Chapter 2 The skin and nails in podiatry

Differential diagnosis of foot infection

Structure and function of the skin

Systemic treatment of foot and nail infections

Clinical observation of the skin and nails is an important aspect of the process of assessment and diagnosis of the patient, and the many indicators provided by these easily observed structures can very quickly point the way to an accurate diagnosis.

AFFECTATIONS OF THE SKIN

The skin provides an insight into the well-being of the individual as a whole as well as the peripheral tissue status. It can provide diagnostic indicators of various systemic disorders, such as pruritus (itchiness) with chronic liver disease or bullae (blisters) with an adverse drug reaction. It provides an indication of the quality of the peripheral tissues, both superficial and deep. The skin will show physical changes, for example in the microcirculation in diabetes, that are also likely to be occurring in the deeper tissues not visible to the clinician. If the skin shows poor tissue viability then it is likely that deeper tissues are in a similar state.

Changes with age are normal, for example fine to coarse wrinkling, mottled hyperpigmentation and yellowing (Gnaidecka & Jemec 1998). Xerosis (fine, dry scales) with actinosis (skin plaques) and elastosis (altered elasticity) are associated with photo damage (Diridollou et al 2001). Skin cancers are covered later in this chapter.

Often, the medical, social and family history in addition to the history of the skin complaint provides a clear indication of the nature of the problem. Observation and clinical tests provide further information. A clear diagnosis is not always possible, as the presentation may not be classic. However, the lack a of definitive diagnosis cannot be used as an excuse for not managing the condition, as symptomatic management should be undertaken until further tests facilitate a differential diagnosis of the condition.

All the following sections assume that the history has been taken, including the drug history. It is good practice to work towards evidence-based care for patients, and it is appropriate to review the results of monitoring and evaluation and modify practices as necessary (Feder et al 1999, Hurwitz 1999), and according to the contemporary literature. However, lack of evidence in the literature of the effectiveness of a particular treatment should not be taken to mean that it is ineffective and thus not to be used (Ryan 1998).

STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION OF THE SKIN

The skin is the largest of the body’s organs and has a number of roles, which include protection, interaction with the environment and homeostasis (Freinkel & Woodley 2001). Three main components of the skin, the epidermis, the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ, basement membrane) and the dermis, are further divided into layers. The epidermis is a stratified squamous keratinising epithelium (MacKie 2003), the outermost layer of which (the stratum corneum) forms the primary barrier for the body. This layer is not an inert structure but is capable of releasing growth factors when traumatised (McKay & Leigh 1991), a point which should be emphasised to discourage patients from rubbing overvigorously when self-treating callus.

The epidermis is avascular, though enervated, and is separated from the dermis by the undulating DEJ. The dermis provides the secondary barrier to the body through its vascular supply, tissue structure and immunological role. The base of the dermis also undulates, and is bounded by adipose tissue and fascia, then muscle.

ACUTE INFLAMMATION

Human tissues respond to trauma by a complex series of events that have yet to be fully understood. This trauma may be mechanical, thermal, photo or chemical, or brought about through allergic or autoimmune events. If blood vessels have been injured, damaged platelets will activate the clotting cascade. Damaged tissues will release chemical messengers (Table 2.1), which start the inflammatory process. In health, sequential phases of proliferation, maturation and repair of the damaged tissue follow inflammation.

Table 2.1 Some chemical/inflammatory mediators that cause the features of inflammation

| From a variety of sources, including mast cells, macrophages, platelets | |

| Have differing functions according to predominance and sequence of release, so different types of inflammatory response occur |

Blood cells and platelets, the immune system and nerves (Tortora et al 2005), chemical transmitters, and tissue cells such as macrophages are among the tissues and systems involved in inflammation. The molecular and cellular events during inflammation flow into and overlap with one with the other (Dealey 2005). Initially, neutrophils arrive, followed by macrophages, lymphocytes and then fibroblasts, which lay down collagen. Epithelial cells migrate on from wound edges over the newly laid down dermis and healing is complete. Healing by first intention will close over 2–5 days; a wound healing by second intention will take longer, the time taken depending on the tissue area that needs to be filled in and covered. The predominance and sequence of mediator release will allow different types of inflammatory response to occur.

The classic and clinical features of inflammation are redness (rubor), heat (calor), swelling (tumour) and pain (dolor); loss of function is sometimes included in this list. These features are brought about through chemical/inflammatory mediators released from damaged tissues (Table 2.1). The main effects of these mediators are on the blood supply, causing vasodilation (redness and heat) and increased blood-vessel permeability that allow plasma proteins and immunoglobulins to pass easily into the tissues (increased fluid interstitially causes swelling). Pressure on nerve endings from the interstitial fluid and the effect of some inflammatory mediators such as substance P and prostaglandins (e.g. PGE1) cause pain.

The mainstay of management for acute inflammation and pain management in healthy individuals is rest, ice, compression and elevation (RICE) (Brown 1992, Humphreys 1999). This should be adapted for different patients and different situations (see also Chs 4, 13 and 16). It is essential to identify the cause of the acute inflammation and, if possible, remove it and inform the patient of the cause so that they can avoid the situation in the future. The therapeutic aim in acute inflammation is to allow it to occur but to control its excesses and keep the phases as short as possible. Therapeutic ultrasound (Hart 1998) and low-level laser therapy (Halery et al 1997) have a part to play in management, along with the application of soothing and cooling substances such as witch hazel and lavender and camomile oils (Hitchen 1987). Controversy exists over the use of orthodox anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. ibuprofen) in acute inflammation but analgesics (e.g. paracetamol) may help in controlling pain.

CHRONIC WOUNDS (ULCERS)

Ulcers (Fig. 2.1) occur where a predisposing condition impairs the ability of the tissue to maintain its integrity or heal from damage. They may be superficial or deep, extending to bone, and may track under the tissues such that there is an extensive area of damage not visible on the skin’s surface. Generally, chronic wounds take weeks to months to heal, and some may take years. All require careful and informed assessment (Wall 1997) and management, which will change as the wound changes. As with any break in the skin barrier, chronic wounds can become infected (Dealey 2005).

Figure 2.1 A pressure sore on a heel is a chronic wound where tissue damage may be far more extensive than is apparent on the surface. Tissue at all levels down to bone may be involved.

Assessment of chronic wounds

It is essential to take a holistic approach to assessing and managing chronic wounds. Risk assessment scores may be calculated (e.g. Waterlow score) to identify those particularly at risk of developing chronic wounds (Dealey 2005). After assessing and obtaining the history of general health and peripheral status (e.g. blood supply (Baker & Rayman 1999), neurological status), specific enquiry about the wound can start.

The features of the skin generally, and that surrounding the wound, the nature of the wound margins and base, and the type of exudate (Jones 2005, Phillips et al 1998) in the wound and on the dressing must be assessed and recorded for monitoring and evaluation purposes. Swabs for culture and sensitivity may be taken if infection is present, but are likely to contain skin contaminants and therefore to be of limited use. Information obtained about the patient and wound will lead to diagnosis of the type of chronic wound (Table 2.2). The wound may be measured across the diameter, or margin traced on a sterile film; photographs can be stored in the patient’s notes, and non-invasive methods such as ultrasound imaging (Rippon et al 1998) used to measure and record wound progress.

Table 2.2 Possible causes and types of ulcer

| Cause | Type of ulcer |

|---|---|

| Impaired venous drainage | |

| Metabolic/endocrine disorder with complications of neuropathy | Neuropathic ulcer |

| Combinations of all three of the above | Mixed aetiology ulcer |

| Persistent mechanical stress | Pressure sore (decubitus ulcer) |

| Malignancy | Rodent ulcer, fungating wound |

| Genetic disorder, e.g. sickle-cell anaemia | Ulcer |

Assessment tools for chronic wounds should be used only for what they are designed to do; the Wagner classification is for diabetic ulceration and has shortcomings (Armstrong & Peters 2001). Staging systems for pressure ulceration include risk assessment (Royal College of Nursing 2001). Diagnosing the cause of ulceration (e.g. ischaemia, malignancy) is essential to direct management of the patient, the peripheral tissues, the wound margins and the base of the wound (Romanelli and Flanagan 2005).

Pathogenesis of chronic wounds

This is a developing and exceedingly complex area, involving many body systems and tissues that are also affected by the underlying medical disorder (Hoffman 1997, Renwick et al 1998). These include the immune system, the nerve system, the vascular system (Wall 1997), and the nutritional status (Lewes 1998), physical mobility and mental agility of the patient.

However, in general terms, the tightly controlled sequential process of normal inflammation is disrupted and out of sequence in chronic wound healing. Furthermore, the various phases of wound healing can occur at the same time in the wound. Chronic wounds are frequently colonised by bacteria, and healing can be delayed through infection when the bacteria present begin to have a pathological effect on tissue.

Management of chronic wounds

The primary aim of management is to prevent the development of chronic wounds, as these are painful and distressing for the patient and are costly to manage (Bale et al 1998). Early identification of skin change is therefore essential, requiring the patient and clinician to be aware of the skin, and the patient to be armed with knowledge of what to do. This will include avoiding extremes of temperature or wearing ill-fitting footwear, avoiding going barefoot, wearing protective clothing around the feet and legs when gardening or shopping, as well as ‘first aid’ knowledge of how to clean and dress wounds (Box 2.1).

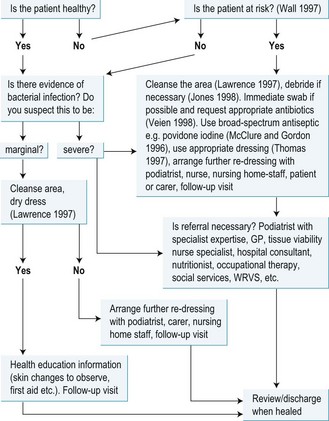

Box 2.1 A suggested protocol for the treatment of bacterial infections of the skin

It is essential to recall that the patient’s general health and drug therapy may inhibit an inflammatory response to infection, so the practitioner must be alert for other evidence of infection such as increase in exudate, smell of exudate or increase in pain. If infection does occur, systemic antibiotics may be used (Sheppard 2005), with particular care being paid to tissues of bacterial resistance, biofilm information (Hardy 2002) and the presence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). There is controversy about antiseptic use (Drosou et al 2003); antiseptics can have a cytotoxic effect on tissues (Enoch & Harding 2003) and affect microcirculation (Langer et al 2004), although there is increasing use of povidone iodine and silver sulphadiazine.

Management of chronic wounds is primarily according to the aetiology and site. Sites of increased mechanical stress must be protected and offloaded with padding, orthoses, footwear adaptations or scotch cast boots and, if necessary, bed rest. Compression is a key issue in managing venous ulcers (Royal College of Nursing 1998). Wound and protective dressings take up space in footwear and this must be accommodated for to avoid further and different problems. Generally, the patient should be encouraged to rest with the limb raised as often as possible, avoiding overloading at risk sites, and if necessary hospital admission arranged. This advice needs to be adapted for each patient; elevating an ischaemic limb may not be tolerable, or indeed appropriate, in every case.

If a wound does develop, then the information outlined in the section under bacterial infection should be employed (Box 2.1). Additionally, slough (soft, yellowish, stringy, sometimes shiny, dead tissue) or necrotic tissue (hard, black dead tissue) should be debrided to allow healing to occur (Bale 1998). The podiatrist may achieve this through careful use of a scalpel and non-touch technique and/or with dressings designed for this purpose (e.g. hydrogels, dextranomer beads or larval therapy (Bale 1998). Occasionally, bony sequestrae (loose fragments of bone) may be present and require removal, possibly surgically. Callus and corn tissue should be removed (Jones 1998) and possibly mobilisation of joints undertaken to adjust tissue loading (Springett & Greaves 1995).

Chronic wounds change with time, and management should change accordingly. For example, if copious exudate is present a highly absorptive dressing (e.g. hydrocolloid wafer) would be used, but when the wound changes to produce little exudate a low-absorption dressing (e.g. alginate) would be selected. Controlling maceration is important to prevent tissue excoriation and further complications, including infection (White & Cutting 2004). The range of wound dressings is vast (Thomas 1997), some being available on the drug tariff while others may be purchased through the pharmacist. Each dressing has specific information about use, removal and re-dressing. Other treatments include grafting and cultured dermal grafting (Falanga 2005), use of growth factors (Graham 1998), long-term use of antibiotics, possibly antiseptics (Drossu et al 2003), therapeutic ultrasound (Hart 1998) and low-level laser therapy (Halery et al 1997).

Patients may need to be seen daily or at intervals appropriate to the management needs, according to the nature of the wound, dressing used or whether they are re-dressing the lesions themselves. It may be necessary to involve the help of the district or practice nurse, or refer for specialist advice from professional colleagues, including podiatrists, physiotherapists, nutritionists, a tissue viability nurse specialist or a doctor.

SCARRING

During the post-injury healing process (Dealey 2005) collagen is laid down by fibroblasts, creating a relatively avascular seal. Wounds healing by first intention will usually leave minimal scars, while those healing by second intention will develop noticeable scars. In chronic wounds, the prolonged, abnormal activity of fibroblasts (Phillips et al 1998) and abnormal sequencing of growth factors usually lead to marked scarring, such as the atrophie blanche seen in healed venous ulceration.

Scarring on the dorsum of the foot causes little problem unless it adheres to underlying tissue. Plantar scarring can produce discomfort, as scar tissue does not have the biomechanical characteristics of normal skin.

Very gentle, superficial massage (Field et al 1998) with essential oils (Baker 1998) can provide some relief and reduction in tissue adhesion. Use of ultrasound (Hart 1998) and low-level laser therapy (Halery et al 1997) can help with collagen realignment during wound healing and even in an established scar.

Keloid is a much raised prominent scar which involves adjacent tissues and is seen in black skin ten times more frequently than in white skin.

Hypertrophic scarring is broader than normal scars and elevated above the surrounding skin; it is red, sometimes painful and sometimes with contracture. Keloid or hypertrophic scarring may be excised, but often recurs following surgery. Sub-scar injection of a corticosteroid can reduce pain; electrostimulation and compression with a silicone sheet or polymer gel can help with pain and minimise scarring. Skin grafts may be undertaken (Fowler 1998).

BURNS

The skin can be damaged through thermal, photo and chemical burns. Thermal injury can be minor to severe according to the depth of tissue damage and the percentage of surface area injured. Superficial burns involve only the epidermis, while partial thickness burns extend into the dermis. In full-thickness burns, the epidermis and dermis are destroyed, and muscle and bone may be involved.

Boiling water scalds and accidents with hot water bottles are frequent causes of burn injury to the foot, particularly when heat injury is not perceived because of neuropathy or if sleeping tablets are taken. The skin may blister, and this will take differing times to heal according to the depth of injury and the patient’s general health. Sunburn can cause severe immediate effects of pain and blistering, as well as long-term skin malignancy (Gnaidecka & Jemec 1998).

First aid for burns is to apply cold to the area, and to keep it cool and covered to minimise risk of bacterial infection. There are various proprietary products available for relief of symptoms. Severe burns will require hospital treatment. Wound contracture after burns is a serious complication, and massage (Field et al 1998) with use of snug-fitting compression with polymer gels can help. Low-level laser therapy and therapeutic ultrasound may also be beneficial.

Chemical burns usually arise through spillage and inadvertent contact with the substance. This requires immediate irrigation of the site with water, hypertonic saline solution, buffer solution or neutraliser (if the burn chemical is acidic use an alkali such as sodium bicarbonate; if alkali, use a weak acid such as vinegar; if phenol, use glycerine). If burning is severe, hospital treatment will be required.

ATROPHY

Atrophic skin lacks nutrition owing to a poor blood supply due to a systemic or peripheral disorder, or to a lack of nutrient intake because of poor diet or malabsorption syndromes. Atrophic skin is thin, mechanically weak and has poor viability (i.e. if it is damaged it will heal slowly, if at all). Nails usually show changes due to atrophy.

Management includes identifying and managing the primary cause, perhaps with referral. Otherwise, prevention of skin injury is paramount, with health education for the patient about management of injuries, for example cleaning the wound, dressing with a clean or sterile low-adherent gauze and, if severe, seeking help from a suitably qualified healthcare professional (Box 2.1).

CHILBLAINS AND CHILLING

This is a seasonal, vasospastic condition affecting the young and old; generally the mid-age group is less affected (Cribier et al 2001) (Case study 2.1). This cold injury, when resolving, may be mistaken for unusual callus or old blisters. There may be an underlying medical condition complicating the problem, such as systemic sclerosis.

CASE STUDY 2.1 HOW CHILLING CAN LEAD TO TISSUE ATROPHY AND SCARRING

A female patient in her late sixties had been prone to chilblains all her life. Each winter brings a return of painful chilled feet. On most toes there are scars and there are tailor’s bunions from prior episodes of long-term chilling and chronic inflammation. Her general health is good and she does not have predisposing factors such as systemic sclerosis. At the time of her visit to the podiatrist the weather was warm and her feet had patches of hard, scaly skin with slight cyanosis, and there were brown speckles on the skin at the old chilblain sites.

In chilling, the blood vascular system is abnormal, with prolonged vasospasm after exposure to cold and change in blood rheology – flow characteristics (Ryan 1991) – thus tissue perfusion with oxygen and nutrients, and metabolite removal is poor. Chronic inflammation occurs instead of the tightly controlled sequential process of inflammation, so repair and resolution is disrupted. ‘Out-of-sequence’ events occur and for an abnormal duration; for example, fibroblast activity (Phillips et al 1998) will be prolonged with a consequent increase in collagen deposition, giving the clinical appearance of scarring.

Scar tissue is relatively avascular and does not have the mechanical (viscoelastic) behaviour of normal skin, and is thus less able to withstand further mechanical stress and becomes injured more readily. The patient is always concerned that each podiatrist she consults recognises these skin changes, that they are not mistaken for callus, and attempts made to remove it result in bleeding, sometimes with slow healing and occasional infection. There is little in the literature to provide evidence of good practice to help manage the condition. Development of clinical guidelines such as these are resource-intensive (Feder et al 1999). However, lack of evidence should not stop the use of empirical methods, the use of which over time has been demonstrated to have some success (Ryan 1998).

The most important treatment for the patient was the prevention of chilling, which was achieved by avoiding extremes of temperature, using thermal/insulating insoles, offloading mechanical stress at vulnerable points, and wearing footwear large enough for thicker socks in winter.

When chilblains did develop, it was important to encourage the inflammatory process to maintain its normal sequence and to have each phase as short as possible. Various treatment modalities were considered and a proprietary anti-chilblain preparation was selected so that it could be purchased easily by the patient.

Chilblains occur most commonly in the winter, and are about 2 cm in diameter, are usually discoloured and may itch or be painful. The discoloration changes according to the stage of the chilblain. Initially the area of cold damage is white due to vasoconstriction (Ryan 1991). Later, following delayed vasodilation and consequent tissue damage, the site shows a bright red (erythematous) inflammatory reaction. A few hours later the site becomes swollen and bluish (cyanotic) with prolonged vasodilation. As the lesions resolve over days to weeks, the skin may wrinkle, look shiny and scale. If the chilblain site is traumatised the lesion may become broken and take some weeks to heal.

Chilling or tissue damage from cold may result in extensive areas of the foot being affected, with similar changes occurring as in chilblains that are localised.

Management requires minimising exposure to extremes of temperature and rapid temperature change, minimising mechanical stress and arranging for an optimal healing rate to be achieved. Insulating footwear may need to be a size bigger than normal; adding insulating materials to footwear also requires sufficient space, otherwise the tissues will be constricted, depriving them of local blood flow, which will make the situation worse. Topical preparations can be applied according to the ‘stage’ of the chilblain; a cooling, soothing preparation (e.g. witch hazel) can be used to control the inflammatory response in the erythematous stage. In the cyanotic phase, a rubefacient (e.g. weak iodine solution, but check for allergy, or tincture of benzoin) may help to stimulate superficial blood flow. Homeopathic and herbal preparations (Kerschott 1997) such as calendula and peppermint oil can help at any stage, along with very gentle superficial soft-tissue massage (Baker 1998) (except in the case of broken chilblains). There are various proprietary chilblain creams, containing active ingredients such as methyl salicylate or capsaicin, aimed at dealing with the chilblain in all its phases. When the chilblain is broken it is essential to keep it free from infection and to protect tissues from mechanical stress by using padding and suitable dressings. In the past, ichthammol was used to optimise healing, but is rarely used today. It is not clear whether therapies such as ultrasound and low-level laser therapy have a helpful role in managing chilling or at which stage they may be most useful.

INFECTIONS AND THE SKIN

In health, the skin has very effective mechanisms for keeping infection (bacterial, viral, fungal) (Freinkel & Woodley 2001) out of the body, both through the primary skin barrier at the base of the stratum corneum and through the immune system. Bacterial and viral infections of the skin can develop if there is a break in the skin (wound) or if the pathogen is able to penetrate the skin barrier. Wounds are frequently colonised by bacteria, and are said to be infected when these microorganisms exert a pathological effect (Hardy 2002). Ulcers are chronic wounds that fail to heal in the expected time (Phillips et al 1998), and bacterial infection is one of the common causes of delayed healing. The very elderly and malnourished, those with a systemic disorder such as rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes mellitus, or those whose drug therapies affect their immune system are particularly at risk of infection.

Fungal infections (e.g. tinea pedis) may have a secondary overlay of bacterial infection, and vice versa. Parasites (Swinscoe 1998), such as fleas and ticks in temperate climates, and jigger worm and tumbu bug in tropical areas, cause itching, and the bites and burrows can become secondarily infected (see Ch. 7). Bacterial and viral infections are discussed below, followed by a section on parasites. Mycotic infections are covered elsewhere in this chapter.

Bacterial infections

Systemic bacterial infections

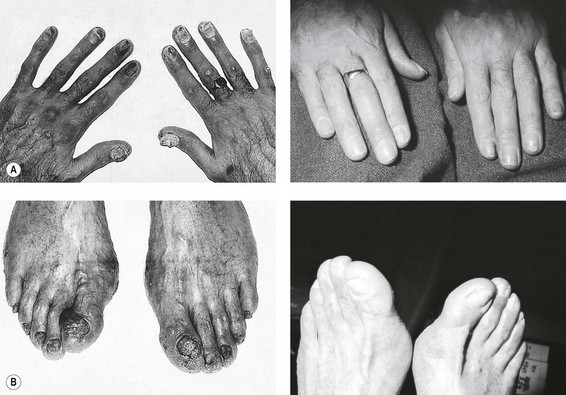

Systemic bacterial infection (septicaemia) can cause marked generalised erythema (redness), pruritus (itching) and scaling (scalded skin syndrome) (Fig. 2.2) in the skin. Deep, localised and spreading infection (cellulitis) will show similar skin changes and pain (Humphreys 1999), perhaps also with lymphangitis (red lines of inflamed lymphatics) and lymphadenitis (lymph nodes inflamed).

Common skin bacteria and resultant conditions

The most important skin pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus and beta-haemolytic streptococci (Hardy 2002). Staphylococcus aureus generally forms demarcated yellowish pustules due to the formation of a fibrin wall in the periphery of the involved area containing the pus (Veien 1998). Beta-haemolytic streptococci cause erysipelas and spread rapidly; infected wounds show an eroded margin and liquid, transparent, straw- to yellow-coloured exudate due to bacterial production of enzymes such as hyaluronidase (Veien 1998).

Bacterial exotoxins can cause skin diseases (e.g. impetigo, erysipelas) (MacKie 2003). Bacterial superantigens and proteolytic toxins can sustain cutaneous inflammation through attenuation of T-cell responses (Leung 1998), and are important in skin diseases such as eczema and atopic dermatitis. Corynebacterium minutissimum, which causes erythrasma (moist interdigital fissuring), is particularly associated with sweating and is therefore treated primarily by controlling sweat. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which produces a greenish pigment that discolours the skin and dressings (Veien 1998), and Proteus species are the chief Gram-negative bacilli in feet. These latter pathogens are especially prevalent with occlusion, and cause skin damage by releasing powerful proteolytic enzymes. All these pathogens may be present in chronic wounds.

Features of cutaneous infections

Cutaneous bacterial infections (Hardy 2002) have different features according to the infecting pathogen and the health of the host. People who are immunocompromised, immunosuppressed or who have poor peripheral vascular supply and/or microcirculation will have a subdued response to infection and will show lessened or few signs of inflammation. People with disorders such as diabetes mellitus are particularly susceptible to infection (Jude & Boulton 1998) owing to the multisystem effects of these conditions. It is important to assess the patient, obtain the history and carry out relevant tests to help with diagnosis and prognosis (Wall 1997).

The degree of inflammatory response (redness, heat, pain, swelling), features of the lesion, and the nature of any exudate provide clinical diagnostic indicators of the pathogen. It is worth looking at and noting the smell, the nature and the volume of exudate of the wound bed as well as that of the exudate on the dressing (Lawrence 1997).

It is essential to be aware that infection may be present when clinical features are inhibited through disease processes or effects of therapeutic drugs such as steroids and that infection will delay healing.

Management of bacterial infection in the skin

The algorithm shown in Figure 2.3 helps with decision-making in the management process. The patient should contribute to the development of a management plan, which is specific to each individual (Hayry 1998).

Optimal management of bacterial infections requires a cost-effective approach coupled with prompt management to give speedy resolution of the problem in order that the patient’s distress is minimal. Waiting for microbiological swab results (for culture and sensitivity) may not allow this ideal to be met. Prescription and use of a broad-spectrum antibiotic (Table 2.3), and perhaps a topical antiseptic, while awaiting the laboratory report (culture and sensitivity) and selection of a specific antibiotic is necessary. Bacterial resistance (e.g. to MRSA) is a major problem today (Dealey 2005, Sheppard 2005). Bacterial resistance to antiseptics has also been reported (Irizarry 1996, Leelaporn et al 1994, Littlejohn 1992), and if using an antiseptic it is necessary to ensure that a sufficient volume of antiseptic is applied and that re-dressing is frequent enough to maintain a bactericidal environment in any wound. Antiseptics can delay healing (Cameron & Leaper 1987) and are probably applied most appropriately only when infection is present (Springett 1989).

Table 2.3 Antimicrobials currently in use for bacterial infections of the skin (Lawrence & Bennett 1992, Veien 1998, BNF)

| Infection | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Staphylococcus species e.g. impetigo, cellulitis |

|

| Streptococcus species, e.g. infected ulcer | Systemic antibiotics: penicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, phenyloxymethylpenicillin |

| Beta-haemolytic Streptococcus, e.g. infected burns | Systemic antibiotics: phenyloxymethylpenicillin |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Systemic antibiotics: ciprofloxacin, ticarcillin + clavulanic acid, azlocillin, piperacillin |

Viral infections

Systemic viral infections can cause skin changes, such as HIV and Kaposi’s sarcoma, and Coxsackie virus (chickenpox) and papular, urticarial (itchy) rash. The skin can also be infected by viral organisms such as molluscum contagiosum, which is usually seen in children, herpes simplex (cold sores) and the human papilloma virus (HPV), which causes warts. Generally, viral skin infections are difficult to treat and a number of different strategies may be employed, including medicinal plant extracts (Abad et al 1997). Molluscum contagiosum is treated by topical application of iodine/povidone iodine and keeping the child separated from others to minimise the potential for spread. Herpes simplex outbreak is treatable with aciclovir, a topical anti-inflammatory and low-level laser therapy. Information relating to warts is given below.

Verrucae/warts

There are a number of human papilloma viruses (HPVs), which cause different clinical features and infect different body sites (Bunney et al 1992). The virus causes hyperplasia of the stratum spinosum and thus a localised increased bulk of tissue within the skin. Generally, warts affect children of school age, which may be related to frequency of exposure to this ubiquitous virus. Exposure to the virus may be in the communal, barefoot environment of school changing rooms, as well as being the first time that the body has encountered the pathogen. An older person who has recently taken up a sport and uses communal changing rooms may also develop verrucae. The spread of the lesion is impossible to predict as it depends, among other factors, upon the individual’s susceptibility to the virus (Pray 2005).

HPVs causing warts in the foot include:

Clinically there is no need to type the virion, except to note that the management of these lesions is according to the health of the owner, clinical features and any special requirements.

Clinical features of verrucae (warts)

Single plantar wart (verruca)

The patient’s age, lesion site and history will give clues to the viral aetiology. Very new single plantar warts may be mistaken for seed corns or a foreign body in the skin. Established verrucae have a rough, cauliflower-like surface, sometimes with black dots of thrombosed capillaries. Verrucae appear encapsulated in the skin, can appear to push the skin striae to one side and, when pinched, cause a sharp pain (as can a neurovascular corn or a foreign body such as a splinter). Pain can occur with plantar warts, and is usually described as being a throbbing pain when first standing on the foot, or off-loading. The bulk of the wart is palpable and this may give an indication of lesion depth. Regressing warts may show the black dots changing into radiating lines, the area may be more painful and the skin of the wart may change to a slight yellow-orange colour. Restoration of the skin to normal is considered to be an indication of wart resolution.

Management

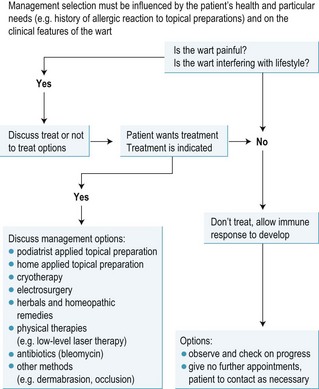

Pain and cosmetic appearance may cause treatment to be considered (Fig. 2.4). Health professionals have an obligation to explain management options to patients and ultimately leave the choice to the patient (Hayry 1998). However, the currently generally held recommendation is to allow the body’s immune system time to recognise the virus and it will resolve spontaneously (Powell 1998), although the timescale may be long. A recent Cochrane Review (Gibbs et al 2003) found from the few clinical studies that could be included that salicylic acid was effective, more so than cryotherapy. The evidence base is still poor and practitioners rely on their experience in the absence of advice. However, certain topical preparations should be avoided (see below).

Almost all wart treatments rely on destruction of the wart tissue with an increased opportunity for the HPV antigen to be presented to the immune system (Powell 1998), and possibly release of nitric oxide analogues/precursors to have an antitumour effect. Sublesion injection of bleomycin is an expensive treatment option (Schuwen & Meigun 1996). After any wart treatment patients must be given advice to remove the dressing if necessary (e.g. pain, suspected infection), have a warm, hypertonic saline footbath for about five minutes, re-dress with a dry dressing, and contact their GP for an urgent appointment (see Ch. 27).

It is medicolegally and ethically essential to ensure that the patient is fully aware of this advice.

Topical preparations for wart treatment

Topical preparations for wart treatment (Table 2.4) include monochloroacetic acid and trichloroacetic acid, which, for therapeutic classification purposes, are termed ‘caustics’. Salicylic acid in strengths from 40% to 75% ointment in white soft paraffin (keratolytic) may be used alone or with monochloroacetic acid in saturated solution. In this case the wart tissue becomes macerated (white, soggy) and hopefully cleaves away from normal skin after one or two treatments. Pyrogallic acid paste is currently less commonly used for treating warts, and has the potential for causing an allergic response and stains the skin brown. Generally all these treatments need to be repeated one to two times a week, and the patient has to keep the dressing on and dry for the duration. Trichloracetic acid may be used alone or usually with silver nitrate (75% or 95%), another caustic which forms a grey/brown/black eschar (scab-like cover). This combination usually requires repeating every two weeks or so, for six or more visits, to be effective. Overenthusiastic application of any of the strong caustics can cause ulceration (see Ch. 16).

Table 2.4 Topical agents for the treatment of plantar warts

| Caustics and keratolytics | Properties/mode of use |

|---|---|

| Monochloroacetic acid | Saturated solution painted on (see Ch. 16) |

| Trichloroacetic acid | Saturated solution as above, but more commonly used as 10% solution (see Ch.16) |

| Salicylic acid | Keratolytic 40%; 60% paste with mask around verruca (see Ch. 16); lesser and varying percentages in proprietary wart treatment products |

| Silver nitrate | 75% and 95%, if moistened too much prior to use will be diluted and have reduced action; paint on perhaps with etching of wart surface with a scalpel or a file first |

| Proprietary products | Contain caustics/keratolytics in various formulations, often with collodion to provide a flexible seal covering the lesion |

| Herbal and homeopathic remedies | |

| Thuja | Tincture is painted on once or twice a day |

| Kalanchoe leaves | Leaves are slit longitudinally with juicy area placed on the verruca. |

| Tea tree oil | Paint on daily and cover |

For home use, there is a wide range of topical proprietary preparations, which should be used as per the instructions supplied with the product. Homeopathic methods include Thuja paint (Chatterjee & Jana 1993) (Thuja tablets are also available, but are outside the scope of podiatry practice to recommend) and herbals such as Kalanchoe leaves and Tea tree oil (Hitchen 1987). Dermabrasion (Chapman & Visaya 1998) may also be used (see Ch. 16).

Electrosurgery

Often this method of treating warts is considered when all else fails, as it entails giving a local anaesthetic, perhaps as an ankle block to avoid plantar infiltration, followed by tissue excision and/or electrodesiccation (Brown 1992) and wound healing. However, it is worth considering early on in the decision algorithm, as it is quick, does not require frequent return visits and postoperative discomfort is usually minimal. Complications include postoperative infection and scarring. This method is probably contraindicated in those whose race characteristics predispose them to marked scarring (see Ch. 16).

CASE STUDY 2.2 VERRUCAE: TO TREAT OR NOT TO TREAT?

A 15-year-old girl had an asymptomatic but large plantar wart (verruca) on the plantar aspect of the third metatarsal joint. The patient had not had warts previously. The medical history and assessment of physical state revealed nothing abnormal, but the patient was due to take a series of examinations over the next few weeks. In addition to these factors, an assessment of the patient’s psychosocial aspects was made, together with recreational commitments and the patient’s reaction to pain. The wart site, size and pain perceived were recorded in the patient’s case notes for monitoring and evaluation purposes.

The option of not treating the verruca was discussed with the patient and her parent, together with an outline of treatment options. These included topical application of caustics of varying strengths (see Table 2.4), dermabrasion (Chapman & Visaya 1998), cryotherapy, electrosurgery (Brown 1992) and complementary therapies such as kalanchoe leaves and Thuja paint.

In view of the impending examinations the patient and her parent elected to have no treatment and to arrange a further appointment if they wished after 3 months (Bunney et al 1992).

Parasitic infestations

As people travel more widely and insects travel with imported goods, so the range of parasites seen has altered. Lice (Pediculosis) can infest different body sites and cause itching where they feed, as can scabies (Sarcoptes scabei) where they burrow in the skin (Smith 1999). Both organisms are visible with a good hand lens and are transferred by close contact with an affected person. The practice nurse, school medical service or local pharmacist will know the current recommended insecticide and have leaflets offering information on prevention of infestation. Skin hypersensitivity may develop through the antiparasitic effect of forms of nitric oxide released by the skin in response to parasitic invasion. Secondary bacterial infection may occur following scratching.

Lumps and bumps and scratches in the skin that have no obvious explanation need to be looked at carefully along with a full history to help diagnosis of parasites caught in tropical climates (e.g. tumbu bug and hookworm) (Swinscoe 1998). Specific treatments are required for each parasite, and it is necessary to investigate these with the help of the GP, pharmacist and literature. Scratching and poor treatment can result in bacterial infection. The best method of management is to prevent infection by ensuring that all washed clothing is thoroughly ironed to heat-destroy larvae, avoiding going barefoot across open ground, etc.

VITILIGO

The abnormal pigmentation in this condition is particularly obvious in dark-skinned people, and as a differential diagnosis is leprosy there may be some concern over the condition. Other differential diagnoses include pityriasis versicolor and postinflammatory hypopigmentation. There is a familial association in this autoimmune disorder. Currently, treatment is reassurance and use of cosmetic camouflage; PUVA may be used.

DISORDERS OF SWEATING

Too much sweat (hyperhidrosis) or too little sweat (anhidrosis) secreted by the eccrine glands in the skin will cause changes in the skin’s mechanical strength. This will give rise, respectively, to moist fissures, usually interdigitally, and dry fissures around the heel. Both forms of fissure may develop complications of superimposed fungal or bacterial infection, especially if the dermis is exposed. With hyperhidrosis there is an increased potential for bacterial infection causing characteristic malodorous feet (bromidrosis). Sweat rash can develop, consisting of tiny vesicles secondary to duct blockage, causing tension and damage in the tissues with a resultant inflammatory response.

Excess sweating may indicate a medical disorder (e.g. hyperthyroidism), while anhidrosis may suggest poor tissue nutrition, perhaps due to poor diet, malabsorption syndromes or peripheral vascular disease (Table 2.5). A previously undiagnosed but suspected underlying medical disorder should be referred for further investigation.

Table 2.5 Causes of anhidrosis and hyperhidrosis

| Some causes of anhidrosis | Some causes of hyperhidrosis |

|---|---|

Symptomatic management of hyperhidrosis includes use of sweat-absorbing insoles, changing and airing footwear frequently, application of astringents (e.g. surgical spirit, potassium permanganate footbaths), antiperspirants (e.g. aluminium chloride) and deodorants. In severe cases, a surgical or chemical sympathectomy may be contemplated, or in severe sweating injections of botulinum toxin (Krogstad et al 2005) can be undertaken.

Symptomatic management of anhidrosis involves restoring normal stratum corneum water content (Potts 1986) by use of emollients and barrier creams, and the application of hydrocolloid wafers (Springett et al 1997) or films. Dry skin and associated itch or stinging may be helped by topical combination formulations containing moisturisers and antipruritics (Yosipovitch 2004) as found in a number of cosmetic bases. Avoiding sling-backed shoes and wearing correctly fitting footwear will reduce tension on skin and hence fissuring. Heel cups of a polymer gel or silicone will maintain heel tissue contours, thus minimising tension stress around the heel margins. Also, transepidermal water loss (TEWL) will be reduced, thus maintaining skin hydration.

FISSURES

Fissures can be moist or dry cracks in the epidermis at sites where the skin is under tension, and may extend to and involve the dermis, with the potential for infection. The fissure usually develops at 90° to the direction of the tension stress (Vincent 1983). The common site for moist fissures is interdigitally and for dry fissures around the heel margins. Systemic and peripheral states that affect skin quality (e.g. peripheral vascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, dermatitis, ichthyosis, psoriasis, tinea pedis) can make fissures worse.

Management requires removal of the cause if possible (e.g. removal of the allergen, treating tinea pedis with an antifungal (Ch. 16)). Optimising epidermal strength is beneficial by controlling the stratum corneum water content. This is achieved by hydrating anhidrotic (dry) skin with emollients or hydrocolloid dressings (Springett et al 1997), or dehydrating hyperhidrotic (sweaty) skin with an astringent (e.g. IMS or an antiperspirant such as aluminium chloride). If necessary, the fissure can be closed with medical-grade acrylic glue, adhesive skin closure, hydrocolloid wafer or strapping. Bacterial infection may complicate this condition and require additional treatment.

CORNS AND CALLUS

Callus (callosity, mechanically induced hyperkeratosis) is a yellowish plaque of hard skin, and a corn is an inverted cone of similarly hard skin (Table 2.6) that is pushed into the skin. Both conditions are associated with excess intermittent mechanical stress (shear, friction, pressure, torsion and tension), which results in abnormal keratinisation (Springett 1993, Thomas et al 1985). These conditions may be painful, and the subsequent antalgic gait can overstress other body structures giving rise to more proximal conditions and effects on lifestyle. Often cosmesis provokes requests for treatment. In those at risk, the presence of corns and callus can predispose to ulceration (Jones 1998). Corns and callus may be present for a number of years, with the mode age of onset being in the sixth decade and slightly earlier for women than men. Corns and callus are rarely seen in those less than 16 years old. Those developing corns and callus when less than 30 years old, as a guide, require foot function to be assessed and managed carefully.

Table 2.6 The different forms of corn and some differential diagnoses

| Type | Site | Appearance |

|---|---|---|

| Hard corns (heloma durum) | Over bony prominences and plantar metatarsal heads (Merriman et al 1986) | Darkish yellow, hard core pushing into the skin sometimes covered with callus, may be mistaken for new warts or foreign body |

| Soft corns (heloma molle) | Interdigital | White soggy mass with indented centre, may be mistaken for tinea pedis |

| Seed corns (heloma miliare) | On areas of weight bearing | Single or clusters of small corns |

| Fibrous corns | Areas taking high load | Long-standing corns tied down to underlying structures, may be mistaken for scars |

| Vascular and neurovascular corns | Areas taking high load, particularly torsion | As for fibrous corns, with vascular elements visibly intertwined in epidermal tissue; painful on direct pressure; may be mistaken for scar or verruca |

Pathogenesis of corns and callus

Excess mechanical stress and duration of loading of tissue during gait at foot–ground, foot–shoe or toe–toe interfaces damages the skin. This may be due to abnormal foot function, such as excess pronation causing overloading of second and third metatarsal heads (Potter 2000). The increased load and duration of loading of the tissues in this area, with the frequently observed abductory twist at toe-off, overstresses the skin (Springett 1993) and this trauma stimulates a local release of growth factors (McKay & Leigh 1991). The stratum corneum is not inert and is capable of releasing growth factors, as do the viable epidermis and dermis, one of the resultant effects being a rapid epidermal transit rate and insufficient time for keratinocytes to mature normally (Thomas et al 1985). The physical and biochemical changes in skin result in callus and corn formation, and slight fibrosis in the dermis with changes in the subjacent microvasculature (Springett 1993). Histologically, callus appears to be in the continuum of forming corns (Springett 1993). Biochemically, the fatty acid content of callus (McCourt 1998) and seed corns (O’Halloran 1990) appears to be similar to that in normal skin. As calloused skin has an altered structure, it is less efficient at withstanding mechanical stress, subjacent tissues can be damaged more easily and so the problem of callus formation perpetuates (Springett & Merriman 1995).

Management of corns and callus

Successful management requires removal of the cause followed by treatment aimed at reducing pain and restoring normal skin function. If there is a biomechanical aetiology, this needs assessing and managing with orthoses and exercises, or surgery. If poor-fitting shoes are the cause, then suitable footwear advice must be given, along with goal-setting and agreement with the patient. For adults, it is important that the inside of the shoe is about 1 cm longer than the foot and there is some space available in width and depth across the ball of the foot and toes. A smooth inside to footwear avoids causing problems such as blisters in the short term and corns and callus in the long term. Heel height may be varied to achieve different foot function to avoid overloading one particular site. A method of attaching the shoe to the foot is best in order to minimise friction and shear stress, but this is not always achievable.

Poor-quality skin may be associated with a medical disorder or poor nutrient intake; if the latter, then referral for dietary advice may be relevant.

Podiatric symptomatic management involves callus reduction and corn enucleation with a scalpel to reduce pain. This dermatological condition is particularly important when the epidermis is glycated (Hashmi 2000), for example in diabetes. Pads, either adhesive or replaceable, can be used to reduce the duration of tissue loading and redistribute mechanical stress, and manage pain (e.g. a holed or U-shaped pad of semi-compressed felt; or a cushion such as a plantar cover of open-cell foam). To absorb shear, orthoses and other devices (e.g. a toe pad of a polymer gel, silicones, tubifoam) may be used. Pads may also be used to change foot function temporarily, to observe the effects before translating to an orthotic device (e.g. a shaft pad for the fourth metatarsal head can be used to change the alignment of this structure against the fifth toe, to treat an interdigital corn between the fourth and fifth toes – see Ch. 16).

Topical preparations (Table 2.7) may be used to reduce callus and corn hardness or bulk, providing there are no contraindications such as poor peripheral tissue status or a medical disorder such as diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis. Some preparations are available as over-the-counter products, as are various callus-debriding devices. Minor surgery (electrodesiccation) can be undertaken to treat corns (Whinfield & Forster 1997). The cavities of well-enucleated corns may be filled with a polymer gel, silicone or acrylic gel (e.g. Viscogel) to discourage further corn formation.

Table 2.7 Topical products* and instrumentation for podiatric use in treating corns and callus

| Topical therapeutic product classification | Example |

|---|---|

| Callus | |

| Keratolytic callus | Salicylic acid (12.5%) in collodion BP |

| Keratoplastic callus | |

| Emollient | |

| Dressing | Hydrocolloid wafer to hydrate skin optimally (Springett et al 1997), polymer gel pad, strapping or fleecy web |

| Corns | |

| Keratolytic corns | |

| Caustic | |

| Dressing | |

| Physical therapy | Low-level laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound |

| Caustic | As above |

| Fibrous corns | |

| Dressing | As above |

| Caustic | Saturated phenol solution as preoperative analgesic (apply for 5 min, irrigate profusely with alcohol to dilute, then operate) |

| Neurovascular corns | |

| Analgesic | Ametop, EMLA creams under occlusion preoperatively |

| Keratolytic | As above |

| Physical therapy | As above |

| Dressing | As above |

* Caustics and keratolytics are contraindicated in those at risk. Some products may contain allergens such as lanolin.

Lesion progress can be measured or traced around, dated and recorded in the patient’s notes. Pain analogue scales are useful. Non-invasive measurement of lesion depth and tissue changes may be achieved using ultrasound imaging (Rippon et al 1998). Data so gathered can be evaluated to provide evidence of the success (or otherwise) of treatments tried for patients generally, thus contributing to the knowledge base of the profession and evidence of best practice.

BURSITIS

Inflammation of a congenital or adventitious (acquired) bursa is termed bursitis (Klenerman 1991). This may be aseptic and acute, infected and acute, or chronic bursitis. The clinical features (signs and symptoms) of inflammation of differing degrees of severity and history (including that of recent changes in footwear) should lead to the diagnosis. Any site that has been exposed to intermittent mechanical stress, particularly shear and friction, is likely to become inflamed, and thus common sites for bursitis include the medial aspect of the first metatarsal head and lateral side of the fifth metatarsal, the dorsal interphalangeal joints and the retrocalcaneal area. Differential diagnosis includes gout, insect bites, rheumatoid nodules, cysts, injury and infection.

There is little in the literature to support the approach to managing bursitis, but this lack of reporting should not be misunderstood to mean lack of evidence for empirical treatments being of benefit to patients (Ryan 1998). Management requires removal of the cause of the problem, so if footwear is the cause then this must be changed to a type that fits the foot and does not rub. Foot function should be assessed for biomechanical abnormality, followed by management (including orthoses and mobilisation (Menz 1998)) to minimise shear and friction at this site, but without overloading adjacent tissues or body segments.

‘First aid’ short-term treatment includes managing pain (Izzo et al 1996) while also recalling the patient’s general health and peripheral status. Anti-inflammatory preparations (orthodox treatments such as topical ibuprofen or complementary therapies such as arnica and calendula) and physical therapies including low-level laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound or footbaths (see Ch. 16) can help in acute bursitis. Chronic bursitis may benefit from a ‘re-sequencing’ of the inflammatory process by use of topical rubefacients (e.g. weak iodine solution), therapeutic ultrasound (but note the proximity of the target tissue to bone) or contrast footbaths (see Ch. 16). Pain and discomfort may be improved with topical agents such as capsaicin (Nurmikko & Nash 1998), witch hazel or aluminium acetate solution BP. Infected bursitis will almost definitely require systemic antibiotics. Occasionally, a sinus may develop and in this case an aseptic technique is essential when debriding overlying epidermal tissue; management is then directed towards creating the optimum environment for healing.

In all forms of bursitis, protection from mechanical stress is essential and may be achieved by changing or adapting footwear, providing replaceable or adhesive protective pads or covering with a polymer gel material that will absorb shear instead of the tissues. In chronic bursitis, ‘tying’ down the tissues firmly with fleecy web or polymer film enlarges the area over which shear, torsion and friction may be dissipated, thus reducing mechanical stress in the problem area. Prognosis is good if diagnosis and management is correct. An aseptic condition will subside promptly, requiring perhaps two or three follow-up visits a few weeks apart, but will recur if the primary cause is not removed.

THE SKIN AS AN INDICATOR OF PSYCHOLOGICAL DISTURBANCE

Some people bite their nails habitually, but picking them to destruction (onychotillomania) may be considered problematic. Cigarette burns on reachable areas of skin should also be observed carefully. Munchausen’s syndrome (repeated fabrication of illness) can take many different forms; a key indicator is either inconsistent symptoms from visit to visit, or symptoms that are inconsistent with the disorder the patient feels themself to have.

Skin disorders may cause psychological problems, sometimes severe (Cotteril & Cunliffe 1997), as the failure of skin in cosmesis and function becomes intimately related to a sense of failure as a human.

THE NAIL IN HEALTH AND DISEASE

The human nail is a hard plate of densely packed keratinised cells which protects the dorsal aspect of the digits and greatly enhances fine digital movements of the hands. Nails are descendants of claws used for digging and fighting, but now only serve as a protection for the digit and to assist in basic behaviour such as scratching and picking up small objects.

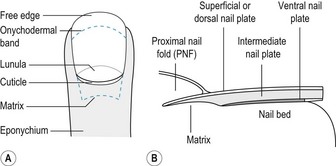

The nail is a flat, horny structure, roughly rectangular and transparent. It is the end product of the epithelial component of the nail unit, the matrix. The nail plate moves with the nail-bed tissues to extend unattached as a free edge, growing past the distal tip of the finger or toe. The nail bed is normally seen through the plate as a pink area due to a rich vascular network. A paler, crescent-shaped lunula is seen extending from the proximal nail fold of the hallux, thumb and some of the larger nails. At the lunula, the nail is thin and the epidermis is thicker, so that the underlying capillaries cannot be seen. It is less firmly attached to the bed at this point and light is reflected from the interface between the nail and the bed, making the lunula appear white.

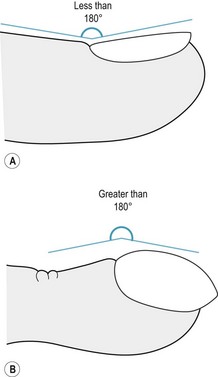

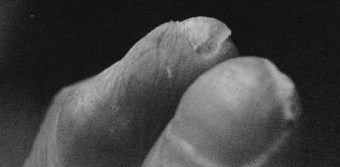

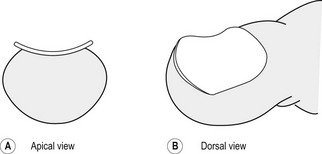

In profile, the nail plate emerges from the proximal nail fold at an angle to the surface of the dorsal digital skin. This angle is commonly called Lovibond’s angle (Fig. 2.5A) and should be less than 180°. Only in abnormal circumstances, for example clubbing, is this angle greater (Fig. 2.5B).

The nail grooves mark the limit of the nail, are separated into proximal, distal and lateral grooves (sulci), and are best seen when the nail is avulsed. The nail plate covers the distal groove situated at the hyponychium, and lying immediately proximal is a thin pale translucent line known as Terry’s onychodermal band (Fig. 2.6).

The proximal nail fold (PNF) is an extension of the skin of the surface of the digit and lies superficial to the matrix, which is deeper in the tissues. It has a superficial and deep epithelial border, the latter not being visible from the exterior. The PNF extends its stratum corneum onto the nail plate as a cuticle, which remains adhered for a short distance before being shed. The function of the cuticle is unclear – it may prevent bacterial access to the thinner and more delicate tissues of the ventral PNF epidermis or it may help in forming a smooth nail surface.

The superficial skin of the PNF, extending from the distal interphalangeal joint to the nail plate, is devoid of hair follicles and is thinner than the dorsal skin of the digit. At the tip of the PNF, adjacent to the cuticle, capillary loops can be seen and, if proliferative, can be associated with certain disease states (e.g. lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, phototoxic conditions).

The ventral PNF is thinner than the superficial PNF; it does not have epidermal ridges and may be the portal of entry for bacteria and/or irritating chemicals, which produce chronic paronychia. It is continuous with the matrix epithelium but has a stratum granulosum that may be differentiated on staining.

Embryonic development and nail growth

The earliest anatomical sign of nail development occurs on the surface of the digit of the embryo at week 9, appearing as a flattened rectangular area. The primary nail field is outlined by grooves, which are the forerunners of the proximal and distal grooves and lateral sulci (Zaias & Alvarez 1968). The nail field mesenchyme differentiates into the nail unit structures, and the fully keratinised nail is complete in week 20 of gestation. Toenail formation usually occurs 4 weeks later than that of the corresponding fingernail.

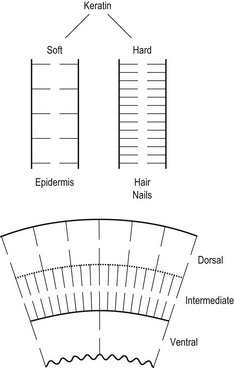

The theories proposed to explain the formation and growth of the human nail have polarised between a single source of matrix production from the lunula (Achten 1982, Norton 1971, Zaias & Alvarez 1968) and a trilamellar structure where, in addition to the lunula, the nail bed and proximal nail fold contribute as the nail plate grows out (Hashimito et al 1966, Jarrett & Spearman 1966, Johnson et al 1991, Lewin 1965, Lewis 1954, Samman & Fenton 1995).

Zaias (1990) stated that the nail plate is a uniform structure produced solely by the matrix, with onychocytes genetically directed diagonally and distally, and not shaped or redirected by the PNF. The proximal portions of the matrix form the superficial nail plate, and the distal matrix forms the deepest portion of the plate. As the nail produced from the lunula is in advance of that from the proximal matrix, this supports the theory that nail plate shape is related to lunula shape. Zaias (1990) also demonstrated a direct relationship between nail plate thickness and the length of the matrix.

However, the exact structure of the nail plate is still disputed, as Achten (1982) claimed that nail embedded in paraffin and stained using the periodic acid–Schiff method (PAS), toluidine blue and the sulfydryl groups reveals three layers with differential staining. The most proximal cells of the matrix form the superficial layer of the nail, while the distal cells form the deeper nail layer, which is thicker (Fig. 2.6). As the nail grows distally and comes to rest on the nail bed distal to the lunula, a thin layer of keratin from the bed attaches to the undersurface of the nail. Achten argued that this keratin does not form an integral part of the nail, but migrates with it, and remains firmly attached to it even when the nail is surgically avulsed. Measurements of progressive thickness of the nail from the proximal lunula to the point of detachment at the onychodermal band have shown that about 19% of nail mass is formed by the nail bed as the nail grows out along it (Johnson et al 1991).

The nail bed has a surface with numerous parallel longitudinal ridges that fit closely into a similar pattern on the underside of the nail plate, thus ensuring a very strong cohesion between the two surfaces.

The three nail layers are often described as the dorsal, intermediate and ventral nail plates, and each is physiochemically different. Seen in transverse and longitudinal sections, the cells of the nail plate are arranged regularly and interlock like roof tiles, with the main axis horizontal. In the superficial layer, cells are flatter and closer together, and in the nail bed they are more polyhedral and less regularly arranged.

It is thought that the layers stain differently due to variations in the composition of the main polypeptide chains and the number of lateral bonds in the keratin molecule (Achten 1982). The more numerous the lateral bonds, the fewer free radicals are available to combine with different stains. In softer keratin there is less bonding, and therefore more staining (Fig. 2.7). Studies on the chemical composition of nails show moderately high concentrations of sulphur, selenium, calcium and potassium.

Blood supply and innervation

In the foot, the nail is supplied by two branches of the dorsal metatarsal artery and two branches of the plantar metatarsal artery, lying at the laterodorsal and lateroplantar areas of each toe. They form an anastomosis at the terminal phalanx, the plantar arteries supplying the pad of the toe and the nail bed.

Innervation of the proximodorsal area of the nail and bed is provided by two small branches from the dorsal nerves (superficial peroneal (fibular), deep peroneal (fibular) and sural), while the medial and lateral plantar nerves provide a medial and lateral branch to each toe to supply the plantar skin, and extend to supply the anterodistal area of the nail bed and superficial skin.

Growth of the nail is continuous throughout life, the rate being greatest in the first two decades when the nail plate is thin (Hamilton et al 1955). The rate of growth decreases with age, and ultimately in the elderly the nail plate loses colour and may thicken and develop longitudinal ridges. The normal development of the nail depends on the matrix and nail bed having an adequate nerve and blood supply, and interference with either will affect growth. Some systemic disorders may cause a reduction or an increase in the growth rate. Other factors that, either directly or indirectly, have a detrimental effect on the development and growth of the nail are trauma, infection, nutritional deficiencies and some skin diseases. Congenital and inherited factors are not common.

Nail growth is continuous throughout life, with peak rates of elongation in the age range 10–14 years and a steady decline in growth rate after the second decade (Hamilton et al 1955); therefore, periodic cutting is necessary, and incorrect performance of this task leads to onychocryptosis (ingrowing toe nail), one of the most painful conditions affecting nails. The free edge of a nail should never be cut so short as to expose the nail bed, but should be cut straight across or slightly convex with all rough and sharp edges smoothed. The overall aim should be to ensure that the nail complies with the shape of the toe.

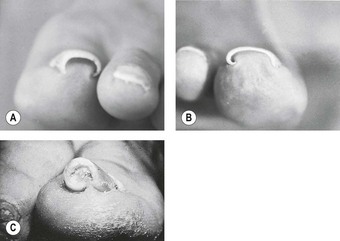

INVOLUTION (PINCER, OMEGA NAIL)

This term describes a nail that increases in transverse curvature along the longitudinal axis of the nail, reaching its maximum at the distal part (Fig. 2.8). Three types of this condition exist (Fig. 2.9), and they produce a variety of symptoms.

Tile-shaped nails often occur in association with yellow nail syndrome, affecting both fingers and toenails. The nail increases in transverse curvature, while the lateral edges of the nail remain parallel (Baran et al 1991). The condition rarely produces symptoms.

Plicatured nails occur where the surface of the plate remains flat while one or both edges of the nail form vertical parallel sides hidden by the sulcus tissue. Toenails and fingernails are affected and the condition causes considerable pain in the foot if the nail is thickened and subjected to shoe pressure, with the development of onychophosis.

Pincer (omega, trumpet) nail dystrophy shows transverse curvature, which ranges from a minimal asymptomatic in-curving to involution so marked that the lateral edges of the nail practically meet, forming a cylinder or roll; hence the names for this deformity. Lateral compression of the nail may result in strangulation of the soft nail bed tissues and the formation of subungual ulceration as the circulation to the nail bed and matrix is reduced. In all stages of the condition, the sulcus may become inflamed and may ulcerate, causing considerable pain.

Aetiology

Although the precise cause of involution is unknown, in toenails it is often associated with constriction from tight footwear or hosiery. In fingernails, an association with osteoarthritic changes in the distal interphalangeal joint has been shown (Zaias 1990), and heredity may play a part, particularly where all nails are affected (hidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, yellow nail syndrome). Some severe cases of involution have an underlying exostosis of the terminal phalanx, which must be excised.

Treatment

In minor degrees, involution produces little or no discomfort and the main consideration is to ensure that the nail is cut so that it conforms to the length and shape of the toe. The in-curved edges, if thickened, should be reduced and advice given about correctly fitting footwear and hosiery.

More severe cases may be treated conservatively with careful clearing of the sulcus and the fitting of a nail brace. This is made from a short piece of 0.5-mm gauge, stainless steel wire which applies a slight upward and outward tension to the nail edges to correct them gradually. The nail must be of adequate length to allow correct fitting of the side arms of the brace, and good contact of the nail plate with the nail bed is essential to allow effective tension for correction.

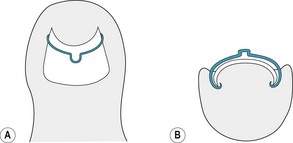

The brace is formed using a piece of wire approximately 1.5 cm longer than the width of the nail. At the middle of the length of the wire, a U-shaped loop is formed in the horizontal plane so that the open end of the loop faces towards the free edge of the nail. With round-nosed pliers, a small hook is made at each end of the wire, lying in the frontal plane and being large enough to accept the thickness of the nail edges. The ends of the wire must be rounded and filed smooth before finally fitting. Each arm of the brace from the hook to the central loop is shaped to conform to the curvature of the nail (Fig. 2.10).

Figure 2.10 Involution. (A) Nail brace in position, dorsal view. (B) Nail brace in position, transverse view.

The brace is applied by engaging each hook over the appropriate edge of the nail, and tension is achieved by closing the long side of the loop as far as possible, without applying so much tension that the nail splits. A light packing of cotton wool and suitable antiseptic (e.g. Betadine solution) may be inserted into each sulcus if necessary. The brace should be kept in position for at least one month and then reassessed for the correction achieved, which is assessed by calliper measurements; tension can be adjusted throughout the period of the treatment.

Other derivatives of the nail brace are now available in plastic and are adhered to the nail directly, exerting tension upwards and outwards because of their preformed shape, or via rubber bands fitted to small plastic hooks. These are reported to be very successful where good adherence is achieved.

Severe and painful involution is likely to require a unilateral or bilateral partial nail avulsion with destruction of the matrix. Where lateral compression causes painful nail bed constriction and ulceration, a total nail avulsion with matrix destruction is the only means of providing relief.

If an underlying subungual exostosis is detected, this needs to be surgically excised (see Ch. 21).

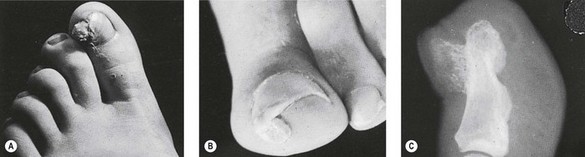

ONYCHOCRYPTOSIS (INGROWING TOENAIL)

Onychocryptosis is a condition in which a spike, shoulder or serrated edge of the nail has pierced the epidermis of the sulcus and penetrated the dermal tissues. It occurs most frequently in the hallux of male adolescents and may be unilateral or bilateral. Initially, it causes little inconvenience, but as the nail grows out along the sulcus the offending portion penetrates further into the tissues and promotes an acute inflammation in the surrounding soft tissues, which often become infected (paronychia).

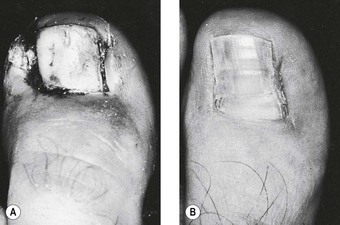

The skin becomes red, shiny and tense and the toe appears swollen. There is throbbing pain, acute tenderness to the slightest pressure and a degree of localised hyperhidrosis. The continued penetration of the nail spike prevents normal healing by granulation of the wound in the sulcus, and a prolific increase of granulation tissue is common (hypergranulation). This excess tissue, together with the swollen nail folds, overlaps the nail plate, sometimes to a considerable extent, partially obscuring it (Fig. 2.11). Because infection is almost always present, pus may exude from the point of penetration in the sulcus and may be seen as a pocket lying beneath the sulcus epidermis or beneath the nail plate.

Zaias (1990) describes three stages of the condition, with individual treatment regimens for each stage:

Figure 2.12 (A) Onychocryptosis with hypergranulation. (B) Same case as in (A), 8 weeks after partial nail avulsion. The nail plate is permanently flattened and narrowed after excision of the involuted nail edges.

Aetiology

The most common predisposing factors are faulty nail cutting, hyperhidrosis and pressure from ill-fitting footwear, although any disease state that causes an abnormal nail plate (e.g. onychomycosis, onychorrhexis) may promote piercing of the sulcus tissue by the nail.

If a nail is cut too short, the corners cut obliquely, or if it is subjected to tearing, normal pressure on the underlying tissue is removed, and without that resistance the tissue begins to protrude. As the nail grows forward, it becomes embedded in the protruding tissue. Tearing of the nails has a similar effect to cutting obliquely across the corners of the nail plate. Both are likely to result in a spike of nail left deep in the sulcus, especially if the nail is involuted. Any spike left at the edge of the nail increases the risk of sulcus penetration as the nail grows forward. Maceration of the sulcus tissue is commonly due to hyperhidrosis in adolescent males but may also arise from the overuse of hot footbaths in the young or elderly. Moist tissue is less resistant to pressure from the nail such as that caused by lateral pressure from narrow footwear or abnormal weight-bearing forces (e.g. pronation, hallux limitus) and as compression forces the lateral nail fold to roll over the edge of the nail plate, the sulcus deepens and the nail may penetrate the softened tissues.

Hamilton et al (1955) showed that the nails of adolescent males increased in lateral width disproportionately to the increase in length of the nail plate. This, together with hyperhydrated tissues, abnormal foot function and/or pressure from footwear may lead to onychocryptosis. However, the relationship between toenail length and width in adolescents has not been investigated further.

Treatment

If the onychocryptosis is uncomplicated by infection, the penetrating splinter may be located by careful probing and then removed with a small scalpel or fine nippers. Extreme care must be taken to avoid further injury to the sulcus and to ensure that a spike of nail is not left deep in the sulcus. The edge of the nail can be smoothed with a Black’s file, although this should be avoided if the nail plate is extremely thin or shows signs of onychorrhexis. The area is then irrigated with sterile solution and dried thoroughly. It should then be packed firmly with sterile cotton wool or gauze, making sure that it is inserted a little way under the nail plate to maintain its elevation. An antiseptic astringent preparation, such as Betadine, is applied to the packing and the toe is covered with a non-adherent sterile dressing and tubular gauze.

It is sometimes necessary to make use of an interdigital wedge to relieve pressure on the distal phalanx from the adjacent toe. In approximately 3–5 days the nail should again be inspected and re-packed, and then again at appropriate intervals until the nail has regained its normal length and shape. If there is associated hyperhidrosis, this requires an appropriate treatment regimen while the onychocryptosis is being treated.

When onychocryptosis is complicated by infection and suppuration is present, it is important to remove the splinter of nail, facilitating drainage and allowing healing to take place. Hot footbaths of magnesium sulphate solution or hypertonic saline solution may be used to reduce the inflammation and localise the sepsis before removal of the splinter is attempted.

Location and removal of the penetrating nail may cause considerable pain and, if there are no contraindications, a local anaesthetic should be given. The injection should be made at the base of the toe, well away from the infected area. After the splinter has been removed, the edge of the nail should be left smooth, and the area irrigated thoroughly with a sterile solution and dried carefully. A light packing of sterile gauze or cotton wool with a suitable broad-spectrum antiseptic agent can be applied and the toe covered with a sterile non-adherent dressing and tubular gauze.

The patient should be advised to rest the foot and, if necessary, to cut away the upper of the slipper or shoe to remove all pressure from the toe. The patient should return the following day for renewal of the dressings, and this must be continued until the sepsis is cleared.

If hypergranulation tissue is present, it may be excised when the splinter of nail is removed, taking care to control the profuse bleeding that often results following excision. Small amounts of granulation tissue may be reduced by repeated applications of silver nitrate, taking care to avoid its introduction into the sulcus.

Following this treatment the prognosis is good, but the patient must be given clear guidance on the predisposing factors so that they can avoid recurrence. If the condition does not respond, it is likely that there is still a small nail splinter embedded in the sulcus, and further careful investigation must be undertaken to locate the remaining piece of nail. Where it is obvious that the onychocryptosis results from a minor involution of the nail, the application of a nail brace will flatten out the nail plate and reduce the involution. If conservative treatment of severe involution does not provide long-term relief, nail surgery will invariably be necessary. This involves partial or complete avulsion of the nail and the destruction of part or the whole of the nail matrix (see Ch. 23).

SUBUNGUAL EXOSTOSIS

Subungual exostosis (Fig. 2.13) is a small outgrowth of bone under the nail plate near its free edge or immediately distal to it. Most frequently, it occurs on the hallux in young people, is slow growing and is a source of considerable pain in the later stages. Trauma is a major causative factor (Baran et al 1991), although this is disputed by some authors (Cohen et al 1973). Repeated trauma, although slight, from shoes which are too short, too shallow or excessively high-heeled, is a common finding in podiatric practice.