CHAPTER 2 Management of Endodontic Emergencies

Emergency Classifications

The proper diagnosis and effective management of acute dental pain is possibly one of the most rewarding and satisfying aspects of providing dental care. An endodontic emergency is defined as pain and/or swelling, caused by various stages of inflammation or infection of the pulpal and/or periapical tissues. The cause of dental pain is generally from caries, deep or defective restorations, or trauma. Bender9 stated that patients who manifest severe or referred pain almost always had a previous history of pain with the offending tooth. Approximately 85% of all dental emergencies arise as a result of pulpal or periapical disease, which would necessitate either extraction or endodontic treatment to relieve the symptoms.32,47 It has also been estimated that about 12% of the U.S. population experienced a toothache in the preceding 6 months.44

Determining a definitive diagnosis can sometimes be challenging and even frustrating for the clinician; but a methodical, objective, and subjective evaluation, as described in Chapter 1, is imperative before developing a proper treatment plan. Unfortunately, on the basis of the diagnosis, there are conflicting opinions on how to best clinically manage various endodontic emergencies. According to surveys taken among endodontists in 1977,18,19 1990,25 and 200943 there are seven clinical presentations that are considered endodontic emergencies:

There are other endodontic emergencies that were not discussed in these surveys. These emergencies pertain to traumatic dental injuries, as discussed in Chapter 17, to teeth that have had previous endodontic treatment, as discussed in Chapters 16 and 25, and endodontic flare-ups that may occur between treatment sessions. Of course, there are also many types of facial pain that have a nonodontogenic origin; these are described in detail in Chapter 3.

In the decades between the previously cited surveys, there have been several changes as to the preferred clinical management of endodontic emergencies. Many of these treatment modifications have occurred because of the more contemporary armamentarium and materials as well as new evidence-based research and the presumption of empirical clinical success.

Emergency Endodontic Management

Because pain is both a psychologic and biologic entity, as discussed in Chapters 19 and online Chapter 26, the management of acute dental pain must take into consideration both the physical symptoms as well as the emotional state of the patient. The patient’s needs, fears, and coping mechanisms must be compassionately understood. This assessment and the clinician’s ability to build rapport with the patient are key factors in the comprehensive success of the patient’s management.9,24,35,64

The methodical steps for determining an accurate diagnosis, based on evaluation of the patient’s chief complaint, review of the medical history, and the protocols used for an objective and subjective diagnosis, are described in detail in Chapter 1. Once it has been determined that endodontic treatment is necessary, it is incumbent on the clinician to take the proper steps necessary to manage the acute dental emergency.

As described in Chapters 11 and 27, the clinician has a responsibility to inform the patient of the recommended treatment plan, and to advise the patient of the treatment alternatives, the risks and benefits that pertain, and the expected prognosis under the present circumstances. Given this information, the patient may elect extraction over endodontics, or possibly request a second opinion. The treatment plan should never be forced on a patient. The informed course of treatment is made jointly between the patient and the clinician.

In the event of an endodontic emergency, the clinician must determine the optimal mode of endodontic treatment pursuant to the diagnosis. Treatment may vary depending on the pulpal or periapical status, the intensity and duration of pain, and whether there is diffuse or fluctuant swelling. Paradoxically, as discussed later, the mode of therapy that we tend to choose has been directed more from surveys of practicing endodontists rather than from controlled clinical studies or research investigations.

Vital Teeth

As described in Chapter 1, vital teeth can have one of the following presentations:

Reversible Pulpitis

Reversible pulpitis can be induced by caries, exposed dentin, recent dental treatment, and defective restorations. Conservative removal of the irritant and a proper restoration will typically resolve the symptoms. However, the symptoms from exposed dentin, specifically from gingival recession and cervically exposed roots, can often be difficult to alleviate. Topical applications of desensitizing agents and the use of certain dentifrices have been helpful in the management of dentin hypersensitivity; the etiology, physiology, and management of this are discussed in Chapter 19.

Irreversible Pulpitis

The diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis can be subcategorized as asymptomatic or symptomatic. Asymptomatic irreversible pulpitis pertains to a tooth that has no symptoms, but with deep caries or tooth structure loss that, if left untreated, will cause the tooth to become symptomatic or nonvital. On the other hand, the pain from symptomatic irreversible pulpitis is often an emergency condition that requires immediate treatment. These teeth exhibit intermittent or spontaneous pain, whereby exposure to extreme temperatures, especially cold, will elicit intense and prolonged episodes of pain, even after the source of the stimulus is removed.

In 1977,18,19 187 board-certified endodontists were surveyed to determine how they would manage various endodontic emergencies. Ten years later, 314 board-certified endodontists responded to the same questionnaire in order to determine whether there have been any procedural changes in how these emergencies are managed.25 The emergency treatment of a tooth with irreversible pulpitis with or without a normal periapex seemed to be managed fairly similarly. In the same survey conducted in 2009,43 most respondents stated that they cleaned to the level of the “apex,” as confirmed with an electronic apex locator; this suggests a change in the management of endodontic cases based on the advent of a more contemporary armamentarium. In general, the most current survey indicates that there is a trend toward more cleaning and shaping of the canal when irreversible pulpitis presents with a normal periapex, compared with performing just pulpectomies as described in the 1977 survey. None of the individuals surveyed in the 1990 or 2009 poll stated that they would manage these emergencies by establishing any type of drainage by trephinating the apex, making an incision, or leaving the tooth open for an extended period of time. In addition, for vital teeth, the 1977 survey did not even broach the concept of completing the endodontics in one visit, whereas in the 1988 study about one third of the respondents indicated that they would complete these vital cases in a single visit. Since the early 1980s, there seems to have been an increase in the acceptability of providing endodontic therapy in one visit, especially in cases of vital pulps, with most studies revealing an equal number, or fewer, flare-ups after single-visit endodontic treatment.20,54,56,61,63,69 However, this has not come without controversy, with some studies showing otherwise,23,77 contending that there is more posttreatment pain after single-visit endodontics, and possibly a lower long-term success rate. Unfortunately, time constraints at the emergency visit often make the single-visit treatment option difficult.3 If root canal therapy is to be completed at a later date, medicating the canal with calcium hydroxide probably is indicated to reduce the chances of bacterial growth in the canal between appointments13; however, controlled studies have not substantiated this concept.10,13,31 One randomized clinical study showed that a dry cotton pellet was as effective in relieving pain as a pellet moistened with camphorated monochlorophenol (CMCP), metacresylacetate (Cresatin), eugenol, or saline.31 Sources of infection, such as caries and defective restorations, should be completely removed to prevent recontamination of the root canal system between appointments.31 The concept of single- versus multiple-visit endodontics is described in greater detail in Chapter 4.

For emergency endodontic treatment of vital teeth that are not initially sensitive to percussion, occlusal reduction has not been shown to be beneficial.15,25 However, the clinician should be cognizant of the possibility of occlusal interferences and prematurities that might cause tooth fracture under heavy mastication. In vital teeth in which the inflammation has extended periapically, which will present with pretreatment pain to percussion, occlusal reduction has been reported to reduce posttreatment pain.25,53,62

Antibiotics are not recommended for the emergency management of irreversible pulpitis40 (see Chapter 19). Moreover, placebo-controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that antibiotics have no effect on pain levels in patients with irreversible pulpitis.51

On the basis of several surveys of board-certified endodontists as well as other recommendations in the literature,13,25,30,43,71 the emergency management of a symptomatic irreversible pulpitis involves initiating root canal treatment, with complete pulp removal and total cleaning of the root canal system. Unfortunately, in an emergency situation, the allotted time necessary for this treatment is often an issue. Given the potential time constraints and inevitable differences in skill level between clinicians, it may not be feasible to complete the total canal cleaning at the initial emergency visit. Subsequently, especially with multirooted teeth, a pulpotomy (removal of the coronal pulp or tissue from the widest canal) has been advocated for emergency treatment of irreversible pulpitis.30,71

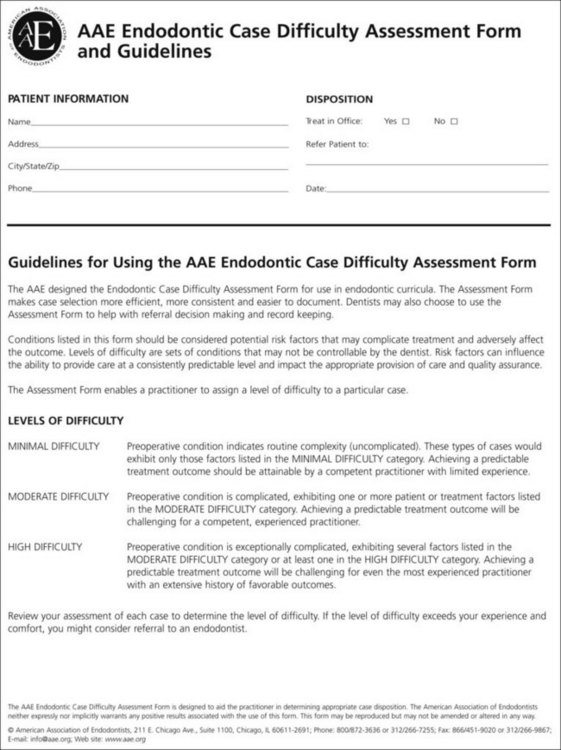

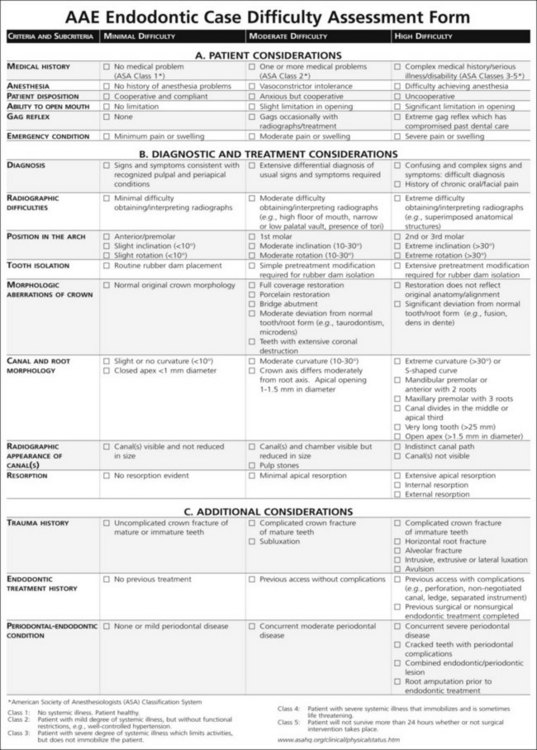

To assist the clinician in assessing the level of difficulty of a given endodontic case, the American Association of Endodontists (Chicago, IL) has developed the “AAE Endodontic Case Difficulty Assessment Form and Guidelines” (Fig. 2-1). This form is intended to make case selection more efficient, more consistent, and easier to document, as well as to provide a more objective ability to determine when it may be necessary to refer the patient to another clinician, who may be better able to manage the complexities of the case.

Pulpal Necrosis With Acute Apical Abscess

No Swelling

Over the years, the proper methodology for the emergency endodontic management of necrotic teeth has been controversial. In a 1977 survey of board-certified endodontists,18,19 it was reported that, in the absence of swelling, most respondents would completely instrument the canals, keeping the file short of the radiographic apex. However, when swelling was present, the majority of those polled in 1977 preferred to leave the tooth open, with instrumentation extending beyond the apex to help facilitate drainage through the canals. Ten years later and again validated in a 2009 study, most respondents favored complete instrumentation regardless of the presence of swelling. Also, it was the decision of 25.2% to 38.5% of the clinicians to leave these teeth open in the event of diffuse swelling; 17.5% to 31.5% left the teeth open in the presence of a fluctuant swelling. However, as discussed later, there is currently a trend toward not leaving teeth open for drainage. There is also another trend: when treatment is done in more than one visit, most endodontists will use calcium hydroxide as an intracanal medicament.43

Care should be taken not to allow necrotic debris to be pushed beyond the apex, because this has been shown to promote more posttreatment discomfort.10,25,59,67 Improvements in technology, such as electronic apex locators, have facilitated increased accuracy in determining working length measurements, which in turn may allow for a more thorough canal debridement. These devices are now used by an increased number of clinicians.17,43

Trephination

In the absence of swelling, trephination is the surgical perforation of the alveolar cortical plate to release from between the cortical plates the accumulated tissue exudate that causes pain. Its use has been historically advocated to provide pain relief in patients with severe and recalcitrant periradicular pain.18,19 The technique involves an engine-driven perforator entering through the cortical bone and into the cancellous bone, often without the need for an incision.12 This provides a pathway for drainage from the periradicular tissues. Although more recent studies have failed to show the benefit of trephination in patients with irreversible pulpitis with acute periapical periodontitis48 or symptomatic necrotic teeth with radiolucencies,53 there are still some advocates who recommend trephination for managing acute and intractable periapical pain.33 The clinician should understand that local anesthesia may be difficult.36 Also, extreme care must be taken to guard against inadvertent and possibly irreversible injury to the tooth root or surrounding structures, such as the mental foramen, intraalveolar nerve, or maxillary sinus.

Necrosis and Single-Visit Endodontics

Although single-visit endodontic treatment for teeth diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis is not contraindicated,1,56,58,63,78 performing single-visit endodontics on necrotic and previously treated teeth is not without controversy. In cases of necrotic teeth, research20 has indicated that there may be no difference in posttreatment pain if the canals are filled at the time of the emergency versus a later date. Although some more recent studies68,72 have questioned the long-term prognosis of such treatment, especially in cases of acute periodontitis, several studies,21,42 including a CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) clinical trial,57 have shown no difference in outcome between single-visit and two-visit treatments. The concept of single- versus multivisit endodontics is further discussed in Chapter 4.

Swelling

Tissue swelling may be associated with an acute periradicular abscess at the time of the initial emergency visit, or may occur as an interappointment flare-up or as a postendodontic complication. Swellings may be localized or diffuse, fluctuant or firm. Localized swellings are confined within the oral cavity whereas a diffuse swelling, or cellulitis, is more extensive, spreading through adjacent soft tissues, dissecting tissue spaces along fascial planes.37

Swelling may be controlled by establishing drainage through the root canal or by incising the fluctuant swelling. As discussed later, and in Chapter 15, antibiotics are also an integral part of the management of swelling. The principal modality for managing swelling secondary to endodontic infections is to achieve drainage and remove the source of the infection.27,37 When the swelling is localized, the preferred avenue is drainage through the root canal. Complete canal debridement and disinfection29,74 are paramount to success regardless of observable drainage, because the presence of any bacteria remaining within the root canal system will compromise the resolution of the acute infection.45 In the presence of persistent swelling, gentle finger pressure to the mucosa overlying the swelling may help facilitate drainage. Once the canals have been cleaned and allowed to dry, the access should be closed.13,25,30 In these cases, there has been a trend to use calcium hydroxide as the intracanal medicament.43

Incision for Drainage

Often it becomes necessary to establish drainage from a localized soft tissue swelling. This can be accomplished through the incision for drainage of the area.52 Incision for drainage is indicated whether the cellulitis is indurated or fluctuant.37 A pathway for drainage is needed to prevent further spread of infection. An incision for drainage allows decompression of the increased tissue pressure associated with edema and can provide significant pain relief for the patient. The incision also provides a pathway not only for bacteria and bacterial by-products but also for the inflammatory mediators that are associated with the spread of cellulitis.

The basic principles of incision for drainage are as follows:

A diffuse swelling may develop into a life-threatening medical emergency. Because the spread of infection can traverse between the fascial planes and muscle attachments, vital structures can be compromised and breathing may be impeded. It is imperative that the clinician be in constant communication with the patient to ensure that the infection does not worsen and that medical attention is provided as necessary. Antibiotics and analgesics should be prescribed, and the patient should be monitored closely for the next several days or until there is improvement. Individuals who show signs of toxicity, elevated body temperature, lethargy, central nervous system (CNS) changes, or airway compromise should be referred to an oral surgeon or medical facility for immediate care and intervention.

Symptomatic Teeth With Previous Endodontic Treatment

The emergency management of teeth with previous endodontic treatment may be technically challenging and time-consuming. This is especially true in the presence of extensive restorations, including posts and cores, crowns, and bridgework. However, the goal remains the same as for the management of necrotic teeth: Remove contaminants from the root canal system and establish patency to achieve drainage.31,58 Gaining access to the periapical tissues through the root canals may require removal of posts and obturation, as well as negotiating blocked or ledged canals. Failure to complete root canal debridement and achieve periapical drainage may result in continued painful symptoms. The ability, practicality, and feasibility to adequately re-treat the root canal system must be carefully assessed before the initiation of treatment, as conventional retreatment might not be the optimal treatment plan. This is further discussed in Chapter 254.

Leaving Teeth Open

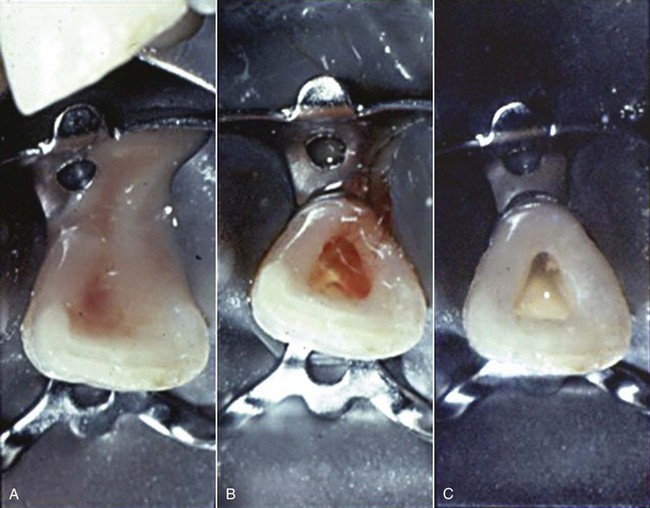

On rare occasions, canal drainage may continue from the periapical spaces (Fig. 2-2). In these cases, the clinician may opt to step away from the patient for some time to allow for the drainage to continue and hopefully resolve on the same treatment visit.71

FIG. 2-2 Nonvital infected tooth with active drainage from the periapical area through the canal. A, Access opened and draining for 1 minute. B, Drainage after 2 minutes. C, Canal space dried after 3 minutes.

Historically, in the presence of acutely painful necrotic teeth with no swelling to diffuse swelling, 19.4% to 71.2% of surveyed endodontists would leave the tooth open between visits.18,19 However, the more current literature makes it clear that this form of treatment would impair uneventful resolution and create more complicated treatment.6,8,79 For this reason, leaving teeth open between appointments is not recommended. There has even been a documented case report of a foreign object being found to enter the periapical tissues through a tooth that had been left open for drainage.66 However, leaving teeth open between visits to allow for drainage or to manage intractable pain is not without controversy. August in 19774 and again in 19825 suggested that the problem with leaving teeth open had more to do with how they are later closed. He found that total instrumentation before the closing of open teeth had a 96.7% success rate.

Antibiotics

The prescription of antibiotics should be adjunctive to appropriate clinical treatment (see Chapters 15 and 19 for details). Because of potential risk factors such as allergies, drug interactions, and systemic complications, antibiotics should be prescribed judicially. They are indicated when signs and symptoms suggest systemic involvement such as high fever, malaise, cellulitis, unexplained trismus, and persistent and progressive infections, and for patients who are immunologically compromised.7,22,28,34,74 The objective is to aid in the elimination of infection from the tissue spaces. The use of antibiotics alone, without properly addressing the source of the endodontic infection, is not appropriate treatment.27,37

Analgesics

Because a more thorough description of pain medications can be found in Chapter 19, the following information is merely a summary of pain control using analgesics. Because pulpal and periapical pain involves inflammatory processes, the first choice of analgesics is nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).43 However, no pain medication can replace the efficacy of thoroughly cleaning the root canal to rid the tooth of the source of infection.26

Aspirin has been used as an analgesic for more than 100 years. In some cases, it may be more effective than 60 mg of codeine14; its analgesic and antipyretic effects are equal to those of acetaminophen, and its antiinflammatory effect is more potent.16 However, aspirin’s side effects include epigastric distress, nausea, and gastrointestinal ulceration. In addition, its analgesic effect is inferior to that of ibuprofen, 400 mg. When NSAIDs and aspirin are contraindicated, such as in patients for whom gastrointestinal problems are a concern, acetaminophen is the preferred nonprescription analgesic. The maximal dose of 4 g in a 24-hour period should not be exceeded.

For moderate to severe pain relief, ibuprofen, an NSAID, has been found to be superior to aspirin (650 mg) and acetaminophen (600 mg) with or without codeine (60 mg). Also, ibuprofen has fewer side effects than the combinations with opioid.14,39 The maximal dose of 3.2 g in a 24-hour period should not be exceeded. Patients who take daily doses of aspirin for its cardioprotective benefit can take occasional doses of ibuprofen; however, it would be prudent to advise such patients to avoid regular doses of ibruprofen.46 These patients would gain more relief by taking a selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor, such as diclofenac or celecoxib.

Because of their antiinflammatory effect, NSAIDs can suppress swelling to a certain degree after surgical procedures. The good analgesic effect combined with the additional antiinflammatory benefit make NSAIDs, especially ibuprofen, the drug of choice for acute dental pain in the absence of any contraindication to their use. Ibuprofen has been used for more than 30 years and has been thoroughly evaluated.16 If the NSAID alone does not have a satisfactory effect in controlling pain, then the addition of an opioid may provide additional analgesia. However, in addition to other possible side effects, opioids may cause nausea, constipation, lethargy, dizziness, and disorientation.

Laboratory Diagnostic Adjuncts

Chapter 15 discusses culturing techniques and indications. Because the results of culturing for anaerobic bacteria usually require at least 1 to 2 weeks, it is not considered routine in the management of an acute endodontic emergency. Thus, in an endodontic emergency, antibiotic treatment, when indicated (see Chapter 15), should begin immediately, because oral infections can progress rapidly.

Flare-ups

An endodontic flare-up is defined as an acute exacerbation of a periradicular pathosis after the initiation or continuation of nonsurgical root canal treatment.2 The incidence may be from 2% to 20% of cases.38,49,55,76 A meta-analysis of the literature, using strict criteria, showed the flare-up frequency to be 8.4%.73 Endodontic flare-ups seem to be more prevalent among females under the age of 20 years, and may occur more in maxillary lateral incisors; mandibular first molars, when there are large periapical lesions; and in the re-treatment of previous root canals.70 The presence of pretreatment pain may also be a predictor of potential posttreatment flare-ups.38,70,76 Fortunately, there does not seem to be a decrease in the successful conclusion of cases that had a treatment flare-up.41

Endodontic flare-ups may occur because of a variety of reasons, including preparation beyond the apical terminus, overinstrumentation, pushing dentinal and pulpal debris into the periapical area,27 incomplete removal of pulp tissue, overextension of root canal filling material, chemical irritants (such as irrigants, intracanal medicaments, and sealers), hyperocclusion, root fractures, and microbiologic factors.65 Although many of these cases can be pharmacologically managed (see Chapter 19), recalcitrant cases may require reentry into the tooth, the establishment of drainage either through the tooth or via trephination, or, at a minimum, adjustment of the occlusion.15,62,65 The prophylactic use of antibiotics to decrease the incidence of flare-ups has been met with some controversy. Whereas earlier investigators50 found that antibiotic administration before treatment of necrotic teeth decreased the incidence of flare-ups, a more recent study70 found antibiotic use less effective than analgesics in reducing interappointment emergencies, and other, more current studies60,75 concluded that the prophylactic use of antibiotics had no effect on posttreatment symptoms.

Cracked and Fractured Teeth

Described in detail in Chapter 1, cracks and fractures can be difficult to locate and diagnose, but their detection can be an important component in the management of an acute dental emergency. In the early stages, cracks are small and difficult to discern. Removal of filling materials, applications of dye solutions, selective loading of cusps, transillumination, and magnification are helpful in their detection. As the crack or fracture becomes more extensive, it can become easier to visualize. Because cracks are difficult to find and their symptoms can be so variable, the name cracked tooth syndrome has been suggested11 even though it is not truly a syndrome. Cracks in vital teeth often exhibit a sudden and sharp pain, especially during mastication. Cracks in nonvital or obturated teeth tend to have more of a “dull ache,” but can still be sensitive to mastication.

The determination of the presence of a crack or fracture is paramount because the prognosis for the tooth may be directly dependent on the extent of the crack or fracture. Management of cracks in vital teeth may be as simple as a bonded restoration or a full coverage crown. However, even the best efforts to manage a crack may be unsuccessful, often requiring endodontic treatment or extraction. Fractures in nonvital or obturated teeth may be more challenging. In addition, it must be determined whether the crack or fracture was the cause of the necrosis. If so, the prognosis for the tooth is generally poor; thus extraction is recommended.

Summary

The management of endodontic emergencies is an important part of a dental practice. It can often be a disruptive part of the day for the clinician and staff, but it is an invaluable solution for the distressed patient. Methodical diagnosis and prognostic assessment are imperative, with the patient being informed of the various treatment alternatives.

Acknowledgment

The editors acknowledge Dr. Louis Berman for his extraordinary contribution to preparing this chapter for publication.

1. Albahaireh ZS, Alnegrish AS. Postobturation pain after single and multiple-visit endodontic therapy: a prospective study. J Dent. 1998;26:227.

2. American Association of Endodontics. Glossary of endodontic terms, ed 7. Chicago: American Association of Endodontists; 2003.

3. Ashkenaz PJ. One-visit endodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 1984;28:853.

4. August DS. Managing the abscessed tooth: instrument and close? J Endod. 1977;3:316.

5. August DS. Managing the abscessed open tooth: instrument and close—part 2. J Endod. 1982;8(8):364-366.

6. Auslander WP. The acute apical abscess. N Y State Dent J. 1970;36:623-627.

7. Baumgartner JC, Xia T. Antibiotic susceptibility of bacteria associated with endodontic abscesses. J Endod. 2003;29:44.

8. Bence R, Meyers RD, Knoff RV. Evaluation of 5,000 endodontic treatment incidents of the open tooth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49:82-84.

9. Bender IB. Pulpal pain diagnosis—a review. J Endod. 2000;26:175.

10. Bystrom A, Claesson R, Sundqvist G. The antibacterial effect of camphorated paramonochlorophenol, camphorated phenol and calcium hydroxide in the treatment of infected root canals. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1985;1:170.

11. Cameron CE. The cracked tooth syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc. 1976;93:971.

12. Chestner SB, Selman AJ, Friedman J, Heyman RA. Apical fenestration: solution to recalcitrant pain in root canal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1986;77:846.

13. Chong BS, Pitt Ford TR. The role of intracanal medication in root canal treatment. Int Endod J. 1992;25:97.

14. Cooper SA, Beaver WT. A model to evaluate mild analgesics in oral surgery outpatients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976;20:241.

15. Creech JH, Walton RE, Kaltenbach R. Effect of occlusal relief on endodontic pain. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:64.

16. Dionne RA, Phero JC, Becker DE. Management of pain and anxiety in the dental office. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002.

17. Kim E, Lee SJ Electronic apex locator [Review] [59 refs] Dent Clin North Am 48 1 2004 35-54

18. Dorn SO, Moodnik RM, Feldman MJ, Borden BG. Treatment of the endodontic emergency: a report based on a questionnaire—part I. J Endod. 1977;3(3):94-100.

19. Dorn SO, Moodnik RM, Feldman MJ, Borden BG. Treatment of the endodontic emergency: a report based on a questionnaire—part II. J Endod. 1977;3(4):153-156.

20. Eleazer PD, Eleazer KR. Flare-up rate in pulpally necrotic molars in one-visit versus two-visit endodontic treatment. J Endod. 1998;24:614.

21. Field JW, Gutmann JL, Solomon ES, Rakuskin H. A clinical radiographic retrospective assessment of the success rate of single-visit root canal treatment. Int Endod J. 2004;37:70.

22. Fouad A, Rivera E, Walton R. Penicillin as a supplement in resolving the localized acute apical abscess. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1996;81:590.

23. Friedman S, Löst C, Zarrabian M, Trope M. Evaluation of success and failure after endodontic therapy using a glass ionomer cement sealer. J Endod. 1995;21(7):384-390. Jul

24. Gatchel RJ. Managing anxiety and pain during dental treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:37.

25. Gatewood RS, Himel VT, Dorn S. Treatment of the endodontic emergency: a decade later. J Endod. 1990;16:284.

26. Hargreaves KM, Keiser K. New advances in the management of endodontic pain emergencies. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2004;32:469-473.

27. Harrington GW, Natkin E. Midtreatment flare-ups. Dent Clin North Am. 1992;36:409.

28. Harrison JW. The appropriate use of antibiotics in dentistry: endodontic indications. Quintessence Int. 1997;28:827.

29. Harrison JW. Irrigation of the root canal system. Dent Clin North Am. 1984;28:797.

30. Hasselgren G. Pains of dental origin. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;12:263.

31. Hasselgren G, Reit C. Emergency pulpotomy: pain relieving effect with and without the use of sedative dressings. J Endod. 1989;15:254.

32. Hasler JF, Mitchel DF. Analysis of 1628 cases of odontalgia: a corroborative study. J Indianap Dist Dent Soc. 17, 23 Jan 1963.

33. Henry BM, Fraser JG. Trephination for acute pain management. J Endod. 2003;29(2):144-146.

34. Henry M, Reader A, Beck M. Effect of penicillin on postoperative endodontic pain and swelling in symptomatic necrotic teeth. J Endod. 2001;27:117.

35. Holmes-Johnson E, Geboy M, Getka EJ. Behavior considerations. Dent Clin North Am. 1986;30:391.

36. Horrobin DF, Durnad LG, Manku MS. Prostaglandin E1 modifies nerve conduction and interferes with local anesthetic action. Prostaglandins. 1997;14:103.

37. Sandor GK, Low DE, Judd PL, Davidson RJ. Antimicrobial treatment options in the management of odontogenic infections. J Can Dent Assoc. 1998 Jul-Aug;64(7):508-514. Comment in J Can Dent Assoc. 65(11):602, 1999 Dec.

38. Imura N, Zuolo ML. Factors associated with endodontic flare-ups: a prospective study. Int Endod J. 1995;28:261-265.

39. Jain AK, Ryan JR, McMahon G. Analgesic efficacy of low-dose ibuprofen in dental extraction. Pharmacotherapy. 1986;6:318.

40. Keenan JV, Farman AG, Fedorowica Z, Newton JT. A Cochrane Systematic Review finds no evidence to support the use of antibiotics for pain relief in irreversible pulpitis. J Endod. 2006;32(2):87-92.

41. Kerekes K, Tronstad L. Long-term results of endodontic treatment performed with a standardized technique. J Endod. 1979;5(3):83-90.

42. Kvist T, Molander A, Dahlen G, Reit C. Microbiological evaluation of one- and two-visit endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis: a randomized, clinical trial. J Endod. 2004;30:572.

43. Lee M, Winkler J, Hartwell G, et al. Current trends in endodontic practice: emergency treatments and technological armamentarium. J Endod. 2009;35(1):35-39.

44. Lipton JA, Ship JA, Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;124:115-121.

45. Matusow RJ, Goodall LB. Anaerobic isolates in primary pulpal–alveolar cellulitis cases: endodontic resolutions and drug therapy considerations. J Endod. 1983;9:535.

46. Abramowicz M Do NSAIDs interfere with the cardioprotective effects of aspirin? editor Med Lett Drugs Ther 46 2004 61-62

47. Mitchell DF, Tarplee RE. Painful pulpitis: a clinical and microscopic study. Oral Surg. Nov 1960;13:1360.

48. Moos HL, Bramwell JD, Roahen JO. A comparison of pulpectomy alone versus pulpectomy with trephination for the relief of pain. J Endod. 1996;22:422.

49. Morse DR, Koren LZ, Esposito JV, et al. Asymptomatic teeth with necrotic pulps and associated periapical radiolucencies: relationship of flare-ups to endodontic instrumentation, antibiotic usage and stress in three separate practices at three different time periods. Int J Psychosom. 1986;33(1):5-87.

50. Morse DR, Furst ML, Belott RM, et al. Infectious flare-ups and serious sequelae following endodontic treatment: a prospective randomized trial on efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in cases of asymptomatic pulpal–perapical lesion. Oral Surg. 1987;64:96-109.

51. Nagle D, Reader A, Beck M, Weaver J. Effect of systemic penicillin on pain in untreated irreversible pulpitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2000;90:636.

52. Natkin E. Treatment of endodontic emergencies. Dent Clin North Am. 1974;18:243.

53. Nusstein J, Reader A, Nist R, Beck M, Meyers NJ. Anesthetic efficacy of the supplemental intraosseous injection. J Endod. 1998;24:487.

54. Oliet S. Single-visit endodontics: a clinical study. J Endod. 1998;24:614.

55. Oginni AO, Udoye CI. Endodontic flare-ups: comparison of incidence between single and multiple visit procedures in patients attending a Nigerian teaching hospital. BMC Oral Health. 2004;4:4.

56. Pekruhn RB. The incidence of failure following single-visit endodontic therapy. J Endod. 1996;12:68.

57. Penesis VA, Fitzgerald PI, Fayad MI, Wenckus CS, BeGole EA, Johnson BR. Outcome of one-visit and two-visit endodontic treatment of necrotic teeth with apical periodontitis: a randomized controlled trial with one-year evaluation. J Endod. 2008;34:251-257.

58. Peters LB, Wesselink PR. Periapical healing of endodontically treated teeth in one and two visits obturated in the presence or absence of detectable microorganisms. Int Endod J. 2002;35:660.

59. Reddy SA, Hicks ML. Apical extrusion of debris using two hand and two rotary instrumentation techniques. J Endod. 1998;24:180.

60. Pickenpaugh L, Reader A, Beck M, et al. Effect of prophylactic amoxicillin on endodontic flare-up in asymptomatic, necrotic teeth. J Endod. 2001;27:53-56.

61. Roane JB, Dryden JA, Grimes EW. Incidence of postoperative pain after single- and multiple-visit endodontic procedures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55(1):68-72.

62. Rosenberg PA, Babick PJ, Schertzer L, Leung A. The effect of occlusal reduction on pain after endodontic instrumentation. J Endod. 1998;24:492.

63. Rudner WL, Oliet S. Single-visit endodontics: a concept and a clinical study. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1981;2:63.

64. Rugh JD. Psychological components of pain. Dent Clin North Am. 1987;31:579.

65. Seltzer S, Naidorf IJ. Flare-ups in endodontics. 1. Etiological factors. J Endod. 1985;11:472-478.

66. Simon JH, Chimenti RA, Mintz GA. Clinical significance of the pulse granuloma. J Endod. 1982;8:116-119.

67. Siqueira JF, Rocas IN. Microbial causes of endodontic flare-ups. Int Endod J. 2003;36:433.

68. Sjogren U, Figdor D, Persson S, Sundqvist G. Influence of infection at the time of root filling on the outcome of endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis. Int Endod J. 1997;30:297.

69. Southard DW, Rooney TP. Effective one-visit therapy for the acute periapical abscess. J Endod. 1984;10(12):580-583.

70. Torabinejad M, Kettering JD, McGraw JC, et al. Factors associated with endodontic interappointment emergencies of teeth with necrotic pulps. J Endod. 1988;14:261-266.

71. Torabinejad M, Walton R. Endodontics: principles and practice, ed 4. St. Louis: Saunders; 2009.

72. Trope ME, Delano EO, Orstavik D. Endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis: single vs. multivisit treatment. J Endod. 1999;25:345.

73. Tsesis I, Faivishevsky V, Fuss Z, Zukerman O. Flare-ups after endodontic treatment: a meta-analysis of literature. J Endod. 2008;34:1177-1181.

74. Turkun M, Cengiz T. The effects of sodium hypochlorite and calcium hydroxide in tissue dissolution and root canal cleanliness. Int Endod J. 1997;30:335.

75. Walton RE, Chiappinelli J. Prophylactic penicillin: effect on posttreatment symptoms following root canal treatment of asymptomatic periapical pathosis. J Endod. 1993;19:466.

76. Walton R, Fouad A. Endodontic interappointment flare-ups: a prospective study of incidence and related factors. J Endod. 1992;18:172-177.

77. Weiger R, Axmann-Krcmar D, Löst C. Prognosis of conventional root canal treatment reconsidered. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1998;14(1):1-9.

78. Weiger R, Rosendahl R, Lost C. Influence of calcium hydroxide intracanal dressings on the prognosis of teeth with endodontically induced periapical lesions. Int Endod J. 2000;33:219.

79. Weine FS, Healey HJ, Theiss EP. Endodontic emergency dilemma: leave teeth open or keep it closed? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1975;40:531.