EVALUATION

• Patient will identify whether blood pressure reading is within normal limits for age.

• Patient with vascular insufficiency will describe precautions to take to avoid further circulatory deficiency.

• Patient will demonstrate self-monitoring of blood pressure.

To examine the peripheral vascular system, first assess the adequacy of blood flow to the extremities by measuring arterial pulses and inspecting the condition of the skin and nails. A systematic technique is useful, starting with the carotid arteries in the neck and moving down to the arteries in the upper and lower extremities. The wall of an artery is normally elastic, making it easily palpable. After the artery is depressed, it will spring back to shape when pressure is released. The arterial pulses to be palpated include the temporal, carotid, brachial, radial, femoral, popliteal, posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis. These pulses are palpated for rate, rhythm, strength and symmetry. An inequality may indicate localised obstruction or an abnormally positioned artery.

Each peripheral artery is examined using the distal pads of the second and third fingers. The thumb may help anchor the brachial and femoral artery. Firm pressure is applied without occluding the pulse. When it is difficult to find a pulse, it is helpful to vary pressure and feel all around the pulse site.

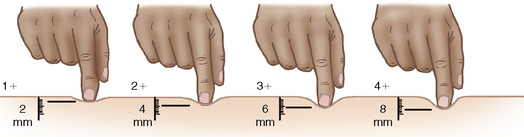

The strength of a pulse is a measurement of the force at which blood is ejected against the arterial wall. Some examiners use a scale rating from 0 to 4 for the strength of a pulse (Seidel and others, 2011):

0. Absent, not palpable

1. Pulse diminished, barely palpable

2. Easily palpable, normal pulse

3. Full pulse, increased

4. Strong, bounding pulse, cannot be obliterated.

CAROTID PULSES

When the left ventricle pumps blood into the aorta, pressure waves transmitted through the arterial system manifest as pulses palpable in arteries close to the skin or lying over bone. The pressure in carotid arteries provides a more accurate reflection of heart function than that in peripheral arteries because of the closeness to the aorta.

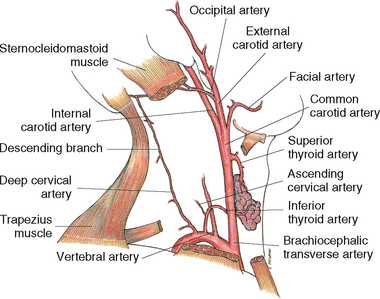

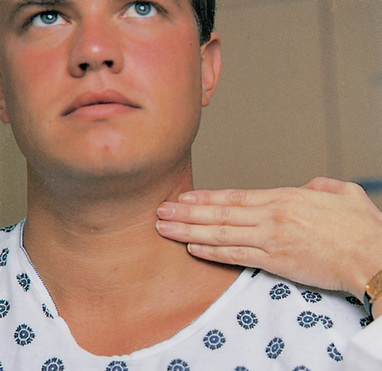

The carotid arteries supply oxygenated blood to the head and neck (Figure 27-24) and are protected by the overlying sternocleidomastoid muscle. To examine the carotid arteries, have the patient sit or lie supine with the head of the bed elevated 30 degrees. One carotid artery is examined at a time (Figure 27-25), as occlusion of both arteries could result in loss of consciousness due to inadequate cerebral circulation. In addition, vigorous palpation or massage is contraindicated because it stimulates the carotid sinus. The carotid sinus, located at the bifurcation of the common carotid arteries in the upper third of the neck, sends impulses along the vagus nerve. Carotid sinus stimulation can cause a reflex drop in heart rate and blood pressure, which causes syncope or circulatory arrest.

The neck is first inspected for obvious pulsation of the artery. The patient turns the head slightly away from the artery being examined. For palpation of the pulse, the patient turns the head slightly towards the side being examined. This manoeuvre relaxes the neck muscles for easier palpation. Slide the tips of your index and middle fingers around the medial edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The normal carotid pulse is localised rather than diffuse. A strong pulse, the carotid has a thrusting quality. No change occurs during inspiration or expiration. Rotation of the neck or a shift from a sitting to a supine position does not change the quality of the carotid artery pulsation. Both carotid arteries should be equal in pulse rate, rhythm and strength, and should be equally elastic. An abnormal artery may be described as hard, inelastic or calcified.

The carotid is one of the most commonly auscultated pulses. Auscultation is especially important for middle-aged adults, older adults or people suspected of having cerebrovascular disease manifested by carotid artery obstruction. When the lumen of a blood vessel is narrowed, its blood flow is disturbed causing a bruit to be heard using the bell of the stethoscope.

OTHER PULSES

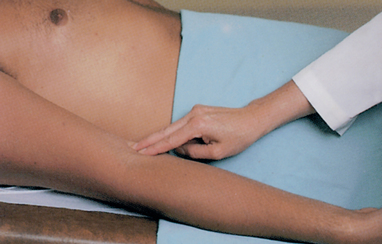

In the upper extremities the main artery is the brachial artery, which channels blood to the radial and ulnar arteries of the forearm and hand. To palpate the brachial pulse, find the groove between the biceps and triceps muscles above the elbow at the antecubital fossa (Figure 27-26). The artery runs along the medial side of the extended arm. Palpate the artery with the fingertips of the first three fingers in the muscle groove. If circulation in this artery becomes blocked, the circulation in the radial or ulnar arteries will be impaired and the hands will not receive adequate blood flow.

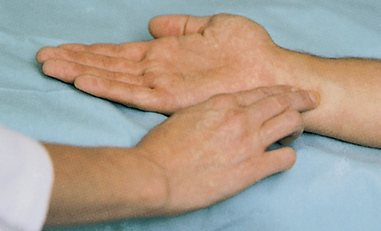

To locate pulses in the arm and hand, have the patient sit or lie down. The radial pulse is found along the radial side of the forearm, at the wrist. In a thin person, a groove is formed lateral to the flexor tendon of the wrist. The radial pulse can be felt with light palpation in the groove (Figure 27-27). The ulnar pulse is on the opposite side of the wrist and tends to feel less prominent than the radial pulse (Figure 27-28).

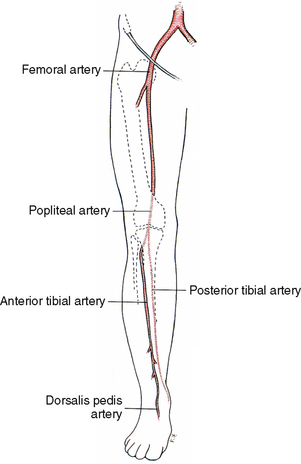

The femoral artery is the main artery in the leg, delivering blood to the popliteal, posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries (Figure 27-29). It is one of the strongest arteries in an infant or small child. An interconnection between the posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis arteries guards against local arterial occlusion.

The femoral pulse is best found during deep palpation with the patient lying down with the inguinal area exposed (Figure 27-30). The femoral artery runs below the inguinal ligament, midway between the symphysis pubis and the anterosuperior iliac spine. Bimanual palpation is effective in obese patients. This technique differs from the previous description of bimanual palpation. Place the fingertips of both hands on opposite sides of the pulse site. A pulsatile sensation can be felt as the fingertips are pushed apart by arterial pulsation.

The popliteal pulse is found behind the knee and is difficult to locate. The patient should slightly flex the knee, with the foot resting on the bed, or assume a prone position with the knee slightly flexed and leg muscles relaxed (Figure 27-31). With the fingers of both hands, palpate deeply into the popliteal fossa, just lateral to the midline.

With the patient’s foot relaxed, locate the dorsalis pedis pulse. The artery runs along the top of the foot in line with the groove between the extensor tendons of the great toe and first toe (Figure 27-32). Locate the pulse by placing the fingertips between the great and first toe and slowly inching up the foot. This pulse may be congenitally absent.

The posterior tibial pulse is found on the inner side of each ankle (Figure 27-33). Place the fingers behind and below the medial malleolus. The artery is easily located with the foot relaxed and slightly extended.

DOPPLER ULTRASOUND STETHOSCOPES

Factors influencing the ability to assess a pulse include obesity, reduction in the heart’s stroke volume, diminished blood volume or arterial obstruction. An ultrasound stethoscope can amplify the sounds of a pulse wave. A thin layer of transmission gel is applied to the patient’s skin at the pulse site or directly onto the transducer tip of the probe. The volume control is then turned to ‘on’ and the tip of the probe placed at an angle of 45–90 degrees on the skin (Figure 27-34). The probe is moved until a pulsating ‘whooshing’ sound is heard, indicating the presence of arterial blood flow.

LOWER EXTREMITIES

During examination of the lower extremities, inspect skin and nail texture; hair distribution on the lower legs, feet and toes; the venous pattern; and scars, pigmentation or ulcers. Normally the lower limbs are symmetrical, warm and pink with presence of hair and intact skin. There is normally no evidence of oedema or tenderness on palpation. The absence of hair growth over the legs may indicate circulatory insufficiency, shaven lower legs, or in males from wearing tight-fitting socks.

PERIPHERAL VEINS

The status of the peripheral veins is assessed by asking the patient to assume sitting and standing positions. Assessment includes inspection and palpation for varicosities, peripheral oedema and phlebitis. Varicosities are superficial veins that become dilated, especially when the legs are in a dependent position. They are common in older adults and people who spend a lot of time standing (e.g. restaurant staff, nurses) because the veins normally fibrose, dilate and stretch. To assess for pitting oedema, use a thumb to press firmly for 5 seconds and then release over the medial malleolus or the shins. A depression left in the skin indicates oedema with the severity characterised by grading 1+ to 4+ (Figure 27-35).

Abnormal findings of the vascular system

Venous congestion causes tissue oedema, indicating an inadequate circulatory flow back to the heart. Dependent oedema of the feet and ankles can be a sign of venous insufficiency and right-sided heart failure. Chronic recurring ulcers of the feet or lower legs are a serious sign of circulatory insufficiency and require medical intervention. If an arterial occlusion is present, the patient has signs resulting from an absence of blood flow (Table 27-19). The six Ps—pain, pallor, pulselessness, polar (cold temperature), paraesthesias and paralysis—characterise an occlusion (Sieggreen, 2006). Signs such as these require urgent medical intervention.

TABLE 27-19 SIGNS OF VENOUS AND ARTERIAL INSUFFICIENCY

| ASSESSMENT CRITERION |

VENOUS |

ARTERIAL |

| Colour |

Normal or cyanotic |

Pale; worsened by elevation of extremity; dusky red when extremity is lowered |

| Temperature |

Normal |

Cool (blood flow blocked to extremity) |

| Pulse |

Normal |

Decreased or absent |

| Oedema |

Often marked |

Absent or mild |

| Skin changes |

Brown pigmentation around ankles |

Thin, shiny skin; decreased hair growth; thickened nails |

Varicosities in the anterior or medial part of the thigh and the posterolateral part of the calf are abnormal. Diminished or unequal carotid pulsations can indicate atherosclerosis or aortic arch disease.

Phlebitis is an inflammation of a vein that occurs commonly after trauma to the vessel wall, infection, prolonged immobilisation and prolonged insertion of intravenous catheters. To assess for phlebitis, inspect the calves for localised redness, tenderness and swelling over vein sites.

Respiratory system

Respiratory assessment

GENERAL INSPECTION

Once again, note general appearance of the patient and observe general responses to activity. The condition of the skin, mucosa, nail beds, lips, nose, throat and tracheal position offers useful data about the patient’s respiratory status. First examine the face, looking at the colour of the skin and mucosa. Inspect the nose for symmetry of nares, presence of discharge and evidence of nasal flaring. Inspect the lips for colour and symmetry. Inspect the nails for shape and colour.

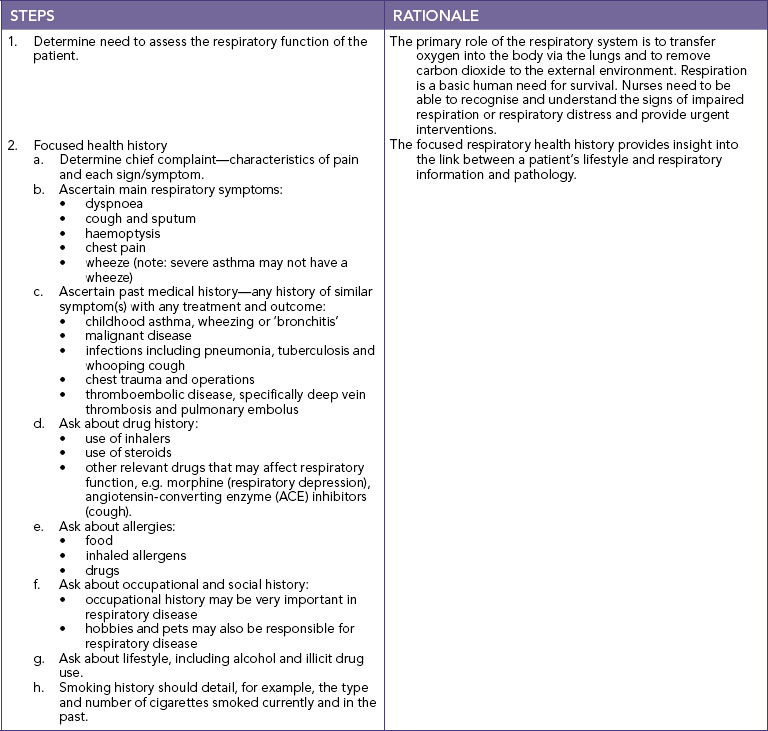

SKILL 27-4 Assessment of the respiratory system

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

Assessment of the respiratory system may be undertaken by enrolled nurses under the guidance of the registered nurse.

• Ensure review of the anatomy and physiology of the respiratory system for risk factors.

• Ensure review of the anatomical landmarks of the chest wall.

• Ensure hand hygiene is performed and personal protective equipment worn when appropriate.

EQUIPMENT

• Stethoscope

• Pen

• Documentation

• Watch (with a second hand)

• Portable pulse oximeter

NOSE, SINUSES AND OROPHARYNX

Inspection and palpation are used to assess the nose and sinuses. The patient sits during the examination. When inspecting the external nose, observe for shape, size, skin, colour and the presence of deformity or inflammation. The nose is normally smooth and symmetrical and the same colour as the face. Note any tenderness, masses or underlying deviations. Nasal structures are usually firm and stable. Air normally passes freely through the nose as a person breathes. To assess patency of the nares, place a finger on the side of the patient’s nose and occlude one naris. The patient is asked to breathe with the mouth closed. The examination is repeated for the other naris.

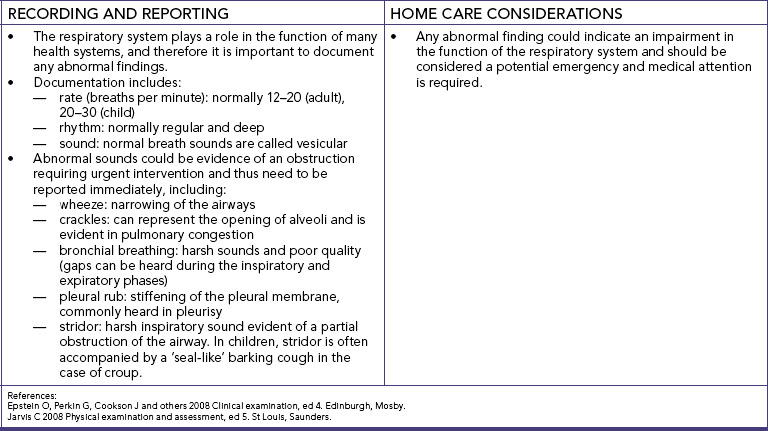

Examination of the sinuses involves palpation. The most effective way to assess for tenderness is by externally palpating the frontal and maxillary facial areas (Figure 27-36). The frontal sinus is palpated by exerting pressure with the thumb up and under the patient’s eye. Gentle, upward pressure elicits tenderness easily if sinus irritation is present and reveals the severity of sinus irritation. Pressure should not be applied to the eyes. Box 27-17 describes teaching guidelines during nose and sinus assessment. The presence of a nasogastric or nasopharyngeal tube entails routine checking for naris skin breakdown (excoriation), characterised by redness and sloughing of the skin. Table 27-20 lists components of the nursing history.

BOX 27-17 CLIENT TEACHING DURING NOSE AND SINUS ASSESSMENT

OBJECTIVES

• Patient will safely use over-the-counter nasal sprays.

• Parents will take proper measures to stop a child’s nosebleed.

• Older adult will take safety precautions with loss of olfaction.

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Caution patient against overuse of over-the-counter nasal sprays, which can lead to ‘rebound’ effect, causing excess nasal congestion.

• Instruct parents on care of a child with nosebleeds: have child sit up and lean forward to avoid aspiration of blood, apply pressure to the anterior nose with the thumb and forefinger as the child breathes through the mouth, and apply ice or a cold cloth to the bridge of the nose if pressure fails to stop bleeding.

• Instruct older adults to install smoke detectors on each floor of their home.

• Instruct older adults to always check dated labels on food to ensure against spoilage.

EVALUATION

• Patient will explain appropriate use of over-the-counter nasal sprays.

• Parents will demonstrate and describe technique for stopping a child’s nosebleed.

TABLE 27-20 NURSING HISTORY FOR NOSE AND SINUS ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

| Have you experienced a knock to your nose? |

Trauma can cause septal deviation and asymmetry of external nose |

| Do you have a history of allergies, nasal discharge, epistaxis (nose bleeds) or postnasal drip? |

History is useful in determining source or nature of nasal and sinus drainage |

| Have you experienced nasal discharge in the past? Can you describe the colour, amount, odour, duration of the discharge? Did you have any associated symptoms (e.g. sneezing, nasal congestion, obstruction or mouth-breathing)? |

Can help to rule out presence of infection, allergy or drug use |

| Have you experienced nosebleeds? Describe the frequency, amount of bleeding, treatment. Was there any difficulty stopping the bleeding? |

Characteristics may reveal trauma, medication use or excessive dryness as causative factors |

| Do you use nasal spray or drops? |

Overuse of over-the-counter nasal preparations can cause physical change in mucosa |

| Do you snore at night? Do you have difficulty breathing? |

Difficulty with breathing or snoring may indicate septal deviation or obstruction |

THORAX AND LUNGS

Examination of the lungs and thorax requires the patient to be in an upright or semi-Fowler’s position and to be undressed to the waist. Good lighting is essential. The trachea is palpated to identify if it is in the midline position.

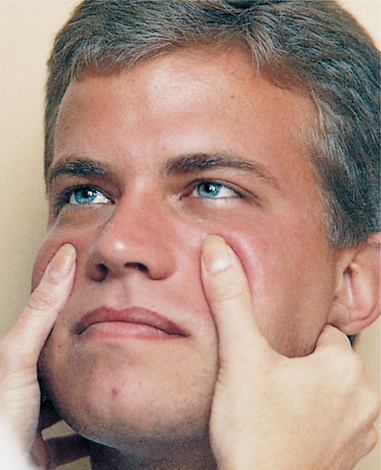

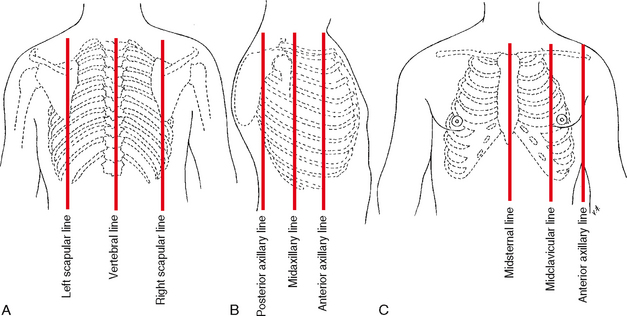

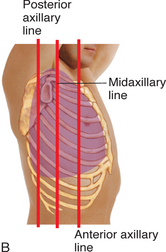

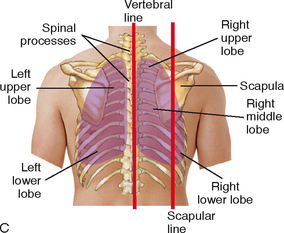

RESPIRATORY ASSESSMENT LANDMARKS

Before assessing the thorax and lungs, identify the landmarks of the chest (Figure 27-37). By knowing the position of underlying organs in relation to the landmarks, you can anticipate where to palpate or auscultate the chest wall. To begin, locate the angle of Louis at the manubriosternal junction. The angle is a visible and palpable angulation of the sternum and is the point at which the second rib articulates with the sternum. Count the ribs and intercostal spaces (between the ribs) from this point. The number of each intercostal space corresponds with that of the rib just above it. The spinous process of the third thoracic vertebra and the fourth, fifth and sixth ribs help to locate the lung’s lobes laterally. The lower lobes project laterally and anteriorly (Figure 27-38). Posteriorly, the tip or inferior margin of the scapula lies approximately at the level of the seventh rib (Figure 27-39). After identifying the seventh rib, count upwards to locate the third thoracic vertebra and align it with the inner borders of the scapula to locate the posterior lobes. During the examination keep a mental image of the location of the lobes of the lung and the position of each rib (Figure 27-40). Locating the position of each rib is critical to identifying the lobe of the lung being assessed.

POSTERIOR THORAX

First inspect the shape and symmetry of the patient’s chest from the back and front. The anteroposterior (AP) diameter is noted. Normally the chest contour is symmetrical, with the AP diameter a third to a half of the transverse, or side-to-side, diameter. Infants have an almost round shape. Ageing and chronic lung disease are characterised by a barrel-shaped chest (AP diameter equals transverse diameter).

Standing at a midline position behind the patient, examine the skin and characteristics of the chest wall; position of the spine (straight without lateral deviation), position of the scapulae (symmetrical and closely attached to the thoracic wall), the slope of the ribs (across and down). Note the movement of the thorax as a whole (regular expansion and relaxation with equality of movement). Assess for abnormalities such as retraction of the intercostal spaces during inspiration, and bulging of the intercostal spaces during expiration.

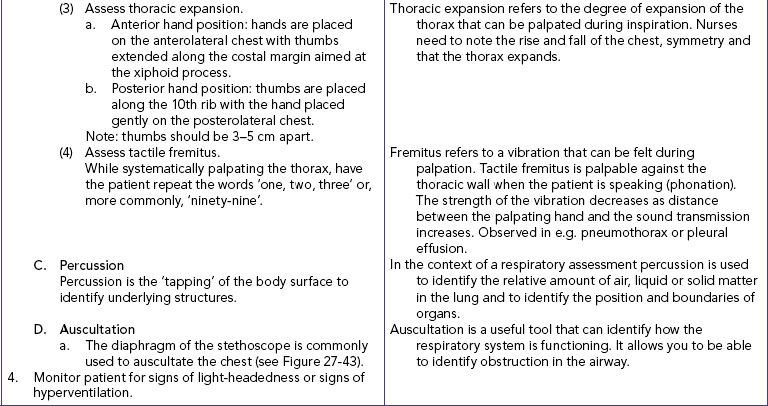

The thoracic muscles and skeleton are palpated for lumps, masses, pulsations and unusual movement. Note pain or tenderness. If a suspicious mass or swollen area is detected, it is lightly palpated for size, shape and the typical qualities of a lesion. Care with palpation is important because fractured rib fragments could be displaced against vital organs. Normally there is no pain or tenderness on palpation, the scapulae are symmetrical and the chest wall is stable.

To measure chest excursion or depth of breathing, stand behind the patient and place the thumbs along the spinal processes at the 10th rib, with the palms lightly contacting the posterolateral surfaces. The thumbs should be about 5 cm apart pointing towards the spine, with fingers pointing laterally (Figure 27-41). The hands are pressed towards the spine so that a small skin fold appears between the thumbs. The patient is instructed to take a deep breath after exhaling. Note the movement of your thumbs. Chest excursion should be symmetrical, separating the thumbs 3–5 cm. Normally breathing is pain-free and does not produce a cough.

Auscultation assesses the movement of air through the tracheobronchial tree and detects mucus or obstructed airways. The diaphragm of the stethoscope is placed firmly on the skin, over the posterior chest wall between the ribs (Figure 27-42). The patient sits upright (if possible), folds the arms in front of the chest and keeps the head bent forwards while taking slow, deep breaths with the mouth slightly open. Listen to an entire inspiration and expiration at each position of the stethoscope. If sounds are faint, as in the obese patient, the patient should be asked to breathe harder and faster. Breath sounds are much louder in children because of the thinness of the chest wall. In children, the bell works best because the chest is small.

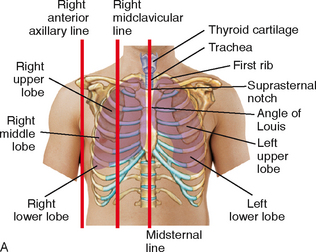

Auscultate for normal breath sounds and abnormal or adventitious sounds. Normal breath sounds differ in character, depending on the area of the lungs being auscultated. Sounds normally heard over the posterior thorax include bronchovesicular and vesicular sounds (Figure 27-43 and Table 27-21). The location and characteristics of the sounds should be noted, as should the absence of breath sounds (found in patients with collapsed or surgically removed lobes).

TABLE 27-21 NORMAL BREATH SOUNDS

| DESCRIPTION |

LOCATION |

ORIGIN |

| VESICULAR |

| Vesicular sounds are soft, breezy and low-pitched. Inspiratory phase is three times longer than expiratory phase |

Best heard over lung’s periphery (except over scapula) |

Created by air moving through smaller airways |

| BRONCHOVESICULAR |

| Bronchovesicular sounds are blowing sounds that are medium-pitched and of medium intensity. Inspiratory phase is equal to expiratory phase |

Best heard posteriorly between scapulae and anteriorly over bronchioles lateral to sternum at first and second intercostal spaces |

Created by air moving through large airways |

| BRONCHIAL |

| Bronchial sounds are loud and high-pitched with hollow quality. Expiration lasts longer than inspiration (2 : 1 ratio) |

Best heard over trachea |

Created by air moving through trachea close to chest wall |

LATERAL THORAX

Extend the assessment of the posterior thorax to the lateral sides of the chest. The patient is asked to raise the arms, which improves access to lateral thoracic structures. Inspection, palpation and auscultation skills are used to methodically examine the lateral thorax (see Figure 27-43). Excursion cannot be assessed laterally. Normally, breath sounds in the lateral thorax are vesicular.

ANTERIOR THORAX

The anterior thorax is inspected for the same features as the posterior thorax. The patient sits or lies down with the head elevated. Observe the accessory muscles of breathing: sternocleidomastoid, trapezius and abdominal muscles. The accessory muscles move little with normal passive breathing. When a patient requires effort to breathe as a result of strenuous exercise or disease (e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), the accessory muscles and abdominal muscles contract. Some patients produce a grunting sound.

Observe the width of the costal angle, which is usually larger than 90 degrees between the two costal margins. Observe the breathing pattern. Normal breathing is quiet and barely audible near the open mouth. Respiratory rate and rhythm are more often assessed anteriorly.

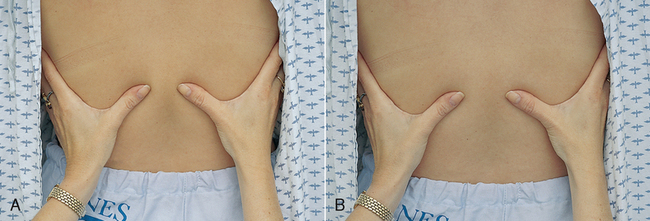

Palpate the anterior thoracic muscles and skeleton for lumps, masses, tenderness or unusual movement. The sternum and xiphoid are relatively inflexible. To measure chest excursion anteriorly, place the hands over each lateral rib cage, with the thumbs approximately 2.5 cm apart and angled along each costal margin (Figure 27-44). The thumbs are pushed towards the midline to create a fold of skin between the thumbs. As the patient inhales deeply, the thumbs should normally separate approximately 2.5–5 cm, with each side expanding equally (Figure 27-44).

Special attention should be paid to the lower lobes, where mucus commonly gathers. Bronchovesicular and vesicular sounds are heard above and below the clavicles and along the lung periphery. An additional normal breath sound, the bronchial sound, can be heard over the trachea. It is loud, high-pitched and hollow-sounding, with expiration lasting longer than inspiration (2 : 1 ratio).

Abnormal findings of the respiratory system

Recent trauma may have caused oedema and discolouration of the skin of the nose. If swelling or deformities exist, gently palpate the ridge and soft tissue of the nose by placing one finger on each side of the nasal arch and moving the fingers from the nasal bridge to the tip.

A sinus infection results in yellowish or greenish discharge from the nose. Habitual use of intranasal cocaine and opioids can cause puffiness and increased vascularity of the nasal mucosa (Brand and others, 2008).

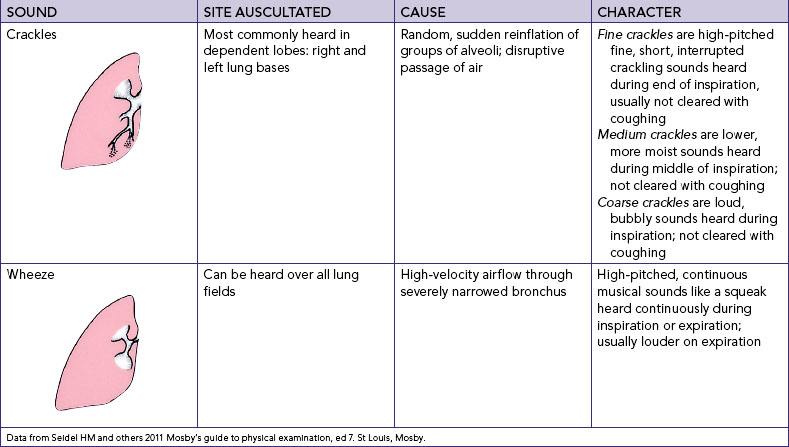

Patients with respiratory diseases, at risk of respiratory complications or with chest pain who cannot fully expand the lungs suffer symptoms such as cough, increased sputum production and dyspnoea. These patients require accurate physical assessment of the thorax and lungs to identify appropriate nursing interventions (Box 27-18). This assessment requires review of the ventilatory and respiratory functions of the lungs and an analysis of the nursing history for lung assessment (see Table 27-22). Reduced chest excursion may be caused by pain, postural deformity or fatigue. In the older adult, chest movement declines because of costal cartilage calcification and respiratory muscle atrophy. Abnormal sounds result from air passing through moisture, mucus or narrowed airways; from alveoli suddenly re-inflating; or from an inflammation between the lung’s pleural linings. Adventitious or added sounds often occur superimposed over normal sounds. The two types of adventitious sounds which beginning nurses should be able to detect are crackles and wheezes. Each sound is caused by a specific entity and is characterised by typical auditory features (Table 27-23).

BOX 27-18 CLIENT TEACHING DURING LUNG ASSESSMENT

OBJECTIVES

• Patient will describe warning signs of lung disease.

• Older adult will receive influenza and pneumonia vaccines annually.

• Patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) will clear airways more effectively and report less shortness of breath.

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Explain risk factors for chronic lung disease and lung cancer, including cigarette smoking, history of smoking for over 20 years, exposure to environmental pollution and radiation exposure from occupational, medical and environmental sources. Residential radon exposure may also increase risk, especially in cigarette smokers. Exposure to sidestream cigarette smoke increases risk for non-smokers.

• Discuss warning signs of lung cancer, such as a persistent cough, sputum streaked with blood, chest pains and recurrent attacks of pneumonia or bronchitis.

• Counsel older adult on benefits of receiving annual influenza and pneumonia vaccinations because of a greater susceptibility to respiratory infection.

• Teach patient with COPD coughing and pursed-lip breathing exercises.

• Persons at risk of tuberculosis who visit clinics or healthcare centres should be referred for skin testing.

EVALUATION

• Patient will describe risk factors for lung disease and cancer.

• Patient will identify any known risks for cancer.

• Patient will name warning signs for cancer.

• Elderly patients and those with chronic lung conditions will have received influenza and pneumonia immunisation.

• Patient will accurately perform breathing and coughing exercises.

TABLE 27-22 NURSING HISTORY FOR LUNG ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

| Do you have a persistent cough (productive or non-productive)? Have you had any chest pain, shortness of breath, shortness of breath at night, difficulty breathing during activity or at rest, poor activity tolerance or recurrent attacks of pneumonia or bronchitis? How much sputum do you cough up? |

Symptoms of respiratory alterations may help nurse localise objective physical findings. (Warning signals for lung cancer are in italic type) |

| Has there been any blood in your sputum? Have you had any unexplained weight loss, fatigue, night sweats or fever? |

These are risk factors for both tuberculosis and HIV infection |

| Are you allergic to pollens, dust or other airborne irritants or to foods, drugs or chemical substances? |

Symptoms such as choking feeling, bronchospasm with respiratory stridor, wheezes on auscultation, and dyspnoea may be caused by allergic response |

| Assess history of tobacco or marijuana use, including type of tobacco, duration and amount (pack years = number of years smoking × number of packets per day), age started and efforts to quit |

Smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer, heart disease and emphysema or bronchitis. Cigarette smoking accounts for a significant percentage of all cancer deaths. The medical practitioner will diagnose the disease |

| Does patient have history of chronic hoarseness? |

Hoarseness may indicate laryngeal disorder or abuse of cocaine or opioids (sniffing) |

| Review family history for cancer, tuberculosis, allergies or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

These conditions place patient at risk of lung disease |

| Review history for known or suspected HIV infection, substance abuse, proximity to a patient with infectious tuberculosis (TB), in a household setting, being homeless, being in prison or working in a hospital |

These are risk factors for tuberculosis (WHO, 2011) |

| Determine whether patient works in environment containing pollutants (e.g. asbestos, arsenic, coal dust) or requiring exposure to radiation. Does patient have exposure to sidestream cigarette smoke? |

These risk factors increase chance of various lung diseases. Knowledge of environmental factors will assist you to focus health teaching |

• CRITICAL THINKING

Part of Mrs Marsaja’s treatment for chest pain requires her to rest in bed. She commences ambulation again, under supervision. You note that she becomes breathless easily with exertion and she tells you she does not feel very well.

What subjective and objective cardiac and respiratory data will you collect in this situation?

Cognitive–perceptual pattern

The neurological system is responsible for many functions, including initiation and coordination of movement, reception and perception of sensory stimuli, organisation of thought processes, control of speech, and storage of memory. The cerebral cortex controls and integrates intellectual and emotional functioning. A close relationship exists between the neurological system and all other body systems. An assessment of cognition and perception will provide you with information about your patient’s capacity to think, sense, perceive and move.

An assessment of cognition and perception includes mental state, sensation and perception, and motor function to detect any changes that may interfere with the person’s ability to meet functional needs. Subjective assessment includes the patient’s description of the adequacy of the special senses (vision, hearing, touch, taste and smell), motor function and any specific symptoms such as visual or auditory hallucinations or illusions, headaches or tremors. Questions are also asked about medication and medical diagnoses (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, epilepsy, liver or renal disease). Physical assessment is focused on examination of the person’s mental state, special-sense organs to detect any dysfunction and ability to move voluntarily, deliberately and in a smooth and coordinated way.

To make good use of your time, it is wise to integrate assessment of cognition and perception with other parts of the physical examination. For example, conscious state and mental and emotional status is observed as the nursing history is collected. Many variables must be considered when deciding the extent of the examination, including a review of nursing history findings (Table 27-24). A patient’s level of consciousness influences the ability to follow directions. A person’s general physical status influences tolerance to assessment. For example, an inability to walk makes a detailed assessment of coordination impossible. The patient’s chief symptom(s) also help determine the need for a thorough neurological assessment. If the patient reports headache or a recent loss of function in an extremity, a complete neurological assessment is required. If a patient demonstrates a change in conscious state, this could indicate a medical emergency requiring prompt intervention.

TABLE 27-24 NURSING HISTORY FOR NEUROLOGICAL ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

Have you experienced seizures/convulsions?

Can you describe the sequence of events (aura, fall to ground, motor activity, loss of consciousness)?

What treatment have you received for the seizures?

|

Seizure activity often originates from central nervous system alteration. Characteristics of seizure help determine its origin |

| Do you have headaches, tremors, dizziness, vertigo, numbness or tingling of body part, visual changes, weakness, pain or changes in speech? |

These symptoms frequently originate from alterations in central nervous system or peripheral nervous system function. Identification of specific patterns may help diagnose pathological condition |

| Discuss with spouse, family members or friends any recent changes in patient’s behaviour (e.g. increased irritability, mood swings, memory loss, change in energy level) |

Behavioural changes may result from intracranial pathological states |

| What medications are you taking? Are you taking any non-prescription drugs? |

Analgesics, antipsychotics, antidepressants or nervous system stimulants can alter level of consciousness or cause behavioural changes |

| Assess patient’s use of alcohol, sedative-hypnotics or recreational drugs |

Abuse can cause tremors, ataxia and changes in peripheral nerve function |

| If an older patient displays sudden acute confusion (delirium), review history for drug toxicity (anticholinergics, diuretics, digoxin, cimetidine, sedatives, antihypertensives, antiarrhythmics), serious infections, metabolic disturbances, heart failure and severe anaemia |

One of the most common mental disorders in older persons.

Condition is always potentially reversible

|

| Review past history for head or spinal cord injury, hypertension or psychiatric disorders |

Factors may cause neurological symptoms or behavioural changes to develop, focusing assessment on possible cause |

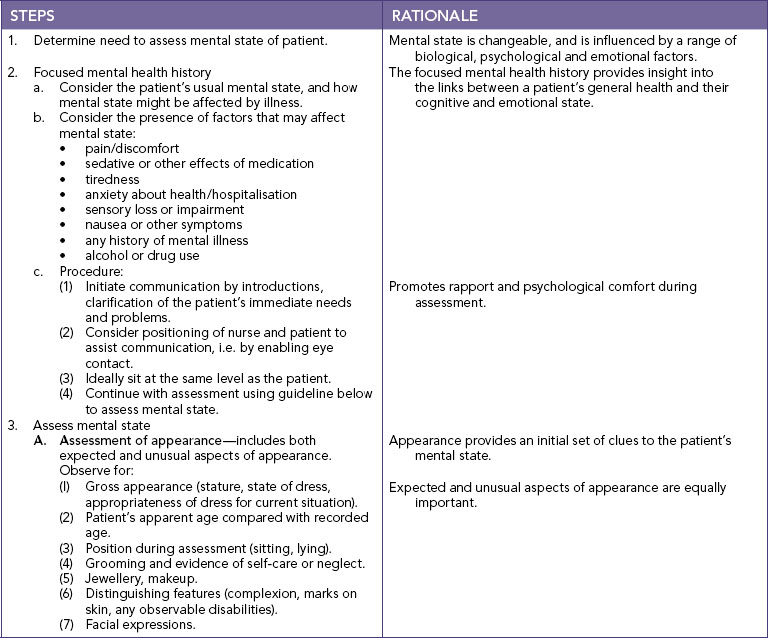

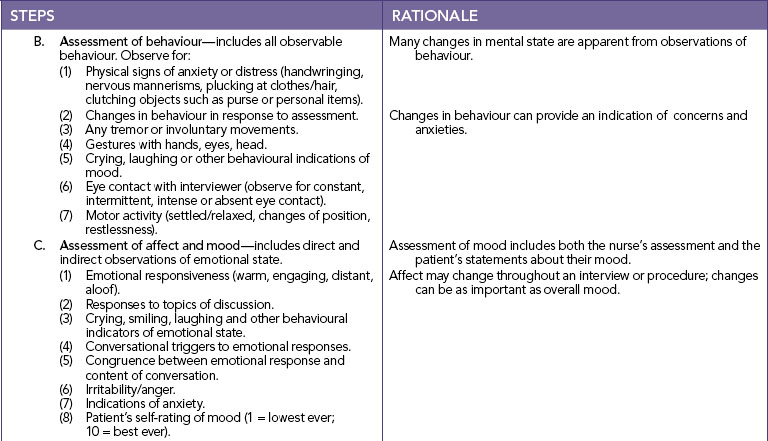

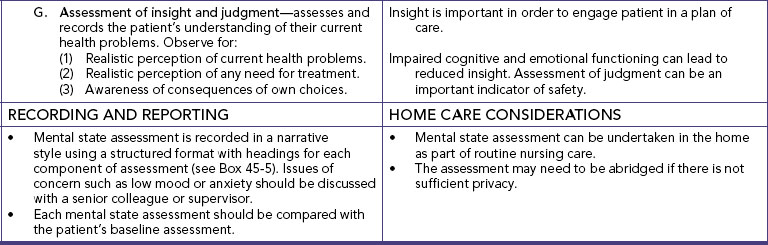

Mental and emotional status

To ensure an objective cognitive assessment, find out about the patient’s cultural and educational background, values, beliefs and previous experiences. Such factors influence the patient’s response to questions. A great deal can be learned about mental capacities and emotional state by simply interacting with the patient. Throughout your nursing care activities you will be gathering information about the way your patient behaves and thinks, and the appropriateness of emotions and ideas. Assessment of mental and emotional status includes collecting information to determine the ability to think, understand and interact with the environment. A mental status assessment is usually divided into four main areas: appearance, behaviour, cognition and thought processes. In children the mental status assessment covers behavioural, cognitive and psychosocial development and how the child is coping with their environment.

Ask questions about the patient’s educational level, their perception of memory, ability to read and write and ability to learn. Ask whether there is a history of anxiety, depression or changes in mood. When assessing a child’s mental and emotional status, it is important to ask the parent(s) about the health of the mother in pregnancy, the process of birth and achievement of developmental milestones. It is also important to hear the parent’s perception of the child’s behaviour. An alteration in mental or emotional status may reflect a disturbance in cerebral functioning. Primary brain disorders, medication and metabolic changes are examples of factors that may change cerebral function.

Behaviour and appearance

Behaviour, moods, hygiene, grooming and choice of dress and level of consciousness reveal pertinent information about mental status. It is important to note mannerisms and actions during the entire physical assessment, including non-verbal and verbal behaviour. Does the patient respond appropriately to directions? Does the patient’s mood vary with no apparent cause? Does the patient show concern about appearance? Is the patient’s hair clean and neatly groomed, and are the nails trim and clean? The patient should behave in a manner expressing concern and interest in the examination. The patient’s facial appearance and mood should be appropriate to the situation. The patient should make eye contact with you and express appropriate feelings that correspond to the situation. Choice and fit of clothing may reflect socioeconomic background or personal taste rather than deficiency in self-concept or self-care, however. Avoid making hasty judgments and consider the appropriateness of clothing for the weather. Older adults may neglect their appearance because of a lack of energy or finances, or physical incapacity or reduced vision.

SKILL 27-5 Mental state assessment

Mental state assessment is a key nursing skill and provides a structured set of observations about the patient’s cognitive and emotional state at a specific point in time.

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

The mental state assessment can be conducted without supervision. Most aspects of the mental state assessment can be carried out as part of routine nursing care, i.e. they can be integrated into other nursing procedures.

Before proceeding:

• review the categories of mental state assessment, and communication skills

• revise the structured format for mental state assessment (BATOMI) (see Box 44-4)

EQUIPMENT

• Mental health assessment uses communication skills and therapeutic use of self

• Consider privacy and appropriateness of setting

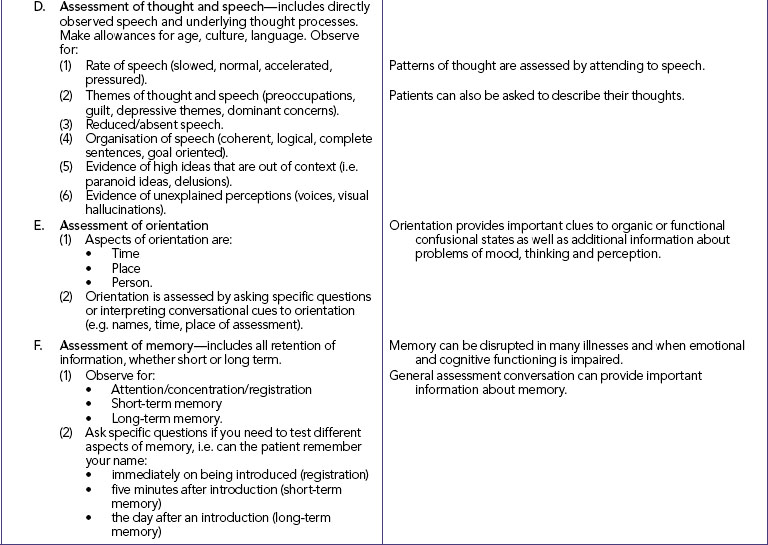

Use of language, vocabulary and non-verbal communication should be appropriate to the occasion. The ability to understand spoken or written words and to express the self through writing, words or gestures is a function of the cerebral cortex. The patient’s voice is assessed for inflection, tone and manner of speech. The patient’s voice should have inflections, be clear and strong and increase in volume appropriately. Speech should be fluent. Ineffective communication (e.g. omission or addition of letters and words, misuse of words, hesitations) is indicative of aphasia, possibly resulting from an injury to the cerebral cortex. Normally a patient names objects correctly, follows commands and reads sentences correctly.

Cognition and thought processes

The level of consciousness exists along a continuum from full waking, alertness and cooperation through to unresponsiveness to any form of external stimuli. A fully conscious patient responds to questions spontaneously. As consciousness lowers, a patient may show irritability, a shortened attention span or an unwillingness to cooperate. To avoid ambiguity in the assessment of the level of consciousness, the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) measures consciousness using an objective numerical scale (Table 27-25). Caution is needed in using the scale with patients who have sensory losses (e.g. vision or hearing or where English is a second language). As consciousness deteriorates, a patient becomes disoriented to name, time and place. Ask short, to-the-point questions regarding information that the patient knows (e.g. ‘Tell me your name’, ‘What’s the name of this place?’ and ‘What day is this?’). The patient’s ability to understand and answer questions has a direct effect on your ability to perform a complete examination.

TABLE 27-25 GLASGOW COMA SCALE

| ACTION |

RESPONSE |

SCORE |

| Eye opening |

Spontaneously |

4 |

| To speech |

3 |

| To pain |

2 |

| No response |

1 |

| Best verbal response |

Oriented |

5 |

| Confused |

4 |

| Inappropriate words |

3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds |

2 |

| No response |

1 |

| Best motor response |

Obeys commands |

6 |

| Localises to pain |

5 |

| Flexion withdrawal |

4 |

| Abnormal flexion |

3 |

| Abnormal extension |

2 |

| No response |

1 |

| Total score |

|

15 |

A patient may be unable to follow simple commands, such as ‘Squeeze my finger’. At this lowered level of consciousness the patient is often responsive only to painful stimuli. Test the patient by using a painful stimulus such as the trapezium squeeze. A patient with serious neurological impairment exhibits abnormal posturing in response to such stimuli. A flaccid response indicates the absence of muscle tone in the extremities and severe brain injury. The GCS allows an evaluation of a patient’s neurological status over time. The higher the score, the more normal or improved the level of functioning.

For the conscious and alert patient, testing of intellectual function includes memory (recent, immediate and past), knowledge, abstract thinking, association and judgment. Each aspect of intellectual function is tested through a specific technique. As cultural and educational background influences the ability to respond to test questions, do not ask questions related to concepts or ideas with which the patient is unfamiliar. Any hearing loss should be recognised in the interpretation of findings. Good communication techniques are necessary throughout the examination to ensure the patient clearly understands all directions and testing.

A problem with memory becomes apparent during the nursing history. To assess past memory, the patient is asked to recall mother’s maiden name, a birthday or a special date. It is best to ask open-ended questions rather than simple yes/no questions. A patient should have immediate recall of such information. To assess immediate recall, the patient repeats a series of numbers (e.g. 7, 4, 1) in order presented or in reverse order. Gradually increase the number of digits (e.g. 7, 4, 1, 8, 6) until the patient fails to repeat the digits correctly. Normally an individual is able to repeat a series of 5 to 8 digits forwards and 4 to 6 digits backwards. To test recent memory, say clearly and slowly the name of three unrelated objects. After saying all three ask the patient to repeat them. This is continued until the patient is successful. Then, later in the assessment, ask the patient to say the three words again. The patient should be able to identify the three words. Another test for recent memory involves asking the patient to recall events occurring during the same day (e.g. what was eaten for breakfast). Information may need to be validated with a family member. Confabulation will be evidence of the patient compensating for memory loss by using fictional information.

Knowledge can be assessed by asking patients what they know about their illnesses or the reason for seeking healthcare. By assessing knowledge, you can determine the patient’s ability to learn or understand.

Interpreting abstract ideas or concepts reflects the capacity for abstract thinking. A higher level of intellectual functioning is required for an individual to explain such phrases as ‘A stitch in time saves nine’ or ‘Don’t count your chickens before they’re hatched’. Note whether the patient’s explanations are relevant and concrete. The patient with altered mental ability is likely to interpret the phrase literally or merely rephrase the words.

Another higher level of intellectual functioning involves finding similarities or associations between concepts: a dog is to a beagle as a cat is to a Siamese. Name related concepts and ask the patient to identify their associations. Questions should be appropriate to the patient’s level of intelligence. It is sufficient to use simple concepts.

Judgment requires a comparison and evaluation of facts and ideas to understand their relationships and to form appropriate conclusions. Try to measure the ability to make logical decisions. By assessing judgment, you can also measure the ability to organise thought processes. This can be determined by asking the patient why they decided to seek healthcare or how they plan to adjust to limitations after returning home. A simpler test involves asking what patients would do if placed in a situation such as being locked out of their home or suddenly becoming ill when alone at home.

There are special assessment tools designed to assess a patient’s mental status. Kahn and Goldfarb’s mental status questionnaire (MSQ) (Kahn and others, 1960) is a 10-item instrument and a widely used tool. Folstein and others (1975) developed the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) method to measure orientation and cognitive function (Box 27-19). A maximum score on the MMSE is 30. Patients with scores of 21 or lower generally reveal cognitive impairment requiring further assessment.

BOX 27-19 MINI-MENTAL STATE EXAMINATION (MMSE)

MMSE sample items:

• Orientation to time—‘What is the date?’

• Registration—‘Listen carefully. I am going to say three words. You say them back after I stop. Ready? Here they are … APPLE (pause), PENNY (pause), TABLE (pause). Now repeat those words back to me.’ [Repeat up to 5 times, but score only the first trial.]

• Naming—‘What is this?’ [Point to a pencil or pen.]

• Reading—‘Please read this and do what it says.’ [Show examinee the words on the stimulus form: CLOSE YOUR EYES]

Reproduced by special permission of the publisher, Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Florida 33549, from the Mini Mental State Examination by Marshal Folstein and Susan Folstein, Copyright 1975, 1998, 2001 by Mini Mental LLC, Inc. Published 2001 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission of PAR, Inc. The MMSE can be purchased from PAR, Inc. by calling +1 (813) 968-3003.

Abnormal findings of cognition and perception

A common mental disorder affecting older adults is delirium. This is an acute condition characterised by confusion, disorientation and restlessness (Box 27-20). The acute condition is often misdiagnosed as a form of dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease). Thus the underlying cause of the condition is missed. Delirium is often overlooked in older adults because of a failure to adequately assess mental status, or discounted as common older adult behaviour (Flagg and others, 2010). Fortunately, the condition can be reversed when correctly assessed. Often, the delirium worsens at night. A history of patient’s behaviour before delirium developed is essential in early recognition of the condition.

BOX 27-20 CLINICAL CRITERIA FOR DELIRIUM

Definition—an acute disturbance of consciousness that is accompanied by a change in cognition. It cannot be accounted for by a pre-existing or evolving dementia. Delirium develops over a short period of time, usually hours to days, and tends to fluctuate during the course of the day. It is usually a direct physiological consequence of a general medical condition.

• There is reduced clarity of awareness of the environment.

• Ability to focus, sustain or shift attention is impaired (questions must be repeated).

• Person is easily distracted by irrelevant stimuli.

• There is an accompanying change in cognition (memory impairment, disorientation or language disturbance).

• Waxing and waning of orientation occurs through the day.

• Recent memory is most commonly affected.

• Disorientation is usually shown, with person disoriented to time or place.

• Language disturbance may involve impaired ability to name objects or ability to write; speech may be rambling.

• Perceptual disturbances may include misinterpretations, illusions or hallucinations.

Modified from American Psychiatric Association 1994 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4 (DSM-IV). Washington DC, American Psychiatric Association; Monk T, Price C 2011 Postoperative cognitive disorders. Curr Opinion Crit Care 17:376–81.

• CRITICAL THINKING

While administering medication to Mrs Marsaja, you note that she is confused as to place and time and her speech is slightly slurred. What subjective and objective data related to cognition and perception will you collect?

There are different types of cerebrovascular disease: cerebral insufficiency, infarction, haemorrhage or arteriovenous malformation causing symptoms of infarction, haemorrhage or mass lesion. Syndromes accompanying either ischaemic or haemorrhagic lesions are commonly referred to as stroke. Both ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes tend to develop abruptly and the signs and symptoms reflect the area of the brain damaged. Common symptoms include headache, altered conscious state, aphasia, dysphagia and impaired mobility (Cook and Clements, 2011). The two types of aphasia are sensory (receptive) and motor (expressive). With receptive aphasia, a person cannot understand written or verbal speech. With expressive aphasia, a person understands written and verbal speech but cannot write or speak appropriately when trying to communicate. A patient may suffer a combination of receptive and expressive aphasia, depending on the part of the cerebral cortex involved.

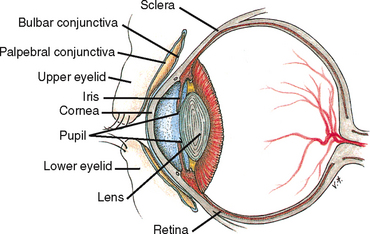

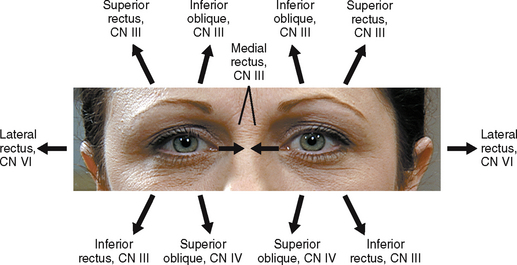

Eyes

Functional vision is important for independence in all aspects of our lives. Examination of the eyes includes assessment of visual acuity, visual fields, extraocular movements, and external and internal eye structures (Table 27-26). Figure 27-45 shows a cross-section of the eye. The assessment detects visual alterations (Box 27-21) and determines the level of assistance patients require. Patients with visual problems may also need special aids for reading educational materials or instructions (e.g. medication labels).

TABLE 27-26 NURSING HISTORY FOR EYE ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

| Determine problems that prompted patient to seek healthcare. Do you have any of the following: eye pain, photophobia (sensitivity to light), burning, itching, excess tearing or crusting, diplopia (double vision), blurred vision, awareness of a ‘film’ over field of vision, floaters (small black spots that seem to float across field of vision), flashing lights or halos around lights? |

Common symptoms of eye disease indicate need for referral to specialist |

| Do you have a history of eye disease, eye trauma, diabetes, hypertension or eye surgery? |

Some diseases or trauma can cause risk of partial or complete visual loss. Surgery may have been performed for a visual disorder |

| Is there a family history of eye disorders or diseases? |

Certain eye problems such as glaucoma or retinitis pigmentosa are inherited |

| What is your occupation? What are your hobbies? Do you wear safety glasses? |

Performance of close, intricate work can cause eye fatigue. Working with computers may cause eye strain. Certain occupational tasks (e.g. working with chemicals) and recreational activity (e.g. fencing or motorcycle riding) place people at risk of eye injury unless precautions are taken |

| Do you wear glasses or contact lenses? For what purpose? |

Glasses or contacts should be worn during certain portions of examination for accurate assessment |

| When did you last visit the ophthalmologist or optometrist? |

Date of last eye examination reveals level of preventive care taken by patient |

| What medications are you taking? Do you use eye drops or eye ointment? |

Determines need to assess patient’s knowledge of medications.

Certain medications can cause visual symptoms

|

BOX 27-21 COMMON EYE AND VISUAL PROBLEMS

Astigmatism—a condition in which parallel light rays do not focus on a single point on the retina. An uneven curvature of the cornea or lens causes light to be focused on different points.

Cataract—an increased opacity of the lens, which blocks light rays from entering the eye. Cataracts may develop slowly and progressively after age 35 or suddenly after trauma. Cataracts are one of the most common eye disorders. By age 70, most older adults have some evidence of visual impairment from cataracts.

Glaucoma—intraocular structural damage resulting from elevated intraocular pressure. It is caused by obstruction of the outflow of aqueous humour. Without treatment the disorder can cause blindness.

Hyperopia—farsightedness, a refractive error in which rays of light enter the eye and focus behind the retina. People are able to clearly see distant objects but not close objects.

Macular degeneration—blurred central vision often occurring suddenly, caused by a progressive degeneration of the centre of the retina. It is the most common visual impairment in people over age 50 and the most common cause of blindness in older adults. There is no cure.

Myopia—nearsightedness, a refractive error in which rays of light enter the eye and focus in front of the retina. People are able to clearly see close objects but not distant objects.

Presbyopia—impaired near vision in middle-aged and older adults, caused by loss of elasticity of the lens and associated with the ageing process.

Retinopathy—a non-inflammatory eye disorder resulting from changes in retinal blood vessels. It is a leading cause of blindness.

Strabismus—a congenital problem in which the eyes appear crossed. The muscles controlling movement of the eyes are not coordinated.

Hands should be washed before and after the examination, and gloves worn when palpating the eyelids.

Assessment of the eyes

VISUAL ACUITY

The assessment of visual acuity—the ability to see small details—tests central vision. If patients wear glasses, they should wear them during the examination. The language spoken and the ability to read should be assessed. Asking patients to read aloud can help determine literacy. If the patient has difficulty reading, move to the next step.

Assessment of distant vision is assessed very simply in clinical environments by asking the patient to identify objects in the distance. If patients cannot identify objects in the distance, their ability to count upraised fingers or distinguish light is assessed. A hand is held 30 cm from the patient’s face and they count the upraised fingers. Light perception is checked by shining a penlight into the eye and then turning the light off. If the patient notes when the light is turned on or off, light perception is intact. Near vision can be assessed by asking patients to read from a newspaper, wristwatch or similar item. Patients are instructed to hold the item a comfortable distance (5–6 cm) from the eyes, and to read the smallest line possible. Simple testing such as this is adequate for beginning nurses.

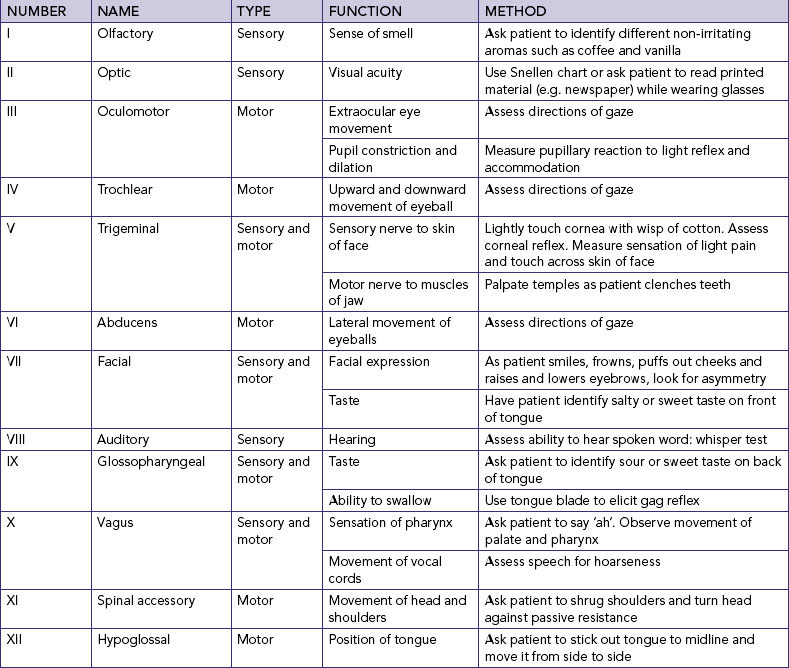

EXTRAOCULAR MOVEMENTS

Six small muscles guide the movement of each eye and three cranial nerves are involved: the oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve [CN] III), the trochlear nerve (CN IV) and the abducens nerve (CN VI; see Table 27-27). Both eyes move parallel to each other in each of the six directions of gaze (Figure 27-46). The patient sits or stands 60 cm away facing you while you hold a finger at a comfortable distance (15–30 cm) from the patient’s eyes. The patient keeps the head in a fixed position facing you and follows the movement of the finger with the eyes only. The patient looks to the right, to the left, and diagonally up and down to the left and right. Move your finger smoothly and slowly within the normal field of vision. As the patient gazes in each direction, observe for parallel eye movement, the position of the upper eyelid in relation to the iris, and the presence of abnormal movements. As the eyes move through each direction of gaze, the upper eyelid covers the iris only slightly.

Assessing the corneal light reflex can check eye alignment. A weakness or imbalance of the extraocular muscles can cause misalignment. In a darkened room and with the patient looking straight ahead, a penlight is shone onto the bridge of the patient’s nose from a distance of 60–90 cm. Normally light reflects on the cornea in the same spot on both eyes. If an abnormality is present, the light shines on a different spot on each eye.

VISUAL FIELDS

As the patient looks straight ahead, all objects in the periphery can normally be seen. To assess visual fields, the patient stands or sits 60 cm away, facing you at eye level. The patient closes or covers one eye (e.g. the left) and looks at your eye directly opposite. Close your opposite eye (in this case the right) so that the field of vision is superimposed on that of the patient. Move a finger equidistant from yourself and the patient outside the field of vision, then slowly bring it back into the visual field. Ask the patient to tell you when they first see your finger. If you see the finger before the patient does, a portion of the patient’s visual field is reduced. The procedure is repeated for each field of vision for the other eye. Patients with visual field problems may be at risk of injury because they cannot see all objects in front of them.

EXTERNAL EYE STRUCTURES

To inspect external eye structures, stand directly in front of the patient at eye level and ask the patient to look at your face.

Assess the position of the eyes in relation to each other; they are normally parallel to each other.

EYEBROWS

Eyebrows are normally symmetrical. They are inspected for size, extension, texture of hair, alignment and movement. A loss or absence of hair may indicate a hormonal disturbance or be the result of waxing or plucking. Ageing causes loss of the lateral third of the eyebrows. The brows should rise and lower symmetrically.

EYELIDS

The eyelids are inspected for position, colour, condition of the surface, condition and direction of the eyelashes and the patient’s ability to open and close the eyes and to blink. When the eyes are open in a normal position, the lids do not cover the pupil and the sclera cannot be seen above the iris. The eyelashes are normally distributed evenly and curved outwards away from the eye. The eyelids are normally smooth and the same colour as the skin. The lids normally close symmetrically. Ask the patient to open their eyes for inspection of the lower lids. The same characteristics as for the upper lids are assessed. Normally a person blinks involuntarily and bilaterally up to 20 times a minute. The blink reflex helps lubricate the cornea. Note and report absent, infrequent, rapid or monocular (one-eyed) blinking.

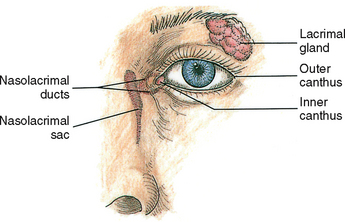

LACRIMAL APPARATUS

The anterior surface of the eye, made up of the sensitive cornea and conjunctivae, is moistened or lubricated by tears secreted from the lacrimal gland (Figure 27-47). The gland is located in the upper outer wall of the anterior part of the orbit. Tears flow from the gland across the eye’s surface to the lacrimal duct, which is located in the nasal corner or inner canthus of the eye. The lacrimal gland can be the site of tumours or infections. The area of the gland is inspected for oedema and redness, and it is palpated gently to detect tenderness. Normally the gland cannot be felt. Mild palpation of the duct at the lower eyelid just inside the lower orbital rim, not on the side of the nose, may cause a regurgitation of tears.

CONJUNCTIVAE AND SCLERAE

The bulbar conjunctiva covers the exposed surface of the eyeball up to the outer edge of the cornea, and the palpebral conjunctiva is the delicate membrane lining the eyelids. Normally the conjunctiva is transparent, enabling the examiner to view the tiny underlying blood vessels that give it a light-pink colour. The sclera is seen under the bulbar conjunctiva and normally is the colour of white porcelain in Caucasians and light-yellow in dark-skinned people.

CORNEAS

The cornea is the transparent, colourless portion of the eye covering the pupil and iris. As the patient looks straight ahead, inspect the cornea for clarity and texture while shining a penlight obliquely across the cornea’s entire surface. The cornea is normally shiny, transparent and smooth. However, in older adults the cornea loses its lustre. Any irregularity in the surface may indicate an abrasion or tear that warrants immediate examination by a specialist. The colour and details of the underlying iris should be easy to see. In older adults the iris becomes faded. A thin white ring along the margin of the iris, called an arcus senilis, is common with ageing but is abnormal in anyone aged under 40 years.

PUPILS AND IRISES

Observe the pupils for size, shape, equality, accommodation and reaction to light. The pupils are normally black, round, regular and equal in size (3–7 mm in diameter) (Figure 27-48). The iris should be clearly visible. Pupillary reflexes (to light and accommodation) are tested in a dimly lit room. As the patient looks straight ahead, bring a penlight from the side of the patient’s face, directing the light onto the pupil (Figure 27-49). If the patient looks at the light, there will be a false reaction to accommodation (adjustment). A directly illuminated pupil constricts, and the opposite pupil constricts involuntarily in correlation. Observe the quickness and equality of the reflex of both eyes.

To test for accommodation, the patient gazes at a distant object (the far wall) and then at a test object (finger or pencil) held approximately 10 cm from the bridge of the patient’s nose. The pupils normally converge and adjust by constricting when looking at close objects. The pupillary responses are equal. Testing for accommodation is important if the patient has a defect in the pupillary response to light (Seidel and others, 2011). If pupillary reaction is normal in all tests, the abbreviation PERRLA (pupils equal, round, reactive to light and accommodation) is recorded.

Abnormal findings of the eye

Hyperthyroidism, tumours or inflammation of the orbit usually cause bulging of the eyes (exophthalmos) (Holcomb, 2002). Crossing of eyes (strabismus) results from neuromuscular injury or inherited abnormalities. Paralysis of the facial nerve exists if a patient cannot move the eyebrows. Nystagmus, an involuntary, rhythmical oscillation of the eyes, reflects local injury to eye muscles and supporting structures or a disorder of the cranial nerves innervating the muscles (Fetzer, 2000). Nystagmus might be apparent in some patients when checking extraocular movements.

An abnormal drooping of the lid over the pupil is called ptosis (pronounced ‘toe-sis’) and is caused by oedema or impairment of the third cranial nerve. Defects in the position of the lid margins may also be observed. An older adult frequently has lid margins that turn out (ectropion) or in (entropion). An entropion may lead to the lid’s lashes irritating the conjunctiva and cornea, increasing the risk of infection. Failure of the lids to close exposes the cornea to drying. This condition is common in unconscious patients or in those with facial nerve paralysis. Lid oedema may be due to allergies or to heart or kidney failure.

An erythematous or yellow lump (hordeolum or stye) on the follicle of an eyelash indicates an acute suppurative inflammation. Redness indicates inflammation or infection. Lesions are inspected for typical characteristics and discomfort or drainage. Gloves should be worn if drainage is present. The nasolacrimal duct may become obstructed, blocking the flow of tears. If the patient complains of excessive eye-watering, look for evidence of oedema in the inner canthus.

CONJUNCTIVAE AND SCLERA

Sclerae may become pigmented and appear either yellow or green if liver disease is present (Tizzard and Davenport, 2007). The presence of redness may indicate an allergic or infectious conjunctivitis. Bright-red blood in a localised area surrounded by normal-appearing conjunctiva usually indicates subconjunctival haemorrhage. A pale conjunctiva results from anaemia, whereas a fiery red appearance is a result of inflammation (conjunctivitis). Conjunctivitis is a highly contagious infection. The crusty drainage that collects on eyelid margins can easily spread from one eye to the other.

PUPILS

Cloudy pupils indicate cataracts. Dilated pupils can result from glaucoma, trauma, neurological disorders, eye medications (e.g. atropine) or withdrawal from opioids. Constricted pupils may be caused by inflammation of the iris or use of drugs (e.g. pilocarpine, morphine or cocaine). Pinpoint pupils are a common sign of opioid intoxication (Dixon, 2007). Examination with a beam of light aims to assess the afferent (optic nerve) and efferent (parasympathetic via third cranial nerve constricting and sympathetic dilating) pathways of the pupillary reflexes (Fuller and Manford, 2010). Any abnormality along the nerve pathways from the retina to the iris alters the ability of the pupils to react to light. Changes in intracranial pressure, lesions along the nerve pathways, locally applied ophthalmic medications and direct trauma to the eye may alter pupillary reaction.

Ears

Ear assessment is used to determine the integrity of ear structures and the condition of hearing. Nursing history data (Table 27-28) help identify risks of hearing disorders. Ear examination is focused on assessment of pain, discharge or presence of lumps or foreign objects. Internal and external examination of the ears will detect evidence of ear pressure, fullness, pain and excessive cerumen (ear wax).

TABLE 27-28 NURSING HISTORY FOR EAR ASSESSMENT

| ASSESSMENT QUESTIONS |

RATIONALE |

| Do you have any of the following: ear pain, itching, discharge, vertigo, tinnitus (ringing in ears) or change in hearing? |

These signs and symptoms indicate infection or hearing loss |

Assess risks of hearing problem:

Infants/children—hypoxia at birth, meningitis, birthweight less than 1500 g, family history of hearing loss, congenital anomalies of skull or face, non-bacterial intrauterine infections (rubella, herpes), maternal drug use, excessively high bilirubin, head trauma

Adults—exposure to industrial or recreational noise, genetic disease (Ménière’s disease), neurodegenerative disorder

|

Risk factors predispose patient to permanent hearing loss.

It may be difficult to assess infant’s hearing status with examination only

|

| Do you experience loud noises at work ? Are protective devices available? Do you wear them? |

Prolonged noise exposure can cause temporary or permanent hearing loss |

| Note behaviours indicative of hearing loss, such as failure to respond when spoken to, requests to repeat comments, leaning forward to hear and child’s inattentiveness or use of monotonous voice tone |

Persons with hearing loss cope with sensory deficit through a variety of behavioural cues |

| What medications do you take? |

Some medications are ototoxic, e.g. large doses of aspirin, aminoglycosides, furosemide, streptomycin, cisplatin, ethacrynic acid |

| Do you use a hearing aid? |

Determination allows nurse to assess effectiveness, ability to care for device and allows nurse to adjust voice tone to communicate |

| Have you had a recent hearing problem? Describe the onset, contributing factors, affected ear and effect on activities for daily living |

Nature and severity of hearing problem are determined |

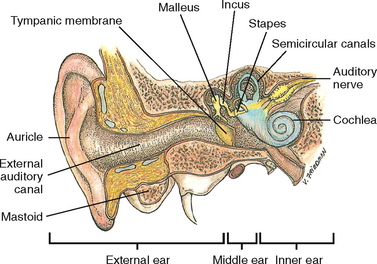

The ears are easy to examine because of their accessibility. The three parts of the ear are the external, middle and inner ear (Figure 27-50). The external ear includes the auricle and external auditory meatus (ear canal). The middle ear is an air-filled cavity containing the three bony ossicles (malleus, incus and stapes). The eustachian tube connects the middle ear to the nasopharynx. Pressure between the outer atmosphere and the middle ear is stabilised through the eustachian tube. The inner ear contains the cochlea, vestibule and semicircular canals. The inner ear consists of the bony labyrinth, the semicircular canals and the membranous labyrinth.

Understanding the mechanisms for sound transmission helps identify the nature of hearing disorders. Sound travels through the ear by air and bone conduction; the following explains the steps of hearing.

• Sound waves in the air enter the external ear, passing through the outer ear canal.

• The sound waves reach the tympanic membrane, causing it to vibrate.

• Vibrations are transmitted through the middle ear by the bony ossicular chain to the oval window at the opening of the inner ear.

• The cochlea receives the sound vibration.

• Nerve impulses from the cochlea travel to the auditory (eighth cranial) nerve and to the cerebral cortex.

Inspection of the ear

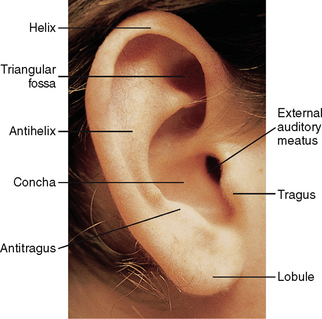

AURICLES

With the patient sitting comfortably, inspect and palpate the auricle’s size, shape, symmetry, landmarks, position and colour (Figure 27-51). The auricles are normally level with each other. The upper point of attachment is in a straight line with the lateral canthus, or corner of the eye. The position of the auricle should also be almost vertical. As you palpate the ears for tenderness and lesions, note the condition of the skin. The colour should be the same as that of the face, without moles, cysts, deformities or nodules. Palpate the auricles for texture, tenderness and skin lesions. The auricle is normally smooth, without lesions. If the patient reports pain, gently pull the auricle, press on the tragus and palpate behind the ear over the mastoid process.

Inspect the opening of the ear canal for size and discharge. Discharge may be accompanied by an odour. The meatus should not be swollen or occluded. Cerumen, a yellow, waxy substance, is common. The deeper structures of the external and middle ear can only be observed with an otoscope, which is usually only performed by advanced practice nurses.

HEARING ACUITY

Hearing loss can be determined from the patient’s response to conversation. The three types of hearing loss are conduction, sensorineural and mixed. A conduction loss interrupts sound waves as they travel from the outer ear to the cochlea of the inner ear because the sound waves are not transmitted through the outer and middle ear structures. Causes of a conduction loss include swelling of the auditory canal or tears in the tympanic membrane. A sensorineural loss involves the inner ear, auditory nerve or hearing centre of the brain. Sound is conducted through the outer and middle ear structures, but the continued transmission of sound becomes interrupted at some point beyond the bony ossicles. A mixed loss involves a combination of conduction and sensorineural loss.

Note the patient’s response to questions and any need to repeat questions. If hearing loss is suspected, the patient’s response to the whispered voice is assessed. One ear is tested at a time while the patient occludes the other ear with a finger. The patient is asked to gently move the finger in their ear up and down during the test. While standing 30–60 cm from the ear being tested, cover your mouth so that the patient is unable to read lips. After exhaling fully, the nurse first whispers softly towards the unoccluded ear, reciting random numbers with equally accented syllables, such as nine-four-ten. If necessary, voice intensity is gradually increased until the patient correctly repeats the numbers. The other ear is then tested for comparison.

People working or living around loud noises are at risk of hearing loss. Older adults experience an inability to hear high-frequency sounds and consonants (e.g. S, Z, T and G). Deterioration of the cochlea and a thickening of the tympanic membrane cause older adults to gradually lose hearing acuity. They are especially at risk of hearing loss due to ototoxicity (injury to auditory nerve) resulting from high-maintenance doses of antibiotics (e.g. aminoglycosides).

Abnormal findings of the ear

Disorders of the ear result from several types of problems, including mechanical dysfunction (blockage by ear wax or foreign body), trauma (foreign bodies or noise exposure), neurological disorders (auditory nerve damage), acute illnesses (viral infection) and toxic effects of medications.

If palpating the external ear increases pain, an external ear infection is likely. If palpation does not influence the pain, the patient may have a middle ear infection (Warren, 2008). Tenderness in the mastoid area can indicate mastoiditis. Yellow or green foul-smelling discharge may indicate infection or a foreign body.

Ears that are low-set or at an unusual angle are a sign of chromosome abnormality (e.g. Down syndrome) (Ranweiler, 2009). Redness is a sign of inflammation or fever. A reddened canal with discharge is a sign of inflammation or infection. Accumulated cerumen is a common problem and its build-up can create a mild hearing loss. During the examination, the examiner asks about methods that the patient uses to clean the ear canal (Box 27-22). A pink or red bulging tympanic membrane indicates inflammation. A white colour reveals pus behind it.

BOX 27-22 CLIENT TEACHING DURING EAR ASSESSMENT

OBJECTIVES

• Patient will use proper technique for cleaning the ears.

• Patient will follow preventive guidelines for screening of hearing loss.

• Patient with hearing loss will communicate effectively.

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Instruct patient about the proper way to clean the outer ear (see Chapter 34), avoiding use of cotton-tipped applicators and sharp objects such as hairpins, which may cause impaction of cerumen deep in the ear canal.

• Encourage patients over age 65 to have regular hearing checks. Explain that a reduction in hearing is a normal part of ageing.

• Instruct family members of patient with hearing loss to avoid shouting, speaking instead in low tones, and to be sure the patient can see the speaker’s face.

EVALUATION

• Patient will use a safe technique for cleaning the ears.

• Patient will have frequent hearing checks.

If a hearing loss is present, referral is made to a specialist. If the patient has a known hearing loss, then encourage the use of hearing aids.

Sensory function

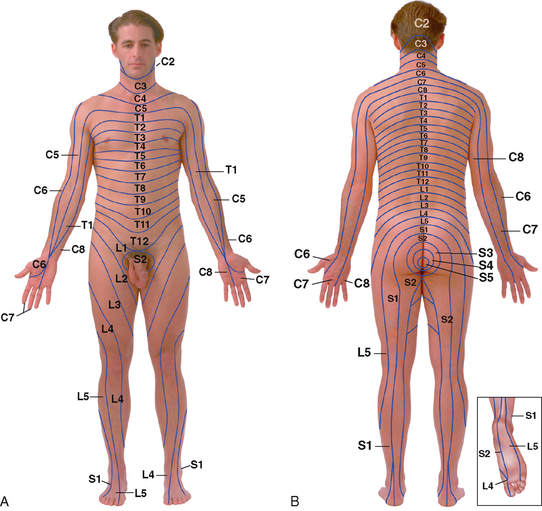

The sensory pathways of the central nervous system conduct information about pain, temperature, position, vibration, and crude and finely localised touch. Different pathways relay the sensations. For most patients, a quick screening of sensory function is sufficient unless there are symptoms of reduced sensation, motor impairment or paralysis.

Normally a patient has sensory responses to all stimuli tested. Sensations along the body’s surface are felt equally on both sides of the face, trunk and extremities. A knowledge of the sensory dermatome zones (Figure 27-52) is essential. Some areas of the skin are innervated by specific dorsal-root cutaneous nerves. For example, if reduced sensation is noted when checking for light touch along an area of the skin (e.g. the lower neck), the existence of a neurological lesion can be determined (e.g. fourth cervical spinal cord segment).

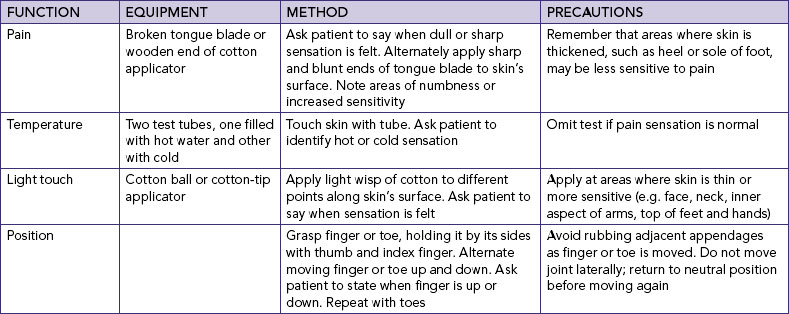

All sensory testing is performed with the patient’s eyes closed so that the patient is unable to see when or where a stimulus strikes the skin (Table 27-29). Stimuli are applied in a random, unpredictable order to maintain the patient’s attention and prevent detection of a predictable pattern. The patient is asked to tell the nurse when, what and where each stimulus is felt. Compare symmetrical areas of the body while applying stimuli to the patient’s arms, trunk and legs.

SKILL 27-6 Assessment of central nervous system and level of consciousness

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

Assessment of the central nervous system (CNS) may be undertaken by enrolled nurses under the guidance of the registered nurse.

• Ensure review of the anatomy and physiology of the CNS for risk factors

• Ensure review of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

• Ensure hand hygiene is performed and personal protective equipment is worn when appropriate.

EQUIPMENT

• Penlight torch

• Neurological observation chart

• Pen

References: Forbes H, Watt E 2012 Jarvis’s Physical examination and health assessment. Sydney, Saunders Australia. National Stroke Foundation (NSF) 2012 Spread the word F.A.S.T. (blog). Melbourne, NSF. Online. Available at www.strokefoundation.com.au/blog/?tag=fast 27 Apr 2012.

| STEPS |

RATIONALE |

1. Determine need to assess neurological status of patient.

|

Certain conditions place patients at risk of neurological alterations (stroke, seizure, paralysis). Physical signs and symptoms such as confusion, drowsiness and limb weakness may indicate alterations in neurological function. As cognitive function deteriorates, the patient becomes disorientated to time, place and person and is unable to process and demonstrate higher order functioning. |

2. Focused health history

|

The focused neurological health history provides insight into the link between a patient’s lifestyle and neurological information and pathology. |

| |

a. Determine chief complaint—characteristics of pain and each sign/symptom using the PQRST approach (see Chapter 6).

|

|

| |

b. Ascertain presence of:

• seizure—location (i.e. body parts involved), quantity in time, quality (general or localised) • associated manifestations—incontinence, injury, memory loss and cyanosis • aggravating factors—bright/flashing lights, TV, sleep deprivation, stress, fever in children, alcohol.

|

|

| |

c. Ask about setting—warning aura, sequence of events, e.g. headache

|

|

| |

d. Ask about timing—first onset.

|

|

| |

e. Assess syncope—quality, i.e. total vs partial loss of consciousness; and quantity in time.

|

|

| |

f. Assess pain—location and quality

|

|

| |

g. Assess paraesthesia and associated manifestations, e.g. pain, stiffness, gait changes, poor peripheral pulses, injury

|

|

| |

h. Assess disturbances in gait: quality—ataxic, spastic, hemiplegic

|

|

| |

i. Assess visual changes: quality—blindness, in particular fields of vision, blurred vision, bright/flashing lights

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

k. Assess for memory disorders: quality—recent or remote memory loss

|

|

| |

l. Assess for dysphasia or dysphagia.

|

|

| |

m. Determine past history of neurological-specific conditions and surgery, and non-neurological-specific conditions.

|

|

| |

n. Ask about social history—alcohol use, work environment, recreation and leisure, sexual practice, stress.

|

|

3. Explain procedure to patient and clarify any concerns.

|