Evaluation of Muscle Strength

Purposes of manual muscle testing

Results of assessment as a basis for intervention planning

Relationship between joint range of motion and muscle weakness

Limitations of the manual muscle test

General principles of manual muscle testing

Manual muscle testing of the upper extremity

Scapula elevation, neck rotation, and lateral flexion

Scapula depression, adduction, and upward rotation

Scapula abduction and upward rotation

Scapula adduction and downward rotation

Shoulder abduction to 90 degrees

Wrist extension with radial deviation

Wrist extension with ulnar deviation

Wrist flexion with radial deviation

Wrist flexion with ulnar deviation

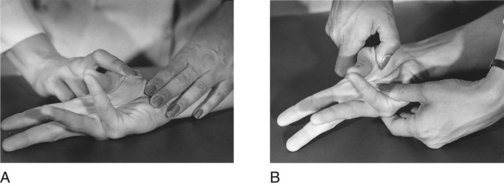

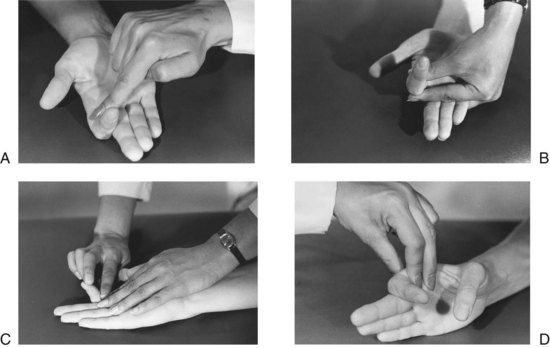

Metacarpophalangeal flexion with interphalangeal extension

Proximal interphalangeal flexion, second through fifth fingers

Distal interphalangeal flexion, second through fifth fingers

Thumb metacarpophalangeal extension

Thumb interphalangeal extension

After studying this chapter, the student or practitioner will be able to do the following:

1 Describe screening tests for muscle strength assessment.

2 Identify what is measured by the manual muscle test (MMT).

3 List diagnoses for which the MMT is appropriate and those for which it is not appropriate, with the rationale for each.

4 List the steps of the MMT procedure in correct order.

5 Describe the limitations of the MMT.

6 Define muscle grades by name, letter, and number.

7 Administer an MMT, using the directions in this chapter, on a normal practice subject.

8 Describe how results of the muscle strength assessment are used in intervention planning.

Many physical disabilities cause muscle weakness. Slight to substantial limitations of performance in areas of occupation, such as bringing food to one’s mouth, lifting a child, removing items from a grocery store shelf, and getting into and out of bed, can result from loss of strength, depending on the degree of weakness and whether the weakness is permanent or temporary. If improvement is expected, the occupational therapist must assess the muscle weakness and plan an intervention that will enable occupational performance and increase strength.

Causes of Muscle Weakness

Loss of muscle strength is a primary symptom or a direct result of the following diseases or injuries:

1. Lower motor neuron disorders, such as peripheral neuropathies and peripheral nerve injuries, spinal cord injury (because those muscles innervated at the level[s] of the lesion generally have a lower motor neuron paralysis), Guillain-Barré syndrome, and cranial nerve dysfunction

2. Primary muscle diseases, such as muscular dystrophy and myasthenia gravis

3. Neurologic diseases in which the lower motor neuron is affected, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or multiple sclerosis

Disabilities in which loss of muscle strength is caused by disuse or immobilization rather than being a direct effect of the disease process include burns, amputation, hand trauma (unless an accompanying nerve injury is present), arthritis, fracture, and a variety of other orthopedic conditions.

Muscle weakness can restrict or prevent performance in areas of occupation, including activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation. These limitations are assessed by observation of performance (see Chapter 20), screening tests, and manual muscle testing (MMT), when indicated.

Screening Tests

Screening tests are useful for observing areas of strength and weakness and for determining which areas require specific MMT.6,10,12,18 Screening tests can help the therapist avoid unnecessary testing or duplication of services.12 These tests are used by occupational therapists in some health care facilities in which MMT is the responsibility of the physical therapy service. Similar to the occupation-based functional motion assessment described in Chapter 20, screening tests are used to assess muscle strength. These tests are not as precise as MMT, and their purpose is to make a general evaluation of muscle strength and to determine areas of weakness, performance limitations, and the need for more precise testing. Screening may be accomplished by the following means:

1. Examination of the medical record for results of previous muscle test and range-of-motion (ROM) assessments

2. Observing the client entering the clinic and moving about

3. Observing the client perform functional activities, such as removing an article of clothing and shaking hands with the therapist6,12,13

4. Performing a gross check of bilateral muscle groups13

The last method can be performed while the client is comfortably seated in a sturdy chair or wheelchair. The client is asked to perform the motions against gravity (movements away from the floor) or in the gravity-minimized plane (parallel to the floor) if moving against gravity is not possible. Active range of motion (AROM) is observed, and resistance (application of force) can be given to the test motions to obtain a gross estimate of strength.

In the case of Sharon, who during the acute stage of her illness had very limited muscle strength, the occupational therapy (OT) practitioner would be able to observe changes by observing this client as she moved around her bed in an attempt to position herself. Initially she might require maximal assistance for bed repositioning or for food intake. The therapist will notice a gradual increase in automatic movements of the limbs as Sharon raises her arms to her forehead to brush back her hair with her forearm, cups her hands around the water glass being held by her husband as she sips through a straw, bends and straightens her legs in an attempt to get comfortable, or momentarily lifts her trunk away from the surface of the bed. Observation of these spontaneous movements as Sharon begins to engage within the context of her environment can serve as preliminary and informal screening of this client’s muscle strength.

Manual Muscle Test

Manual muscle testing (MMT) is a means of evaluating muscle strength. MMT measures the maximal contraction of a muscle or muscle group.6,7 Criteria used to measure strength include evidence of muscle contraction, amount of ROM through which the joint passes when the muscle contracts, and amount of resistance against which the muscle can contract. Gravity is considered a form of resistance.6,7,13 MMT is used to determine the amount of muscle power and to record gains and losses in strength.

Purposes of Manual Muscle Testing

The specific strength measurement of individual muscles through MMT can be essential for diagnosis of some neuromuscular conditions, such as peripheral nerve lesions and spinal cord injury. In peripheral nerve or nerve root lesions, the pattern of muscle weakness may help determine which nerve or nerve roots are involved, and whether the involvement is partial or complete. Careful evaluation can help determine the level(s) of spinal cord involvement and can provide an indication of whether the cord damage is complete or incomplete.14 Along with sensory evaluation, MMT can therefore be an important diagnostic aid in neuromuscular conditions.

The purposes of assessing muscle strength are to determine the amount of muscle power available and thus establish a baseline for intervention, to discern how muscle weakness is limiting performance in meaningful occupations such as ADLs and IADLs, to prevent deformities that can result from imbalances of strength, to determine the need for assistive devices as compensatory measures, to aid in the selection of occupations within the client’s capabilities, and to evaluate the effectiveness of intervention strategies and modalities.15

Methods of Assessment

Muscle strength can be assessed in several ways. The most precise method is a test of individual muscles. In this procedure, the muscle is carefully isolated through proper positioning, stabilization, and control of the movement pattern, and its strength is graded. This type of muscle testing is described by Kendall and McCreary14 and Cole, Furness, and Twomey.8 Another, and perhaps more common, method of MMT is to assess the strength of groups of muscles that perform specific motions at each joint. This type of testing was described by Daniels and Worthingham,10 Hislop and Montgomery,12,13 and the Rancho Muscle Testing Guide,20 and, for the most part, is the form that is presented later in this chapter.

Results of Assessment as a Basis for Intervention Planning

When planning intervention for maintenance or improvement of strength, the OT practitioner considers several factors in the clinical reasoning process before determining intervention priorities, goals, and modalities. Results of the muscle strength assessment will suggest the progression of the intervention program. What is the degree of weakness? Is it generalized or specific to one or more muscle groups? Are the muscle grades generally the same throughout, or is there significant disparity in muscle grades? If there is disparity, is there an imbalance of strength between the agonist and antagonist muscles that necessitates protection of the weaker muscles during OT intervention or when ADLs and IADLs are performed? When substantial imbalance between an agonist muscle and an antagonist muscle is noted, intervention goals may be directed toward strengthening the weaker group while maintaining the strength of the stronger group. Muscle imbalance may also suggest the need for an orthosis to protect the weaker muscles from overstretching while recovery is in progress. Examples of such orthoses are devices such as the bed footboard, used to prevent overstretching of the weakened ankle dorsiflexors, and the wrist cock-up splint, which can prevent overstretching of weakened wrist extensors.

Muscle grades will suggest the level of therapeutic activity or exercise that can help to maintain or improve strength. Is the weakness mild (G range), moderate (F to F+), or severe (P to 0)?15 Muscles graded F+, for example, could be strengthened by active assisted exercise or light activity against gravity. Likewise, muscles graded P will require activity or exercise in the gravity-minimized plane, with little or no resistance, to increase strength. (See Chapter 29 for further discussion of appropriate exercise and activity for specific muscle grades.)

Endurance of the muscles (i.e., how many repetitions of the muscle contraction are possible before fatigue sets in) is an important consideration in intervention planning. A frequent goal of the therapeutic activity program is to increase endurance as well as strength. Because MMT does not measure endurance, the therapist should assess endurance by engaging the client in periods of exercise or activity graded in length to determine the length of time that the muscle group can be used in sustained activity. A correlation between strength and endurance is usually noted. Weaker muscles will tend to have less endurance than stronger ones. When selecting intervention modalities for increasing endurance, the therapist may elect not to tax the muscle to its maximal ability, but rather to emphasize repetitive action at less than the maximal contraction to increase endurance and prevent fatigue.15

Sensory loss, which often accompanies muscle weakness, complicates the ability of the client to perform in an activity program. If little or no tactile or proprioceptive feedback is obtained from motion, the impulse to move is decreased or lost, depending on the severity of sensory loss. Thus, the movement may appear weak and ineffective even when strength is adequate for performance of a specific activity. With some diagnoses, a sensory re-education program (see Chapter 23) may be indicated to increase the client’s sensory awareness and feedback received from the part. In other instances, the therapist may elect to teach compensation techniques to address the sensory loss. These techniques include the use of mirrors, video playback, and biofeedback, which can be used as adjuncts to the strengthening program.

Other important considerations in the therapist’s clinical reasoning include the diagnosis and expected course of the disease. Is strength expected to increase, decrease, or remain about the same? If strength is expected to increase, what is the expected recovery period? What is the effect of exercise or activity on muscle function? Will too much activity delay the progress of recovery? If muscle power is expected to decrease, how rapid will the progression be? Are there factors to be avoided, such as vigorous activity or an exercise program that can accelerate the decrease in strength? If strength is declining, is special equipment practical and necessary? How much muscle power is needed to operate the equipment? How long will the client be able to operate a device before a decrease in muscle power makes it impracticable?15 In the case of Sharon, the therapist must be aware of the change in muscle strength of this client. It is expected that muscle strength will return in a proximal-to-distal pathway, and it is critical to protect the intrinsic muscles of the hand against overexertion to ensure the possibility of full recovery. Frequent muscle testing of select muscle groups will serve as a means to monitor progression of the disease and to assist in the introduction of appropriate intervention strategies.11,19

The therapist should assess the effect of muscle weakness on the ability to perform ADLs; this can be observed during assessment. Which tasks are most difficult to perform because of muscle weakness? How does the client compensate for the weakness? Which tasks are most important for the client to be able to perform? Is special equipment necessary or desirable for the performance of some ADLs, such as mobile arm support for independence in eating (see Chapter 30, Section II)?

If the client is involved in a total rehabilitation program and is receiving several other health care services, the activity and exercise programs must be synchronized and balanced to meet the client’s needs rather than the needs of the professionals, their schedules, and possibly their competition. The occupational therapist must be aware of the nature and extent of programs in which the client is engaged in physical therapy, recreation therapy, and any other services. Ideally, all members of the health care team should plan the exercise and activity programs together, to ensure that they complement one another.

On the basis of these considerations and others pertinent to the specific client, the occupational therapist can select enabling and purposeful activities designed to maintain or increase strength, improve performance of ADLs, and enable the use of special equipment, while protecting weak muscles from overstretching and overfatigue.

Relationship Between Joint Range of Motion and Muscle Weakness

One of the criteria used to grade muscle strength is the ROM of the joint on which the muscle acts—that is, did the muscle move the joint through complete, partial, or no ROM? Another criterion is the amount of resistance that can be applied to the part once the muscle has moved the joint through partial or complete AROM. In this context, ROM is not necessarily the full average normal ROM for the given joint; rather, it is the ROM available to the individual client. When the therapist measures joint motion (discussed in Chapter 21), it is passive ROM (PROM) that is the measure of the range available to the client. PROM, however, is not an indication of muscle strength.

When performing muscle testing, the occupational therapist must know the client’s PROM to assign muscle grades correctly. It is possible that PROM would be limited or less than average for joint motion, but that the muscle strength would be normal. Therefore, it is necessary for the therapist to have measured joint ROM or to have moved joints passively to assess available ROM before administering the muscle test. For example, the client’s PROM for elbow flexion may be limited to 0 to 120 degrees because of an old fracture. If the client can flex the elbow joint to 120 degrees and can withstand moderate resistance during the muscle test, the muscle would be graded G (4). In such cases, the occupational therapist should record the limitation with the muscle grade, for example, 0 to 120 degrees/G.10 Conversely, if the client’s available ROM for elbow flexion is 0 to 160 degrees, and he or she can flex the elbow against gravity through only 120 degrees, the muscle would be graded F− because the part moves through only partial ROM against gravity. When the therapist determines the client’s available ROM before performing the muscle test, he or she can grade muscle strength on that basis rather than by using the average normal ROM as the standard. When assessing Sharon’s muscle strength during the recovery phase of her illness, the OT practitioner most likely will find a disparity between the client’s PROM and muscle strength, with limitation in strength preventing Sharon from moving her body parts through full available ROM, especially against gravity. The discrepancy will decrease as remyelination and axonal regeneration occur.

Limitations of the Manual Muscle Test

Limitations of MMT are that it cannot measure muscle endurance (the number of times the muscle can contract at its maximal level and resist fatigue),6 muscle coordination (the smooth, rhythmic interaction of muscle function), or motor performance capabilities of the client (the use of muscles for functional activities).8

MMT is not appropriate for and cannot be used accurately with clients who have spasticity caused by upper motor neuron disorders such as cerebrovascular accident (stroke) or cerebral palsy. In these conditions, muscles are often hypertonic. Muscle tone and ability to perform movements are influenced by primitive reflexes and the position of the head and body in space. Also, movements tend to occur in gross synergistic patterns that make it impossible for the client to isolate joint motions, which is demanded in MMT procedures.2,3,6,7,16

However, when administered during the final recovery stage, when spasticity and synergy patterns have disappeared and the client has achieved isolated control of voluntary muscle function, MMT may reveal some residual weakness. In these instances, some assessment of strength can be of value in designing a treatment program. (See Chapters 19, 31, Section II, and 32 for methods of evaluating motor function of clients with upper motor neuron disorders.)

Contraindications and Precautions

Assessment of strength using MMT is contraindicated when the client has inflammation or pain in the region to be tested; a dislocation or unhealed fracture; recent surgery, particularly of musculoskeletal structures; myositis ossificans; or bone carcinoma or any fragile bone condition.7,15

Special precautions must be taken when resisted movement could aggravate the client’s condition, as might occur with osteoporosis, subluxation or hypermobility of a joint, hemophilia or any type of cardiovascular risk or disease, abdominal surgery or an abdominal hernia, and fatigue that exacerbates the client’s condition.6,7

Unlike the PROM assessment discussed in Chapter 21, MMT requires the client’s complete involvement in the testing procedure. Therefore, the therapist must be mindful of the client’s willingness to expend true effort (especially when resistance is applied), to endure some discomfort, and to understand the requirements of the test. Results of MMT should not be compromised as a result of cognitive and language barriers, or the client’s inability to perform the motor skills required for the test.13

Knowledge and Skill of the Occupational Therapist

The validity of MMT depends on the knowledge and skill of the OT practitioner in using the correct testing procedure. Careful observation of movement, careful and accurate palpation, correct positioning, consistency of procedure, and experience of the therapist are critical factors in accurate testing.10,12–14

To be proficient in manual muscle testing, the OT practitioner must have detailed knowledge about all aspects of muscle function. Joints and joint motions, muscle innervation, origin and insertion of muscles, action of muscles, direction of muscle fibers, angle of pull on the joints, and the role of muscles in fixation and substitution are important considerations. The therapist must be able to locate and feel contraction of the muscles; recognize whether the contour of the muscle is normal, atrophied, or hypertrophied; and detect abnormal movements and positions. The OT practitioner must use consistent methods in the application of test procedures. Knowledge and experience are necessary to detect substitutions and interpret strength grades with accuracy.12–14

It is necessary for the OT practitioner to acquire skill and experience in testing and grading the muscles of normal persons of both genders and of all ages. Many factors affect muscle strength. The age, gender, and lifestyle of the client; the muscle size and type and speed of contraction; the effect of previous training for the testing situation; joint position during the muscle contraction; previous training effects; and time of day, temperature, and fatigue all can affect muscle strength.6,7 Experience can help the therapist differentiate among strength grades if these factors are taken into account.18

General Principles of Manual Muscle Testing

If several tests are to be administered, they should be organized to avoid frequent repositioning of the client.12,13,20 The OT practitioner should observe contour of the part, comparative symmetry of the muscle on both sides, and any apparent hypertrophy (increase in size) or atrophy (shrinking or wasting). During PROM, the therapist can estimate muscle tone. Is there less than or greater than normal resistance to passive movement? During AROM, the therapist can observe the quality of movement, such as movement speed, smoothness, and rhythm, and any abnormal movements such as tremors.18

Correct positioning of the client and the body part is essential for effective and correct evaluation. The client should be positioned comfortably on a firm surface. Clothing should be arranged or removed so the therapist can see the muscle or muscles being tested. For maximal comfort to the client, the assessment is administered to all muscles possible in a given position (upright, prone, supine, side-lying) before changing the position of the client. If the client cannot be placed in the correct position for the test, the OT practitioner must adapt the test and use clinical judgment in approximating strength grades.18 In addition to correct positioning, test validity depends on careful stabilization, palpation of the muscles, and observation of movement.10

Gravity Influencing Muscle Function

Gravity is a form of resistance to muscle power. It is used as a grading criterion in tests of the neck, trunk, and extremities. In other words, muscle grade is based on whether a muscle can move the part against gravity.14 Movements against gravity occur in a vertical plane (i.e., away from the floor or toward the ceiling) and are used with grades F (3), G (4), and N (5). Movements against gravity and resistance are performed in a vertical plane with added manual or mechanical resistance and are used with F+ (3+) to N (5) grades. Tests for weaker muscles (O, T [1], P [2], and P+ [2+] grades) are often performed in a horizontal plane (i.e., parallel to the floor) to reduce the resistance of gravity on muscle power. This position has been referred to as the gravity-eliminated, gravity-minimized, or gravity-lessened test position.10,14,18 Gravity-eliminated is the common term to designate this position.16 Because the effect of gravity on muscle function cannot be eliminated completely, gravity-minimized or gravity-lessened may be more accurate terms. The term gravity-minimized is used in this chapter.10,14

In many muscle tests, the effect of gravity on the ability to perform the movement must be considered in grading muscle power. It is of lesser importance, however, in tests of the forearm, fingers, and toes because the weight of the part lifted against gravity is insignificant compared with the muscle strength.10,14 Therefore, the OT practitioner may choose to do the tests for F (3) to N (5) in the gravity-minimized plane. In other tests, positioning for movements in the gravity-decreased position or the against-gravity position may not be feasible. For example, in the test for scapula depression, positioning to perform the movement against gravity would require the client to assume an inverted position. In individual cases, positioning for movement in the correct plane may not be possible because of confinement to bed, generalized weakness, trunk instability, immobilization devices, and medical precautions. In these instances, the OT practitioner must adapt the positioning to the client’s needs and must use clinical judgment in modifying the grading. If tests of the forearm, fingers, and toes are performed against gravity rather than in the gravity-minimized plane, the standard definitions of muscle grades can be modified when muscle grades are recorded. Partial ROM against gravity is graded P (2), and full ROM against gravity is graded F (3).10 Such modifications in positioning and grading should be noted by the therapist when results of the muscle test are recorded.

For consistency in procedure and grading, gravity-minimized positions and against-gravity positions are used in the manual muscle tests described later, except in cases in which the positioning is not feasible or would be awkward or uncomfortable for the client. Modifications in positioning and grading have been cited with the individual tests.

Muscle Grades

Although the definitions of muscle grades are standard, assignment of muscle grade during MMT depends on the clinical judgment, knowledge, and experience of the OT practitioner,10 especially when slight, moderate, or maximal resistance is determined. Age, gender, body type, occupation, and leisure activities all influence the amount of resistance that a particular client can take.9,10,12–14 Normal strength for an 8-year-old girl will be considerably less than that for a 25-year-old man, for example. Additionally, strength tends to decline with age, and full resistance to the same muscle group will vary considerably from an 80-year-old man to a 25-year-old man.7,14 Therefore, the amount of resistance that can be applied to grade a particular muscle group as N (5) or G (4) varies among individual clients.9,10,12–14

The amount of resistance that can be given also varies among muscle groups. Muscle strength is relative to the cross-sectional size of the muscle. Larger muscles have greater strength.7,10 For example, the flexors of the wrist are larger and therefore have more power and can take much more resistance than the abductors of the fingers. The OT practitioner must consider the size and relative power of the muscles and the leverage used when giving resistance.15 The amount of resistance applied should be modified accordingly. When only one side of the body is involved in the dysfunction causing muscle weakness, the OT practitioner can establish the standards for strength by testing the unaffected side first.

Because weak muscles fatigue easily, the results of MMT may not be accurate if the client is tired. There should be no more than three repetitions of the test movement because fatigue can result in grading errors if the muscle becomes tired as a result of low endurance.7,8 Pain, swelling, or muscle spasm in the area being tested may also interfere with the testing procedure and accurate grading. Such problems should be recorded on the evaluation form.18 Psychological factors must be considered in interpreting muscle strength grades. When interpreting strength, the therapist must assess motivation, cooperation, and the effort put forth by the client.10

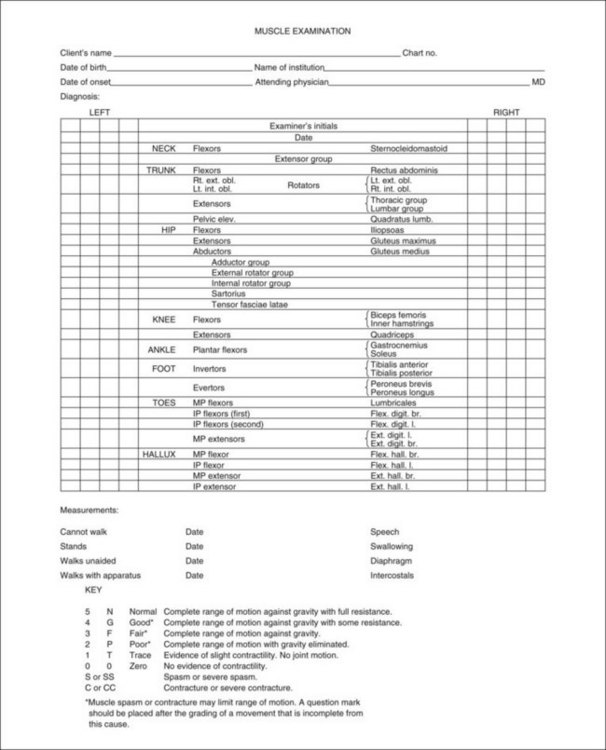

In MMT, muscles are graded according to the criteria listed in Table 22-1.6,10,12,13,20

TABLE 22-1

Muscle Grades and Their Definitions

| Number | Grade | Word/Letter Grade Definition |

| 0 | Zero (0) | No muscle contraction can be seen or felt. |

| 1 | Trace (T) | Contraction can be observed or felt, but there is no motion. |

| 2− | Poor minus (P−) | Part moves through incomplete ROM with gravity minimized. |

| 2 | Poor (P) | Part moves through complete ROM with gravity minimized. |

| 2+ | Poor plus (P+) | Part moves through less than 50% of available ROM against gravity or through complete ROM with gravity minimized against slight resistance.10 |

| 3− | Fair minus (F−) | Part moves through more than 50% of available ROM against gravity.10 |

| 3 | Fair (F) | Part moves through complete ROM against gravity. |

| 3+ | Fair plus (F+) | Part moves through complete ROM against gravity and slight resistance. |

| 4 | Good (G) | Part moves through complete ROM against gravity and moderate resistance. |

| 5 | Normal (N) | Part moves through complete ROM against gravity and maximal resistance. |

The purpose of using “plus” or “minus” designations with muscle grades is to “fine grade” muscle strength. These designations are likely to be used by the experienced OT practitioner. Two OT practitioners testing the same individual may vary up to a half grade in their results, but there should not be a whole grade difference.18

Substitutions

The brain thinks in terms of movement and not in terms of contraction of individual muscles.10 Thus, a muscle or muscle group may attempt to compensate for the function of a weaker muscle to accomplish a movement. These movements are called trick movements, or substitutions.6,7,14 Substitutions can occur during MMT. To test muscle strength accurately, the therapist must give careful instructions; eliminate substitutions in the testing procedure by correct positioning, stabilization, and palpation of the muscle being tested; and ensure careful performance of the test motion without extraneous movements. To prevent substitutions, the correct position of the body should be maintained and movement of the part performed without shifting the body or turning the part.6,7,14 The therapist must palpate contractile tissue (muscle fibers or tendon) to detect tension in the muscle group under examination. It is only through correct palpation that the therapist can be certain that the motion observed is not being performed by substitution.6,10 Undetected trick movements can mask the client’s problems, resulting in inaccurate treatment planning.6

In the tests that follow, possible substitutions are described at the end of the directions. The OT practitioner should be familiar with these substitutions to detect them and correct the procedure. Detecting substitutions is a skill gained with time and experience.

Procedure for Testing

Testing should be performed according to a standard procedure to ensure accuracy and consistency. Each of the tests that follow is divided into these steps: (1) position, (2) stabilize, (3) palpate, (4) observe, (5) resist, and (6) grade.

First, the client should be positioned for the specific muscle test. The occupational therapist should position himself or herself in relation to the client. Then, the therapist stabilizes the part proximal to the part being tested to eliminate extraneous movements, isolate the muscle group, ensure the correct test motion, and eliminate substitutions. The therapist should then demonstrate or describe the test motion to the client and should ask him or her to perform the test motion and return to the starting position. The therapist makes a general observation of the form and quality of movement, looking for substitutions or difficulties that may require adjustments in positioning and stabilization. The therapist then places his or her fingers (typically the tips of the index and long fingers—avoid using the thumb because it has its own pulse) for palpation of one or more of the prime movers, or its tendinous insertion, on the muscle group being tested and asks the client to repeat the test motion. While simultaneously palpating the muscle group, the therapist again observes the movement for possible substitution and for the amount of range completed. When the client has moved the part through the available ROM, the therapist asks the client to hold the end position. The therapist removes the palpating fingers and uses the free hand to resist in the direction opposite that of the test movement. For example, when elbow flexion is tested, the therapist applies resistance in the direction of extension. The therapist usually must maintain stabilization when resistance is given. Manual muscle tests use the “break test,” that is, resistance is applied after the client has reached the end of the available ROM.12,13

The client should be allowed to establish a maximal contraction (set the muscles) before resistance is applied.10,15 In most tests, the OT practitioner applies resistance near the distal segment to which the muscle is attached after preparing the client by giving the command to hold. Resistance should be applied gradually in a direction opposite to the line of pull of the muscle or muscle group being tested.12 The break test should not evoke pain, and resistance should be released immediately if pain or discomfort occurs.10 Finally, the therapist grades the muscle strength according to the preceding standard definitions of muscle grades. This procedure is used for tests of strength of grades F+ (3+) and above. Resistance is not applied for tests of muscles from F (3) to 0. Slight resistance is sometimes applied to a muscle that has completed the full ROM in the gravity-minimized plane to determine whether the grade is P+. Figure 22-1 shows a sample form for recording muscle grades.

The following directions do not include tests for the face, neck, and trunk. Refer to the references for these tests, as well as for comprehensive treatment of the topic of manual muscle testing.6,8,10,12–14

Manual Muscle Testing of the Upper Extremity

Scapula Elevation, Neck Rotation, and Lateral Flexion

| Muscles10 | Innervation: nerve, nerve roots10,14 |

| Upper trapezius | Accessory nerve (CN 12), C2-4 |

| Levator scapula | Dorsal scapular nerve, C3-5 |

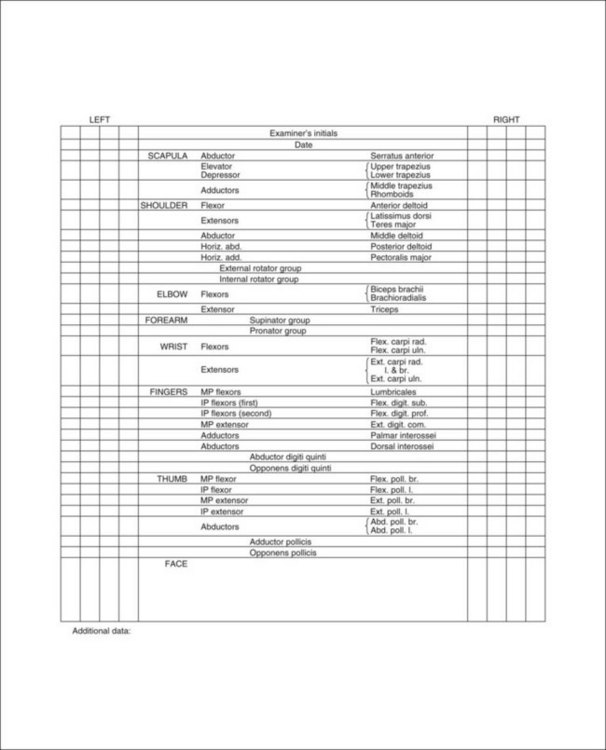

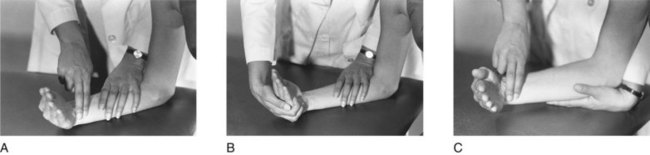

Procedure for Testing Grades Normal (N or 5) to Fair (F or 3)10,12,13

1. Position: The client is seated erect with arms resting at sides of body. The OT practitioner stands behind the client toward the side to be tested.

2. Stabilize: A chair back can offer stabilization to the trunk, if necessary.

3. Palpate: Palpate the upper trapezius parallel to the cervical vertebrae, near the shoulder-neck curve.10

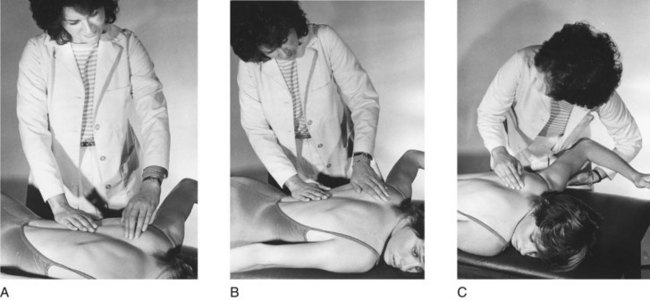

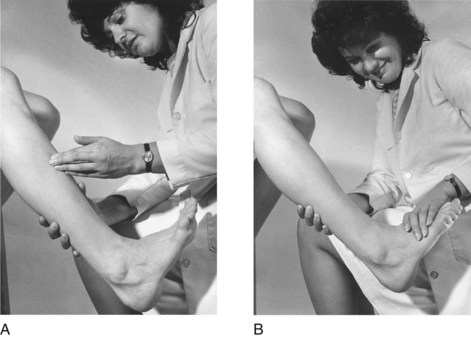

4. Observe: Observe the elevation of the scapula as the client shrugs the shoulder toward the ear and rotates and laterally flexes the neck toward the side being tested at the same time (Figure 22-2, A).14

5. Resist: Provide resistance by placing one hand on top of the shoulder toward the scapula depression and the other hand on the side of the head toward derotation and lateral flexion to the opposite side (Figure 22-2, B).14

Procedure for Testing Grades Poor (P or 2), Trace (T or 1), and Zero (0)10

1. Position: The client should be prone with head in midposition. The OT practitioner stands opposite the side being tested.

2. Stabilize: The weight of the trunk on the supporting surface provides adequate stabilization.

3. Palpate: Palpate the upper trapezius, as described in the previous procedure, while observing the client elevating the shoulder being tested. Because of positioning, the neck rotation and lateral flexion components are omitted for these grades (Figure 22-2, C).

4. Grade: The standard definitions of muscle grades should be used.

Substitutions: Rhomboids and the levator scapula can elevate the scapula if the upper trapezius is weak or absent. In the event of substitution, some downward rotation of the acromion will be observed during movement.4,15,20

Scapula Depression, Adduction, and Upward Rotation

| Muscles1,4 | Innervation6,7 |

| Lower trapezius | Spinal accessory nerve, C3,4 |

| Middle trapezius | |

| Serratus anterior | Long thoracic nerve, C5-7 |

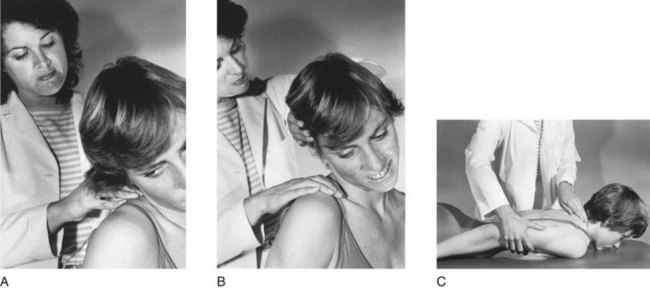

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone with the arm positioned overhead in 130 to 165 degrees of abduction and resting on the supporting surface. The forearm is in midposition with the thumb toward the ceiling.12,13 The therapist stands next to the client on the opposite side7,10 or on the same side.12,13

2. Stabilize: The weight of the body provides adequate stabilization. This test is given in the gravity-minimized position, because it is not feasible to position the client for the against-gravity movement (head down). If the deltoid is weak, the arm may be supported and passively raised by the therapist while the client attempts the motion.10

3. Palpate: Palpate the lower trapezius distal to the medial end of the spine of the scapula and parallel to the thoracic vertebrae, approximately at the level of the inferior angle of the scapula.10

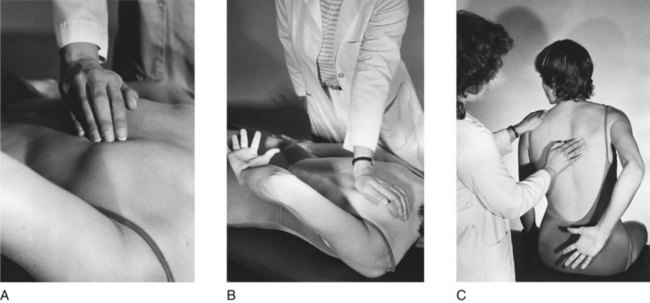

4. Observe: Observe the client while he or she lifts the arm off the supporting surface to ear level.12 During this movement, there is strong downward fixation of the scapula by the lower trapezius (Figure 22-3, A).10

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the lateral angle of the scapula, toward elevation and abduction (Figure 22-3, B).10 Resistance may be applied on the humerus just above the elbow in a downward direction if shoulder and elbow strength are adequate.12–14

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position and stabilize: Position and stabilize the client as described in the previous test. No stabilization is required. The therapist may support the client’s arm if the posterior deltoid muscles and triceps are weak.12

2. Palpate and observe: Palpate and observe the client in the same manner as described for the previous test (Figure 22-3, C).

3. Grade: The client receives a grade of P if he or she can complete full scapular ROM without the weight of the arm.12

Substitutions: Middle trapezius or rhomboids may substitute.6 Rotation of the inferior angle of the scapula toward the spine is evidence of substitution.20

Scapula Abduction and Upward Rotation

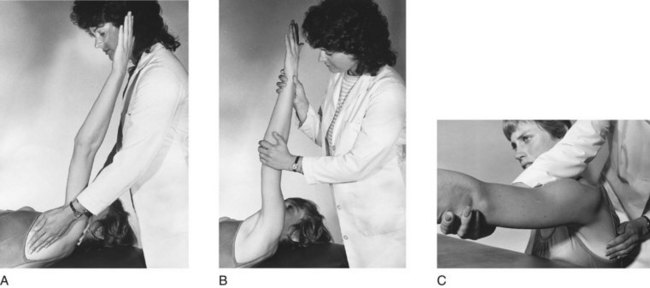

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

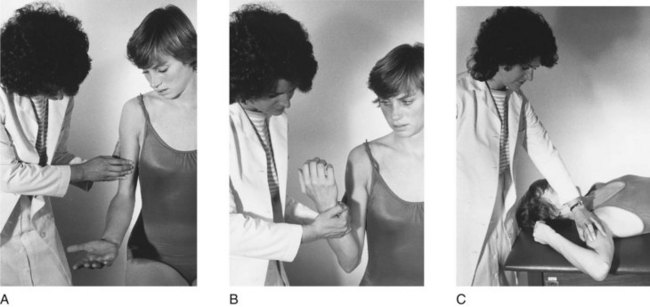

1. Position: The client is supine with the shoulder flexed to 90 degrees and slightly abducted, elbow extended or fully flexed. The therapist stands next to the client on the side being tested.6,7,10,13,14

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the weight of the trunk or over the shoulder.6

3. Palpate: Palpate the digitations of the origin of the serratus anterior on the ribs, along the midaxillary line and just distal and anterior to the axillary border of the scapula.6,10 Note that muscle contraction may be difficult to detect in women and overweight clients.

4. Observe: Observe the client reaching upward as if pushing the arm toward the ceiling, abducting the scapula (Figure 22-4, A).6,10

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the humerus, and push the client’s arm directly downward toward scapula adduction (Figure 22-4, B).6,7,10,13 If there is shoulder instability, the therapist should support the arm and not apply resistance. In this instance, only a grade of F (3) can be tested.7

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated with the arm supported by the therapist in 90 degrees of shoulder flexion and the elbow extended.6,10,13

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the shoulder to be tested.

3. Palpate: The client is palpated in the same manner as described in the previous section.

4. Observe: The therapist should note any abduction of the scapula as the arm moves forward (Figure 22-4, C).10 Weakness of this muscle produces “winging” of the scapula.8

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: The pectoralis major and minor may pull the scapula forward into abduction at its insertion on the humerus; the upper and lower trapezius and contralateral trunk rotation may also substitute.6 The therapist observes for humeral horizontal adduction followed by scapula abduction.7,14

Scapula Adduction

| Muscles10,14 | Innervation6,10 |

| Middle trapezius | Spinal accessory nerve, C3,4 |

| Rhomboids | Dorsal scapular nerve, C4,5 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees and externally rotated and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees, shoulder resting on the supporting surface. The therapist stands on the side being tested.10,12–14

2. Stabilize: The weight of the trunk on the supporting surface usually provides adequate stabilization, or stabilization can be provided over the midthorax to prevent trunk rotation if necessary.

3. Palpate: Palpate the middle trapezius between the spine of the scapula and adjacent vertebrae in alignment with the abducted humerus.

4. Observe: Observe the client lifting the arm off the table, and note any movement of the vertebral border of the scapula toward the thoracic vertebrae (Figure 22-5, A).

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the vertebral border of the scapula toward abduction (Figure 22-5, B).6,7,10,13

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position and stabilize: The therapist positions and stabilizes the client in the same way as described in the previous test but now supports the weight of the arm by cradling it under the humerus and forearm.14 The client may also be positioned sitting erect, with the arm resting on a high table and the shoulder midway between 90-degree flexion and abduction.10 The therapist stands behind the client in this instance.

2. Palpate and observe: Palpate and observe the middle trapezius. Ask the client to bring the shoulders together as if assuming an erect posture. Observe scapula adduction toward the vertebral column (Figure 22-5, C).

3. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: The posterior deltoid can act on the humerus and produce scapula adduction.6 Observe for use of humeral extension to initiate scapula adduction. Rhomboids may substitute, but the scapula will rotate downward.7,15,20

Scapula Adduction and Downward Rotation

| Muscles7,8 | Innervation6–8 |

| Rhomboids major and minor | Dorsal scapular nerve, C4,5 |

| Levator scapula | |

| Middle trapezius | Spinal accessory nerve, C3,4 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone with the head rotated to the opposite side; the arm on the side being tested is placed in shoulder adduction and internal rotation, with the elbow slightly flexed and the dorsum of the hand resting over the lumbosacral area of the back.6,12 The therapist stands opposite the side being tested.7,8,10

2. Stabilize: The weight of the trunk on the supporting surface offers adequate stabilization.7,14

3. Palpate: Palpate the rhomboid muscles between the vertebral border of the scapula and the second to fifth thoracic vertebrae.10,14 (They may be more easily discerned toward the lower half of the vertebral border of the scapula, because they lie under the trapezius muscle.)

4. Observe: Observe the client raising the hand up off the back while maintaining the position of the arm.7,12 During this motion, the anterior aspect of the shoulder must lift from the table surface. Observe scapula adduction and downward rotation while the shoulder joint is in some extension (Figure 22-6, A).10

FIGURE 22-6 Scapula adduction and downward rotation. A, Palpate and observe. B, Resist. C, Gravity-minimized position.

5. Resist: Provide resistance over the scapula toward abduction and upward rotation6 (Figure 22-6, B).

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client sits erect with the arm positioned behind the back in the same manner described for the previous test. The therapist stands behind the client, slightly opposite the side being tested.10

2. Stabilize: The trunk is stabilized by placing one hand over the shoulder, opposite the one being tested, to prevent trunk flexion and rotation.

3. Palpate: The rhomboids are palpated as described previously.

4. Observe: Scapula adduction and downward rotation are observed as the client lifts the hand away from the back (Figure 22-6, C).

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: The middle trapezius may substitute, but the movement will not be accompanied by downward rotation.12 The posterior deltoid acting to perform horizontal abduction or glenohumeral extension can produce scapula adduction through momentum. Scapula adduction would be preceded by extension or abduction of the humerus.15,20 The pectoralis minor could tip the scapula forward.7

Shoulder Flexion

| Muscles10 | Innervation6,10 |

| Anterior deltoid | Axillary nerve, C5,6 |

| Coracobrachialis | Musculocutaneous nerve, C5-7 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is seated with the arm relaxed at the side of the body and the hand facing backward.12 A straight-backed chair may be used to offer trunk support. The therapist stands on the side being tested and slightly behind the client.7,10,20

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the shoulder being tested, but allow the normal abduction and upward rotation of the scapula that occurs with this movement.10,13

3. Palpate: Palpate the anterior deltoid just below the clavicle on the anterior aspect of the humeral head.7

4. Observe: Observe the client flexing the shoulder joint to 90-degree flexion (parallel to the floor; Figure 22-7, A).6,10,12

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the humerus downward toward shoulder extension (Figure 22-7, B).6,7,8,12

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is placed in a side-lying position. The side being tested is superior. If the client cannot maintain the weight of the arm against gravity, the therapist can support it.6,12 If the side-lying position is not feasible, the client may remain seated, and the test procedure described above can be performed with the grading modified.10

2. Palpate and observe: The therapist should palpate and observe the client in the same manner as described in the previous test. The arm is moved toward the face to 90-degree shoulder flexion (Figure 22-7, C).

3. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades. If the seated position was used for tests of grades poor to zero, partial ROM against gravity should be graded poor.10,13

Substitutions: Clavicular fibers of the pectoralis major can perform flexion through partial ROM while performing horizontal adduction. The biceps brachii may flex the shoulder, but the humerus will first be rotated externally for the best mechanical advantage. The upper trapezius will assist flexion by elevating the scapula. Observe for flexion accompanied by horizontal adduction, external rotation, or scapula elevation.10,15,20

Note: Arm elevation in the plane of the scapula, about halfway between shoulder flexion and abduction, is called scaption. This movement is more commonly used for function than for shoulder flexion or abduction. Scaption is performed by the deltoid and supraspinatus muscles. It is tested in a way similar to that used for shoulder flexion, described previously, except that the arm is elevated in a position 30 to 45 degrees anterior to the frontal plane.6,12

Shoulder Extension

| Muscles4,10,14 | Innervation6,10 |

| Latissimus dorsi | Thoracodorsal nerve, C6-8 |

| Teres major | Lower subscapular nerve, C5-7 |

| Posterior deltoid | Axillary nerve, C5,6 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone, with the shoulder joint adducted and internally rotated so that the palm of the hand is facing up.6,7,12 The therapist stands on the opposite side or on the test side.

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the scapula on the side being tested.

3. Palpate: Palpate the teres major along the axillary border of the scapula. The latissimus dorsi may be palpated slightly below this point or closer to its origins parallel to the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.7,10 The posterior deltoid may be found over the posterior aspect of the humeral head (Figure 22-8, A).

4. Observe: Observe the client extending the shoulder joint.

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the humerus in a downward and outward direction, toward flexion and slight abduction (Figure 22-8, B).6,7,10,12–14

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is placed in the side-lying position; the therapist stands behind the client.6

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the scapula. If the client cannot maintain the weight of the part against gravity, the therapist should support the client’s arm.6 If the side-lying position is not feasible, the client may remain in the prone position, and the test may be performed as described for the previous test with modified grading.10

3. Palpate: Palpate the teres major or latissimus dorsi as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client extending the arm backward in a plane parallel to the floor (Figure 22-8, C).

5. Grade: Grade the client according to standard definitions of muscle grades. If the tests for grades poor to zero were done in the prone-lying position, completion of partial ROM should be graded poor.10

Substitutions: Scapula adduction can substitute. Observe for flexion of the shoulder or adduction of the scapula preceding extension of the humerus.15

Shoulder Abduction to 90 Degrees

| Muscles10,14 | Innervation10 |

| Middle deltoid | Axillary nerve, C5,6 |

| Supraspinatus | Suprascapular nerve, C5 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

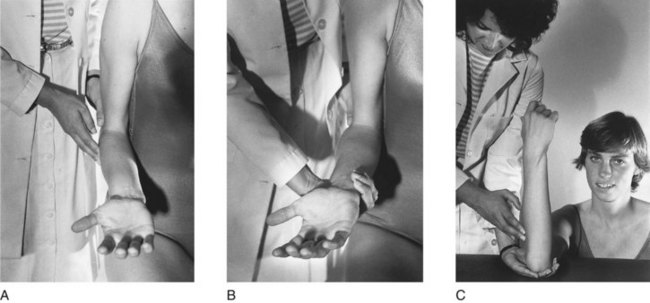

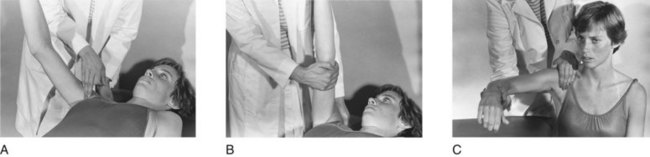

1. Position: The client is seated, with arms relaxed at the sides of the body. The elbow on the side to be tested should be slightly flexed and the palms facing toward the body. The therapist stands behind the client.6,7,12

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the scapula on the side to be tested.6,10,14

3. Palpate: Palpate the middle deltoid over the middle of the shoulder joint from the acromion to the deltoid tuberosity.6,10,14,15 The supraspinatus is too deep to palpate.6

4. Observe: Observe the client abducting the shoulder to 90 degrees. During movement, the client’s palm should remain down, and the therapist should observe that there is no external rotation of the shoulder nor elevation of the scapula6,10,12–15 (Figure 22-9, A).

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the humerus toward adduction (Figure 22-9, B).12

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is in the supine position, lying with the arm to be tested resting at the side of the body, palm facing in and the elbow slightly flexed. The therapist stands in front of the supporting surface toward the side to be tested.10,12

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the shoulder to be tested.

3. Palpate and observe: Follow the technique described for the previous test. The therapist asks the client to bring the arm out and away from the body, while abducting the shoulder to 90 degrees (Figure 22-9, C).

4. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: The long head of the biceps may attempt to substitute. Observe for elbow flexion and external rotation accompanying the movement.12 The anterior and posterior deltoids can act together to effect abduction. The upper trapezius may attempt to assist. Observe for scapula elevation preceding movement.7,15,20

Shoulder External Rotation

| Muscles4,10,14 | Innervation4,10,14 |

| Infraspinatus | Suprascapular nerve, C5,6 |

| Teres minor | Axillary nerve, C5,6 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone, with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees and the humerus in neutral (0-degree) rotation, elbow flexed to 90 degrees. The forearm is in neutral rotation, hanging over the edge of the table, perpendicular to the floor.6–8,12 The therapist stands in front of the supporting surface, toward the side to be tested.10,14

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the distal end of the humerus by placing a hand under the arm on the supporting surface to prevent shoulder abduction.7,14

3. Palpate: Palpate the infraspinatus muscle just below the spine of the scapula on the body of the scapula6 or the teres minor along the axillary border of the scapula.10

4. Observe: Observe the client rotating the humerus so that the back of the hand is moving toward the ceiling (Figure 22-10, A).6,7,10,12–14

FIGURE 22-10 Shoulder external rotation. A, Palpate and observe. B, Resist. C, Gravity-minimized position.

5. Resist: Provide resistance on the distal end of the forearm toward the floor in the direction of internal rotation (Figure 22-10, B).6,10,12–14 Apply resistance gently and slowly to prevent injury to the glenohumeral joint, which is inherently unstable.12

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated, with arm adducted and in neutral rotation at the shoulder. The elbow is flexed to 90 degrees, with the forearm in neutral rotation. The therapist stands in front of the client toward the side to be tested.6,7

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization on the arm against the trunk at the distal end of the humerus to prevent abduction and extension of the shoulder, and over the shoulder to be tested.5,7,20 The hand stabilizing over the shoulder can be used to palpate the infraspinatus simultaneously.

3. Palpate: Palpate the infraspinatus and teres minor as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client moving the forearm away from the body by rotating the humerus while maintaining neutral rotation of the forearm (Figure 22-10, C).6,20

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: If the elbow is extended and the client supinates the forearm, the momentum could aid external rotation of the humerus. Scapular adduction can pull the humerus backward and into some external rotation. The therapist should observe for scapula adduction and initiation of movement with forearm supination.15,20

Shoulder Internal Rotation

| Muscles10,14,15 | Innervation4,5,10 |

| Subscapularis | Subscapular nerve, C5,6 |

| Pectoralis major | Medial and lateral pectoral nerves, C5-T1 |

| Latissimus dorsi | Thoracodorsal nerve, C6-8 |

| Teres major | Subscapular nerve, C5-7 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone, with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees, the humerus in neutral rotation, and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees. A rolled towel may be placed under the humerus. The forearm is perpendicular to the floor. The therapist stands on the side to be tested, just in front of the client’s arm.6–8,12

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the distal end of the humerus by placing a hand under the arm and on the supporting surface, as for external rotation.6,7,10,14

3. Palpate: Palpate the teres major and latissimus dorsi along the axillary border of the scapula toward the inferior angle.

4. Observe: Observe the client internally rotating the humerus, moving the palm of the hand upward toward the ceiling (Figure 22-11, A).6,10

FIGURE 22-11 Shoulder internal rotation. A, Palpate and observe. B, Resist. C, Gravity-minimized position.

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the volar surface of the forearm anteriorly toward external rotation (Figure 22-11, B).7,10,12–14

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated, with the shoulder adducted and in neutral rotation, elbow flexed to 90 degrees with the forearm in neutral rotation. The therapist stands on the side to be tested.6,20

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization on the arm at the distal end of the humerus against the trunk to prevent abduction and extension of the shoulder.

3. Palpate: Palpate the teres major and latissimus dorsi, as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client moving the palm of the hand toward the chest, while internally rotating the humerus (Figure 22-11, C).

Substitutions: If the trunk is rotated, gravity will act on the humerus, rotating it internally.6 The therapist should observe for trunk rotation. When the elbow is in extension, pronation of the forearm can substitute.10,15,20

Shoulder Horizontal Abduction

| Muscles4,10,15 | Innervation10,13 |

| Posterior deltoid | Axillary nerve, C5,6 |

| Infraspinatus | Suprascapular nerve, C5,6 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone, with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees and in slight external rotation, elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and forearm perpendicular to the floor. The therapist stands on the side being tested.14,15

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the scapula.6,10

3. Palpate: Palpate the posterior deltoid below the spine of the scapula and distally toward the deltoid tuberosity on the posterior aspect of the shoulder.10

4. Observe: Observe the client horizontally abducting the humerus, lifting the arm toward the ceiling (Figure 22-12, A).12

FIGURE 22-12 Shoulder horizontal abduction. A, Palpate and observe. B, Resist. C, Gravity-minimized position.

5. Resist: Provide resistance just proximal to the elbow obliquely downward toward horizontal adduction (Figure 22-12, B).6,12–14

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated, with the arm in 90-degree abduction, the elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and the palm down, supported on a high table or by the therapist.6,12 If a table is used, powder may be sprinkled on the surface to reduce friction.

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the scapula.

3. Palpate: Palpate the posterior deltoid, as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client pulling the arm backward into horizontal abduction (Figure 22-12, C).

5. Grade: Client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: Latissimus dorsi and teres major may assist movement if the posterior deltoid is very weak. Movement will occur with more shoulder extension rather than at the horizontal level. Scapula adduction may produce slight horizontal abduction of the humerus, but trunk rotation and shoulder retraction would occur.6,15,20 The long head of the triceps may substitute. Maintain some flexion at the elbow to prevent this.12

Shoulder Horizontal Adduction

| Muscles4,12–14 | Innervation4,10,12,13 |

| Pectoralis major | Medial and lateral pectoral nerves, C5-T1 |

| Anterior deltoid | Axillary nerve, C5,6 |

| Coracobrachialis | Musculocutaneous nerve, C6,7 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is supine, with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees, elbow flexed or extended. The therapist stands next to the client on the side being tested or behind the head of C.4,6,7,10,12

2. Stabilize: Stabilize the trunk by placing one hand over the shoulder on the side being tested to prevent trunk rotation and scapula elevation.

3. Palpate: Palpate over the insertion of the pectoralis major at the anterior aspect of the axilla.6

4. Observe: Observe the client horizontally adducting the humerus, moving the arm toward the opposite shoulder to a position of 90 degrees of shoulder flexion.14 If the client cannot maintain elbow extension, the therapist may guide the forearm to prevent the hand from hitting the client’s face (Figure 22-13, A).

FIGURE 22-13 Shoulder horizontal adduction. A, Palpate and observe. B, Resist. C, Gravity-minimized position.

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the humerus, in an outward direction toward horizontal abduction (Figure 22-13, B).6,7,10

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated next to a high table, with the arm supported in 90 degrees of shoulder abduction and slight flexion at the elbow.4,12,20 Powder may be sprinkled on the supporting surface to reduce the effect of resistance from friction during movement, or the therapist may support the arm.6

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the shoulder on the side being tested, simultaneously using the stabilizing hand to palpate the pectoralis major muscle.6

3. Palpate: Palpate the pectoralis major, as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client horizontally adducting the arm toward the opposite shoulder, in a plane parallel to the floor (Figure 22-13, C).

Substitutions: Muscles may substitute for one another. If the pectoralis major is not functioning, the other muscles will perform the motion, which will be considerably weakened.15 Contralateral trunk rotation, the coracobrachialis, or the short head of the biceps may substitute.6

Elbow Flexion

| Muscles10,12–14 | Innervation12–14 |

| Biceps brachii | Musculocutaneous nerve C5,6 |

| Brachialis | |

| Brachioradialis | Radial nerve C5,6 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is seated, with the arm adducted at the shoulder and extended at the elbow and held against the side of the trunk. The forearm is supinated to test for the biceps primarily (forearm should be positioned in pronation to test for the brachialis primarily, and in midposition to test for the brachioradialis).10,12,13 The therapist stands next to the client on the side being tested or directly in front of the client.

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the humerus (in adduction).

3. Palpate: Palpate the biceps brachii over the muscle belly, on the middle of the anterior aspect of the humerus. Its tendon may be palpated in the middle of the antecubital space.6,7,10 (Brachioradialis is palpated over the upper third of the radius on the lateral aspect of the forearm, just below the elbow. The brachialis may be palpated lateral to the lower portion of the biceps brachii if the elbow is flexed and in the pronated position.15)

4. Observe: Observe the client flexing the elbow, with hand toward the face. The therapist should observe for maintenance of forearm in supination (when testing for biceps) and for relaxed or extended wrist and fingers (Figure 22-14, A).6,15

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the volar aspect of the forearm, pulling downward toward elbow extension (Figure 22-14, B).7,10,14

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is supine, with the shoulder abducted to 90 degrees and externally rotated, elbow extended, and forearm supinated. The therapist stands at the head of the table on the side being tested. (The client may also be seated, with the side being tested resting on the treatment table, which is at axillary height, the humerus in 90-degree abduction, the elbow extended, and the forearm in neutral position.7)

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the humerus. The stabilizing hand can be used simultaneously for palpation here.

3. Palpate: Palpate the biceps as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client flexing the elbow, with the hand toward the shoulder.10 Watch for maintenance of forearm supination and relaxation of the fingers and wrist (Figure 22-14, C).15

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: The brachioradialis will substitute for the biceps, but the forearm will move to midposition during flexion of the elbow. Wrist and finger flexors may assist elbow flexion, which will be preceded by finger and wrist flexion.10,12,13,15 The pronator teres may assist. Forearm pronation during movement may be evidence of this substitution.15

Elbow Extension

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is prone, with the humerus abducted to 90 degrees, the elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and the forearm in neutral rotation and perpendicular to the floor. The therapist stands next to the client, just behind the arm to be tested.7,14,20

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the humerus by placing one hand for support under it, between the client’s arm and the table.12,14

3. Palpate: Palpate the triceps over the middle of the posterior aspect of the humerus or the triceps tendon just proximal to the olecranon process on the dorsal surface of the arm.6,7,10,15

4. Observe: Observe the client extending the elbow to just less than maximal range. The wrist and fingers remain relaxed (Figure 22-15, A).

5. Resist: Provide resistance at the distal end of the forearm into elbow flexion. Before resistance is given, be sure that the elbow is not locked. Resistance to a locked elbow can cause joint injury (Figure 22-15, B).6,10

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is supine, with the humerus abducted to 90 degrees and in external rotation, the elbow fully flexed, and the forearm supinated. The therapist is standing next to the client, just behind the arm to be tested.10 An alternate position is with the client seated, shoulder abducted to 90 degrees in neutral rotation, elbow flexed, and forearm in neutral position, supported by the therapist.7,10,12

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the humerus by holding one hand over the middle or distal end to prevent shoulder motion.

3. Palpate: Palpate the triceps as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client extending the elbow, moving the hand away from the head (Figure 22-15, C).

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: Finger and wrist extensors may substitute for weak elbow extensors. Observe for the presence of finger and wrist extension preceding elbow extension. When the client is upright, gravity and eccentric contraction of the biceps will effect elbow extension from the flexed position.15 Scapula depression with shoulder external rotation aided by gravity is another effective substitution pattern for elbow extension.6

Forearm Supination

| Muscles4,10,13 | Innervation6,10,13 |

| Biceps brachii | Musculocutaneous nerve, C5,6 |

| Supinator | Radial nerve, C5-7 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is seated, with the humerus adducted, the elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and the forearm pronated. The therapist stands in front of the client or next to the client on the side to be tested.6,7,10,12,13

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the humerus just proximal to the elbow.6,10

3. Palpate: Palpate the client over the supinator muscle on the dorsal-lateral aspect of the forearm, below the head of the radius. The muscle can be best felt when the radial muscle group (extensor carpi radialis and brachioradialis) is pushed up out of the way.4 The therapist may also palpate the biceps at the middle of the anterior surface of the humerus.6,7

4. Observe: Observe the client supinating the forearm, turning the hand palm up. Because gravity assists movement, after the 0-degree neutral position is passed, the therapist may apply slight resistance equal to the weight of the forearm (Figure 22-16, A).6,7

5. Resist: Provide resistance by grasping around the dorsal aspect of the distal forearm with the fingers and heel of the hand, while turning the arm toward pronation (Figure 22-16, B).6

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated, shoulder flexed to 90 degrees and the upper arm resting on the supporting surface, elbow flexed to 90 degrees; the forearm is in full pronation in a position perpendicular to the floor.6,7,20 The therapist stands next to the client on the side to be tested.

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the humerus just proximal to the elbow.6

3. Palpate: Palpate the supinator or biceps as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe the client supinating the forearm, turning the palm of the hand toward the face (Figure 22-16, C).

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: With the elbow flexed, external rotation and horizontal adduction of the humerus will effect forearm supination. With the elbow extended, shoulder external rotation will place the forearm in supination. The brachioradialis can bring the forearm from full pronation to midposition. Wrist and thumb extensors, assisted by gravity, can initiate supination. The therapist should note any external rotation of the humerus, supination to midline only, and initiation of motion by wrist and thumb extension.10,13,15,20

Forearm Pronation

| Muscles4,12,13,15 | Innervation12,14 |

| Pronator teres | Median nerve, C6,7 |

| Pronator quadratus | Median nerve, C6-8 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is seated with the humerus adducted, the elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and the forearm in full supination. The therapist stands beside the client on the side to be tested.6,7,10,13

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the humerus just proximal to the elbow to prevent shoulder abduction.6,7,10,14

3. Palpate: Palpate the pronator teres on the upper part of the volar surface of the forearm, medial to the biceps tendon and diagonally from the medial condyle of the humerus to the lateral border of the radius.7,10,14,15

4. Observe: Observe the client pronating the forearm, turning the hand palm down (Figure 22-17, A).10 Slight resistance may be applied after the arm has passed midposition to compensate for the assistance of gravity after that point.6

5. Resist: Provide resistance by grasping over the dorsal aspect of the distal forearm, using the fingers and heel of the hand and turning toward supination (Figure 22-17, B).

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated, shoulder flexed to 90 degrees, elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and the forearm in full supination. The upper arm is resting on the supporting surface, and the forearm is perpendicular to the floor.20 The therapist stands next to the client on the side to be tested.

2. Palpate: Palpate the pronator teres as described for the previous test.

3. Observe: Observe the client pronating the forearm, turning the palm of the hand away from the face (Figure 22-17, C).

4. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: With the elbow flexed, internal rotation and abduction of the humerus will produce apparent forearm pronation. With the elbow extended, internal rotation can place the forearm in a pronated position. Brachioradialis can bring the fully supinated forearm to midposition. Wrist flexion, aided by gravity, can effect pronation.6,7,10,12,13,15,20

Wrist Extension With Radial Deviation

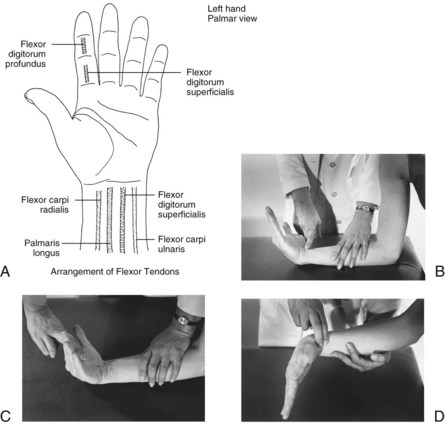

| Muscles10,12,14 | Innervation6,12 |

| Extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) | Radial nerve, C5-7 |

| Extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) | Radial nerve, C6-8 |

| Extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is seated or supine with the forearm resting on the supporting surface in pronation, the wrist at neutral, and the fingers and thumb relaxed. The therapist sits opposite to or next to the client on the side to be tested.10,14

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the volar or dorsal aspect of the distal forearm.6,10,14

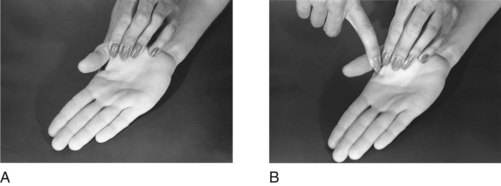

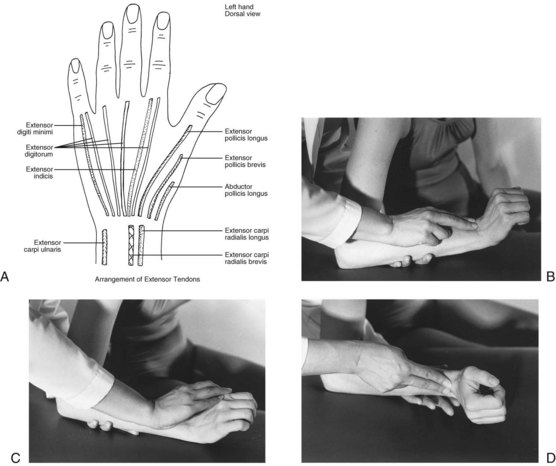

3. Palpate: Palpate the ECRL and ECRB tendons on the dorsal aspect of the wrist at the bases of the second and third metacarpals, respectively.6,7,10 The tendon of the ECU may be palpated at the base of the fifth metacarpal, just distal to the head of the ulna (Figure 22-18, A).4,6,10,15

FIGURE 22-18 A, Arrangement of extensor tendons at wrist. B, Wrist extension with radial deviation. Palpate and observe. C, Resist. D, Gravity-minimized position.

4. Observe: Observe the client extending and radially deviating the wrist, while lifting the hand from the supporting surface and simultaneously moving it medially (to the radial side). The movement should be performed without finger extension, which could substitute for the wrist motion (Figure 22-18, B).6,10,15

5. Resist: Provide resistance over the dorsum of the second and third metacarpals, toward flexion and ulnar deviation (Figure 22-18, C).6,10,12–14

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is placed in the same manner as described for the previous test, except that the forearm is resting in midposition on its ulnar border.10,20

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization at the ulnar border of the forearm, supported slightly above the table surface.10

3. Palpate: Palpate radial wrist extensors as described for the previous test.

4. Observe: Observe client extending the wrist, moving the hand away from the body (Figure 22-18, D).

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: Wrist extensors can substitute for one another. In the absence of the extensor carpi radialis muscles, the extensor carpi ulnaris will extend the wrist, but in an ulnar direction. Combined extension and radial deviation will not be possible. The extensor digitorum communis muscle and the extensor pollicis longus can initiate wrist extension, but finger or thumb extension will precede wrist extension.6,7,12,13,15,20

Wrist Extension With Ulnar Deviation

| Muscles10,12–14 | Innervation10,14 |

| Extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) | Radial nerve, C6-8 |

| Extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) | |

| Extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL) | Radial nerve, C5-7 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is seated, forearm pronated, wrist neutral, fingers and thumb relaxed, supported on a table. The therapist sits opposite or next to the client on the side to be tested.

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization under the distal forearm.10,12–14

3. Palpate: Palpate the ECU tendon at the base of the fifth metacarpal, just distal to the ulnar styloid,6 and the ECRL and ECRB tendons at the bases of the second and third metacarpals.

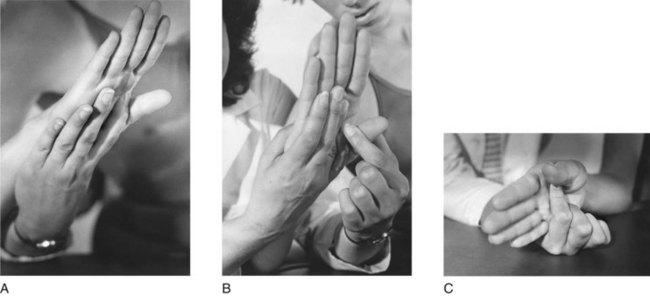

4. Observe: Observe the client extending the wrist and simultaneously moving it laterally (to the ulnar side). The therapist should observe that movement is not preceded by thumb or finger extension (Figure 22-19, A).6,10,12,13,15

FIGURE 22-19 Wrist extension with ulnar deviation. A, Palpate and observe. B, Resist. C, Gravity-minimized position.

5. Resist: Provide resistance over the dorsal-lateral aspect of the fourth and fifth metacarpals toward flexion and radial deviation (Figure 22-19, B).6,10,14

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is placed in the same manner as that described for the previous test, except that the forearm is in 45 degrees of pronation and is supported on a table. The wrist is flexed and radially deviated, and the thumb and fingers are flexed.6

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization under the distal forearm, supporting it slightly above the supporting surface.10,14

3. Palpate: Palpate the extensor tendons as described previously.

4. Observe: Observe client extending the wrist and moving it ulnarly at the same time (Figure 22-19, C).

5. Grade: The client is graded according to standard definitions of muscle grades.

Substitutions: In the absence of the ECU muscle, the ECRL and ECRB muscles can extend the wrist but will do so in a radial direction. The ulnar deviation component of the test motion will not be possible. Long finger and thumb extensors can initiate wrist extension, but the movement will be preceded by finger or thumb extension.6,7,12,13,15,20

Wrist Flexion With Radial Deviation

| Muscles12,14 | Innervation5,6,10 |

| Flexor carpi radialis (FCR) | Median nerve, C6-8 |

| Flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) | Ulnar nerve, C7-T1 |

| Palmaris longus | Median nerve, C7-T1 |

Procedure for Testing Grades N (5) to F (3)

1. Position: The client is seated or supine, with the forearm resting in nearly full supination on the supporting surface, fingers and thumb relaxed.7,12,15 The therapist is seated next to the client on the side to be tested.

2. Stabilize: Provide stabilization over the volar aspect of the midforearm.6,10,14

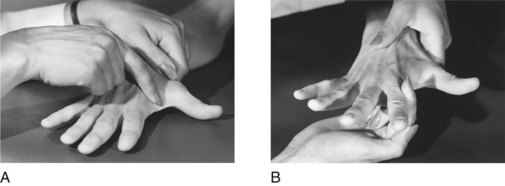

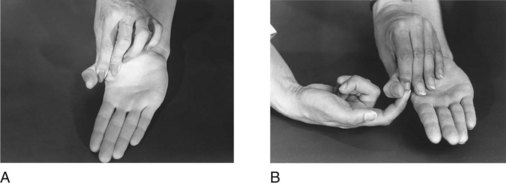

3. Palpate: The FCR tendon can be palpated over the wrist at the base of the second metacarpal bone. The palmaris longus tendon is at the center of the wrist at the base of the third metacarpal, and the FCU tendon can be palpated at the ulnar side of the volar aspect of the wrist, at the base of the fifth metacarpal (Figure 22-20, A).4

FIGURE 22-20 A, Arrangement of flexor tendons at wrist. B, Wrist flexion with radial deviation. Palpate and observe. C, Resist. D, Gravity-minimized position.

4. Observe: Observe the client simultaneously flexing and radially deviating the hand. The therapist should observe that the fingers remain relaxed during the movement6 (Figure 22-20, B).

5. Resist: Provide resistance in the palm at the radial side of the hand, over the second and third metacarpals toward extension and ulnar deviation (Figure 22-20, C).6

Procedure for Testing Grades P (2), T (1), and 0

1. Position: The client is seated with the forearm in midposition and the ulnar border of the hand resting on the supporting surface.10,20 The therapist sits next to the client on the side to be tested.