Chapter 44 Acute care

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Identify reasons for a client being admitted to the acute care environment.

• Explain the concepts of preoperative and postoperative nursing care.

• Differentiate between classifications of surgery.

• Explain factors to include in the preoperative assessment of a surgical client.

• Describe the implications of witnessing a client’s informed consent for surgery.

• Demonstrate postoperative exercises: diaphragmatic breathing, coughing, turning and leg exercises.

• Identify specific evaluation criteria to determine the effectiveness of preoperative client education.

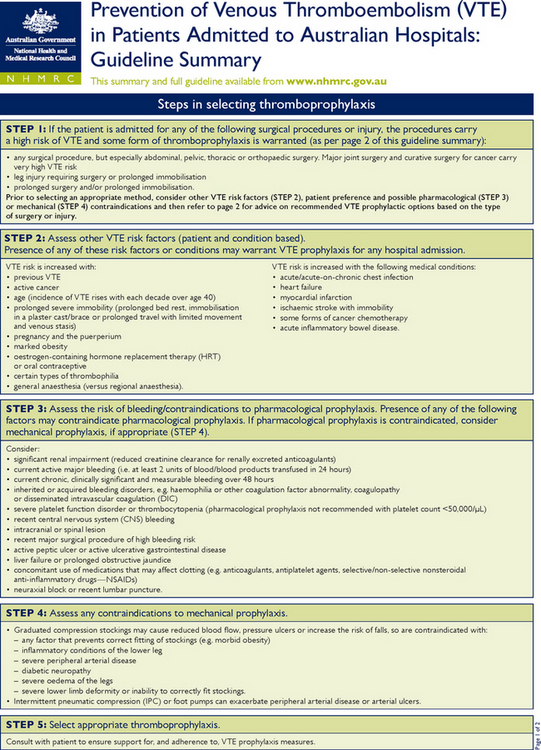

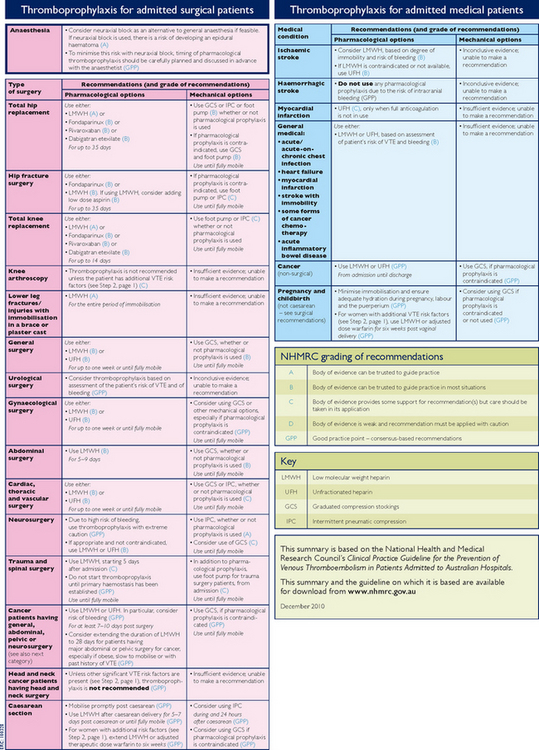

• Discuss the interventions to prevent venous thromboembolism in medical and surgical clients in the acute care setting.

• Prepare a client for surgery.

• Explain the nursing implications for clients who have had general, regional or local anaesthesia.

• Explain the rationale for specific nursing interventions designed to prevent postoperative complications.

• Identify specific evaluation criteria to determine the effectiveness of postoperative nursing care.

• Explain the difference and similarities in caring for surgical and medical clients.

• Discuss the factors to be considered for the discharge of a client from acute care.

Acute care

Acute care encompasses public or private hospital settings, large teaching hospitals and smaller ambulatory-care facilities. A client may enter the acute care setting due to a medical illness, need for surgery or for diagnostic purposes. Clients may be admitted to an acute care setting for a variety of reasons: an emergency or unplanned admission (e.g. injured in a car accident, chest pain, loss of consciousness), for elective planned surgery or treatment (e.g. total hip replacement, chemotherapy, day surgery), for review (e.g. in outpatients) or for ongoing treatment in their own home (hospital in the home). Many clients in the acute setting have complex illnesses and are seriously ill. They may be treated in the emergency department, a medical or surgical unit, a day-care or short-stay unit or an intensive care unit (ICU). Large public and private hospitals will have specialised medical and surgical units, such as a respiratory unit or cardiac unit, while smaller hospitals tend to have more-generalised medical and surgical units. Although the specific acute care setting may differ, the knowledge and skills required of registered nurses practising in acute areas in Australia and New Zealand are universal. This chapter will focus on the specific knowledge and skills required of nurses in general acute care settings. Discussion of advanced practice areas within the acute care setting, such as the ICU, coronary care unit and operating theatre, are beyond the scope of this chapter. These are areas where advanced nursing knowledge and skill is demanded.

Clients may be admitted for an acute medical reason, or for treatment of acute-on-chronic condition. An acute illness is generally recognised to be an illness that lasts for less than 3 months. For example, an elderly client admitted with pneumonia or a teenager having an appendectomy (removal of the appendix) would be considered to have had an acute illness. In contrast, a chronic illness is one that lasts for more than 3 months (e.g. asthma, emphysema, diabetes). When a client is admitted with an exacerbation of a chronic illness this is referred to as an acute-on-chronic admission. An exacerbation refers to an increase in severity of the signs and symptoms of a disease or the worsening of a disease (e.g. acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). The condition has worsened to the extent that it requires medical and nursing management in the acute care setting.

Whether a client is admitted for surgical, medical or diagnostic reasons, or a combination of these, there are common patient problems that the nurse must manage. These will be outlined and discussed in this chapter. While many of these problems are also addressed in other chapters, here they will be discussed in the context of managing a client in the acute care setting. As many clients entering the acute care setting undergo surgery, the nursing management of clients both before and after surgery will be a key focus of this chapter.

• CRITICAL THINKING

Reflect on the reasons why people you know were admitted to an acute care setting. Was it for surgical, medical or diagnostic purposes? Make a judgment as to whether each individual’s admission was due to an acute, chronic or acute-on-chronic health problem.

Acute care nursing is complex work. Management of clients admitted to an acute care setting requires multidisciplinary teamwork; effective and therapeutic communication and collaboration with the client and their family/significant others; accurate client assessment; problem identification and the implementation of priority interventions and ability to evaluate their effectiveness; and advocacy for the client and their family. The nurse documents care and maintains client safety at all times. Effective client education and discharge planning are needed to prevent or minimise complications and to ensure high-quality outcomes. The nursing process provides a problem-solving approach to the management of an acute care client, with individualised strategies so that the client has a smooth course from admission into the healthcare system to rehabilitation, home or a long-term care facility.

To meet the holistic needs of the client, nurses develop a plan of care based on multiple factors. Considerations include such things as developmental factors that relate to the client, cultural influences, family factors, lifestyle issues and emotional issues.

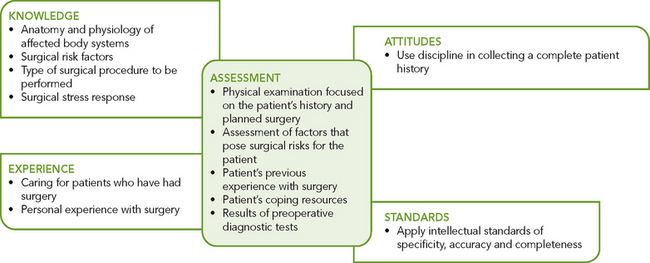

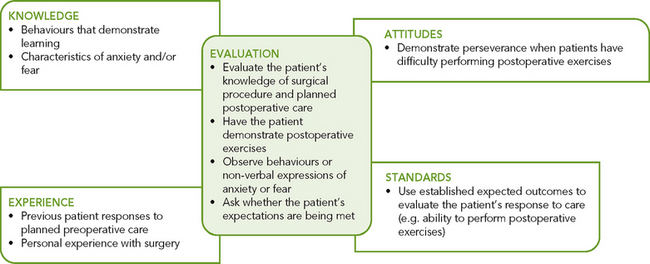

Clinical decision making requires the ability to anticipate necessary information, analyse data and make decisions regarding client care (see Figure 44-1). In the case of caring for the perioperative client, the nurse integrates knowledge from anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, along with previous experiences in caring for surgical clients and information gathered from the specific client, to make clinical decisions regarding the client’s care. Critical thinking skills are necessary to develop an individualised plan of care that provides preoperative and postoperative nursing care that is evidence-based, focused on high-quality outcomes and minimises and manages risk (e.g. airway management, infection control, pain management and discharge planning).

The client experiencing surgery

Perioperative nursing care includes nursing care given before (preoperative), during (intraoperative) and after (postoperative) surgery. Intraoperative nursing takes place in the operating theatre suite and is a specialised area of nursing; however, all nurses in the acute care setting need to be skilled to manage clients preoperatively and postoperatively. Pre- and post-operative care may take place in a hospital, a surgical centre attached to a hospital, a free-standing day-surgery or an ambulatory-care centre.

Anticipating surgery may lead to fear and anxiety for clients and their families/significant others, who often associate surgery with pain, possible disfigurement, loss of independence and perhaps even death. The ability to quickly establish rapport with clients and really listen to them, so that their concerns can be discussed and alleviated, is important to the outcome of surgery. The continuing care of the surgical client has shifted from hospital-based rehabilitation to home-based rehabilitation, with the increased responsibility shifting to the client and/or family and significant others. As the length of hospital stay decreases, the educational needs of the client undergoing a surgical procedure increase. Clients are discharged home with complex conditions that require both education and follow-up by nurses. Appropriate client education is essential to ensure positive surgical outcomes (Johansson and others, 2005).

In today’s healthcare environment, surgery is not confined to the hospital setting. A large proportion of surgical procedures are completed in same-day surgery centres, and clients admitted to hospital for surgery have much shorter stays. Same-day surgery, also referred to as outpatient surgery, short-stay surgery and ambulatory surgery, has increased over the years. Centres providing these services may be hospital-based or free-standing day-surgery centres. The first Australian free-standing daysurgery unit opened in Dandenong in Victoria in 1985, and there are currently more than 215 centres in Australia (Australian Day Surgery Nurse Association [ADSNA], 2011). According to the ADSNA (2011), 50.5% of all surgery is day-surgery.

There are benefits for the client who has same-day surgery, such as the use of anaesthetic medication that metabolises rapidly with few after-effects and shorter operation times. Nurses recognise the benefit of early postoperative mobility and encourage clients to assume an active role in recovery. Same-day surgery also offers cost savings by eliminating the need for hospital stays. It also reduces the risk of adverse events associated with time in hospital, such as healthcare-associated infections.

Classification of surgery

Surgical procedures are classified according to seriousness, urgency and purpose (Table 44-1). A procedure often falls into more than one classification. For example, surgical removal of a disfiguring scar is minor in seriousness, elective in urgency and reconstructive in purpose. The same operation may be performed for different reasons on different clients. For example, a gastrectomy may be performed as an emergency procedure to resect a bleeding stomach ulcer or as an urgent procedure to remove a cancerous growth in the stomach.

TABLE 44-1 CLASSIFICATION OF SURGICAL PROCEDURES

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

| SERIOUSNESS | ||

| Major | Involves extensive reconstruction or alteration in body parts; poses great risks to wellbeing | Coronary artery bypass, colon resection, removal of larynx, resection of lung lobe |

| Minor | Involves minimal alteration in body parts; often designed to correct deformities; involves minimal risks compared with major procedures | Cataract extraction, facial plastic surgery, skin graft, tooth extraction |

| URGENCY | ||

| Elective | Is performed on basis of patient’s choice; is not essential and may not be necessary for health | Bunionectomy, facial plastic surgery, hernia repair, breast reconstruction |

| Urgent | Is necessary for patient’s health, may prevent additional problems from developing (e.g. tissue destruction or impaired organ function); not necessarily emergency | Excision of cancerous tumour, removal of gallbladder for stones, vascular repair for occluded artery (e.g. coronary artery bypass graft) |

| Emergency | Must be done immediately to save life or preserve function of body part | Repair of perforated appendix, repair of traumatic amputation, control of internal haemorrhaging |

| PURPOSE | ||

| Diagnostic | Surgical exploration that allows confirmation of diagnosis; may involve removal of tissue for further diagnostic testing | Exploratory laparotomy (incision into peritoneal cavity to inspect abdominal organs), breast mass biopsy |

| Palliative | Relieves or reduces intensity of disease symptoms; will not produce cure | Colostomy, debridement of necrotic tissue, resection of nerve roots |

| Reconstructive/restorative | Restores function or appearance to traumatised or malfunctioning tissues | Internal fixation of fractures, scar revision |

| Constructive | Restores function lost or reduced as result of congenital anomalies | Repair of cleft palate, closure of atrial septal defect in heart |

| Cosmetic | Performed to improve personal appearance | Blepharoplasty to modify eyelid; rhinoplasty to reshape nose |

THE NURSING PROCESS IN THE PREOPERATIVE SURGICAL PHASE

In the preoperative phase, the nurse’s role centres on (1) identifying actual or potential problems using assessment skills and interviewing techniques, (2) validating existing information and (3) preparing the client both physically and emotionally for surgery. Other responsibilities involve education of the client and family/significant others relating to assuming self-care, or the provision of ongoing care for clients requiring extended observation and interventions.

Surgical clients enter the acute care setting in different stages of health and with different levels of preparedness. A client may enter the hospital or surgical unit on a predetermined day being relatively healthy, or with a significant medical history that may affect the surgery and subsequent recovery, and feel prepared to undergo elective surgery. In contrast, an individual involved in a motor vehicle accident facing emergency surgery will feel totally unprepared for such an event. The ability to quickly establish and develop rapport with the client and maintain a professional relationship is an essential component of the preoperative phase.

The surgical client may undergo tests and procedures to establish baseline measurement of relevant body systems. Testing may be performed the day before surgery or, if required for clients scheduled for same-day surgery, the tests may be conducted several days before surgery. Testing performed on the day of surgery is usually limited to such areas as glucose monitoring for a client with a history of diabetes. You should become familiar with these tests, their purpose and be able to interpret the results.

During an acute care admission, the client meets many healthcare professionals other than nurses. This team includes surgeons, anaesthetists and relevant allied health professionals such as a physiotherapist, dietitian and occupational therapist. All play a role in the client’s care and recovery. While family members and significant others attempt to provide support through their presence, they are often as stressed as the client. To recognise this, the nurse must effectively communicate with the client and family because the nurse–client relationship is the foundation of care (see Chapter 12). The nurse assesses the client’s physical and psychosocial status, recognises the degree of surgical risk, gathers results of diagnostic tests, identifies the client’s priority problems and interventions and establishes outcomes in collaboration with the client and the client’s family. Pertinent data and the plan of care are communicated to the surgical team.

ASSESSMENT

Assessment of the preoperative surgical client can be extensive. Same-day surgery can provide challenges in gathering a complete assessment within a limited timeframe. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential. Clients are admitted only hours before surgery, so nurses organise and verify data obtained preoperatively to implement a plan of care. This occurs not only with the same-day client but also with the client who will require a more prolonged hospital stay. It has become common practice for clients to be admitted on the day of surgery, even for major procedures such as open heart surgery or craniotomy. The majority of assessments begin before admission for surgery in the medical practitioner’s office, preadmission clinic, anaesthesia clinic or by telephone. Clients may answer a self-report checklist, the nurse may conduct a physical examination, laboratory tests may be required, education is commenced, client questions are answered and documentation is initiated. This streamlines the care required by the client on the day of surgery. Nurses in the immediate preoperative period are well positioned to assess the client’s understanding of previous education and individualise client and family care.

For clients undergoing elective surgery, a comprehensive history and physical examination is usually performed by a medical practitioner prior to admission, with follow-up by the preadmission or admitting nurse. In this case the nurse needs to review findings of assessments and testing already completed so as not to waste time duplicating information. The nurse focuses on key assessments for all body systems to ensure that no obvious issues are overlooked, and clarifies that the client has understood education previously provided. Even though the surgeon will screen the client before scheduling surgery, preoperative assessment occasionally reveals an abnormality that delays or cancels surgery. For example, the client may have a cough and low-grade fever on admission. This may indicate the onset of infection, and the surgeon will need to be notified immediately. Further education regarding the procedure and related care may also be required if the client demonstrates a knowledge deficit.

The intention of the assessment of the preoperative client is the same no matter what the setting. The intent is to establish the client’s normal preoperative function to assist the nurse in preventing and recognising possible postoperative complications, thereby minimising risk, and to assist the client to return to their previous functional status.

Nursing history

The nurse conducts an initial interview to collect a client history similar to that described in Chapter 27. If a client is unable to provide all of the necessary information, the nurse relies on family members, caregivers or significant others as resources. Various conditions and factors increase a person’s risk for surgery. Knowledge of risk factors enables the nurse to take the necessary precautions to plan effective and individualised care.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY

A review of the client’s medical history should include the main reason for seeking healthcare, and any illnesses. The client’s healthcare record provides this information and is an excellent resource, as are the healthcare records from any previous hospitalisations in partner hospitals.

Pre-existing illnesses and lifestyle behaviours can influence the choice of anaesthetic agents used, as well as the client’s ability to tolerate surgery and reach full recovery (Table 44-2). Preoperative clients must be carefully screened for medical conditions that may increase the risk of complications during or after surgery. For example, a client with a history of heart failure may experience a further decline in cardiac function both intraoperatively and postoperatively. Intravenous fluids may need to be administered at a slower rate, or a diuretic may need to be given after a blood transfusion.

TABLE 44-2 MEDICAL CONDITIONS THAT INCREASE THE RISKS OF SURGERY

| TYPE OF CONDITION | REASON FOR RISK |

|---|---|

| Bleeding disorders (thrombocytopenia, haemophilia) | Disorders increase risk of haemorrhaging during and after surgery |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Heart disease (recent myocardial infarction, dysrhythmias, heart failure) and peripheral vascular disease | |

| Upper respiratory infection | Infection increases risk of respiratory complications during anaesthesia (e.g. pneumonia and spasm of laryngeal muscles) |

| Liver disease | Liver disease alters metabolism and elimination of drugs administered during surgery and impairs wound healing and clotting time because of alterations in protein metabolism |

| Fever | Fever predisposes patient to fluid and electrolyte imbalances and may indicate underlying infection |

| Chronic respiratory disease (emphysema, bronchitis, asthma) | |

| Immunological disorders (leukaemia, acquired immune deficiency syndrome, bone marrow depression and use of chemotherapeutic drugs) | Immunological disorders increase risk of infection and delay wound healing after surgery |

| Recreational IV drug use | Persons using recreational IV drugs may have underlying disease (HIV/hepatitis), which affects healing |

| Chronic pain | Regular use of pain medications may result in higher tolerance. Increased doses of opioids/analgesics may be required to achieve postoperative pain control |

PAST SURGICAL HISTORY

A client’s past experience with surgery can influence physical and psychological responses to a procedure. The previous type of surgery, level of discomfort, extent of disability and overall level of care provided are factors the nurse asks the client to recall. The nurse assesses any complications that the client experienced. Anaesthesia records may be useful if any previous problems occurred. This information helps the nurse anticipate the client’s preoperative and postoperative needs.

Previous surgery may also influence the level of physical care required after a surgical procedure. For example, a client who has had a previous thoracotomy for resection of a lung lobe has a greater risk of postoperative pulmonary complications than a client with intact normal lungs.

PERCEPTIONS AND UNDERSTANDING OF SURGERY

The surgical experience affects not only the client, but also the family and/or significant others. It is therefore important for the nurse to prepare both the client and their significant other(s) regarding the surgical experience. Identification of the client’s and family’s knowledge, expectations and perceptions allows the nurse to plan education and to provide the appropriate support.

Each client brings certain fears to the surgical setting. Some are due to past hospital experiences, family and friends’ experiences, events they might have seen on television or a lack of knowledge. During the assessment, the nurse asks for a description of the client’s understanding of the planned surgery and its implications. The nurse might ask questions such as ‘Explain what you know about the surgery you are having’ or ‘What do you think will happen after the surgery?’ The nurse should contact the surgeon if the client has an inaccurate perception or knowledge of the surgical procedure, before the client is transported to the theatre suite. The nurse also determines whether the surgeon explained preoperative and postoperative procedures. When a client is well prepared and knows what to expect, the nurse reinforces the client’s knowledge and maintains accuracy and consistency, thus optimising outcomes.

MEDICATION HISTORY

If a client regularly uses prescription or over-the-counter medicines, the surgeon or anaesthetist may temporarily discontinue the medicines before surgery or adjust the dosages. Certain medicines have implications for the surgical client, creating greater risk for complications. For example, anticoagulants alter normal clotting times and therefore increase the risk of haemorrhaging. Aspirin is a commonly used medication that can alter clotting mechanisms and is usually discontinued for at least 48 hours prior to surgery. Some clients who usually administer insulin for diabetes may need a reduced dose following surgery because of a reduced nutritional intake; others may need an increased dose due to the stress response and intravenous infusion of glucose solutions during surgery.

Clients should also be specifically asked if they use any herbal preparations, since many clients do not view herbs as medications and may omit them from their medication history. There are herbs that may interfere with the action of other medicines (consult the pharmacist).

ALLERGIES

To minimise risk, it is critical for the nurse to ask the client if they have known allergies to any medicines, latex, food and possible contact allergies (e.g. to tapes, ointments or solutions). If the client identifies any allergy, you should follow the institution’s policy and procedures regarding documenting and alerting other healthcare professionals to the client’s allergy. A client may be young or have had limited exposures to medication and thus may not know whether an allergy exists. However, a client who has other allergies is at greater risk of medicine-related allergies.

Detail regarding the type of response to the drug or substance is also important. Allergies need to be delineated from adverse reactions or side effects (see Chapter 31 for a discussion of these terms). For example, a client may state that they are ‘allergic’ to morphine because it caused pruritus and nausea, which are in fact side effects. Asking the client about latex allergy is important, as a latex-free environment must be provided for clients with a known latex allergy.

SMOKING HABITS

The client who smokes is at greater risk of postoperative pulmonary complications. Someone who has smoked chronically already has an increased amount and thickness of mucous secretions in the lungs. General anaesthetics increase airway irritation and stimulate pulmonary secretions, which are retained as a result of reduction in ciliary activity during anaesthesia. After surgery the client who smokes has greater difficulty clearing the airways of mucous secretions, and the importance of postoperative deep-breathing and coughing must be emphasised (see Chapter 40).

ALCOHOL AND SUBSTANCE USE

Alcohol and substance misuse can affect the choice of anaesthetic agents and postoperative pain management. The client can develop a cross-tolerance to anaesthetic drugs, necessitating higher than normal doses. Excessive alcohol ingestion can also lead to malnutrition, which may contribute to delayed wound healing as well as to liver disease, portal hypertension and oesophageal varices (predisposing the client to bleeding disorders). The client who remains in hospital longer than 24 hours is also at risk of acute alcohol withdrawal and its more severe form, delirium tremens (DTs), and may need specific treatment (Dasgupta and Dumbrell, 2006). Use of prescription opioids or barbiturates and abuse of recreational drugs may affect the level and amount of anaesthesia required during surgery, as well as impact on the level of pain experienced, and its management, following surgery. Recreational intravenous drug use may impair the vascular system and may make venous access difficult. The client may be more likely to be exposed to blood-borne diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and hepatitis C.

AGE

Clients who are very young or old are at increased risk during surgery because of an immature or impaired physiological status. Mortality rates are higher in these clients.

During surgery performed on an infant, there is concern with maintaining normal body temperature. The infant’s shivering reflex is underdeveloped and, often, wide temperature variations occur. Anaesthesia adds to the risk because anaesthetics can cause vasodilation and heat loss. During surgery, an infant has difficulty maintaining a normal circulatory blood volume. The total blood volume of an infant is considerably less than that of an older child or an adult. Even a small amount of blood loss can be serious. A reduced circulatory volume makes it difficult for the infant to respond to the need for increased oxygen during surgery. Thus the infant is highly susceptible to dehydration. However, if blood or fluids are replaced too quickly, over-hydration may occur (Kain and others, 2007).

With advancing age, a client’s physical capacity to adapt to the stress of surgery is reduced because of deterioration in certain body functions. The majority of clients undergoing surgery are older adults. Table 44-3 summarises physiological factors that place older clients at risk during surgery.

TABLE 44-3 PHYSIOLOGICAL FACTORS THAT PLACE THE OLDER ADULT AT RISK DURING SURGERY

| ALTERATIONS | RISKS | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

|---|---|---|

| CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM | ||

| Degenerative change in myocardium and valves | Change reduces cardiac reserve | Assess baseline vital signs |

| Rigidity of arterial walls and reduction in sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation to heart | Alterations predispose patient to postoperative haemorrhage and rise in systolic and diastolic blood pressure | |

| Increase in calcium and cholesterol deposits within small arteries; thickened arterial walls | Problems predispose patient to clot formation in lower extremities | Instruct patient on techniques for performing leg exercises and proper turning; use of elastic stockings, sequential compression devices |

| INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM | ||

| Decreased subcutaneous tissue and increased fragility of skin | Patient is at higher risk for pressure injury and tears | Assess skin every 4 hours; pad all bony prominences during surgery. Turn or reposition |

| PULMONARY SYSTEM | ||

| Rib cage stiffened and reduced in size | Complication reduces vital capacity | Instruct patient on proper technique for coughing, deep-breathing and use of spirometer |

| Reduced range of movement in diaphragm | Greater residual capacity of volume of air is left in lung after normal breath increases, reducing amount of new air brought into lungs with each inspiration | When possible, have patient walk and sit in chair as much as possible |

| Stiffened lung tissue and enlarged air spaces | Alteration reduces blood oxygenation | |

| RENAL SYSTEM | ||

| Reduced blood flow to kidneys | Reduced flow increases danger of shock when blood loss occurs | For patients hospitalised before surgery, determine baseline urinary output for 24 hours |

| Reduced glomerular filtration rate and excretory times | Problem limits ability to eliminate drugs or toxic substances | |

| Reduced bladder capacity | ||

| NEUROLOGICAL SYSTEM | ||

| Sensory losses, including reduced tactile sense and increased pain tolerance | Patient is less able to respond to early warning signs of surgical complications | Orient patient to surrounding environment. Observe for non-verbal signs of pain |

| Decreased reaction time | Patient becomes easily confused after anaesthesia | |

| METABOLIC SYSTEM | ||

| Lower basal metabolic rate | Lower rate reduces total oxygen consumption | |

| Reduced number of red blood cells and haemoglobin levels | Ability to carry adequate oxygen to tissues is reduced | Administer blood products as ordered Monitor blood test results |

| Change in total amounts of body potassium and water volume | Greater risk of fluid or electrolyte imbalance occurs | Monitor electrolyte levels |

NUTRITION

Normal tissue repair and resistance to infection depend on adequate nutrients. After surgery, a client requires at least 6300 kJ/day to maintain energy reserves. Increased protein, vitamins A and C and zinc facilitate wound healing (see Chapters 30 and 36. A malnourished client is prone to poor tolerance to anaesthesia, negative nitrogen balance, delayed blood-clotting mechanisms, infection and poor wound healing, and there is the potential for multiple organ failure. It is estimated that more than half of hospitalised clients display some degree of malnutrition (Baugh and others, 2007). If a client has elective surgery, attempts to correct nutritional imbalances before surgery should be made. However, if a malnourished client must undergo an emergency procedure, efforts to restore nutrients occur after surgery.

OBESITY

Obesity also increases surgical risk. A person who is obese is more likely to have associated hypertension, heart disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, sleep apnoea and/or skin problems such as delayed wound healing (Mayo Clinic, 2011). Respiratory postoperative complications including pulmonary embolus and atelectasis (collapse of alveoli) are also more-frequent postoperative complications in clients with obesity (Poirier and others, 2009). The client may have difficulty resuming normal physical activity after surgery. Clients who are obese are more susceptible to delayed wound healing and wound infection because of the structure of fatty tissue, which contains a poor blood supply. This slows delivery of essential nutrients, antibodies and enzymes needed for wound healing (see Chapter 30 on surgical wounds). There is also a higher incidence of postoperative haematomas and seromas that may delay wound healing as well as an increased risk of wound dehiscence (Baugh and others, 2007).

FLUID AND ELECTROLYTE BALANCE

The body responds to surgery as a form of trauma. As a result of the adrenocortical stress response, hormonal reactions cause sodium and water retention and potassium loss within the first 2–5 days after surgery. Severe protein breakdown causes a negative nitrogen balance. The severity of the stress response influences the degree of fluid and electrolyte imbalance. The more extensive the surgery, the more severe the stress. A client who is hypovolaemic or who has serious preoperative electrolyte alterations is at significant risk during and after surgery. For example, an excess or depletion of potassium increases the chance of dysrhythmia during or after surgery. If the client has pre-existing renal, gastrointestinal (GI) or cardiovascular abnormalities, the risk of fluid and electrolyte alterations is even greater.

PREGNANCY

Surgery involving a woman who is pregnant demands considerations for not only the woman but also the developing fetus. Surgery is only performed for urgent reasons, or in an emergency situation. All major systems of the woman are affected during pregnancy. Cardiac output significantly increases, as does respiratory tidal volume to accommodate the increase in metabolic rate. Gastrointestinal motility decreases, hormone levels increase and energy levels decrease with advancing pregnancy. Laboratory and haemodynamic values change. Fibrinogen levels increase, so women who are pregnant are more susceptible to the development of deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) due to increased coagulability. Haemoglobin and haematocrit levels decrease, mostly as a result of the effects of haemodilution (increased circulating volume). Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and albumin levels decrease as well. White blood cell count is elevated when the woman is near term and postpartum, without the presence of infection. General anaesthesia is administered with caution because of the increased risk of fetal death and preterm labour (Robinson, 2006). The fetal heart rate may be monitored during the perioperative period. Psychological considerations for the woman and family are essential.

LEVEL OF SUPPORT

It is important to determine the extent of support from the client’s family members or significant others. Surgery often results in a temporary or permanently altered functional status that requires understanding, support and assistance to manage effectively during recovery. Often clients cannot immediately assume the same level of physical activity experienced before surgery or the illness that resulted in the surgery. Clients may return home with dressings to change, exercises to perform or with certain restrictions to adhere to. With same-day surgery, once the client has been discharged, clients and support persons assume responsibility for ongoing postoperative care. Support persons are an important resource for clients with physical limitations and help to provide the emotional support needed to motivate clients to return to their previous state of health. Involvement of support persons in preoperative and postoperative education is an important strategy to assist and encourage the client in implementing the education.

OCCUPATION

Surgery may result in an alteration in function that can hinder or prevent a person from returning to work. Assessment of the client’s occupation and expected role is important to anticipate the possible effects of surgery on recovery and eventual work performance. The nurse can explain any restrictions regarding ability to return to work. When a client is unable to return to work, in the short-term or long-term, a referral may be made to a social worker to refer the client to work-training programs or to assist the client to seek economic assistance.

PREOPERATIVE PAIN ASSESSMENT

Surgical manipulation of tissues, treatments and positioning on the operating room table usually results in some degree of postoperative pain for the client. Pain is a very personal experience and requires an individualised plan of care. Preoperatively the nurse should conduct a comprehensive pain assessment, including the client’s and support persons’ expectations regarding pain management following surgery (Gunningberg and Idvall, 2007). Preoperative education should emphasise the need for the client to report their pain using a validated pain scale and the importance of adequate pain control for their postoperative recovery. Refer to Chapter 41 for a discussion of acute pain management.

PSYCHOSOCIAL IMPACT OF SURGERY

Surgery is psychologically stressful. Clients may feel anxious about the need for surgery, the actual operation or procedure being undertaken, the subsequent implications of the surgery and the recovery period. They often feel powerless over their situation. Hospitalisation and the recovery period at home may be lengthy. Family and support persons are usually concerned about the client returning to a normal, productive life, and may perceive the surgery as a disruption to their own lifestyle. When the client has a chronic illness, those close to them may be fearful that surgery will result in further alteration in function, or hopeful that it will improve their lifestyle. To understand the impact of surgery on a client’s emotional health and on those who support them, the nurse assesses the client’s feelings about surgery, their body image and coping resources (see Box 44-1).

BOX 44-1PSYCHOSOCIAL ASSESSMENT OF THE PREOPERATIVE PATIENT

SITUATIONAL CHANGES

• Determine support systems, including family, significant others, group and institutional structure and religious and spiritual orientation.

• Define current degree of personal control, decision making and independence.

• Consider the impact of surgery and hospitalisation and the possible effects on lifestyle.

• Identify the presence of hope and anticipation of positive results.

PAST EXPERIENCES

• Review previous surgical experiences, hospitalisations and treatments.

• Determine responses to those experiences (positive and negative).

• Identify current perceptions of surgical procedure in relation to the above and information from others (e.g. a neighbour’s view of a personal surgical experience).

• Identify the accuracy of information the patient has received from others, including healthcare team, family, friends and the media.

KNOWLEDGE DEFICIT

• Identify what amount and type of preoperative information this specific patient wants to know.

• Identify what this patient must know preoperatively.

• Assess the patient’s understanding of the surgical procedure, including preparation, care, interventions, preoperative activities, restrictions and expected outcomes.

From Brown D, Edwards H 2012 Lewis’s Medical–surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, ed 3. Sydney, Mosby.

The nurse may observe overt or subtle cues suggestive of the client’s feelings about surgery as expressed through facial expressions, body language or behaviour. For example, a client experiencing fear in relation to their impending surgery may ask many questions, may seem uneasy when unfamiliar people enter the room, or actively seek the company of friends and relatives. The nurse should also be cognisant, however, of not making assumptions about the client’s emotional status based only on their observations. Further assessment data should be collected to ensure a comprehensive understanding is attained. Open-ended questions and the skills relevant to interviewing should be used, remembering to pay attention to the environment, including privacy (see Chapter 12). Examples of questions to ensure meaningful information is collected include: ‘How do you feel about the operation you are having?’, ‘What are you thinking about regarding your surgery?’ or ‘Tell me about any concerns you have about the surgery, or being in hospital’.

A useful strategy to explore potential issues and to allow clients to raise questions is to normalise the client’s fears and concerns by explaining that it is common for individuals to have certain concerns relating to their surgery. The client’s ability to share feelings depends on the rapport that has been developed between the client and the nurse, the nurse’s willingness to listen and be supportive and the ability to clarify misconceptions. If the client expresses feelings of powerlessness, the nurse should try to determine the reason. The medical diagnosis may generate apprehension of increased dependence and loss of physical or mental function. The thought of being ‘put to sleep’ under anaesthesia may create concern about loss of control. The nurse can ensure that clients understand their right to ask questions and to seek information. It may be difficult to assess a client’s feelings adequately when same-day surgery is scheduled, as the nurse usually has less time to develop a rapport with the client. In some outpatient surgical centres the nurse may visit a client in their home or speak on the telephone before surgery.

Preoperative anxiety occurs in most adult clients and has been linked to tachycardia, hypertension, arrhythmias and increased levels of pain (Wagner and others, 2006). It is, therefore, important to work with the client and those who support them to reduce anxiety prior to surgery.

BODY IMAGE

Surgical removal of any diseased body part often leaves permanent disfigurement, alteration in body function or concern over mutilation. Loss of certain body functions (e.g. with a colostomy or urostomy) compounds a client’s fears. Assessment of a client’s perceived body-image alterations is important. Sometimes surgery changes the physical or psychological aspects of a client’s sexuality. Excision of breast tissue, colostomy, ureterostomy, hysterectomy or prostatectomy may affect clients’ perceptions of their sexuality. Clients may have to refrain temporarily from sexual intercourse until they return to normal physical activity after some surgery, such as hernia repair or cataract extraction.

Clients should be encouraged to express their concerns about sexuality (see Chapter 24). The client facing even temporary sexual dysfunction requires understanding and support. Ideally, discussions about the client’s sexuality should be held with the client’s sexual partner so that they can gain a shared understanding of how to cope with limitations in sexual function.

COPING RESOURCES

It is important to ask the client about coping strategies and past stress management. If the client has had previous surgery, successful coping strategies can be determined and incorporated into the care plan if appropriate. Relaxation exercises can also be taught to help control anxiety (see Chapter 42).

The nurse should clarify who the client’s support persons are: family, significant others and/or friends. While many clients want someone else present when being provided with information and explanations, others prefer that their support persons are not involved in discussions. This is always individual and the client’s wishes must be respected. Support-person presence should be encouraged when feasible, especially for clients in the same-day surgery setting. Often a support person can become the client’s coach, offering valuable support during the postoperative period, when the client’s participation in care is vital.

CULTURE

Clients come from diverse backgrounds, ethnicity, cultures and religions. The way a client perceives their entire experience related to surgery is affected by their background. If cultural, ethnic and religious implications are not acknowledged and planned for, desired surgical outcomes may not be achieved. Therefore the acquisition of knowledge regarding cultural and ethnic groups helps the nurse to have a person-centred approach and individualise client care. Some examples of cultural differences that may influence pre- and post-operative care are summarised in Box 44-2.

BOX 44-2 CULTURAL DIFFERENCES THAT MAY INFLUENCE THE SURGICAL EXPERIENCE

AUSTRALIAN

Generally stoic when ill. Report of pain to nurse may be in general terms, such as ‘I am uncomfortable’. Under-treatment of pain is common. May have a basic lack of trust.

ARAB

Verbal consent has more meaning than written consent because it is based on trust. Must explain fully the need for written consent. Very expressive regarding pain; pain may cause intense fear. Prepare patient for painful procedures and develop a plan of care to prevent pain from occurring.

Although it is important to recognise and plan for cultural differences, it is also necessary to recognise that members of the same culture are individuals and may not hold the same beliefs.

Physical examination

A physical examination is conducted preoperatively, based on the client’s preoperative condition and the type of surgery being undertaken. Chapters 27 and 28 describe the techniques used in physical assessment. Assessment focuses on findings related to the client’s medical history and on the body systems that are likely to be affected by the surgery. It is important to establish a baseline of information and to identify any actual alterations or potential complications.

GENERAL SURVEY AND BASELINE VITAL SIGNS

The nurse observes the client’s general appearance, including their skin colour and moisture, facial expression, gait and height and weight. These are all important cues that may be indicators of underlying disease and an alteration in status and function. Weight is usually recorded to ascertain baseline data and may be required information for accurate medication dosages.

Preoperative assessment of vital signs provides important baseline data with which to compare alterations that occur during and after surgery (Chapter 28). Some institutions request that blood pressure be obtained from both arms for comparison; and, depending on the client’s history, standing and lying blood pressure may be required. Anxiety and fear commonly cause elevations in heart rate and blood pressure. Anaesthetic agents typically depress all vital functions. However, adverse drug reactions may include elevations in heart rate and blood pressure. As the effects of the anaesthesia diminish after surgery, the nurse closely monitors vital signs and compares findings with the preoperative baseline. Vital signs are considered in the discharge or transfer of the client from the post-anaesthetic care unit (PACU) back to the ward environment or to home.

Preoperative assessment of vital signs is also important to rule out fluid and electrolyte abnormalities before surgery commences (see Chapter 39). An elevated heart rate may result from a fluid volume deficit, potassium deficit or sodium excess. If the pulse is full and bounding, a fluid volume excess may be the cause. Cardiac dysrhythmias are commonly caused by electrolyte imbalances, especially potassium, magnesium and calcium.

An elevated body temperature before surgery is a cause for concern. If the client has an underlying infection, the surgeon may postpone surgery until the infection has been treated. An elevated body temperature increases the risk of fluid and electrolyte imbalance after surgery.

HEAD AND NECK

Assessment of oral mucous membranes reveals data about hydration status. A client who is dehydrated is at risk of developing serious fluid and electrolyte imbalances during surgery. Excess fluid within the circulatory system or failure of the heart to contract efficiently may lead to jugular vein distension and reveal a risk of cardiovascular complications during surgery. Inspection of the soft palate and nasal sinuses can reveal sinus drainage indicative of respiratory or sinus infection. Palpation for cervical lymph node enlargement may indicate the possibility of infection.

INTEGUMENT

It is important to carefully inspect the skin, paying particular attention to bony prominences, such as the heels, elbows, sacrum and scapula. During surgery, a client must lie in a fixed position, often for several hours, which makes them susceptible to pressure injuries (see Chapter 30), especially if the skin is thin and dry. An older person is often at high risk for an alteration in skin integrity related to positioning and sliding on the operating room table, causing shear and pressure. In addition, skin turgor is an indicator of hydration status.

THORAX AND LUNGS

Assessment of the client’s respiratory rate, breathing pattern and chest movement helps assess ventilatory capacity. Clients are encouraged to deep-breathe and cough postoperatively. A decline in ventilatory function may place the client at risk of respiratory complications. Auscultation of lung sounds will indicate whether there is pulmonary congestion or narrowing of airways. Existing atelectasis or moisture in the airways will be aggravated during surgery. Serious pulmonary congestion may cause postponement of the surgery. Certain anaesthetics can cause bronchospasm; thus if the nurse auscultates a wheeze preoperatively, the client is at risk of further airway narrowing during surgery and after extubation (removal of the endotracheal tube). Assessment for cyanosis and for clubbing of the fingers is included, as this may indicate lung disease and possible issues during and after surgery.

HEART AND VASCULAR SYSTEM

If the client has cardiac disease, the nurse assesses the character of the apical pulse. Anaesthetic agents, alterations in fluid and electrolyte balance, and stimulation from the surgical stress response can cause cardiac dysrhythmias. Depending on the type of surgery and the client’s past history, assessment of peripheral pulses, capillary refill time and the colour and temperature of extremities may be conducted. If peripheral pulses are not palpable, a Doppler ultrasound should be used for assessment of their presence and their position marked with a pen. Measurement of capillary refill and assessment of peripheral pulses are particularly important for clients having vascular surgery or for those who may have casts or constricting bandages applied to the extremities after surgery. Postoperative development of a weak or absent pulse in a client who had adequate circulation before surgery indicates impaired circulation.

ABDOMEN

The abdomen is assessed for size, shape and symmetry. If the client is having abdominal surgery, the nurse will be frequently assessing the abdominal-incision dressing site postoperatively and will compare with preoperative data. Abdominal distension may indicate postoperative alterations in GI function, or possible abdominal bleeding. Assessment of preoperative bowel sounds may be useful to use for postoperative comparison. If the surgery requires manipulation of the GI tract or if a general anaesthetic is used, normal peristalsis and bowel sounds will be absent or diminished for several days after surgery.

NEUROLOGICAL STATUS

Preoperative assessment of neurological status is imperative for all clients receiving general anaesthesia. Baseline assessment aids the assessment of the client when coming out of anaesthesia. During the health history and physical assessment, the nurse observes the client’s orientation, alertness and mood, noting whether the client answers questions appropriately and can recall recent and past events. A client who will have surgery for neurological disease (e.g. brain tumour or aneurysm) is likely to demonstrate an impaired level of consciousness or altered behaviour. Level of consciousness changes as a result of general anaesthesia. However, after the effects of anaesthesia resolve, the client should return to the preoperative level of responsiveness.

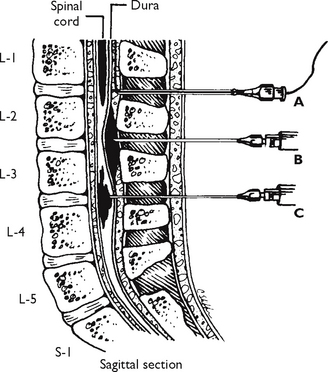

If the client is having a spinal anaesthesia, preoperative assessment of gross motor function and strength is important. Spinal anaesthesia causes temporary paralysis of the lower extremities (see Chapter 41). It is important to be aware of pre-existing weakness or impaired mobility of the lower extremities to avoid becoming alarmed when a client’s full motor function does not return as the spinal anaesthetic wears off.

DIAGNOSTIC SCREENING

Before a client has surgery, the surgeon may order diagnostic tests to screen for pre-existing abnormalities based on the client’s history and physical assessment (Table 44-4). For example, the client with a history of renal insufficiency may require a recent urea and creatinine level to determine preoperative renal function. Also, a haemoglobin (Hb) and haematocrit (Hct) assessment may be necessary, since clients with renal disease are often anaemic from decreased levels of erythropoietin. Tests are also determined by the procedure itself. Since blood loss frequently occurs with hip and knee replacements, a type and cross-match would be indicated preoperatively. If diagnostic tests reveal severe problems, the surgeon may cancel surgery until the condition stabilises.

TABLE 44-4 COMMON DIAGNOSTIC TESTS PERFORMED PREOPERATIVELY BASED ON CLIENT HISTORY

| HISTORY | TESTS |

|---|---|

| Hepatic disease | Prothrombin time/partial thromboplastin time (PT/PTT); liver enzymes, such as serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT); alkaline phosphatase |

| Medications: | |

| Diuretics | Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, electrolytes |

| Steroids | Electrolytes, glucose |

| Cardiovascular disease | Urea, creatinine, full blood count (FBC), chest X-ray, electrocardiogram (ECG) |

| Pulmonary disease | FBC, chest X-ray, ECG |

| Central nervous system disease | White blood cell (WBC) count, electrolytes, urea, creatinine, glucose and ECG |

The nurse is responsible for the preparation of clients for diagnostic studies. Depending on the setting, the nurse may also review diagnostic results as they become available and notify medical staff if clinically significant.

ADDITIONAL SCREENING TESTS

If a client is over the age of 40 years, has heart disease or respiratory issues, a chest X-ray (CXR) or an electrocardiogram (ECG) may be performed. The CXR examines the heart and lung fields. A female client requiring radiographical studies needs to be asked if there is a possibility that she is pregnant, since exposure to radiation may cause injury to a fetus. If the client is unsure, a pregnancy test (e.g. serum or urine beta-hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) levels) will be ordered. Some institutions routinely use lead aprons placed over the client’s abdomen. An ECG measures the heart’s electrical activity to determine whether the heart rate, rhythm and other factors are normal.

Depending on the type of surgery the client will undergo, there are several diagnostic tests for specific anatomical structures and physiological functions. Pulmonary function testing and occasionally arterial blood gas analysis may be performed on clients with pre-existing lung disease. Blood glucose levels are measured preoperatively on diabetic clients. If the client is likely to lose a large amount of blood during surgery, a blood specimen for type and cross-matching is taken to determine the client’s blood type and Rh factor. The surgeon usually designates the number of blood units to have available during surgery.

Autologous infusions reduce the risk of transfusion-related infections. These are an option for clients having elective surgery and who choose to donate their own blood several weeks before surgery. In addition, autotransfusion via the use of a cell-saver device in surgery may be possible if the surgeon is anticipating large blood loss (e.g. in open heart surgery).

• CRITICAL THINKING

Mark Fleet is a 35-year-old man who has just been admitted for an emergency appendectomy. On admission he reports severe pain (rated 7 on a scale of 0–10), is lying on his side with his knees drawn up to his abdomen and is moaning loudly. He is diaphoretic, nauseated and has recently vomited. He is very anxious and keeps asking if ‘my belly is going to explode’.

Outline how you would focus your assessment of Mark to ensure you obtain relevant and accurate data, given his presentation.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

The nurse clusters patterns of assessment data identified during assessment to identify relevant nursing diagnoses or problem statements for the surgical client (Box 44-3). This then allows the nurse to appropriately focus the nursing care. The client with pre-existing health problems is likely to have a variety of risk diagnoses (Box 44-4). For example, a client with pre-existing chronic bronchitis who has abnormal breath sounds and a productive cough will be at risk of ineffective airway clearance. The nature of the surgery and the client’s health status provide defining characteristics for a number of nursing diagnoses. For example, a client who undergoes a surgical procedure is at risk of developing infection at either the surgical site, the IV site or in the bloodstream (sepsis). A diagnosis of risk of infection will need to be addressed by nurses from admission to rehabilitation.

BOX 44-3 SAMPLE NURSING DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

| CLIENT FACING SURGERY | ||

|---|---|---|

| ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS (DATA) | NURSING DIAGNOSIS/PROBLEM STATEMENT |

| Fear related to knowledge deficit and previous surgical experience. | ||

Nursing diagnoses made preoperatively may also focus on the potential risks a client will face after surgery (e.g. risk for chest infection). Preventive care is essential so that the surgical client can be managed effectively and risk be reduced.

PLANNING

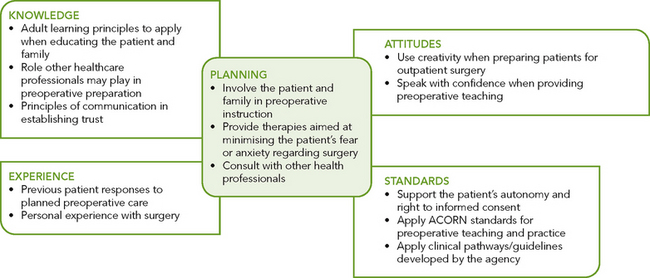

During planning the nurse again synthesises information from multiple sources (Figure 44-2). For example, knowledge of adult learning principles, coupled with the client’s unique needs, will ensure a well-designed individualised preoperative education plan. Critical thinking ensures that the client’s plan of care integrates all that the nurse knows about the individual, as well as key critical-thinking elements. Previous experience in caring for surgical clients assists the nurse to anticipate how to approach client care (e.g. complications to look for and methods to reduce anxiety). Evidence-based guidelines and professional standards are especially important to consider when the nurse develops a plan of care. The nurse should follow protocols for preoperative education such as guidelines provided by professional organisations, for example the Australian College of Operating Room Nurses (ACORN, 2010).

The nurse develops an individualised plan of care for each nursing diagnosis or problem statement (see Sample nursing care plan). The nurse and client set realistic expectations for care. Goals are to be individualised and realistic with measurable outcomes.

Successful care planning requires the involvement of the surgical client and family. The nurse provides the client and family/significant others with necessary information to help in decision making regarding care. Involving the client early when developing the surgical care plan minimises surgical risks and postoperative complications. A client informed about the surgical experience is likely to be less fearful and can prepare to participate in the postoperative recovery phase so that outcomes can be met. It is important to include the client and support people in developing the plan of care and establishing outcomes.

PREOPERATIVE CLIENT

ASSESSMENT*

Mr Molosky is 78 years of age and is scheduled to be admitted in 5 days for elective bowel resection. Anne Holloway, RN, is responsible for preparing Mr Molosky for surgery. During Anne’s initial discussion with Mr Molosky, she ascertains that Mr Molosky is alert and oriented. Mr Molosky wears glasses for reading and is able to hear Anne’s questions. Mr Molosky last had surgery over 25 years ago. He says to Anne, ‘It is my understanding that I will probably be in the hospital for quite a while.’ Anne clarifies that hospitalisation for surgery is shorter than what was expected 25 years ago. After further questioning, Anne learns that Mr Molosky has not received instruction on the surgical procedure and the care relating to effective postoperative recovery. Mr Molosky shows interest in Anne’s questions and asks what to expect following surgery.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS: Knowledge deficit regarding preoperative and postoperative care requirements.

PLANNING

| INTERVENTIONS | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Teaching: preoperative | It is beneficial to give the client written material and audiovisual material that they can listen to repeatedly if necessary. |

*Defining characteristics are shown in bold type.

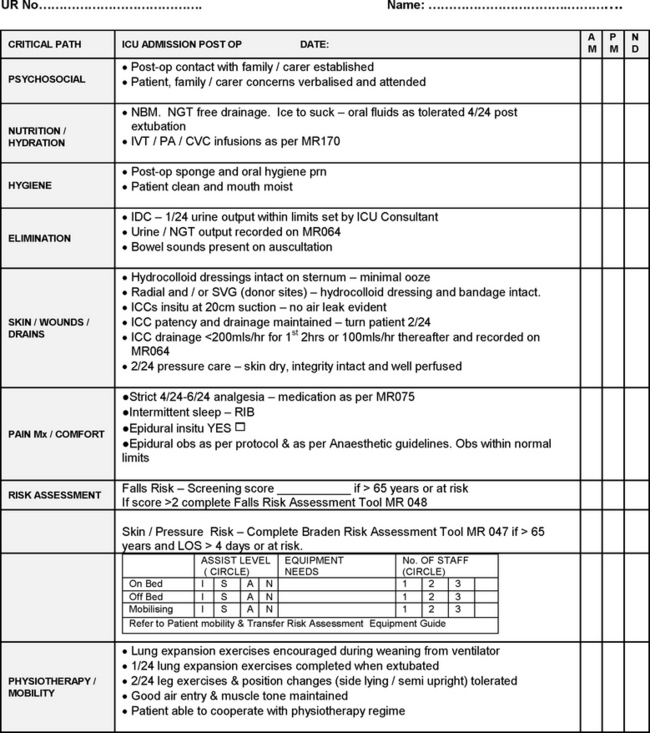

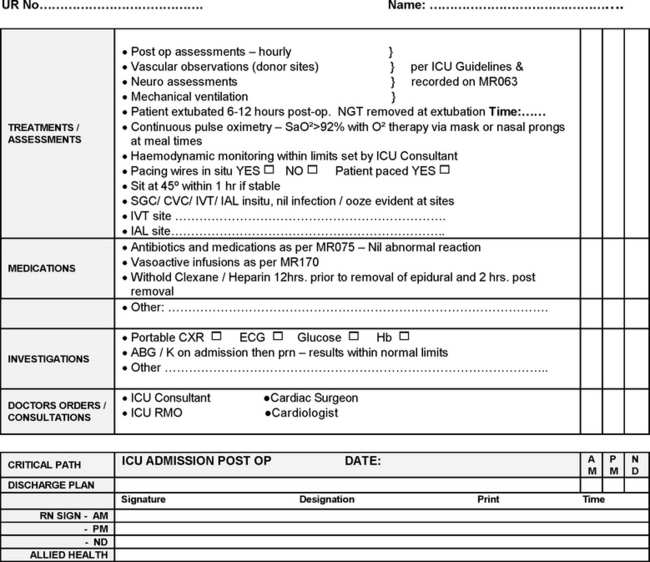

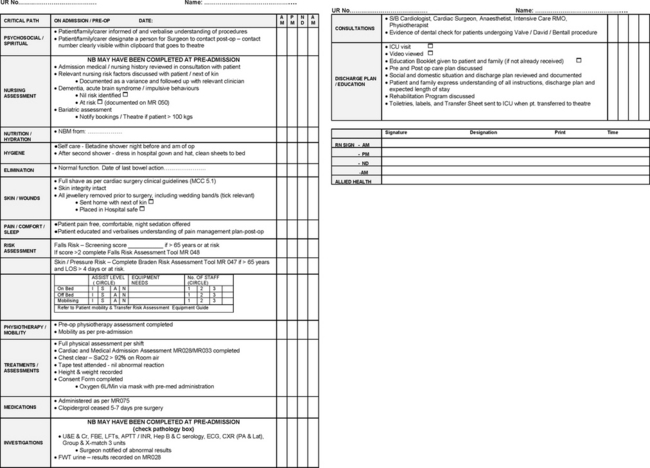

For same-day surgery clients and clients admitted the day of their scheduled surgery, preoperative planning occurs (ideally) days before admission to the hospital or surgical centre. Often, preoperative education begins in the doctor’s surgery, continues during the scheduled preadmission testing visit and is reinforced by the nurse on the day of admission. Preoperative information and instructions may include follow-up telephone calls, mailings from the clinic or hospital, or the use of videos or patient pathways (Figure 44-3). Preoperative instruction gives the client time to think about the surgical experience, make necessary physical preparations (e.g. altering diet or discontinuing medication use) and ask questions about postoperative procedures. Well-planned preoperative care ensures that the client is well informed and able to be an active participant during recovery. The family/significant others can also play an active supportive role.

FIGURE 44-3 Extract of pre-operative clinical pathway for cardiac surgery.

Courtesy Warringal Private and Ramsay Health Care, Melbourne, Victoria.

The preoperative care plan is individualised for the client; however, there are broad goals that are relevant to the majority of surgical clients:

• understanding physiological and psychological responses to surgery

• understanding reasons for postoperative care

• achieving emotional comfort and relaxation

• achieving a return of normal physiological function after surgery

• maintaining a normal fluid and electrolyte balance

IMPLEMENTATION

Preoperative nursing interventions provide the client with a complete understanding of the surgery and prepare the client physically and psychologically for surgical intervention.

Informed consent

An important responsibility when caring for a client before surgery is ensuring that client consent for the surgery has been obtained by the surgeon. The nurse should be aware of the requirements of a valid consent and of who may provide consent if the client is unable to do so because of an altered mental state, illness or emergency situation.

In Australia and New Zealand it is common risk-management practice that clients are expected to complete a written consent form prior to surgery. For the client’s consent to be valid, all the elements that constitute consent must be fulfilled (see Chapters 10 and 11. The signed consent form is evidence that consent has been given. The healthcare professional undertaking the procedure, usually the surgeon, is responsible for obtaining the client’s consent.

Ideally the consent form should be completed by the treating medical practitioner, or person responsible for the procedure, at the time the verbal discussion takes place. A client can revoke consent at any time. This can be done verbally or by writing on the consent form. There are also times when clients alter the written form. If this occurs, the treating medical practitioner needs to be informed before the surgery and the client should be asked to initial the alteration. Likewise, if the client asks specific questions regarding the procedure when the nurse is admitting or preparing the client for surgery, it is important that the nurse practises within their scope of practice. The nurse should inform the treating medical officer of the client’s specific concerns and document this in the client’s file.

There is no clear life span of a written consent form, so many agencies will have policies that stipulate an acceptable timeframe (e.g. 30 days). The older the form, the greater the potential risk that the client’s condition or cognitive status has changed. If a consent form is used, it is filed in the client’s record; the record accompanies the client to surgery.

Although healthcare professionals can witness a client’s signature, the precise role of the witness remains unclear. In general terms the witness’s signature merely attests that the witness actually saw the client sign the form. It is policy in some agencies for the witness to write ‘witness to signature’ next to their signature, if not already documented on the form. However, in the healthcare context, questions can also be raised in relation to the information given and the specifics of the discussion between the parties. For this reason, it is preferred that the person explaining the procedure, the medical practitioner, signs as the witness.

Preoperative client education

Preoperative education concerning a client’s expected postoperative experience, provided in a systematic and structured format underpinned by teaching and learning principles, can have a positive influence on the client’s recovery. The ACORN (2010) asserts that the competence of the nurse conducting the preoperative assessment and providing education can influence the client’s surgical outcome. Interestingly, a Cochrane systematic review (McDonald and others, 2008) that examined whether preoperative education for hip or knee replacement surgery improved patient outcomes (i.e. pain, anxiety, mobility, incidence of DVT, length of stay) found that education may decrease preoperative anxiety, yet there was little evidence that preoperative education improves postoperative outcomes in relation to length of hospital stay, patient functioning and pain in this group. For patients who need support or have limitations to movement, individually focused education may improve their recovery.

Structured preoperative education can influence postoperative factors such as the following.

• Lung function. Explaining and demonstrating the technique of deep-breathing and coughing while the client is pain-free helps the client learn and perform these exercises postoperatively.

• Physical functional capacity. Teaching feet and leg exercises helps to reduce the incidence of postoperative DVT. These exercises and teaching turning assist to improve the client’s ability to walk and resume activities of daily living.

• Sense of wellbeing. Clients who are adequately prepared for surgery often experience less anxiety and report a greater sense of psychological wellbeing.

• Pain control. Clients who are involved in learning about pain and ways to relieve it may be less anxious about pain and be more inclined to ask for what they need.

For preoperative education to be effective, it is important for it to be planned so that the appropriate information is covered, but also for it to have a person-centred approach. It is key for the education to be individualised and tailored to the needs of the client. Whereas some clients will want only minimal information and may experience increased levels of anxiety with too much detail, others will want very detailed and involved information. This is highly individual and, as such, the nurse needs to be able to adequately assess the needs of the client, their existing knowledge in relation to the surgery and identify the specific knowledge gaps.

Detailed discussion and demonstration of postoperative exercises is vital to reduce the risks associated with postoperative recovery. If the client understands why these exercises are important to postoperative recovery and knows how to perform them correctly, the recovery period will be less complicated. However, despite the education provided to clients, client retention of information following discharge is often poor. To counteract this, education before admission that is reinforced during the hospital stay and after discharge is important. Frequently, day-surgery centres conduct follow-up telephone interviews with clients after they have been discharged. One of the reasons for this is to ascertain any knowledge gaps and to reinforce previous education provided regarding postoperative care.

Including the client’s family, significant others and/or carer in the perioperative preparation is advised, and the benefits of this should be discussed with the client. For example, when the client returns from surgery, a family member may take on the role of ‘coach’ in relation to the postoperative exercises. If anxious relatives do not understand routine postoperative events, it is likely that their anxiety will heighten the client’s fears and concerns. To minimise anxiety and misunderstanding, preoperative preparation of carers, family and significant others should occur before surgery. It is optimal to also include written material. Many hospitals will also provide video information aimed at both the client and the key people who support them.

The nurse should provide clients with information about sensations typically experienced after surgery. Preparatory information helps clients anticipate the steps of a procedure and thus helps them form realistic images of the surgical experience. When events occur as predicted, clients are better able to cope with the experiences. Sensations that the nurse may cover include the expected pain at the surgical site, tightness of dressings, dryness of the mouth or the sensation of a sore throat resulting from an endotracheal tube.

Anxiety and fear are barriers to learning, and both emotions are heightened as surgery approaches. The client’s readiness and ability to learn must be assessed. If the client is capable of and receptive to learning, the nurse presents information in a logical sequence, beginning with preoperative events and proceeding to postoperative routines. If possible, the family or significant others should be present during teaching.

The following can be used to guide preoperative discussions and facilitate demonstration of client understanding of the surgical experience.

CLIENT CITES REASONS FOR PREOPERATIVE INSTRUCTIONS AND EXERCISES

Given a rationale for preoperative and postoperative procedures, the client is better prepared to participate in care. Every preoperative education program includes explanation and demonstration of postoperative exercises: diaphragmatic breathing, incentive spirometry, positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy, coughing, turning and leg exercises. These exercises are designed to prevent postoperative complications (Skill 44-1).

SKILL 44-1 Demonstrating postoperative exercises

DELEGATION CONSIDERATIONS

This task requires the problem-solving and knowledge-application skills of a registered nurse. For this reason, delegation of this task to nurse assistants is inappropriate. The registered nurse can teach assistants to encourage patients to practise exercises regularly following instruction.

EQUIPMENT

| STEPS | RATIONALE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| General anaesthesia predisposes patient to respiratory problems because lungs are not fully inflated during surgery; cough reflex is suppressed, so secretions collect within airway passages. After surgery, patient may have reduced lung volume and require greater efforts to cough and deep-breathe; inadequate lung expansion can lead to atelectasis and pneumonia. Patient is at greater risk of developing respiratory complications if other chronic lung conditions are present. Smoking damages ciliary clearance and increases mucus secretion. Reduced haemoglobin level can lead to inadequate oxygenation. | |||

| Reveals maximum potential for chest expansion and ability to cough forcefully; serves as baseline to measure ability to perform exercises after surgery. | |||

|

3. Assess risk for postoperative thrombus formation (see Figure 44-4). Observe for calf pain, redness, warmth, swelling or vein distension. |

General anaesthesia and immobilisation results in decreased muscular contraction in lower extremities, which promotes venous stasis. | ||

| Information allows patient to attend and can motivate learning. People tend to learn new skills when benefits can be gained. | |||

| A. Diaphragmatic breathing | |||

| Upright position facilitates diaphragmatic excursion. | |||

| Allows patient to observe breathing exercise. | |||

| Position of hands allows patient to feel movement of chest and abdomen as diaphragm descends and lungs expand. | |||

| Taking slow, deep breaths prevents panting or hyperventilation. Inhaling through nose warms, humidifies and filters air. | |||

| Explanation and demonstration focus on normal ventilatory movement of chest wall. Patient develops understanding of how diaphragmatic breathing feels. | |||

| Using auxiliary chest and shoulder muscles increases useless energy expenditure. | |||

| Allows for gradual expulsion of all air. | |||

| Allows patient to observe slow, rhythmic breathing pattern. | |||

| Repetition of exercise reinforces learning. Regular deep breathing prevents postoperative complications. | |||

| B. Incentive spirometry | |||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | |||

| Promotes optimal lung expansion during respiratory manoeuvre. | |||

| Establishes volume level necessary for lung expansion. | |||

| Demonstration is reliable technique for teaching psychomotor skill and enables patient to ask questions. | |||

| Maintains maximal inspiration and reduces risk of progressive collapse of individual alveoli. Slow breath prevents or minimises pain from sudden pressure changes in chest. | |||

| Prevents hyperventilation and fatigue. | |||

| Ensures correct use of spirometer. | |||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | |||

| C. Positive expiratory pressure therapy and ‘huff’ coughing | |||

| Reduces transmission of microorganisms. | |||

| Promotes optimal lung expansion and expectoration of secretions. | |||

| Ensures that all breathing is done through the mouth and that the device is used properly. | |||

| Promotes lung expansion before coughing. | |||

| ‘Huff’ coughing, or forced expiratory technique, promotes bronchial hygiene by increased expectoration of secretions. | |||

| D. Controlled coughing | |||

| Position facilitates diaphragm excursion and enhances thorax expansion. | |||

| Deep breaths expand lungs fully so that air moves behind mucus and facilitates effects of coughing. | |||

| Consecutive coughs help remove mucus more effectively and completely than one forceful cough. | |||

| Clearing throat does not remove mucus from deep in airways. | |||

|

(5)If surgical incision will be abdominal or thoracic, teach patient to place one hand over incisional area and other hand on top of first. During breathing and coughing exercises, patient presses gently against incisional area to splint or support it. Pillow over incision is optional (see illustration). |

Surgical incision cuts through muscles, tissues and nerve endings. Deep-breathing and coughing exercises place additional stress on suture line and cause discomfort. Splinting incision with hands provides firm support and reduces incisional pulling. (Some patients prefer to have pillow to place over incision.) | ||

| From Lewis S and others 2011 Medical–surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinicaI problems, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby. | |||

| Value of deep coughing with splinting is stressed to effectively expectorate secretions with minimal discomfort. | |||

| Sputum consistency, amount and colour changes may indicate presence of pulmonary complication, such as pneumonia. | |||

| E. Turning | |||

| Positioning begins on right side of bed so that turning to left side will not cause patient to roll towards bed’s edge. | |||

| Supports and minimises pulling on suture line during turning. | |||

| Straight leg stabilises patient’s position. Flexed right leg shifts weight for easier turning. | |||

| Pulling towards side rail reduces effort needed for turning. | |||

| Reduces risk of vascular and pulmonary complications. | |||

| F. Leg exercises | |||

| Provides normal anatomical position of lower extremities. | |||

| Leg exercises maintain joint mobility and promote venous return to prevent thrombi. | |||

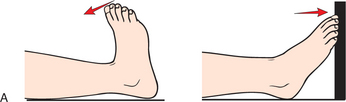

| Stretches and contracts gastrocnemius muscles. | |||

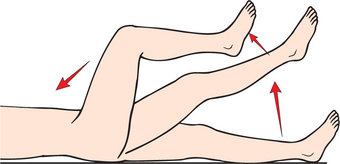

| Promotes contraction and relaxation of quadriceps muscles. | |||

| Contracts muscles of upper legs and maintains knee mobility. | |||

| From Lewis S and others 2011 Medical–surgical nursing: assessment and management of clinical problems, ed 8. St Louis, Mosby. | |||

| Repetition of sequence reinforces learning. Establishes routine for exercises that develops habit for performance. Sequence of exercises should be leg exercises, turning, breathing, incentive spirometry and coughing. | |||

| Ensures that patient has learned correct technique. | |||

| Documents patient’s education and provides data for instructional follow-up. | |||

When a client is under general anaesthesia, the lungs do not ventilate fully. After surgery the client has a reduced lung volume and needs greater effort to breathe. Diaphragmatic breathing improves lung expansion and oxygen delivery without using excess energy. The client learns to use the diaphragm during deep-breathing to take slow, deep, relaxed breaths. The goal is to inhale slowly and deeply through the nose, hold the breath for a few seconds and then exhale slowly and completely through the mouth. Eventually the client’s lung volume improves. Deep-breathing also helps clear out anaesthetic gases remaining in the airways. To facilitate deep-breathing, the client may use an incentive spirometer, which encourages effective deep-breathing through sustained maximal inspiration (see Chapter 40).