

Nursing Diagnosis

You make an accurate diagnosis only after you have performed a complete assessment. The development of an accurate nursing diagnosis for a patient in pain results from thorough data collection and analysis (Box 43-10). Careful assessment reveals the presence or potential for pain. In addition, examine the patient’s history for recent procedures or preexisting painful conditions.

The nursing diagnosis focuses on the specific nature of the pain to identify the most useful types of interventions for alleviating it and improving the patient’s function. Acute pain related to physical trauma and acute pain related to natural childbirth processes require very different nursing interventions. Accurate identification of related factors is necessary in choosing appropriate nursing interventions. For example, interventions for acute pain related to physical trauma require pharmacological intervention, whereas acute pain related to natural childbirth processes is sometimes managed more appropriately with nonpharmacological interventions such as controlled breathing techniques.

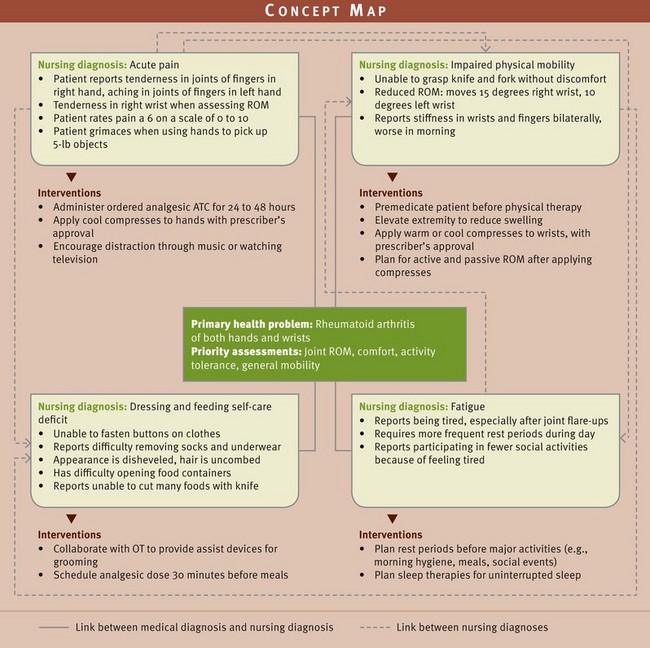

Your assessment often directs you to diagnoses other than that of acute or chronic pain. The extent to which pain affects a patient’s function and general state of health determines whether other nursing diagnoses are relevant. For example, your assessment reveals that a patient has pain of the hands and shoulders as a result of crippling arthritis for over 3 years. As a result the patient is unable to remove or fasten necessary items of clothing. The nursing diagnoses for this patient are dressing/grooming self-care deficit and chronic pain. The diagnosis of self-care deficit requires involvement by members of the interdisciplinary health care team to provide the patient with assistive devices for performing self-care. Examples of other diagnoses that are applicable to patients experiencing pain include the following:

Planning

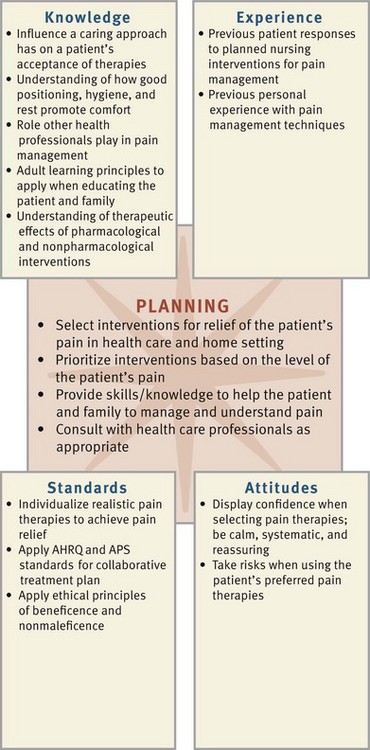

During the planning step of the nursing process, you synthesize information from multiple resources. Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care (see the Nursing Care Plan) integrates all that you know about the individual patient and key critical thinking elements (Fig. 43-9, p. 978). Professional standards are especially important to consider when you develop a plan of care. These standards establish evidence-based guidelines for selecting effective nursing interventions. Professional standards of care regarding pain management are available as agency policies or through professional organizations such as the American Society for Pain Management Nursing (ASPMN).

FIG. 43-9 Critical thinking model for pain management planning. AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; APS, American Pain Society.

Another effective method for planning care is a concept map. Patients who are in pain frequently have interrelated problems. As one problem gets worse, other aspects of a patient’s level of health also change. The concept map helps you determine how the nursing diagnoses are interrelated with one another and linked to the patient’s medical diagnosis. Using the example here, as you plan care for the patient with rheumatoid arthritis, note the relationships among acute pain, impaired physical mobility, dressing and feeding self-care deficit, and fatigue (Fig. 43-10). Identifying these relationships helps you develop a holistic and patient-centered plan of care.

FIG. 43-10 Concept map for Mrs. Mays. ATC, Around the clock; OT, occupational therapist; ROM, range of motion.

Goals and Outcomes

When managing pain, goals of care promote a patient’s optimal function. Determine, along with the patient, what the pain has prevented the patient from doing. Then decide on a mutually acceptable level of pain that allows return of function. An indication of the success of the plan is determined through attainment of goals and outcomes. For example, for the goal “the patient will achieve a satisfactory level of pain relief within 24 hours,” the following are possible outcomes:

Setting Priorities

When setting priorities in pain management, consider the type of pain the patient is experiencing and the effect that it has on various body functions. Work with the patient to select interventions that are appropriate. For example, if an analgesic relieves acute pain, center your attention on how the pain is affecting your patient’s activity, appetite, and sleep. In contrast, when a patient’s pain continues to be severe, preventing you from implementing other interventions, immediate pain relief is the obvious priority. Your priorities change as a patient’s pain experience changes.

Teamwork and Collaboration

A comprehensive plan includes a variety of resources for pain control. Resources available include advanced practice nurses, doctors of pharmacology (PharmDs), physical therapists, occupational therapists, and clergy. An oncology or pain clinical nurse specialist is very familiar with pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions that are most effective for chronic/persistent pain. PharmDs are knowledgeable about pharmacological treatments of pain. Physical therapists plan exercises that strengthen muscle groups and lessen pain in affected areas. Occupational therapists devise splints to support painful body parts. Clergy members help patients focus on spiritual health. It is important to involve the family in the plan of care because they often administer care in the home after discharge. If the pain-management plan is not successful in achieving the identified pain relief goal, talk with the patient’s health care provider about revising it. Consultation with a pain expert is sometimes necessary.

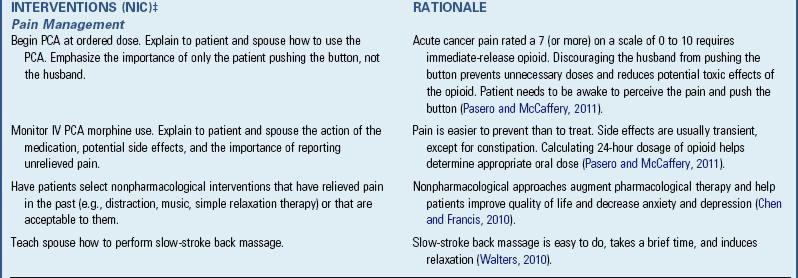

Implementation

Pain therapy requires an individualized approach, perhaps more so than any other patient problem. The nurse, patient, and frequently the family are partners in pain management. Nurses administer and monitor interventions ordered by health care providers for pain relief in addition to complementary pain-relief measures. Usually you try the least invasive or safest therapy first along with previously used successful patient remedies. If there is a question about a medical therapy, consult with the health care provider.

Health Promotion

Patients are better prepared to handle almost any situation when they understand it. The experience of pain is no exception. However, patients with moderate-to-severe pain are not always able to participate in the decision-making process until the pain is controlled at an acceptable level. Once you accomplish this, you are able to begin teaching.

Because pain affects physical and mental functioning, holistic health approaches are important interventions for maintaining wellness. Holistic health is an ongoing state of wellness that involves taking care of the physical self, expressing emotions appropriately and effectively, using the mind constructively, being creatively involved with others, and becoming aware of higher levels of consciousness (American Holistic Health Association, 2007). The concept of holistic health parallels the values of nursing in maintaining the integrity of the whole person.

Patients actively participate in their own well-being whenever possible. Common holistic health approaches include wellness education, regular exercise, rest, attention to good hygiene practices and nutrition, and management of interpersonal relationships. When a person develops pain, you can offer nonpharmacological and pharmacological strategies. Several of the nonpharmacological interventions are nurse initiated.

Nonpharmacological Pain-Relief Interventions: A number of nonpharmacological interventions lessen pain; however, they are to be used with, and not in place of, pharmacological measures (Gruener and Lande, 2006; Hughes, 2008). Nonpharmacological interventions include cognitive-behavioral and physical approaches. Cognitive-behavioral interventions change patients’ perceptions of pain, alter pain behavior, and provide patients with a greater sense of control. Distraction, prayer, relaxation, guided imagery, music, and biofeedback are examples. Physical approaches aim to provide pain relief, correct physical dysfunction, alter physiological responses, and reduce fears associated with pain-related immobility. Chiropractic therapy and acupuncture/acupressure therapy are examples (see Chapter 32). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies such as therapeutic touch also help to alleviate pain in some patients. The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research guidelines for acute pain management (AHCPR, 1992) cite nonpharmacological interventions to be appropriate for patients who meet the following criteria:

• Find such interventions appealing

• Possibly benefit from avoiding or reducing drug therapy

• Are likely to experience and need to cope with a prolonged interval of postoperative pain

• Have incomplete pain relief after use of pharmacological interventions

Relaxation and Guided Imagery: Relaxation and guided imagery allow patients to alter affective-motivational and cognitive pain perception. Relaxation is mental and physical freedom from tension or stress that provides individuals a sense of self-control. You use relaxation techniques at any phase of health or illness. Physiological and behavioral changes associated with relaxation include the following: decreased pulse, blood pressure, and respirations; heightened awareness; decreased oxygen consumption; a sense of peace; and decreased muscle tension and metabolic rate. Relaxation techniques include meditation, yoga, Zen, guided imagery, and progressive relaxation exercises (see Chapter 32). For effective relaxation, teach techniques only when a patient is not distracted by acute discomfort. Sometimes you need to use a combination of these techniques to achieve optimal pain relief. With practice the patient performs relaxation exercises independently.

Distraction: The reticular activating system inhibits painful stimuli if a person receives sufficient or excessive sensory input. With sufficient sensory stimuli, a person ignores or becomes unaware of pain. Persons who are bored or in isolation have only their pain to think about and thus perceive it more acutely. Distraction directs a patient’s attention to something other than pain and thus reduces awareness of it. One disadvantage of distraction is that, if it works, health care providers or family members question the existence or severity of the pain. Distraction works best for short, intense pain lasting a few minutes such as during an invasive procedure or while waiting for an analgesic to work. Use activities enjoyed by the patient as distractions (e.g., singing, praying, listening to music, humor or laughter therapy, playing games).

Music: Music treats acute or chronic pain, stress, anxiety, and depression (Allred et al., 2010). It diverts a person’s attention away from the pain and creates a relaxation response. Music therapy uses all kinds of music. It is important to let patients select the type of music they prefer. Music produces an altered state of consciousness through sound, silence, space, and time. Therapeutic sessions usually last 20 to 30 minutes (Hughes, 2008). Patients use earphones to enhance their concentration on the music. This allows patients to adjust the volume of the music without interrupting other patients or staff. Evidence shows that music decreases the use of analgesics in some postoperative patients (Engwall and Duppils, 2009).

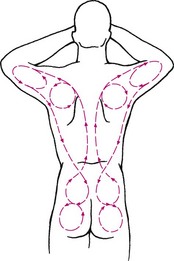

Cutaneous Stimulation: Stimulation of the skin helps relieve pain. A massage, warm bath, ice bag, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) stimulate the skin to reduce pain perception (Pain Management Center Staff, 2002). How cutaneous stimulation works is unclear. One suggestion is that it causes release of endorphins, thus blocking the transmission of painful stimuli. The gate-control theory suggests that cutaneous stimulation activates larger, faster-transmitting A-beta sensory nerve fibers. This closes the gate, thus decreasing pain transmission through small-diameter C fibers (Melzack and Wall, 1965).

Cutaneous stimulation gives patients and families some control over pain symptoms and treatment in the home. Using it properly helps to reduce muscle tension, resulting in less pain. When using cutaneous stimulation, eliminate sources of environmental noise, help the patient to assume a comfortable position, and explain the purpose of the therapy. Do not use it directly on sensitive skin areas (e.g., burns, bruises, skin rashes, inflammation, and underlying bone fractures).

Massage is effective for producing physical and mental relaxation, reducing pain, and enhancing the effectiveness of pain medication. Massaging the back, shoulders, hands, and/or feet for 3 to 5 minutes relaxes muscles and promotes sleep and comfort. Cutshall et al. (2010) reported a significant decrease in pain, anxiety, and tension in patients with cardiac problems who received a 20-minute massage. In older adults slow back massage and a 20-minute hand massage improved pain, anxiety, tension, and insomnia (Harris and Richards, 2010). Massages communicate caring and are easy for family members or other health care personnel to learn (Box 43-11).

Cold and heat applications (see Chapter 48) relieve pain and promote healing. The selection of heat versus cold interventions varies with patients’ conditions (McCarberg and O’Connor, 2004). For example, moist heat helps to relieve the pain from a tension headache, and cold applications reduce the acute pain from inflamed joints. When using any form of heat or cold application, instruct the patient to avoid injury to the skin by checking the temperature and not applying cold or heat directly to the skin. Especially at risk are patients with spinal cord or other neurological disorders, older adults, and patients who are confused.

Cold therapies are particularly effective for pain relief. Ice massage involves the use of a large ice cube or a small paper cup filled with water and frozen (water rises out of the cup as it freezes to create a smooth surface of ice for massage). A nurse or the patient applies the ice with firm pressure to the skin, which is covered with a lightweight cloth. Then you use a slow, steady, circular massage over the area. You apply cold near the pain site, on the opposite side of the body corresponding to the pain site, or on a site located between the brain and the pain site. Each patient responds differently to the site of application. Application near the actual site of pain tends to work best. A patient feels cold, burning, and aching sensations and numbness. When numbness occurs, remove the ice for usually 5 to 10 minutes. Cold is effective for tooth or mouth pain when you place the ice on the web of the hand between the thumb and index finger. This point on the hand is an acupressure point that influences nerve pathways to the face and head. Cold applications are also effective before invasive needle punctures.

Heat application is more effective for some patients. You use heating pads, warm compresses, or commercial pillows that are warmed in the microwave. Teach patients to check the temperature of the compress and not to lie on the heating element, because burning can occur.

Another form of cutaneous stimulation is transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), involving stimulation of the skin with a mild electrical current passed through external electrodes (Melzack and Wall, 2003). The therapy requires an order from a health care provider. The TENS unit consists of a battery-powered transmitter, lead wires, and electrodes. Place the electrodes directly over or near the site of pain. Remove any hair or skin preparations before attaching the electrodes. The patient turns the transmitter on when feeling pain. This creates a buzzing or tingling sensation. The patient adjusts the intensity and quality of skin stimulation and applies the tingling sensation until pain relief occurs. TENS is effective for postsurgical and procedural pain control.

Herbals: Many patients use herbals such as echinacea, ginseng, ginkgo biloba, and garlic supplements despite a lack of evidence supporting their use in pain relief (Wirth et al., 2005). Herbals often interact with prescribed analgesics; thus ask patients to report all substances they take to relieve pain (Yoon and Schaffer, 2006) (see Chapter 32).

Reducing Pain Perception: One simple way to promote comfort is to remove or prevent painful stimuli (Box 43-12). This is especially important for patients who are immobilized or have difficulty expressing themselves. For example, your patient becomes constipated and has abdominal distention and cramping. As the nurse you intervene to ensure that the normal elimination process continues: increasing fluids, ambulating the patient, and/or requesting stool softeners or laxatives. Another example involves reducing pain perception in the way you perform procedures. Always consider the patient’s condition, aspects of the procedure that are uncomfortable, and techniques to avoid causing pain. In a patient with severe arthritic knee pain who has severe discomfort during any extreme flexion of the knee, take precautions before walking the patient to the bathroom. Use an elevated toilet seat to allow the patient to sit and rise with minimal discomfort.

Acute Care

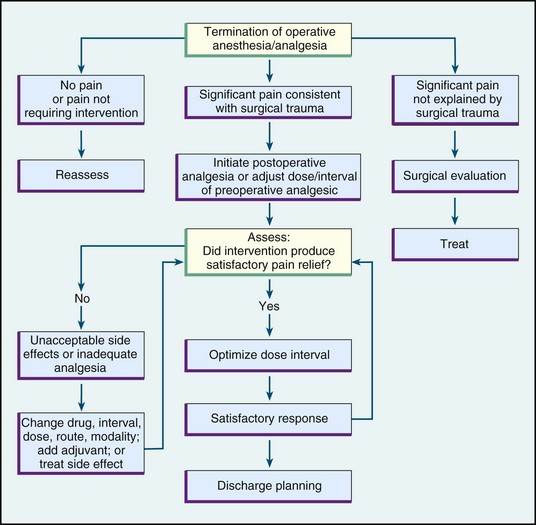

Acute Pain Management: Nurses often care for patients who have acute pain resulting from invasive procedures (e.g., surgery) or trauma. The AHCPR established a pain treatment flow chart in 1992 that is still used today (Fig. 43-11) for treatment of postoperative pain and pain from medical procedures and trauma. This systematic approach ensures quick caregiver response to patient discomfort. The key to success is ongoing evaluation of interventions: Does the patient feel relief? Are there any unacceptable side effects from the medications? It is the responsibility of the health care team to collaborate to find the combination of therapy that works best for a patient.

FIG. 43-11 Pain treatment flow chart: postoperative phase. (From Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: Acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma, Clinical Practice Guideline, AHCPR Pub No. 92-0032, Rockville, Md, 1992, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services.)

Pharmacological Pain-Relief Interventions: Many pharmacological agents are available to provide pain relief. A nurse’s judgment in the use and management of analgesics helps ensure the best pain relief possible. Unfortunately the ideal analgesic has yet to be developed.

Analgesics: Analgesics are the most common and effective method of pain relief. However, health care providers and nurses still tend to undertreat patients because of incorrect drug information, concerns about addiction, anxiety over errors in using opioid analgesics, and administration of excessive medication. You need to understand the drugs available for pain relief and their pharmacological effects.

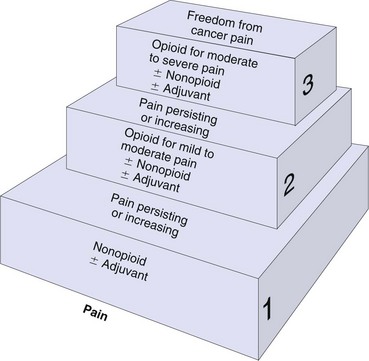

There are three types of analgesics: (1) nonopioids, including acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); (2) opioids (traditionally called narcotics); and (3) adjuvants, a variety of medications that enhance analgesics or have analgesic properties that were originally unknown (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is considered one of the most tolerated and safest analgesics available. It has no antiinflammatory effects, and its action is unknown. Its major adverse effect is hepatotoxicity. It is in a variety of over-the-counter (OTC) cold, flu, and allergy remedies. The maximum 24-hour dose is 4 g (the same dose limitation for aspirin). It is often combined with opioids (e.g., Percocet [oxycodone], Vicodin [hydrocodone], Lortab [hydrocodone], and Ultracet [tramadol]) because it reduces the dose of opioid needed to achieve successful pain control. You treat overdoses of acetaminophen with acetylcysteine (Mucomyst) (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

Nonselective NSAIDs such as aspirin and ibuprofen provide relief for mild-to-moderate acute intermittent pain such as the pain associated with a headache or muscle strain. Treatment of mild-to-moderate postoperative pain begins with an NSAID unless contraindicated (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). NSAIDs most likely inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins (Lehne, 2010) and thus inhibit cellular responses to inflammation. Most NSAIDs act on peripheral nerve receptors to reduce transmission of pain stimuli and inflammation. Unlike opioids, NSAIDs do not depress the central nervous system, nor do they interfere with bowel or bladder function (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). However, chronic NSAID use in the older patient is not recommended because it is associated with more frequent adverse effects (gastrointestinal bleeding and renal insufficiency). Mild-to-moderate musculoskeletal pain in older adults is effectively managed with the acetaminophen (AGS, 2002; Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Some patients with asthma or an allergy to aspirin are also allergic to other NSAIDs (Kaufman, 2010). Some NSAIDs are available over-the-counter (OTC); thus advise patients to discuss the use of OTC NSAIDs to manage pain with their health care provider (D’Arcy, 2006).

Current evidence shows nonselective NSAIDs are safe when taken for short periods. Some patients who took selective COX-2 inhibitors for longer periods experienced heart attacks and strokes; thus Celebrex is the only selective COX-2 inhibitor currently available. The rest are no longer available on the market. Celebrex is not to be used in patients with a sulfa allergy.

Opioid or opioid-like analgesics are generally prescribed for moderate-to-severe pain. These analgesics act on higher centers of the brain and spinal cord by binding with opiate receptors to modify perceptions of pain. A rare adverse effect of opioids in opioid-naive patients is respiratory depression. Respiratory depression is only clinically significant if there is a decrease in the rate and depth of respirations from the patient’s baseline assessment (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Patients who are breathing deeply rarely have clinical respiratory depression. Sedation, another adverse effect of opioids, always occurs before respiratory depression. Thus closely monitor for sedation in opioid-naive patients (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

If a patient experiences respiratory depression, administer naloxone (Narcan) (0.4 mg diluted with 9 mL saline) intravenous push (IVP) at a rate of 0.5 mL every 2 minutes until the respiratory rate is greater than 8 breaths/min with good depth. Administering naloxone faster than recommended possibly causes severe pain and serious complications (Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Reassess patients who receive naloxone every 15 minutes for 2 hours following drug administration because its duration is less than that of the opioid and respiratory depression sometimes returns.

Additional adverse effects of opioids include nausea, vomiting, constipation, itching, urinary retention, myoclonus, and altered mental processes (Ersek et al., 2004). Except for constipation, these side effects usually stop once a patient receives an opioid around the clock (ATC) for 4 to 10 days. Consider patients to be opioid naive until this point and opioid tolerant after about a week of ATC opioid dosing.

One way to maximize pain relief while potentially decreasing drug use is to administer analgesics on an ATC rather than a prn basis. The American Pain Society (APS, 2003) supports ATC administration if pain is anticipated for the majority of the day.

According to the American Geriatrics Society (AGS, 2002), opioids are probably not used enough with older persons. The AGS suggests a “start-low” (dose) and “go-slow” (upward dose titration) philosophy. Furthermore, do not use meperidine in older adults (AGS, 2002; Pasero and McCaffery, 2011). Meperidine (Demerol) is not recommended as an analgesic at any age because of its toxic metabolite, normeperidine, which causes seizures (APS, 2003; Pasero and McCaffery, 2011).

The proper use of analgesics requires careful assessment and critical thinking in the application of pharmacological principles and logic (Box 43-13). A person’s response to an analgesic is highly individualized. If the pain is caused by inflammation, an NSAID is sometimes as effective as, or more effective than, an opioid. An orally administered analgesic usually has a longer onset and duration of action than an injectable form. In addition, controlled- or extended-release opioid formulations (morphine [MS Contin, Kadian, Avinza], oxycodone [OxyContin], and methadone) are available for administration every 8 to 12 hours ATC; they are not ordered prn.