Family-Centered Care of the Child During Illness and Hospitalization

What Is Family Centered Care?,

Stressors of Hospitalization and Children’s Reactions

Stressors and Reactions of the Family of the Child Who Is Hospitalized

Nursing Care of the Child Who Is Hospitalized

Preventing or Minimizing Separation

Minimizing Loss of Control and Autonomy

Preventing or Minimizing Fear of Bodily Injury

Providing Developmentally Appropriate Activities

Using Play and Expressive Activities to Minimize Stress

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Administration of Medication, Ch. 27

Communication and Physical and Developmental Assessment of the Child, Ch. 6

Compliance, Ch. 27

Family-Centered Care of the Child with Chronic Illness or Disability, Ch. 22

Family-Centered End-of-Life Care, Ch. 23

Family-Centered Home Care, Ch. 25

Neonatal Pain, Ch. 7

Nursing Care of the Surgical Neonate, Ch. 11

Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, Ch. 27

Social, Cultural, and Religious Influences on Child Health Promotion, Ch. 2

Surgical Procedures, Ch. 27

What is Family-Centered Care?

The theory of family-centered care began to materialize in health care in the late 1960s, as physicians realized the necessity of meeting patient’s psychosocial and developmental needs, as well as including families in care. Now the American Academy of Pediatrics (2003) defines family-centered care as “an approach to health care that shapes health care policies, programs, facility design, and day-to-day interactions among patients, families, physicians, and other health care professionals.” Proponents of family-centered care believe that collaboration must exist between patients, family members, physicians, nurses, and all members of the health care team in order to reach desired outcomes for the patient. In addition, the Institute for Family-Centered Care acknowledges that families are “essential to patients’ health and well-being and are allies for quality and safety within the health care system” (Conway, Johnson, Edgman-Levitan, et al, 2006). The family-centered care movement gained further momentum due to a report from the Institute of Medicine (2001) titled “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” which calls for changes in the health care environment to improve patient safety and quality of care. In this report, the Institute of Medicine called for increased involvement of patients in their own health care decisions, better communication to patients regarding treatment options, and care that is respectful of patient preferences and values.

Nursing professionals should engage patients and families in the care planning and decision-making process. Inherent in nursing philosophy is the idea that nurses nurture patients and form a partnership with parents or families. This collaboration leads to nurses and parents working together to treat the child holistically, thus meeting all of his or her needs. As a partner in care, nurses are challenged to incorporate family and child preferences to decrease stress, minimize the negative effects of hospitalization, maximize the benefits of hospitalization, ensure adequate discharge planning and preparation, and provide overall comfort and support.

Stressors of Hospitalization and Children’s Reactions

Often illness and hospitalization are the first crises children must face. Especially during the early years, children are particularly vulnerable to the crises of illness and hospitalization because (1) stress represents a change from the usual state of health and environmental routine and (2) children have a limited number of coping mechanisms to resolve stressors. Major stressors of hospitalization include separation from parents and loved ones; fear of the unknown; loss of control and autonomy; bodily injury resulting in discomfort, pain, and mutilation; and the fear of death. Children’s developmental age; previous experience with illness, separation, or hospitalization; their innate and acquired coping skills; the seriousness of the diagnosis; and the support system available influence their reaction to these crises.

Separation Anxiety

The major stress from middle infancy throughout the preschool years, especially for children ages 16 to 30 months, is separation anxiety, also called anaclitic depression. Box 26-1 summarizes the principal behavioral responses of these children to the three phases of separation anxiety.

During the phase of protest, children react aggressively to separation from the parent. They cry and scream for their parents, refuse the attention of anyone else, and are inconsolable in their grief (Fig. 26-1). They may continue this behavior for a few hours to several days. Some children may protest continuously, ceasing only from physical exhaustion. If a stranger approaches them, children initially protest even louder. During the phase of despair, the crying stops and depression is evident. The child is much less active, is uninterested in play or food, and withdraws from others. The child looks sad, lonely, isolated, and apathetic (Fig. 26-2).

Fig. 26-1 In the protest phase of separation anxiety, children cry loudly and are inconsolable in their grief for the parent. (Courtesy James DeLeon, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Fig. 26-2 During the despair phase of separation anxiety, children are sad, lonely, and uninterested in play or food.

During the third phase, detachment, or denial, the child appears to have finally adjusted to the loss. The child becomes more interested in the surroundings, plays with others, and seems to form new relationships. In this phase, care givers and health care professionals often think the child has adjusted to hospitalization. However, this behavior is a result of resignation and is not a sign of contentment. The child detaches from the parent in an effort to escape the emotional pain of desiring the parent’s presence. The child copes by forming shallow relationships with others, becoming increasingly self-centered, and attaching primary importance to material objects. This is the most serious phase because reversal of the potential adverse effects is less likely to occur once detachment is established. However, if separations imposed by hospitalization are temporary, they do not cause prolonged parental absences that lead to detachment. In addition, considerable evidence suggests that, even with stresses such as separation, permanent ill effects are rare.

Although progression to detachment is uncommon, the initial phases of separation anxiety are frequently observed even with brief separations from either parent. Without understanding the meaning of each stage of behavior, health team members may erroneously label the behaviors as positive or negative. In the phase of protest, they may view the loud crying as “bad” behavior. Because the protesting increases if a stranger approaches, staff may interpret the reaction as evidence of their need to stay away. During the quiet, withdrawn phase of despair, they regard the child as finally “settling in” to the new surroundings and see the detachment behaviors as proof of a “good adjustment.” The faster a child reaches this stage, the more likely it is that health care providers will regard the child as the ideal patient.

If parents cannot remain with their child throughout the hospitalization, children may exhibit a variety of responses to parental presence or visitation. During the protest phase, children do not outwardly appear happy to see their parents and may even cry louder than they did before the visit began. Depressed children may protest when parents visit or completely reject their parents’ company. Other children may cling to their parents to force their continued presence. In the phase of detachment, children respond no differently to their parents than to any other person. Due to these negative responses and reactions, uninformed observers may think that parental visitation is disturbing the child’s adjustment and feel justified in restricting visitation.

Seeing these reactions to hospitalization is distressing to parents, who may be unaware of their meaning. Because of their child’s behaviors, parents may see their absence as beneficial to the child’s adjustment and recovery. They may respond to the child’s behavior by staying for short periods, decreasing the frequency of visits, or deceiving the child when it is time to leave. The result is a destructive cycle of misunderstanding and unmet needs.

Early Childhood

Separation anxiety is the greatest stress imposed by hospitalization during early childhood. If separation is avoided or decreased, young children have a tremendous capacity to withstand any other stress. In this age-group, the typical reactions just described are seen. However, children in the toddler stage demonstrate more goal-directed behaviors. For example, they may verbally plead for their parents to stay and physically attempt to secure or find them. They may demonstrate displeasure on the parents’ return or departure by having temper tantrums; refusing to comply with the usual routines of mealtime, bedtime, or toileting; or regressing to more primitive levels of development. Temper tantrums, bed-wetting, or other behaviors may also be explained as expressions of anger or can be a physiologic response to stress.

Because preschoolers are much more secure interpersonally than toddlers, they can tolerate brief periods of separation from their parents and are more inclined to develop substitute trust in other significant adults. The stress of illness, however, usually renders them less able to cope with separation. As a result, they manifest many of the behaviors of separation anxiety, although the protest behaviors are more subtle and passive than those seen in younger children. Preschoolers may demonstrate separation anxiety by refusing to eat, having difficulty sleeping, crying quietly for their parents, continually asking when they will visit, or withdrawing from others. They may express anger indirectly by breaking their toys, hitting other children, or refusing to cooperate during usual self-care activities. Nurses need to be sensitive to these less obvious signs of separation anxiety in order to intervene appropriately.

Later Childhood

Previous research, usually based on adult recollections, indicated that the family does not play as important a role for school-age children as it does during the toddler and preschool years. However, in a qualitative study of children ages 5 to 9 years, children described hospitalization in stories that focused on being alone and feeling scared, mad, or sad. These children also described the need for protection and companionship while hospitalized (Wilson, Megel, Enenbach, et al, 2010).

Although school-age children are better able to cope with separation in general, the stress and often accompanying regression imposed by illness or hospitalization may increase their need for parental security and guidance. This is particularly true for young school-age children who have only recently left the safety of the home and are struggling with the crisis of school adjustment. Middle and late school-age children may react more to the separation from their usual activities and peers than to absence of their parents. These children have a high level of physical and mental activity that frequently finds no suitable outlets in the hospital environment. Even when they dislike school, they admit to missing its routine and associated activities and worry that they will not be able to compete or “fit in” with their classmates on returning to school. Feelings of loneliness, boredom, isolation, and depression are common. Such reactions may occur more as a result of separation than from concern over the illness, treatment, or hospital setting.

School-age children may need and desire parental guidance or support from other adult figures, but be unable or unwilling to ask for it. Because the goal of attaining independence is so important in this age-group, they are reluctant to seek help directly for fear that they will appear weak, childish, or dependent. Cultural expectations to “act like a man” or to “be brave and strong” bear heavily on these children, especially boys, who tend to react to stress with stoicism, withdrawal, or passive acceptance. Often the need to express hostility, anger, or other negative feelings finds alternate outlets, such as irritability and aggression toward parents, withdrawal from hospital personnel, inability to relate to peers, rejection of siblings, or subsequent problems in school.

For adolescents, separation from home and parents may be difficult. However, loss of peer-group contact may be a severe emotional threat because of loss of group status, inability to exert group control or leadership, and loss of group acceptance. Deviations within peer groups are poorly tolerated, and although members may express concern for the adolescent’s illness or need for hospitalization, they continue their group activities, quickly filling the gap of the absent member. During the temporary separation from their usual group, ill adolescents may benefit from group associations with other hospitalized teenagers.

Loss of Control

The amount of perceived control that children have in the hospital environment directly influences the amount of stress imposed by hospitalization. Lack of control increases the perception of threat and can affect children’s coping skills. Many hospital situations decrease the amount of control a child feels. Although the usual sensory stimulations are lacking, the additional hospital stimuli of sight, sound, and smell may be overwhelming. Without an insight into the type of environment conducive to children’s optimum growth, the hospital experience can at best temporarily slow development and at worst permanently retard it. Because the needs of children vary greatly depending on their age, the major areas of loss of control in terms of physical restriction, altered routine or rituals, and dependency are discussed for each age-group.

Infants

Infants are developing the most important attribute of a healthy personality, trust. Trust is established through consistent, loving care by a nurturing person. Infants attempt to control their environment through emotional expressions, such as crying or smiling. In the hospital setting, cues may be missed or misinterpreted, and routines may be established to meet the hospital staff’s needs instead of the infant’s needs. Inconsistent care and deviations from the infant’s daily routine may lead to mistrust and a decreased sense of control.

Toddlers

Toddlers are striving for autonomy, and this goal is evident in most of their behaviors: motor skills, play, interpersonal relationships, activities of daily living, and communication. When their egocentric pleasures meet with obstacles, toddlers react with negativism, especially temper tantrums. Any restriction or limitation of movement, such as the simple act of laying toddlers on their backs, can cause forceful resistance and noncompliance.

Loss of control also results from altered routines and rituals. Toddlers rely on the consistency and familiarity of daily rituals to provide a measure of stability and control in their life. The experience of hospitalization or illness severely limits their sense of expectation and predictability, since practically every detail of the hospital environment differs from that of home.

Toddlers’ main areas for rituals include eating, sleeping, bathing, toileting, and play. When the routines are disrupted, difficulties can occur in any or all of these areas. The principal reaction to such change is regression. For example, when mealtime and food choices differ from those at home, toddlers often refuse to eat, demand a bottle, or request that others feed them. Although regression to earlier forms of behavior may seem to increase toddlers’ security and comfort, in reality it is threatening for them to relinquish their most recently acquired achievements.

Enforced dependency is a chief characteristic of the sick role and accounts for the numerous instances of toddler negativism. For example, rigid schedules, altered caregiving activities, unfamiliar surroundings, separation from parents, and medical procedures take over toddlers’ control over their world. Although most toddlers initially react negatively and aggressively to such dependency, prolonged loss of autonomy may result in passive withdrawal from interpersonal relationships and regression in all areas of development. Therefore the effects of the sick role are most severe in instances of chronic, long-term illnesses or in families that foster the sick role despite the child’s improved state of health.

Preschoolers

Preschoolers also suffer from loss of control caused by physical restriction, altered routines, and enforced dependency. However, their specific cognitive abilities, which make them feel all powerful, also make them feel out of control. This loss of control in the context of their sense of self-power is a critical factor influencing their perception of and reaction to separation, pain, illness, and hospitalization.

Preschoolers’ egocentric and magical thinking limits their ability to understand events because they view all experiences from their own self-referenced perspective. Without adequate preparation for unfamiliar settings or experiences, preschoolers’ fantasy explanations are usually more exaggerated, bizarre, and frightening than the facts. One typical fantasy to explain the reason for illness or hospitalization is that it represents punishment for real or imagined misdeeds. In response to such thinking the child usually feels shame, guilt, and fear.

Preschoolers’ preoperational thinking means that they understand explanations only in terms of real events. Verbal instructions are often inadequate because of their inability to abstract and synthesize beyond what their senses tell them. When combined with their egocentric and magical thinking, this characteristic may lead them to interpret messages according to their particular past experiences. Even with the best preparation for a procedure, they may misconstrue the details.

Transductive reasoning implies that preschoolers deduce from the particular to the particular, rather than from the specific to the general, or vice versa. For example, if preschoolers’ concept of nurses is that they inflict pain, preschoolers will think that every nurse or caregiver will also inflict pain.

School-Age Children

Because of their striving for independence and productivity, school-age children are particularly vulnerable to events that may lessen their feeling of control and power. In particular, their loss of control may stem from altered family roles; physical disability; and fears of death, abandonment, or permanent injury. Loss of peer acceptance, lack of productivity, and inability to cope with stress according to perceived cultural expectations can also reduce their feelings of control.

Because of the nature of the patient role, many routine hospital activities take priority over individual power and identity. For these children, dependent activities such as enforced bed rest, use of a bedpan, inability to choose meals, lack of privacy, help with a bath, or transport by a wheelchair or stretcher can be a direct threat to their security. Although all these procedures seem routine and inconsequential, they allow no freedom of choice to children who want to “act grown-up.” However, when children are allowed to exert a measure of control, regardless of how limited it may be, they generally respond well to any procedure. For example, some of the most cooperative, satisfied, and contented patients are school-age children who help make their beds, choose their schedule of activities, and assist in procedures. An increased sense of control usually results from a feeling of usefulness and productivity.

In addition to the hospital environment, illness may also cause a feeling of loss of control. One of the most significant problems of children in this age-group is boredom. When physical or enforced limitations curtail their usual abilities to care for themselves or to engage in favorite activities, school-age children generally respond with depression, hostility, or frustration. Keeping a normally active child confined to a small hospital room or on bed rest is difficult. However, emphasizing areas of control and capitalizing on quiet activities, particularly hobbies such as building models or playing appropriate video and computer games, promote their adjustment to physical restriction.

Adolescents

Adolescents’ struggle for independence, self-assertion, and liberation centers on the quest for personal identity. Anything that interferes with this poses a threat to their sense of identity and results in a loss of control. Illness, which limits one’s physical abilities, and hospitalization, which separates one from usual support systems, constitutes major situational crises (see Family-Centered Care box).

The patient role fosters dependency and depersonalization. Adolescents may react to dependency with rejection, uncooperativeness, or withdrawal. They may respond to depersonalization with self-assertion, anger, or frustration. Regardless of which response they manifest, hospital personnel often regard them as difficult, unmanageable patients. Parents may not be a source of help, since these behaviors further isolate them from understanding the adolescent. Although peers may visit, they may not be able to offer the type of support and guidance needed. Sick adolescents often voluntarily isolate themselves from age-mates until they think they can compete on an equal basis and meet group expectations. As a result, ill adolescents may be left with virtually no support system.

Loss of control also occurs for many of the reasons discussed for school-age children. However, adolescents are more sensitive than younger children to potential instances of loss of control and dependency. For example, both groups seek information about their physical status and rely heavily on anticipatory preparation to decrease fear and anxiety. Adolescents, however, react not only to information supplied them, but also to the means by which it is conveyed. They may feel threatened by others who relate facts in a condescending manner. Adolescents want to know that others can relate to them on their own level. This necessitates a careful assessment of their intellectual abilities, previous knowledge, and present needs. It may also require the nurse to learn the adolescent’s language.

Bodily Injury and Pain

Fears of bodily injury and pain are prevalent among children. The consequences of these fears can be far-reaching. Adults who experience more medical fear and pain in childhood are more fearful of medical pain as adults and tend to avoid medical care (Justus, Wyles, Wilson, et al, 2006; Brewer, Gleditsch, Syblik, et al, 2006).

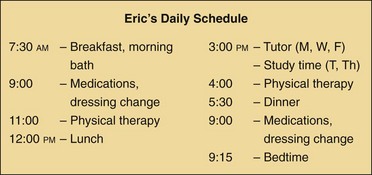

In caring for children, nurses must appreciate their concerns about bodily harm and the reactions to pain at different developmental periods. Table 26-1 summarizes developmental considerations related to children’s understanding of illness and pain.

TABLE 26-1

CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENTAL CONCEPTS OF ILLNESS AND PAIN

*From Bibace R, Walsh ME: Development of children’s concepts of illness, Pediatrics 66(6):912-917, 1980.

†From Hurley A, Whelan EG: Cognitive development and children’s perception of pain, Pediatr Nurs 14(1):21-24, 1988.

Infants

Newborns and infants undergo a significant number of painful events related to hospitalization. These can include blood draws, lumbar punctures, urinary catheterization, and intravenous (IV) line insertions. The infant’s response to pain varies markedly in measures of distress, especially initial cry and heart rate, which may decrease in some infants. The most consistent indicator of distress is a facial expression of discomfort (Fig. 26-3). Infants may express pain physically by actions such as squirming or flailing (Franck, Greenberg, and Stevens, 2000). Some infants may cry loudly after the procedure, whereas a gentle hug may calm others easily. It is important to recognize and respect such early signs of individuality and to realize that children who react less intensely may still be experiencing significant discomfort.

Fig. 26-3 Facial expressions reflect distress and are consistent behavioral indicators of pain in infants. (Courtesy E. Jacob, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Infants younger than 6 months of age seem to have no obvious memory of previous painful experiences and may react to a potentially stressful situation with less apprehension and fear than older children. Research has found that infants have stored memories of acute pain experiences (such as repeated heelsticks) and react in subsequent painful events with heightened responses to pain (Taddio, Shah, Gilbert-MacLeod, et al, 2002; Taddio and Katz, 2005). There is also evidence that repeated painful procedures can alter brain structure and behavioral and hormonal response to pain (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000; Anand and Scalzo, 2000).

After 6 months of age, children’s response to pain is influenced by their memory of prior painful experiences and the emotional reaction of parents during the procedure. Older infants react intensely with physical resistance and uncooperativeness. They may refuse to lie still, attempt to push the person away, or try to escape with whatever motor activity they have achieved. Distraction does little to lessen their immediate reaction to pain, and anticipatory preparation, such as showing them the equipment, tends to increase their fear and resistance.

Toddlers

Toddlers’ concept of body image, particularly the definition of body boundaries, is poorly developed. Intrusive experiences, such as examining the ears or mouth or taking a rectal temperature, produce anxiety. Toddlers may react to such painless procedures as intensely as they do to painful ones.

Toddlers’ reactions to pain are similar to those seen during infancy, except that the variables influencing the individual response are highly complex and varied. Memory, physical restraint, separation from the parent or guardian, emotional reactions of others, and lack of preparation partially determine the intensity of the behavioral response. In general, children in this age-group continue to react with intense emotional upset and physical resistance to any actual or perceived painful experience. Behaviors indicating pain include grimacing; clenching the teeth or lips; opening the eyes wide; rocking; rubbing; and aggressiveness, such as biting, kicking, hitting, or running away. Unlike adults, who usually decrease their activity when in pain, young children typically become restless and overactive; frequently this response is not recognized as a consequence of pain.

By the end of this age period, toddlers usually are able to communicate about their pain. Although they have not developed the ability to describe the type or intensity of the pain, they usually are able to localize it by pointing to a specific area.

Preschoolers

Concepts of illness begin during the preschool period and are influenced by the cognitive abilities of the preoperational stage. Preschoolers differentiate poorly between themselves and the external world. Their thinking is focused on externally perceived events, and causality is based on the proximity of two events. Consequently, children define illness according to what they are told or are given external evidence of, such as “You are sick because you have a fever.” The cause of illness is a concrete action the child does or fails to do, such as “catching a stomach virus because you don’t wash your hands.” Consequently, illness implies a degree of responsibility and self-blame. Another explanation may be based on contagion, that is, the proximity of two objects or persons causes the illness (e.g., “A person gets a cold when someone else with a cold gets near him”).

The psychosexual conflicts of children in this age-group make them vulnerable to threats of bodily injury. Intrusive procedures, whether painful or painless, are threatening to preschoolers, whose concept of body integrity is still poorly developed. Preschoolers may react to an injection with as much concern for withdrawal of the needle as for the actual pain. They fear that the intrusion or puncture will not close and that their “insides” will leak out.

Concerns of mutilation are paramount during this age period. Loss of any body part is threatening, but preschool boys’ fears of castration complicate their understanding of surgical or medical procedures associated with the genital area, such as circumcision, repair of hypospadias or epispadias, cystoscopy, or catheterization. Their limited comprehension of body functioning also increases their difficulty in understanding how or why body parts are “fixed.” For example, telling preschoolers that their tonsils are to be removed may be interpreted as “taking out their voice.” Preschoolers understand words such as dye, cut off, take out, or draw (as in “draw some blood”), and using these words can lead to confusion and fear. (See Communicating with Children, Chapter 6.)

Reactions to pain tend to be similar to those seen during toddlerhood, although some differences become apparent. For example, preschoolers respond more favorably to preparatory interventions, such as explanation and distraction, than younger children. Physical and verbal aggression is more specific and goal directed. Instead of showing total body resistance, preschoolers may push the offending person away, try to secure the equipment, or attempt to lock themselves in a safe place. Much more thought is evident in their plan of attack or escape.

Verbal expression in particular demonstrates their advanced development in response to stress. They may verbally abuse the attacker by stating, “Go away” or “I hate you.” They may also use the more cunning approach of trying to persuade the person to delay the intended activity. A common plea is “I have to go to the bathroom.” Some statements are not only attempts to avoid the event but also evidence of children’s perceptions about the experience.

School-Age Children

Fears of the physical nature of the illness surface at this time. School-age children may be less concerned with pain than with disability, uncertain recovery, or possible death. Because of their developing cognitive abilities, school-age children are aware of the significance of different illnesses, the indispensability of certain body parts, potential hazards in treatment, lifelong consequences of permanent injury or loss of function, and the meaning of death. A major concern of hospitalized school-age children is their fear of being told that something is wrong with them. They generally take an active interest in their health or illness. Even those children who rarely ask questions usually accumulate detailed information on their condition by attentively listening to all that is said around them. They request factual information and quickly perceive lies or half-truths. Seeking information tends to be one way they maintain a sense of control despite the stress and uncertainty of illness.

School-age children define illness by a set of multiple concrete symptoms, such as signs of a cold, and view the cause as primarily germs or bacteria. The germs have a powerful, almost magical quality, so that in the child’s mind, illness can be prevented by avoiding people with the germs. They also believe in the idea of contamination, which is similar to that seen in the younger age-group. For example, the illness occurs because of physical contact or because the child engaged in a harmful action and became contaminated. Consequently, feelings of self-blame and guilt may be associated with the reason for becoming ill.

School-age children begin to show concern for the potential beneficial and hazardous effects of procedures. Besides wanting to know if a procedure will hurt, they want to know what it is for, how it will make them well, and what injury or harm could result. For example, these children fear the actual procedure of anesthesia. Unlike preschoolers, who fear the mask and the strange surroundings, school-age children fear what might happen while they are asleep, whether they will wake up, and whether they might die. Preadolescents also worry about the procedure itself, particularly one that will result in visible changes in body appearance.

Intrusive procedures, such as routine physical examination of the ears, nose, mouth, and throat, are generally well tolerated. However, concerns for privacy become increasingly significant. Although school-age children may cooperate during examination of, or procedures performed on, the genital area, it is usually stressful for them, especially for preadolescents who are beginning pubertal changes. Nurses who respect children’s need for privacy can provide them with assurance and support.

By the age of 9 or 10, most school-age children show less fright or overt resistance to pain than younger children. They generally have learned passive methods of dealing with discomfort, such as holding rigidly still, clenching their fists or teeth, or trying to act brave. If they display signs of overt resistance, such as biting, kicking, pulling away, trying to escape, crying, or plea bargaining, they may deny such reactions later, especially to their peers, for fear of embarrassment.

School-age children verbally communicate about their pain in respect to its location, intensity, and description. Unlike younger children, who may have difficulty choosing words to describe pain, children 8 years and older (like adults) use a wide variety of words and phrases, such as hurting, sore, burning, stinging, and aching (Franck, Greenberg, and Stevens, 2000).

School-age children also use words as a means of controlling their reactions to pain. For example, these children may ask the nurse to talk to them during a procedure. Some prefer to participate in a procedure, whereas others choose to distance themselves by not looking at what is happening. Most appreciate an explanation of the procedure and seem less fearful when they know what to expect. Others try to gain control by attempting to postpone the event. A typical request is, “Start the IV when I am finished with this.” Although the ability to make decisions does increase their sense of control, unlimited procrastination and bargaining result in heightened anxiety. When choices are allowed, such as which arm for the IV line, it is best to structure the number of options and to limit the number of procrastination or bargaining techniques. Nurses must also exercise caution when asking the child to make choices to ensure that the choice can be honored.

Similar to their more passive acceptance of pain is their nondirective request for support or help. School-age children rarely initiate a conversation about their feelings or ask someone to stay with them during a lonely or stressful period. Their visible composure, calmness, and acceptance often mask their inner longing for support. It is especially important to be aware of nonverbal clues, such as a serious facial expression, a halfhearted reply of “I am fine,” silence, lack of activity, or social isolation, as signs of the need for help. Usually when someone identifies the unspoken messages and offers support, they readily accept it.

Adolescents

Although the development of body image begins early in life, its relevance is paramount during adolescence. Injury, pain, disability, and death are viewed primarily in terms of how each affects adolescents’ views of themselves in the present. Any change that differentiates the adolescent from peers is regarded as a major tragedy. For example, chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus often present a more difficult adjustment period for children in this age-group than for younger children because of the necessary changes in lifestyle. Conversely, serious, even life-threatening illnesses that entail no visible bodily changes or physical restrictions may have less immediate significance for the adolescent. Therefore the nature of bodily injury may be more important in terms of adolescents’ perception of the illness than its actual degree of severity.

Adolescents’ rapidly changing body image during pubertal development often makes them feel insecure about their bodies. Illness, medical or surgical intervention, and hospitalization increase their existing concerns for normalcy. They may respond to such events by asking numerous questions, withdrawing, rejecting others, or questioning the adequacy of care. Frequently their fear for loss of control and body image change is demonstrated as overconfidence.

Because of the development of secondary sexual characteristics, adolescents are concerned about privacy. Lack of respect for this need can cause greater stress than physical pain. In addition, adolescents look for signs that indicate they are developing normally and according to acceptable standards. When illness occurs, they fear that growth may be retarded, leaving them behind their peers. Although they may not voice this concern, they may demonstrate it by carefully observing others’ reactions to them.

Adolescents typically react to pain with much self-control. Physical resistance and aggression are unusual at this age, unless the adolescents are unprepared for a procedure. As with older school-age children, they are concerned with remaining composed and feel embarrassed and ashamed of losing control. They are able to describe their pain experience and to use the pain assessment tools developed for adults. However, they may be reluctant to disclose their pain, requiring the nurse to listen closely and observe physical indications, such as limited movement, excessive quiet, or irritability. Adolescents may also believe that the nurse knows how they feel; thus they may see no need to ask for analgesia.

Effects of Hospitalization on the Child

Children may react to the stresses of hospitalization before admission, during hospitalization, and after discharge (Box 26-2). A child’s conception of illness is even more important than age and intellectual maturity in predicting the level of adjustment before hospitalization. This may or may not be affected by the duration of the condition or prior hospitalizations. Therefore nurses should avoid making incorrect assumptions regarding the illness concepts of children with prior medical experience.

Individual Risk Factors

A number of risk factors make some children more vulnerable than others to the stresses of hospitalization (Box 26-3). Because separation is such an important issue surrounding hospitalization for young children, children who are active and have a strong will tend to fare better when hospitalized than youngsters who are passive. Nurses should be alert to children who passively accept all changes and requests, since these children may need more support than the “oppositional” child.

The stressors of hospitalization may cause young children to experience short- and long-term negative outcomes. Adverse outcomes may be related to the length and number of admissions, multiple invasive procedures, and parents’ anxiety. Common responses include regression, separation anxiety, apathy, fears, and sleep disturbances, especially for children younger than 7 years of age (Melnyk, 2000). Supportive practices, such as family-centered care, frequent family visits, and mothers who know exactly how they can be involved in their child’s care, may lessen the detrimental effects of hospitalization. Research also indicates that the child’s pain experience determines how the child will experience the overall hospitalization. Consequently, nurses should attempt to identify children who are at risk for poor coping outcomes (Small, 2002).

Changes in the Pediatric Population

Children are hospitalized for different reasons today than two decades ago. Despite the growing trend toward shortened hospital stays and outpatient surgery, a greater percentage of the children hospitalized today have more serious and complex problems than those hospitalized in the past. Many of these children are medically fragile newborns and children with severe injuries or disabilities who survived because of incredible technologic advances, yet were left with chronic or disabling conditions that require frequent and lengthy hospital stays. The nature of their conditions increases the likelihood that this group of children will experience more invasive and traumatic procedures while they are hospitalized. These factors make them more vulnerable to the emotional consequences of hospitalization and result in their needs being significantly different from those of short-term patients. (See Chapter 22 for further discussion on children with special needs.) The majority of these children are infants and toddlers, the age-group most vulnerable to the effects of hospitalization.

Concern in recent years has focused on the increasing length of hospitalization because of complex medical and nursing care, elusive diagnoses, and complicated psychosocial issues. Without special attention devoted to meeting the child’s psychosocial and developmental needs in the hospital environment, the damaging consequences of prolonged hospitalization may be severe.

Beneficial Effects of Hospitalization

Although hospitalization can be and usually is stressful for children, it can also be beneficial. The most obvious benefit is the recovery from illness, but hospitalization also can present an opportunity for children to master stress and feel competent in their coping abilities. The hospital environment can provide children with new socialization experiences that can broaden their interpersonal relationships. The psychologic benefits need to be considered and maximized during hospitalization. Appropriate nursing strategies to achieve this goal are presented later in this chapter.

Stressors and Reactions of the Family of the Child Who is Hospitalized

The crisis of childhood illness and hospitalization is a major source of stress and anxiety for every member of the nuclear family. Parents’ reactions to their child’s illness depend on a variety of factors. Although one cannot predict which factors are most likely to influence their response, a number of variables have been identified (Box 26-4).

Fear, anxiety, and frustration are common feelings expressed by parents. Fear and anxiety may be related to the seriousness of the illness and the type of medical procedures involved. Anxiety is frequently related to the trauma and pain inflicted on the child from the various procedures. Parents may question why they and their child have to go through this experience, as well as the purpose of pain and suffering (Feudtner, Haney, and Dimmers, 2003). Frustration is often related to lack of information about procedures and treatments, unfamiliarity with hospital rules and regulations, unfriendly staff, or fear of asking questions. Nurses can alleviate much frustration in the pediatric unit by making parents aware of what to expect and what is expected of them, encouraging them to participate in their child’s care, and treating them as the most significant contributors to the child’s total health.

Parents eventually may react with some degree of depression. Mothers often comment on their feeling of physical and mental exhaustion after all the other family members have adapted to the crisis. Parents may also worry about and miss their other children, who may be left in the care of family, friends, or neighbors. Other reasons for anxiety and depression are related to concerns for the child’s future well-being, including negative effects produced by the hospitalization and any subsequent financial burden incurred.

In a retrospective database survey of more than 50,000 parents of a hospitalized child, parents identified seven priorities from their perspective to improve the care of the hospitalized child (Miceli and Clark, 2005). The parents’ highest priority was to improve staff’s sensitivity to the disruption and inconvenience of the child being hospitalized. Additional leading suggestions included improving the degree to which hospital staff address the family’s emotional and spiritual needs during the child’s hospitalization, improving staff’s response when parents express concerns or voice complaints during the child’s stay, including parents in decisions regarding treatments, improving visitor (family) accommodations and comfort, providing information about nearby services and lodging facilities for family members, and improving staff concerns to make the child’s stay as restful and comfortable as possible. In each of the seven categories the researchers provide additional issues parents raised in relation to the primary theme.

Studies highlight the need for family-centered nursing care that considers the effects of hospitalization on the child and the parents (Miceli and Clark, 2005; Stratton, 2004; Feudtner, Haney, and Dimmers, 2003). Hospital staff members must continually assess the parents’ need for information and reassurance. Although the child’s care may take precedence over parents’ needs, nurses must make every effort to improve parent coping to optimize patient outcomes. By maintaining sensitivity to the family’s needs, the nurse can become equal partners with parents in the child’s care.

Sibling Reactions

Siblings’ reactions to a sister’s or brother’s illness or hospitalization are discussed in Chapters 22 and 23 and differ little when a child has an acute illness. Siblings may experience loneliness, fears, and worry. Siblings frequently fear acquiring the illness of their ill sibling. Behavioral reactions include anger, resentment, jealousy, and guilt. Various factors have been identified that influence the siblings’ reactions to the child’s hospitalization. Although these factors are similar to those seen when a child has a chronic illness, Craft (1993) reported that the following factors are related specifically to the hospital experience and have been found to increase the effects on the sibling:

• Being younger and experiencing many changes

• Being cared for outside the home by care providers who are not relatives

• Receiving little information about their ill brother or sister

• Perceiving their parents as treating them differently compared with before their sibling’s hospitalization

Parents are often unaware of the effect on siblings of a sick child’s hospitalization and of the benefit of simple interventions to minimize such effects, such as explicit explanations about the illness and provisions for the siblings to remain at home. Sibling visitation is advocated and is usually advantageous. However, unless siblings are prepared for what they may see, their visits may confuse them, leaving room for greater anxiety and worry when they are home, away from their hospitalized brother or sister. Siblings need to be given developmentally appropriate information about their sibling’s illness or injury and be given an opportunity to ask questions.

Altered Family Roles

In addition to the effects of separation on family roles, loss of the parent and sibling roles may affect each family member differently. One of the most common reactions of parents is intensified attention toward the sick child. The other siblings may regard this as unfair and interpret the parents’ attitude toward them as rejection and abandonment. Although such responses are usually unconscious and unintended, they place unique burdens on ill children. For example, the ill child may feel obligated to play the sick role to meet parents’ expectations, especially in the case of children who have had limited physical ability and regain normal health status, such as following corrective heart surgery. Parents also may have difficulty perceiving the child’s recovery and therefore continue the pattern of overprotection and indulgent attention.

Ill children may also feel jealousy and resentment from siblings. Because of their singular position in the family, they may be denied the companionship of their brothers and sisters. Rivalry tends to be greatest with the sibling who is nearest the ill child’s age. Without an understanding of the interpersonal dynamics between siblings, parents are likely to blame the well children for antisocial behavior. Illness may also result in a child’s loss of status within either the family or peer group. For example, illness in the oldest child may temporarily terminate special privileges as “big” brother or sister.

Nursing Care of the Child Who is Hospitalized

Children and their families require competent and sensitive care to minimize the potential negative effects of hospitalization and also to promote positive benefits from the experience. Interventions should focus on (1) eliminating or minimizing the stressors of separation, loss of control, and bodily injury and pain for children; and (2) providing specific supportive strategies for family members, such as fostering family relationships and providing information.

Initiate a family assessment using the guidelines in Box 26-7. Assess the parents and other immediate family members for coping and for special assistance needs (e.g., temporary child care for siblings, lodging, meals, and transportation to and from hospital).

Preventing or Minimizing Separation

A primary nursing goal is to prevent separation, particularly in children under 5 years of age. Hospitals no longer consider parents “visitors” and welcome their presence at all times throughout the child’s hospitalization. Many hospitals have adopted a philosophy of family-centered care, which recognizes the integral role of the family in a child’s life and acknowledges the family as an essential part of the child’s care and illness experience. In the broadest sense, the family is considered to be partners in the care of the child (Smith and Conant Rees, 2000). Emphasis is placed on providing services that demonstrate the value of collaboration between the health care provider, the child, and the family. Many hospitals provide a chair or bed for at least one person per child, unit kitchen privileges, and other amenities that create a welcoming atmosphere for parents. Still, the parents’ own schedules may prevent them from being present. In such instances, strategies to minimize the effects of separation must be implemented.

Parent Participation

Although some health facilities provide special accommodations for parents, the concept of family-centered care can be instituted anywhere. The first requirement is the staff’s positive attitude toward parents. A negative attitude toward parent participation can create barriers to collaborative working relationships (Smith and Conant Rees, 2000). Unfortunately, although nurses often express explicit support for the concept of family-centered care, some of their practices and beliefs suggest otherwise (Newton, 2000).

Hospital staff who genuinely appreciate the importance of continued parent-child attachment foster an environment that encourages parents to be active caregivers. When nurses include parents in the care planning and ensure them that they are contributing to the child’s recovery, parents are more inclined to remain with their child and have more emotional reserves to support themselves and the child through the crisis. An empowerment model of helping allows the nurse to focus on parents’ strengths and to seek ways to promote growth and family functioning (Fig. 26-4). Strategies such as bedside reporting that allow parents to be involved in the discussion of the child’s current status are moving health care settings closer to family-centered care (Anderson and Mangino, 2006). Liaison nursing roles in tertiary care settings are also focused on improving communication between parents and health care providers (Caffin, Linton, and Pellegrini, 2007).

Fig. 26-4 Family presence during hospitalization, including during procedures, provides emotional support. (Courtesy Paul Vincent Kuntz, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Parents may display different and varied needs regarding involvement in their child’s care. Not all parents feel comfortable assuming responsibility, and they may be under such great emotional stress that they need a temporary reprieve from caregiving activities. Others may feel insecure in participating in specialized care. On the other hand, some parents may feel a need to control their child’s care and wish to be involved in every way possible. Individual assessment of each parent’s preferred involvement is necessary to prevent the effects of separation while supporting parents’ needs. Because the mother tends to be the usual family caregiver, she may spend more time in the hospital than the father (Fig. 26-5). Fathers need to be included in the care plan and respected for their parental role. For some fathers, the child’s hospitalization may represent an opportunity to alter their usual caregiving role and increase their involvement. In single-parent families the caregiver may not be a parent but an extended family member, such as a grandparent or aunt. Parents and other family members should be prepared and supported for the roles they choose.

Fig. 26-5 Despite changing lifestyles and gender roles, mothers tend to be the usual family caregiver and spend more time at the hospital than fathers.

One of the potential problems with continuous parent visitation is that the parent often neglects the need for sleep, nutrition, and relaxation. The sleeping accommodations may be limited to a chair, and sleep is disrupted by nursing procedures. After a few days, parents may become exhausted but feel obligated to stay at their child’s bedside. Encouraging them to leave for brief periods, arranging for sleeping quarters on the unit but outside the child’s room, and planning a schedule of alternating visitation with the other parent or with a family member can minimize the stresses for the parent.

All too often, nurses respond to parental participation by abandoning their patient responsibilities. Nurses need to restructure their roles to complement and augment the parents’ caregiving functions and to promote family health (Hopia, Tomlinson, Paavilainen, et al, 2005). Even in units structured to promote care by parents, parents frequently feel anxiety in their caregiving responsibilities. Those more involved in direct care may feel greater anxiety than those less involved. A moderate amount of visitation and participation may be optimum for many. Nursing assistance should always be available to these families.

Strategies to Minimize the Effects of Separation

When separation cannot be prevented, the nurse can employ numerous strategies to minimize the effects of temporary separation on children. Ideally, a primary nurse is assigned to meet the child’s needs. The nurse should obtain a thorough, detailed history that specifically identifies the child’s daily routine (see Box 26-7, p. 988). Usual daily activities such as meal preparation and method of feeding help establish a complementary schedule of caregiving practices. It also helps the parents feel as though they are participating in the child’s care but through another person. A consistent staff member can also keep the family informed of the child’s condition and support the family’s concerns and priorities.

The nurse caring for the child must be aware of the child’s separation behaviors. As discussed earlier, phases of protest and despair are normal. The child is allowed to cry. Even if the child rejects strangers, the nurse provides support through physical presence. This includes spending time being physically close to the child, using a quiet tone of voice, appropriate words, eye contact, and touch in ways that establish rapport and communicate empathy. If detachment behaviors are evident, the nurse maintains the child’s contact with the parents by frequently talking with them; encouraging the child to remember them; and stressing the significance of their visits, telephone calls, or letters.

Separation may be equally difficult for parents, especially when they do not understand the behaviors of separation anxiety. To avoid the immediate protest, parents may sneak out or lie to the child about leaving. As a result, the child does not learn to associate absence with a guaranteed return because there is an element of uncertainty. Helping parents recognize that separation behaviors are normal and expected can decrease anxiety and may ease their fears about leaving the child. Explaining to parents how the child reacts after they leave may also be helpful. Many parents think the child cries for hours after they leave, whereas in reality the child may cry for a few minutes but then settle down when comforted by someone else.

Toddlers and preschoolers have a limited concept of time. Time is measured in associations, such as “eating dinner when daddy comes home.” Therefore, when helping parents with their fears of separation, nurses need to suggest ways of explaining leaving and returning. For example, if parents must leave to go to work or to make meals for the other family members, they should tell the hospitalized child the reason for leaving. They also need to convey the expected time of return in terms of anticipated events. For example, if the parents return in the morning, they can tell the child that they will see him or her “when it’s time for breakfast” or “when [a favorite program] is on television.”

The young child’s ability to tolerate parental absence is limited. Therefore parental visits should be frequent. For example, it is better for parents to visit three times a day for short periods than once a day for an extended time. This may necessitate that each parent visit at different times to lessen the length of separation. When parents cannot visit, the presence of other significant people may comfort the child (Fig. 26-6).

Fig. 26-6 When parents cannot visit, other significant persons can provide comfort to the hospitalized child.

If parents leave after the child is asleep, they still need to communicate their absence. The parents of a 5-year-old boy solved this problem by devising a sign; on one side they drew a picture of a telephone and on the other a hamburger. Before they left, they turned the sign to the appropriate side to tell the child when he awoke that they were out using the telephone or eating.

For older children who know how to tell time, it is helpful to give them a clock or watch. However, these children have the same needs for honesty from their parents regarding visiting schedules. Because peer groups are also important, adolescents often appreciate planning visiting hours to provide them with some private time for friends. Many hospitals today also offer Internet connectivity, which allows older children and adolescents to remain in contact with family members and peers via e-mail or social networking sites.

Familiar surroundings also increase the child’s adjustment to separation. If parents cannot stay with the child, they should leave favorite articles from home, such as a blanket, toy, bottle, feeding utensil, or article of clothing. Because young children associate such objects with significant people, they gain comfort and reassurance from these possessions. They make the association that, if the parent left this, the parent will surely return. Other mementos of home include photographs and recordings of family members reading a story, singing a song, or relating events at home. Some units allow pets to visit, which can be a special event for a child and can have therapeutic benefits.

Older children also appreciate familiar articles from home, particularly photographs, a favorite toy or game, and their own pajamas. The importance of treasured objects for school-age children may be overlooked or criticized. However, approximately half of school-age children have a special object to which they formed an attachment in early childhood. This is a normal and healthy phenomenon. Therefore such treasured or transitional objects can help even older children feel more comfortable in a strange environment.

The sights and sounds in the hospital that are commonplace for the nurse can be strange, frightening, and confusing for children. It is important for the nurse to try to evaluate stimuli in the environment from the child’s point of view (considering also what the child may see or hear happening to other patients) and to make every effort to protect the child from frightening and unfamiliar sights, sounds, and equipment. The nurse should offer explanations or prepare the child for those experiences that are unavoidable. Combining familiar or comforting sights with the unfamiliar can relieve much of the harshness of medical care.

Helping children maintain their usual contacts also minimizes the effects of separation imposed by hospitalization. This includes continuing school lessons during the illness and confinement, visiting with friends either directly or through e-mail, and participating in stimulating projects whenever possible (Fig. 26-7). For extended hospitalizations, youngsters enjoy personalizing the hospital room to make it “home” by decorating the walls with posters and cards and rearranging the furniture (when possible).

Minimizing Loss of Control and Autonomy

Feelings of loss of control result from separation, physical restriction, changed routines, enforced dependency, magical thinking, and altered roles within the family or peer group. Although some of these cannot be prevented, most can be minimized through individualized nursing care.

Promoting Freedom of Movement

Younger children react most strenuously to any type of physical restriction or immobilization. Although some restraint may be necessary, such as temporarily immobilizing an extremity for maintenance of an IV line, most physical restriction can be avoided if the nurse gains the child’s cooperation.

For young children, particularly infants and toddlers, preserving parent-child contact is the best means of decreasing the need for or stress of restraint. For example, the nurse can perform almost the entire physical examination with the child in a parent’s lap, with the parent hugging the child for procedures such as otoscopy. For painful procedures the nurse assesses the parents’ preferences for assisting, observing, or waiting outside the room.

Environmental factors may restrict movement. Keeping children in cribs or playpens may not represent immobilization in the strictest sense, but it certainly limits sensory stimulation. Increasing mobility by transporting children in carriages, wheelchairs, carts, or wagons provides them with a sense of freedom.

In some cases physical restraint or isolation is necessary. Whenever possible, remove restraints to allow the child some period of supervised freedom, such as during baths or visits from parents. When restraints or isolation cannot be discontinued, such as with severe burns, the environment can be altered to increase sensory freedom. Moving the bed toward the door or window; opening window shades; providing musical, visual, or tactile toys; and increasing interpersonal contact can substitute mental mobility for the limitations of physical movement.

Maintaining the Child’s Routine

Altered daily schedules and loss of rituals are particularly stressful for toddlers and early preschoolers and may increase separation anxiety. As stated previously, the nursing admission history provides a baseline for planning care around the child’s usual home activities.

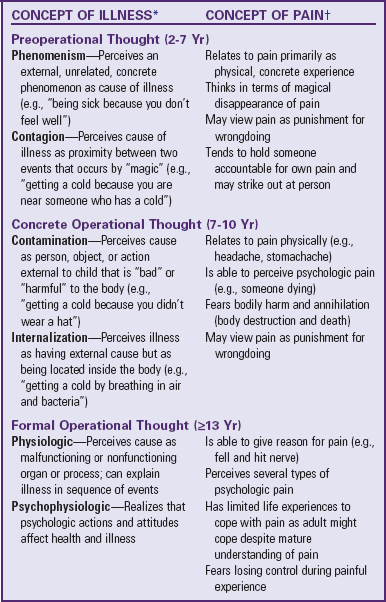

Children’s response to loss of routine and ritualism is often demonstrated in problems with activities such as eating, sleeping, dressing, bathing, toileting, and social interaction. Although some regression is expected, sensitivity to the child’s special needs can minimize the negative effects. For example, loss of appetite and marked food preferences are common in children who are ill or hospitalized. In addition, the food selections on hospital menus may differ greatly from preferred cultural or ethnic food preparation. Encouraging the child to eat is often a challenge, yet it is an essential nursing responsibility. Chapter 27 discusses suggestions for feeding sick children.

A frequently neglected aspect of altered routines is the change in the child’s daily activities. A nonhospitalized child’s day, especially during the school years, is structured with specific times for eating, dressing, going to school, playing, and sleeping. However, this time structure vanishes when the child is hospitalized. Although the nurses have a set schedule, the child is frequently unaware of it. Many children obtain significantly less sleep in the hospital than at home, primarily because sleep is delayed and then ends early due to hospital routines. Not only are hours of sleep disrupted, but waking hours are spent in passive activities. For example, few institutions impose any restrictions on the amount of time children spend watching television, which tends to be considerably more time than they spend watching at home.

One technique that can minimize the disruption in the child’s routine is establishing a daily schedule. This approach is most suitable for the noncritically ill school-age and adolescent child who has mastered the concept of time. It involves scheduling the child’s day to include all necessary activities that are important to patient care procedures, activities of daily living, mealtimes, and medications. Together, the nurse, parent, and child plan a daily schedule with times and activities written down, with blocks of free time available for playroom activities, hobbies, and television viewing (Fig. 26-8). The child is given a copy of the schedule and a clock. For lengthy hospitalizations, a calendar may be constructed identifying special events such as favorite television programs, visits by friends or relatives, events in the playroom, holidays or birthdays, and any expected changes in treatment (e.g., “beginning physical therapy in 2 days”).

Encouraging Independence

The dependent role of being hospitalized imposes feelings of loss on older children. Principal interventions should focus on respect for individuality and the opportunity for decision making. Although these sound simple, their efficacy depends on nurses who are flexible and tolerant. It is also important to empower the patient and not be threatened by a sense of lessened control.

Fostering children’s control involves helping them maintain independence and promoting self-care. Self-care refers to the practice of activities that individuals initiate and perform on their own behalf to maintain life, health, and well-being (Orem, 2001). Although self-care is limited by the child’s age and physical condition, most children beyond infancy can perform some activities with little or no help. Whenever possible, encourage these activities in the hospital. Other approaches include structuring time and allowing the child to jointly plan care, wear street clothes, make choices in food selections and bedtime, continue school activities, and room with an appropriate age-mate. For example, adolescents generally prefer a roommate their own age and, ideally, quarters separate from the pediatric unit.

Promoting Understanding

Loss of control can occur both from feelings of having too little influence on one’s destiny and from sensing overwhelming control or power over fate. Although preschoolers’ cognitive abilities predispose them most to creative thinking and delusions of power, all children are vulnerable to misinterpreting causes for stresses such as illness and hospitalization.

Most children feel more in control when they know what to expect, since this reduces the element of fear. Providing anticipatory preparation and information helps greatly to lessen stress and prevent misunderstanding. (See Preparation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures, Chapter 27.)

Informing children of their rights while hospitalized fosters greater understanding and may relieve some of the feelings of powerlessness they experience. Standards used to accredit hospitals recommend that hospitals providing services to children have a hospital-wide policy on the rights and responsibilities of these patients and of their parents or guardians (Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, 2004). Present information regarding patient rights to children and their families during the admission process.

Preventing or Minimizing Fear of Bodily Injury

Beyond early infancy all children fear bodily injury either from mutilation, intrusion, body image change, disability, or death. In general, preparation of children for painful procedures decreases their fears. Manipulating procedural techniques for children in each age-group also minimizes fear of bodily injury. For example, since toddlers and young preschoolers are traumatized by insertion of a rectal thermometer, axillary or tympanic electronic temperature probes can be effectively substituted. Whenever procedures are performed on young children, the most supportive intervention is to do them as quickly as possible and maintain parent-child contact.

Because of the toddler’s and preschooler’s poorly defined body boundaries, the use of bandages may be particularly helpful. For example, telling children that the bleeding will stop after the needle is removed does little to relieve their fears, whereas applying a Band-Aid usually reassures them. The size of bandages is also significant to children in this age-group. The larger the bandage, the more importance is attached to the wound. Successively smaller surgical dressings are one way they measure healing and improvement. Removing a dressing may cause them concern for their well-being.

In children who fear mutilation of body parts, repeatedly stressing the reason for a procedure and evaluating their understanding are essential to minimize fear. For example, explaining cast removal to preschoolers may seem simple enough, but the child’s comprehension of the details may vary considerably. Asking them to draw a picture of what they think will happen provides substantial evidence of how they perceive events.

Children may fear bodily injury from a great variety of sources. Diagnostic imaging machines, strange equipment for examinations, unfamiliar rooms, or awkward positions can be perceived as potentially hazardous. In addition, thoughts and actions can be imagined sources of bodily damage. Therefore it is important to investigate imagined reasons for illness. Children may fear revealing such thoughts, and techniques such as drawing or doll play may help reveal their misconceptions.

Older children fear bodily injury of both internal and external origins. For example, school-age children are aware of the heart’s significance and may fear an actual procedure involving the heart as much as the pain, the stitches, and the possible scar. Adolescents may express concern for the surgery but be much more anxious over the resulting scar. An appreciation of each child’s special concerns helps nurses focus on critical areas when preparing patients for procedures or explaining the disease processes.

Children can grasp information only if it is presented on or close to their level of cognitive development. This necessitates an awareness of the words used to describe events or processes. For example, young children told that they are going to have a CAT scan may wonder, “Will there be cats? Or something that scratches?” It is clearer to describe the procedure in simple terms and explain what the letters of the common name stand for.

When children are upset about their illness, the nurse can change their perception by (1) providing a somewhat different and less negative account of the disease or (2) offering an explanation that is characteristic of the next stage of cognitive development. An example of the first strategy is reassuring a preschool child who, after a tonsillectomy, fears that another sore throat means a second operation. Explaining that once tonsils are “fixed,” they do not need fixing again can help relieve the fear. An example of the second strategy is to explain that germs made the tonsils sick and even though germs can cause another sore throat, they cannot cause the tonsils to ever be sick again. This higher-level explanation is based on the school-age child’s concept of germs as a cause of disease.

Providing Developmentally Appropriate Activities

A primary goal of nursing care for the child who is hospitalized is to minimize threats to the child’s development. Many strategies (e.g., minimizing separation) have been discussed and may be all that the short-term patient requires. However, children who experience prolonged or repeated hospitalization are at greater risk for developmental delay or regression. The nurse who provides opportunities for the child to participate in developmentally appropriate activities further normalizes the child’s environment and helps reduce interference with the child’s ongoing development. (See Normalization, Chapter 22.)

Child life specialists are health care professionals with extensive knowledge of child growth and development and the special psychosocial needs of children who are hospitalized and their families (Box 26-5). They help prepare children for hospitalization, surgery, and procedures. Although all members of the health care team share these responsibilities, this is the primary role of the child life specialist. A collaborative effort between the nurse, child life specialist, and other members of the child’s health care team will help ensure the best possible hospital experience for the child and family (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000).

Using Play and Expressive Activities to Minimize Stress

![]() Play is one of the most important aspects of a child’s life and one of the most effective tools for managing stress. Because illness and hospitalization constitute crises in the child’s life and often involve overwhelming stresses, acting out fears and anxieties gives the child a means to cope with these stresses. Children who play are coping positively; children who cannot play are waiting, testing, holding back, or making some inner decisions about the setting.

Play is one of the most important aspects of a child’s life and one of the most effective tools for managing stress. Because illness and hospitalization constitute crises in the child’s life and often involve overwhelming stresses, acting out fears and anxieties gives the child a means to cope with these stresses. Children who play are coping positively; children who cannot play are waiting, testing, holding back, or making some inner decisions about the setting.

Play is essential to children’s mental, emotional, and social well-being. As with their developmental needs, the need for play does not stop when children are ill or when they enter the hospital. On the contrary, play in the hospital serves many functions (Box 26-6). Of all hospital facilities, no room probably does more to alleviate the stressors of hospitalization than the playroom. In this room children temporarily distance themselves from the fears of separation, loss of control, and bodily injury. They can work through their feelings in a nonthreatening, comfortable atmosphere and in the manner most natural for them. They also know that the boundaries of this room are safe from intrusive or painful procedures, strange faces, and probing questions. The playroom becomes a sanctuary of peace and safety in an otherwise frightening environment (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

Engaging in play activities puts children in charge, removing them for a time from the usual passive role of recipients of a constant stream of procedures and hospital routines. In the hospital environment most decisions are made for the child, but play and other expressive activities offer the child much-needed opportunities to make choices. Even if a child chooses not to participate in a particular activity, the nurse has offered the child a choice, perhaps one of but a few real choices the child has had that day.

Children who are ill and hospitalized typically have lower energy levels than healthy children. Therefore children may not appear enthusiastic about an activity even when they are enjoying the experience. Rather than assuming otherwise, the nurse can observe for subtle signs—such as a fleeting smile or intense concentration—or simply ask children if they are enjoying themselves.

Children in various age-groups require different types of play facilities. Infants and toddlers need maximum safety, whereas school-age children and adolescents benefit most from group activities. Providing space for special needs of children in each age-group can be difficult in institutions where space is limited, but innovative solutions can ensure practical answers. Structure playroom schedules to allow one age-group at a time; for example, adolescents can use the facility in the evening when younger children are asleep. Older children can also congregate in one patient’s room and listen to music, play games, or just talk. If the location of the session rotates each evening, older children can look forward to arranging or setting up for the activities.

Diversional Activities

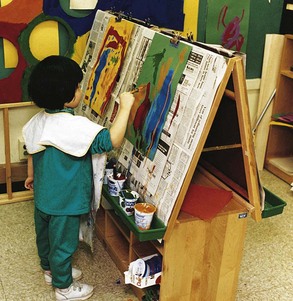

Almost any form of play can be used for diversion and recreation, but the activity should be selected on the basis of the child’s age, interests, and limitations (Fig. 26-9). Children do not necessarily need special direction for using play materials. All they require are the materials with which to work and adult approval and supervision to help keep their natural enthusiasm or expression of feelings from getting out of control. Young children enjoy a variety of small, colorful toys they can play with in bed or in their room or more elaborate play equipment, such as playhouses, sandboxes, rhythm instruments, and large boxes and blocks, that may be a part of the hospital playroom.

Fig. 26-9 Play materials for children in the hospital need to be appropriate for their age, interests, and limitations.