Chapter 12 Paediatric podiatry and genetics

Biomechanical anomalies/abnormalities

Congenital and genetic malformations

Postural anomalies/abnormalities

Paediatric podiatry differs from general podiatric practice in that the growing foot provides unique problems and challenges that are not encountered in the adult foot. The simple reason for this is that, not only is the foot subject to local problems due to growth, but it is also required to adapt and compensate for developmental change as the general posture develops through a series of changes affecting the whole skeleton – in particular, from the podiatric point of view, changes that affect the spinal posture, position of the pelvis and the long bones of the lower limb. As the foot supports this structure, any changes that take place produce a ‘knock-on’ effect on the foot, altering its posture, either temporarily or permanently, which can leave it compromised and lead to other pathologies as it attempts to compensate for these changes. Equally, an inherited or acquired problem within the foot can compromise its posture, resulting in changes to the bony skeleton above it. In some instances it may be that both scenarios contrive to compound the situation. The foot can also be affected by the many diseases of childhood, either directly or indirectly, and it is of paramount importance that abnormalities or suspected manifestations of systemic disease are recognised at an early stage and appropriate action taken in order to avoid, reduce or eliminate complications into adulthood. It is, therefore, obvious that, as in the adult foot, the growing foot cannot be considered in isolation from the rest of the body, but unlike the adult foot, where the posture tends to be static, the paediatric foot is in a state of flux as it adapts to change.

Many misconceptions exist related to paediatric foot problems. Unfortunately, foot problems, unless gross or particularly troublesome, traditionally were given low priority, with the result that manageable cases were left untreated and secondary features related to structural pathologies developed. These included chronic intractable plantar keratoses in their many guises, or arthritic states affecting the foot, lower limb and lumbar spine. These problems obviously require treatment, and it is interesting to note that the majority of the elderly population attends a podiatrist, with many requiring hip, knee and foot surgery.

Early recognition and management of actual and potential foot problems in the young would go a long way to reduce these numbers. In an attempt to tackle this problem, successful podopaediatric screening programmes have been established in the past. However, the numbers of elderly currently requiring foot care in the UK have stretched resources to the stage where these services have become a luxury rather than a priority – the result being that actual or potential pathologies easily identified and potentially successfully managed by the podiatrist, but as yet asymptomatic to the patient, are remaining undetected until they become a chronic feature in later life, when palliation rather than cure may be the outcome.

Traditionally, paediatric foot pathologies have been regarded as consisting mainly of verrucae, tinea pedis, ingrowing toenails, corn and callus, and hyperhidrosis/bromidrosis. These conditions do exist commonly and are found often as secondary features associated with structural or functional abnormalities. The misconception that they are the most common paediatric foot problem may be based on the fact that they can be painful, unsightly or antisocial, resulting in treatment being sought. However, the majority of foot problems in the young are inclined to be more subtle and tend to be related to the following broad categories:

These broad headings will either be referred to specifically under their individual headings or be alluded to within the text. However, before considering these, it is important to have an understanding of the normal chronological growth and development of the lower limb, particularly in the early years of life when change can be dramatic and rapid.

NORMAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

In the embryo, the limb buds first appear at about 4 weeks of intrauterine life, becoming segmented into proximal, intermediate and distal parts by the week 6 and digitated by week 7 of gestational age. The thigh, the leg and the foot are recognisable entities by week 9. The feet should reach a nearly neutral position by the end of postovulatory week 11. The positional changes of the feet appear to depend invariably on the skeletal and neuromuscular development.

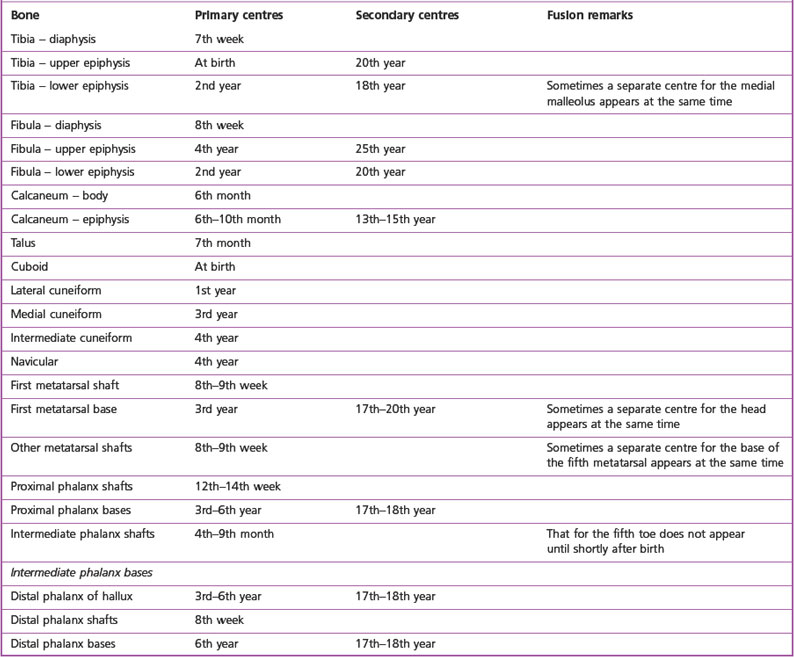

Ossification starts initially in the larger bones of the leg and foot, extending gradually to the smaller bones (Table 12.1). By the completion of the embryonic stage, all the major neural, vascular and muscular parts of the limb are present and in appearance closely resemble those of an adult.

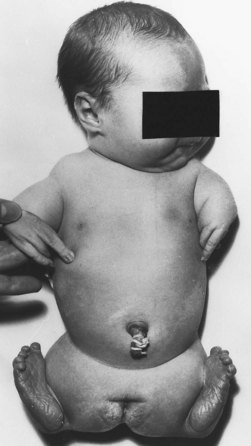

The majority of children are born with normal feet, both structurally and functionally. It seems that the shape, size and form of feet are genetically determined but are liable to being affected by other factors. However, in some children faulty intrauterine morphogenesis may be responsible for deformity and disability. Also, drugs may have dangerous effects on the developing fetus. The most disastrous drug has been thalidomide, which has caused severe limb abnormalities (Fig. 12.1). The thalidomide tragedy has brought about a thorough reappraisal of all drugs prescribed during pregnancy because of their potential teratogenic effects. Later in life, infection, injury and other systemic diseases may be responsible for foot problems. The conditions present at birth are designated ‘congenital disorders’.

Children are not ‘mini-adults’ and the child’s foot is not a small-scale replica of the adult foot. It is comparatively shorter and wider, tapering towards the heel because the hindfoot is less fully developed than the forefoot (Fig. 12.2). As the infant’s foot is very malleable, it may allow some congenital deformities to be corrected easily, although it also means that the foot may be deformed by abnormal stresses of weight bearing. The usual age group of children presenting with foot problems ranges from neonate to pre-school, but it is not unusual for problems to present at a much later stage or to be detected by screening programmes during primary school.

In general, the foot tends to appear short, broad, stubby-toed and fat at birth. It may also appear flat due to fatty padding in the medial longitudinal arch area, but during the first year this is gradually absorbed as growth proceeds. To allow normal growth and development it is important to allow the baby freedom of movement to allow for normal muscle development, and therefore tight bedclothes and constrictive foot coverings should be avoided. During the early crawling and walking stages it is also important to allow barefooted walking to encourage normal function. It is best that children do not wear shoes until they are walking competently out of doors. A child will normally sit unaided by 6–8 months and be crawling by 9 months. Some children never crawl, being ‘controllers’ and provided for by older siblings. Some ‘bear-walk’ on all fours and others ‘bottom shuffle’, but the majority of children crawl in the recognised manner. By 12 months they will walk with assistance, by 15 months independently and be running by 18–24 months. It should be remembered, however, that all children are different and that these figures are governed by relatively wide parameters. The child should be allowed to progress at their own rate and not be artificially stimulated, for example by the use of babywalkers. However, it is prudent to seek a specialist opinion should there be any concern over a child’s development, particularly if the mother who spends more time with and knows her child better than anyone else is concerned, so that she can be reassured or appropriate investigations undertaken.

Knock-knee, bow leg and rickets

During this early period the child walks on a broad base and may appear flatfooted with bow legs, and may show lordosis, with bulging of the abdomen with the legs partly flexed at the knees. The feet may be variously abducted or adducted and apparently ‘flat’. During gait, the child will lean forward with the arms abducted and partly flexed at the elbows, reminiscent of a tightrope walker.

From 2–6 years of age, developmental knock-knee is evident, with the vast majority of cases resolving spontaneously between the ages of 5 and 6 years as growth progresses, and few cases are seen in 8-year-olds. The abdomen becomes less prominent and the foot type and medial longitudinal arch become more evident.

During this period the general posture is constantly changing as the child experiments with their body image and equilibrium. Most of the developmental changes that take place in the lower limb result in compensation within the foot in the form of subtalar joint pronation. It is very important to establish the cause of this, and in most cases reassurance and footwear advice is all that is required. However, it must always be remembered that the cause may be more serious (particularly if it is unilateral), and a full and thorough examination is always undertaken (see Ch. 1) and appropriate action taken. Decisions regarding orthotic management depend on age, severity and assessment of the posture in general.

Rickets

By definition, the cause of rickets is an insufficient intake of vitamin D to promote normal bone growth and to prevent the occurrence of specific abnormal changes in bone. In the UK, a dietary intake of 10 µg/day vitamin D (400 i.u.) is accepted. Toddler rickets presents with bow legs in a child who is already able to walk, with or without other signs as found in infantile rickets (Fig. 12.3). In severe rickets there may be spinal curvature, coxa vara and bending or fracture of the long bones. The treatment of nutritional rickets requires therapeutic doses of vitamin D. The bony lesions occurring in infants and toddlers may be gross (Fig 12.4), but usually complete healing, followed by virtual loss of significant deformity, occurs as the limb doubles in length as growth continues. Residual compensatory foot problems may persist and require ongoing management.

Flat foot

Many young children when first standing appear to have flat feet, as the adipose tissue under the medial longitudinal arch is pressed to the ground, the hollow obliterated, and the foot looks flat. This is not pathological and the parents should be reassured.

Older children very frequently have flattening of the medial longitudinal arch on standing but the arch reasserts itself on standing on tiptoe – this is the mobile flat foot and no specific treatment is needed beyond encouraging the child to practise toe walking and walking on inverted feet. As the limb matures, a normal arch will appear. In severe cases a casted foot orthosis may be required.

Peak rates of growth

Growth continues steadily at varying rates into late adolescence, with peak rates at puberty. The main period of accelerated growth in girls occurs between 8 and 13 years of age, with the peak rate at approximately 12 years of age. The main period of accelerated growth in boys occurs between the ages of 10.5 and 16 years with the peak rate at approximately 14 years of age. Many foot pathologies seen in children, particularly in this age group, are associated in some way with growth, and it is important to be aware of any growth spurts that may be taking place. This age group also tends to be more active physically, putting additional stress on growing tissues. Children under active management by a podiatrist should have their feet and height measured and charted at each visit.

In general, the rate of growth of the feet is constant from birth, increasing by approximately two sizes per year for the first 4 years and then by one size annually thereafter until the mid-teens. Foot growth, however, is very variable between individuals, with some children growing by several sizes in a very short period and others having long periods with no growth, hence the importance of regular measuring when purchasing footwear. It is a noticeable trend that feet are becoming larger, particularly among boys. It is not unusual to find 11-year-old boys with size 11 feet.

FOOTWEAR

The role of footwear in relation to foot deformity is contentious. Some authorities consider that foot deformity, unless inherited, is solely related to the outcomes of compensations related to biomechanical disorders within the foot or general skeleton, while others hold the view that foot deformity can be caused only by an outside influence such as inadequate footwear. It is likely that, given ideal circumstances, factors from both are responsible but, given the multifactorial influences upon the foot, both intrinsically and extrinsically, and the variations in posture, gait and anatomy between individuals, it is possible that a definitive opinion will never be forthcoming. However, it is reasonable to assume that in the early years of life the foot is so flexible and malleable that it can be influenced by outside forces and hence deformity may result. A good example of this is the (now illegal) practice of Chinese foot binding, in which feet were bound in a prescribed position from birth, resulting in a gross, permanent and disabling deformity. In the older foot, where ossification, posture and neuromuscular control are more established, this may be less likely to occur or more difficult to achieve, but it is interesting to consider that in order to correct certain mobile deformities the principles of Davis’ law (Box 12.1) are utilised, in all age groups, by serially encouraging the deformity into a corrected position with appropriate orthotic devices. It could be argued that inadequate footwear does this in reverse or inhibits or negates the action of foot orthoses.

Ligaments and other soft tissues, when placed under unremitting tension, elongate by the addition of new material. When remaining uninterruptedly in a relaxed state they gradually shorten by the absorption of effete material until they come to maintain the same relationship to their attachments as they did before.

Children’s footwear is available in many forms and should always be examined and its suitability considered with every patient. These forms and their associated hazards include:

Figure 12.6 An example of a pram shoe (far left) and other footwear that should only be worn as a short-term measure.

Exceptions include children born with deformity, such as talipes equinovarus, or neurological conditions, such as hemiplegia, where the foot must be artificially maintained in a corrected or ideal posture. In these circumstances, the footwear would be prescribed professionally on medical or podiatric advice.

Inadequate footwear

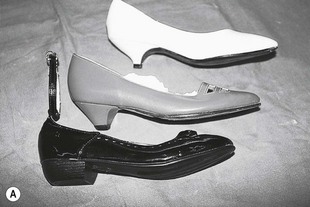

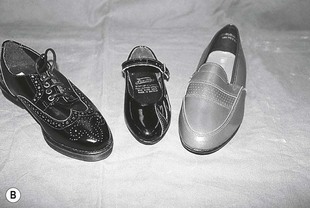

In general, footwear may be inadequate in many differing ways, including being too short, too narrow, having a pointed or a shallow toe box, poor or no retaining medium, inadequate heel stiffener, heel height too high, narrow base to the heel, synthetic uppers and/or lining, or any combination of the above, and not being compatible with the foot it is covering (Fig. 12.7).

Children should always have their feet measured for shoes at a reputable retail outlet by a trained competent shoe fitter. Ideally, both feet should be measured at approximately 2-month intervals and the shoes replaced as required, and not when worn out.

Plimsolls

Ideally, for everyday wear one pair of shoes should be purchased and worn to destruction. This is not always possible for children at primary school in many areas of the UK. In order to keep the schools quiet and clean, some education authorities require plimsolls to be worn in school all day. At the end of the school day the plimsolls are placed in shoe bags on a peg overnight, with the result that they do not dry out fully and are worn again the following school day. In the meantime, the shoes that have been purchased carefully are hardly worn, while the plimsolls at school are not replaced as the foot grows. The growing foot is, therefore, in a constantly damp environment within a shoe, which cannot be fitted accurately and is often too small. Plimsolls are excellent for the purpose for which they are intended (i.e. gymnastics), but do not provide a suitable environment for a growing foot, and this current practice should be discontinued. Furthermore, plimsolls (Fig. 12.8) do not allow for the changing flare of a young foot, and this may have a damaging influence if they are worn continually. They are also unsuitable as a vehicle for casted orthoses.

Figure 12.8 Plimsolls. Note the straight flare, indicated by the straight line through the centre of the heel and sole. In the young child this line should ideally emerge in the lateral distal region of the sole, allowing space in the medial part of the forefoot for the relatively adducted position of the first ray.

Babywalkers

These are included here as they relate to the child who is on his or her feet. As alluded to previously, children walk at different ages, and it is best to ‘let nature take its course’ and allow the child to walk naturally when ready instead of prematurely stressing tissues and loading joints.

Fashion, peer-group pressure and economics

It is important to recognise when managing the case of the teenager that fashion, peer-group pressure and economics play a large part in their social and emotional development, and it is necessary to make compromises regarding footwear or they may be lost as cooperative patients altogether. It is important that the podiatrist working with this age group is acquainted with footwear fashions and costs, to allow them to communicate with the patients at their own level and understand and advise them accordingly.

Trainers

Much has been said regarding the suitability or otherwise of trainers for all ages of children. In some schools, trainers are the only footwear in evidence, particularly as peer-group pressure dictates specific manufacturers. In general terms, trainers are not a problem, so long as, like any other shoes, the criteria for an adequate shoe are followed. The one criticism of trainers, particularly in the age group of puberty where the feet may be very sweaty, is the high percentage of synthetic materials used, leading to a hyperhidrotic state and predisposing to verrucae, tinea pedis and onychocryptosis.

FOOT TYPE

Foot types are many and varied, hence the necessity for children to have their footwear fitted by an experienced, competent fitter with a wide range of styles, sizes and fittings. The infant foot, when viewed from below, tends to be triangular in shape (this is particularly obvious in premature children, who may also be late walkers). As the child progresses into adolescence the foot tends to become rectangular, hence the difference in shape between adult and children’s footwear, the child’s shoe being inflared and the adult’s tending to be relatively straight-flared by comparison (Fig. 12.9). The first ray also tends to be in a relatively adducted position at this age, and it is possible that a straight-flared or small shoe may cause or result in soft-tissue pathologies or digital deformity. Typical foot types include:

Figure 12.9 The ‘ideal’ flare for a young child’s shoe (left) compared with that of an unsuitable shoe (both shoes are for left feet).

These are typically robust foot types common in boys. They can present shoe-fitting problems in girls.

The following foot types can be classified as ‘at-risk’ feet and appear to be more commonly found in females:

All the above foot types can appear singly or in any combination, and can present considerable problems for the shoe fitter.

Low-arched and high-arched feet

Normal feet come in all shapes and sizes and it is important that feet which appear relatively highly arched or low arched due to their inherited architecture are not misdiagnosed as pathological features. There is also the possibility that certain foot types may be the inherited features of different races and cultures.

INFECTIONS

In general, unless the child has an underlying medical condition, which may make them more prone to infection or diminish their ability to combat it, this does not present as a particular problem. Infections are most commonly bacterial, fungal or viral (see Ch. 3).

With the exception of tinea pedis and verrucae, by far the most common ‘paediatric foot’ infections dealt with by the podiatrist relate to nail pathologies, either as true onychocryptosis or paronychia. These conditions can occur in any child at any age but are most common among teenagers and children who are immunocompromised (undergoing chemotherapy) or those with lymphoedema (Turner’s syndrome), where there is an added risk of cellulitis. Aseptic technique is, therefore, a priority.

Infections from foreign bodies and broken blisters can also be a problem.

Onychocryptosis (ingrowing toenail)

The most common nail condition found in children is onychocryptosis, but this tends to be mainly associated with teenagers, particularly boys. However, it can occur at any age and is a particular management problem in very young children and babies who may suck their toes. It is important to remember that in this age group failure of conservative podiatric management could result in surgery either with partial or total nail avulsion, requiring the administration of a general anaesthetic. In this age group, such a procedure is normally carried out without ablation of the germinal matrix and this may result in the possibility of the development of involution or onychogryphosis in later life. It is therefore of great importance that all efforts are made to resolve the problem conservatively. In very young children it is unusual to find a ‘spur’ of nail in the nail sulcus. Apart from the distress caused to the child, unnecessary investigation of the nail sulci using instruments should be considered very carefully and used sparingly so as not to worsen the condition.

Usually the nail plate is found to be triangular in shape, widest distally (as if the nail is too large for the toe), with the periungual tissues hypertrophied, inflamed and fibrosed. There is often no hypergranulation tissue, but there may be evidence of fibrous repair in the area of the lateral nail sulci and a history of long-term antibiotic use.

The condition usually responds to prescription of appropriate footwear and hosiery. With crawlers, it tends to resolve when the child starts walking.

Regular swabbing with 0.5% chlorhexidine in spirit helps to reduce the incidence of infection and helps to ‘tone’ periungual tissues, making them less prone to damage from trauma. The parents are reassured and the child is monitored regularly with advice to seek treatment should the condition deteriorate. Most cases resolve with a little patience.

Some children are born without nails, which grow in at a later date, and management similar to the above may be necessary as the nails ‘erupt’ and grow forward until the corners of the free edge are beyond the pulp of the toe.

Many older children are ‘at risk’ from onychocryptosis due to intrinsic foot abnormalities. In particular, there may be involution of the toenail, hyperextension of the hallux, abduction of the hallux (often with valgus rotation) and subtalar joint pronation (Fig. 12.10). These may occur in any combination, and inadequate footwear and hyperhidrosis may compound the problem.

ANATOMICAL ANOMALIES

These include anomalies of the sesamoid bones, supernumerary bones and tarsal synostoses.

Supernumerary bones

These include os trigonum, os tibial externum and os vesalii.

Abnormalities of sesamoid bones and supernumerary bones rarely directly cause problems in the paediatric foot but may result in soft-tissue lesions. Radiography confirms their presence.

Tarsal coalition (peroneal spastic flat foot)

In tarsal coalitions there is an anomaly of ossification in which adjacent tarsal bones are fused together. Fusion may be bony or cartilaginous. The most common coalition occurs between the calcaneus and the navicular, with union across the midtarsal joint. In a talocalcaneal coalition, fusion occurs between the sustentaculum tali and the talus.

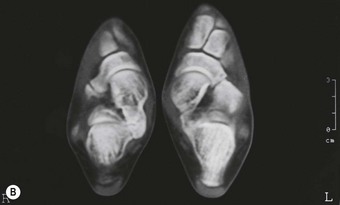

Children with tarsal coalitions may never be aware that they have them. Occasionally, they have distressing painful symptoms and surgery is necessary for adequate relief. Between these two extremes are most children who have little trouble until they enter a growth spurt, when they develop the classic symptoms of the ‘spastic flat foot’. This is a painful contraction of the peroneal muscles and occurs as a protective mechanism, resulting in a fixed, everted, abducted foot, which resembles a flat foot and from which it must be distinguished. Diagnosis is not always easy. Examination reveals tender, taut and prominent peroneal tendons, and attempts to invert the foot will be painfully resisted. Specialist radiographs and/or a computerised tomography scan may be necessary to demonstrate the fusion (Fig. 12.11).

Initial therapy consists of resting the foot in a below-knee plaster of Paris cast if necessary, and reserving surgery for those with recurrent or intractable pain.

Long-term follow-up management with casted foot orthoses may be necessary.

BIOMECHANICAL ANOMALIES/ABNORMALITIES

Acquired deformity

Virtually any pathology is possible. By far the most common, whether due to footwear or as secondary features of compensation for biomechanical anomalies/abnormalities, are digital deformities, including hammer toe, mallet toe, retracted toe, claw toe and hallux abducto valgus (see Ch. 4). The lesser toes may also be variously burrowed in varus positions with lateral and medial deviations at the interphalangeal joints. There may also be early periarticular thickening and limitation of motion.

Deformity at the subtalar joint due to excessive subtalar joint pronation may result in serious forefoot disruption and deformity, and should always be considered as the cause and either corrected or controlled rather than simply treating the secondary digital deformities.

Mucopolysaccharidosis

The mucopolysaccharidoses are lysosomal storage diseases. Mucopolysaccharides (glycosaminoglycans) are complex macromolecular compounds composed of a protein core to which are attached polysaccharide side-chains. In mucopolysaccharidosis IV (Morquio syndrome) the child presents usually at 18–24 months because of gait problems from genu valgum and coxa valga. Contractures of the knees and hips produce a jockey-like stance. The feet are broad and flat (Fig. 12.12). Genu valgum severely impairs gait. Following the birth of an affected child, the parents face a 25% risk that a future child will also have the disease. Prenatal diagnosis and carrier detection with enzyme assays is available.

Juvenile hallux abducto valgus

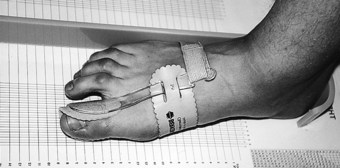

As in many other foot problems, footwear has been universally blamed for this condition in teenagers. In almost all cases, a strong family history can be elicited, with a number of predisposing factors being inherited and, given the appropriate set of circumstances, deformity develops. Footwear may aggravate an established tendency to abducto valgus deformity, and may cause bunion formation by friction over the medial eminence of the metatarsal head. The abducto valgus is often accompanied by adduction of the first metatarsal. Up to 20° of abductus can be normal, but a useful guide to whether surgery is indicated is the position of the sesamoids on a radiograph – no subluxation, no operation. Surgery should not be carried out before the foot is skeletally mature, at about age 14 years. Until then, an orthodigital splint (see Management, p. 295) can control the position of the hallux.

INJURIES

Juvenile hallux rigidus

While not common, this condition causes much discomfort to its sufferers, who are usually teenaged males. It is now thought that the aetiology is recurrent minor trauma or a single incident, which produces a chondral injury. The resulting pain and muscle spasm results in loss of extension at the metatarsophalangeal joint. The patient walks on the outer border of the foot to avoid the painful area. Rest in a cast is the recommended first-line treatment, with a proximal phalangeal osteotomy being reserved for those in whom symptoms persist. Appropriate physical therapy and padding and strapping (see Ch. 16) and footwear advice is usually sufficient to effect a cure.

CONGENITAL ABNORMALITIES

These may arise from two sources: genetic factors, and environmental factors affecting the developing fetus. It is likely that some of these congenital malformations result from a mixture of genetic and environmental factors. Approximately 1 in 50 babies is born with a severe malformation. Malformations are more common in babies born prematurely and possibly in those born to mothers with diabetes. Genetic counselling is vital in the handling of parents whose child has been born with a congenital malformation.

Total correction of some abnormalities may not be possible, and thus residual deformity and handicap remain as a chronic feature in adult life, requiring careful supervision, orthopaedic appliances, and podiatric treatment and monitoring.

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF HUMAN GENETICS

Genetic information is coded in DNA, which is packaged into chromosomes. Each chromosome contains a single DNA molecule consisting of two strands woven together as a double helix. The DNA code on one helix is a mirror image of the other. During cell division, the DNA molecule replicates itself by separating the two helixes and assembling two new double helixes by using the two mirror-image strands as templates. After replication, the DNA is repackaged and the chromosomes are then visible with a light microscope. The chromosomes in one nucleus are shown in Figure 12.13. The chromosomes can then be arranged into a karyotype of matching pairs starting with the largest (numbered 1) down to the smallest (numbered 22). This leaves the sex chromosomes, which are two Xs in a female and an X and a Y in a male. The karyotype of a male is shown in Figure 12.14; it consists of 23 pairs of chromosomes, making 46 in all. When an individual reproduces, only one of each pair will be transmitted to the egg or sperm. Thus the eggs and sperm have only 23 chromosomes and the full complement of 46 is restored at fertilisation.

GENETIC AND CONGENITAL DISORDERS

Many foot disorders have a genetic or part genetic basis, but it is important to recognise that not all congenital (present at birth) disorders are genetic. Some are caused by the adverse intrauterine effects of drugs or infection. Another example is amputation defects that are caused by intrauterine constrictions.

Genetic disorders may be classified according to whether the underlying abnormality is at the chromosome or the DNA level. Some DNA abnormalities in single genes may cause disease, while others work in concert with other genes and environmental effects.

Chromosome abnormalities

Abnormalities of the chromosomes include deletions, duplications and rearrangements of the genetic material. For example, Down’s syndrome is usually caused by having three copies of chromosome 21 instead of two.

Single-gene disorders

Single-gene disorders are caused by sequence changes (mutations) in the DNA of one gene. Depending on whether a gene is situated on one or other of the sex chromosomes it is called X- or Y-linked. If it is on one of the other chromosomes it is described as autosomal. Depending on whether the mutation needs to be present on the copy (allele) of a gene on both chromosomes or only on one chromosome to cause the disorder, it is described as recessive or dominant, respectively. Thus, each single gene disorder has a pattern of inheritance such as autosomal dominant or X-linked recessive. Each inheritance pattern is associated with predictable recurrence risks for relatives. These patterns of inheritance are illustrated using animated diagrams (University of Glasgow 2009).

Multifactorial disorders

A complex interaction of multiple genes, each of minor effect, can work together with environmental factors to cause multifactorial disorders such as talipes equinovarus. At present the genetic and environmental components of this disorder are unknown, but twin and family studies reveal the influence of genetics.

SYNDROMES

Genetic disorders may affect any organ system and a condition might have multiple component features. Recognition that these component features are interlinked (i.e. are a syndrome) is crucial for clinical management. Problems can arise when individual specialists concentrate on single components and no one sees the whole picture. The process is not helped by the variability of many syndromes. The classic textbook descriptions are rare and most patients do not have ‘a full house’ of clinical features. Syndromes may be caused by single gene, chromosomal, multifactorial, environmental and unknown factors. A major problem requiring the expertise of the medical geneticist is where apparently similar syndromes have different genetic or non-genetic aetiologies with very different recurrence risks for the family.

The lower limbs

Examination of the musculoskeletal system should commence with observation of the infant or child. The position of the limbs and the gait may give a clue to a problem that is later confirmed on more detailed clinical examination. Having inspected the lower limbs of an infant for signs of dissimilarity in the skin creases, girth, gross abnormalities such as bowing of the legs and length of the limbs, a systemic examination is indicated. Discrepancy in leg length is usually due to muscle wasting or poor development. It may also be due to a neurological problem, but on occasion it is the larger limb which is abnormal due to hypertrophy, lymphoedema or a malformation.

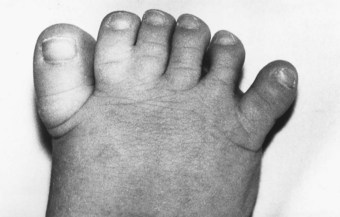

Polydactyly

This term denotes the presence of supernumerary digits attached either to the hand or the foot. On the foot the extra digits may develop from one metatarsal or there may be complete extra metatarsal segments (Fig. 12.15). Depending on the severity of the abnormality, selective ‘amputation’ at an early age is indicated to ensure optimum foot function, thus facilitating shoe fitting in childhood and adult life. As in any operation on the foot, it is vital to ensure that any resulting scar is away from pressure areas.

Syndactyly (webbed toes – zygodactyly)

This term is applied to a total or partial fusion of adjacent digits. It is very common, usually bilateral and often familial. Multiple syndactyly occurs in hands and feet associated with other anomalies, as in Apert’s syndrome (an autosomal-dominant disorder – acrocephalosyndactyly). No treatment is required for webbing (zygodactyly) of the toes (Fig. 12.16).

ASSESSMENT OF A FAMILY WITH A GENETIC DISORDER

Drawing the family tree

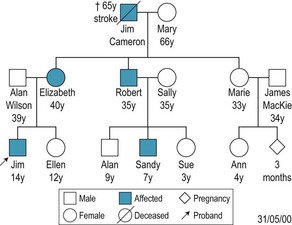

Normally a family will see a genetic specialist after being referred by a general practitioner, another specialist or by a member of one of the professions allied to medicine, such as a podiatrist. The referring healthcare professional may have the genetic basis of a condition brought to his or her attention by the patient, or may find a clinical sign suggestive of a genetic disorder on examination. Once alerted to the possibility of a genetic disorder, even the non-geneticist should draw a family tree. This is done freehand, using a standard set of symbols, which are shown at the bottom of Figure 12.17.

The family tree, or pedigree, is a very compact way of storing a large amount of family information. Each generation occupies the same horizontal level, and within a generation the birth order is presented from left to right. It is usually easiest to start with the youngest generation at the bottom of the page and then work back to the older generations. This may reveal that other persons in the family are, or might be, affected.

In the family shown in Figure 12.17, Jim Wilson was born with syndactyly of toes 2 and 3. Jim Cameron, Elizabeth and Robert are similarly affected, and his cousin Sandy has a milder abnormality consisting of overriding of toes 2 and 3 (Fig. 12.18). In addition, the affected family members all have complete or partial webbing between the third and fourth fingers but no one has any other congenital abnormality.

Interpreting the family tree

In Jim’s family there are affected members in three generations. We can interpret the pattern that links them together in order to try to work out how the gene is inherited and thus an affected person’s risk of passing it on (Fig. 12.19). In this family both males and a females are affected, and so the gene causing syndactyly cannot be on the Y chromosome. There are two instances of a male passing the condition on to a male. Because a male does not transmit an X chromosome to his sons, we can also say that the syndactyly gene is not on the X chromosome. It therefore must be on one of the autosomes. This is called autosomal inheritance.

Figure 12.19 Jim Wilson’s family tree, with chromosome pairs that contain the syndactyly gene. The healthy copy of the gene is marked ‘+’ and the affected copy marked ‘S’.

Looking at the family, it would be extremely unlikely that the partners of affected people (Mary, Alan and Sally) were, by chance, all healthy carriers of the syndactyly gene, and so affected children must have received only a singly copy of the abnormal gene from the affected parent. Because they have developed syndactyly even though they have inherited a healthy gene from the other parent, the syndactyly copy of the gene is said to be dominant to the healthy copy of the gene. The inheritance of syndactyly in this family can thus be said to be autosomal dominant.

OLIGODACTYLY

This term denotes the developmental absence of one or more digits (fingers or toes) with the total absence of all parts of the digit (i.e. metatarsal parts and all phalanges) (Fig. 12.20).

CONGENITAL OVERLAPPING FIFTH TOE (DIGITI MINIMI QUINTI VARUS)

In this condition, from birth the smallest toe lies on the dorsum of the base of the fourth toe in a medially deviated position, although the degree of severity is variable (Fig. 12.21). The condition may be bilateral or unilateral. This is the only common toe abnormality in childhood that requires surgical correction on most occasions in order to avoid trouble with shoe fitting. From about 3 years of age a simple surgical correction allows the toe to return to its normal position. Silicone combined props (see Ch. 17) with a sling to the fifth toe may be beneficial if used from a very early stage on moderate to mild deformity, but surgery is usually required. It is important to manage this condition positively, as disruption of the other lesser digits can occur, with associated skin lesions, in later life.

CURLY TOES

It is normal for the fourth and fifth toes to be a little flexed and curled medially, but if the third toe, instead of being straight, shares this flexed and medial deformity the second toe is usually deformed such that it lies on a higher plane than the others and curls laterally, overlying the third toe. This curious pattern of deformity is very common, being either bilateral or unilateral and variable in degree, but it is seldom a cause of trouble, although tight shoes and socks should be avoided. If the degree of deformity is great the patient will often present complaining of nail pain. However, most cases present for treatment because the parents are concerned due to the unusual appearance of the toes. Digital silicone devices (see Ch. 17) and exercises produce very good results but treatment may be protracted (see Management, p. 296).

Occasionally, a single toe, usually the fourth, is more flexed and adducted than usual, and if it causes pressure on others in the group with the side of the nail discomfort is felt (Fig. 12.22). The toe can be straightened without affecting the growth potential by transferring the insertion of the long flexor tendons to the extensor tendons on the dorsum of the toe. Orthodigital correction with silicone devices and exercises may also be of benefit (see Management, p. 296).

CONGENITAL FLEXED TOE

This is uncommon and may affect a single toe or two adjacent toes. On walking, the affected toe takes the weight on the distal end instead of the plantar surface. Surgical or podiatric treatment is the same as for curly toe. If the condition is ignored, chronic nail problems due to onychauxis or onychogryphosis may arise.

METATARSUS ADDUCTUS

In this less common deformity the forefoot is deviated towards the midline in relation to the hindfoot, as in clubfoot but without equinus or inversion. This is best treated as early as possible with serial, well-padded, moulded plasters until the forefoot remains straight. In a small proportion surgical exploration is needed to release the tight medial tether.

HALLUX VARUS

While this is an extremely uncommon condition in the UK, this is not the case elsewhere, for example in India. Commonly seen with metatarsus adductus, frequently it corrects with growth. Occasionally surgery is necessary for the satisfactory fitting of footwear.

CONGENITAL TALIPES EQUINOVARUS: CLUBFOOT

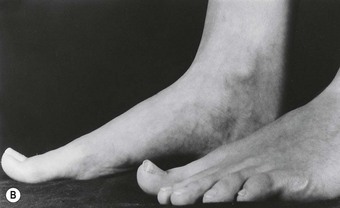

This common deformity occurs in 2–4 of 1000 births; that is, it is about twice as common as congenital dislocation of the hip. The male is twice as often affected as the female, and in half the affected children both feet are deformed. The diagnosis is obvious on inspection, with the deformity being in three parts: the heel is drawn up, the foot inverted and the hindfoot adducted (i.e. in an equinovarus position) (Fig. 12.23). In a small minority the deformity is postural and can be corrected easily by manipulation to neutral and beyond (Fig. 12.24). Repeated manipulation is sufficient treatment. The majority have rigidly deformed feet. In most this is the only problem, but clubfoot deformities are also found in conditions such as arthrogryposis, trisomy 18 and spina bifida cystica.

Initially, the treatment is carried out as an inpatient with daily manipulation of each element of the deformity. The correction obtained each day is maintained with the careful application of a Denis Browne splint to the foot (or feet). As the deformity is overcome progressively, the splint may be bent to hold a greater degree of correction and then connected to the other foot (normal or affected) by a connecting bar to hold the correction more effectively. Over a period of 7–14 days the foot will reach the overcorrected position and the baby can be sent home in the splints. It is necessary to continue to maintain an overcorrection by re-manipulation and re-application of the splints as an outpatient every 2 weeks until the child starts to stand late in the first year. Alternative regimens to hold the correction obtained by manipulation involve the use of Elastoplast strapping or plaster of Paris.

For walking, the splints are discarded and boots with an outer raise to the sole are supplied, with night boots and a corrective bar for night wear. The parents are instructed to manipulate the foot into the overcorrected position. Over the next few years these treatments can be abandoned gradually with a view to the child going to school at 5 years of age with normal footwear and a foot that is slightly smaller and stiffer than usual. If the foot is found to be inadequately corrected during the first year or to be relapsing during later years, a soft-tissue release operation on the medial and posterior aspects of the foot and ankle is needed. About half of the corrected feet will need this procedure, and in a few with severe deformity bony correction will be necessary. In some cases foot orthoses with life-long podiatric management may be required.

TALIPES CALCANEOVALGUS

As the name implies this is exactly the opposite deformity to clubfoot. It is usually the result of in utero posture, in that the foot has been caught in an upturned position with the sole against the uterine wall. The prognosis is excellent, as natural improvement occurs with active movement on release from the uterus. All that is needed is for the mother to manipulate the foot into equinovarus frequently and the deformity resolves permanently within a few weeks. It is important, however, to recognise that this condition is associated in a few with congenital dislocation of the hip and deformity of the tibia.

VERTICAL TALUS (ROCKER BOTTOM FOOT)

This is a rare deformity known by several alternative names such as ‘rocker-bottom foot’ and is primarily caused by a dislocation of the talonavicular joint (Fig. 12.25). It occurs in 10–50% of the trisomy 18 syndrome. Correction is surgical and is planned to reduce the dislocation of the talonavicular joint. In the older child, it is more likely that bony correction or fusion will be needed. Foot orthoses may be required to maintain foot posture.

ONYCHOGRYPHOSIS

Often thought of as an acquired complaint of the elderly, this condition can be congenital – affecting any toe or toes, but usually the first or fifth. It is easily managed conservatively, with the parent/patient being taught how to care for the nails. If the shape of the nail causes trouble and cannot be made tolerable by cutting or filing, radical removal of the nail with phenolisation is indicated (see Ch. 21).

ARTHROGRYPOSIS MULTIPLEX CONGENITA

This name is used for a congenital condition affecting the joints, which may be localised or generalised. The joints may be either extended or flexed but more often the former, with a severe degree of talipes being present. The muscles are atrophic and fibrous, and the skin is tight so that the limbs resemble hosepipes. Arthroplasty has always failed to provide useful movement and the only treatment is to stabilise the affected joints in a good position.

CONGENITAL CONSTRICTION BAND SYNDROME

This may result in the congenital absence of toes. The condition occurs in utero, possibly due to floating strands in the amnion wrapping around the affected part. This can result in amputation of the part if it occurs in early fetal life. Congenital constriction band syndrome presents as ring-like concentric bands, which may be deep or shallow. Deep bands affect lymphatic and venous drainage, resulting in oedema that causes the distal portion to enlarge (Fig. 12.26).

POSTURAL ANOMALIES/ABNORMALITIES

These are considered in the section on examination and assessment (see p. 291), but can be found associated with their individual headings elsewhere.

SURGICAL/MEDICAL CONDITIONS

Leg-length discrepancy

It is important to realise that up to 1 cm difference in true length is considered a normal variation. Also, apparent discrepancy exists where limbs are actually the same length, but because of the alignment of one or the other are functionally different. The effects of leg-length discrepancy are either to cause a compensatory pelvic tilt and secondary spinal scoliosis, or to make the child walk on the toes in order to effectively lengthen the leg. The latter response will, in time, result in adaptive shortening of the Achilles tendon.

The importance of these clinical situations is that they impose abnormal stresses on the foot, particularly on the talus. These stresses in turn may lead to changes in the function and structure of the foot with growth, and it is these that are important for the podiatrist.

Leg-length discrepancy may develop due to a variety of causes. In all but rare events, such as arteriovenous malformation (in which the leg overgrows) or occasionally following acute osteitis, the short leg is the pathological one. Shortening may be due to malunion of a fracture, but this is not a progressive shortening as occurs when epiphyseal growth plates are damaged by trauma or infection. A flaccid (as opposed to spastic) paralysis deprives a limb of the growth stimulus of muscle contraction, and poliomyelitis has in the past given rise to severe leg-length discrepancy. A length discrepancy of less than 3 cm can be dealt with simply by an appropriate shoe or heel raise, but greater deficiencies may be dealt with by:

Hemihypertrophy ranges from enlargement of a single digit to enlargement of one half of the body. Some cases of limb hypertrophy are associated with a widespread haemangioma or lymphangioma (Fig. 12.27).

Linear scleroderma

Linear scleroderma occurs as a linear band of hypopigmentation and sclerosis. The legs are most commonly involved and usually in a unilateral distribution (Fig. 12.28). Growth failure may develop in patients with linear scleroderma, affecting a limb because of atrophy of muscle and skin, which in turn affects bone development. Some children may have combined forms, with linear scleroderma on an extremity and morphea on the trunk.

Localised scleroderma (morphea)

Localised scleroderma is much more common than systemic progressive sclerosis. Morphea usually begins as a circumscribed patch of skin induration, typically on the trunk, feet or other parts of the body. At onset, the skin is oedematous and warm and has a characteristic violaceous border with an ivory centre. As the skin becomes tight and hard over a joint, range of motion may be limited (Fig. 12.29).

Pes cavus

There is a wide variation in the height of the arch of the foot, but when this is seen to be marked and unilateral it must be regarded as pathological. The affected leg is often a little thinner and short, and with the raised arch the foot is often smaller. This condition develops in the early years and it is probable that all cases have a neurological cause, mostly due to minor anomalies of the cord in the lumbosacral region. As occasion may justify, investigation by myelography, magnetic resonance imaging or direct surgical exploration will demonstrate a lesion such as an intraspinal lipoma or angioma. In Friedreich’s ataxia the characteristic is that of pes cavus associated with hammer toes and also scoliosis. Attempts to deal with the fundamental neurological defect are generally unrewarding and are associated with hazard to continence. Accordingly, attention should be directed to the foot deformity, tackling whichever feature is most troublesome.

Sever’s disease (calcaneal apophysitis)

In many ways this disease is similar to Osgood–Schlatter’s disease of the tibial tubercle. The condition troubles children in the age group 10–14 years, with pain at the point of the heel, usually worse during or after athletics. The calcaneal apophysis is tender as the heel strikes the ground, and even on tiptoes is painful due to the pull of the insertion of the Achilles tendon. In half of the children the condition may be bilateral. The diagnosis depends on the history and finding tenderness about the point of the heel. Radiographs are normal. The treatment is simply to restrict activity to a level at which the symptoms are tolerable. Cycling and swimming are useful alternatives to football or netball. An absorbent rubber heel pad to the shoe may cushion heel strike, and in 1–2 years the symptoms will disappear. The affected foot should always be investigated for forefoot/hindfoot malalignment, as this may cause added stress at the insertion of the Achilles tendon and prolong the condition. Appropriate foot orthoses should be prescribed.

In very active children who are actively growing it is not uncommon to encounter Sever’s disease, Osgood–Schlatter’s disease and pain at the insertion of the plantar fascia to the medial plantar tubercle of the calcaneum occurring concomitantly in the same patient. This should be treated with rest and appropriate foot orthoses.

CASE STUDY 12.1 CALCANEAL PAIN

Andrew is 11 years of age and is in first year at secondary school. He is a very active, robust boy, playing rugby, football and tennis. He also has to walk one mile to attend school. When he started secondary school he became aware of how much more active he was during the school day, travelling between class and going up and down stairs. Also, physical education was much more taxing than at primary school. Six weeks after starting secondary school he noted that his right heel, and to a lesser extent his left heel, became progressively more painful as the day progressed. If he stopped his activities for a few days it improved, but would recur when he resorted to his normal level of activity.

He also complained of occasional pain in the arch of his foot after rugby and football.

On examination his feet were functionally and structurally normal for his age but he did have a degree of excessive subtalar joint pronation associated with a forefoot varus deformity. His feet have grown three sizes in the past year and his mother states that he is increasing in height.

Radiographs of his heel were negative but on examination he complained of pain on palpation along the apophyseal margin of the calcaneum and at the plantar, lateral and posterior point of heel strike, indicating a calcaneal apophysitis. Pain was also elicited at the origin of the plantar fascia at the medial plantar tubercle of the calcaneum, indicating an enthesiopathy.

Both symptoms were associated with growth and increased activity. Andrew was advised to rest, given footwear advice, provided with an appropriate functional foot orthosis and heel lift/cushion. He suffers periods of exacerbation and remission associated with his velocity of growth and level of activity, but with treatment and his awareness of his own ‘limit’ of activity he is now predominantly pain-free.

Kohler’s disease of the navicular

An osteochondritis, similar to Perthe’s disease of the hip, Kohler’s disease affects the navicular bone, causing vague pain about the midfoot, and locally the part may be tender. Radiographic findings show changes of increased density and collapse of the navicular. With minimal treatment, with temporary supportive padding and strapping or casted supportive foot orthoses, the symptoms will disappear and the radiographic appearances will become normal in 1–2 years.

Freiberg’s disease

In the capital epiphysis of the second (occasionally the third) metatarsal, osteochondritic change similar to Perthe’s disease may occur, with the head of the bone becoming enlarged and tender. Radiographs show an irregular increase in density and flattening of the front of the head. This may end up with a large square-shaped metatarsal head, which later in life may need excision, but in childhood no specific treatment is needed as symptoms disappear with rest. However, it is often prudent to ‘protect’ the area with appropriate padding and strapping as circumstances dictate. This should involve the use of a 1–5 plantar metatarsal pap with a ‘U’, a 2–4 plantar metatarsal pad, props or dorsoplantar splints. Where there is a forefoot/rearfoot malalignment this should be managed with appropriate foot orthoses – the main objective of all orthoses being to reduce the stresses at the affected metatarsophalangeal joint and maintain it, as far as is possible, in an ideal position functionally.

Stress fracture of a metatarsal (march or fatigue fracture)

As occurs in the upper tibia, an increase in physical activity may stress a metatarsal (usually the second) and produce an undisplaced self-healing fracture. Local pain, tenderness and swelling will be found, with radiographic changes similar to those seen in the tibia. Moderate rest with supportive padding and strapping for a few weeks will result in cure. Some patients may require a walking plaster.

Diabetes

Currently, the incidence of diabetes among children in the general population in Scotland is 25 per 100 000 and in England 13 per 100 000 (see also Ch. 9).

Children with diabetes do not require any specialist podiatric care different from that given to other children, as long as their diabetes stays well controlled and they are free from acquired foot infections such as onychocryptosis. However, it is well established that due to the influence of motor, autonomic and sensory neuropathy as they progress through adulthood, those with diabetes are at risk of deformity, infection, ulceration and gangrene. It is therefore important that all diabetic children should be screened by a podiatrist at yearly intervals in order to detect and manage any digital deformities or biomechanical disorders that may be present and thus reduce the risk of potential pressure lesions that may occur in adult life. This also affords the opportunity to provide appropriate health education. All potential future high-risk groups, including those suffering from childhood cancers, neuromuscular disorders and other endocrine and genetic disorders, including Turner’s syndrome, should be similarly managed.

Poliomyelitis

As a result of the introduction of the live oral polio vaccine used for immunisation, only isolated cases of polio are now seen. The disorder is caused by the polio virus, which spreads from the alimentary tract to the central nervous system, particularly the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord. The problems that arise are due to loss of function and the acquisition of deformity, due to the unbalanced pull of muscles no longer opposed by paralysed muscles. The effects of the disease in the lower limb are seen in the muscles, with weakness of inversion, eversion, plantar flexion of the ankle and also foot drop. Each patient’s problems are individual. Recovery from the disease is often incomplete. Polio is associated with contracture of muscles causing an equinovarus deformity, pes cavus or permanent foot drop. These conditions may require surgical correction, but will demand considerable attention from the podiatrist owing to abnormal load bearing of the foot and the need for special orthoses and footwear.

Spina bifida cystica

This is a congenital disorder in which there has been a failure of the posterior spinal elements. The level in the spine at which the lesion occurs relates in some measure to the effects on the patient, but does not equate with their function. Problems arise in the foot in those with sacral lesions, where an imbalance primarily affects the muscles of the foot (Fig. 12.30).

In the legs, the sensory loss may be extensive, depending on the degree of nerve root or spinal cord damage. The motor dysfunction is largely due to root damage giving flaccid paralysis, but areas of spasticity may be present due to higher cord damage with intact lower cord segments and lower motor neuron function, together with a potential to develop severe deformity. Some problems are reasonably predictable: for example, a common level of lesion about L4 will leave the roots of the femoral and obturator nerves largely intact while the sciatic nerve will be paralysed. As a result, the hip, subject to the pull of flexors and adductors but with no extensor or abductor muscle function, will dislocate. At a lower level, active quadriceps, unopposed by paralysed hamstrings, will produce recurvatum of the knee. The foot may be deformed in any direction, and the loss of the normal weight distribution on the sole of the foot will readily lead to trophic ulceration in the anaesthetic foot.

By a variety of procedures, leg deformity may be controlled and function improved by calliper bracing. Any success in getting the child to stand or walk in some way with various aids depends upon the child’s intelligence, the degree of neurological damage and the possible presence of spinal deformity – none of which is under our control. One factor that may be controlled is obesity, which makes standing and walking more difficult. A wheelchair existence is the likely result in many children, and indeed later many may choose this as an easier way of life. The sensory loss gives way to the problems of trophic ulceration. Any ill-fitting appliance or footwear may initiate this, and the ulcer can be very deep as well as slow and difficult to heal. Trophic ulceration is a much more common problem in the second decade of life than the first. Children with spina bifida should be monitored regularly by a podiatrist and treated, referred or advised as circumstances dictate.

Cerebral palsy

The term cerebral palsy is used to denote a disorder of movement and posture resulting from a permanent, non-progressive defect or lesion of the immature brain. The incidence of cerebral palsy is in the region of 2.5 per 1000 in childhood. The spastic group shows the features of lesions of the pyramidal tracts, such as muscle spasm resulting in spastic postures of the limb. The most common is spastic tetraplegia, in which all four limbs are involved. This group is subdivided into types I and II. In the common type I spastic tetraplegia the legs are more severely involved than the arms. In the much less common type II spastic tetraplegia the spasticity is extremely severe in all four limbs, so that the contractures develop early and disuse muscle atrophy may be masked (Fig. 12.31). As with all of this group of conditions, there is a great need for a team approach to management via all modalities of therapy so that maximum benefit may be gained from each. Inevitably this means that, for the podiatrist, foot care may become a primary treatment.

Muscular dystrophies

The muscular dystrophies are a group of genetically determined disorders with a common denominator of a progressive degenerative process in the skeletal muscles. These have been subdivided into separate entities mainly on the basis of the distribution and severity of the muscle weakness and their mode of inheritance. Many of these children later develop foot problems and may require help from a podiatrist.

CASE STUDY 12.2 RECURRENT INFECTIONS ON THE FOOT

Adam is now 18 years of age. He first presented as a patient at 8 years old, being referred by his general practitioner who was concerned about chronic recurrent breakdown lesions on the plantar aspect of each heel and recurrent toenail infections. Adam has the less common type II spastic tetraplegia, necessitating permanent wheelchair use and transfer by a helper or his mother. His arterial supply was very poor, as was his venous drainage, due to the dependent position of the feet and the lack of development of a competent arterial supply caused by non-use of the lower limbs. This resulted in chilblains during the winter months, with the feet having a permanent purple appearance and chronic low-grade first toenail infections due to the abnormal and involuntary movement of the toes within the shoes. There was a long history of continued antibiotic use in order to overcome and prevent infection in the feet, which was having a knock-on effect on his general health, with several episodes of chest infections requiring hospitalisation. Positionally, both feet were extremely cavus and inverted, similar to a moderate case of talipes equinovarus, and it was noted that his postural position in his wheelchair was poor due to a kyphoscoliosis. This resulted in chronic overloading of his heels, producing ischaemia and hence breakdown. Mum had great difficulty obtaining appropriate footwear in the high street and Adam had never been assessed by a podiatrist.

Initially, the ulcerated heels were treated with appropriate dressings, addressing the problem as one would with a high-risk diabetic patient, bearing in mind that he was only 8 years old. A new, made-to-measure wheelchair was provided, with appropriate spinal, pelvic and thigh support in order that there were no overload areas on the feet in the footrest. Prescription footwear was provided to accommodate the movement of the toes within the shoes and a casted evazote orthosis was provided for the heels. Digital 2–4 silicone props in Otoform-K™ were also provided to control the movement of the second toe over the hallux and nail plate. The nails responded well to conservative podiatry and regular nail care. Home physiotherapy and massage was arranged in order to improve his venous drainage.

Adam has now been under podiatric care for 10 years. During this time his foot posture has deteriorated secondary to his neuromuscular state, but he has had no further foot infections and a chest infection is now a very rare occurrence. He attends on a regular basis, has his footwear and foot orthoses replaced and wheelchair monitored and adjusted as necessary. He is regarded as a priority patient and is seen immediately if he assesses he has a problem.

There are three important messages in this case. The first is that young children with neuromuscular conditions can be at very high risk of foot problems. Secondly, children do not need to be ambulant to require podiatry, and thirdly, podiatry has a very important role in the holistic management of these patients.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Compared with other causes of physical handicap, such as cerebral palsy and spina bifida, Duchenne muscular dystrophy is rare. The condition is due to a sex-linked recessive gene with a high mutation rate. Although biochemical and histological abnormality are present from birth, the disease usually becomes clinically apparent between the ages of 1 and 4 years. The affected child is slow to walk, falls frequently and has difficulty in getting up or in climbing stairs. Rubbery hypertrophy usually occurs in the calves (Fig. 12.32), quadriceps and deltoids. By the age of 10–12 years most patients need to use a wheelchair for life.

Hypermobility syndrome

Generalised joint laxity is a feature of the hereditary connective tissue disorders such as Marfan’s syndrome, the Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and osteogenesis imperfecta. A patient is considered hypermobile if he or she can perform two of the following three manoeuvres:

Hypermobility is relatively common in the general population. The term ‘hypermobility syndrome’ has been coined to define a clinical situation in which there is generalised joint laxity associated with musculoskeletal complaints. In young children this syndrome is observed equally in both sexes, but towards puberty it predominates in girls. The knees are the most frequent sites of complaint but occasionally the ankles may also be affected. The discomfort usually comes after exercise, and the whole clinical picture is consistent with an episode of traumatic synovitis. There is a strong familial tendency to this syndrome and the diagnosis is, therefore, essentially clinical combined with an awareness of family history. The management is largely reassurance as to the absence of serious disease, and activity, which precipitates symptoms, should be avoided if possible. Casted foot orthoses may be of benefit during acute episodes and in maintaining foot posture. Most young subjects will grow out of their complaints altogether.

Ehlers–Danlos syndrome

The disorder is familial and autosomal dominant. The child tends to be slim and underheight, and may have kyphoscoliosis. The hyperextensible joints allow abnormal postures. Genu recurvatum (Fig. 12.33) and pes planus are common. The infant may demonstrate delayed motor milestones, will tend to fall and may sustain recurrent fractures. No specific treatment is available but all foot deformity should be managed as a matter of urgency. Wounds will be slow to heal and will exhibit ‘tissue paper’ scarring.

Limb pain of childhood with no organic disease

So-called ‘limb pains’ or ‘growing pains’ are more common in childhood than all the other rheumatic diseases put together.

Growth in children involves two phases – ‘shooting up’ and ‘filling out’. A limb may show bone growth followed (not accompanied) by muscle growth. It may be that in such a shooting-up phase extra strain is put on the muscle, which tires easily and gives pain towards the end of the day or during the night when relaxation is incomplete. A history of rheumatic disorders is more common in the families of children with limb pains than in the families of controls, and therefore parents often become worried and feel that their child suffers from rheumatic disease. In two-thirds of affected children limb pains occur during the daytime or evening. In the remainder the pains are predominantly nocturnal and can wake the child and may be severe enough to cause crying. The age group mainly affected is 9–12 years – girls more than boys. The children cite pain between joints – suggesting that the pain is muscular. Most children like to have the area gently rubbed by a parent, which effectively excludes acute rheumatism. With reassurances based on discussion, it should be possible to convince parents that their child does not suffer from a rheumatic disorder. Occasionally, children have psychosomatic musculoskeletal pain and should have a full psychological evaluation. Children with limb pain should respond well to treatment directed towards decreasing the pain and restoring function. Foot orthoses have been found to be of use in some cases, particularly where there is an obvious biomechanical abnormality, but care must be taken not to provide a ‘crutch’ that is not necessary.

CASE STUDY 12.3 LIMB PAIN OF CHILDHOOD WITH NO ORGANIC DISEASE AND HYPERMOBILITY SYNDROME

Emma is 7 years old, and since the age of 3 years she has frequently wakened her parents at night, crying and requesting them to rub her legs. This could variably be her knees, outer lower leg, anterior thigh, plantar aspect of the foot and, occasionally, her buttocks. Her mother also gave her Calpol™. Her general practitioner later prescribed ibuprofen, which was taken in the evening before going to bed. Mum could find no pattern in Emma’s behaviour or activities that appeared to precipitate an attack, although she knew that she would most likely be attending to Emma during the night after her dance class or a very long day in town. Her general practitioner initially arranged physiotherapy, which made no difference. Emma was then referred to a paediatric orthopaedic surgeon, who found no abnormality. Finally, suspecting a rheumatic disorder, Emma was referred to a paediatric rheumatologist, whose findings were also negative apart from a diagnosis of hypermobility syndrome.

At this point, when Emma was 5 years old, she was referred to a podiatrist because of her foot pain and the suspicion that the limb pain may be associated with abnormal foot posture resulting in an anomaly of gait and general posture, and hence causing muscle pain in an attempt to achieve ‘normal’ posture.

On examination her feet were markedly hypermobile, with a large degree of forefoot varus and associated excessive subtalar joint pronation. The gait was noticeably apropulsive, with the feet abducted and everted. Advice was given regarding footwear, but this was largely unnecessary as her mother had always suspected that her posture and gait were an issue and had gone to great lengths to obtain the correct footwear. Following subtalar neutral casting and orthotic prescription to control the hypermobility and improve the postural attitude of the foot to the leg and ground, Emma was provided with an appropriate functional foot orthosis and given advice regarding its initial usage. At follow-up 2 weeks later, Emma was pain-free and has remained so to date, with occasional and rare episodes that can be traced to overactivity or unusual activity. She does not get pain after her dance class now and is dancing in competitions.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (juvenile chronic arthritis)

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (see Ch. 8) comprises a heterogeneous group. It may present as oligoarthritis (Fig. 12.34), systemic arthritis, polyarthritis (rheumatoid factor (RF) negative, antinuclear antibody (ANA) positive), polyarthritis (RF-negative, ANA-negative), polyarthritis (RF-negative, ANA-negative), polyarthritis (RF-positive) or juvenile psoriatic arthritis. Involvement of the joints and soft tissues is a common complication of rheumatoid disease; the extent to which they are affected is varied. In the lower limbs the common joints affected are the hip, knee, ankle and the subtalar joint. There is a wide variety of arthritic foot problems, and leg-length differences are not uncommon. The management of these foot problems depends not only on medical treatment of the arthritis but also on local application of specific measures to the damaged foot. Fortunately, there have been great advances in the prescription of orthoses, involving the development of new materials with appropriate properties, and their use in individual patients for each specific abnormality.

Psoriatic arthritis

Juvenile psoriatic arthritis has been defined as a form of chronic arthritis with onset before the age of 16 years and occurring in association with a characteristic psoriatic rash. The onset of the arthritis is often sudden, with the joint being acutely swollen and painful. Toe or finger joints are frequently involved, often with flexor synovitis, giving a characteristic sausage-digit appearance (dactylitis) (Fig. 12.35). A family history of psoriasis also suggests the diagnosis. These very painful digits respond well to silicone digital devices in the acute phase and also as maintenance therapy.

Raynaud’s phenomenon

Raynaud’s phenomenon is prominent in scleroderma. The digits become cold, numb and painful. Local hypoxia leads to cyanosis, resulting in a bluish colour. Raynaud’s phenomenon is best treated by keeping the whole body, especially the hands and feet, warm, and by preventing and protecting the body from cold exposure. Feet, especially toes, should be carefully monitored, particularly through the autumn and winter months, with prevention and early management of problems being a high priority (Fig. 12.36).

Haemophilia

Joint swelling and pain often heralds haemarthrosis, which is the single most incapacitating event in the life of a severe haemophiliac. The correct policy is to encourage the patient to attend hospital at the earliest sign of joint swelling in order that replacement therapy can be given. Where there is joint deformity in the foot, either as a result of bleeding or from some intrinsic primary cause, it is important that appropriate orthotic management is instigated at an early stage in order to limit damage and encourage normal function (Fig. 12.37).

Turner’s syndrome

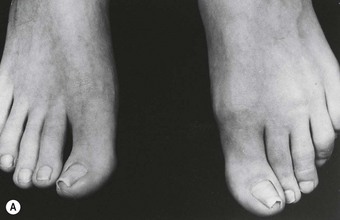

Foot problems such as lymphoedema of the lower limb secondary to poor lymphatic drainage and nail dysplasia are well recognised as valuable diagnostic features in Turner’s syndrome. Affected girls are at increased risk of ingrowing toenails compared to the general population, and this is due to a number of factors in combination. Typically, the girls have short, broad feet with hyperextension of the great toe, involuted toenails and oedematous periungual tissues, accompanied by subtalar joint pronation resulting in damage to the nail plate and surrounding soft tissues. Due to the poor lymphatic drainage, girls with Turner’s syndrome are at increased risk of cellulitis, and thus all cases must be treated diligently and as a matter of urgency (Fig. 12.38).

CASE STUDY 12.4 THE EFFECTS OF TURNER’S SYNDROME ON THE FOOT

Jane was diagnosed with Turner’s syndrome following karyotype testing when suspicions were raised shortly after her birth due to persistent ankle oedema. She also appeared to have no toenails at birth. As a result of her short stature and short and very broad variably swollen feet, appropriate footwear was almost impossible to obtain, with the available shoes being far too long to accommodate the breadth and swelling, resulting in frequent trips and falls. Also, because of involution of the toenails, hyperextension of the first toes, developmental subtalar joint pronation and inappropriate footwear, accompanied by chronic ankle oedema, Jane began to develop ingrowing toenails shortly after she began to walk. This was dealt with initially by appropriate footwear and nail-cutting advice. Girls with Turner’s syndrome have a high pain threshold, and may have behaviour difficulties resulting in toenail picking, which compounded the problem in this case. As she became older, the Turner’s syndrome features in the foot became more pronounced and the ingrowing toenails more marked and persistent, resulting in one prolonged hospital stay necessitating the administration of intravenous antibiotics to combat a severe cellulitis. Due to chronic lymphoedema, Jane was also managed by bed rest and elevation, which made no difference to the swelling as the lymphatic system could not drain fluid as intended. The most appropriate management would have been normal exercise in order to allow the venous system to drain the excess fluid. Following resolution of the infection and a partial nail avulsion with phenolisation, there have been no further serious episodes, due to diligent and immediate podiatric input if a problem is suspected. Jane’s mother has been given advice regarding nail care, contact telephone numbers, oral antibiotics (to be given at the first suspicion of infection) and topical 10% betadine aqueous solution (for children over 2 years old) or 0.5% chlorhexidine in spirit applied on a once-daily basis as prophylaxis.

Down’s syndrome (trisomy 21)

The most significant of the autosomal trisomies is trisomy 21, or Down’s syndrome. The features of Down’s syndrome are usually evident at birth. Classically, the most striking physical abnormalities are to be seen in the face and skull. During the first years of life, hypotonia and laxity of joints are often evident, but these become less apparent as the child grows older. The first and second fingers and/or toes may be widely spaced (Fig. 12.39). Children with Down’s syndrome may have a number of pedal anomalies, including hypermobility with an adducted first ray and severe pes plano valgus compounded by genu valgum, and in some cases they may be overweight. There may also be circulatory compromise, which should be monitored carefully. Down’s children are also prone to psoriatic arthropathy and are unlikely to complain of pain; therefore, diligent examination is important.

Tuberous sclerosis

This is inherited as an autosomal-dominant condition, and 75% of cases have a positive family history. The characteristic features of tuberous sclerosis are mental retardation from birth, and epilepsy starting usually before 2 years of age. The classical clinical triad consists of edenoma sebaceum, and epilepsy and metal retardation. The skin patches found are shagreen patches over the sacrum, ichthyosis, café au lait spots, subungual fibromas (Fig. 12.40), telangiectasia and vitiligo.