Hygiene

• Describe factors that influence personal hygiene practices.

• Discuss the role that critical thinking plays in providing hygiene.

• Conduct a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s total hygiene needs.

• Discuss conditions that place patients at risk for impaired skin integrity.

• Discuss factors that influence the condition of the nails and feet.

• Explain the importance of foot care for the patient with diabetes.

• Discuss conditions that place patients at risk for impaired oral mucous membranes.

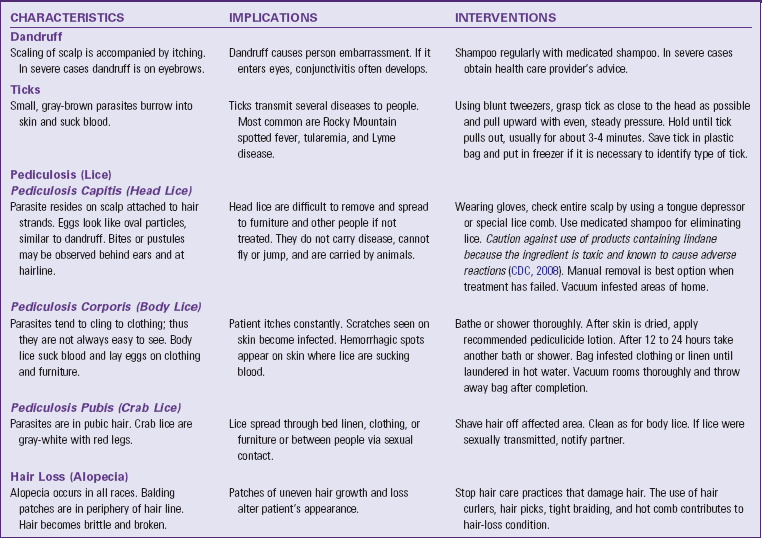

• List common hair and scalp problems and their related interventions.

• Describe how hygiene care for the older adult differs from that for the younger patient.

• Discuss different approaches used in maintaining a patient’s comfort and safety during hygiene care.

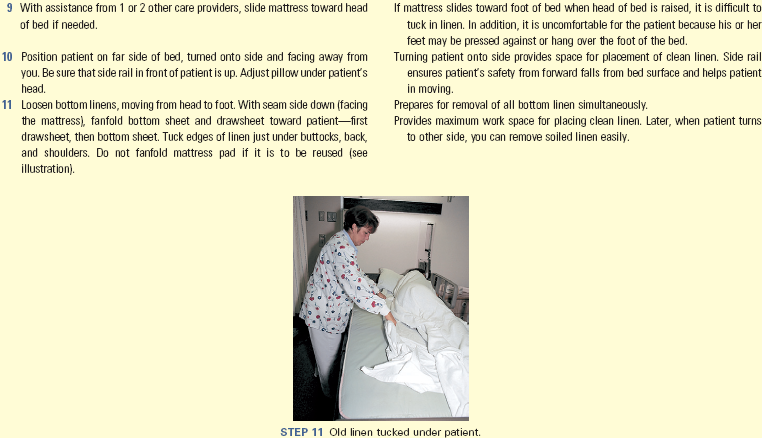

• Successfully perform hygiene procedures for the care of the skin, perineum, feet and nails, mouth, eyes, ears, and nose.

• Adapt hygiene care for a patient who is cognitively impaired.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Personal hygiene affects patients’ comfort, safety, and well-being. Hygiene care includes cleaning and grooming activities that maintain personal body cleanliness and appearance. Personal hygiene activities such as taking a bath or shower, brushing and flossing the teeth, washing and grooming the hair, and performing nail care promote comfort and relaxation, foster a positive self-image, promote healthy skin, and help prevent infection and disease. Healthy people fulfill their own hygiene needs; but when ill or physically or emotionally challenged, people often require some degree of assistance with hygiene care. A variety of personal, social, and cultural factors influence hygiene practices.

In both agency and home care settings, determine a patient’s ability to perform self-care and provide hygiene care according to individual needs and preferences. In addition, in the home setting help the patient and family adapt hygiene techniques and approaches. Use the close contact required for hygiene care to promote a caring therapeutic relationship and provide needed patient teaching and counseling. Integrate other nursing activities during hygiene care, including assessment and interventions such as range-of-motion (ROM) exercises, application of dressings, or inspection and care of intravenous (IV) sites. During hygiene care preserve as much of the patient’s independence as possible, assess his or her ability to perform hygiene care, ensure privacy, convey respect, and foster his or her physical comfort.

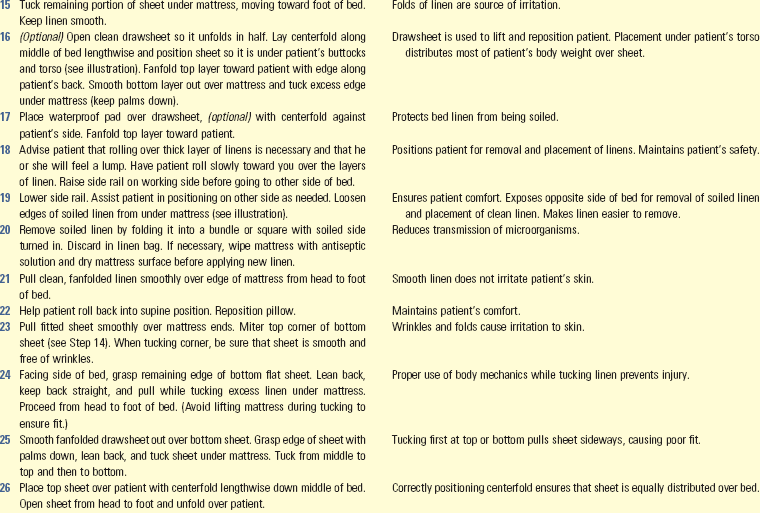

Scientific Knowledge Base

Proper hygiene care requires an understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the skin, nails, oral cavity, eyes, ears, and nose. The skin and mucosal cells exchange oxygen, nutrients, and fluids with underlying blood vessels. The cells require adequate nutrition, hydration, and circulation to resist injury and disease. Good hygiene techniques promote the normal structure and function of these tissues.

Apply knowledge of pathophysiology to provide preventive hygiene care. Recognize disease states that create changes in the integument, oral cavity, and sensory organs. For example, diabetes mellitus often results in chronic vascular changes that impair healing of the skin and mucosa. In the early stages of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), fungal infections of the oral cavity are common. Paralysis of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) eliminates the blink reflex, causing risk of corneal drying. In the presence of conditions such as these, adapt hygiene practices to minimize injury. Use time spent providing hygiene care to identify abnormalities and initiate appropriate actions to prevent further injury to sensitive tissues.

The Skin

The skin serves several functions, including protection, secretion, excretion, body temperature regulation, and cutaneous sensation (Table 39-1). It consists of two primary layers: the epidermis and the dermis. Just beneath the skin lies the subcutaneous tissue (also known as the hypodermis), which shares some of the protective functions of the skin.

TABLE 39-1

Function of the Skin and Implications for Care

| FUNCTION/DESCRIPTION | IMPLICATIONS FOR CARE |

| Protection | |

| Epidermis is relatively impermeable layer that prevents entrance of microorganisms. Although microorganisms reside on skin surface and in hair follicles, relative dryness of surface of skin inhibits bacterial growth. Sebum removes bacteria from hair follicles. Acidic pH of skin further retards bacterial growth. | Weakening of epidermis occurs by scraping or stripping its surface (e.g., use of dry razors, tape removal, improper turning or positioning techniques). Excessive dryness causes cracks and breaks in skin and mucosa that allow bacteria to enter. Emollients soften skin and prevent moisture loss, soaking skin improves moisture retention, and hydrating mucosa prevents dryness. However, constant exposure of skin to moisture causes maceration or softening, interrupting dermal integrity and promoting ulcer formation and bacterial growth. Keep bed linen and clothing dry. Misuse of soap, detergents, cosmetics, deodorant, and depilatories cause chemical irritation. Alkaline soaps neutralize the protective acid condition of skin. Cleaning skin removes excess oil, sweat, dead skin cells, and dirt, which promote bacterial growth. |

| Sensation | |

| Skin contains sensory organs for touch, pain, heat, cold, and pressure. | Minimize friction to avoid loss of stratum corneum, which results in development of pressure ulcers. Smoothing linen removes sources of mechanical irritation. Remove rings from fingers to prevent accidentally injuring patient’s skin. Make sure that bath water is not excessively hot or cold. |

| Temperature Regulation | |

| Radiation, evaporation, conduction, and convection control body temperature. | Factors that interfere with heat loss alter temperature control. Wet bed linen or gowns interfere with convection and conduction. Excess blankets or bed coverings interfere with heat loss through radiation and conduction. Coverings promote heat conservation. |

| Excretion and Secretion | |

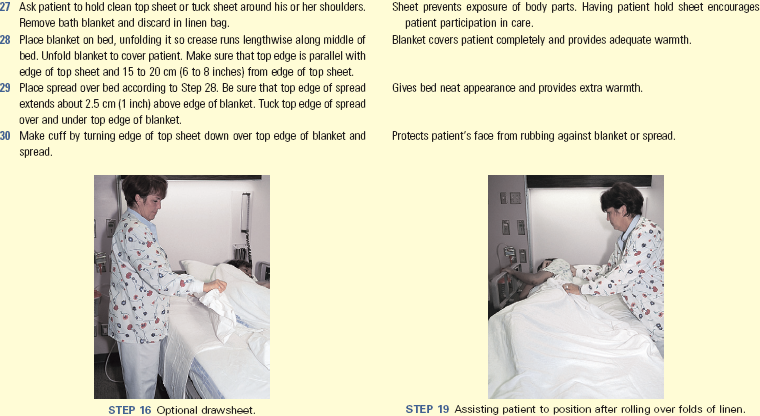

| Sweat promotes heat loss by evaporation. Sebum lubricates skin and hair. | Perspiration and oil harbor microorganisms. Bathing removes excess body secretions; although, if excessive, it causes dry skin. |

Several thin layers of epithelial cells comprise the outer layer, or epidermis; these cells shield underlying tissue against water loss and injury and prevent entry of disease-producing microorganisms. The innermost layer of the epidermis generates new cells to replace the dead cells that the outer surface of the skin continuously sheds. Bacteria commonly reside on the outer epidermis. These resident bacteria are normal flora (see Chapter 28) that do not cause disease but instead inhibit the multiplication of disease-causing microorganisms.

Bundles of collagen and elastic fibers form the thicker dermis that underlies and supports the epidermis. Nerve fibers, blood vessels, sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles run through the dermal layers. Sebaceous glands secrete sebum, an oily, odorous fluid, into the hair follicles. Sebum softens and lubricates the skin and slows water loss from the skin when the humidity is low. More important, sebum has bactericidal action.

The subcutaneous tissue layer contains blood vessels, nerves, lymph, and loose connective tissue filled with fat cells. The fatty tissue functions as a heat insulator for the body. Subcutaneous tissue also supports upper skin layers to withstand stresses and pressure without injury and anchors the skin loosely to underlying structures such as muscle. Very little subcutaneous tissue underlies the oral mucosa.

The skin often reflects a change in physical condition by alterations in color, thickness, texture, turgor, temperature, and hydration (see Chapter 30). As long as the skin remains intact and healthy, its physiological function remains optimal. Hygiene practices frequently influence skin status and can have both beneficial and negative effects on the skin. For example, too-frequent bathing and use of hot water frequently leads to dry, flaky skin and loss of protective oils.

The Feet, Hands, and Nails

The feet, hands, and nails often require special attention to prevent infection, odor, and injury. The condition of a patient’s hands and feet influences the ability to perform hygiene care. Without the ability to bear weight, ambulate, or manipulate the hands, the patient is at risk for losing self-care ability.

A wide range of dexterity exists in the hand because of the movement between the thumb and fingers. Any condition that interferes with movement of the hand (e.g., superficial or deep pain or joint inflammation) impairs a patient’s self-care abilities. Foot pain often changes the patient’s gait, causing strain on different joints and muscle groups. Discomfort while standing or walking limits self-care abilities.

The nails grow from the root of the nail bed, which is located in the skin at the nail groove, hidden by the fold of skin called the cuticle. A scalelike modification of the epidermis forms the visible part of the nail (nail body), which has a crescent-shaped white area known as the lunula. Under the nail lies a layer of epithelium called the nail bed. A normal healthy nail appears transparent, smooth, and convex, with a pink nail bed and translucent white tip. Disease causes changes in the shape, thickness, and curvature of the nail (see Chapter 30).

The Oral Cavity

The oral cavity consists of the lips surrounding the opening of the mouth, the cheeks running along the sidewalls of the cavity, the tongue and its muscles, and the hard and soft palate. The mucous membrane, continuous with the skin, lines the oral cavity. The floor of the mouth and the undersurface of the tongue are richly supplied with blood vessels. Normal oral mucosa glistens and is pink, soft, moist, smooth, and without lesions. Ulcerations or trauma frequently result in significant bleeding. Several glands within and outside the oral cavity secrete saliva. Saliva cleanses the mouth, dissolves food chemicals to promote taste, moistens food to facilitate bolus formation, and contains enzymes that start breakdown of starchy foods. The effects of medications, exposure to radiation, dehydration, and mouth breathing impair salivary secretion in the mouth. Strong sympathetic nervous system stimulation almost completely inhibits the release of saliva and results in xerostomia or dry mouth.

The teeth lie in sockets in the gum-covered mandible and maxilla; they tear and grind ingested food so it can be mixed with saliva and swallowed for digestion. A normal tooth consists of the crown, neck, and root. The enamel-covered crown extends above the gingiva or gum, which normally surrounds the tooth like a tight collar. A constricted portion of the tooth called the neck connects the crown and the root; the root is embedded in the jawbone. The periodontal membrane lies just below the gum margins, surrounds a tooth, and holds it firmly in place. Healthy teeth appear white, smooth, shiny, and properly aligned.

Difficulty in chewing develops when surrounding gum tissues become inflamed or infected or when teeth are lost or become loosened. Regular oral hygiene helps to prevent gingivitis (i.e., inflammation of the gums) and dental caries (i.e., tooth decay produced by interaction of food with bacteria).

The Hair

Hair growth, distribution, and pattern indicate a person’s general health status. Hormonal changes, nutrition, emotional and physical stress, aging, infection, and some illnesses affect hair characteristics. The hair shaft itself is lifeless, and physiological factors do not directly affect it. However, hormonal and nutrient deficiencies of the hair follicle cause changes in hair color or condition.

The Eyes, Ears, and Nose

When providing hygiene care, the eyes, ears, and nose require careful attention. Chapter 30 describes the structure and function of these organs. Clean the sensitive sensory tissues in a way that prevents injury and discomfort for a patient, such as using care not to get soap in his or her eyes. In addition, the time you spend with your patient during hygiene provides an excellent opportunity to ask if there are any changes in vision, hearing, or sense of smell.

Nursing Knowledge Base

A number of factors influence personal preferences for hygiene and the ability to maintain hygiene practices. Since no two individuals perform hygiene care in the same manner, you individualize patient care based on learning about his or her unique hygiene practices and preferences. Individualized hygiene care requires use of therapeutic communication skills to promote the therapeutic relationship. In addition, use the opportunity provided during hygiene care to assess a patient’s health promotion practices, emotional status, and health care education needs. Be aware that developmental changes influence the need and preferences for type of hygiene care.

Factors Influencing Hygiene

Social groups influence hygiene preferences and practices, including the type of hygiene products used and the nature and frequency of personal care practices. Parents and caregivers perform hygiene care for infants and young children. Family customs play a major role during childhood in determining hygiene practices such as the frequency of bathing, the time of day bathing is performed, and even whether certain hygiene practices such as brushing of the teeth or flossing are performed. As children enter adolescence, peer groups and media often influence hygiene practices. For example, some young girls become more interested in their personal appearance and begin to wear makeup. During the adult years involvement with friends and work groups shape the expectations that people have about personal appearance. Some older adults’ hygiene practices change because of changes in living conditions and available resources.

Personal Preferences

Patients have individual desires and preferences about when to perform hygiene and grooming care. Some patients prefer to shower, whereas others prefer to bathe. Patients select different hygiene and grooming products according to personal preferences. Knowing patients’ personal preferences promotes individualized care. Help the patient develop new hygiene practices when indicated by an illness or condition. For example, you need to teach a patient with diabetes proper foot hygiene. Safe and effective patient-centered nursing care elicits individual preferences, allows patients to make personal choices whenever possible, and promotes patient involvement and independence (Cronenwett et al., 2007).

Body Image

Body image is a person’s subjective concept of his or her body, including physical appearance, structure, or function (see Chapter 33). Body image affects the way in which individuals maintain personal hygiene. If a patient maintains a neatly groomed appearance, be sure to consider the details of grooming when planning care and consult with the patient before making decisions about how to provide hygiene care. Patients who appear unkempt or uninterested in hygiene sometimes need education about its importance or further assessment regarding their ability to participate with daily hygiene.

Surgery, illness, or a change in emotional or functional status often affects a patient’s body image. Discomfort and pain, emotional stress, or fatigue diminish the ability or desire to perform hygiene self-care and require extra effort to promote hygiene and grooming.

Socioeconomic Status

A person’s economic resources influence the type and extent of hygiene practices used. Be sensitive in considering that the patient’s economic status influences the ability to regularly maintain hygiene. He or she may not be able to afford desired basic supplies such as deodorant, shampoo, and toothpaste. A patient may need to modify the home environment by adding safety devices such as nonskid surfaces and grab bars in the bath to perform hygiene self-care safely. When he or she lacks socioeconomic resources, it becomes difficult to participate and take a responsible role in health promotion activities such as basic hygiene.

Health Beliefs and Motivation

Knowledge about the importance of hygiene and its implications for well-being influences hygiene practices. However, knowledge alone is not enough. Motivation also plays a key role in a patient’s hygiene practices. Patient teaching is often needed to foster hygiene self-care. Provide information that focuses on a patient’s health-related issues relevant to the desired hygiene care behaviors. Patient perceptions of the benefits of hygiene care and the susceptibility to and seriousness of developing a problem affect the motivation to change behavior (Pender, Murdaugh, and Parsons, 2011). For example, do patients perceive that they are at risk for dental disease, that dental disease is serious, and that brushing and flossing are effective in reducing risk? When they recognize that there is a risk and that they can take reasonable action without negative consequences, they are more likely to be receptive to nurses’ counseling and teaching efforts.

Cultural Variables

Cultural beliefs and personal values influence hygiene care (Box 39-1). People from diverse cultural backgrounds frequently follow different self-care practices (see Chapter 9). Maintaining cleanliness does not hold the same importance for some ethnic or social groups as it does for others (Galanti, 2008). In North America it is common to bathe or shower daily and use deodorant to prevent body odors. However, people from some cultures are not sensitive to body odors, prefer to bathe less frequently, and do not use deodorant. Some homeless people believe that a layer of dirt helps protect them from becoming sick (Galanti, 2008). Do not express disapproval when caring for patients whose hygiene practices differ from yours. Avoid forcing changes in hygiene practices unless the practices affect the patient’s health. In these situations use tact, provide information, and allow choices. Religious beliefs associated with culture sometimes influence hygiene practices. Facilitate a patient’s religious practices whenever possible. For example, Muslim patients often remove their shoes and assume different positions for prayer. This increases the risk of developing foot pathology such as calluses on the toes and lateral ankles. When caring for Muslim patients who have diabetes mellitus, you need to be supportive of religious practices while also stressing the need to be diligent in inspecting the feet after prayer sessions for any blisters or calluses.

Developmental Stage

The normal process of aging influences the condition of body tissues and structures. A patient’s developmental stage affects the ability of the patient to perform hygiene care and the type of care needed. Apply knowledge of developmental changes as you assess your patients and plan, implement, and evaluate hygiene care.

Skin: The neonate’s skin is relatively immature at birth. The epidermis and dermis are loosely bound together, and the skin is very thin. Friction against the skin layers causes bruising. Handle the neonate carefully during bathing. Any break in the skin easily results in an infection.

A toddler’s skin layers become more tightly bound together. Thus the child has a greater resistance to infection and skin irritation. However, because of his or her more active play and the absence of established hygiene habits, parents and caregivers need to provide thorough hygiene and teach good hygiene habits.

During adolescence the growth and maturation of the integument increases. In girls estrogen secretion causes the skin to become soft, smooth, and thicker with increased vascularity. In boys male hormones produce an increased thickness of the skin with some darkening in color. Sebaceous glands become more active, predisposing adolescents to acne (i.e., active inflammation of the sebaceous glands accompanied by pimples). Sweat glands become fully functional during puberty. Adolescents usually begin to use antiperspirants. More frequent bathing and shampooing also become necessary to reduce body odors and eliminate oily hair.

The condition of the adult’s skin depends on hygiene practices and exposure to environmental irritants. Normally the skin is elastic, well hydrated, firm, and smooth. When an adult bathes frequently or is exposed to an environment with low humidity, it becomes dry and flaky. With aging the rate of epidermal cell replacement slows, and the skin thins and loses resiliency. Moisture leaves the skin, increasing the risk for bruising and other types of injury. As the production of lubricating substances from skin glands decreases, the skin becomes dry and itchy (Meiner, 2011). These changes warrant caution when turning and repositioning older adults and when bathing. Too-frequent bathing and bathing with hot water or harsh soap cause the skin to become excessively dry (American Academy of Dermatology, 2009).

Feet and Nails: With aging and continued exposure the patient is more likely to develop chronic foot problems as a result of poor foot care, improper fit of footwear, and systemic disease. Older adults do not always have the strength, flexibility, visual acuity, or manual dexterity to care for their feet and nails. Long or roughened nails lead to traumatic nail avulsions in which the nail plate is torn from the nail bed (Berridge, 2009).

Older adults often have dry feet because of a decrease in sebaceous gland secretion and dehydration of epidermal cells. Common problems of the feet affecting older adults include corns, calluses, bunions, hammertoe, and fungal infections (Wright, 2009). Older adults frequently complain of foot pain (Meiner, 2011). Painful feet result from a variety of congenital deformities, weak structure, injuries, and diseases such as diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis.

The Mouth: At approximately 6 to 8 months of age, infants begin teething. The first permanent (secondary) teeth erupt at about 6 years of age (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). From adolescence, when all of the permanent teeth are in place, through middle adulthood, the teeth and gums remain healthy if a person follows healthy eating patterns and dental care. Avoiding fermentable carbohydrates and sticky sweets helps to keep the teeth free of caries. In addition, regular brushing and flossing help to prevent caries and periodontal disease.

As a person ages, numerous factors result in poor oral health. These include age-related changes of the mouth, chronic disease such as diabetes, physical disabilities involving hand grasp or strength affecting the ability to perform oral care, lack of attention to oral care, and prescribed medications that have oral side effects. Gums lose vascularity and tissue elasticity, which causes dentures to fit poorly. If the older adult becomes edentulous (i.e., without teeth) and wears complete or partial dentures, include assessment of underlying gums and palate.

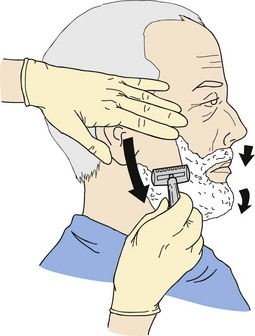

Hair: Throughout life changes in the growth, distribution, and condition of the hair influence hair hygiene. As males reach adolescence, shaving becomes a part of routine grooming. Young girls who reach puberty often begin to shave their legs and axillae. With aging, as scalp hair becomes thinner and drier, shampooing is usually performed less frequently.

Eyes, Ears, and Nose: Chapter 49 addresses changes in hearing, vision, and olfaction across the life span as a result of growth and development. Alterations in sensory function often require modifications in hygiene care. Use your knowledge of developmental changes when planning hygienic care.

Physical Condition

Patients with certain types of physical limitations or disabilities associated with disease and injury lack the physical energy and dexterity to perform hygiene self-care safely. A patient whose arm is in a cast or who has an IV line needs help with hygiene care. A weakened grasp resulting from arthritis, stroke, or muscular disorders makes using a toothbrush, washcloth, or hairbrush difficult or ineffective. Sensory deficits not only alter a patient’s ability to perform care but also place the patient at risk for injury. Safety is a priority for a patient with a sensory deficit. For example, the inability to feel that the water is too hot can lead to a burn injury during bathing.

Chronic illnesses such as cardiac disease, cancer, neurological disorders, and some mental health illnesses often exhaust or incapacitate patients. Patients who become fatigued frequently need to have complete hygiene care provided. Include periods of rest during care to allow patients who are fatigued the opportunity to participate in their care. Pain often accompanies illness and injury, limiting a patient’s ability to tolerate hygiene and grooming activities or perform self-care. Pain frequently limits ROM, resulting in impaired use of the arms or hands or limited ability to move about in the environment, impairing the ability to perform hygiene self-care. Sedation and drowsiness associated with analgesics used for pain management also limit a patient’s ability to safely participate in care.

Limited mobility caused by a variety of factors (e.g., physical injury, weakness, surgery, pain, prolonged inactivity, medication effect, and presence of indwelling catheter or IV line) decreases a patient’s ability to perform hygiene self-care activities safely. Individualized care considers a patient’s ability to perform care, the amount of assistance needed, and the need for assistive and safety devices to facilitate safe hygiene care.

Acute and chronic cognitive impairments such as stroke, brain injury, psychoses, and dementia often result in the inability to perform self-care independently. When people with cognitive impairments are unaware of their hygiene and grooming needs, they become fearful and agitated during hygiene care, resulting in aggressive behavior (Hoeffer et al., 2006). Safe, effective patient care takes the effect of cognitive impairment on hygiene care into consideration and allows for appropriate modifications.

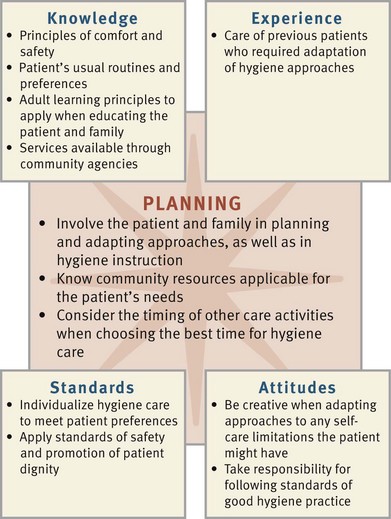

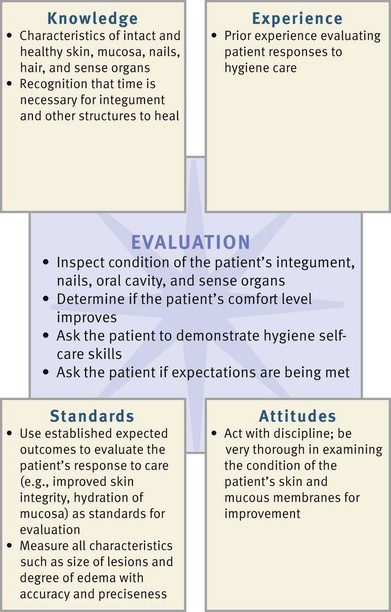

Critical Thinking

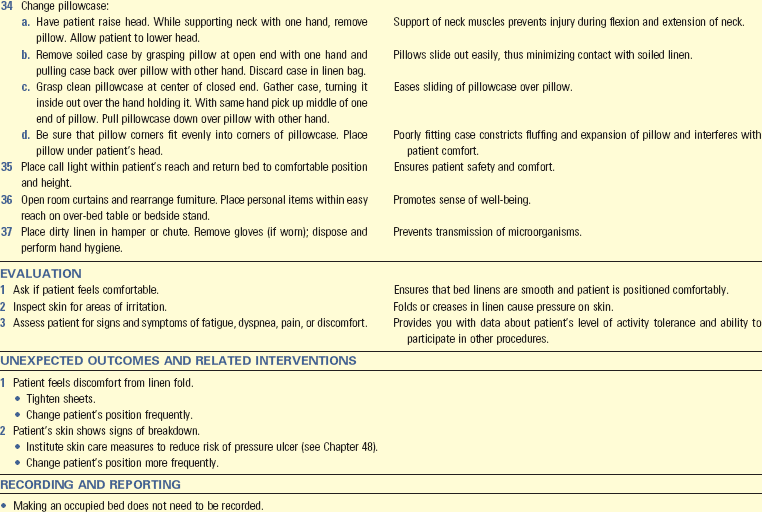

Effective critical thinking requires synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the information necessary to analyze data and make decisions regarding care. A patient’s condition is always changing, requiring ongoing critical thinking. During assessment consider all elements that build toward making appropriate nursing diagnoses (Fig. 39-1). Apply the elements of critical thinking as you use the nursing process to meet patients’ hygiene needs.

FIG. 39-1 Critical thinking model for hygiene assessment. ADA, American Diabetes Association; NPUAP, National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; WOCN, Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses.

Integrate nursing knowledge with knowledge from other disciplines. For example, the patient with diabetes mellitus has special needs for nail and foot care. Knowledge about the pathophysiology of diabetes and its potential effects on his or her peripheral circulation and sensory status provides the scientific knowledge base needed to implement safe and effective foot care. In addition, integrate knowledge about developmental and cultural influences as you identify and meet hygiene needs.

Be aware of the impact of critical thinking attitudes as you plan and implement care. For example, think creatively to help patients adapt existing hygiene practices or develop new hygiene practices when illness or loss of function impairs self-care abilities. Be nonjudgmental and confident when providing care. Because of variations in individual patients’ physical status and hygiene practices, you need to approach care with an attitude of flexibility. For example, when caring for a patient who is fatigued, you pace activities and plan rest periods during hygiene care to prevent exhaustion.

Draw on your own experiences as you assist with your patients’ hygiene care. Reflect on times when you helped family members or others close to you with their hygiene. Usually an early clinical experience involves providing or assisting with hygiene care for a patient. Finally rely on professional standards such as those for skin and foot care from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and specialty nursing groups such as Wound Ostomy Continency Nurses (WOCN) when planning care to meet a patient’s hygiene needs. As your experience and knowledge grow, your comfort and expertise in meeting the individualized hygiene needs of your patients increase.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Assessment

During the assessment process thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care. Assessment of a patient’s hygiene status and self-care abilities requires you to complete a nursing history and perform a physical assessment. You do not routinely assess all body regions before providing hygiene. However, you need to conduct a brief history to determine priority areas and help you plan individualized hygiene care. Assessment of a patient’s ability to provide hygiene self-care helps you make decisions about the kind and amount of hygiene care to provide and how much the patient can be encouraged to participate in care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Providing safe, quality hygiene care requires a complete awareness of the patient’s perspective. Because patients have varying expectations, you need to avoid making personal hygiene care a simple routine. Complete a nursing history that not only elicits personal preferences but also addresses the patient’s cultural or religious customs and beliefs.

Explore the patient’s viewpoint regarding hygiene care by asking him or her about preferred personal hygiene and grooming practices. Ask about personal care products desired and preferences such as frequency, time of day, and amount of assistance needed. Also ask questions such as “To make you most comfortable and feel at home, how can I best perform your bath and personal care?” Determine the patient’s awareness of any hygiene-related problems and his or her knowledge and ability to perform hygiene care measures (Box 39-2). Learning a patient’s expectations and applying them in practice fosters a caring relationship. Fully individualizing hygiene care shows the nurse’s respect for the patient’s needs. As you learn what the patient expects, you incorporate this information into a plan of care.

Assessment of Self-Care Ability

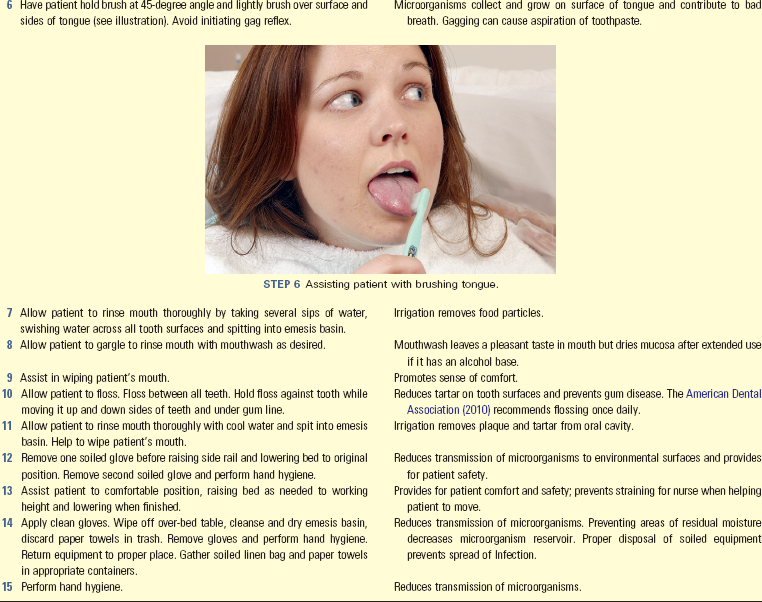

Assess a patient’s physical status as it relates to ability to perform or assist with hygiene care safely and efficiently; include assessment of the patient’s muscle strength, flexibility, balance, visual acuity, and ability to detect thermal and tactile stimuli. Determine your patient’s mental status, including orientation and cognitive function (see Chapter 30). The patient with impaired cognitive function may be unaware of hygiene care needs or less able to follow instructions and assist with care. Observe the patient performing hygiene care, noting complaints or physical manifestations that suggest activity intolerance. Assess respiratory rate and effort, skin color, and pulse rate. Ask questions to assess the patient for dizziness, weakness, or fatigue. To determine the amount of assistance the patient needs, observe him or her performing care activities such as brushing teeth or combing hair (Fig. 39-2). Patients who have limited upper-extremity mobility, reduced vision, fatigue, or inability to grasp small objects require assistance. For example, current evidence shows that older adults who have poor hand function have more dental plaque when they perform their own oral care (Padilha et al., 2007). Also note the presence of equipment such as IV lines or urinary catheters. When patients have self-care limitations, family may assist with care. Determine how the family can help the patient, how often they can provide this assistance, and what their feelings are about being caregivers. In addition, assess the home environment and its influence on the patient’s hygiene practices. Are there barriers in the home that affect his or her self-care abilities? Water faucets that are too tight to adjust easily, bathtubs with high sides, and a bathroom too small to fit a chair in front of a sink are a few examples.

Assessment of the Skin

Perform an assessment of the skin (see Chapter 30), noting color, texture, thickness, turgor, temperature, and hydration. In the healthy person the skin is smooth, warm, and supple with good turgor. Pay special attention to the presence and condition of any lesions. Note dryness of the skin indicated by flaking, redness, scaling, and cracking. Discovering manifestations of common skin problems influences how you administer hygiene care (Table 39-2).

TABLE 39-2

Determine the degree of cleanliness by observing the appearance of the skin and detecting body odors that possibly indicate inadequate cleansing or excessive perspiration caused by fever or pain. Inspect less obvious or difficult-to-reach skin surfaces such as under the breasts or scrotum, around the female patient’s perineum, or in the groin for redness, excessive moisture, and soiling or debris. Separate skinfolds for observation and palpation.

Be attentive to characteristics of skin problems most influenced by hygiene measures. Is the skin dry from too much bathing or from use of hot water or irritating soap? Does the patient have a rash caused by an allergic reaction to a skin care product? Certain conditions place patients at risk for impaired skin integrity (Box 39-3). Because of increased risk be particularly alert when assessing patients with reduced sensation, impaired circulation, nutrition or hydration alterations, body secretions, incontinence, altered cognition, external devices, and decreased mobility. Patients may be unaware of skin problems because they are unable to feel pain or pressure or see their skin in some places (e.g., the back or the feet). Carefully assess the skin under orthopedic devices (braces, splints, casts) and beneath items such as antiembolic stockings and tape. Assess the condition and cleanliness of the perineal and anal areas during hygiene care and when the patient requires toileting assistance. When prolonged contact of urine or feces occurs such as with diarrhea or incontinence, skin breakdown often results. Most people consider these areas to be private. Use sensitivity in your approach.

When caring for patients with dark skin pigmentation, be aware of assessment techniques and skin characteristics unique to highly pigmented skin (see Chapter 30). Carefully assess the skin in dark-skinned patients at risk for pressure ulcers (see Chapter 48).

Assessment of the Feet and Nails

A variety of common foot and nail problems can be caused by inadequate hygiene and are actually detected during hygiene care. Problems sometimes result from abuse or poor care of the feet and hands such as nail biting or trimming nails improperly, exposure to harsh chemicals, and wearing poorly fitting shoes. Question the patient to determine type of footwear and usual foot and nail care practices.

Examine all skin surfaces of the feet, including the areas between the toes and over the entire sole of the foot. Poorly fitting shoes often irritate the heels, soles, and sides of the feet. Inspection of the feet for lesions includes noting areas of dryness, inflammation, or cracking. Chronic foot problems are common in older adults who often experience dry feet because of a decrease in sebaceous gland secretion, dehydration, or poor condition of footwear.

People are often unaware of foot or nail problems until pain or discomfort occurs. Assess patients with diseases that affect peripheral circulation and sensation for the adequacy of circulation and sensation of the feet. Foot ulceration is the most common single precursor to lower-extremity amputations among people with diabetes (Frykberg et al., 2006). Daily inspection and preventive foot care help maintain ulcer-free feet. Palpate the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial pulses and assess for intact sensation to light touch, pinprick, and temperature (see Chapter 30).

Observe the patient’s gait. Painful foot disorders or decreased sensation cause limping or an unnatural gait. Ask whether the patient has foot discomfort and determine factors that aggravate the pain. Foot problems sometimes result from bone or muscular alterations or wearing poorly fitting footwear.

Inspect the condition of the fingernails and toenails, looking for lesions, dryness, inflammation, or cracking, which are often associated with a variety of common nail problems (Table 39-3). The cuticle that surrounds the nail can grow over it and become inflamed if nail care is not performed correctly and periodically. Ask women whether they frequently polish their nails and use polish remover because chemicals in these products cause excessive nail dryness. Disease changes the shape and curvature of the nails (see Chapter 30). Inflammatory lesions and fungus of the nail bed cause thickened, horny nails that separate from the nail bed.

TABLE 39-3

| CHARACTERISTICS | IMPLICATIONS | INTERVENTIONS |

| Callus | ||

| Thickened portion of epidermis consists of mass of horny, keratotic cells. Callus is usually flat, painless, and found on undersurface of foot or palm of hand. | Local friction or pressure causes callus formation, which causes discomfort when wearing tight shoes. | Soft-sole shoes with insoles are recommended. Advise patient to wear gloves when using tools or objects that create friction on palmar surfaces. Advise patients, especially with callus formation, not to self-treat but seek interventions from a podiatrist. |

| Corns | ||

| Friction and pressure from ill-fitting or loose shoes causes keratosis. It is seen mainly on or between toes, over bony prominence. Corn is usually cone shaped, round, and raised. Soft corns are macerated. | Compresses the underlying dermis, making it thin and tender. Pain is aggravated when wearing tight shoes. Tissue becomes attached to bone if allowed to grow. Patient suffers alteration in gait resulting from pain. | Surgical removal is necessary, depending on severity of pain and size of corn. Avoid use of oval corn pads, which increase pressure on toes and reduce circulation. Warm water soaks soften corns before gentle rubbing with a callus file or pumice stone (consult with health care provider). Wider and softer shoes, especially shoes with a wider toe box, are helpful. |

| Plantar Warts | ||

| Fungating lesion appears on sole of foot and is caused by the papilloma virus. | Some warts are contagious. They are painful and make walking difficult. | Treatment ordered by health care provider often includes applications of salicylic acid, electrodessication (burning with electrical spark), or freezing with solid carbon dioxide. |

| Athlete’s Foot (Tinea Pedis) | ||

| Athlete’s foot is fungal infection of foot; scaling and cracking of skin occurs between toes and on soles of feet. Small blisters containing fluid appear. | Athlete’s foot spreads to other body parts, especially hands. It is contagious and frequently recurs. | Make sure that feet are well ventilated. Drying feet well after bathing and applying powder help prevent infection. Wearing clean socks or stockings reduces incidence. Health care provider orders application of griseofulvin, miconazole, or tolnaftate. |

| Ingrown Nails | ||

| Toenail or fingernail grows inward into soft tissue around nail. Ingrown nail often results from improper nail trimming. | Ingrown nails cause localized pain when pressure is applied. | Treatment is frequent hot soaks in antiseptic solution and removal of part of nail that has grown into skin. Instruct patient in proper nail-trimming techniques and refer to podiatrist. |

| Foot Odors | ||

| Foot odors are result of excess perspiration, promoting microorganism growth. | Condition causes discomfort because of excess perspiration. | Frequent washing, use of foot deodorants and powders, and wearing clean footwear prevent or reduce problem. |

Assessment of the Oral Cavity

The condition of the oral cavity reflects overall health and also indicates oral hygiene needs. Inspect all areas of the mouth carefully for color, hydration, texture, and lesions (see Chapter 30). Patients frequently develop common oral problems as a result of inadequate oral care or consequence of disease (e.g., oral malignancy) or as a side effect of treatments such as radiation and chemotherapy. These problems include receding gum tissue, inflamed gums (gingivitis), a coated tongue, glossitis (inflamed tongue), discolored teeth (particularly along gum margins), dental caries, missing teeth, and halitosis (foul-smelling breath). Localized pain and infection commonly accompany oral problems. Apply clean gloves to palpate any tender areas or lesions. Observe for cleanliness and use olfaction to detect halitosis. If you identify any oral problems, notify the patient’s health care provider. Early identification of poor oral hygiene practices and common oral problems reduces the risk for gum disease and dental caries.

Assessment of the Hair and Hair Care

Before performing hair care, assess the condition of the patient’s hair and scalp. Findings help determine the frequency and type of care needed. Normally the hair is clean, shiny, and untangled; and the scalp is clear of lesions. Table 39-4 summarizes hair and scalp problems with implications and interventions.

Observe the patient’s ability to perform hair care. A person’s appearance and feeling of well-being often are related to the way the hair looks and feels. Illness, disability, and conditions such as arthritis, fatigue, and the presence of physical barriers (e.g., cast or IV access) alter a patient’s ability to maintain daily hair care.

In community health and home care settings it is particularly important to inspect the hair for lice so you can provide appropriate hygienic treatment. If you suspect pediculosis capitis (head lice), guard against self-infestations by handwashing and using gloves or tongue blades to inspect the patient’s hair.

The loss of hair (alopecia) results from the effects of chemotherapy medications, hormonal changes, or improper hair care practices. Alopecia often appears as brittle and broken hair in the hair line that progresses to bald patches. If noted, be sure to question the patient about specific hair care practices, especially the use of chemicals and heat application during hair care.

Assessment of the Eyes, Ears, and Nose

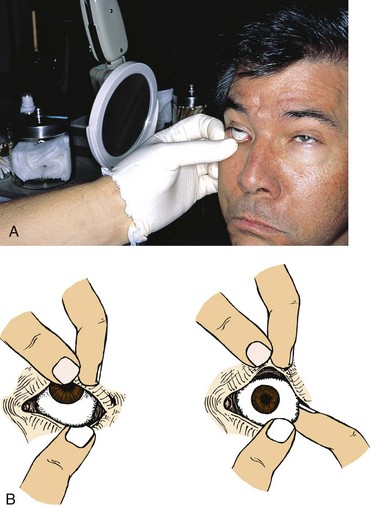

Examine the condition and function of the eyes, ears, and nose (see Chapter 30). The healthy eye is not inflamed and is without drainage. The presence of redness indicates allergic or infectious conjunctivitis, which can be highly contagious. The crusty drainage associated with conjunctivitis easily spreads from one eye to the other. Wear clean gloves to examine the eyes and perform proper hand hygiene before and after the examination. Determine if a patient wears contact lenses, especially when he or she enters the health care agency in an unresponsive or confused state. To determine if a contact lens is present, stand to the side of the patient’s eyes and observe the corneas for the presence of a soft or rigid lens. Also observe the sclera because the lens may have shifted off the cornea. An undetected contact lens causes corneal injury when left in place too long.

Assessment of the external ear structures includes inspection of the auricle and external ear canal (see Chapter 30). Observe for the presence of accumulated cerumen (earwax) or drainage in the ear canal and local inflammation. Question patients about tenderness on palpation or the presence of pain and ask how they usually clean their ears.

Inspect the nares for signs of inflammation, discharge, lesions, edema, and deformity (see Chapter 30). The nasal mucosa is normally pink and clear and has little or no discharge. Allergies cause a clear, watery discharge. If patients have any form of tubing exiting the nose (e.g., nasogastric), observe for tissue damage, localized tenderness, inflammation, drainage, and bleeding where the tubing comes in contact with the nares..

Use of Sensory Aids

For patients who wear eyeglasses, contact lenses, artificial eyes, or hearing aids, assess their knowledge and methods used for care and have them describe the typical approach used in routine care. When possible observe the patient performing care. Compare information gathered from him or her with the proper care technique for these devices. Any difference between patient and standard practice provides an opportunity for patient education.

Assessment of Hygiene Care Practices

Assessment of hygiene practices reveals the patient’s preferences for grooming. For example, a patient chooses to groom the hair in a certain style or trim nails in a certain way. When a patient has a physical disability, special precautions may be necessary to perform grooming without injury. For example, teach patients with loss of sensation to file nails instead of clipping. By observing the patient perform hygiene care, you can detect any needed areas of teaching or assistance while maintaining the patient’s maximal level of independence.

Assessment of Cultural Influences

A patient’s cultural background influences hygiene needs. Culture plays a role not only in hygiene practices and preferences but also in sensitivity to personal space and gender sensitivity (see Box 39-1 and Chapter 9). Ask what makes the patient feel most comfortable during a bath. Perhaps he or she prefers a partial instead of a full bath from the nurse, with a family member completing the bathing of more private body parts. Some patients also defer part of hygiene. If you believe that hygiene is critical to prevent developing or worsening problems such as skin breakdown, take the time to understand the patient’s concerns and then offer an explanation that helps him or her accept your intervention.

Patients at Risk for Hygiene Problems

Some patients present risks that require more attentive and rigorous hygiene care (Table 39-5). These risks result from side effects of medications or other medical therapy; a lack of knowledge; immobilization; an inability to perform hygiene; or a physical condition that potentially injures the skin, mouth, feet and nails, or hair. Anticipate whether a patient is predisposed to risks and follow through with a complete assessment. For example, if a patient is receiving cancer chemotherapy, there is a risk of the medication producing ulcerations of the mouth, which are painful and create a risk for infection and impaired nutrition because of reluctance to eat and drink. A patient who receives broad-spectrum antibiotics develops an opportunistic infection when the normal flora of the mouth is disrupted by the antibiotic. These examples demonstrate the need to identify patients at risk and be thorough and detailed during the oral examination, checking all surfaces of the tongue and mucosa. For a patient who is diaphoretic, provide special attention to body areas such as beneath the woman’s breasts and in the groin and perineal area, where moisture collects and irritates skin surfaces. Anticipate problems created by these risks to provide preventive care. Assessment includes a review of the patient’s medical and surgical history, medications, and the specific risk factors that the patient presents.

TABLE 39-5

Risk Factors for Hygiene Problems

| RISKS | HYGIENE IMPLICATIONS |

| Oral Problems | |

| Patients who are unable to use upper extremities because of paralysis, weakness, or restriction (e.g., cast, dressing) | Patient lacks upper-extremity strength or dexterity needed to brush teeth (Lewis et al., 2011). |

| Dehydration, inability to take fluids or food by mouth (NPO) | Dehydration causes excess drying and fragility of mucosa; increases accumulation of secretions on tongue and gums. |

| Presence of nasogastric or oxygen tubes; mouth breathers | Tubes cause drying of mucosa and lips. |

| Chemotherapeutic drugs | Drugs kill rapidly multiplying cells, including normal cells lining oral cavity. Ulcers and inflammation develop. |

| Lozenges, cough drops, antacids, and chewable over-the-counter vitamins | Medications contain large amounts of sugar. Repeated use increases sugar or acid content in mouth, causing dental caries. |

| Radiation therapy to head and neck | Radiation therapy reduces salivary flow and lowers pH of saliva; leads to stomatitis and tooth decay (Lewis et al., 2011). |

| Oral surgery, trauma to mouth, placement of oral airway | These cause trauma to oral cavity with swelling, ulcerations, inflammation, and bleeding. |

| Immunosuppression; altered blood clotting | These predispose to inflammation and bleeding gums. |

| Diabetes mellitus | Patients are prone to dryness of mouth, gingivitis, periodontal disease, and loss of teeth. |

| Endotracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation | Potential for ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) exists. Use of chlorhexidine reduces risk of VAP. Chlorhexidine is an inexpensive effective agent for reducing VAP, especially in patients who have heart surgery (Berry et al., 2007). |

| Dialysis | Oral problems commonly found in these patients include halitosis, xerostomia (dry mouth), gingivitis, stomatitis, tooth decay, tooth loss, and jaw problems. Causes include decreased saliva production, uremia, and inattention to care (Gonyea, 2009). |

| Skin Problems | |

| Immobilization | Dependent body parts are exposed to pressure from underlying surfaces. The inability to turn or change position increases risk for pressure ulcers. |

| Reduced sensation caused by stroke, spinal cord injury, diabetes, local nerve damage | Patient does not receive normal transmission of nerve impulses when applying excessive heat or cold, pressure, friction, or chemical irritants to skin. |

| Limited protein or caloric intake and reduced hydration (e.g., fever, burns, gastrointestinal alterations, poorly fitting dentures) | Limited caloric and protein intake predispose to impaired tissue synthesis. Skin becomes thinner, less elastic, and smoother with a loss of subcutaneous tissue. Poor wound healing results. Reduced hydration impairs skin turgor. |

| Excessive secretions or excretions on skin from perspiration, urine, watery fecal material, and wound drainage | Moisture is a medium for bacterial growth and causes local skin irritation, softening of epidermal cells, and skin maceration. |

| Presence of external devices (e.g., cast, restraint, bandage, dressing) | Device exerts pressure or friction against surface of skin. |

| Vascular insufficiency | Arterial blood supply to tissues is inadequate, or venous return is impaired, causing decreased circulation to extremities. Tissue ischemia and breakdown often occur. Risk for infection is high. |

| Foot Problems | |

| Patient unable to bend over or has reduced visual acuity | Patient is unable to fully visualize entire surface of each foot, impairing ability to adequately assess condition of skin and nails. |

| Eye Care Problems | |

| Reduced dexterity and hand coordination | Physical limitations create inability to safely insert or remove contact lenses. |

Nursing Diagnosis

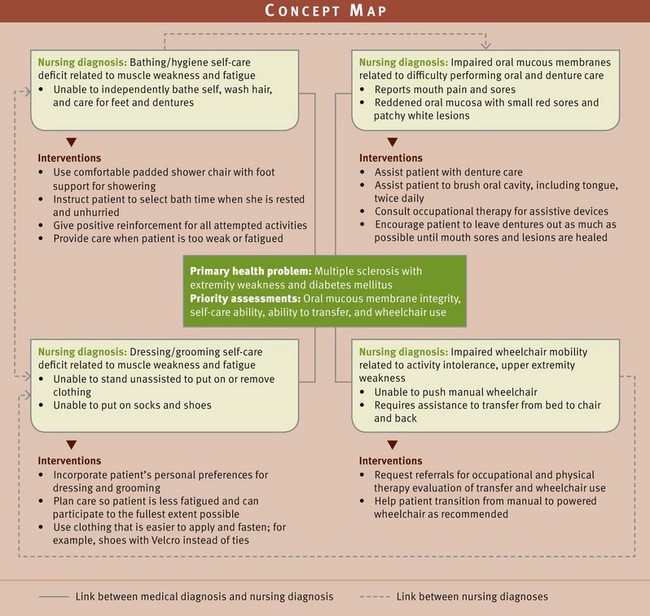

Thorough assessment of a patient’s hygiene status and self-care abilities identifies clusters of data or defining characteristics that support actual or at-risk hygiene-related diagnoses. Identification of the defining characteristics leads you to select the NANDA International diagnostic label that best communicates the individual patient’s situation. For example, when caring for an older adult with degenerative arthritis you observe swollen joints, weakness, and limited ROM in the dominant hand along with a generally unkempt appearance. Closer review of data reveals defining characteristics of an inability to wash body parts and difficulty turning and regulating a water faucet. The nursing diagnosis of bathing self-care deficit becomes part of the plan of care. Accurate selection of nursing diagnoses requires critical thinking to identify actual or potential problems. Be thorough in assessment to reveal all appropriate defining characteristics so you can make an accurate diagnosis (Box 39-4).

Use a patient’s actual alteration (e.g., impaired tissue integrity) or the alteration for which the patient is at risk (e.g., risk for infection) to determine the focus of nursing interventions. The patient with an actual alteration requires extensive hygiene care, often more thorough than routine hygiene. For example, if a patient has skin breakdown, initiate care more frequently to keep skin surfaces clean and dry and eliminate factors such as moisture or drainage that worsen skin condition. Also provide care to promote healing of injured skin surfaces (see Chapter 48). If the patient is at risk for a problem, take preventive measures. For example, if a patient is at risk for developing an infection in his or her mouth and has the nursing diagnosis risk for infection, keep the mucosa well hydrated, minimize foods irritating to tissues, and provide cleaning that soothes and reduces tissue inflammation.

Completing a nursing diagnosis requires identification of the related factor, which will guide your selection of nursing interventions. A diagnosis of impaired oral mucous membrane related to malnutrition and a diagnosis of impaired oral mucous membrane related to chemical trauma require different interventions. When poor nutrition is a causal factor, you need to consult with a dietitian for appropriate dietary supplements and incorporate patient education into the plan. When chemotherapy injures the oral mucosa, you follow cancer nursing guidelines regarding care for oral mucositis (i.e., painful inflammation of oral mucous membranes), including frequent gentle brushing with soft toothbrush, flossing, rinsing with bland rinse, limiting diet to soft foods, and applying water-based moisturizer to lips (Harris et al., 2008). Although many possible nursing diagnoses apply to patients in need of supportive hygiene care, the following list represents examples of diagnoses commonly associated with hygiene problems:

Planning

During planning synthesize information from multiple resources (Fig. 39-3). Critical thinking ensures that a patient’s plan of care integrates all that is known about the individual patient and key critical thinking elements. In many situations patients present with multiple nursing diagnoses. Use a concept map (Fig. 39-4) to visualize how nursing diagnoses interrelate. Rely on knowledge, experience, and established standards of care when developing the care plan. Remember critical thinking attitudes such as creativity when developing a patient-centered plan for hygiene care. Consciously include the patient in this important step of the nursing process. Identify patient goals and outcomes, set priorities for care, and select evidence-based interventions. Consider continuity of care and involve other health care team members (e.g., occupational or physical therapy) when developing the plan.

Previous experience with other patients is useful in knowing how to adapt hygiene techniques for special needs. Professional standards guide selection of the most effective nursing interventions. These standards often establish evidence-based guidelines for care.

Goals and Outcomes

Partner with the patient and family to identify goals and expected outcomes and develop an individualized plan of care based on the patient’s nursing diagnoses (see the Nursing Care Plan). For example, establish goals with the patient’s self-care abilities and resources in mind and focus on maintaining or improving the condition of the skin and oral cavity. Make outcomes measurable and achievable within patient limitations. In addition, work with the patient to select individualized hygiene measures.

When providing for patient hygiene, you care for a variety of patients with different self-care abilities and needs. For example, the nurse and a patient who has one-sided paralysis following a cerebral vascular accident develop the following goal: “Patient’s skin remains free of breakdown.” Then the nurse establishes a series of realistic, individualized expected outcomes to measure the patient’s progress toward meeting this goal. These outcomes may include the following:

Setting Priorities

The patient’s condition influences your priorities for hygiene care. Set priorities based on the necessary assistance required by the patient, the extent of the hygiene-related problems, and the nature of the patient’s nursing diagnoses. For example, a seriously ill patient usually needs a daily bath because body secretions accumulate and the patient is unable to independently maintain cleanliness. Some older patients at home require a visit from a home care aide to help with a tub bath or shower. Patients who are normally inactive during the day and have skin that tends to be dry may need to bathe only twice a week, whereas a patient with urinary and bowel incontinence needs perineal cleaning with each episode of soiling. Plan for necessary assistance for patients who are weakened or possess poor coordination. For example, a patient who is partially paralyzed and has difficulty getting out of a tub needs a tub chair, handrails, or extra personnel available for help.

Timing is also important in planning hygiene care. Being interrupted in the middle of a bath often frustrates and embarrasses the patient.

Teamwork and Collaboration

Plan for care throughout the stay in a hospital, including discharge to a rehabilitation facility or home. In hospital or extended care settings, work closely with nursing assistive personnel who often provide hygiene care. Provide them with the necessary information and equipment so they can provide safe, effective hygiene care. Collaborate with other health team members as indicated (e.g., work with physical therapy and occupational therapy to enhance the patient’s independence with self-care activities).

When a patient needs assistance as a result of a self-care limitation, the family often becomes a valuable resource to the nurse and helps with hygiene measures. In these cases family members often need guidance in adapting techniques to fit patient limitations. Be aware of equipment and procedures used in the agency so the patient and family are knowledgeable about the care, have the skills needed to provide it, and have access to necessary equipment. Depending on the patient’s limitations, some insurance plans provide staff to assist with basic hygiene needs. Explore this option with the patient and family members.

Collaborate with community agencies as needed. For example, the nurse involved in the care of a homeless patient needs to be aware of the location of clothing distribution centers for basic hygiene supplies, a shelter where bathing facilities are available, and any organization that offers free health care or reduced fees. Partner with social workers or staff in local area churches, not-for-profit organizations, and schools to be sure that patients have the resources they need to maintain hygiene.

Implementation

Hygiene is a part of basic patient care. Use caring practices when performing hygiene measures to reduce patient anxiety and promote comfort and relaxation. For example, while giving a patient a bath and changing a gown, use a gentle approach as you turn and reposition him or her. A soft, gentle voice while conversing with the patient helps to relieve fears or concerns. For patients suffering symptoms such as pain or nausea, administering medications to relieve the symptoms before providing hygiene interventions helps to maintain patient comfort during hygiene care. Consider the stress that hygiene care invokes and be alert for any cues of anxiety or fear. Some patients fear pain or are frightened about falling or sustaining injury associated with hygiene care.

Implementation also focuses on assisting and preparing patients to be able to perform as much of their hygiene care as they can independently. Teach patients proper hygiene techniques and signs and symptoms of hygiene problems. Inform patients about available resources in the community for dealing with these problems if they arise.

Health Promotion

In primary health care situations educate and counsel patients and caregivers on proper hygiene techniques. For example, a new mother needs to learn how to bathe her newborn, whereas an older adult needs information on the importance of regular ear care to avoid accumulated cerumen and hearing impairment. The hygiene skills described throughout this chapter provide standards for excellent physical care. When caring for patients in primary health care settings, maintain these standards and incorporate adaptations as needed to meet the patient’s lifestyle, functional status, living arrangements, and preferences. Key points when teaching patients about hygiene include the following:

• Make any instruction relevant based on your assessment of the patient’s knowledge, motivation, preferences, and health beliefs. For example, when teaching the patient with diabetes, include how circulation to the feet is impaired and how this causes poor healing and infection, especially when the skin is injured or broken.

• Adapt instruction to the patient’s personal bathing facilities and resources. Not all patients have the ideal situation that exists in a health care setting (e.g., easily accessible shower or a bedside table to place over a bed). Adapt available resources so the patient can comfortably and safely reach and use needed items. For example, a young mother has more room and believes that bathing her infant is safer if she uses her kitchen sink and counter rather than her bathroom sink.

• Teach the patient ways to avoid injury. Almost any hygiene procedure poses risks (e.g., cutting a nail too close to the skin or failing to adjust the water temperature of the bath). Include safety risks and tips with all instructions.

• Reinforce infection control practices. Damage to the skin, mucosa, eyes, or other tissues creates an immediate risk for infection. Determine that the patient understands the relationship among healthy and intact skin and tissues, hand hygiene practices, and the prevention of infection.

Acute, Restorative, and Continuing Care

Nursing knowledge and skills needed for performing hygiene care are consistent across all health care settings where acute care, restorative care, and continuing care are provided. In addition, some of the skills in this section are applicable in areas of health promotion.

The variety and timing of hygiene measures vary across health care settings and according to individual patient needs. In the acute care setting factors such as more frequent diagnostic and treatment plans and the need for more extensive hygiene care resulting from acute illness or injury affect scheduling. In extended care facilities and nursing homes, bathing may be scheduled less frequently.

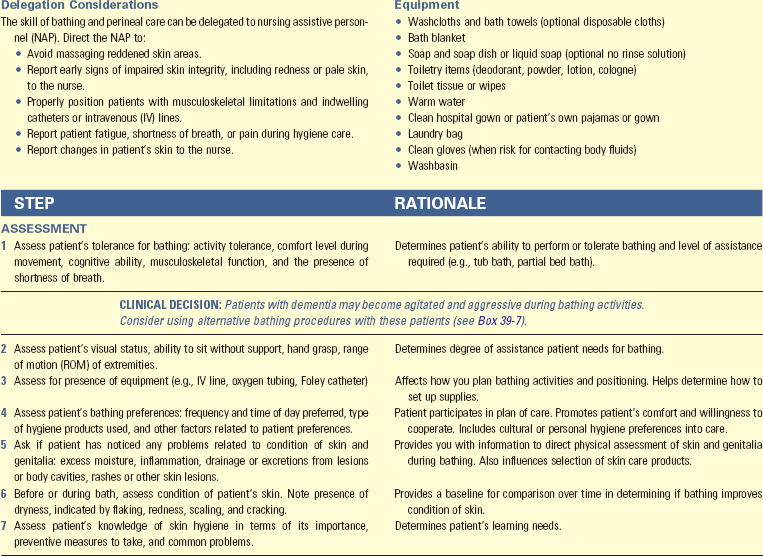

Bathing and Skin Care

Consider a patient’s normal grooming routines, including type of hygiene products used and the time of day when hygiene is routinely performed. Individualize your care based on the patient’s preferences. The extent, type, and timing or frequency of bathing and the methods used depend on a patient’s physical abilities, health problems, and the degree of hygiene required (Boxes 39-5 and 39-6). In addition to cleansing baths, the health care provider may prescribe therapeutic baths, including sitz baths or medicated baths (e.g., oatmeal, cornstarch, or Aveeno). A sitz bath cleans and reduces pain and inflammation of perineal and anal areas. Medicated baths relieve skin irritation and create an antibacterial and drying effect.

If a patient is physically dependent or cognitively impaired, increase the frequency of skin assessment and provide skin care directed toward reducing the risk for skin breakdown. When bathing patients with cognitive impairments, consider special needs and challenges (Box 39-7). These patients easily become afraid and use physical and verbal aggressive behaviors to express their needs. Apply available evidence to your care of the patient who is cognitively impaired. When family members assist in bathing cognitively impaired patients, you need to provide them with coaching, practice, and support (Mahoney et al., 2006).

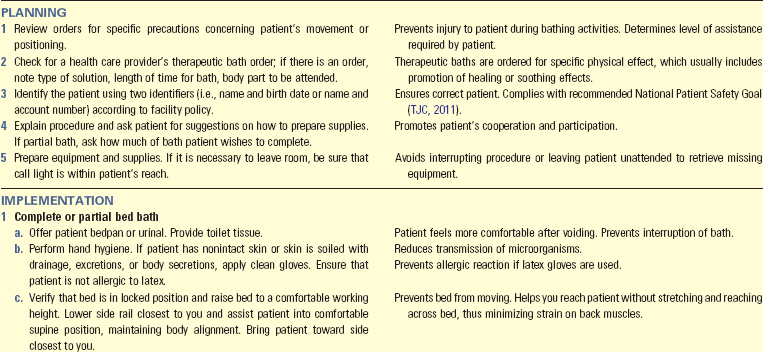

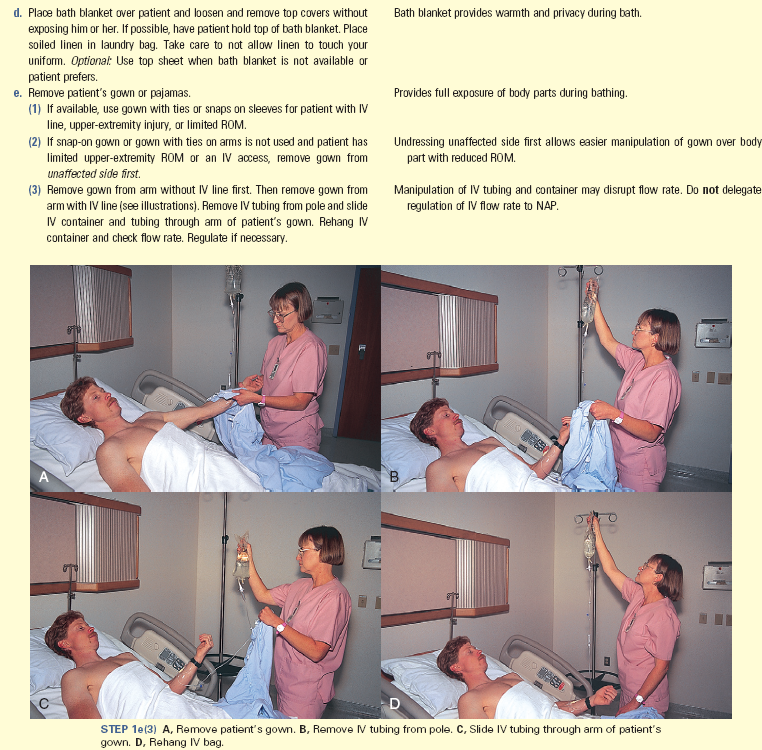

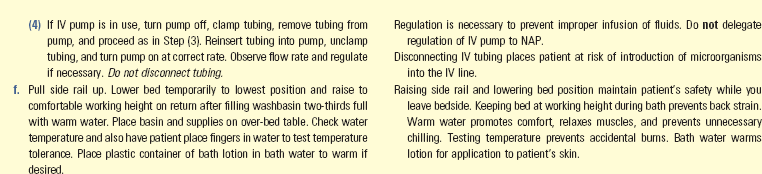

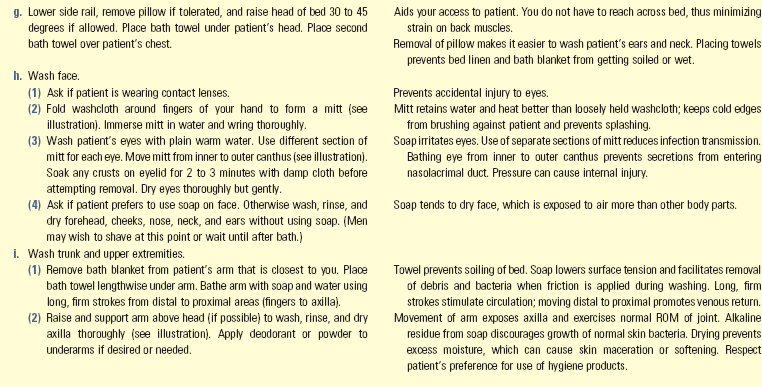

A complete bed bath (Skill 39-1 on pp. 797-805) often exhausts a patient. Turning during a complete bed bath and receiving back care increase oxygen consumption and demand. Anticipate and assess whether patients are physically able to tolerate a complete bath. Assessing heart rate before, during, and after the bath provides a measure of their physical tolerance. Provide a partial bed bath (see Skill 39-1) to patients who are aging, dependent, in need of only partial hygiene, or bedridden and unable to reach all body parts. Wear gloves when there is a risk of contacting body fluids. Control environmental factors that alter skin integrity, including moisture, heat, and external sources of pressure such as wrinkled bed linen and improperly placed drainage tubing.

When administering either a complete or partial bath, assess the condition of the skin to determine if soap is necessary or if the patient requires daily bathing. Patients with excessively dry skin are predisposed to skin impairment. Use soaps that contain emollients to hydrate dry skin. Avoid overly hot water because it can dry the skin by removing natural oils. Lubricate the skin with emollient lotions to reduce dryness.

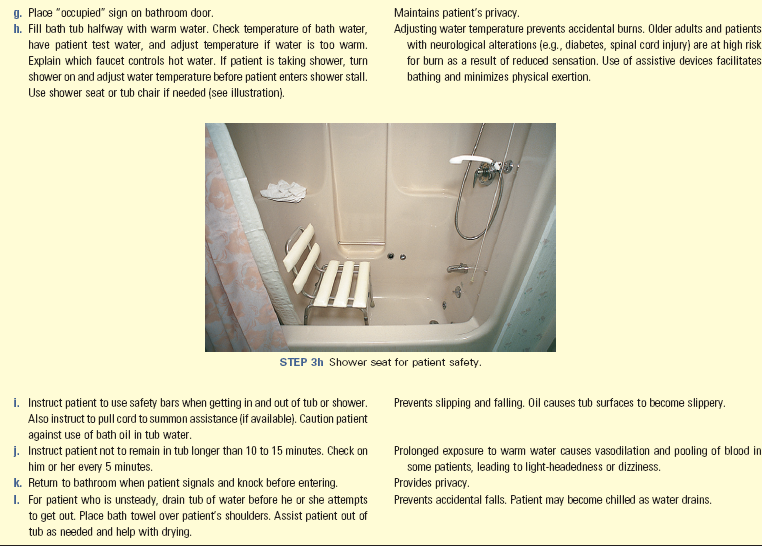

Use the tub bath or shower (see Skill 39-1) to give a more thorough bath than a bed bath. Implement safety measures to prevent fall injuries because the surface of the tub or shower stall is slippery. In some settings a health care provider’s order for a shower or tub bath is necessary. Place a chair in the shower for patients with weakness or poor balance. Both tubs and showers need to have grab bars for patients to hold during entry and exit and maneuvering during the bath or shower. Patients vary in how much help they need.

Regardless of the type of bath the patient receives, use the following guidelines:

• Provide privacy. Close the door and/or pull room curtains around the bathing area. While bathing the patient, expose only the areas being bathed by using proper draping.

• Maintain safety. Keep side rails up when away from the patient’s bedside when patients are dependent or unconscious. Note: When side rails serve as a restraint, you need a health care provider’s order (see agency-specific policy for restraint usage) (see Chapter 27). Place the call light in the patient’s reach if leaving the bedside even temporarily.

• Maintain warmth. Keep the room warm because the patient is partially uncovered and easily chilled. Wet skin causes an excess loss of heat through evaporation. Control drafts and keep windows closed. Keep patient covered, only exposing the body part being washed during the bath.

• Promote independence. Encourage the patient to participate in as much of the bathing activities as possible. Offer assistance when needed.

• Anticipate needs. Bring a new set of clothing and hygiene products to the bedside or bathroom.

Teach patients to follow a few general rules for skin health. Encourage them to routinely inspect their skin for changes in color or texture and report abnormalities to their health care provider. Instruct patients to handle the skin gently, avoiding excessive rubbing. Also encourage them to eat nutritious foods from all food groups, including those rich in vitamins and minerals, and to consume adequate fluids. Stress safety concerns such as failing to adjust or check the water temperature, cutting nails too close to the skin, and slipping on wet surfaces. Ensure that patients understand that healthy and intact skin and tissues protect them from infection. Reinforce infection control practice, including proper hand hygiene.

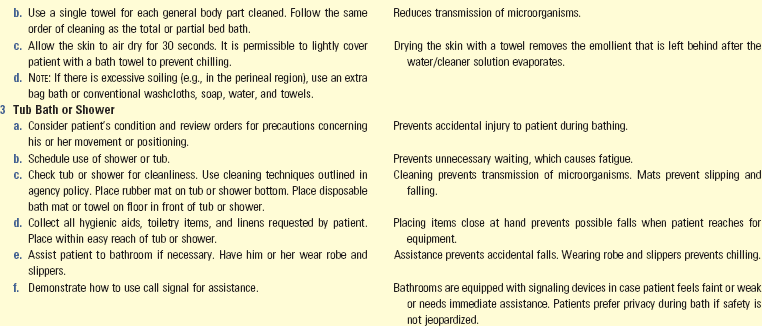

Bag Baths: This innovative approach to the traditional bed bath was developed because of nurses’ concern for patients who are predisposed to dry skin and the risk for infection (see Skill 39-1). Not cleaning and drying washbasins completely after use provides a risk for contamination by disease-producing gram-negative organisms. Based on their study in intensive care units, Johnson, Lineweaver, and Maze (2009) concluded that bath basins provide a reservoir for bacteria and are a possible source of transmission of hospital-acquired infections. The bag bath contains a no-rinse surfactant, a humectant to trap moisture, and an emollient. Nurses in another study expressed a significant overall preference for the disposable bag bath versus the traditional basin bath, especially for patients who are unable to bathe themselves in critical and long-term care settings (Larson et al., 2004). Some facilities have switched from the traditional bath in favor of the bag bath because of concerns related to infection control.

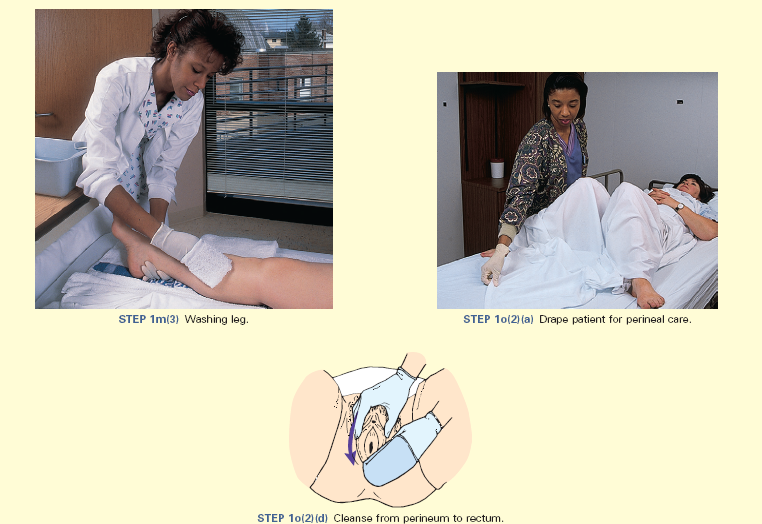

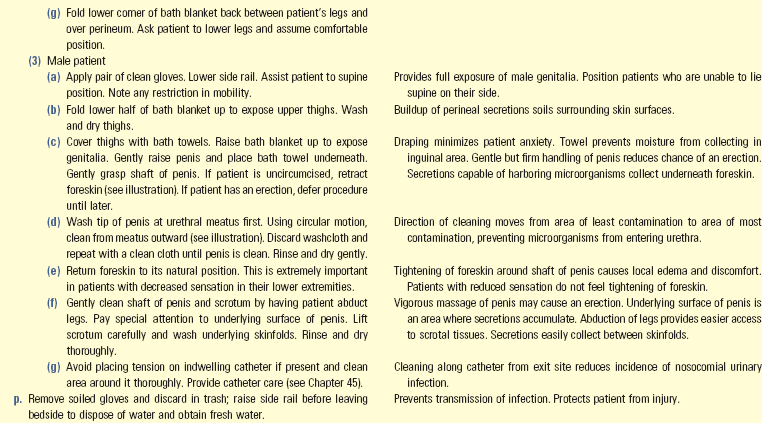

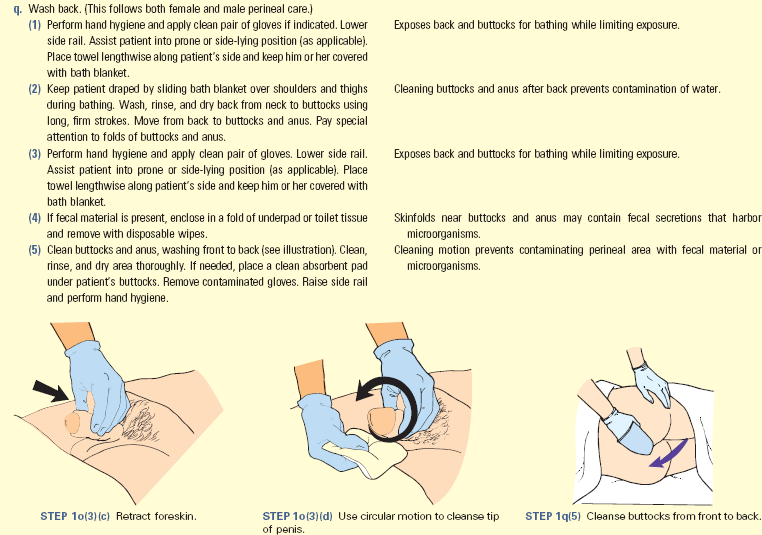

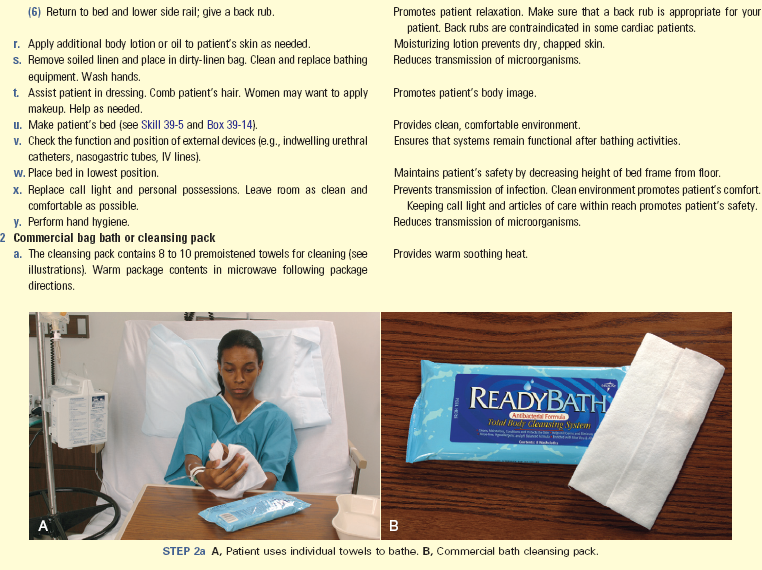

Perineal Care: Cleansing patients’ genital and anal areas is called perineal care. It usually occurs as part of a complete bed bath (see Skill 39-1). Patients most in need of perineal care include those at greatest risk for acquiring an infection (e.g., uncircumcised males, patients who have indwelling urinary catheters, or those who are recovering from rectal or genital surgery or childbirth). In addition, women who are having a menstrual period require perineal care. Encourage patients to perform their own perineal care. Sometimes you are embarrassed about providing perineal care, particularly to patients of the opposite sex. Similarly the patient may feel embarrassed. Do not let embarrassment cause you to overlook the patient’s hygiene needs. When staffing levels permit, use a gender-congruent caregiver. A professional, dignified, and sensitive approach reduces embarrassment and helps put the patient at ease.

If a patient performs self-care, various problems such as vaginal and urethral discharge, skin irritation, and unpleasant odors often go unnoticed. Stress the importance of perineal care in preventing skin breakdown and infection. Be alert for complaints of burning during urination or localized soreness, excoriation, or pain in the perineum. Inspect vaginal and perineal areas and the patient’s bed linen for signs of discharge and use your sense of smell to detect abnormal odors. Risk factors for skin breakdown in the perineal area include urinary or fecal incontinence, rectal and perineal surgical dressings, indwelling urinary catheters, and morbid obesity.

Back Rub

A back rub or back massage usually follows the patient’s bath. It promotes relaxation, relieves muscular tension, and decreases perception of pain. Effleurage (i.e., long, slow, gliding strokes of a massage) is associated with reduced measured anxiety, heart rate, and respiratory rate. Studies show that slow-stroke back massages of 3 minutes and hand massages of 10 minutes significantly improve both physiological and psychological indicators of relaxation in older people (Harris and Richards, 2010).

When providing a back rub, enhance relaxation by reducing noise and ensuring that the patient is comfortable. It is important to ask whether a patient would like a back rub or if he or she prefers gentle instead of deep massage, because some individuals dislike physical contact. Consult the medical record for any contraindications to a massage (e.g., fractured ribs, burns, and heart surgery).

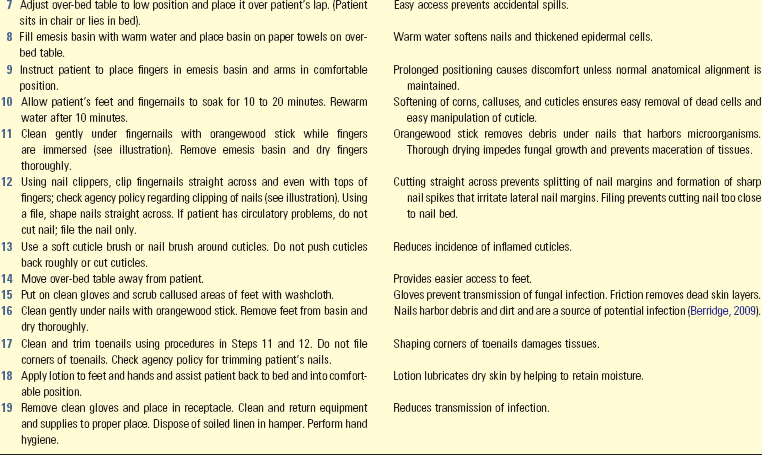

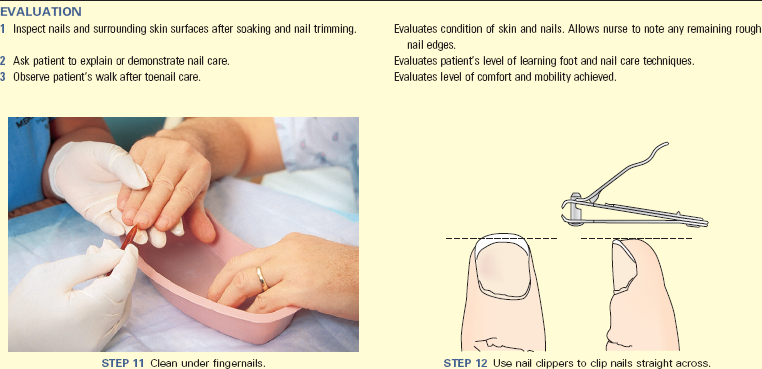

Foot and Nail Care

Incorporate foot and nail care into a person’s regular hygiene routine. Routine care involves soaking to soften cuticles and layers of horny cells, thorough cleaning, drying, and proper nail trimming. Patients with diabetes mellitus should not soak their nails because of the risk of overdrying the feet and developing breaks in the skin with resulting infection. When providing nail care, the patient remains in bed or sits in a chair (Skill 39-2 on pp. 805-808). In some settings or with specific patients such as a person with diabetes mellitus, you need a health care provider’s order to trim toenails. Before implementing this procedure, check agency policy to determine if the order is necessary.

Take time during the procedure to teach the patient and family proper techniques for cleaning and nail trimming. You need to stress measures to prevent infection and promote good circulation. Patients learn to protect the feet from injury, keep them clean and dry, and wear footwear that fits properly. Instruct patients in the proper way to inspect all surfaces of the feet and hands for redness, lesions, dryness, or signs of infection. Teach foot care to family members or caregivers for patients who need regular foot care and have peripheral vascular disease, visual difficulties, physical constraints preventing movement, or cognitive problems.

Certain conditions place patients with diabetes at increased risk for amputation (American Diabetes Association, 2007). These factors include peripheral neuropathy, limited joint mobility, bony deformity, peripheral vascular disease, and a history of skin ulcers or previous amputation. Observe for changes that indicate peripheral neuropathy or vascular insufficiency (Box 39-8). Advise patients to use the following guidelines in a routine foot and nail care program (American Diabetes Association, 2010):

• Receive a thorough foot examination at least once a year. People with one or more high-risk foot conditions need an evaluation more frequently.

• Inspect the feet daily, including the bottoms and tops, heels, and areas between the toes. Use a mirror to help inspect the feet thoroughly or ask a family member to check daily.

• Wash feet daily in lukewarm water. Dry thoroughly, especially between the toes.

• Wear shoes and clean, dry socks at all times; never go barefoot. Check inside shoes before wearing them for rough areas or objects that may rub against the foot.

• Keep skin soft and smooth by applying an emollient lotion over all surfaces of the feet but not between the toes.

• If you can see and reach your toenails, trim them straight across and square file the edges smooth.

• Keep the blood flowing to your feet by putting them up when sitting and wiggling your toes and moving your ankles up and down for 5 minutes 2 or 3 times a day. Do not cross your legs for long periods and don’t smoke.

• Protect the feet from hot and cold. Do not use heating pads or electric blankets and always wear shoes at the beach or on hot pavement.

Oral Hygiene

Regular oral hygiene, including brushing, flossing, and rinsing, prevents and controls plaque-associated oral diseases. Evidence relates poor oral health to risk of impaired nutrition, stroke, poor blood sugar control in diabetes, and nursing home–acquired pneumonia (Jablonski, 2009). Inadequate oral care and some medications diminish salivary production, which in turn reduces the ability of the oral environment to help fight effects of pathogens (Box 39-9).

Brushing cleans the teeth of food particles, plaque, and bacteria. It also massages the gums and relieves discomfort resulting from unpleasant odors and tastes. Flossing removes tartar that collects at the gum line. Rinsing removes dislodged food particles and excess toothpaste. Complete oral hygiene enhances well-being and comfort and stimulates the appetite.

When patients become ill, many factors influence their need for oral hygiene. Patients in hospitals or long-term care facilities do not always receive the aggressive oral care they need. Base the frequency of care on the condition of the oral cavity and the patient’s level of comfort. Some patients require oral care as often as every 1 to 2 hours.

Acidic fruits in the patient’s diet reduce plaque formation. A well-balanced diet contributes to the integrity of oral tissues. To prevent tooth decay, patients sometimes need to change eating habits (e.g., reducing intake of carbohydrates, especially sweet snacks between meals). Advise patients of all ages to visit a dentist regularly for checkups. Education about common gum and tooth disorders and methods of prevention may motivate patients to follow good oral hygiene practices.

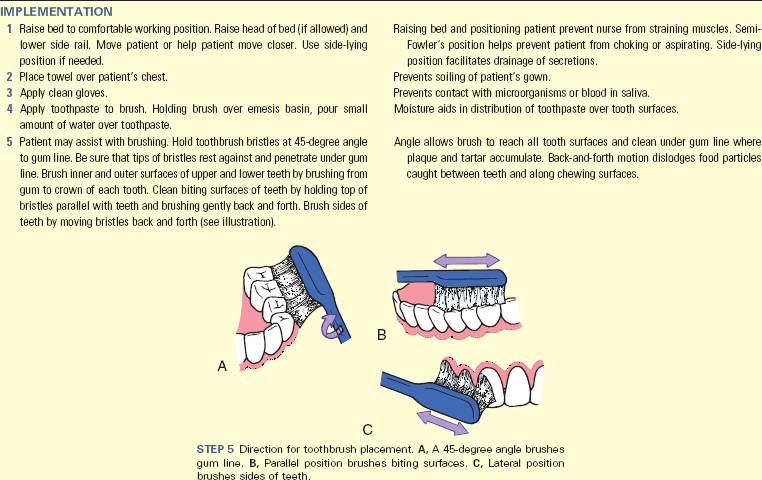

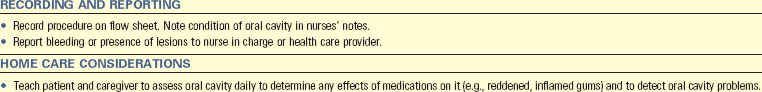

Brushing: The American Dental Association (2010) guidelines for effective oral hygiene include brushing the teeth at least twice a day with American Dental Association–approved fluoride toothpaste. Fluoride and antimicrobial mouth rinses also help prevent tooth decay. Do not use fluoride rinse in children ages 6 or under because of the risk of swallowing the rinse. Use antimicrobial toothpastes and 0.12% chlorhexidine oral rinses for patients at increased risk for poor oral hygiene (e.g., older adults and patients with cognitive impairments and who are immunocompromised) (Garcia and Caple, 2011). The toothbrush needs to have a straight handle and a brush small enough to reach all areas of the mouth. Rounded soft bristles stimulate the gums without causing abrasion and bleeding. Any patient who experiences decreased dexterity as a result of a medical condition or the aging process requires an enlarged handle with an easier grip.

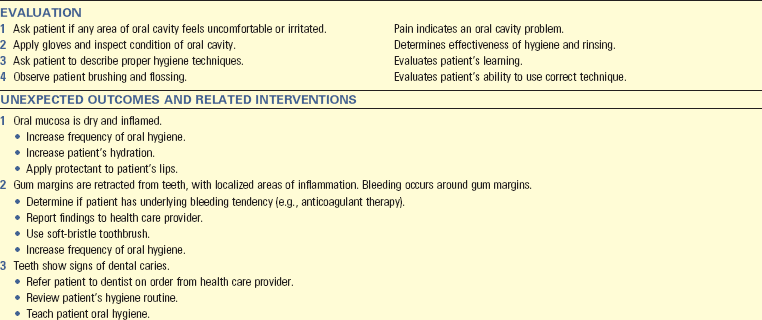

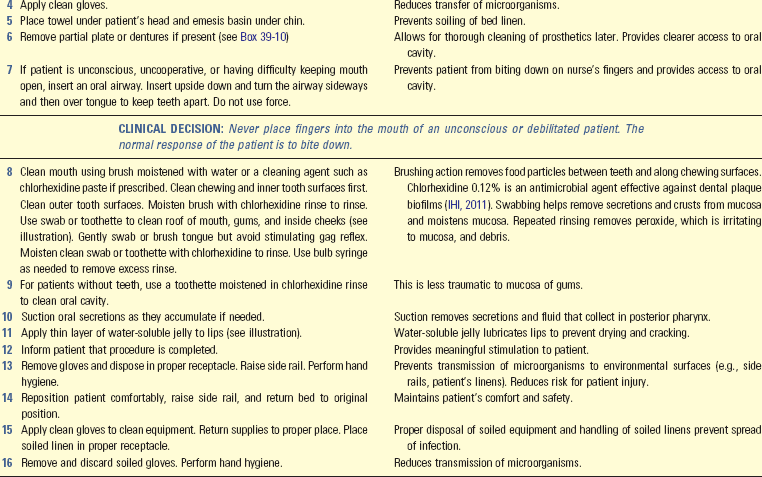

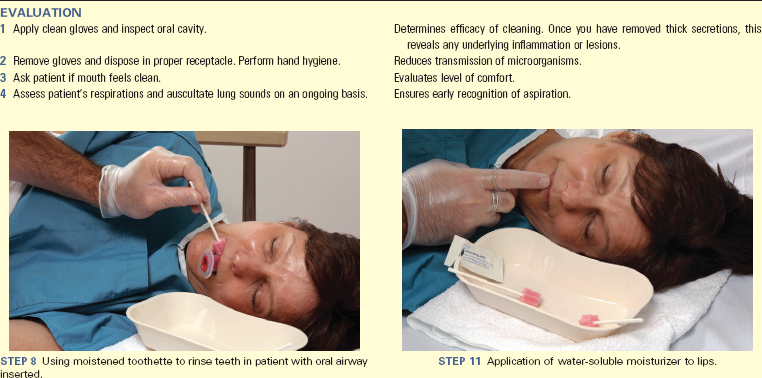

Brush all tooth surfaces thoroughly (Skill 39-3 on pp. 808-811). Commercially made foam swabs are ineffective in removing plaque (Garcia and Caple, 2011). Electric or powered toothbrushes improve the quality of cleaning and may be easier to use than manual brushes when nurses provide care for dependent patients. Do not use lemon-glycerin sponges because they dry mucous membranes and erode tooth enamel.