Perspectives of Pediatric Nursing

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Cancer in Children, Ch. 36

Case Management, Ch. 25

The Child and Trauma, Ch. 39

Classification of High-Risk Newborns, Ch. 10

Cultural and Religious Influences on Health Care, Ch. 2

Immunizations, Ch. 12

Injury Prevention: Infant, Ch. 12; Toddler, Ch. 14; Preschooler, Ch. 15; School-Age Child, Ch. 17; Adolescent, Ch. 19

Preschool and Kindergarten Experience, Ch. 15

Scope of the Problem (Chronic Illness or Disability), Ch. 22

Suicide, Ch. 21

Health Care for Children

The major goal for pediatric nursing is to improve the quality of health care for children and their families. There are 73 million children 0 to 18 years of age in the United States, comprising 25% of the population (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008). The health status of children in the United States has improved in a number of areas, including increased immunization rates for all children, decreased adolescent birth rate, and improved child health outcomes. Unfortunately millions of children and their families have no health insurance, which results in a lack of access to care and health promotion services. In addition, disparities in pediatric health care are related to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic factors (see Research Focus box). Patterns of child health are shaped by medical progress and societal trends (Dougherty, Meikle, Owens, et al, 2005; Wise, 2004, 2005). The Healthy People 2020 Leading Health Indicators (Box 1-1) provide a framework for identifying essential components for child health promotion programs designed to prevent future health problems in our nation’s children.

Health Promotion

Many leading causes of disease, disability, and death in children (i.e., prematurity, nutritional deficiencies, injuries, chronic lung disease, obesity, cardiovascular disease, depression, violence, substance abuse, and human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [HIV/AIDS]) can be significantly reduced or prevented in children and adolescents by addressing six categories of behavior (World Health Organization, 2007):

2. Behavior that results in injury and violence

4. Dietary and hygienic practices that cause disease

6. Sexual behavior that causes unintended pregnancy and disease

Child health promotion provides opportunities to reduce differences in current health status among members of different groups and ensure equal opportunities and resources to enable all children to achieve their fullest health potential.

Nutrition

Nutrition is an essential component for healthy growth and development. Human milk is the preferred form of nutrition for all infants. Breastfeeding provides the infant with micronutrients, immunologic properties, and several enzymes that enhance digestion and absorption of these nutrients. A recent resurgence in breastfeeding has occurred due to the education of mothers and fathers regarding its benefits and increased social support.

Children establish life-long eating habits during the first 3 years of life, and the nurse is instrumental in educating parents about the process of feeding and the importance of nutrition. Most eating preferences and attitudes related to food are established by family influences and culture. During adolescence, parental influence diminishes and the adolescent makes food choices related to peer acceptability and sociability. Occasionally these choices are detrimental to adolescents with chronic illnesses like diabetes, obesity, chronic lung disease, hypertension, cardiovascular risk factors, and renal disease.

Families that struggle with lower incomes, homelessness, and migrant status generally lack the resources to provide their children with adequate food intake, nutritious foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables, and appropriate protein intake. The result is nutritional deficiencies with subsequent growth and developmental delays, depression, and behavior problems.

Dental Care

Dental caries is the single most common chronic disease of childhood (Cheng, Han, and Gansky, 2008; Heuer, 2007). Nearly one in five children between the ages of 2 and 4 years has visible cavities (Kagihara, Niederhauser, and Stark, 2009). The most common form of early dental disease is early childhood caries, which may begin before the first birthday and progress to pain and infection within the first 2 years of life (Edelstein, 2005). Preschoolers of low-income families are twice as likely to develop tooth decay and only half as likely to visit the dentist as other children. Early childhood caries is a preventable disease, and nurses play an essential role in educating children and parents about practicing dental hygiene beginning with the first tooth eruption; drinking fluoridated water, including bottled water; and instituting early dental preventive care.

Immunizations

The two public health interventions that have had the greatest impact on world health are clean drinking water and childhood vaccination programs. Immunization rates differ depending on children’s race and ethnicity, family income, the state in which they live, types of vaccinations, and their age (whether adolescent or younger children) (Dougherty, Meikle, Owens, et al, 2005). The nurse should review individual immunization records at every clinic visit, avoid missing opportunities to vaccinate, and encourage parents to keep immunizations current (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009). Nurses are responsible for keeping up with changes in immunization schedules, recommendations, and research related to childhood vaccines.

Childhood Health Problems

Changes in modern society, including advancing medical knowledge and technology, the proliferation of information systems, economically trouble times, and various changes and disruptive influences on the family, are leading to significant medical problems that affect the health of children (Lichter, 2005). Recent concern has focused on groups of children who are at highest risk, such as children born prematurely or with very low birth weight (VLBW) or low birth weight (LBW), children attending child care centers, children who live in poverty or are homeless, children of immigrant families, and children with chronic medical and psychiatric illness and disabilities. In addition, these children and their families face multiple barriers to adequate health, dental, and psychiatric care. The new morbidity, also known as pediatric social illness, refers to the behavior, social, and educational problems that children face. Problems that can negatively impact a child’s development include poverty, violence, aggression, noncompliance, school failure, and adjustment to parental separation and divorce. In addition, mental health issues cause challenges in childhood and adolescence. One out of five adolescents has a mental health problem, and 1 out of 10 has a serious emotional problem that affects daily functioning (Coury, 2006).

Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes

Childhood obesity is the most common nutritional problem among American children, is increasing in epidemic proportions, and is associated with type 2 diabetes (Matyka, 2008; Cali and Caprio, 2008). Obesity in children and adolescents is defined as a body mass index at or greater than the 95th percentile for youth of the same age and gender (Schwartz and Chadha, 2008). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported that the prevalence of overweight children doubled and the prevalence of overweight adolescents tripled between 1980 and 2000 (American Dietetic Association, 2008).

Advancements in entertainment and technology such as television, computers, and video games have contributed to the growing childhood obesity problem in the United States. Approximately 63% of 8- to 18-years-olds have a television in their bedrooms and watch it an average of 4 hours a day (Robinson and Sargent, 2005). Minority populations, especially African-American and Hispanic children from low-income families, watch more than 4 hours of television daily, exacerbating the effects of sedentary activity and intake of high-caloric, fatty foods (Fitzgibbon and Stolley, 2004). Lack of physical activity related to limited resources, unsafe environments, and inconvenient play and exercise facilities, combined with easy access to television and video games, increases the incidence of obesity among low-income, minority children. Overweight youth, especially children of Hispanic, African-American, and Native American descent, have increased risk for developing hypercholesterolemia, insulin resistance, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease (Schwartz and Chadha, 2008; Matyka, 2008) (Fig. 1-1). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2009) suggests that nurses focus on prevention strategies to reduce the incidence of overweight children from the current 20% in all ethnic groups, to less than 6%.

Childhood Injuries

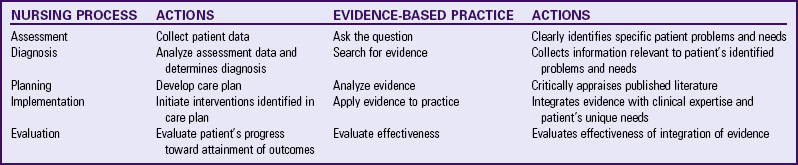

Injuries are the most common cause of death and disability to children in the United States (Schnitzer, 2006) (Table 1-1). Motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) continue to be the most common cause of death in children older than 1 year of age. Other unintentional injuries (head injuries, drowning, burns, and firearm accidents) take the lives of children every day. Many childhood injuries and fatalities could be prevented by implementing programs of accident prevention and health promotion.

TABLE 1-1

NUMBER OF UNINTENTIONAL INjURY DEATHS FOR LEADING CAUSES AMONG CHILDREN 14 YEARS AND YOUNGER

From Safe Kids USA: Injury trends fact sheet, Washington, DC, 2009, Safe Kids Worldwide, available at www.safekids.org/our-work/research/fact-sheets/injury-trends-fact-sheet.html (accessed June 21, 2010).

The type of injury and the circumstances surrounding it are closely related to normal growth and development (Box 1-2). As children develop, their innate curiosity compels them to investigate the environment and to mimic the behavior of others. This is essential to acquire competency as an adult, but can also predispose children to numerous hazards.

The child’s developmental stage partially determines the types of injuries that are most likely to occur at a specific age and helps provide clues to preventive measures. For example, small infants are helpless in any environment. When they begin to roll over or propel themselves, they can fall from unprotected surfaces. The crawling infant, who has a natural tendency to place objects in the mouth, is at risk for aspiration or poisoning. The mobile toddler, with the instinct to explore and investigate and the ability to run and climb, may experience falls, burns, and collisions with objects. As children grow older, their absorption with play makes them oblivious to environmental hazards such as street traffic or water. The need to conform and gain acceptance compels older children and adolescents to accept challenges and dares. Although the rate of injuries is high in children less than 9 years of age, most fatal injuries occur in later childhood and adolescence.

The pattern of deaths caused by unintentional injuries, especially from MVAs, drowning, and burns, is remarkably consistent in most Western societies. The leading causes of death from injuries and their trends are presented in Table 1-1. The majority of deaths from injuries occur in boys. It is important to note that accidents continue to account for more than three times as many teen deaths as any other cause (Annie E Casey Foundation, 2009). Fortunately, prevention strategies such as the use of car restraints, bicycle helmets, and smoke detectors have significantly decreased fatalities for children. Nevertheless, the overwhelming causes of death in children are MVAs, including occupant, pedestrian, bicycle, and motorcycle deaths; these account for more than half of all injury deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). Children under 1 year of age have the highest rate of death from MVAs, primarily from a failure to properly use car restraints (Fig. 1-2).

Fig. 1-2 Motor vehicle injuries are the leading cause of death in children older than 1 year of age. The majority of fatalities involve occupants who are unrestrained.

Pedestrian accidents involving children account for significant numbers of motor vehicle–related deaths. Most of these accidents occur at midblock, at intersections, in driveways, and in parking lots. Driveway injuries typically involve small children and large vehicles backing up.

Bicycle-associated injuries also cause a number childhood deaths. Children ages 5 to 9 years are at greatest risk of bicycling fatalities. The majority of bicycling deaths are from head injuries. Helmets reduce the risk of head injury by 85%, but few children wear helmets (National Safety Council, 2000). Community-wide bicycle helmet campaigns and mandatory-use laws have resulted in significant increases in helmet use. Still, issues such as stylishness, comfort, and social acceptability remain important factors in noncompliance. Nurses can educate children and families about pedestrian and bicycle safety. In particular, school nurses can promote helmet wearing and encourage peer leaders to act as role models.

Drowning and burns are among the top three leading causes of deaths for males and females throughout childhood (Fig. 1-3). In addition, improper use of firearms is a major cause of death among males (Fig. 1-4). During infancy, more boys die from aspiration or suffocation than do girls (Fig. 1-5). Approximately 70% of all unintentional poisonings are reported in children under 2 years of age (Bronstein, Spyker, Cantilena, et al, 2008; Franklin and Rodgers, 2008) (Fig. 1-6). By ages 4 to 5 years, unintentional poisonings are uncommon. Intentional poisoning, associated with drug and alcohol abuse and suicide attempt, is the second leading cause of death in adolescent females and third leading cause in adolescent males.

Fig. 1-3 A, Drowning is one of the leading causes of death. Children left unattended are unsafe even in shallow water. B, Burns are among the top three leading causes of death from injury in children ages 1 to 14 years.

Violence

Each day, 10 children in the United States are murdered by gunfire, equivalent to approximately one child every  hours (Groves, 2005). Strikingly higher homicide rates are found among minority populations, especially African-American children. The causes of violence against children and self-inflicted violence are not fully understood. Violence seems to permeate American households through television programs, commercials, video games, and movies, all of which tend to desensitize the child toward violence. Violence also permeates the schools with the availability of guns, illicit drugs, and gangs. The problem of child homicide is extremely complex and involves numerous social, economic, and other influences. Prevention lies in better understanding of the social and psychologic factors that lead to the high rates of homicide and suicide. Nurses need to be especially aware of young people who harm animals or start fires, are depressed, are repeatedly in trouble with the criminal justice system, or are associated with groups known to be violent. Prevention requires early identification and rapid therapeutic intervention by qualified professionals.

hours (Groves, 2005). Strikingly higher homicide rates are found among minority populations, especially African-American children. The causes of violence against children and self-inflicted violence are not fully understood. Violence seems to permeate American households through television programs, commercials, video games, and movies, all of which tend to desensitize the child toward violence. Violence also permeates the schools with the availability of guns, illicit drugs, and gangs. The problem of child homicide is extremely complex and involves numerous social, economic, and other influences. Prevention lies in better understanding of the social and psychologic factors that lead to the high rates of homicide and suicide. Nurses need to be especially aware of young people who harm animals or start fires, are depressed, are repeatedly in trouble with the criminal justice system, or are associated with groups known to be violent. Prevention requires early identification and rapid therapeutic intervention by qualified professionals.

Pediatric nurses can assess children and adolescents for risk factors related to violence. Families that own firearms must be educated about their safe use and storage. The presence of a gun in a household increases the risk of suicide by about fivefold and the risk of homicide by about threefold. Technologic changes such as childproof safety devices and loading indicators could improve the safety of firearms (see Community Focus box).

Substance Abuse

Risk-taking behaviors, particularly in males, tend to begin in the first decade of life and continue into adolescence with drinking alcohol while driving, speeding, carrying a weapon, or using illicit drugs. Adolescent trends in cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and illicit drug abuse have declined since 2002. Approximately 9.8% of youth reported cigarette smoking, 15.9% reported alcohol use, and 9.5% reported illicit drug abuse within the past month (National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2008). The slight decline in American youth’s illicit drug use is attributed to education regarding the adverse effects of illicit drugs, parental disapproval, decreased availability of drugs, and consistent participation in church and organized activities such as scouts and sports.

Mental Health Problems

Mental health problems affect one out of five school-age children in the United States. Children and adolescents with mental health problems are more likely to drop out of school than those with other disabilities (Kelleher, 2005). One of the most common mental health problems is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Kelleher, 2005). ADHD is characterized by inattentiveness, impulsivity, and at times hyperactivity, and it may occur in children as early as 3 years of age (Medd, 2003). ADHD affects every aspect of the child’s life, but is most obvious in the classroom. Medication, counseling, classroom interventions, behavior management strategies, and family education and counseling are all appropriate strategies to help children with mental health problems succeed.

Suicide is defined as a self-chosen death and is the third leading cause of death in children ages 10 to 19 (Doucette, 2005). The American Association of Suicidology (2009) estimates that there are 11.5 youth (15 to 24 years of age) suicides ever day. Suicide is preventable. Nurses should be alert to the symptoms of mental illness and potential suicidal ideation and be aware of potential resources for high-quality integrated mental health services (Coury, 2006).

Mortality

Mortality statistics describe the incidence or number of individuals who have died over a specific period. They are usually presented as rates per 100,000. Mortality rates are calculated from a sample of death certificates. In the United States the National Center for Health Statistics, under the Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, is responsible for the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data on the health of the American people (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2007).

The tabulation of race for live births (the denominator of infant mortality rates) has changed from race of child to race of mother. Formerly, for a child of mixed parentage in which one parent was Caucasian, the child was assigned the race of the other parent. In general, this change in assignment of race from child to mother has resulted in more Caucasian births and fewer non-Caucasian births. However, infant deaths are recorded by the decedent’s race, resulting in a lower infant mortality rate for Caucasians than non-Caucasians. As a result of these changes in the early 1990s, figures for births, deaths, and infant mortality rates by race are not comparable to statistics reported before these changes were made.

Infant Mortality

The infant mortality rate is the number of deaths during the first year of life per 1000 live births. It may be further divided into neonatal mortality (<28 days of life) and postneonatal mortality (28 days to 11 months). In the United States infant mortality has decreased dramatically. At the beginning of the twentieth century the rate was approximately 200 infant deaths per 1000 live births. In 2006 the infant mortality rate was 6.69 deaths per 1000 live births (Heron, Hoyert, Murphy, et al, 2009).

From a worldwide perspective, however, the United States lags behind other nations in reducing infant mortality. In 2006 the United States ranked last among 29 nations that have a population of at least 2.5 million and had infant mortality rates equal to or lower than that of the United States. Hong Kong, Japan, Sweden, and Finland have the three lowest rates, with the United States ranked last behind Poland and Malaysia (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010).

Birth weight is considered the major determinant of neonatal death in technologically developed countries. There is a relationship between LBW and infant morbidity and mortality (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010). The lower the birth weight, the higher the mortality. The relatively high incidence of LBW (<2500 g [5.5 lb]) in the United States is considered a key factor in its higher neonatal mortality rate when compared with other countries. Access to and the use of high-quality prenatal care is a promising preventive strategy to decrease early delivery and infant mortality. Other factors that increase the risk of infant mortality include African-American race, male gender, short or long gestation, maternal age, and lower level of maternal education (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010).

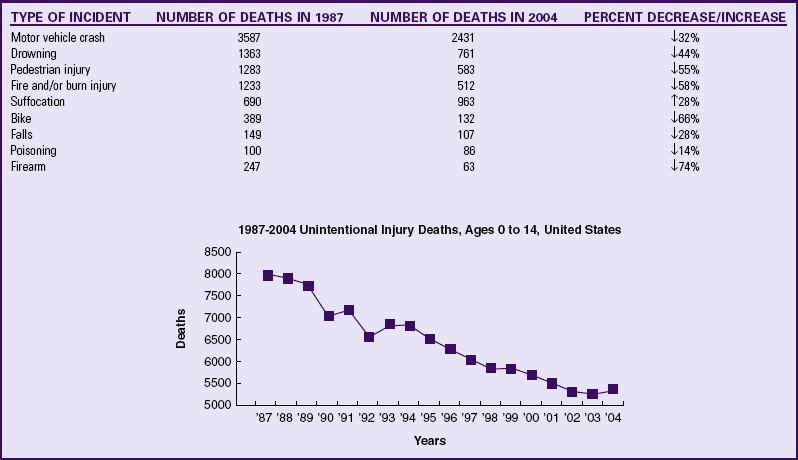

As Table 1-2 demonstrates, many of the leading causes of death during infancy continue to occur during the perinatal period. The first four causes—congenital anomalies, disorders relating to short gestation and unspecified LBW, sudden infant death syndrome, and newborn affected by maternal complications of pregnancy—accounted for about half of all deaths of infants under 1 year of age (Heron, Hoyert, Murphy, et al, 2009). LBW is a major indicator of infant health and a significant predictor of infant mortality (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010). Many birth defects are associated with LBW, and reducing the incidence of LBW will help prevent congenital anomalies. Infant mortality resulting from HIV infection decreased significantly during the 1990s. In 2003 HIV/AIDS accounted for less than 0.2% of all infant deaths (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010).

TABLE 1-2

INFANT MORTALITY RATE AND PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL DEATHS FOR 10 LEADING CAUSES OF INFANT DEATH IN 2007 (RATE PER 1000 LIVE BIRTHS)

Modified from Heron M, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, et al: Deaths: final data for 2006, Natl Vital Stat Rep 57(14):1-134, 2009.

When infant death rates are categorized according to race, a disturbing difference is seen. Infant mortality for Caucasians is considerably lower than for all other races in the United States, with African-Americans having twice the rate of Caucasians. Although the infant mortality of all racial groups increased slightly between 2001 and 2002, the gap has remained constant, with the infant mortality rate expressed as a ratio of African-American to Caucasian deaths being relatively unchanged for the past decade (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010). The LBW rate is also much higher for African-American infants than for any other group. One encouraging note is that the gap in mortality rates between Caucasian and non-Caucasian races other than African-Americans has narrowed in recent years. Infant mortality rates for Hispanics and Asian–Pacific Islanders have decreased dramatically during the past 2 decades (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010).

Childhood Mortality

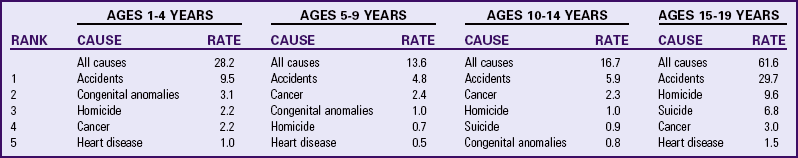

Death rates for children older than 1 year of age have always been lower than those for infants. Children ages 5 to 14 years have the lowest rate of death. However, a sharp rise occurs during later adolescence, primarily from injuries, homicide, and suicide (Table 1-3). In 2007 these causes were responsible for approximately 75% of deaths in teenagers and young adults 15 to 19 years old (Heron, Sutton, Xu, et al, 2010). The trend in racial differences that occurs in infant mortality is also apparent in childhood deaths for all ages and for both sexes. Caucasians have fewer deaths for all ages, and male deaths outnumber female deaths.

TABLE 1-3

FIVE LEADING CAUSES OF DEATH IN CHILDREN IN UNITED STATES: SELECTED AGE INTERVALS, 2007 (RATE PER 100,000 POPULATION)

Modified from Heron M, Sutton PD, Xu J, et al: Annual summary of vital statistics—2007, Pediatrics 125(1):13, 2010.

After 1 year of age, the cause of death changes dramatically, with unintentional injuries (accidents) being the leading cause from the youngest ages to the adolescent years. Violent deaths have been steadily increasing among young people ages 10 through 25 years, especially African-Americans and males. Homicide is the second leading cause of death in the 15- to 19-year age-group (see Table 1-3). Children 12 years of age and older tend to be killed by nonfamily members (acquaintances and gangs, typically of the same race) and most frequently by firearms. Suicide, a form of self-violence, is the third leading cause of death among children and adolescents 15 to 19 years of age.

Morbidity

Measurements of the prevalence of a specific illness in the population at a particular time are known as morbidity statistics. Morbidity statistics are generally presented as rates per 1000 population. Unlike mortality, morbidity is difficult to define and may denote acute illness, chronic disease, or disability. The source of data also influences the statistics. Common sources include reasons for visits to physicians; diagnoses for hospital admission; or household interviews such as the National Health Interview Survey, Child Health Supplement. Unlike death rates, which are updated annually, morbidity statistics are revised less frequently and do not necessarily represent the general population.

Childhood Morbidity

Acute illness is defined as an illness with symptoms severe enough to limit activity or require medical attention. Respiratory illness accounts for approximately 50% of all acute conditions, 11% are caused by infections and parasitic disease, and 15% are caused by injuries. The chief illness of childhood is the common cold.

The types of diseases that children contract during childhood vary according to age. For example, upper respiratory tract infections and diarrhea decrease in frequency with age, whereas other disorders, such as acne and headaches, increase. Children who have had a particular type of problem are more likely to have that problem again. Morbidity is not distributed randomly in children. Children from poor families do not fare as well on health indicators compared with children from nonpoor families (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2007). This finding suggests the need for heightened efforts to improve access to health care for low-income children.

Recent concern has focused on groups of children who have increased morbidity: homeless children, children living in poverty, LBW children, children with chronic illnesses, foreign-born adopted children, and children in daycare centers. A number of factors place these groups at risk for poor health. A major cause is barriers to health care, especially for the homeless, the poverty stricken, and those with chronic health problems. Other factors include improved survival of children with chronic health problems, particularly infants of VLBW.

Evolution of Child Health Care in the United States

Children in Colonial America were born into a world with many hazards to their health and survival. Epidemics were common. Control or treatment was unknown. Physicians were few, and only a small number had any formal training. Midwives were untrained, basing their practice on experience. Books providing information on child care and feeding were scarce and, when available, were useful only to a minority of parents who were literate.

Medical care by physicians was limited to wealthy families who lived in or could travel to more developed cities. Children who lived on farms were mainly cared for by another family member or by a competent neighbor. Traveling medicine men, with their various forms of quackery, were common. Children who were bought as slaves or born to slaves had only as much care as their owner was able or willing to provide. Native American children were treated according to the tradition of each tribe, which was often a mixture of medicine, magic, and religion. With the colonization of America, Native Americans were exposed to many new, often fatal diseases.

Statistics on childhood mortality during the Colonial period are largely unavailable. Epidemic diseases included smallpox, measles, mumps, chickenpox, influenza, diphtheria, yellow fever, cholera, and whooping cough. However, the disease that surpassed all others as a cause of childhood death was dysentery. Sometimes entire families succumbed to this illness. Other diseases that contributed to childhood illness were the “slow epidemics” of tuberculosis, nutritional diseases, and injuries.

Although scientific knowledge was accumulating, especially from work done in Europe, there were no organized efforts in the United States to apply that knowledge to the care of the sick. It was not until the Industrial Revolution was well under way in the nineteenth century that the consequences of childhood illness and injury and the effects of child labor, poverty, and neglect became widely recognized. The end of the nineteenth century is often regarded as the dark ages of pediatrics, and the first half of the twentieth century is regarded as the dawn of improved health care for children.

The study of pediatrics began in the late 1800s, particularly under the influence of a Prussian-born physician, Abraham Jacobi (1830-1919), who is referred to as the Father of Pediatrics. With several other physicians he broke new ground in the scientific and clinical investigation of childhood diseases. One outstanding achievement was the establishment of “milk stations,” where mothers could bring sick children for treatment and learn the importance of pure milk and its proper preparation.

The crusade for pure milk helped bring the dairy industry under legal control and led to the establishment of infant welfare stations. The remarkable decline in infant mortality since 1900 has been achieved through prevention and health-promoting measures such as improved sanitation and pasteurization of milk. Before these regulations existed, the unsanitary milk supply was a chief source of infantile diarrhea and tuberculosis. Cows were often kept in filthy stables and fed garbage and distillery wastes. Milk from cows that were fed distillery wastes was reported to make infants “tipsy.”

At the same time, increasing concern developed for the social welfare of children, especially those who were homeless or employed as factory laborers. The work of one reformer, Lillian Wald (1867-1940), had far-reaching effects on child health and nursing. She founded the Henry Street Settlement in New York City, which eventually provided nursing services; social work; and an organized program of social, cultural, and educational activities. Wald is regarded as the founder of public health or community nursing. She was instrumental in establishing the role of the first full-time school nurse, Lina Rogers. Soon other nurses were employed to teach parents and children about the prevention or treatment of minor skin conditions, malnutrition, and other impairments or illnesses identified in the school. An outgrowth of nursing involvement in school health was the development of pediatric courses and specialized clinical experience in schools of nursing.

As more causes of disease were identified, health care workers emphasized isolation and asepsis. In the early 1900s children with contagious diseases were isolated from adult patients. Parents were prohibited from visiting because they might transmit disease to and from the home. Even toys and personal articles of clothing were kept from the child. It was not until the 1940s and the famous work of Spitz and Robertson on institutionalized children that the effects of isolation and maternal deprivation were recognized. This research brought forth a surge of interest in the psychologic health of children and resulted in changes for hospitalized children, such as rooming-in, sibling visitations, child life (play) programs, prehospitalization preparation, parent education, and hospital schooling.

Influenced by social reformers such as Lillian Wald, national leaders took action to improve children’s living conditions. In 1909 President Theodore Roosevelt called the first White House Conference on Children, which focused on the care of dependent children and the deplorable working conditions of youngsters. As a result of this conference, the U.S. Children’s Bureau was established in 1912 and placed under the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (now the Department of Health and Human Services).

The establishment of the Children’s Bureau marked the beginning of a period of studies of economic and social factors related to infant mortality, maternal deaths, and maternal and infant care in rural areas, all of which created a stimulus for better standards of care for mothers and children. These studies led to the first Maternity and Infancy Act (Sheppard-Towner Act) in 1921, which provided grants to states to develop a Division of Maternal and Child Health (MCH) as a unit of the health department. This bill eventually lapsed because of opposition from those (especially the American Medical Association) who viewed it as a socialist movement. Nevertheless, the passage of the Maternity and Infancy Act was a turning point for the creation of the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1930.

With the passage of Title V of the Social Security Act (SSA) in 1935, a federal-state partnership was established under the administration of the Children’s Bureau. Title V included federal grants-in-aid to states (matched by state funds) for three types of work: MCH, Crippled Children’s Services (CCS), and child welfare services. The first programs provided by Title V were prenatal, postnatal, and child health clinics and training of personnel. The early emphasis of the CCS program was on orthopedic care. With the recognition that a child’s ability to function could be limited by a chronic illness, state CCS programs became involved with children who had developmental, behavioral, and educational problems and, more recently, with home care of children with complex medical conditions. This broadened concept was reflected in 1985 by the passage of legislation that changed the name of the CCS to the Program for Children with Special Health Needs (CSHN).

Other federal programs that have had a major impact on maternal and child health include:

Medicaid—In 1965 Medicaid was created under Title XIX of the SSA to reduce financial barriers to health care for the poor. It is the largest maternal-child health program. A major project under Medicaid is the Child Health Assessment Program (CHAP), which provides services for a large number of pregnant women and children. Not all poor children are eligible for Medicaid; financial eligibility varies considerably from state to state.

Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)—In 1974 the WIC Special Supplemental Food Program was started. This program provides nutritious food and nutrition education to low-income, pregnant, postpartum, and lactating women and to infants and children up to age 5 years. Other nutrition programs include Food Stamps, National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, and Child Care Food Program. The Child Care Food Program provides financial assistance for nutritious meals to children in daycare centers, family and group daycare homes, and Head Start centers.

Education for All Handicapped Children Act (P.L. 94-142)—In 1975 P.L. 94-142 was passed to provide free, appropriate public education to all handicapped children from ages 3 to 21 years and to provide for supportive services (such as speech and counseling) that ensure the benefit of special education.

Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of 1986 (P.L. 99-457)—In 1986 P.L. 99-457 was passed to allow for the provision of federal funding to states to develop and implement a statewide, comprehensive, coordinated, and multidisciplinary program of early intervention services for handicapped infants and toddlers and their families.

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990—Passage of this act required states to extend Medicaid coverage to all children ages 6 to 18 years with family incomes below 133% of the poverty level.

Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA)—Signed into law in 1993, FMLA allows eligible employees to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave from their jobs every year to care for newborn or newly adopted children; to care for children, parents, or spouses who have serious health conditions; or to recover from their own serious health conditions. After the leave, the law entitles employees to return to their previous jobs or to equivalent jobs with the same pay, benefits, and other conditions.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)—The first federal privacy standards to protect patients’ medical records and other health information provided to health plans, doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers took effect on April 14, 2003. HIPAA, developed by the Department of Health and Human Services, sets new standards that provide patients with access to their medical records and more control over how their personal health information is used and disclosed. For further information, see the website www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa.

Despite the number of federal and state programs available to assist children and families, health care in the United States has serious barriers, including (1) financial barriers, such as not having insurance, having insurance that does not cover certain services, or being unable to pay for services; (2) system barriers, such as having to travel great distances for health care or state-to-state variations in Medicaid benefits; and (3) knowledge barriers, such as a lack of understanding about the need for or value of prenatal or child health supervision or a lack of awareness of the services that are available. The current thrust in health care is to improve children’s and families’ access to health care.

One of the major changes in health care delivery has been the establishment of a prospective payment system based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). The DRG categories define pretreatment (prospective) billing for almost all U.S. hospitals reimbursed by Medicaid. Because hospitals are financially responsible when Medicaid patients exceed the allotted admission stay, more patients are discharged early. This has created an immense need for home care and other community-based services. Health care cost containment remains a national priority, and some form of prospective payment affects almost everyone. Nurses need to be aware of changing trends in health care economics and be prepared to meet the challenges presented by managed care companies and health maintenance organizations (HMOs).

The Art of Pediatric Nursing

Nursing of infants, children, and adolescents is consistent with the definition of nursing as “the diagnosis and treatment of human responses to actual or potential health problems.” This definition incorporates the four essential features of contemporary nursing practice (American Nurses Association, 2003):

1. Attention to the full range of human experiences and responses to health and illness without restriction to a problem-focused orientation

2. Integration of objective data with knowledge gained from an understanding of the patient or group’s subjective experience

3. Application of scientific knowledge to the processes of diagnosis and treatment

4. Provision of a caring relationship that facilitates health and healing

Family-Centered Care

The philosophy of family-centered care recognizes the family as the constant in a child’s life. Service systems and personnel must support, respect, encourage, and enhance the family’s strength and competence by developing a partnership with parents (National Center for Cultural Competence, 2007). Nurses support families in their natural care-giving and decision-making roles by building on their unique strengths and acknowledging their expertise in caring for their child both within and outside the hospital setting (National Center for Cultural Competence, 2007). The nurse considers the needs of all family members in relation to the care of the child (Box 1-3). The philosophy acknowledges diversity among family structures and backgrounds; family goals, dreams, strategies, and actions; and family support, service, and information needs (Hooper, 2008).

Two basic concepts in family-centered care are enabling and empowerment. Professionals enable families by creating opportunities and means for all family members to display their current abilities and competencies and to acquire new ones to meet the needs of the child and family. Empowerment describes the interaction of professionals with families in such a way that families maintain or acquire a sense of control over their family lives and acknowledge positive changes that result from helping behaviors that foster their own strengths, abilities, and actions.

Although caring for the family is strongly emphasized throughout this text, it is highlighted in features such as Cultural Competence and Family-Centered Care boxes (see p. 16).

Atraumatic Care

Atraumatic care is the provision of therapeutic care in settings, by personnel, and through the use of interventions that eliminate or minimize the psychologic and physical distress experienced by children and their families in the health care system. Therapeutic care encompasses the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, or palliation of acute or chronic conditions. Setting refers to the place in which that care is given—the home, the hospital, or any other health care setting. Personnel includes anyone directly involved in providing therapeutic care. Interventions range from psychologic approaches, such as preparing children for procedures, to physical interventions, such as providing space for a parent to room in with a child. Psychologic distress may include anxiety, fear, anger, disappointment, sadness, shame, or guilt. Physical distress may range from sleeplessness and immobilization to disturbances from sensory stimuli such as pain, temperature extremes, loud noises, bright lights, or darkness. Thus atraumatic care is concerned with the where, who, why, and how of any procedure performed on a child for the purpose of preventing or minimizing psychologic and physical stress (Wong, 1989).

The overriding goal in providing atraumatic care is: first, do no harm. Three principles provide the framework for achieving this goal: (1) prevent or minimize the child’s separation from the family, (2) promote a sense of control, and (3) prevent or minimize bodily injury and pain. Examples of providing atraumatic care include fostering the parent-child relationship during hospitalization, preparing the child before any unfamiliar treatment or procedure, controlling pain, allowing the child privacy, providing play activities for expression of fear and aggression, providing choices to children, and respecting cultural differences.

Role of the Pediatric Nurse

The pediatric nurse is responsible for promoting the health and well-being of the child and family. Nursing functions vary according to regional job structures, individual education and experience, and personal career goals. Just as patients (children and their families) have unique backgrounds, each nurse brings an individual set of variables that affect the nurse-patient relationship. No matter where pediatric nurses practice, their primary concern is the welfare of the child and family.

Therapeutic Relationship

The establishment of a therapeutic relationship is the essential foundation for providing high-quality nursing care. Pediatric nurses need to have meaningful relationships with children and their families and yet remain separate enough to distinguish their own feelings and needs. In a therapeutic relationship, caring, well-defined boundaries separate the nurse from the child and family. These boundaries are positive and professional and promote the family’s control over the child’s health care. These boundaries are essential for effective family advocacy (Jacobson, 2002). Both the nurse and the family are empowered and maintain open communication. In a nontherapeutic relationship these boundaries are blurred, and many of the nurse’s actions may serve personal needs, such as a need to feel wanted and involved, rather than the family’s needs.

Exploring whether relationships with patients are therapeutic or nontherapeutic helps nurses identify problem areas early in their interactions with children and families (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Although questions regarding the nurse’s involvement may label certain actions negative or positive, no one action makes a relationship therapeutic or nontherapeutic. For example, a nurse may spend additional time with the family but still recognize his or her own needs and maintain professional separateness. An important clue to nontherapeutic relationships is the staff’s concerns about their peer’s actions with the family.

Family Advocacy and Caring

Although nurses are responsible to themselves, the profession, and the institution of employment, their primary responsibility is to the consumer of nursing services: the child and family. The nurse must work with family members, identify their goals and needs, and plan interventions that best address the defined problems. As an advocate, the nurse assists the child and family in making informed choices and acting in the child’s best interest. Advocacy involves ensuring that families are aware of all available health services, adequately informed of treatments and procedures involved in the child’s care, and encouraged to change or support existing health care practices. The United Nations’ Declaration of the Rights of the Child (Box 1-4) provides guidelines for nursing practice to ensure that every child receives optimum care.

As nurses care for children and families, they must demonstrate caring, compassion, and empathy for others. Aspects of caring embody the concept of atraumatic care and the development of a therapeutic relationship with patients. Parents perceive caring as a sign of quality in nursing care, which is often focused on the nontechnical needs of the child and family. Parents describe “personable” care as actions by the nurse that include acknowledging the parent’s presence, listening, making the parent feel comfortable in the hospital environment, involving the parent and child in the nursing care, showing interest in and concern for their welfare, showing affection and sensitivity to the parent and child, communicating with them, and individualizing the nursing care. Parents perceive personable nursing care as being integral to establishing a positive relationship.

Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

Every nurse involved in caring for children must understand the importance of disease prevention and health promotion. A nursing care plan must include a thorough assessment of all aspects of child growth and development, including nutrition, immunizations, safety, dental care, socialization, discipline, and education. If problems are identified, the nurse intervenes directly or refers the family to other health care providers or agencies.

The best approach to prevention is education and anticipatory guidance. In this text each chapter on health promotion includes sections on anticipatory guidance. An appreciation of the hazards or conflicts of each developmental period enables the nurse to guide parents regarding childrearing practices aimed at preventing potential problems. One significant example is safety. Because each age-group is at risk for special types of injuries, preventive teaching can significantly reduce injuries, lowering permanent disability and mortality rates.

Prevention also involves less obvious aspects of caring for children. The nurse is responsible for providing care that promotes mental well-being (e.g., enlisting the help of a child life specialist during a painful procedure such as an immunization).

Health Teaching

Health teaching is inseparable from family advocacy and prevention. Health teaching may be the nurse’s direct goal, such as during parenting classes, or may be indirect, such as helping parents and children understand a diagnosis or medical treatment, encouraging children to ask questions about their bodies, referring families to health-related professional or lay groups, supplying patients with appropriate literature, and providing anticipatory guidance.

Health teaching is one area in which nurses often need preparation and practice with competent role models, since it involves transmitting information at the child’s and family’s level of understanding and desire for information. As an effective educator, the nurse focuses on providing the appropriate health teaching with generous feedback and evaluation to promote learning.

Support and Counseling

Attention to emotional needs requires support and, sometimes, counseling. The role of child advocate or health teacher is supportive by virtue of the individualized approach. The nurse can offer support by listening, touching, and being physically present. Touching and physical presence are most helpful with children because they facilitate nonverbal communication. Counseling involves a mutual exchange of ideas and opinions that provides the basis for mutual problem solving. It involves support, teaching, techniques to foster the expression of feelings or thoughts, and approaches to help the family cope with stress. Optimally, counseling not only helps resolve a crisis or problem but also enables the family to attain a higher level of functioning, greater self-esteem, and closer relationships. Although counseling is often the role of nurses in specialized areas, counseling techniques are discussed in various sections of this text to help students and nurses cope with immediate crises and refer families for additional professional assistance.

Coordination and Collaboration

The nurse, as a member of the health care team, collaborates and coordinates nursing care with the care activities of other professionals. A nurse working in isolation rarely serves the child’s best interests. The concept of holistic care can be realized through a unified, interdisciplinary approach by being aware of individual contributions and limitations and collaborating with other specialists to provide high-quality health services. Failure to recognize limitations can be nontherapeutic at best and destructive at worst. For example, the nurse who feels competent in counseling but who is really inadequate in this area may not only prevent the child from dealing with a crisis but also impede future success with a qualified professional.

Even nurses who practice in isolated geographic areas widely separated from other health professionals cannot be considered independent. Every nurse works interdependently with the child and family, collaborating on assessing needs and planning interventions so that the final care plan truly meets the child’s needs. Numerous disciplines often work together to formulate a comprehensive approach without consulting patients regarding their ideas or preferences. The nurse is in a vital position to include patients in their care, either directly or indirectly, by communicating their thoughts to the health care team.

Ethical Decision Making

Ethical dilemmas arise when competing moral considerations underlie various alternatives. Parents, nurses, physicians, and other health care team members may reach different but morally defensible decisions by assigning different weights to competing moral values. These competing moral values may include autonomy, the patient’s right to be self-governing; nonmaleficence, the obligation to minimize or prevent harm; beneficence, the obligation to promote the patient’s well-being; and justice, the concept of fairness. Nurses must determine the most beneficial or least harmful action within the framework of societal mores, professional practice standards, the law, institutional rules, the family’s value system and religious traditions, and the nurse’s personal values.

Nurses must prepare themselves systematically for collaborative ethical decision making. They can accomplish this through formal course work, continuing education, contemporary literature, and work to establish an environment conducive to ethical discourse. Moreover, nurses must be educated on the mechanisms for dispute resolution, case review by ethics committees, procedural safeguards, state statutes, and case law (Woods, 2005).

The nurse also uses the professional code of ethics for guidance and as a means for professional self-regulation. The Code of Ethics for Nurses by the American Nurses Association focuses on the nurse’s accountability and responsibility to the patient and emphasizes the nursing role as an independent professional, one that upholds its own legal liability.

Nurses may face ethical issues regarding patient care, such as the use of lifesaving measures for VLBW newborns or the terminally ill child’s right to refuse treatment. They may struggle with questions regarding truthfulness, balancing their rights and responsibilities in caring for children with AIDS, whistle-blowing, or allocating resources. Throughout the text such dilemmas are addressed in boxes titled Ethical Decision Making. Conflicting ethical arguments are presented to help nurses clarify their value judgments when confronted with sensitive issues.

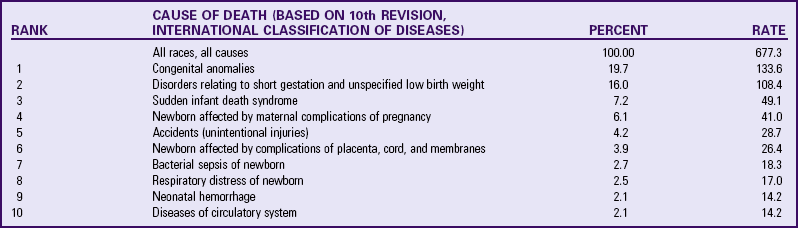

Research and Evidence-Based Practice

Nurses should contribute to research because they are the individuals observing human responses to health and illness. The current emphasis on measurable outcomes to determine the efficacy of interventions (often in relation to the cost) demands that nurses know whether clinical interventions result in positive outcomes for their patients. This demand has influenced the current trend toward evidence-based practice (EBP), which implies questioning why something is effective and whether a better approach exists. The concept of EBP also involves analyzing and translating published clinical research into the everyday practice of nursing. When nurses base their clinical practice on science and research and document their clinical outcomes, they will be able to validate their contributions to health, wellness, and cure, not only to their patients, third-party payers, and institutions but also to the nursing profession. Evaluation is essential to the nursing process, and research is one of the best ways to accomplish this.

EBP is the collection, interpretation, and integration of valid, important, and applicable patient-reported, nurse-observed, and research-derived information. Evidence-based nursing practice combines knowledge with clinical experience and intuition. It provides a rational approach to decision making that facilitates best practice (Scott and McSherry, 2009; van Achterberg, Schoonhoven, and Grol, 2008). EBP is an important tool that complements the nursing process by using critical thinking skills to make decisions based on existing knowledge. The traditional nursing process approach to patient care can be used to conceptualize the essential components of EBP nursing (Table 1-4). During the assessment and diagnostic phases of the nursing process, the nurse establishes important clinical questions and completes a critical review of existing knowledge. EBP also begins with identification of the problem. The nurse asks clinical questions in a concise, organized way that allows for clear answers. Once the specific questions are identified, extensive searching for the best information to answer the question begins. The nurse evaluates clinically relevant research, analyzes findings from the history and physical examinations, and reviews the specific pathophysiology of the defined problem. The third step in the nursing process is to develop a care plan. In evidence-based nursing practice, the care plan is established on completion of a critical appraisal of what is known and not known about the defined problem. Next, in the traditional nursing process, the nurse implements the care plan. By integrating evidence with clinical expertise, the nurse focuses care on the patient’s unique needs. A template for organizing the evidence is found in Box 1-5. The final step in EBP is consistent with the final phase of the nursing process: to evaluate the effectiveness of the care plan.

Searching for evidence in this modern era of technology can be overwhelming. For nurses to implement EBP, they must have access to appropriate, recent resources such as online search engines and journals. In many institutions computer terminals are available on patient care units, with the Internet and online journals easily accessible. Another important resource for the implementation of EBP is time. The nursing shortage and ongoing changes in many institutions have compounded the issue of nursing time allocation for patient care, education, and training. In some institutions nurses are given paid time away from performing patient care to participate in activities that promote EBP. This requires an organizational environment that values EBP and its potential impact on patient care. As knowledge is generated regarding the significant impact of EBP on patient care outcomes, it is hoped that the organizational culture will change to support the staff nurse’s participation in EBP. As the amount of available evidence increases, so does our need to critically evaluate the evidence.

Throughout this book, EBP boxes summarize the existing evidence that promotes excellence in clinical care. The GRADE criteria are used to evaluate the quality of research articles used to develop practice guidelines (Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, et al, 2008). Table 1-5 defines how the nurse rates the quality of the evidence using the GRADE criteria and establishes a strong versus weak recommendation. Each EBP box rates the quality of existing evidence and the strength of the recommendation for practice change.

TABLE 1-5

THE GRADE CRITERIA TO EVALUATE THE QUALITY OF THE EVIDENCE

| QUALITY | TYPE OF EVIDENCE |

| High | Consistent evidence from well-performed randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or exceptionally strong evidence from unbiased observational studies |

| Moderate | Evidence from RCTs with important limitations (inconsistent results, methodologic flaws, indirect evidence, or imprecise results) or unusually strong evidence from unbiased observational studies |

| Low | Evidence for at least one critical outcome from observational studies, from RCTs with serious flaws, or from indirect evidence |

| Very Low | Evidence for at least one of the critical outcomes from unsystematic clinical observations or very indirect evidence |

| QUALITY | RECOMMENDATION |

| Strong | Desirable effects clearly outweigh undesirable effects, or vice versa |

| Weak | Desirable effects closely balanced with undesirable effects |

Adapted from Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Visit GE, et al: GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations, BMJ 336:924-926, 2008.

Critical Thinking and the Process of Providing Nursing Care to Children and Families

A systematic thought process is essential to a profession. It assists the professional in meeting the patient’s needs. Critical thinking is purposeful, goal-directed thinking that assists individuals in making judgments based on evidence rather than guesswork (Walsh and Seldomridge, 2006; Alfaro-LeFevre, 2005). It is based on the scientific method of inquiry, which is also the basis for the nursing process. Critical thinking and the nursing process are considered crucial to professional nursing in that they constitute a holistic approach to problem solving.

Critical thinking is a complex developmental process based on rational and deliberate thought. Becoming a critical thinker provides a common denominator for knowledge that exemplifies disciplined and self-directed thinking. The knowledge is acquired, assessed, and organized by thinking through the clinical situation and developing an outcome focused on optimum patient care. Critical thinking transforms the way in which individuals view themselves, understand the world, and make decisions. In recognition of the importance of this skill, Critical Thinking Exercises are included in this text. These exercises present a nursing practice situation that challenges the student to use the skills of critical thinking to come to the best conclusion. A series of questions lead the student to explore the evidence, assumptions underlying the problem, nursing priorities, and support for nursing interventions that allow the nurse to make a rational and deliberate response. These thinking exercises are designed to enhance nursing performance in clinical judgment.

Nursing Process

The nursing process is a method of problem identification and problem solving that describes what the nurse actually does (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2005). The five-step nursing process model is assessment, diagnosis (problem identification), planning (with outcome development), implementation, and evaluation. The second step of the nursing process, nursing diagnosis, involves the naming the child’s or family’s problem in standardized nursing language. In the American Nurses Association (2003) Standards of Practice, the nursing diagnosis phase of the nursing process is separated into two steps: nursing diagnosis and outcome identification.

Assessment

Assessment is a continuous process that operates at all phases of problem solving and is the foundation for decision making. Assessment involves multiple nursing skills and consists of the purposeful collection, classification, and analysis of data from a variety of sources. To provide an accurate and comprehensive assessment, the nurse must consider information about the patient’s biophysical, psychologic, sociocultural, and spiritual background.

Nursing Diagnosis

The second stage of the nursing process is problem identification and nursing diagnosis. At this point the nurse must interpret and make decisions about the data gathered. The nurse organizes or clusters these data into categories to identify significant areas and makes one of the following decisions:

• No dysfunctional health problems are evident; no interventions are indicated.

• Risk for dysfunctional health problems exists; interventions are needed for health promotion.

• Actual dysfunctional health problems are evident; interventions are needed for health promotion.

The nursing diagnosis is the naming of the cue clusters that are obtained during the assessment phase. According to NANDA International (formerly the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association), the currently accepted definition of the term nursing diagnosis is that it is a clinical judgment about individual, family, or community responses to actual and potential health problems and life processes. Nursing diagnoses provide the basis for selecting nursing interventions to achieve outcomes for which the nurse is accountable (Johnson, Bulechek, Dochterman, et al, 2001). The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) consists of a standardized list of more than 400 examples of care provided by nurses in clinical practice. The Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) is a comprehensive, standardized system of patient outcomes that can be used to evaluate the results of specific nursing interventions. Examples of NIC and NOC concepts are listed in each Nursing Care Plan in this text to provide an understanding of the standardized language and how it relates to the individualized plan.

Not all children have actual health problems; some have a potential health problem, which is a risk state that requires nursing intervention to prevent the development of an actual problem. Potential health problems may be indicated by risk factors, or signs, that predispose a child and family to a dysfunctional health pattern and are limited to individuals at greater risk than the population as a whole. Nursing intervention are directed toward reducing risk factors. To differentiate actual from potential health problems, the word risk is included in the nursing diagnosis statement (e.g., Risk for Infection).

Signs and symptoms refer to a cluster of cues and defining characteristics that are derived from patient assessment and indicate actual health problems. When a defining characteristic is essential for the diagnosis to be made, it is considered critical. These critical defining characteristics help differentiate between diagnostic categories. For example, in deciding between the diagnostic categories related to family function and coping, the nurse uses defining characteristics to choose the most appropriate nursing diagnosis (see Family-Centered Care box).

Planning

After identifying the nursing diagnoses, the nurse develops a care plan and establishes outcomes or goals. The outcome is the projected or expected change in a patient’s health status, clinical condition, or behavior that occurs after nursing interventions have been instituted. The ultimate goal of nursing care is to convert the nursing diagnoses into a desired health state. The care plan must be established before specific nursing interventions are developed and implemented.

Implementation

The implementation phase begins when the nurse puts the selected intervention into action and accumulates feedback data regarding its effects (or the patient’s response to the intervention). The feedback returns in the form of observation and communication and provides a database on which to evaluate the outcome of the nursing intervention. It is imperative that continual assessment of the patient’s status occur throughout all phases of the nursing process, thus making the process a dynamic rather than static problem-solving method. Throughout the implementation stage, the main concerns are the patient’s physical safety and psychologic comfort in terms of atraumatic care.

Evaluation

Evaluation is the last step in the decision-making process. The nurse gathers, sorts, and analyzes data to determine whether (1) the established outcome has been met, (2) the nursing interventions were appropriate, (3) the plan requires modification, or (4) other alternatives should be considered. The evaluation phase either completes the nursing process (outcome is met) or serves as the basis for selecting alternative interventions to solve the specific problem.

With the current focus on patient outcomes in health care, the patient’s care is evaluated not only at discharge but thereafter as well to ensure that the outcomes are met and there is adequate care for resolving existing or potential health problems. One federal agency that has developed clinical guidelines is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.*

Documentation

Although documentation is not one of the five steps of the nursing process, it is essential for evaluation. The nurse can assess, diagnose and identify problems, plan, and implement without documentation; however, evaluation is best performed with written evidence of progress toward outcomes. The patient’s medical record should include evidence of those elements listed in the Nursing Care Guidelines box.

Quality Outcome Measures

Quality of care refers to the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge (Institute of Medicine, 2000). Since nurses are the principal caregivers within health care institutions, high-quality nursing outcomes are used as an indicator of the ability to provide excellence in patient care. Nurse-sensitive indicators are chosen by using specific evaluation criteria (Box 1-6). Specific examples of patient-centered outcome measures established by the National Quality Forum are found in Box 1-7. A comprehensive resource, the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses, is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.†

Quality outcome evaluation criteria establish a framework for measuring nursing care performance. In addition to using the National Quality Forum’s measurement evaluation criteria, nurses should evaluate each quality-nursing indicator to ensure it is an essential component of health care quality established by the Institute of Medicine (2000). These components include the following:

Throughout the chapters that focus on serious health problems, we have developed examples of quality outcome measures for specific diseases that reflect patient-centered outcomes. Quality outcome measures promote interdisciplinary teamwork, and the boxes throughout this book exemplify measures of effective collaboration to improve care. Quality Patient Outcomes boxes throughout this book are developed to assist health care professionals in identifying appropriate measures that evaluate the quality of patient care.

Key Points

• Although the infant mortality rate in the United States has declined over the past few decades, the United States lags significantly behind most other major countries, such as Canada.

• LBW, which is closely related to early gestational age, is considered the leading cause of neonatal death in the United States.

• Injuries are the leading cause of death in children over age 1 year, with the majority being MVA injuries.

• Childhood morbidity encompasses acute illness, chronic disease, and disability.

• Eighty percent of childhood illnesses are attributable to infections, with respiratory tract infections occurring two or three times more often than all other illnesses combined.

• The new morbidity refers to behavioral, social, and educational problems that can significantly alter a child’s health.

• Developmental stage and environment are important determinants of the prevalence of injuries at a given age and thus help to direct preventive measures.

• The philosophy of family-centered care recognizes that the family is the constant in a child’s life and that service systems and personnel must support, respect, and enhance the family’s strength and competence.

• Atraumatic care is the provision of therapeutic care in settings, by personnel, and through the use of interventions that eliminate or minimize the psychologic and physical distress experienced by children and their families in the health care system.

• The pediatric nurse’s roles include a therapeutic relationship, family advocacy, disease prevention and health promotion, health teaching, support and counseling, coordination and collaboration, ethical decision making, and research.

• EBP is the collection, interpretation, and integration of valid, important, and applicable patient-reported, nurse-observed, and research-derived information.

• The process of nursing children and families includes accurate and comprehensive assessment, analysis and synthesis of assessment data to arrive at a nursing diagnosis, planning of care, implementation of the plan, and evaluation of interventions.

• Since nurses are the principal caregivers within health care institutions, quality outcomes are used as a measure of the ability to provide excellence in patient care.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare disparities report. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008.

Alfaro-LeFevre, R. Applying nursing process: a tool for critical thinking, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 2005.

American Academy of Pediatrics. The national children’s study. available at www.aap.org/family/natlchstudy.htm, 2008. [accessed January 2, 2009].

American Association of Suicidology. Youth suicide fact sheet. available at www.suicidology.org, 2009. [accessed December 2, 2009].

American Dietetic Association. Position of the American Dietetic Association: nutrition guidance for healthy children ages 2 to 11 years. J Am Dietetic Assoc. 2008;108(6):1038–1047.

American Nurses Association. Nursing: scope and standards of practice. Washington, DC: The Association; 2003.

Annie, E, Casey Foundation. Kids count data book: state profiles of child well-being. Baltimore: The Foundation; 2009.

Bronstein, AC, Spyker, DA, Cantilena, LR, et al. 2007 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ national poison data system: 25th annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2008;46(1):927–1057.

Cali, AMG, Caprio, S. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in youth: an emerging epidemic disease? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2008;15:123–127.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC injury fact book. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2006.

Cheng, NF, Han, PZ, Gansky, SA. Methods and software for estimating health disparities: the case of children’s oral health. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(8):906–914.

Coury, DL. Over the rainbow: advancing child health in the new millennium. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(3):134–137.

Doucette, A. Youth suicide. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Dougherty, D, Meikle, SF, Owens, P, et al. Children’s health care in the First National Healthcare Quality Report and National Healthcare Disparities Report. Med Care. 2005;43(3 Suppl):I58–I63.

Edelstein, BL. Tooth decay: the best of times, the worst of times. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s children: key national indicators of well-being. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2007.

Fitzgibbon, ML, Stolley, MR. Environmental changes may be needed for prevention of overweight in minority children. Pediatr Ann. 2004;33:45–49.

Franklin, RL, Rodgers, GB. Unintentional child poisoning treated in the United States hospital emergency departments: national estimates of incident cases, population-based poisoning rates, and product involvement. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1244–1251.

Groves, BM. Violence in the lives of children. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Guyatt, GH, Oxman, AD, Vist, GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926.

Heuer, S. Family-centered care. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2007;12(1):61–65.

Hooper, VD. Patient-family centered care: are we there yet? J Peri Anesthesia Nurs. 2008;23(6):440–442.

Heron, M, Hoyert, DL, Murphy, SL, et al. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;57(14):1–134.

Heron, M, Sutton, PD, Xu, J, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2007. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):4–15.

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm. Washington, DC: The Institute; 2000.

Jacobson, GA. Maintaining professional boundaries: preparing nursing students for the challenge. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41(6):279–281.

Johnson, M, Bulechek, G, Dochterman, J, et al. Nursing diagnosis, outcomes and interventions. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001.

Kagihara, LE, Niederhauser, VP, Stark, M. Assessment, management, and prevention of early childhood caries. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2009;21(1):1–10.

Kelleher, K. Mental health. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Lichter, DT. Families: diversity and change. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Matyka, KA. Type 2 diabetes in childhood: epidemiological and clinical aspects. Br Med Bull. 2008;86:59–75.

Medd, SE. Children with ADHD need our advocacy. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17:102–104.

National Center for Cultural Competence. A guide for advancing family-centered and culturally and linguistically competent care. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development; 2007.

National Safety Council. Injury facts. Itasca, Ill: The Council; 2000.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Trends in substance use, dependence or abuse, and treatment among adolescents: 2002-2007. Rockville, Md: Office of Applied Studies; December 4, 2008.

Robinson, TN, Sargent, JD. Children and media. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Schnitzer, PG. Prevention of unintentional childhood injuries. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(11):1864–1869.

Schwartz, MS, Chadha, A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in childhood: obesity and insulin resistance. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2008;108:518–524.

Scott, K, McSherry, R. Evidence-based nursing: clarifying the concepts for nurses in practice. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(8):1085–1095.

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020: the road ahead. available at www.healthypeople.gov/hp2020/default.asp, 2009. [accessed January 19, 2009].

van Achterberg, T, Schoonhoven, L, Grol, R. Nursing implementation science: how evidence-based nursing requires evidence-based implementation. J Nurs Scholar. 2008;40(4):302–310.