CHAPTER 51 Alcohol and Substance Abuse

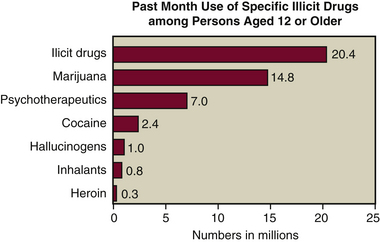

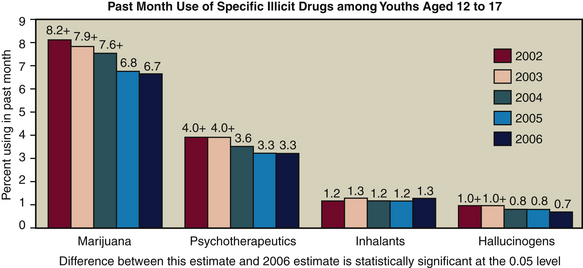

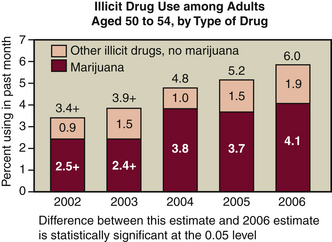

Substance abuse is a significant problem in U.S. society. In 2006 an estimated 20.4 million people were classified as having substance dependence or abuse in the previous year (Figure 51-1). The National Survey on Drug Use and Health asks participants if they have used illicit drugs in the past month. Although the use of marijuana, psychotherapeutics, inhalants, and hallucinogens among youth ages 12 to 17 declined from 14.4% in 2002 to 12.0% in 2006 (Figure 51-2), adults aged 50 to 59 showed an increase in illicit drug use from 3.4% in 2002 to 6.0% in 20061 (Figure 51-3). Substance abuse affects the individual, the family, and the community. Employers experience decreased worker productivity and increased insurance premiums. A significant number of deadly automobile accidents are caused by alcohol- or drug-impaired drivers. Child abuse and neglect are often directly related to the addiction of parents. Because addiction often results in criminal behavior to finance a drug habit, substance abusers are viewed as morally corrupt or weak personalities who willingly engage in self-destructive behaviors that affect themselves and everyone around them. Research has shown that addiction is a chronic, cyclic disease, yet unlike other diseases, there remains a social stigma attached to it.

Figure 51-1 Results of the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

(Prepared for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2007.)

Figure 51-2 Results of the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

(Prepared for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2007.)

Figure 51-3 Results of the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

(Prepared for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2007.)

Clients who are drug dependent, abuse substances, or are in treatment for substance abuse present the dental hygienist with a variety of important issues related to care. Such clients must be identified so they can be treated safely. To do this, dental hygienists must understand basic concepts associated with substance abuse, its cause, and associated medical treatment.

BASIC CONCEPTS OF ALCOHOL AND DRUG ABUSE

Alcohol (ethyl alcohol or ethanol) is a product manufactured by fermenting fruit, grains, or vegetables and distilling them to raise the alcohol content. The alcohol content of wine, beer, and spirits (hard liquor) differs. On average, beer contains 4.5% alcohol, wine 12.9%, and spirits 41.1%. A “standard drink” is defined as one that contains approximately ½ fluid ounce (12 g) of alcohol. This amount of alcohol is present in 12 fluid ounces of beer, 5 fluid ounces of wine, or 1½ fluid ounces of 80 proof distilled spirits. Binge drinking is defined as drinking five or more drinks on the same occasion at least once in 30 days.

Alcohol reduces anxiety and causes intoxication and sensory alterations. Alcohol enters the blood within 5 minutes of ingestion and remains in the bloodstream for 1 to 4 hours. The liver breaks down alcohol at the rate of one drink per hour. Blood alcohol concentration is measured in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). In most legal jurisdictions, blood alcohol concentrations of over 100 mg/dL (0.1%) are illegal.

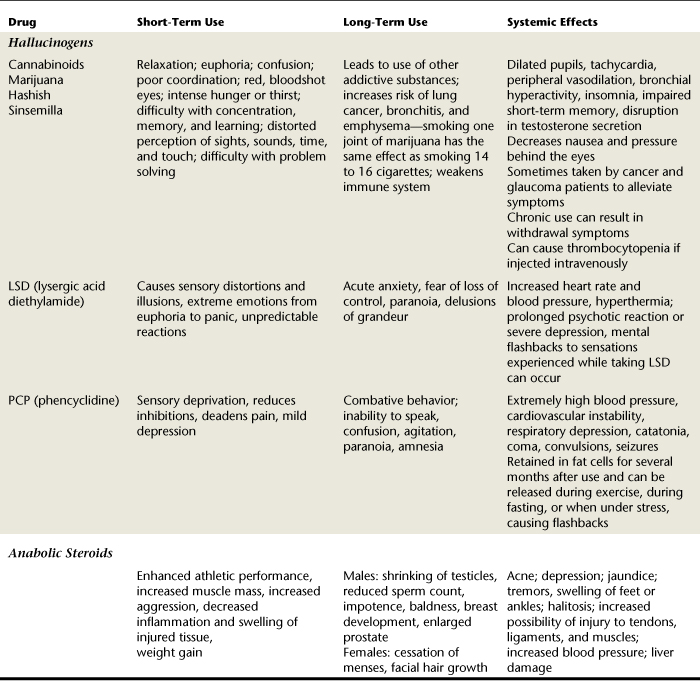

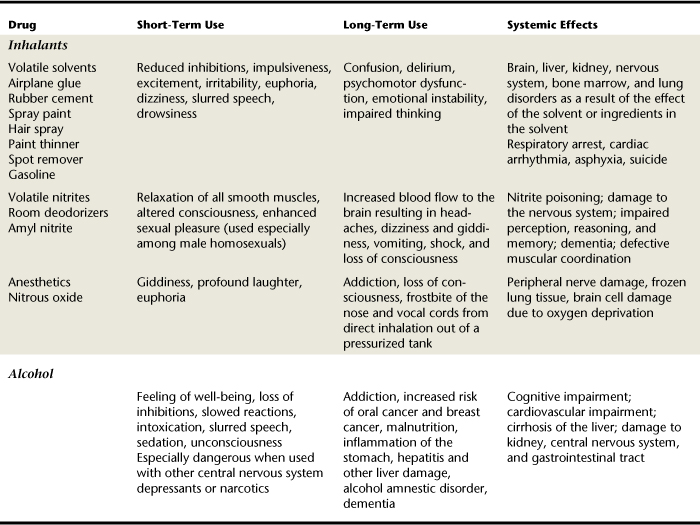

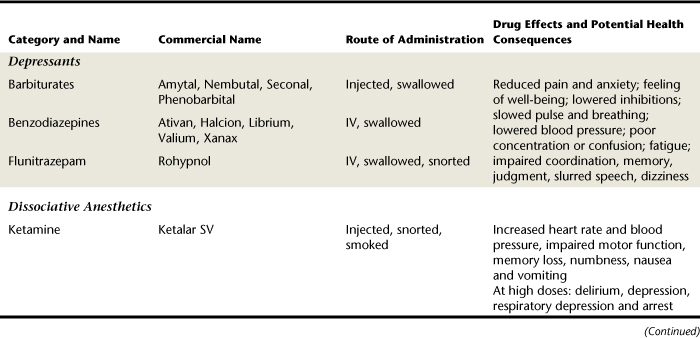

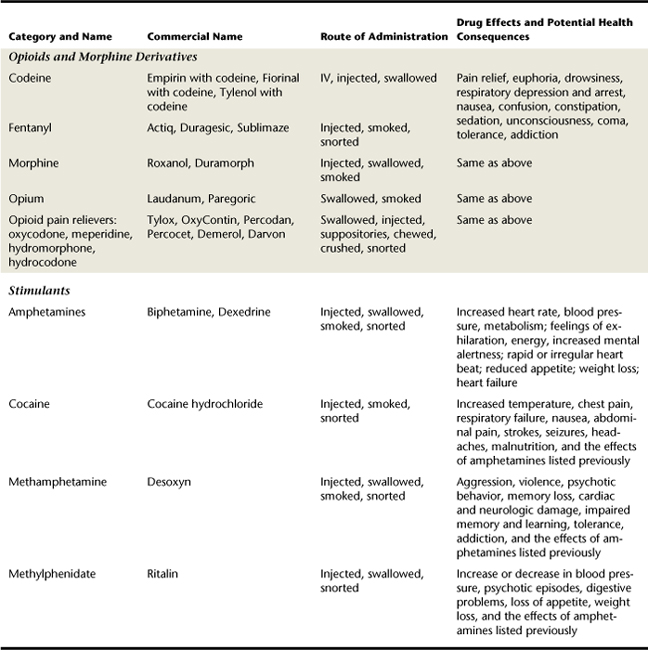

Drug abuse is the self-administration of a drug in a manner that differs from its accepted medical use. It includes experimental and recreational use of drugs, as well as addictive use (Table 51-1). Addiction is compulsive drug use despite adverse medical and social consequences.

| Classification Based on Use | Behavior | |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Abstainers (about one third of the population) | Never used drugs or alcohol |

| Type 2 | Social drinker or users (majority of population) | |

| Type 3 | Drug abusers | |

| Type 4 | Physically dependent addicts | |

| Type 5 | Psychologically dependent addicts | |

Adapted from Coombs RH: Drug-impaired professionals, Cambridge, Mass, 1997, Harvard University Press.

Those who compulsively abuse drugs continue to do so because they have developed a psychologic and physiologic dependence. Psychological dependence is rooted in the belief that the drug is needed to maintain a state of well-being. Physiologic dependence results from a biologic alteration in the user’s brain from consistent drug use. A person who has developed physiologic dependence on a drug will go through drug withdrawal once the drug is stopped. Withdrawal symptoms may include vomiting, diarrhea, rapid pulse, sweating, anxiety, convulsions, severe cramps, high blood pressure, and severe headaches. People will often continue using drugs because they fear experiencing withdrawal from the drug. Table 51-2 presents drug categories of abused substances and their effects on the body.

Another aspect of physical dependence is that a drug must be taken in constantly increased doses to achieve the same effects on the brain over time. Tolerance is the term used to describe this aspect of physical dependence. Nicotine, opiates, alcohol, psychedelics, central nervous system (CNS) stimulants, and sedative-hypnotics all require increased doses to establish the same “high” or euphoric feeling the user experienced with first use. If the drug dosage is not increased, the effects of the drug are diminished and withdrawal symptoms occur. Because of their effect on the brain, addictive drugs are also called psychoactive drugs. So-called “club drugs” have joined the list of abused substances in the past 10 years. MDMA (ecstasy), flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), and ketamine are used by teens and young adults who are a part of the nightclub, bar, and rave scene.2,3 They are generally low-cost drugs and readily available. Studies have shown that multidrug use is common among those who misuse stimulants. Girls and young women ages 16 to 25 are more likely to misuse diet pills or amphetamines, whereas boys and young men of the same age group were more likely to misuse methamphetamine and prescription stimulants such as Benzedrine, Ritalin, and Dexedrine4 (Table 51-3).

Stages of Change

The stages of change model, as described in Chapter 34 on treating nicotine addiction, describes the process of change an individual experiences when going from being a substance abuser to being an individual who is substance-free. The stages of change involve an individual’s readiness to quit abusing a particular substance. This model can be applied when counseling any substance abuser. By listening to the client and asking nonjudgmental questions about the client’s readiness to make a quit attempt, the dental hygienist can respond appropriately for the client’s current stage of change. For example, if a client admits to substance abuse but states he is not ready to stop, providing information on the benefits of stopping would be appropriate to help the client to continue to think about stopping. Asking questions like, “When will you know it is time to quit?” allows the client to think about an answer after the dental hygiene care visit and allows the client more control to make a decision to stop the substance abuse.

CAUSES OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Physiologic Factors

After a drug enters the body (Box 51-1), it is carried by the bloodstream to the central nervous system (the brain and spinal cord) within 10 to 15 seconds.

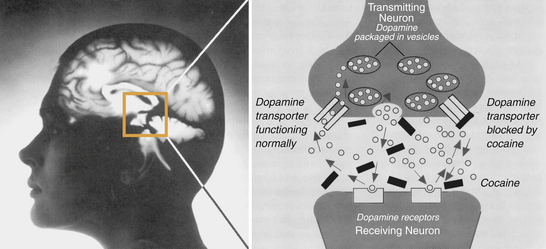

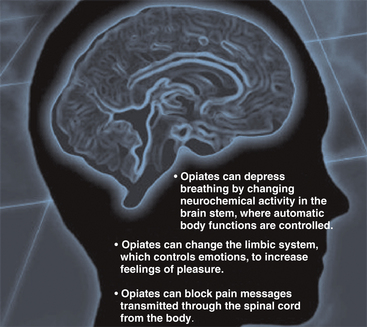

When a drug crosses the blood-brain barrier it can affect all parts of the body by interfering with the information sent to the CNS by the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The ANS controls involuntary functions such as circulation, digestion, and respiration and helps the body to establish a stable internal environment. The PNS transmits messages between the external environment and the CNS. The role of the CNS is that of computer and switchboard. As the CNS receives messages from the ANS and PNS, it analyzes those messages and sends a response to the correct body system—muscular, skeletal, circulatory, nervous, respiratory, digestive, excretory, endocrine, or reproductive—to react to the stimuli. The CNS is also responsible for reasoning and making judgments. Psychoactive drugs alter the information sent to the brain and disrupt the messages sent back to the body (Figure 51-4). They also disrupt the ability to think and reason.

Figure 51-4 National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Report Series—heroin abuse and addiction.

(From National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006.)

Neurotransmitters

The three main components of a neuron (a nerve cell) are dendrites, the cell body, and axons. The dendrites receive signals from other neurons, the cell body nourishes the neuron and keeps it alive, and the axons carry the message from the dendrites and cell body to the terminals, which relay the message to the dendrites of the next neuron. Between the neurons lies the synaptic gap, the space between the terminal that is sending the message and the dendrite that is receiving the message. This “jump” between neurons is accomplished through biochemicals called neurotransmitters that transmit the message from one neuron to the receptors on another. Dopamine, endorphin, enkephalin, serotonin, substance P, epinephrine, and acetylcholine are examples of neurotransmitters. The specific message that is being sent will determine the neurotransmitter that is released from the neuron. For example, substance P is released from neurons if “pain” is the message being transmitted, and dopamine is released if “pleasure” is the message being transmitted.

Psychoactive drugs disrupt the normal functioning of the neurotransmitters. Sometimes this is a desirable effect. CNS depressants inhibit the release of substance P, thereby dulling and weakening the pain signal. This effect is desirable if morphine is prescribed by a physician to alleviate pain in a person with a terminal illness. The illegal CNS depressant heroin also attaches itself to certain receptor sites in the emotional center of the brain and induces a sensation of pleasure or reward; however, it also attaches itself to the area of the brain that controls respiration and can slow it down to a dangerous level. CNS stimulants such as cocaine force the release of large amounts of neurotransmitters such as epinephrine and dopamine, which can create, stimulate, and exaggerate messages to and from the CNS (Figure 51-5). Psychedelic drugs will confuse neurotransmitters by exaggerating and distorting messages and by creating visual and auditory images in the brain. New studies have shown that brain images are altered when methamphetamine, alcohol, nicotine, and cocaine are present in the body. Women reported consistently higher scores, on a scale from 0 to 100, than men when asked to rate a “feel good” sensation after taking cocaine. All addictive drugs deplete the brain’s receptors for dopamine.5

Genetic Factors

Endorphin and enkephalin neurotransmitters have an opiate-like effect on the brain, causing the individual to have a feeling of well-being. People who are born with the inability to produce sufficient quantities of endorphin and enkephalin have a genetic predisposition for opiate and alcohol addiction.6 These are often people who suffer from depression and look for artificial means to alleviate their moods.

Researchers have been unable, as yet, to identify a specific gene responsible for drug abuse, but it is believed that several modified genes may contribute to addiction. Genes that interfere with serotonin metabolism and affect the serotonin-dopamine balance (neurotransmitters) in the brain have been implicated in a wide variety of psychiatric disorders. Such disorders include alcoholism, drug addiction, depression, suicide, aggressive behaviors, antisocial borderline personality disorder, phobias, panic attacks, eating disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).6

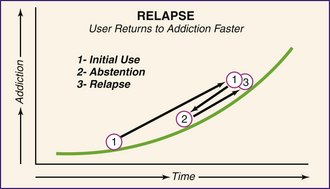

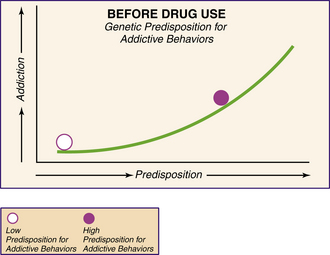

Addiction Curve6

Because individuals are born with some genetic (inherited) sensitivity to specific drugs, those with low genetic predisposition for addictive behaviors will take longer to become addicted or to climb the curve to addiction than those born with a high genetic predisposition. The individual with high predisposition starts at a point closer to addiction on the curve (Figure 51-6).

Figure 51-6 Before drug use, genetic predisposition for addictive behaviors.

(Adapted from Inaba DS, Cohn WE: Uppers, downers, all arounders, Ashland, Ore, 1990, Cinemed.)

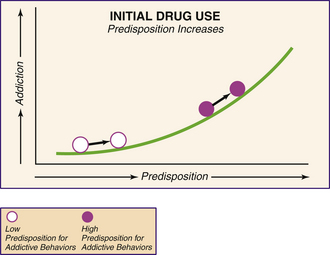

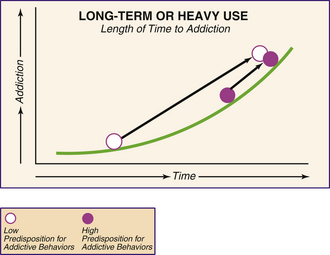

Drugs are used first experimentally, then socially and habitually until addiction is reached. When drugs are first used, the predisposition for addictive behaviors increases (Figure 51-7). Those individuals with a low inherited predisposition for addictive behaviors would have to use drugs over a much longer period of time to become addicted than would those with a high inherited predisposition. It may take people with a low predisposition 3 or 4 years of long-term or heavy use to reach the same level of addiction people with a high predisposition would reach in 2 or 3 months. Predisposition to addiction in the latter group of people is due to the deficiency that is already present in their brain chemistry (Figure 51-8).

Figure 51-7 Initial drug use, predisposition increases.

(Adapted from Inaba DS, Cohn WE: Uppers, downers, all arounders, Ashland, Ore, 1990, Cinemed.)

Figure 51-8 Long-term or heavy use and length of time to addiction.

(Adapted from Inaba DS, Cohn WE: Uppers, downers, all arounders, Ashland, Ore, 1990, Cinemed.)

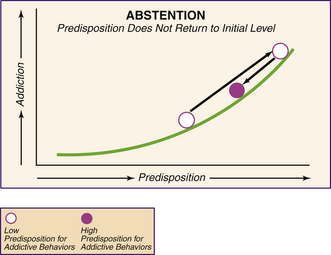

If individuals stop taking (abstain from) drugs, will their brain chemistry return to normal? Evidence suggests that “neurotransmitters may rebound back to normal levels in those with short-term, noninherited disruption, but not so with long-term, inherited imbalance”6 (Figure 51-9).

Figure 51-9 Abstention; predisposition does not return to initial level.

(Adapted from Inaba DS, Cohn WE: Uppers, downers, all arounders, Ashland, Ore, 1990, Cinemed.)

When the sensitivity does not return to normal, the brain is imprinted and remembers the drug-using habits. As a result, the next time the individual relapses and starts to use the drug again; it takes much less time to reach a level of addiction (Figure 51-10).

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (see Chapter 53)

A pregnant woman with an active alcohol addiction is at risk for delivering a child with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). See Box 51-2 for FAS characteristics. Intellectual and developmental disability, physical impairments, and infant failure to thrive can result.

Environmental Factors

Although substance abuse prevention programs for youth are found in schools, in the media, and in the community, they are insufficient by themselves. Without parental supervision, consistent discipline, and a loving family relationship, community programs are not as effective. A 2006 study found that nearly one in 10 high school seniors abuses a prescription pain reliever each year and that 16% of eighth, tenth, and twelfth graders took cough and cold medications containing dextromethorphan (DXM) to get “high.”7 This abuse of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines has caused many drug manufacturers to change the formulas of their cough and cold products to eliminate DXM. Many pharmacies have moved products containing DXM off of store shelves. They must be obtained directly from the pharmacist and are out of the easy reach of customers. Stores have also limited the number of DXM-containing products that can be purchased at one time.

Families play a very important role in determining how children handle the temptation to use alcohol, cigarettes, and illegal drugs. Substance abuse by one family member affects each of the others in some way. The individual family members feel many of the emotions experienced by the addict, although they tend to suppress their feelings. Often their confidence and self-esteem are diminished and anxieties and members of substance abusers experience depression, and one third become chemically dependent themselves (Box 51-3).

MEDICAL TREATMENT FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Emergency Treatment

An immediate need for medical care is present when the abuser takes an overdose of a substance and has a life-threatening medical condition that must be treated. Acute alcohol poisoning associated with binge drinking is a condition that has appeared with increasing regularity on college campuses and requires emergency treatment. Symptoms of alcohol poisoning include the following:

Alcohol poisoning is a medical emergency, and 911 should be called. While waiting for the emergency medical service to arrive, the individual should not be given anything to eat or drink, should be turned on his or her side, and should have breathing and vital signs monitored. In the hospital emergency room the treatment priority is to stabilize the client, followed by detoxification by behavioral and/or pharmacologic treatment, which may take several weeks. This treatment often is performed on an in-patient basis to limit access to alcohol or drugs. Clients who have an existing psychiatric problem along with substance abuse are best treated at long-term drug treatment facilities.

Behavioral Treatment

It is often stated that substance abusers must reach “bottom” in their lives before they willingly seek help. Reaching bottom often means that they are unemployed and lack emotional support from friends and family. The most effective treatments for substance abuse occur when the abuser is motivated to seek medical intervention, behavioral changes, and social reinforcement, although treatment does not need to be voluntary to be effective. Court-appointed treatment and sanctions or enticements provided by family or employers can also result in effective treatment. No single treatment is appropriate for all individuals. Effective treatment attends to the multiple needs of the individual including medical, psychologic, social, vocational, and legal issues that confront the substance abuser. Remaining in treatment for an adequate amount of time is critical to success. Most patients realize significant improvement by the end of 3 months in treatment. Individual and/or group counseling and other behavioral therapies are needed to help the patient develop skills to resist drug use. Recovery from drug addiction can be a long-term process and frequently requires multiple treatments. Participation in self-help support programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous during and after treatment often helps maintain abstinence.8

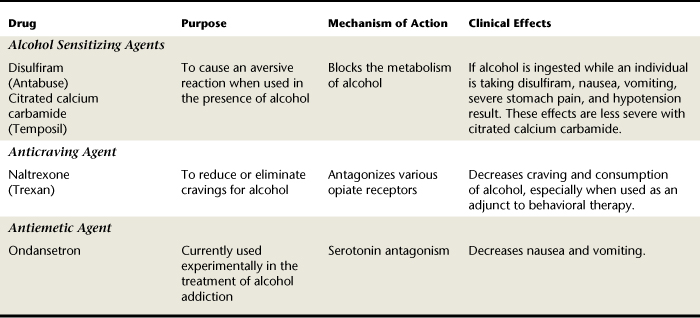

Pharmacologic Treatment

Treatment for addiction may involve drug therapy (Table 51-4). Drugs usually prescribed to treat the symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders are often used to treat clients with addictive behavior disorders.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE DENTAL HYGIENE PROCESS OF CARE

Assessment

The problem of abuse of alcohol, prescribed medications, or illegal drugs affects all socioeconomic groups. Only about 10% of clients who abuse drugs, however, are identified by healthcare providers. Several visits over time for dental hygiene care may reveal behaviors that can be confirmed by a well-focused health history and a thorough extraoral and intraoral examination.

Health History

Chemically dependent clients must be identified so they can be treated safely. Many will “premedicate” with their drug of choice before coming to a dental appointment. In the health history interview the dental hygienist identifies all current medications the client is taking to avoid possible drug interactions between a prescribed or an abused substance and drugs offered in the oral health setting. Such interactions can pose a life-threatening situation for the client.

The need for prophylactic antibiotic premedication must be considered for the following reasons when treating a client with a history of intravenous drug use:

Damage to the tricuspid valve between the right atrium and ventricle is often associated with substance abuse.

Damage to the tricuspid valve between the right atrium and ventricle is often associated with substance abuse. Intravenous drug use can result in endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus found on nonsterile needles.

Intravenous drug use can result in endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus found on nonsterile needles.Consequently, all clients with a history of intravenous drug abuse should be evaluated by their physician before dental or dental hygiene care to determine if any of these conditions exists, indicating the need for antibiotic premedication (see Chapter 10).

Additional medical conditions experienced by chemically dependent clients are influenced by the specific substances being used and how they enter the body. For example, clients with a history of intravenous drug use have a higher incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and hepatitis B, C, and D from sharing needles. Long-term use of alcohol can result in liver damage. Damage to the heart, kidneys, pancreas, and reproductive system and permanent brain damage and a lack of muscle coordination can result from years of alcohol abuse. The impact of drug addiction can include cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, HIV infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), hepatitis, and lung disease, especially after prolonged use.9

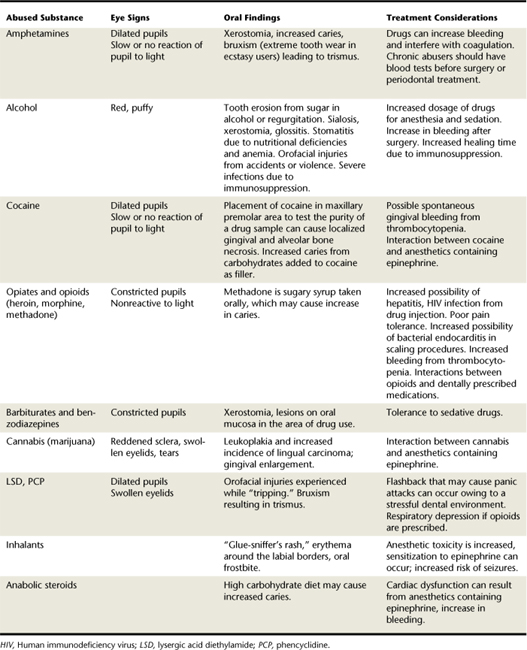

Questions about substances used and routes of administration should appear on dental office health history forms. When reviewing the client’s responses and when interacting with the client, the dental hygienist looks for signs of substance abuse. If the dental hygienist suspects the client may be dependent on a substance, that information should be recorded in the client’s dental record (Box 51-4.) Specific objective observations, client behavior, and assessment findings such as pupil changes or needle marks should be recorded using objective terminology.

Clients are often reluctant to reveal alcohol or drug use because of the social stigma associated with substance abuse. Also, many substance abusers are in denial and will not admit to any type of dependence when asked. The astute dental hygienist recognizes signs and symptoms of dependence and discusses the possibility of a substance abuse problem with the client in a nonjudgmental manner. (See Table 51-5 for drug categories and street names of abused substances.) Recognition of a drug abuse problem by a healthcare professional may prompt the abuser to seek help. It is essential that clients understand that the reason for obtaining information is to protect them from health risks and that all information will remain confidential.

TABLE 51-5 Drug Categories and Street Names

| Drug Category | Available as | Street Names |

|---|---|---|

| CNS Stimulants | ||

| Amphetamines | ||

| Caffeine | ||

| Cocaine (hydrochloride) | White powder (snorted or dissolved in water and injected) | C, coke, Charlie, snow, toot, joy powder, Cadillac, gold dust |

| Freebase cocaine | White crystalline powder diluted with talc or cornstarch and/or sugar (smoked) | Flake, blow, crack, rock, freebase |

| Nicotine | Cigarettes, cigars, chewing tobacco, snuff | Cancer stick, stogie, butt, toke, dip, chew |

| CNS Depressants | ||

| Opiates from Opium Poppy Extracts | ||

| Opium | Laudanum, Paregoric | |

| Codeine | Number 3s | |

| Morphine | By prescription | M, white stuff, morph, Miss Emma |

| Heroin | H, smack, horse, junk, Harry, chip, hard goods, China white | |

| Hydromorphone | Dilaudid | Dillies |

| Hydrocodone | Vicodin (often prescribed for dental pain) | |

| Oxycodone | Percodan | Percs |

| Synthetic Opiates (Opioids) | ||

| Sedatives and Hypnotics | ||

| Barbiturates | ||

| Benzodiazepines | ||

| Nonbarbiturate Sedatives and Hypnotics | ||

| Hallucinogens | ||

| Cannabinoids | ||

| Marijuana | Flowers and leaves of marijuana plant; can be eaten or smoked | Grass, pot, weed, hemp, Mary Jane, reefer, roach, Acapulco gold |

| Sinsemilla | Marijuana plants with increased THC | Sins, skunk weed |

| Hashish | Concentrated resin from marijuana plant | Hash |

| Hash oil | Extracted from marijuana plant and added to foods | Hash |

| Phencyclidine (PCP) | Manufactured illegally (can be smoked, swallowed, or injected) | Angel dust, ice, peep, ozone, Shermans, KJ |

| Ketamine | Crystals or powder that is smoked, snorted, or swallowed | Super-K |

| Inhalants | ||

| Volatile Solvents | ||

| Adhesives | Airplane glue, rubber, cement, polyvinylchloride cement | General terms: sniffing or snorting |

| Aerosols | Spray paint, hair spray, deodorant, air freshener, asthma spray | |

| Solvents and gases | Nail polish remover, paint remover, paint thinner, fuel gas, cigarette lighter fluid, gasoline, typing correction fluid | |

| Cleaning agents | Dry cleaning fluid, spot remover, degreaser | |

| Dessert topping sprays | Whipped cream | |

| Nitrates and Anesthetics | ||

| Nitrite room deodorizers | ||

| Nitrous oxide anesthesia | Available as a gas | Poppers, rush, whippets (balloons or plastic bags filled with nitrous oxide) |

| Anabolic Steroids and Hormones | ||

| Male hormones | Testosterone, Dianabol, stanozolol | General terms: roids, doping, stacking, bulking up |

| Adrenocortical steroids | Cortisone, prednisone, Decadron | |

| Clomiphene | ||

CNS, Central nervous system; OTC, over the counter; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol.

When abuse is suspected, it is recommended that the dental hygienist ask the following questions:

Have you ever used or had a drink first thing in the morning as an eye opener to steady your nerves or to feel normal?

Have you ever used or had a drink first thing in the morning as an eye opener to steady your nerves or to feel normal?If the client answers “yes” to two or more of these questions, then the dental hygienist should strongly suspect abuse and consider how to motivate the client to seek treatment. The oral healthcare setting should have a list of community resources available as a reference for the client. Brochures about specific programs can be provided, or the client can be given the telephone number of the National Council on Alcohol and Drug Dependence, which offers general information. Identifying dental hygiene clients who are chemically dependent is important; however, substance abuse treatment is not within the scope of dental hygiene practice. It is helpful if dental offices develop a simple protocol for referral of clients with substance abuse problems.

It is necessary to determine if the client “self-medicated” for the dental appointment. If the client took drugs or alcohol before the appointment, then the care plan for that day may need to be modified or canceled to avoid any drug interactions and/or drug-associated behavioral problems.

Extraoral Examination

The general appearance of clients can alert the dental hygienist to the possibility of substance abuse. Do they look substantially older than their stated age, have a disheveled appearance, have poor personal hygiene, insist on wearing sunglasses, and wear long sleeves even in hot weather (perhaps to cover needle marks)? Can you smell alcohol or other odors on the breath? Do they appear to be lethargic or intoxicated without the accompanying odor of alcohol? Do they experience tremors? Look at clients’ eyes for signs of substance abuse (see Box 51-4).

Needle marks in the antecubital fossae and forearms or bruises and increased pigmentation over veins caused by multiple injections, observed during the taking of a blood pressure reading, may indicate illicit drug use. Skin abscesses can be caused by subcutaneous “popping” of heroin. Crack abusers will often have burns and scars on the thumb of the dominant hand from repeated use of a disposable lighter. Multiple healed and healing burns or abrasions may be the result of physical trauma experienced while the client was under the influence of alcohol or drugs. Snorting or inhaling substances can burn nasal passages, cause nosebleeds, and significantly damage nasal structures. Often, clients continually sniff their noses and use handkerchiefs or tissues.

The client’s behavior and speech should be watched for signs of confusion, disorientation, lethargy, lack of concentration, or memory impairment. Extreme depression or agitation may indicate a drug overdose.

Tremors of the hands, tongue, and eyelids may be signs of alcohol withdrawal. Other extraoral signs of alcohol abuse include the following:

Intraoral Examination(Table 51-6)

Placement of drugs in the vestibule or under the tongue can cause localized tissue necrosis. Gingival lesions may be caused by cocaine placement. Alcohol and drug abusers often crave sweets. Consequently, large dark areas of buccal cervical caries from ingesting large quantities of carbohydrates may be present. Methadone abusers develop “meth mouth” (Figure 51-11), a condition that results in rampant caries and evidence of advanced periodontal disease. Other oral manifestations associated with substance abuse include oral candidiasis as a result of immunosuppression, and glossodynia (pain in the tongue) from malnutrition and immunosuppression because of a secondary addiction to alcohol. Cocaine users tend to have severe bruxism, causing flat cuspal planes on premolars and molars. Because the substance abuser’s body is being taxed by drug use, tissue healing is affected (Box 51-5).

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis and Care Planning

Substance abuse must be addressed in care planning. People who are deeply immersed in drug abuse will probably seek dental care only when they are in severe pain. Because the pain sensation can be diminished by the use of drugs, the dental problem is usually in an advanced state. Substance-abusing clients may request the use of nitrous oxide sedation for treatment and specific medication for pain. As previously discussed, it is important that oral care professionals have knowledge of the type and amount of drugs clients have taken before planning any pain control or other care.

Clients in recovery programs, however, may seek long-neglected dental treatment as part of their attempt to achieve total body health. It is under these circumstances that the dental hygienist will most probably be providing care. Recovering addicts may be extremely cautious or anxious about taking any type of medication, making it difficult to control pain during scaling and root planing procedures. Some chemically dependent clients also may experience a tolerance to sedatives and analgesics. For clients recovering from substance abuse, pain control should be coordinated with the primary care physician. In addition, chemically dependent clients can experience emotional anxiety or instability and may be able to tolerate only short appointments. For this reason the use of multiple short (20-minute) appointments may be necessary.

After a thorough assessment and consultation with the client’s physician, if indicated, complete diagnostic statements are formulated by the dental hygienist based on identified human need deficits. Once the diagnostic statements are complete, client goals are set. Care planning priorities include setting realistic goals with the client to improve oral self-care and to enable the client to undergo periodontal scaling and root planing with a minimum of discomfort. Also, because malnutrition is clearly associated with substance abuse, dietary analysis and nutritional counseling should be planned. With permission of clients, consultation with their physician and counselors may aid the dental hygienist in planning effective care.

Implementation

Because good oral health and a pleasant smile add to an individual’s self-esteem, receiving necessary dental hygiene care may have a significant positive impact on recovery from substance abuse. A discussion concerning referral for treatment of the substance abuse should be initiated as soon as possible.

Appointments

Chemically dependent clients can experience emotional instability or take little responsibility for their behavior. As a result, they may not keep scheduled appointments. If the client arrives too late for an appointment, the appointment should be canceled. If the client fails to come to an appointment, all remaining appointments should be canceled. Failure to keep appointments should not be reinforced as acceptable behavior. Because of potential unreliability and to provide additional incentive to show up for care, payment should be received in advance of treatment. Aesthetic restorations should be treated last to ensure that clients show up for all necessary treatment. It is unethical to abandon clients once they are accepted for treatment in a dental practice. If a client continually fails to keep scheduled treatment appointments, the dental office may dismiss the client from the practice by written notification. Legal guidelines dictate that the client must be assured, in writing, that emergency dental treatment will be provided for a length of time sufficient to obtain a new dentist of record, usually 30 days or more from receipt of the dismissal letter. All dental records must be forwarded to the new dentist, along with notification of what services are still needed, when the client makes that request in writing.

Pain and Anxiety Control

Adequate pain control is a necessity in the recovering chemically dependent client because unrelieved pain can be a relapse trigger. For postoperative pain, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended because all other pain medications are potentially addictive. If the dentist feels that narcotic analgesics or sedative hypnotics for postoperative pain are indicated, substance-abusing clients require a higher dose than non–substance-abusing clients, and a limited number of doses should be prescribed. Analgesic depressants are not contraindicated unless other illicit depressants are being taken by the patient at the same time. People with methamphetamine addiction rarely seek dental care when under the influence of the drug but may seek care between methamphetamine binges.10 Anesthesia and pain control may be difficult to achieve for heroin-addicted clients who are in a methadone treatment program, because they have developed a tolerance to the analgesic and euphoric effects of their daily methadone dose. Consultation with the client’s physician is necessary to determine the best method to alleviate client discomfort.

Control of client anxiety also can help alleviate the client’s perception of pain. Pain perception has both physical and psychological components. If the client trusts the clinician, emotional distress can be minimized, reducing the perception of pain. A dental hygienist with excellent communication skills and empathy can help dispel the client’s anxiety. See Table 51-6 for other treatment considerations.

Some substance-abusing clients may see dental treatment as an opportunity to obtain prescriptions for abused substances. Consequently they often will exaggerate their response to pain in an effort to obtain a prescription for a strong pain control medication. Prescription pads should be kept out of sight and in a safe place so that they are not accessible to clients. Pain medication in the dental office should be locked in a place unknown to clients. Drug-seeking clients often call the dental office, complain that they are in severe pain, and request that a prescription for pain medication be given to them without making an appointment with the doctor. Dental offices should maintain a policy of prescribing drugs only after the client has been seen by the dentist.

Dental Hygiene Care

Because short (20 minute) appointments are suggested, the dental hygienist may be able to complete only limited treatment at each appointment. If there is a need for prophylactic antibiotic premedication, the dental hygienist ensures that the client has taken premedication as directed. General supragingival and subgingival debridement, which will enable the client to initiate adequate homecare, may be all that the client will tolerate in a short appointment. Such treatment would allow the dentist to place needed restorations in a state of improved gingival health. This improved tissue response is especially important when cervical restorations are placed, because inflamed gingival margins can interfere with the placement of restorative materials.

The client’s response to the initial scaling visit will dictate further appointment planning. The client may be able to tolerate quadrant scaling and root planing so that optimum treatment for periodontal disease may be provided. Confirmation from the client’s physician that there is no immunosuppression or kidney or liver damage should be sought before aggressive nonsurgical or surgical periodontal therapy is undertaken. The use of an ultrasonic scaling instrument and an alcohol-free antimicrobial lavage is indicated to reduce the incidence of a transient bacteremia.

It is best to postpone definitive scaling and root planing until a later time if the client is unable or unwilling to comply with treatment. In this case a short, 2- or 3-month continued-care interval is indicated. Once clients have progressed further with recovery from addiction, they may be more tolerant of dental hygiene care.

Oral Health Instruction

Lack of oral hygiene is common among substance abusers. Oral health instruction should begin with basic toothbrushing instructions and encouragement to practice toothbrushing daily. Once daily toothbrushing techniques have been mastered or a power toothbrush has been recommended and demonstrated, interdental oral physiotherapy aids can be introduced. The choice of aid will depend on the client’s physical and mental capabilities and the type of embrasures present (see Chapters 21 and 22). If the client is incapable of the fine motor skills necessary to manipulate dental floss, other aids should be suggested. Interdental wooden stimulators, interproximal brushes, or a power floss aid may be easier for the client to use. If clients are frustrated by an inability to master a technique, they probably will do nothing. The client in addiction recovery has already been required to make numerous behavioral changes and may see a complex oral hygiene regimen as an additional burden.

Suggesting use of a fluoride rinse is appropriate, especially if the client has a moderate to high caries risk (see Chapters 16 and 31). Use of fluoride therapy is also important for heroin addicts enrolled in a methadone program, because the daily methadone dose is administered as a sugary syrup. Antimicrobial rinses to control gingivitis may also be recommended. For alcoholics, it is important to recommend products that do not contain alcohol to avoid supporting their addiction and contributing to the negative health effects they experience from their alcohol use. Even very small amounts of alcohol ingested by a client taking disulfiram or similar alcohol-sensitizing drugs can cause an emergency. Therefore nonalcoholic fluoride mouth rinses (e.g., ACT, FluoriGard) and nonalcoholic antimicrobial mouth rinses (e.g., Biotene, Crest Pro Health) are recommended for homecare and for preprocedural rinses. Xerostomia may be a result of antidepressant medications prescribed for the client. Suggest that the client sip water frequently during the day or use xylitol-containing gums or mints to reduce the effects of dry mouth.

The dental hygienist also suggests that the client eat a well-balanced diet and limit cariogenic foods to encourage both oral and general health. Positive reinforcement and encouragement should be given to clients for any improvement in their oral hygiene.

Evaluation

The outcomes of dental hygiene care can serve as positive reinforcement for a healthier lifestyle for those clients in recovery. If evaluation of dental hygiene care occurs 6 to 8 weeks after initial debridement, clients may be further along in their recovery and may be more receptive to additional periodontal therapy, if needed. For those clients who are not in recovery, the evaluation of dental hygiene care provides another opportunity to encourage clients to seek help for their substance abuse. The initial recall or continued-care interval should be 3 months after treatment. This is especially important if there was extensive periodontal therapy complicated by immunosuppression.

DENTAL PROFESSIONALS AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Alcohol and drug abuse are widespread in American culture, and dental professionals are not exempt from addiction. In fact, the prevalence of drug and alcohol abuse among professionals may be the same as or higher than in the general population.11 Dental personnel can self-prescribe medications; they have opportunity for easy access to abuse drugs. Many states have begun monitoring prescription writing habits of dentists.

Why Professionals Are at Risk for Chemical Dependence

Healthcare professionals are usually required to have high academic grades to be admitted to a professional educational program. Once accepted, the professional education requires hours of instruction to reach competence. Students enrolled in healthcare educational programs are usually competitive, overworked, narrowly specialized, self-sacrificing, and grade conscious.

Dental and dental hygiene students have their work continually criticized by faculty. Trying to prove one’s competence can easily lead to little sleep, an unbalanced and emotionally unrewarding lifestyle, physical and emotional exhaustion, stress and anxiety, irritability, and depression.11 Completion of a professional program often requires students to become “self-denying,” and their personal lives become of secondary importance to their education. This situation can lead to emotional conflicts within themselves and their families. Often students will use stimulants to enhance their performance at school or alcohol on the weekend to relieve stress. This cycle often continues once the student has become a practicing professional.

Although taught to recognize symptoms of chemical dependence in clients, health professionals rarely recognize addiction in themselves. Most are convinced that they are in control of their substance abuse and can stop whenever they choose. Chemical dependence may be the underlying cause of licensure suspension or malpractice (Box 51-6).

BOX 51-6 American Dental Association (ADA) Policy Statement on Chemical Dependency

Many state dental associations sponsor educational programs and workshops on addiction within the profession. Diversion from the court system to a treatment program is available to addicted professionals unless they have engaged in unethical treatment by causing harm to clients or violating major criminal laws. Health and well-being committees of state dental associations help colleagues with addiction problems. Confidentiality is ensured, and referrals may be made anonymously. The committees may contract for services through the state medical society and provide appropriate referrals, posttreatment follow-up, monitoring, and advocacy.

Many professionals decide that it is time to stop drug abuse when they are faced with the loss of their professional license. Some seek help through residential or outpatient formal recovery programs, and others seek help through self-help programs. Dental support groups at Caduceus meetings, which are modeled on the principles of Alcoholics Anonymous, may also provide psychologic support for professionals in recovery.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Discuss the risk of negative interactions between local anesthetics or nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia and the abused substance.

Discuss the risk of negative interactions between local anesthetics or nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia and the abused substance. Describe how the abused substance affects oral and general health. Inform clients that antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene care may be necessary to prevent infective endocarditis or to manage an immunocompromised status.

Describe how the abused substance affects oral and general health. Inform clients that antibiotic premedication before dental hygiene care may be necessary to prevent infective endocarditis or to manage an immunocompromised status. Stress the need for regular professional care, good oral hygiene, and good nutrition. Point out oral manifestations of substance abuse and malnutrition in the client’s own mouth.

Stress the need for regular professional care, good oral hygiene, and good nutrition. Point out oral manifestations of substance abuse and malnutrition in the client’s own mouth. Positively reinforce and encourage clients for improvements in their oral self-care and movement through the stages of change.

Positively reinforce and encourage clients for improvements in their oral self-care and movement through the stages of change.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Client behavior, assessment findings, professional recommendations, referrals, and treatment should be recorded in the client’s permanent record. Personal opinions and judgmental statements are inappropriate.

Client behavior, assessment findings, professional recommendations, referrals, and treatment should be recorded in the client’s permanent record. Personal opinions and judgmental statements are inappropriate. Some states have parental notification laws that direct healthcare professionals to reveal knowledge of any medical or psychologic conditions found during an examination to a minor’s parent or legal guardian.10 Knowledge of the statutes in the legal jurisdiction is important so that confidential information about minors is managed correctly.

Some states have parental notification laws that direct healthcare professionals to reveal knowledge of any medical or psychologic conditions found during an examination to a minor’s parent or legal guardian.10 Knowledge of the statutes in the legal jurisdiction is important so that confidential information about minors is managed correctly. Dentists should never write a prescription for a pain medication without knowing the client’s history or without first examining the client.

Dentists should never write a prescription for a pain medication without knowing the client’s history or without first examining the client. With approval from clients being treated for substance abuse, contact their physician and/or mental health professional when planning care.

With approval from clients being treated for substance abuse, contact their physician and/or mental health professional when planning care. Do not render treatment that may cause an interaction between an abused substance and dental anesthetics or other drugs offered as part of healthcare.

Do not render treatment that may cause an interaction between an abused substance and dental anesthetics or other drugs offered as part of healthcare.KEY CONCEPTS

Substance abuse is a chronic, cyclic disease that affects 20.4 million people in U.S. society, including oral healthcare professionals.

Substance abuse is a chronic, cyclic disease that affects 20.4 million people in U.S. society, including oral healthcare professionals. Substance addiction is a compulsive use of a substance despite adverse medical and social consequences.

Substance addiction is a compulsive use of a substance despite adverse medical and social consequences. Psychologic and physical dependence on drugs and genetic predisposition are the reasons people continue substance abuse.

Psychologic and physical dependence on drugs and genetic predisposition are the reasons people continue substance abuse. Tolerance to alcohol and drugs creates the need for continued increases in the amounts used to gain the same effect.

Tolerance to alcohol and drugs creates the need for continued increases in the amounts used to gain the same effect. Dental hygienists need to identify chemically dependent clients for the following reasons:

Dental hygienists need to identify chemically dependent clients for the following reasons:

To avoid drug interactions between drugs offered at the dental office, such as local anesthetics or nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia, and abused substances

To avoid drug interactions between drugs offered at the dental office, such as local anesthetics or nitrous oxide–oxygen analgesia, and abused substances Culture, ethnicity, poverty, behavioral problems, child abuse, peer rejection, and environment can be risk factors for substance abuse.

Culture, ethnicity, poverty, behavioral problems, child abuse, peer rejection, and environment can be risk factors for substance abuse. Drugs affect the transmission of messages among the central, autonomic, and peripheral nervous systems by interfering with neurotransmission. Key neurotransmitters include dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins.

Drugs affect the transmission of messages among the central, autonomic, and peripheral nervous systems by interfering with neurotransmission. Key neurotransmitters include dopamine, serotonin, and endorphins. Women have specific issues in alcohol and other substance abuse during pregnancy because it can affect the health of the fetus.

Women have specific issues in alcohol and other substance abuse during pregnancy because it can affect the health of the fetus. Characteristics of children with fetal alcohol syndrome include poor motor coordination, learning disabilities, hyperactivity, sensory impairment, irritability, microcephaly, abnormal facial features, growth retardation, and mental retardation.

Characteristics of children with fetal alcohol syndrome include poor motor coordination, learning disabilities, hyperactivity, sensory impairment, irritability, microcephaly, abnormal facial features, growth retardation, and mental retardation. Modification of addictive behavior goes through stages of change, which may have to be repeated before total abstinence is achieved.

Modification of addictive behavior goes through stages of change, which may have to be repeated before total abstinence is achieved.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

CASE STUDY 1

Profile: Mr. Y., age 24, was scheduled for dental hygiene care. This is his first dental appointment for preventive care. His last dental appointment was for extraction of teeth 2 and 15. He has a history of asthma, smokes one pack of cigarettes a day, and is currently taking 5 mg of prednisone twice a day. He reports that he took part in a drug and alcohol rehabilitation program 1 year ago. He states that he has seen several television programs about “germs” in dental unit water lines and is worried about being exposed to disease. His girlfriend has suggested he “do something about his teeth.” His chief complaint is that his teeth are discolored, sensitive to cold, and “soft” and decay easily; he also states that his mouth feels dry. Intraorally, his clinical gingival attachment loss ranges from 3 to 7 mm with bleeding on probing in the mandibular anterior teeth. His gingivae are pale, except on the mandibular anterior, where the gingival margins are magenta. The tissues are edematous and have rolled gingival margins. The tissue consistency is spongy, and the interdental papillae are blunted. There is inadequate attached gingiva on the facial and lingual areas of teeth 3 and 14 and the mandibular anterior teeth. He has heavy subgingival and supragingival calculus on the mandibular anterior teeth and generalized interproximal nodules throughout the mouth. He has a Class 2 AAP periodontal classification. Eight carious lesions are identified. He brushes his teeth once a day using a medium-bristle toothbrush and uses no other dental aids. His community water is not fluoridated. His diet includes no milk or vegetables, and he eats two king-size chocolate candy bars daily. He knows that the status of his oral health is poor.

CASE STUDY 2

Profile: Ms. B., age 20, was a new client for dental hygiene care. She completed the health history form when she arrived for the appointment. After reviewing the health history, the dental hygienist noted that Ms. B. answered “yes” to the question regarding drug or alcohol addiction. The dental hygienist asked for further clarification from Ms. B. and was told that she had been released from a drug and alcohol addiction program 1 year ago. Ms. B. had been sent to the treatment program as an alternative to jail. The dental hygienist asked if Ms. B. had been able to abstain from using cocaine since she left the program. She encouraged Ms. B. to be totally honest in her response and stressed that if Ms. B. was currently using cocaine, it could cause a life-threatening situation if she were to receive a dental anesthetic. Ms. B. confided that dental appointments always caused her great anxiety and that she did self-medicate before coming to her appointment.

1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Youth drug use continues downward slide, older adult rates of use increase. Available at: www.samhsa.gov/news/newsreleases/060907_nsduh.aspx. Accessed October 9, 2008.

2. National Institute on Drug Abuse: NIDA InfoFacts: rohypnol and GHB. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/Infofacts/RohypnolGHB.html. Accessed October 9, 2008.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse: NIDA InfoFacts: club drugs (GHB, ketamine, and rohypnol). Available at: www.nida.nih.gov/Infofacts/clubdrugs.html. Accessed October 9, 2008.

4. Wu L.T., Pilowsky D.J., Schlenger W.E., Galvin D.M. Misuse of methamphetamine and prescription stimulants among youths and young adults in the community. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:195.

5. Sherman C. Drugs affect men’s and women’s brains differently. Natl Inst Drug Abuse Notes. 2006;20:14.

6. Inaba D.S., Cohen W. Uppers, downers, all arounders. Ashland, Ore: Cinemed; 1990.

7. National Institute on Drug Abuse: NIDA-sponsored survey shows decrease in illicit drug use among nation’s teens but prescription drug abuse remains high. Available at: http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/dec2006/nida-21.htm. Accessed October 9, 2008.

8. National Institute on Drug Abuse: Commonly abused drugs. Available at: www.nida.nih.gov/DrugPages/DrugsofAbuse.html. Accessed October 9, 2008.

9. DeAlba I., Samet J.H., Saitz R. Burden of medical illness in drug and alcohol dependent persons without primary care. Am J Addict. 2004;13:33.

10. Laslett A.M., Crofts J.N. Meth mouth. Med J Aust. 2007;186:661.

11. Coombs R.H. Drug-impaired professionals. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1997.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..