Pain Assessment and Management in Children

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Communication and Health Assessment of the Child and Family, Ch. 6

Compliance, Ch. 27

Cultural and Religious Influences on Health Care, Ch. 2

Family-Centered Care, Ch. 26

Family-Centered Home Care, Ch. 25

Impact of Chronic Illness, Disability, or Death on the Child and Family, Ch. 23

Nursing Diagnosis, Ch. 1

Physical and Developmental Assessment of the Child, Ch. 6

Preparation for Procedures, Ch. 26

The evidence-based literature on pediatric pain assessment and management grows considerably each year. Pain measurement tools that were developed more than 20 years ago continue to be refined and are becoming available electronically. Available treatment options for pediatric acute and chronic pain are continually being evaluated, and new technologies and administration options become available every day. Unfortunately, despite the advances in acute and chronic pediatric pain management over the past 15 to 20 years, many children and adolescents continue to suffer from inadequately treated pain of all types (Perquin, Hazebroek-Kampschreur, Hunfeld, et al, 2000a, 2000b). Several research studies suggest that the undertreatment of pain in children is related to inconsistent practices in pain assessment, administration of analgesics at subtherapeutic levels, prolonged intervals in between medications, and lack of systematic monitoring and evaluation of relief (Jacob and Puntillo, 2000; Jacob, Miaskowski, and Savedra, et al, 2003a, 2003b; Jacob and Mueller, 2008).

Pain Assessment

![]() The pain experience in children is influenced by the child’s age and developmental level, the cause of the pain, the nature of the pain, and the child’s ability to express the pain in a meaningful way (Box 7-1). Pediatric pain assessment tools need to reflect the variations in children’s cognitive, emotional, and physical capabilities. The family plays an important role in pain assessment. The Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (PedIMMPACT) group recommended six core domains and specific measures to assess and measure pain in children (McGrath, Walco, Turk, et al, 2008). These domains include pain intensity, global judgment of satisfaction with treatment, symptoms and adverse events, physical recovery, emotional response, and economic factors. These domains are discussed for assessment of both acute pain and chronic and recurrent pain.

The pain experience in children is influenced by the child’s age and developmental level, the cause of the pain, the nature of the pain, and the child’s ability to express the pain in a meaningful way (Box 7-1). Pediatric pain assessment tools need to reflect the variations in children’s cognitive, emotional, and physical capabilities. The family plays an important role in pain assessment. The Pediatric Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (PedIMMPACT) group recommended six core domains and specific measures to assess and measure pain in children (McGrath, Walco, Turk, et al, 2008). These domains include pain intensity, global judgment of satisfaction with treatment, symptoms and adverse events, physical recovery, emotional response, and economic factors. These domains are discussed for assessment of both acute pain and chronic and recurrent pain.

![]() Nursing Care Plan—The Child in Pain

Nursing Care Plan—The Child in Pain

Assessment of Acute Pain

Acute pain may be related to medical treatments, surgical procedures, injury, infection, or exacerbations of underlying disease.

Pain Intensity

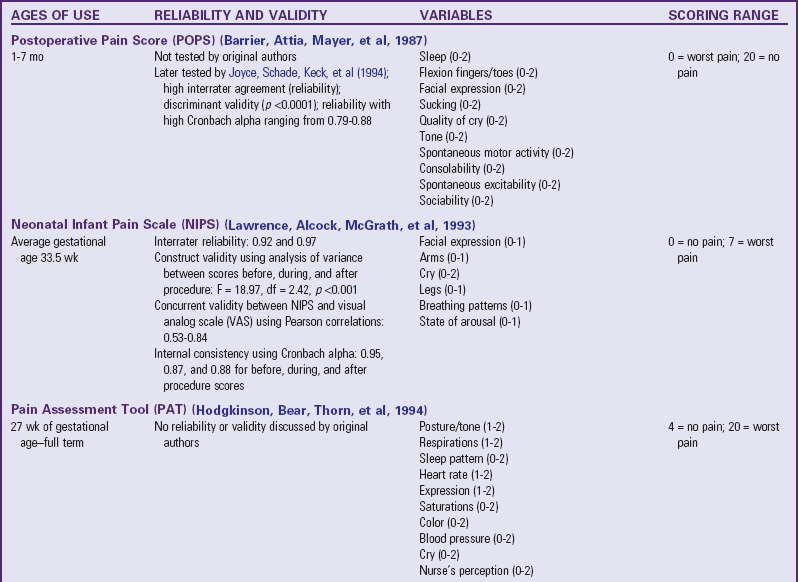

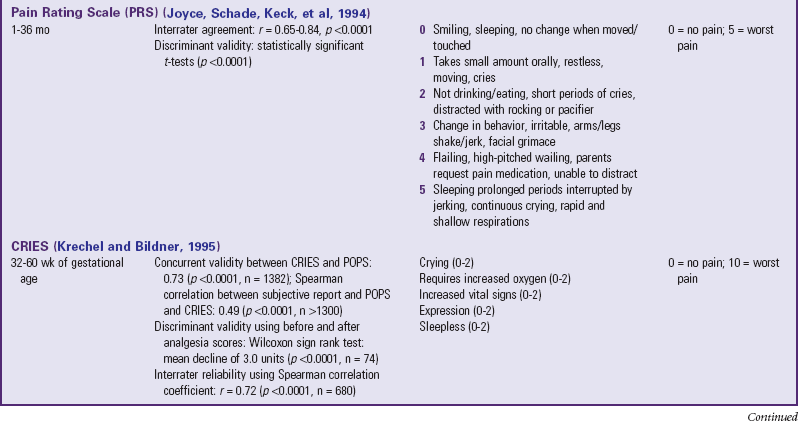

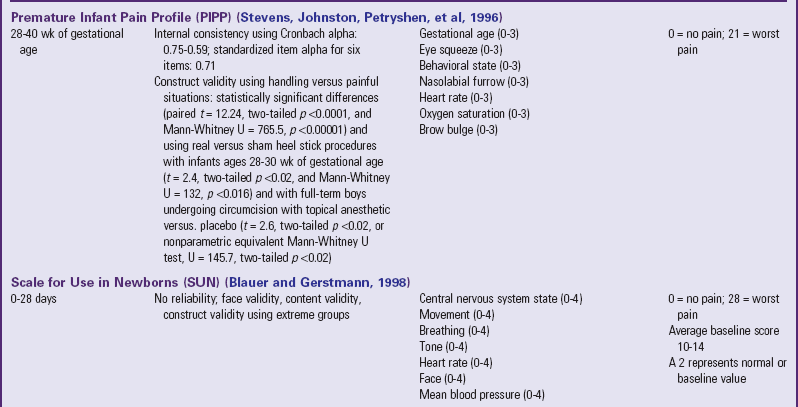

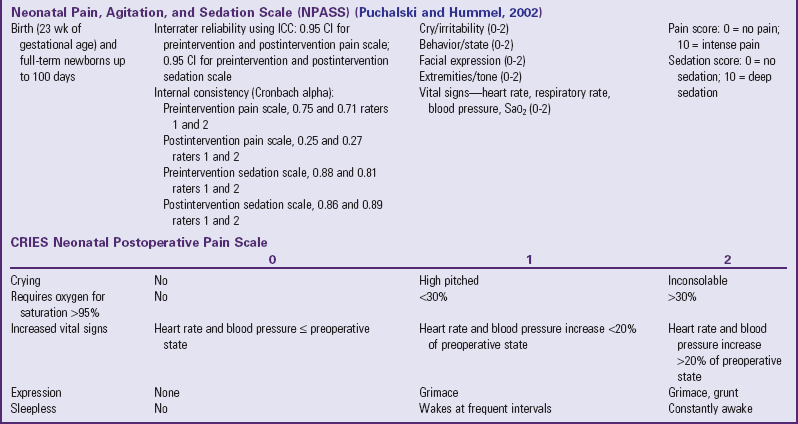

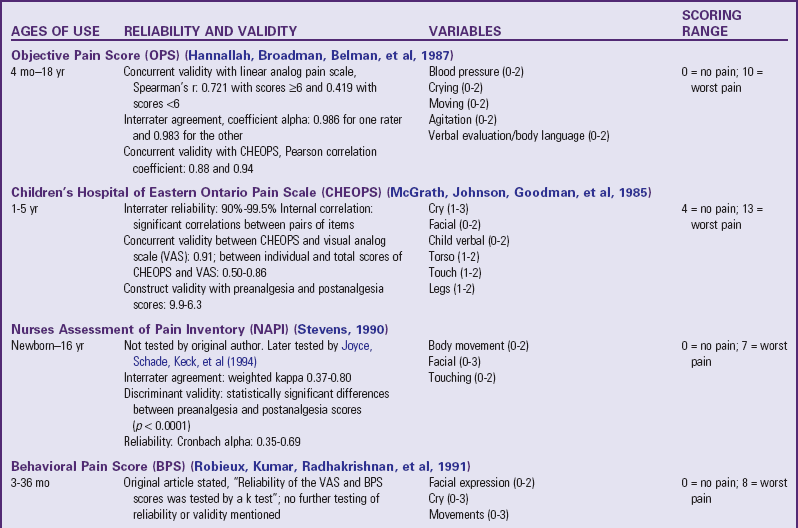

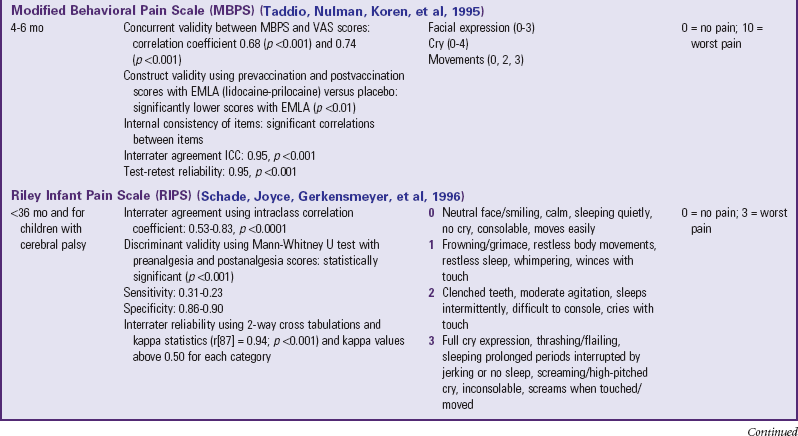

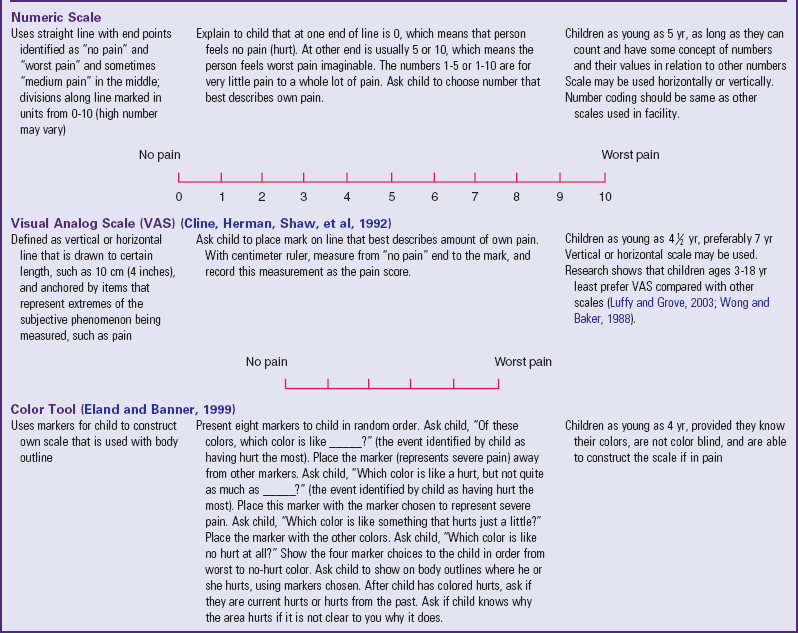

Traditionally, pediatric pain assessment tools are described as being behavioral, physiologic, or self-report and are used predominantly to measure pain intensity. Many pediatric pain assessment tools have been validated and are widely used. Behavioral measures of pain are generally used for children from infancy to age 4 years (Table 7-1), and self-report measures are used for children over 4 years of age (Table 7-2). Self-report measures are not valid for children under 4 years of age because most children under 4 cannot accurately report the intensity of their pain. Distress behaviors, such as vocalization of sounds associated with pain, changes in facial expression, and unexpected or unusual body movements, have been associated with pain (Figs. 7-1 and 7-2). Understanding that these behaviors are associated with pain makes assessing pain in small children with limited communication skills a little easier. However, discriminating between pain behaviors and reactions to other sources of distress, such as hunger, anxiety, or other types of discomfort, is not always easy. These factors decrease the specificity and sensitivity of behavioral measures (see Table 7-1).

TABLE 7-1

SUMMARY OF SELECTED BEHAVIORAL PAIN ASSESSMENT SCALES FOR YOUNG CHILDREN

*From Merkel SI, Voepel-Lewis T, Shayevitz JR, et al: The FLACC: a behavioral scale for scoring postoperative pain in young children, Pediatr Nurs 23(3):293-297, 1997. Used with permission of Jannetti Publications, Inc., and the University of Michigan Health System. Can be reproduced for clinical and research use.

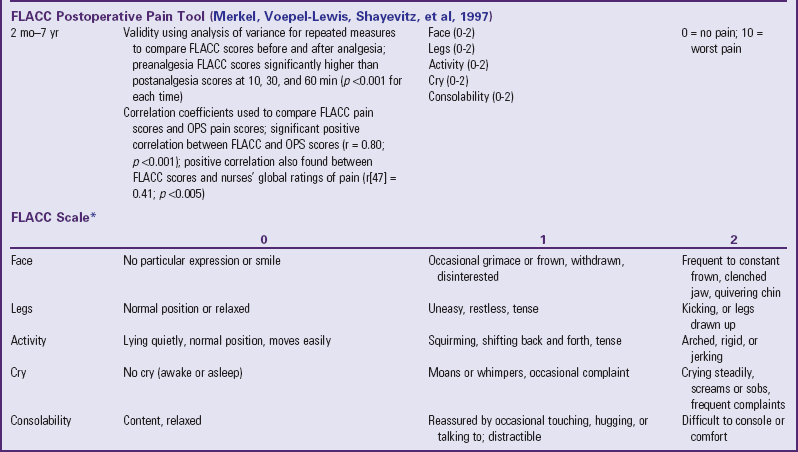

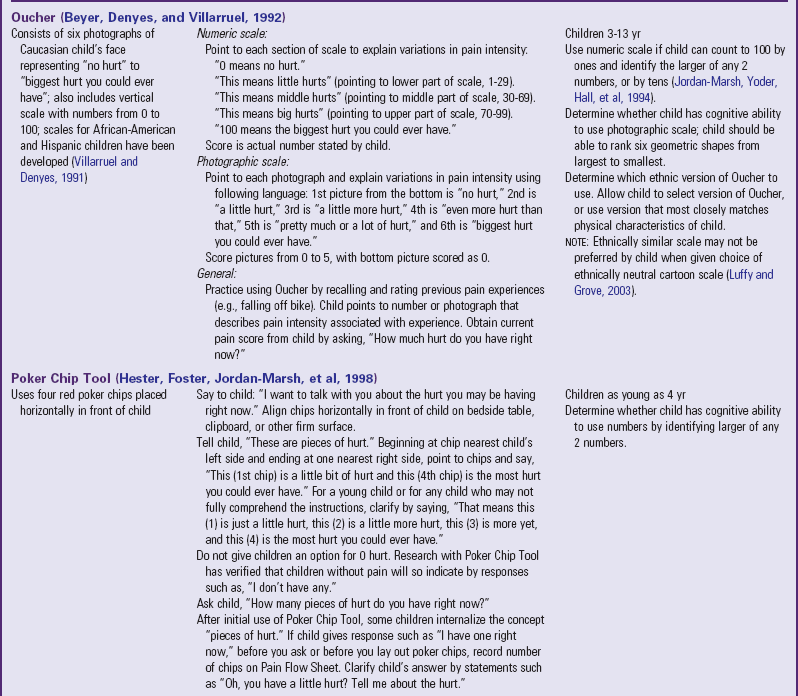

TABLE 7-2

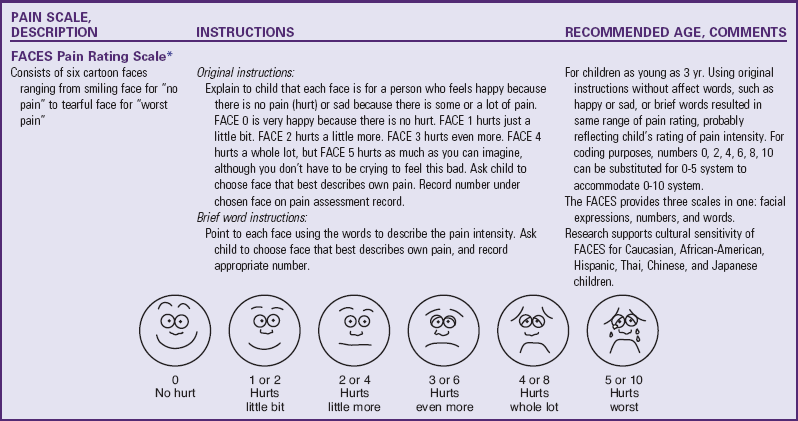

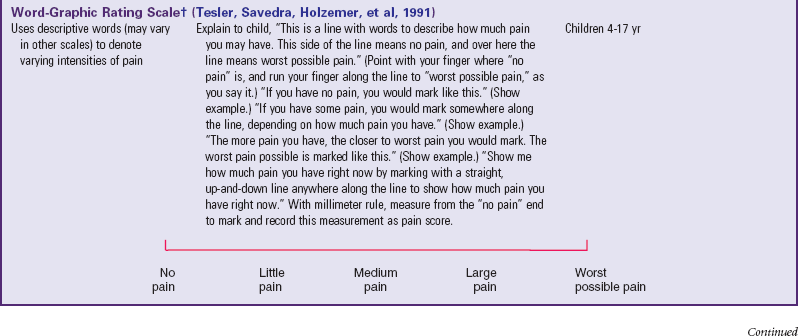

PAIN RATING SCALES FOR CHILDREN

*Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale reference manual describing development and research of the scale is available from City of Hope Pain/Palliative Care Resource Center, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010; 626-359-8111, ext. 3829; fax: 626-301-8941; www1.us.elsevierhealth.com/FACES.

†Instructions for Word-Graphic Rating Scale from Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel: Acute pain management in infants, children, and adolescents: operative and medical procedures; quick reference guide for clinicians, ACHPR Pub. No. 92-0020, Rockville, Md, 1992, Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. Word-Graphic Rating Scale is part of the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool and is available from Pediatric Pain Study, University of California, School of Nursing, Department of Family Health Care Nursing, San Francisco, CA 94143-0606; 415-476-4040.

Fig. 7-1 Full, robust crying of preterm infant after heel stick. (Courtesy Halbouty Premature Nursery, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston; photo by Paul Vincent Kuntz.)

Fig. 7-2 The face of pain after heel stick. Note eye squeeze, brow bulge, nasolabial furrow, and wide-spread mouth. (Courtesy Halbouty Premature Nursery, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston; photo by Paul Vincent Kuntz.)

Behavioral pain assessment may provide a more complete picture of the total pain experience when administered in conjunction with a subjective self-report measure. Behavioral pain measurement tools may be more time consuming than self-reports because they depend on a trained observer to watch and record children’s behaviors such as vocalization, facial expression, and body movements that suggest discomfort. In addition, they are most reliable when used to measure short, sharp procedural pain, such as during injections or lumbar punctures, or when assessing pain in infants. They are less reliable when measuring recurrent or chronic pain and when assessing pain in older children, where pain scores on behavioral measures do not always correlate with the children’s own reports of pain intensity.

The four most commonly used behavioral pain measurement tools are the FLACC, CHEOPS, TPPPS, and PPPRS (see Table 7-1). The FLACC Pain Assessment Tool is an interval scale that includes the five categories of behavior: facial expression (F), leg movement (L), activity (A), cry (C), and consolability (C) (Manworren and Hynan, 2003; Merkel, Voepel-Lewis, Shayevitz, et al, 1997). It measures each behavior on a 0 to 10 scale, with total scores ranging from 0 (no pain behaviors) to 10 (most possible pain behaviors).

The Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Pain Scale (CHEOPS) was developed in collaboration with experienced recovery room nurses who were queried as to what behaviors they most frequently observed to determine whether a child is in pain (McGrath, Johnson, Goodman, et al 1985; Suraseranivongse, Montapaneewat, Manon, et al, 2005). Six categories of behaviors are identified: cry, facial, verbal, torso, touch, and legs. Scoring was devised so that 0 equals behavior that is the antithesis of pain, 1 means the behavior is not indicative of pain and is not the antithesis of pain, 2 indicates behavior consistent with mild or moderate pain, and 3 means the behavior is indicative of severe pain. The range of the total score is 4 to 13.

The Toddler-Preschooler Postoperative Pain Scale (TPPPS) is an observational scale developed for measuring postoperative pain in children ages 1 to 5 years (Suraseranivongse, Montapaneewat, Manon, et al, 2005; Tarbell, Cohen, and Marsh, 1992). It consists of three pain behavior categories: vocal pain expression, facial pain expression, and bodily pain expression. Vocal pain expression includes verbal pain complaints such as crying, screaming, groaning, moaning, and grunting. Facial pain expression includes open mouth with lips pulled back at corners, squinting or closed eyes, furrowed forehead, and brow bulge. Bodily pain is indicated by restless motor behavior when touched in a painful area.

The Parent’s Postoperative Pain Rating Scale (PPPRS) is a scale that parents may use to rate their children’s pain by noting changes in the frequency of a number of behaviors (Chambers, 2003; Chambers and Craig, 1998; Finley, Chambers, McGrath, et al, 2003). The Parents’ Postoperative Pain Measure (PPPM), for use by parents, was developed based on cues parents reported observing in their children after surgery such as changes in appetite and activity level.

The only pain measurement tool recommended for use with children in critical care settings is the COMFORT scale (Ambuel, Hamlett, Marx, et al, 1992). The COMFORT scale is a behavioral, unobtrusive method of measuring distress in unconscious and ventilated infants, children, and adolescents. This scale has eight indicators: alertness, calmness/agitation, respiratory response, physical movement, blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tone, and facial tension. Each indicator is scored between 1 and 5 based on the behaviors exhibited by the patient. The provider observes the patient unobtrusively for 2 minutes and derives the total score by adding the scores of each indicator. The total scores can range between 8 and 40. A score of 17 to 26 generally indicates adequate sedation and pain control.

The PedIMMPACT statement recommends the Poker Chips Tool for children 3 to 4 years of age (Hester, Foster, and Kristensen, 1990), the Faces Pain Scale–Revised for children 4 to 12 years of age (Hicks, von Baeyer, Spafford, et al, 2001) the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for children 8 years and older (Scott, Ansell, and Huskisson, 1977).

The Poker Chip Tool consists of a set of four red plastic poker chips. Each chip is used to denote a “piece of hurt,” and the child is asked to choose “how many pieces of hurt do you have right now?” The child responds that he or she does not have any pieces of hurt, or one chip corresponds to “a little hurt,” the second chip indicates “a little more hurt,” the third chip means “more hurt,” and the fourth chip equals the “most hurt you could ever have.” The scores range from 0 to 4. The Poker Chip Tool has undergone extensive psychometric testing by various teams of investigators (Gharaibeh and Abu-Saad 2002; Goodenough, Addicoat, Champion, et al, 1997; Suraseranivongse, Montapaneewat, Manon, et al, 2005).

There are many different “faces” scales for the measurement of pain intensity. Although children who are 4 or 5 years old are able to use self-report measures, cognitive characteristics of the preoperational stage influence their ability to use these scales. Simple, concrete anchor words, such as “no hurt” to “biggest hurt,” are more appropriate than “least pain sensation to worst intense pain imaginable.” The ability to discriminate degrees of pain in facial expressions appears to be reasonably established by 3 years of age (see Table 7-2). Faces scales provide a series of facial expressions depicting gradations of pain. The faces are appealing because children can simply point to the face that represents how they feel.

The Bieri Faces Pain Scale–Revised (Hicks, von Baeyer, Spafford, et al, 2001) and the WB FACES Pain Scale (Wong and Baker, 1988) are the most widely used faces pain measurement tools. The Bieri scale consists of six faces depicting increasing gradation of pain severity from 0 = “no pain” on the left face to 5 = “most pain possible” on the right face. In developing this scale, the authors did not include a smiling face at the “no pain” end or tears at the “most pain” end and validated it so that it is equivalent to a 0 to 10 metric system. The WB FACES Pain Scale consists of six cartoon faces ranging from a smiling face for “no pain” to a tearful face for “worst pain.” The child is asked to choose a face that describes his or her pain. Although the PedIMMPACT group recommended the Faces Pain Scale–Revised, most children prefer the WB FACES Pain Scale (Chambers, Giesbrecht, Craig, et al, 1999; Keck, Gerkensmeyer, Joyce, et al, 1996; Luffy and Grove, 2003; West, Oakes, Hinds, et al, 1994). The WB FACES pain scale is widely used in children’s hospitals across the United States.

For children 8 years and older, the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), specifically the 0 to 10 scale, is most widely used in clinical practice because it is easy to use. However, there is little research to support the reliability and validity of the NRS, except in the context of the Oucher Pain Scale (Beyer, Turner, Jones, et al, 2005) (see Table 7-2). Although the VAS requires a higher degree of abstraction than the NRS, the PedIMMPACT group recommends the VAS because of the lack of supportive evidence through psychometric studies with the NRS in children and adolescents.

Global Judgment of Improvement and of Satisfaction with Treatment

Patients or patient surrogates may provide a collection of their perspective of all aspects of the treatment experience by allowing them to rate a global judgment of satisfaction with treatment. Patient or parent global judgments focus on the patient’s experience. The ratings will mean something different from one patient or surrogate to another. Although some may focus on the relief of pain, others may consider side effects of the treatment. The global question should be specific so the patient is able to give a focused response in the answer. For example, a focused global question would read, “Considering pain relief, side effects, physical recovery, and emotional recovery, how satisfied were you with the intervention your child received for pain?”

Adverse Events and Symptoms

Treatment-emergent adverse events refer to signs, symptoms, laboratory findings, or diseases that occur after medications for pain are initiated. Constipation is the most common adverse event associated with prolonged opioid use, yet is not commonly screened for in children with pain. There is no particular strategy to measure either the occurrence or severity of treatment-emergent adverse events. Children older than 10 years may be able to provide this information. In younger children the nurse must be extra vigilant and should ask parents or caregivers about any perceived adverse events and symptoms.

Physical Recovery

The domain of physical recovery includes those aspects of physical functioning that are influenced by the procedure or injury causing acute pain. Assessments of the physical recovery would include time to ambulation, time to resume swallowing, time to normal spirometry, return to normal nutritional intake, and time out of bed. However, measures such as tolerance of physical therapy may be inconsistent. One child may be intolerant of physical therapy because he or she did not want to participate, whereas another child might be considered intolerant of physical therapy if the therapy was associated with pain, profuse crying, and refusal to do the work. The PedIMMPACT group recommends assessing existing measures of physical recovery for the purposes of evaluating interventions to control pain following procedures and injuries that have specific effects on physical functioning.

Emotional Response

The domain of emotional response includes all aspects of negative affect or distress secondary to pain such as anxiety, depression, fear, distress, dysphoria, or unhappiness. Behaviors indicating avoidance, withdrawal, or resistance need to be assessed. In children 8 years and older, the PedIMMPACT group recommends the use of the Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool (APPT) (Savedra, Holzemer, Tesler, et al, 1993), which allows children to describe the quality of the pain using a word list. The 56 words are grouped according to sensory, affective, and evaluative qualities of pain. This measurement tool has been validated.

Assessment of Chronic and Recurrent Pain

Pain that persists for 3 months or more or beyond the expected period of healing is defined as chronic pain. Complex regional pain syndrome and chronic daily headache are the most common types of chronic pain conditions in children. Pain that is episodic and recurs is defined as recurrent pain. The time frame within which episodes of pain recur is at least 3 months. Recurrent pain syndromes in children include migraine headache, episodic sickle cell pain, recurrent abdominal pain, and recurrent limb pain (see Research Focus box).

Chronic or recurrent pain adversely affects the psychosocial and physical well-being of children. The domains for the assessment of chronic or recurrent pain are the same for acute pain (pain intensity, global judgment of satisfaction with treatment, symptoms and adverse events, physical functioning, emotional functioning, economic factors), plus two additional domains: role functioning and sleep. Because the time course of chronic or recurrent pain is different from that of acute pain, measures used to assess chronic pain often evaluate the symptom over time.

Pain diaries are commonly used to assess pain symptoms and response to treatment in children and adolescents with recurrent or chronic pain (Ely, Dampier, Gilday, et al, 2002; Dampier, Ely, Brodecki, et al, 2002a, 2002b; Stinson, Stevens, Feldman, et al, 2008; Palermo and Valenzuela, 2003; Palermo, Valenzuela, and Stork, 2004; Stone, Broderick, Schwartz, et al, 2003). Most pain diaries use NRS or VAS with varying anchors such as faces scales or words. Diary studies have included children as young as 6 years. Conventional paper-and-pencil measures have been associated with several limitations such as poor compliance, missing data, hoarding of responses, and back and forward filling (Palermo and Valenzuela, 2003; Stone, Broderick, Schwartz, et al, 2003) (see Research Focus box).

The PedIMMPACT group recommends the same approach for measuring global judgment of satisfaction with treatment of symptoms and adverse events. The physical functioning domain in chronic or recurrent pain is focused on activities of everyday life, such as sitting or walking, or on more vigorous activities such as running and other sports. The recommendation is to use a measure such as the functional disability inventory (FDI) (Walker and Greene, 1991) for assessing physical functioning in school-age children and adolescents. The FDI assesses the child’s ability to perform everyday physical activities and has established psychometric properties with different populations (Claar and Walker, 2006; Reid, Lang, and McGrath, 1997; Vervoort, Goubert, Eccleston, et al, 2006). For children less than 7 years of age the Pediatric Quality of Life Scale (PedsQL), developed by Varni, Seid, and Rode (1999), is a multidimensional scale with both parent and child versions that is recommended for assessing physical, emotional, social, and academic functioning as they relate to the child’s pain. The PedsQL and the PedMIDAS (Hershey, Powers, Vockell, et al, 2001, 2004) have been validated for measurement of role functioning in children with chronic or recurrent pain.

The emotional functioning domain most often refers to the presence of depression or anxiety, which may be more prevalent in children with chronic or recurrent pain (Palermo, 2000). The Children’s Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1981) and the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (Chorpita, Yim, Moffitt, et al, 2000) have been used to assess anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with chronic or recurrent pain. Fortunately, most children with chronic or recurrent pain do not experience clinical levels of anxiety or depression.

Sleep disruption is also common in those with chronic or recurrent pain. More than half of children with pain-related conditions report difficulties sleeping (Walters and Williamson, 1999; Palermo and Kiska, 2005). A sleep diary can be useful in keeping a record of activities surrounding sleep, including bed time, time to fall asleep, number of night awakenings, waking in the morning, and especially any pain or other circumstance that interfered with sleeping. The sleep diary was validated using sleep actigraphy in healthy children ages 13 and 14 years (Gaina, Sekine, Chen, et al, 2004). The Sleep Habits Questionnaire (Owens, Spirito, and McGuinn, 2000) may be useful for assessing sleep behaviors in school-age children with chronic or recurrent pain.

Multidimensional Measures

The number of pain measures available for use in infants, young children, and adolescents has increased dramatically and adds a layer of complexity to the assessment of pain in children. The current trend supports a common metric for measurement of pain in children (von Baeyer and Hicks, 2000). Most instruments consist of 0 for no pain to a range of 4 to 160 for the top anchors in pain measures. A pain score of 5 may mean a lot of pain (if a 0 to 5 scale is used) or very little (if a 0 to 100 scale is used), and it may not be clearly specified which score corresponds to which scale. Other health care providers who do not specialize in pediatric pain may be confused by the available instruments and scoring methods and may not be able to determine the effectiveness of interventions by the pain score documented. An advantage to using a common metric is that a certain score may be considered as the point at which an intervention is required, or a point at which relief may be considered adequate (von Baeyer and Hicks, 2000). The 0 to 10 system was reported to be preferred by health care providers and would make pain scores easier to read, interpret, and integrate into research and practice.

Several cognitive skills, such as measurement, classification, and seriation (the ability to accurately place in ascending or descending order), become apparent between 7 and 10 years of age. Older children are able to use a 0 to 10 NRS used by adolescents and adults. However, the use of the 0 to 10 NRS is only an assessment of pain intensity, which may not change in some pain states (Jacob, Miaskowski, Savedra, et al, 2003a, 2003b). Other dimensions such as pain quality, pain location, and spatial distribution of pain may change without a change in pain intensity.

Two multidimensional assessment tools have been well validated for children 8 years and older. The APPT, modeled after the McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack, 1975), is a multidimensional pain measurement instrument used with children and adolescents to assess pain location, intensity, and quality (Fig. 7-3). The APPT is an instrument with an anterior and posterior body outline on one side and a 100-mm word-graphing rating scale with a pain descriptor on the other side (Savedra, Tesler, Holzemer, et al, 1989; Wilkie, Holzemer, Tesler, et al, 1990; Tesler, Savedra, Holzemer, et al, 1991; Savedra, Holzemer, Tesler, et al, 1993). Each of the three components of the APPT is scored separately. The body outline is scored by placing a clear plastic template overlay with 43 body areas on the body outline diagram. An estimate of the pervasiveness of the pain is made by counting the number of body areas marked. A ruler or micrometer preprinted on the APPT is used to score the word-graphic rating scale. The number of millimeters from the left side of the scale to the point marked by the child is measured; and the numeric value provides an overall evaluation of the amount of pain the child is experiencing. The total number of words on the descriptor list is counted, and scores range from 0 to 56. The clinician then counts the number of words selected in each of three categories—evaluative (0-8), sensory (0-37), and affective (0-11)—and calculates a percentage score for each one (Savedra, Holzemer, Tesler, et al, 1993).

Fig. 7-3 Adolescent Pediatric Pain Tool: body outlines for pain assessment. Instructions: “Color in the areas on these drawings to show where you have pain. Make the marks as big or as small as the place where the pain is.” Tool has been completed by a child with sickle cell disease. (From Savedra MC, Tesler MD, Holzemer WL, Ward JA, School of Nursing, University of California–San Francisco; copyright 1989, 1992.)

An advantage to using the APPT is that, in some pain states, pain intensity ratings do not change, but pain location and spatial distribution of pain may decrease over time (Jacob, Miaskowski, Savedra, et al, 2003a, 2003b). The total surface area may decrease, but some children may perceive the remaining sites as equal in pain intensity. In addition to pain location, assessments of pain quality may be able to distinguish the presence of the different dimensions of pain (temporal, affective, evaluative, and sensory). Words may not be quantifiable on an NRS, yet represent the pain experience, such as horrible and terrible from the evaluative dimension, screaming and terrifying from the affective dimension, or sharp and stabbing from the sensory dimension. The different qualities of pain may also represent whether pain is of an ischemic and inflammatory nature in the cutaneous, subcutaneous, and musculoskeletal tissues, as opposed to pain that is more neuropathic, which may be described using words such as shooting, burning, or shocklike (McCaffery and Pasero, 1999).

The Pediatric Pain Questionnaire (PPQ) is a multidimensional pain instrument to assess patient and parental perceptions of the pain experience in a manner appropriate for the cognitive-developmental level of children and adolescents. The PPQ consists of eight areas of inquiry: pain history, pain language, the colors children associate with pain, emotions children experience, the worst pain experiences, the ways they cope with pain, the positive aspects of pain, and the location of their current pain. The three components of the PPQ include VASs; color-coded rating scales; and verbal descriptors to provide information about the sensory, affective, and evaluative dimensions of chronic pain (Varni, Thompson, and Hanson, 1987). There is also information about the child and family’s pain history, symptoms, pain relief interventions, and socioenvironmental situations that may influence pain. The child, parent, and physician each complete the form separately.

Assessment of Pain in Specific Populations

Assessment of pain in the preverbal child is difficult, especially in the neonate, since the most reliable indicator of pain, self-report, is not possible. Evaluation must be based on physiologic changes and behavioral observations (Box 7-2). Although behaviors such as vocalizations, facial expressions, body movements, and general relaxation state are common to all infants, they vary with different situations. Crying associated with pain is more intense and sustained (see Fig. 7-1). Facial expression is the most consistent and specific characteristic; scales are available to systematically evaluate facial features, such as eye squeeze, brow bulge, open mouth, and taut tongue (Hadjistavropoulos, Craig, Grunau, et al, 1997). Most infants respond with increased body movements, but the infant may be experiencing pain even when lying quietly with eyes closed. The preterm infant’s response to pain may be behaviorally blunted or absent; however, there is ample evidence that such infants are neurologically capable of feeling pain. In addition, infants in awake or alert states demonstrate a more robust reaction to painful stimuli than infants in sleep states. Also, an infant receiving a muscle-paralyzing agent (vecuronium) is incapable of a behavioral or visible pain response.

Although regular use of pain assessment tools can assist caregivers in determining whether the infant is in pain, caregivers must consider the infant’s maturity, behavioral state, energy resources available to respond, and risk factors for pain. In infants with diminished ability to respond robustly to pain, it is imperative to presume that pain exists in all situations that are usually considered painful for adults and children, even in the absence of behavioral or physiologic signs (Sweet and McGrath, 1998).

Several pain assessment tools for neonates have been developed (Table 7-3). One tool used by nurses who work with premature and full-term infants in the neonatal intensive care setting is called CRIES, which is an acronym for the tool’s physiologic and behavioral indicators of pain: Crying, Requiring increased oxygen, Increased vital signs, Expression, and Sleeplessness. Each indicator is scored from 0 to 2, with a total possible pain score, representing the worst pain, of 10. A pain score greater than 4 is considered significant. This tool has been tested for reliability and validity for postoperative pain in infants between the ages of 32 weeks of gestation up to 20 weeks postterm (60 weeks) (Sweet and McGrath, 1998).

The Premature Infant Pain Profile (PIPP) was developed specifically for preterm infants (Sweet and McGrath, 1998). The category “gestational age at time of observation” gives a higher pain score to infants with lower gestational age. Infants who are asleep 15 seconds before the painful procedure also receive additional points for their blunted behavioral responses to painful stimuli.

The Neonatal Pain, Agitation, and Sedation Scale (NPASS) was originally developed to measure pain or sedation in preterm infants after surgery. It measures five criteria (see Table 7-3) in two dimensions (pain and sedation) and is used in neonates as young as 23 weeks of gestation up to infants 100 days old. Extra points are added in the pain scale dimension for preterm infants based on gestational age.

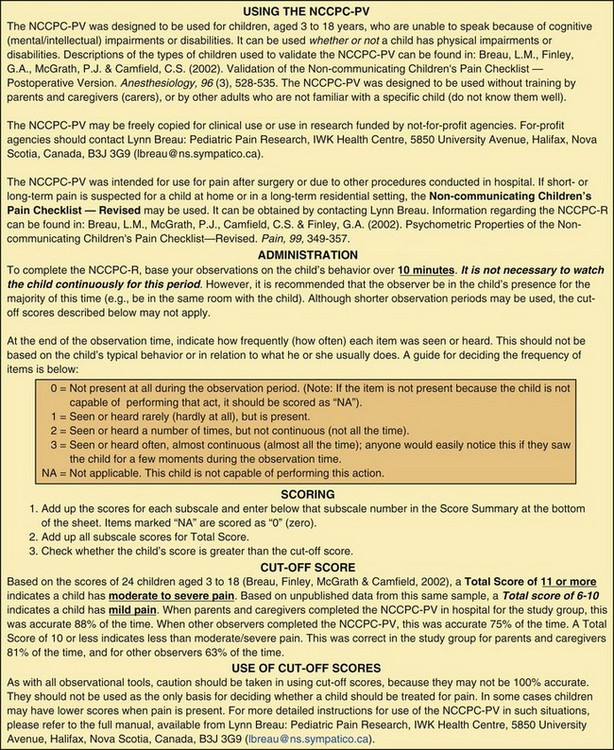

Children with Communication and Cognitive Impairment

The assessment of pain in children with communication and cognitive impairment can be challenging. Children who have significant difficulties in communicating with others about their pain include those who have significant neurologic impairments (e.g., cerebral palsy), cognitive impairment, metabolic disorders, autism, severe brain injury, and communication barriers (e.g., critically ill children who are on ventilators or heavily sedated or have neuromuscular disorders, loss of hearing, or loss of vision) and consequently are at greater risk for undertreatment of pain. Children with communication and cognitive deficits often experience spasticity, contractures, injury, infection, and orthopedic surgical treatment that may be painful. Behaviors include moaning, inconsistent patterns of play and sleep, changes in facial expression, and other physical problems that may mask expression of pain and be difficult to interpret (Hadden and von Baeyer, 2002).

The mother or primary caregiver may be the most important source of information when assessing pain in children with developmental delays (Breau, MacLaren, McGrath, et al, 2003). Stallard, Williams, Lenton, and colleagues (2001) asked the parents of cognitively impaired and noncommunicative children to assess the presence, severity, and duration of their pain during a 2-week observation period. Parents reported that 84% experienced pain on 5 or more separate days, with 32% experiencing pain on 12 or more days. Of the 74 episodes that lasted longer than 30 minutes, 33.8% occurred at night. Most pain episodes lasted longer than 10 minutes, with 48% of the children having episodes lasting longer than 10 minutes on 5 or more days. Although the experience of pain was common among this group of children, none was receiving treatment for relief or management of pain (see Research Focus box).

The Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist (NCCPC) is a pain measurement tool specifically designed for children with cognitive impairments (Breau, McGrath, Camfield, et al, 2002). The scale discriminates between periods of pain and calm and can predict behavior during subsequent episodes of pain (Fig. 7-4). The scale consists of six subscales (vocal, social, facial, activity, body and limbs, physiologic signs), which are scored based on the number of times the items are observed over a 10-minute period (0 = not at all; 1 = just a little; 2 = fairly often; 3 = very often).

Fig. 7-4 Non-communicating Children’s Pain Checklist. (Copyright 2004, Lynn Breau, Patrick McGrath, Allen Finley, and Carol Camfield. Reprinted with permission.)

The Pain Indicator for Communicatively Impaired Children (PICIC) distinguishes between pain and nonpain in children with life-threatening illness who have communication challenges (Stallard, Williams, Velleman, et al, 2002). The PICIC has six core pain cues: crying with or without tears; screaming, yelling, groaning, or moaning; screwed up or distressed looking face; body appearing stiff or tense; difficulty in comforting or consoling; and flinching or moving away if touched. The items are rated using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = often, 4 = all the time).

Cultural Differences

A major challenge in the assessment and management of pain in children is the cultural appropriateness of pain assessment tools that have been validated only in Caucasian and English-speaking children (see Cultural Competence box). Cultural background may influence the validity and reliability of pain assessment tools developed in a single cultural context (Bernstein and Pachter, 2003).

The Oucher Pain Scale (see Table 7-2), originally developed and validated as a self-report of pain intensity for Caucasian children 3 to 12 years old, now features photographs of children who more closely match the physical characteristics of African-American and Hispanic children (Beyer and Knott, 1998). The Oucher Faces Pain Scale consists of six photographs on the right side and a 0 to 100 scale on the left side. The photographs show the face of one child with the pictures arranged to show increasing levels of discomfort. Each version has been tested primarily with children in each ethnic group. Children use the Oucher by selecting a photograph or number that most closely represents the level of pain intensity they are experiencing (Beyer and Knott, 1998). These tools address cultural issues in accuracy of pain assessment and were designed to promote cultural sensitivity and self-esteem for minority, non-Caucasian children.

A comparison of surgery-related experiences in 25 African-American and 30 Caucasian children showed no significant difference in self-report of pain (Bohannon, 1995). However, physiologic parameters were found to be higher and behavioral distress scores lower in African-American children. Lower levels of analgesia and higher pain tolerance were also reported in a sample of Chinese pediatric burn and surgical (herniorrhaphy and appendectomy) patients compared with levels common for children in Western countries with comparable injuries or procedures (Hu, Zhang, and Chen, 1991a, 1991b).

The APPT also has a Spanish version (Van Cleve, Muñoz, Bossert, et al, 2001) that has been used in children and adolescents with cancer (Jacob and Mueller, 2008; Van Cleve, Bossert, Beecroft, et al, 2004).

There are several documented barriers to effective pain treatment in non–English speaking patients, including inadequate assessment of pain, concern about side effects of and tolerance to analgesics, patient and family reluctance to report pain, fear that pain means worse disease, reluctance to take pain medications, and lack of adherence to prescribed analgesics (Abbe, Simon, Angiolillo, et al, 2006; Bruera, Willey, Ewert-Flannagan, et al, 2005; Flores and Vega, 1998; Flores, Abreu, Olivar, et al, 1998). Non–English speaking patients pose additional language and cultural barriers that make pain assessment and treatments more challenging (see Research Focus box). To minimize the risk of undertreatment of pain, clinicians may give non–English speaking children and adolescents the body outline diagram of the APPT and encourage them to use the diagram for communicating the location and extensiveness of pain (Jacob and Mueller, 2008).

Children with Chronic Illness and Complex Pain

Questionnaires and pain assessment scales do not always provide the most meaningful means of assessing pain in children, particularly for those with complex pain. Some children cannot relate to a face or a number that describes their pain. Other children, such as those with cancer, are experiencing multiple symptoms and may find it difficult to isolate the pain from other symptoms. Rating the pain does not always accurately convey to others how they really feel (Woodgate and Yanofsky, 2004).

The most important aspect of pain assessment for children with chronic illness, particularly those with complex pain, is the relationship that develops between the child and the family. This relationship offers health care providers a sense of what the pain experience means to the child and family. The pain experience can interfere with the child’s ability to eat, sleep, and perform daily activities and routines (Miaskowski and Lee, 1999; Morin, Gibson, and Wade, 1998) and may be complicated by pain processes that occur in the central nervous system, side effects of medical treatments, and complications associated with disease management.

Other important components of assessment include the onset of pain; pain duration or pattern; the effectiveness of the current treatment; factors that aggravate or relieve the pain; other symptoms and complications concurrently felt; and interference with the child’s mood, function, and interactions with family (McCaffery and Pasero, 1999). In addition to asking the child or parent when the pain started and how long the pain lasts, the nurse can assess variations and rhythms by asking whether the pain is better or worse at certain times of the day or night. If the child has had pain for a while, the child or parent may know which medications and doses are helpful. They may also have found some nonpharmacologic methods that have helped. The nurse may ask the child or parent if there are activities, positions, and other events that may increase the pain. Pain may be accompanied by other symptoms such as nausea and poor appetite, and it may interfere with sleep and other activities.

Other aspects warranting careful assessment that may pose barriers to effective management include family issues and relationships, fears and concerns about addictions (see Community Focus box, p. 211), the clinician’s and family’s lack of knowledge about pain, inappropriate use of pain medications, ineffective management of adverse effects from medications, and the use of different modalities (McCaffery and Pasero, 1999).

Pain Management

![]() Children may experience pain as a result of surgery, injuries, acute and chronic illnesses, and medical or surgical procedures. Unrelieved pain may lead to potential long-term physiologic, psychosocial, and behavioral consequences (Goldschneider and Anand, 2003; Weisman, Bernstein, and Schechter, 1998). Management of pain should be a priority for all pediatric health care providers.

Children may experience pain as a result of surgery, injuries, acute and chronic illnesses, and medical or surgical procedures. Unrelieved pain may lead to potential long-term physiologic, psychosocial, and behavioral consequences (Goldschneider and Anand, 2003; Weisman, Bernstein, and Schechter, 1998). Management of pain should be a priority for all pediatric health care providers.

Nonpharmacologic Management

Pain is often associated with fear, anxiety, and stress. ![]() A number of nonpharmacologic techniques, such as distraction, relaxation, guided imagery, and cutaneous stimulation, can help with pain control (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). It is also important to provide coping strategies that help reduce pain perception, make pain more tolerable, decrease anxiety, and enhance the effectiveness of analgesics or reduce the dosage required (Rusy and Weisman, 2000). Techniques decrease the perceived threat of pain, provide a sense of control, enhance comfort, and promote rest and sleep (McCaffery and Pasero, 1999). Despite a paucity of research on the effectiveness of many of these interventions, the strategies are safe, noninvasive, and inexpensive, and most are independent nursing functions. Environmental and psychologic factors may exert a powerful influence on children’s pain perceptions and may be modified by using psychosocial strategies, education, parental support, and cognitive-behavioral interventions. For children undergoing repeated painful procedures, cognitive-behavioral interventions are effective for decreasing anxiety and distress (McGrath and Hillier, 2003).

A number of nonpharmacologic techniques, such as distraction, relaxation, guided imagery, and cutaneous stimulation, can help with pain control (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). It is also important to provide coping strategies that help reduce pain perception, make pain more tolerable, decrease anxiety, and enhance the effectiveness of analgesics or reduce the dosage required (Rusy and Weisman, 2000). Techniques decrease the perceived threat of pain, provide a sense of control, enhance comfort, and promote rest and sleep (McCaffery and Pasero, 1999). Despite a paucity of research on the effectiveness of many of these interventions, the strategies are safe, noninvasive, and inexpensive, and most are independent nursing functions. Environmental and psychologic factors may exert a powerful influence on children’s pain perceptions and may be modified by using psychosocial strategies, education, parental support, and cognitive-behavioral interventions. For children undergoing repeated painful procedures, cognitive-behavioral interventions are effective for decreasing anxiety and distress (McGrath and Hillier, 2003).

![]() Evidence-Based Practice—Nonpharmacologic Interventions During Painful Procedures

Evidence-Based Practice—Nonpharmacologic Interventions During Painful Procedures

If the child cannot identify a familiar coping technique, the nurse can describe several strategies and let the child select the most appealing one. Experimentation with several strategies that are suitable to the child’s age, pain intensity, and abilities is often necessary to determine the most effective approach. Parents should be involved in the selection process; they may be familiar with the child’s usual coping skills and can help identify potentially successful strategies. Involving parents also encourages their participation in learning the skill with the child and acting as coach. If the parent cannot assist the child, other appropriate persons may include a grandparent, older sibling, nurse, or child-life specialist (McGrath and Hillier, 2003).

Children should learn to use a specific strategy before pain occurs or before it becomes severe. To reduce the child’s effort, instructions for a strategy, such as distraction or relaxation, can be audiotaped and played during a period of comfort. However, even after they have learned an intervention, children often need help using it during a painful procedure. The intervention can also be used after the procedure. This gives the child a chance to recover, feel mastery, and cope more effectively (McGrath and Hillier, 2003).

Several studies have documented the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic analgesia, such as containment, positioning, nonnutritive sucking, and kangaroo holding, in neonates during painful procedures. Containment is achieved through positioning and blanket rolls (Cole and Jorgensen, 1997). It provides a “nest” that enhances the infant’s feelings of security and decreases stress. Comforting measures and swaddling reduce crying and heart rate after procedures such as heel punctures and injections (see Research Focus box).

Nonnutritive sucking (pacifier) (Fig. 7-5) reduces behavioral, physiologic, and hormonal responses to pain from procedures, such as heel punctures, venipuncture, and immunization injections. The administration of concentrated sucrose with or without nonnutritive sucking has calming and pain-relieving effects for invasive procedures in neonates (see Evidence-Based Practice box). In one study the amount of time crying was decreased with 0.24 to 0.48 g (0.008 to 0.17 oz) (2 ml of a 12% to 24% sucrose solution) administered orally 2 minutes before a heel lance or venipuncture (Stevens, Yamada, and Ohlsson, 2005).

Fig. 7-5 Sucking following oral sucrose can enhance analgesia before a heel stick in a preterm infant.

Kangaroo care is a skin-to-skin holding of infants dressed only in diapers against their mother’s or father’s chest (Gray, Watt, and Blass, 2000; Johnston, Stevens, Pinelli, et al, 2003). Infants who spent 1 to 3 hours in kangaroo care showed increased frequency in quiet sleep, longer duration of quiet sleep, and decreased crying in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and they cried less at the age of 6 months when compared with neonates who did not receive skin-to-skin contact (see Research Focus box).

In another study, infant responses to pain during heel lance procedures were studied using kangaroo holding (Fig. 7-6), with the neonate held upright at a 60-degree angle between the mother’s breasts for maximal skin-to-skin contact (Johnston, Stevens, Pinelli, et al, 2003). A blanket was placed over the neonate’s back, and the mother’s clothes were wrapped around the neonate for 30 minutes before the lancing procedure, during, and at least 30 minutes after the heel stick. Another group remained in the isolette in a prone position, swaddled with a blanket and the heel accessible, for 30 minutes before the heel lancing procedure. Pain scores were significantly lower in kangaroo-held infants.

Complementary Pain Medicine

Many terms are used to describe approaches to health care that are outside the realm of conventional medicine as practiced in the United States. Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), as defined by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, is a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not currently considered part of conventional medicine (Myers, Stuber, Bonamer-Rheingans, et al, 2005) (see Complementary and Alternative Therapy box). Although some scientific evidence exists regarding some CAM therapies, for most, key questions are yet to be answered through well-designed scientific studies—questions such as whether these therapies are safe and whether they work for the diseases or medical conditions for which they are used.

Current estimates of pediatric CAM use range from 10% to 15%, derived from children sampled at health care facilities, children with chronic conditions, and/or use in countries other than the United States. For the U.S. population, pediatric CAM use was estimated to be 31% to 84% (Myers, Stuber, Bonamer-Rheingans, et al, 2005; Rusy and Weisman, 2000). Those who used CAM were found in each age-group, and the mean age was 10.3 years. The majority used unconventional therapy for chronic, as opposed to life-threatening, medical conditions. The therapies that are increasingly used include herbal medicine, massage, megavitamins, self-help groups, folk remedies, energy healing, and homeopathy (Myers, Stuber, Bonamer-Rheingans, et al, 2005; Rusy and Weisman, 2000).