Laboratory and Radiographic Asepsis

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

Describe an acceptable laboratory receiving area.

Describe an acceptable laboratory receiving area.

Describe how properly to disinfect microbially soiled prostheses and impressions.

Describe how properly to disinfect microbially soiled prostheses and impressions.

List how properly to sterilize laboratory items used intraorally.

List how properly to sterilize laboratory items used intraorally.

List correct disinfection procedures for laboratory items that are not used intraorally.

List correct disinfection procedures for laboratory items that are not used intraorally.

Design a system of proper environmental barriers and disinfection used during radiographic processes.

Design a system of proper environmental barriers and disinfection used during radiographic processes.

Outline processes that allow for the aseptic processing of radiographic films.

Outline processes that allow for the aseptic processing of radiographic films.

LABORATORY ASEPSIS

Any instrument or piece of equipment used in the oral cavity or on orally soiled prosthetic devices or impressions is a potential source of cross-infection. It is impossible to identify all infectious patients from medical histories or patient conversations. Therefore the only valid posture is to assume (and act as if) all patients are capable of transmitting highly infectious diseases. The dental team must use the same sets of criteria and techniques in all cases.

If contaminated items were to enter the laboratory environment, infectious materials could be spread to prostheses and appliances of other patients. Unsuspecting laboratory personnel also could be placed at increased risk for cross-infection.

Protective Barriers

All items coming from the oral cavity must be sterilized or disinfected before being worked on in the laboratory and before being returned to the patients. Asepsis procedures vary for each type of dental material. General recommendations for procedures and materials can be made. Laboratory infection control also involves, depending on need, the wearing of personal protective barriers such as gloves, safety eyewear, gowns, and masks. One must wear barriers when handling contaminated items until they have been decontaminated.

A successful laboratory infection control program requires meeting two major criteria: (1) the use of proper methods and materials for handling and decontaminating soiled items and (2) the establishment of a coordinated infection control program between dental offices and laboratories. This program will help dental practitioners and dental technologists create and maintain mutually effective infection control programs.

Receiving Areas

The dental team should create a receiving area to handle all items sent to the laboratory or handled in the laboratory areas within the dental practice. The area needs running water and handwashing facilities. To cover the area and the counter surfaces with impervious paper and to clean and disinfect the area regularly is the best practice. The amount of cleaning and disinfection depends on the rate of use of the area. No item (impression or prosthesis) should enter the receiving area until it has been disinfected properly.

One should use personal protective equipment when handling items received in the laboratory unit until they have been disinfected. Such equipment includes gloves and some type of gown. Protective eyewear may be needed to prevent contact with splashes.

Microbially Soiled Prostheses and Impressions

Any prosthesis coming from the oral cavity is a potential source of infection (see Chapters 6 and 7). Most prostheses and appliances cannot withstand standard heat sterilization procedures. An alternative technique for most prostheses is disinfection by immersion after a thorough cleaning. One should clean, disinfect, and rinse all dental prostheses and prosthodontic materials (e.g., impressions, bite registrations, and occlusal rims) using an EPA-registered disinfectant having at least an intermediate level of activity (tuberculocidal claim) before handling the items in the laboratory. One should consult with manufacturers regarding the stability of specific materials (e.g., impression materials) relative to disinfection procedures.

One also must wear gloves and protective outerwear when handling orally soiled prostheses until they have been disinfected properly. One also must wear masks and protective eyewear when handling hazardous chemicals such as disinfectants. Therefore one must always use personal protective barriers and adequate ventilation. Eye/face protection is mandatory whenever one uses rotary or air blasting cleaning equipment.

Some heavily soiled (e.g., with calculus or adhesive) prostheses require cleaning or scrubbing before disinfection. The most efficient (and safest) procedure is to place the prostheses into zippered plastic bags containing ultrasonic detergent and then to place the assembly into an ultrasonic cleaner (Figure 15-1). One also can use glass or plastic beakers or containers. Suspend the bags by pinning them in place at the lid of the ultrasonic cleaner. The goal is to position the bag near the middle of the cleaning solution. Poorer cleaning occurs near the top and bottom of the solution pool. If further hand scrubbing or cleaning is required, keep personal barriers in place. Use air-powered blasters, such as shell blasters, only on cleaned and disinfected prostheses.

FIGURE 15-1 Ultrasonic cleaning of a heavily soiled prosthesis in a zippered plastic bag containing a disinfectant solution.

The team members must follow the same procedures when they receive prostheses from the dental laboratory. Prostheses that have been disinfected properly (treated and rinsed) can be returned to the patient office in a deodorizing solution such as a mouth rinse. Because of the increased risk for adverse tissue response (to the patient and the office staff), prostheses should never be sent out or returned in disinfectant solutions.

One should rinse impressions with tap water after removal and then shake them to remove residual water. Studies indicate that rinsing thoroughly serves an important function in the preliminary removal of adhering microorganisms. One then places rinsed impressions into glass beakers or zippered plastic bags containing an appropriate disinfectant (Figure 15-2). Limiting exposure to any disinfectant solution is best. One must keep all chemicals in well-sealed containers and avoid any contact, especially with skin and mucous membranes (see Chapter 12 for acceptable products). After 15 minutes, one removes the impressions, rinses them well with tap water, and gently shakes them. The impressions are now ready for pouring.

Some types of impressions are sensitive to immersion. Careful selection of disinfectant is required. As an alternative, one can spray these impressions thoroughly and wrap them with paper towels moistened well with the same disinfectant solution. The fibers from paper towels may stick to some impression materials. Check with the manufacturer. After 15 minutes, one removes the impressions, rinses them well, and shakes them gently, and they are ready to be poured.

Spraying has several advantages. Spraying is the treatment of choice for some types of dental materials, for it uses less solution and often one can use the same disinfectant for general disinfection of environmental surfaces. Spraying is probably not as effective as immersion, however, because one cannot ensure constant contact of disinfectant with all surfaces of the impression. When given a choice, one always should select immersion. Spraying also releases disinfectant into the air, thus increasing the chances of personnel exposure. Most disinfectants can be used for spraying.

Disinfection of impression materials is an area of continuing research. Disinfection in certain types of chemical solutions harms some impression types. Other types of disinfectants, however, are safe for use on the same impression materials. Variation in response within a type of impression material (e.g., alginate) by manufacturing source has been noted. A small amount of in-house experimentation is highly recommended.

One should clean and heat sterilize heat-tolerant items used orally, including items such as metal impression trays and face-bow forks.

Grinding, Polishing, and Blasting

As stated before, perform laboratory work on previously disinfected impressions, appliances, and prostheses. Bringing untreated materials into the laboratory establishes the potential for cross-contamination.

Operation of a dental lathe provides an opportunity for the spread of infection and for injury. The rotary action of the wheels, stones, and bands generates aerosols, splatter, and projectiles. Whenever one is using the lathe, one should wear protective eyewear, properly place the front Plexiglas shield, and ensure that the ventilation system is operating properly. The use of a mask is highly recommended. The air-suction motor should be capable of producing an air velocity of at least 200 ft/min. Maximum containment of aerosols and splatter can be achieved when a metal enclosure with hand holes is fixed to the front of the hood of the lathe. One can sterilize or disinfect all attachments, such as stones, rag wheels, and bands, between uses or throw them away. The lathe unit must be disinfected twice a day.

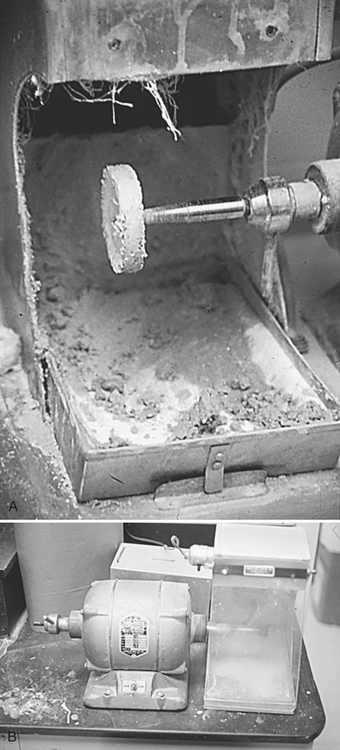

One should use fresh pumice and pan liners for each case (Figure 15-3). The modest cost of the materials and the proven significant microbial contamination in reused pumice prohibits repeated use.

FIGURE 15-3 A, Improperly maintained lathe, pumice reused. B, Clean lathe setup, removable pan, single use of pumice.

Polishing of appliances and prostheses before delivery is a necessary activity. Polishing exposes the operator to potential cross-contamination and physical injury. However, if the item being polished has been prepared aseptically, the risks of infection are reduced to a minimum. To avoid the potential spread of microorganisms, one should obtain all polishing agents (e.g., rouge) in small quantities from larger reservoirs. One should never return unused material to the central stock but should throw it away. Most polishing attachments (e.g., brushes, wheels, and cups) are single-use, disposable items. One should sterilize reusable items between uses, if possible, or at least disinfect the items.

One should follow the manufacturer’s instructions for cleaning and sterilizing or disinfecting items that become contaminated but that normally do not contact the patient (e.g., burs, stones, polishing points, rag wheels, articulators, case pans, and lathes). If manufacturer instructions are not available, one should clean and heat sterilize heat-tolerant items or clean and disinfect, depending on the degree of contamination.

Intermediate Cases

Complete and partial dentures often undergo an intermediate wax try-in stage. Crowns, splinted bridges, and partial denture frameworks often are “test seated” before cementation or soldering. These devices, like wax try-in step dentures, can become soiled with oral fluids. Before returning the items to the laboratory for further processing, one must disinfect them. The procedures in most cases are the same as those described for completed projects. Practices should include specific information regarding the disinfection technique used (e.g., solutions used and length of disinfection) when laboratory cases are sent off-site and on their return.

Return of Completed Cases

Appliances and prostheses being returned to the patient are not free of microbial contamination. These organisms could come from other cases and from the operator’s body, if aseptic procedures are not followed rigorously. Many patients have open oral lesions or are traumatized sufficiently during treatment so as to facilitate easier microbial penetration. A growing number of patients also have impaired immune defense systems or are on chemotherapy programs that render them more susceptible to infectious diseases. The best location for disinfection procedures is chairside.

Other Thoughts

All laboratory infection control activities are designed to accomplish a single goal: breaking the chain of disease transmission. If the person-to-person flow of infection can be interrupted, the safety of the work environment is improved. The chances of patient acquisition of disease during treatment also are greatly reduced.

Infection control processes can be effective only when performed well consistently. For dental laboratory asepsis to be successful, offices and laboratories must perform essential tasks. Redundancies in the system should be identified and minimized. An overall increase in efficiency could be realized when offices and laboratories formally and properly coordinate their efforts.

RADIOGRAPHIC ASEPSIS

Proper infection control methods and materials for dental radiology differ little from those used for procedures more likely to result in blood exposure, such as periodontal therapy, surgical procedures, and many restorative treatments.

Consistent use of the most effective and efficient types of personal protective equipment—such as gloves, masks, gowns, and eyeglasses—decreases the chances of exposure to infectious agents. The team also must use appropriate environmental covers and perform cleaning and disinfection. For dental radiology, only a limited number of items require sterilization. In fact, the team should use heat-tolerant or disposable intraoral devices whenever possible (e.g., film-holding and positioning devices) and should clean and heat sterilize heat-tolerant devices between patients.

The dental team must use the correct materials along with a well-written office infection control procedures manual and regularly scheduled training sessions. A consistently appropriate level of personal and environmental protection must be extended.

The radiographic process also involves the handling of hazardous materials (see Chapter 22). It is imperative that all personnel involved with the development of radiographs be aware of the chemical hazards inherent to the process. Proper hazardous materials management is based on continuous employee training and active participation to minimize the chances of exposure and possible injury. Employees must know which chemical components are hazardous, the location of the hazardous materials list in the office, the labeling system used to identify and describe hazardous chemicals, the warning signs present, and the location and proper use of material safety data sheets.

Unit, Film, and Patient Preparation

The radiographic process offers the possibility that body fluids will contaminate disposable and reusable items. One must wear gloves of some type when taking radiographs and when handling orally soiled radiographic films. Because taking radiographs is a clinical activity, one also must consider the protective gowns and masks worn for restorative procedures. Protective eyewear is a barrier against contact with patient fluids but also prevents exposure to hazardous chemicals.

Plan ahead. Acquire all necessary disposables and heat sterilize materials and accessories. Many of the items used to take radiographs are used once and thrown away. Few reusable items touch unintact skin or mucous membranes or enter normally sterile body tissues. These items, however, still require sterilization. After cleaning, one sterilizes such materials by heat and reuses them. Because most of these reusable items can withstand sterilization temperatures, to process them in a steam autoclave or an unsaturated chemical vapor sterilizer is best. Heat-sensitive materials (e.g., some types of plastic) can be treated by immersion in a high-level disinfectant according to the manufacturer’s instructions (see Chapters 11 and 12).

Environmental infection control requires surface cleaning and disinfection and the use of covers. In private practice, disinfection is preferred because of cost and efficiency concerns. However, the placement of plastic drapes, bags, or tubing over the x-ray unit (tube head, arm, and cone), chair head rest, and control panel probably is better than disinfection because of the numerous and large surfaces touched during the process (Figures 15-4 and 15-5).

Taking of Radiographs

Use films held within FDA-cleared barrier pouches (Figure 15-6).

Exposed films have to be oriented so as to differentiate them easily from unused ones. A possible solution is to place exposed films into a disposable plastic cup or onto a labeled paper towel. This procedure helps to minimize contamination and also facilitates transport.

Environmental surfaces can be protected from contamination (see Figures 15-4 and 15-5) by use of covers, disinfection, or a combination of these. One must disinfect contaminated surfaces that are not covered. See Chapters 10 and 12 for proper disinfection agents, personal protective barriers, and procedures. Items such as control panel knobs and buttons, because of their shape and design, are best covered. Spraying of disinfectant into such areas may cause electric shortages. Because of time constraints, many offices elect to cover the majority of the involved surfaces, such as x-ray cones, rather than disinfect them.

Digital Radiographic Sensors

Digital radiographic sensors and associated computer hardware can be used in place of x-ray films. The digital system allows the image to be displayed on a computer monitor at chairside. The image can then be manipulated and stored for future retrieval. Unlike x-ray films, digital sensors are used over and over on multiple patients. Most, if not all, of these digital sensors cannot be heat sterilized or chemically disinfected. In these cases the only alternative is to prevent the sensor from becoming contaminated. This is accomplished by using a disposable plastic surface cover over the sensor and part of the attached wire (unless the sensor is wireless). When available, FDA-cleared barriers should always be used as covers. Consult with the sensor manufacturer for proper covering or decontamination of the particular type of sensor and computer hardware being used.

Darkroom Activities

One should transport exposed films to the darkroom in a plastic cup or within a folded paper towel but never in the pocket of a clinic gown or jacket. One should avoid touching any surfaces, such as doors, tabletops, or film processing equipment, with soiled gloves during transport.

One should open the films onto a new paper towel or sheet using disposable gloves and should drop the films out of the packets without touching them. One should accumulate the contaminated packets in a disposable towel or in a cup and, after opening all packets, should discard the packets and remove the gloves. One then washes one’s hands and develops the films manually or uses an automatic processor. To prevent artifacts, one should avoid contact between gloves and uncovered film. One should note that developer and fixer, even when microbially contaminated, do not sustain bacterial or fungal growth.

For several years, x-ray films have been sold covered with protective plastic pouches. The pouches also can be purchased separately and placed onto x-ray films chairside (see Figure 15-6). Use of radiographic films in pouches has distinct infection control advantages. If one opens the pouches carefully in the operatory or the darkroom, one finds exposed but unsoiled film packets. Testing indicates that when properly placed, the covers do not allow penetration of fluids.

Daylight Loaders

Potential problems can arise with the use of daylight loaders attached to automatic processors or with “portable darkrooms,” which contain small beakers or cups of developing solutions. These units are equipped with portals that allow penetration of hands and arms with a maximum exclusion of light. This feat is accomplished using cloth or rubber sleeves, cuffs, or flaps. Because the units have limited operational space, chances of cross-infection are increased. The sleeves are difficult to impossible to disinfect properly after soiling.

The only aseptic way to use these units is to insert only disinfected or unsoiled film packets (those formerly in pouches) into the unit and to use powder-free gloves. One can group film packets into plastic cups and place them inside the daylight loader. One then can place unwrapped films into another clean cup or onto a paper towel. After one has opened all films, one can collect the waste packet wraps in a cup. Using a bare hand, one can pick up the films by the edges and feed them into the processor. Manual processing requires gloved hands and clips to dunk the films.

Waste Management

Orally soiled disposable items such as gloves, paper towels, or x-ray film covers are in most locations not considered to be infectious (and thus regulated) medical waste (see Chapter 16). This means that such items do not require special handling, storage, and neutralization procedures before disposal. However, every dental office and clinic has the responsibility to be aware of the current regulations for their location.

American Dental Association. Council on Scientific Affairs and Council on Dental Practice: Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:672–680.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings, 2003. MMWR. 2003;52(RR-17):1–68.

Glass, B.J., Terezhalmy, G.T. Infection control in dental radiology. In Cottone J.A., Terezhalmy G.T., Molinari J.A., eds.: Practical infection control in dentistry, ed 2, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996.

Merchant, V.A. Infection control in the dental laboratory: concerns for the dentist. Compendium. 1993;14:382–390.

Merchant, V.A. Infection control in the dental laboratory environment. In Cottone J.A., Terezhalmy G.T., Molinari J.A., eds.: Practical infection control in dentistry, ed 2, Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1996.

Miller, C.H., Palenik, C.J. Sterilization, disinfection and asepsis in dentistry. In Block S.S., ed.: Disinfection, sterilization and preservation, ed 5, Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 2001.

National Association of Dental Laboratories. Health and Safety Committee: Infection control compliance manual for dental laboratories. Alexandria, Va: National Association of Dental Laboratories; 1992.

Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures: OSAP position paper: laboratory asepsis. Accessed May 2008 from http://www.osap.org/displaycommon.cfm?an=1&subarticlenbr=38.

Palenik, C.J. Dental laboratory asepsis. Dent Today. 2005;24(52):54.

Palenik, C.J., Miller, C.H. Infection control for dental radiology. Dent Asepsis Rev. 1996;17:1–2.

Puttaiah, R., Langlais, R.P., Katz, J.O., Langland, O.E. Infection control in dental radiology. CDAJ. 1995;23:21–28.

White, S.C., Pharoah, M.J. Oral radiology: principles and interpretations, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby; 2004.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

______1. When given the choice, one should disinfect impressions by:

______2. Air-suction motors on dental lathes should be capable of producing an air velocity of at least _______ ft/min.

______3. If a denture is being sent to a dental laboratory for repairs, it should be disinfected:

______4. Today, dental radiographic films should be covered with protective plastic pouches before being used.

______5. Disinfection of dental impressions should last _______ minutes.