Overview of Nutrition Diagnosis and Intervention

Nutrition care is an organized group of activities allowing identification of nutritional needs and provision of care to meet these needs. Comprehensive service may involve different health care providers—the physician, registered dietitian (RD), nurse, pharmacist, physical or occupational therapist, social worker, speech therapist, and case manager—who are integral in achieving desired outcomes, regardless of the care setting. A collaborative approach helps to ensure that care is coordinated and that team members and the patient are aware of all goals and priorities. Team conferences, formal or informal, are useful in all settings—a clinic, a hospital, the home, the community, a long-term care facility, or any other site where nutrition problems may be identified. Coordinating the activities of health care professionals also requires documentation of the process and regular discussions to offer complete nutritional care.

The Nutrition Care Process

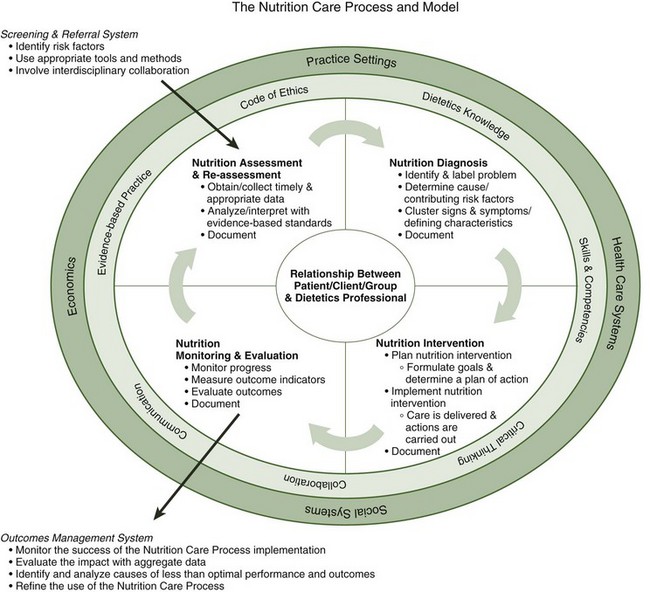

The nutrition care process (NCP) was established by the American Dietetic Association (ADA) as a standardized process for the provision of nutrition care. The patient or client is the central focus of the NCP (Figure 11-1), and benefits from the critical thinking of the RD and effective, interdisciplinary decision-making. The NCP includes four steps to be completed by the RD: (1) nutrition assessment, (2) nutrition diagnosis, (3) nutrition intervention, and (4) monitoring and evaluation (American Dietetic Association [ADA], 2010).

FIGURE 11-1 The nutrition care process. (©2011 American Dietetic Association. Reprinted with permission.)

Nutrition Screening and Assessment

Nutrition screening provides a mechanism to identify patients or clients who would benefit from nutrition assessment. Most health care facilities have developed a multidisciplinary admission screening process that is completed by nursing staff during admission to the facility. One efficient mechanism for completing the nutrition screen is to incorporate the screen into this admission assessment. The nutrition risk screen should be quick, easy to administer, and cost-effective while maintaining accuracy. Patients identified as “at risk” during the admission screen should be referred to the RD for nutrition assessment. Table 11-1 lists information that is frequently included in a nutrition screen.

TABLE 11-1

| Responsible Party | Action | Documentation |

| Admitting health care professional | Assess weight status—Has the patient lost weight without trying before admission? | Check yes or no on admission screen. |

| Admitting health care professional | Assess GI symptoms—Has the patient had GI symptoms preventing usual intake over the past 2 weeks? | Check yes or no on admission screen. |

| Admitting health care professional | Determine need to consult RD. | If either screening criterion is “yes,” consult RD for nutrition assessment. |

When the ADA’s Evidence Analysis Library (EAL) team conducted a systematic review of acute care screening tools, they determined that the Malnutrition Screening Tool had acceptable reliability and validity (ADA,2010). Rescreening should occur at regular intervals during the admission. In hospitalized patients, there may be a relationship between length of stay and worsening nutrition status. Policies for nutrition rescreening should take into account the average length of time a patient will stay at the facility. Nutrition assessment is needed when the screening highlights potential areas of concern (see Chapter 4 for methods and tools).

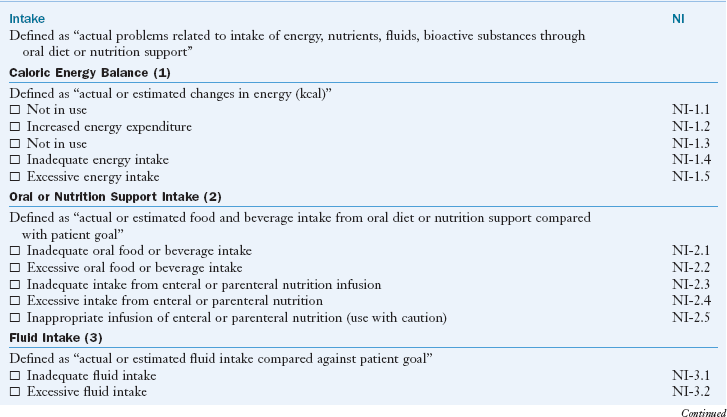

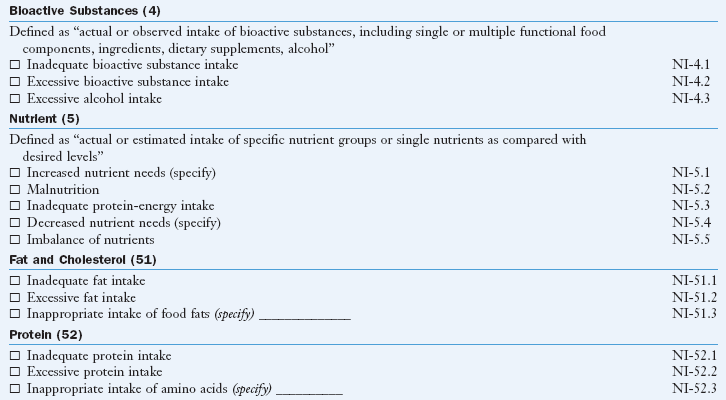

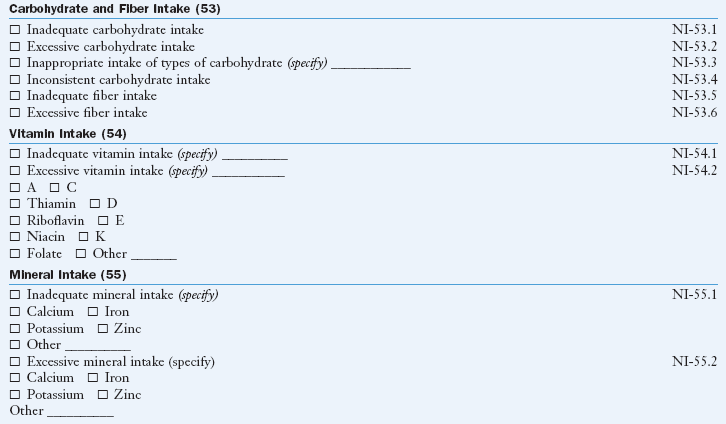

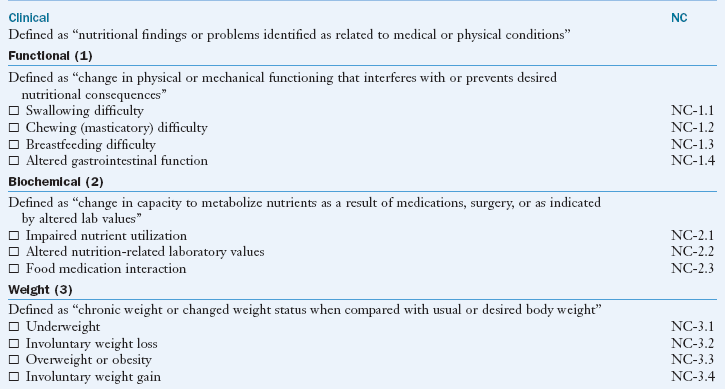

Nutrition Diagnosis

After assessment of nutrition status using all of the available data, nutrition diagnoses (problems or needs) are identified, prioritized, and documented in the medical record. Selection of an accurate nutrition diagnosis is guided by critical evaluation of each component of the assessment, combined with critical judgment and decision-making skills. Patients with nutrition diagnoses may be at higher risk for nutrition-related complications such as increased morbidity, increased length of hospital stay, and infectious complications. Nutrition-related complications can lead to a significant increase in costs associated with hospitalization, lending support to the early diagnosis of nutrition problems followed by prompt intervention.

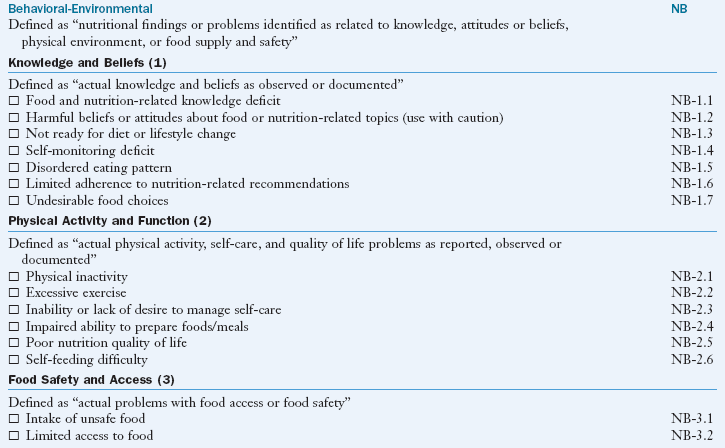

Many facilities use standardized formats to facilitate communication of information gathered in the nutrition assessment and nutrition diagnosis phase. A nutrition diagnosis includes documentation of the problem, etiology, signs and symptoms (PES) in a simple, clear statement. Methods used for documenting nutrition care in the medical record are determined at the facility level. RDs in private practice should also develop a systematic method for documenting care provided. Box 11-1 lists the nutrition diagnoses currently in use by the ADA.

Nutrition Intervention

Nutrition interventions are the actions taken intended to address the nutrition problem. Because the intervention must be an action taken by the RD, assessment of the problem must focus on any nutrition-related causes of the problem rather than the medical diagnosis. Nutrition intervention involves two steps: planning and implementation. During the planning phase of the nutrition intervention, the RD, patient or client, and others as needed collaborate to identify goals and objectives that will signify success of the intervention. Patient-centered goals and objectives are set, and then implementation begins. Interventions may include food and nutrition therapies, nutrition education, counseling, or coordination of care such as providing referral for financial or food resources. Because the care process is continuous, the initial plan may change as the condition of the patient changes, as new needs are identified, or if the interventions are unsuccessful.

Interventions should be specific; they are the “what, where, when, and how” of the care plan (ADA, 2010). For example, in a patient with “inadequate oral food or beverage intake,” an objective might be to increase portion sizes at two meals per day. This could be implemented through provision of portions that are initially 5% larger with a gradual increase to 25% larger portion sizes. Plans should be communicated to the health care team and the patient to ensure understanding of the plan and its rationale. Thorough communication by the RD increases the likelihood of adherence to the plan. Box 11-2 presents the NCP applied to a sample patient, JW.

Monitoring and Evaluation of Nutrition Care

The fourth step in the NCP involves monitoring and evaluation of the effect of nutrition interventions. This clarifies the effect that the RD has in the specific setting, whether health care, education, consulting, food services, or research. During this step, the RD first determines indicators that should be monitored. These indicators should match the signs and symptoms identified during the assessment process. For example, if excessive sodium intake was identified during the assessment, then an evaluation of the sodium intake is needed at a designated time for follow-up.

In the clinical setting the goal of nutrition care is to meet the nutritional needs of the patient or client; thus the interventions must be monitored and the meeting of the objectives evaluated frequently. This ensures that unmet objectives are addressed and that care is evaluated and modified in a timely manner. Monitoring and evaluation are not unique to nutrition practice. Evaluation of the monitored indicators provides objective data to demonstrate effectiveness of nutrition interventions, regardless of the setting or focus. If objectives are written in measurable, behavioral terms, evaluation is relatively easy because new behavior is being measured against a behavior that has already been defined.

An example in clinical practice is the sample case in Box 11-2. Here, monitoring and evaluation include weekly reviews of his nutritional intake, including an estimation of energy intake. If intake was less than the goal of 1800 kcal, the evaluation might be: “JW was not able to increase his calorie intake to 1800 kcal because of his inability to cook and prepare meals for himself.” A revision in the care plan at this point might include the following: “JW will be provided a referral to local agencies (Meals on Wheels) that can provide meals at home.” This new intervention is then implemented with continued monitoring and evaluation to determine whether the new objective can be met.

When evaluation reveals that objectives are not being met or that new needs have arisen, the process begins again with reassessment, identification of new nutrition diagnoses, and formulation of a new NCP. For example, in JW’s case, during his hospitalization, high-calorie snacks were provided. However, monitoring reveals that JW’s usual eating pattern does not include snacks, and thus he was not consuming them. The evaluation showed these snacks to be an ineffective intervention. JW agrees to a new intervention—the addition of one more food to his meals. Further monitoring and evaluation will be needed to ascertain if this new intervention improves his intake.

Evidence-Based Guidelines

Evidence-based practice is use of current “best evidence” in making decisions about the care of individual patients. “Best evidence” includes high-quality research, systematic reviews of the literature, and metaanalysis to support decisions made in practice. Comprehensive use of evidence-based guidelines (EBGs) leads to improved quality of care. The guides may also create new research questions.

In the 1990s, the ADA began developing nutrition practice guidelines and evaluating how their use affected clinical outcomes; diabetes management was among the first (Franz et al., 2008). These evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines are disease- and condition-specific recommendations with toolkits. Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) evidence-based guides are available to assist dietetic practitioners in providing nutrition care, especially for diabetes and prerenal failure. MNT provided by a Medicare Part B licensed provider can be reimbursed when the EBGs are used and all procedural forms are properly documented and coded (White et al., 2008).

To define professional practice by the RD, the ADA has published a Scope of Dietetics Practice Framework, a Code of Ethics, and the Standards of Professional Performance (SOPPs). Specialized standards for knowledge, skills, and competencies required to provide care at the generalist, specialist, and advanced practice level for a variety of populations are now complete for many areas of practice. Benefits of nutrition therapy can be communicated to physicians, insurance companies, administrators, or other health care providers using evidence provided from these guidelines. The EBGs include major recommendations, background information, and a reference list.

Overall, the ADA’s EAL provides the best available evidence to answer questions that arise during provision of nutrition care. Use of this library is essential to protect the practitioner and the public from the consequences of ineffective care. These guidelines are extremely valuable for staff orientation, competence verification, and training of RDs anywhere in the world.

Accreditation and Surveys

Accreditation by The Joint Commission (TJC), formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, involves a peer review process. TJC survey teams evaluate health care institutions to evaluate their compliance with established minimum standards. TJC requires that nutrition screening be completed within 24 hours of admission to acute care, but does not mandate a method to accomplish screening.

TJC focuses on the facility’s actual performance of important governance, managerial, clinical, and support functions. It also focuses on the continual process improvement (PI) in an organization’s performance of these functions. Standards are provided in the Accreditation Manual for Hospitals document, which is updated and revised on a yearly basis. This document consists of three sections: (1) patient-focused functions; (2) organization-focused functions; and (3) structures with functions, which provides descriptions of the various departments and their roles. Its approach is a functional one, and all departments and disciplines must be familiar with relevant issues found in applicable chapters. Most chapters contain standards that affect the care provided by a dietitian.

The “Care of the Patient” section contains standards that apply specifically to medication use, rehabilitation, anesthesia, operative and other invasive procedures, and special treatments, as well as nutrition care standards. The focus of the nutrition care standards is provision of appropriate nutrition care in a timely and effective manner using an interdisciplinary approach. Appropriate care requires screening of patients for nutrition needs, assessing and reassessing patient needs, developing an NCP, ordering and communicating the diet order, preparing and distributing the diet order, monitoring the process, and continually reassessing and improving the NCP. A facility can define who, when, where, and how the process is accomplished; but TJC specifies that a qualified dietitian must be involved in establishing this process. A plan for the delivery of nutrition care may be as simple as providing a regular diet for a patient who is not at nutritional risk or as complex as managing tube feedings in a ventilator-dependent patient, which involves the collaboration of multiple disciplines.

The accreditation process typically involves an on-site survey that lasts for several days. During this survey adherence to standards is ascertained through interviews, review of documents (including patient medical records), and visits to patient care and other areas. In addition, a tracer method is now being used, which identifies an issue that surveyors can follow throughout the care of a specific patient.

RDs are actively involved in the survey process. Standards set by TJC play a large role in influencing the standards of care delivered to patients in all health care disciplines. For more information, see the TJC website at www.jointcommission.org.

Dietitians are also involved with surveys from other regulatory bodies, such as a state or local health department, a department of social services, or licensing organizations. Sentinel events are unintended events that are unanticipated and often unwelcome (Ash, 2007). These events must be prevented. When or if they do occur, the outcomes must be documented in the medical record. Regardless of the source of the survey, it is imperative to follow all regulations and guidelines at all times and not just when a survey is due.

Documentation in the Nutrition Care Record

MNT and other nutrition care provided must be documented in the health or medical record. The medical record is a legal document; if interventions are not recorded, it is assumed that they have not occurred. Documentation affords the following advantages:

• It ensures that nutrition care will be relevant, thorough, and effective by providing a record that identifies the problems and sets criteria for evaluating the care.

• It allows the entire health care team to understand the rationale for nutrition care, the means by which it will be provided, and the role each team member must play to reinforce the plan and ensure its success.

The medical record serves as a tool for communication among members of the health care team. Beginning in 2014, health care facilities must use electronic health records (EHRs) to document patient care, store and manage laboratory and test results, communicate with other entities, and maintain all information related to an individual’s health. During the transition period, those using paper documentation maintain paper charts that typically include sections for physician orders, medical history and physical examinations, laboratory test results, consults, and progress reports. Although the format of the medical record varies depending on facility policies and procedures, in most settings all professionals document care in the medical record. The RD must ensure that all aspects of nutrition care are summarized succinctly in the medical record.

Medical Record Charting

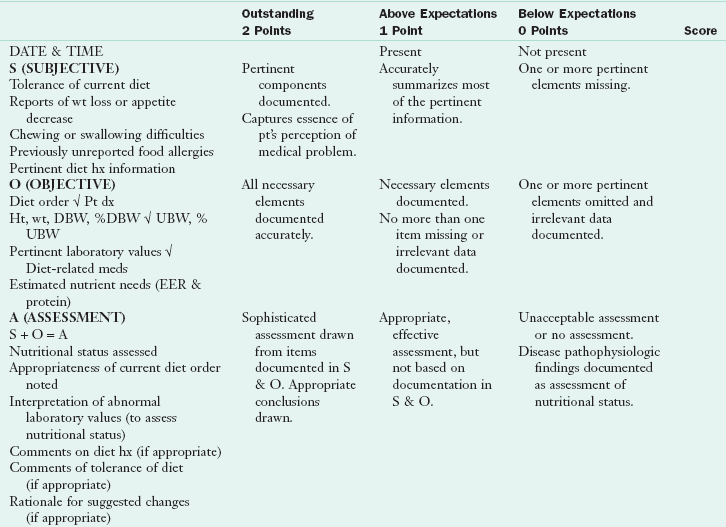

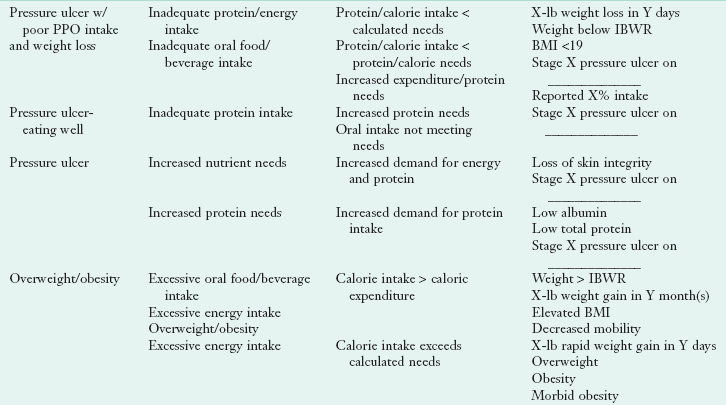

Problem-oriented medical records (POMRs) are used in many facilities. The POMR is organized according to the patient’s primary problems. Entries into the medical record can be done in many styles. One of the most common forms is the subjective, objective, assessment, plan (SOAP) note format (Table 11-2).

TABLE 11-2

Evaluation of a Note in SOAP Format

DBW, Desired body weight; Dx, diagnosis; EER, estimated energy requirements; F/U, follow up; ht, height; hx, history; PO, by mouth; PRN, as necessary; pt, patient; Rx, prescription; SOAP, subjective, objective, assessment, plan; TF, tube feeding; TPN, total parenteral nutrition; UBW, usual body weight; wt, weight.

Courtesy Sara Long, PhD, RD.

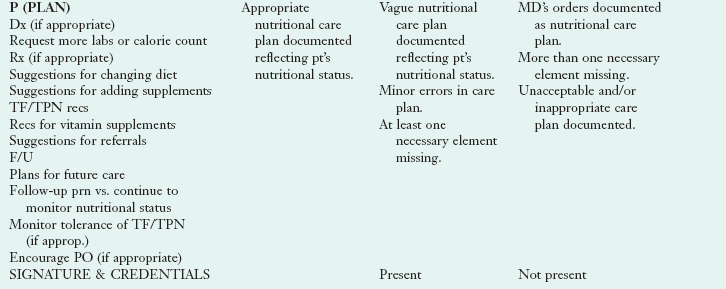

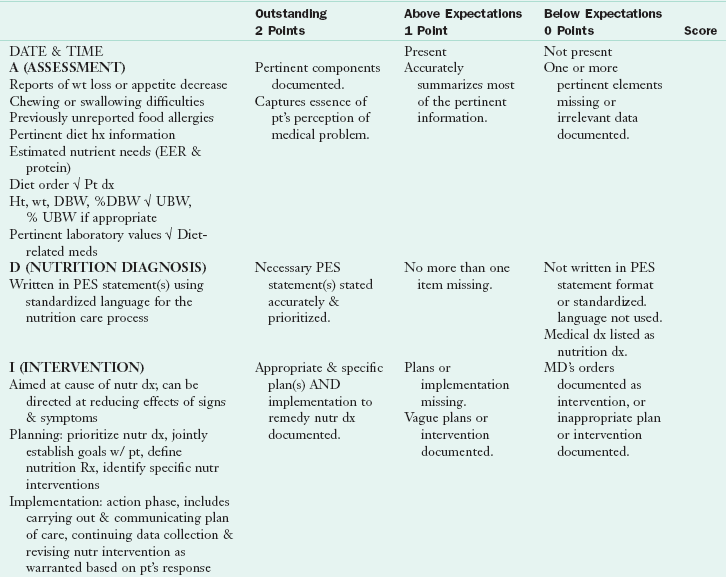

The assessment, diagnosis, interventions, monitoring, evaluation (ADIME) format is used by many nutrition departments to reflect the steps of the NCP (Box 11-3; Table 11-3). See Table 11-4 for common nutrition diagnostic (PES) statements.

TABLE 11-3

Evaluation of a Note in ADIME Format

ADIME, Assessment, diagnosis, intervention, monitoring, evaluation; DBW, desirable body weight; dx, diagnosis; EER, estimated energy requirement; ht, height; hx, history; MD, medical doctor; meds, medications; nutr, nutrition; PES, problem, etiology, signs and symptoms; pt, patient; Rx, prescription; UBW, usual body weight; w/, with; wt, weight.

Courtesy Sara Long, PhD, RD.

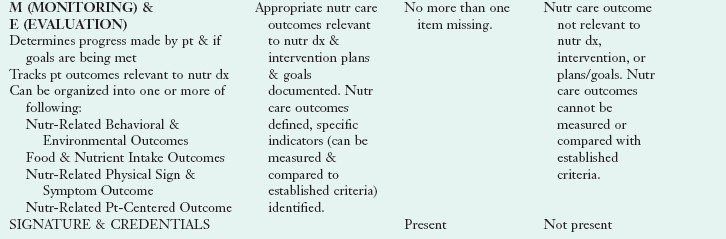

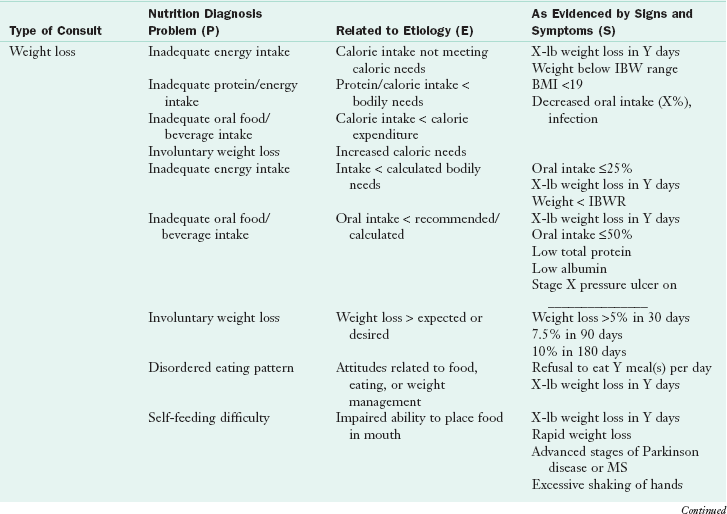

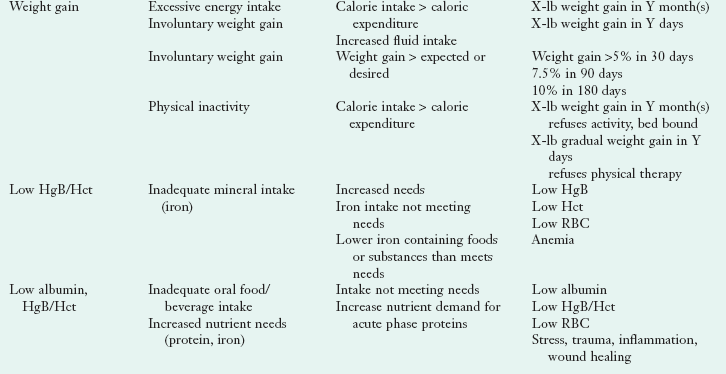

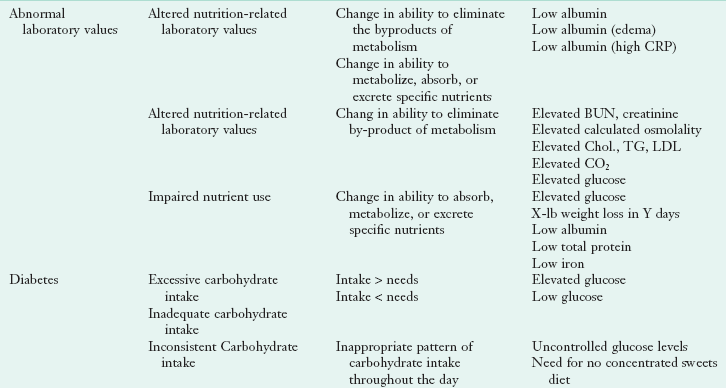

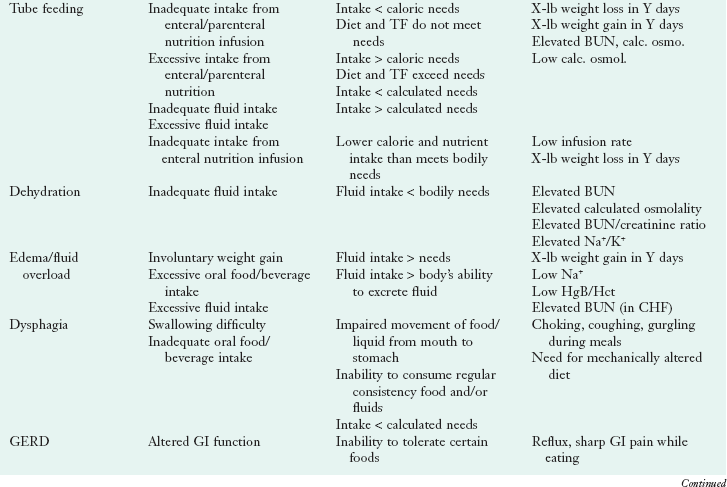

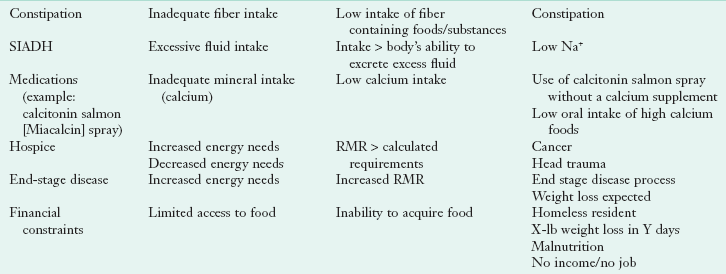

TABLE 11-4

Types of Consults and Sample PES Statements

BMI, Body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; calc. osmol., calculation of osmolity; CHF, congestive heart failure; CO2, carbon dioxide; Chol, cholesterol; CRP, C-reactive protein; Hct, hematocrit; HgB, hemoglobin; IBW, ideal body weight; IBWR, ideal body weight range; K+, potassium; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MS, multiple sclerosis; Na+, sodium; PES, problem, etiology, and signs and symptoms; PO, by mouth; RBC, red blood cell; TF, tube feeding; G, triglyceride; w/, with.

The important factor is the content of the documentation, not necessarily the style. All entries made by the dietitian should address the issues of nutrition status and needs. Notes must be accurate and concise, and they must be able to convey important information to the physician and other health care team members so that they might take action. In a paper-based system, the following are general guidelines for documentation in the hospital setting:

• All entries should be written in black pen or typewritten.

• Documentation should be complete, clear, concise, objective, legible, and accurate.

• Entries should include date, time, and service. Each page should include the patient’s name and hospital number.

• Entries should be in chronologic order and be consecutive.

• The first word of every statement should be capitalized, with periods placed at the end of each thought. Complete sentences are not necessary, but grammar and spelling should be correct.

• All entries should be consistent and noncontradictory.

• All entries must be signed at the end and should include credentials (e.g., J. Wilson, RD). No one should ever chart or sign the medical record for another individual.

• Personal opinions and comments criticizing or casting doubt on the professionalism of others should never be included.

• Documentation must be done at the time of the actual procedure or service.

• Late entries should be identified as such, including the actual date and time of the entry and the date and time it should have been recorded. Never add notes after the fact without accurately authenticating, dating, and referencing the original entry.

• Paper medical record entries should always be legible. When correcting an error draw a single line through the error and initial. Never use correction fluid, correction tape, self-adhesive labels, or thick marker strokes. Never remove an original and replace it with a copy.

• If information is accidentally omitted, write “see addendum” by the original entry, add the date and initial, and write the content in the medical record, identified as an addendum with the date and time of the original entry.

Electronic Health Records and Nutrition Informatics

Prior to the early 1990s, technology advances did not meet the needs of clinicians in practice. Since then, costs for memory space have decreased, hardware has become more portable, and system science has sufficiently advanced to make EHRs a permanent fixture in health care. Additional impetus to change standard practice came with publication of several Institute of Medicine reports that brought to light a high rate of preventable medical errors along with the recommendation to use technology as a tool to improve health care quality and safety.

Clinical information systems used in health care are known by different names; although some use electronic medical record (EMR), EHR, and personal health record (PHR) interchangeably, there are important differences. Electronic health record (EHR) describes information systems that contain all the health information for an individual. Another term that might be seen includes an electronic medical record (EMR), which typically describes a clinical information system used by a health care organization to document patient care. Both the EHR and EMR are maintained by health care providers. In contrast, the personal health record (PHR) is a system that is used by the consumer to maintain health information. A PHR can be web-based, free-standing, or integrated to a facility’s EMR.

EHRs include all of the information typically found in a paper-based documentation system along with tools such as clinical decision support, electronic medication records, and alert systems that will support clinicians in making decisions regarding patient care. By 2014, all health care providers will use EHRs to enter, store, retrieve, and manage information related to patient care. Dietitians must have at least a basic understanding of technology and health information management to ensure a smooth transition from paper to EHR. Such transition will include the development of nutrition screens for patient admission, documentation, information sharing, decision support tools, and order entry. Customization capabilities vary depending on vendor contracts; RDs managing nutrition services must be involved in EHR system decisions at the very beginning, prior to communication of a request for proposals to potential vendors.

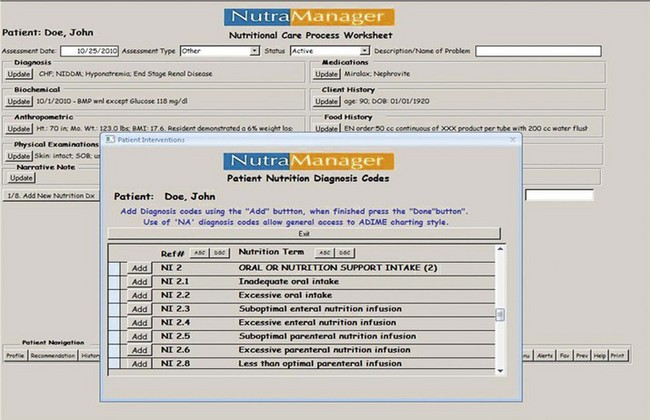

In both paper and electronic formats, medical records and the information contained are vital conduits for communicating patient care to others, providing information for quality evaluation and improvement, and as a legal document. RD documentation includes information related to NCPs. Documentation must follow the facility policy and be brief and concise while accurately describing actions taken to those authorized to view the record. Figure 11-2 shows how a computerized medical record might look when using the ADIME method.

FIGURE 11-2 Example of electronic chart note using drop-down boxes on computer. (Courtesy Maggie Gilligan, RD, owner of NUTRA-MANAGER, 2010.)

Federal requirements mandate that provider systems be “interoperable,” meaning that information can be safely and securely exchanged between providers and facilities. Although this concept seems simple on the surface, problems with interoperability will be very difficult and expensive to overcome. The transition from paper to electronic documentation can be facilitated by thorough planning, training, and support. Many RDs in practice have little experience with technology; they may not fully understand the practice improvement that can be realized with proper implementation and use of technology. Others may resist any change in the workplace that interrupts their current workflow. Change is never easy (Schifalacqua, 2009).

Clinical system vendors might convince administrators that the transition will be simple and that time savings will be realized immediately following implementation. Quite often this is not the case, leading to unsatisfied clinicians and an expensive tool that is not properly used (Demiris, 2007). RDs participating in implementation of EHRs in health care must be aware of possible resistance or “human issues,” ensuring that all involved are properly trained.

Influences On Nutrition And Health Care

The health care environment has undergone considerable change related to the provision of care and reimbursement in the last decade. Governmental influences, cost containment issues, changing demographics, and the changing role of the patient as a “consumer” have influenced the health care arena. The United States currently spends more on health care than any other nation, yet health care outcomes lag far behind those seen in other developed nations. Exponential increases in health care costs in the United States have been a major impetus for drives to reform how health care is provided and paid for in the United States (Ross, 2009).

Affordable Health Care for America: Reconciliation Bill

All Americans will have access to quality, affordable health care under a final package of health insurance reforms signed into law in March 2010. The law will protect Americans from insurance industry practices, offer the uninsured and small businesses the opportunity to obtain affordable health care plans, cover 32 million uninsured Americans, and reduce the deficit by $143 billion over the next decade.

Confidentiality and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

Privacy and security of personal information is of concern in all health care settings. In 1996 Congress passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2010). The initial intent of HIPAA was to ensure that health insurance eligibility was maintained when people changed or lost jobs. The Administrative Simplification provisions of HIPAA require development of national standards that maintain privacy of protected health information (PHI). HIPAA requires that health care facilities and providers (covered entities) take steps to safeguard PHI. Although HIPAA does not prevent sharing of patient data required for an incident of care, patients must be notified if their medical information is to be shared outside of the care process or if protected information (e.g., address, e-mail, income) is to be shared. RDs must use common sense when working with PHI; it is never appropriate to look at another person’s medical record unless the RD is involved in the care of that patient. Violations of HIPAA rules have resulted in large fines and loss of jobs.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was written in 2010. Final regulations require group health plans and health insurance issuers to provide coverage of dependent children younger than age 26.

Payment Systems

One of the largest influences on health care delivery in the last decade has been the change in the method of payment for services provided. There are several common methods of reimbursement: cost-based reimbursement, negotiated bids, and diagnostic-related groups (DRGs). Under the DRG system, a facility receives payment for a patient’s admission based on the principal diagnosis, secondary diagnosis (comorbid conditions), surgical procedure (if appropriate), and the age and gender of the patient. Approximately 500 DRGs cover the entire spectrum of medical diagnoses and surgical treatments. Preferred-provider organizations (PPOs) and managed-care organizations (MCOs) also changed health care. MCOs finance and deliver care through a contracted network of providers in exchange for a monthly premium, changing reimbursement from a fee-for-service system to one in which fiscal risk is borne by health care organizations and physicians. New legislation will likely change the face of reimbursement even more.

Quality Management

To contain health care costs while providing efficient and effective care that is of consistently high quality, practice guidelines or standards of care are used. These sets of recommendations serve as a guide for defining appropriate care for a patient with a specific diagnosis or medical problem. They help to ensure consistency and quality for both providers and clients in a health care system and, as such, are specific to an institution or health care organization. Critical pathways, or care maps, identify essential elements that should occur in the patient’s care and define a timeframe in which each activity should occur to maximize patient outcomes. They often use an algorithm or flowchart to indicate the necessary steps required to achieve the desired outcomes. Disease management is designed to prevent a specific disease progression or exacerbation, and to reduce the frequency and severity of symptoms and complications. Education and other strategies maximize compliance with disease treatment. Educating a patient with type 1 diabetes regarding control of blood glucose levels would be an example of a disease management strategy aimed at decreasing the complications (nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy) and the frequency with which the client needs to access the care provider. Decreasing the number of emergency room visits related to hypoglycemic episodes is a sample goal.

Patient-Centered Care and Case Management

The case management process strives to promote the achievement of patient care goals in a cost-effective, efficient manner. It is an essential component in delivering care that provides a positive experience for the patient, ensures achievement of clinical outcomes, and uses resources wisely. Case management involves assessing, evaluating, planning, implementing, coordinating, and monitoring care, especially in patients with chronic disease or those who are at high risk. In some areas, dietitians have added skill sets that enable them to serve as case managers. Utilization management is a system that strives for cost efficiency by eliminating or reducing unnecessary tests, procedures, and services. Here, a manager is usually assigned to a group of patients and is responsible for ensuring adherence to preestablished criteria.

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is a new development that focuses on the relationship between the patient and his or her personal physician. The personal physician takes responsibility for all aspects of health care for the patient and acts to coordinate and communicate with other providers as needed. Other providers such as nurses, health educators, and allied health professionals may be called on by the patient or personal physician for preventative and treatment services. When specialty care is needed, the personal physician becomes responsible for ensuring that care is seamless and that transitions between care sites go smoothly (Backer, 2007; Ornstein 2008). The RD should be considered part of the medical home treatment plan.

Regardless of model, the facility must manage patient care prudently. Nutrition screening can be very important in identifying patients who are nutritionally compromised. Early identification of these factors allows for timely intervention and helps prevent the comorbidities often seen with malnutrition, which may cause the length of stay and costs to increase. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has identified several conditions, such as heart failure, for which no additional reimbursement will be received if a patient is readmitted to acute care within 30 days of a prior admission. Although many view this rule as punitive, it does provide an opportunity for RDs to demonstrate how nutrition services, including patient education, can save money through decreased readmissions.

Other recent developments include “never events.” Never events are those occurrences that should never happen in a facility that provides high-quality, safe, patient-focused care. RDs must pay attention to new or worsening pressure ulcers and central line infections as potential “never events.”

Staffing and Nutrition Coding

Staffing also affects the success of nutrition care. Clinical dietitians may be centralized (all are part of a core nutrition department) or decentralized (individual dietitians are part of a unit or service that provides care to patients), depending on the model adopted by a specific institution. Certain departments such as food service, accounting, and human resources remain centralized in most models because some of the functions for which these departments are responsible are not directly related to patient care. Dietitians should be involved in the planning for any redesign of patient care. Regardless of where dietitians work, they need to implement the NCP, use the standardized terminology of the profession, and code their services accurately (see Focus On: Nutrition Standardized Language and Coding Practices).

Nutrition Interventions

The RD is the only licensed provider who can reliably offer food and nutrition services that are credible and highly individualized. The RD expert is able to inform, educate, and inspire his or her clients. This guidance is health-enhancing and, often, life-changing. The profession offers stringent guidelines for practice, with science-based information that is not compromised by market forces. The RD must complete continuing education and rigorous reviews of competency every 5 years to maintain that credential. In addition, there are a myriad of position papers and journal articles that keep members up to date to support the “total diet approach” to good nutritional intake.

The evaluation of general and modified diets requires in-depth knowledge of the nutrients contained in different foods. In particular, it is essential to be aware of the nutrient-dense foods that contribute to dietary adequacy. Balance and judgment are needed. Sometimes a vitamin-mineral supplement is necessary to meet the patient’s needs when the intake is limited. Chapter 3 and Appendixes 46-58 provide detailed information on specific minerals and vitamins and the foods that contain them.

Interventions: Food and Nutrient Delivery

The nutrition prescription designates the type, amount, and frequency of nutrition based on the individual’s disease process and disease management goals. The prescription may specify a caloric level or other restriction to be implemented. It may also limit or increase various components of the diet, such as carbohydrate, protein, fat, alcohol, fiber, water, specific vitamins or minerals, bioactive substances such as phytonutrients (see Chapter 3). RDs write the nutrition prescription following diagnosis of nutrition problems.

Note that a diet order differs from a nutrition prescription. In most states, only a licensed independent health care provider can enter diet orders into a patient’s medical record. Typically, physicians, physician assistants, and advanced practice nurses are considered to be licensed independent providers. In some facilities, RDs have been granted order-writing privileges. It should be remembered that the ability to enter orders does not absolve the RD of the need to communicate and coordinate care with the provider who is ultimately responsible for all aspects of patient care.

Therapeutic or modified diets are based on a general, adequate diet that has been altered to provide for individual requirements, such as digestive and absorptive capacity, alleviation or arrest of a disease process, and psychosocial factors. In general, the therapeutic diet should vary as little as possible from the individual’s normal diet. Personal eating patterns and food preferences should be recognized, along with socioeconomic conditions, religious practices, and any environmental factors that influence food intake, such as where the meals are eaten and who prepares them (see “Cultural Aspects of Dietary Planning” in Chapter 12).

A nutritious and adequate diet can be planned in many ways. One foundation of such a diet is the MyPlate Food Guidance System (see Fig. 12-1). This is a basic plan; additional foods or more of the foods listed are included to provide additional energy and increase the intake of required nutrients for the individual. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans are also used in meal planning and to promote wellness. The dietary reference intakes (DRIs) and specific nutrient recommended dietary allowances are formulated for healthy persons, but they are also used as a basis for evaluating the adequacy of therapeutic diets. Nutrient requirements specific to a particular person’s genetic makeup, disease state, or disorder must always be kept in mind during diet planning.

Modifications of the Normal Diet

Normal nutrition is the foundation on which therapeutic diet modifications are based. Regardless of the type of diet prescribed, the purpose of the diet is to supply needed nutrients to the body in a form that it can handle. Adjustment of the diet may take any of the following forms:

• Change in consistency of foods (liquid diet, pureed diet, low-fiber diet, high-fiber diet)

• Increase or decrease in energy value of diet (weight-reduction diet, high-calorie diet)

• Increase or decrease in the type of food or nutrient consumed (sodium-restricted diet, lactose-restricted diet, fiber-enhanced diet, high-potassium diet)

• Elimination of specific foods (allergy diet, gluten-free diet)

• Adjustment in the level, ratio, or balance of protein, fat, and carbohydrate (diet for diabetes, ketogenic diet, renal diet, cholesterol-lowering diet)

• Rearrangement of the number and frequency of meals (diet for diabetes, postgastrectomy diet)

• Change in route of delivery of nutrients (enteral or parenteral nutrition)

Diet Modifications in Hospitalized Patients

Food is an important part of nutrition care. Attempts should be made to honor patient preferences during illness and recovery from surgery. Imagination and ingenuity in menu planning are essential when planning meals acceptable to a varied patient population. Attention to color, texture, composition, and temperature of the foods, coupled with a sound knowledge of therapeutic diets, is required for menu planning. However, to the patient, good taste and attractive presentation are most important. When possible, patient choices of food are most likely be consumed. The ability to make food selections gives the patient an option in an otherwise limiting environment.

Hospitals have to adopt a diet manual that serves as the reference for that facility. The ADA has an online manual that can be purchased for several users per facility. All hospitals or health care institutions have basic, routine diets designed for uniformity and convenience of service. These standard diets are based on the foundation of an adequate diet pattern with nutrient levels as derived from the DRIs. Types of standard diets vary but can generally be classified as general or regular or modified consistency. The diets should be realistic and meet the nutritional requirements of the patients. The most important consideration of the type of diet offered is providing foods that the patient is willing and able to eat and that fit in with any required dietary restrictions. Shortened lengths of stay in many health care settings result in the need to optimize intake of calories and protein and this often translates into a liberal approach to therapeutic diets. This is especially true when the therapeutic restrictions might compromise intake and subsequent recovery from surgery, stress, or illness.

Regular or General Diet

“Regular” or “general diets are used routinely and serve as a foundation for more diversified therapeutic diets. In some institutions a diet that has no restrictions is referred to as the regular or house diet. It is used when the patient’s medical condition does not warrant any limitations. This is a basic, adequate, general diet of approximately 1600 to 2200 kcal; it usually contains 60 to 80 g of protein, 80 to 100 g of fat, and 180 to 300 g of carbohydrate. Although there are no particular food restrictions, some facilities have instituted regular diets that are low in fat, saturated fat, cholesterol, sugar, and salt to follow the dietary recommendations for the general population. In other facilities the diet focuses on providing foods the patient is willing and able to eat, with less focus on restriction of nutrients. Many institutions have a selective menu that allows the patient certain choices; the adequacy of the diet varies based on the patient’s selections.

Consistency Modifications

Modifications in consistency may be needed for patients who have limited chewing or swallowing ability. Chopping, mashing, pureeing, or grinding food modifies its texture. See Chapter 41 and Appendix 35 for more information on consistency modifications and for neurologic changes in particular.

Clear liquid diets include some electrolytes and small amounts of energy from tea, broth, carbonated beverages, clear fruit juices, and gelatin. Milk and liquids prepared with milk are omitted, as are fruit juices that contain pulp. Fluids and electrolytes are often replaced intravenously until the diet can be advanced to a more nutritionally adequate one.

There is little scientific evidence supporting the use of clear liquid diets as transition diets after surgery (Jeffery et al., 1996). The average clear liquid diet contains only 500 to 600 kcal, 5 to 10 g of protein, minimum fat, 120 to 130 g of carbohydrate, and small amounts of sodium and potassium. It is inadequate in calories, fiber, and all other essential nutrients and should be used only for short periods. In addition, full liquid diets are also not recommended for a prolonged time. If needed, oral supplements may be used to provide more protein and calories.

Food Intake

Food served does not necessarily represent the actual intake of the patient. Prevention of malnutrition in the health care setting requires observation and monitoring of the adequacy of patient intake. If food intake is inadequate, measures should be taken to provide foods or supplements that may be better accepted or tolerated. Regardless of the type of diet prescribed, both the food served and the amount actually eaten must be considered to obtain an accurate determination of the patient’s energy and nutrient intake. Nourishments and calorie-containing beverages consumed between meals are also considered in the overall intake. It is important that the RD maintain communication with nursing and food service personnel to determine adequacy of intake. Although calorie counts are often inaccurate and incomplete, they are sometimes used to justify the need for enteral or parenteral nutrition.

Acceptance and Psychological Factors

Meals and between-meal nourishments are often highlights of the day and are anticipated with pleasure by the patient. Mealtime should be as positive an experience as possible. Whatever setting the patient is eating in should be comfortable for the patient. Food intake is encouraged in a pleasant room with the patient in a comfortable eating position in bed or sitting in a chair located away from unpleasant sights or odors. Eating with others often promotes better intake.

Arrangement of the tray should reflect consideration of the patient’s needs. Dishes and utensils should be in a convenient location. Independence should be encouraged in those who require assistance in eating. The caregiver can accomplish this by asking patients to specify the sequence of foods to be eaten and having them participate in eating, if only by holding their bread. Even visually impaired persons can eat unassisted if they are told where to find foods on the tray. Patients who require feeding assistance should be fed when the foods are still at an optimal temperature. The feeding process requires about 20 minutes as a general rule.

Poor acceptance of foods and meals may be caused by unfamiliar foods, a change in eating schedule, improper food temperatures, the patient’s medical condition, or the effects of medical therapy. Food acceptance is improved when personal selection of menus is encouraged. There is a revolution occurring in hospital food service. Most hospitals have a room service–style menu or are actively working to implement one to solve the problems related to dissatisfaction and poor intake.

Patients should be given the opportunity to share concerns regarding meals, which may improve acceptance and intake. In encouraging acceptance of a therapeutic diet, the attitude of the caregiver is important. The nurse who understands that the diet contributes to the restoration of the patient’s health will communicate this conviction by actions, facial expressions, and conversation. Patients who understand that the diet is important to the success of their recovery usually accept it more willingly. When the patient must adhere to a therapeutic dietary program indefinitely, an interdisciplinary approach will help him or her achieve nutritional goals. Because they have frequent contact with patients, nurses play an important role in a patient’s acceptance of nutrition care. Ensuring that the nursing staff is aware of the NCP can greatly improve the probability of success.

Interventions: Nutrition Education and Counseling

Nutrition education is an important part of the MNT provided to many patients. The goal of nutrition education is to help the patient acquire the knowledge and skills needed to make changes, including modifying behavior to facilitate sustained change. Nutrition education and dietary changes can result in many benefits, including control of the disease or symptoms, improved health status, enhanced quality of life, and decreased health care costs.

As the average length of hospital stays has decreased, the role of the in-patient dietitian in educating inpatients has changed to providing brief education or “survival skills.” This education includes the types of foods to limit, timing of meals, and portion sizes. Follow-up outpatient counseling should be encouraged to reinforce the basic counseling given during hospitalization. See Chapter 14 for managing nutrition support and Chapter 15 for counseling skills.

Intervention: Coordination of Care

Nutrition care is part of discharge planning. Education, counseling, and mobilization of resources to provide home care and nutrition support are included in discharge procedures. Completing a discharge nutritional summary for the next caregiver is imperative for optimal care. Appropriate discharge documentation includes a summary of nutrition therapies and outcomes; pertinent information such as weights, laboratory values, and dietary intake; potential drug-nutrient interactions; expected progress or prognosis; and recommendations for follow-up services. Types of therapy attempted and failed can be very useful information. The amount and type of instruction given, the patient’s comprehension, and the expected degree of adherence to the prescribed diet are included. An effective discharge plan increases the likelihood of a positive outcome for the patient.

Regardless of the setting to which the patient is discharged, effective coordination of care begins on day 1 of a hospital or nursing home stay and continues throughout the institutionalization. The patient should be included in every step of the planning process whenever possible to ensure that decisions made by the health care team reflect the desires of the patient.

When needed, the RD refers the patient or client to other caregivers, agencies, or programs for follow-up care or services. For example, use of the home-delivered meal program of the Older Americans Act Nutrition Program has traditionally served frail, homebound, older adults, yet studies show that older adults who have recently been discharged from the hospital may be at high nutritional risk but not referred to this service (Sahyoun et al., 2010). Thus the RD plays an essential role in making the referral and coordinating the necessary follow-up.

Nutrition for the Terminally Ill or Hospice Patient

Maintenance of comfort and quality of life are most typically the goals of nutrition care for the terminally ill patient. Dietary restrictions are rarely appropriate. Nutrition care should be mindful of strategies that facilitate symptom and pain control. Recognition of the various phases of dying—denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance—will help the health care practitioner understand the patient’s response to food and nutrition support.

The decision as to when life support should be terminated often involves the issue of whether to continue enteral or parenteral nutrition. With advance directives, the patient can advise family and health care team members of his or her individual preferences with regard to end-of-life issues. Food and hydration issues may be discussed, such as whether tube feeding should be initiated or discontinued and under what circumstances. Nutrition support should be continued as long as the patient is competent to make this choice (or if specified in the patient’s advance directives).

In advanced dementia, the inability to eat orally can lead to weight loss. One clear goal-oriented alternative to tube feeding may be the order for “comfort feeding only” to ensure an individualized feeding plan (Palecek et al., 2010). Palliative care encourages the alleviation of physical symptoms, anxiety, and fear while attempting to maintain the patient’s ability to function independently.

Hospice home care programs allow terminally ill patients to stay at home and delay or avoid hospital admission. Quality of life is the critical component. Indeed, individuals have the right to request or refuse nutrition and hydration as medical treatment (ADA, 2008). RD intervention may benefit the patient and family as they adjust to issues related to the approaching death. Families who might be accustomed to a modified diet should be reassured if they are uncomfortable about easing dietary restrictions. Ongoing communication and explanations to the family are important and helpful. RDs should work collaboratively to make recommendations on providing, withdrawing, or withholding nutrition and hydration in individual cases and serve as active members of institutional ethics committees (ADA, 2008). The RD, as a member of the health care team, has a responsibility to promote use of advanced directives of the individual patient and to identify their nutritional and hydration needs.

References

American Dietetic Association (ADA). Evidence analysis library. Accessed 5 May 2010 from http://www.adaevidencelibrary.com.

American Dietetic Association (ADA). International nutrition and diagnostic terminology, ed 3. Chicago, Il: American Dietetic Association; 2010.

American Dietetic Association (ADA). Position of the American Dietetic Association: Ethical and legal issues in nutrition, hydration and feeding. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:873.

Ash, J, et al. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2007;14:415.

Backer, LA. The medical home. An idea whose time has come … again. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:38.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 1 November 2010 at https://www.cms.gov/hipaageninfo/.

Demiris, G, et al. Current status and perceived needs of information technology in Critical Access Hospitals. Informatics in Primary Care. 2007;15:45.

Franz, MJ, et al. Evidence-based nutrition practice guidelines for diabetes and scope and standards of practice. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:S52.

Jeffery, KM, et al. The clear liquid diet is no longer necessary in the routine postoperative management of surgical patients. Am J Surg. 1996;62:167.

Ornstein, S, et al. Improving the translation of research into primary care practice: results of a national quality improvement demonstration project. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:379.

Palecek, EJ, et al. Comfort feeding only: a proposal to bring clarity to decision-making regarding difficulty with eating for persons with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:580.

Ross, JS. Health reform redux: learning from experience and politics. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:779.

Sahyoun, NR, et al. Recently hospital-discharged older adults are vulnerable and may be underserved by the Older Americans Act nutrition program. J Nutr Elder. 2010;29:227.

Schifalacqua, M, et al. Roadmap for planned change, part I: change leadership and project management. Nurse Leader. 2009;7:26.

White, JB, et al. Registered dietitians’ coding practices and patterns of code use. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1242.