39 INDIGENOUS HEALTH ISSUES IN AUSTRALIA

INTRODUCTION

Indigenous Australians have a range of major health problems that directly impact on morbidity and mortality. One of the easiest ways to measure health status and health outcomes of Indigenous peoples is to compare against the non-Indigenous population. In almost every measure of health the differences are stark, with Indigenous people experiencing disadvantages in health across almost all age groups. Moreover, on a global scale, the health of Indigenous Australians is worse than that of other Indigenous peoples. The reasons for the poor health outcomes of Indigenous Australians are complex. Clearly, the effects of colonisation have significantly contributed to the development of disorders and diseases in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. This has led to a range of social, economic and cultural disadvantages which really have not significantly changed over several decades. However, the greater prevalence of disease and disorders compared with other Indigenous populations suggests that the poor health is multifactorial. There are no simple answers to explain the reasons for the current state of Indigenous health. This chapter does not have the answers, but rather is an overview of the contemporary Indigenous Australian health status, with a focus on pathophysiology. It should be stressed that in many cases the reasons for the increased incidence and prevalence of disease and disorders compared to non-Indigenous Australians are simply not known.

We commence this chapter with an exploration of the Indigenous population and the epidemiology of Indigenous health. The chapter details the pathophysiology of conditions that afflict the Indigenous population and highlights the prevalent differences compared with the non-Indigenous population, which then can be used to demonstrate the difference in health outcomes. In addition, and to gain a greater insight into a complex problem, several boxes provide a uniquely Indigenous perspective on lifestyle and health determinants. These have been included so the reader may gain a better understanding of Indigenous Australians.

THE INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIAN POPULATION

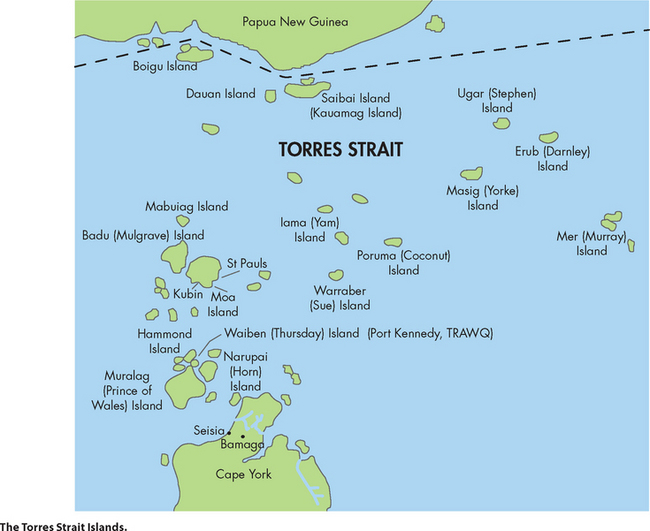

It is appropriate from the outset to define what is meant by the term Indigenous. The word is derived from the Latin ‘indigena’ meaning ‘native’ (originating and living in a particular geographical region). Therefore, the Indigenous Australian population refers to the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands, and their descendants. There are two Indigenous populations: Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islander people. Aboriginals are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands and their descendants, while Torres Strait Islander people are the original inhabitants of the Torres Strait Islands and their descendants. It is important to remember that the cultures of the Aboriginal and the Torres Strait Islander peoples are very different from each other, and unique. This is explored in more detail in the section on social determinants below.

It has been reported that there are approximately 370 million Indigenous people worldwide.1 In 2006, it was estimated that the Indigenous Australian population was approximately 517,043 — 2.5% of the Australian population.2 Of the Indigenous population, the majority (90% or 463,700) were of Aboriginal origin, with 6% (33,090) of Torres Strait Islander origin and the remaining 4% (20,100) of both origins.3 Although, the absolute number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders in Australia is relatively small, the growth rate has been more than double that of the non-Indigenous population, increasing by 2.6% per year between 2001 and 2006, compared to the total Australian population increase of 1.2%. This growth rate is expected to continue and is projected to increase by 2.2% over the next decade, with the total Indigenous population reaching 721,000 by 2021.2

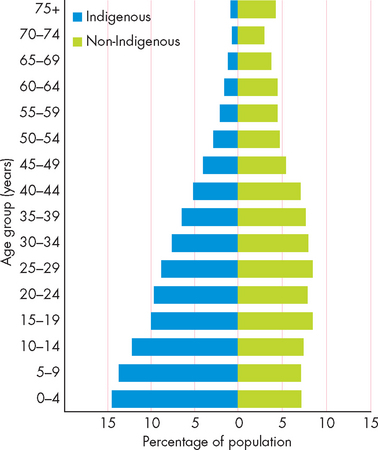

There are also differences in the number of individuals within different age groups between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the non-Indigenous population (see Figure 39-1). The median age of the Indigenous population is 21 years compared to 37 years for the non-Indigenous population. Thirty-eight per cent of Indigenous people are under the age of 15 years compared to 19% of non-Indigenous people, and only 3% of Indigenous people are aged over 65 years of age, with 13% for the non-Indigenous population.4 Therefore, there is a lower percentage of older Indigenous people and a disproportionately higher number of younger Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts (see Figure 39-1). It has been estimated that the percentage of the Australian aged population will increase in the future, with projections that the number of people over the age of 65 years will comprise 25% of the total population by 2050, up from 12% in 2009.4 In contrast, the Indigenous aged population is smaller, due primarily to their lower life expectancy. As a result, the ageing non-Indigenous population and the younger Indigenous population may see more differences in their health status in the future. Furthermore, although non-Indigenous Australians often succumb to diseases as they age, the Indigenous population may experience diseases at younger ages.

FIGURE 39-1 Population pyramid of Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Experimental estimates and projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 1991 to 2021. Catalogue no. 3238.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2009.

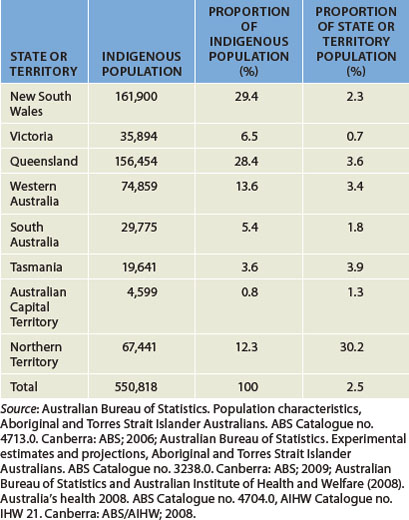

The majority of Torres Strait Islander people live in Queensland and while New South Wales has the largest number of Aboriginal Australians (148,200), the Northern Territory has a greater proportion of Indigenous people (see Table 39-1).2 Interestingly, while a large number of Indigenous Australians live in metropolitan regions (32% of total Indigenous population), a greater proportion of the Indigenous population resides in remote regions when compared to non-Indigenous Australians (see Figure 39-2).4 As we will see, this can impact on Indigenous health, as access to health services can be limited and difficult in these regions.

FIGURE 39-2 Indigenous population distribution.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population characteristics, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. ABS Catalogue no. 4713.0. Canberra: ABS; 2006.

From an Indigenous person’s perspective, Australia is made up of hundreds of different nations. ‘Nation’ refers to the geographical extent of the land inhabited, and also to where family members may have come from originally. Queensland is unique as both Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander communities are located within the state (see Box 39-1).

BOX 39-1 INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE: AUSTRALIA

It is vital to note that each Aboriginal nation and each Torres Strait Islander tribe is unique. Some practices and languages are similar, but never assume that customs and lore are the same across nations. Australian Aboriginal nations may share similarities in language or customs, but each nation has its own identity, as do the nations of Europe. And in the same sense, Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders consider themselves two distinct Indigenous populations of Australia.

INDIGENOUS HEALTH

Generally, the health status of Indigenous Australians is very poor, when compared to other groups within the population. There are many glaring health statistics that highlight the huge gap in health outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. However, one statistic summarises the massive difference between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health — life expectancy. As of 2010, life expectancy for Indigenous Australians was approximately 17 years lower than that for the total Australian population. The life expectancy of Indigenous males was only 59 years, which was 20 years less than that of their non-Indigenous counterparts, and for Indigenous females it was 17 years less than their non-Indigenous counterparts (65 years compared with 82 years). This factor alone demonstrates that there is a massive divide in health outcomes of Indigenous Australians compared to the non-Indigenous population.

Furthermore, there are differences in life expectancy for Indigenous people according to geographical location. The life expectancy of the total Indigenous population is lowest in the Northern Territory (61.5 years) and highest in NSW (69.9 years).2 There are likely to be many reasons for this, such as social, economic and living standards. Nonetheless, there remains a large discrepancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health status in Australia today.

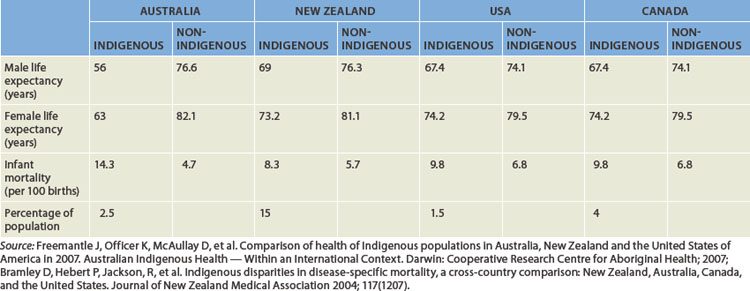

The large disparity in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians can be compared to the situation in other countries where colonisation has also had a negative impact on the lifestyle and health of the Indigenous populations. The difference in life expectancy in these countries may also be large and this can be contextualised against the Australian situation. The health status of Indigenous populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States and the northern European countries has been the most widely documented. One commonality between the Indigenous populations is that typically their health outcomes, such as morbidity rates, are inferior to that of their non-Indigenous counterparts. For instance, when compared to the non-Indigenous population of their respective countries, New Zealand Maori have higher rates of death arising from coronary heart disease and malignant neoplasms,5 Canadian First Nation peoples are at greater risk of death from pneumonia and influenza,5,6 and North American Indians have 2.5 times higher rates of developing end-stage kidney disease.7 But in almost every study published, Indigenous Australians have poorer health outcomes compared to their Indigenous counterparts from other countries (see Table 39-2). The reasons for this are unclear but researchers have considered historical, sociopolitical and cultural differences to be the most likely causes.8

Table 39-2 HEALTH DIFFERENCES BETWEEN INDIGENOUS AND NON-INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS THROUGHOUT THE WORLD

The health picture of an Indigenous individual prior to colonisation would have been contingent on a range of factors. For instance, in times of drought, infant mortality may have increased as ready access to water would have been more difficult. Moreover, injury due to physical trauma may have been experienced by individuals as a result of the nomadic lifestyle. For instance, environmental exposure may have caused skin trauma. In contrast, while infectious diseases arising from trauma, such as skin infections, are likely to have occurred, it is unlikely that infectious diseases transmitted through large sections of an urban population, such as influenza, would have been experienced by the Indigenous population. It should be stressed that evidence supporting these situations prior to colonisation is lacking; nevertheless, the overall health status of the Indigenous population today is poor compared with that of the non-Indigenous population. The incidence of many diseases and disorders in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders today is very high, by both Australian and international standards.6,9–11 4 6

For instance, the rate of mortality from cardiovascular disease is twice that of the non-Indigenous population.12 Moreover, Indigenous people are more likely to die due to conditions that are treatable, such as diabetes or pneumonia.12 Therefore, coupled with social problems such as homelessness, nutritional deficiencies and economic disadvantage, Indigenous health is poorer than their non-Indigenous counterparts.

Mortality

In Australia in 2007, there were approximately 143,900 deaths — a rate of 6 deaths per 1000 people.13 In the same period, there were just over 2400 Indigenous deaths.13,14 However, despite the large absolute numerical difference, the death rate across all specific age groups was far greater for the Indigenous population.2 It has also been reported that many deaths are not registered as Indigenous and, therefore, the rate would actually be higher.15 As mentioned earlier, the life expectancy of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders is considerably less than that of other Australians and this is demonstrated in Figure 39-3.

FIGURE 39-3 Mortality rate of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians by age groups.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Deaths, Australia, 2008. Catalogue no. 3302.0. Canberra: ABS; 2007.

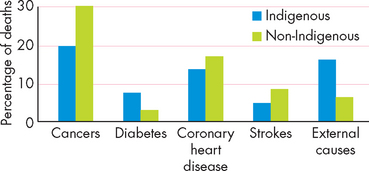

The most common cause of Indigenous deaths was from cardiovascular disease, including coronary heart disease and stroke. It accounted for 26% of all Indigenous deaths (see Figure 39-4).16 Total Indigenous cancer deaths were less than non-Indigenous cancer deaths; however, the median age of death from all types of cancer was 63.1 years for Indigenous people and 75.5 years for other Australians, which means that on average Indigenous people with cancer die at a much younger age.16 In contrast, deaths arising from diabetes and external causes were more numerous than those of the non-Indigenous population. External causes were mainly attributable to intentional self-harm (suicide), motor vehicle accidents and assaults.

FIGURE 39-4 Causes of death of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Causes of death, Australia, 2005. Catalogue no. 3303.0. Canberra: ABS; 2008.

BOX 39-2 INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE: EARLY HEALTH STATUS

Although there is little quantitative data on diseases in Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander populations prior to European contact, some accounts of early contact by Europeans reported the Indigenous population as fit and lean.

It is a commonly held Indigenous perspective that Aboriginal Australians were, at the time of colonisation, a fit and healthy race of people. The Indigenous oral tradition of passing on history shows that the community was functional and people undertook physical exercise such as hunting and gathering and preparation of food, as well as ceremonial activities.

While Aboriginal health was not perfect, the style of living was more in tune with the environment in which people lived. Their diet included lean meats, fish, traditional vegetables and fruits. Acquiring food by hunting and gathering was often a labour-intensive activity. People lived on their country and accepted the responsibility of caring for their country, such as protecting water holes and sacred sites. People lived in harmony with their environment, using the land’s resources in a way that protected those resources. Waste disposal was not a major issue because of the nomadic lifestyle and the lack of non-biodegradable products. The Indigenous perspective is that the current health differentials between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians are a direct result of colonisation.

Source: O’Dea, K. Preventable chronic diseases among Indigenous Australians: the need for a comprehensive national approach. Heart, Lung and Circulation 2005; 14:167–171; Bartlett, B. An Aboriginal health worker’s guide to family, community and public health. Alice Springs: Central Australian Aboriginal Congress Publication; 1995.

BOX 39-3 INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE: DEFINITION OF HEALTH

The Indigenous perspective of health is different from Western definitions of health. This can be illustrated by the National Aboriginal Health Strategy definition which states that health is, ‘not just the physical well-being of the individual but the social, emotional and cultural well-being of the whole community’.

In contrast, the World Health Organization emphasises the individual and states that health is ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’.

The important distinction between the two health definitions is the inclusion of cultural/spirituality wellbeing in Indigenous health. Every aspect of an Indigenous person is regarded as equally important; that is, the biological, psychological, sociological, spiritual and the communal. The Indigenous definition includes spirituality in health as the continuous cycle of life–death–life. The inclusion of community is also important in the Indigenous perspective.

Source: National Aboriginal Health Strategy (NAHS). National Aboriginal Health Strategy working party report, Australia: AGPS; 1989; World Health Organization. www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html/.

Infant mortality

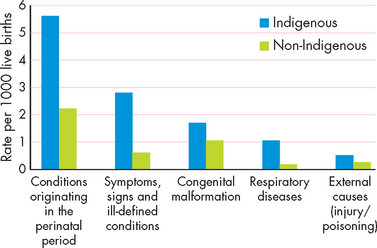

In Australia in the last 100 years the infant mortality rate (i.e. the rate of infant death during the first year after a live birth) has declined significantly. In the early 1900s, the infant mortality rate was estimated to be 81.8 infant deaths per 1000 live births, but in 2007, the rate was 4.2 infant deaths per 1000 live births, which is one of the lowest in the world.13 In contrast, the Indigenous infant mortality rate was 12.7 infants per 1000 live births, with the highest rate in the Northern Territory of 14 per 1000 live births.14,15,17 Note that the Australian infant mortality rate has declined over the last three decades but the decline in the Indigenous population has been considerably less. The main causes of infant mortality include complications of pregnancy, labour and delivery, which accounted for almost half of all infant deaths. Symptoms, signs and ill-defined conditions include sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) accounting for 22% of deaths compared with a rate of 6.7% in the total Australian population. Congenital malformations also made up 12% of Indigenous infant mortality. Finally, respiratory diseases and external causes (accidents) accounted for 12% of all Indigenous infant deaths (see Figure 39-5).

Morbidity

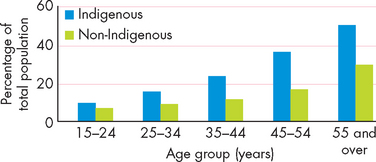

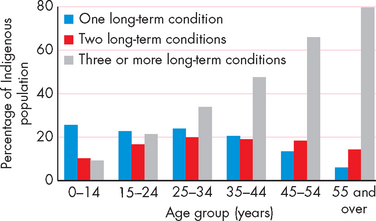

While the life expectancy is lower and the mortality rate arising from many diseases is greater in Indigenous people, when compared to other Australians, the Indigenous population also has high levels of poor health. For instance, the long-term health of the Indigenous population has been shown to be poor. Surveys have shown that long-term health conditions are prevalent in Indigenous people with 65% of the Indigenous population having at least one long-term health condition.18 The older Indigenous population is affected more, with almost every Indigenous person over the age of 55 years reporting at least one long-term health condition (see Figures 39-6 and 39-7). Interestingly, Indigenous people living in remote areas had fewer long-term health problems compared with non-remote or predominantly urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. Although remoteness does not necessarily predict poorer health, it should be remembered that limited access to health services can affect the morbidity of this population.

FIGURE 39-6 Fair or poor self-assessed health in Indigenous and non-Indigenous people aged 15 years and over.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey Australia 2004–05. ABS Catalogue no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS; 2006.

FIGURE 39-7 Number of long-term health conditions reported by Indigenous people.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey Australia 2004–05. ABS Catalogue no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS; 2006.

Hospitalisation rates and the reasons for hospitalisation provide an insight into the magnitude of poor health of a population. There were over 270,000 episodes of hospitalisation in Australia for Indigenous people in 2008. Overall, the hospitalisation rate was 2.6 times higher than that of the non-Indigenous population, but the rate is contingent on location. For instance, the hospitalisation rate in the Northern Territory is 7.3 times higher than non-Indigenous hospitalisations.19 The most common cause of hospitalisation was for dialysis treatment (see ‘Chronic kidney disease’ below), with injury/poisoning and other consequences of external causes and pregnancy-related causes the next most common reasons.20

Fertility

The fertility rate in young Indigenous females is higher than in the non-Indigenous population, with an estimated rate of 2.1 babies per female compared with a national fertility rate of 1.8 babies for all Australian females.2 There are more teenage births, estimated to be five times greater in Indigenous females. This lowers the average Indigenous maternal age group to between 20 and 24 years compared to between 30 and 34 years in non-Indigenous females.2

In addition, Indigenous females often have babies with a low birthweight.21 This is defined as a birthweight of less than 2500 grams. On average, babies born to Indigenous females weigh about 200 grams less than non-Indigenous babies.2,15 This factor has been shown to be improving, especially in rural and remote regions of Australia.21

DISEASES AND DISORDERS

There are numerous diseases and disorders that are common in both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations. However, in many cases the prevalence rates are higher within the Indigenous population. In some instances, the prevalence of diseases and disorders are so high in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people that the rates are comparable to those in developing countries. The following section details some of the main diseases and disorders, highlighting the difference in prevalence and incidence rates but also providing current knowledge of the pathogenesis, risk factors and conditions that lead to these altered states. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to comprehensively detail every disorder, as these have been covered in previous chapters throughout Parts 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Cardiovascular disease

Most cardiovascular conditions occur at higher rates in the Indigenous population than in the non-Indigenous population. It has been reported that 1 in 8 Indigenous Australians has a long-term cardiovascular condition.22,23 This equates to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people having 1.3 times the rate of cardiovascular disease compared to the non-Indigenous population.22 In particular, while coronary heart disease, stroke and hypertension are higher, the rates of rheumatic heart disease also contribute significantly to an increased cardiovascular mortality rate in the Indigenous population, whereas it is a rare cause of death in the non-Indigenous population. This is primarily related to acute rheumatic fever in childhood — almost non-existent in the wider Australian community.24

Risk factors associated with cardiovascular disease are more common in Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders, with more than half of the total Indigenous population having more than three risk factors, such as daily smoking, inactivity, poor diet, high alcohol consumption, obesity, diabetes, hypertension and chronic kidney disease.22 That many of these risk factors are modifiable demonstrates that current healthcare does not meet the needs of the Indigenous community with regard to cardiovascular disease. Health interventions targetting disease prevention are required to address the particular requirements of the Indigenous population to reduce the high rate of cardiovascular disease.22

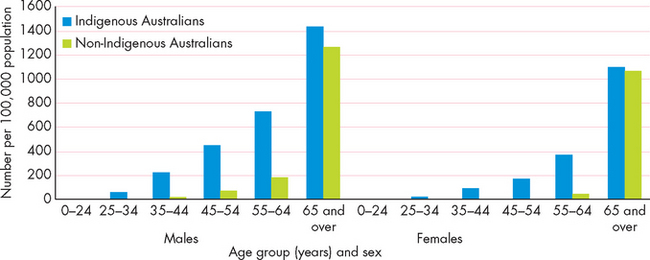

Coronary heart disease

As with the non-Indigenous population, coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; however, the Indigenous rate is three times higher.22,24 Furthermore, across all age groups, the death rate arising from cardiovascular disease is higher (see Figure 39-8).22,24 There is a wide disparity in coronary heart disease events, such as acute myocardial infarction or angina pectoris, between urban Aboriginals and urban non-Aboriginals. It has been calculated that there is a six-fold increase in such events in the urban Aboriginal population, and that such events are more than 20 times likely to occur in urban Aboriginal women aged 45–54 years.25 The findings from this study suggest that the cardio-protection from coronary heart disease usually found in women aged less than 60 years of age is not conferred in Aboriginal women. This is an area of ongoing research.

FIGURE 39-8 Death rate from coronary heart disease in Indigenous and non-Indigenous males and females by age groups.

Note the large increase in coronary heart disease mortality between 35 and 55 years for both Indigenous males and females.

Source: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Penm, E. Cardiovascular disease and its associated risk factors in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2004–05. Cardiovascular disease series no. 29. Catalogue no. CVD 41. Canberra: AIHW; 2008.

Vascular inflammation and endothelial activation are mediators that are associated with increased coronary heart disease risk in Aboriginal people. The change in lifestyle which results in physical inactivity and poor diets may be linked to these pathophysiological processes.26 Dyslipidaemia is also a major problem among Indigenous people leading to coronary heart disease. The profile of lipids includes more elevated levels of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) and lower levels of high-density lipoproteins (HDL) than in non-Indigenous people. This profile is more pronounced in diabetic Indigenous people.27

Coronary heart disease has been shown to be an inflammatory process that usually progresses over years to decades (see Chapter 23). In Indigenous people, carotid intima-media thickness has been shown to be associated with non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as albuminuria and C-reactive protein, a marker of inflammation.28 It is hoped that this area of research will allow for earlier detection of coronary heart disease and better diagnosis.

One of the reasons why Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with coronary heart disease have greater mortality rates relates to the number of co-morbidities. It has been found that when Indigenous people are hospitalised for coronary heart disease they have more co-morbidities than their non-Indigenous counterparts. In fact they are 2.5 times more likely to have three or more co-morbidities, which will increase the complexity of the coronary events.22 The most common co-morbidity is diabetes, with up to 45% of the Indigenous population who are hospitalised for coronary heart disease having the condition.22 The Framingham study — which produced equations that estimate coronary heart disease risk — is widely used in Australia as a basis for cardiovascular risk. When applied to Aboriginal people, the traditional risk factors of age, sex, cholesterol, HDL, blood pressure, diabetes and smoking underestimate the risk of coronary heart disease, especially in women and younger adults.29 This suggests that the traditionally accepted risk factors may influence Indigenous people differently or that other risk factors may have a greater effect on coronary heart disease risk.

With respect to treatment options, Indigenous Australians with coronary heart disease do not have the same intervention rate as non-Indigenous people. For instance, percutaneous coronary intervention (see Chapter 23), a reasonably standard procedure for the treatment of coronary heart disease, occurs 40% less often in Indigenous people.30,31 Moreover, Indigenous people are 20% less likely to receive coronary artery bypass graft surgery, which has been shown to extend life expectancy in individuals with coronary heart disease.

Stroke

As with other cardiovascular diseases, the prevalence of stroke and mortality arising from stroke is higher in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared to the rest of the Australian population. While precise statistics are not available, it is thought that the death rate from stroke is double that of non-Indigenous people and occurs in younger Indigenous people.32 Of all cardiovascular conditions, stroke deaths occur in 1 in 7 Indigenous males and 1 in 5 Indigenous females.15

Haemostatic processes, ones that are involved in clot formation, are important indices of cerebrovascular events, such as stroke. Elevated levels of fibrinogen circulating in the bloodstream are a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In Indigenous people with high risk of stroke, fibrinogen levels are higher than in the wider Australian community.33

Rheumatic heart disease

Acute rheumatic fever occurs due to a delayed reaction to bacterial infection, primarily group A beta (β)-haemolytic streptococcus. Acute rheumatic fever usually begins in childhood, but people can experience reoccurrence well into adulthood. When the acute phase is present, individuals experience febrile states with joint, skin and nervous system inflammation.34 However, if rheumatic fever is not treated it can cause scarring of cardiac tissue, specifically the heart valves, resulting in rheumatic heart disease.34–36 4 6

It is known that rheumatic fever occurs in susceptible individuals and that only some people exposed to group A streptococcus develop acute rheumatic fever.36 Therefore, it is thought that about 3–5% of the population has a higher risk of developing acute rheumatic fever. In the Indigenous population, the group A streptococcus that causes skin infections may increase the risk of developing acute rheumatic fever.37

Of the individuals that develop acute rheumatic fever about 10% will go on to develop rheumatic heart disease. The bacteria directly affect the endocardium and cause inflammation of the valve leaflets leading to clumps of vegetation and eventual scarring.

The incidence of acute rheumatic fever is now rare in the Australian community. This is a result of improvements in living conditions and medical care which treats the disease early. However, the rates of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease are high in the Indigenous community, especially those in the Northern Territory, central Australia and remote areas. When adjusted for age, the prevalence of rheumatic heart disease for Indigenous Australians is almost 35 times higher than in their non-Indigenous counterparts.22 Moreover, Indigenous Australians are almost 20 times more likely to die from acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease than other Australians.

Indigenous populations, especially children, are at increased risk of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. There are associations with poor living conditions, inadequate hygiene practices, overcrowding and inappropriate sanitation. Educational attainment and lack of access to medical care have also been suggested as contributing factors.22,34–36 4 6

Mitral regurgitation is the most common valvular disorder arising from rheumatic heart disease. In Indigenous children less than 10 years old, 90% will have mitral regurgitation,36 although individuals may have mitral stenosis, aortic regurgitation and aortic stenosis (see Chapter 23).

The evaluation of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease is often difficult as the signs and symptoms are non-specific. However, the use of B-cell antigen D8/17 markers has been shown to be a specific and sensitive marker of rheumatic fever and could be used as a diagnostic test in Aboriginal communities.37 The treatment of acute rheumatic fever is an antibiotic regimen of penicillin or erythromycin with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to treat inflammation. In severe cases of rheumatic heart disease, valve replacement surgery is required.

Diabetes mellitus

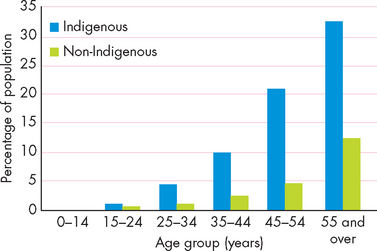

The prevalence of diabetes, especially type 2 diabetes mellitus, is high in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population (see Figure 39-9). The overall rate of diabetes is 3.4 times greater than in the non-Indigenous population; however, certain Indigenous groups have even higher rates.2 For instance, the rate of diabetes is 4.1 times higher in females, and in remote areas the rates are even higher. Moreover, due to difficulties with diagnosis and access to healthcare facilities with adequate testing capabilities, it has been estimated that for every one Indigenous individual identified with diabetes there is another who is yet to be diagnosed.20 Therefore, the real prevalence of diabetes has been estimated to be as high as 30% of the total Indigenous population, although this has yet to be corroborated.38

FIGURE 39-9 Prevalence of diabetes associated with hyperglycaemia in Indigneous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Note the large increase associated with the 25 years and up Indigenous age groups compared with the non-Indigenous population.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2008. ABS Catalogue no. 4704.0, AIHW Catalogue no. IHW 21. Canberra: ABS/AIHW; 2008.

While the exact causes of an increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Indigenous population has yet to be established, it has been suggested that the establishment of deleterious Western lifestyle features or genetic influences may have major impacts (see Figure 39-10). Genetic influences have been proposed in the development of diabetes in Indigenous populations throughout the world, with the ‘thrifty gene’ being implicated.39 Briefly, the ‘thrifty gene’ hypothesis proposes that traditional hunter-gatherer societies experienced periods with food abundance (feast) and famine. During times of food abundance, the thrifty gene caused an increase in fat deposition which was protective and increased survival when the societies experienced famine. However, with exposure of the traditional hunter-gatherer societies to a constant food supply, coupled with the Western diet that often consists of a high intake of energy-dense foods, the storage of fat was dominant and without periods of famine, obesity developed in these societies. It has also been argued that the thrifty gene can cause rapid weight gain and possibly diabetes, as the association between obesity and the development of type 2 diabetes is high. In fact, world-wide, traditional hunter-gatherer societies which have been exposed to colonisation, such as Aboriginal Australians, tend to have higher rates of obesity, increased waist-to-hip ratios and glucose intolerance.40,41

FIGURE 39-10 An overview of the risk factors associated with the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

In addition, genetic susceptibility to diabetes is thought to be involved in the pathogenesis42 and epidemiological evidence suggests that genetic factors may play a role in the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Australian Aboriginals.43 There have been discoveries of genetic markers in Indigenous populations throughout the world, such as the Pima Indians who have been found to have altered rates of glucose metabolism due to altered gene expression.44 In the largest genome-wide scan of Australian Aboriginals it was found that type 2 diabetes mellitus may be associated with a particular location on chromosome 2, chromosome 2q.43 While this is a preliminary result, it would greatly assist the developing therapies and strategies to be able to identify individuals at risk of developing the disease.

However, others believe that environmental factors, such as diet and sedentary lifestyle, are primarily responsible, with genetic predisposition playing a lesser role.45 For instance, historical records indicate that the first Indigenous individual diagnosed with diabetes was as recent as 1923.46 Others argue that the feast–famine cycles which are integral to the thrifty gene hypothesis were not likely to be as severe as indicated and that genetic influences could not have arisen from the phenomena.47 Whether genetic or environmental factors are dominant is currently unknown, and debate continues as to the influence of these factors (see Chapter 37 for a discussion on genetic and environmental factors).48 However, there are several salient points which are pertinent to the development of diabetes in Aboriginal communities.

A high proportion of Aboriginal Australians with diabetes mellitus are either overweight or obese.38,49–51 4 6 These factors are some of the strongest predictors of risk for the development of diabetes and in many individuals the development of metabolic syndrome is a link between obesity and the onset of diabetes (Chapter 35). Moreover, there are strong relationships between hyperinsulinaemia and body mass index (BMI), and impaired glucose tolerance and raised cholesterol and triglyceride levels and these were found in individuals under 40 years of age.38 This strongly suggests that lifestyle factors are likely to impact more negatively on the Indigenous population than they do on the wider Australian population. However, the greater prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Indigenous Australians may result from either genetic or environmental influences, such as Western-centric diet and lifestyle habits, or a combination of both. Nevertheless, it appears that risk factors significantly increase the development of diabetes in the Indigenous population, to a greater extent than in the non-Indigenous population.52 The exact reasons for this are unknown.

To date, there is limited evidence about the reduction of risk factors related to diabetes in Indigenous Australians. It has been suggested that amending the diet and lifestyle of an Aboriginal community from a Western style to a traditional one may reduce risk factors for diabetes, such as fasting glucose levels of the diabetic participants.53 Also, the development of obesity was strongly related to the onset of diabetes in central Australian Aboriginal communities,54 suggesting that diet strongly influences Indigenous peoples’ risk of obesity and diabetes. However, more evidence is required to fully explain the pathogenesis of diabetes in Indigenous Australians.

Aboriginal Australians develop impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes at a lower body mass index (BMI) than do their non-Indigenous counterparts; thus it has been suggested that a lower BMI should be used when assessing this group.55 The overall prevalence of diabetes mellitus type 2, adjusted for age and sex, is 15%, which is similar to that for American Indians and Canadian Inuit people, but lower than for Micronesian people and Pima Indians.55 This suggests that Australian Aboriginals, at least those living in remote regions, are at a greater risk of developing a diabetes profile, as the rates of obesity and impaired glucose tolerance are greater for a given BMI compared to the non-Indigenous population.

Cancer

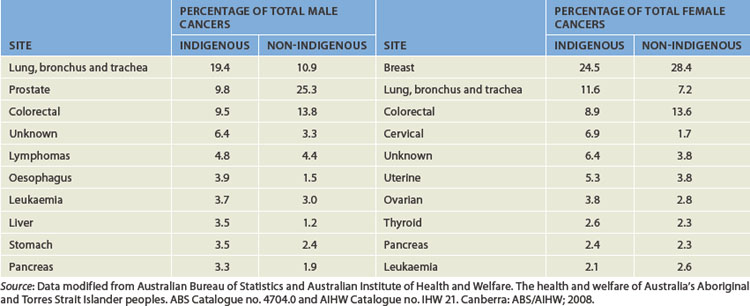

The risk of developing cancer increases with age across the Australian population (see Chapter 36). This is similar to the Indigenous population risk. However, in this population the risk of developing cancer escalates from an earlier age, as is evident by the young age mortality due to cancer in the Indigenous population.56–58 4 6 Interestingly, the prevalence of cancer in Indigenous Australians is quite mixed compared to the non-Indigenous population.15,58 Lower rates of melanoma, prostate, female breast and colorectal cancer are evident in the Indigenous population. In contrast, lung, oesophageal, liver, uterine, cervical and pancreatic carcinoma are higher than in the non-Indigenous population (see Table 39-3). It should be noted that the incidence rate of Indigenous cancers has been disputed and therefore differences that currently exist with the non-Indigenous population may not be evident. This is due to poor reporting and inadequate identification of Aboriginals with cancer.57

In contrast to the incidence and prevalence of Indigenous cancers, overall cancer mortality rates are higher when compared to other Australians.57 However, there are some cancers that have lower Indigenous mortality rates, such as colorectal, stomach and melanoma.56 There are many reasons for higher overall cancer mortality rates: later diagnosis due to lack of access or lower participation in screening activities; poor compliance with treatment; lack of appropriate resources; poor and inconsistent relationships between Indigenous communities and cancer organisations.58 Therefore, even though there are lower rates of some cancers in the Indigenous population, early screening programs, diagnoses and treatment options may be utilised less, thus contributing to the adverse outcomes for the Indigenous population.

In addition, the risk factors that are experienced by Indigenous Australians are more pronounced than those experienced by the total population. For instance, Indigenous Australians are 2.2 times more likely to be daily smokers, 1.1 times more likely to consume high levels of alcohol and they generally have poorer diets (less fruit and vegetable).57 Furthermore, obesity and sedentary lifestyles, lower socio-economic status and a high proportion of Aboriginals residing in rural and remote areas are all reported to contribute to higher cancer mortality.57,58 These factors are discussed later in the chapter.

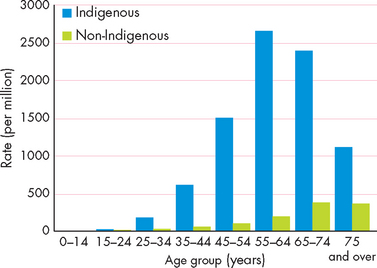

Chronic kidney disease

Chronic kidney disease affects many Australians, with an estimated 1 in 7 adults having at least one clinical sign (such as proteinuria or increased serum creatinine) of the disease (see Chapter 30).59 However, it is often undetected as symptoms usually do not become evident until 90% of renal function is impaired. The widest population-based study, the Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle (AusDiab) study, conducted in 1999–2000, examined the prevalence of diabetes, obesity, hypertension and chronic kidney disease in Australia.60 It was followed by a 5-year survey in 2004–2005 that tracked the prevalence and incidence of the diseases.61 Collectively, these studies have found that 16% of Australian adults have chronic kidney disease, and that 1% of Australian adults develop chronic kidney disease yearly. In addition, people with hypertension and diabetes increase their risk of developing chronic kidney disease.59–61 4 6 The prevalence of chronic kidney disease is estimated to be much higher in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

End-stage kidney disease, the last stage of chronic kidney disease, occurs when kidney function is reduced and the individual requires kidney replacement therapy in the form of transplantation or dialysis. As with other diseases, Indigenous Australians have a significantly higher incidence of end-stage kidney disease than do non-Indigenous Australians.59 End-stage kidney disease is one of the most serious diseases in the Australian Indigenous population. The overall prevalence rate is nine times higher in Indigenous populations than in other Australians (see Figure 39-11) but has been estimated to be up to 100 times greater in some Indigenous communities.53,59,62 The impact on the Indigenous population is large, with dialysis the most common reason for hospitalisation in 2008. This accounts for almost half of all Indigenous hospitalisations per year and Indigenous people are 12 times more likely to be hospitalised for dialysis compared to non-Indigenous people.20

FIGURE 39-11 The prevalence of end-stage kidney disease in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: McDonald S, Excell L, Livingston B. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry: the thirty-first report. Adelaide: Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry; 2008.

Traditional medicines

While many traditional medicinal practices have been lost there are still traditional practices that have continued unbroken for many thousands of years. These medicines are real to the many Indigenous peoples who utilise them and are part of self-identified healing practices. While they may not comply with Western practices they are still a vital part of the lives of many older Indigenous peoples.

Aboriginal communities have their own traditional medicinal practices that have been effectively administered over the generations. Colonisation has reduced the use of these practices; however, some were found to be effective when used by European colonisers. For example, Aboriginal patients with lacerations and fractures occasionally arrived at early hospitals with ‘antbed’ plasters on their wounds. These plasters were made of materials from antbeds in the countryside. Though often removed they were found to be effective at reducing infection when left in place. Subsequent testing demonstrated antimicrobial properties.

There are numerous other examples of Aboriginal pharmacopoeia. These include the use of pawpaw leaves in the Torres Strait for bathing and treating the symptoms of chickenpox. In many parts of Australia Aboriginal mothers use witchetty grubs to rub on the gums of teething babies as a mild anaesthetic.

Source: Devanesen D. Traditional Aboriginal medicine practice in the Northern Territory, International Symposium on Traditional Medicine, Awaji Island, Japan, 2000; Hunter E. Aboriginal health and history: power and prejudice in remote Australia. Hong Kong: Cambridge Press; 1993.

The death rate in the Indigenous population arising from chronic kidney disease is alarming. By comparison with their non-Indigenous counterparts, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander males are 7 times more likely to die from chronic kidney disease and female deaths are 11 times more common.63 When the 45–54-year-old age group is selected, the mortality rates from chronic kidney disease in Indigenous males and females are greater than 50 and 30 times higher than in the non-Indigenous population.63

The exact reasons for the increase in chronic kidney disease in the Indigenous population are not fully understood, but the high rates of diabetes and hypertension accelerate the development of chronic kidney disease. Coupling this with an increased level of risk factors goes some way to explaining the increased rates compared to other Australians.

Chronic kidney disease has a number of associated risk factors among Indigenous Australians, many of which are modifiable. These include low birthweight, recurrent skin infections, obesity, smoking, diabetes, excessive alcohol intake and hypertension. Other risk factors including family history and >50 years of age are non-modifiable risk factors. However, the social aspects of many Indigenous peoples will also greatly impact on risk factor contribution, and may include socioeconomic disadvantage, living in remote and disadvantaged communities (with limited access to healthcare), unemployment, low income and overcrowded living conditions.64 Note that living in urban areas does not mean evading poor kidney health; Indigenous people living in urban areas experience an incidence of chronic kidney disease that is double that of their non-Indigenous counterparts.65

Medication management has shown a significant decrease in mortality resulting from chronic kidney failure; however, modification of diet and lifestyle must also be adhered to in order to produce improvement.

The current National Chronic Kidney Disease strategy aims to achieve:

Asthma

While the prevalence of asthma in Australia is high, with approximately 1 in 9 adults diagnosed with the condition, the rates within the Indigenous population are higher (see Figure 39-12). It has been reported that Indigenous people are 1.6 times more likely to have asthma compared to non-Indigenous people of all ages.18,67 The prevalence of asthma in rural children has been suggested to be as high as 39%.68 The difference in the prevalence of asthma between Indigenous and non-Indigenous is pronounced above 45 years of age, with Indigenous rates double that of the non-Indigenous population. Furthermore, as with the trend in the Australian population, asthma prevalence rates are higher in urban than in remote areas. The exact cause of the increased prevalence of asthma in the Indigenous population is not known; however, the impact of environmental and social factors is likely to be a key determinant.

FIGURE 39-12 Prevalence of asthma in Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The rates are higher in all Indigenous age groups but pronounced in those 45 years and over.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey Australia 2004–05. ABS Catalogue no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS; 2006.

Mental illness

Mental illnesses are a major problem in the Australian Indigenous population. The Indigenous population has higher overall levels of psychological distress and this is accompanied by a significant specific stressor.18

Unfortunately, this is associated with greater rates of hospitalisation and elevated mortality rates due to mental illness.2

The Indigenous perspective of health encompasses physical health but also the emotional, cultural and social wellbeing of the entire community. Accordingly, consistently across many surveys, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander emotional, social and mental health has been reported to be affected. Over 25% of the total Indigenous population have reported high or very high levels of psychological stress.69

In the 2004–2005 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, data regarding personal stressors, social and emotional wellbeing was collected.18 Results show significant reports of stress associated with the death of a family member or close friend (up to 51%); alcohol and drug problems appear as the second most reported stressor (37%); family member incarceration and trouble with the police are stressors reported by almost 25% of all the respondents.

Dementia

Dementia refers to the progressive failure of many cerebral functions due to a number of causes (Chapter 8). It is anticipated that the incidence of dementia, especially related to Alzheimer’s disease, will dramatically increase in the older Australian population, and possibly reach 500,000 by 2050.70 Until recently, the rate of dementia in Indigenous populations was not known. However, it has been estimated that the prevalence of dementia in Indigenous peoples is 4.5 times greater than the overall Australian prevalence.71 The types of dementia are related to Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia or are alcohol induced. The risk of developing dementia in the Indigenous population is strongly related to age, male gender, no formal education, smoking, history of stroke or epilepsy and head injury. Therefore, there is an alarmingly increased risk of dementia in the Indigenous population, and the risk factors suggest that multiple health problems may lead to the development of dementia and the onset of the disorder occurs at an earlier age in Indigenous Australians.71–74 72 73 74

Infection

Infectious and parasitic diseases are more common in Indigenous peoples compared to non-Indigenous populations. This is especially the case in young children, where the rate of hospitalisation due to infection is double (see Figure 39-13).14 In fact, infection is the leading cause of infant mortality in developing countries and the Australian Indigenous paediatric population has similar health characteristics.75

FIGURE 39-13 Rates of hospitalisation for infectious and parasitic diseases in Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. ABS Catalogue no. 4704.0 and AIHW Catalogue no. IHW 21. Canberra, ABS/AIHW.

In terms of specific infections, Group A streptococcus (see ‘Rheumatic heart disease’ above), tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases such as Chlamydia and gonorrhoea are prevalent in Indigenous adults, while upper respiratory tract, skin and middle ear infections are most prevalent in Indigenous children.

Tuberculosis was most likely introduced by the first Europeans.76 In the first 150 years of European settlement, the incidence rate of tuberculosis increased in the Australian community, but with a national tuberculosis program the rate of infection declined in the non-Indigenous population from the mid-20th century. This was not the case with the Indigenous population, who currently experience rates of tuberculosis infection that are higher than that of the non-Indigenous population.77 The rates of tuberculosis (see Chapter 25) are 14 times higher in the Indigenous compared to the Australian-born non-Indigenous population — which importantly excludes migrants, as some migrant groups have high rates of tuberculosis.77 The clear distinction between these populations can be attributable primarily to the levels of poverty, poor living conditions such as overcrowding, malnutrition and excessive consumption of alcohol.15,76,77

Chlamydia and gonorrhoea are two sexually transmitted infections with a high prevalence in the Indigenous population. Chlamydia is caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis which can cause infections on the genitals and the eye. In males, a white discharge from the penis is evident, yet many females are asymptomatic. Gonorrhoea is caused by the bacterium Neisseria gonorrhoea and causes a yellowish-coloured discharge from the penis and painful urination in males. Females often have painful urination and a vaginal discharge (see Chapter 32 for more details). The Chlamydia and gonorrhoea bacteria can be transmitted through vaginal, oral and anal contact. Both sexually transmitted infections can be successfully treated with antibiotics.

Immunisation

The impact of diphtheria, measles, poliomyelitis, smallpox and tetanus which historically had greatly affected the Indigenous population now has very little impact on Indigenous health. This is also true of the non-Indigenous population. However, many diseases which can be controlled with vaccines are still disproportionately representative in the Indigenous population, especially in children.

For instance, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) is a gram-negative bacterium that can cause meningitis in children under the age of 18 months. It can also manifest as pneumonia, pericarditis and cellulitis. The majority of children with reported Hib infections were Indigenous and overall, compared to non-Indigenous children, the rate of Hib infection is high. Despite vaccination programs to target Hib, the proportion of Hib cases has increased. The infection has been associated with poor living conditions.

The rates of hepatitis A, which can in some cases lead to liver failure, is almost 5 to 1 for Indigenous to non-Indigenous notifications, and this is predominantly in children. Specific childhood vaccination programs were begun in 2005 and while there has been a reduction in the reported cases of hepatitis A, it remains too early to determine the overall impact of these programs.

Pneumonia and influenza are respiratory diseases that remain at higher rates in Indigenous populations, especially in the elderly and the young. They cause more hospitalisations and premature mortality in all Indigenous age groups and vaccination rates are lower.

Overall, while immunisation rates are increasing in the Australian population, the rate of full immunisation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children up to 24 months is about 17% less than in the corresponding non-Indigenous group.

Source: Hull B, McIntyre P, Couzos S. Evaluation of immunisation coverage for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children using the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2004; 28:47–52; National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance of Vaccine Preventable Diseases. Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination coverage in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, Australia, 2003 to 2006. Communicable Diseases Intelligence 2008; 32 Suppl:S1–S67.

Sexually transmitted diseases are a major problem in Aboriginal communities with Chlamydia and gonorrhoea rates almost 40 times higher than in non-Indigenous people.78 The rate of Chlamydia in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is more than 1100 per 100,000 of the total Indigenous population. This is in stark contrast to the non-Indigenous rate of 271 per 100,000.78

The reasons for the increased prevalence are complex, but it is generally regarded that condom usage is low in Aboriginal communities and cultural and socioeconomic factors also contribute.79 Treatment and prevention will also be influenced by cultural, social and economic factors and education and access to medical and healthcare facilities.

Indigenous children have higher rates of infection than non-Indigenous children, particularly skin and middle ear infections. It has been reported that Indigenous children have a high rate of rhinoviruses and adenoviruses without symptoms of otitis media (middle ear infection) — in fact, almost 50% of Indigenous children.80 Otitis media is common with up to 80% of Aboriginal children having the infection at some time. This can lead to hearing loss and mastoiditis in severe cases. Skin infections, particularly scabies, are also endemic in some Aboriginal communities. For instance, scabies (see Chapter 19) occurs in up to 50% of Indigenous children.81 While skin infections cause irritation to the dermal structures, more serious sequelae can lead to kidney infection and rheumatic heart disease. The most common causes of skin infections are attributable to poor living conditions.

Eye problems

The National Indigenous Eye Health Survey found that eye problems are a significant problem in Indigenous communities. For instance, blindness occurs more than 6 times more often in those communities than in other Australian communities.82 The major eye disorders that affect Indigenous people consist of cataracts, trachoma, diabetic retinopathy, refractive error and blindness.

Trachoma is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis infecting the conjunctiva leading to scarring, corneal opacification and blindness. Following the initial infection that causes purulent conjunctiva, individuals who are re-infected have an increased rate of scarring of the cornea.83 Eventually over time, the tear film becomes dry and the orbital defence mechanism is impaired, leading to secondary bacterial or fungal infections. The bacterium is transmitted via direct contact, coughing or sneezing or flies that are a carrier of the bacterium. It is a disease associated with poverty and poor hygiene, but can be successfully treated with antibiotics.

The incidence of trachoma in Aboriginal children is high, with almost no cases reported in non-Indigenous people. Outbreaks of the disease have been found in central Australia and it has been reported that many adults have trachoma scarring.84 A health strategy termed SAFE (Surgery, Antibiotics, Facial cleanliness and Environment) has greatly reduced the incidence of the disease.85 This is an important strategy to focus on the health of Aboriginal people.

FACTORS CONTRIBUTING TO HEALTH PROBLEMS

There are many factors that contribute to morbidity and mortality in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Many of the risk factors associated with an increased incidence and prevalence of diseases have been detailed above, including lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity) while others are of a social origin (housing, employment and education). It is difficult to pinpoint which factors contribute most; however, in the following sections we will examine some of the main factors.

Injuries

Injuries, including both intentional and unintentional, are prevalent for Indigenous Australians. Suicide, road traffic accidents, homicide and violence and falls were the four leading causes of injuries in Indigenous Australians.15,18,86 Moreover, Indigenous Australians are twice as likely to be hospitalised due to injury, and three times as likely to experience an injury-related death compared to non-Indigenous Australians.87

Injury causing death among Indigenous people amounts to almost 16% of all Indigenous deaths. The leading cause of injury causing death in Indigenous males, especially in the Northern Territory, is from intentional self-harm. Approximately 85% of all Indigenous suicides are in males. In addition, the suicide rate of Indigenous people is almost twice that of the non-Indigenous population, a finding similar to that in other Indigenous populations.16,88 There are a number of documented associated risk factors that contribute to injury and death arising from injury. These include: males are more susceptible to injury; remoteness is associated with an increase in injury; low socioeconomic status; history of mental health problems; alcohol and other drug use.87

The rates of interpersonal violence are higher in the Indigenous community compared to other Australians. When hospitalisation rates are examined, females are hospitalised more frequently than any other sub-group for maltreatment and rape.89 Indigenous women are 35 times more likely to be hospitalised for serious injury from a spouse or partner.90 It has also been reported that up to one in four Indigenous women with children younger than 15 years has been exposed to interpersonal violence.91 This occurrence is more common in urban areas than in remote regions; however, mothers removed from their families during childhood were almost three times at more risk of violence.91

Road traffic accident deaths occur almost three times more often among Indigenous people than among non-Indigenous people. This is related to the number of motor vehicle accidents: data from Queensland demonstrate that Indigenous people are about six times more likely to be involved in motor vehicle accidents than non-Indigenous people.92 This translates into more injury and hospitalisations.93 There are many factors that are responsible for the increased number of accidents and resultant trauma. The primary reason involves geographical location of the accidents, with rural and remote areas having a statistically higher percentage of fatal road crashes. There are large numbers of Indigenous people living in rural and remote areas of Australia (see ‘The Indigenous Australian population’ above) and, therefore, the representation of Indigenous people in motor accidents is higher. Apart from geographical considerations, factors such as alcohol use, inadequate seat-belt and helmet usage and inappropriate access to emergency medical services all contribute.94

Smoking

It has been firmly established that tobacco smoking is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, lung cancer and respiratory diseases, such as asthma, and infections (see Chapter 25). There are also problems with smoking during pregnancy which are related to perinatal problems, such as low birthweight and death.

There have been very effective public smoking cessation programs in Australia for decades; nonetheless, smoking rates remain high in the Indigenous population. For instance, smoking rates are twice as high in the 18-year-old Indigenous compared to the non-Indigenous population. About half of Indigenous Australians 15 years and over smoke daily, compared to 18% of non-Indigenous Australians (see Figure 39-14).86

FIGURE 39-14 Prevalence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians smoking daily.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey Australia 2004–05. ABS Catalogue no. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS; 2006.

In addition, more than half of all Indigenous mothers smoke during pregnancy, and this has been associated with an increased rate of low birthweight babies, prematurity and hospitalisations related to pregnancy.95

The rates of lung cancer are higher in Indigenous males and females than in their non-Indigenous counterparts. Moreover, the lung cancer mortality rate is also higher.

Alcohol misuse

Excessive alcohol consumption is a major health problem in many Indigenous communities throughout Australia. Indigenous Australians are 4.5 times more likely to have alcohol dependence and engage in consumption of alcohol that is at harmful levels (see Figure 39-15).15,18,86 While there is some evidence that alcohol use among Aboriginal people may have occurred prior to colonisation,96 in contemporary Australia it is now a major risk factor for many diseases. Surveys have found that half the Indigenous population self-reported consuming alcohol in the last week prior to the interview. In addition, 16% reported alcohol consumption at risky or high risk levels, and this is higher than in the non-Indigenous population.86,97

FIGURE 39-15 Rates of risky or high risk alcohol consumption in Indigenous and non-Indigenous males and females.

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. ABS Catalogue no. 4704.0 and AIHW Catalogue no. IHW 21. Canberra, ABS/AIHW; 2008.

Alcohol misuse can lead to serious health complications. Chronic diseases such as liver cirrhosis, diabetes and cardiovascular conditions are linked to excessive alcohol intake. In Indigenous communities, high alcohol consumption is likely to contribute significantly to domestic violence and injury arising from assaults and motor vehicle accidents.

SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF INDIGENOUS HEALTH

The Indigenous definition of health as outlined within the National Aboriginal Health Strategy clearly demonstrates that physical wellbeing does not stand alone in determining the health of an individual but that social, emotional, spiritual and cultural elements are included when determining good health. Outside an Indigenous framework these elements are often called the social determinants of health and they are the factors that influence the ability of individuals, families and communities to be able to attain good health. These social determinants can be many and varied and may include things such as gender, sexuality, stress, poverty, employment, addiction, family support and structure, and transport.

From an Indigenous perspective, cultural and spiritual factors need to be considered as do many other determinants such as loss of land, languages, stolen generations, policies of assimilation and protectionism.

Northern Territory Intervention

The Northern Territory Intervention was introduced by the Federal government in 2007 as the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) in response to the Northern Territory (NT) board of inquiry report into how government might address Indigenous child sexual abuse. The report Ampe Akeleyernemane Meke Mekarle (Little Children are Sacred) argued that the Territory government should urgently address the issue and work in collaboration with Aboriginal communities. The Federal government unilaterally intervened and introduced mandatory child health checks and major welfare reform. This included alcohol restriction, compulsory income management, external governance and changes to housing and education. This was a controversial step and many in the Indigenous community felt that there was no consultation, that the intervention would impact negatively on Aboriginal health and that the NTER were a collective imposition based on race.

The Australian government conducted an independent review in 2008 and in general the findings were that there was injustice in the implementation and development of the response and that previous governments had failed to provide basic levels of housing, education and health. The increase in policing was generally welcomed and measures to reduce alcohol-related violence were universally supported. The income management is to stay; however, it will be modified. Universal child health checks are to continue but long-term primary healthcare is required to support the checks.

It remains to be seen if the NT intervention will be sustained long term. There is scepticism from many groups that despite short-term gains in terms of disease identification and a reduction in domestic violence, the longer term may lead to reduced psychological and social health and a greater distrust between Indigenous communities and government services.

Source: Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association and Centre for Health Equity Training, Research and Evaluation, UNSW. Health impact assessment of the Northern Territory Emergency Response. Canberra: Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association, 2010; O’Mara, P. Health impacts of the Northern Territory intervention. Medical Journal of Australia 2010; 192:546–548; NTER Review Board. Northern Territory emergency response report of the NTER Review Board, Canberra; NTER Review Board; 2008; Wild R, Anderson P. Ampe Akelyernemane Meke Mekarle ‘Little children are sacred’: Report of the Northern Territory Board of Inquiry into the protection of Aboriginal children from sexual abuse. Darwin: Northern Territory Government; 2007.

There are three main social determinants of health that are relevant to contemporary Indigenous people. They are education, employment and housing.

BOX 39-4 INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE: WOMEN’S AND MEN’S BUSINESS

In many Indigenous communities in which knowledge is held about issues that impact on men and women, men’s issues are dealt with by men and women’s issues are dealt with by women. For instance, within traditional Aboriginal societies the birthing of children was strictly seen as women’s business. Birthing was attended only by women and there was much ceremony and practice around this.

Education

Education is a crucial aspect of health determination, with a strong correlation between lower levels of education and poor health. Therefore, education is an important aspect of Indigenous health.

Historically, from approximately 1850 to 1950, the first official, legally sanctioned policy was the protection policy. Under the policy of protection reserves and missions were established in most states. These established reserves and missions offered very little suitable or sustainable living for the many Aboriginal people who were forced to live within their confines. The education that was offered was minimal and basic. It was thought that Aboriginal people needed little if any education because they were not expected to engage in ‘meaningful work’ but were only suited to work as domestic servants and cattlemen. Also under this policy Aboriginal children were excluded from state schools. This historical exclusion of Indigenous people makes it difficult to turn around the decades of neglect of Indigenous people accessing education.

Nationally, there has been an increase in the number of Indigenous full-time school students since 1999. However, rates of attainment of year 12 (completion of secondary school) are substantially lower for Indigenous students when compared to non-Indigenous students.98 In 2006 only 19% of Indigenous students completed year 12 compared to 45% of non-Indigenous students. Year 10 completion was the most common level of school completion among Indigenous students.99

BOX 39-5 INDIGENOUS PERSPECTIVE: INDIGENOUS ELDERS

Within Indigenous culture elders are given unquestioning respect; this was the custom long before colonisation. Elders are the knowledge holders; history and culture is passed on through generations, usually orally from the elders. The elders teach customs, lore, healing practices, languages and the creation stories of their country to their people. Often Indigenous Australians will refer to older Indigenous people as Aunty or Uncle; this is a symbol of respect. While these people may not be blood relatives, the use of these English titles demonstrates recognition of the elders’ knowledge and the legacy they provide.

However, the role of the elders has been modified by the numerous impacts of colonisation. The knowledge held by elders, once most highly valued, has been shrouded by the impact of colonisation. Elders can now find it difficult to share their knowledge about the intimate relationship Indigenous people once shared with their environment.

Literacy is very important as it enables people to participate in the community, in employment and to understand what constitutes good health. Unfortunately, despite an increase in participation and education attainment, literacy rates in the Indigenous population are lower than for other Australians. This is especially pronounced in remote regions of Australia, where access to educational facilities is limited compared to urban settings. It has been reported that fewer than 30% of Indigenous children in remote regions achieved national reading levels at year 3.15 Therefore, overall, education levels for Indigenous Australians are poorer than for non-Indigenous Australians. This represents an opportunity for improvement, which may in turn lead to improved empowerment and understanding of health issues among Indigenous Australians.

Employment

In Australia the inequity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples and employment is stark. The national unemployment rate for Indigenous people is three times the rate for non-Indigenous people.

Again it is important to know the historical context to understand the legacy of the low employment rates of Indigenous peoples. Australia has a complex and very confronting history of Indigenous rights abuses that have impacted on employment for many Indigenous people. Until the 1960s and 1970s many reserves and missions on which Indigenous people were forced to live were still operational. The people were administered under the protection policy. They were forced to work and paid wages well below those of non-Indigenous people, wages which were often supplemented by rations. They were used as a source of cheap labour and their wages were managed by a trust fund over which a bureaucrat such as the Director of Aboriginal and Island Affairs had complete control. This practice was still in place as late as 1973 and had a long-lasting impact on Indigenous employment.

In contemporary Australia, Indigenous people generally work in lower skilled jobs, have high rates of unemployment in urban and rural regions, and are employed in jobs that generate less income than do those of their non-Indigenous peers. Improved employment conditions in the future may impact on their ability to afford better healthcare and healthier lifestyle options.

Housing

In 2006 one in every two Indigenous households was receiving some form of government housing assistance, such as living in public or community housing, or receiving rent assistance. In 2006, one in seven Indigenous households was overcrowded (see Figure 39-16). Indigenous peoples were over-represented in the national Supported Accommodation Assistance Program for the homeless and those at risk of homelessness, comprising 17% of the total assistance program clients.

FIGURE 39-16 Overcrowding in inadequate housing.

The problem of overcrowding, especially in rural and remote areas, leads to increases in interpersonal violence, infection and social problems.

Source: Grace M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet 2009; 374:65–75.

The proportion of Indigenous households who owned or were purchasing their homes in 2006 was half the rate of other Australians households (34% compared with 69%).86 The issue facing many communities (ex missions/reserves) across Queensland, for example, is the lack of available housing. Therefore, overcrowding is a relevant issue for many of these communities and can contribute to poorer health.

Indigenous health

Indigenous Australians define health as the physical, social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community, not just the individual.

Indigenous Australians define health as the physical, social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community, not just the individual. Life expectancy for Indigenous Australians is approximately 17 years lower than for the whole population.

Life expectancy for Indigenous Australians is approximately 17 years lower than for the whole population.Diseases and disorders

Indigenous Australians suffer a higher rate of disease and disorders compared to non-Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians suffer a higher rate of disease and disorders compared to non-Indigenous Australians. Rheumatic heart disease occurs in Australian Indigenous children at rates that are similar to those in developing countries. It is a treatable disease that is mostly eradicated from other sections of the Australian population.

Rheumatic heart disease occurs in Australian Indigenous children at rates that are similar to those in developing countries. It is a treatable disease that is mostly eradicated from other sections of the Australian population. Type 2 diabetes mellitus occurs in almost endemic proportions in Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders. There are many risk factors but obesity is likely to be the main determinant of diabetes in Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus occurs in almost endemic proportions in Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders. There are many risk factors but obesity is likely to be the main determinant of diabetes in Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. Genetic influences have been proposed that may contribute to the development of diabetes in Indigenous people.

Genetic influences have been proposed that may contribute to the development of diabetes in Indigenous people.Factors contributing to health problems

Injury, arising from assaults, domestic violence and motor vehicle accidents, impacts on mortality rates disproportionately in Indigenous people.

Injury, arising from assaults, domestic violence and motor vehicle accidents, impacts on mortality rates disproportionately in Indigenous people. Indigenous Australians are twice as likely to be hospitalised due to injury, and three times as likely to experience an injury-related death compared to non-Indigenous Australians.