Social, Cultural, and Religious Influences on Child Health Promotion

http://evolve.elsevier.com/wong/ncic

Communicating with Families Through an Interpreter, Ch. 6

Family Influences on Child Health Promotion, Ch. 3

Lactose Intolerance, Ch. 13

Nutritional Assessment, Ch. 6

Sickle Cell Anemia, Ch. 35

Skin, Ch. 6

Toddler, Ch. 14; Preschooler, Ch. 15; School-Age Child, Ch. 17; Adolescent, Ch. 19

Vegetarian Diets, Ch. 13

Culture

Promoting the health of pediatric patients requires a nurse to understand social, cultural, and religious influences on children. This in turn depends on a purposeful awareness of the child’s sociocultural context. A holistic view of care was first described by Madeleine Leininger, the recognized founder of transcultural nursing, in her culture care diversity and universality theory (Leininger, 2001). The theory provides an intellectual framework and a research methodology for providing culturally congruent patient care. As the ethnic, racial, and cultural diversity in the U.S. population increases, it is imperative that nurses become competent in transcultural nursing (Munoz and Luckmann, 2005). They must remain aware that every family, child, and health care provider comes to a clinical encounter with a cultural lens through which they see and interpret the world.

Transcultural nursing care is important considering the ever-changing population. The demographic profile of the United States 2000 census includes 69% non-Hispanic white, 13% Hispanic/Latino, 12% Black/African-American, and 4% Asian (US Census Bureau, 2001).

Nurses can become culturally competent by learning about and developing an understanding of cultures other than their own, being sensitive to the effects of culture on the nursing care of patients, and understanding how their own culture affects their ability to provide care to others (Dunn, 2002).

Culture is a rich context through which people view and respond to their world (see Cultural Competence box). It also provides the lens through which all facets of human behavior can be interpreted (Spector, 2009). Culture is composed of individuals who share a set of values, beliefs, practices (e.g., language, dress, diet, health care), social relationships, laws, politics, economics, and norms of behavior that are learned, integrative, social, and satisfying. Culture is an ingrained orientation to life that serves as a frame of reference for individual perception and judgment. Culture is, essentially, the way of life of a group of people that incorporates experiences of the past, influences thought and action in the present, and transmits these traditions to future group members. Families pass their culture on to children, and the children perceive the world through this cultural lens. Culture adapts to the ever-changing world as group members abandon, modify, or assume new patterns of living and behavior to meet the group’s needs.

Material overt, or manifest, culture refers to the observable components of a culture, such as material objects (dress, art, utensils, and other artifacts) and actions. Nonmaterial covert culture refers to those aspects that cannot be observed directly, such as ideas, beliefs, customs, and feelings. Related to the large culture are many subcultures, each with an identity of its own. Children are socialized into a particular subculture rather than into the culture as a whole. Subcultural influences, such as ethnicity and social class, are discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Cultures and subcultures contribute to the uniqueness of child members in such a subtle way and at such an early age that children grow up to think that their beliefs, attitudes, values, and practices are the “correct” or “normal” ones. By age 5 years, children can identify persons who belong to their own race or cultural background. During later primary years, children can identify those from different cultures (Trawick-Smith, 2006). A set of values learned in childhood is likely to characterize children’s attitudes and behavior for life, influencing their long-range goals and their short-range, impulsive inclinations. Thus every ongoing society socializes each succeeding generation to its cultural heritage.

The manner and sequence of the growth and development phenomenon are universal and fundamental features of all children; however, children’s varied behavioral responses to similar events are often determined by their culture. Culture plays a critical role in the parenting behaviors that facilitate children’s development (Melendez, 2005). Children acquire the skills, knowledge, beliefs, and values important to their own family and culture. Cultural backgrounds can influence the pace of acquisition of cognitive and motor skills as well as the child’s social and emotional development (Trawick-Smith, 2006).

Cultures may also differ in whether status in a group is based on age or on skill. Even children’s play and their types of games are culturally determined. In some cultures children play in groups composed of members of the same sex; in others they play in mixed-sex groups. In some cultures team games predominate; in others most play is limited to individual games.

Standards and norms vary from culture to culture and from location to location; a practice that is accepted in one area may meet with disapproval or create tension in another. The extent to which cultures tolerate divergence from the established norm also varies among cultures and subcultural groups. Although conforming to cultural norms provides a degree of security, it is a decided deterrent to change.

The Child and Family in North America

Context provides perspective for nursing care. The health and well-being of the child in the North American family is influenced by two distinct contexts: the context of family and the context of culture. Therefore understanding these layers of influence on pediatric health is integral to developing a family-centered and culturally competent nursing practice (Thibodeaux and Deatrick, 2007). America’s orientation toward homogenization—“the great melting pot”—is changing to an orientation of complex cultural diversity. Increased awareness of the growing proportion of ethnic minorities that make up the U.S. population, coupled with a new appreciation for ethnic diversity, has resulted in a renewed interest in cultural variation.

The frontier background of the American culture has contributed to the overall orientation to life and childrearing. Americans have always had a basic optimistic view of the world, a belief that things can be better and that the children can and will be better off than their parents. With this hopeful outlook, a general future orientation, and the possibility of upward social mobility, American culture typically encourages development of self-confidence and autonomy in children. Children are generally permitted a greater degree of freedom than in more tradition-oriented cultures.

Family life in North America is characterized by increasing geographic and economic mobility. Families are less reliant on tradition, are fragmented, and have limited opportunity to transmit and acquire the traditional and accepted customs of a culture. Consequently, young adults rely to a greater extent on the professed experts, peers, and the mass media for acquisition of acceptable patterns of behavior, including childrearing practices. Conflicting information can be a source of confusion and frustration as parents attempt to determine the comparatively stable, essential components of the culture and transmit these to their children.

Children in North America grow up with a number of adults who differ from one another but who all provide input as role models, teachers, and standards for behavior. Most children live in some form of nuclear family located in sharply differentiated neighborhoods determined by income and ethnic status within a highly technical, largely urban society. Class differences in childrearing persist, but they are becoming less divergent.

Early in life children in minority cultures become aware of their cultural context and the discriminatory attitudes of the majority culture toward their racial or ethnic group. The direct effects of discrimination are anger and low self-esteem, which manifest in a variety of behaviors. Attitudes are slowly changing in some groups and in some places. With a relatively recent emergence of racial and ethnic pride along with a growing awareness, interest, and understanding of the majority, children in minority groups are becoming more secure and confident in their racial or ethnic identity. Individuals vary in their reactions to membership in a minority group, and much of this variation can be attributed to familial factors. The most important influences on development of a positive self-image are warm, understanding parents who actively foster their children’s growth. Parents who accept their children and react positively and constructively rather than in a negative manner will help their children develop feelings of self-worth, self-esteem, and self-acceptance. The more adequate children feel, the more positive their attitudes toward peers in both the majority and minority groups and the greater their ability to withstand prejudice and intolerance and build lasting relationships.

Social Roles

Much of children’s self-concept comes from their ideas about their social roles. Roles are cultural creations; therefore the culture prescribes patterns of behavior for persons in a variety of social positions. All persons who hold similar social positions have an obligation to behave in a particular manner. A role prohibits some behaviors and allows others. Because culture outlines and clarifies roles, it is a significant influence on the development of children’s self-concept (i.e., attitudes and beliefs they have about themselves).

A social group consists of a system of roles carried out in both primary and secondary groups. A primary group has intimate, continued, face-to-face contact; mutual support of members; and the ability to order or constrain a considerable proportion of individual members’ behavior. Two such groups are the family and the peer group, both of which have a great deal of influence on the child.

Secondary groups are groups that have limited, intermittent contact and generally less concern for members’ behavior. These groups offer little in terms of support or pressure toward conformity except in rigidly limited areas. Examples of secondary groups are professional associations and social organizations such as church groups.

A concept of social role also depends largely on whether a child is reared in a primary- or secondary-group community. Children are subjected to perceptibly different forms of parental training in these two types of environments.

Primary- and Secondary-Group Influences

Children are raised within a primary-group environment and within a secondary-group environment. The influences, strengths, and limitations of both groups are significant. In a primary-group community (e.g., family; peer group; some contemporary rural, religious, or ethnic communities), all members know each other, most belong to the same subgroups, and all are concerned about each member’s behavior. Community members have a high degree of material and psychologic support and one traditional set of values that the entire group agrees on and supports; thus there is little conflict of values. In a stable community where the members remain within comparatively defined limits and relatives are likely to live close together, young members have ample opportunity to observe and absorb cultural practices and customs. Any member of the community feels justified in evaluating and censuring the conduct of another member.

Children reared in the relative isolation of secondary-group environmental influences tend to learn that there is only one acceptable way to respond to any given situation. The entire group agrees, and any tendency to deviate is met with collective disapproval. It is the parents’ duty to see that the children learn and follow social roles and modes of behavior defined and strengthened by the views of the community.

The childrearing orientation in a secondary-group environment, such as urban communities, can differ considerably from that of a primary-group environment. The interaction between primary and secondary groups may reinforce values when both groups endorse that value, or create confusion or conflict when one group rejects a value accepted by the other. An urban community is dynamic. Many of the traditional behaviors and values may not meet the needs of the changing society. Consequently, parents are often uncertain about what to teach their children. They may wish to rear their children with values consistent with their own, but the differences in experience between the generations are too great. As a result, they often grant their children autonomy in some areas of decision making early in the developmental process, and other secondary groups assume a greater influence. None of the groups is highly dominant in its influence; therefore the children are exposed to an eclectic set of values and expectations, some in agreement and some in conflict. From these they must ultimately select those that they determine to be best for them and adopt them to form a consistent set of roles and behaviors to incorporate into the self-concept.

Self-Esteem and Culture

Culture influences a child’s sense of self-esteem (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Some cultures are more collective in thought and action. A child from a collective culture will hold an inclusive view of self. Self-evaluation is related to the accomplishments or competencies of the entire family or community. School experiences that focus on personal achievement may promote positive self-esteem in some children but not in others who are more dependent on the success of a whole family or peer group. Their sense of control may not come from individual self-reliance but rather from a feeling of worth in their family or community (Trawick-Smith, 2006).

Families and culture also influence the criteria children use to evaluate their own abilities. Additionally cultures vary in whether they instill an internal locus of control (a belief in the ability to regulate one’s own life). Effects on self-esteem are minimal if these beliefs are directed by parents and are in accordance with cultural customs (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Ethnic pride can help children to maintain a positive self-image and counteract the effects of prejudice, which can have a negative impact on emotional health (Trawick-Smith, 2006).

Cultural Shock and Cultural Competence

Cultural shock is characterized by the inability to respond to or function within a new or strange situation. It can occur when the values and beliefs of a new cultural setting are radically different from those of the person’s native culture (Munoz and Luckmann, 2005). This state of shock or uneasiness can happen to a patient in a hospital or to a nurse caring for patients with different cultural backgrounds. Immigrants to a new country and persons from a subcultural group experience the same cultural shock when they must adjust to the ways of an unfamiliar subgroup or setting.

Numerous factors influence reactions to a new environment. Language barriers, including dialects and jargon specific to a subcultural group, inhibit effective communication. Habits and customs, such as different role behaviors or etiquette, and differences in attitudes and beliefs are puzzling to the newcomer in an unfamiliar environment. The child and family experiencing cultural shock can feel an intense sense of isolation, loneliness, and fear (Crom, 1995).

Nurses are challenged to overcome cultural shock and develop cultural sensitivity, an awareness of cultural similarities and differences. Doing so helps the nurse practice culturally competent care. This requires changing the way people think about, understand, and interact within the world around them (see Critical Thinking Exercise). The development of cultural competence is an ongoing, interactive process that involves six elements (Dunn, 2002):

1. Working on changing one’s world view by examining one’s own values and behaviors and working to reject racism and institutions that support it

2. Becoming familiar with core cultural issues by recognizing these issues and exploring them with patients

3. Becoming knowledgeable about the cultural groups one works with while learning about each individual patient’s unique history

4. Becoming familiar with core cultural issues related to health and illness and communicating in a way that encourages patients to explain what an illness means to them

5. Developing a relationship of trust with patients and creating a welcoming atmosphere in the health care setting

6. Negotiating for mutually acceptable and understandable interventions of care

When minority groups immigrate to another country, a certain degree of cultural and ethnic blending occurs through the involuntary process of acculturation, those gradual changes produced in a culture by the influence of another culture that cause one or both cultures to be more similar to each other. However, the changes occur to various degrees in different families and groups. Many groups continue to identify with their traditional heritage while adapting to the ill-defined concept of the “American way.” Acculturation may be referred to as assimilation, which is the process of developing a new cultural identity (Spector, 2009).

Subcultural Influences

Except in rare situations, children grow and develop in a blend of cultures and subcultures. In a large, complex society such as the United States, different groups have their own set of standards, values, and expectations within the collective ways of the large culture. Most subcultures were formed when groups of people clustered together by preference, by external pressures from the majority culture, or by geographic isolation. Although many cultural differences are related to geographic boundaries, subcultures are not always restricted by location. Some subcultures are even related to the stages of development and have traditions, games, loyalties, and rules. The behavior of school-age children and adolescents demonstrates age-related subcultures. The culture is handed down by word of mouth from one “generation” to the next, and its rituals and behavior standards are highly resistant to outside influence.

Children’s membership in a cultural subgroup is, for the most part, involuntary. They are born into a family with a specific ethnic or racial heritage, socioeconomic level, and religious beliefs. Although the complex American society has countless subcultures and considerable variation in the way of life, those subcultures that seem to have the greatest influence on childrearing are ethnicity, social class, and occupational role. In addition, schools and peer-group subcultures are strong influences in the socialization of the child.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity is the classification of or affiliation with any of the basic groups or divisions of humankind or any heterogeneous population differentiated by customs, characteristics, language, or similar distinguishing factors. Ethnic differences extend to many areas and include such manifestations as family structure, language, food preferences, moral codes, and expression of emotion. Some standards of behavior (e.g., the traditional role of the father) result from the cultural heritage of the specific ethnic group. Others reflect the interaction between subcultures, most notably between members of the majority culture and a minority subculture. The term ethnic has aroused strong negative feelings, and the general population often rejects this term (Spector, 2009).

To establish their place in the group, children learn to follow a mode of behavior that is in accordance with standards distinctive to the group and learn how they can expect others to behave toward them. They take their cues by observing and imitating those to whom they are exposed. For example, children of a racial minority form a perception of their role as a group member by observing how role models within the subgroup respond to treatment by people outside the subgroup. When they see group members display an attitude of inferiority, they assume this to be the appropriate behavior and incorporate these perceptions into their own self-concept.

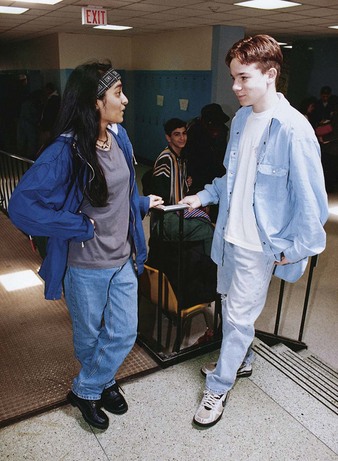

In the United States the cross-cultural lines are becoming blurred as subcultures are assimilated and blended into the larger culture (Fig. 2-1). Although ethnic differences in childrearing are probably diminishing, they remain important. It is particularly difficult for persons to attempt to maintain an identity within a subculture while living and conforming to the requirements of the larger culture.

Leavitt, Martinson, Liu, and colleagues (1999) found that immigrants from China who provided care for their children with cancer focused on dietary intake, whereas families that were of Caucasian descent focused on emotional support. The cultural framework directed the healing practices. Interestingly, the same study found that both groups shared the beliefs that mothers were the primary caregivers for the sick child. In this example one cultural behavior was unique to each cultural group while the other was similar. Consequently, children reared in this environment can become confused about roles and values of two or more cultures if they conflict. They usually adopt those of the more influential or higher-status culture. Youth, in particular, are influenced by the locally dominant group.

Ethnocentrism is the emotional attitude that one’s own ethnic group is superior to others; that one’s values, beliefs, and perceptions are the correct ones; and that the group’s ways of living and behaving are the best way (Spector, 2009). Ethnic stereotyping or labeling stems from ethnocentric views. Ethnocentrism implies that all other groups are inferior and that their ways are not in the best interests of the group. It is a common attitude among a dominant ethnic group and strongly influences a person’s ability to evaluate objectively the beliefs and behaviors of others. Nurses must overcome the natural tendency to have ethnocentric attitudes when caring for people from different cultures (Williams and Kruse, 1999). The culturally competent nurse has empathy for others, maintains an openness to feeling what the other feels, and remains curious and willing to ask questions to gain a better understanding. In addition, the nurse has a basic respect for self and others, and acknowledges the intrinsic value of all humans (Carrillo, Green, and Betancourt, 1999).

Minority-Group Membership

The United States has more racial, ethnic, and religious minority groups than any other country. Ethnic minority groups are becoming increasingly important because these groups are producing children at a faster rate than the majority Caucasian population. Consequently, the minority population is increasing. The rapidly emerging U.S. minority population will present special needs and require resources beyond what is currently available (Murdock, 2005).

The 2000 U.S. census revealed more than 280 million people in the United States, with 6.8 million reporting an ethnicity of more than two races. Blacks, or African-Americans, alone or in combination with another race, number more than 35 million, and Hispanics or Latinos of any race are more than 35 million. The Hispanic population increased 58%, or 13 million people, from 1990 to 2000 (US Census Bureau, 2001). Currently, Hispanics are the fastest growing minority in the United States and have many health needs that are not being met (Murdock, 2005; Warda, 2000). By the year 2010, Hispanics will surpass non-Hispanic blacks as the largest U.S. racial or ethnic group. In 2050 almost 30% of the U.S. population is expected to be Hispanic (Murdock, 2005) (see Cultural Competence box).

Socioeconomic Class

Family relationships may be stronger in some ethnic or cultural groups than others. However, the influence of socioeconomic class cannot be overlooked. This relates to the family’s economic and educational levels. Strong family relationships exist among those of lower socioeconomic class who have few resources and must rely on the support of a family network to meet physical and emotional needs. Middle- and upper-class people often have resources that reach beyond the extended family. They are able to access physical and emotional support in the community (Giger and Davidhizar, 1999). Do not confuse the term socioeconomic class with cultural or ethnic diversity. Children of a specific race are not necessarily of low socioeconomic status. Additionally, children of poverty do not automatically have developmental delays (Trawick-Smith, 2006).

Communication Skills

Any concept that occurs to a person can be expressed in language. However, ease of communication and use of language codes vary among the social classes. Language is much more restricted in the lower classes, and grammar usage differs more than pronunciation. Persons in the middle classes use different grammar from those in the lower classes and are able to express more complicated ideas; persons in the lower classes use very simple grammar and are less likely to offer explanations.

These communication differences are highly significant in relation to school achievement. School is constructed around the elaborate language codes of the middle class; therefore children from the lower class who lack an understanding of these language skills are placed at a decided disadvantage. This is particularly true for bilingual children and children from ethnic groups that have developed a unique dialect.

Historically, schools have participated in devaluing Native American languages, cultures, and traditional ways of learning and knowing (Robinson-Zanartu, 1996). Unfortunately, Native American children have been deficient in their preparation for school (Dykeman, Nelson, and Appleton, 1995). Also, children of Native American nations have been at risk for low achievement, overrepresentation in special education, and dropping out (Robinson-Zanartu, 1996). Many regional dialects and variations in language usage must be considered when communicating with persons from these groups. English words that sound like another word in a foreign language can cause considerable misunderstanding.

Schools

When children enter school, their radius of relationships extends to include a wider variety of peers and a new focus of authority. Although parents continue to exert the major influence on children, in the school environment teachers have the most significant psychologic impact on their development and socialization. The teachers’ function is primarily limited to teaching, but, like parents, they are concerned about the children’s emotional welfare. Both parents and teachers must constrain behavior and enforce standards of conduct.

Socialization

Next to the family, the schools exert the major force in providing continuity between generations by conveying a vast amount of culture from the older members to the young. This prepares children to carry out the traditional social roles they are expected to assume as adults in society. School is the center of cultural diffusion wherein the cultural standards of the larger group are disseminated to the local community. It governs what is taught and, to a large extent, how it is taught. School rules and regulations regarding attendance, authority relationships, and the system of penalties and rewards based on achievement transmit to the child the behavioral expectations of the adult world of employment and relationships. School is often the only institution in which children systematically learn about the negative consequences of behaviors that depart from social expectations. In addition, the school provides an opportunity for some children to participate in the larger society in rewarding ways and often provides avenues for social mobility for both students and teachers. Individuals in the lower classes are offered the opportunity for further education and the capacity to move up in the social strata.

Teachers are responsible for transmitting the knowledge and values of the dominant culture (i.e., those values on which there is broad consensus). They are expected to stimulate and guide children’s intellectual development, sense of esthetics, and creative problem solving.

Traditionally the socialization process of school began when the child entered kindergarten or first grade. Today, with more than 60% of mothers of preschool children working outside the home, this socialization process begins much earlier for a significant number of children in a variety of childcare settings.

Children of some cultural groups fare less well in school. They come from underrepresented groups, including African-American, Mexican-American, Puerto-Rican, and Native-American children (Trawick-Smith, 2006). These cultural variations can be attributed to high rates of poverty, different cognitive styles, ineffective schools, and parents’ views of schools as oppressive to cultural and traditional values (Trawick-Smith, 2006).

Communities

Surveys of more than 1 million youth in the United States in grades 6 to 12 have shown that persons who experience a higher number of specific assets in their lives are more likely to make healthy choices and avoid high-risk behaviors. These assets offer a framework for positive child and adolescent development. The child or adolescent’s community is made up of family, school, neighborhood, youth organization, and other members.

Four categories of external assets that youth receive from the community are (Search Institute, 2007):

1. Support—Young people need to feel support, care, and love from their families, neighbors, and others. They also need organizations and institutions that offer positive, supportive environments.

2. Empowerment—Young people need to feel valued by their community and be able to contribute to others. They need to feel safe and secure.

3. Boundaries and expectations—Young people need to know what is expected of them and what activities and behaviors are within the community boundaries and what are outside of them.

4. Constructive use of time—Young people need opportunities for growth through constructive, enriching opportunities and through quality time at home.

Internal assets must also be nurtured in the community’s young members. These internal qualities guide choices and create a sense of centeredness, purpose, and focus. The four categories of internal assets are (Search Institute, 2007):

1. Commitment to learning—Young people need to develop a commitment to education and life-long learning.

2. Positive values—Youth need to have a strong sense of values that direct their choices.

3. Social competencies—Young people need competencies that help them make positive choices and build relationships.

4. Positive identity—Young people need a sense of their own power, purpose, worth, and promise.

Social Capital

Social capital is a health-related concept that provides a way for pediatric nurses to include a social context in their assessments. It considers where and how the children and families they care for live. Social capital is defined as the total sum of the social relationships within the family and the family’s relationship with peers, with institutions (schools, clubs, faith-based organizations), and with communities that affect the health and well-being of children (Looman and Lindeke, 2005). It is the way people mobilize resources and allows them to turn relationships into resources. Families develop a sense of belonging and find strength in knowing others in the same situation (Looman, 2004). The focus is on the interaction rather than specific supports. Research shows that social capital is related to positive health outcomes (Looman and Lindeke, 2005). Pediatric nurses can include social capital in their practice by bringing families, community members, and professionals together for a common purpose. Nurses can also include social capital in practice by encouraging repeated contacts over time, encouraging storytelling, and advocating for community experiences that enhance health-promoting behaviors (Looman and Lindeke, 2005).

Peer Cultures

Peer groups also have an impact on the socialization of children (Fig. 2-2). Peer relationships become increasingly important and influential as children proceed through school. In school, children have what can be regarded as a culture of their own. This is even more apparent in an unsupervised playgroup, since in school the culture is partly produced by adults.

Fig. 2-2 Children from a variety of cultural and ethnic backgrounds begin to socialize in the child care setting.

During their lives children are exposed to value systems such as those of the family, ethnic group, and social class. In peer-group interaction they confront a variety of these sets of values. The values imposed by the peer group are especially compelling because children must accept and conform to them to be accepted as members of the group. When the peer values are not too different from those of family and teachers, the mild conflict created by these small differences serves to separate children from the adults in their lives and to strengthen the feeling of belonging to the peer group.

The kind of socialization provided by the peer group depends on the subculture that develops from its members’ background, interests, and capabilities. Some groups support school achievement, others focus on athletic prowess, and still others are decidedly against educative goals. Scholastic achievement is strongly related to the peer group’s value system. Many conflicts between teachers and students and between parents and students can be attributed to fear of rejection by peers. What is expected from parents regarding academic achievement and what is expected from the peer culture often conflict, especially during high school. Chapter 19 discusses this in further detail.

Although the peer group has neither the traditional authority of the parents nor the legal authority of the schools for teaching information, it manages to convey a substantial amount of information to its members, especially on taboo subjects such as sex and drugs. Children’s need for the friendship of their peers brings them into an increasingly complex social system. Through peer relationships, children learn to deal with dominance and hostility and to relate with persons in positions of leadership and authority. Other functions of the peer subculture are to relieve boredom and to provide recognition that individual members do not receive from teachers and other authority figures.

The peer-group culture has secrets, mores, and codes of ethics that promote group solidarity and detachment from adults. They have traditions and folkways, including age-related games and other activities, that are transferred from “generation to generation” of schoolchildren and that have a great influence over the behavior of all group members. As children move from one level to the next, they discard folkways of the younger group as they adopt those of the new group. For example, a school-age child rides a bicycle to school; the high school student prefers a car. As they advance, children are forward oriented only—they look forward with anticipation but may look backward with contempt.

Biculture

Some children are exposed to the values, role relationships, and lifestyles of two or more cultures. The virtual “straddling” of two cultures is referred to as biculturation and involves the ability to efficiently bridge the gap between an individual’s culture of origin and the dominant culture (Rogers, 1995). This may occur because the child’s parents are from two or more different cultures. In Hawaii, for example, it is common for children to be from four or more cultures. Other children straddle cultures as members of a minority culture within the dominant culture. This biculture is sometimes observed in the playgroup but usually is not a significant factor until children enter school. Then they must unlearn some of the established practices of one culture to become socialized in the other, especially in role relationships. For example, children from Hispanic and Asian cultures are taught to look away when scolded; in U.S. schools the teacher expects direct eye contact—“Look at me when I speak to you.” Children learn new roles and social behavior more rapidly than their adult counterparts.

This biculture is particularly marked in language differences. The bilingual child is said to be at a disadvantage in school situations of the dominant culture, in which there is controversy over bilingual education. Those supporting bilingual education adhere to the principle that children will understand more readily and perform more realistically (especially in testing situations) if learning is directed in their own language; others contend that children living in a dominant culture should adopt the ways of that culture, including language. The child faces less conflict when the school supports his or her language and culture, even if the dominant language is used.

Mass Media

The media provide children with a means for extending their knowledge about the world in which they live and have helped narrow the differences between social classes. However, many people are concerned about the enormous influence the media can have on the developing child and on health promotion behaviors (see Research Focus box). Children and adolescents in the United States spend more than 6 hours per day utilizing entertainment media (Council on Communications and Media, 2009). Increased use of entertainment media has been associated with the epidemic of obesity in children and adolescents and increased aggression in children (Jordan, 2004; Council on Communications and Media, 2009).

Children may identify closely with people or characters portrayed in reading materials, movies, videos, and television programs and commercials. Pediatric nurses can educate and support parents on the effects of mass media on their children through the following recommendations (Jordan, 2004):

• Be aware of the content of the child’s media and amount of time spent looking at a screen.

• Help young children watching television to find educational programs.

• Remove television, Internet-accessible computers, and videogame systems from the bedroom to decrease the amount of time spent using these activities.

• Limit television viewing to 2 hours a day or less.

• Watch age-appropriate programs and play age-appropriate games with children.

Reading Materials

The oldest form of mass media—books, newspapers, and magazines—contributes to children’s competence in almost every direction and provides enjoyment. Recognition of the impact that reading matter in schools has on value systems and the socialization process has prompted reevaluation of textbook content in several areas, such as stereotyped male and female role models, the sugar-coated view of life situations, and the biased history of minority groups.

Reading aloud to children is a vital activity in promoting success in reading. It provides cognitive and language stimulation, is a forum for quality parent-child interaction, and may reduce parent stress (Klass, Needlman, and Zuckerman, 2002).

Movies

Movies that are not closely bound to reality and often portray an assortment of socially approved behaviors perhaps make a contribution to children’s value systems and do provide opportunities for desirable social learning. On the other hand, children, especially adolescents, flock to “macho” movies and those whose heroes resort to violent resolution of problems, such as karate and wild automobile chases. The carryover of these influences into daily life and relationships may account in part for the increase in violent behavior of young persons.

A recent concern is the violent and R-rated movies available to children and teenagers in theaters and through cable television and DVDs. The content of movies has changed markedly over the past few years, with mutilation being a major theme. To children who are unable to distinguish between reality and fantasy, these films play on their deepest fears and result in bedtime fears, nightmares, and a fearful view of the world.

Television

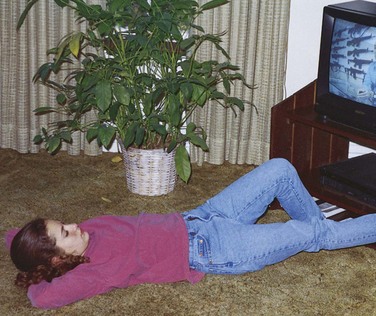

The medium that has the most impact on children in the United States today is television; it has become one of the most significant socializing agents in the lives of young children. The programs and commercials provide multiple sources for acquiring information, modeling behaviors, and observing value orientations. Besides producing a leveling effect on class differences in general information and vocabulary, TV exposes children to a wider variety of topics and events than they encounter in day-to-day life. Television always has time to talk to children and is a form of access to the adult world. Positive results occur only when viewing is relatively light, yet the average child in the United States over the age of 8 spends more time watching television or using a computer and video games (>6 hours/day) than in any other activity except sleeping (Fig. 2-3) (Council on Communications and Media, 2009).

Fig. 2-3 The average child in the United States spends more time watching television than in any other activity except sleeping.

Television can offer some beneficial effects on the growing child. In their follow-up study of adolescents who had participated as preschoolers in an investigation of television use, researchers found that children who viewed educational programs as preschoolers had higher grades, read more books, valued achievement, had greater creativity, and were less aggressive (Anderson, Huston, Schmitt, et al, 2001).

Most researchers have concluded, however, that protracted television viewing can have negative effects on children. Increased verbal and physical aggressiveness, reduced persistence at problem solving, greater sex-role stereotyping, and reduced creativity have been reported repeatedly. In fairness, no one has yet defined the long-term effects of other electronic factors such as stereo headphones versus conversation, computer games or drills versus active social play, or DVDs versus books. However, clearly children in the modern electronic environment are constantly stimulated from the outside, which allows them little time to reflect and develop the inner speech that feeds brain development.

Most programs are designed to attract attention by visual jolts; the child establishes the habit of ignoring language in favor of hectic visual and auditory gimmicks. Like movies, television programs and commercials contain many implicit and explicit messages that promote alcohol consumption, smoking, violence, and promiscuous or unsafe sexual activity. An area of particular concern is unmonitored use of the Internet with videos sensationalizing violence, sex, suicide, and other destructive behaviors.

Socioeconomic Influences

A subcultural influence closely related to but different from social class is the condition known as poverty. It is a relative concept and is usually associated with the general standards of a population. The term poverty implies both visible and invisible impoverishment. It is a condition in which families live without adequate resources (Trawick-Smith, 2006). Visible poverty refers to lack of money or material resources, which includes poor nutrition, insufficient clothing, poor sanitation, and deteriorating housing. Invisible poverty refers to social and cultural deprivation such as limited employment opportunities, inferior educational opportunities, lack of or inferior medical services and health care facilities, and an absence of public services.

An absolute standard of poverty attempts to delimit a basic set of resources needed for adequate existence; a relative standard reflects the median standard of living in a society and is the term used in referring to childhood poverty in the United States; that is, what appears to be deprivation in one area may be a standard or norm in another.

An important development affecting the American family since the end of World War II is the widening disparity in income status among generations. Children from families with a single mother compose the largest group of children in poverty in the country (Wertheimer, 2005).

Growth in the number of poor children over the past decade has not been due to an increase in the number of welfare-dependent families, but to growth in the ranks of the working poor. Between 1994 and 2000, the poverty rate fell approximately 30%, but the trend has recently reversed, and the poverty rate rose 6% between 2000 and 2007. Approximately 18% of children in the United States live below the national poverty threshold, which is currently estimated at $21,027 for two adults and two children (Annie E Casey Foundation, 2009). In addition, approximately 20% of children live in neighborhoods where more than 20% of the population currently lives below the federal poverty threshold.

Such factors illustrate the growing inability of the American family to provide economic essentials for their children. Approximately 11.6% (about 8.5 million) of all children in the United States were uninsured in 2002 (Szilagyi, 2005). Uninsured children are more likely to miss school, jeopardizing their education as well as their health.

A high correlation between poverty and illness has long been observed. Impoverished families suffer from poor nutrition; without medical insurance, they have little if any preventive health care, inadequate health maintenance, and limited access to health services. One of the most significant health problems related to poverty is a high infant mortality rate. Although the rate of infant mortality has decreased in the United States, it still remains higher than that of most industrialized nations (Annie E Casey Foundation, 2009). Day-to-day needs of food, clothing, and lodging take precedence over health care as long as the ailing person feels able to perform activities of daily living.

Poor families may be denied access to some institutions for emergency or other hospital care. Frequently they must travel long distances to service centers that are willing to assume their care. In an emergency they must find money for taxi fare, borrow an automobile, or seek other means of transportation. They must find care for dependents, such as other infants and small children, or take them along when taking the ill child for care. Families tend to delay preventive care indefinitely unless health services are relatively accessible. They are more likely to consult folk practitioners or other persons within their community.

Poor nutrition accounts for many health problems in the lower classes. Lack of funds, education, and readily available healthy foods results in a diet that may be seriously lacking in essential food substances, especially protein, vitamins, and iron. This inadequate diet often leads to nutritional deficiency disorders and growth retardation in children. On the other hand, these issues may contribute to pediatric overweight and type 2 diabetes because nonnourishing foods are less expensive and are easier to access in some neighborhoods.

Dental problems are more prevalent because of deficient preventive care. Lack of standard immunizations together with reduced resistance from poor nutrition renders children in poor segments of the population vulnerable to communicable diseases. Poor sanitation and crowded living conditions also contribute to the higher incidence and perpetuation of illness. In general, poor people become ill more frequently and remain ill for longer periods than those in the general population.

Homelessness

One of the most pressing problems in the United States is the growing number of homeless families. Homeless individuals are those persons who lack resources and community ties necessary to provide for their own adequate shelter. In the past the homeless population traditionally included single adults, mostly men. Families with children make up 40% of the homeless population, compared with single men, who make up about 41% of the group (Redlener, 2005). Homeless children have increased in numbers as poverty has become feminized, minorities have become poorer, and low-income housing has become less accessible. Estimates of the number of homeless children in the United States may be as high as 1 million; about 10% of the children living in poverty were homeless (Redlener, 2005). Many homeless children are younger than 5 years and are from minority groups.

Most homelessness is a direct result of increasing number of people in poverty combined with a lack of decent, affordable housing. Other reasons include job layoffs, low incomes, parental mental illness, domestic conflict, and unexpected family or economic crises.

Another group of homeless children are the “runaway” and “throwaway” adolescents. Approximately 12% of the homeless population consists of adolescents (National Coalition to End Homelessness, 2009). Many runaways are victims of physical and sexual abuse and leave home because of long-term family or school problems. Poor parent-child relationships, extreme family conflict, feelings of alienation from parents, inconsistent supervision, and unpredictability in discipline are other factors often cited. These adolescents and young adults are at risk for violence, exploitation, substance abuse, and sexually transmitted infections (including HIV and AIDS).

Lack of a permanent housing deprives children of the most basic necessities for proper growth and development. Homelessness disrupts a child’s friendships and schooling (Strehlow and Amos-Jones, 1999). Homeless children suffer from physical and mental disorders more often than do poor children who have a permanent residence. Homeless children lack basic health care, including routine immunization and screening for routine problems, and they suffer high rates of acute and chronic illnesses (Redlener, 2005).

Migrant Families

Children in migrant farm worker families are medically underserved. Their numbers are staggering; of the 2 million migrant farm workers who labor in the United States, 63% are accompanied by minor children (Gentry, Quandt, Davis, et al, 2007). These children face both acute and chronic health care issues as a result of poverty, parental occupation, and assimilation into American culture. They are often exposed to risks similar to those facing their parents, since they may accompany them into the fields. These children frequently live in substandard housing conditions, which are subject to overcrowding and transmission of communicable diseases.

Migrant farm worker families face many obstacles when attempting to interface with the U.S. health care system. Three of every five families live below the federally designated poverty line and may lack insurance. The family’s use of health care may be affected by parental work schedules and access to transportation. Their own limited English proficiency is further exacerbated by a health care encounter that lacks cultural sensitivity, translation services, and language capability. Cultural expectations of the health care system may differ between the farm worker families and health care providers. This may ultimately have a negative effect on families’ utilization of the health care system. In fact, many families living on the U.S.-Mexico border seek the majority of care for their children in Mexico, regardless of their insurance status. In addition, less than 20% of migrant farm worker families use the primary care and health promotion centers that are federally funded through the 1962 Migrant Health Act (Gentry, Quandt, Davis, et al, 2007). ![]() These two statistics demonstrate the need for culturally sensitive care that is consistent with the perceived needs and expectations of the recipients of such care.

These two statistics demonstrate the need for culturally sensitive care that is consistent with the perceived needs and expectations of the recipients of such care.

![]() Skill—Providing Culturally Sensitive Care

Skill—Providing Culturally Sensitive Care

Nurses and other health care providers should be mindful of the persistence of various forms of child labor in the United States (Hindman, 2006). Approximately 50% of 12- to 15-year-olds participate in some sort of paid activity each year, and half of this population have jobs in which they are considered employees. Children, adolescents, and young adults may work in a variety of areas, including agriculture, construction, retail, or even street trades or scams. Youth who work on family farms often face the greatest risk of injury and death from handling dangerous or heavy machinery. Youth who work in street trades and scams or traveling sales crews may be subject to physical or verbal abuse or victimization (Hindman, 2006).

Cultural Influences

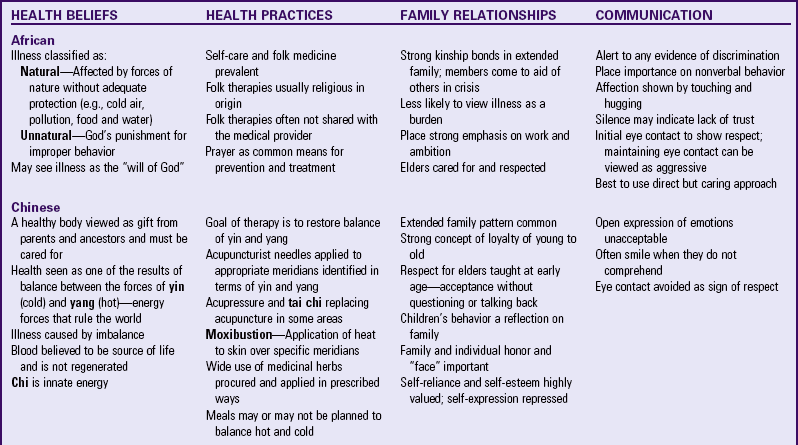

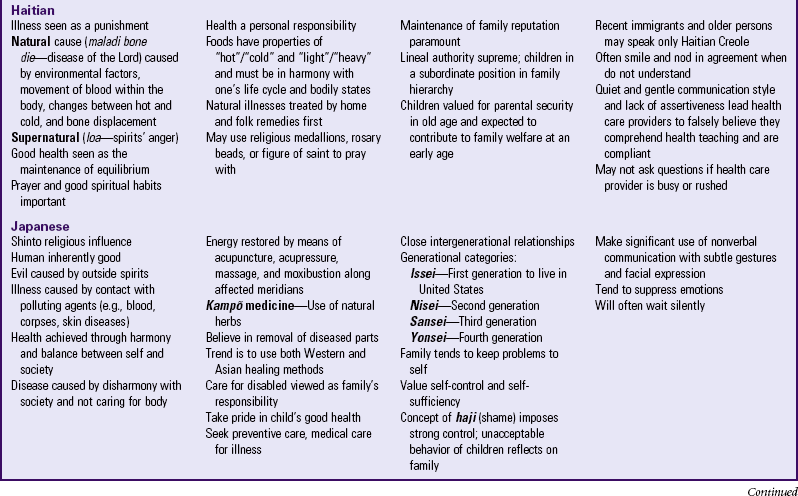

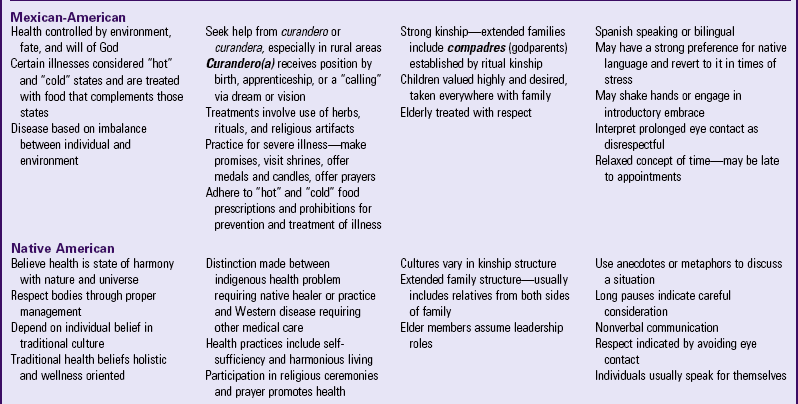

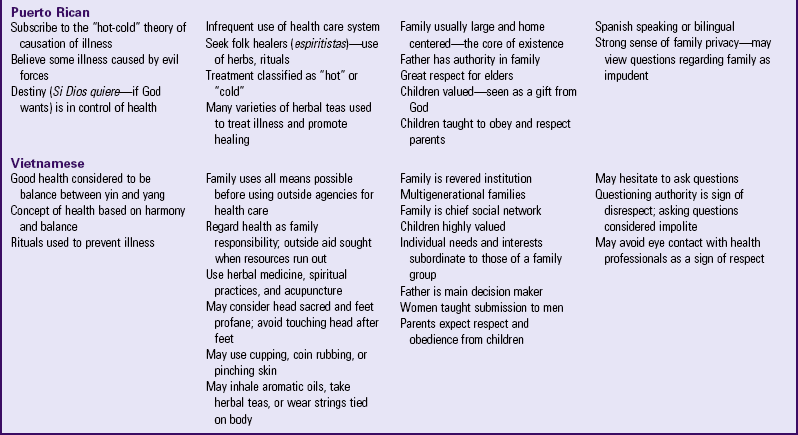

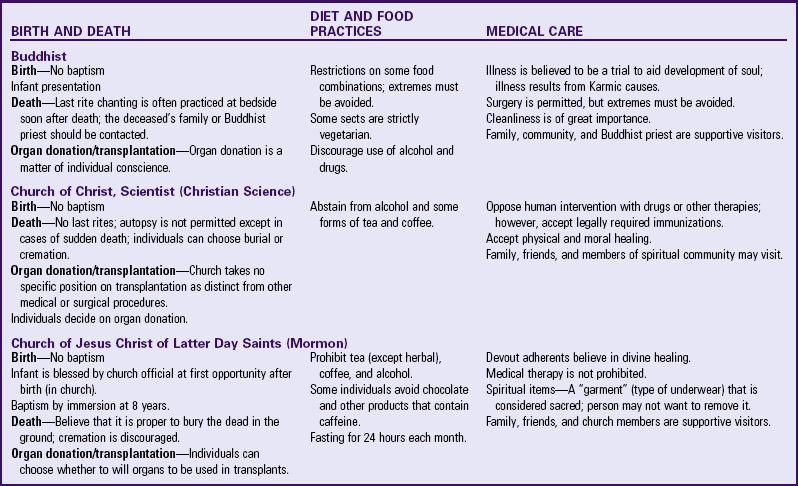

![]() Nurses need to consider clients’ cultural differences when providing health care. An understanding of the various beliefs regarding the causation of illness and disease, as well as traditional health practices, is essential to successful intervention. The more nurses know about the values, beliefs, and customs of other ethnic groups and how to elicit this information from families, the better they are able to meet the needs of these families and to gain their cooperation and compliance.

Nurses need to consider clients’ cultural differences when providing health care. An understanding of the various beliefs regarding the causation of illness and disease, as well as traditional health practices, is essential to successful intervention. The more nurses know about the values, beliefs, and customs of other ethnic groups and how to elicit this information from families, the better they are able to meet the needs of these families and to gain their cooperation and compliance.

![]() Case Study—Cultural Considerations

Case Study—Cultural Considerations

Cultural Relativity

Although clinical characteristics of a disease or condition are essentially the same across cultures, how a child or family interprets or experiences the disease or condition varies. Culture as an influence is one obvious explanation for variance. Cultural relativity is the concept that any behavior must be judged first in the context of the culture in which it occurs. Cultural factors such as belief systems and view of the world influence the patient’s and family’s response to health care. These cultural beliefs and behaviors influence adherence to a treatment plan (Munoz and Luckmann, 2005). Some cultures, for example, may view a chronic illness or disability as affecting only particular aspects of a child’s life, and the child as a whole is viewed as normal. In contrast, other families may describe the illness as having global effects on many aspects of the child’s present and future life (Martinson, Armstrong, and Qiao, 1997). These contrasting views may result in parents having different goals and expectations for their children.

Culture influences the assignment of gender roles, perception of disease, and perception of the side effects of the disease and the treatment the child should receive. For example, the family may expect the mother to be the primary caregiver. This places her at risk for caregiver strain when she is caring for a sick child.

Nurses can often recognize a family’s health-related cultural perceptions and interpretations through discussion and observation. They should explore and consider implications of these perceptions when planning culturally appropriate interventions. Nurses must be comfortable having discussions with families about their cultural beliefs and practices. The conversations can begin easily as, “I want to take the best care of your child and family as possible. Is there anything in particular about your beliefs [cultural, religious, family] that you think I should know?”

Relationships with Health Care Providers

The manner of relating with health care providers differs considerably among cultural groups. For some nurses, one area of conflict is the attitude toward time and waiting that is part of some cultures. The time orientation of Hispanic and African-American ethnic groups is in the present. For example, African-Americans are flexible in their time orientation; an African-American family may be late for or miss appointments because other issues take precedence, and they may not communicate this to the health agency. Hispanics, too, have a relaxed view of time. Whereas the dominant culture in the United States says that “time flies,” the Hispanic says that “time walks.”

The Japanese, on the other hand, consider time to be valuable and to be used wisely. They tend to be punctual for medical appointments and persistent in following prescribed regimens. A Vietnamese family will subordinate time to values considered to be more significant, such as propriety. They may be late for an appointment because of an overextended visit by a friend in their home. In general, Asian-Americans view the American focus on time as offensive. They spend hours getting to know people and view predetermined, abrupt endings as rude. Introductory small talk is considered good manners.

Navajo Indians view time on a continuum with no beginning and no end. The present-time orientation may cause a Navajo to eat two meals a day today, four meals tomorrow, no meals the next day, and three meals the day after. This becomes an important nursing consideration if a Navajo is told to take medication with meals to ensure three doses per day.

In many cultural groups the mother assumes the responsibility for health care; in others both parents are involved equally in relationships with health workers. A somewhat different approach is apparent in some of the Asian cultures. For example, a Vietnamese or Filipino father, as unquestioned head of the family, is traditionally the one who interacts with persons, including health care providers, outside the family unit. In the Hispanic family the father, as head of the house, makes decisions regarding illness and treatment of adult family members, but the grandmother in the extended family is consulted regarding child care. Usually the family confers with other members before reaching a decision regarding treatment or hospitalization of a child. The Arab family also relies on others to give advice and guidance in a time of crisis. A Japanese father may appear to be passive and uninvolved but actually is involved according to his own cultural standards.

Nurses should learn about any specific attitudes regarding the manner of approach to a child in a given culture. Navajo Indians do not like a stranger near their infants. They fear that the stranger may “witch” the child and cause the child harm. On the other hand, if a stranger, particularly a woman, lavishes attention on a Hispanic infant but fails to touch the child, some Hispanics believe the infant will develop symptoms of the “evil eye” (see p. 33). Vietnamese and Korean families may become upset if a newborn is admired at length for fear the evil spirits will overhear and desire the infant.

Some groups, such as the Amish, consider a child’s admission to the hospital a family affair, with all members gathering to support and console the child and parents. In other groups the family is willing to relinquish the care of the child to the hospital authority without interference. Their visits with the child are short, although intense, but hospital staff may misinterpret this behavior as disinterest or abandonment.

All ethnic groups are entitled to be treated with dignity and respect. Family members should be addressed by their last names; many groups consider it an affront to be called by their first names. Stereotyping is to be condemned. People are individuals who are evaluated in relation to their cultural standards, needs, and preferences. For example, believing that fathers are never involved in the direct care of their child can result in wrong assumptions about a culture (Fig. 2-4).

Fig. 2-4 Many fathers assume an active parenting role. (Courtesy E. Jacob, Texas Children’s Hospital, Houston.)

Nurses who are members of a majority culture may encounter tension and distrust in a child from a minority culture as a result of the child’s learned conceptions or relationships with other persons in the majority group. Based on these perceptions, minority children may suspect that nurses have hostile feelings toward them and fear ill treatment. When such children are hospitalized, this suspicion increases the feelings of loneliness and helplessness that accompany fearful events and separation from families. The reverse situation may be encountered by a nurse from a minority culture attempting to meet the needs of a child who has been conditioned to view the nurse’s cultural or ethnic group as inferior. Either situation is more likely to occur if the nurse or the child has had little or no personal contact with the other’s culture. For example, a child from a minority culture from the inner city who lives in a neighborhood and attends school only with children from his or her minority culture may be more suspicious of a nurse from a different culture than would a child from the same minority group who lives in a culturally diverse neighborhood or attends an integrated school. Becoming familiar with cultures different from one’s own and making an effort to know each other as individuals can shatter myths and, with time, build the trust needed to establish rewarding relationships between children, their families, and the nurse.

Communication

Communication is basic to all human relationships, but it may be a source of distress and misunderstanding between persons from different ethnic groups, especially if the languages are different. Prejudice is one of the biggest barriers to cross-cultural communication. The Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has established national standards on culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care. Health care organizations must ensure the competence of language assistance provided to person with limited English proficiency by interpreters and bilingual staff. Family and friends should not be used for interpretation services except on the patient’s request (Shaw-Taylor, 2002). (See Communicating with Families Through an Interpreter, Chapter 6.)

Part of culturally sensitive communication is taking time to assess beliefs and values. In a study on childhood asthma, management researchers discovered that parents who believed asthma to be intermittent rather than a chronic condition provided suboptimal treatment to their child (Yoos, Kitzman, Henderson, et al, 2007). It is vital that the family members fully understand all implications of a child’s care and management before they consent for special procedures or assume responsibility for the child’s medication administration. Some persons with poor or limited language comprehension may simply smile and nod in agreement if they do not understand the questions or directives. It is not uncommon for an Asian family to indicate “yes” when in fact they mean “no” in order to avoid social disharmony. They tend to address issues indirectly rather than through confrontation and may become evasive when direct questioning makes them uncomfortable.

Nonverbal communication is a practiced art in many Native American tribes, and the members are highly sensitive to body language. They emphasize periods of silence to formulate thoughts in preparation for speech and often remain silent after listening to others to properly assimilate what has been said. Interruption, interjection, or haste to arrive at a conclusion is perceived as immature behavior.

Different cultures view eye contact differently. Although Caucasians are advised to look people straight in the eye, persons in some ethnic groups avoid eye contact and become uncomfortable when conversing with health care workers. In non-Western cultures a patient may not look directly into the nurse’s eyes as a sign of respect. Some Native Americans make eye contact during the initial greeting, but consider continued, unwavering eye contact insulting and disrespectful. Asians may consider eye contact a sign of hostility or impoliteness.

The level of comfort with body space or distance from others varies among cultures. Caucasians are generally comfortable at arm’s length, Hispanics tend to get closer, and some Asians prefer a greater distance. Also, gestures may have different meanings. For example, some Asians consider pointing with a finger or foot disrespectful. Some Native Americans consider vigorous handshaking a sign of aggression, whereas to Caucasians the gesture is a sign of goodwill and strong character.

Families may be reluctant to question or otherwise initiate contact with health professionals. In Asian cultures, for example, it is considered a sign of disrespect to question persons of authority. A Japanese family may wait silently rather than ask or question. They believe the health professionals know best and will meet their needs without being asked. They also think it is important to avoid criticism. Criticism can cause the Japanese-American to “lose face,” to feel ashamed, which is highly undesirable.

Language has been considered the biggest barrier to the use of health care services by many families, especially Southeast Asians (Mattson, 1995). Often, families may have poor language comprehension, so it is necessary to speak slowly and carefully, not loudly, when conversing with them. Many persons are able to read and write English better than they can speak or understand it. Also, people usually revert to their dominant language in anxiety-provoking situations, even if they are able to communicate satisfactorily under ordinary circumstances.

Terms of address and use of first and last names vary among cultures and can create confusion in institutions. For example, in Asian cultures, the family name is given first in respect for the family and the given names follow. Therefore all siblings in a family have the same first name (or, in some families, the same middle name). The Mennonites refer to children as sons and daughters of a particular parent, such as “Josiah’s son,” rather than by the children’s names.

Although all people share the basic emotions, there are decided ethnic variations in the ways emotions are expressed. People in some cultures (e.g., Italian, Latin, or Jewish background) express emotions openly and are accustomed to sharing their sorrows and joys with family and friends. Conversely, Nordic and Asian groups are more restrained in expressing emotion.

Health care providers generally ask questions and use handouts, booklets, and—particularly with children—dolls and pictures as communication aids. This is uncommon in some cultures. For example, Native American healers ask few questions and do not use forms. Nurses need to consider both verbal and nonverbal communication techniques to interact effectively with children and their families from different cultures (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Food Customs

Food customs and symbolism of various cultural, ethnic, and religious groups are an integral part of their lives. Although in a large country such as the United States most people have adopted the eclectic food habits that have evolved over generations, many still retain ethnic and geographic food traditions and preferences. Special holidays, ceremonies, and life experiences such as births, birthdays, weddings, and death are often marked by special food items or feasts. In many cultures specific food practices are followed during pregnancy in the belief that certain foods damage or benefit the developing fetus. The distinctive food customs of ethnic groups are a product of their native environment, determined by availability.

A number of restrictions are related to food items. Some have a physiologic origin, such as lack of dairy foods in the diets of some persons of African or Asian ancestry with lactose intolerance. Others are religious restrictions, such as kosher foods and food preparation of the Orthodox Jewish faith and the vegetarian diet of Seventh Day Adventists. (See Vegetarian Diets, Chapter 13.)

Children in a strange environment, such as the hospital, feel much more comfortable when they are served familiar foods. Hospital food often tastes strange and bland, especially to children who enjoy the highly seasoned foods of their culture. Also, the family may be concerned that the child is not receiving foods appropriate to their culture and beliefs. When possible, provide the children’s ethnic foods or allow families to bring favorite foods that are not on the hospital menu. Concern for differences in food habits and patterns projects an attitude of respect for the family’s ethnic or religious heritage (Ohio State University Extension, 2005).

It is also important for nurses and other health care providers to be mindful of the meaning of food and eating within a family or community. Feeding and food preparation are ways in which families nurture and care for one another. This is especially true in the parent-child relationship. Parents and other family members may struggle with this desire to feed and nurture their child in circumstances when the child does not want to eat or cannot tolerate oral intake (i.e., a child receiving chemotherapy). Nurses can encourage families to nurture the sick child in other ways, such as touch, reading, or other enjoyable activities.

Health Beliefs and Practices

The nurse encounters people of many different racial and ethnic origins in the process of meeting the health needs of children and families. Some of these families have become so enculturated to the majority culture that their health beliefs and practices are consistent with those of the health care system. For many families, however, traditional practices and beliefs are an integral part of their daily lives. Health care workers should be aware that other people might live by different rules and priorities, which decisively influence health-related behavior.

A model for learning about health traditions that differ from the Western, or modern, health care system is based on three dimensions:

1. What are the physical aspects of caring for the body (e.g., are there special clothes, foods, medicines)?

2. What are the mental parts of caring for health (e.g., feelings, attitudes, rituals, actions)?

3. What are the spiritual aspects of health (who I am, spiritual customs, prayers, healers)?

For each of these dimensions, one must consider the cultural traditions used to maintain health, protect health, and restore health (Spector, 2009).

Health Beliefs

The beliefs related to the cause of illness and the maintenance of health are an integral part of a family’s cultural heritage. Often inseparable from religious beliefs, they influence the way families cope with health problems and respond to health care providers. Predominant among most cultures are beliefs related to natural forces, supernatural forces, and imbalance between forces.

Natural Forces

The most common natural forces held responsible for ill health if the body is not adequately protected include cold air entering the body and impurities in the air. For example, a Chinese parent may overdress the infant in an effort to keep cold wind from entering the child’s body. The Chinese believe that cold weather, rain, or wind is responsible for “cold” conditions. They also believe that an innate energy called chi enters and leaves the body through the mouth, nose, and ears and flows through the body in definite pathways, or meridians, at specific times and locations. The Chinese believe that a lack of chi and blood causes fatigue, low energy, and a variety of ailments.

In the African-American culture, some individuals believe natural phenomena such as phases of the moon, seasons of the year, and planet positions affect the body and its processes; therefore health maintenance is strongly associated with the ability to read “the signs.” Some cultures consider behaviors such as overeating, overwork, anxiety, and inadequate food and sleep to be natural causes of illness. Most Native Americans consider health to be a state of harmony with nature and the universe.

Supernatural Forces

High on the list of causes of illness are forces beyond comprehension and logical explanation. Some cultures view evil influences such as voodoo, witchcraft, or evil spirits as causes of illness, especially those illnesses that cannot be explained by other means.

A health belief that is common among people from Latin American, Mediterranean, some Asian, and some African societies is the concept of the “evil eye” (Spector, 2009). It is part of the concept of health as a state of balance and illness as a state of imbalance (see following section). Strength and power are associated with the evil eye; therefore, as long as an individual’s strength and weakness remain in balance, he or she is unlikely to become a victim of the evil eye. Weaknesses are not necessarily physical. For example, an excess of some emotion, such as envy, can create weakness. Infants and small children, because of immature development of their internal strength-weakness states, are especially vulnerable to the gaze of the evil eye. Consequently, the evil eye serves to rationalize an inexplicable onset of illness in children who display symptoms such as restlessness, crying, diarrhea, vomiting, and fever.

Health Protection

Cultural traditions used in the protection of health may include protective objects, which may be worn, carried, or hung in the home or room. For example, amulets are objects or charms that are worn on a string or chain to protect the wearer from the evil eye or evil spirits. It is important to allow people to wear these objects in the health care setting. Another cultural practice is the inclusion of substances in the diet that protect health. For example, the ginseng root is used to “build the blood” in the Chinese culture. Religious practices, such as burning candles or prayer, are also traditions used to protect health (Spector, 2009).

Imbalance of Forces

The concept of balance or equilibrium is widespread throughout the world. One of the most common imbalances supported by the Hispanic, Filipino, Chinese, and Arab cultures is that which exists between “hot” and “cold.” This belief is reputedly derived from the Hippocratic theory of humoral pathology, which states that illness is caused by an imbalance of the four humors: phlegm, blood, black bile, and yellow bile (Sekhon, 1996). “Hot” and “cold” describe certain properties and conditions completely unrelated to temperature. Diseases, areas of the body, foods, and illnesses are classified as either “hot” or “cold.” In Chinese health belief the forces are termed yin (cold) and yang (hot) (Wang and Martinson, 1996). To maintain health and prevent illness, these forces must be kept in balance.

Illness is treated by restoring normal balance through the application of appropriate “hot” or “cold” remedies. A “cold” condition such as a respiratory disease is believed to be caused by exposure to cold weather, rain, or cold wind entering the body; it is treated by administration of “hot” foods, herbs, or drugs. Menstruation is considered a “hot” condition; therefore women are cautioned against ingesting “hot” foods, which might increase menstrual flow or produce cramping. Ingesting too much of either “hot” or “cold” foods can also be interpreted as a cause of illness.

Health care workers who are aware of this belief are better able to understand why some persons refuse to eat certain foods. It is often useful to discuss the diet with the family to determine their beliefs regarding food choices. It is possible to help families devise a diet that contains the necessary balance of basic food groups prescribed by the medical subculture while conforming to the beliefs of the ethnic subculture.

The “hot-cold” food classification may have adverse effects. For example, in some cultures newborn infants are often started on evaporated milk formulas. Evaporated milk is considered a “hot” food, whereas whole milk is viewed as a “cold” food. Infants tend to develop rashes, which are believed to be caused by “hot” foods; in such cases parents may decide to switch to whole milk. However, parents fear that it is dangerous to change too rapidly, so they often feed the child some type of neutralizing substance, which may create additional health problems. The nurse can help avoid such a problem by determining the family’s preference before discharge from the hospital and prescribing a formula that is agreeable to both the family and the practitioner.

Health Practices

Cultures have numerous similarities regarding prevention and treatment of illness. All cultures have some types of home remedies that they apply before seeking help from other persons. Within the ethnic community, folk healers who are endowed with the ability to “cure” maladies are sought for special situations and when home remedies are unsuccessful. The curandero (male) or curandera (female) of the Mexican-American community is believed to have healing powers that are a gift from God. The Asian consults an herbalist, knowledgeable in medicines, or perhaps an ethnic practitioner in Asian therapies, including acupuncture (insertion of needles), acupressure (application of pressure), and moxibustion (application of heat). Native Americans consult a variety of healers with specific skills and knowledge. Specialized medicine persons diagnose illness, provide nonsacred treatments (usually by way of massage and herbs), and care for souls. Other specialists perform services or effect cures through the use of spiritual means. Native Hawaiians consult kahunas and practice ho’oponopono to heal family imbalance or disputes.