Patient Safety

• Discuss the importance of consensus standards for public reporting of patient safety events.

• Describe environmental hazards that pose risks to a person’s safety.

• Discuss methods to reduce physical hazards and the transmission of pathogens.

• Discuss the specific risks to safety related to developmental age.

• Identify the factors to assess when a patient is in restraints.

• Describe the four categories of safety risks in a health care agency.

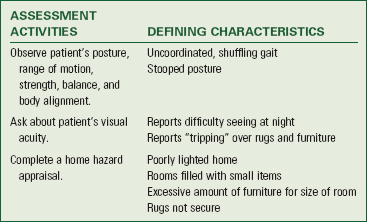

• Describe assessment activities designed to identify patients’ physical, psychosocial, and cognitive status as it pertains to their safety.

• Identify relevant nursing diagnoses associated with risks to safety.

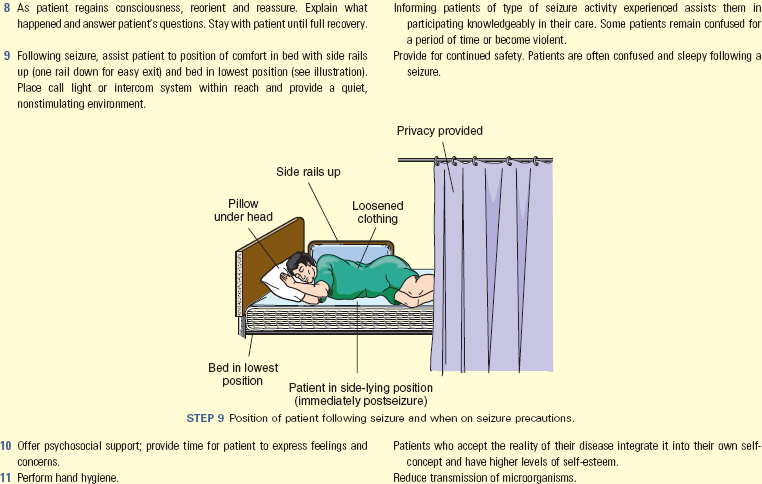

• Develop a nursing care plan for patients whose safety is threatened.

• Describe nursing interventions specific to a patients’ age for reducing risk of falls, fires, poisonings, and electrical hazards.

• Define the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to promote safety in a health care setting.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Safety, often defined as freedom from psychological and physical injury, is a basic human need. Health care provided in a safe manner and a safe community environment is essential for a patient’s survival and well-being. A safe environment reduces the risk for illness and injury and helps to contain the cost of health care by preventing extended lengths of treatment and/or hospitalization, improving or maintaining a patient’s functional status, and increasing the patient’s sense of well-being. The Institute of Medicine’s report To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (2000) was a pivotal publication that brought patient safety to the forefront of health care in the United States. This report indicated that 44,000 to 98,000 people die each year as a result of preventable medical errors. In an effort to improve patient safety, many organizations have become devoted to developing and monitoring key health care safety initiatives and providing information to health care organizations and the public. Health care organizations foster a patient-centered safety culture by continually focusing on performance improvement endeavors, risk management findings, and safety reports; providing current reliable technology; integrating evidence-based practice into procedures; designing a safe work environment and atmosphere; and providing continuing education and access to appropriate resources for staff (Box 27-1). As part of the health care team, the nurse has the professional responsibility to be engaged in activities that support a patient-centered safety culture. Considerable emphasis has also been placed on improving the education of student nurses so they become more competent in promoting safe health care practices. The Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) project was developed to meet the challenge of preparing future nurses who will have the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to continuously improve the quality and safety of the health care systems within which they work (QSEN, 2011). The QSEN safety competency for a nurse is defined as “Minimizes risk of harm to patients and providers through both system effectiveness and individual performance.” As a nurse you are responsible for incorporating critical thinking skills when using the nursing process, assessing each patient and his or her environment for hazards that threaten safety, and planning and intervening appropriately to maintain a safe environment. By doing this, you become a provider of safe acute, restorative, and continuing care and an active participant in health promotion.

Scientific Knowledge Base

A patient’s environment includes all of the many physical and psychosocial factors that influence or affect the life and survival of that patient. This broad definition of environment crosses the continuum of care for settings in which the nurse and patient interact such as the hospital, long-term care facility, clinic, community center, school, and home. A safe environment protects the staff as well, allowing them to function optimally. Vulnerable groups who often require help in achieving a safe environment include infants, children, older adults, the ill, the physically and mentally disabled, the illiterate, and the poor. A safe environment includes meeting basic needs, reducing physical hazards and the transmission of pathogens, and controlling pollution.

Basic Needs

Physiological needs, including the need for sufficient oxygen, nutrition, and optimum temperature, influence a person’s safety. According to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, these basic needs must be met before physical and psychological safety and security can be addressed (see Chapter 6).

Oxygen: Supplemental oxygen is sometimes required to meet a person’s oxygenation needs. Oxygen is not flammable, but fire needs oxygen to start and to keep burning. When more oxygen is in the air, a fire burns hotter and faster. Strict codes regulate the use and storage of medical oxygen in health care facilities. This is not necessarily true in the home environment. Hospital emergency departments see approximately 1190 thermal burns per year caused by ignitions associated with home medical oxygen (National Fire Protection Association, 2008). Smoking is by far the leading cause of burns, reported fires, deaths, and injuries involving home medical oxygen.

Be aware of factors in a patient’s environment that decrease the amount of available oxygen. A common environmental hazard in the home is an improperly functioning heating system. A furnace, stove, or fireplace that is not properly vented introduces carbon monoxide into the environment. Carbon monoxide affects a person’s oxygenation by binding with hemoglobin, preventing the formation of oxyhemoglobin and thus reducing the supply of oxygen delivered to tissues (see Chapter 40). Low concentrations cause nausea, dizziness, headache, and fatigue. Very high concentrations cause death after 1 to 3 minutes of exposure (National Fire Protection Association, 2010a).

Nutrition: Meeting nutritional needs adequately and safely requires environmental controls and knowledge (see Chapter 44). Health care facilities and restaurants are required to meet State Board of Health regulations. To protect consumers, commercially processed and packaged foods are subject to Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations. The FDA is a federal agency responsible for the enforcement of federal regulations regarding the manufacture, processing, and distribution of foods, drugs, and cosmetics to protect consumers against the sale of impure or dangerous substances. Although food supply in the United States is one of the safest in the world, each year about 76 million illnesses occur, more than 300,000 persons are hospitalized, and 5,000 die from foodborne illness (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009). Groups at the highest risk are children, pregnant women, older adults, and people with compromised immune systems. Foods that are inadequately prepared or stored or subject to unsanitary conditions increase the patient’s risk for infections and food poisoning.

Temperature: A person’s comfort zone is usually between 18.3° and 23.9° C (65° and 75° F). Temperature extremes that frequently occur during the winter and summer affect comfort, productivity, and safety. Exposure to severe cold for prolonged periods causes frostbite and accidental hypothermia. Frostbite occurs when a surface area of the skin freezes as a result of exposure to extremely cold temperatures. Hypothermia occurs when the core body temperature is 35° C (95° F) or below. Older adults, the young, patients with cardiovascular conditions, patients who have ingested drugs or alcohol in excess, and people who are homeless are at high risk for hypothermia. Exposure to extreme heat changes the electrolyte balance of the body and raises the core body temperature, resulting in heatstroke or heat exhaustion. Chronically ill patients, older adults, and infants are at greatest risk for injury from extreme heat. These patients need to avoid extremely hot, humid environments (see Chapter 29).

Physical Hazards

On average 33.5 million injuries take place each year, with the majority occurring inside or outside of the home (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010a). Physical hazards in the environment threaten a person’s safety and often result in physical or psychological injury or death. Unintentional injuries are the fifth leading cause of death for Americans of all ages (National Center for Injury Prevention, 2010a). Motor vehicle accidents are the leading cause, followed by poisonings and falls. Additional hazards consist of fire and disasters. A nurse plays a role in educating patients about common safety hazards and how to prevent injury while placing emphasis on hazards to which patients are more vulnerable.

Motor Vehicle Accidents: Vehicle design and equipment such as seat belts, air bags, and laminated windshields (remain in one piece when impacted) have improved safety for vehicle occupants. State specific laws relating to young driver licensing, safety belt use, child restraint use, and motorcycle helmets exist for protection. Child safety seats and booster seats appropriate for the child’s age and weight and the type of car need to be used (Fig. 27-1). The American Academy of Pediatrics (2011) recommends that all infants and toddlers ride in the back seat with a rear-facing car safety seat until they are 2 years of age or they reach the highest weight or height allowed by the manufacturer of the car safety seat. The website of the Academy, Healthy Children, http://www.aap.org/healthtopics/carseatsafety.cfm, has information for children of all ages and the type of safety seat to use. The back seat of a car is the safest part of the vehicle in the event of a crash and prevents injury from deployment of passenger and side air bags. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010b), the risk of motor vehicle accidents is higher among 16- to 19-year-old drivers than any other age-group. Teens are more likely to underestimate dangerous situations or not be able to recognize hazardous situations, speed and allow shorter headways, ride with intoxicated drivers, and drive after using alcohol and drugs. Teens also have the lowest rate of seat belt use. Older drivers are keeping their licenses longer and driving more miles than in the past. Per mile traveled, fatal crash rates increase starting at age 75 and increase markedly after age 80 (Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 2008). An older adult is not always able to quickly observe situations in which an accident is likely to occur. Decreased hearing acuity alters the ability to hear emergency vehicle sirens or vehicle horns. Because of decreased nervous system response, older adults are unable to react as quickly as they once could to avoid an accident. A decline in these skills accounts for the most common types of accidents, including right-of-way and turning accidents.

Poison: A poison is any substance that impairs health or destroys life when ingested, inhaled, or absorbed by the body. Almost any substance is poisonous if too much is taken. Sources in a person’s home include drugs, medicines, other solid and liquid substances, and gases and vapors. Poisons often impair the function of every major organ system. Health care providers are at risk from chemicals such as toxic cleaning agents. In the home accidental poisoning is a greater risk for toddlers, preschoolers, and young school-age children, who often ingest household cleaning solutions, medications, or personal hygiene products. Emergency treatment is necessary when a person ingests a poisonous substance or comes in contact with a chemical that is absorbed through the skin. In 2008 more than 2000 people a day were seen in emergency departments after a poison incident (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010c). Specific antidotes or treatments are available only for some types of poisons. A poison control center is the best resource for patients and parents needing information about the treatment of an accidental poisoning.

Although lead has not been used in house paint or plumbing materials since the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission banned it in 1978, older homes in poorer communities continue to contain high lead levels. Soil and water systems are sometimes contaminated. Poisoning occurs from swallowing or inhaling lead. Fetuses, infants, and children are more vulnerable to lead poisoning than adults because their bodies absorb lead more easily and small children are more sensitive to the damaging effects of lead. Exposure to excessive levels of lead affects a child’s growth or causes learning and behavioral problems and brain and kidney damage (Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, 2010).

Falls: Falls are a major public health problem. Among adults 64 years and older, falls are the leading cause of unintentional death (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010a). Numerous factors increase the risk of falls, including a history of falling, being age 65 or over, reduced vision, orthostatic hypotension, gait and balance problems, urinary incontinence, use of walking aids, and the effects of various medications (e.g., anticonvulsants, hypnotics, sedatives, certain analgesics) (Deandrea et al., 2010). Common physical hazards that lead to falls include inadequate lighting, barriers along normal walking paths and stairways, and a lack of safety devices in the home. Often a fall leads to serious injury such as fractures or internal bleeding. Patients most at risk for injury are those with bleeding tendencies resulting from disease or medical treatments and osteoporosis. Injuries frequently result from accidental contact with objects on stairs, floors, bedside tables, closet shelves, refrigerator tops, and bookshelves. Children fall from anywhere (i.e., trees, wall/fences, playground equipment, furniture, and moving objects such as skateboards and bicycles). Forces from falls lead to injury with variable severity, depending on the height of the fall, body position on impact, and impact surface.

Fire: A total of 386,500 home fires were reported in the United States in 2008, resulting in 2,755 deaths and 13,160 injuries (National Fire Protection Association, 2010b). The leading cause of fire-related death is careless smoking, especially when people smoke in bed at home. The improper use of cooking equipment and appliances, particularly stoves, is the main source for in-home fires and fire injuries. Smoke detectors and carbon monoxide detectors need to be placed strategically throughout a home. Multipurpose fire extinguishers need to be near the kitchen and any workshop areas.

Disasters: When they strike, natural disasters such as floods, tsunamis, hurricanes, tornadoes, and wildfires are a major cause of death and injury. These types of disasters result in death and leave many people homeless. Every year millions of Americans face disaster and its terrifying consequences (FEMA, 2010). Bioterrorism is another cause of disaster. Threats of this type come in the form of biological, chemical, and radiological attacks. Bioterrorism, or the use of biological agents to create fear and threat, is the most likely form of a terrorist attack to occur. Although terrorists could use any agent, health officials are most concerned with biological agents such as anthrax, smallpox, pneumonic plague, botulism, tularemia, and viral hemorrhagic fevers (American Medical Association, 2010).

Transmission of Pathogens

Pathogens and parasites pose a threat to patient safety (see Chapter 28). A pathogen is any microorganism capable of producing an illness. The most common means of transmission of pathogens is by the hands. For example, if an individual infected with hepatitis A does not wash his or her hands thoroughly after having a bowel movement, the risk for transmitting the disease during food preparation is great. One of the most effective methods for limiting the transmission of pathogens is the medically aseptic practice of hand hygiene (see Chapter 28). The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the pathogen that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and the hepatitis B virus are transmitted through blood and other select body fluids. High-risk behaviors that include sexual contact and drug use are common risk factors for HIV. People who abuse drugs often share syringes and needles, which increase the risk of acquiring these viruses. Some states and many nonprofit organizations fund syringe exchange programs as a means to slow down the spread of infectious diseases obtained through needle sharing (Coalition for Safe Community Needle Disposal, 2010).

Immunization also reduces, and in some cases prevents, the transmission of disease from person to person. Individuals acquire active immunity by an injection of a small amount of attenuated (weakened) or dead organisms or modified toxins from the organism (toxoids) into the body. Passive immunity occurs when antibodies produced by other persons or animals are introduced into a person’s bloodstream for protection against a pathogen.

Insects and rodents often carry pathogens. For example, some mosquitoes are carriers of malaria and West Nile virus. Rats and mice carry rat-bite fever. Uncontrolled mosquito and rodent populations increase the risk for these diseases. People living at the poverty level sometimes live in unmaintained homes or housing. Rat and roach infestations are common problems. Mosquito repellant and rodent traps help eliminate this risk.

Proper disposal of human waste controls the transmission of disease and parasites. Without a satisfactory sewer and waste system in a community, the population is at risk for illnesses such as typhoid fever and hepatitis.

Pollution

A healthy environment is free of pollution. A pollutant is a harmful chemical or waste material discharged into the water, soil, or air. People commonly think of pollution only in terms of air, land, or water pollution; but excessive noise is also a form of pollution that presents health risks. Air pollution is the contamination of the atmosphere with a harmful chemical. Prolonged exposure to it increases the risk of pulmonary disease. In urban areas industrial waste and vehicle exhaust are common contributors to air pollution. In the home, school, or workplace, cigarette smoke is the primary cause of air pollution. Improper disposal of radioactive and bioactive waste products (e.g., dioxin) can cause land pollution. Water pollution is the contamination of lakes, rivers, and streams, usually by industrial pollutants. Water treatment facilities filter harmful contaminants from the water, but these systems sometimes contain flaws. If water becomes contaminated, the public needs to use bottled or boiled water for drinking and cooking. Flooding frequently causes damage to water treatment stations and also requires the use of bottled or boiled water.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Factors Influencing Patient Safety

In addition to being knowledgeable about the home and health care environment and the inherent safety risks, nurses need to be familiar with a patient’s developmental level; mobility, sensory, and cognitive status; lifestyle choices; and knowledge of common safety precautions. They also need to be aware of the special risks to safety that are found in health care settings.

Risks at Developmental Stages

A patient’s developmental stage creates threats to safety as a result of lifestyle, cognitive and mobility status, sensory impairments, and safety awareness. With this information, you tailor safety prevention programs to the needs, preferences, and life circumstances of particular age-groups. Unfortunately all age-groups are subject to abuse. Child abuse, domestic violence, and elder abuse are serious threats to safety. Chapters 12 through 14 discuss these topics.

Infant, Toddler, and Preschooler: Injuries are the leading cause of death in children over age 1 and cause more death and disabilities than do all diseases combined (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). The nature of the injury sustained is closely related to normal growth and development. For example, the incidence of lead poisoning is highest in late infancy and toddlerhood. Children at this stage explore the environment and, because of their increased level of oral activity, put objects in their mouth. This increases risk for poisoning and choking. Fire often results from their curiosity in playing with matches. In addition, limited physical coordination contributes to falls from bicycles and playground equipment. Additional injuries at this age are related to riding unrestrained in a motor vehicle, drowning, and head trauma from objects. Accidents involving children are largely preventable, but parents need to be aware of specific dangers at each stage of growth and development. Accident prevention thus requires health education for parents and the removal of dangers whenever possible.

School-Age Child: When a child enters school, the environment expands to include the school, transportation to and from school, school friends, and after-school activities. School-age children are learning how to perform more complicated motor activities and often are uncoordinated. Parents, teachers, and nurses need to instruct children in safe practices to follow at school or play, including what to do if approached by strangers. Teach school-age children involved in team and contact sports the rules for playing safely and how to use protective safety equipment such as helmets and other protective gear. Head injuries are a major cause of death, with bicycle accidents being one of the major causes of such injuries (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). Bikes need to be the proper size for the child, and helmets must be worn (Fig. 27-2). Additional injuries in this age-group are decreased by properly using seat belts and booster seats in motor vehicles and providing pedestrian safety education.

Adolescent: As children enter adolescence, they develop greater independence and begin to develop a sense of identity and their own values. The adolescent begins to separate emotionally from his or her family, and peers generally have a stronger influence. Wide variations that swing from childlike to mature behavior are characteristic of adolescent behavior (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2009). In an attempt to relieve the tensions associated with physical and psychosocial changes and peer pressures, some adolescents engage in risk-taking behaviors such as smoking, drinking alcohol, and using drugs. This increases the incidence of accidents such as drowning and motor vehicle accidents. When adolescents learn to drive, their environment expands, and so does their potential for injury. Fortunately teen motor vehicle crashes are preventable by avoiding distractions such as using cell phones, texting, eating, and drinking while driving.

To assess for possible substance abuse, have parents look for environmental and psychosocial clues from their children. Environmental clues include the presence of drug-oriented magazines, beer and liquor bottles, drug paraphernalia and blood spots on clothing and the continual wearing of long-sleeved shirts in hot weather and dark glasses indoors. Psychosocial clues include failing grades, change in dress, increased absenteeism from school, isolation, increased aggressiveness, and changes in interpersonal relationships. Because adolescence is a time when mature sexual physical characteristics develop, some adolescents begin to have physical relationships with others that present the risk of sexually transmitted diseases.

Adult: The threats to an adult’s safety are frequently related to lifestyle habits. For example, a person who uses alcohol excessively is at greater risk for motor vehicle accidents. People who smoke long-term have a greater risk of cardiovascular or pulmonary disease as a result of the inhalation of smoke and the effect of nicotine on the circulatory system. Likewise, the adult experiencing a high level of stress is more likely to have an accident or illness such as headaches, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, and infections.

Older Adult: The physiological changes associated with aging, effects of multiple medications, psychological factors, and acute or chronic disease increase the older adult’s risk for falls and other types of accidents. Falls often result in bruises, hip fractures, or head trauma. The risk of being seriously injured in a fall increases with age. Older patients are more likely to fall in the bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen. Environmental factors such as broken stairs, icy sidewalks, inadequate lighting, throw rugs, and exposed electrical cords cause many of the accidents. Inside falls most often occur while transferring from beds, chairs, and toilets; getting into or out of bathtubs; tripping over items such as cords covered by rugs or carpets, carpet edges, or doorway thresholds; slipping on wet surfaces; and descending stairs. Fear of falling is a concern of community-dwelling older adults, and many avoid activities because of their fear (Zijlstra et al., 2007). Falls can be decreased by multiple-component group exercise, Tai Chi, having a physician or pharmacist review all medications, having an eye examination annually, and decreasing hazards in the home that increase falls (Gillespie et al., 2009).

Individual Risk Factors

Other risk factors posing threats to safety include lifestyle, impaired mobility, sensory or communication impairment, and the lack of safety awareness.

Lifestyle: Some lifestyle choices increase safety risks. People who drive or operate machinery while under the influence of chemical substances (drugs or alcohol), work at inherently dangerous jobs, or are risk takers are at greater risk of injury. In addition, people experiencing stress, anxiety, fatigue, or alcohol or drug withdrawal or those taking prescribed medications are sometimes more accident prone. Because of these factors, some people are too preoccupied to notice the source of potential accidents such as cluttered stairs or a stop sign.

Impaired Mobility: A patient with impaired mobility has many kinds of safety risks. Muscle weakness, paralysis, and poor coordination or balance are major factors in falls. Immobilization predisposes patients to additional physiological and emotional hazards, which in turn further restrict mobility and independence. Persons who are physically challenged are at greater risk for injury when entering motor vehicles and buildings that are not handicapped accessible.

Sensory or Communication Impairment: Cognitive impairments associated with delirium, dementia, and depression place patients at greater risk for injury. These conditions contribute to altered concentration and attention span, impaired memory, and orientation changes. Patients with these alterations become easily confused about their surroundings and are more likely to have falls and burns. Patients with visual, hearing, tactile, or communication impairment such as aphasia or a language barrier are not always able to perceive a potential danger or express their need for assistance (see Chapter 49).

Lack of Safety Awareness: Some patients are unaware of safety precautions such as keeping medicine or poisons away from children or reading the expiration date on food products. A complete nursing assessment, including a home inspection, helps you identify the patient’s level of knowledge regarding home safety so you can correct deficiencies with an individualized nursing care plan.

Risks in the Health Care Agency

Patient safety continues to be one of the most pressing health care challenges in the nation. Medical errors are the eighth leading cause of death (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010). Medical errors happen when something that was planned as part of medical care doesn’t work out or when the wrong plan was used. They occur in all health care settings. You must be aware of regulatory and organizational safety initiatives and individual patient risk factors. The Joint Commission (TJC) and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have placed an increased emphasis on error prevention and patient safety. Their “Speak Up” campaign encourages patients to take a role in preventing health care errors by becoming active, involved, and informed participants on the health care team. For example, patients are encouraged to ask health care workers if they have washed their hands before providing care. National Patient Safety Goals of TJC (2011b) are specifically directed to reduce the risk of medical errors (Box 27-2). The goals are designed to promote specific improvements in patient safety and highlight ongoing problematic areas in health care. These evidence-based recommendations require health care facilities to focus their attention on a series of specific actions.

The National Quality Forum (NQF) (2011a) has the mission of improving the quality of health care in America by:

• Building consensus on national priorities and goals for performance improvement and working in partnership to achieve them;

• Endorsing national consensus standards for measuring and publicly reporting on performance; and

• Promoting the attainment of national goals through education and outreach programs.

Recently the NQF released its National Voluntary Consensus Standards for Public Reporting of Patient Safety Events (NQF, 2011b). The report provides a framework for publicly reporting patient safety information—including events, indicators, and measures—about health care organizations to consumers. It is important for nurses to understand the NQF standards and their intent since ultimately they influence the types of priorities that patient care organizations (e.g., hospitals, community health centers) set to improve the quality of care delivered to patients. Many of the NQF measures of patient safety (e.g., patient falls with injury, incidence of pressure ulcers, and central line bloodstream infection) are standards for judging the quality of care of health care organizations. The measures are also used by other organizations such as TJC and the CMS. Among the safety measures, the NQF endorsed a select list of serious reportable events (SREs), which was updated in 2006. The 28 events (Box 27-3) are a major focus of health care providers for patient safety initiatives. The CMS names select SREs as Never Events (i.e., adverse events that should never occur in a health care setting) (Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). The CMS now denies hospitals higher payment for any hospital-acquired condition resulting from or complicated by the occurrence of certain Never Events (Box 27-4). Many of the hospital-acquired conditions (e.g., fall or stage III pressure ulcer) are nurse-sensitive indicators, meaning that a nurse directly affects their development. The NQF (2010) also released 34 safe practices for better health care. Evidence supports the effectiveness of these practices in reducing the occurrence of adverse health care events.

Being aware of and engaged in activities focused on the prevention of these conditions not only enhances patient safety but also contributes to the overall success of the health care facility. The CMS believes that the Never Events will strengthen incentives by hospitals to develop safety practices and reduce health care costs in the long term. Health care facilities often conduct a failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) to identify problems with processes and products before they occur.

When an actual or potential adverse event occurs, the nurse or health care provider involved completes an incident or occurrence report. An incident report is a confidential document that completely describes any patient accident occurring on the premises of a health care agency (see Chapter 23). Reporting allows the organization to identify trends/patterns throughout the facility and areas to improve. Focusing on the root cause of an event instead of the individual involved promotes a “culture of safety” that helps in specifically identifying what contributed to an error. The probability of an accident occurring declines with adherence to evidence-based principles of safety (Taylor-Adams et al., 2009).

Nurses face specific environmental risks in health care facilities. An example is the various forms of chemicals used. Chemicals found in some medications (e.g., chemotherapy), anesthetic gases, cleaning solutions, and disinfectants are potentially toxic if ingested, absorbed into the skin, or inhaled. Material safety data sheets (MSDSs) are required resources available in any health care agency (Occupational Safety and Health Administration, 1996). The MSDS provides detailed information about the chemical, health hazards imposed, first aid guidelines, and precautions for safe handling and use. MSDSs give information on the steps to take in case the material is released or spilled. Be aware of the location of the MSDSs and be knowledgeable about hazardous chemicals in your environment. Spread of pathogens also presents a risk to both nurses and other patients. Therefore always follow standard and transmission-based isolation precautions, along with proper hand hygiene (see Chapter 28).

Specific risks to a patient’s safety within the health care environment include falls, patient-inherent accidents, procedure-related accidents, and equipment-related accidents. The nurse assesses for these four potential problem areas and, considering the developmental level of the patient, takes steps to prevent or minimize accidents.

Falls: Falls result in minor to severe injuries such as hip fractures or head trauma that result in reduced mobility and independence and increase the risk for premature death. Patients who have underlying disease states are more susceptible to fall-related injuries (Hughes, 2008). For example, a patient with a bleeding disorder is more likely to have an intracranial bleed; a patient with osteoporosis has a greater chance for fracture. The unfamiliar environment, acute illness, surgery, mobility status, medications, treatments, and placement of various tubes and catheters are common challenges that place patients of any age at risk of falling. Factors the nurse can influence include assessment and communication about patient risks, information access, signage, the environment, teamwork, and involving the patient and family (Dykes et al., 2009). Falls that result in injuries often extend a patient’s length of stay in the health care environment, placing them at an even greater risk for other complications.

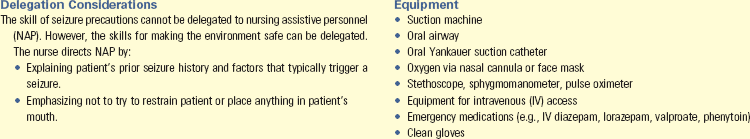

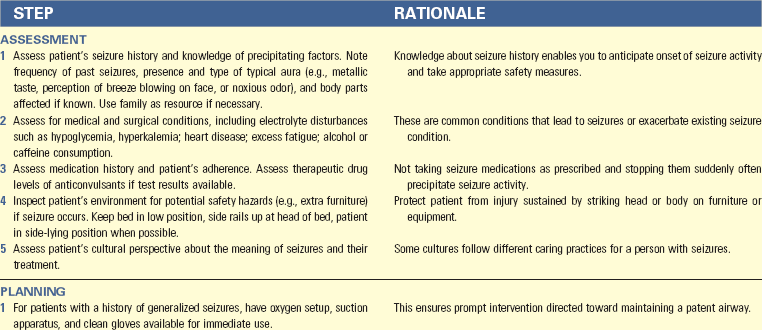

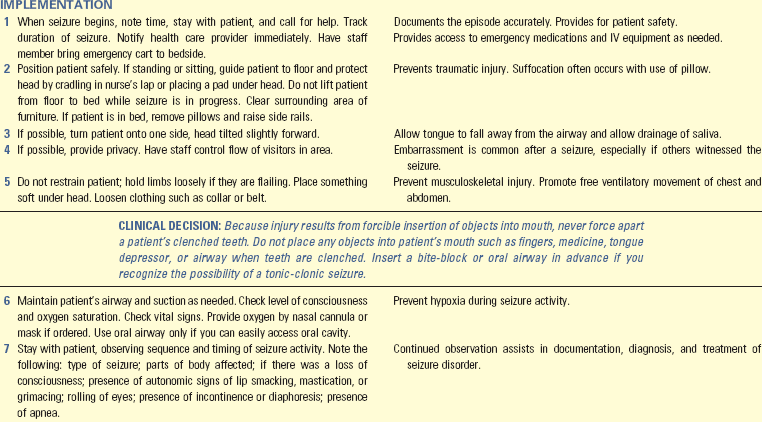

Patient-Inherent Accidents: Patient-inherent accidents are accidents (other than falls) in which the patient is the primary reason for the accident. Examples include self-inflicted cuts, injuries, and burns; ingestion or injection of foreign substances; self-mutilation or fire setting; and pinching fingers in drawers or doors. One of the more common precipitating factors for a patient-inherent accident is a seizure.

Procedure-Related Accidents: Procedure-related accidents are caused by health care providers and include medication and fluid administration errors, improper application of external devices, and accidents related to improper performance of procedures such as dressing changes or urinary catheter insertion. Nurses are able to prevent many procedure-related accidents by adhering to organizational policy and procedures and standards of nursing practice. For example, proper preparation and administration of medications, use of patient and medication bar coding, and “Smart” intravenous (IV) pumps reduce medication errors (see Chapters 31 and 41). All staff need to be aware that distractions and interruptions contribute to procedure-related accidents and need to be limited, especially during high-risk procedures such as medication administration. The potential for infection is reduced when surgical asepsis is used for sterile dressing changes or any invasive procedure such as insertion of a urinary catheter. Finally, correct use of safe patient handling techniques and equipment reduces the risk of injuries when moving and lifting patients (see Chapter 47).

Equipment-Related Accidents: Accidents that are equipment related result from the malfunction, disrepair, or misuse of equipment or from an electrical hazard. To avoid rapid infusion of IV fluids, all general-use and patient-controlled analgesic pumps need to have free-flow protection devices. To avoid accidents, do not operate monitoring or therapy equipment without adequate instruction. If faulty equipment is discovered, place a tag on it to prevent it from being used on another patient and promptly report any malfunctions. Assess potential electrical hazards to reduce the risk of electrical fires, electrocution, or injury from faulty equipment. In health care settings the clinical engineering staff make regular safety checks of equipment. Facilities must report all suspected medical device—related deaths to both the FDA and the manufacturer of the product if known (FDA, 2009). This is usually done in conjunction with the risk management department after tagging and removing the piece of equipment.

Critical Thinking

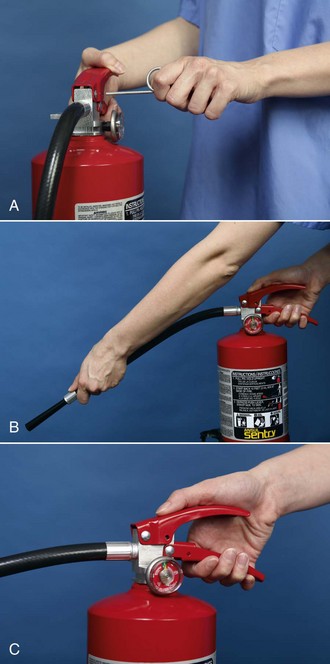

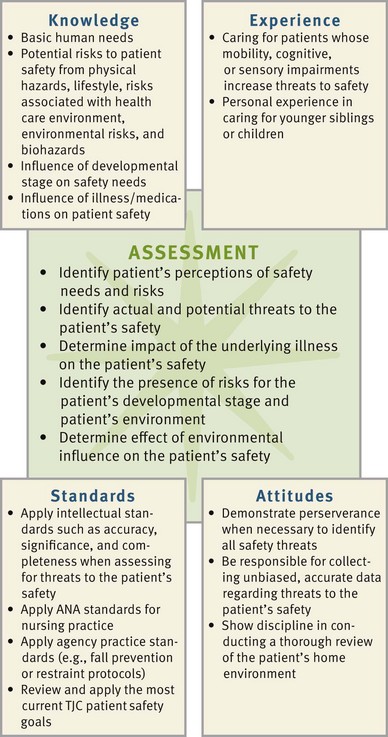

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require the nurse to anticipate necessary information, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care. Critical thinking is an ongoing process. During assessment (Fig. 27-3) you consider all critical thinking elements and information about the specific patient to make appropriate nursing diagnoses.

FIG. 27-3 Critical thinking model for safety assessment. ANA, American Nurses Association; TJC, The Joint Commission.

In the case of safety, the nurse integrates knowledge from nursing and other scientific disciplines, previous experiences in caring for patients who had an injury or were at risk, critical thinking attitudes such as responsibility and discipline, and any standards of practice that are applicable. For example, the American Nurses Association (ANA) standards for nursing practice address the nurse’s responsibility in maintaining patient safety. TJC (2011b) also provides standards for safety. You refer to all of this information and experience as you conduct a detailed assessment of a specific patient. For example, while assessing a specific patient’s home environment, you consider typical locations within the home where dangers commonly exist. If a patient has a visual impairment, you apply previous experiences in caring for patients with visual changes to anticipate how to thoroughly assess his or her needs. Critical thinking directs you to anticipate what needs to be assessed and how to make conclusions about available data.

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care.

Assessment

During the assessment process thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

Patients generally expect to be safe in health care settings and in their homes. However, there are times when a patient’s view of what is safe does not agree with that of the nurse and the standards he or she hopes to enforce. For this reason your assessment needs to be patient centered and include the patient’s own perceptions of his or her risk factors, knowledge of how to adapt to such risks, and previous experience with any accidents. This is important if you need to make changes in the patient’s environment. Patients usually do not purposefully put themselves in jeopardy. When they are uninformed or inexperienced, threats to their safety occur. You always need to consult patients or family members about ways to reduce hazards in their environment. To conduct a thorough patient assessment, consider possible threats to a patient’s safety, including the immediate environment and any individual risk factors. Ask the patient specific questions related to safety (Box 27-5).

Nursing History

A nursing history includes data about a patient’s level of wellness to determine if any underlying conditions exist that pose threats to safety. For example, give special attention to assessing a patient’s gait, lower-body muscle strength and coordination, balance, and vision. Consider a review of the patient’s developmental status as you analyze assessment information. Also review if the patient is taking any medications or undergoing any procedures that pose risks. For example, use of diuretics increases the frequency of voiding and results in the patient having to use toilet facilities more often. Falls often occur with patients who have to get out of bed quickly because of urinary urgency.

Health Care Environment

When the patient is cared for within a health care facility, you need to determine if any hazards exist in the immediate care environment. Does the placement of equipment (e.g., drainage bags, IV pumps) or furniture pose barriers when the patient attempts to ambulate? Does positioning of the patient’s bed allow him or her to easily reach items on a bedside table or stand? Does the patient need assistance with ambulation? Are there multiple tubes or IV lines? Is the call bell within reach? The nurse collaborates with clinical engineering staff to make sure that equipment functions properly and is in good condition.

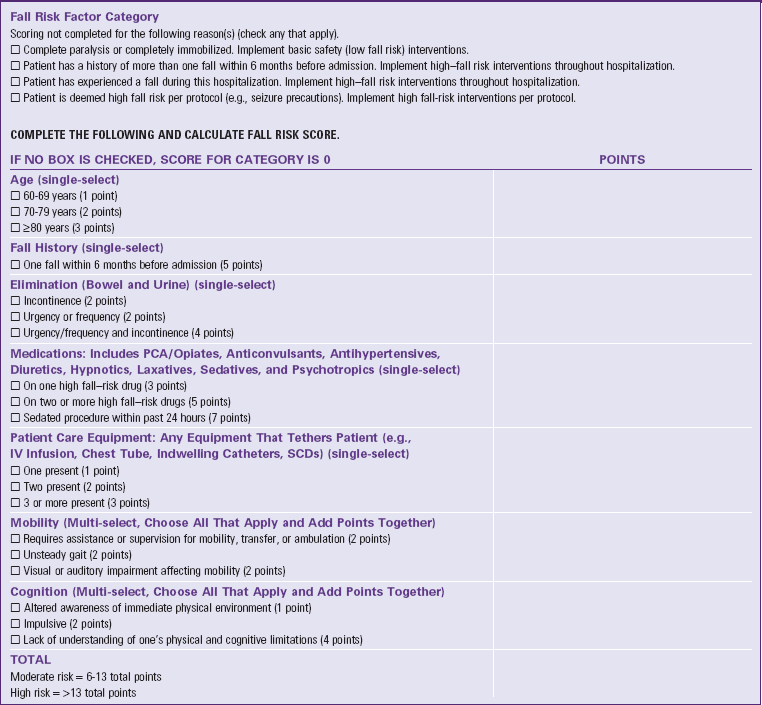

Risk for Falls: Assessment of a patient’s risk factors for falling is essential in determining specific needs and developing targeted interventions to prevent falls. Many different fall assessment instruments are available; use the tool chosen by your health care agency. A fall assessment tool (Table 27-1) helps you assess important risk factors. At a minimum the assessment needs to be completed on admission, following a change in the patient’s condition, after a fall, and when transferred. If it is determined that the patient is at risk for falling, regular assessment always continues. In many cases family members are important resources in assessing a patient’s fall risk. Families often are able to report on the patient’s level of confusion and ability to ambulate. Based on the results of a fall risk assessment, you implement multiple evidence-based interventions. It is very important to inform a patient and family members about the patient’s risks. Often younger patients are not aware of how medications and treatments cause dizziness, orthostatic hypotension, or changes in balance. When patients are unaware of their risks, they are less likely to ask for assistance. If family members are informed, they will often call for help (when they are visiting patients) to be sure that patients are appropriately assisted.

Risk for Medical Errors: Be alert to factors within your own work environment that create conditions in which medical errors are more likely to occur. Studies show that overwork and fatigue cause a significant decrease in alertness and concentration, leading to errors (Trinkoff et al., 2006). It is important for you to be aware of these factors and include checks and balances when working under stress. For example, to reduce the potential for a medical error, it is essential for you to check the patient’s identification by using two identifiers (e.g., name and birthday or name and account number) according to facility policy before beginning any procedure or administering a medication (see Chapter 31).

Disasters: Hospitals must be prepared to respond and care for a sudden influx of patients at the time of a community disaster. Guidelines for a disaster response are included in a facility emergency management plan. All hospitals conduct disaster drills on a routine basis. Communication is a key to any emergency management plan. Nurses must know what happened, how many patients to expect, and when patients will begin to arrive so they can prepare both themselves and their facility. Although the occurrence of a bioterrorist attack has been limited to the anthrax deaths following September 11, 2001, the threat is very real. Be prepared to make accurate and timely assessments in any type of setting. A bioterrorist attack will likely resemble a natural outbreak initially. Acutely ill patients representing the earliest cases after a covert attack seek care in emergency departments. Patients less ill at the onset of an illness possibly seek care in primary care settings. Basic epidemiological principles exist to assess whether a patient’s presentation of symptoms is typical of an endemic disease or an unusual event that raises concern. Features that alert nurses to the possibility of a bioterrorism-related outbreak include the following (Dire, 2008):

• Disease (or strain) not endemic

• Unusual antibiotic resistance patterns

• Atypical clinical presentation

• Case distribution geographically (from same location) and/or temporally inconsistent

• Other inconsistent elements (e.g., number of cases, mortality and morbidity rates, deviations from disease occurrence baseline)

Patient’s Home Environment

When caring for a patient in the home, a home hazard assessment is necessary. See http://homesafetycouncil.org/safetyguide for a sample home assessment guide. A thorough hazard assessment covers topics such as adequacy of lighting (inside and outdoors), presence of safety devices, placement of furniture or other items that can create barriers, condition of flooring, and safety in the kitchen and bathrooms. Know where medications and cleaning supplies are located. Walk through the home with the patient and discuss how he or she normally conducts daily activities and whether the environment poses problems. Assess for the presence of locks on doors and windows that make the home less susceptible to intruders. When assessing the adequacy of lighting, inspect the areas where the patient moves and works such as outside walkways, steps, interior halls, and doorways. Getting a sense of the patient’s routines helps you recognize less obvious hazards.

Assessment for risk of food infection or poisoning includes assessing a patient’s knowledge of food preparation and storage practices. For example, does a patient know to check expiration dates of prepared food and milk products? Does he or she keep foods in the refrigerator that are fresh and not spoiled? Does the patient clean fresh fruits and vegetables correctly before eating them? Assess for clinical signs of infection by conducting an examination of GI and central nervous system function, observing for a fever, and analyzing the results of cultures of feces and emesis. In the home inspect suspected food and water sources and assess the patient’s handwashing practices. It is useful to ask patients when they routinely wash their hands. This then prompts a helpful discussion about the purpose and importance of handwashing.

Assessment of the environmental comfort of a patient’s home includes a review of when the patient normally has heating and cooling systems serviced. Does the patient have a functional furnace or space heater? Does the home have air conditioning or fans? You need to inform patients who use space heaters of the risk for fires. Are smoke detectors, carbon monoxide detectors, and fire extinguishers present and placed strategically throughout the home and checked routinely?

When patients live in older homes, encourage them to have inspections for the presence of lead in paint, dust, or soil. Because lead also comes from the solder or plumbing fixtures in a home, patients need to have water from each faucet tested. Local health offices will help homeowners locate a trained lead inspector who takes samples from various locations and has them analyzed at a laboratory for lead content.

It is important that your assessment help individuals focus on avoiding losses and reducing their risk for injury associated with disasters. The FEMA (http://www.fema.gov/) and the American Red Cross (http://www.redcross.org/) provide nationwide education to help community members prepare for disasters of all types.

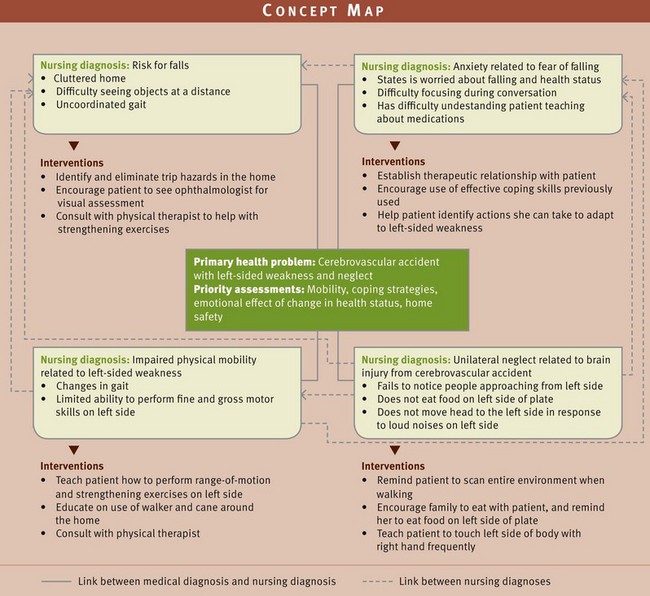

Nursing Diagnosis

Gather data from your nursing assessment and analyze clusters of defining characteristics to identify relevant nursing diagnoses. Include specific related or contributing factors to individualize your nursing care (Box 27-6). For example, the nursing diagnosis risk for injury is sometimes related to altered mobility or sensory alteration (e.g., visual). Altered mobility leads you to select such nursing interventions as range-of-motion (ROM) exercises or teaching the proper use of safety devices such as side rails, canes, or crutches. Visual impairment as the related factor leads you to select different interventions such as keeping the area well lit; orienting the patient to the surrounding; or keeping eye glasses clean, handy, and well protected. When you do not identify the correct related factor, the use of inappropriate interventions increases a patient’s risk for injury. For example, not evaluating the home environment for hazards possibly results in sending a hospitalized patient home only to return with an additional injury. Nursing diagnoses for patients with safety risk include the following:

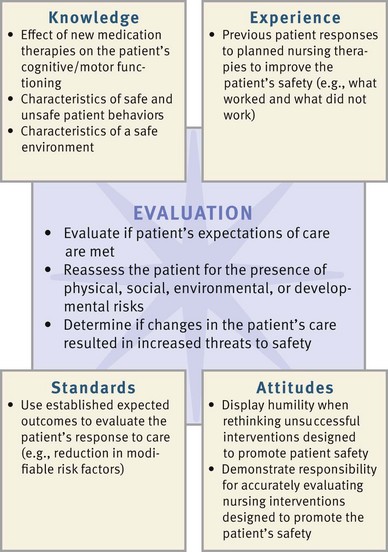

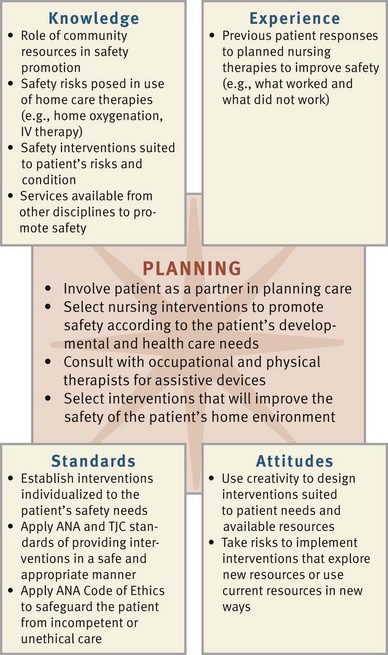

Planning

Patients with actual or potential risks to safety require a nursing care plan with interventions that prevent and minimize threats to their safety. Design your interventions to help a patient feel safe to move about and interact freely within the environment. The total plan of care addresses all aspects of patient needs and uses resources of the health care team and the community when appropriate. Critically synthesize information from multiple sources (Fig. 27-4). Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care integrates all that you learned about the patient and the key critical thinking elements. For example, you reflect on knowledge regarding the services that other disciplines (e.g., occupational therapy, case management) provide in helping patients return to their home environments safely. Also reflect on any previous experience when a patient benefited from safety interventions. Such experience helps you adapt approaches with each new patient. Applying critical thinking attitudes such as creativity helps you to collaborate with the patient in planning interventions that are relevant and most useful, particularly when making changes in the home environment.

FIG. 27-4 Critical thinking model for safety planning. ANA, American Nurses Association; TJC, The Joint Commission.

Goals and Outcomes

You collaborate with the patient, family, and other members of the health care team when setting goals and expected outcomes during the planning process (see the Nursing Care Plan). The patient who is an active participant in reducing threats to safety becomes more alert to potential hazards and is more likely to adhere to the plan. Make sure that goals and outcomes for each nursing diagnosis are measurable and realistic, with consideration of the resources available to the patient. For example, in the case of the nursing diagnosis of impaired physical mobility related to left-sided paralysis, the goal is the patient “remains free of injury by discharge.” Examples of expected outcomes include:

Setting Priorities

Prioritize a patient’s nursing diagnoses and interventions to provide safe and efficient care. For example, the patient described in the concept map (Fig. 27-5) has several nursing diagnoses. The patient’s mobility problem is an obvious priority because of its influence on risk for falls and skin integrity. Plan individualized interventions based on the severity of risk factors and the patient’s developmental stage, level of health, lifestyle, and cultural needs (Box 27-7). Planning involves an understanding of the patient’s need to maintain independence within physical and cognitive capabilities. Collaborate to establish ways of maintaining the patient’s active involvement within the home and health care environment. Education of the patient and family is also an important intervention to plan for reducing safety risks over the long term.

Teamwork and Collaboration

Collaboration with the patient, family, and other disciplines such as social work and occupational and physical therapy become an important part of the patient’s plan of care. For example, a hospitalized patient may need to go to a rehabilitation facility to gain strength and endurance before being discharged home. Communication is essential. You communicate risk factors and the plan of care with the patient, family, and other health care providers, including other disciplines and nurses on other shifts. Permanent dry-erase boards in the patient room with patient information such as activity and level of assistance communicate information to all health care providers. A standard approach to communication such as SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation) helps you obtain and organize information (see Chapter 26).

Patients need to be able to identify, select, and know how to use resources within their community (e.g., neighborhood block homes, local police departments, and neighbors willing to check on their well-being) that enhance safety. Make sure that the patient and family understand the need for these resources and are willing to make changes that promote their safety.

Implementation

The QSEN (2011) project outlines recommended skills to ensure nurse competency in patient safety. Among these skills are those involving safe nursing practice during direct care:

• Demonstrate effective use of technology and standardized practices that support safety and quality.

• Demonstrate effective use of strategies to reduce risk of harm to self or others.

• Use appropriate strategies to reduce reliance on memory (such as forcing functions, checklists).

Direct your nursing interventions toward maintaining the patient’s safety in all types of settings. You implement health promotion and illness prevention measures in the community setting, whereas prevention is a priority in the acute care setting.

Health Promotion

To promote an individual’s health, it is necessary for the individual to be in a safe environment and practice a lifestyle that minimizes risk of injury. Edelman and Mandle (2010) describe passive and active strategies aimed at health promotion. Passive strategies include public health and government legislative interventions (e.g., sanitation and clean water laws) (see Chapter 3). Active strategies are those in which the individual is actively involved through changes in lifestyle (e.g., wearing seat belts or installing outdoor lighting) and participation in wellness programs.

Nurses participate in health promotion activities by supporting legislation, acting as positive role models, and working in community-based settings. Because environmental and community values have the greatest influence on health promotion, community and home health nurses are able to assess and recommend safety measures in the home, school, neighborhood, and workplace.

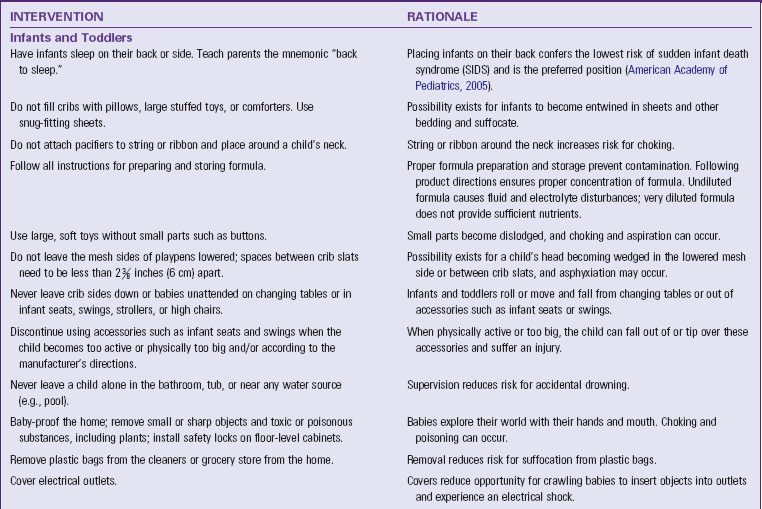

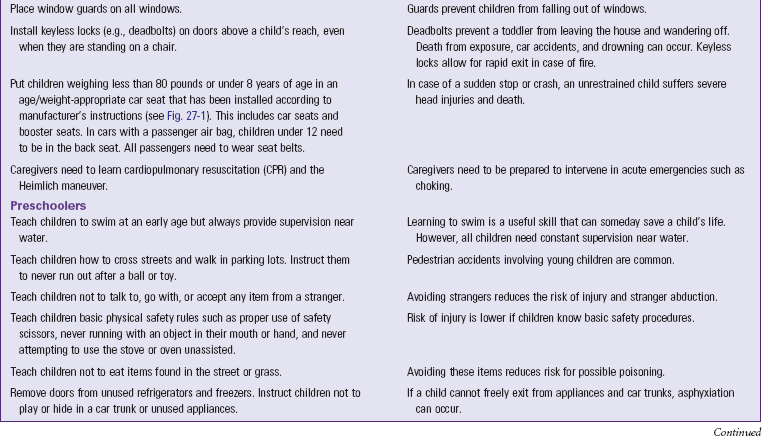

Infant, Toddler, and Preschooler: Growing, curious children need adults to protect them from injury. Children are trusting of their environment and do not perceive themselves to be in danger. Educate parents or guardians about reducing risks of injuries to children and ways to promote safety in the home (Table 27-2). Nurses working in prenatal and postpartum settings easily incorporate safety into the care plan of the childbearing family. Community health nurses assess the home and show parents how to promote safety. Educate parents about the importance of immunizations and how they protect a child from life-threatening disease.

School-Age Child: School-age children increasingly explore their environment (see Chapter 12). They have friends outside their immediate neighborhood; and they become more active in school, church, and community activities. The school-age child needs specific teaching regarding safety in school and at play. See Table 27-2 for nursing interventions to help guide the parent in providing for the safety of the school-age child.

Adolescent: Risks to the safety of adolescents involve many factors outside the home because much of their time is spent away from home and with their peer group (see Chapter 12). Adults serve as role models for adolescents and, through providing examples, setting expectations, and providing education, help them minimize risks to their safety. This age-group has a high incidence of suicide because of feelings of decreased self-worth and hopelessness. Be aware of the risks posed at this time and be prepared to teach adolescents and their parents measures to prevent accidents and injury.

Adult: Risks to young and middle-age adults frequently result from lifestyle factors such as childrearing, high stress levels, inadequate nutrition, use of firearms, excessive alcohol intake, and substance abuse (see Chapter 13). In this fast-paced society there also appears to be more expression of anger, which can quickly precipitate accidents related to “road rage.” Help adults understand their safety risks and guide them in making lifestyle modifications by referring them to resources such as classes to help quit smoking and for stress management, including employee-assistance programs. Also encourage adults to exercise regularly, maintain a healthy diet, practice relaxation techniques, and get adequate sleep.

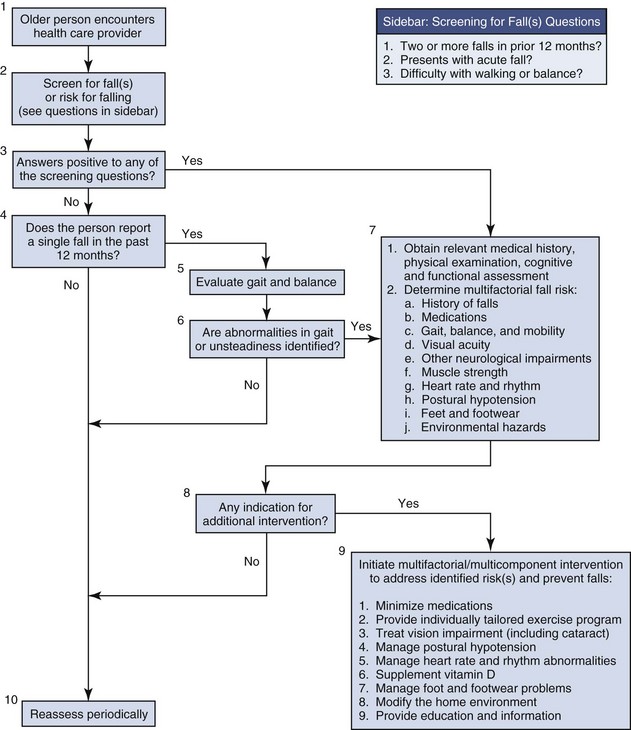

Older Adult: Nursing interventions for older adults reduce the risk of falls and other accidents and compensate for the physiological changes of aging (Box 27-8). Most injuries to older adults involve falls, automobile accidents, and those related to burns or fires (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2010b). Advancing age and the concurrent physiological changes in vision, hearing, mobility, reflexes, circulation, and the ability to make quick judgments all predispose older adults to falls (see Chapter 14). Certain disease states common to older adults such as arthritis or strokes and the effects of many medications such as sedatives, diuretics, and anticoagulants also increase the chance of injury. The American Geriatric Society (2009) developed an algorithm on prevention of falls (Fig. 27-6). Hospitalization or any unfamiliar environment, confusion, multiple medical problems, various medications, immobility concerns, urinary urgency, age-related sensory changes, and postural instability are major contributors to falling (Meiner, 2011). Provide information about neighborhood resources to help the older adult maintain an independent lifestyle. Older adults frequently relocate to new neighborhoods and need to become acquainted with new resources such as modes of transportation, church schedules, and food resources (e.g., Meals on Wheels).

FIG. 27-6 American Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Guideline Fall Prevention Algorithm 2010. (From American Geriatrics Society/British Geriatrics Society: Clinical practice guideline for prevention of falls in older persons, 2010, accessed May 25, 2011, from http://www.medcats.com/FALLS/frameset.htm.)

Educate patients regarding safe driving tips (e.g., driving shorter distances or only in daylight, using side and rearview mirrors carefully, and looking behind them toward their “blind spot” before changing lanes). If hearing is a problem, encourage the patient to keep a window rolled down while driving or reduce the volume of the radio or CD player. Counseling is often necessary to help older patients make the decision of when to stop driving. At that time help locate resources in the community that provide transportation.

Burns and scalds are also more apt to occur with older people because they sometimes forget and leave hot water running or become confused when turning the dials on a stove or other heating appliance. Nursing measures for preventing burns minimize the risk from impaired vision. Hot water faucets and dials are color coded to make it easier for the adult to know which is hot and which is cold. Reducing the temperature of the hot water heater is also very beneficial.

Many older adults love to walk. Reduce pedestrian accidents for older adults and all other age-groups by persuading people to wear reflectors on garments when walking at night; stand on the sidewalk and not in the street when waiting to cross a street; always cross at corners and not in the middle of the block (particularly if the street is a major one); cross with the traffic light and not against it; and look left, right, and left again before entering the street or crosswalk.

Environmental Interventions: Nursing interventions directed at eliminating environmental threats include those associated with a person’s basic needs and general preventive measures.

Basic Needs: Nurses contribute to a safer environment by helping patients meet basic needs related to oxygen, nutrition, and temperature. When oxygen is in use, precautions must be taken to prevent fire. Contact with heat or a spark is required to trigger combustion; therefore certain precautions are necessary, regardless of the setting where oxygen is in use. Post “No Smoking” and “Oxygen in Use” signs in patient rooms. Do not use oxygen around electrical equipment or flammable products. Store oxygen tanks upright in carts or stands to prevent tipping or falling or place the tanks flat on the floor when not in use. Check tubing for kinks that would affect the oxygen flow. Maintain oxygen at the prescribed liter flow and do not change without a health care provider’s order. Additional precautions are indicated for liquid or pressurized oxygen and when traveling with home oxygen. Refer to the oxygen supplier. In the home recommend that the patient be sure to have annual inspections of heating systems, chimneys, and fuel-burning appliances. Carbon monoxide detectors are available at a reasonable cost but are not a replacement for proper use and maintenance of fuel-burning appliances.

Teach basic techniques for food handling and preparation so nutritional needs are met safely:

• Proper refrigeration, storage, and preparation of food decrease the risk of foodborne illness. Store perishable foods in refrigerators to maintain freshness.

• Wash hands before preparing foods.

• Rinse fruits and vegetables thoroughly.

• Pay attention to prevent cross-contamination of one food with another during food preparation, especially with poultry.

• Use a separate cutting board for vegetables, meats, and poultry.

• Adequately cook foods to kill any residual organisms. Refrigerate leftovers promptly. Bacteria grow quickly at room temperature.

• Have family caregivers label the date when leftovers are saved.

General Preventive Measures: Adequate lighting and security measures in and around the home, including the use of night-lights, exterior lighting, and locks on windows and doors, enable patients to reduce the risk of injury from crime. The local police department and community organizations often have safety classes available for residents to learn how to take precautions to minimize the chance of becoming involved in a crime. For example, some useful tips include always parking the car near a bright light or busy public area, carrying a whistle attached to the car keys, keeping car doors locked while driving, and always paying attention while driving to notice if anyone starts to follow the car.

Modifications in the environment easily reduce the risk of falls. To reduce the risk of injury in the home, remove all obstacles from halls and other heavily traveled areas. Necessary objects such as clocks, glasses, or tissues remain on bedside tables within reach of the patient but out of the reach of children. Take care to ensure that end tables are secure and have stable, straight legs. Place nonessential items in drawers to eliminate clutter. If small area rugs are used, secure them with a nonslip pad or skid-resistant adhesive strips. Make sure that carpeting on the stairs is secured with carpet tacks. If patients have a history of falling and live alone, recommend that they wear an electronic safety alert device. When activated by the wearer, this device alerts a monitoring site to call emergency services for assistance.

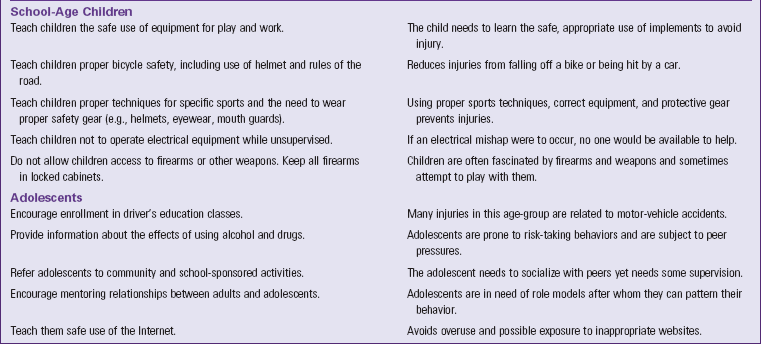

Accidental home fires typically result from smoking in bed, placing cigarettes in trash cans, grease fires, improper use of candles or space heaters, or electrical fires resulting from faulty wiring or appliances. Teach patients and families how to reduce the risk of electrical injury in the home (Box 27-9) and how to use a home fire extinguisher (Box 27-10). To reduce the risk of fires in the home, instruct patients to quit smoking or smoke outside the home. Have them inspect the condition of cooking equipment and appliances, particularly irons and stoves. For patients with visual deficits, it helps to have dials installed with large numbers or symbols on temperature controls. Make sure that smoke detectors are in strategic positions throughout the home so the alarm will alert the occupants in a home in case of fire. Make sure that all patients, even young children, are familiar with the phrase “stop, drop, and roll,” which describes what to do when a person’s clothing or skin is burning.

Help parents reduce the risk of accidental poisoning by teaching them to keep hazardous substances such as medications, cleaning fluids, and batteries out of the reach of children. Drug and other substance poisonings in adolescents and adults are commonly related to suicide attempts or drug experimentation. Teach parents that calling a poison control center for information before attempting home remedies will save their child’s life. Guidelines for accepted interventions for accidental poisonings are available to teach a parent or guardian (Box 27-11). Older adults are also at risk for poisoning because diminished eyesight may cause an accidental ingestion of a toxic substance. In addition, the impaired memory of some older adults results in an accidental overdose of prescription medications.

Be sure that medications are kept in their original containers and labeled in large print. Recommend the use of medication organizers that are filled once a week by the patient and/or family. Have patients keep poisonous substances out of the bathroom and discard old or unused medications. In the health care setting it is important for you to know how to respond when exposure to a poisonous substance occurs. In addition, adhere to guidelines for intervening in accidental poisoning. Ensure the poison control center phone number is visible near the telephone in homes with young children. In all cases of suspected poisoning, patients need to call this number immediately.

To prevent the transmission of pathogens, nurses teach aseptic practices. Medical asepsis, which includes hand hygiene and environmental cleanliness, reduces the transfer of organisms (see Chapter 28). Patients and family members need to learn thorough hand hygiene (handwashing or use of hand rub) and when to use it (e.g., before and after caring for a family member, before food preparation, before preparing a medication for a family member, after using the bathroom, and after contacting any body fluids). Patients also need to know how to dispose of infected material such as wound dressings and used needles in the home setting. Heavy plastic containers such as hard, colored plastic liquid detergent bottles are excellent for needle disposal. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) encourages disposal of used needles by way of community drop-off programs, household hazardous waste facilities, sharps mail-back programs, or home needle destruction devices (Coalition for Safe Community Needle Disposal, 2010). Teach patients “safe sex” practices, including abstinence, correct use of condoms, and engaging in monogamous relationships to reduce the risk for sexually transmitted infections.

Acute Care

Nurses use standard precautions for all patients to protect themselves from contact with blood and other potentially infectious body fluids (see Chapter 28). Additional specific safety measures are applicable to patients in the acute care environment. Nurses are responsible for making a patient’s bedside safe. Explain and demonstrate to patients how to use the call light or intercom system and always place the call device close to the patient at the conclusion of every nurse-patient interaction. Respond quickly to call lights and bed/chair alarms. Keep the environment free from clutter around the bedside. Many health care organizations are implementing hourly rounding to reduce falls (Box 27-12). In addition, nurses sometimes apply color-coded wristbands to patients’ wrists to communicate a patient’s fall risk. In 2008 the American Hospital Association issued an advisory recommending that hospitals standardize wristband colors; red for patient allergies, yellow for fall risk, and purple for do-not-resuscitate preferences. This recommendation came after a near-miss incident in which a nurse working in two different hospitals placed a wrong-colored band on a patient. Many state hospital associations and communities are now standardizing colors to reduce confusion both within and across the health care organizations (American Hospital Association, 2008). The nurse takes measures to help patients avoid falls, injuries from use of restraints and side rails, fires, poisoning, and electrical hazards. Special precautions are necessary to prevent injury in patients susceptible to having seizures. Radiation injuries are also a specific safety concern. Finally be prepared to respond to a disaster emergency, including a bioterrorist attack.

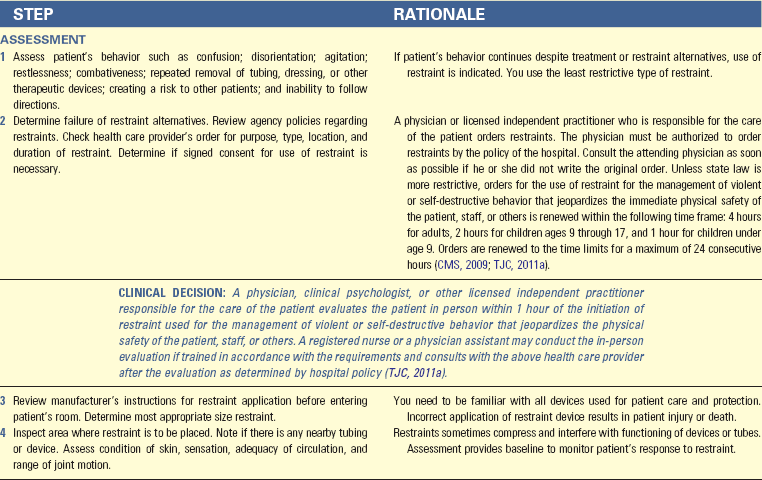

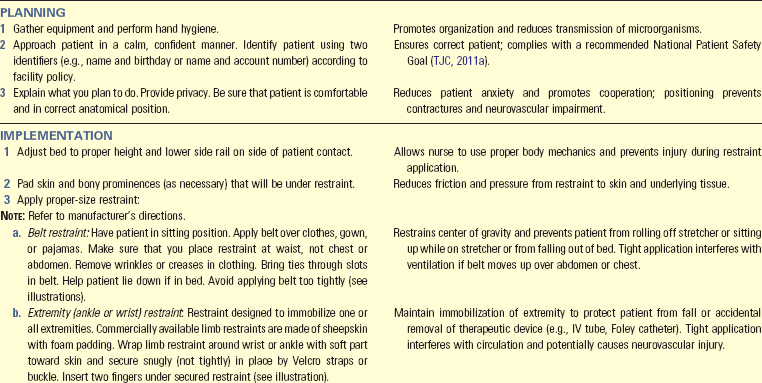

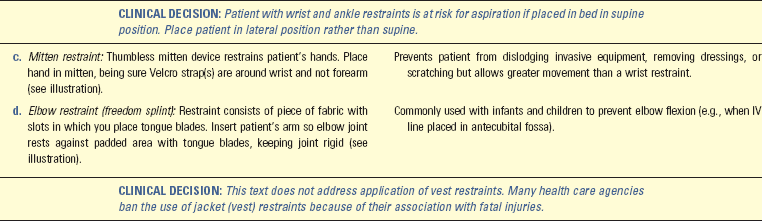

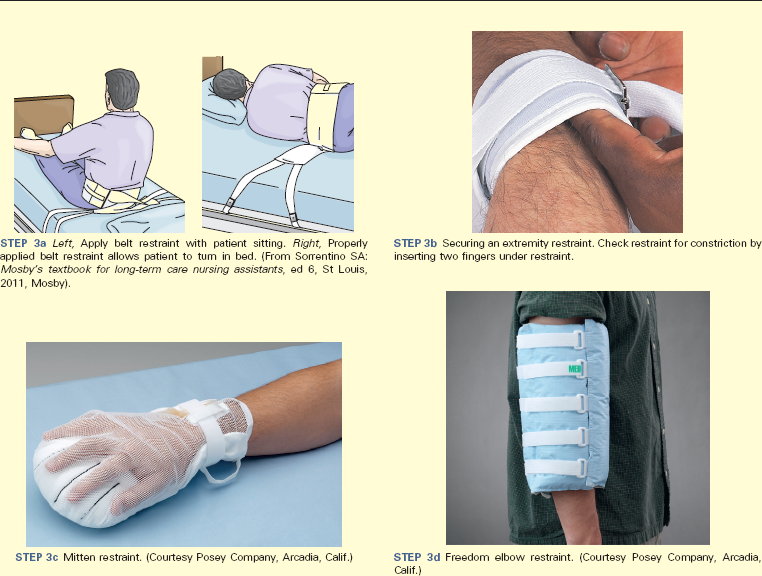

Falls: Most hospitals have fall prevention protocols instituted for patients at risk for falling. For example, a patient receives a fall risk identification bracelet (yellow in color), is given information about fall risks, and receives additional nursing interventions (e.g., hourly rounding, placement on a low safety bed, yellow gown). Include family members in safety discussions. A gait belt provides a secure way to steady or guide patients who need assistance with ambulation when transferring or walking. Use additional safety equipment as needed when moving patients (see Chapter 47). When patients use assistive aids such as canes, crutches, or walkers, it is important to routinely check the condition of rubber tips and the integrity of the aid. Remove excess furniture and equipment and make sure that patients wear rubber-soled shoes or slippers for walking or transferring. Safety bars near toilets (Fig. 27-7), locks on beds and wheelchairs (Fig. 27-8), and call lights are additional safety features found in health care settings. In the health care environment frequent observations of the patient at risk for falls are important to reduce the potential for injury (Meade et al., 2006).

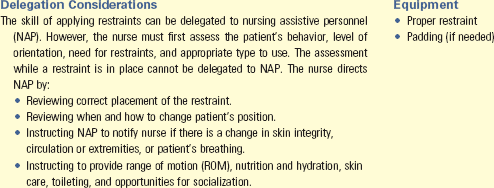

Restraints: Patients who are confused, disoriented, or repeatedly fall or try to remove medical devices (e.g., oxygen equipment, IV lines, or dressings) often require the temporary use of restraints to keep them safe. Restraints are not a solution to a patient problem but rather a temporary means to maintain patient safety. They are either chemical or physical. Chemical restraints are medications such as anxiolytics and sedatives used to manage a patient’s behavior and are not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition. A physical restraint is any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely (TJC, 2011a). A restraint does not include devices such as orthopedically prescribed devices, surgical dressings or bandages, protective helmets, or other methods that involve physically holding a patient to conduct routine physical examinations or tests, protecting the patient from falling out of bed, or permitting the patient to participate in activities without the risk of physical harm (TJC, 2011a).

The use of restraints is associated with serious complications resulting from immobilization such as pressure ulcers, pneumonia, constipation, and incontinence. In some cases death has resulted because of restricted breathing and circulation. Patients have been strangled while trying to get out of bed while restrained in a jacket or vest restraint. As a result, many health care facilities have eliminated the use of the jacket (vest) restraint (Capezuti et al., 2008). Loss of self-esteem, humiliation, and agitation are also serious concerns. Because of these risks, legislation emphasizes reducing the use of restraints. Regulatory agencies such as TJC and the CMS enforce standards for the safe use of restraint devices. The optimal goal for all patients is a restraint-free environment. Always consider and implement alternatives to restraints first. Individualize your approaches for each patient. Restraint alternatives include more frequent observations, involvement of family during visitation, frequent reorientation, and the introduction of familiar and meaningful stimuli (e.g., knitting or crocheting or looking at family photos) within the environment to reduce behaviors such as wandering that often leads to restraint use (Box 27-13).

In nursing homes, evidence shows that outcomes related to behavior issues, cognitive performance, falls, walking dependence, activities of daily living, pressure ulcers, and contractures are significantly worse when a restraint is used compared to no restraint (Castle, 2009). An interdisciplinary approach that includes individualized assessments and development of structured treatment plans reduces restraint use.

The use of restraints involves a psychological adjustment for the patient and family. If restraints are necessary, the nurse assists family members and patients by explaining their purpose, expected care while the patient is restrained, precautions taken to avoid injury, and that the restraint is temporary and protective. Informed consent from family members is sometimes required before using restraints (e.g., in long-term care settings).

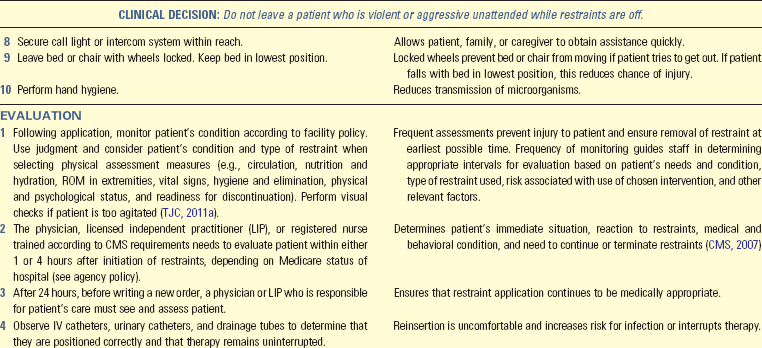

For legal purposes know agency-specific policy and procedures for appropriate use and monitoring of restraints. The use of a restraint must be clinically justified and a part of the patient’s prescribed medical treatment and plan of care. A physician’s order is required, based on a face-to-face assessment of the patient. The order must be current, state the type and location of restraint, and specify the duration and circumstances under which it will be used. These orders need to be renewed within a specific time frame according to the policy of the agency. In the hospital each original restraint order and renewal is limited to 4 hours for adults, 2 hours for ages 9 through 17, and 1 hour for children under age 9 (CMS, 2009; TJC, 2011a). Orders may be renewed to the time limits for a maximum of 24 consecutive hours. Restraints are not to be ordered prn (as needed). You must conduct ongoing assessment of patients who are restrained. Proper documentation, including the behaviors that necessitated the application of restraints, the procedure used in restraining, the condition of the body part restrained (e.g., circulation to hand), and the evaluation of the patient response, is essential. Restraints must be removed periodically, and the nurse assesses the patient to determine if they continue to be necessary. Skill 27-1 on pp. 388-392 includes guidelines for the proper use and application of restraints. Use of restraints must meet one of the following objectives:

• Reduce the risk of patient injury from falls

• Prevent interruption of therapy such as traction, IV infusions, nasogastric (NG) tube feeding, or Foley catheterization

• Prevent patients who are confused or combative from removing life-support equipment

In keeping with current safety trends, electronic devices are also sometimes used as alternatives to restraints. For example, the Ambularm, worn on the leg, signals when the leg is in a dependent position such as over the side rail or on the floor (Fig. 27-9). You also sometimes place weight-sensitive sensor mats on patients’ mattresses or in the chair. An audible alarm sounds at the bedside when pressure is released off the sensor mat. The alarm often signals at the central nurses’ station so staff is alerted quickly when a patient is up and out of bed. Alarms on doors also alert staff or family members when a patient who is confused, disoriented, or prone to wandering opens a door.

A less-restrictive restraint is the Posey bed (Fig. 27-10). It is a soft-sided, self-contained enclosed bed that is much less restrictive than chemical or physical restraints. It allows for freedom of movement and thus reduces the side effects such as pressure ulcers and loss of dignity caused by physical restraints. A vinyl top covers the padded upper frame of the bed, and the nylon-net canopy surrounds the mattress and completely encloses the patient in the bed. Zippers on the four sides of the enclosure provide access to the patient. The Posey bed enclosure works well for patients who are restless and unpredictable, cognitively impaired, and at risk for injury if they were to fall or get out of bed such as patients on anticoagulant therapy at risk for intracranial bleed. The bed is also a safer alternative to side rails.

Side Rails: Side rails help to increase a patient’s mobility and/or stability when in bed or moving from bed to chair. They are the most commonly used physical restraint. There are a variety of beds with different side rail designs. Basically the patient needs to have a route to exit a bed safely and maneuver freely within the bed; in this case side rails are not considered a restraint. For example, raising only the top two side rails so the lower part of the bed is open gives the patient room to exit a bed safely. Side rails used to prevent a patient such as one who is sedated from falling out of bed are not considered a restraint. Always check agency policy about the use of side rails. Be sure that a bed is in the lowest position possible when side rails are raised. Always assess the risk of using side rails compared to not using them. Check their condition; bars between the bed rails need to be closely spaced to prevent entrapment, the space between bed rails and mattress and between headboard and mattress is filled to prevent patients from falling in between, and latches securing bed rails are stable.