Screening the Head, Neck, and Back

It is estimated that 80% to 90% of the western population will experience an episode of acute back pain at least once during their lifetime,1 making it one of the most common problems physical therapists evaluate and treat.2-4

It has been suggested that mechanical low back pain (LBP) and leg pain with spinal causes compose approximately 97% of all cases.5 Nonmechanical spinal disease can be attributed to neoplasm, infection, or inflammation in 1% of all cases with another 2% accounted for by visceral disorders (pelvic organs, gastrointestinal [GI] dysfunction, renal involvement, abdominal aneurysms).6

Most cases of back pain in adults are associated with age-related degenerative processes, physical loading, and musculoligamentous injuries. Many mechanical causes of back pain resolve within 1 to 4 weeks without serious problems. It has been estimated that fewer than 2% of individuals presenting with LBP present with significant neurologic involvement or other signs that require referral or imaging.7 Up to 10% of LBP patients have no identifiable cause.8

Sacroiliac (SI) joint dysfunction can mimic LBP and diskogenic disease with pain referred below the knee to the foot. Studies show SI joint dysfunction is the primary source of LBP in 18% to 30% of people with LBP.8-13 As always, when conducting a physical examination the therapist must consider the possibility of a mechanical problem above or below the area of pain or symptom presentation.

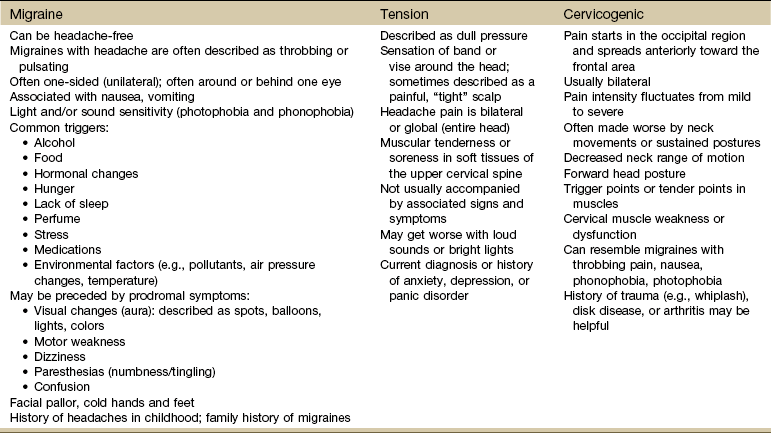

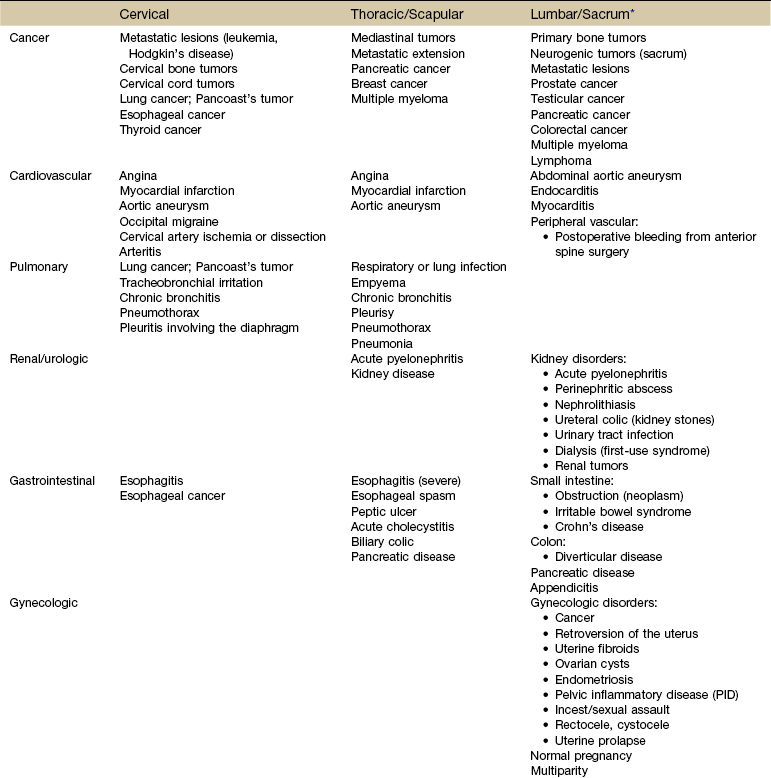

A smaller number of people will develop chronic pain without organic pathology or they may have an underlying serious medical condition. The therapist must be aware that many different diseases can appear as neck pain, back pain, or both at the same time (Table 14-1). For example, rheumatoid arthritis affects the cervical spine early in the course of the disease but may go unrecognized at first.14-16 Neck pain may be a feature of any disorder or disease that occurs above the shoulder blades; it is a rare symptom of neoplasm or infection.17

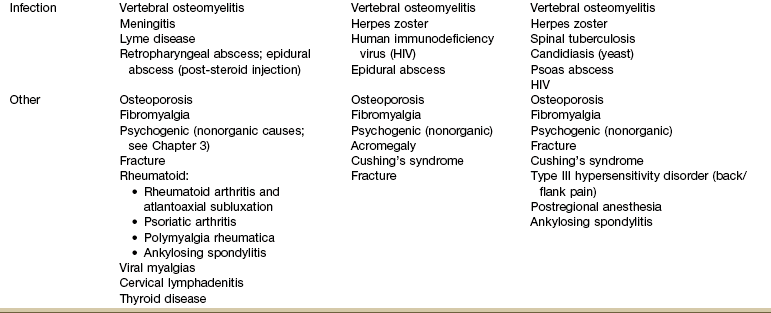

TABLE 14-1

Viscerogenic Causes of Neck and Back Pain

*Sacral sources of low back pain (LBP) are discussed separately in Chapter 15.

In this chapter, general information is offered about back pain with a focus on clinical presentation, while keeping in mind risk factors and associated signs and symptoms typical of each visceral system capable of referring pain to the head, neck, and back. Neck and back pain may arise in the spine from infection, fracture, or inflammatory, metabolic, or neoplastic disorders.

Additionally LBP can be referred from abdominal or pelvic disease. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use is a typical cause of intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal bleeding causing LBP. People most often taking NSAIDs have a history of inflammatory conditions such as osteoarthritis.

Although the incidence of back pain from NSAIDs is fairly low (i.e., number of people on NSAIDs who develop GI problems and referred pain), the prevalence (number seen in a physical therapist’s practice) is much higher.18-20 In other words physical therapists are seeing a majority of people with arthritis or other inflammatory conditions who are taking one or more prescription and/or over-the-counter (OTC) NSAID.21

Screening for medical disease is an important part of the evaluation process that may take place more than once during an episode of care (see Fig. 1-4). The clues about the quality of pain, the age of the client, and the presence of systemic complaints or associated signs and symptoms indicate the need to investigate further.

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate the Head, Neck, or Back

A carefully taken, detailed medical history is the most important single element in the evaluation of a client who has musculoskeletal pain of unknown origin or cause. It is essential for the recognition of systemic disease or medical conditions that may be causing integumentary, muscle, nerve, or joint symptoms.

The history combined with the physical therapy examination provides essential clues in determining the need for referral to a physician or other appropriate health care provider. A history of cancer is most important, however long ago. If a client has had a low backache for years, progressive serious disease is unlikely, though the therapist should not be misled by a chronic history of back pain because the client may be presenting with a new episode of serious back pain. Six weeks to 6 months of increasing backache, often in an older client, may be a signal of lumbar metastases, especially in a person with a past history of cancer.

Watch for history of diabetes, immunosuppression, rheumatologic disorders, tuberculosis, and any recent infection (Case Example 14-1). A history of fever and chills with or without previous infection anywhere in the body may indicate a low-grade infection.

Symptoms are likely to appear some time before striking physical signs of disease are evident and before laboratory tests are useful in detecting disordered physiology. Thus an accurate and sufficiently detailed history provides historical clues that can be significant in determining when the client should be referred to a physician or other appropriate health care provider.

The therapist must always ask about a history of motor vehicle accident, blunt impact, repetitive injury, sudden stress caused by lifting or pulling, or trauma of any kind. Even minor falls or lifting when osteoporosis is present can result in severe fracture in older adults (Case Example 14-2). Anyone who cannot bear weight through the legs and hips should be considered for an immediate medical evaluation.21a

Surgery of any kind can result in infection and abscess leading to hip, pelvic, abdominal, and/or LBP.22 A recent history of spinal procedures (e.g., fusion, diskectomy, kyphoplasty, vertebroplasty) can be followed by back pain, motor impairment, and/or neurologic deficits when complicated by hematoma, infection, bone cement leakage, or subsidence (graft or instrumentation sinking into the bone).23 Infection following spinal epidural injection is an infrequent but potentially serious complication.24,25

Risk Factor Assessment

Understanding who is at risk and what the risk factors are for various illnesses, diseases, and conditions will alert the therapist early on as to the need for screening, education, and prevention as part of the plan of care. Educating clients about their risk factors is a key element in risk factor reduction.

Risk factors vary, depending on family history, previous personal history, and disease, illness, or condition present. For example, risk factors for heart disease will be different from risk factors for osteoporosis or vestibular/balance problems. When it comes to the musculoskeletal system, risk factors, such as heavy nicotine use, injection drug use, alcohol abuse, diabetes, history of cancer, or corticosteroid use, may be important.

Always check medications for potential adverse side effects causing muscular, joint, neck, or back pain. Long-term use of corticosteroids can lead to vertebral compression fractures (Case Example 14-3). Fluoroquinolones (antibiotic) can cause neck, chest, or back pain. Headache is a common side effect of many medications.

Keep in mind that physical and sexual abuse are risk factors for chronic head, neck, and back pain for men, women, and children (see Appendix B-3).

Age is a risk factor for many systemic, medical, and viscerogenic problems. The risk of certain diseases associated with back pain increases with advancing age (e.g., osteoporosis, aneurysm, myocardial infarction, cancer). Under the age of 20 or over the age of 50 are both red flag ages for serious spinal pathology. The highest likelihood of vertebral fracture occurs in females aged 75 years or older.26

As with all decision-making variables, a single risk factor may or may not be significant and must be viewed in context of the whole patient/client presentation. See Appendix A-2 for a list of some possible health risk factors.

Routine screening for osteoporosis, hypertension, incontinence, cancer, vestibular or balance problems, and other potential problems can be a part of the physical therapist’s practice. Therapists can advocate disease prevention, wellness, and promotion of healthy lifestyles by delivering health care services intended to prevent health problems or maintain health and by offering wellness screening as part of primary prevention.

Clinical Presentation

During the examination the therapist will begin to get an idea of the client’s overall clinical presentation. The client interview, systems review of the cardiopulmonary, musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, and integumentary systems, and assessment of pain patterns and pain types form the basis for the therapist’s evaluation and eventual diagnosis.

Assessment of pain and symptoms is often a large part of the interview. In this final section of the text, pain and dysfunction associated with each anatomic part (e.g., back, chest, shoulder, pelvis, sacrum/SI, hip, and groin) are discussed and differentiated as systemic from musculoskeletal whenever possible.

Characteristics of pain, such as onset, description, duration, pattern, and aggravating and relieving factors, and associated signs and symptoms are presented in Chapter 3 (see Table 3-2; see also Appendix C-7). Reviewing the comparison in Table 3-2 will assist the therapist in recognizing systemic versus musculoskeletal presentation of signs and symptoms.

Effect of Position

When seen early in the course of symptoms, neck or back pain of a systemic, medical, or viscerogenic origin is usually accompanied by full and painless range of motion (ROM) without limitations. When the pain has been present long enough to cause muscle guarding and splinting, then subsequent biomechanical changes occur.

Typically, systemic back pain or back pain associated with other medical conditions is not relieved by recumbency. In fact, the bone pain of metastasis or myeloma tends to be more continuous, progressive, and prominent when the client is recumbent.

Beware of the client with acute backache who is unable to lie still. Almost all clients with regional or nonspecific backache seek the most comfortable position (usually recumbency) and stay in that position. In contrast, individuals with systemic backache tend to keep moving trying to find a comfortable position.

In particular, visceral diseases, such as pancreatic neoplasm, pancreatitis, and posterior penetrating ulcers, often have a systemic backache that causes the client to curl up, sleep in a chair, or pace the floor at night.

Back pain that is unrelieved by rest or change in position or pain that does not fit the expected mechanical or neuromusculoskeletal pattern should raise a red flag. When the symptoms cannot be reproduced, aggravated, or altered in any way during the examination, additional questions to screen for medical disease are indicated.

Night Pain

Pain at night can signal a serious problem such as tumor, infection, or inflammation. Long-standing night pain unaltered by positional change suggests a space-occupying lesion such as a tumor.

Systemic back pain may get worse at night, especially when caused by vertebral osteomyelitis, septic diskitis, Cushing’s disease, osteomalacia, primary and metastatic cancer, Paget’s disease, ankylosing spondylitis, or tuberculosis of the spine (see Chapter 3 and Appendix B-25).

Associated Signs and Symptoms

After reviewing the client history and identifying pain types or pain patterns, the therapist must ask the client about the presence of additional signs and symptoms. Signs and symptoms associated with systemic disease or other medical conditions are often present but go unidentified, either because the client does not volunteer the information or the therapist does not ask. To assess for associated signs and symptoms, the therapist can end the client interview with the following question:

The client with back pain and bloody diarrhea or the person with mid-thoracic or scapular pain in the presence of nausea and vomiting may not think the two symptoms are related. If the therapist only focuses on the chief complaint of back, neck, shoulder, or other musculoskeletal pain and does not ask about the presence of symptoms anywhere else, an important diagnostic clue may be overlooked.

Other possible associated symptoms may include fatigue, dyspnea, sweating after only minor exertion, and GI symptoms (see also Appendix A-2 for a more complete list of possible associated signs and symptoms).

If the therapist fails to ask about associated signs and symptoms, the Review of Systems offers one final step in the screening process that may bring to light important clues.

Review of Systems

Clusters of these associated signs and symptoms usually accompany the pathologic state of each organ system (see Box 4-19). As part of the physical assessment, the therapist must conduct a Review of Systems. General questions about fevers, excessive weight gain or loss, and appetite loss should be followed by questions related to specific organ systems. Medications should be reviewed for possible adverse side effects.

Throughout the interview the therapist must remain alert to any yellow (caution) or red (warning) flags that may signal the need for further screening. Review of Systems is important even for clients who have been examined by a medical doctor. It has been reported that only 5% of physicians assess patients for “red flags.”27,28 In contrast, documentation of red flags by physical therapists (at least for patients with LBP) has been reported as high as 98%.29

During the Review of Systems a pattern of systemic, medical, or viscerogenic origin may be seen as the therapist combines information from the client history, risk factors present, associated signs and symptoms, and yellow or red flag findings.

Yellow Flag Findings30

Yellow flags are indicators that findings may be present requiring special attention but not necessarily immediate action. One of the primary yellow flag findings that is prognostically important in individuals with LBP is the presence of psychosocial risk factors (e.g., work, attitudes and beliefs, behaviors, affective presentation).31-34 The presence of these yellow flags suggests a poor response to traditional intervention and the need to address the underlying psychosocial aspects of health and healing. A management approach using cognitive behavioral therapy and/or referral to a mental health professional may be warranted.34a,34b

Work: In particular, belief that pain is harmful resulting in fear-avoidance behavior and belief that all pain must be gone before going back to work or normal, daily activities contribute to yellow (psychosocial) warning flags. Poor work history, unsupportive work environment, and belief that work is harmful all fall under the category of yellow work flags.30

Beliefs: People with chronic LBP who demonstrate yellow flag beliefs also have an increased risk for poor prognosis. This category includes catastrophizing, thinking the worst, a belief that pain is uncontrollable, poor compliance with exercise, low educational background, and the expectation of a quick fix for pain.

Behaviors: Beliefs extend into behaviors such as passive attitude toward rehabilitation, use of extended rest, reduced activity, increased intake of alcohol and other drugs to “manage” the pain, and avoidance or withdrawal from daily and/or social activities.

Affective: Depressed mood, irritability, and heightened awareness of bodily sensations along with anxiety represent affective psychosocial yellow flags (also prognostic of poor outcome for chronic LBP). Other affective yellow flags include feeling useless and not needed, disinterest in outside activities, and lack of family or personal support systems.

The assessment of psychosocial yellow flags should be part of any ongoing management of LBP at any time in the course of the problem. The New Zealand Guidelines34 recommend the administration of a screening questionnaire at 2 to 4 weeks after onset of pain (see Appendix C-4 for a checklist of red/yellow flag indicators).

There is no evidence that this is the optimal time. This is early in the natural history of complaints of LBP, and other interventions may take this long to achieve their effects. In fact, over this time frame, practitioners may still be concerned about red flag conditions, and their time with the client may still be consumed with ensuring compliance with home rehabilitation and analgesics.34

On the other hand, waiting until someone develops chronic pain (3 months) may be too late; the window of opportunity to prevent chronicity will have passed, by definition. Therefore, in anyone with persisting pain, formal exploration of yellow flags should occur no later than 2 months after onset of pain, and possibly by the end of the first month. A practical clinical approach would be to begin screening for yellow flag issues at the 1-month follow-up appointment.35

Red Flag Signs and Symptoms

Watch for the most common red flags associated with back pain of a systemic origin or other medical condition (Box 14-1) but be aware that some recommended red flags have high false-positive rates when used in isolation.36 Each condition (e.g., infection, malignancy, fracture) will likely have its own predictive risk factors. A recent systematic review in the (medical) primary care setting reported that only three red flags are associated with fracture (prolonged use of corticosteroids, age older than 70 years, and significant trauma).36 Individuals with serious spinal pathology almost always have at least one red flag that can be missed when the clinician (physician or therapist) assumes the client’s symptoms are the result of mechanical-induced back pain. (See also Appendix A-2.)

Key findings are advancing age, significant recent weight loss, previous malignancy, and constant pain that is not relieved by positional change or rest and is present at night, disturbing the person’s sleep. Poor response to conservative care or poor success with comparable care is an additional red flag in the diagnosis and management of musculoskeletal spine pain.37 According to one source, cancer as a cause of LBP can be ruled out with 100% sensitivity when the affected individual is younger than 50 years old, has no prior history of cancer, no unexplained or unintended weight loss, and responds to conservative care.6

According to a recent systematic review, five red flags have been identified to screen for vertebral fractures in clients presenting with acute LBP including age over 70, female sex, major trauma, pain and tenderness, and a distracting painful injury.38 Older females, especially older adults who have used corticosteroids, are predisposed to osteoporosis and increased risk of fracture from even minor trauma.39,40

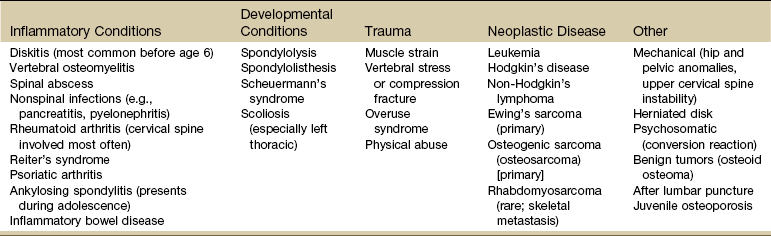

More recent evidence to suggest that backache is a frequent finding in children and adolescents and is seldom associated with serious pathology has been published.41-43 But back pain in children is still considered a red flag, especially in young children43a and/or if it has been present for more than 6 weeks because of the concern for infection or neoplasm.43b,43c Children are less likely to report associated signs and symptoms and must be interviewed carefully. Ask about any other joint involvement, swelling anywhere, changes in ROM, and the presence of any constitutional and GI symptoms. A recent history of viral illnesses may be linked to myalgias and diskitis. Most common causes of back pain in children are listed in Table 14-2.

TABLE 14-2

Causes of Back Pain in Children

From Kliegman RM, editor: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2006, WB Saunders. Used with permission.

Red flags requiring medical evaluation or reevaluation include back pain or symptoms that are not improving as expected, steady pain irrespective of activity, symptoms that are increasing, or the development of new or progressive neurologic deficits such as weakness, sensory loss, reflex changes, bowel or bladder dysfunction, or myelopathy.38

Indications for the use of plain films of the lumbar spine include any of the following features44:

Use the Quick Screen Checklist (see Appendix A-1) to conduct a consistent and complete screening examination.

Location of Pain and Symptoms

There are many ways to examine and classify head, neck, and back pain. Pain can be divided into anatomic location of symptoms (where is it located?): Cervical, thoracic, scapular, lumbar, and SI joint/sacral (as shown in Table 14-1). For example, intrathoracic disease refers more often to the neck, mid-thoracic spine, shoulder, and upper trapezius areas. Visceral disease of the abdomen and/or pelvis is more likely to refer pain to the low back region. Later in this section, spine pain is presented by the source of symptoms (what is causing the problem?).

Whenever faced with the need to screen for medical disease the therapist can review Table 14-1. First identify the location of the pain. Then scan the list for possible causes. Given the client’s history, risk factors, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms, are there any conditions on this list that could be the possible cause of the client’s symptoms? Is age or sex a factor? Is there a positive family or personal history?

Sometimes reviewing the possible causes of pain based on location gives the therapist a direction for the next step in the screening process. What other questions should be asked? Are there any tests that will help differentiate symptoms of one anatomical area from another? Are there any tests that will help identify symptoms that point to one system versus another?

Head

The therapist may evaluate pain and symptoms of the face, scalp, or skull. Headaches are a frequent complaint given by adults and children. It may not be the primary reason for seeing a physical therapist but is often mentioned when asked if there are any other symptoms of any kind anywhere else in the body.

The brain itself does not feel pain because it has no pain receptors. Most often the headache is caused by an extracranial disorder and is considered “benign.” Headache pain is related to pressure on other structures such as blood vessels, cranial nerves, sinuses, and the membrane surrounding the brain. Serious causes have been reported in 1% to 5% of the total cases, most often attributed to tumors and infections of the central nervous system (CNS).1,46 In the past, headache was viewed as many disorders along a continuum. Better headache classifications have brought about the development of many discrete entities among these disorders.47,48 The International Headache Society (HIS) has published commonly used International Classification of Headache Disorders (second edition, revised), which divides headaches into three parts: primary headache, secondary headache, and cranial neuralgias.49,50

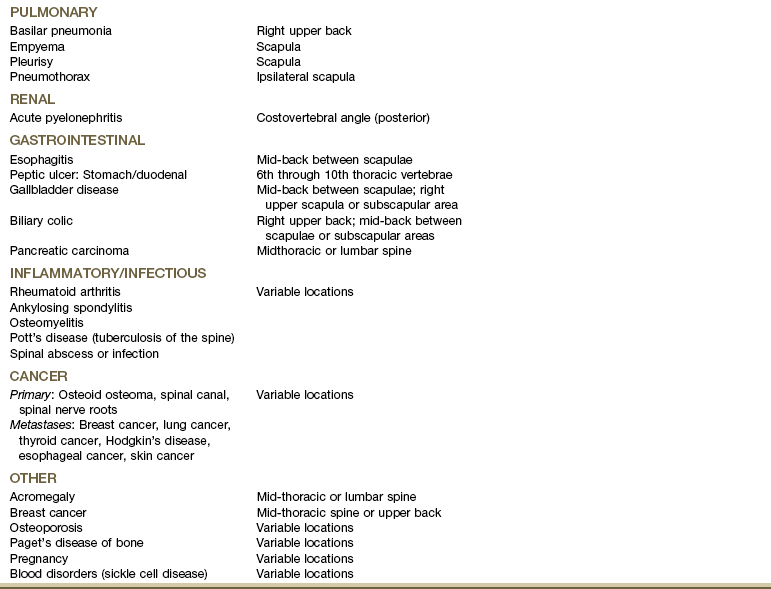

Primary headache includes migraine, tension-type headache, and cluster headache. Secondary headaches, of which there is a large number, are attributed to some other causative disorder specified in the diagnostic criteria attached to them.

The therapist often provides treatment for secondary headache called cervicogenic headache (CGH). This type of headache is defined as referred pain in any part of the head (e.g., musculoskeletal tissues innervated by these nerve roots) caused by spondylitic, fibrotic, or vascular compression or compromise of cervical nerves (C1-C4).51 CGHs are frequently associated with postural strain or chronic tension, acute whiplash injury, intervertebral disk disease, or progressive facet joint arthritis (e.g., cervical spondylosis, cervical arthrosis) (Table 14-3).

Causes of Headaches

Headache can be a symptom of neurologic impairment, hormonal imbalance, neoplasm, side effect of medication,48 or other serious condition (Box 14-2). Headache may be the only symptom of hypertension, cerebral venous thrombosis, or impending stroke.52,53 Sudden, severe headache is a classic symptom of temporal vasculitis (arteritis), a condition that can lead to blindness if not recognized and treated promptly.

Recognizing associated signs and symptoms and performing vital sign assessment, especially blood pressure monitoring, are important screening tools for vascular-induced headaches (see Chapter 4 for information on monitoring blood pressure).

Stress and inadequate coping are risk factors for persistent headache. Headache can be part of anxiety, depression, panic disorder, and substance abuse.54,55 Headaches have been linked with excessive caffeine consumption or withdrawal in children, adolescents, and adults.56

Therapists often encounter headaches as a complaint in clients with posttraumatic brain injury, postwhiplash injury, or postconcussion injury. A constellation of other symptoms are often present such as dizziness, memory problems, difficulty concentrating, irritability, fatigue, sensitivity to noise, depression, anxiety, and problems with making judgments. Symptoms may resolve in the first 4 to 6 weeks following the injury but can persist for months to years causing permanent disability.57,58

Cancer: The greatest concern is always whether or not there is brain tumor causing the headaches. Only a minority of individuals who have headaches have brain tumors. Risk factors include occupational exposure to gases and chemicals and history of cranial radiation therapy for fungal infection of the scalp or for other types of cancer.

A previous history of cancer, even long past history, is a red flag for insidious onset of head and occipital neck pain. Metastatic lesions of the upper cervical spine are difficult to diagnose. Plain radiographs generally appear negative, which can delay diagnosis of clients with C1-C2 metastatic disease.59

The alert therapist may recognize the need for further imaging studies or medical evaluation. Persistent documentation of clinical findings and nonresponse to physical therapy intervention with repeated medical referral may be required.

Although primary head and neck cancers can cause headaches, neck pain, facial pain, and/or numbness in the face, ear, mouth, and lips are more likely. Other signs and symptoms can include sore throat, dysphagia, a chronic ulcer that does not heal, a lump in the neck, and persistent or unexplained bleeding. Color changes in the mouth known as leukoplakia (white patches) or erythroplakia (red patches) may develop in the oral cavity as a premalignant sign.60

Cancer recurrence is not uncommon within the first 3 years after treatment for cancers of the head and neck; often these cancers are not diagnosed until an advanced stage due to neglect on the part of the affected individual. Cervical spine metastasis is most common with distant metastases to the lungs, although any part of the body can be affected.61 Anyone with a history of head and neck cancer should be screened for cancer recurrence when seen by a therapist for any problem.

As always, prevention and early detection improve survival rates. Education is important because most of the risk factors (tobacco and alcohol use, betel nut, syphilis, nickel exposure, woodworking, sun exposure, dental neglect) are modifiable.

Tension-type or migraine headaches can occur with tumors. Rapidly growing tumors are more likely to be associated with headache and will eventually present with other signs and symptoms such as visual disturbances, seizures, or personality changes.62,63 Headaches associated with brain tumors occur in up to half of all cases and are usually bioccipital or bifrontal, intermittent, and of increasing duration. Presence of tumor headache varies, depending on size, location, and type of tumor.64

The headache is worse on awakening because of differences in CNS drainage in the supine and prone positions and usually disappears soon after the person arises. It may be intensified or precipitated by any activity that increases intracranial pressure such as straining during a bowel movement, stooping, lifting heavy objects, or coughing.

Often, the pain can be relieved by taking aspirin, acetaminophen, or other moderate painkillers. Vomiting with or without nausea (unrelated to food) occurs in about 25% to 30% of people with brain tumors and often accompanies headaches when there is an increase in intracranial pressure. If the tumor invades the meninges, the headaches will be more severe.

Recognizing the need for medical referral for the client with complaints of headaches can be difficult. Past medical history can be complex in adults and screening clues are often confusing. Careful review of the clinical presentation is required. For example, although pain associated with the CGH can be constant (a red flag symptom) the intensity often varies with activity and postures. Sustained posture consistently increases intensity of painful symptoms.

Migraines: Migraine headaches are often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and visual disturbances, but the pain pattern is also often classic in description. Age is a yellow (caution) flag because migraines generally begin in childhood to early adulthood. Migraines can first occur in an individual beyond the age of 50 (especially in perimenopausal or menopausal women); advancing age makes other types of headaches more likely. A family history is usually present, suggesting a genetic predisposition in migraine sufferers. In addition to the typical clinical presentation, there are usually normal examination results.

Migraines can present with paralysis or weakness of one side of the body mimicking a stroke. A medical examination is required to diagnose migraine, especially in cases of hemiplegic migraines. Medical evaluation and treatment for migraines in general is recommended.

There is a role for the physical therapist because the beneficial effects of exercise on migraine headaches have been documented.65,66 Physical therapy is most effective for the treatment of migraine when combined with other treatments such as biofeedback67 and relaxation training.68

When present, associated signs and symptoms offer the best yellow or red flag warnings. For example, throbbing headache with unexplained diaphoresis and elevated blood pressure may signal a significant cardiovascular event. Daytime sleepiness, morning headache, and reports of snoring may point to obstructive sleep apnea. Headache-associated visual disturbances or facial numbness raises the suspicion of a neurologic origin of symptoms. Other red flags are listed in Box 14-3.

The therapist is advised to follow the same screening decision-making model introduced in Chapter 1 (see Box 1-7) and reviewed briefly at the beginning of this chapter. Physical examination should include measurement of vital signs, a general assessment of cardiac and vascular signs, and a thorough head and neck examination. A screening neurologic examination should address mental status (including pain behavior), cranial nerves, motor function, reflexes, sensory systems, coordination, and gait (see Chapter 4). Special Questions to Ask: Headache are listed at the end of this chapter and in Appendix B-17.

Cervical Spine

Neck pain is very common and has many mechanical and systemic causes. Neck and shoulder pain and neck and upper back pain often occur together making the differential diagnosis more difficult.

Traumatic and degenerative conditions of the cervical spine, such as whiplash syndrome and arthritis, are the major primary musculoskeletal causes of neck pain.69 The therapist must always ask about a history of motor vehicle accident or trauma of any kind, including domestic violence.

Cervical or neck pain with or without radiating arm pain or symptoms may be caused by a local biomechanical dysfunction (e.g., shoulder impingement, disk degeneration, facet dysfunction) or a medical problem (e.g., infection, tumor, fracture). Referred pain presenting in these areas from a systemic source may occur from infectious disease, such as vertebral osteomyelitis, or from cancer, cardiac, pulmonary, or abdominal disorders (see Table 14-1).

Rheumatoid arthritis is often characterized by polyarthritic involvement of the peripheral joints, but the cervical spine is often affected early on (first 2 years) in the course of the disease. Deep aching pain in the occipital, retroorbital, or temporal areas may be present with pain referred to the face, ear, or subocciput from irritation of the C2 nerve root. Some clients may have atlantoaxial (AA) subluxation and report a sensation of the head falling forward during neck flexion or a clunking sensation during neck extension as the AA joint is reduced spontaneously. Symptoms of cervical radiculopathy are common with AA joint involvement.14

Radicular symptoms accompanied by weakness, coordination impairment, gait disturbance, bowel or bladder retention or incontinence, and sexual dysfunction can occur whenever cervical myelopathy occurs, whether from a mechanical or medical cause. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy has been verified as a potential cause of LBP as well.70 The Babinski test may be the most reliable screening test. There is no single reliable or valid clinical screening test or combination of tests that can be used to confirm spinal cord compression myelopathy.71 An imaging study is usually needed to differentiate biomechanical from medical cause of radicular pain, especially when conservative care fails to bring about improvement.72

Torticollis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle may be a sign of underlying thyroid involvement. Anterior neck pain that is worse with swallowing and turning the head from side to side may be present with thyroiditis. Ask about associated signs and symptoms of endocrine disease (e.g., temperature intolerance; hair, nail, skin changes; joint or muscle pain; see Box 4-19) and a previous history of thyroid problems.73

Palpate the anterior spine and have the client swallow during palpation. Palpation of a soft tissue mass or lump should be noted. See guidelines for palpation in Chapter 4. Palpation of a firm, fixed, and immoveable mass raises a red flag of suspicion for neoplasm. Visually inspect and palpate the trachea for lateral deviation to either side.74

Anterior disk bulge into the esophagus or pharynx and/or anterior osteophyte of the vertebral body may give the sensation of difficulty swallowing or feeling a lump in the throat when swallowing. Anxiety can also cause a sensation of difficulty swallowing with a lump in the throat. Conduct a cranial nerve assessment for cranial nerves V and VII (see Table 4-9; see also Appendix B-21).

Vertebral artery syndrome caused by structural changes in the cervical spine is characterized by the client turning the whole body instead of turning the head and neck when attempting to look at something beyond his or her peripheral vision. Combined cervical motions, such as extension, rotation, and side bending, cause dizziness, visual disturbances, and nystagmus.

Headache/neck pain may be the early presentation of an underlying vascular pathology. Decreased blood flow to the brain, referred to as cerebral ischemia, may be caused by vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI)/cervical arterial dysfunction75 secondary to atherosclerosis or other arterial dysfunction. Arterial compression can also occur when decreased vertebral height, osteophyte formation, postural changes, and ligamentous changes reduce the foraminal space and encroach on the vertebral artery. Premanipulative screening tests for vertebral artery patency and other tests to “clear” the upper cervical spine before using upper cervical manipulative techniques (e.g., cervical rotation, alar and transverse ligament stress tests, tectorial membrane stress test) may help identify the underlying cause of neck pain. Consensus on the need to conduct these tests has not been reached because the validity of tests for VBI has not been established.76,77

Caution is advised with older adults, anyone with a history of hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, or long-term use of corticosteroids. A careful history, blood pressure measurements, observing for vascular pain patterns, and conducting a neurologic screening exam (possibly including cranial nerves) are advocated by some prior to upper cervical manipulation.

Thoracic Spine

As with the cervical spine and any musculoskeletal part of the body, the therapist must look for the cause of thoracic pain at the level above and below the area of pain and dysfunction. Possible musculoskeletal sources of thoracic pain include muscle strain, vertebral or rib fracture, zygapophyseal joint arthropathy,78 active trigger points, spinal stenosis, costotransverse and costovertebral joint dysfunction, ankylosing spondylitis, intervertebral disk herniation, intercostal neuralgia, diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), and T4 syndrome.79 Shoulder impingement and mechanical problems in the cervical spine also can refer pain to the thoracic spine.

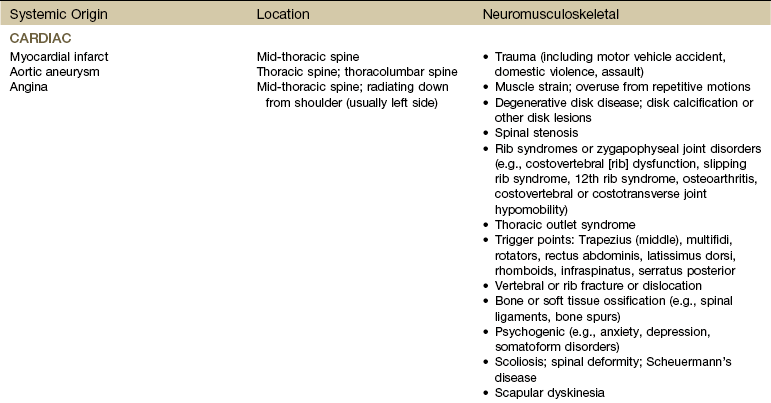

Systemic origins of musculoskeletal pain in the thoracic spine (Table 14-4) are usually accompanied by constitutional symptoms and other associated symptoms. Often, these additional symptoms develop after the initial onset of back pain, and the client may not relate them to the back pain and therefore may fail to mention them.

The close proximity of the thoracic spine to the chest and respiratory organs requires careful screening for pleuropulmonary symptoms in anyone with back pain of unknown cause or past medical history of cancer or pulmonary problems. Thoracic pain can also be referred from the kidney, biliary duct, esophagus, stomach, gallbladder, pancreas, and heart.

Thoracic aortic aneurysm, angina, and acute myocardial infarction are the most likely cardiac causes of thoracic back pain. Usually, there is a cardiac history and associated signs and symptoms such as weak or thready pulse, extremely high or extremely low blood pressure, or unexplained perspiration and pallor.

Tumors occur most often in the thoracic spine because of its length, the proximity to the mediastinum, and direct metastatic extension from lymph nodes with lymphoma, breast, or lung cancer. The client may report symptoms typical of cancer. Tumor involvement in the thoracic spine may produce ischemic damage to the spinal cord or early cord compression since the ratio of canal diameter to cord size is small, resulting in rapid deterioration of neurologic status (Case Example 14-4).

Peptic ulcer can refer pain to the mid-thoracic spine between T6 and T10. The therapist should look for a history of NSAID use and ask about blood in the stools and the effect of eating food on pain and bowel function (see further discussion in Chapter 2).

Scapula

Most causes of scapular pain occur along the vertebral border and result from various primary musculoskeletal lesions. However, cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and GI disorders can cause scapular pain.

Specific questions to rule out potential systemic or medical origin of symptoms are listed in each individual chapter. For example, if the client reports any renal involvement, the therapist can use the questions at the end of Chapter 10 to screen further for urologic involvement. Appendix A contains a series of screening questions based on the presence of specific factors (e.g., sex, joint pain, night pain, shortness of breath).

Lumbar Spine

Low back pain (LBP) is very prevalent in the adult population, affecting up to 80% of all adults sometime in their lifetimes. In most cases, acute symptoms resolve within a few weeks to a few months. Individuals reporting persistent pain and activity limitation must be given a second screening examination.

As Table 14-1 shows, there is a wide range of potential systemic and medical causes of LBP. Older adults with more comorbidities are at increased risk for LBP. Bone and joint diseases (inflammatory and noninflammatory), lung and heart diseases, and enteric diseases top the list of conditions contributing to LBP in older adults.11,80

Pain referred to the lumbar spine and low back region from the pelvic and abdominal viscera may come directly from the organ structures, but some experts suspect the referred pain pattern is really produced by irritation of the posterior abdominal wall by pus, blood, or leaking enzymes. If that is the case, the pain is not referred but rather arises directly from the anterior aspect of the back.30

Sacrum/Sacroiliac

Sacral or SI pain in the absence of trauma and in the presence of a negative spring test (posterior-anterior glide of sacrum between the innominates) must be evaluated more closely. The most common etiology of serious pathology in this anatomic region comes from the spondyloarthropathies (disease of the joints of the spine) such as ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, psoriatic arthritis, and arthritis associated with chronic inflammatory bowel (enteropathic) disease.

Spondyloarthropathy is characterized by morning pain accompanied by prolonged stiffness that improves with activity. There is limitation of motion in all directions and tenderness over the spine and SI joints. The most significant finding in ankylosing spondylitis is that the client has night (back) pain and morning stiffness as the two major complaints, but asymmetric SI involvement with radiation into the buttock and thigh can occur.

In addition to back pain, these rheumatic diseases usually include a constellation of associated signs and symptoms, such as fever, skin lesions, anorexia, and weight loss, that alert the therapist to the presence of systemic disease or other medical conditions. Such symptoms present a red flag identifying clients who should be referred to a physician.

Age, sex, and risk factors are important in assessing for systemic origin of symptoms associated with any of these inflammatory conditions. Clients with these diseases have a genetic predisposition to these arthropathies, which are triggered by a number of environmental factors such as trauma and infection. Each of these clinical entities has been discussed in detail in Chapter 12.

Polymyalgia rheumatica and fibromyalgia syndrome are muscle syndromes associated with lumbosacral pain. Fibromyalgia syndrome refers to a syndrome of pain and stiffness that can occur in the low back and sacral areas with localized tender areas. Both these disorders are also discussed in Chapter 12.

Anyone under the age of 45 with low back, hip, buttock, and/or sacral pain lasting more than 3 months should be asked these four questions:

• Do you have morning back stiffness that lasts more than 30 minutes?

• Does the back pain wake you up during the second half of the night?

• Does the pain alternate from one buttock to the other (shift from side to side)?

There is a 70% sensitivity and 81% specificity for inflammatory back pain if two of the four questions are positive. Sensitivity drops to 33% if three of the four questions are answered “yes” but the specificity increases to nearly 100%.80a

Sources of Pain and Symptoms

Pain can be evaluated by the source of symptoms (what is causing the problem?). It could be visceral, neurogenic, vasculogenic, spondylogenic, or psychogenic in origin. Specific symptoms and characteristics of pain (frequency, intensity, duration, description) help identify sources of back pain (Table 14-5).

TABLE 14-5

Neck and Back Pain: Symptoms and Possible Causes

| Symptom | Possible Cause |

| Night pain unrelieved by rest or change in position; made worse by recumbency; back pain, scoliosis, sensory and motor deficits in adolescents163 | Tumor |

| Fever, chills, sweats | Infection |

| Unremitting, throbbing pain | Aortic aneurysm |

| Abdominal pain radiating to mid-back; symptoms associated with food; symptoms worse after taking NSAIDs | Pancreatitis, gastrointestinal disease, peptic ulcer |

| Morning stiffness that improves as day goes on | Inflammatory arthritis |

| Leg pain increased by walking and relieved by standing | Vascular claudication |

| Leg pain increased by walking, unaffected by standing but sometimes relieved by sitting or prolonged rest | Neurogenic claudication |

| “Stocking glove” numbness | Referred pain, nonorganic pain |

| Global pain | Nonorganic pain |

| Long-standing back pain aggravated by activity | Deconditioning |

| Pain increased by sitting | Discogenic disease |

| Sharp, narrow band of pain radiating below the knee | Herniated disk |

| Chronic spinal pain | Stress/psychosocial factors (unsatisfying job, fear-avoidance behavior, work or family issues, attitudes and beliefs) |

| Back pain dating to specific injury or trauma | Strain or sprain, fracture; failed back surgery |

| Back pain in athletic teenager21a | Developmental, trauma, epiphysitis, juvenile discogenic disease, hyperlordosis, spondylosis, spondylolysis, or spondylolisthesis |

| Exquisite tenderness over spinous process | Tumor, fracture, infection |

| Back pain preceded or accompanied by skin rash | Inflammatory bowel disease |

NSAIDs, Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

Modified from Nelson BW: A rational approach to the treatment of low back pain, J Musculoskel Med 10(5):75, 1993.

The therapist must look at the history and risk factors, too. Any associated signs and symptoms that might reflect any one (or more) of these sources should be identified. Again, the therapist can use the tables in this chapter along with screening questions provided in Appendix A to help guide the screening process.

Viscerogenic

Visceral pain is not usually confused with pain originating in the head, neck, and back because sufficient specific symptoms and signs are often present to localize the problem correctly. It is the unusual presentation of systemic disease in the therapist’s practice that will make it more difficult to recognize.

LBP is more likely to result from disease in the abdomen and pelvis than from intrathoracic disease, which usually refers pain to the neck, upper back, and shoulder. Disorders of the GI, pulmonary, urologic, and gynecologic systems can cause stimulation of sensory nerves supplied by the same segments of the spinal cord, resulting in referred back pain.81 As discussed in Chapter 3, the CNS may not be able to distinguish which part of the body is responsible for the input into common neurons.

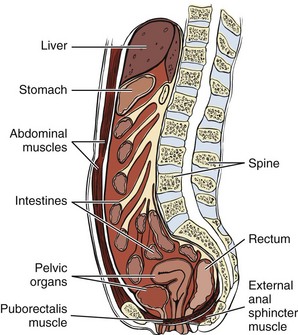

Back pain can be associated with distention or perforation of organs, gynecologic conditions, or gastroenterologic disease. Pain can occur from compression, ischemia, inflammation, or infection affecting any of the organs (Fig. 14-1).

Fig. 14-1 Sagittal view of abdominal and pelvic cavities to show the proximity of viscera to the spine. The abdominal muscles and muscles of the pelvic floor provide anterior and inferior support, respectively. Any dysfunction of the musculature can alter the relationship of the viscera; likewise anything that impacts the viscera can affect the dynamic tension and ultimately the function of the muscles. Pathology of the organs can refer pain through shared pathways or by direct distention as a result of compression from inflammation and tumor.

Referred pain can also originate in organs that share pain innervation with areas of the lumbosacral spine. Colicky pain is associated with spasm in a hollow viscus. Severe, tearing pain with sweating and dizziness may originate from an expanding abdominal aortic aneurysm. Burning pain may originate from a duodenal ulcer.

Muscle spasm and tenderness along the vertebrae may be elicited in the presence of visceral impairment. For example, spasm on the right side at the 9th and 10th costal cartilages can be a symptom of gallbladder problems. The spleen can cause tenderness and spasm at the level of T9 through T11 on the left side. The kidneys are more likely to cause tenderness, spasm, and possible cutaneous pain or sensitivity at the level of the 11th and 12th ribs.

Most often, past medical history, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms will alert the therapist to an underlying systemic origin of musculoskeletal symptoms. Any client older than 50 with back pain, especially with insidious onset or unknown cause, must have vital signs taken, including body temperature.

Careful questioning can elicit important information that the client withheld, thinking it was irrelevant to the problem, such as LBP alternating with abdominal pain at the same level or back pain alternating with bouts of bloody diarrhea.

The therapist should look for clusters of signs and symptoms that may suggest involvement of a particular system. The Review of Systems chart in Chapter 4 (see Box 4-19) can be very helpful in identifying visceral sources of symptoms.

Neurogenic

Neurogenic pain is not easily differentiated. Radicular pain results from irritation of axons of a spinal nerve or neurons in the dorsal root ganglion, whereas referred pain results from activation of nociceptive free nerve endings (nociceptors) in somatic or visceral tissue.

Neurologic signs are produced by conduction block in motor or sensory nerves, but conduction block does not cause pain. Thus, even in a client with back pain and neurologic signs, whatever causes the neurologic signs is not causing the back pain by the same mechanism. Therefore finding the cause of the neurologic signs does not always identify the cause of the back pain.35 The therapist must look further.

Conditions, such as radiculitis, may cause both pain and neurologic signs, but in that case the pain occurs in the lower limb, not in the back or in the upper extremity, not in the neck. If root inflammation also happens to involve the nerve root sleeve, neck or back pain might also arise. In such a case the individual will have three problems each with a different mechanism: neurologic signs due to conduction block, radicular pain due to nerve-root inflammation, and neck or back pain due to inflammation of the dura.35

Identifying a mechanical cause of pain does not always rule out serious spinal pathology. For example, neurogenic pain can be caused by a metastatic lesion applying pressure or traction on any of the neural components. Positive neural dynamic tests do not reveal the underlying cause of the problem (e.g., tumor versus scar tissue restriction). The therapist must rely on history, clinical presentation, and the presence of any neurologic or other associated signs and symptoms to make a determination about the need for medical referral.

Sciatica alone or sciatica accompanying back pain is an important but unreliable symptom. Although 90% of cases of sciatica are caused by a herniated disk,82 there are those other 10% the therapist must also be aware of in the screening process. For example, diabetic neuropathy can cause nerve root irritation. Prostatic metastases to the lumbar and pelvic regions or other neoplasms of the spine can create a clinical picture that is indistinguishable from sciatica of musculoskeletal origin (see Tables 16-1 and 16-6). This similarity may lead to long and serious delays in diagnosis. Such a situation may require persistence on the part of the therapist and client in requesting further medical follow-up.

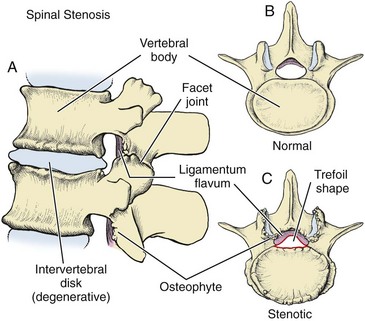

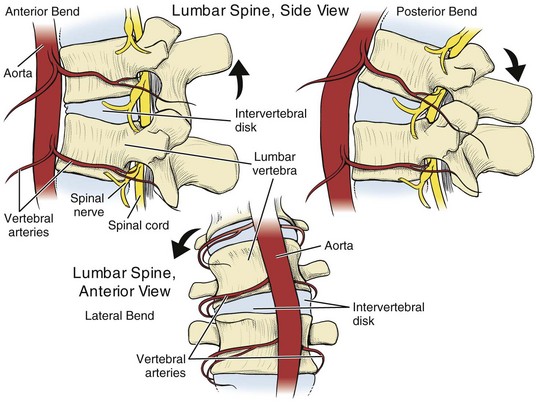

Spinal stenosis caused by a narrowing of the vertebral (spinal) canal, lateral recess, or intervertebral foramina may produce neurogenic claudication (Fig. 14-2). The canal tends to be narrow at the lumbosacral junction, and the nerve roots in the cauda equina are tightly packed. Pressure on the cauda equina from tumor, disk protrusion, spinal fracture or dislocation, infection, or inflammation can result in cauda equina syndrome, which is a neurologic medical emergency.83,84 Cauda equina syndrome is defined as a constellation of symptoms that result from damage to the cauda equina, the portion of the nervous system below the conus medullaris (i.e., lumbar and sacral spinal nerves descending from the conus medullaris).

Fig. 14-2 Spinal stenosis. A, Aging causes a loss of disk height and compression of the vertebral body. The bone attempts to cushion itself by forming a lip or extra rim around the periphery of the endplates. This lipping can extend far enough to obstruct the opening to the vertebral canal. At the same time, the ligamentum flavum begins to hypertrophy or thicken and osteophytes (bone spurs) develop. Degenerative disease can cause the apophyseal (facet) joints to flatten out or become misshapen. Any or all of these variables can contribute to spinal stenosis. B, Normal, healthy vertebral body with a widely open vertebral canal. C, Stenotic spine from a variety of contributing factors. Many clients have all of these changes, but some do not. The presence of pathologic changes is not always accompanied by clinical symptoms.

The medical diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome is not always straightforward. Abnormal rectal tone may be delayed in individuals presenting with cauda equina syndrome. This is because sensory nerves are smaller and more sensitive than motor nerves; even so, some people present with abnormal rectal tone (motor) without saddle anesthesia.85

The emerging nerve root exits through a shallow lateral recess and also may be compressed easily. Any combination of degenerative changes, such as disk protrusion, osteophyte formation, and ligamentous thickening, reduces the space needed for the spinal cord and its nerve roots (see Fig. 14-2).

Confusion with spinal stenosis syndromes may occur when atheromatous change in the internal iliac artery results in ischemia to the sciatic nerve. The subsequent sciatic pain with vascular claudication-like symptoms may go unrecognized as a vascular problem. The therapist may be able to recognize the need for medical intervention by combining a careful subjective and objective examination with knowledge of vascular and neurogenic pain patterns (Table 14-6). This is especially true in the treatment of unusual cases of sciatica or back pain with leg pain.

TABLE 14-6

Back Pain: Vascular or Neurogenic?

| Vascular | Neurogenic |

| Throbbing | Burning |

| Diminished, absent pulses | No change in pulses |

| Trophic changes (skin color, texture, temperature) | No trophic changes; look for subtle strength deficits (e.g., partial foot drop, hip flexor or quadriceps weakness; calf muscle atrophy) |

| Pain present in all spinal positions | Pain increases with spinal extension, decreases with spinal flexion |

| Symptoms with standing: No | Symptoms with standing: Yes |

| Pain increases with activity; promptly relieved by rest or cessation of activity | Pain may respond to prolonged rest |

The client with a neurogenic source of back pain may develop a characteristic pattern of symptoms, with back pain, discomfort in the buttock, thigh, or leg and numbness and paresthesia in the leg developing after the person walks a few hundred yards (neurogenic claudication). The person may be forced to stop walking and obtains relief after long periods of rest. The pattern of symptoms is similar to that of intermittent claudication associated with vascular insufficiency, the major differences being immediate response to rest and position of the spine (see Fig. 14-4; see also Fig. 14-2).

The vertebral canal is wider when the spine is flexed, so relief from neurogenic pain may be obtained when the spine is flexed forward. Some individuals will bend over or squat as if to tie their shoelaces to assume a flexed spine position in public situations. Position of the spine (e.g., flexion, extension, side bending, or rotation) does not affect symptoms of a cardiac origin.

Vasculogenic

Pain of a vascular origin may be mistaken for pain from a wide variety of musculoskeletal, neurologic, and arthritic disorders. Conversely, in a client with known vascular disease, a primary musculoskeletal disorder may go undiagnosed (e.g., diskogenic disease, spinal cord tumor, peripheral neuritis, arthritis of the hip) because all symptoms are attributed to cardiovascular insufficiency.

Vasculogenic pain can originate from both the heart (viscera) and the blood vessels (soma), primarily peripheral vascular disease. Back pain has been linked to atherosclerotic changes in the posterior wall of the abdominal aorta in older adults.86 The therapist can rely on special clues regarding vasculogenic-induced pain in the screening process (Box 14-4).

Vascular injury to the great vessels, which are in proximity to the vertebral column, can occur during lumbar disk surgery or can present as a complication postoperatively. In rare cases, severe bleeding can result in back pain and hypotension in the acute care phase. Late complications of back pain from pseudoaneurysms are rare (less than 0.05%) but can occur years after spine surgery (diskectomy).87,88

Once the history has been reviewed, the therapist assesses the pain pattern present on clinical examination, asks about associated signs and symptoms, and conducts a Review of Systems.

Vascular back pain may be described as “throbbing” and almost always is increased with any activity that requires greater cardiac output and diminished or even relieved when the workload or activity is stopped. A “throbbing” headache may be a vascular headache from a variety of causes.

Women in the perimenopausal and menopausal states may experience vascular headaches from fluctuating hormonal levels. Clients on cardiac medication, such as glyceryl trinitrate (which relaxes smooth muscle, especially blood vessels) and is used to prevent angina, may also report episodes of throbbing headaches. Vascular symptoms of this kind require medical evaluation.

Atherosclerosis and the resulting peripheral arterial disease are the underlying causes of most vascular back pain. Often, the client history will reveal significant cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, advancing age, or elevated serum cholesterol (see Table 6-3 and discussion of peripheral vascular disease in Chapter 6).

Older age is an important red flag when assessing for pain of a vasculogenic origin. Most often, clients with back pain and any of the vascular clues listed are middle-aged and older. A personal or family history of heart disease is a second red flag. Continuous mid-thoracic pain can be a symptom of myocardial infarction, especially in a postmenopausal woman with a positive family history of heart disease.

Older clients with long-term nonspecific lower back pain may have occluded lumbar/middle sacral arteries associated with disk degeneration. Back pain and neurogenic symptoms in the presence of high serum low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels raises a red flag.89

Spondylogenic

Bone tenderness and pain on weight bearing usually characterize spondylogenic back pain (or the symptoms produced by bone lesions). Associated signs and symptoms may include weight loss, fever, deformity, and night pain. There are numerous conditions capable of producing bone pain, but the most common pathologic disorders are fracture from any cause, osteomalacia, osteoporosis, Paget’s disease, infection, inflammation, and metastatic bone disease (Case Example 14-5).

The acute pain of a compression fracture superimposed on chronic discomfort, often in the absence of a history of trauma, may be the only presenting symptom. The client may recall a “snap” associated with mild pain, or there may have been no pain at all after the “snap.” More intense pain may not develop for hours or until the next day.

Back pain over the thoracic or lumbar spine that is intensified by prolonged sitting, standing, and the Valsalva maneuver may resolve after 3 or 4 months as the fractures of the vertebral bodies heal. Clients who undergo kyphoplasty or vertebroplasty often have immediate pain relief.

The pain of untreated vertebral compression fractures may persist because of microfractures from the biomechanical effects of deformity. Other symptoms include pain on percussion over the fractured vertebral bodies, paraspinal muscle spasms, loss of height, and kyphoscoliosis.

When asking about the presence of any associated symptoms the therapist must keep in mind that older adults with vertebral compression fractures or kyphotic posture for any reason may report other pulmonary, digestive, and skeletal problems. These symptoms may not be indicative of back pain from a systemic or medical cause but rather organic dysfunction from a skeletal cause (i.e., somato-visceral response from the effects of a forward bent, kyphotic posture on the viscera).90

Sacral stress fractures should be considered in LBP of postmenopausal women with risk factors and athletes, particularly runners, volleyball players, and field hockey players (see further discussion on spondylogenic causes of sacral pain in Chapter 15).

Psychogenic

Psychogenic pain is observed in the client who has anxiety that amplifies or increases the person’s perception of pain. Depression has been implicated in many painful conditions as the primary underlying problem. The prevalence of depression in physical therapy patients being treated for LBP has been reported as high as 26%.91 There is a concern that depression may go unrecognized or inappropriately managed. Screening for depression can be done quickly and easily with the following two questions:

• During the past month, have you been bothered often by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?

• During the past month, have you been bothered often by little interest or pleasure in doing things?

This two-question tool has been proved to have a 96% sensitivity with a negative likelihood ratio (LR−) of 0.07, and a negative predictive value of 98%. Specificity was reported at 57% with a LR+ of 2.2, and a positive predictive value of 33%.92,93 A yes response to either or both of these questions warrants further evaluation.91 (See additional questions in Appendices B-9 and B-10.)

Anxiety, depression, and panic disorder (see Chapter 3 for further discussion of anxiety, depression, and panic disorder) can lead to muscle tension, more anxiety, and then to muscle spasm. Signs and symptoms of these conditions are listed in Tables 3-9 and 3-10. Other signs of psychogenic-induced back pain may be:

• Paraplegia with only stocking glove anesthesia

• Reflexes inconsistent with the presenting problem or other symptoms present

• Cogwheel motion of muscles for weakness

• Straight leg raise (SLR) in the sitting versus the supine position (person is unable to complete SLR in supine but can easily perform an SLR in a sitting position)

• SLR supine with plantar flexion instead of dorsiflexion reproduces symptoms

The client may use words to describe painful symptoms characterized as “emotional.” Recognizing these descriptors will help the therapist identify the possibility of an underlying psychologic or emotional etiology. An “exploding” or “vicious” headache, “agonizing” neck pain, or “punishing” backache are all red-flag descriptors of psychogenic origin (see Table 3-1).

The client who is unable to concentrate on anything except the symptoms and who reports that the symptoms interfere with every activity may need a psychologic/psychiatric referral. The therapist can screen for illness behavior as described in Chapter 3. Recognizing illness behavior helps the therapist clarify the physical assessment and alerts the therapist to the need for further psychologic assessment.1

Many studies have now shown a link between psychosocial distress and chronic neck or back pain.94-99 Factors associated with chronic LBP may include job dissatisfaction, depression, fear-avoidance behavior, and compensation issues.100,101 It may be necessary to conduct a social history to assess the client’s recent life stressors and history of depression or drug or alcohol abuse.

The presence of psychosocial risk factors does not mean the pain is any less real nor does it reduce the need for symptom control. The therapist concentrates on pain management issues and improving function. Tools to screen for emotional overlay and fear-avoidance behavior are available in Chapter 3 of this text.

Screening for Oncologic Causes of Back Pain

Cancer is a possible cause of referred pain. Tumors of the spine reportedly account for anywhere between 0.1% and 12% of back pain patients seen in a general medical practice.102 Autopsy reports show up to 70% of adults who die of cancer have spinal metastases; up to 14% exhibit clinically symptomatic disease before death.103

Most reports place malignancy as a source of LBP in less than 1% of primary care patients.104 Brain tumors (e.g., meningioma) in the motor cortex can present as LBP; abnormal symptom behavior and atypical responses to treatment may be observed and represent red flags for referral.105 Head and neck pain from cancer is discussed earlier in this chapter (see Causes of Headaches).

Multiple myeloma is the most common primary malignancy involving the spine often resulting in diffuse osteoporosis and pain with movement that is not relieved while the person is recumbent. Back pain with radicular symptoms can develop with spinal cord compression. There can be a long period of development (5 to 20 years) with a chronic presentation of LBP.

For most oncologic causes of back pain, the thoracic and lumbosacral areas are affected. As a general rule, thoracic pain must be screened for metastatic carcinoma. Pain and dysfunction in the lumbosacral area may be caused by direct spread of cancer from the abdomen or pelvic areas. When the lumbar spine is affected by metastases, it is usually from breast, lung, prostate, or kidney neoplasm. GI cancer, myelomas, and lymphomas can also spread to the spine via the paravertebral venous plexus. This thin-walled and valveless venous system probably accounts for the higher incidence of metastases in the thoracic spine from breast carcinoma and in the lumbar region from prostatic carcinoma.

Past Medical History

Prompt identification of malignancy is important, starting with knowledge of previous cancers. Past history of cancer anywhere in the body is a red flag warning that careful screening is required. Always ask clients who deny a previous personal history of cancer about any previous chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Early recognition and intervention does not always improve prognosis for survival from metastatic cancer, but it does reduce the risk of cord compression and paraplegia. It is important to remember that the history can be misleading. For example, almost 50% of clients with back pain from a malignancy have an identifiable (or attributable) antecedent injury or trauma106 (Case Example 14-6).

It is unclear if this is a coincidence or merely reflective of weakness in the musculoskeletal system leading to loss of balance and strength and ultimately an injury. If the trauma results in significant injury (e.g., fracture), then the underlying cancer is usually identified right away. But if soft tissue injury does not necessitate an x-ray or other imaging study, then the underlying oncologic cause may go undetected. Once again the therapist may be the first to recognize the cluster of clinical signs and symptoms and/or red flag findings to suggest a more serious underlying pathology.

Red Flags and Risk Factors

A combination of age (50 or older), previous history of cancer, unexplained weight loss, and failure to improve after 1 month of conservative care has a reported sensitivity of 100%.104 Of these four red flags, a previous history of cancer is the most informative with a pooled LR+ of 23.7 compared with a LR+ of 3 for the other three.99

Until now, there has been an emphasis in this text on advancing age as a key red flag. Back pain at a young age (younger than 20 years old) may be considered a red flag as well. As a general rule, persistent backache due to extraspinal causes is rare in children. As mentioned, mechanical back pain in children is possibly linked with heavy backpacks,107,108 sports, and sedentary lifestyle. However, primary bone cancer occurs most often in adolescents and young adults, hence the addition of this red flag: Age younger than 20 years. Bones of the appendicular skeleton (limbs) are affected more than the spine in this age group, but secondary metastases to the vertebrae can occur.

Clinical Presentation

Back pain associated with cancer is usually constant, intense, and worse at night or with weight-bearing activities, although vague, diffuse back pain can be an early sign of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and multiple myeloma. Pain with metastasis to the spine may become quite severe before any radiologic manifestations appear.103

Back pain associated with malignant retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy from lymphomas or testicular cancers is characterized as persistent, poorly localized LBP present at night but relieved by forward flexion. Pain may be so excruciating while lying down that the person can sleep only while sitting in a chair hunched forward over a table.

Palpate the midline of the spinous processes for any abnormality or tenderness. Perform a tap test (percussion over the involved spinous process).110 Reproduction of pain or exquisite tenderness over the spinous process(es) is a red-flag sign requiring further investigation and possible medical referral.

Neoplasm (whether primary or secondary) may interfere with the sympathetic nerves; if so, the foot on the affected side is warmer than the foot on the unaffected side. Paresis in the absence of nerve root pain suggests a tumor. Severe weakness without pain is very suggestive of spinal metastases. Gross muscle weakness with a full range of SLR and without a history of recent acute sciatica at the upper two lumbar levels is also suggestive of spinal metastases.

A careful assessment of motor strength, sensory levels, proprioception, and reflexes is recommended. These findings can provide a baseline against which to compare future responses that might represent deterioration or undiagnosed lesions at other levels. Abnormal or new findings should be reported.103

A short period of increasing central backache in an older person is always a red-flag symptom, especially if there is a previous history of cancer. The pain spreads down both lower limbs in a distribution that does not correspond with any one nerve root level. Bilateral sciatica then develops, and the back pain becomes worse.

X-rays do not show bone destruction from metastatic lesions until the lytic process has destroyed 30% to 50% of the bone. The therapist cannot assume metastatic lesions do not exist in the client with a past medical history of cancer now presenting with back pain and “normal” x-rays.111-113

Associated Signs and Symptoms

Clinical signs and symptoms accompanying back pain from an oncologic cause may be system related (e.g., GI, GU, gynecologic, spondylogenic), depending on where the primary neoplasm is located and the location of any metastases (Case Example 14-7).

The therapist must ask about the presence of constitutional symptoms, symptoms anywhere else in the body, and assess vital signs as part of the screening process. Unexplained weight loss is a common feature in anyone with tumors of the spine. Review the red flags in Box 14-1 and conduct a Review of Systems to identify any clusters of signs and symptoms.

Screening for Cardiac Causes of Neck and Back Pain

Vascular pain patterns originate from two main sources: cardiac (heart viscera) and peripheral vascular (blood vessels). The most common referred cardiac pain patterns seen in a physical therapy practice are angina, myocardial infarction, and aneurysm.

Pain of a cardiac nature referred to the soma is based on multisegmental innervation. For example, the heart is innervated by the C3 through T4 spinal nerves. Pain of a cardiac source can affect any part of the soma (body) also innervated by these levels. This is why someone having a heart attack can experience jaw, neck, shoulder, arm, upper back, or chest pain. See Chapter 3 for an in-depth discussion of the origins of viscerogenic pain patterns affecting the musculoskeletal system.

On the other hand, pain and symptoms from a peripheral vascular problem are determined by the location of the underlying pathology (e.g., aortic aneurysm, arterial or venous obstruction). Peripheral vascular patterns will be reviewed later in this chapter.

Angina

Angina may cause chest pain radiating to the anterior neck and jaw, sometimes appearing only as neck and/or jaw pain and misdiagnosed as temporomandibular joint (TMJ) dysfunction. Postmenopausal women are the most likely candidates for this type of presentation. If the jaw pain is steady, lasts a long time, or is worst when first waking up in the morning, it could be that the individual is grinding the teeth while sleeping. But jaw pain that comes and goes with physical activity or stress may be a symptom of angina.

Angina and/or myocardial infarction can appear as isolated mid-thoracic back pain in men or women (see Figs. 6-4 and 6-8). There is usually a lag time of 3 to 5 minutes between increase in activity and onset of musculoskeletal symptoms caused by angina.

Myocardial Ischemia

Heart disease and myocardial infarction (MI), in particular, can be completely asymptomatic. In fact, sudden death occurs without any warning in 50% of all MIs. Back pain from the heart (cardiac pain pattern) can be referred to the anterior neck and/or mid-thoracic spine in both men and women.

When pain does present, it may look like one of the patterns shown in Fig. 6-9. There are usually some associated signs and symptoms such as unexplained perspiration (diaphoresis), nausea, vomiting, pallor, dizziness, or extreme anxiety. Age and past medical history are important when screening for angina or MI as possible causes of musculoskeletal symptoms. Vital sign assessment is a key clinical assessment (Case Example 14-8).

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

On occasion, an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) can cause severe back pain (see Fig. 6-11 and additional discussion in Chapter 6). An aneurysm is an abnormal dilation in a weak or diseased arterial wall causing a saclike protrusion. Prompt medical attention is imperative because rupture can result in death. Aneurysms can occur anywhere in any blood vessel, but the two most common places are the aorta and cerebral vascular system. AAA occurs most often in men in the sixth or seventh decade of life.

Risk Factors

The major risk factors for AAA include older age, male sex,114 smoking, and family history.115-118 Although the underlying cause is most often atherosclerosis, the therapist should be aware that aging athletes involved in weight lifting are at risk for tears in the arterial wall, resulting in an aneurysm. There is often a history of intermittent claudication and decreased or absent peripheral pulses. Other risk factors include congenital malformation and vasculitis. Often the presence of these risk factors remains unknown until an aneurysm becomes symptomatic.

Clinical Presentation

Pain presents as deep and boring in the midlumbar region. The pattern is usually described as sharp, intense, severe, or knifelike in the abdomen, chest, or anywhere in the back (including the sacrum). The location of the symptoms is determined by the location of the aneurysm (see Fig. 6-11).

Most aortic aneurysms (95%) occur just below the renal arteries. An objective examination may reveal a pulsing abdominal mass or abnormally widened aortic pulse width (see Fig. 4-55).

Obesity and abdominal ascites or distention makes this examination more difficult. The therapist can also listen for bruits. Bruits are abnormal blowing or swishing sounds heard on auscultation of the arteries.

Bruits with both systolic and diastolic components suggest the turbulent blood flow of partial arterial occlusion. The client will be hypertensive if the renal artery is occluded as well. Peripheral pulses may be diminished or absent. Other historical clues of coronary disease or intermittent claudication of the lower extremities may be present.

Monitoring vital signs is important, especially among exercising senior adults. Teaching proper breathing and abdominal support without using a Valsalva maneuver is important in any exercise program, but especially for those clients at increased risk for aortic aneurysm.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) updated its guidelines for medical screening for AAA in 2005. The new guidelines recommend ultrasound screening for men ages 65 to 75 years who are current or former smokers.115 The therapist should advise men in this age group who have ever smoked to discuss their risk for AAA with a medical doctor. Any male with these two risk factors, especially presenting with any of these signs or symptoms, must be referred immediately.

The cost-effectiveness of screening women for AAA is under investigation. Preliminary studies suggest that despite a lower prevalence of this disease among women (1.1%), when aneurysms occur in women, they seem to enlarge faster than in men119 and there is a higher rupture rate.120

The orthopedic or acute care therapist must be aware that aortic damage (not an aneurysm but sometimes referred to as a pseudoaneurysm) can occur with any anterior spine surgery (e.g., spinal fusion, spinal fusion with cages). Blood vessels are moved out of the way and can be injured during surgery. If the client (usually a postoperative inpatient) has internal bleeding from this complication, there may be:

In such cases, the client’s recent history of anterior spinal surgery accompanied by any of these symptoms is enough to notify nursing or medical staff of concerns. Monitoring postoperative vital signs in these clients is essential.

Screening for Peripheral Vascular Causes of Back Pain

Most physical therapists are very familiar with the signs and symptoms of peripheral vascular disease (PVD) affecting the extremities, including both arterial and venous disease (see discussion in Chapter 6).

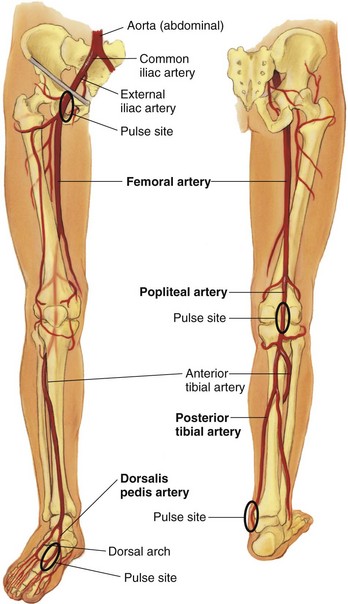

When assessing back pain for the possibility of a vascular cause, remember peripheral vascular disease can cause back pain. The location of the pain or symptoms is determined by the location of the pathology (Fig. 14-3).