Introduction to Quantitative Research

What do you think of when you hear the word research? Frequently, the word experiment comes to mind. One might equate experiments with randomizing subjects into groups, collecting data, and conducting statistical analyses. Many people believe that an experiment is conducted to “prove” something, such as that one pain medicine is more effective than another. These common notions are associated with the classic experimental design originated by Sir Ronald Fisher (1935). Fisher is noted for adding structure to the steps of the research process with ideas such as the null hypothesis, research design, and statistical analysis.

Fisher’s experimentation provided the groundwork for what is now known as experimental research. Throughout the years, other quantitative approaches have been developed. Campbell and Stanley (1963) developed quasi-experimental approaches. Karl Pearson developed statistical approaches for examining relationships among variables, which increased the conduct of correlational research. The fields of sociology, education, and psychology are noted for their development and expansion of strategies for conducting descriptive research. The steps of the research process used in these different types of quantitative study are the same, but the philosophy and strategies for implementing these steps vary with the approach.

Many quantitative research approaches are essential to develop the body of knowledge needed for evidence-based practice. Thus, quantitative research is a major focus throughout this textbook. This chapter provides an overview of quantitative research by (1) discussing concepts relevant to quantitative research, (2) identifying the steps of the quantitative research process, and (3) providing examples of different types of quantitative studies.

CONCEPTS RELEVANT TO QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

Some concepts relevant to quantitative research are basic research, applied research, rigor, and control. These concepts are defined, and major points are reinforced with examples from quantitative studies.

Basic Research

Basic, or pure, research is a scientific investigation that involves the pursuit of “knowledge for knowledge’s sake,” or for the pleasure of learning and finding truth (Nagel, 1961). The purpose of basic research is to generate and refine theory and build constructs; thus, frequently the findings are not directly useful in practice. However, because the findings are more theoretical in nature, they can be generalized to various settings (Wysocki, 1983).

Basic research also examines the underlying mechanisms of actions of an intervention or outcome (Wallenstein, 1987). For example, cachexia in cancer patients clinically presents with anorexia, weight loss, and wasting of skeletal muscles that decrease patients’ functioning and quality of life. What are the pathological mechanisms of cancer cachexia with resulting skeletal muscle wasting? What interventions might be implemented to preserve skeletal muscle mass in patients with cancer? Because little is known about the pathology of cancer cachexia with skeletal muscle wasting and possible treatments for these clinical problems, basic research on animals is needed to generate knowledge in these areas. Graves, Hitt, Pariza, Cook, and McCarthy (2005) conducted basic research to examine the effect of a diet supplemented with 0.5% conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) on muscle wasting in mice with cancer. In this laboratory study, the tumor-bearing mice were experiencing cancer cachexia with progressive weight loss, skeletal muscle wasting, fatigue, and anorexia. CLA was the independent variable or treatment implemented to determine its effect on the dependent or outcome variable of the gastrocnemius muscle mass in mice with and without cancer.

Laboratories with animals often implement basic research to examine the effect of newly proposed interventions. Researchers identified CLA as a potential treatment for cachexia with skeletal muscle wasting and implemented it as a dietary supplement for tumor-bearing mice. Basic research usually precedes or is the basis for applied research. Thus, Graves et al.’s (2005) basic study provides a basis for studying the effects of the CLA dietary supplement on weight loss and skeletal muscle wasting on cancer patients. Graves et al. (2005) found that CLA seems to preserve muscle mass in tumor-bearing mice by reducing the catabolic effects of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) on skeletal muscle. This study increases our understanding of the pathology of cancer cachexia and contributes to the development of dietary treatments to reduce the loss of skeletal muscle mass with cancer. Additional applied research is needed to determine if the CLA dietary supplement preserves muscle mass and maintains weight of cancer patients.

Applied Research

Applied, or practical, research is a scientific investigation conducted to generate knowledge that will directly influence or improve clinical practice. The purpose of applied research is to solve problems, to make decisions, or to predict or control outcomes in real-life practice situations. Because applied research focuses on specific problems, the findings are less generalizable than those from basic research. Applied research is also used to test theory and validate its usefulness in clinical practice. Often, the new knowledge discovered through basic research is examined for usefulness in practice by applied research, making these approaches complementary (Bond & Heitkemper, 1987).

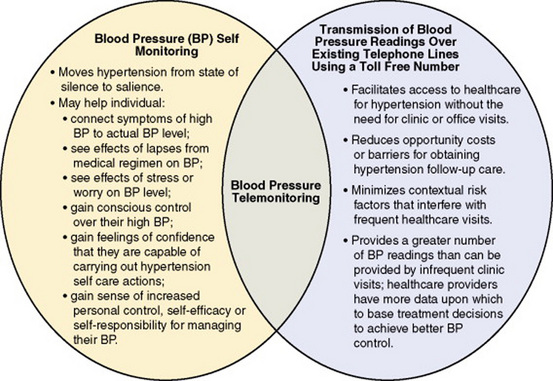

Artinian et al. (2007) conducted an applied study to determine the effectiveness of a nurse-managed telemonitoring (TM) program on the blood pressure (BP) of urban African Americans. The TM program (1) provided BP equipment for patients to monitor their BP at home, (2) improved access to care by sending patients’ BP readings over the phone to health care agencies, and (3) increased monitoring of the patients’ BP by a care provider with immediate feedback to the patient. The treatment group received the nurse-managed TM intervention or treatment, and the comparison group received usual care (UC). The TM treatment group had a significant reduction in systolic BP when compared to the UC group, and their diastolic BP was greatly reduced but was not statistically significant from the comparison group at 12 months. Thus, the TM intervention did have a positive impact on the BPs of African Americans, and additional research is needed to determine if the intervention has a long-term effect on BPs and improves hypertension control in this population. The findings from this applied study do have implications for practice because this nurse-managed TM intervention significantly affected BP in a population with a high incidence of hypertension (Artinian et al., 2007). We will use this quasi-experimental study as an example to reinforce key points throughout this chapter.

Many nurse researchers have conducted applied studies to produce findings that directly affect clinical practice. Usually applied studies focus on developing and testing the effectiveness of nursing interventions in the treatment of patient and family health problems. In addition, most federal funding has been granted for applied research. However, additional basic research is needed to expand our understanding of several pathophysiological variables, such as impaired oxygenation and perfusion, fluid and electrolyte imbalance, altered neurological function, impaired immune system, nutritional disorders, and sleep disturbance. Because the future of any profession rests on its research base, both basic and applied studies are needed to develop knowledge for evidence-based practice in nursing.

Rigor in Quantitative Research

Rigor is the strive for excellence in research and involves discipline, scrupulous adherence to detail, and strict accuracy. A rigorous quantitative researcher constantly strives for more precise measurement methods, structured treatments, representative samples, and tightly controlled study designs. Characteristics valued in these researchers include (1) critical examination of reasoning and (2) attention to precision.

Logistic reasoning and deductive reasoning are essential to the development of quantitative research. The research process consists of specific steps that are developed with meticulous detail and logically linked together. These steps are critically examined and reexamined for errors and weaknesses in areas such as design, treatment implementation, measurement, sampling, statistical analysis, and generalization. Reducing these errors and weaknesses is essential to ensure that the research findings are an accurate reflection of reality.

Another aspect of rigor is precision, which encompasses accuracy, detail, and order. Precision is evident in the concise statement of the research purpose, the detailed development of the study design, and the formulation of explicit treatment protocols. The most explicit use of precision, however, is evident in the measurement of the study variables. Measurement involves objectively experiencing the real world through the senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. The researcher continually searches for new and more precise ways to measure elements and events of the world (Kaplan, 1964).

Control in Quantitative Research

Control occurs when the researcher imposes “rules” to decrease the possibility of error and thus increase the probability that the study’s findings are an accurate reflection of reality. The rules used to achieve control are referred to as design. Through control, the researcher can reduce the influence or confounding effect of extraneous variables on the study variables. For example, if a study focused on the effect of relaxation therapy on the perception of incisional pain, the extraneous variables, such as type of surgical incision and the timing, amount, and type of pain medicine administered after surgery, would have to be controlled to prevent them from influencing the patient’s perception of pain.

Controlling extraneous variables enables the researcher to identify relationships among the study variables accurately and examine the effects of one variable on another. Researchers can control extraneous variables by randomly selecting a certain type of subject, such as only those individuals who are having abdominal surgery or those with a certain medical diagnosis. The selection of subjects is controlled with sample criteria and sampling method. The setting can also be structured to control extraneous variables such as temperature, noise, and interactions with other people. The data collection process can be sequenced to control extraneous variables such as fatigue and discomfort.

Quantitative research requires varying degrees of control, ranging from minimal control to highly controlled, depending on the type of study (Table 3-1). Descriptive studies are usually conducted with minimal control of the study design, because subjects are examined as they exist in their natural setting, such as home, work, or school. However, the researcher still hopes to achieve the most precise measurement of the research variables as possible. Experimental studies are highly controlled and often conducted on animals in laboratory settings to determine the underlying mechanisms for and effectiveness of a treatment. Some common areas in which control might be enhanced in quantitative research are (1) selection of subjects (sampling), (2) selection of the research setting, (3) development and implementation of a treatment or intervention, (4) measurement of study variables, and (5) subjects’ knowledge of the study.

TABLE 3-1

Control in Quantitative Research

| Type of Research | Control in Development of the Research Design |

| Descriptive research | Minimal or partial control |

| Correlational research | Minimal or partial control |

| Quasi-experimental research | Moderate control |

| Experimental research | High control |

Sampling

Sampling is a process of selecting subjects, events, behaviors, or elements for participation in a study. In performing quantitative research, you will use both random and nonrandom sampling methods to obtain study samples. Random sampling methods usually provide a sample that is representative of a population, because each member of the population has a probability greater than zero of being selected for a study. Thus, random or probability sampling methods require greater researcher control and rigor than nonrandom or nonprobability sampling methods (see Chapter 14).

Research Settings

There are three common settings for conducting research: natural, partially controlled, and highly controlled. Natural settings are uncontrolled, real-life settings where studies are conducted (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). Descriptive and correlational types of quantitative research are often conducted in natural settings. A partially controlled setting is an environment that the researcher manipulates or modifies in some way. An increasing number of quasi-experimental studies are being conducted to test the effectiveness of nursing interventions, and these studies are often conducted in partially controlled settings. Highly controlled settings are artificially constructed environments that are developed for the sole purpose of conducting research. Laboratories, research or experimental centers, and test units are highly controlled settings often used for the conduct of experimental research. Chapter 14 discusses the process for selecting a setting for the conduct of quantitative and qualitative research.

Development and Implementation of Study Interventions or Treatments

Quasi-experimental and experimental studies examine the effect of an independent variable or intervention on a dependent variable or outcome. More intervention studies are being conducted in nursing to establish an evidence-based practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). Controlling the development and implementation of a study intervention increases the validity of the study design and the credibility of the findings (Ryan & Lauver, 2002). A study intervention must be (1) clearly and precisely developed, (2) consistently implemented with protocol, and (3) examined for effectiveness through quality measurement of the dependent variables (Santacroce, Maccarelli, & Grey, 2004; Sidani & Braden, 1998). Artinian et al. (2007) provided the following detailed description of the implementation of the nurse-managed TM (telemonitoring) intervention to improve the BPs of African-American subjects:

Participants in the TM group received UC [usual care] plus nurse-managed TM. Specially trained registered nurses delivered the intervention. During a prescheduled appointment, the intervention nurse delivered the BP monitor and TM link device (device that links BP monitor to the telephone) to the participant’s home. At the time of the home visit, an intervention nurse taught participants how to self-monitor BP in accordance with The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC VII) guidelines (Chobanian et al., 2003), set up the home TM system, demonstrated the system, had participants practice using the BP monitor, and answered questions. Given the memory in the BP monitor and that all BPs recorded by the monitor were telephonically sent to care providers and the principal investigator, participants received verbal and written reminders that the BP monitor was exclusively for their use … LifeLink Monitoring, Inc. (Bearsville, NY) provided TM services for this study.… Telemonitoring participants were also asked to telephonically send their BP readings to the intervention nurse and their care providers.… Once the intervention nurses received the BP reports, they telephoned each participant to provide feedback in relation to the target goals and to provide telecounseling about lifestyle modification and medication adherence in accordance with JNC-VII guidelines (Chobanian et al., 2003). (Artinian, 2007, p. 315)

Measurement of Study Variables

When you are conducting a quantitative study, you will attempt to use the most precise instruments available to measure the study variables. Using a variety of quality measurement methods promotes an accurate and comprehensive understanding of the study variables. In addition, researchers want to rigorously control the process for measuring study variables to improve the design validity and quality of the study findings. Artinian et al. (2007) described their precise measurement of the dependent variable, BP, with a valid, nationally standardized device:

The outcome measure of the BP was measured with electronic BP monitor (Omron HEM-737 Intellisense, Omron Healthcare, Inc., Vernon Hills, IL) that has been validated in accordance with the criteria of the British Hypertension Society and the Association of the Advancement of Medical Instrumentations (Dabl Educational Trust, 2005). (Artinian et al., 2007, p. 316)

Measurement concepts, process, and strategies are the foci of Chapters 15 and 16.

Subjects’ Knowledge of a Study

Subjects’ knowledge of a study could influence their behavior and possibly alter the research outcomes. This threatens the validity or accuracy of the study design. An example of this type of threat to design validity is the Hawthorne effect, which was identified during the classic experiments at the Hawthorne plant of the Western Electric Company during the late 1920s and early 1930s. The employees at this plant exhibited a particular psychological response when they became research subjects: They changed their behavior simply because they were subjects in a study, not because of the research treatment. In these studies, the researcher manipulated the working conditions (altered the lighting, decreased work hours, changed payment, and increased rest periods) to examine the effects on worker productivity (Homans, 1965). The subjects in both the treatment group (whose work conditions were changed) and the control group (whose work conditions were not changed) increased their productivity. The subjects seemed to change their behaviors (increase their productivity) solely in response to being part of a study. In the study by Artinian et al. (2007, p. 321), both the treatment and the comparison groups experienced decreases in their blood pressures and the researchers indicated “the Hawthorne effect may have been a factor, with participants paying more attention to their BP and hypertension self-care behaviors because they were aware of their participation in the study.”

There are several ways to strengthen a study by decreasing the threats to design validity and selecting the strongest design for the proposed study. Chapter 10 addresses design validity, and Chapter 11 focuses on the process for selecting an appropriate study design. Your understanding of rigor and control provide the basis for the implementation of the steps of the quantitative research process, which are precisely executed in descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental research.

STEPS OF THE QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH PROCESS

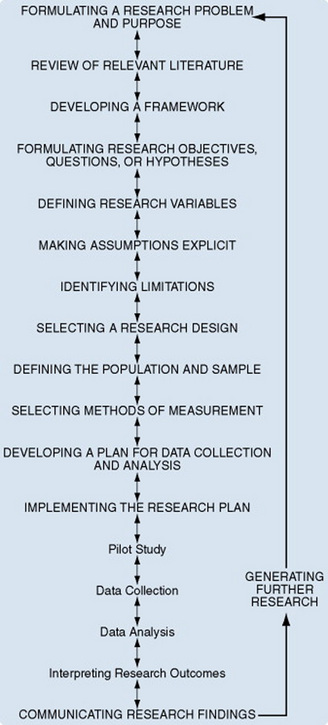

The quantitative research process involves conceptualizing a research project, planning and implementing that project, and communicating the findings. Figure 3-1 identifies the steps of the quantitative research process and shows the logical flow of this process as each step progressively builds on the previous steps. This research process is also flexible and fluid, with a flow back and forth among the steps as the researcher strives to clarify the steps and strengthen the proposed study. This flow back and forth among the steps is indicated in the figure by the two-way arrows connecting the steps of the process. Figure 3-1 also contains a feedback arrow, which indicates that the research process is cyclical, for each study provides a basis for generating further research in the development of knowledge for evidence-based practice.

In this chapter, we briefly introduce you to the steps of the quantitative research process, and we present them in detail in Unit Two, The Research Process (

Chapter 5 through 22, 24, and 25). The descriptive correlational study conducted by Hulme and Grove (1994), on the symptoms of female survivors of child sexual abuse, is used as an example for introducing the steps of the research process; quotations from and descriptions of this study appear throughout this section.

Formulating a Research Problem and Purpose

A research problem is an area of concern where there is a gap in the knowledge base needed for nursing practice. The problem identifies an area of concern for a particular population and often indicates the concepts to be studied. The major sources for nursing research problems include nursing practice, researcher and peer interactions, literature review, theory, and research priorities. As a researcher, you will use deductive reasoning to generate a research problem from a research topic or a broad problem area of personal interest that is relevant to nursing.

The research purpose is generated from the problem and identifies the specific goal or aim of the study. The goal of a study might be to identify, describe, explain, or predict a solution to a situation. The purpose often indicates the type of study to be conducted (descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, or experimental) and usually includes the variables, population, and setting for the study.

As the clarity and conciseness of a research problem and purpose improve, you will be able to determine the feasibility of conducting the study. Chapter 5 provides a background for formulating a research problem and purpose. Hulme and Grove (1994) identified the following problem and purpose for their study of female survivors of child sexual abuse.

The research purpose clearly indicates that the focus of this study is both descriptive and correlational.

Review of Relevant Literature

A review of relevant literature is conducted to generate an understanding of what is known about a particular situation or phenomenon and the knowledge gaps that exist. Relevant literature refers to those sources that are pertinent or highly important in providing the in-depth knowledge needed to study a selected problem. This background enables you as a researcher to build on the works of others. The concepts and interrelationships of the concepts in the problem will guide your selection of relevant theories and studies for review. We review theories to clarify the definitions of concepts and to develop and refine the study framework.

By reviewing relevant studies, you will be able to clarify (1) which problems have been investigated, (2) which require further investigation or replication, and (3) which have not been investigated. In addition, the literature review can direct you in designing the study and interpreting the outcomes (see Chapter 6). Hulme and Grove’s (1994) review of the literature covered relevant theories and studies related to child sexual abuse and its contributing factors and long-term effects, as shown in the following extracts:

Developing a Framework

A framework is the abstract, logical structure of meaning that will guide the development of your study and enable you as the researcher to link the findings to the body of knowledge used in nursing practice. In quantitative research, the framework is often a testable midrange theory that has been developed in nursing or in another discipline, such as psychology, physiology, or sociology. The framework may also be developed inductively from clinical observations.

The terms related to frameworks are concept, relational statement, theory, and framework map. A concept is a term to which abstract meaning is attached. A relational statement or proposition declares that a relationship of some kind exists between two or more concepts. A theory consists of an integrated set of defined concepts and propositions that present a view of a phenomenon and can be used to describe, explain, predict, or control the phenomenon. The propositions or relationship statements of the theory, not the theory itself, are tested through research.

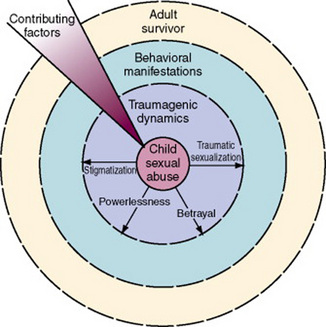

A study framework can be expressed as a map or a diagram of the relationships that provide the basis for a study or can be presented in narrative format. The steps for developing a framework are described in Chapter 7. The framework for Hulme and Grove’s (1994) study, described in the following quotation, is based on Browne and Finkelhor’s (1986) theory of traumagenic dynamics in the impact of child sexual abuse.

Formulating Research Objectives, Questions, or Hypotheses

Research objectives, questions, and hypotheses bridge the gap between the more abstractly stated research problem and purpose and the study design and plan for data collection and analysis. Objectives, questions, and hypotheses are narrower in focus than the research purpose and often (1) specify only one or two research variables, (2) identify the relationship between the variables, and (3) indicate the population to be studied.

Some quantitative studies do not include objectives, questions, or hypotheses; the development of such a study is directed by the research purpose. Many descriptive studies include only a research purpose, and other descriptive studies include a purpose and objectives or questions. Some correlational studies include a purpose and specific questions or hypotheses. Quasi-experimental and experimental studies often use hypotheses to direct the development and implementation of the studies and the interpretation of findings. Chapter 8 examines the development of research objectives, questions, and hypotheses. Hulme and Grove (1994) developed the following research questions to direct their descriptive-correlational study.

The focus of question 1 is description and that of question 2 is correlation, or examination of relationships.

Defining Research Variables

The research purpose and the objectives, questions, or hypotheses identify the variables you will be examining in your study. Research variables are concepts of various levels of abstraction that are measured, manipulated, or controlled in a study. The more concrete concepts, such as temperature, weight, and blood pressure, are referred to as “variables.” The more abstract concepts, such as creativity, empathy, and social support, are sometimes referred to as “research concepts.”

The variables or concepts in a study are operationalized when they are conceptually and operationally defined. A conceptual definition provides a variable or concept with theoretical meaning (Fawcett, 1999) and either is derived from a theorist’s definition of the concept or is developed through concept analysis. An operational definition allows the variable to be measured or manipulated in a study. The knowledge you gain from studying the variable will increase your understanding of the theoretical concept that the variable represents (see Chapter 8).

Hulme and Grove (1994) provided conceptual and operational definitions of the study variables identified in their purpose and research questions: physical and psychosocial symptoms, age when abuse began, duration of abuse, and multiple victimizations. Only the definitions for physical symptoms and multiple victimizations are presented as examples here.

Making Assumptions Explicit

Assumptions are statements that are taken for granted or are considered true, even though they have not been scientifically tested (Silva, 1981). Assumptions are often embedded (unrecognized) in thinking and behavior, and uncovering them requires introspection. Sources of assumptions include universally accepted truths (e.g., all humans are rational beings), theories, previous research, and nursing practice (Myers, 1982).

In studies, assumptions are embedded in the philosophical base of the framework, study design, and interpretation of findings. Theories and instruments are developed on the basis of assumptions that the researcher may or may not recognize. These assumptions influence the development and implementation of the research process. Being able to recognize assumptions is a strength, not a weakness. Assumptions influence the logic of the study, so their recognition leads to more rigorous study development.

Williams (1980) reviewed published nursing studies and other health care literature to identify commonly embedded assumptions, which include the following:

1. People want to assume control of their own health problems.

3. People are aware of the experiences that most affect their life choices.

4. Health is a priority for most people.

5. People in underserved areas feel underserved.

6. Most measurable attitudes are held strongly enough to direct behavior.

7. Health professionals view health care in a different manner than do lay persons.

8. People operate on the basis of cognitive information.

9. Increased knowledge about an event lowers anxiety about the event.

10. Receipt of health care at home is preferable to receipt of care in an institution. (Williams, 1980, p. 48)

Hulme and Grove (1994) did not identify assumptions for their study, but the following assumptions seem to provide a basis for it: (1) the child victim bears no responsibility for the sexual contact, (2) some survivors remember and are willing to report their past child sexual abuse, and (3) physical and psychological signs and symptoms indicate lack of optimal health and functioning.

Identifying Limitations

Limitations are restrictions or problems in a study that may decrease the generalizability of the findings. The two types of limitations are theoretical and methodological.

Theoretical limitations are weaknesses in a study framework and conceptual and operational definitions of variables that restrict the abstract generalization of the findings. Theoretical limitations include the following:

1. A concept might not be clearly defined in the theory used to develop the study framework.

2. The relationships among some concepts might not be identified or are unclear in the theorist’s work.

3. A study variable might not be clearly linked to a concept in the framework.

4. An objective, question, or hypothesis might not be clearly linked to a relationship or proposition in the study framework.

Methodological limitations are weaknesses in the study design that can limit the credibility of the findings and restrict the population to which the findings can be generalized. Methodological limitations result from factors such as unrepresentative samples, weak designs, single setting, limited control over treatment (intervention) implementation, instruments with limited reliability and validity, limited control over data collection, and improper use of statistical analyses. Limitations regarding design (see Chapter 10), sampling (see Chapter 14), measurement (see Chapter 15), and data collection (see Chapter 17) are discussed later in this text. Some theoretical and methodological limitations are identified before the conduct of the study, and researchers minimize these limitations as much as possible. However, some limitations are not identified until the study is conducted and are identified in the discussion section of the study report with implications of how they might have influenced the study findings. Hulme and Grove (1994) identified the following methodological limitation.

Selecting a Research Design

A research design is a blueprint for maximizing control over factors that could interfere with a study’s desired outcome. The type of design directs the selection of a population, sampling procedure, methods of measurement, and a plan for data collection and analysis. The choice of research design depends on the researcher’s expertise, the problem and purpose for the study, and the desire to generalize the findings.

Designs have been developed to meet unique research needs as they emerge; thus, a variety of descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental designs have been generated over time. In descriptive and correlational studies, no treatment is administered, so the study design centers on improving the precision of measurement. Quasi-experimental and experimental study designs usually involve treatment and control groups and focus on achieving high levels of control, as well as precision in measurement (Cook & Campbell, 1963, Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). Chapter 10 covers the purpose of a design and the threats to design validity. Chapter 11 presents models and descriptions of several types of descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental designs.

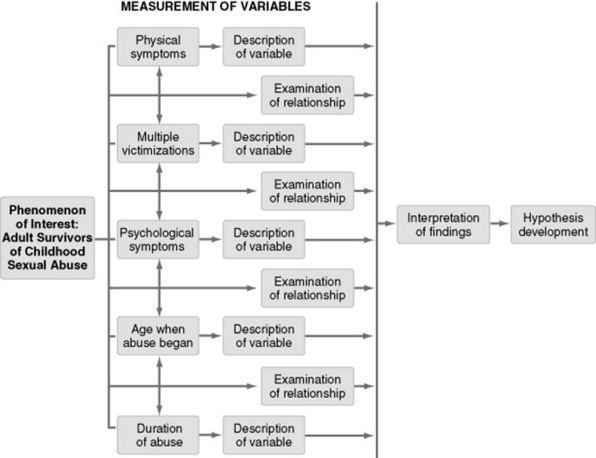

Hulme and Grove (1994) used a descriptive correlational design to direct their study. A diagram of the design, presented in Figure 3-3, identifies the phenomenon of interest (adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse); variables measured and described (physical symptoms, multiple victimization, psychological symptoms, age when abuse began, and duration of abuse); and the relationships examined among variables. The findings generated from descriptive-correlational research provide a basis for generating hypotheses for testing in future research.

Figure 3-3 Proposed descriptive correlational design for the Hulme and Grove (1994) study of symptoms of female survivors of child sexual abuse.

Defining the Population and Sample

The population is all the elements (individuals, objects, or substances) that meet certain criteria for inclusion in a given universe (Kaplan, 1964; Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). For example, suppose you wanted to conduct a study to describe patients’ responses to nurse practitioners as their primary care providers. You could define the population in different ways: It could include all patients being seen for the first time in (1) a single clinic, (2) all clinics in a specific network in one city, or (3) all clinics in that network nationwide. Your definition of the population would depend on the sample criteria and the similarity of subjects in these various settings. The researcher must determine which population is accessible and can be best represented by the study sample.

A sample is a subset of the population that is selected for a particular study, and sampling defines the process for selecting a group of people, events, behaviors, or other elements with which to conduct a study. Nursing studies use both probability (random) and nonprobability (nonrandom) sampling methods (see Chapter 14). The following quotation identifies the sampling method, setting, sample size, population, sample criteria, and sample characteristics for the study conducted by Hulme and Grove (1994).

Selecting Methods of Measurement

Measurement is the process of assigning “numbers to objects (or events or situations) in accord with some rule” (Kaplan, 1964, p.177). A component of measurement is instrumentation, which is the application of specific rules to the development of a measurement device or instrument. An instrument is selected to examine a specific variable in a study. Data generated with an instrument are at the nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio level of measurement. The level of measurement, with nominal being the lowest form of measurement and ratio being the highest, determines the type of statistical analyses that you can perform on the data.

Selection of an instrument requires extensive examination of its reliability and validity. Reliability assesses how consistently the measurement technique measures a concept. The validity of an instrument is the extent to which it actually reflects the abstract concept being examined. Chapter 15 introduces the concepts of measurement and explains the different types of reliability and validity for instruments. Chapter 16 provides a background for selecting measurement methods for a study. Hulme and Grove (1994) provided the following description of the ASI Questionnaire that was used to measure their study variables.

Developing a Plan for Data Collection and Analysis

Data collection is the precise, systematic gathering of information relevant to the research purpose or the specific objectives, questions, or hypotheses of a study. The data collected in quantitative studies are usually numerical. Planning data collection will enable you to anticipate problems that are likely to occur and to explore possible solutions. Usually, detailed procedures for implementing a treatment and collecting data are developed, with a schedule that identifies the initiation and termination of the process (see Chapter 17).

Planning data analysis is the final step before the study is implemented. The analysis plan is based on (1) the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses; (2) the data to be collected; (3) research design; (4) researcher expertise; and (5) availability of computer resources.

Several statistical analysis techniques are available to describe the sample, examine relationships, or determine significant differences within studies. Most researchers consult a statistician for assistance in developing an analysis plan.

Implementing the Research Plan

Implementing the research plan involves treatment or intervention implementation, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of research findings, and, sometimes, a pilot study.

Pilot Study

A pilot study is commonly defined as a smaller version of a proposed study conducted to refine the methodology (Van Ort, 1981). It is developed much like the proposed study, using similar subjects, the same setting, the same treatment, and the same data collection and analysis techniques. However, you could use a pilot study to develop various steps in the research process (Prescott & Soeken, 1989). For example, you could conduct a pilot study to develop and refine an intervention or treatment, a measurement method, a data collection tool, or the data collection process. Thus, a pilot study could be used to develop a research plan rather than to test an already developed plan.

Some of the reasons for conducting pilot studies are as follows (Prescott & Soeken, 1989; Van Ort, 1981):

1. To determine whether the proposed study is feasible (e.g., are the subjects available, does the researcher have the time and money to do the study?).

2. To develop or refine a research treatment or intervention.

3. To develop a protocol for the implementation of a treatment.

4. To identify problems with a study design.

5. To determine whether the sample is representative of the population or whether the sampling technique is effective.

6. To examine the reliability and validity of the research instruments.

7. To develop or refine data collection instruments.

8. To refine the data collection and analysis plan.

9. To give the researcher experience with the subjects, setting, methodology, and methods of measurement.

Hayward et al. (2007) believed that conducting a pilot study improved the strength of their study design and directed their development of a quality proposal for a large multisite trial that received external grant support. Thus, as a researcher you conduct pilot studies to improve the development and implementation of your future major studies.

Data Collection

In quantitative research, data collection involves obtaining numerical data to address the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses. To collect data, you must obtain consent or permission from the setting or agency where the study is to be conducted and from potential subjects. Frequently, the subjects are asked to sign a consent form, which describes the study, promises the subjects confidentiality, and indicates that the subjects can stop participation at any time (see Chapter 9).

During data collection, the study variables are measured through a variety of techniques, such as observation, interview, questionnaires, scales, and physiological measurement methods. In a growing number of studies, nurses measure physiological variables with high-technology equipment. The data are collected and recorded systematically for each subject and are organized to facilitate computer entry. Hulme and Grove (1994) identified the following procedure for data collection:

Data Analysis

Data analysis reduces, organizes, and gives meaning to the data. The analysis of data from quantitative research involves the use of (1) descriptive and exploratory procedures (see Chapter 19) to describe study variables and the sample, (2) statistical techniques to test proposed relationships (see Chapter 20), (3) techniques to make predictions (see Chapter 21), and (4) analysis techniques to examine causality (see Chapter 22). Computers are used to perform most analyses, so Chapter 18 provides a background for using computers in research.

The choice of analysis techniques implemented is determined primarily by the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses; the research design; and the level of measurement achieved by the research instruments. Hulme and Grove (1994) chose frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations to answer their research questions.

Interpreting Research Outcomes

The results obtained from data analysis require interpretation to be meaningful. Interpretation of research outcomes involves (1) examining the results from data analysis, (2) exploring the significance of the findings, (3) forming conclusions, (4) generalizing the findings, (5) considering the implications for nursing, and (6) suggesting further studies. Data analysis yields five types of results: significant as predicted by the researcher, nonsignificant, significant but not predicted by the researcher, mixed findings, and unexpected findings. The study results are then translated and interpreted to become findings, and these findings are synthesized to form conclusions. The conclusions provide a basis for identifying nursing implications, generalizing findings, and suggesting further studies (see Chapter 24). In the excerpts that follow, Hulme and Grove (1994) discuss their findings, with implications for nursing and suggestions for further study.

Communicating Research Findings

Research is not considered complete until the findings have been communicated. Communicating research findings involves developing and disseminating a research report to appropriate audiences; the research report is disseminated through presentations and publication (see Chapter 25). The Hulme and Grove (1994) study was presented at a national nurse practitioner conference and published in the Issues in Mental Health Nursing journal.

TYPES OF QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH

This text describes four types of quantitative research: (1) descriptive, (2) correlational, (3) quasi-experimental, and (4) experimental. The level of existing knowledge for the research problem influences the type of research planned. When little knowledge is available, descriptive studies are often conducted. As the knowledge level increases, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental studies are implemented. This section identifies the purpose of each quantitative research approach and presents an example of the steps of the research process from a published quasi-experimental study.

Descriptive Research

The purpose of descriptive research is to explore and describe phenomena in real-life situations. This approach is used to generate new knowledge about concepts or topics about which limited or no research has been conducted. Through descriptive research, concepts are described and relationships are identified that provide a basis for further quantitative research and theory testing. The study by Hulme and Grove (1994) on the symptoms of female survivors of child sexual abuse, which we used earlier in the chapter to illustrate the basic discussion of the steps of the quantitative research process, is a combined descriptive and correlational study. The descriptive aspects of this study can be clearly identified in its purpose, research questions, design, data analysis, and findings.

Correlational Research

Correlational research examines linear relationships between two or more variables and determines the type (positive or negative) and degree (strength) of the relationship. The strength of a relationship varies from -1 (perfect negative correlation) to +1 (perfect positive correlation), with 0 indicating no relationship. The positive relationship indicates that the variables vary together—that is, the two variables either increase or decrease together. The negative or inverse relationship indicates that the variables vary in opposite directions; thus, as one variable increases, the other decreases. The descriptive correlational study conducted by Hulme and Grove (1994), presented earlier in this chapter, provides an example of the steps of the quantitative research process for correlational research.

Quasi-Experimental Research

The purpose of quasi-experimental research is to examine cause-and-effect relationships among selected independent and dependent variables. Quasi-experimental studies in nursing are conducted to determine the effects of nursing interventions or treatments (independent variables) on patient outcomes (dependent variables) (Cook & Campbell, 1979). Artinian et al. (2007) conducted a quasi-experimental study to determine the effects of nurse-managed telemonitoring (TM) on the BP of African-Americans. The steps for this study, which were introduced earlier in this chapter, are described here and illustrated with extracts from the study.

STEPS OF THE RESEARCH PROCESS IN A QUASI-EXPERIMENTAL STUDY

Experimental Research

The purpose of experimental research is to examine cause-and-effect relationships between independent and dependent variables under highly controlled conditions (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). The researcher exerts high control over the planning and implementation of experimental studies, and often these studies are conducted in a laboratory setting on animals or objects. The Graves et al. (2005) study introduced earlier in this chapter is an experimental study of the effect of a diet supplemented with 0.5% conjugated linoleic acid (CLA) on muscle mass in mice with cancer that was conducted in a laboratory setting. To improve your understanding of the steps of the research process, read this study and identify the steps of quantitative research process outlined in this chapter.

SUMMARY

• Nurses use a broad range of quantitative approaches—including descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental—to develop nursing knowledge.

• Some of the concepts relevant to quantitative research are (1) basic and applied research, (2) rigor, and (3) control.

• Basic, or pure, research is a scientific investigation that involves the pursuit of “knowledge for knowledge’s sake” or for the pleasure of learning and finding truth.

• Applied, or practical, research is a scientific investigation conducted to generate knowledge that will directly influence or improve clinical practice.

• Rigor involves discipline, scrupulous adherence to detail, and strict accuracy.

• Control involves the imposing of “rules” by the researcher to decrease the possibility of error and thus increase the probability that the study’s findings are an accurate reflection of reality.

• The quantitative research process involves conceptualizing a research project, planning and implementing that project, and communicating the findings.

• The steps of the quantitative research process are as follows:

1. Formulating a research problem and purpose identifies an area of concern and the specific goal or aim of the study.

2. Reviewing relevant literature allows the researcher to build a picture of what is known about a particular situation or phenomenon and identify the knowledge gaps that exist.

3. Developing a framework guides the development of the study and enables the researcher to link the findings to the body of knowledge in nursing.

4. Formulating research objectives, questions, or hypotheses allows the researcher to bridge the gap between the more abstractly stated research problem and purpose and the study design and plan for data collection and analysis.

5. Operationalizing research variables involves developing a conceptual definition and operational definition for each variable.

6. Identifying theoretical and methodological limitations involves determining the restrictions in a study that may decrease the generalizability of the findings.

7. Selecting a research design directs the selection of a population, sampling procedure, methods of measurement, and a plan for data collection and analysis.

8. Defining the population and sample determines who will participate in the study.

9. Selecting methods of measurement involves determining the best method(s) to measure each study variable.

10. Developing a plan for data collection and analysis directs the precise, systematic gathering of information relevant to the research purpose or the specific objectives, questions, or hypotheses of a study and involves the selection of appropriate statistical techniques to analyze the study data.

11. Implementing the research plan involves treatment implementation, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of research outcomes.

12. Communicating findings includes the development and dissemination of a research report to appropriate audiences through presentations and publication.

• This chapter introduces four types of quantitative research: descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, and experimental. Examples from published studies are used to illustrate the steps of the quantitative research process.

REFERENCES

American Heart Association. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2005 update. Dallas, TX: Author, 2004.

American Health Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2006 update. Circulation. 2006;113(6):e85–e152.

Artinian, N.T., Flack, J.M., Nordstrom, C.K., Hockman, E.M., Washington, O.G.M., Jen, K.C., et al. Effects of nurse-managed telemonitoring on blood pressure at 12-month follow-up among urban African Americans. Nursing Research. 2007;56(5):312–322.

Artinian, N.T., Washington, O.G., Klymko, K.W., Marbury, C.M., Miller, W.M., Powell, J.L. What you need to know about home blood pressure telemonitoring, but may not know to ask. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2004;22(10):680–686.

Artinian, N.T., Washington, O.G., Templin, T.N. Effects of home telemonitoring and community-based monitoring on blood pressure control in urban African Americans: A pilot study. Heart & Lung. 2001;30(3):191–199.

Bagley, C. Development of a measure of unwanted sexual contact in childhood, for use in community health surveys. Psychology Reports. 1990;66(2):401–402.

Bagley, C., King, K.K. Child sexual abuse: The search for healing. New York: Travistock/Routledge, 1990.

Bond, E.F., Heitkemper, M.M. Importance of basic physiologic research in nursing science. Heart & Lung. 1987;16(4):347–349.

Brown, B.E., Garrison, C.J. Patterns of symptomatology of adult women incest survivors. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1990;12(5):587–600.

Browne, A., Finkelhor, D. Initial and long-term effects: A review of the research. In: Finkelhor D., ed. A source book on child sexual abuse. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1986:143–179.

Campbell, D.T., Stanley, J.C. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1963.

Chobanian, A., Bakris, G., Black, H., Cushman, W., Green, L., Izzo, J., Jr., et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252.

Cook, T.D., Campbell, D.T. Quasi-experimentation: Design and analysis issues for field settings. Chicago: Rand McNally, 1979.

Dabl Educational Trust. Device table: Upper arm devices for self-measurement of blood pressure, 2005. www.dableducational.com/sphygmomanometers.html [Retrieved October 2, 2007, from].

Fawcett, J. The relationship of theory and research, (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 1999.

Fields, L., Burt, V., Cutler, J., Hughers, J., Roccella, E., Sorlie, P. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999–2000: A rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44(4):398–404.

Fisher, R.A., Sir. The designs of experiments. New York: Hafner, 1935.

Follette, N.M., Alexander, P.C., Follette, W.C. Individual predictors of outcome in group treatment for incest survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59(1):150–155.

Graves, E., Hitt, A., Pariza, M.W., Cook, M.E., McCarthy, D.O. Conjugated linoleic acid preserves gastrocnemius muscle mass in mice bearing the colon-26 adenocarcinoma. Nursing Research & Health. 2005;28(1):48–55.

Hayward, K., Campbell-Yeo, M., Price, S., Morrison, D., Whyte, R., Cake, H., et al. Cobedding twins: How pilot study findings guided improvements in planning a larger multicenter trial. Nursing Research. 2007;56(2):137–143.

Homans, G. Group factors in worker productivity. In: Proshansky H., Seidenberg B., eds. Basic studies in social psychology. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1965:592–604.

Hulme, P.A., Grove, S.K. Symptoms of female survivors of child sexual abuse. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1994;15(5):519–532.

Kaplan, A. The conduct of inquiry: Methodology for behavioral science. New York: Chandler, 1964.

Kerlinger, F.N., Lee, H.B. Foundations of behavioral research, (4th ed.). New York: Harcourt Brace; 2000.

Melnyk, B.M., Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Myers, S.T. The search for assumptions. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1982;4(1):91–98.

Nagel, E. The structure of science: Problems in the logic of scientific explanation. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1961.

Prescott, P.A., Soeken, K.L. Methodology corner: The potential uses of pilot work. Nursing Research. 1989;38(1):60–62.

Ryan, P., Lauver, D.R. The efficacy of tailored interventions. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2002;34(4):331–337.

Santacroce, S.J., Maccarelli, L.M., Grey, M. Methods: Intervention fidelity. Nursing Research. 2004;53(1):63–66.

Sidani, S., Braden, C.J. Evaluating nursing interventions: A theory-driven approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

Silva, M.C. Selection of a theoretical framework. In: Krampitz S.D., Pavlovich N., eds. Readings for nursing research. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1981:17–28.

Van Ort, S. Research design: Pilot study. In: Krampitz S.D., Pavlovich N., eds. Readings for nursing research. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby; 1981:49–53.

Wallenstein, S.L. Issues in pain research. Research perspectives: A response. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1987;2(2):103–106.

Williams, M.A., Assumptions in research. Research in Nursing & Health, 3. 1980:47–48. [2].

Wysocki, A.B. Basic versus applied research: Intrinsic and extrinsic considerations. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1983;5(3):217–224.