DISORDERS OF THE HEPATOBILIARY SYSTEM AND PANCREAS

The accessory organs of digestion (liver, gallbladder, pancreas) secrete substances necessary for digestion and, in the case of the liver, carry out additional metabolic functions needed for homeostasis of all body systems. Disorders of these organs are usually caused by inflammatory disease, obstruction of ducts and tumours. It is somewhat unfortunate that the liver, gallbladder and pancreas are known as ‘accessory’ organs, as the word accessory may give the incorrect impression that these organs are of low importance; it simply means that their secretions empty into the gastrointestinal system. The critical importance of these organs is shown by the serious illnesses and mortality that accompanies their dysfunction.

Hepatic disorders

The main type of injury that occurs in the liver involves damage to the hepatocytes by cirrhosis (inflammation and fibrosis), which is strongly associated with alcohol consumption. Viral hepatitis also severely impairs hepatocyte function and may increase the likelihood of cancer development. Blockages of the blood supply into the hepatocytes, or of the bile drainage away from hepatocytes, can result in a range of clinical manifestations and liver conditions.

Inflammatory processes of the liver

Alcoholic liver disease

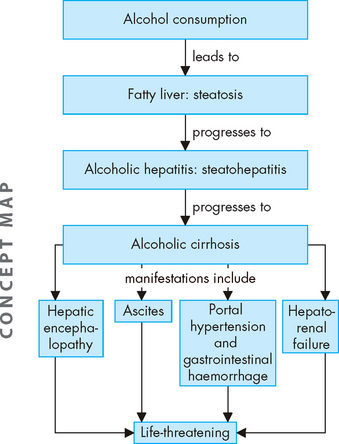

Alcohol consumption can cause liver disease — the most mild form is fatty liver, progressing to alcoholic hepatitis and eventually alcoholic cirrhosis, with irreversible liver damage. The long-term amount and duration of alcohol consumption are related to the extent of liver damage, so those who have consumed higher volumes of alcohol are at greater risk of developing cirrhosis. Although there is a misconception that some drinks are ‘less harmful’ than others, abuse of any type of alcoholic beverage can cause cirrhosis. A standard drink is defined as having 10 grams of alcohol, and different types of drinks may equate to more than a standard drink in what may appear to be a normal serving size.

Some useful insights into the detrimental effects of alcohol on the Australian population can be derived from statistics of people seeking treatment for their alcohol consumption — the number of people seeking treatment for alcohol consumption is higher that that for cannabis and opioids (alcohol is the main drug in 42% of cases).121 In fact, the number of those seeking treatment for alcohol use has been rising over recent years. Alcohol is the principal drug used by the over-60 age group, and this age group accounts for 84% of people requiring treatment.121 Alcohol use is of increased concern for older adults: not only can it increase the risk of health complications, but it can also interact with a large number of medications, as well as increasing the risk of falls, injuries and suicides in this age group.122 Regional data indicate that two-thirds of treatments in remote regions and 80% in very remote regions are due to alcohol use, with almost 12% of patients being Indigenous Australians.121 In New Zealand, the Maori population has four times the number of alcohol-related deaths than non-Maoris.123 Together, these data show that alcohol use is a significant concern for our communities.

The lifetime risk of mortality from chronic disease due to alcohol consumption rises when more than 2 standard drinks per day are consumed, for both men and women (see Table 27-8 for guidelines on alcohol consumption). However, as the amount of alcohol consumed increases, the risks become even greater for women than for men.124 Some reasons why women are more susceptible to higher amounts of alcohol than men include both the smaller liver size and the lower proportion of lean tissue in women compared with men. It must also be remembered that individuals have differences in alcohol metabolism.122

Table 27-8 GUIDELINES FOR ALCOHOL CONSUMPTION

Source: Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009; and Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand. Policy Statement 6: upper limits for responsible drinking. 2002. Available at www.alcohol.org, accessed July 2009.

Each year, more than 3000 deaths in Australia and 1000 deaths in New Zealand are related to alcohol consumption.123,125 Of course, alcohol consumption can also be beneficial for health — for example, lowering the risk of some cardiovascular conditions. It is estimated that just over 2000 deaths in Australia and 980 in New Zealand are prevented by consuming alcohol.123,125 However, it needs emphasising that such benefits are achieved when alcohol consumption is relatively low and that an improvement in the risk of these cardiovascular conditions could be achieved by exercise or dietary modifications.122,123 Moreover, the benefits of drinking alcohol only begin to appear from middle age; drinking prior to this does not provide health benefits.123 Finally, the number of actual deaths still outweighs the number of deaths prevented in both countries.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Alcohol is absorbed into the bloodstream and transported directly to the liver through the hepatic portal vein. The liver can metabolise the alcohol from approximately 1 standard drink per hour.122 Alcohol is metabolised to acetaldehyde, which is actually a toxic substance — excessive amounts significantly alter hepatocyte function. Because the liver has such an important role in the metabolism of a wide variety of substances (a few thousand!), many body processes are affected by altered hepatocyte function. Normal liver functions such as enzyme and protein production may be decreased, and hormone and ammonia degradation are diminished. Acetaldehyde also inhibits the export of proteins from the liver, alters the metabolism of vitamins and minerals, and induces malnutrition.126 Cellular damage initiates an inflammatory response that, along with necrosis (cell damage), results in excessive collagen formation. Fibrosis and scarring alter the structure of the liver and obstruct biliary and vascular channels.127

Fatty liver (steatosis) is the mildest form of alcoholic liver disease. It can be caused by relatively small amounts of alcohol, may be asymptomatic and is reversible with the cessation of drinking.128 However, alcoholic steatosis is an important risk factor for the development of fibrosis and therefore abstinence from alcohol is fundamental for patients to limit worsening of their condition.129

Alcoholic hepatitis (steatohepatitis) is an intermediate stage of alcoholic liver disease. It is characterised by inflammation, degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes and infiltration of white blood cells (polymorphonuclear leucocytes and lymphocytes). The injured hepatocytes begin undergoing the onset of fibrosis. The mechanism of hepatocyte injury is not clearly understood, but immunological factors and inflammatory mediators are involved. Serum IgA (immunoglobulin A) is often elevated in individuals with alcoholic hepatitis, and liver antigens and antibodies have been identified in those with progressive alcoholic liver disease. The inflammation and necrosis caused by alcoholic hepatitis stimulate the irreversible fibrosis characteristic of the cirrhotic stage of disease — this means that some changes of the liver cannot be reversed, even if alcohol consumption is ceased.

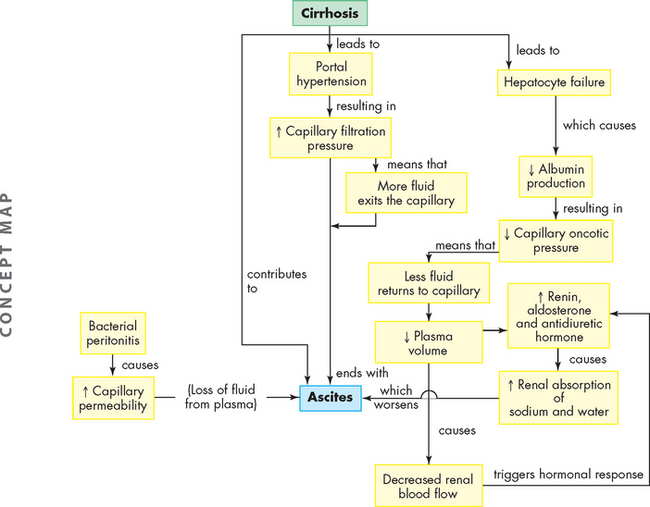

Cirrhosis is an irreversible inflammatory disorder that disrupts liver structure and function and is a leading cause of death. It is characterised by chronic inflammation and results in fibrosis. Disorganisation of hepatic tissues is caused by diffuse fibrosis and regeneration of tissue between fibrous bands that give the liver a cobbly appearance. The liver may be larger or smaller than normal and usually it is firm when palpated. Cirrhosis develops slowly over a period of years. While cirrhosis may be due to a number of causes, the main cause of cirrhosis of the liver is alcohol consumption.122 Alcoholic cirrhosis is caused by the toxic effects of alcohol on the liver. It progresses with fatty infiltration, fibrosis and cirrhosis. Fat deposition (deposition of triglycerides) occurs within the liver, and lipids mobilised from adipose tissue or dietary fat intake may contribute to fat accumulation. Cessation of alcohol intake reverses the fatty accumulation, but fibrosis and liver damage are irreversible. Other changes include immunological alterations and inflammation.

In addition to the effects on the liver, long-term alcohol consumption has many other effects on health, as summarised in Table 27-9. It is preferable to consume alcohol with food, as proposed by a recent modification to the New Zealand alcohol consumption guidelines,130 as this minimises the effects directly on the stomach, as well as slowing the rate of alcohol absorption into the bloodstream.

Table 27-9 LONG-TERM EFFECTS OF ALCOHOL ON HEALTH

Source: Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009; and Mann J, Truswell A. Essentials of human nutrition. 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Malnutrition can add to the risk of cirrhosis in alcohol abusers. Malnutrition may occur because those who drink large amounts of alcohol may skip meals (as they are drinking alcohol instead). Also, the alcohol that is being consumed does not supply any beneficial nutrients to the diet and is described as being ‘empty calories’.131 Malnutrition impairs liver function and can contribute to the development of cirrhosis.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Fatty infiltration causes no specific symptoms or abnormal liver function test results. The liver is usually enlarged and the individual has a history of continuous alcohol intake during the previous weeks or months. Anorexia, nausea, jaundice and oedema develop with advanced fatty infiltration or the onset of alcoholic hepatitis.

The clinical manifestations of alcoholic liver disease can be mild or severe. Nonspecific symptoms include fatigue, weight loss and anorexia. Toxic effects of alcohol can also cause testicular atrophy, reduced libido and decreased fertility in men. Manifestations of acute illness include nausea, anorexia, fever, abdominal pain and jaundice (yellow colour due to build-up of bilirubin). Cirrhosis is a multiple-system disease and causes hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), gastrointestinal haemorrhage, portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy and oesophageal varices. These are described individually in ‘Clinical manifestations of hepatobiliary alterations’ below. Anaemia results from blood loss, poor nutrition and splenomegaly (enlarged spleen). The presence of numerous and severe manifestations increases the risk of death (see Figure 27-27).

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

The diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis is based on the individual’s history and clinical manifestations. The results of blood tests are abnormal, with elevated serum enzymes and bilirubin (a waste product metabolised by the liver), decreased serum albumin (a plasma protein produced by the liver) and prolonged prothrombin time (as the liver cannot produce sufficient quantities of clotting factors, the time for blood to clot is extended). Liver biopsy can confirm the diagnosis of cirrhosis, but biopsy is not necessary if clinical manifestations of cirrhosis are evident.

There is no specific treatment for alcoholic cirrhosis. Management of complications, such as ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding and encephalopathy, is essential, along with a nutritious diet. Cessation of drinking is also essential and slows the progression of liver damage, improves clinical symptoms and prolongs life. Individuals with severe symptoms are treated with corticosteroids and other drugs, including antioxidants and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibition. Liver transplantation can be successful for treatment of end-stage liver disease.

Viral hepatitis

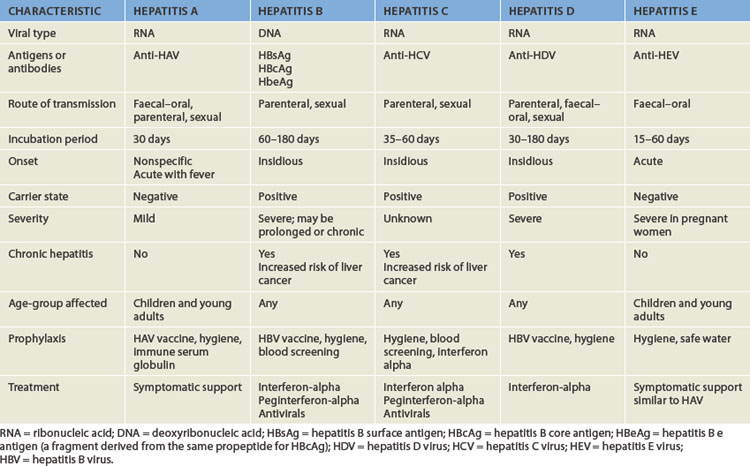

Viral hepatitis is a relatively common systemic disease that primarily affects the liver. Five strains of viruses cause different types of hepatitis: hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, hepatitis D and hepatitis E. These five viruses can cause acute hepatitis and types B and C also cause chronic liver disease, hepatic cancer and liver failure.132 The virus can be carried for years, usually without significant liver damage. Characteristics of the different types of viruses that cause hepatitis are presented in Table 27-10.

Hepatitis A appears to be on the decline in Australia.133 An effective vaccine became available in Australia in the 1990s;133 this is recommended for those travelling to countries where hepatitis A is endemic, as well as for Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders, who are at higher risk.134 The vaccine is not currently on the New Zealand immunisation register. The main route of transmission of this virus is via the faecal–oral route.133 Approximately 20–30% of reported cases occur in children,135 particularly children before school age. Outbreaks tend to occur in day-care centres, with the presence of large numbers of children who are not toilet-trained and staff members who may practise poor hand-washing techniques.136

The prevalence of hepatitis B is estimated at 90,000–160,000 in Australia and 67,000 in New Zealand.137,138 Approximately 50% of those affected in Australia were born in Eastern Asia and some of those would have been infected prior to emigrating.137 Also, most children currently in Australia with hepatitis B were born overseas.139 This virus is transmitted by direct contact with blood and body fluids; because it is present in saliva, it can easily be transmitted by children. An effective vaccine is now on the childhood immunisation registers for Australia and New Zealand (see Tables 14-7 and 14-8). Infants of mothers who are chronic hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers, children with haemophilia who receive frequent blood transfusions and children who live in institutions for those with mental disabilities are all at risk for hepatitis B infection.

Hepatitis C is in epidemic proportions in Australia: an estimated 260,000–300,000 Australians have this illness.140 The main route of transmission of this virus is by injecting drugs,140,141 and most children with hepatitis C were born of mothers who have a history of injecting drugs.139 Although there was a shortage of heroin supply in Australia in late 2000 and there has been a decrease in the number of injecting drug users in Australia,142 there are still almost 10,000 people newly infected by this virus each year.142,143 Hepatitis C can also be transmitted by blood transfusions. In Australia, the rates of infection in Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders are three to six times higher for hepatitis A, B and C than in the non-Indigenous population.134,144

Hepatitis D is mainly transmitted by blood products and intravenous drug use. Hepatitis D is caused by an incomplete virus, which requires simultaneous infection with hepatitis B; therefore, vaccination against hepatitis B will protect against hepatitis B and D.

The rate of infection of hepatitis E is rare in developed countries such as Australia and New Zealand.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

All five types of viral hepatitis can cause acute jaundice. The pathological lesions of hepatitis are similar to those caused by other viral infections. Hepatic cell necrosis, scarring (with chronic disease) and inflammatory processes occur with varying severity. The inflammatory process can damage and obstruct bile canaliculi, leading to obstructive jaundice. Damage tends to be most severe in cases of hepatitis B and C.

Co-infection of hepatitis B virus with hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) occur as these viruses share the same route of transmission (direct contact of body fluids such as sharing intravenous needles and sexual transmission). Progression of liver disease is more rapid in these cases.145

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The spectrum of manifestations ranges from absence of symptoms to acute liver failure, with rapid onset of liver failure and coma. Acute viral hepatitis causes abnormal liver function test results. The serum AST (aspartate transaminase) and ALT (alanine transaminase) are elevated but not consistent with the extent of cellular damage. The clinical course of hepatitis usually consists of three phases:

Acute liver failure is a clinical syndrome resulting in severe impairment or necrosis of liver cells and potential liver failure. The disorder rarely occurs with hepatitis A, but is a common complication associated with hepatitis B and C infection. In particular, those with compromised immune systems such as children and those with other illness are more likely to progress to acute liver failure. Toxic reactions to drugs and congenital metabolic disorders can also cause acute liver failure.

Acute liver failure is characterised by massive hepatic necrosis and causes severe encephalopathy, manifested as altered motor functions, confusion, stupor and coma. It can also include intestinal bleeding, cardiorespiratory insufficiency and renal failure. The death of hepatocytes may be caused by viral or immunological damage. Acute liver failure usually develops within 6–8 weeks after the initial symptoms of viral hepatitis (or metabolic liver disorder). Anorexia, vomiting, abdominal pain and progressive jaundice are initial signs, followed by ascites and gastrointestinal bleeding. Liver function tests show elevations of serum bilirubin, AST and ALT, and blood ammonia (a substance from protein metabolism that is normally removed by the liver). Prothrombin time is prolonged, as the liver is unable to produce adequate levels of blood-clotting factors. Renal failure and pulmonary distress can occur.146

Chronic active hepatitis is the persistence of clinical manifestations and liver inflammation after acute hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hepatitis D — the patient does not undergo the recovery phase. In chronic hepatitis, liver function tests remain abnormal for longer than 6 months and hepatitis B surface antigen persists. Chronic, active hepatitis B is a predisposition to cirrhosis and primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatitis C infection also has a substantial role in hepatocellular carcinoma in Australia and New Zealand.147 Extrahepatic manifestations, including arthralgias (joint pain), fatigue, neurological and renal symptoms, occur in some individuals.148

Hepatitis B and C viruses are the main causes of chronic hepatitis in children. Manifestations of chronic hepatitis include malaise, anorexia, fever, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver), oedema and transient joint pain. Serum ALT and bilirubin levels are elevated. There may be evidence of impairment of the functions of the liver in producing substances, such as prolonged prothrombin time and hypoalbuminaemia.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

The diagnostic tests for viral hepatitis depend on whether antigens or antibodies are present (see Table 27-10). The most specific diagnostic test for viral hepatitis is a blood test for specific hepatitis virus antigens (HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen). Diagnosis of type A, type C and type D hepatitis is based on the presence of antibodies for each viral type. Liver function tests, including liver enzyme levels, are sensitive for liver cell injury and can also indicate other viral liver diseases, drug toxicity or alcoholic hepatitis.

There is currently a screening program for hepatitis B in New Zealand for those who are at high-risk. Also, people with chronic hepatitis B infection undergo monitoring for liver cancer.149 Groups of health professionals in Australia are undertaking research towards establishing a national hepatitis B management program.

There is no specific treatment for acute viral hepatitis. For most individuals the disease is self-limiting with full recovery. Physical activity may be restricted. A low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet is beneficial if bile flow is obstructed, as fats cannot be digested without adequate levels of bile. For chronic hepatitis, treatment is directed at suppressing viral replication before irreversible liver cell damage occurs. Antiviral therapies include interferon-alpha and specific antiviral agents. Cyclic and combination therapy may prevent drug resistance and new agents are being developed.150

Hepatitis

Chronic hepatitis B virus and C virus infections affect millions of individuals worldwide, and diseases can progress to cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. Immunotherapy with interferon-alpha has been the standard treatment with about 50% response rate. Combination therapy with interferon and nucleoside analogues (i.e. lamivudine, adefovir and tenofovir) for hepatitis B virus and interferon with ribavirin for hepatitis C virus have been more effective in controlling viral replication than monotherapy, particularly for non-responders. Trials with pegylated interferons (peginterferon combined with ribavirin) are demonstrating superior response for hepatitis C, and new antivirals are being evaluated for resistant viral strains (pegylation of the interferon molecule increases its size, slows absorption and lowers the rate of clearance from the plasma, thus increasing the duration of biological activity). Australian data indicate that it may be more cost-effective to give antiviral medications than to undergo cancer screening.

Source: Farrell GC, Teoh NC. Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a new era of disease control. Intern Med J 2006; 36(2):100–113; Forton D, Karayiannis P. Established and emerging therapies for the treatment of viral hepatitis, Dig Dis 2006; 24(1–2):160–173; Robotin MC et al. Antiviral therapy for hepatitis B-related liver cancer prevention is more cost-effective than cancer screening. J Hepatol 2009; 50: 990–998.

After ingestion and gastrointestinal uptake, hepatitis A replicates in the liver and is secreted into the bile. To prevent transmission of hepatitis A, hand-washing and the use of gloves for disposing of bedpans and faecal matter are imperative. It may be shed in the faeces for up to 3 months after the onset of symptoms. The administration of immune globulin before exposure or early in the incubation period can prevent hepatitis A and hepatitis B. Vaccines are available to protect against hepatitis A and B infections, with the hepatitis B vaccine protecting against hepatitis D too. Because co-infection of hepatitis is of concern, patients with hepatitis C should be offered vaccines for hepatitis A and B.151 Prophylaxis is recommended for healthcare workers and others who are at risk for contact with infected body fluids, particularly children.

Treatment of acute liver failure is supportive. The hepatic necrosis is irreversible and 60–90% of affected children die. Liver transplantation may be lifesaving and should be considered early. Survivors usually do not develop cirrhosis or chronic liver disease. Diagnosis of chronic hepatitis is based on the clinical manifestations and liver biopsy. Chronic infections from hepatitis B and C are the most common indications for liver transplant in Australia.139 Most of the morbidity and mortality associated with chronic hepatitis B infection results from liver cirrhosis and cancer.152

The cost of treatment is expensive and drugs are sometimes poorly tolerated. Viral resistance limits drug use and advances are continuing to be made in the development of new drugs and hepatoprotective agents. With progression to end-stage liver disease, transplantation becomes the only option. Aggressive vaccination for the prevention of hepatitis is needed. Approximately 75% of patients with hepatitis C will progress to chronic infection.151

Hepatic cancer

Cancer of the liver usually develops secondary to metastatic spread from a primary site elsewhere in the body — in fact, the liver is one of the most common sites of cancer metastasis. Approximately 80% of cases of primary liver cancer are due to chronic hepatitis B and C infection.153 Primary liver cancer is rare before the age of 40 years and is most common during the sixth decade (see the box ‘Risk factors: primary liver cancer’). The rates of primary liver cancer in Australia are rising.153 Chronic hepatitis B and C, cirrhosis and dietary exposure to fungal aflatoxin are significant risk factors.154 More than 1000 Australians were diagnosed with liver cancer in 2005 (approximately 1.1% of the incidence of cancer), with almost as many dying from this cancer in the same year.1

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Primary carcinomas of the liver are hepatocellular or cholangiocellular. Hepatocellular carcinoma (hepatocarcinoma) develops in the hepatocytes, whereas cholangiocellular carcinoma (cholangiocarcinoma) develops in the bile ducts. Hepatocellular carcinoma can be nodular (multiple, discrete nodules), massive (a large tumour mass) or diffuse (small nodules distributed throughout most of the liver). It is closely associated with cirrhosis from chronic hepatitis. Because carcinoma of the liver invades the hepatic and portal veins, it often spreads to the heart and lungs (which are immediately downstream from the liver in terms of blood flow). Other sites of metastases are the brain, kidneys and spleen.

Cholangiocellular carcinoma can occur anywhere along the bile duct and extend directly into the liver, usually as a solitary lesion. It is difficult to distinguish an invasion of cholangiocellular carcinoma from a metastatic adenocarcinoma, except by neoplastic changes found in nearby ducts.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The clinical presentation of liver cancer in adults is characterised by vague abdominal symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, fullness, pressure and dull ache in the right hypochondrium (the right upper quadrant of the abdomen). Manifestations of hepatocellular carcinoma can occur slowly or abruptly. In individuals with cirrhosis, deepening jaundice or abrupt lack of appetite is a sign of hepatocellular carcinoma. Obstruction by the tumour can cause sudden worsening of portal hypertension and development of ascites. As the tumour enlarges, it causes pain. Cholangiocellular carcinoma more commonly presents insidiously as pain, loss of appetite, weight loss and gradual onset of jaundice. Some carcinomas of the liver rupture spontaneously, causing haemorrhage. Others are discovered accidentally during evaluation of a bone fracture or surgical exploration.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

The diagnosis of liver cancer is based on clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, radiological examination and tissue pathology. In individuals without cirrhosis, liver scans can document filling defects. CT or ultrasonography is used to detect solid tumours, but neither can distinguish benign from malignant tumours.

Surgical resection is possible only if the tumour is localised to a removable lobe of the liver. Chemotherapeutic agents are administered systemically or locally, but their use may be limited to the presence of advanced cirrhosis.

The survival rate for those with symptomatic liver cancer is only 3–4 months. Surgery is hazardous and usually not undertaken if the individual has cirrhosis. Most individuals develop metastases after surgical resection, but long-term survival is possible. Liver transplant offers a cure if the waiting time is short.155

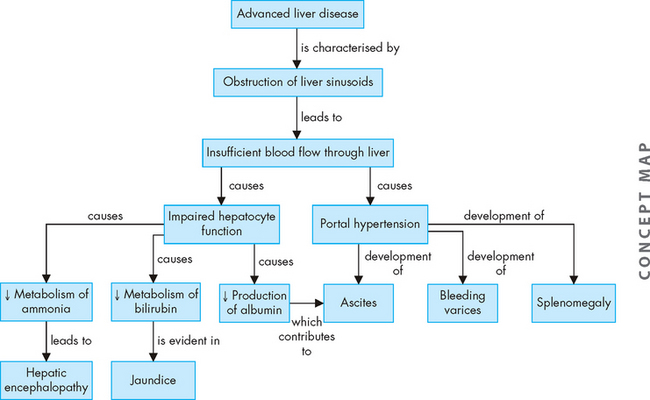

Clinical manifestations of hepatobiliary alterations

Of all the accessory organ disorders, acute or chronic liver disease leads to significant systemic, life-threatening complications. These complications include portal hypertension, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy and jaundice; these are linked in a concept map (see Figure 27-28).

Portal hypertension

Portal hypertension is abnormally high blood pressure in the hepatic portal venous system (the hepatic portal vein drains the nutrient-rich blood from the gastrointestinal tract to the liver). Pressure in this system is normally 3 mmHg; portal hypertension is an increase to at least 10 mmHg.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

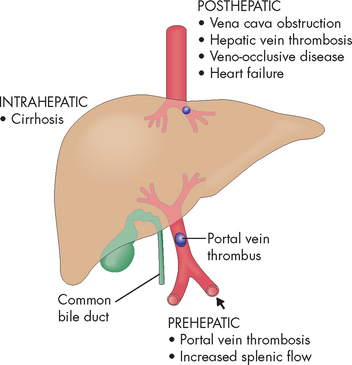

Portal hypertension is caused by disorders that obstruct or impede blood flow through any component of the portal venous system (into the liver) or vena cava (out of the liver). The poor blood flow through the liver causes a build-up of blood pressure prior to the liver. The most common cause of portal hypertension is obstruction caused by cirrhosis of the liver.156 Intrahepatic causes (from within the liver; see Figure 27-29) result from an abnormal flow of blood through the liver sinusoids. Conditions such as inflammation or fibrosis of the sinusoids, as occurs in cirrhosis of the liver and viral hepatitis, can block blood flow and lead to portal hypertension. Liver fibrosis in children can also lead to portal hypertension. Posthepatic causes (post = after) occur from hepatic vein thrombosis or cardiac disorders that impair the pumping ability of the right side of the heart. This causes blood to back up through the inferior vena cava and the liver, eventually increasing pressure in the portal system.

FIGURE 27-29 Portal hypertension.

Three forms of portal hypertension are recognised: posthepatic, intrahepatic and prehepatic.

Source: Based on Damjanov I. Pathology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

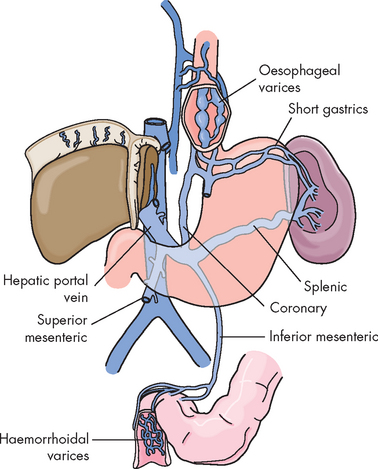

Long-term portal hypertension results in abnormalities in organs that are prior to the liver in terms of blood flow — the backlog in blood pressure in the hepatic portal vein affects organs anatomically associated with the gastrointestinal system and causes several problems that are difficult to treat and can be fatal:

FIGURE 27-30 Varices related to portal hypertension.

The portal vein, its major tributaries and the most important shunts (collateral veins) between the portal and caval systems.

Source: Based on Monahan FD et al. Phipps’ medical–surgical nursing: concepts and clinical practice. 8th edn. St Louis: Mosby; 2007.

Ascites and hepatic encephalopathy are discussed in the next sections.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Vomiting of blood from bleeding oesophageal varices is the most common clinical manifestation of portal hypertension. Slow, chronic bleeding from varices in the oesophagus and stomach causes anaemia, with digested blood in the stools. Usually the bleeding is from varices that have developed slowly over a period of years.

The elevated venous pressure results in rupture of oesophageal varices, causing haemorrhage and voluminous vomiting of dark-coloured blood. The ruptured varices are usually painless. Mortality from ruptured oesophageal varices ranges from 30% to 60%. Recurrent bleeding of oesophageal varices indicates a poor prognosis. Most individuals die within 1 year.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

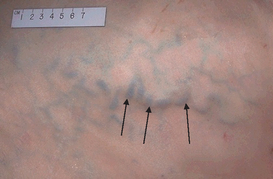

Portal hypertension is often diagnosed at the time of variceal bleeding and confirmed by endoscopy and evaluation of portal venous pressure. Distended collateral veins may radiate over the abdomen, giving rise to the description of caput medusae (Medusa head; see Figure 27-31). The individual usually has a history of jaundice, hepatitis or alcoholism.

FIGURE 27-31 Portal hypertension.

Dilation of the collateral venous circulation (arrows) may become evident on the abdomen of individuals with cirrhosis. Seen here is caput medusa, which consists of dilated veins radiating from the umbilicus.

Source: Klatt EC. Robbins and Cotran atlas of pathology. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010.

Emergency management of bleeding varices includes use of vasopressors (drugs that cause constriction of the affected blood vessels) and compression of the varices with an inflatable Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (a tube inserted into the oesophagus and stomach that provides direct pressure on the varices), sclerotherapy (injection of solution into the veins to stop the bleeding when under endoscopic examination) or variceal ligation (tying off the blood vessels that are bleeding). Surgical shunts may decompress the varices, but this treatment can precipitate encephalopathy or liver failure. Liver transplant is an alternative with end-stage liver disease; however, if the individual is actively bleeding, transplantation surgery is complicated.157

Ascites

Ascites is the accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity and is the most common complication of cirrhosis. Ascites traps body fluid in a ‘third space’ from which it cannot escape (third spacing is described in Chapter 29). The effect is to reduce the amount of fluid available for normal physiological functions. Cirrhosis is the most common cause of ascites, but others include heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, abdominal malignancies, nephrotic syndrome and malnutrition.158 Of individuals who develop ascites caused by cirrhosis, 25% die within 1 year. Continued heavy drinking of alcohol is associated with this mortality.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Several factors contribute to the development of ascites. Impaired excretion of sodium by the kidneys promotes water retention. Portal hypertension and reduced serum albumin levels cause capillary hydrostatic pressure (pressure outwards from the capillary; see Chapter 22) to exceed capillary osmotic pressure (pressure into the capillary). This imbalance pushes water into the peritoneal cavity. As a result peripheral vasodilation and decreased blood flow to the kidneys occur, as fluid is redirected to the peritoneal cavity; this also results in hormonal stimulation that promotes renal sodium and water retention (the main hormones are aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone). This expands plasma volume and can accelerate portal hypertension and ascites formation.159

Ascites can be complicated by bacterial peritonitis, an inflammatory response that increases mesenteric capillary permeability. As plasma seeps out of the permeable mesenteric capillaries, it adds to the volume of ascitic fluid. Figure 27-32 summarises the mechanisms by which cirrhosis of the liver causes ascites.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The accumulation of ascitic fluid causes weight gain, abdominal distension and increased abdominal girth (see Figure 27-33). Large volumes of fluid (10–20 L) displace the diaphragm and cause dyspnoea by decreasing lung capacity. Ventilatory rate increases and the individual assumes a semi-Fowler position (sitting up in bed at approximately 35–45°) to relieve the dyspnoea. Approximately 10% of individuals with ascites develop bacterial peritonitis, which causes fever, chills, abdominal pain, decreased bowel sounds and cloudy ascitic fluid.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Diagnosis is usually based on clinical manifestations and identification of liver disease. Paracentesis is used to aspirate ascitic fluid for bacterial culture, biochemical analysis and microscopic examination. The goal of treatment is to relieve discomfort. If restoration of liver function is possible, the ascites diminishes spontaneously. In the meantime, dietary salt restriction and potassium-sparing diuretics can reduce ascites. Serum electrolytes are monitored carefully because the individual is at risk for hyponatraemia and hypokalaemia (low blood sodium and potassium, respectively).

Palliative measures include paracentesis to remove 1–2 L of ascitic fluid and relieve respiratory distress. However, the removal of too much fluid relieves pressure on blood vessels and carries the risk of hypotension, shock or death. Despite repeated paracentesis, ascitic fluid re-accumulates in individuals with irreversible disease. Paracentesis is also likely to cause peritonitis. Other procedures include shunts to direct fluid into the bloodstream, as well as liver transplant. Individuals with ascites and portal hypertension have a poor prognosis.

Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy (altered brain structure) is a complex neurological syndrome characterised by impaired cerebral function, flapping tremor (known as asterixis) and EEG changes (electroencephalogram — shows the waves of brain function). The syndrome may develop rapidly during acute hepatitis or slowly during the course of chronic liver disease and the development of portal hypertension.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Hepatic encephalopathy results from a combination of biochemical alterations that affect neurotransmission, causing central nervous system disturbances and alterations in consciousness. Liver dysfunction and collateral vessels that shunt blood around the liver to the systemic circulation both permit toxins absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract to circulate freely to the brain, whereas in the healthy person, the liver would normally detoxify those substances. The most hazardous substances are end products of intestinal protein digestion, particularly ammonia. Ammonia that reaches the brain may alter cerebral energy metabolism or interfere with neurotransmitters. Infection, haemorrhage, electrolyte imbalance, zinc deficiency, sedatives and analgesics can worsen the encephalopathy.160

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Subtle changes in personality, memory loss, irritability, lethargy and sleep disturbances are common initial manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy. Symptoms then can progress to confusion, flapping tremor of the hands, stupor, convulsions and coma. Coma is usually a sign of liver failure and ultimately results in death.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy is based on a history of liver disease and clinical manifestations. EEG and blood chemistry tests provide supportive data. Correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalances and withdrawal of depressant drugs metabolised by the liver are first steps in the treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Restricting dietary protein intake and eliminating intestinal bacteria help to reduce blood ammonia levels. Lactulose may be administered to prevent ammonia absorption in the colon.161

Jaundice

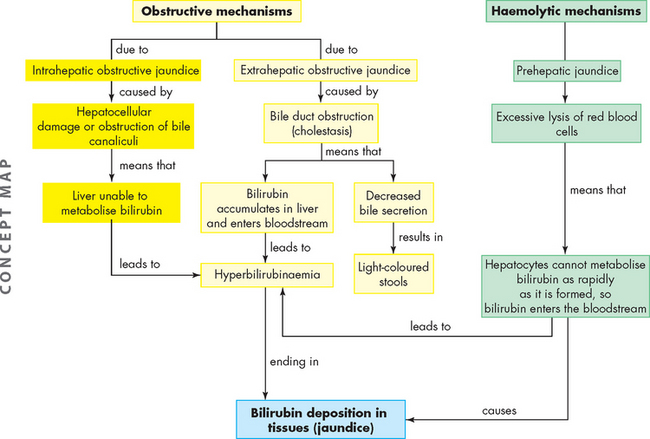

Jaundice (icterus) is a yellow or greenish pigmentation of the skin caused by hyperbilirubinaemia (plasma bilirubin concentrations above 40 mmol/L). Hyperbilirubinaemia and jaundice can result from excessive haemolysis of red blood cells or obstructive disorders of the bile ducts or liver cells (see Figure 27-34).

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Obstructive jaundice can result from extrahepatic obstruction (obstruction to bile flow out of the liver) or intrahepatic obstruction (obstruction to bile flow or production from within the liver).162 Extrahepatic obstructive jaundice develops if the common bile duct is occluded (e.g. by a gallstone or tumour). Bilirubin metabolised by the hepatocytes cannot flow into the duodenum. Therefore, it accumulates in the liver and enters the bloodstream, causing hyperbilirubinaemia and jaundice. As bilirubin increases in the blood, it is also excreted via the kidneys and therefore it appears in the urine.

Intrahepatic obstructive jaundice involves disturbances in hepatocyte function and obstruction of bile canaliculi.163 This commonly results from alcoholic cirrhosis and viral hepatitis. The metabolism of bilirubin is impaired and elevated levels appear in the blood and urine. Obstruction of bile canaliculi diminishes flow of metabolised bilirubin out of the liver into the common bile duct. In mild cases, some of the bile canaliculi open. Consequently, the amount of bilirubin in the intestinal tract may be only slightly decreased.

Excessive haemolysis (breakdown) of red blood cells can cause prehepatic jaundice (or haemolytic jaundice). Bilirubin is formed through breakdown of the haem component of aged red blood cells — when increased, this exceeds the ability of the liver to metabolise bilirubin, causing blood levels to rise. Mild prehepatic jaundice is normal in newborns (see below). Severe haemolytic crisis, such as that which occurs with sickle cell anaemia and haemolytic drugs, can cause jaundice. If hyperbilirubinaemia continues to increase, both haemolytic and liver disorders are indicated. The causes of jaundice are summarised in Table 27-11.

Table 27-11 THREE COMMON TYPES OF JAUNDICE

| TYPE | MECHANISM | CAUSES |

|---|---|---|

| Obstructive (posthepatic) jaundice | Obstruction of passage of bilirubin from liver to intestine | |

| Prehepatic (haemolytic) jaundice | Destruction of erythrocytes (increased bilirubin production) | |

| Hepatocellular (hepatic) jaundice | Failure of liver cells (hepatocytes) to metabolise bilirubin, and of bilirubin to pass from liver to intestine |

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Hyperbilirubinaemia may cause the urine to darken several days before the onset of jaundice. The complete obstruction of bile flow from the liver to the duodenum causes light-coloured stools. With partial obstruction, the stools are normal in colour and bilirubin is present in the urine.

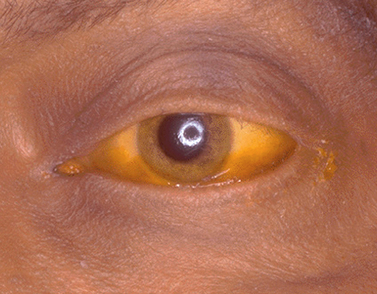

Fever, chills and pain often accompany jaundice resulting from viral or bacterial inflammation of the liver (e.g. viral hepatitis). Manifestations of liver injury from any cause commonly include anorexia, malaise and fatigue. Yellow discolouration may first occur in the sclera of the eye (see Figure 27-35) and then progress to the skin. Pruritus (itching) often accompanies jaundice because bilirubin accumulates in the skin.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Laboratory evaluation of serum bilirubin levels is essential. The history and physical examination identify underlying disorders, such as alcoholism, exposure to hepatitis virus or gallbladder disease. The treatment for jaundice consists of correcting the cause.

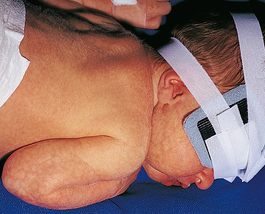

Neonatal jaundice

Neonatal jaundice is usually a transient icterus that occurs during the first week of life in otherwise healthy, full-term and preterm infants.164 It is caused by excessive breakdown of the fetal form of haemoglobin, which is a normal process that commences shortly after birth, to replace fetal haemoglobin with adult haemoglobin. This results in the haem component being broken down to bilirubin in relatively large quantities, but the immature liver is unable to metabolise the bilirubin quickly, so it becomes visible in yellow pigmentation of the eyes and skin. Although it is normal for newborns to experience mild jaundice, it requires monitoring in the days after birth for worsening of the condition.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The main cause in newborns is the normal breakdown of haemoglobin following birth, which results in increased production of bilirubin. It may also be caused by a different condition known as haemolytic disease of the newborn (ABO blood compatibility), which mainly occurs if the newborn is not the mother’s first baby (see Chapter 17).

Serum bilirubin should normally be under 20 µmol/L (see Table 26-3), but in jaundice it becomes much higher. Very high levels of hyperbilirubinaemia are considered pathological. There is a risk of brain damage (kernicterus) as the bilirubin passes across neonatal brain capillaries (the blood–brain barrier) and into brain cells of the basal nuclei.165 For this reason, persistent or worsening jaundice requires treatment.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Physiological jaundice develops during the second or third day after birth and usually subsides in 1–2 weeks in full-term infants and in 2–4 weeks in premature infants. After this, increasing bilirubin values and persistent jaundice indicate pathological hyperbilirubinaemia. Premature infants with respiratory distress, acidosis or sepsis are at greater risk for encephalopathy and the development of other conditions associated with impaired brain function.166

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Evaluation is by measuring serum bilirubin levels. Other causes of jaundice must be eliminated to confirm physiological jaundice. Treatment depends on the degree of hyperbilirubinaemia. Physiological jaundice is usually treated by phototherapy (ultraviolet light), which breaks down the bilirubin. Treatment is administered easily by placing the baby in an incubator or wrapping the baby in a suit to expose them to ultraviolet light (see Figure 27-36). Pathological jaundice requires an exchange transfusion and treatment of the underlying disorder.

Biliary disorders

Obstruction and inflammation are the most common disorders of the gallbladder. Obstruction is caused by gallstones, which are aggregates of substances in the bile. The gallstones may remain in the gallbladder or be ejected with bile into the cystic duct. Gallstones that become lodged in the cystic duct obstruct the flow of bile into and out of the gallbladder and cause inflammation. Gallstone formation is termed cholelithiasis. Inflammation of the gallbladder or cystic duct is known as cholecystitis.

Cholelithiasis

Cholelithiasis is a prevalent disorder in developed countries, where the incidence rate is 10–20%, although many individuals are asymptomatic. There are two types of gallstones: cholesterol and pigmented. Cholesterol stones are the most common, accounting for approximately 80–85% of cases in developed countries.167 Risk factors include female sex and middle age, as well as a number of potentially modifiable risk factors shown in Box 27-1. Cholelithiasis is in the top 10 diagnoses for hospitalisations in Australia; almost 50,000 Australians required overnight hospitalisation for this condition in 2007–2008.55

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Cholesterol gallstones form in bile that has excessive amounts of cholesterol produced by the liver.168 With a high amount of cholesterol in the bile fluid, the cholesterol cannot all be fully ‘dissolved’, so some of it appears in a solid form known as stones. This process usually occurs within the gallbladder, with other locations also in the biliary ducts (see Figures 27-37 and 27-38). The stones may lie dormant or become lodged in the cystic or common bile duct, causing pain and cholecystitis (inflammation).169 If the stones block the common bile duct, it can cause pathophysiology of the liver as well, due to insufficient drainage of the bile from the liver. The stones can accumulate and fill the entire gallbladder (see Figure 27-39). Pigmented stones form from increased levels of bilirubin, which binds with calcium.

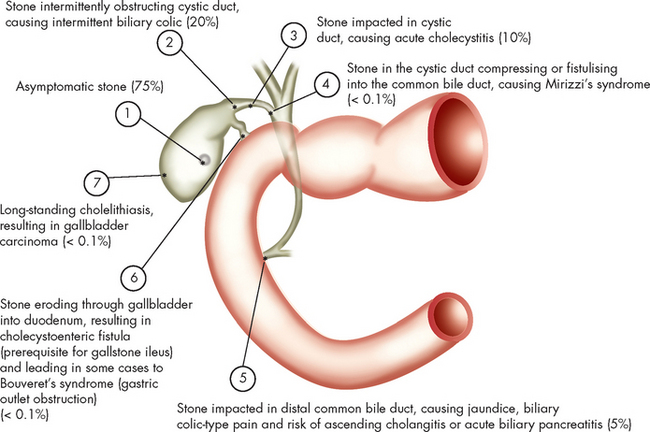

FIGURE 27-37 Schematic depiction of the natural history and complications of gallstones.

The percentages indicate the approximate frequencies of complications occurring in untreated patients, as based on natural history data. The most frequent outcome is for the patient with a stone to remain asymptomatic throughout life. Biliary pain, acute cholecystitis, cholangitis and pancreatitis are the most common complications. (The sum of the percentages is >100% because patients with acute cholecystitis generally have had prior episodes of biliary pain.)

Source: Feldman M et al. Sleisenger & Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. 8th edn. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Abdominal pain and jaundice are the cardinal manifestations of cholelithiasis. Vague symptoms include heartburn, flatulence, epigastric discomfort and food intolerances, particularly to fats and cabbage. The pain, known as biliary colic, is caused by the lodging of one or more gallstones in the cystic or common duct. It can be intermittent or steady and usually occurs in the right upper quadrant, radiating to the mid-upper area of the back. Jaundice indicates that the stone is located in the common bile duct.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Diagnosis is based on the history, physical examination and ultrasound or CT scan. An oral cholecystogram usually outlines the stones. Intravenous cholangiography is used to differentiate cholelithiasis from other causes of extrahepatic biliary obstruction if the cholecystogram is negative. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the preferred treatment for uncomplicated gallstones that cause obstruction or inflammation. Shockwave lithotripsy and laser lithotripsy may be used to fragment large bile duct stones before endoscopic removal.170

Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis can be acute or chronic, but both forms are almost always caused by a gallstone lodged in the cystic duct.171 The gallbladder becomes distended and inflamed, with pain similar to that caused by gallstones. Pressure against the distended wall of the gallbladder decreases blood flow and may result in ischaemia, necrosis and perforation. Fever, leucocytosis, rebound tenderness and abdominal muscle guarding are common findings. Serum bilirubin levels may be elevated. The acute abdominal pain of cholecystitis must be differentiated from that caused by pancreatitis, myocardial infarction and acute pyelonephritis of the right kidney. Cholangiography or radioactive scan can confirm the diagnosis.

Opioid analgesics may be required to control pain, and antibiotics (e.g. gentamicin, clindamycin) are often prescribed to manage bacterial infection in severe cases. Persistent symptoms or development of chronic cholecystitis punctuated by recurrent, acute attacks usually requires gallbladder resection (cholecystectomy). Obstruction may also lead to acute pancreatitis. If pancreatic abscesses develop, they are usually resected.170

Pancreatic disorders

Pancreatitis

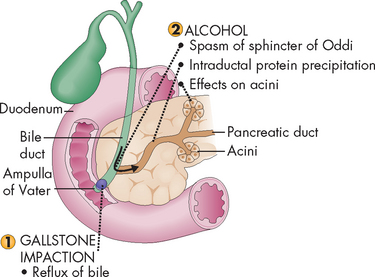

Pancreatitis, or inflammation of the pancreas, is a relatively rare and potentially serious disorder that occurs equally in men and women in their 50s. Pancreatitis is associated with conditions such as alcoholism, biliary tract obstruction (particularly due to cholelithiasis), peptic ulcers, trauma and hyperlipidaemia, as well as certain drugs.172

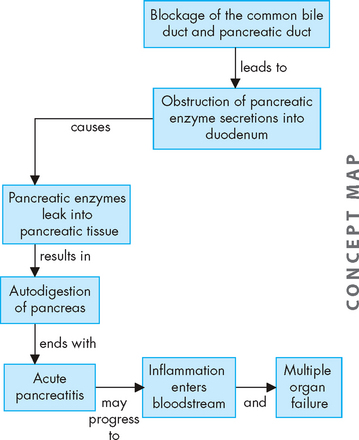

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Acute pancreatitis is usually a mild disease, but about 20% of those with the disease develop a severe pancreatic inflammation requiring hospital care. Alcoholism and biliary tract obstruction because of gallstones are commonly associated with this condition.172 Bile and pancreatic duct obstruction (such as from stones; see Figure 27-40) impairs the outflow of pancreatic enzymes, allowing them to leak into pancreatic tissue. This causes autodigestion (digestion by the enzymes secreted from the pancreas) and acute pancreatitis. The resulting inflammation entering the bloodstream can cause coagulation abnormalities and injury to vessels and other organs, such as the lungs and kidneys. Myocardial depression and shock can develop and translocation of bacteria may cause sepsis. These systemic effects are major causes of multiple organ involvement, morbidity and mortality.173,174

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Epigastric or mid-abdominal pain ranging from mild abdominal discomfort to severe, incapacitating pain is caused by: (1) oedema, which distends the pancreatic ducts and capsule; (2) chemical irritation and inflammation of the peritoneum; and (3) irritation or obstruction of the biliary tract (see Figure 27-41). Fever and leucocytosis accompany the inflammatory response. Nausea and vomiting are caused by hypermotility or paralytic ileus secondary to the pancreatitis or peritonitis.

Abdominal distension accompanies bowel hypermotility and the accumulation of fluids in the peritoneal cavity. Hypotension and shock occur often because plasma volume is lost as enzymes and kinins released into the circulation increase vascular permeability and dilate vessels. Hypovolaemia, hypotension and myocardial insufficiency result. In severe cases, hypovolaemia decreases renal blood flow sufficiently to impair renal function. Transient hyperglycaemia also can occur if glucagon is released from damaged alpha cells in the pancreatic islets (see Chapter 11). Multiple organ failure accounts for most deaths with severe acute pancreatitis.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, identification of associated disorders and laboratory studies. Elevated pancreatic amylase in serum is a characteristic but is not diagnostic of severity or specificity of disease. Serum lipase elevations are a sensitive marker of pancreatic injury, particularly of acute alcoholic pancreatitis. Elevated serum lactic dehydrogenase and C-reactive protein levels are associated with severe pancreatitis.175

The goal of treatment for acute pancreatitis is to stop the process of autodigestion and prevent systemic complications. Opioid analgesics may be needed to relieve pain. To decrease pancreatic secretions and ‘rest the gland’, oral food and fluids are withheld and continuous gastric suction is instituted. Nasogastric suction may not be necessary with mild pancreatitis, but it helps to relieve pain and prevent paralytic ileus in individuals who are nauseated and vomiting. Parenteral fluids are essential to restore blood volume and prevent hypotension and shock. Drugs that decrease gastric acid production can decrease stimulation of the pancreas by secretin (see Table 26-1). Antibiotics may control infection. The risk of mortality increases significantly with the development of infection or pulmonary, cardiac and renal complications.176

Chronic pancreatitis

Structural or functional impairment of the pancreas leads to chronic pancreatitis. Chronic alcohol abuse is the most common cause, and smoking increases the risk of chronic pancreatitis.177 Chronic pancreatitis causes continuous or intermittent abdominal pain, which usually intensifies after a meal. Occasionally manifestations of pancreatic enzyme deficiency, such as steatorrhoea or a malabsorption syndrome, are present. To correct enzyme deficiencies and prevent malabsorption, oral enzyme replacements are taken before and during meals. Loss of islet cell function can cause insulin-dependent diabetes. Cessation of alcohol intake is essential for the management of chronic pancreatitis.

Fibrosis, strictures, continued inflammation, calcification and pancreatic cysts are common lesions of chronic pancreatitis. The cysts are walled-off areas or pockets of pancreatic juice, necrotic debris or blood within or adjacent to the pancreas. Surgical drainage or partial resection of the pancreas may be required to relieve pain and to prevent cystic rupture.178 Chronic pancreatitis is a risk factor for pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer is almost twice as prevalent as liver cancer in Australia, with more than 2000 cases in Australia in 2005 (2.2% of the total number of cancer cases).1 Pancreatic cancer has a high mortality rate and is the fifth highest cause of death from cancer in males and females.1 It is ranked number 14 on the leading causes of death, and was responsible for the death of 2250 Australians in 2007.8 Mortality is nearly 100% — if the cancer is unable to be removed and is metastatic, then the goal of treatment is palliation.179

The cause of pancreatic cancer is not known, but there are modest risks associated with cigarette smoking, certain dietary factors, obesity, diabetes mellitus and chronic pancreatitis.180

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Cancer of the pancreas can arise from exocrine or endocrine cells (exocrine cells release secretions through ducts, while endocrine cells release hormones into the bloodstream). Most pancreatic tumours are adenocarcinomas of the pancreatic ducts (ductal adenocarcinomas). Tumours arising in small ducts invade nearby glandular tissue, penetrate the covering of the pancreas and extend into surrounding tissues.181

Ductal adenocarcinomas can occur in the head, body or tail of the pancreas, with most occurring in the head. Tumours of the head quickly spread to obstruct the common bile duct and portal vein. Ductal adenocarcinomas arising in the head of the pancreas cause biliary obstruction somewhat early in the disease. Lymphatic invasion occurs early, and rapidly involves local and regional lymph nodes. Venous invasion causes metastases to the liver. Tumour implants on the peritoneal surface can obstruct veins and promote the development of ascites. Individuals with ductal adenocarcinomas in the pancreatic head survive slightly longer than those with cancer of the body or tail of the pancreas, presumably because the symptoms associated with the liver prompt them to seek medical attention earlier.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Cancer of the body and tail of the pancreas is generally asymptomatic until there is intraductal destruction or the tumour invades adjacent tissue. Often vague back pain is an initial symptom. Jaundice develops in most cases, usually caused by obstruction of the bile duct. Because obstruction impairs enzyme secretion and flow to the duodenum, pancreatic cancer causes fat and protein malabsorption, resulting in weight loss.182 Distant metastases are found in the neck nodes, the lungs and the brain. Most individuals die of hepatic failure or blockage of the hepatobiliary ducts.

EVALUATION AND TREATMENT

Ultrasonography and CT scans may be needed, and a laparotomy (an incision through the abdominal wall to gain access to the abdominal cavity) is used to establish a definitive diagnosis, evaluate the extent of disease and determine whether palliative bypass surgery is needed.

Pancreatic cancer is difficult to treat, as it is non-responsive to many anti-cancer drugs. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are used as palliative measures. Because almost all pancreatic cancers are advanced at the time of diagnosis, staging has little relevance in determining treatment.183 Five-year survival is approximately 3% in Australia.179

Disorders of the gastrointestinal tract

Cancer of the colon and rectum (colorectal cancer) accounts for approximately 13–14% of the total incidence of cancer in Australia and New Zealand.

Cancer of the colon and rectum (colorectal cancer) accounts for approximately 13–14% of the total incidence of cancer in Australia and New Zealand. Genetics and lifestyle factors may be involved in the development of colorectal cancer. Pre-existing polyps are highly associated with adenocarcinoma of the colon.

Genetics and lifestyle factors may be involved in the development of colorectal cancer. Pre-existing polyps are highly associated with adenocarcinoma of the colon. Tumours of the right (ascending) colon are usually large and bulky; tumours of the left (descending, sigmoid) colon develop as small, button-like masses. Manifestations of colon tumours include pain, bloody stools and a change in bowel habits.

Tumours of the right (ascending) colon are usually large and bulky; tumours of the left (descending, sigmoid) colon develop as small, button-like masses. Manifestations of colon tumours include pain, bloody stools and a change in bowel habits. Rectal carcinoma is located up to 15 cm from the opening of the anus. The tumour spreads transmurally to the vagina in women or the prostate in men.

Rectal carcinoma is located up to 15 cm from the opening of the anus. The tumour spreads transmurally to the vagina in women or the prostate in men. Population screening for colorectal cancer is being introduced in Australia, while it is in the planning stages for New Zealand.

Population screening for colorectal cancer is being introduced in Australia, while it is in the planning stages for New Zealand. Colorectal cancer can be diagnosed using a faecal occult blood test and colonoscopy, while other procedures may also assist. Treatment is usually surgical removal, with chemotherapy and radiotherapy often used as well.

Colorectal cancer can be diagnosed using a faecal occult blood test and colonoscopy, while other procedures may also assist. Treatment is usually surgical removal, with chemotherapy and radiotherapy often used as well. Cancer of the oesophagus is rare in Australia and New Zealand. Alcohol and tobacco use, reflux oesophagitis and nutritional deficiencies are associated with oesophageal carcinoma.

Cancer of the oesophagus is rare in Australia and New Zealand. Alcohol and tobacco use, reflux oesophagitis and nutritional deficiencies are associated with oesophageal carcinoma. Dysphagia and chest pain are the primary manifestations of oesophageal cancer. Early treatment of tumours that have not spread into the mediastinum or lymph nodes results in a good prognosis.

Dysphagia and chest pain are the primary manifestations of oesophageal cancer. Early treatment of tumours that have not spread into the mediastinum or lymph nodes results in a good prognosis. Gastric carcinoma is associated with high salt intake, food preservatives (such as nitrates) and atrophic gastritis.

Gastric carcinoma is associated with high salt intake, food preservatives (such as nitrates) and atrophic gastritis. Approximately 50% of all gastric cancers are located in the prepyloric antrum. Clinical manifestations (weight loss, upper abdominal pain, vomiting, haematemesis, anaemia) develop only after the tumour has penetrated the wall of the stomach.

Approximately 50% of all gastric cancers are located in the prepyloric antrum. Clinical manifestations (weight loss, upper abdominal pain, vomiting, haematemesis, anaemia) develop only after the tumour has penetrated the wall of the stomach. Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory disease that causes ulceration, abscess formation and necrosis of the colonic and rectal mucosa.

Ulcerative colitis is an inflammatory disease that causes ulceration, abscess formation and necrosis of the colonic and rectal mucosa. Symptoms of ulcerative colitis include cramping pain, bleeding, frequent diarrhoea, dehydration and weight loss. A course of frequent remissions and exacerbations is common.

Symptoms of ulcerative colitis include cramping pain, bleeding, frequent diarrhoea, dehydration and weight loss. A course of frequent remissions and exacerbations is common. Crohn’s disease is similar to ulcerative colitis, but it affects both the large and the small intestines and ulceration tends to involve all the layers of the lumen.

Crohn’s disease is similar to ulcerative colitis, but it affects both the large and the small intestines and ulceration tends to involve all the layers of the lumen. ‘Skip lesion’ fissures and granulomas are characteristic of Crohn’s disease. Abdominal tenderness, diarrhoea and weight loss are the usual symptoms.

‘Skip lesion’ fissures and granulomas are characteristic of Crohn’s disease. Abdominal tenderness, diarrhoea and weight loss are the usual symptoms. Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional disorder with no known structural or biochemical alterations. It may manifest as diarrhoea or constipation. Intestinal hypersensitivity and alterations in motility and secretion are associated.

Irritable bowel syndrome is a functional disorder with no known structural or biochemical alterations. It may manifest as diarrhoea or constipation. Intestinal hypersensitivity and alterations in motility and secretion are associated. Diverticula are outpouchings of colonic mucosa through the muscle layers of the colon wall. Diverticulosis is the presence of these outpouchings; diverticulitis is inflammation of the diverticula.

Diverticula are outpouchings of colonic mucosa through the muscle layers of the colon wall. Diverticulosis is the presence of these outpouchings; diverticulitis is inflammation of the diverticula. Appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency of the abdomen. Obstruction of the lumen leads to increased pressure, ischaemia and inflammation of the appendix. Without surgical resection, inflammation may progress to gangrene, perforation and peritonitis.

Appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency of the abdomen. Obstruction of the lumen leads to increased pressure, ischaemia and inflammation of the appendix. Without surgical resection, inflammation may progress to gangrene, perforation and peritonitis. Regurgitation of bile, use of anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol and some systemic diseases are associated with gastritis.

Regurgitation of bile, use of anti-inflammatory drugs or alcohol and some systemic diseases are associated with gastritis. A peptic ulcer is an area of mucosal inflammation and ulceration caused by excessive secretion of gastric acid or disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, or both. There are three types of peptic ulcers: duodenal, gastric and stress ulcers.

A peptic ulcer is an area of mucosal inflammation and ulceration caused by excessive secretion of gastric acid or disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, or both. There are three types of peptic ulcers: duodenal, gastric and stress ulcers. Duodenal ulcers, the most common peptic ulcers, are associated with increased numbers of parietal (acid-secreting) cells in the stomach, elevated gastrin levels and rapid gastric emptying. Pain occurs when the stomach is empty and it is relieved with food or antacids. Duodenal ulcers tend to heal spontaneously and recur frequently.

Duodenal ulcers, the most common peptic ulcers, are associated with increased numbers of parietal (acid-secreting) cells in the stomach, elevated gastrin levels and rapid gastric emptying. Pain occurs when the stomach is empty and it is relieved with food or antacids. Duodenal ulcers tend to heal spontaneously and recur frequently. Gastric ulcers develop near parietal cells, generally in the antrum, and tend to become chronic. Gastric secretions may be normal or decreased and pain may occur after eating.

Gastric ulcers develop near parietal cells, generally in the antrum, and tend to become chronic. Gastric secretions may be normal or decreased and pain may occur after eating. Deficient lactase production in the brush border of the small intestine inhibits the breakdown of lactose; this condition is known as lactose intolerance. This prevents lactose absorption and causes osmotic diarrhoea.

Deficient lactase production in the brush border of the small intestine inhibits the breakdown of lactose; this condition is known as lactose intolerance. This prevents lactose absorption and causes osmotic diarrhoea. Coeliac disease results when the consumption of gluten in wheat and other grains destroys villi in the small intestine. This can lead to malabsorption of a number of nutrients.

Coeliac disease results when the consumption of gluten in wheat and other grains destroys villi in the small intestine. This can lead to malabsorption of a number of nutrients. The most common symptom of coeliac disease is diarrhoea, due to the large amount of undigested fats (and other substances) in the intestines.

The most common symptom of coeliac disease is diarrhoea, due to the large amount of undigested fats (and other substances) in the intestines. Although previously considered a childhood illness, it is now recognised that many cases of coeliac disease are not diagnosed until well into adulthood.

Although previously considered a childhood illness, it is now recognised that many cases of coeliac disease are not diagnosed until well into adulthood. Malnutrition is lack of nourishment from inadequate amounts of kilojoules, protein, vitamins or minerals. Starvation is an extreme state of malnutrition. Cachexia is physical wasting associated with chronic disease.

Malnutrition is lack of nourishment from inadequate amounts of kilojoules, protein, vitamins or minerals. Starvation is an extreme state of malnutrition. Cachexia is physical wasting associated with chronic disease. Short-term starvation, or lack of dietary intake for 3 or 4 days, stimulates stored glucose to be produced from glucose stores and non-carbohydrate molecules.

Short-term starvation, or lack of dietary intake for 3 or 4 days, stimulates stored glucose to be produced from glucose stores and non-carbohydrate molecules. Long-term starvation triggers the breakdown of ketone bodies and fatty acids. Eventually proteolysis (protein breakdown) begins and death ensues if nutrition is not restored.

Long-term starvation triggers the breakdown of ketone bodies and fatty acids. Eventually proteolysis (protein breakdown) begins and death ensues if nutrition is not restored. Gastro-oesophageal reflux is the regurgitation of chyme from the stomach into the oesophagus. An inflammatory response ensues if the oesophageal mucosa is repeatedly exposed to acids and enzymes in the regurgitated chyme.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux is the regurgitation of chyme from the stomach into the oesophagus. An inflammatory response ensues if the oesophageal mucosa is repeatedly exposed to acids and enzymes in the regurgitated chyme. Faecal incontinence is the inability to have a voluntary bowel movement or the inability to control bowel movements. There may be more people affected by this condition than indicated by current statistics, due to embarrassment and underreporting to medical staff.

Faecal incontinence is the inability to have a voluntary bowel movement or the inability to control bowel movements. There may be more people affected by this condition than indicated by current statistics, due to embarrassment and underreporting to medical staff. Hiatal hernia is the protrusion of the upper part of the stomach through the hiatus (oesophageal opening in the diaphragm) at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Hiatal hernia can be sliding or para-oesophageal.

Hiatal hernia is the protrusion of the upper part of the stomach through the hiatus (oesophageal opening in the diaphragm) at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Hiatal hernia can be sliding or para-oesophageal. Intestinal obstruction prevents the normal movement of chyme through the intestinal tract. It can be due to intussusception, volvulus, abdominal hernia or paralytic ileus.

Intestinal obstruction prevents the normal movement of chyme through the intestinal tract. It can be due to intussusception, volvulus, abdominal hernia or paralytic ileus. Vomiting is the forceful emptying of the stomach by gastrointestinal contraction and reverse peristalsis of the oesophagus. It is usually preceded by nausea and retching, with the exception of projectile vomiting, which is associated with direct stimulation of the vomiting centre in the brain.

Vomiting is the forceful emptying of the stomach by gastrointestinal contraction and reverse peristalsis of the oesophagus. It is usually preceded by nausea and retching, with the exception of projectile vomiting, which is associated with direct stimulation of the vomiting centre in the brain. Constipation is often caused by unhealthy dietary and bowel habits combined with lack of exercise. Constipation can also result from a disorder that impairs intestinal motility or obstructs the intestinal lumen.

Constipation is often caused by unhealthy dietary and bowel habits combined with lack of exercise. Constipation can also result from a disorder that impairs intestinal motility or obstructs the intestinal lumen. Diarrhoea can be caused by excessive fluid drawn into the intestinal lumen by osmosis (osmotic diarrhoea), excessive secretion of fluids by the intestinal mucosa (secretory diarrhoea) or excessive gastrointestinal motility.

Diarrhoea can be caused by excessive fluid drawn into the intestinal lumen by osmosis (osmotic diarrhoea), excessive secretion of fluids by the intestinal mucosa (secretory diarrhoea) or excessive gastrointestinal motility. Diarrhoea is of particular concern in young children, who are susceptible to changes in fluid balance. Severe dehydration from diarrhoea can be fatal. Childhood diarrhoea is often caused by rotavirus.

Diarrhoea is of particular concern in young children, who are susceptible to changes in fluid balance. Severe dehydration from diarrhoea can be fatal. Childhood diarrhoea is often caused by rotavirus. Dysphagia is difficulty swallowing. It can be caused by a mechanical or functional obstruction of the oesophagus. Functional obstruction is an impairment of oesophageal motility.

Dysphagia is difficulty swallowing. It can be caused by a mechanical or functional obstruction of the oesophagus. Functional obstruction is an impairment of oesophageal motility.Disorders of the hepatobiliary system and pancreas

Fatty deposition resulting from alcohol consumption contributes to alcoholic liver disease, which can progress from fatty liver to alcoholic hepatitis and finally to alcoholic cirrhosis.

Fatty deposition resulting from alcohol consumption contributes to alcoholic liver disease, which can progress from fatty liver to alcoholic hepatitis and finally to alcoholic cirrhosis. Alcoholic cirrhosis impairs the hepatocytes’ ability to metabolise and remove a range of potentially harmful substances from the bloodstream.

Alcoholic cirrhosis impairs the hepatocytes’ ability to metabolise and remove a range of potentially harmful substances from the bloodstream. Alcoholic liver disease is reversible in the early stages, so cessation of alcohol consumption is vital to limit worsening of the condition.

Alcoholic liver disease is reversible in the early stages, so cessation of alcohol consumption is vital to limit worsening of the condition. Clinical manifestations of alcoholic liver disease include ascites, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy and oesophageal varices.

Clinical manifestations of alcoholic liver disease include ascites, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy and oesophageal varices. Viral hepatitis is an infection of the liver caused by a strain of the hepatitis virus — hepatitis A, B and C are most common in Australia and New Zealand.

Viral hepatitis is an infection of the liver caused by a strain of the hepatitis virus — hepatitis A, B and C are most common in Australia and New Zealand. Although they differ with respect to modes of transmission and severity of acute illness, all types of viral hepatitis can cause hepatic cell necrosis, Kupffer cell hyperplasia and infiltration of liver tissue by mononuclear phagocytes. These changes obstruct bile flow and impair hepatocyte function.

Although they differ with respect to modes of transmission and severity of acute illness, all types of viral hepatitis can cause hepatic cell necrosis, Kupffer cell hyperplasia and infiltration of liver tissue by mononuclear phagocytes. These changes obstruct bile flow and impair hepatocyte function. The clinical manifestations of viral hepatitis depend on the stage of infection. Fever, malaise, anorexia and liver enlargement and tenderness characterise the pre-icteric phase (stage 1). Jaundice and hyperbilirubinaemia mark the icteric phase (stage 2). During the recovery phase (stage 3), symptoms resolve. Recovery takes several weeks.

The clinical manifestations of viral hepatitis depend on the stage of infection. Fever, malaise, anorexia and liver enlargement and tenderness characterise the pre-icteric phase (stage 1). Jaundice and hyperbilirubinaemia mark the icteric phase (stage 2). During the recovery phase (stage 3), symptoms resolve. Recovery takes several weeks. Chronic hepatitis is a complication of hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus. It causes widespread hepatic necrosis and is often fatal.

Chronic hepatitis is a complication of hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus. It causes widespread hepatic necrosis and is often fatal. Primary liver cancers are associated with chronic liver disease (cirrhosis, hepatitis B). Hepatocellular carcinomas arise from the hepatocytes, whereas cholangiocellular carcinomas arise from the bile ducts. Primary liver cancer spreads to the heart, lungs, brain, kidneys and spleen through the circulation.

Primary liver cancers are associated with chronic liver disease (cirrhosis, hepatitis B). Hepatocellular carcinomas arise from the hepatocytes, whereas cholangiocellular carcinomas arise from the bile ducts. Primary liver cancer spreads to the heart, lungs, brain, kidneys and spleen through the circulation. Portal hypertension is an elevation of portal venous pressure, caused by increased resistance to venous flow in the portal vein, including the sinusoids and hepatic vein.

Portal hypertension is an elevation of portal venous pressure, caused by increased resistance to venous flow in the portal vein, including the sinusoids and hepatic vein. Portal hypertension is the most serious complication of liver disease because it can cause potentially fatal complications, such as bleeding varices, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy.

Portal hypertension is the most serious complication of liver disease because it can cause potentially fatal complications, such as bleeding varices, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. Ascites is the accumulation and sequestration of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, often as a result of portal hypertension and decreased concentrations of plasma proteins.

Ascites is the accumulation and sequestration of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, often as a result of portal hypertension and decreased concentrations of plasma proteins. Hepatic encephalopathy is impaired cerebral function caused by blood-borne toxins (particularly ammonia) not being metabolised by the liver. Toxin-bearing blood may bypass the liver in collateral vessels opened as a result of portal hypertension or diseased hepatocytes may be unable to carry out their metabolic functions.

Hepatic encephalopathy is impaired cerebral function caused by blood-borne toxins (particularly ammonia) not being metabolised by the liver. Toxin-bearing blood may bypass the liver in collateral vessels opened as a result of portal hypertension or diseased hepatocytes may be unable to carry out their metabolic functions. Manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy range from confusion and asterixis (flapping tremor of the hands) to loss of consciousness, coma and death.

Manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy range from confusion and asterixis (flapping tremor of the hands) to loss of consciousness, coma and death. Jaundice (icterus) is a yellow or greenish pigmentation of the skin or sclera of the eyes caused by increases in plasma bilirubin concentration (hyperbilirubinaemia).

Jaundice (icterus) is a yellow or greenish pigmentation of the skin or sclera of the eyes caused by increases in plasma bilirubin concentration (hyperbilirubinaemia). Obstructive jaundice is caused by obstructed bile canaliculi (intrahepatic obstructive jaundice) or obstructed bile ducts outside the liver (extrahepatic obstructive jaundice). Bilirubin accumulates proximal to sites of obstruction, enters the bloodstream and is carried to the skin and deposited.

Obstructive jaundice is caused by obstructed bile canaliculi (intrahepatic obstructive jaundice) or obstructed bile ducts outside the liver (extrahepatic obstructive jaundice). Bilirubin accumulates proximal to sites of obstruction, enters the bloodstream and is carried to the skin and deposited. Prehepatic jaundice is caused by destruction of red blood cells at a rate that exceeds the liver’s ability to metabolise bilirubin. Although this is a normal process in the newborn, it must be monitored for worsening or persistence to avoid kernicterus (brain damage caused by the bilirubin).