Chapter 12 Unexplained Lameness

Lameness diagnosis is a never-ending challenge, even for an experienced clinician, because despite a logical and thorough investigation it still may prove difficult to reach a satisfactory conclusion. This chapter discusses some of the reasons why a definitive diagnosis may remain elusive. In some horses it may be possible to isolate the source of pain reasonably accurately, but it may not be possible to determine the cause of pain. In other horses the source of pain cannot be determined (see Chapter 97).

False-Negative Responses to Diagnostic Analgesia

A false-negative response to local analgesic techniques may occur for a variety of reasons, including the following:

The following are common case examples:

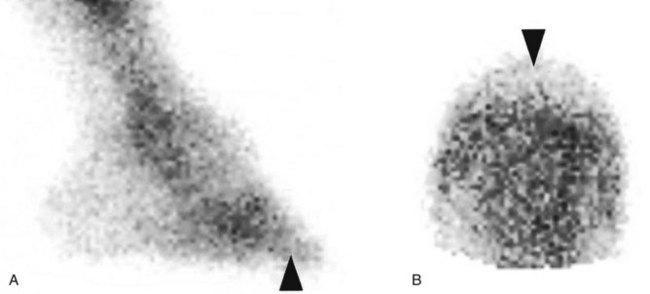

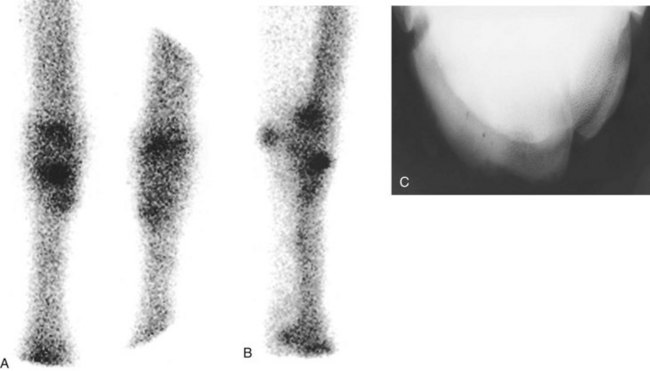

The horse in Figure 12-1 was admitted with suspected back pain but showed obvious bilateral forelimb lameness, with right forelimb lameness predominating. Digital pulse amplitudes were increased in the right forelimb, but there was no response to hoof testers. Nonetheless, the horse appeared clinically to have foot pain typical of laminitis. Apparent desensitization of the foot, performed to convince the owner that the horse had foot pain, produced absolutely no change in the lameness. The horse responded rapidly to treatment for laminitis.

Fig. 12-1 A, Lateral and B, solar scintigraphic images of the front feet of a horse with suspected back pain but clinical signs of laminitis. There is reduced radiopharmaceutical uptake in the toe region (arrowheads). The horse showed no improvement in lameness after apparent desensitization of the lamer right front foot by palmar (abaxial sesamoid) nerve blocks, despite the firm focal pressure applied with artery forceps around the coronary band. However, the horse responded well to symptomatic treatment for laminitis.

Failure to allow sufficient time may in some circumstances result in a false-positive response and then confusion. The tibial and fibular nerves are relatively large, and it takes time for the local anesthetic solution to diffuse into them and to take effect. This time requirement, combined with the deep location of the deep fibular nerve and thus difficulty in precisely locating the site for injection, may result in a response delayed for up to an hour after injection. Testing the efficacy of these blocks through evaluation of cutaneous sensation is unreliable. If the response is deemed to be negative after 30 minutes, and intraarticular analgesia of the compartments of the stifle is then performed and the lameness improves, it may be wrongly inferred that pain originated in the stifle. However, the improvement in lameness may reflect alleviation of pain arising from the hock region. Much wasted time and money may then be spent trying to establish a cause of stifle pain.

Blocking each compartment of the stifle joint separately (e.g., the medial femorotibial joint) may not result in substantial clinical improvement in the lameness, despite the presence of stifle pain. A considerably better response is frequently seen after blocking the medial and lateral femorotibial joints and the femoropatellar joint in combination.

The importance of the clinical examination and repeated observations of a horse cannot be overemphasized. Each clinician has to learn how much to trust nerve blocks. This depends on experience and the frequency of performing blocks. An inexperienced clinician is far more likely to encounter false-negative responses. The results of nerve blocks must be compared with the clinical signs, and if the interpretation is doubtful, the block should be repeated or the area desensitized with a different technique. The clinician must develop experience in the interpretation of improvement in lameness compared with complete alleviation of pain and lameness. This contrast depends to some extent on the degree of the baseline lameness and whether the forelimbs or hindlimbs are involved.

Failure to Perform the Appropriate Nerve Blocks

Failure to perform nerve blocks in a logical and complete sequence can lead to confusion. If the response to a low six-point block in a hindlimb is negative and is followed by a positive response to tibial and fibular nerve blocks, the clinician may conclude that pain arose from the hock. Lesions of the proximal aspect of the suspensory ligament (SL) may be completely overlooked.

Blocking the Wrong Limb

Failure to appreciate that a head nod reflects hindlimb lameness and is not always a sign of forelimb lameness may result in a blocking a forelimb with negative results, when the primary source of pain is in the ipsilateral hindlimb.

Sources of Pain That Cannot Be Desensitized by Nerve Blocks

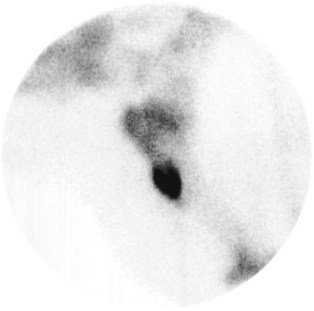

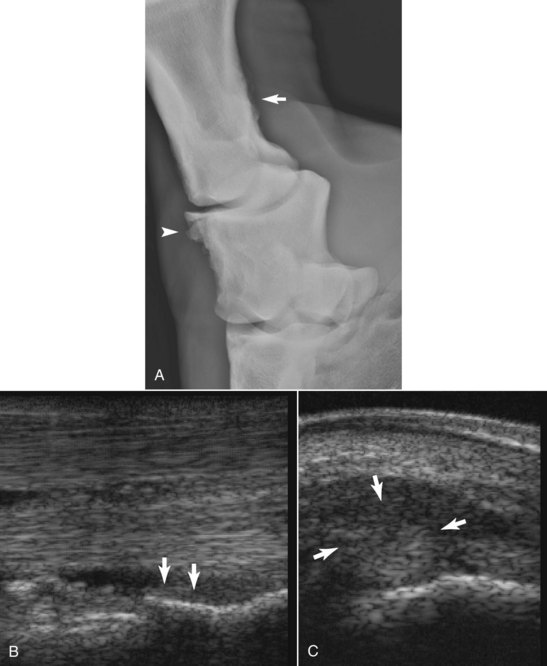

Many regions of the limbs proximal to the carpus and tarsus cannot be satisfactorily desensitized. In young horses, stress fractures are now well-recognized causes of lameness that pain from which in many circumstances cannot be blocked out. In young or older horses, fractures of the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus (Figure 12-2), the proximal aspect of the fibula (Figure 12-3), the third trochanter of the femur, and the tuber ischium (Figure 12-4) are all causes of lameness that are unaffected by nerve blocks.

Fig. 12-2 Lateral scintigraphic image of the shoulder region of a 6-year-old Warmblood with acute onset of moderate left forelimb lameness. Note the marked focal increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the region of the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus. There was a slightly displaced fracture of the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus, which healed satisfactorily with conservative management.

Fig. 12-3 Caudocranial radiographic image of the left stifle of a general purpose riding horse with recent-onset, episodic, and transient severe left hindlimb lameness. There is a fracture of the proximal aspect of the fibula (large arrow). The lucent line separating the different centers of ossification further distally (small arrow) should not be confused as a fracture. There was little evidence of bony union after 6 weeks, but after 12 weeks the fracture healed satisfactorily.

Fig. 12-4 A, Dorsal oblique and B, caudal scintigraphic images of the tubera ischii of an 8-year-old Grand Prix show jumper with loss of hindlimb power and a tendency to jump to the right. There is increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the right tuber ischium and a change of contour compatible with a fracture.

Muscle injuries, such as tearing or fibrosis of brachiocephalicus or the pectoral muscles, may have no localizing signs (see page 152). Associated lameness cannot be influenced by nerve blocks. Atypical equine rhabdomyolysis can cause hindlimb lameness without any other clinical signs typical of tying up.

Periarticular lesions of the otifle such as collateral ligament injury are usually associated with detectable soft tissue swelling, but injuries of the patellar ligaments can occur with no localizing clinical signs, and associated pain is often unresponsive to intraarticular analgesia (see Chapter 46). I have also examined five horses with acute onset of severe lameness and mild swelling on the craniomedial aspect of the femoropatellar joint resulting in loss of palpable definition of the patellar ligaments. Lameness was characterized by a markedly shortened cranial phase of the stride at the walk, but less severe lameness at the trot. Ultrasonographic examination revealed the presence of a periarticular hematoma surrounding the patellar ligaments, which themselves were structurally normal.

Pain Associated with a Neuroma

A neuroma may develop secondary to external trauma to a nerve, after abnormal stretching of a nerve, or subsequent to surgery. There is usually intense focal pain on pressure applied directly over the neuroma. However, perineural analgesia of the area may fail to abolish or improve associated lameness. A much better response may be achieved by infiltration of local anesthetic solution directly around the neuroma.

Potentially Confusing Responses to Local Analgesic Techniques

Improvement without complete alleviation of lameness after perineural analgesia is not always easy to interpret. It may reflect failure to completely alleviate pain from a single source, or there may be additional sources of pain. Sometimes lameness improves with each successive block (e.g., palmar digital, palmar [abaxial sesamoid], low four-point, and subcarpal nerve blocks). However, the lameness is not associated with any detectable radiological, ultrasonographic, or scintigraphic abnormalities. Sometimes additional useful information can be obtained by performing intraarticular analgesia of the interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints, but if the response is negative the diagnosis remains inconclusive.

Isolation of pain to a region but failure to define the cause is particularly frustrating. For example, intraarticular analgesia of the femorotibial joints may be positive, but no radiological or ultrasonographic abnormalities may be detectable. Nuclear scintigraphy may reveal a generalized increased uptake of the radiopharmaceutical in the distal aspect of the femur and proximal aspect of the tibia compared with the contralateral limb. Medication of the joints may result in no improvement. Exploratory arthroscopy may reveal minor findings (e.g., mild fibrillation of the cranial meniscal ligaments) of questionable relevance, but evaluation of all the joint surfaces and meniscal cartilages is impossible. The definitive diagnosis for the cause of pain remains elusive. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may permit the identification of subchondral bone injuries and meniscal and ligamentous injuries not accessible to arthroscopic inspection.

The importance of subchondral bone pain as a cause of lameness must not be overlooked. Such pain frequently is present without associated radiological change. A comparison of the responses to intraarticular analgesia and perineural analgesia (and the response or lack thereof to intraarticular medication) may be helpful. With subchondral pain, intraarticular analgesia may have a limited effect. Nuclear scintigraphy is a sensitive indicator of increased modeling in the subchondral bone. MRI has the potential to show subtle structural changes in the subchondral bone.

Until recently, soft tissue lesions within the hoof capsule have proved elusive to definitive diagnosis. Diagnostic ultrasonography, although possible, has marked limitations. Pool-phase scintigraphic images sometimes are helpful. Examination of the navicular bursa may yield useful information about the bursa, the deep digital flexor tendon, and the distal sesamoidean impar ligament. Advanced imaging techniques such as CT and particularly MRI have the best potential to demonstrate soft tissue pathological conditions, although determining the clinical significance of lesions is not necessarily easy.

False-positive results may be obtained if the horse is only mildly lame at investigation but has a history of a more obvious lameness. The detectable mild lameness may not necessarily reflect the original cause. Lameness that is induced when a horse is lunged in small circles on a concrete surface may not reflect the primary cause of lameness. Thus eliminating this lameness by nerve blocks may be misleading. Lameness induced by flexion also may not reflect the principal cause of lameness. Blocking the flexion response does not necessarily identify the primary cause of lameness.

A pony had moderate forelimb lameness that was markedly accentuated by lower limb flexion. The response to flexion was eliminated by either regional or intraarticular analgesia of the fetlock joint. However, the baseline lameness was unchanged and did not respond to any of the nerve blocks that were repeated on several occasions. Surgical removal of a large osseous fragment from the fetlock joint did not improve the lameness.

False Positive Results of Intrasynovial Analgesia

Lameness may be abolished or substantially improved by intraarticular analgesia of the metacarpophalangeal (metatarsophalangeal) joint with no intraarticular pathology. Pain associated with proximal lesions of the cruciate, straight, or oblique sesamoidean ligaments or the insertions of the suspensory branches may be substantially improved by intraarticular analgesia of the fetlock. Therefore in the absence of both clinical signs suggestive of fetlock joint pain (e.g., synovial effusion, joint capsule thickening, pain on manipulation) and radiological abnormalities it is suggested that the distal sesamoidean ligaments and suspensory branches be evaluated ultrasonographically. Intrathecal analgesia of the digital flexor tendon sheath has the potential to remove pain from injured distal sesamoidean ligaments; it may also relieve pain from the deep digital flexor tendon within the hoof capsule. Therefore the distal sesamoidean ligaments should be included in ultrasonographic examination of the palmar soft tissues of the pastern.

Multiple Sources of Pain in a Limb and More than One Lame Limb

Problems can arise in interpretation of nerve blocks in a horse that is lame in more than one limb, especially if there is more than one source of pain in a limb. Perineural blocks usually last for up to 2 to 3 hours unless a long-acting local anesthetic agent, such as bupivacaine, is used. If a horse is lame in several limbs it is usually easiest to start with the lamest limb and block it first. Interpretation becomes difficult if there is a failure to desensitize all the lame limbs simultaneously. If the blocks in one limb are wearing off, then lameness in the least lame limb becomes less apparent. The horse’s tolerance for nerve blocks may also compromise how much can be done. It may be necessary to start again on another occasion using bupivacaine. If simultaneous lameness of the ipsilateral forelimb and hindlimb is suspected, blocking should begin in the hindlimb. In this situation a substantial amount of the head nod probably originates from the hindlimb component. Because elimination of head nod is vital to improvement after blocking, forelimb diagnostic procedures cannot be fairly evaluated.

Very-Low-Grade Lameness

Nerve blocks, especially in hindlimbs, often result in improvement rather than complete alleviation in lameness. Assessing improvement in subtle lameness is nearly impossible. If the horse has a history of more severe lameness previously, delaying further investigation often is worthwhile. The horse should be worked to accentuate the lameness and simplify interpretation of the response to diagnostic analgesic techniques.

Improvement of Lameness in Some Situations, but Unrelieved Lameness under All Situations: Which Is the Baseline Lameness?

Sometimes a horse has lameness that appears different in nature under different circumstances. Such findings may be related to more than one cause of lameness, and it is important to recognize this fact. For example, a dressage horse had left forelimb lameness that was apparent to the rider only when the horse was ridden on the right rein (to the right). Clinical examination revealed left forelimb lameness on the right rein on the lunge on a hard surface. This was alleviated by desensitization of the foot. However, desensitization did not alter the lameness that was apparent when the horse was ridden. The cause of the lameness could not be identified. It is vitally important to relate the results of the investigation to the history.

Challenges to Lameness Diagnosis

Very Intermittent or Sporadic Lameness

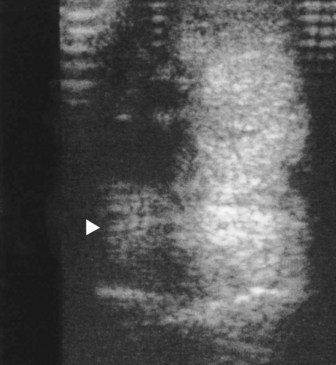

Sometimes lameness is intermittent, and the horse may be perfectly normal between episodes. Lameness may be provoked only by maximal exercise in competition. It is very important to carefully assess the history and get the owner to pay great attention to any clinical features of the lameness when present. For example, mild, transient diffuse swelling in the midmetacarpal region medially may reflect axial impingement of a splint on the SL (Figure 12-5) (see Chapter 72). Spontaneous resolution of hindlimb lameness after standing still is suggestive of aortoiliacofemoral thrombosis (see Chapter 50). Ask the owner to assess the reaction to manipulation of specific joints when the horse is lame. Pain on manipulation may suggest a joint problem such as hemarthrosis.

Fig. 12-5 Transverse ultrasonographic image of the palmar metacarpal soft tissues of the right forelimb of an endurance horse at 10 cm distal to the accessory carpal bone. Medial is to the left. The horse had low-grade lameness at the end of endurance rides that resolved completely within 24 hours. Note the echogenic tissue (arrowhead) next to the suspensory ligament (SL). This was a granulomatous reaction between an exostosis on the second metacarpal bone (McII) and the SL. The distal half of the McII was excised and the granulomatous tissue removed. The horse made a complete recovery.

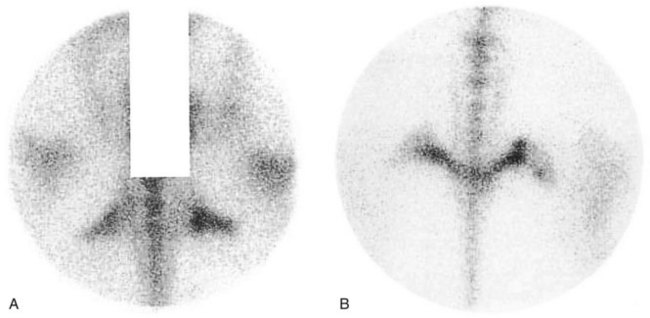

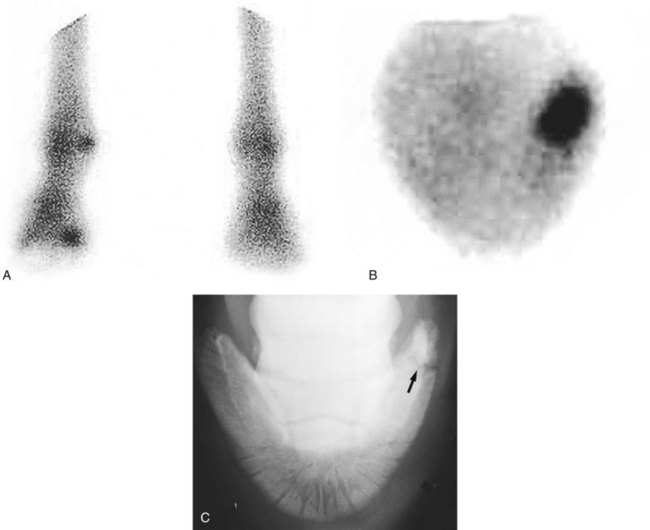

If it is not possible to examine the horse when it is lame, nuclear scintigraphic examination can be helpful but also has the potential to mislead (see page 153). For example, an Arab endurance horse had episodic right forelimb lameness that was present only immediately after rides longer than 30 miles. Comprehensive clinical evaluation revealed no evidence of lameness and no suggestions of the cause of previous lameness. Scintigraphic examination revealed increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU) in the third carpal bone of the lame limb (Figure 12-6). Radiographic examination revealed marked increased radiopacity (“sclerosis”) of the third carpal bone in the lame limb only, an unusual finding in an endurance horse and thought likely to be of clinical significance. Another Arab endurance horse had an acute-onset, severe right hindlimb lameness that resolved within 48 hours, but mild, extremely transient, and episodic lameness persisted over the next 3 weeks. Clinical evaluation revealed no suggestion of the cause and no current lameness. Nuclear scintigraphic examination revealed focal intense IRU in the medial plantar process of the distal phalanx, and radiographic examination confirmed a recent fracture (Figure 12-7).

Fig. 12-6 A, Dorsal scintigraphic image of the carpi of an endurance horse with episodic lameness that occurred only during endurance rides. The right forelimb is on the left. There is a focal increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the middle of the distal row of carpal bones in the right forelimb. B, Lateral scintigraphic image of the right carpus. There is increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the dorsal aspect of the third carpal bone. C, Dorsoproximal-dorsodistal oblique radiographic image of the right carpus showing marked increased radiopacity of the radial facet of the third metacarpal bone.

Fig. 12-7 A, Plantar scintigraphic image of the hind feet of an endurance horse with recent onset of left hindlimb lameness that was apparent only after an endurance ride. The horse appeared clinically normal at the time of the examination. There is moderate focal increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the medial aspect of the left hind foot (left). B, Solar scintigraphic image of the left hind foot. Medial is to the right. There is markedly increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the medial plantar process of the distal phalanx. C, Plantarodorsal radiographic image of the left hind foot. There is a fracture of the medial plantar process (arrow). The horse was treated conservatively and made a complete recovery.

Lameness associated with a distal caudal radial exostosis may be severe but extremely sporadic and often resolves rapidly. There may or may not be detectable distention of the carpal sheath at the time of lameness. With such a history of episodic severe lameness, it is worthwhile to examine the carpal sheath ultrasonographically, paying particular attention to the contour of the caudal distal aspect of the radius and the architecture of the deep digital flexor tendon (see page 162).

If nuclear scintigraphic and ultrasonographic findings are negative, it is necessary to try to recreate the circumstances under which the horse exhibits lameness. For example, hemarthrosis can cause a very severe but extremely transient lameness. The horse may be completely normal between episodes. Although hemarthrosis is unusual to rare, the joints most likely affected are the antebrachiocarpal and tarsocrural joints. Diagnosis can be reached only by arthrocentesis at the time of an acute episode, when there is usually some degree of joint capsule distention and pain on manipulation of the affected joint. Working the horse on a treadmill sometimes is helpful (see Chapter 98).

Lameness That Varies within and between Examinations

Sometimes lameness varies considerably in degree both within an examination period and between examinations. This variation makes interpretation of the response to nerve blocks potentially difficult, unless the veterinarian is aware of the fluctuation. It is important to watch a horse move for a sufficient length of time to appreciate any spontaneous changes in the degree of lameness. Horses with a subchondral bone cyst in either the distal aspect of the scapula or the medial femoral condyle may behave in this way. Within a single examination period the horse may appear sound or lame. In such circumstances it is vital to compare the response to nerve blocks with the clinical signs exhibited. For example, if the characteristics of the lameness are suggestive of shoulder pain, but the lameness is apparently improved after desensitization of the foot, consider the possibility of spontaneous improvement in the lameness that is unrelated to the nerve block. This is, however, an unusual clinical situation, and generally it is best to rely on the results of the diagnostic blocks. A combination of nerve blocks, scintigraphic examination, and radiographic examination may enable a conclusive diagnosis to be reached. Any concurrent clinical signs must not be ignored, even if the owner thinks that swelling may have predated the onset of lameness. Core lesions in the deep digital flexor tendon within the digital flexor tendon sheath may cause episodic hindlimb lameness that may be difficult to reproduce. Presence of distention of the digital flexor tendon sheath should prompt ultrasonographic evaluation.

The Dangerous Horse and Nerve Blocks

Some horses do not tolerate needle placement and cannot be restrained safely. Nuclear scintigraphic examination sometimes indicates a diagnosis, but the results may be negative. Under such circumstances the horse can be sedated for each block. This approach obviously is time-consuming and may be of low specificity, because time must be allowed for the sedative to wear off adequately before the response to the block can be assessed. During this time the local anesthetic solution has the potential to diffuse away from the site of injection and influence more remote pain. Sedation may result in a rather sloppy gait, which can hinder interpretation, especially with mild hindlimb lameness characterized only by a toe drag. Therefore horse selection is important. However, bearing in mind these limitations, it may be the only way to proceed. Xylazine is the shortest-acting α2-agonist available and is the drug of choice, but with a difficult horse, combination with an opioid such as butorphanol is usually necessary.

Negative Responses

Negative Response to All Nerve Blocks: Where Next?

Occasionally a horse is evaluated for forelimb or hindlimb lameness that is not influenced by any local analgesic technique. Clinical signs may be suggestive of a source of pain (e.g., the foot). The reason for failure to eliminate or improve pain by nerve blocks that should result in desensitization of a region is not understood, but such results do occur occasionally.2 If the results of the clinical examination suggest foot pain, the foot should be examined radiographically. Alternatively, there may be no clinical clues for the source of pain. Nuclear scintigraphic examination may be helpful in either situation if the pain is bony in origin but is likely to be less helpful for soft tissue injuries.

Negative Responses to Nerve Blocks, No Clinical Clues, and Negative Scintigraphic Findings

In horses with negative or equivocal scintigraphic findings consideration may be given to systematic radiographic examination, bearing in mind that not all bony lesions are sufficiently active to yield positive scintigraphic findings. However, comprehensive radiographic examination is time-consuming, expensive, and frequently unrewarding and potentially results in unnecessary exposure to radiation. Thus it is usually discouraged. In the forelimb, unusual causes of lameness such as neurological disease (usually lower motor neuron diseases, such as equine protozoal myelitis), cervical nerve root pain (radiculitis), spondylosis of the cranial thoracic vertebrae, and pectoral, sternal, or rib pain may be considered. Pain associated with advanced osteoarthritis of the scapulohumeral joint or lesions of the tendon of the biceps brachii is not reliably abolished by intraarticular analgesia of the scapulohumeral joint or intrathecal analgesia of the intertubercular bursa, respectively. Therefore radiographic examination of the cervical and cranial thoracic vertebrae, the scapulohumeral joint, and the cranial ribs may be justified, together with ultrasonographic examination of the shoulder region. In the hindlimb, neurological disease and thoracolumbar or pelvic soft tissue injuries visible neither on pool nor bone phase scintigraphic images should be considered. Keep in mind that horses with forelimb or hindlimb lameness could potentially have a distant source of pain, and comprehensive imaging (whole body bone scan, for instance) may be necessary.

Neck Lesions and Forelimb Lameness

Forelimb lameness that is unassociated with primary limb pain has been recognized in association with bony lesions of the midcervical and caudal cervical vertebrae and the cranial thoracic vertebrae (see Chapters 52 and 53).2,3 There are not necessarily any detectable clinical signs that can be related to the neck. In horses with confusing forelimb lameness, evaluation of the neck with radiography, scintigraphy, or both modalities is certainly indicated.

Referred Pain

The concept of referred pain is well recognized in people but is more difficult in the horse. We must accept that referred pain originating from a lesion far removed from the lame limb may contribute to pain and thus cause lameness.

Previously Unrecognized Causes of Lameness Proximal to the Carpus And Tarsus

I think it is naive to consider that all potential causes of lameness proximal to the tarsus and carpus have been recognized. Injuries that primarily involve bone usually can be identified with nuclear scintigraphic examination. However, scintigraphy is rather insensitive in the identification of soft tissue injuries, although it may help identify some muscle injuries (Figure 12-8). Muscles can be examined ultrasonographically, but we need to know where to look for damage. Acupuncture trigger point sensitivity may provide information. Use of muscle stimulators may help to identify superficial muscles that are damaged. We know that the horse can tear the fibularis tertius, resulting in pathognomonic clinical signs. We do not know if minor injuries to this modified muscle could cause lameness. Tendonous and ligamentous pain without palpable abnormalities and therefore without a specific indication for ultrasonographic examination must always be considered. We must remain open-minded and search for other means of diagnosis.

Fig. 12-8 Lateral scintigraphic image of the right elbow region of a 4-year-old Warmblood stallion with right forelimb lameness evident only at the walk, which was unaltered by any local analgesic technique. Radiopharmaceutical uptake was increased in the biceps brachii muscle (arrow), which corresponded to an area of increased echogenicity compatible with fibrosis.

Misinterpreted Imaging Findings that Result in Misdiagnosis

In horses in which the results of local analgesic techniques are equivocal or negative, it may be tempting to rely on the results of other diagnostic techniques, such as radiography, ultrasonography, and nuclear scintigraphy, without necessarily relating them to the initial clinical signs. Although these imaging modalities may help to confirm a clinical diagnosis, they also have the potential to mislead, especially if interpreted in isolation.

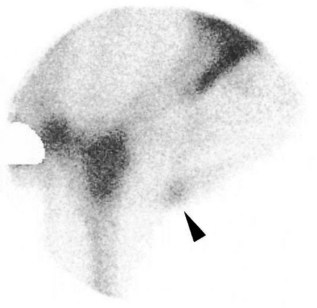

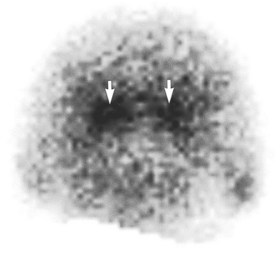

The horse illustrated in Figure 12-9, with focal IRU in the hock, was admitted with left hindlimb lameness that was alleviated by desensitization of the fetlock region. The horse illustrated in Figure 12-10, which has IRU in the distal tibia, was admitted with forelimb lameness. No hindlimb lameness was observed at any time, even after alleviation of the forelimb lameness. The horse in Figure 12-11, with IRU in the region of insertion of the deep digital flexor tendon, had lameness associated with a fracture of the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus.

Fig. 12-9 Lateral scintigraphic image of the tarsus of a 7-year-old riding horse. Note the marked focal increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the hock. Lameness was completely alleviated by desensitization of the fetlock region. There was no radiological abnormality of the hock.

Fig. 12-10 Lateral scintigraphic image of the tarsus and tibia of a 12-year-old advanced event horse with bilateral forelimb lameness associated with distal interphalangeal joint synovitis. The horse had no history or evidence of hindlimb lameness and competed successfully thereafter. Note the intense increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the tibia. The horse was reexamined approximately 8 months later with similar results. The horse had been competing successfully but had recurrent forelimb lameness.

Fig. 12-11 Solar scintigraphic image of the right front foot of a 6-year-old Warmblood. There is increased radiopharmaceutical uptake in the region of insertion of the deep digital flexor tendon on the distal phalanx. The gait characteristics were typical of proximal limb lameness, and lameness was unaltered by desensitization of the foot. The horse had a fracture of the deltoid tuberosity of the humerus.

Not all radiological abnormalities are of clinical significance. Extensive periarticular modeling is sometimes seen on the dorsal aspect of the proximal interphalangeal joint, effectively increasing the joint surface area, probably to increase stability (Figure 12-12). These radiological abnormalities are not necessarily associated with intraarticular pathology or pain. The horse in Figure 12-12 had lameness improved by palmar digital analgesia and abolished by palmar (abaxial sesamoid) nerve blocks. Lameness was not altered by intraarticular analgesia of the proximal interphalangeal joint. Right forelimb lameness, which was worst on the right rein on a circle, was caused by an acute injury of the medial collateral ligament of the distal interphalangeal joint.

Fig. 12-12 A, Flexed dorsolateral-palmaromedial oblique radiographic image of the right front proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint of a 14-year-old advanced event horse with acute onset lameness, which was worst on the left rein on hard or soft surfaces. Lameness was improved by palmar digital analgesia and abolished by palmar (abaxial sesamoid) nerve blocks. There was no response to intraarticular analgesia of the PIP or distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints. There is extensive periarticular modeling of the dorsoproximal aspect of the middle phalanx (arrowhead), effectively increasing the effective PIP joint surface area. There is also mild enthesophyte formation at the insertion of the oblique sesamoidean ligaments on the proximal phalanx (arrow). B, Longitudinal ultrasonographic image of the pastern of the same horse as A. Proximal is to the left. There is enthesophyte formation at the insertion of the oblique sesamoidean ligaments (arrow), which appeared structurally normal. This is another coincidental finding but is an observation commonly made in conjunction with dorsal extension of the PIP joint. C, Transverse ultrasonographic image of the medial aspect of the coronary band of the same horse as A and B. There was subtle soft tissue swelling palpable dorsomedially. The medial collateral ligament of the DIP joint is diffusely mildly hypoechogenic, especially dorsally, but is not enlarged, and there is considerable periligamentous hypoechogenic fluid. The skin surface is abnormally convex. Diagnosis: acute desmitis of the medial collateral ligament of the DIP joint.

Odd Lameness Apparent Only During Riding

Some causes of lameness are apparent only when the horse is ridden. Some of these are easy to block, but a minority fail to respond to local analgesic techniques. Consideration must always be given to rider-induced lameness (see page 157 and Chapter 97), discomfort caused by tack, and gait abnormalities arising through thoracolumbar (see Chapter 52), sacral, and sacroiliac pain (see Chapters 50 and 51). The possibility of the rider’s weight compressing muscles in the saddle and caudal neck region and nerve compression should be considered as potential causes of forelimb pain.

Stepping short on one forelimb at the walk, a feature that may be more easy to feel than to see, is a characteristic of pain in the ipsilateral brachiocephalicus muscle. Palpation of the muscle is usually strongly resented. Lameness may be inapparent at the trot. Horses respond well to physiotherapy treatment.

Lesions of the tendon of the biceps brachii within the intertubercular bursa may result in lameness at the walk characterized by a variable degree of shortening of the cranial phase of the stride; however, at the trot lameness may be absent or slight.

Stepping short on one hindlimb at the walk but having no detectable lameness at the trot is a poorly understood syndrome that may be sudden in onset and tends to be persistent, despite prolonged rest, with or without physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic manipulation, or acupuncture treatment. Such horses usually are worst when ridden at the walk but perform well at all other gaits. There is no response to antiinflammatory analgesic drugs or any analgesic technique. Comprehensive radiographic, scintigraphic, and ultrasonographic examinations are unrewarding.

There is a syndrome of forelimb lameness that is apparent only when a horse is ridden (bareback or with a saddle), which at worst often appears as a hopping-type gait, often most severe with the lame limb on the outside of a circle. Affected horses may try to break to canter in preference to trotting. This lameness is not responsive to any analgesic technique, and radiographic, ultrasonographic, and scintigraphic examination of the forelimbs, neck, ribs, sternum, and thoracolumbar region usually results in no detectable abnormality. There is a poor response to prolonged rest, with or without physiotherapy, osteopathy, chiropractic manipulation, or acupuncture treatment. There is no response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication. A potential possible cause may be muscle or nerve injury axial to the scapula.

Identifiable Lesions: Which Contribute to the Current Lameness?

The presence of radiological lesions is not necessarily synonymous with pain, or the pain may be low grade and not compromise the horse’s gait sufficiently to be recognized by the rider. For example, a horse may have an acute lameness referable to the stifle. Several lesions may be identified radiologically (e.g., smooth flattening of the middle of the lateral trochlear ridge of the femur, modeling of the medial articular margin of the tibial plateau, and a complete fracture of the proximal aspect of the fibula [see Figure 12-3]). It is likely that acute lameness is related to the fibular fracture. The horse in Figure 12-3 had been coping despite radiological evidence of both osteochondrosis of the femoropatellar joint and osteoarthritis of the medial femorotibial joint.

Other Causes of Lameness

Lacerations and Occult Spiral Fractures

Acute-onset, moderate-to-severe lameness sometimes develops within 2 to 3 weeks of trauma to, or laceration over, a long bone (see Figures 3-3 and 3-4). Sometimes lameness is first observed when the horse is still restricted to box rest and controlled exercise while the wound heals. There may or may not be any detectable focus of pain. Consideration must always be given to the possibility of an occult spiral fracture of, for instance, the radius that was obviously sustained at the time of the initial injury. Occult spiral fractures are most common in the radius but can involve the third metacarpal or metatarsal bones and tibia. Radiographic examination should be performed to eliminate this possibility.

Rib Lesions

A fracture of one or more cranial ribs is a rather unusual cause of forelimb lameness that usually is a sequel to direct trauma, such as a collision with another horse or a gate post, or a fall. There are usually no localizing clinical signs, although secondary neurogenic muscle atrophy may develop within the next 10 to 14 days. The lameness may suggest an upper limb problem. Diagnosis is dependent on radiographic, ultrasonographic, or scintigraphic identification of the fracture.

Sternal Injury

Sternal injury usually causes a change in behavior, such as a tendency to buck when first tacked up and mounted (i.e., extreme cold back behavior) rather than lameness. Frequently it is not possible to elicit pain by deep palpation.

Fracture of the Summits of the Dorsal Spinous Processes in the Withers Region

Acute fractures of the withers usually result in a very shortened forelimb stride and a tendency to move very closely in front (“the miniskirt walk”). There is usually obvious palpable deformity of the withers region. Diagnosis is confirmed radiologically.

Temporomandibular Joint Pain

Pain associated with one or both temporomandibular joints may cause reluctance for the horse to take the bit properly, crookedness in the head and neck carriage, and secondary gait irregularities. The joints can be assessed by applying firm pressure over each joint, which may cause pain, and by opening the mouth and moving the upper and lower jaws relative to one another and assessing mobility. Thermography may be a sensitive indicator of local inflammation. If temporomandibular pain is suspected, further investigation can be performed using nuclear scintigraphic examination and diagnostic ultrasonography.4 Radiography is relatively insensitive unless major bony changes are present.5 The use of a rostral 35-degree lateral 40-degree ventral-caudodorsal oblique view is recommended.6

Neurological Problems and Lameness or Stiffness

Early compressive lesions of the cervical spinal cord can cause an apparent low-grade hindlimb lameness that is characterized by slight toe drag and asymmetrical movement of the hindquarters. Signs of weakness or ataxia may not be evident unless a comprehensive neurological examination is performed, especially if the horse is quite fit and fresh. ![]() Neurological signs may be seen only when the horse is tired and not compensating for its gait deficits.

Neurological signs may be seen only when the horse is tired and not compensating for its gait deficits.

Equine protozoal myelitis can cause rather bizarre forelimb or hindlimb gait abnormalities, either unilaterally or bilaterally. It should be considered in the differential diagnosis of odd gait abnormalities in horses that reside or have spent time in North America (see Chapter 11).

Damage to the branch of the radial nerve that results in an innervation of the extensor muscles of the carpus and digits may cause a subtle gait abnormality that is characterized by a tendency to stumble and is associated with slight knuckling of the carpus and distal limb joints.

Stiff horse syndrome7-9 and equine motor neuron disease10 are unusual neurological conditions in which the horse moves better in the trot and canter than at a walk and may stand abnormally.

Shivering behavior often is seen in one or both hindlimbs in association with hindlimb lameness. ![]() The two conditions generally are unrelated. Shivering behavior may be more apparent when the horse is stressed. The behavior can make it difficult to assess whether any manipulation of the limb causes pain, or whether the horse is uncomfortable with one hindlimb picked up.

The two conditions generally are unrelated. Shivering behavior may be more apparent when the horse is stressed. The behavior can make it difficult to assess whether any manipulation of the limb causes pain, or whether the horse is uncomfortable with one hindlimb picked up.

Stringhalt, or exaggerated flexion of a limb, usually a hindlimb, results in a gait abnormality most obvious at the slower speeds of walk and trot. ![]() It is not usually directly associated with any other form of lameness. It may be sudden or insidious in onset.

It is not usually directly associated with any other form of lameness. It may be sudden or insidious in onset.

Congenital abnormalities of the first ribs in association with abnormalities of the adjacent brachial plexus have been seen as a cause of persistent forelimb lameness (Figure 12-13).

Fig. 12-13 Postmortem specimen showing an anomalous first rib from a 3-year-old Thoroughbred with right forelimb lameness that was not altered by any local analgesic technique. There was an abnormal web of fibrous tissue that extended from this anomalous rib to incorporate part of the brachial plexus on the right side.

Acute-onset, severe, and persistent forelimb lameness has been seen in association with a mediastinal abscess that encroached on the nerve roots of the seventh cervical and first thoracic vertebrae, the stellate ganglion, and the first rib (Figure 12-14). Measurement of fibrinogen may help to identify the presence of an infective or inflammatory process.

Fig. 12-14 A 7-year-old pony with severe right forelimb lameness that progressively deteriorated. The pony had an increased fibrinogen level and intermittent pyrexia. There was a mediastinal abscess that encroached on the roots of the seventh cervical and first thoracic nerves, the stellate ganglion, and the first rib.

Lyme Disease

Lyme disease has frequently been incriminated as a cause of shifting lameness that involves several limbs, but confirmed cases are extremely rare.11 Many horses that are in areas where there are many ticks have relatively high antibody titers to Borrelia burgdorferi,11,12 but this is not diagnostic of clinical disease. Lyme disease may be suspected in adult horses in endemic areas when unusual synovitis develops in absence of any known injection history or presence of a wound (see Chapter 66).

Immune-Mediated Polysynovitis

Immune-mediated polysynovitis is relatively uncommon but may result in generalized stiffness associated with transient synovial distention of several joint capsules. It is frequently not possible to identify the underlying cause, but this condition usually responds to corticosteroid medication (see Chapter 66).

Tack-Induced Pain

An ill-fitting saddle can induce back pain and restricted action or poor performance. The bit can induce pain through poor fit (too narrow or too wide), being too low in the horse’s mouth, banging on the canine teeth, pinching the corners of the horse’s mouth, or being too severe. Any oral pain related to the bit, sharp teeth, or lacerations of the tongue, cheeks, or corners of the horse’s mouth may cause reluctance to accept the bit properly and gait irregularities.

Rider-Induced Problems

The rider has a potentially huge influence on the gait of the horse. If a horse is not going forward properly, either because the rider is restricting it or because the rider is not asking it to go forward properly, the forelimb and hindlimb gaits may appear irregular, mimicking pain-induced lameness. An overweight rider who is too heavy for the horse may induce hindlimb lameness. A rider who constantly sits crookedly may induce back pain and hindlimb lameness. (Rider-related problems are discussed further in Chapter 97.)

Physical Limitations of the Horse, Temperament, and Confidence

With appropriate handling and training, most horses are cooperative. However, a previously compliant horse can very rapidly change if regularly handled and ridden by someone who lacks confidence, technique, or strength. Such a horse can quickly develop evasions, such as not going forward properly, rearing, bucking, or taking off. These problems may be, but are not necessarily, pain-related. A horse that has never been trained properly may be very difficult and even potentially dangerous to the rider. Horses home-bred by amateur enthusiasts are high-risk candidates. Some horses are innately lazy and unwilling to go forward. Others are very exuberant and excessively forward going and “fizzy.” The veterinarian may be asked to investigate any of these behavioral features as a potentially pain-related problem.

It is important to establish a horse’s previous performance. It may be useful to see a video. Determine if there has been a change in rider or management. Establish what the horse is being fed and how much work it is getting: there is a tendency for people to overfeed and underwork horses. A comprehensive clinical evaluation may need to be repeated on several occasions before you can determine if it is a pain-related problem. Nuclear scintigraphic examination of selected areas may be useful to eliminate the presence of any underlying problems and to convince the owner that there is not a physical problem. A change of rider or work pattern may be necessary. The use of high doses of nonsteroidal, antiinflammatory drugs (e.g., 2 to 3 g of phenylbutazone, twice daily for at least 7 to 10 days) can be helpful to determine if the problem is pain related, but be aware that there may be a placebo effect. Not all pain responds to phenylbutazone, so a negative response does not preclude a pain-induced problem (see Chapter 97).

Reproductive Problems*

Some mares become more difficult to handle and ride when in season. Mares with coliclike discomfort, hindlimb lameness, or back pain when the rider is in the saddle may have painful ovaries, especially in the periovulatory period.13,14 Indeed, pressure applied to the ovaries per rectum can elicit a pain response.15 Palpation of a large ovulatory follicle or a follicle that has recently ovulated, other genital tract characteristics of estrus, and concomitant behavioral signs of estrus may support this diagnosis. The discomfort should subside shortly after ovulation, but it may recur with future cycles.14

Periovulatory discomfort is thought to be caused by a combination of extremely enlarged follicles that affect neighboring tissues and the release of follicular fluid during ovulation, some of which may leak into the peritoneal cavity and cause localized inflammation. These factors may result in localized pain that lasts approximately 24 to 48 hours.

The estrous cycle is also characterized by changes in the hormonal profile. Specific balances between gonadotropins and sex steroids are necessary for smooth transitions between phases of the reproductive cycle. It has been proposed that any alteration in the ratios between luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone; androgens, estrogens, and progestins; or both results in erratic behavior that leads to poor performance. The judicious use of a synthetic progestagen such as altrenogest (Regumate, Intervet, Millsboro, Delaware) to stop the mare’s cycling can sometimes be helpful. Ovariectomy is a treatment of last resort and does not reliably influence performance-related problems. Keep in mind that the mare’s behavior when out of season will be the end result if ovariectomy is performed. Some Thoroughbred fillies appear to be predisposed to exertional rhabdomyolysis and have been successfully treated with anabolic steroids such as testosterone and boldenon undecylenate (Equipoise).

Although some stallions can be used successfully for both competition and breeding, especially if the management is good and a very clear distinction is made with handling routines, others cannot focus adequately and thus perform athletically below expectations. Performance may be enhanced by castration. However, although malorientation of testicles is frequently blamed for lameness or poor performance, in the Editors’ experience this is highly unusual.

A scirrhous cord in a gelding or mastitis in a mare can cause loss of hindlimb action and hindlimb stiffness. Chronic episodic, transient hindlimb lameness associated with strenuous work (jumping) has been seen in a stallion with large internal inguinal rings.16 The lameness resolved after herniorrhaphy.

Other Medical Problems

Muscle tumors are a rare cause of lameness, but usually there is localized soft tissue swelling, which should prompt ultrasonographic evaluation and muscle biopsy. Gastric ulceration is usually not a cause of overt lameness but may compromise performance, such as causing difficulties in jumping large spread fences.

Atypical Equine Rhabdomyolysis

Occasionally, equine rhabdomyolysis occurs without any of the typical signs of tying up, generally in event horses or endurance horses. Most commonly this is recognized during competition, but it can occur at other times. A horse may pull up with an unexplained unilateral or bilateral hindlimb lameness, which may be mild to severe. The horse does not show any distress, and there are no localizing clinical signs. This may resolve, only to recur in association with exercise. Measurement of serum muscle enzymes will reveal elevated creatine kinase and aspartate transaminase concentrations. The relative degree of rise in concentration of the two enzymes will depend on whether this is a single episode or if recurrent, how frequently the horse is experiencing abnormal muscle stress, and the recent work history. Alternatively, a horse may be performing suboptimally, with reduced quality of paces and reduced scope when jumping, sometimes becoming more restricted during a work period. Affected horses may have focal or diffuse, linear regions of IRU in affected muscle groups in bone phase scintigraphic images, sometimes varying in intensity in different muscle groups. Aspartate transaminase concentration will be elevated.

Vascular Lesions

Venous obstruction in the axilla has caused episodic lameness associated with extensive soft tissue swelling in the antebrachium. Diagnosis was confirmed by a vascular scintigraphic study. Brachial thrombosis has also been associated with severe forelimb lameness.17

Bone Fragility Disorder

A bone fragility disorder of unknown cause has been described in a small number of horses in the western United States.18 It is characterized by an acute or chronic multilimb lameness, with no localizing clinical signs in some horses. In a small proportion there is bowing of the scapulae, lordosis, or cervical stiffness. The source of pain cannot be identified using diagnostic analgesia. Numerous sites of IRU are identified in the axial skeleton and proximal aspects of the forelimbs and hindlimbs. The condition may be progressive.

Panosteitis-like Lesions

Panosteitis is a well-recognized condition in dogs but has not been documented in the horse. However, I am aware of three horses that have had clinical and radiological signs consistent with this condition. In the dog the cause is unknown, but the relatively high frequency of occurrence in young German shepherd dogs suggests some heritable predisposition. It results in a lameness that waxes and wanes in severity, with episodic severe non–weight-bearing lameness. In the horse this condition has been recognized in mature sport horses and has been characterized by a lameness varying in severity from mild to non–weight bearing, with no localizing clinical signs. The response to perineural analgesia has varied depending on the site of the lesions, which may be multifocal. All three horses had a unilateral or bilateral forelimb lameness, two with the most severe lesions in the radius and one with the most severe lesion in the third metacarpal bone. The lesions are typified radiologically by a patchy increase in medullary opacity, especially near the nutrient foramen, coarse trabeculation, and endosteal thickening (Figure 12-15). The lesions are associated with moderate to intense IRU. Lesions may be identified in more than one limb, although not all appear to be symptomatic. In the dog the condition is managed by systemic administration of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and is usually self-limiting.

Fig. 12-15 A, Dorsomedial-palmarolateral oblique radiographic image of the metacarpal region of the left forelimb of a 9-year-old advanced event horse with left forelimb lameness that varied in severity from mild to severe. Perineural analgesia of the palmar and palmar metacarpal nerves in the proximal metacarpal region, performed when lameness was relatively mild, resulted in improvement and the development of right forelimb lameness. There are patchy increases in radiopacity in the medulla of the third metacarpal bone, thickening of trabecula, and endosteal new bone consistent with a panosteitis-like condition. Lesions were associated with multifocal regions of intense increased radiopharmaceutical uptake (IRU). B, Lateromedial radiographic image of the left radius of an 8-year-old Thoroughbred event horse with sporadic severe lameness that was unresponsive to local analgesic techniques. Cranial is to the left. Extensive endosteal new bone is present, especially cranially, along with patchy increased opacity in the medulla, consistent with a panosteitis-like condition. Lesions were also present in the right forelimb and were associated with multifocal regions of intense IRU.