33 INTRODUCTION TO CONTEMPORARY HEALTH ISSUES

INTRODUCTION

Up until this point in the textbook, we have explored pathophysiological processes at both a cellular level and an organ level. We have examined diseases of an organ system and explained how the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of signs and symptoms arise. However, many diseases, such as atherosclerosis, affect more than one organ system, resulting in a range of clinical disorders. Moreover, while some diseases, such as hepatitis, may be associated with only one organ system, they can greatly affect other body systems too. For instance, hepatitis can alter the coagulation, digestive, immune and nervous systems.

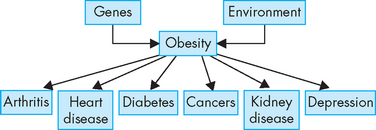

Unfortunately, in modern Western countries such as Australia and New Zealand a large percentage of the population have been or are exposed to conditions that predisposes them to altered health and diseases that can affect several organ systems. The most obvious example of this is obesity, which can lead to a range of diseases. While most Australians and New Zealanders have a life expectancy that is among the longest in the world, our contemporary lifestyles expose us to a range of environmental circumstances that significantly contribute to poor health and morbidity (illnesses that contribute to decreased quality of life) in our societies. Add to this a genetic predisposition to particular diseases and it can be seen that many individuals may not have optimum health. The areas of greatest concern are the expanding ageing population and the associated risk of disease (particularly cancer), increasing rates of obesity and diabetes mellitus in adults and children, the impact of stress on disease, the prevalence of mental health issues, and groups within the population who have poor health outcomes, such as the Indigenous population.

Health services in Australia and New Zealand face an overarching and paradoxical problem: on the one hand the population is getting older and with advances in medical technology we can keep people alive who would previously have died from their conditions, but on the other hand rates of morbidity and disease are increasing predominately due to lifestyle factors. Many individuals you will encounter in the health service are likely to have poor health with complicated pathophysiological conditions due to an increasing number of co-morbidities. Accordingly, this section explores common contemporary health conditions affecting our populations. We also examine relationships between these altered health conditions and how they affect the whole body, rather than a single organ.

Contemporary health refers to the current health of individuals and the health status of the populations as a whole. In Western countries like Australia and New Zealand, individuals typically have a long life expectancy — life expectancy has increased due to comprehensive national childhood and at-risk group immunisation programs, improvements in public hygiene (such as fluoridation of the water supplies) and an elevation in living standards. Furthermore, the majority of individuals have access to advanced medical technology, which significantly contributes to their quality of life.

However, despite these factors a number of health conditions and diseases significantly contribute to the poor health and morbidity of a large percentage of the population. The majority of diseases causing mortality in Australia and New Zealand are not the same as those causing mortality in developing nations. For instance, the greatest single cause of death worldwide is infection.1 While infection is responsible for some deaths in Australia and New Zealand, rates are low compared to deaths from coronary heart disease, cancers and cerebrovascular disease.2,3 And although the medical management of such diseases has improved dramatically, lengthening life expectancy, greater numbers of individuals are now living with these diseases, which impact on their lifestyle. This section seeks to address why these ‘Western diseases’ are so prevalent in our population.

AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND: DEMOGRAPHICS

Current population

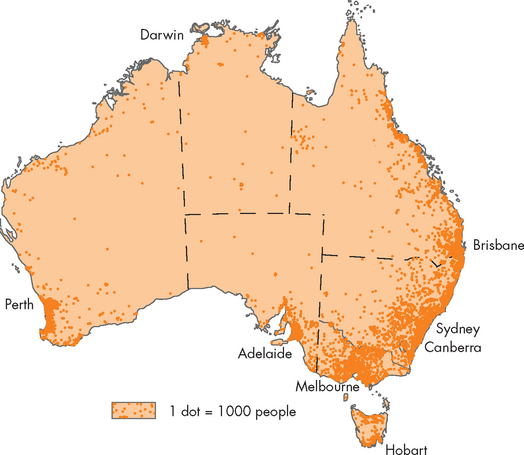

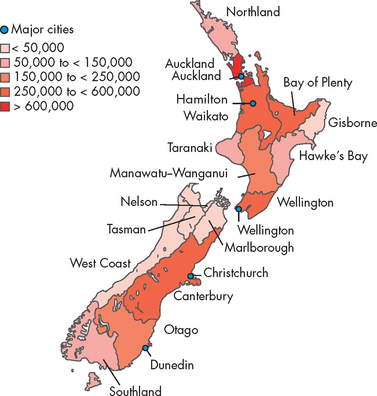

Compared with the rest of the world, the populations of Australia and New Zealand are tiny. Collectively, as of 2009 the population of the two countries was approximately 26.3 million people (Australia: 22 million, New Zealand: 4.3 million),4,5 within a global population of just over 6.7 billion, making Australia and New Zealand the 51st and 118th most populous countries in the world, respectively. Australia is one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world, but it is highly urbanised:6,7 approximately 85% of people reside in settlements of 10,000 persons or more.6 The vast majority of people live near the coast, in the eastern and south-eastern coastal strips: approximately 77% of the total population live in cities and towns within 50 kilometres of the coast (see Figure 33-1).8 About 95% of New Zealanders reside within 50 kilometres of the coast and 86% are considered urbanised (see Figure 33-2).9

FIGURE 33-1 Geographical distribution of the Australian population, 2006.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Year Book Australia. Catalogue no. 1301.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2008.

FIGURE 33-2 Geographical distribution of the New Zealand population, 2007.

Source: Ministry for the Environment. Environment New Zealand, 2007. Publication no. ME 847. Wellington, Ministry for the Environment; 2007.

Collectively, these findings highlight that rural residents are in the minority and that the majority choose to live in coastal regions, particularly urban settlements near the coast. This has several implications, as geographical location influences rates of morbidity and mortality. For example, it has been shown that rural residents have a lower life expectancy compared with their urban counterparts.10 The reason for this is likely to be multifactorial, but it is strongly influenced by a significantly lower life expectancy for the Indigenous population (see ‘Indigenous health’ below) and the large numbers of elderly people that tend to retire to rural areas. In contrast, the prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease and asthma are higher in cities and regional centres compared with rural and remote locations.11

Population projections

The populations of Australia and New Zealand are increasing, albeit slowly, at about 1% per year.11–13 4 6 The main reasons for this increase are a long life expectancy and immigration. This increase is expected to continue despite low fertility rates compared with the rest of the world — in Australia, the average age of a mother having her first child has increased by 6 years since 1971.2

It has been estimated that the Australian population will increase to approximately 35 million by 2050, although this may be between 30 and 43 million due to differing fertility rates, migration patterns and life expectancy.11,12 New Zealand’s projected population is approximately 5.5 million by 2061.13 While these populations do not appear to be large, especially compared with countries such as China (1.3 billion), large sections of Australia are uninhabitable and so the emphasis of population growth will be predominantly in the cities. Moreover, the future growth in the population will greatly expand the size of the ageing population.

Ageing

We are living longer. Average life expectancy in Australia is the second highest in the world, at 81.4 years — surpassed only by Japan.2 New Zealanders born in 2009 can expect to live until they are 80.5 years old.5 Females in both countries live for approximately 5 years more than males. There has been a sustained increase in life expectancy rates over the last century — for example, in 1901 life expectancy was only 55.2 years for males and 58 years for females.14

The percentage of the aged population will increase dramatically in the ensuing decades. For instance, it has been estimated that by 2050 approximately 25% of the population will be aged 65 years and older, up from 12% in 2009.11 Moreover, the percentage of people aged 85 years and older currently stands at about 1.5% of the total population, and this is projected to increase to about 8% by 2050.11 As a result, the population will become more skewed towards the elderly.

However, the dramatic increase in life expectancy seen over the last century is unlikely to continue. Based on assumptions about continuing living standards, by 2049 projected life expectancy is expected to increase to about 90 years of age for females and 86 years for males (see Table 33-1). However, these projections have been refuted and many researchers believe that average life expectancy will actually decline (see later in the chapter) due to the enormous amounts of chronic disease in the population.15–17 4 6

This highlights an important paradox touched on earlier: despite individuals in Australia and New Zealand having an increased life expectancy, the aged population will not necessarily be healthier. In fact, the ageing population will live with more morbidity, particularly the conditions and diseases of arthritis, cancer, hypertension, coronary heart disease, osteoporosis, dementia, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The prevalence of disease is already higher in the aged population and this trend is expected to continue.18 Therefore, the aged population will have even more reliance on the healthcare system.

Hospitalisation

The bedrock of our healthcare system is our hospitals. In Australia, as of 2009 there were more than 750 public hospitals and 550 private hospitals accounting for approximately 84,000 beds.20 Hospitals provide a range of medical services, but essentially if a member of society becomes ill, they will very likely be admitted to hospital for care. The aged population are likely to require more hospitalisations and more access to the healthcare system than the younger population.19 In 2007 there were about 7 million presentations to emergency departments and just under 8 million admissions to hospital20 — a large amount in a population of 22 million.

The average length of stay in hospital is currently 3.3 days, which means that individuals are spending less time in hospital than they did in 1998 (3.9 days). It should be stressed that the average length of stay for the 85 years and older age group extends out to more than 6 days, suggesting that the aged population will place a larger burden on the healthcare system.20

Mortality

In Australia, there were approximately 137,900 deaths in 2007.21 The number of male deaths (70,600) was greater than female deaths (67,300) and this is a consistent finding from year to year. In both sexes the top 20 causes of death account for 74% of all deaths, with coronary heart disease accounting for almost 1 in 5 deaths (or almost 12,500 deaths; see Table 33-2).2 Although individual types of cancer (such as lung, breast and prostate cancer) are in the top 10 causes of death, when metastatic cancers are grouped together they account for more deaths than any other single disease.

Table 33-2 CAUSES OF DEATH: AUSTRALIA

| RANKING | MALES | FEMALES |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coronary heart disease | Coronary heart disease |

| 2 | Lung cancer | Stroke |

| 3 | Stroke | Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease |

| 4 | Chronic lower respiratory diseases | Lung cancer |

| 5 | Prostate cancer | Breast cancer |

| 6 | Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease | Chronic lower respiratory diseases |

| 7 | Colorectal cancer | Heart failure |

| 8 | Blood and lymph cancer | Diabetes mellitus |

| 9 | Diabetes mellitus | Colorectal cancer |

| 10 | Suicide | Kidney disease |

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Deaths. Catalogue no. 3302.0. Canberra: ABS; 2007.

There were more than 28,000 deaths in New Zealand in 2006.22 Similar to Australia, coronary heart disease accounted for more deaths than any other disease, but metastatic cancers grouped together were the largest cause of death (8000 deaths; see Table 33-3).

Table 33-3 CAUSES OF DEATH: NEW ZEALAND

| RANKING | MALES | FEMALES |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coronary heart disease | Coronary heart disease |

| 2 | Stroke | Stroke |

| 3 | Chronic lower respiratory diseases* | Chronic lower respiratory diseases* |

| 4 | Lung cancer | Lung cancer |

| 5 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Breast cancer |

| 6 | Colorectal cancer | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| 7 | Prostate cancer | Colorectal cancer |

| 8 | Other heart diseases∧ | Other heart diseases∧ |

| 9 | Suicide | Diabetes mellitus |

| 10 | Diabetes mellitus | Organic mental disorders# |

| * Chronic lower respiratory diseases include bronchitis, asthma, emphysema and bronchiectasis. | ||

| ∧ Other heart diseases include pericardial diseases, valvular disorders, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, conduction disorders, cardiac arrest and heart failure. | ||

| # Organic mental disorders include dementias and delirium. | ||

Source: Ministry of Health. Mortality and demographic data, 2006. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2009.

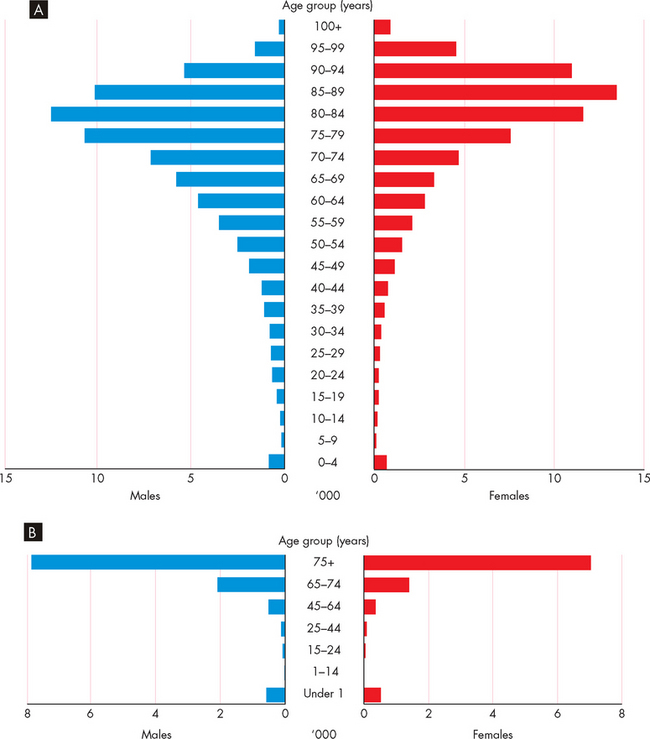

There are more deaths in the older populations in Australia and New Zealand. This simply reflects the longer life expectancies in both countries (see Figure 33-3), but it also shows that diseases which prematurely cause death in developing countries do not cause significant mortality in Western countries. For example, rates of infant mortality from infections are very high in developing countries but are low in Western countries.

FIGURE 33-3 Numbers of deaths according to age, and to sex per year.

Source: A Australian Bureau of Statistics. Deaths. Catalogue no. 3302.0. Canberra: ABS; 2007. B Ministry of Health. Mortality and demographic data, 2006. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2009.

While individual causes of death provide evidence about the health of a nation, to obtain a more accurate depiction of the mortality of a nation, we need to examine the causes of death for various age groups. For instance, heart disease is common in the aged population, cancer is more prevalent as individuals become older,23 injury and poisoning are the major causes of death in the younger population, and perinatal conditions and congenital anomalies are the most common causes of infant mortality (see Table 33-4).

Table 33-4 CAUSES OF DEATH BY AGE GROUP (TOP THREE CAUSES): AUSTRALIA

| AGE GROUP | MALES | FEMALES |

|---|---|---|

| < 1 year | ||

| 1–14 years | ||

| 15–24 years | ||

| 25–44 years | ||

| 45–64 years | ||

| 65–84 years | ||

| 85+ years |

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2008. Catalogue no. AUS 99. Canberra: AIHW; 2008.

CONTEMPORARY LIFESTYLE

While we are now living longer, an increasing number of older people are living with chronic illness. Unfortunately, in our society ageing is associated with an increasing prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, arthritis, osteoporosis and neurological deterioration like dementia and cancer. In this section we look at some of the conditions that impact on the development of these chronic diseases.

Stress

One aspect of contemporary lifestyle that has been shown to influence the development of disease and our response to disease is the impact of stress. Stress can be both physical and psychological. The stimuli for stress are referred to as stressors and they can vary, both in their manifestation and how they affect an individual. For instance, exercise can be considered a physical stressor. Over time, with repeated sessions and in prescribed amounts, exercise can have a positive effect on an individual and lead to significant increases in cardiorespiratory fitness. However, exercise can also cause depression of the immune system, especially in the period immediately after the exercise session.24 Moreover, prolonged endurance-type exercise in environmental conditions with an elevated air temperature may lead to heat stroke, which in turn can lead to death.25 Therefore, stress can be both beneficial and detrimental. The outcome depends on many factors, but it should be remembered that individuals respond differently to apparently similar stress situations.

Physical stressors, such as pain and exercise, are the most obvious examples of stress. However, psychological stressors can also impact negatively on an individual. It has been suggested that psychological stress occurs when the environmental demands that the individual perceives are greater than the individual’s adaptive capability.26 Whichever way the stress is perceived, the main physiological response is activation of the sympathetic nervous system with a concomitant release of the hormones cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline. This effect is termed the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, because it involves all of these glands. The release of hormones from these glands has a wide-ranging effect and in prolonged activation can lead to dysfunction of organ systems, such as the cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic and immune systems. In addition, it is generally believed that stress can influence or cause the development and progression of disease.

Many diseases have been implicated with stress, including autoimmune disorders, cancers, osteoporosis, dementia, cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus. The development of autoimmune disorders is likely to be multifactorial, with genetic, hormonal and immunological factors influencing the pathogenesis. However, in up to 50% of all autoimmune disorders the onset of disease has been attributed to unknown trigger factors. It has been suggested that either physical or psychological stress may be the unknown trigger in some instances and that this may influence the development of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.27 The likely link arises from stressors triggering the neuro-endocrine hormones, causing immune dysfunction by changing cytokine production. This can lead to autoimmune disorder manifestation.

Stress, the development of stress and the impacts of disease pathogenesis are discussed in detail in Chapter 34.

Dietary factors

Another factor that has been shown to change in more recent times is the diets of a large percentage of the Australian and New Zealand populations.28–31 29 30 31 It should be clarified that we are not referring here to diet meaning a specific weight-loss program, but rather to the usual food types consumed and the nutritional aspects of those foods. These dietary changes have occurred in the nutritional values of the food consumed, the size of the meals consumed and the frequency of eating. There is now strong evidence that these changes over the last three decades have considerably contributed to the epidemic of overweight and obese individuals and the linkage to diseases that impact on morbidity.2,31–37 32 33 34 35 36 37

Almost one-third of Australians now consume takeaway food every day,28 and in New Zealand the figure is likely to be similar.31 The term takeaway food can be slightly misleading, because it includes both fast foods and healthier choices such as salad sandwiches. Nevertheless, fast foods are typically higher in energy and saturated fats and have fewer micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) than other takeaway food. In addition, it has been estimated that almost one-third of the average energy intake is now derived from takeaway food, demonstrating a fundamental shift in dietary habits.38 Individuals from lower socioeconomic groups have been shown to consume more fast foods than individuals from higher socioeconomic groups.39 Evidence shows that takeaway and fast-food consumption is linked to weight gain and insulin resistance, which often lead to obesity and the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus.36

As well as the types of food that Australians and New Zealanders are consuming, the frequency and amounts of food being consumed have changed. For instance, Australian children are now consuming more ‘extra’ food, eating more meals than required each day. Such foods are often high in energy, fat and sugar, are referred to as ‘energy dense’ foods and have been shown to make up almost half of their daily energy intake.40 The other major concern is the marketing strategy of ‘upsizing’ that has occurred in the fast-food industry. Although this has been driven by large multinational companies, a survey of Australian fast-food outlets has shown that for each percentage increase in cost, there is a doubling of the energy value of the food items, comprising mainly fats and sugars.41 This is particularly of concern for individuals aged 15–24 years, as they are the highest consumers of fast food.31,36,40 Thus overconsumption of food is a major problem in contemporary society.

National health surveys have found that females are more likely to have healthier diets than males.18,29,31,35 However, overall the survey found that only 14% of Australians eat the recommended daily intake of vegetables and 54% eat the recommended daily fruit intake. In contrast, in New Zealand about two-thirds of adults consume the recommended daily intake of vegetables and just over half eat the recommended daily intake of fruit.35 These figures may be misleading, however, because: (1) the recommended intake of vegetables is 5 per day in Australia and 3 or more in New Zealand, so the target is easier to reach in New Zealand; and (2) the Australian National Health Survey surveyed individuals aged 12 years and older, while in New Zealand individuals aged 15 years and older were the target group. So the results may artificially lower the percentage of Australians eating vegetables. Having said this, clearly for both countries the minimum daily recommended fruit and vegetable intake is low, and this may contribute to the morbidity of the populations.

Dietary guidelines provide simple effective information about what the population should be eating, including the types of foods and the portions. A broad outline of the Australian dietary guidelines is shown in Box 33-1.

Box 33-1 DIETARY GUIDELINES FOR AUSTRALIAN ADULTS

Source: National Health and Medical Research Council. Dietary guidelines for Australian adults. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2003.

In Chapter 37 we consider the relative importance of genetic factors and the environment or lifestyle factors in disease development. Dietary factors are a significant part of contemporary lifestyles in this context.

Physical activity

The other area of significance to modern lifestyles is the volume of physical activity that the general population undertakes. We are not simply referring to formal sport here, but rather to the overall decrease in physical activity that has occurred due to the use of modern conveniences. Think of the multitude of devices that lower the amount of physical activity we undertake on a daily basis: cars, escalators, lifts, TV/stereo remote control units, the internet (including online purchasing, email, instant messaging), washing machines, microwaves, home delivery of groceries, domestic services (cleaning, ironing, washing), fast-food shops, mobile phones. Although many of these devices have increased productivity and accessibility for the majority of the population and are therefore seen as great advances, they have undoubtedly also contributed to a decline in physical activity in the general population.

In Australia and New Zealand large national surveys have been carried out asking participants to report their exercise activity levels over a specified time period, usually the previous 1–2 weeks. Accordingly, these statistics are based on a snapshot of physical activity, rather than longitudinal analysis. The results indicate that almost half the adult population undertake regular physical activity — about 33% undertaking moderate exercise and 15% vigorous exercise.18,42 The most active age group is the 18–29-year-olds.2

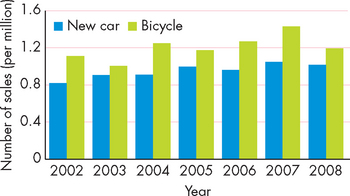

Between 2002 and 2008, the number of new bicycle sales increased and in fact new bicycles sales outnumbered new motor vehicle sales (see Figure 33-4). While this would seem encouraging, it is should be emphasised that just because bicycle sales are high, this does not translate into increased levels of physical activity. Although many people are taking steps to increase their physical activity levels, adherence to physical activity programs is generally weak.43–45 4 6 A number of factors contribute to this poor adherence, including a person’s age, sex, type of exercise, obesity and external motivators. Unfortunately, the positive aspects of regular physical activity are far outweighed by inactivity in the population.

FIGURE 33-4 New bicycle and motor vehicle sales, 2002–2008.

Since 2002, new bicycles sales have outnumbered new motor vehicle sales.

Source: www.cyclingpromotion.com.au/images/stories/factsheets/CPFBicycleSales2008.pdf; Chamber of Automotive Industries (www.fcai.com.au); Australian Bureau of Statistics. Sport and recreation: a statistical overview, Australia. Catalogue no. 4156.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2008.

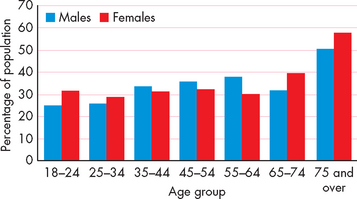

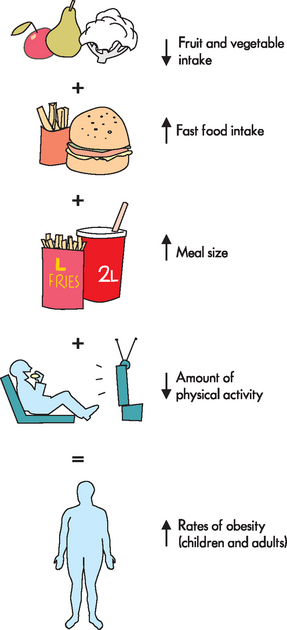

The national physical activity guidelines for Australians recommend at least 30 minutes of exercise most days of the week (see Box 33-2). However, 66% of children aged 5−14 years watch 2 or more hours of television per day and so are participating in activities that do not require increased energy expenditure.42 Moreover, one in seven adults are sedentary, meaning that they do not undertake exercise in any form.18,35,42 The prevalence of physical inactivity increases with age, which is consistent in both Australia and New Zealand (see Figure 33-5). Couple these facts with the changes taking place in eating habits and you find that energy intake (eating) is more than energy expenditure (physical activity) for a large percentage of the population, hence the large numbers of overweight and obese individuals (see Figure 33-6).

Box 33-2 NATIONAL PHYSICAL ACTIVITY GUIDELINES FOR AUSTRALIANS

These guidelines have been compiled to assist the population in determining the minimum levels of physical activity required to achieve good health. The recommendations include the following:

Source: Department of Health and Ageing. National Physical activity guidelines for Australians. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 1999.

FIGURE 33-5 Prevalence of people undertaking no exercise in the previous 2 weeks: Australia.

This graph indicates that as the population ages, the level of physical activity declines, and that about 33% of adults do not engage regularly in any exercise.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2008. Catalogue no. AUS 99. Canberra: AIHW; 2008

FIGURE 33-6 The relationship between dietary factors and physical activity and the development of obesity.

Physical activity is an important consideration when assessing the role of lifestyle in disease development, as discussed in Chapter 37.

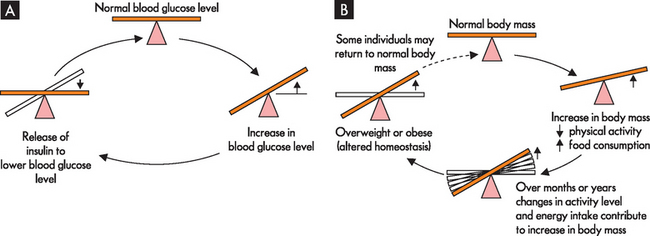

OBESITY

By far the greatest impact that contemporary lifestyle has had on health status is the increased prevalence of overweight and obese individuals in the population. Overweight and obesity can be classified in many ways, yet a simple but precise explanation is that energy intake exceeds energy expenditure and causes an energy imbalance over time,46 leading to the development of obesity (see Figure 33-6).

In developed countries such as Australia and New Zealand increased body mass has now become an epidemic problem. The United States has the greatest number of individuals who are classified as overweight or obese: it is estimated that up to 70% of the US population can be classified in these categories, with more than 5% being considered extremely obese.47 However, we are not far behind in Australia and New Zealand. For example, in Australia in 2005 approximately 60% of the population were either overweight or obese: 39.1% were classified as overweight and 20.5% as obese.46 More males were classified as overweight compared with females, but females were more obese than males. Worryingly, the number of overweight and obese adults in Australia has doubled since the 1980s.48 Children are not spared from the issue, with 25% of children classified as either overweight or obese, a significant increase since the 1970s.49

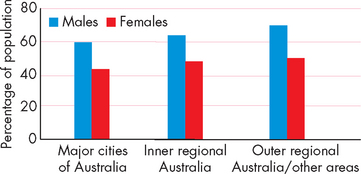

Despite the high rates of urbanisation in Australia and New Zealand, the proportion of people who are either overweight or obese is spread evenly between the urban and rural/remote areas (see Figure 33-7). This suggests that although urban populations have more access to takeaway foods and presumably undertake less physical activity related to employment, rural populations are equally likely to be obese or overweight.

FIGURE 33-7 Geographical distribution of overweight and obese individuals in Australia.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. National health survey: 2004–2005. Catalogue no. 4363.0.55.001. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2006.

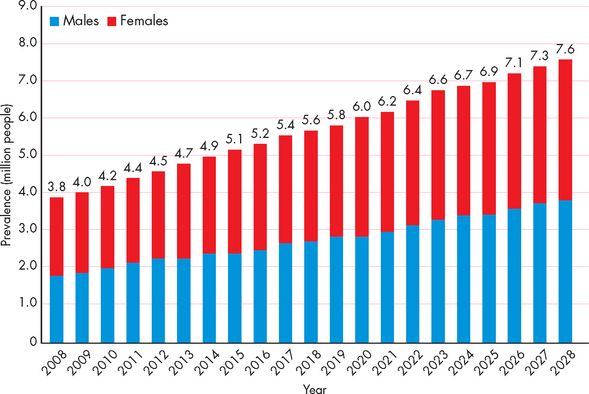

The number of people who are overweight or obese is likely to continue to increase. It has been estimated that almost 7 million Australians will be classified as obese by 2025 (see Figure 33-8).32 The prevalence of diseases associated with obesity will also continue to increase. Already in Australia some 300,000 excess hospitalisations due to cardiovascular-related conditions have been attributed to obesity.50

FIGURE 33-8 The projected increase in the prevalence of obesity in Australia until 2028.

Source: Access Economics. The growing cost of obesity in 2008: three years on: Report for Diabetes Australia. Canberra; 2008.

The high rates of obesity and overweight may be related to people’s perceptions of their body mass. Evidence is emerging that people do not consider themselves to be overweight or obese, despite calculations clearly showing that they are in the overweight or obese range. In fact, within the population who are either overweight or obese, almost half of men and about one-fifth of women consider their weight to be in the acceptable range.46,51,52 One reason for this may be the incremental increase in people’s weight over time: individuals often acquire excess body mass over months or years and so their perception of their weight gain is not as obvious.

To place it in pathophysiological terms, the building of excess body mass can be viewed as altered homeostasis. We can use a simple example to demonstrate this effect. If an individual has a normal blood glucose level but then ingests a high concentration of simple sugars, such as found in carbonated soft drinks, their blood glucose level will rise. If the individual does not readily use the glucose for energy requirements, the increase in blood glucose level will quickly be reduced with the release of insulin. In contrast, an overweight or obese individual gains more weight incrementally. In response to an intake of energy excess to the body’s needs at a particular meal, there is no correction such as a reduction in food intake at the next meal or an increase in energy expenditure. Over time, these small increases accumulate and the individual will eventually have a significant increase in body mass. The individual can be considered to be in a state of altered homeostasis, as no correction is readily available in the short term and the obesity may cause significant health problems. Figure 33-9 illustrates this example.

FIGURE 33-9 Altered homeostasis leading to overweight and obesity.

A An acute alteration in blood glucose level is counteracted by the release of insulin to restore the blood glucose level back to normal levels. This is an example of a negative feedback response and usually occurs in seconds to minutes. B The individual starts with normal body mass, but incremental changes in physical activity level and energy intake (type of food and portion sizes) can lead to increases in body mass. Over time, usually months to years, this imbalance in energy intake and expenditure can lead to overweight or obesity. This can be considered a semi-permanent homeostatic imbalance. If the individual can lose weight and return to a normal body mass, homeostatic balance will be restored.

Another consideration for overweight and obese individuals is the estimated reduction in their life expectancy. Studies have shown that if a younger adult is obese, the likelihood of premature death increases, although this is more strongly correlated with the severely obese.15,16,50 As the current obese population ages, the extent of the presumed reduction in life expectancy will become more apparent. It should be noted that this needs to be balanced against the advancements in medical technology and healthcare, which are projected to continue to improve in the future.

The last area that links the contemporary health issue of obesity with chronic disease is its impact on the pathogenesis of chronic diseases. We now have clear evidence linking obesity with disease development and progression.53 Based on the rates of obesity in the current population, it is estimated that obesity causes almost 25% of type 2 diabetes mellitus and osteoarthritis, and 20% of all cardiovascular disease, colorectal and breast cancer.32,48 In fact, there are strong links between obesity and a variety of diseases, with causal links discovered with the diseases listed in Figure 33-10.

DISEASES

Patients in acute-care hospitals in Australia and New Zealand are considerably different from those of 20 years ago. Patients now have more complex health problems and are more likely to require specialist care. Furthermore, they are statistically more at risk of developing problems during their hospital stay, such as infections, deep vein thromboses and cardiac events.

While cardiovascular disease remains one of the leading causes of death, other causes of death are increasing. This is directly related to the ageing population, with a projected increase in newly acquired cancers and deaths from cancer. The good news is that some cancers are on the decline. For instance, cervical cancer is likely to continue to decline, primarily due to the mass introduction of the human papillomavirus vaccine, Gardasil, which provides protection against human papillomaviruses thought to be responsible for 80% of cervical cancers in Australia. Also, lung cancer rates in males have been dropping, although unfortunately rates in women are projected to increase in the coming decades.23 The rates and types of cancers in the Australian and New Zealand populations are discussed more thoroughly in Chapter 36.

The other major disease that is likely to be encountered by healthcare professionals is diabetes mellitus. Rates of obesity are strongly related to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. It has been estimated that by 2050 approximately 14% of Australians (1 in 7) will have type 2 diabetes mellitus.54 Therefore, individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus will be very prevalent in the hospital patient population and associated healthcare services. Chapter 35 examines the links between obesity and diabetes mellitus.

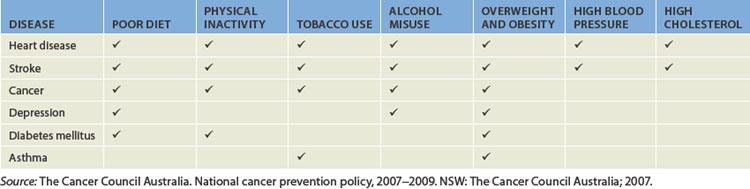

The risk factors for chronic disease are listed in Table 33-5.

Mental health

Until this point we have explored the pathophysiology of common diseases and disorders with mainly a physical origin. However, mental illness is known to have an enormous impact on contemporary health in Australia and New Zealand. For instance, it has been estimated that about 1 in 5 Australian adults will experience a mental illness over the course of their life. In comparison to other contemporary health issues such as coronary heart disease and cancer, mental illness affects more Australians and New Zealanders than any other disorder. It must be stressed that there are many different types of mental illness and often the diagnosis of individuals with a particular illness is difficult. Also, many of the illnesses are atypical, meaning that if you have to diagnose someone with a brain tumour a computed tomography scan is likely to show the tumour, yet in people with mental illness, diagnosis is primarily subjective, based on symptoms. However, the vast majority of people with mental illness do not require hospitalisation, but rather management of symptoms, which often occurs in the community. Yet the stigma associated with mental illness is frequently negative and the different types of mental illnesses are poorly understood. The majority of people with a mental illness have anxiety disorders that can often be successfully managed. In contrast, while only a small percentage of mentally ill people have a major psychotic illness, such as schizophrenia, the impact on the individual and their family can be devastating.

The aetiology of mental health is complex. There are many theories about the pathophysiology of these disorders and while many have limitations, these theories have greatly enhanced our ability to treat people with pharmacological agents. It has been shown that some mental illnesses are likely to have a strong genetic component; however, the effect of the environment is also strongly implicated. In recent years, advancements in neuroimaging have assisted in understanding the pathogenesis of mental illness. Therefore, Chapter 38 is entirely devoted to our current understanding of the neurobiology of mental illness.

INDIGENOUS HEALTH

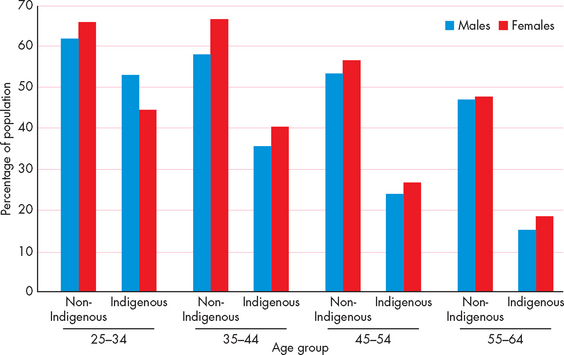

There is one group of people within the Australian population who have not been mentioned in detail thus far who have extremely poor health outcomes: Indigenous Australians. Compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts, Indigenous Australians are extremely disadvantaged, in terms of both morbidity and mortality. For instance, in the 1960s, the infant mortality rate among Indigenous Australians was one of the highest in the world. It has since declined dramatically, but it is still twice the rate of the non-Indigenous population.55 This disadvantage continues through to adulthood: for example, the life expectancy of an Indigenous male is approximately 17 years less than for non-Indigenous males.2 Unfortunately, this statistic has not improved significantly in the last 30 years.55

When comparing how individuals perceive their own health, Indigenous Australians’ self-rating of their health is considerably lower than that of non-Indigenous Australians (see Figure 33-11). Such self-rating demonstrates a person’s overall health and may be a predictor of life expectancy. This translates to the known health statistics: almost every health statistic is worse for the Indigenous population compared with the non-Indigenous population.56 For instance, the rates of kidney failure and of developing kidney failure as a result of diabetes mellitus are up to four times higher in Indigenous Australians compared with non-Indigenous Australians.57

FIGURE 33-11 Self-reported health ratings by Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health, 2008. Catalogue no. AUS 99. Canberra: AIHW; 2008.

These are just a few examples of the poor health status of the Indigenous population. In Chapter 39, we focus on diseases and conditions that are common to Indigenous Australians and the factors associated with these pathophysiological states.

GOVERNMENT INITIATIVES

We finish this chapter by briefly examining what the respective federal governments are attempting to do to ameliorate these massive health problems in Australia and New Zealand. The issues discussed in this chapter are well-known to governments and health departments, and a multitude of programs have been designed to increase the overall health of Australians and New Zealanders. For instance, both countries have national screening programs for breast and cervical cancers, and are developing bowel cancer screening programs as well.

The Australian government has identified a range of national health priorities that include diseases and conditions that cause significant morbidity to the community. The areas that have been highlighted include:

Complementing this approach is a national preventative health strategy to improve the health of Australians by 2020.58 This involves providing targets to reduce premature death and reduce morbidity. These targets are shown in Box 33.3.

Box 33-3 NATIONAL PREVENTATIVE HEALTH STRATEGY TARGETS

Source: National Preventative Health Taskforce. Australia: the healthiest country by 2020. National Preventative Health Strategy: overview. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009.

The New Zealand government has a similar approach and has published a wide range of objectives to improve the overall health of New Zealanders. The objectives are to:

ensure access to appropriate child healthcare services, including well child and family health care and immunisation.60

ensure access to appropriate child healthcare services, including well child and family health care and immunisation.60Describe some of the ways that government might attempt to increase the overall health status of the population.

Australia and New Zealand: demographics

The populations of Australia and New Zealand are small compared with most other countries: Australia and New Zealand are the 51st and 118th most populous countries in the world, respectively.

The populations of Australia and New Zealand are small compared with most other countries: Australia and New Zealand are the 51st and 118th most populous countries in the world, respectively. Urbanisation has influenced the prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease and asthma, with higher rates in the cities compared to rural and remote locations.

Urbanisation has influenced the prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary heart disease and asthma, with higher rates in the cities compared to rural and remote locations. Life expectancy in Australia is one of the highest in the world; New Zealand is not far behind in life expectancy rates.

Life expectancy in Australia is one of the highest in the world; New Zealand is not far behind in life expectancy rates. The aged population is projected to increase dramatically in the next 40 years, which will significantly impact on health services.

The aged population is projected to increase dramatically in the next 40 years, which will significantly impact on health services. In 2007 in Australia there were about 8 million hospital admissions. The average length of stay in hospital is 3.3 days, while the average length of stay for the 85 years and older age group is more than 6 days.

In 2007 in Australia there were about 8 million hospital admissions. The average length of stay in hospital is 3.3 days, while the average length of stay for the 85 years and older age group is more than 6 days.Contemporary lifestyle

Stress activates the sympathetic nervous system and causes a release of the hormones cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline, which can lead to organ dysfunction and the development and progression of disease.

Stress activates the sympathetic nervous system and causes a release of the hormones cortisol, adrenaline and noradrenaline, which can lead to organ dysfunction and the development and progression of disease.Obesity

Diseases

While there has been a decline in cardiovascular disease and cancer deaths over the last 20 years, these diseases remain the highest causes of death in Australia and New Zealand.

While there has been a decline in cardiovascular disease and cancer deaths over the last 20 years, these diseases remain the highest causes of death in Australia and New Zealand. The major diseases that contribute to mortality and morbidity and are likely to be encountered by healthcare professionals are obesity and diabetes mellitus. The rates of obesity are strongly related to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. By 2050, approximately 14% of Australians will have type 2 diabetes.

The major diseases that contribute to mortality and morbidity and are likely to be encountered by healthcare professionals are obesity and diabetes mellitus. The rates of obesity are strongly related to the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. By 2050, approximately 14% of Australians will have type 2 diabetes.Max is 75 years old. He lives in the country and is married to Jess (who is 73 years old), has 4 children and 7 grandchildren. He has never smoked, drinks 2 beers every Friday evening with his mates at the local hotel, eats a nutritionally balanced diet and is a normal weight for his height. He worked in a timber mill for all of his working life and was physically active, playing sport regularly until recently. His eldest son, John, aged 54, has just been diagnosed with coronary heart disease with an 8-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus. John is obese. His siblings are overweight but have not been diagnosed with any diseases.