Chapter 3 Nursing models for practice

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Describe types of nursing theories.

• Define and describe the nature of nursing models.

• Describe the relationship between theory, the nursing process and client needs.

• Describe the historical development of nursing models.

• Discuss selected theories from other disciplines.

• Discuss selected nursing models.

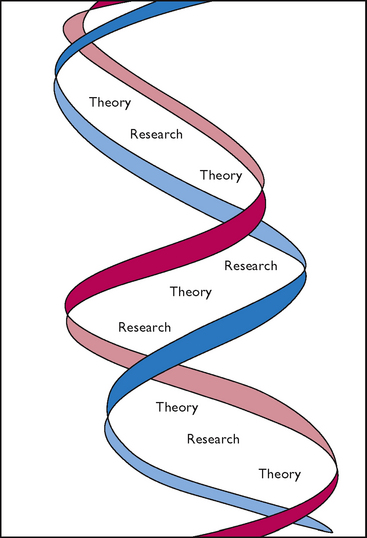

• Describe the relationship between theory and knowledge development in nursing.

Introduction

Since the 1960s, many nurses have attempted to describe the knowledge, skills and actions embedded in the practice of nursing. Thinking about nursing and then trying to construct a picture or a model that accurately and comprehensively reflects the elements of a complex field such as this is not easy; and much effort and energy has been invested in the development of models for nursing practice.

At first sight, nursing science, nursing theory and nursing models are seen to be irrelevant to many nurses and to nursing students. Nursing is essentially a practice that is concerned with the very practical process of delivery of care to people. Because nursing is so practical in its expression, the theories that underpin it and the conceptual frameworks that nurses use (often unconsciously) in their everyday practice are largely invisible. At its simplest level, ‘nursing science’ refers to the knowledge and ideas that underpin the work of nurses. In this chapter, we examine the meaning of science and theory; the role of nursing models in practice; a number of nursing models for practice; and the relationship between nursing models and the practice of nursing.

Nursing’s disciplinary focus

A ‘discipline’ is a branch of knowledge that is based on a system of rules of conduct or methods of practice; and every discipline is characterised by the way it develops its own knowledge base and the focus it has on inquiry (Pearson and others, 2005a). As a discipline, nursing has embraced a wide range of concepts and theories as it has developed into a modern profession, but the development of formal theories and models that attempt to describe nursing is relatively recent. Since the emergence of modern nursing in the 19th century, nurses have pursued a number of different pathways to develop their work (nursing practice) and to generate knowledge and theory (nursing science). Nightingale’s reforms centred on the management theory of the day as well as on everyday understandings of caring, both in the sickroom and in public health. As the occupation of nursing developed, greater emphasis was placed on management, training or education, and the maintenance of the traditions of the occupation. From the 1920s on, nursing practice itself diversified and by the early 1960s nurses in North America began to see the need to develop theoretical understanding of the constructs of nursing. By the 1980s, nurses in Australia, New Zealand, Europe and the United Kingdom had begun to study and to value the practices of nurses.

Alongside this, nurses began to realise that a need existed for a radical reappraisal of nursing’s developmental direction, and attempts to promote innovation in the clinical arena became apparent. A number of approaches were pursued and new roles in nursing, such as the nurse specialist and the nurse practitioner, emerged. Changes in nursing education and training, and the pursuit of evidence-based approaches to practice, are the present-day continuance of nursing’s attempt to develop and reshape the reality of nursing. Nursing science—the systematically developed knowledge of a discipline—is advancing rapidly internationally as nurses increasingly engage in theorising and in conducting research. Nursing science refers to the body of knowledge that is used to support nursing practice and nursing models are constructions of theories and concepts designed to explain what nursing is.

As a discipline, nursing’s domain is delineated by the bounds of legitimate practice. Because nursing is so diverse, practice is broad and varied and the focus of nursing science is best defined in broad terms as:

• the process of nursing (that which occurs between the nurse and the nursed)

• the subject of nursing (the nursed)

• the context of nursing (the physical, cultural and socio-political environment in which nursing takes place) (Pearson, 2000).

Modern nursing is an art and a science that has as its central focus the generation, preservation, dissemination and application of nursing knowledge (nursing science)—and nursing’s knowledge interests are the process, subject and contexts of nursing. Nurses also, of course, apply knowledge from a number of related basic social sciences, physical sciences and bio-behavioural sciences.

Expertise in nursing is developed through the acquisition of nursing knowledge and clinical experience and the interaction of these understandings. The expertise required to interpret clinical situations and make clinical judgments is the essence of nursing care, and the basis for the advancement of nursing practice and the development of nursing science (Benner and Tanner, 1987). Nurses learn from experience. They also learn and grow professionally by becoming familiar with nursing theory and finding ways to apply theory in their practice. Well-developed theories can form the basis for the nurse’s approach to client care. The nurse must use critical thinking skills to select the appropriate theoretical base to support clinical judgments about the care needed for clients based on knowledge, experience, attitudes and standards of care (Alfaro-LeFevre, 1995). Clinical judgment involves conscious reasoning and intuitive responses based on the nursing assessment (Standing, 2008; Tanner, 1993).

Theory

Pearson and others (2005a) describe theories as proposals that give a reasonable explanation to an event; ideas about how or why something happens. A theory is therefore a set of concepts, definitions, relationships and assumptions or propositions that project a purposive, systematic view of phenomena by designing specific interrelationships among concepts for the purposes of describing, explaining, predicting and/or prescribing (Stevenson, 2005). A nursing theory is a conceptualisation of some aspect of nursing communicated for the purpose of describing, explaining, predicting and/or prescribing nursing (Pearson and others, 2005a). For example, Orem’s (1991) self-care deficit theory can be used to explain the factors within clients’ living situations that support or interfere with their self-care ability. Theory provides nurses with a perspective for viewing client situations, a way of organising data and a method of analysing and interpreting information. Theory allows the nurse to plan and implement care purposefully and proactively (Raudonis and Acton, 1997). The application of nursing theory in practice depends on the nurse’s knowledge of nursing models and how these models relate to one another (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998).

Why nursing theory? Why is there a need for theory as a basis for practice? What is the difference between a model and a theory? These are questions frequently asked by nursing students and clinicians. Meleis (2007) notes that theoretical thinking is integral to all roles of the discipline—the clinician, the educator, the researcher, the administrator and the consultant. Theory is the goal of all scientific work; theorising is a central process in all scientific endeavours; and theoretical thinking is essential to all professional undertakings (Meleis, 2007).

Models and theories have in common the use of definitions and statements of interrelationships, but models attempt to represent or model in words the way something works explicitly whereas theory is more detailed, elaborate and abstract (Meleis, 2007).

The development of nursing science, of conceptual models and of theory is a scholarly activity. The scholarliness of theory is not limited to nursing academics, as nurses in clinical settings continually reflect on their own experiences of nursing clients. As a result, clinicians generate theoretical premises within their day-to-day work and apply them as part of the complexity of care delivery.

Nursing is a learned profession, a science and an art (Mitchell, 2003; Rogers, 1990). Nurses need a theoretical base to exemplify the science and art of the profession when they promote health and wellness for their clients, whether the client is an individual, a family or a community.

Components of a theory

Theories provide a foundation of knowledge for the direction and delivery of nursing care. For example, in Betty Neuman’s systems model (Neuman and Young, 1972), the goal of nursing is to assist individuals, families and groups to attain and maintain maximum levels of total wellness by purposeful interventions. The Neuman systems model focuses on nursing care for the client as a whole, encompassing all aspects of the client’s life.

Concept

A theory also consists of interrelated concepts. Concepts are mental formulations of an object or event that come from individual perceptual experience (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998; Torres, 1986). A concept is an idea, a mental image. Concepts help to describe or label phenomena (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998). Again using the Neuman systems model as an example, there are concepts that affect the client system. Some of these concepts are physiological, psychological, sociocultural, environmental, health and wellness, prevention, stressors and defence mechanisms (Meleis, 2007).

Definition

The definitions included within the description of a theory convey the general meaning of the concepts in a manner that fits the theory. These definitions also describe the activity necessary to measure the constructs, relationships or variables within a theory (Chinn and Kramer, 1995; Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998). For example, the Neuman systems model defines clients as people who are anticipating stress or who are dealing with stress. Nurses focus their care on responses that could be labelled ‘stressful’, and these responses are within the domain of nursing (Meleis, 2007).

Assumptions

Assumptions are statements that describe concepts or connect two concepts that are factual and are accepted as truths. Assumptions are the taken-for-granted statements that determine the nature of the concepts, definitions, purpose, relationships and structure of the theory (Chinn and Kramer, 1995; Meleis, 2007). The assumptions in the Neuman systems model are that:

• the relationships between the concepts influence a client’s protective mechanisms and determine a client’s response

• clients have a normal range of responses

• stressors attack flexible lines of defence followed by the normal lines of defence

• nurses’ actions focus on primary, secondary and tertiary prevention.

Phenomena

Nursing theories focus on the phenomena of nursing and nursing care. Phenomena are aspects of reality that can be consciously sensed or experienced (Meleis, 2007). Within a specific discipline, phenomena reflect the domain or territory of the discipline. In nursing, phenomena reflect the domain of nursing practice. In the Neuman systems model, phenomena include all client responses, environmental factors and nursing actions.

Types of theories

The general purpose of a theory is important because it specifies the context and situation in which the theory applies (Chinn and Kramer, 1995). Theories have different purposes and may be classified by levels of abstraction (grand theories versus mid-range theories) or the goals of the theory (descriptive or prescriptive). Theories may describe, predict or prescribe activities for the phenomena of interest.

In Australia and the United Kingdom it is now well accepted that theories are developed at various levels of formality. Pearson and others (2005a) describe personal, local, grand and epistemological theories and meta-theory. Personal theory is unique to the individual and is shaped by the experiences, assumptions and explanations of that individual. Local theory applies to a particular setting or group, such as a hospital ward, primary school or community health centre. Grand theories, which are discussed in more depth in the next section, are concerned with explaining particular phenomena within an activity or field of study. Epistemological theory is concerned with how we know or perceive and investigate the world and what we believe to be legitimate sources of knowledge. Finally, meta-theory defines and classifies theory. Thus, theory surrounds human activity and guides us in our decision making and judgment.

Grand theories

Grand theories are broad in scope and complex (Chinn and Kramer, 1995). These theories require further specification through research before they can be fully tested. A grand theory is not intended to provide guidance for specific nursing interventions, but to provide the structural framework for broad, abstract ideas (Fawcett, 1995). Grand theories contain cumulative concepts that incorporate smaller range theories. An example of a grand theory is Parse’s (1989, 1990) theory of human becoming. In this theory the person is unitary—an indivisible being who interrelates with the environment while co-creating health.

Middle-range theories

Middle-range theories are more limited in scope, and less abstract. These theories cover specific phenomena or concepts and reflect nursing practice (Meleis, 2007). Middle-range theories may consider specific nursing phenomena, e.g. uncertainty, social support and incontinence. For example, Mishel’s middle-range theory of uncertainty in illness (Mishel, 1988, 1990) focuses on client experiences while living with continual uncertainty. The nurse helps the client appraise and adapt to the uncertainty and respond to the illness.

Descriptive theories

Descriptive theories are the first level of theory development. They delineate phenomena, speculate on why phenomena occur, and describe the consequences of phenomena. They have the ability to explain, relate and in some situations predict nursing phenomena (Meleis, 2007). Examples of these theories are those that describe the life processes of a client, such as the developmental theories discussed in Chapter 19. Descriptive nursing theories do not direct specific nursing activities in specific clinical situations, but they have the potential for guiding future nursing research to refine the theory.

Prescriptive theories

Prescriptive theories discuss nursing therapeutics and the consequences of interventions. These types of theories predict the consequence of a specific nursing intervention. In nursing, a prescriptive theory should designate the prescription (i.e. nursing interventions), the conditions under which the prescription should occur, and the consequences (Meleis, 2007). Prescriptive theories are action-oriented, and test the validity and predictability of a nursing intervention. These theories guide nursing research in developing specific nursing interventions.

Nursing models

Components of nursing models

Within any scientific discipline there are specific components of the domain. A domain is the perspective and territory of the discipline and contains the subject, central concepts, values and beliefs, phenomena of interest and the central problems of the discipline. Components of a discipline’s domain are described in a paradigm. A paradigm is a term used to denote the links to science, philosophy and theory accepted by a discipline (Pearson and others, 2005a).

Nursing’s paradigm directs the activity of the nursing profession, including knowledge, philosophy, theory, educational experience, practice orientation, research methodology and literature identified with the profession (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998; Meleis, 2007). Nursing identified its domain in a paradigm that includes four links of interest: the person, health, environment/situation and nursing.

Person refers to the recipient of care, including individual clients, families and the community. The person is central to the care being provided. Because the person’s needs are multidimensional, it is important that nursing provides care individualised to the client’s needs.

Health is defined in different ways by the client, the clinical setting and the healthcare profession, and is the goal of nursing care. The World Health Organization (1987) in the Ottawa Charter defines health as a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. This definition has been questioned and modified by different organisations and groups, as it is felt to be too idealistic and its breadth may suggest that few people are seen as healthy. Most national nursing organisations see health as a dynamic and continuously changing state that relates to feelings of wellbeing within a given setting. The nurse is challenged to provide care based on the client’s individualised level of health and healthcare needs at the time of care delivery.

Environment/situation includes all possible conditions affecting the client and the setting in which healthcare needs occur. For example, a client’s level of health and healthcare needs can be influenced by factors in the home, school, workplace or community settings. An adolescent girl with type 1 diabetes mellitus may need to adapt her care regimen to physical activities of school, to the demands of a part-time job and to the timing of social events. There is continuous interaction between the client and the environment. This interaction can have positive and negative effects on the person’s level of health and healthcare needs.

Nursing is the diagnoses and treatment of human responses to actual or potential health problems (Gordon, 2007). For example, a nurse does not diagnose the client’s heart condition, but instead develops nursing diagnoses of fatigue, change in body image and altered coping. From these nursing diagnoses, the nurse creates an individualised plan of care. Nurses use critical thinking skills and integrate knowledge, experience, attitudes and standards into the individualised plan of care for each client.

Historical perspective

Historically, nursing theories were studied in an isolated academic environment independent of nursing practice and, as a result, many nurses argued that theories were not relevant to what occurs in clinical practice. There is, however, a contemporary move to link practice and academic scholarship through seeking to establish an evidence base for practice. The evidence-based nursing movement has developed rapidly in Australia and the United Kingdom. The Center for Evidence Based Nursing in New York and the United Kingdom and the Joanna Briggs Institute International (with headquarters in Adelaide and almost 70 centres across the world) are examples of research and development units that work to generate summaries of the best available evidence on given topics to help nurses make informed decisions in planning and delivering care. Nursing is a relatively recent recruit to the evidence-based movement. Pearson and others (2005b, 2007) offer a concise appraisal of the benefits of evidence-based nursing and some of the directions in which it is headed. For nursing to grow as a profession, knowledge is needed to predict with confidence the types of nursing interventions that will improve client outcomes. Nurses now and in the future need to have a theoretical understanding of care on which to base their practice.

As nursing continues to evolve, nurses will continue to theorise about the nature of nursing practice, the principles on which practice is based and the proper goals and functions of nursing. Theoretical nursing models have been used to identify the domain and goals of nursing practice, provide knowledge to improve practice, and guide research. Nursing theories were developed to provide the nurse with goals for assessment, nursing diagnoses, care planning and interventions—common ground for communication and professional autonomy and accountability. They have also been used to guide directions for nursing research, practice, education and administration (Chinn and Kramer, 1999; Meleis, 2007) (see Box 3-1).

BOX 3-1 GOALS OF THEORETICAL NURSING MODELS

• Identify domain and goals of nursing.

• Provide knowledge to improve nursing administration, practice, education and research.

• Guide research to establish empirical knowledge base for nursing.

• Identify area to be studied.

• Identify research techniques and tools that will be used to validate nursing interventions.

• Identify nature of contribution that research will make to advancement of knowledge.

• Formulate legislation governing nursing practice, research and education.

• Formulate regulations interpreting nurse practice acts so that nurses and others better understand laws.

• Develop curriculum plans for nursing education.

• Establish criteria for measuring quality of nursing care, education and research.

• Guide development of nursing care delivery system.

• Provide systematic structure and rationale for nursing activities.

An historical review demonstrates that nursing has developed a growing body of knowledge (see Table 3-1). Nursing concepts and theories have evolved since the time of Florence Nightingale who, in establishing the discipline of nursing, spoke with firm conviction about the nature of nursing as a profession that required knowledge distinct from medical knowledge (Nightingale, 1860; Schuyler, 1992). The overall goal of this knowledge has been to explain the practice of nursing as different and distinct from the practice of medicine, psychology or social work (Chinn and Kramer, 1995; Fawcett, 1992).

TABLE 3-1 CHRONOLOGY OF CONCEPTUAL MODELS IN NURSING (1952–1989)

| YEAR OF FIRST MAJOR PUBLICATION | THEORIST | KEY EMPHASIS |

|---|---|---|

| 1952 | Hildegard E Peplau | Interpersonal process is a maturing force for personality |

| 1960 | Patient’s problems determine nursing care | |

| 1961 | Ida Jean Orlando | Interpersonal process alleviates distress |

| 1964 | Ernestine Wiedenbach | Helping process meets needs through art of individualising care |

| 1966 | Lydia E Hall | Nursing care is person-directed towards self-love |

| 1966 | Joyce Travelbee | Meaning in illness determines how people respond |

| 1967 | Myra E Levine | Holism is maintained by conserving integrity |

| 1970 | Martha E Rogers | Person-environment are energy fields that evolve negentropically |

| 1971 | Dorothea E Orem | Self-care maintains wholeness |

| 1971 | Imogene M King | Transactions provide a frame of reference towards goal setting |

| 1974 | Sr Callista Roy | Stimuli disrupt an adaptive system |

| 1976 | Nursing is an existential experience of nurturing | |

| 1978 | Madeleine M Leininger | Caring is universal and varies transculturally |

| 1979 | Jean Watson | Caring is moral ideal: mind–body–soul engagement with another |

| 1979 | Margaret A Newman | Disease is a clue to pre-existing life patterns |

| 1980 | Dorothy E Johnson | Subsystems exist in dynamic stability |

| 1981 | Rosemarie Rizzo Parse | Indivisible beings and environment co-create health |

| 1989 | Patricia Benner and Judith Wrubel | Caring is central to the essence of nursing. It sets up what matters, enabling connection and concern. It creates possibility for mutual helpfulness |

From Chinn PL, Kramer ML 2004 Integrated knowledge development in nursing, ed 6. St Louis, Mosby.

A significant milestone influencing the development of nursing concepts and theory was the establishment of the peer-reviewed journal Nursing Research in 1952. This journal reports on the scientific investigations being conducted by nurses and other professionals. The journal has encouraged scientific productivity and provides the framework for inquiry into theory-based nursing (Meleis, 2007). There is now an enormous number of research-based journals published in most developed countries. These include the Journal of Advanced Nursing, Journal of Clinical Nursing, Nursing Inquiry, NT Research, International Journal of Nursing Studies, International Journal of Nursing Practice, Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing and the Collegian.

In the mid-1950s, nursing leaders in the United States began to formulate theoretical views of nursing and concerns about subjects to include or exclude from nursing curricula. Columbia University Teachers College offered master’s and doctoral programs in nursing education and administration (Meleis, 2007). Several prominent nurse theorists graduated from this institution, including Peplau, Henderson, Hall, Abdellah, King, Wiedenbach and Rogers.

During the 1960s, Yale University School of Nursing explored nursing theory even further. Theory development appeared to be a major preoccupation with nursing academics from the mid-1960s to 1970. A series of symposia, sponsored by Case Western Reserve University, was held to assist in the development of nursing theory. During the mid-1970s the National League for Nursing (NLN), the accrediting institution for nursing education programs, made theory-based curricula a requirement for accreditation. Schools of nursing were encouraged to use a conceptual framework in developing and implementing their curricula (Meleis, 1985, 2007). Similar developments have occurred in other countries. In Australia, theory-based curricula were introduced into nursing schools in the early 1970s. However, the search for grand theories and models which seek to explain nursing as a whole has receded in the last two decades and Australia and New Zealand have been large contributors to the international literature, not so much on the totality of nursing but rather on the phenomena of concern to nursing and on the complexity and ‘messiness’ of nursing practice. This more practice-based focus now occupies much of nursing’s contemporary theory development (Chiarella, 2002; Lawler, 1991; Parker, 1997; Taylor, 1994).

The Australian nurse academic Jocelyn Lawler (1997:47) puts this concern well:

Relationship of theory to the nursing process and client needs

The nursing process, a tool for nursing practice, was introduced first by Orlando (1961) and is a framework for contemporary nursing practice. The nursing process is the procedure for organising nursing care in which the first step, assessment, initiates the act of nursing (Pearson and others 2005a). The goals of the nursing process are noted in the theoretical work by Abdellah, Henderson, Orem, Orlando, Travelbee and Wiedenbach (Meleis, 2007). Together they provide nursing with a perspective on assessment, diagnosis, planning, implementation and evaluation (Abdellah and others, 1960; Henderson, 1966). They create a process of defining and attaining goals and emphasise clients’ perceptions of their health status (Meleis, 2007).

The nursing process offers a systematic approach to nursing practice and enhances research opportunities. The process is adaptable to different clients and different care settings. In addition, the nursing process is compatible with many other systems in the healthcare delivery system, e.g. computer-generated care plans, patient information systems and patient acuity (i.e. dependency) systems (Barnum, 1994).

The nursing process is central to the domain of nursing (Meleis, 2007); however, the nursing process is not a theory. It provides a process for the delivery of nursing care, not the knowledge component of the discipline. There are, however, attempts to build a comprehensive theory from the process. There are attempts to use the nursing process in conjunction with other theories that lack a process element, i.e. to organise nursing diagnoses and interventions as complementary pieces (Barnum, 1994). Nurse theorists, however, are divided as to whether the nursing process model is compatible with current and emerging theories (Meleis, 2007).

The nursing process is a particularly helpful learning tool and is therefore of significance to students and novice practitioners of nursing. It is arguable, however, that its linear nature does not enable the complexity of practice to be captured for the advanced or expert nurse (Benner, 1984).

Interdisciplinary theories

To practise in today’s healthcare systems, nurses need a strong scientific knowledge base from nursing and other disciplines, such as the physical, social and behavioural sciences. Knowledge areas from these other disciplines have relevant theories that explain phenomena. An interdisciplinary theory explains a purposive and systematic view of phenomena specific to the discipline of inquiry, such as Freud’s psychoanalysis theory in the discipline of psychology.

Systems theory

A system is made up of separate components. The parts rely on one another, are interrelated, share a common purpose and together form a whole. The system has a specific purpose or goal and uses a process to achieve that goal. The content is the product and information obtained from the system.

Input is the information that enters the system. Output is the end-product of a system. Feedback is the process through which the output is returned to the system. Systems can be either open or closed. An open system interacts with its environment. There is an exchange of information between the system and the environment. Factors that change the environment can also have an impact on the system. A closed system is one that does not interact with the environment. An example of a closed system is a chemical reaction occurring in an isolated apparatus.

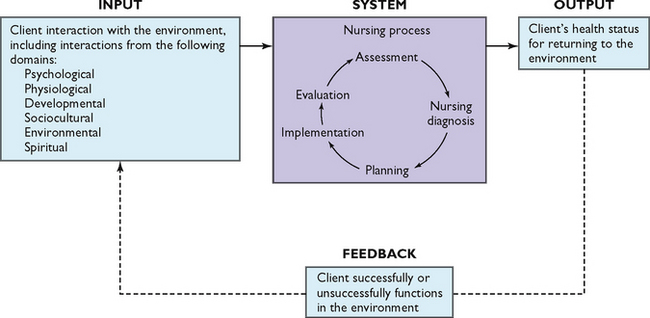

One example of a system is the nursing process (Figure 3-1). The purpose of the nursing process is to provide systematic and individualised client care. The nursing process is an open system because it interacts with its environment, continually changing as the client’s nursing needs change. Input to the system comes from the client’s assessment data (e.g. how the client interacts with the environment, thus creating healthcare needs) and from the nurse. The output, i.e. the client’s response to nursing interventions (e.g. client’s status for returning to the environment), is returned as feedback to the nursing process system and the client successfully or unsuccessfully functions in the environment.

Nursing theories may have a systems model as the theoretical base; for example, Betty Neuman (1972, 1995) defines a total-person model of holism and an open-system approach. As an open system the person interacts with the environment. The environment is both external and internal and the person interacts with stressors from the environment, which affect the system.

Basic human needs

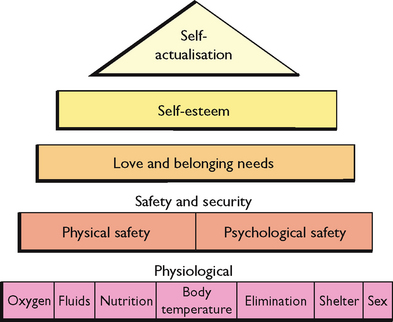

Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs is an interdisciplinary theory useful for designating priorities of care. The hierarchy of human needs arranges the basic needs in five levels of priority (Figure 3-2). The most basic, or first, level includes physiological needs such as air, water and food. The second level includes safety and security needs, which involve physical and psychological security. The third level contains love and belonging needs, including friendship, social relationships and sexual love. The fourth level encompasses esteem and self-esteem needs, which involve self-confidence, usefulness, achievement and self-worth. The final level is the need for self-actualisation, the state of fully achieving potential and having the ability to solve problems and cope realistically with life’s situations. Basic physiological and safety needs are usually first priority; however, the nurse may encounter situations in which there are no emergent physical or safety needs but in which high priority must be given to the psychological, sociocultural, developmental or spiritual needs of the client.

FIGURE 3-2 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Redrawn from Maslow AH 1970 Motivation and personality, ed 2. New York, Harper & Row. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons.

Clients entering the healthcare system generally have unmet needs. For example, a person brought to an emergency room experiencing acute pneumonia has an unmet need for oxygen, the most basic physiological need. An older woman in a high-crime area may be concerned about physical safety and, while hospitalised, may have a need for psychological security because of fear that her home will be burgled. A widowed homemaker whose children have moved away may feel that she does not belong or is not loved. Nurses in all practice settings strive to help clients and their families meet these needs.

The hierarchy of needs is a useful way for nurses to plan individualised care for a client. One need may take priority over another (such as restoration of an adequate airway before the nurse educates the client in adjusting to an emotional conflict). The nurse uses priorities to determine nursing diagnoses, develop goals and expected outcomes and select nursing interventions.

Health and wellness models

Health and wellness models are designed to help healthcare professionals understand the relationships between these two concepts and the client’s attitudes towards health and health practices. Knowledge of these models assists nurses in understanding and predicting the client’s health behaviours, including use of healthcare services and adherence to recommended therapies.

Stress and adaptation

Stress and adaptation are universal and dynamic. Everyone experiences stress and attempts to adapt to the stressors. Stressors and stress responses are physiological and behavioural. As a result, the models that explain the stress response are usually bio-behavioural and provide the framework for care of clients experiencing stress. Chapter 42 explains the more prominent theories and demonstrates how these models are used in nursing practice.

Developmental theories

Human growth and development is an orderly predictive process that begins with conception and continues until death. There are a variety of well-tested theoretical models that describe and predict behaviour and development at various phases of the life continuum. Chapter 19 details these theories and Chapters 20–22 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 demonstrate changes in growth and development in various age groups.

Psychosocial theories

Nursing is an eclectic discipline that strives to meet the holistic needs of clients in their physiological, psychological, sociocultural, developmental and spiritual domains. There are theoretical models that explain and/or predict client responses in each of these domains. For example, Chapter 17 discusses models for understanding diversity and implementing care to meet the diverse needs of clients. Chapter 18 describes family theory and how to meet the needs of the family when the family is the client or when the family is the caregiver. Chapter 25 discusses several models of grieving and demonstrates how to help clients through loss, death and grief.

Selected nursing theories

Definitions and theories of nursing can help nursing students understand how the roles and actions of nurses fit together in nursing. The following sections describe, in chronological order of theory development, concepts basic to selected nursing theories (Table 3-2).

TABLE 3-2 SUMMARY OF NURSING THEORIES (for references, see end of chapter)

| THEORIST | GOAL OF NURSING | FRAMEWORK FOR PRACTICE |

|---|---|---|

| Nightingale—1860 | To facilitate ‘the body’s reparative processes’ by manipulating client’s environment (Torres, 1986) | Client’s environment is manipulated to include appropriate noise, nutrition, hygiene, light, comfort, socialisation and hope |

| Peplau—1952 | To develop interaction between nurse and client (Peplau, 1952) | Nursing is a significant, therapeutic, interpersonal process (Peplau, 1952). Nurses participate in structuring health care systems to facilitate natural ongoing tendency of humans to develop interpersonal relationships (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998) |

| Henderson—1955 | To work independently with other health care workers (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998), assisting client in gaining independence as quickly as possible (Henderson, 1966); to help client gain lacking strength (Torres, 1986) | Nurses help client to perform Henderson’s 14 basic needs (Henderson, 1966) |

| Abdellah—1960 | To provide service to individuals, families and society; to be kind and caring but also intelligent, competent and technically well prepared to provide this service (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998) | This theory involves Abdellah’s 21 nursing problems (Abdellah and others, 1960) |

| Orlando—1961 | To respond to client’s behaviour in terms of immediate needs; to interact with client to meet immediate needs by identifying client’s behaviour, reaction of nurse, and nursing action to be taken (Chinn and Kramer, 1999; Torres, 1986) | Three elements—client behaviour, nurse reaction and nurse action—comprise nursing situation (Orlando, 1961) |

| Hall—1962 | To provide care and comfort to client during disease process (Torres, 1986) | The client is composed of the following overlapping parts: person (core), pathological state and treatment (cure) and body (care). Nurse is caregiver (Chinn and Kramer, 1999; Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998) |

| Wiedenbach—1964 | To assist individuals in overcoming obstacles that interfere with the ability to meet demands or needs brought about by condition, environment, situation or time (Torres, 1986) | Nursing practice is related to individuals who need help because of behavioural stimulus. Clinical nursing has the following components: philosophy, purpose, practice and art (Chinn and Kramer, 1999) |

| Levine—1966 | To use conversation activities aimed at optimal use of client’s resources | This adaptation model of human as integral whole is based on ‘four conversation principles of nursing’ (Levine, 1973) |

| Johnson—1968 | To reduce stress so that client can move more easily through recovery process | This theory of basic needs focuses on seven categories of behaviour. Individual’s goal is to achieve behavioural balance and steady state by adjustment and adaptation to certain forces (Johnson, 1980; Torres, 1986) |

| Rogers—1970 | To maintain and promote health, prevent illness and care for and rehabilitate ill and disabled client through ‘humanistic science of nursing’ (Rogers, 1970) | ‘Unitary man’ evolves along life process. Client continuously changes and coexists with environment |

| Orem—1971 | To care for and help client attain total self-care | This is self-care deficit theory. Nursing care becomes necessary when client is unable to fulfil biological, psychological, developmental or social needs (Orem, 1991) |

| King—1971 | To use communication to help client re-establish positive adaptation to environment | Nursing process is defined as dynamic interpersonal process between nurse, client and health care system |

| Travelbee—1971 | To assist individual or family in preventing or coping with illness, regaining health, finding meaning in illness or maintaining maximal degree of health (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998) | Interpersonal process is viewed as human-to-human relationship formed during illness and ‘experience of suffering’ |

| Neuman—1972 | To assist individuals, families and groups in attaining and maintaining maximal level of total wellness by purposeful interventions | Stress reduction is goal of systems model of nursing practice (Torres, 1986). Nursing actions are in primary, secondary or tertiary level of prevention |

| Patterson and Zderad—1976 | To respond to human needs and build humanistic nursing science (Chinn and Kramer, 1999; Patterson and Zderad, 1976) | Humanistic nursing requires participants to be aware of their ‘uniqueness’ and ‘commonality’ with others (Chinn and Kramer, 1999) |

| Leininger—1978 | To provide care consistent with nursing’s emerging science and knowledge with caring as central focus (Chinn and Kramer, 1999) | With this transcultural care theory, caring is the central and unifying domain for nursing knowledge and practice |

| Roy—1979 | To identify types of demands placed on client, assess adaptation to demands and help client adapt | This adaptation model is based on the physiological, psychological, sociological and dependence-independence adaptive modes (Roy, 1980) |

| Watson—1979 | To promote health, restore client to health, and prevent illness (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998) | This theory involves philosophy and science of caring; caring is an interpersonal process comprising interventions that result in meeting human needs (Torres, 1986) |

| Parse—1981 | To focus on human being as living unity and individual’s qualitative participation with health experience (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998; Parse, 1990) | The individual continually interacts with environment and participates in maintenance of health (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998). Health is a continual, open process rather than a state of wellbeing or absence of disease (Chinn and Kramer, 1999; Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998; Parse, 1990) |

| Benner and Wrubel—1989 | To focus on client’s need for caring as a means of coping with stressors of illness (Chinn and Kramer, 1999) | Caring is central to the essence of nursing. Caring creates the possibilities for coping and enables possibilities for connecting with and concern for others (Benner and Wrubel, 1989) |

Nightingale

Contemporary authors are returning to the work of Florence Nightingale as a potential theoretical and conceptual model for nursing (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998; Meleis, 2007). Meleis (2007) suggests that Nightingale’s concept of the environment as the focus of nursing care and her warning that nurses need not know all about the disease process are early attempts to differentiate between nursing and medicine.

Nightingale did not view nursing as limited merely to the administration of medications and treatments, but rather as oriented towards providing fresh air, light, warmth, cleanliness, quiet and adequate nutrition (Nightingale, 1860; Torres, 1986). Through observation and data collection, she linked the client’s health status with environmental factors and initiated improved hygiene and sanitary conditions during the Crimean War.

Torres (1986) notes that Nightingale provided basic concepts and propositions that could be supported and used for practice in nursing. Nightingale’s descriptive theory provides nurses with a way to think about nursing with a frame of reference that focuses on clients and the environment (Torres, 1986). Nightingale’s letters and writings direct the nurse to act on behalf of the client. Her principles were visionary and encompass the areas of practice, research and education. Most importantly, her concepts and principles shaped and delineated nursing practice (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998). Nightingale taught and used the nursing process, noting that ‘vital observation [assessment] … is not for the sake of piling up miscellaneous information or curious facts, but for the sake of saving life and increasing health and comfort’.

Peplau’s theory

Hildegard Peplau’s theory (1952) focuses on the individual, nurse and interactive process; the result is the nurse–client relationship (Torres, 1986; Yamashita, 1997). According to this theory, the client is an individual with a felt need, and nursing is an interpersonal and therapeutic process. Nursing’s goal is to educate the client and family and to help the client reach mature personality development (Chinn and Kramer, 1995). The nurse strives to develop a nurse–client relationship in which the nurse serves as a resource person, counsellor and surrogate.

For example, when the client seeks help, the nurse and client first discuss the nature of the problem and the nurse explains the services available. As the nurse–client relationship develops, the nurse and client mutually define the problem and find potential solutions. The client gains from this relationship by using available services to meet needs, and the nurse assists the client in reducing anxiety related to the healthcare problem. Peplau’s theory is unique in that the collaborative nurse–client relationship creates a ‘maturing force’ through which interpersonal effectiveness assists in meeting the client’s needs (Beeber and others, 1990). When the original needs have been resolved, new needs may emerge. The nurse–client interpersonal relationship is characterised by the following overlapping phases: orientation, identification, explanation, and resolution (Chinn and Kramer, 1995).

Peplau’s theory and ideas were developed to provide a design for the practice of psychiatric nursing. Nursing research on anxiety, empathy, behavioural tools and tools to evaluate verbal responses resulted from Peplau’s conceptual model (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998).

Henderson’s theory

Henderson (1966) defines nursing as assisting the individual, sick or well, in the performance of those activities that contribute to health recovery or peaceful death that the individual would perform unaided if he or she had the necessary strength, will or knowledge. The process of nursing strives to do this as rapidly as possible, and the goal is independence.

Henderson organised the theory into 14 basic needs of the whole person and included phenomena from the following domains of the client: physiological, psychological, sociocultural, spiritual and developmental. Together the nurse and client work in unison to meet these needs and attain client-centred goals.

Abdellah’s theory

The nursing theory developed by Faye Abdellah and others (1960) emphasises delivering nursing care for the whole person to meet the physical, emotional, intellectual, social and spiritual needs of the client and family. When using this approach, the nurse needs knowledge and skills in interpersonal relations, psychology, growth and development, communication and sociology, as well as knowledge of the basic sciences and specific nursing skills. The nurse is a problem solver and decision maker. The nurse formulates an individualised view of the client’s needs that may arise in the following four areas:

From these four areas, Abdellah and others (1960) identified 21 specific client needs, which are often referred to as Abdellah’s 21 nursing problems.

Levine’s theory

Myra Levine’s (1973) nursing theory views the client as an integrated being who interacts with and adapts to the environment. Levine believes that nursing intervention is a conservation activity, with conservation of energy as a primary concern (Fawcett, 1992). Health is viewed in terms of the conservation of energy. Levine refers to four conservation principles of nursing as:

1. conservation of client energy

2. conservation of structural integrity

With this approach, nursing care involves conservation activities aimed at the best use of the client’s resources.

Johnson’s theory

Dorothy Johnson’s (1968, 1980) theory of nursing focuses on how the client adapts to illness and how actual or potential stress can affect the ability to adapt. The goal of nursing is to reduce stress so that the client can move more easily through recovery. Johnson describes basic needs in terms of the following categories of behaviour:

• master of oneself and one’s environment according to internalised standards of excellence

• taking in nourishment in socially and culturally acceptable ways

• ridding the body of waste in socially and culturally acceptable ways

According to Johnson, the nurse assesses the client’s needs in these categories of behaviour, called behavioural subsystems. Under normal conditions the client functions effectively in the environment. When stress disrupts normal adaptation, however, behaviour becomes erratic and less purposeful. The nurse identifies this inability to adapt and provides nursing care to resolve problems in meeting the client’s needs.

Rogers’ theory

In her theory, Martha Rogers (1970) considers the individual (unitary human being) as an energy field co-existing within the universe. The individual is in continuous interaction with the environment and is a unified whole, possessing personal integrity and manifesting characteristics that are more than the sum of the parts (Lutjens, 1995; Rogers, 1970). A unitary human being is a ‘four-dimensional energy field identified by pattern and manifesting characteristics that are specific to the whole and which cannot be predicted from the knowledge of parts’ (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998). The four dimensions used in Rogers’ theory—energy fields, openness, pattern and organisation, and dimensionality—are used to derive principles related to human development.

Rogers views nursing primarily as a science and is committed to nursing research and theory development. Nursing therefore incorporates knowledge of the basic sciences and physiology, as well as nursing knowledge.

Orem’s theory

Dorothea Orem (1971) developed a definition of nursing that emphasises the client’s self-care needs. Orem defines self-care as a learned goal-oriented activity directed towards the self in the interest of maintaining life, health, development and wellbeing (Orem, 1991). Orem describes her philosophy of nursing in this way:

Nursing has as a special concern, man’s needs for self-care action and the provision and management of it on a continuous basis in order to sustain life and health, recover from disease or injury and cope with their effects. Self-care is a requirement of every person—man, woman and child. When self-care is not maintained, illness, disease, or death will occur. Nurses sometimes manage and maintain required self-care continually for persons who are totally incapacitated. In other instances, nurses help persons to maintain required self-care by performing some but not all care measures, by supervising others who assist clients, and by instructing and guiding individuals as they gradually move toward self-care.

Thus the goal of Orem’s theory is helping the client perform self-care. According to Orem, nursing care is necessary when the client is unable to fulfil biological, psychological, developmental or social needs. The nurse determines why a client is unable to meet these needs, what must be done to enable the client to meet them and how much self-care the client is able to perform. The goal of nursing is to increase the client’s ability to independently meet these needs (Hartweg and Orem, 1995).

King’s theory

Imogene King’s goal attainment theory (1971, 1981, 1987) focuses on three dynamic interacting systems: personal, interpersonal and social (King, 1997). A personal relationship forms between client and nurse. The nurse–client relationship is the vehicle for the delivery of nursing care, which is a dynamic interpersonal process in which the nurse and client are affected by each other’s behaviour as well as by the healthcare system (King, 1971, 1981). The nurse’s goal is to use communication to assist the client in re-establishing or maintaining a positive adaptation to the environment.

Neuman’s theory

Betty Neuman’s theory (Neuman, 1995) defines a total-person model for nursing incorporating a holistic concept and an open-systems approach (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998). To Neuman, the person is a dynamic composite of physiological, sociocultural, developmental, psychological and spiritual components that function as an open system. As an open system, the person interacts with, adjusts to and is adjusted by the environment, which is viewed as a stressor (Chinn and Kramer, 1995). The internal environment consists of influences within the client (intrapersonal). The external environment is influences outside the client (interpersonal). The created environment is the client’s attempt to create a safe setting, which may be made up of conscious or unconscious mechanisms (Reed, 1995). Each environment provides potential threats from stressors, which disrupt the system. Neuman’s model includes intrapersonal, interpersonal and extrapersonal stressors (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998; Neuman, 1995).

Neuman believes that nursing is concerned with the whole person. The goal of nursing is to assist individuals, families and groups in attaining and maintaining a maximum level of total wellness (Neuman and Young, 1972). The nurse assesses, manages and evaluates client systems. Nursing focuses on the variables affecting the client’s response to the stressor (Chinn and Kramer, 1995). Nursing actions are in the primary, secondary and tertiary levels of prevention. Primary prevention focuses on strengthening a line of defence by identifying actual or potential risk factors associated with stressors. Secondary prevention strengthens internal defences and resources by establishing priorities and treatment plans for identified symptoms, and tertiary prevention focuses on readaptation. The main goals in tertiary prevention are to strengthen resistance to stressors through client education and help prevent a recurrence of the stress response (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998).

Roy’s theory

Sister Callista Roy’s adaptation theory (Roy, 1980, 1984, 1989; Roy and Obloy, 1979) views the client as an adaptive system. According to Roy’s model, the goal of nursing is to help the person adapt to changes in physiological needs, self-concept, role function and interdependent relations during health and illness (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998). The need for nursing care arises when the client cannot adapt to internal and external environmental demands. All individuals must adapt to the following demands:

The nurse determines which demands are causing problems for a client and assesses how well the client is adapting to them. Nursing care is then directed at helping the client adapt. For example, a client who has a significant postoperative blood loss and now has a low haemoglobin count needs nursing interventions designed to help the client adapt to the associated fatigue. The nurse may design interventions to allow sufficient rest.

Watson’s theory

Watson’s philosophy of transpersonal caring (1979, 1985, 1988) defines the outcome of nursing activity regarding the humanistic aspects of life (Marriner-Tomey and Alligood, 1998; Watson, 1979). The action of nursing is directed at understanding the interrelationship of health, illness and human behaviour. Nursing is concerned with promoting and restoring health and preventing illness.

Watson’s model is designed around the caring process, assisting clients to attain or maintain health or to die peacefully. This caring process requires the nurse to be knowledgeable about human behaviour and human responses to actual or potential health problems, individual needs, how to respond to others and strengths and limitations of the client and family, as well as those of the nurse. In addition, the nurse comforts and offers compassion and empathy to clients and their families. Caring represents all of the factors the nurse uses to deliver healthcare to the client (Watson, 1987) (see Research highlight).

Benner and Wrubel’s theory

The primacy of caring is a model proposed by Benner and Wrubel (1989). In this model, caring is central. Caring creates the possibilities for coping, enables possibilities for connecting with and concern for others and allows for the giving and receiving of help (Chinn and Kramer, 1995).

As defined in this theory, caring means that persons, events, projects and things matter to people. Caring itself presents a connection. Caring represents a wide range of involvement, e.g. caring about one’s family, caring about one’s friendships and caring about one’s clients. Benner sees the personal concern as an inherent feature of nursing practice. In caring for one’s clients, nurses help clients recover, noticing those interventions that are successful and can therefore guide future caregiving.

Parse’s theory

The theory of human becoming (Parse, 1987, 1989, 1995) states that clients are open, mutual and in constant interaction with the environment. Health is a process of the individual relating to the environment. Health is a lived experience, which is continually changing. The client redefines health as the interaction evolves with the environment.

Research focus

Many nursing theories have not been subjected to the empirical testing required to establish their impact on nursing care processes and client outcomes. Watson’s caring model can be considered a philosophical and moral/ethical foundation for nursing practice. It offers a framework of caring factors to guide nursing interventions.

Research abstract

A research study was set up to determine the effectiveness of a nurse’s caring relationship—according to Watson’s model—on the blood pressure and the quality of life of clients with hypertension. A pre- and post-design was used in which 52 clients with hypertension who had consented to take part in the study completed questionnaires focusing on their quality of life and demographic details; the participants also had their blood pressure recorded. Nurses who had been trained to use Watson’s caring model then visited the clients and their families once a week for blood pressure measurement over a period of 3 months. At the end of that time, the participants completed the quality-of-life measure and their blood pressures were noted. Significant improvements were found in the participants’ scores for wellbeing, physical symptoms and activity, medical intervention and their level of hypertension.

The nurse helps the client interact with the environment and re-establish health. The person experiences continued growth and development. The nurse assists the client in this growth by sustaining a safe and protective environment. Physiological and psychosocial needs are interrelated and cannot be treated as a separate subsystem of the individual.

Applying the theories

Application of nursing theory in practice depends on nurses having knowledge of the theories as well as an understanding of how the theories relate to one another. Theories are the organising frameworks for the science of nursing and the substantive approaches for nursing care. They provide critical thinking structures to guide clinical reasoning and problem solving, and as such are extremely valuable to students and those beginning their careers in nursing. It is for this reason that a knowledge of this theory development is important for today’s student, even though you will have noticed that most were developed a significant time ago. Do not dismiss what they have to offer just because they may have been developed before you were born, but rather appreciate how they can help you organise your thinking and understand them as the foundational work on which more contemporary work has been built. They are part of our rich intellectual history.