Implementing Nursing Care

• Explain the relationship of implementation to the nursing diagnostic process.

• Describe the association between critical thinking and selecting nursing interventions.

• Discuss the differences between protocols and standing orders.

• Identify preparatory activities to use before implementation.

• Discuss the value of the Nursing Interventions Classification system in documenting nursing care.

• Discuss the steps for revising a plan of care before performing implementation.

• Define the three implementation skills.

• Describe and compare direct and indirect nursing interventions.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

You first met Tonya and Mr. Jacobs in Chapter 16. The two have collaborated during the nursing process to develop a relevant and appropriate plan of care. During implementation Tonya works with fellow health care colleagues and Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs to provide the safest and most effective nursing interventions for the patient’s health care problems. Implementation is circular, like all steps of the nursing process. This means that, during the course of Mr. Jacobs’ hospitalization, as his clinical condition changes Tonya reassesses the status of existing nursing diagnoses, confirms that these diagnoses are still appropriate, evaluates the patient’s responses to planned interventions (see Chapter 20), and continues to deliver interventions in a timely and competent manner. Critical thinking, which includes good clinical decision making, is important for the successful implementation of nursing interventions.

Implementation, the fourth step of the nursing process, formally begins after the nurse develops a plan of care. With a care plan based on clear and relevant nursing diagnoses, the nurse initiates interventions that are designed to achieve the goals and expected outcomes needed to support or improve the patient’s health status. A nursing intervention is any treatment based on clinical judgment and knowledge that a nurse performs to enhance patient outcomes (Bulechek et al., 2008). Ideally the interventions a nurse uses are evidenced based (see Chapter 5), providing the most current, up-to-date, and effective approaches for managing patient problems. Interventions include direct and indirect care measures aimed at individuals, families, and/or the community.

Direct care interventions are treatments performed through interactions with patients (Bulechek et al., 2008). For example, a patient receives direct intervention in the form of medication administration, insertion of an intravenous (IV) infusion, or counseling during a time of grief. Indirect care interventions are treatments performed away from the patient but on behalf of the patient or group of patients (Bulechek et al., 2008). For example, indirect care measures include actions for managing the patient’s environment (e.g., safety and infection control), documentation, and interdisciplinary collaboration. Both direct and indirect care measures fall under the intervention categories described in Chapter 18: nurse-initiated, physician-initiated, and collaborative. For example, the direct intervention of patient education is a nurse-initiated intervention. The indirect intervention of consultation is a collaborative intervention.

Benner (1984) defined the domains of nursing practice, which help to explain the nature and intent of the many ways nurses intervene for patients (Box 19-1). These domains are current today. The extent of organizational and work role competencies has become more complex; thus it is important that the focus of implementation always be the patient. Nursing is an art and a science. It is not simply a task-based profession. Thus you learn to intervene for a patient within the context of his or her unique situation. Examples of factors to consider during intervention follow. Who is the patient? What does this illness mean to the patient and his or her family? What clinical situation requires you to intervene? How does the patient perceive the interventions that you will deliver? Will any cultural considerations influence your approach? In what way do you best support or show caring as you intervene? The answers to these questions enable you to deliver care compassionately and effectively with the best outcomes for your patients.

Critical Thinking in Implementation

The delivery of nursing interventions is a complex decision-making process that involves critical thinking. The context in which you deliver care to each patient and the many interventions required result in decision-making approaches for each clinical situation. Critical thinking is necessary to consider the complexity of interventions, including the number of alternative approaches and the amount of time available to act.

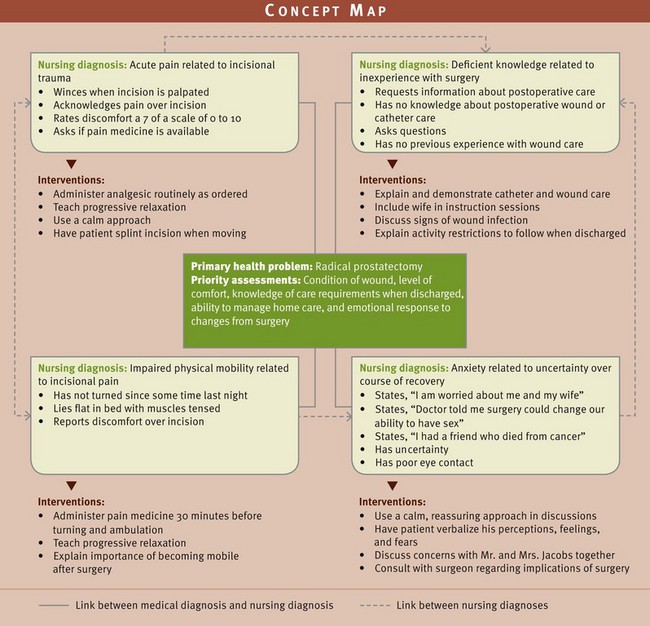

Tonya indentified four relevant nursing diagnoses for Mr. Jacobs: acute pain related to incisional trauma, deficient knowledge regarding postoperative recovery related to inexperience with surgery, impaired physical mobility related to incisional pain, and anxiety related to uncertainty over the course of recovery. The diagnoses are interrelated, and sometimes a planned intervention (e.g., administering pain medication) treats or modifies more than one of the patient’s health problems (pain and impaired physical mobility). Tonya applies critical thinking and uses her time with Mr. Jacobs wisely by anticipating his priorities, applying the knowledge she has about his problems and the interventions planned, and implementing care strategies skillfully.

Before implementing a planned intervention, use critical thinking to confirm whether the intervention is correct and still appropriate for the patient’s clinical situation. Even though you have planned a set of interventions for a patient, you have to exercise good judgment and decision making before actually delivering each intervention. Always think before you act. Patients’ conditions often change minute to minute. You need to consider the scheduling of activities on a nursing unit, which often dictates when and how to complete an intervention. Thus many factors influence your decision on how and when to intervene. You are responsible for having the necessary knowledge and clinical competency to perform interventions for your patients safely and effectively. Some tips for making decisions during implementation follow.

• Review the set of all possible nursing interventions for the patient’s problem (e.g., for Mr. Jacobs’ pain Tonya considers analgesic administration, positioning and splinting, progressive relaxation, and other nonpharmacological approaches).

• Review all possible consequences associated with each possible nursing action (e.g., Tonya considers that the analgesic will either relieve pain; have little or insufficient effect; or cause an adverse reaction, including sedating the patient and increasing the risk of falling).

• Determine the probability of all possible consequences (e.g., if Mr. Jacobs’ pain has decreased with analgesia and positioning in the morning and there have been no side effects, it is unlikely that adverse reactions will occur, and the intervention will be successful; however, if the patient continues to remain highly anxious, his pain may not be relieved, and Tonya needs to consider an alternative).

• Make a judgment of the value of the consequence to the patient (e.g., if the administration of an analgesic is effective, Mr. Jacobs will likely become less anxious and more responsive to postoperative instruction and counseling about his anxiety).

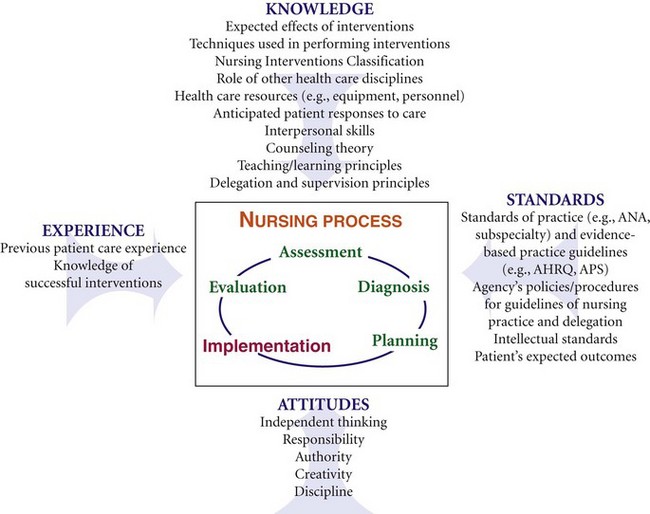

The selection and performance of nursing interventions for a patient are part of clinical decision making. The critical thinking model described in Chapter 15 provides a framework for how to make decisions when implementing nursing care (Fig. 19-1). You learn how to implement nursing care using appropriate knowledge. For example, as you proceed with an intervention, you consider what you know about the purpose of the intervention, the steps in performing the intervention correctly, the medical condition of the patient, and his or her expected response. It is important to prepare well before first caring for any patient. With experience you become more proficient in anticipating what to expect in a given clinical situation and how to modify your approach. As you gain clinical experience, you are able to consider which interventions worked previously, which have not, and why. It also helps to know the clinical standards of practice for your agency. For example, one hospital has a different set of standards for patient education than another. The standards of practice offer guidelines for selection of interventions and their frequency and whether you are able to delegate the procedures.

FIG. 19-1 Critical thinking and the process of implementing care. AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research Quality; ANA, American Nurses Association; APS, American Pain Society.

As you perform a nursing intervention, apply intellectual standards, which are the guidelines for rational thought and responsible action. For example, before Tonya begins to teach Mr. Jacobs, she considers how to make her instructions relevant, clear, logical, and complete to promote patient learning. She knows that it will be helpful to involve Mrs. Jacobs so any instruction is relevant to their home situation. Using simple, clear explanations and repeated instructions promote learning for Mr. Jacobs, who is inexperienced with postoperative recovery. Making an instructional DVD on wound care available to the family is a valuable resource for repeated viewing in the home.

As a critical thinker, apply critical thinking attitudes when you intervene. For example, show confidence in performing an intervention. When you are unsure of how to perform a procedure, be responsible in seeking assistance from others. Confidence in performing interventions builds trust with patients. Creativity and self-discipline are attitudes that guide you in reviewing, modifying, and implementing interventions. As a beginning nursing student, seek out supervision from instructors or experienced nurses to guide you in the decision-making process for implementation.

Standard Nursing Interventions

Health care settings present various ways for nurses to create and individualize a patient’s plan of care. Each plan of care is totally unique to that patient, with interventions individualized on the basis of his or her specific health problems. In certain situations a nurse develops the plan on the basis of personal knowledge and clinical experience. However, systems are available that provide standardized interventions for nurses to use in their plan of care. Many patients have common health care problems; thus standardized interventions for these health problems make it quicker and easier for nurses to intervene. More important, if the standards are evidence based, the nurse is more likely to deliver the most clinically effective interventions to improve patient outcomes (see Chapter 5). Standardized interventions most often set a level of clinical excellence for practice. Nurse- and physician-initiated standardized interventions are available in the form of clinical guidelines or protocols, preprinted (standing) orders, and Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) interventions. At a professional level the American Nurses Association (ANA) defines standards of professional nursing practice, which include standards for the implementation step of the nursing process. These standards are authoritative statements of the duties that all registered nurses are expected to perform competently, regardless of role, patient population they serve, or specialty (ANA, 2010) (see Chapter 1).

Clinical Practice Guidelines and Protocols

A clinical practice guideline or protocol is a systematically developed set of statements that helps nurses, physicians, and other health care providers make decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical situations (Manchikanti et al., 2010). A guideline guides interventions for specific health care problems or conditions such as low back pain, dizziness, or deep vein thrombosis. The guideline is developed on the basis of an authoritative examination of current scientific evidence (National Guideline Clearinghouse [NGC], 2010). Guidelines are now seen as key tools for improving the quality of health care and bridging the gap between the growth of research findings and actual clinical practice (Rosenbrand et al., 2008).

Clinicians within a health care agency sometimes choose to review the scientific literature and their own standard of practice to develop guidelines and protocols in an effort to improve their standard of care. For example, a hospital develops a rapid-assessment protocol to improve the identification and early treatment of patients suspected of having a stroke. However, clinical practice guidelines have already been developed by national health groups such as the National Institutes of Health and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. These guidelines are readily available to any clinician or health care institution that wishes to adopt evidence-based guidelines in the care of patients with specific health problems. One valuable source for nursing practice guidelines is the Gerontological Nursing Interventions Research Center (GNIRC) at the University of Iowa. The center has numerous clinical guidelines, including ones for acute confusion and delirium, acute pain management, and fall prevention for older adults (GNIRC, 2010).

Advanced practice nurses who provide primary care for patients in outpatient settings frequently follow diagnostic and treatment protocols. In such a setting nurses assess the patient and identify abnormalities. The protocol outlines the conditions that nurses are permitted to treat such as controlled hypertension and the types of treatment that they are permitted to administer such as antihypertensive medications. In acute care settings it is common to find clinical protocols that outline independent nursing interventions for specific conditions. Examples include protocols for admission and discharge, pressure ulcer care, and incontinence management. Protocols are also used in interdisciplinary settings for diagnostic testing and physical, occupational, and speech therapies.

Standing Orders

A standing order is a preprinted document containing orders for the conduct of routine therapies, monitoring guidelines, and/or diagnostic procedures for specific patients with identified clinical problems. A standing order directs the conduct of patient care in a specific clinical setting. Licensed prescribing health care providers in charge of care at the time of implementation approve and sign standing orders. These orders are common in critical care settings and other specialized practice settings where patients’ needs change rapidly and require immediate attention. An example of such a standing order is one specifying certain medications such as lidocaine or propranolol for an irregular heart rhythm. After assessing the patient and identifying the irregular rhythm, the critical care nurse gives the specified medication without first notifying the physician. The physician’s initial standing order covers the nurse’s action. After completing a standing order, the nurse notifies the physician. Standing orders are common in the community health setting, where the nurse faces situations that do not permit immediate contact with a health care provider. Standing orders give the nurse legal protection to intervene appropriately in the patient’s best interest.

NIC Interventions

The NIC system developed by the University of Iowa helps to differentiate nursing practice from that of other health care professionals (Box 19-2). The NIC interventions offer a level of standardization to enhance communication of nursing care across settings and to compare outcomes. By using NIC nurses learn the common interventions recommended for various NANDA International nursing diagnoses. Nurses also learn the numerous care activities for each NIC intervention. Recently the NIC interventions have been used for work complexity assessment, a process that helps nurses identify interventions performed on a routine basis for their patient populations (Scherb and Weydt, 2009). Chapter 18 describes the NIC system in more detail.

Standards of Practice

The ANA Standards of Professional Nursing Practice (ANA, 2010) are to be used as evidence of the standard of care that registered nurses provide their patients (see Chapter 1). The standards are formally reviewed on a regular basis. The newest standards include competencies for establishing professional and caring relationships, using evidence-based interventions and technologies, providing holistic care across the life span to diverse groups, and using community resources and systems. In addition, the standards emphasize implementing a timely plan following patient safety goals (ANA, 2010).

Implementation Process

Preparation for implementation ensures efficient, safe, and effective nursing care. Five preparatory activities include reassessing the patient, reviewing and revising the existing nursing care plan, organizing resources and care delivery, anticipating and preventing complications, and implementing nursing interventions.

Tonya returns to Mr. Jacobs’ room 30 minutes after administering a dose of IV morphine for his incisional pain. She notices that he is more relaxed and turning a bit on his own. She asks him to rate his pain on a scale of 0 to 10, and he responds that it is now a 3. With the pain currently under control, Tonya decides to get the patient up in a chair to begin increasing his activity level. While Mr. Jacobs is in the chair, Tonya gets the teaching booklets she wants to use to prepare the patient for wound and catheter care in the home. She knows that Mrs. Jacobs is due to arrive at any time; thus she plans to include her in the discussion. Tonya also knows that this is Mr. Jacobs’ first time up in the chair; thus she anticipates monitoring him closely and judging if he is alert and comfortable enough to begin the planned instruction.

Reassessing the Patient

Assessment is a continuous process that occurs each time you interact with a patient. When you collect new data about a patient, you sometimes identify a new nursing diagnosis or determine the need to modify the care plan. During the initial phase of implementation reassess the patient. The reassessment often focuses on one primary nursing diagnosis, or one dimension of the patient such as level of comfort, or one system such as the cardiovascular system. The reassessment helps you decide if the proposed nursing actions are still appropriate for the patient’s level of wellness. Reassessment is not the evaluation of care (see Chapter 20), but it is the gathering of additional information to ensure that the plan of care is appropriate. For example, Tonya plans to talk with Mr. Jacobs about surgery and what to expect during recovery. However, she learns from Mr. Jacobs that Mrs. Jacobs’ visit has been delayed until lunchtime. She knows that Mrs. Jacobs is an important resource for Mr. Jacobs’ recovery, but she decides to get Mr. Jacobs up in a chair and focus on how he tolerates the activity anyway. Pain control is still a priority. Tonya will help Mr. Jacobs back to bed after about 30 minutes, allow him to rest until lunchtime, and then begin her instruction.

Reviewing and Revising the Existing Nursing Care Plan

After reassessing a patient, review the care plan and compare assessment data to validate the nursing diagnoses and determine whether the nursing interventions remain the most appropriate for the clinical situation. If the patient’s status has changed and the nursing diagnosis and related nursing interventions are no longer appropriate, modify the nursing care plan. An out-of-date or incorrect care plan compromises the quality of nursing care. Review and modification enable you to provide timely nursing interventions to best meet the patient’s needs.

After reviewing the care plan, Tonya made a few revisions to Mr. Jacobs’ concept map (Fig. 19-2). Tonya notices that eye contact with Mr. Jacobs has improved; trust is building. Mr. Jacobs’ pain has also lessened. She modifies her plan for reducing anxiety by planning a discussion with Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs together and consulting with the surgeon.

Modification of an existing written care plan includes four steps:

1. Revise data in the assessment column to reflect the patient’s current status. Date any new data to inform other members of the health care team of the time that the change occurred.

2. Revise the nursing diagnoses. Delete nursing diagnoses that are no longer relevant and add and date any new diagnoses. It is necessary to revise related factors and the patient’s goals, outcomes, and priorities. Date any revisions.

3. Revise specific interventions that correspond to the new nursing diagnoses and goals. Revisions need to reflect the patient’s present status.

4. Choose the method of evaluation for determining whether you achieved patient outcomes.

Organizing Resources and Care Delivery

The resources of a facility include equipment and skilled personnel. Organization of equipment and personnel makes timely, efficient, skilled patient care possible (see Chapter 21). It is also important to prepare the environment and patient for a nursing intervention.

Equipment

Most nursing procedures require some equipment or supplies. Before performing an intervention, decide which supplies you need and determine their availability. Is the equipment in working order to ensure safe use, and do you know how to use it? Place supplies in a convenient location to provide easy access during a procedure. Keep extra supplies available in case of errors or mishaps, but do not open them unless you need them. This controls health care costs. After a procedure return any unopened supplies to storage areas.

Personnel

Nursing care delivery models vary among facilities (see Chapter 21). The model by which nursing is organized determines how nursing personnel deliver patient care. For example, a registered nurse’s (RN’s) accountabilities differ in a team nursing model from those in a primary nursing model. A primary nurse is accountable for the nursing care that a patient receives during his or her length of stay or course of visits. A team nurse is accountable for the care that a patient receives for a specific shift in which the nurse works. As a nurse you are responsible for deciding whether to perform an intervention or delegate it to another member of the nursing team. Your ongoing assessment of a patient, and not the intervention alone, directs the decision about delegation.

For example, Tonya knows that nursing assistive personnel (NAP) can competently assist patients to ambulate. However, she has learned that patients who transfer to a chair or ambulate the first time after surgery are often less stable; the NAP should not be the one to assess the patient’s response. She decides to personally help Mr. Jacobs get up and into a chair to evaluate his response. Tonya thus redirects the NAP to perform more suitable care activities such as helping Tonya make Mr. Jacobs’ bed or assisting a different patient with oral hygiene.

Nursing staff work together as patients’ needs demand it. If a patient makes a request such as use of a bedpan or assistance in feeding, help the patient if you have time rather than trying to find the NAP who is in a different room. Nursing staff respect colleagues who show initiative; collaborate together; and communicate with one another on an ongoing, reciprocal basis as patients’ needs change (Potter et al., 2010). When interventions are complex or physically difficult, you probably need assistance from colleagues. For example, you and the NAP more effectively change a dressing in a large gaping wound when you apply the dressing and the NAP assists with patient positioning and handing off of supplies.

Environment

A patient’s care environment needs to be safe and conducive to implementing therapies. Patient safety is your first concern. If the patient has sensory deficits, physical disabilities, or an alteration in level of consciousness, arrange the environment to prevent injury. For example, provide a patient’s assist devices (e.g., walker or eyeglasses), rearrange furniture and equipment when ambulating a patient, or make sure that the water temperature is not too warm before a bath. The patient benefits most from nursing interventions when surroundings are compatible with care activities. When you need to expose a patient’s body parts, do so privately by closing room doors or curtains because the patient will then be more relaxed. Ask visitors to leave as you complete care. Reduce distractions to enhance a patient’s learning opportunities. Make sure that lighting is adequate to perform procedures correctly.

Patient

Before you implement interventions, make sure that the patient is as physically and psychologically comfortable as possible. For example, symptoms such as nausea, dizziness, fatigue, or pain frequently interfere with a patient’s full concentration and ability to cooperate. Offer comfort measures before initiating interventions to help the patient participate more fully. If you need a patient to be alert, administer a dose of pain medication strong enough to relieve discomfort but not to impair mental faculties (e.g., ability to follow instruction, reasoning, and communication). If a patient is fatigued, delay ambulation or transfer to a chair until after he or she has had a chance to rest.

Even if symptoms are not a factor, make the patient physically comfortable during interventions. Start any intervention by controlling environmental factors, taking care of physical needs (e.g., elimination), avoiding interruptions, and positioning the patient correctly. Also consider the patient’s level of endurance and plan only the amount of activity that he or she is able to tolerate comfortably.

Awareness of the patient’s psychosocial needs helps you create a favorable emotional climate. Some patients feel reassured by having a significant other present to lend encouragement and moral support. Other strategies include planning sufficient time or multiple opportunities for the patient to work through and ventilate feelings and anxieties. Adequate preparation allows the patient to obtain maximal benefit from each intervention.

Anticipating and Preventing Complications

Risks to patients come from both illness and treatment. As a nurse, look for and recognize these risks, adapt your choice of interventions to the situation, evaluate the relative benefit of the treatment versus the risk, and take risk-prevention measures. Many conditions place the patient at risk for complications. For example, the patient with preexisting left-sided paralysis following a stroke 2 years earlier is at risk for developing a pressure ulcer following orthopedic surgery because it requires traction and bed rest. A patient with obesity and diabetes who has major abdominal surgery is at risk for poor wound healing and developing the complications of a fistula or dehiscence. Nurses are often the first ones to detect and document changes in a patient’s condition. In her classic research Benner (1984) notes that expert nurses learn to anticipate breakdown and deterioration of patients even before confirming diagnostic signs develop.

Your knowledge of pathophysiology and experience with previous patients help in identifying the risk of complications that can occur. A thorough assessment reveals the level of a patient’s current risk. The evidence or scientific rationales for how certain interventions (e.g., pressure-relief devices, repositioning, or wound care) prevent or minimize complications help you select the preventive measures that likely are most useful. For example, if a patient who is obese has uncontrolled postoperative pain, the risk for pressure ulcer development increases because the patient is unwilling or unable to change position frequently. The nurse anticipates when the patient’s pain will be aggravated, administers ordered analgesics, and then positions the patient to remove pressure on the skin and underlying tissues. If the patient continues to have difficulty turning or repositioning, the nurse selects a pressure-relief device to place on the patient’s bed.

Some nursing procedures pose risks. Be aware of potential complications and take precautionary measures. For example, the patient who has a feeding tube is at risk for aspiration. Position the patient in high-Fowler’s position and check the tube position before administering a feeding.

Identifying Areas of Assistance

Certain nursing situations require you to obtain assistance by seeking additional personnel, knowledge, and/or nursing skills. Before beginning care, review the plan to determine the need for assistance and the type required. Sometimes you need assistance in performing a procedure, providing comfort measures, or preparing the patient for a diagnostic test. Do not take shortcuts if assistance is not immediately available since this increases risk of injury to you and the patient. For example, when you care for a patient who is overweight and immobilized, you require additional personnel and transfer equipment to turn and position the patient safely. Be sure to determine the number of additional personnel and if you need them in advance. Discuss your need for assistance with other nurses or NAP.

You require additional knowledge and skills in situations in which you are less experienced. Because of the continual growth in health care technology, you may lack the skills to perform a procedure. When you are asked to administer a new medication, operate a new piece of equipment, or administer a procedure with which you are unfamiliar, follow these steps.

• Seek information you need to be informed about the procedure. Check the scientific literature for evidence-based information, review resource manuals and the procedure book of the agency, or consult with experts (e.g., pharmacists, clinical nurse specialists) who are familiar with the procedure.

• Collect all equipment necessary for the procedure.

• Have another nurse who has completed the procedure correctly and safely provide assistance and guidance. The assistance can come from another staff nurse, a supervisor, an educator, or a nurse specialist. Requesting assistance occurs frequently in all types of nursing practice and is a learning process that continues throughout educational experiences and into professional development. One tip is to verbalize with an instructor or staff nurse the steps you will take before actually performing the procedure to improve your confidence.

Implementation Skills

Nursing practice includes cognitive, interpersonal, and psychomotor (technical) skills. You need each type of skill to implement direct and indirect nursing interventions. You are responsible for knowing when one type of implementation skill is preferred over another and for having the necessary knowledge and skill to perform each.

Cognitive Skills

Cognitive skills involve the application of critical thinking in the nursing process. Always use good judgment and sound clinical decision making when performing any intervention. This ensures that no nursing action is automatic. Always think and anticipate so you individualize patient care appropriately. Know the rationale for therapeutic interventions and understand normal and abnormal physiological and psychological responses. In addition, know the evidence in nursing science to ensure that you deliver the most current and relevant nursing interventions. You learn to integrate different concepts and relate them to each other while recollecting facts, situations, and patients for whom you have cared previously (Di Vito-Thomas, 2005).

Tonya knows the pathophysiology of prostate cancer, the anatomy of the prostate gland and surrounding structures, and the normal mechanisms for pain. She considers each of these as she observes Mr. Jacobs, noting how the patient’s movement and position either aggravate or lessen his incisional pain. Tonya focuses on relieving Mr. Jacobs’ acute pain with an analgesic but then considers the noninvasive interventions needed to provide even greater pain relief so the patient can gain needed rest and relaxation.

Interpersonal Skills

Interpersonal skills are essential for effective nursing action. Develop a trusting relationship, express a level of caring, and communicate clearly with a patient and his or her family (see Chapter 24). Good interpersonal communication is critical for keeping patients informed, providing individualized patient teaching, and effectively supporting patients with challenging emotional needs. Proper use of interpersonal skills enables you to be perceptive of the patient’s verbal and nonverbal communication. As a member of the health care team, communicate patient problems and needs clearly, intelligently, and in a timely manner.

Psychomotor Skills

Psychomotor skills require the integration of cognitive and motor activities. For example, when giving an injection you need to understand anatomy and pharmacology (cognitive) and use good coordination and precision to administer the injection correctly (motor). With time and practice you learn to perform skills correctly, smoothly, and confidently. This is critical in establishing patient trust. You are responsible for acquiring necessary psychomotor skills through your experience in the nursing laboratory, the use of interactive instructional technology, or actual hands-on care of patients. When attempting a new skill, always assess your level of competency and obtain the necessary resources to ensure that the patient receives safe treatment.

Direct Care

Nurses provide a wide variety of direct care measures (i.e., activities that nurses perform through patient interactions). How a nurse interacts affects the success of any direct care activity. Remain sensitive to a patient’s clinical condition, values and beliefs, expectations, and cultural views. All direct care measures require competent and therefore safe practice. Show a caring approach each time you provide direct care.

Activities of Daily Living

Activities of daily living (ADLs) are activities usually performed in the course of a normal day, including ambulation, eating, dressing, bathing, and grooming (see Chapter 39). A patient’s need for assistance with ADLs is temporary, permanent, or rehabilitative. For example, a patient with impaired physical mobility because of bilateral arm casts has a temporary need for assistance. After the casts are removed, the patient gradually regains the strength and range of motion needed to perform ADLs. In contrast, a patient with an irreversible injury to the cervical spinal cord is paralyzed and has a permanent need for assistance. It is unrealistic to plan rehabilitation with a goal of becoming independent with ADLs for this patient. Instead the patient learns new ways to perform ADLs independently through rehabilitation. Occupational and physical therapists play a key role in rehabilitation to restore ADL function.

When your assessment reveals that a patient is experiencing fatigue, a limitation in mobility, confusion, and pain, assistance with ADLs is likely. For example, a patient who experiences shortness of breath avoids eating because of the associated fatigue. Help the patient by setting up meals and offering to cut up food and plan for more frequent, small meals to maintain the patient’s nutrition. Assistance with ADLs ranges from partial assistance to complete care. Remember to always respect the patient’s wishes and determine his or her preferences. Patients from some cultures prefer receiving assistance with ADLs from family members. As long as a patient is stable and alert, it is appropriate to allow family to assist with care. Most patients want to remain independent in meeting their basic needs. Allow the patient to participate to the level that he or she is able. Involving the patient in planning the timing and types of interventions boosts the patient’s self-esteem and willingness to become more independent.

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Illness or disability sometimes alters a patient’s ability to be independent in society. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) include such skills as shopping, preparing meals, house cleaning, writing checks, and taking medications. Nurses within the home care and community health setting frequently help patients adapt ways to perform IADLs. Occupational therapists are specially trained to know how to adapt approaches for patients to use when performing IADLs. Often family and friends are excellent resources for assisting patients. In acute care it is important for you to anticipate how a patient’s illness affects the ability to perform IADLs so you can make appropriate referrals.

Physical Care Techniques

You routinely perform a variety of physical care techniques when caring for a patient. Physical care techniques involve the safe and competent administration of nursing procedures (e.g., turning and positioning, performing invasive procedures, administering medications, and providing comfort measures). The specific knowledge and skills needed to perform these procedures are in subsequent clinical chapters of this text. Common methods for administering physical care techniques appropriately include protecting you and the patient from injury, using safe patient handling techniques, using proper infection control practices, staying organized, and following applicable practice guidelines.

To carry out a procedure you need to be knowledgeable about the procedure itself, the standard frequency, the steps, and the expected outcomes. In a hospital you perform many procedures each day, often for the first time. Before conducting a new procedure, always assess the situation and your personal competencies to determine if you need assistance, new knowledge, or new skills. Benner (1984) made an important observation about physical care techniques. Nurses always need to make varied and thoughtful adaptations when administering and monitoring patient therapies. For example, when you change a complicated dressing, you can choose from many dressing materials and cleansing solutions, and the patient’s size affects how to secure a dressing. Performing any procedure correctly requires critical thinking and thoughtful decision making.

Lifesaving Measures

A lifesaving measure is a physical care technique that you use when a patient’s physiological or psychological state is threatened (see Chapter 40). The purpose of lifesaving measures is to restore physiological or psychological homeostasis. Such measures include administering emergency medications, instituting cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intervening to protect a confused or violent patient, and obtaining immediate counseling from a crisis center for a severely anxious patient. If an inexperienced nurse faces a situation requiring emergency measures, the proper nursing actions are to stay with the patient, maintain support, and have another staff member obtain an experienced professional.

Counseling

Counseling is a direct care method that helps a patient use a problem-solving process to recognize and manage stress and facilitate interpersonal relationships. As a nurse, you counsel patients to accept actual or impending changes resulting from stress (see Chapter 37). Examples include patients who are facing terminal illness or chronic disease. Counseling involves emotional, intellectual, spiritual, and psychological support. A patient and family who need nursing counseling have normal adjustment difficulties and are upset or frustrated, but they are not necessarily psychologically disabled. A good example is the stress that a young woman faces when caring for her aging mother. Family caregivers need assistance in adjusting to the physical and emotional demands of caregiving. Sometimes they need respite (i.e., a break from providing care). The recipient of care also needs assistance in adjusting to his or her disability. Patients with psychiatric diagnoses require therapy from nurses specializing in psychiatric nursing or social workers, psychiatrists, or psychologists.

Many counseling techniques foster cognitive, behavioral, developmental, experiential, and emotional growth in patients. Most of the techniques listed in Box 19-3 require additional knowledge beyond the scope of this text. Counseling encourages individuals to examine available alternatives and decide which choices are useful and appropriate. When patients are able to examine alternatives, they develop a sense of control and are able to better manage stress.

Teaching

Teaching is an important nursing responsibility because education is key to patient-centered care (see Chapter 25). A teaching plan is essential, especially when patients are inexperienced and being asked to manage health problems they are facing for the first time. Counseling and teaching closely align. Both involve using good interpersonal skills to create a change in the patient. However, with counseling the change results in the development of new attitudes and feelings, whereas in teaching the focus of change is intellectual growth or the acquisition of new knowledge or psychomotor skills (Redman, 2005).

When you educate patients, respect the diversity of their human experiences, know their values and preferences as to how they learn, and respect their expertise with their own health management. As an educator you present health care principles, procedures, and techniques to inform patients about their health status and help them achieve self-care within their capabilities. The types of teaching topics that you address with patients are unlimited. However, be aware that teaching is also an ongoing process of keeping patients informed. Patients want to know why you do what you do. For example, incorporate into your interventions explanations of procedures, why they are being done, what the expected outcomes are, and what the patient can expect. A simple application is informing a patient about his or her IV infusion: explain what the IV fluid bag contains, how long the bag should last, the sensations the patient will feel if the IV site becomes inflamed, the fact that a small flexible catheter is in the arm, and any potential side effects of medications in the bag.

Teaching takes place in all health care settings (Fig. 19-3). As a nurse you are accountable for the quality of education you deliver. Know your patient; be aware of the cultural and social factors that influence a patient’s willingness and ability to learn. It is also important to know your patient’s health literacy level. Can he or she read directions or make calculations that sometimes are necessary with self-care skills? The teaching-learning process is an interaction between you and the learner, and it offers an organizational structure and framework for successful patient education. Don’t assume that patients understand their illness or disease. If they seem uneasy or refuse a treatment, simply ask what concerns them. This gives you the opportunity to provide further teaching and correct knowledge deficiencies.

Controlling for Adverse Reactions

An adverse reaction is a harmful or unintended effect of a medication, diagnostic test, or therapeutic intervention. Adverse reactions can possibly follow any nursing intervention; thus learn to anticipate and know which adverse reactions to expect. Nursing actions that control for adverse reactions reduce or counteract the reaction. For example, when applying a moist heat compress, you want to prevent burning the patient’s skin. First assess the condition of the area where you plan to place the compress. Following application of the compress, inspect the area every 5 minutes for any adverse reaction such as excessive reddening of the skin from the heat or skin maceration from the moisture. When completing a health care provider–directed intervention such as medication administration, you need to understand the potential side effects of the drug. After you administer the medication, evaluate the patient for any adverse effects. Also be aware of drugs that counteract the side effects. For example, a patient has an unknown hypersensitivity to penicillin and develops hives after three doses. You record the reaction, stop further administration of the drug, and consult with the physician. You then administer an ordered dose of diphenhydramine (Benadryl), an antihistamine and antipruritic medication, to reduce the allergic response and relieve the itching.

When caring for a patient who is undergoing a particular diagnostic test, you need to understand the test and any potential adverse effects. For example, a patient has not had a bowel movement in 24 hours after a barium enema. Because bowel impaction is a potential side effect of a barium enema, you increase fluid intake and instruct the patient to let nursing personnel know when a bowel movement occurs. Although adverse effects are not common, they do occur. It is important that you recognize the signs and symptoms of an adverse reaction and intervene in a timely manner.

Preventive Measures

Preventive nursing actions promote health and prevent illness to avoid the need for acute or rehabilitative health care (see Chapter 1). Changes in the health care system are leading to greater emphasis on health promotion and illness prevention. Primary prevention aimed at health promotion includes health education programs, immunizations, and physical and nutritional fitness activities. Secondary prevention focuses on people who are experiencing health problems or illnesses and who are at risk for developing complications or worsening conditions. It includes screening techniques and treating early stages of disease. Tertiary prevention involves minimizing the effects of long-term illness or disability, including rehabilitation measures.

Indirect Care

Indirect care measures include nurse actions aimed at management of the patient care environment and interdisciplinary collaborative actions that support the effectiveness of direct care interventions (Bulechek et al., 2008). Many of the measures are managerial in nature such as emergency cart maintenance and environmental and supply management (Box 19-4). Nurses spend much time in indirect and unit management activities. Communication of information about patients (e.g., change-of-shift report and consultation) is critical, ensuring that direct care activities are planned, coordinated, and performed with the proper resources. Delegation of care to NAP is another indirect care activity (see Chapter 21). When performed correctly, delegation ensures that the right care provider performs the right tasks so the nurse and NAP work most efficiently together for the patient’s benefit.

Communicating Nursing Interventions

Any intervention that you provide for a patient is communicated in a written (or electronic) and oral format. Written interventions are part of the nursing care plan (see Chapter 18) and a patient’s permanent medical record. Staff in many institutions develop interdisciplinary care plans (i.e., plans representing the contributions of all disciplines caring for a patient). After completing any nursing interventions, you document the treatment and patient’s response in the appropriate part of the record (see Chapter 26). The record entry usually includes a brief description of pertinent assessment findings, the specific intervention(s), and the patient’s response. A written record validates that you performed the procedure and provides valuable information to subsequent caregivers about the approaches needed to provide successful care.

You also communicate nursing interventions verbally to other health care professionals. Unless communication is timely and accurate, caregivers can be uninformed, interventions may be duplicated needlessly, procedures may be delayed, or tasks may be left undone. Patients can quickly tell when members of the health care team communicate inconsistent messages, indicating that no one is in charge. Nurses commonly communicate orally when conferring with colleagues, during a change of shift, transferring a patient to another unit, or discharging a patient to another health care agency. Always be clear, concise, and to the point when you communicate nursing interventions.

Delegating, Supervising, and Evaluating the Work of Other Staff Members

Depending on the system of health care delivery, the nurse who develops the care plan frequently does not perform all of the nursing interventions. Some activities you coordinate and delegate to other members of the health care team (see Chapter 21). For example, an RN delegates components of care but not the nursing process itself (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2006). Noninvasive and frequently repetitive interventions such as skin care, ambulation, grooming, vital signs on stable patients, and hygiene measures are examples of care activities that you delegate to NAP such as a nurse assistant. When a nurse delegates aspects of a patient’s care to another staff member, the nurse who assigns the tasks is responsible for ensuring that each task is appropriately assigned and completed according to the standard of care. You are responsible for delegating direct care interventions to personnel who are competent. Recently the ANA and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) released a joint statement outlining 10 principles for delegation (Trossman, 2006). The principles are a blueprint to help RNs better understand delegation, keep patients safe, and protect their professional practice.

Achieving Patient Goals

Regardless of the type of interventions, you implement nursing care to achieve patient goals and outcomes. In most clinical situations multiple interventions are necessary to achieve select outcomes. In addition, patients’ conditions often change minute by minute. Therefore it is important for you to apply principles of care coordination such as good time management, organizational skills, and appropriate use of resources to ensure that you deliver interventions effectively and meet desired outcomes (see Chapter 21). Priority setting is critical in successful implementation. Priorities help you to anticipate and sequence nursing interventions when a patient has multiple nursing diagnoses and collaborative problems (see Chapter 18).

Another way to achieve patient goals is to help them adhere to their treatment plan. Patient adherence means that patients and families invest time in carrying out required treatments. To ensure patients a smooth transition across different health care settings (e.g., hospital to home and clinic to home to assisted living), it becomes important to introduce interventions that patients are willing and able to follow. Adequate and timely discharge planning and education of the patient and family are the first steps in promoting a smooth transition from one health care setting to another or to the home. To be effective with discharge planning and education, you individualize your care and take into consideration the various factors that influence a patient’s health beliefs. For example, for Tonya to effectively help Mr. Jacobs follow the activity limitations required after surgery, she needs to know if Mr. Jacobs understands the risks to wound healing if limitations are not followed. Chapter 6 reviews the principles of the health belief model, which influence how patients adhere to health care recommendations. You are responsible for delivering interventions in a way that reflects your understanding of a patient’s health beliefs, culture, lifestyle pattern, and patterns of wellness. In addition, reinforcing successes with the treatment plan encourages the patient to follow the care plan.

Key Points

• Implementation is the fourth step of the nursing process in which nurses initiate interventions that are designed to achieve the goals and expected outcomes of the patient’s plan of care.

• A direct-care intervention is a treatment performed through interactions with a patient that can include nurse-initiated, physician-initiated, and collaborative approaches.

• Always think first and determine if an intervention is correct and appropriate and if you have the resources needed to implement it.

• Clinical guidelines or protocols are evidence-based documents that guide decisions and interventions for specific health care problems.

• When preparing to perform an intervention, reassess the patient, review and revise the existing nursing care plan, organize resources and care delivery approaches, anticipate and prevent complications, and implement the intervention.

• The implementation of nursing care often requires additional knowledge, nursing skills, and personnel resources.

• Before beginning to perform interventions, make sure that the patient is as physically and psychologically comfortable as possible.

• Use good judgment and sound clinical decision making when performing any intervention to ensure that no nursing action is automatic.

• To anticipate and prevent complications, identify risks to the patient, adapt interventions to the situation, evaluate the relative benefit of a treatment versus the risk, and initiate risk-prevention measures.

• Methods used to ensure that you administer physical care techniques appropriately include protecting you and the patient from injury, using proper infection control practices, staying organized, and following applicable practice guidelines.

• When you delegate aspects of a patient’s care, you are responsible for ensuring that each task is assigned appropriately and completed according to the standard of care.

• To complete any nursing procedure, you need to know the procedure, its frequency, the steps, and the expected outcomes.

Clinical Application Questions

Preparing for Clinical Practice

Tonya is preparing to change the dressing over Mr. Jacobs’ wound, and Mrs. Jacobs is present to observe. Tonya determines Mr. Jacob’s level of pain to be sure that he is comfortable. She decides to include discussion of wound and urinary catheter care during her time with the family. Before beginning instruction with the Jacobs, Tonya asks Mr. Jacobs if he is ready to learn about wound and catheter care. She observes Mr. and Mrs. Jacobs’ behaviors to note their receptivity to instruction. She prepares all of her supplies before the dressing change. She also assesses the condition of the dressing before she starts.

1. When Tonya asks Mr. Jacobs about his readiness for instruction, which aspect of the implementation process is she performing?

2. When changing Mr. Jacobs’ dressing, Tonya cleans the wound following clinical practice guidelines for her nursing unit and checks the incision for signs of infection. Explain the benefit of cleansing the wound on the basis of practice guidelines.

3. When Tonya begins instructing the Jacobs about wound care, what implementation skill most likely ensures good outcomes, specifically that the patient is able to learn how to change his dressing correctly at home?

![]() Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Answers to Clinical Application Questions can be found on the Evolve website.

Are You Ready to Test Your Nursing Knowledge?

1. The nurse enters a patient’s room and finds that the patient was incontinent of liquid stool. The patient has recurrent redness in the perineal area, and there is concern that he is developing a pressure ulcer. The nurse cleanses the patient, inspects the skin, and applies a skin barrier ointment to the perineal area. She calls the ostomy and wound care specialist and asks that he visit the patient to recommend skin care measures. Which of the following describe the nurse’s actions? (Select all that apply.)

1. The application of the skin barrier is a dependent care measure.

2. The call to the ostomy and wound care specialist is an indirect care measure.

3. The cleansing of the skin is a direct care measure.

4. The application of the skin barrier is a direct care measure.

2. During the implementation step of the nursing process, a nurse reviews and revises the nursing plan of care. Place the following steps of review and revision in the correct order:

2. Decide if the nursing interventions remain appropriate.

4. Compare assessment findings to validate existing nursing diagnoses.

3. A nurse checks a physician’s order and notes that a new medication was ordered. The nurse is unfamiliar with the medication. A nurse colleague explains that the medication is an anticoagulant used for postoperative patients with risk for blood clots. The nurse’s best action before giving the medication is to:

1. Have the nurse colleague check the dose with her before giving the medication.

2. Consult with a pharmacist to obtain knowledge about the purpose of the drug, the action, and the potential side effects.

3. Ask the nurse colleague to administer the medication to her patient.

4. When does implementation begin as the fourth step of the nursing process?

1. During the assessment phase

2. Immediately in some critical situations

3. After the care plan has been developed

4. After there is mutual goal setting between nurse and patient

5. Before consulting with a physician about a patient’s need for urinary catheterization, the nurse considers the fact that the patient has urinary retention and has been unable to void on her own. The nurse knows that evidence for alternative measures to promote voiding exists, but none has been effective, and that before surgery the patient was voiding normally. This scenario is an example of which implementation skill?

6. The nurse enters a patient’s room, and the patient asks if he can get out of bed and transfer to a chair. The nurse takes precautions to use safe patient handling techniques and transfers the patient. This is an example of which physical care technique?

7. In which of the following examples is a nurse applying critical thinking attitudes when preparing to insert an intravenous (IV) catheter? (Select all that apply.)

1. Following the procedural guideline for IV insertion

2. Seeking necessary knowledge about the steps of the procedure from a more experienced nurse

3. Showing confidence in performing the correct IV insertion technique

4. Being sure that the IV dressing covers the IV site completely

8. Which steps does the nurse follow when he or she is asked to perform an unfamiliar procedure? (Select all that apply.)

2. Reassesses the patient’s condition

3. Collects all necessary equipment

4. Delegates the procedure to a more experienced staff member

9. For each of the following interventions, note which are direct and which are indirect nursing interventions. Place a D for direct or I for indirect in the space provided

1. A nurse checks the monthly performance improvement report on fall occurrences on a unit. _______________

2. A nurse discusses with the patient exercise restrictions to follow on return home. _______________

3. A nurse consults with a dietitian about a patient’s therapeutic diet food choices. _______________

4. A nurse administers a tube feeding. _______________

5. A nurse assists a colleague in applying a complex dressing to a patient’s wound. _______________

10. A nurse is talking with a patient who is visiting a neighborhood health clinic. The patient came to the clinic for repeated symptoms of a sinus infection. During their discussion the nurse checks the patient’s medical record and realizes that he is due for a tetanus shot. Administering the shot is an example of what type of preventive intervention?

11. A nurse is orienting a new graduate nurse to the unit. The graduate nurse asks, “Why do we have standing orders for cases when patients develop life-threatening arrhythmias? Is not each patient’s situation unique?” What is the nurse’s best answer?

1. Standing orders are used to meet our physician’s preferences.

2. Standing orders ensure that we are familiar with evidence-based guidelines for care of arrhythmias.

3. Standing orders allow us to respond quickly and safely to a rapidly changing clinical situation.

4. Standing orders minimize the documentation we have to provide.

12. A nurse on a cancer unit is reviewing and revising the written plan of care for a patient who has the nursing diagnosis of nausea. Place the following steps in their proper order:

1. The nurse revises approaches in the plan for controlling environmental factors that worsen nausea.

2. The nurse enters data in the assessment column showing new information about the patient’s nausea.

3. The nurse adds the current date to show that the diagnosis of nausea is still relevant.

4. The nurse decides to use the patient’s self-report of appetite and fluid intake as evaluation measures.

13. When a nurse properly positions a patient and administers an enema solution at the correct rate for the patient’s tolerance, this is an example of what type of implementation skill?

14. The nurse reviews a patient’s medical record and sees that tube feedings are to begin after a feeding tube is inserted. In recent past experiences the nurse has seen patients on the unit develop diarrhea from tube feedings. The nurse consults with the dietitian and physician to determine the initial rate that will be ordered for the feeding to lessen the chance of diarrhea. This is an example of what type of direct care measure?

15. A nurse is starting on the evening shift and is assigned to care for a patient with a diagnosis of impaired skin integrity related to pressure and moisture on the skin. The patient is 72 years old and had a stroke. The patient weighs 250 pounds and is difficult to turn. As the nurse makes decisions about how to implement skin care for the patient, which of the following actions does the nurse implement? (Select all that apply.)

Answers: 1. 2, 3, 4; 2. 3, 1, 4, 2; 3. 2; 4. 3; 5. 1; 6. 3; 7. 2, 3; 8. 1, 3, 5; 9. 1 (I), 2 (D), 3 (I) 4 (D), 5 (D); 10. 3; 11. 3; 12. 2, 3, 1, 4; 13. 4; 14. 2; 15. 1, 2, 4.

References

American Nurses Association. Principles for delegation. http://nursingworld.org/staffing/lawsuit/PrinciplesDelegation.pdf, 2006. [Accessed October 15, 2006].

American Nurses Association. Scope and standards of practice: nursing, ed 2. Silver Spring, Md: American Nurses Association; 2010.

Bulechek, GM, et al. Nursing interventions classification (NIC), ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2008.

Gerontological Nursing Interventions Research Center, Evidence-based practice guidelines. University of Iowa; 2010. http://www.nursing.uiowa.edu/Hartford/nurse.ebp.htm [based.htm. Accessed December 28, 2010].

Manchikanti, L, et al. A critical review of the American Pain Society clinical practice guidelines for interventional techniques. Part 1, Diagnostic interventions. Pain Physician. 2010;13(3):E141.

National Guideline Clearinghouse, Guidelines. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. 2010 http://www.guideline.gov [Accessed December 29, 2010].

Redman, BK. The practice of patient education, ed 10. St Louis: Mosby; 2005.

Rosenbrand, K, et al. Guideline development. Studies Health Technol Informatics. 2008;139:3.

Scherb, CA, Weydt, AP. Work complexity assessment, nursing interventions classification, and nursing outcomes classification: making connections. Creative Nurs. 2009;15(1):16.

Trossman, S. Getting a clearer picture on delegation. Am Nurs Today. 2006;1(1):54.

Research References

Benner, P. From novice to expert. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

Di Vito-Thomas, P. Nursing student stories on learning how to think like a nurse. Nurse Educ. 2005;30(3):133.

Potter, P, et al. Delegation practices between registered nurses and nursing assistive personnel. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(2):157.