Communication and Physical Assessment of the Child

Guidelines for Communication and Interviewing

General Approaches Toward Examining the Child

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Wong/ncic/

External and Internal Structures of the Nose

External, Middle, and Inner Ear

Imaginary Landmarks of the Chest

Interior Structures of the Mouth

Altered States of Consciousness, Ch. 37

Assessment of Cardiac Function, Ch. 34

Biologic Development, Ch. 19

Dental Disorders, Ch. 18

Family Structure and Function, Ch. 3

Hearing Impairment; Visual Impairment, Ch. 24

Idiopathic Scoliosis, Ch. 39

Immunizations, Ch. 12

Neurologic Examination, Ch. 37

Pain Assessment, Ch. 7

Physical Assessment (Newborn), Ch. 8

Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, Ch. 27

Sex Education: Preschooler, Ch. 15; School-Age Child, Ch. 17; Sexual Behavior, Ch. 19

Sexually Transmitted Diseases, Ch. 20

Skin Lesions, Ch. 18

Social, Cultural, and Religious Influences on Child Health Promotion, Ch. 2

Systemic Hypertension, Ch. 34

Use of Play in Procedures, Ch. 27

Guidelines for Communication and Interviewing

The most widely used method of communicating with parents on a professional basis is the interview process. Unlike social conversation, interviewing is a specific form of goal-directed communication. As nurses converse with children and adults, they focus on the individuals to determine the kind of persons they are, their usual mode of handling problems, whether they need help, and the way they react to counseling. Developing interviewing skills requires time and practice, but following some guiding principles can facilitate this process. An organized approach is most effective when using interviewing skills in patient teaching.

Establishing a Setting for Communication

![]() Introduce yourself and ask the name of each family member who is present. Address parents or other adults by their appropriate titles, such as “Mr.” and “Mrs.,” unless they specify a preferred name. Record the preferred name on the medical record. Using formal address or their preferred names, rather than using first names or “mother” or “father,” conveys respect and regard for the parents or other caregivers (Seidel, Ball, Dains, et al, 2007).

Introduce yourself and ask the name of each family member who is present. Address parents or other adults by their appropriate titles, such as “Mr.” and “Mrs.,” unless they specify a preferred name. Record the preferred name on the medical record. Using formal address or their preferred names, rather than using first names or “mother” or “father,” conveys respect and regard for the parents or other caregivers (Seidel, Ball, Dains, et al, 2007).

![]() Critical Thinking Exercise—The Interview

Critical Thinking Exercise—The Interview

At the beginning of the visit, include children in the interaction by asking them their name, age, and other information. Nurses often direct all questions to adults, even when children are old enough to speak for themselves. This only terminates one extremely valuable source of information: the patient. When including the child, follow the general rules for communicating with children given in the Nursing Care Guidelines box on p. 122.

Assurance of Privacy and Confidentiality

The place where the nurse conducts the interview is almost as important as the interview itself. The physical environment should allow for as much privacy as possible, with distractions, such as interruptions, noise, or other visible activity, kept to a minimum. At times it is necessary to turn off a television, radio, or cellular telephone. The environment should also have some play provision for young children to keep them occupied during the parent-nurse interview (Fig. 6-1). Parents who are constantly interrupted by their children are unable to concentrate fully and tend to give brief answers to finish the interview as quickly as possible.

Confidentiality is another essential component of the initial phase of the interview. Since the interview is usually shared with other members of the health team care or the teacher (in the case of students), be certain to inform the family of the limits regarding confidentiality. If confidentiality is a concern in a particular situation, such as when talking to a parent suspected of child abuse or a teenager contemplating suicide, deal with this directly and inform the person that in such instances confidentiality cannot be ensured. However, the nurse judiciously protects information of a confidential nature.

Computer Privacy and Applications in Nursing

The use of computer technology to store and retrieve health information has become widespread. The health care community is increasingly concerned about the privacy and security of this health information. Any person accessing confidential health information is charged with managing safeguards for disclosure, since violations might incur civil damages.

Many institutions use computer and information applications in nursing (nursing informatics), such as electronic medical records, to record care and access information. Two important health care applications are record transmission, including facsimile (fax), electronic mail (e-mail), and telemedicine. The telemedicine application is capable of two-way video conferencing, transmission of radiographs, and clinical consultation between remote sites and centralized resources.*

Telephone Triage and Counseling

Nurses are increasingly responsible for assessing children’s symptoms and applying clinical judgment for further medical care (triage) via telephone report. Most often, health problems are assessed and prioritized according to urgency, and nurses provide treatment via telephone services. A well-designed telephone triage program is essential for safe, prompt, and consistent-quality health care (Beaulieu and Humphreys, 2008; Marklund, Ström, Månsson, et al, 2007). Telephone triage is more than “just a phone call,” since a child’s life is a high price to pay for poorly managed or incompetent telephone assessment skills. Typically, guidelines for telephone triage include asking screening questions; determining when to immediately refer to emergency medical services (dial 911); and determining when to refer to same-day appointments, appointments in 24 to 72 hours, appointments in 4 days or more, or home care (Box 6-1). Successful outcomes are based on the consistency and accuracy of the information provided. Telephone triage care management has increased access to high-quality health care services and empowered parents to participate in their child’s medical care. Consequently patient satisfaction has significantly improved. Unnecessary emergency department and clinic visits have decreased, saving medical costs and time (with less absence from work) for families in need of health care.

Communicating with Families

Although the parent and the child are separate and distinct individuals, the nurse’s relationship with the child is frequently mediated by the parent, particularly with younger children. For the most part, nurses acquire information about the child by direct observation or through communication with the parents. Usually it can be assumed that, because of the close contact with the child, the parent gives reliable information. Assessing the child requires input from the child (verbal and nonverbal), information from the parent, and the nurse’s own observations of the child and interpretation of the relationship between the child and the parent. When children are old enough to be active participants in their own health maintenance, the parent becomes a collaborator in health care.

Encouraging the Parents to Talk

Interviewing parents not only offers the opportunity to determine the child’s health and developmental status, but also offers information about factors that influence the child’s life. Whatever the parent sees as a problem should be a concern of the nurse. These problems are not always easy to identify. Nurses need to be alert for clues and signals by which a parent communicates worries and anxieties. Careful phrasing with broad, open-ended questions such as “What is Jimmy eating now?” provides more information than several single-answer questions, such as “Is Jimmy eating what the rest of the family eats?”

Sometimes the parent will take the lead without prompting. At other times it may be necessary to direct another question on the basis of an observation, such as “Connie seems unhappy today” or “How do you feel when David cries?” If the parent appears to be tired or distraught, consider asking, “What do you do to relax?” or “What help do you have with the children?” A comment such as “You handle the baby very well. What kind of experience have you had with babies?” to new parents who appear comfortable with their first child gives positive reinforcement and provides an opening for questions they might have on the infant’s care. Often all that is required to keep parents talking is a nod or saying “yes” or “uh-huh.”

When attempting to elicit feelings and probe covert problems, avoid closed-ended questions that begin with “Does ...,” “Did ...,” or “Is ...,” which usually require only a single response. In addition, asking questions such as “Does your son have any problems at school?” subtly implies a lack of parental skills and may make the parent defensive. Instead, say, “What ...,” “How ...,” “Tell me about ...” and encourage elaboration with “You were saying ...” or “You say that ...,” or by reflecting back a key word. Open-ended questions are nonthreatening and encourage description.

Directing the Focus

Directing the focus of the interview while allowing maximum freedom of expression is one of the most difficult goals in effective communication. One approach is the use of open-ended or broad questions, followed by guiding statements. For example, if the parent proceeds to list the other children by name, say, “Tell me their ages, too.” If the parent continues to describe each child in depth, which is not the purpose of the interview, redirect the focus by stating, “Let’s talk about the other children later. You were beginning to tell me about Paul’s activities at school.” This approach conveys interest in the other children but focuses the assessment on the patient.

Listening and Cultural Awareness

Listening is the most important component of effective communication. When the purpose of listening is to understand the person being interviewed, it is an active process that requires concentration and attention to all aspects of the conversation—verbal, nonverbal, and abstract. Major blocks to listening are environmental distraction and premature judgment.

Although it is necessary to make some preliminary judgments, listen with as much objectivity as possible by clarifying meanings and attempting to see the situation from the parent’s point of view. Effective interviewers consciously control their reactions, responses, and the techniques they use (see Cultural Competence box).

Minimum verbal activity with active listening facilitates parent involvement. It is tempting to spend time explaining, describing, and interpreting health information when the opportunity presents itself. However, it is possible to provide effective health education by timing the information properly and presenting only as much as is necessary at the moment.

Careful listening relies on the use of clues, verbal leads, or signals from the interviewee to move the interview along. Frequent references to an area of concern, repetition of certain key words, or a special emphasis on something or someone serve as cues to the interviewer for the direction of inquiry. Concerns and anxieties are often mentioned in a casual, offhand manner. Even though they are casual, they are important and deserve careful scrutiny to identify problem areas. For example, a parent who is concerned about a child’s habit of bed-wetting may casually mention that the child’s bed was “wet this morning.”

Using Silence

Silence as a response is often one of the most difficult interviewing techniques to learn. The interviewer requires a sense of confidence and comfort to allow the interviewee space in which to think without interruptions. Silence permits the interviewee to sort out thoughts and feelings and search for responses to questions. Silence can also be a cue for the interviewer to go more slowly, reexamine the approach, and not push too hard (Seidel, Ball, Dains, et al, 2007).

Sometimes it is necessary to break the silence and reopen communication. Do this in a way that encourages the person to continue talking about what is considered important. Breaking a silence by introducing a new topic or by prolonged talking essentially terminates the interviewee’s opportunity to use the silence. Suggestions for breaking the silence include statements such as “Is there anything else you wish to say?” “I see you find it difficult to continue; how may I help?” or “I don’t know what this silence means. Perhaps there is something you would like to put into words but find difficult to say.”

Being Empathic

Empathy is the capacity to understand what another person is experiencing from within that person’s frame of reference; it is often described as the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes. The essence of empathic interaction is accurate understanding of another’s feelings (Mathiasen, 2006). Empathy differs from sympathy, which is having feelings or emotions similar to those of another person, rather than understanding those feelings (Mathiasen, 2006).

Providing Anticipatory Guidance

The ideal way to handle a situation is to deal with it before it becomes a problem. The best preventive measure is anticipatory guidance. Traditionally, anticipatory guidance focused on providing families information on normal growth and development and nurturing childrearing practices. For example, one of the most significant areas in pediatrics is injury prevention. Beginning prenatally, parents need specific instructions on home safety. Because of the child’s maturing developmental skills, parents must implement home safety changes early to minimize risks to the child.

Unprepared parents can be disturbed by many normal developmental changes, such as a toddler’s diminished appetite, negativism, altered sleeping patterns, and anxiety toward strangers. The chapters on health promotion provide the nurse information for counseling parents. However, anticipatory guidance should extend beyond giving general information during brief visits to empowering families to use the information as a means of building competence in their parenting abilities (Magar, Dabova-Missova, and Gjerdingen, 2006). To achieve this level of anticipatory guidance, the nurse should:

Avoiding Blocks to Communication

A number of blocks to communication can adversely affect the quality of the helping relationship. The interviewer introduces many of these blocks, such as giving unrestricted advice or forming prejudged conclusions. Another type of block occurs primarily with the interviewees and concerns information overload. When individuals receive too much information or information that is overwhelming, they often demonstrate signs of increasing anxiety or decreasing attention. Such signals should alert the interviewer to give less information or to clarify what has been said. Box 6-2 lists some of the more common blocks to communication, including signs of information overload.

The nurse can correct communication blocks by careful analysis of the interview process. One of the best methods for improving interviewing skills is audiotape or videotape feedback. With supervision and guidance, the interviewer can recognize the blocks and consciously avoid them.

Communicating with Families Through an Interpreter

Sometimes communication is impossible because two people speak different languages. In this case it is necessary to obtain information through a third party, the interpreter. When using an interpreter, the nurse follows the same interviewing guidelines. Specific guidelines for using an adult interpreter are given in the Nursing Care Guidelines box.

Communicating with families through an interpreter requires sensitivity to cultural, legal, and ethical considerations (see Cultural Competence box). For example, in some cultures using a child as an interpreter is considered an insult to an adult because children are expected to show respect by not questioning their elders. In some cultures class differences between the interpreter and the family may cause the family to feel intimidated and less inclined to offer information. Therefore it is important to choose the translator carefully and provide time for the interpreter and family to establish rapport.

Legal and ethical concerns may also arise. For example, in obtaining informed consent through an interpreter, the nurse should fully inform the family of all aspects of the particular procedure to which they are consenting. Issues of confidentiality may arise when family members related to another patient are asked to interpret for the family, thus revealing sensitive information that may be shared with other families on the unit. With increased sensitivity toward patient rights and confidentiality, many institutions now require consent forms produced in the patient’s primary language.

Communicating with Children

![]() Although the greatest amount of verbal communication is usually carried out with the parent, do not exclude the child during the interview. Pay attention to infants and younger children through play or by occasionally directing questions or remarks to them. Include older children as active participants.

Although the greatest amount of verbal communication is usually carried out with the parent, do not exclude the child during the interview. Pay attention to infants and younger children through play or by occasionally directing questions or remarks to them. Include older children as active participants.

![]() Skill—Communicating with Children

Skill—Communicating with Children

In communication with children of all ages, the nonverbal components of the communication process convey the most significant messages. It is difficult to disguise feelings, attitudes, and anxiety when relating to children. They are alert to surroundings and attach meaning to every gesture and move that is made; this is particularly true of very young children.

Active attempts to make friends with children before they have had an opportunity to evaluate an unfamiliar person tend to increase their anxiety. Continue to talk to the child and parent but go about activities that do not involve the child directly, thus allowing the child to observe from a safe position. If the child has a special toy or doll, “talk” to the doll first. Ask simple questions such as “Does your teddy bear have a name?” to ease the child into conversation. Other guidelines for communicating with children are in the Nursing Care Guidelines box. Specific guidelines for preparing children for procedures, a common nursing function, are in Chapter 27.

Communication Related to Development of Thought Processes

The normal development of language and thought offers a frame of reference for communicating with children. Thought processes progress from sensorimotor to perceptual to concrete and finally to abstract, formal operations. An understanding of the typical characteristics of these stages provides the nurse with a framework to facilitate social communication (Box 6-3).

Infancy: Because they are unable to use words, infants primarily use and understand nonverbal communication. Infants communicate their needs and feelings through nonverbal behaviors and vocalizations that can be interpreted by someone who is around them for a sufficient time. Infants smile and coo when content and cry when distressed. Crying is provoked by unpleasant stimuli from inside or outside, such as hunger, pain, body restraint, or loneliness. Adults interpret this to mean that an infant needs something and consequently try to alleviate the discomfort and reduce tension. Crying (or the desire to cry) persists as a part of everyone’s communication repertoire.

Infants respond to adults’ nonverbal behaviors. They become quiet when they are cuddled, patted, or receive other forms of gentle physical contact. They receive comfort from the sound of a voice, even though they do not understand the words that are spoken. Until infants reach the age at which they experience stranger anxiety, they readily respond to any firm, gentle handling and quiet, calm speech. Loud, harsh sounds and sudden movements are frightening.

Older infants’ attention is centered on themselves and their parents; therefore any stranger is a potential threat until proved otherwise. Holding out the hands and asking the child to “come” is seldom successful, especially if the infant is with the parent. If infants must be handled, simply pick them up firmly without gestures. Observe the position in which the parent holds the infant. Most infants learn to prefer a particular position and manner of handling. In general, infants are more at ease upright than horizontal. Also, hold infants so they can see their parents. Until they develop the understanding that an object (in this case the parent) removed from sight can still be present, they have no way of knowing the object is still there.

Early Childhood: Children younger than 5 years of age are egocentric. They see things only in relation to themselves and from their point of view. Therefore focus communication on them. Tell them what they can do or how they will feel. Experiences of others are of no interest to them. It is futile to use another child’s experience in an attempt to gain the cooperation of small children. Allow them to touch and examine articles they will come in contact with. A stethoscope bell will feel cold; palpating a neck might tickle. Although they have not yet acquired sufficient language skills to express their feelings and wants, toddlers can effectively use their hands to communicate ideas without words. They push an unwanted object away, pull another person to show them something, point, and cover the mouth that is saying something they do not wish to hear.

Everything is direct and concrete to small children. They are unable to work with abstractions and interpret words literally. Analogies escape them because they are unable to separate fact from fantasy. For example, they attach literal meaning to such common phrases as “two-faced,” “sticky fingers,” or “coughing your head off.” Children who are told they will get “a little stick in the arm” may not be able to envision an injection (Fig. 6-3). Therefore avoid using a phrase that might be misinterpreted by a small child (see Nursing Care Guidelines box, Chapter 27, p. 1004).

Young children assign human attributes to inanimate objects. Consequently they fear that objects may jump, bite, cut, or pinch all by themselves. Children do not know that these devices are unable to perform without human direction. To minimize their fear, keep unfamiliar equipment out of view until it is necessary.

School-Age Years: Younger school-age children rely less on what they see and more on what they know when faced with new problems. They want explanations and reasons for everything but require no verification beyond that. They are interested in the functional aspect of all procedures, objects, and activities. They want to know why an object exists, why it is used, how it works, and the intent and purpose of its user. They need to know what is going to take place and why it is being done to them specifically. For example, to explain a procedure such as taking blood pressure, show the child how squeezing the bulb pushes air into the cuff and makes the “silver” in the tube go up. Let the child operate the bulb. An explanation for the procedure might be as simple as, “I want to see how far the silver goes up when the cuff squeezes your arm.” Consequently, the child becomes an enthusiastic participant.

School-age children have a heightened concern about body integrity. Because of the special importance they place on their body, they are sensitive to anything that constitutes a threat or suggestion of injury to it. This concern extends to their possessions, so that they may appear to overreact to loss or threatened loss of treasured objects. Helping children voice their concerns enables the nurse to provide reassurance and to implement activities that reduce their anxiety. For example, if a shy child dislikes being the center of attention, ignore that particular child by talking and relating to other children in the family or group. When children feel more comfortable, they will usually interject personal ideas, feelings, and interpretations of events.

Older children have an adequate and satisfactory use of language. They still require relatively simple explanations, but their ability to think concretely can facilitate communication and explanation. Commonly, they have sufficient experience with health and health care workers to understand what is happening and what is generally expected of them.

Adolescence: As children move into adolescence, they fluctuate between child and adult thinking and behavior. They are riding a current that is moving them rapidly toward a maturity that may be beyond their coping ability. Therefore, when tensions rise, they may seek the security of the more familiar and comfortable expectations of childhood. Anticipating these shifts in identity allows the nurse to adjust the course of interaction to meet the needs of the moment. No single approach can be relied on consistently, and encountering cooperation, hostility, anger, bravado, and a variety of other behaviors and attitudes is common. It is as much a mistake to regard the adolescent as an adult with an adult’s wisdom and control as it is to assume that the teenager has the concerns and expectations of a child.

Frequently adolescents are more willing to discuss their concerns with an adult outside the family, and they often welcome the opportunity to interact with a nurse outside the presence of their parents. They accept anyone who displays a genuine interest in them. However, adolescents are quick to reject persons who attempt to impose their values on them, whose interest is feigned, or who appear to have little respect for who they are and what they think or say.

![]() Interviewing the adolescent presents some special issues. The first may be whether to talk with the adolescent alone or with the adolescent and parents together. Of course, if the parent is not there, the only question is whether to suggest to the teenager that the parents be interviewed at another time. If the parents and teenager are together, talking with the adolescent first has the advantage of immediately identifying with the young person, thus fostering the interpersonal relationship. However, talking with the parents initially may provide insight into the family relationship. In either case, give both parties an opportunity to be included in the interview. If time is limited, such as during history taking, clarify this at the onset to avoid appearing to “take sides” by talking more with one person than with the other.

Interviewing the adolescent presents some special issues. The first may be whether to talk with the adolescent alone or with the adolescent and parents together. Of course, if the parent is not there, the only question is whether to suggest to the teenager that the parents be interviewed at another time. If the parents and teenager are together, talking with the adolescent first has the advantage of immediately identifying with the young person, thus fostering the interpersonal relationship. However, talking with the parents initially may provide insight into the family relationship. In either case, give both parties an opportunity to be included in the interview. If time is limited, such as during history taking, clarify this at the onset to avoid appearing to “take sides” by talking more with one person than with the other.

![]() Case Study—Communicating with Adolescents

Case Study—Communicating with Adolescents

Confidentiality is of great importance when interviewing adolescents. Explain to parents and teenagers the limits of confidentiality, specifically that young persons’ disclosures will not be shared unless they indicate a need for intervention, as in the case of suicidal behavior.

Another dilemma in interviewing adolescents is that two views of a problem frequently exist—the teenager’s and the parents’. Clarification of the problem is a major task. However, providing both parties an opportunity to discuss their perceptions in an open and unbiased atmosphere can, by itself, be therapeutic. Demonstrating positive communication skills can help families communicate more effectively (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Communication Techniques

In addition to such conventional interviewing methods as reflection and open-ended questions, a number of techniques encourage family members to express their thoughts and feelings in a less directive and confrontational manner. Several approaches are projective—they present nonspecific material that enables individuals to externalize or project inner aspects of themselves to others.

Nurses use a variety of verbal techniques to encourage communication. Some of these techniques are useful to pose questions or explore concerns in a less threatening manner. Others can be presented as word games, which are often well received by children. However, for many children and adults, talking about feelings is difficult, and verbal communication may be more stressful than supportive. In such instances, use several nonverbal techniques to encourage communication.

Box 6-4 describes both verbal and nonverbal techniques. Because of the importance of play in communicating with children, play is discussed more extensively below. Any of the verbal or nonverbal techniques can give rise to strong feelings that surface unexpectedly. Be prepared to handle them or to recognize when issues go beyond your ability to deal with them. At that point, consider an appropriate referral.

Play

Play is a universal language of children. It is one of the most important forms of communication and can be an effective technique in relating to them. The nurse can often pick up on clues about physical, intellectual, and social developmental progress from the form and complexity of a child’s play behaviors. Play requires minimum equipment or none at all. Many providers use therapeutic play to reduce the trauma of illness and hospitalization (see Chapter 27) and to prepare children for therapeutic procedures (see Chapter 27).

Because their ability to perceive precedes their ability to transmit, infants respond to activities that register on their physical senses. Patting, stroking, and other skin play conveys messages. Repetitive actions, such as stretching infants’ arms out to the side while they are lying on their back and then folding the arms across the chest or raising and revolving the legs in a bicycling motion, will elicit pleasurable sounds. Colorful items to catch the eye or interesting sounds, such as a ticking clock, chimes, bells, or singing, can be used to attract children’s attention.

Older infants respond to simple games. The old game of peek-a-boo is an excellent means of initiating communication with infants while maintaining a “safe,” nonthreatening distance. After this intermittent eye contact, the nurse is no longer viewed as a stranger but as a friend. This can be followed by touch games. Clapping an infant’s hands together for pat-a-cake or wiggling the toes for “this little piggy” delights an infant or small child. Talking to a foot or other part of the child’s body is another effective tactic. Much of the nursing assessment can be carried out with the use of games and simple play equipment while the infant remains in the safety of the parent’s arms or lap.

The nurse can capitalize on the natural curiosity of small children by playing games such as “Which hand do you take?” and “Guess what I have in my hand” or by manipulating items such as a flashlight or stethoscope. Finger games are useful. More elaborate materials, such as puppets and replicas of familiar or unfamiliar items, serve as excellent means of communicating with small children. The variety and extent are limited only by the nurse’s imagination.

Through play, children reveal their perceptions of interpersonal relationships with their family, friends, or hospital personnel. Children may also reveal the wide scope of knowledge they have acquired from listening to others around them. For example, through needle play, children may reveal how carefully they have watched each procedure by precisely duplicating the technical skills. They may also reveal how well they remember those who performed procedures. In one example, a child painstakingly reenacted every detail of a tedious medical procedure, including the role of the physician who had repeatedly shouted at her to be still for the long ordeal. Her anger at him was most evident during the play session and revealed the cause for her abrupt withdrawal and passive hostility toward the medical and nursing staff after the test.

Play sessions serve not only as assessment tools for determining children’s awareness and perception of their illness, but also as methods of intervention and evaluation. In the previous example, when the child revealed anger toward the physician, the nurse acted the part of the patient but this time did not accept the physician’s harsh commands to stay still. Instead, the nurse said to the physician all the things the child had wished she could say.

History Taking

The format used for history taking may be (1) direct, where the nurse asks for information via direct interview with the informant; or (2) indirect, where the informant supplies the information by completing some type of questionnaire. The direct method is superior to the indirect approach or a combination of both. However, because time is limited, the direct approach is not always practical. If the nurse cannot use the direct approach, he or she should review parents’ written responses and question them regarding any unusual answers. The categories listed in Box 6-5 encompass children’s current and past health status and information about their psychosocial environment.

Identifying Information

Much of the identifying information may already be available from other recorded sources. However, if the parent and youngster seem anxious, use this opportunity to ask about such information to help them feel more comfortable.

Informant: One of the important elements of identifying information is the informant, the person(s) who furnishes the information. Record (1) who the person is (child, parent, or other), (2) an impression of reliability and willingness to communicate, and (3) any special circumstances such as the use of an interpreter or conflicting answers by more than one person.

Chief Complaint

The chief complaint is the specific reason for the child’s visit to the clinic, office, or hospital. It may be the theme, with the present illness viewed as the description of the problem. Elicit the chief complaint by asking open-ended, neutral questions such as “What seems to be the matter?” “How may I help you?” or “Why did you come here today?” Avoid labeling-type questions such as “How are you sick?” or “What is the problem?” It is possible that the reason for the visit is not an illness or problem.

Occasionally, it is difficult to isolate one symptom or problem as the chief complaint because the parent may identify many. In this situation be as specific as possible when asking questions. For example, asking informants to state which one problem or symptom prompted them to seek help now may help them focus on the most immediate concern.

Present Illness

The history of the present illness* is a narrative of the chief complaint from its earliest onset through its progression to the present. Its four major components are (1) the details of onset, (2) a complete interval history, (3) the present status, and (4) the reason for seeking help now. The focus of the present illness is on all factors relevant to the main problem, even if they have disappeared or changed during the onset, interval, and present.

Analyzing a Symptom: Because pain is often the most characteristic symptom denoting the onset of a physical problem, it is used as an example for analysis of a symptom. Assessment includes (1) type, (2) location, (3) severity, (4) duration, and (5) influencing factors (see Nursing Care Guidelines box; see also Pain Assessment, Chapter 7).

History

The history contains information relating to all previous aspects of the child’s health status and concentrates on several areas that are ordinarily passed over in the history of an adult, such as birth history, detailed feeding history, immunizations, and growth and development. Since this section includes a great deal of information, use a combination of open-ended and fact-finding questions. For example, begin interviewing for each section with an open-ended statement such as “Tell me about your child’s birth” to provide the informants the opportunity to relate what they think is most important. Ask fact-finding questions related to specific details whenever necessary to focus the interview on certain topics.

Birth History: The birth history includes all data concerning (1) the mother’s health during pregnancy, (2) the labor and delivery, and (3) the infant’s condition immediately after birth. Since prenatal influences have significant effects on a child’s physical and emotional development, a thorough investigation of the birth history is essential. Because parents may question what relevance pregnancy and birth have on the child’s present condition, particularly if the child is past infancy, explain why such questions are included. An appropriate statement may be, “I will be asking you some questions about your pregnancy and ____’s [refer to child by name] birth. Your answers will give me a more complete picture of his [or her] overall health.”

Because emotional factors also affect the outcome of pregnancy and the subsequent parent-child relationship, investigate (1) concurrent crises during pregnancy and (2) prenatal attitudes toward the fetus. It is best to approach the topic of parental acceptance of pregnancy through indirect questioning. Asking parents if the pregnancy was planned is a leading statement because they may respond affirmatively for fear of criticism if the pregnancy was unexpected. Rather, encourage parents to state their true reactions by referring to specific facts relating to the pregnancy, such as the spacing between offspring, an extended or short interval between marriage and conception, or a pregnancy during adolescence. The parent can choose to explore such statements with further explanations or, for the moment, may not be able to reveal such feelings. If the parent remains silent, return to this topic later in the interview.

Dietary History: Because parental concerns are common and nursing interventions are important in ensuring optimum nutrition, the dietary history is discussed in detail later in this chapter under Nutritional Assessment.

Previous Illnesses, Injuries, and Operations: When inquiring about past illnesses, begin with a general statement such as “What other illnesses has your child had?” Since parents are most likely to recall serious health problems, ask specifically about colds; earaches; and childhood diseases such as measles, rubella (German measles), chickenpox, mumps, pertussis (whooping cough), diphtheria, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, strep throat, recurrent ear infections, gastroesophageal reflux, tonsillitis, or allergic manifestations.

In addition to illnesses, ask about injuries that required medical intervention, operations, and any other reason for hospitalization, including the dates of each incident. Focus on injuries such as accidental falls, poisoning, choking, or burns, since these may be potential areas for parental guidance.

Allergies: Ask about commonly known allergic disorders such as hay fever and asthma; unusual reactions to drugs, food, or latex products; and reactions to other contact agents such as poisonous plants, animals, household products, or fabrics. If asked appropriate questions, most people can give reliable information about drug reactions (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Current Medications: Inquire about current drug regimens, including vitamins, antipyretics (especially aspirin), antibiotics, antihistamines, decongestants, or herbs and homeopathic medications. List all medications, including name, dose, schedule, duration, and reason for administration. Often parents are unaware of the drug’s actual name. Whenever possible, ask parents to bring the containers with them to the next visit, or ask for the name of the pharmacy and call for a list of all the child’s recent prescription medications. However, this list will not include over-the-counter medications, which are important to know.

Immunizations: A record of all immunizations is essential. Since many parents are unaware of the exact name and date of each immunization, the most reliable source of information is a hospital, clinic, or private practitioner’s record. All immunizations and “boosters” are listed, stating (1) the name of the specific disease, (2) the number of injections, (3) the dosage (sometimes lesser amounts are given if a reaction is anticipated), (4) the ages when administered, and (5) the occurrence of any reaction following the immunization.

Growth and Development: The most important previous growth patterns to record are:

• Approximate weight at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 5 years of age

• Approximate length at ages 1 and 4 years

• Dentition, including age of onset, number of teeth, and symptoms during teething

Developmental milestones include:

• Age of holding up head steadily

• Age of sitting alone without support

• Age of walking without assistance

• Age of saying first words with meaning

Use specific and detailed questions when inquiring about each developmental milestone. For example, “sitting up” can mean many different activities, such as sitting propped up, sitting in someone’s lap, sitting with support, sitting up alone but in a hyperflexed position for assisted balance, or sitting up unsupported with the back slightly rounded. A clue to misunderstanding of the requested activity may be an unusually early age of achievement.

Habits: Habits are an important area to explore (Box 6-6). Parents frequently express concerns during this part of the history. Encourage their input by saying, “Please tell me any concerns you have about your child’s habits, activities, or development.” Investigate further any concerns that parents express.

One of the most common concerns relates to sleep. Many children develop a normal sleep pattern, and all that is required during the assessment is a general overview of nighttime sleep and nap schedules. However, a number of children develop sleep problems (see Sleep Problems, Chapters 10 and 13). When sleep problems occur, the nurse needs a more detailed sleep history to guide appropriate interventions.*

Habits related to use of chemicals apply primarily to older children and adolescents. If a youngster admits to smoking, drinking, or using drugs, ask about the quantity and frequency. Questions such as “Many kids your age are experimenting with drugs and alcohol; have you ever had any drugs or alcohol?” may give more reliable data than questions such as “How much do you drink?” or “How often do you drink or take drugs?” Clarify that “drinking” includes all types of alcohol, including beer and wine. When quantities such as a “glass” of wine or a “can” of beer are given, ask about the size of the container.

If older children deny use of chemical substances, inquire about past experimentation. Asking, “You mean you never tried to smoke or drink?” implies that the nurse expects some such activity, and the youngster may be more inclined to answer truthfully. Be aware of the confidential nature of such questioning, the adverse effect that the parents’ presence may have on the adolescent’s willingness to answer, and the fact that self-reporting may not be an accurate account of chemical abuse.

Sexual History

The sexual history is an essential component of adolescents’ health assessment. The history uncovers areas of concern related to sexual activity; alerts the nurse to circumstances that may indicate screening for sexually transmitted infections or testing for pregnancy; and provides information related to the need for sexual counseling, such as safer sex practices. Box 6-7 gives guidelines for anticipatory guidance topics for parents and adolescents.

One approach to initiating a conversation about sexual concerns is to begin with a history of peer interactions. Open-ended statements such as “Tell me about your social life” or “Who are your closest friends?” generally lead into a discussion of dating and sexual issues. To probe further, include questions about the adolescent’s attitudes on such topics as sex education, “going steady,” “living together,” and premarital sex. Phrase questions to reflect concern rather than judgment or criticism of sexual practices.

In any conversation regarding sexual history, be aware of the language that is used in either eliciting or conveying sexual information. For example, avoid asking whether the adolescent is “sexually active,” since this term is broadly defined. “Are you having sex with anyone?” is probably the most direct and best understood question. Since same-sex experimentation may occur, refer to all sexual contacts in nongender terms, such as “anyone” or “partners,” rather than “girlfriends” or “boyfriends.”

A detailed account of sexual partners is necessary if the patient has a history of, displays any symptoms of, or asks for treatment of a sexually transmitted infection. A difficult but necessary part of the interview is to determine the sites of possible infection. Since sexual diseases can be contracted in any of the body orifices, inform the adolescent that a sexually transmitted infection can be acquired without visible signs of disease at nongenital sites.

Family Medical History

The family medical history is used primarily to discover any hereditary or familial diseases in the parents and child. In general, it is confined to first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, grandparents, and immediate aunts and uncles). Information for each family member includes age; marital status; state of health if living; cause of death if deceased; and any evidence of conditions such as early heart disease, sudden death from unknown cause, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, cancer, diabetes mellitus, obesity, congenital anomalies, allergies, asthma, seizures, tuberculosis, sickle cell disease, cognitive impairment, hearing or visual deficits, psychiatric disorders such as depression or psychosis, and emotional problems. Confirm the accuracy of the reported disorders by inquiring about the symptoms, course, treatment, and sequelae of each diagnosis.

Geographic Location: One of the important areas to explore when assessing the family health history is geographic location, including the birthplace and travel to different areas in or outside of the country, for identification of possible exposure to endemic diseases. Although the primary interest is the child’s temporary residence in various localities, also inquire about close family members’ travel, especially during tours of military service or business trips. Children are especially susceptible to parasitic infestation in areas of poor sanitary conditions and to vector-borne diseases, such as those from mosquitoes or ticks in warm and humid or heavily wooded regions.

Family Structure

Assessment of the family, both its structure and function, is an important component of the history-taking process. Because the quality of the functional relationship between the child and family members is a major factor in emotional and physical health, family assessment is discussed separately and in greater detail apart from the more traditional health history.

Family assessment is the collection of data about the composition of the family and the relationships among its members. In its broadest sense, family refers to all those individuals who are considered by the family member to be significant to the nuclear unit, including relatives, friends, and social groups such as the school and church. Although family assessment is not family therapy, it can and frequently is therapeutic. Involving family members in discussing family characteristics and activities can provide insight into family dynamics and relationships.

Because of the time involved in performing an in-depth family assessment as presented here, be selective in deciding when knowledge of family function may facilitate nursing care (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). During brief contacts with families, a full assessment is not appropriate, and screening with one or two questions from each category may reflect the health of the family system or the need for additional assessment.

Family structure refers to the composition of the family—who lives in the home and those social, cultural, religious, and economic characteristics that influence the child’s and family’s overall psychobiologic health (see also Chapters 2 and 3). Since the information elicited in this part of the history is often the most personal and confidential, include it toward the end of the interview when rapport is well established.

The most common method of eliciting information on the family structure is to interview family members. The principal areas of concern are (1) family composition, (2) home and community environment, (3) occupation and education of family members, and (4) cultural and religious traditions (Box 6-8).

Psychosocial History

The traditional medical history includes a personal and social section that concentrates on children’s personal status, such as school adjustment and any unusual habits, and the family and home environment. Since several personal aspects are covered under development and habits, only those issues related to children’s ability to cope and their self-concept are presented here.

Through observation, obtain a general idea of how children handle themselves in terms of confidence in dealing with others, answering questions, and coping with new situations. Observe the parent-child relationship for the types of messages sent to children about their coping skills and self-worth. Do the parents treat the child with respect, focusing on strengths, or is the interaction one of constant reprimands, with emphasis on weaknesses and faults? Do the parents help the child learn new coping strategies or support the ones the child uses?

Parent-child interactions also convey messages about body image. Do the parents label the child and body parts, such as “bad boy,” “skinny legs,” or “ugly scar”? Do the parents handle the child gently, using soothing touch to calm an anxious child, or do they treat the child roughly, using slaps or restraint to make the child obey? If the child touches certain parts of the body, such as the genitalia, do the parents make comments that suggest a negative connotation?

With older children many of the communication strategies discussed earlier in the chapter are useful in eliciting more definitive information about their coping and self-concept. Children can write down five things they like and dislike about themselves. The nurse can use sentence completion statements, such as “The thing I like best (or worst) about myself is ____________”; “If I could change one thing about myself, it would be ____________”; or “When I am scared, I ____________.”

Review of Systems

![]() The review of systems is a specific review of each body system, following an order similar to that of the physical examination (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Often the history of the present illness provides a complete review of the system involved in the chief complaint. Since asking questions about other body systems may appear irrelevant to the parents or child, precede the questioning with an explanation of why the data are necessary (similar to the explanation concerning the relevance of the birth history) and reassure the parents that the child’s main problem has not been forgotten.

The review of systems is a specific review of each body system, following an order similar to that of the physical examination (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Often the history of the present illness provides a complete review of the system involved in the chief complaint. Since asking questions about other body systems may appear irrelevant to the parents or child, precede the questioning with an explanation of why the data are necessary (similar to the explanation concerning the relevance of the birth history) and reassure the parents that the child’s main problem has not been forgotten.

![]() Animation—Organ Systems 3-D Tour

Animation—Organ Systems 3-D Tour

Begin the review of a specific system with a broad statement such as “How has your child’s general health been?” or “Has your child had any problems with his eyes?” If the parent states that the child has had problems with some body function, pursue this with an encouraging statement such as “Tell me more about that.” If the parent denies any problems, query for specific symptoms (e.g., “No headaches, bumping into objects, or squinting?”). If the parent reconfirms the absence of such symptoms, record positive statements in the history, such as “Mother denies headaches, bumping into objects, or squinting.” In this way, anyone who reviews the health history is aware of exactly what symptoms were investigated.

Nutritional Assessment

Food consumption patterns of children have changed over the past 30 years (Nicklas, Demory-Luce, Yang, et al, 2004). The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents has significantly increased (Hedley, Ogden, Johnson, et al, 2004). Knowledge of the child’s dietary intake is an essential component of a nutritional assessment. However, it is also one of the most difficult factors to assess. Individuals’ recall of food consumption, especially amounts eaten, is frequently unreliable. The food intake history of children and adolescents is prone to reporting error, mostly in the form of underreporting (Livingstone, Robson, and Wallace, 2004). People from different cultures may have difficulty adequately describing the types of food they eat. Despite these obstacles, a dietary evaluation is an important component of the child’s assessment.

The dietary reference intakes (DRIs) are a set of four nutrient-based reference values that provide quantitative estimates of nutrient intake for use in assessing and planning dietary intake (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2004; Murphy and Poos, 2002). The specific DRIs are:

Estimated average requirement (EAR)—Nutrient intake estimated to meet the requirement of half the healthy individuals (50%) for a specific age and gender group.

Recommended dietary allowance (RDA)—Average daily dietary intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirement of nearly all (97% to 98%) of healthy individuals for a specific age and gender group.

Adequate intake (AI)—Recommended intake level based on estimates of nutrient intake by healthy groups of individuals.

Tolerable upper intake level (UL)—Highest average daily nutrient intake level likely to pose no risk of adverse health effects. As intake increases above the UL, risk of adverse effects increases.

Fig. 6-4 contains MyPlate, which describes dietary intake in children. Specific questions used to conduct a nutritional assessment are given in Box 6-9. Every nutritional assessment should begin with a dietary history. The exact questions used to elicit a dietary history vary with the child’s age. In general, the younger the child, the more specific and detailed the history should be. The overview elicited from the dietary history can be helpful in evaluating food frequency records. The history is also concerned with financial and cultural factors that influence food selection and preparation (see Cultural Competence box).

The most common and probably easiest method of assessing daily intake is the 24-hour recall. The child or parent recalls every item eaten in the past 24 hours and the approximate amounts. The 24-hour recall is most beneficial when it represents a typical day’s intake. Some of the difficulties with a daily recall are the family’s inability to remember exactly what was eaten and inaccurate estimation of portion size. To increase accuracy of reporting portion sizes, the use of food models and additional questions are recommended. In general, this method is most useful in providing qualitative information about the child’s diet.

To improve the reliability of the daily recall, the family can complete a food diary by recording every food and liquid consumed for a certain number of days. A 3-day record consisting of 2 weekdays and 1 weekend day is representative for most people. Providing specific charts to record intake can improve compliance. The family should record items immediately after eating.

A food frequency questionnaire or record provides information about the number of times in a day, week, or month a child consumes items from the different food groups. In general, it provides a qualitative overview but has the advantage of avoiding recall based on a “typical” day. It can be especially useful when verifying a food history or diary.

Clinical Examination of Nutrition

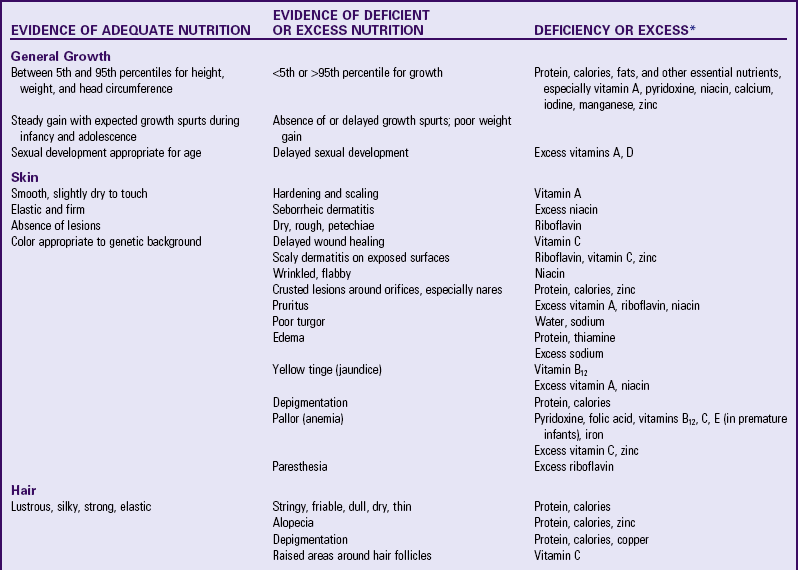

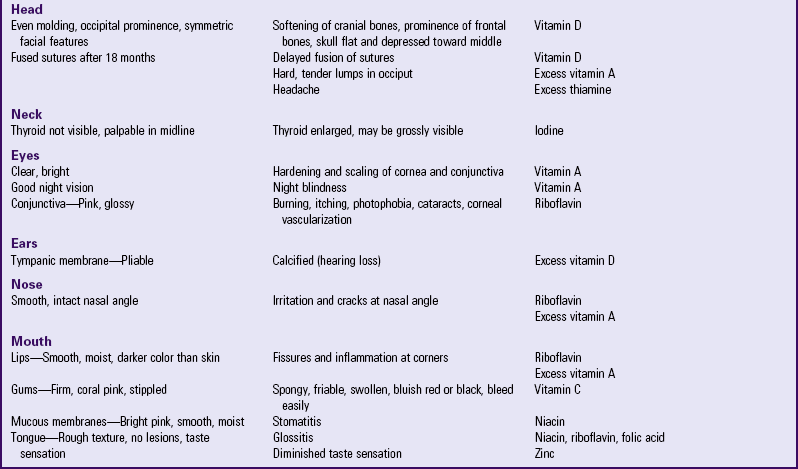

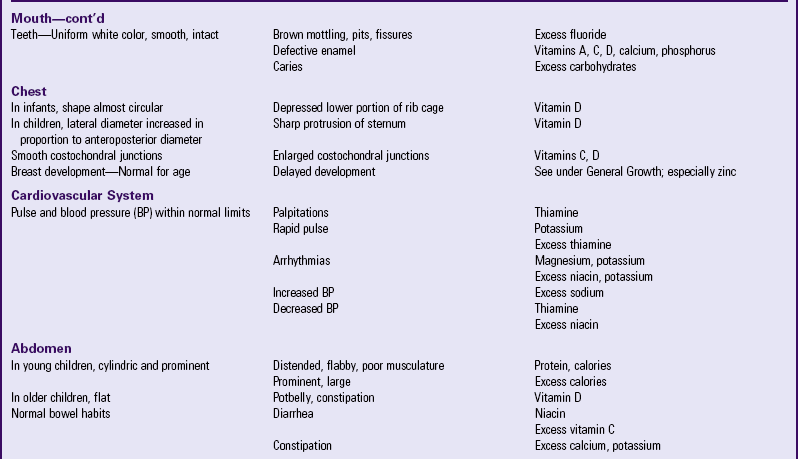

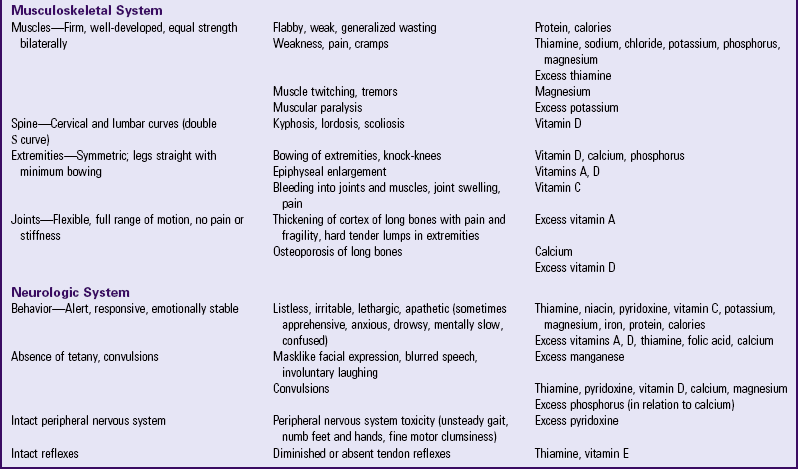

A significant amount of information regarding nutritional deficiencies comes from a clinical examination, especially from assessing the skin, hair, teeth, gums, lips, tongue, and eyes. Hair, skin, and mouth are vulnerable because of the rapid turnover of epithelial and mucosal tissue. Table 6-1 summarizes clinical signs of possible nutritional deficiency or excess. Few are diagnostic for a specific nutrient, and if suspicious signs are found, they must be confirmed with dietary and biochemical data. Generally, the clinical examination does not reveal children at risk for a deficiency or excess.

Anthropometry, an essential parameter of nutritional status, is the measurement of height, weight, head circumference, proportions, skinfold thickness, and arm circumference in young children. Height and head circumference reflect past nutrition, whereas weight, skinfold thickness, and arm circumference reflect present nutritional status, especially of protein and fat reserves. Skinfold thickness is a measurement of the body’s fat content because approximately half the body’s total fat stores are directly beneath the skin. The upper arm muscle circumference is correlated with measurements of total muscle mass. Since muscle serves as the body’s major protein reserve, this measurement is considered an index of the body’s protein stores. Ideally, growth measurements are recorded over time, and comparisons are made regarding the velocity of growth based on previous and present values.

Numerous biochemical tests are available for assessing nutritional status and include analysis of plasma; blood cells; urine; and tissues from liver, bone, hair, and fingernails. Many of these tests are complicated and are not performed routinely. Common laboratory procedures for nutritional status include measurement of hemoglobin, hematocrit, transferrin, albumin, creatinine, and nitrogen. Appendix C provides laboratory values for these tests and more specific nutrient measurements.

Evaluation of Nutritional Assessment

After collecting the data needed for a thorough nutritional assessment, evaluate the findings to plan appropriate counseling. From the data, assess whether the child is (1) malnourished, (2) at risk for becoming malnourished, (3) well nourished with adequate reserves, or (4) overweight or obese.

Analyze the daily food diary for the variety and amounts of foods suggested in MyPlate (see Fig. 6-4). For example, if the list includes no vegetables, inquire about this rather than assuming that the child dislikes vegetables, since it is possible that none were served that day. Also, evaluate the information in terms of the family’s ethnic practices and financial resources. Encouraging increased protein intake with additional meat is not always feasible for families on a limited budget and may conflict with food practices that use meat sparingly, such as in Asian meal preparation.