Chapter 40 The normal baby

The normal neonate continues to adapt to extrauterine life in the first weeks after birth, remaining vulnerable to airway obstruction, hypothermia, hypoglycaemia and infection. This necessitates the provision of an environment that is optimal for physiological needs. The mother takes responsibility for this by continuing to develop and nurture the mother–baby relationship. The father should also play his part and become involved in the care of his baby. It is important for the midwife to remember that after the birth of his baby, a father may display strong emotional feelings towards his child (Ratnaike 2007).

Extrauterine life presents a challenge to the newborn baby. The most important changes – those in the heart and lungs – take place at birth (see Ch. 39); however, continued adaptations are necessary in the first weeks of life as the baby assumes independence from the maternal and placental nurturing which was enjoyed before birth. The baby remains dependent on the mother or other caregiver for nutrition and protection, but is solely responsible for maintaining metabolism and homeostasis among other functions essential for survival.

General characteristics

Appearance

A normal term baby weighs approximately 3.5 kg, when fully extended measures 50 cm from the crown of the head to the heels, and has on average an occipitofrontal head circumference of 34–35 cm. Most babies are plump and have a prominent abdomen. They lie in an attitude of flexion; with arms extended, their fingers reach upper thigh level.

Physiology

The skin

The skin is the largest organ in the body and is made up of three main layers, the epidermis, the dermis and the underlying subcutaneous fatty tissue. The skin has an important role to play in temperature regulation, it acts as a barrier to infection, balances electrolytes, stores fat and insulates against the cold. It can also give the midwife a guide to the overall well-being of the baby. Vernix caseosa is a white sticky substance, present on the baby’s skin at birth. The amount of vernix is variable. It is thought to have a protective function in utero and after birth dries up and flakes off within a few hours.

The midwife must be knowledgeable about the normal parameters of neonatal skin, which differs somewhat from adult skin (Michie 1996).

The skin of a newborn baby is thin, delicate, and easily traumatized by friction, pressure or substances with a different pH. This renders the skin prone to blistering, excoriation and infection. Although sterile at birth, the skin is colonized by micro-organisms within 24 hrs. The skin of babies born at term has a pH of 6.4, which reduces to 4.9 over 3–4 days (Irving 2001). The low pH of the skin surface (pH<5) creates an ‘acid mantle’, which protects against infection. Baby products along with exposure to urine and faeces could disrupt this delicate protective barrier (Cetta et al 1991).

The best practice based on recent research suggests that the usage of baby products is superfluous to the care of the baby’s skin (Trotter 2004) and this is supported by the Postnatal Care Guidelines (NICE 2006).

The umbilical cord’s position on the anterior abdominal wall predisposes it to contamination from urine and faeces. Post delivery, the stump is rapidly colonized and necroses and separates by a process of dry gangrene, which usually takes between 7–14 days. The main reasons behind prolonged separation include infection and the use of antiseptics, which reduce the number of normal non-pathogenic flora. Clinical trials continue in relation to best practice in cord care (Janssen et al 2003).

Downy hair, called lanugo, covers the skin and is plentiful over the shoulders, upper arms and thighs. The general colour of the skin depends on the baby’s ethnic origin, ranging from pink and white to olive or dark brown. Peripheral cyanosis is common and is usually of no significance. Pigmentation of nipples and genitalia is deeper in babies with darker skins and a linea nigra may be present. Another feature of racial origin is the Mongolian blue spot, which presents as a diffuse bluish-black area usually over the sacral region. Dark-skinned babies become more pigmented in the first weeks of life though the palms of the hands and soles of the feet remain paler than the rest of the body.

A mature baby has many skin creases on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. The nails are fully formed and adherent to the tips of the fingers, sometimes extending beyond the fingertips. The hair is soft and silky: some babies have virtually no hair, whereas others have a significant amount of straight or curly hair. The eyebrows and eyelashes present a similar variation. The cartilage of the ears is well formed.

Sebaceous glands, though present in the skin, are relatively inactive. Distended glands, milia, may be present over the nose and cheeks. Sweat glands are present but inactive in the first days of life. The vasoconstrictor mechanism is inefficient because the vascular plexuses are underdeveloped. The baby’s poor melanin production renders a vulnerability to sunburn.

Sensitivity to touch and pressure, heat and cold, and pain are mediated through the skin.

Temperature regulation

Thermal control in the neonate remains poor for some time. Initial thermal adaptation and modes of heat loss have been described in Chapter 39. Owing to the immaturity of the hypothalamus, temperature regulation is inefficient and the baby remains vulnerable to hypothermia particularly when exposed to cold or draughts, when wet, when unable to move about freely, or when deprived of nutrition. Cold babies are unable to shiver; therefore they attempt to maintain body heat by adopting a flexed fetal posture, increasing their respiratory rate and activity. These activities increase calorie consumption and may result in hypoglycaemia, which in turn will compound the effects of hypothermia, as do hypoxia, acidosis and hyperbilirubinaemia (see Chs 47 and 48).

The baby’s normal core temperature is 36.5–37.3 °C. A healthy, clothed, term baby will maintain this body temperature satisfactorily, provided the environmental temperature is sustained between 18 °C and 21 °C, nutrition is adequate and movements are not restricted by tight swaddling. However, like adults, babies are individuals with differing metabolic rates. This makes finite statements of thermoneutral range difficult (Hull et al 1996a, b). Hyperthermia can occur when the baby is exposed to a radiant heat source. Sweating may occur, especially over the forehead, although the neonate’s ability to sweat is limited. An unstable temperature may indicate infection.

Respiratory system

At birth, the respiratory system is developmentally incomplete, growth of new alveoli continuing for several years. The lumen of the peripheral airways is narrow, which predisposes to atelectasis. Respiratory secretions are more plentiful than in an adult and the mucous membranes are delicate and sensitive to trauma, the area below the vocal cords being particularly prone to oedema (see also Ch. 39).

The normal baby has a respiratory rate of 40–60 breaths/min, and breathing is diaphragmatic, chest and abdomen rising and falling synchronously. The breathing pattern is erratic. Respirations are shallow and irregular, being interspersed with brief 10–15 s periods of apnoea (Perry 2002). This is known as periodic breathing. Apart from the initial profound respiratory efforts at birth, no nasal flaring, sternal or subcostal recession or grunting is present. The pattern of respiration alters during sleeping and waking states. Babies are obligatory nose breathers and do not convert automatically to mouth breathing when nasal obstruction occurs. Respiratory difficulties can occur because of neurological, metabolic, circulatory or thermoregulatory dysfunction as well as infection, airway obstruction or abnormalities of the respiratory tract itself.

Babies have a lusty cry, which evokes an immediate response from carers. The cry is normally loud and of medium pitch unless neurological damage, infection or hypothermia is present, when it may be high pitched or weak. Transient cyanosis may arise in the first few days when the baby is crying and altered pressure gradients recreate right-to-left shunts within the heart and great vessels. This is of no clinical significance (see Ch. 39).

Cardiovascular system and blood

The changes in the baby’s heart at birth have been described in Chapter 39. The heart rate is rapid; 110–160 beats/min (b.p.m.) and fluctuates in accordance with the baby’s respiratory function and activity or sleep state. Peripheral circulation is sluggish. This results in mild cyanosis of hands, feet and circumoral areas and in generalized mottling when the skin is exposed. Blood pressure fluctuates according to activity and ranges from 50–55/25–30 mmHg to 80/50 mmHg in the first 10 days of life (Roberton 1996). It is considered that, even at rest, the baby’s heart probably functions at full capacity, rendering the baby vulnerable to additional stress (Blackburn 2007).

The total circulating blood volume at birth is 80 mL/kg body weight. However, this may be raised if there is delay in clamping the umbilical cord at birth. The haemoglobin level is high (13–20 g/dL), of which 50–85% is fetal haemoglobin (Blackburn 2007). Conversion from fetal to adult haemoglobin, which commenced in utero, is completed in the first 1–2 years of life. Haemoglobin, red cell count (5–7 × 1012/L) and haematocrit (55%) levels decrease gradually during the first 2–3 months of life, during which time erythropoiesis is suppressed. The white cell count is high initially (18.0 × 109/L) but decreases rapidly (Perry 2002, Roberton 2005).

Breakdown of excess red blood cells in the liver and spleen predisposes to jaundice in the first week. Because colonization of the intestine by the bacteria, which synthesize vitamin K, is delayed until feeding is established, vitamin-K-dependent clotting factors II (prothrombin), VII, IX and X are low. This inhibits blood clotting during the first week. Platelet levels equal those of the adult, but there is a reduced capacity for adhesion and aggregation (Blackburn 2007).

Renal system

Though the kidneys are functional in fetal life, their workload is minimal until after birth. They are functionally immature. The glomerular filtration rate is low and tubular reabsorption capabilities are limited. The baby is not able to concentrate or dilute urine very well in response to variations in fluid intake, nor compensate for high or low levels of solutes in the blood. This results in a narrow margin between homeostasis and fluid imbalance (see Ch. 48). The ability to excrete drugs is also limited and the baby’s renal function is vulnerable to physiological stress (Blackburn 2007, Perry 2002, Roberton 2005). The first urine is passed at birth or within the first 24 hrs and thereafter with increasing frequency as fluid intake rises. The urine is dilute, straw coloured and odourless. Cloudiness caused by mucus and urates may be present initially until fluid intake increases. Urates may cause pink staining, which is insignificant. As the neonatal pelvis is small, the bladder becomes palpable abdominally when full. It is the midwife’s responsibility to observe and record the baby’s urinary output.

Gastrointestinal system

The gastrointestinal tract of the neonate is structurally complete, although functionally immature in comparison with that of the adult (Blackburn 2007, Perry 2002, Roberton 2005). The mucous membrane of the mouth is pink and moist. The teeth are buried in the gums and ptyalin secretion is low. Small epithelial pearls are sometimes present at the junction of the hard and soft palates. Sucking pads in the cheeks give them a full appearance. Sucking and swallowing reflexes are coordinated.

The stomach has a small capacity (15–30 mL), which increases rapidly in the first weeks of life. The cardiac sphincter is weak, predisposing to regurgitation or posseting. Gastric acidity, equal to that of the adult within a few hours after birth, diminishes rapidly within the first few days and by the 10th day, the baby is virtually achlorhydric, which increases the risk of infection. Gastric emptying time is normally 2–3 hrs.

In relation to the size of the baby, the intestine is long, containing large numbers of secretory glands and a large surface area for the absorption of nutrients. Enzymes are present, although there is a deficiency of amylase and lipase, which diminishes the baby’s ability to digest compound carbohydrates and fat. When food enters the stomach, a gastrocolic reflex results in the opening of the ileocaecal valve. The contents of the ileum pass into the large intestine and rapid peristalsis means that feeding is often accompanied by reflex emptying of the bowel.

The gut is sterile at birth but is colonized within a few hours. Bowel sounds are present within 1 hr of birth. Meconium, present in the large intestine from 16 weeks’ gestation, is passed within the first 24 hrs of life and is totally excreted within 48–72 hrs. This first stool is blackish-green in colour, is tenacious and contains bile, fatty acids, mucus and epithelial cells. From the 3rd–5th day the stools undergo a transitional stage and are brownish-yellow in colour. Once feeding is established, yellow faeces are passed. The consistency and frequency of stools reflect the type of feeding. Breastmilk results in loose, bright yellow and inoffensive acid stools. The baby may pass 8–10 stools a day, or pass stools as infrequently as every 2 or 3 days. The stools of the bottle-fed baby are paler in colour, semiformed, less acidic and have a slightly sharp smell (Roberton 2005).

Physiological immaturity of the liver results in low production of glucuronyl transferase for the conjugation of bilirubin. This, together with a high level of red cell breakdown, and stimulation of hepatic blood flow may result in a transient jaundice, which is manifest on the 3rd–5th days (see also Ch. 47). Glycogen stores are rapidly depleted, so early feeding is required to maintain normal blood glucose levels (2.6–4.4 mmol/L). Feeding stimulates liver function and colonization of the gut, which assists in the formation of vitamin K.

Infant-feeding practices are designed to meet the physiological needs and capabilities of the baby and are discussed in Chapter 41.

Immunological adaptations

Neonates demonstrate a marked susceptibility to infections, particularly those gaining entry through the mucosa of the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems. Localization of infection is poor, ‘minor’ infections having the potential to become generalized very easily.

The baby has some immunoglobulins at birth but the sheltered intrauterine existence limits the need for learned immune responses to specific antigens (Blackburn 2007, Crockett 1995, Perry 2002, Stern 1999). There are three main immunoglobulins, IgG, IgA and IgM, and of these only IgG is small enough to cross the placental barrier. It affords immunity to specific viral infections. At birth, the baby’s levels of IgG are equal to or slightly higher than those of the mother. This provides passive immunity during the first few months of life. IgM and IgA do not cross the placental barrier but can be manufactured by the fetus. Levels of IgM at term are 20% those of the adult, taking 2 years to attain adult levels (elevation of IgM levels at birth is suggestive of intrauterine infection). This relatively low level of IgM is thought to render the baby more susceptible to enteric infections. IgA levels are very low and increase slowly, although secretory salivary levels attain adult values within 2 months. IgA protects against infection of the respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract and eyes. Breastmilk, and especially colostrum, provides the baby with passive immunity in the form of Lactobacillus bifidus, lactoferrin, lysozyme and secretory IgA among others (see Ch. 41).

The thymus gland, where lymphocytes are produced, is relatively large at birth and continues to grow until 8 years of age.

Reproductive system: genitalia and breasts

In boys, the testes are descended into the scrotum, which has plentiful rugae; the urethral meatus opens at the tip of the penis and the prepuce is adherent to the glans. In girls born at term, the labia majora normally cover the labia minora; the hymen and clitoris may appear disproportionately large. Spermatogenesis in boys does not occur until puberty, but the total complement of primordial follicles containing primitive ova is present in the ovaries of girls at birth. In both sexes, withdrawal of maternal oestrogens results in breast engorgement, sometimes accompanied by secretion of ‘milk’ by the 4th or 5th day. Baby girls may develop pseudomenstruation for the same reason. Both boys and girls have a nodule of breast tissue around the nipple. Midwives should have the knowledge to reassure and explain the physiological nature of these events to the parents.

Skeletomuscular system

The muscles are complete, subsequent growth occurring by hypertrophy rather than by hyperplasia. The long bones are incompletely ossified to facilitate growth at the epiphyses. The bones of the vault of the skull also reveal lack of ossification. This is essential for growth of the brain and facilitating moulding during labour. Moulding is resolved within a few days of birth. The posterior fontanelle closes at 6–8 weeks. The anterior fontanelle remains open until 18 months of age, making assessment of hydration and intracranial pressure possible by palpation of fontanelle tension.

Psychology and perception

Newborn babies at birth are alert and aware of their surroundings and they have long periods (60%) of ‘quiet alert state’ (Saigal et al 1981). Far from being impassive, they react to stimuli and begin at a very early age to amass information; they are especially interested in the faces of their mother and father, the sound of their voices and their smell and touch (Brazelton & Nugent 1995).

Senses

Vision

Though immature, the structures necessary for vision are present and functional at birth. Babies are sensitive to bright lights, which cause them to frown or blink. They demonstrate a preference for bold black and white patterns and the shape of the human face, focusing at a distance of approximately 15–20 cm. This gives babies the ability to establish eye contact with their mother while being nursed and so enhance the bonding process. They can track a moving object briefly within the first 5 days, and by 2 weeks of age can differentiate their mother’s face from that of a stranger. Interest in colour, variety and complexity of patterns develops within the first 2 months of life (Blackburn 2007, Perry 2002, Roberton 2005). The shape of the baby’s eyes may reflect racial origin; for instance the epicanthic folds of Oriental babies alter the appearance of the orbital region. No tears are present in the eyes of the newborn, therefore they become infected easily.

Hearing

Newborn babies’ eyes turn towards sound. On hearing a high-pitched sound, they first blink or startle and then become agitated, and are comforted by low-pitched sounds. They prefer the sound of the human voice to other sounds and within a few weeks the patterns of adult speech are mimicked by reactive movements. Newborn babies can discriminate between voices, giving preference to their mother’s (DeCasper & Fifer 1987). This, too, promotes mother–baby interaction. Neonatal hearing screening is performed on all babies prior to discharge from hospital. The aim of the screening is to identify early and follow-up babies with moderate, severe or profound bilateral permanent hearing impairment (NHS Screening 2006).

Smell and taste

Babies prefer the smell of milk to that of other substances and show a preference for human milk. They prefer the smell of an unwashed breast to that of a washed one (Righard 1995). They turn away from unpleasant smells and show preference for sweet taste, as is demonstrated by vigorous and sustained sucking and a speedy grimacing response to bitter, salty or sour substances (Blackburn 2007).

Touch

Babies are acutely sensitive to touch, enjoying skin-to-skin contact, immersion in water, stroking, cuddling and rocking movements (Blackburn 2007, Perry 2002). A puff of air on the face induces an inspiration or gasp reflex. The grasp reflex enhances the relationship with the mother. Facial coding of pain in babies is expressed by brow bulging, eyelid squeezing, nasolabial furrowing and open-lipped crying (Grunau et al 1998, Rushforth & Levene 1994).

Sleeping and waking

Following the initiation of respiration at birth, the baby remains alert and reactive for a period of approximately 1 hr, and then relaxes and sleeps. The length of this first sleep varies from a few minutes to several hours and is followed by a second period of reactivity, during which mucus accumulation in the oropharynx may occur, causing choking or gagging (Perry 2002). Subsequent sleeping and waking rhythms show marked variations and the baby takes some time to settle into an individual pattern. Initially, waking periods are related to hunger, but within a few weeks, the waking periods last longer and meet the need for social interaction.

Sleep states

Wakeful states

A wider range of awake states is observed, ranging from drowsiness to crying:

Crying

The crying repertoire of babies distinguishes different needs and is the way in which they communicate discomfort and summon assistance. With experience, it is possible to differentiate the cry and identify the need, which may be hunger, thirst, pain, general discomfort (e.g. wanting a change of position or feeling too cold or too hot), boredom, loneliness or a desire for physical and social contact. Maternal anxiety and difficulties related to baby crying can be allayed by information and advice from the midwife. Infant massage helps enhance parent–infant bonding and warm, positive relationships; it can also reduce distress, sleep problems and can leave the baby feeling safe and comfortable (Field 2004).

Growth and development

Babies, because of their physiological limitations, are dependent on their mothers (or other caregiver) for continued survival, growth and development. These will progress satisfactorily only if the baby is physiologically and neurologically normal, is in a safe environment, nutritional needs are met, and psychological development is promoted by appropriate stimulation and loving care. Abnormality of the baby’s body systems, inadequate nutrition or emotional deprivation will compromise the baby’s ability to grow and develop to full potential (Fry 1994). The relatively immature organ functions and the vulnerability to infection and hypothermia demand that care must be designed to meet needs and capabilities.

All babies are developmentally assessed at birth and the results documented to provide a baseline for future developmental assessments.

Examination at birth

Identification and security procedures

In hospital, the midwife receiving the baby from the labour suite staff should verify that the baby’s name, sex, date and time of birth on the two name-bands match the information in the case notes and are entered on to the cot card. The name-bands should remain on the baby until discharge from hospital. It is recommended that the presence of two legible, matching, correct name-bands is verified daily, on transfer to other wards and on discharge from hospital. If the information becomes illegible, or a name-band is lost, new name-band(s) should be prepared, verified with the mother and replaced in her presence. The replacement of the name-bands should be documented in the case notes. In the event of a baby being found without any name-bands, the midwife must notify the unit manager and comply with local policy and procedures for their replacement. No mother should ever be in any doubt about her baby’s identity (Laurent 1992).

Abduction of babies from hospitals has led to the development of security tagging and other monitoring devices, e.g. CCTV (Day 1995). It is advisable that the mother accompanies her baby at all times and she should be able to identify members of staff who are involved in her baby’s care. Staff must be aware of the movement of babies and mothers in their care.

Detailed observation

All newborn babies should have a quick overall examination performed in the labour suite as soon as possible after birth to ascertain that, externally at least, the baby is normal, and to assess adaptation to normal extrauterine life. During these first few hours after birth, the midwife should observe the baby frequently for any colour changes, patency of airway and haemorrhage from the umbilical cord. Temperature should also be monitored to ensure that it is maintained within the normal range. Before commencing the initial examination of the baby, the midwife should ensure that the environment is warm and draught-free. Diligent hand-washing is essential.

The face, head and neck

After a general observation of the face, the midwife should inspect the eyes and mouth of the baby. Each eye should be visualized to confirm that it is present and that the lens is clear. The eyes open spontaneously if the baby is held in an upright position. Any slight oedema or bruising is noted but may be insignificant. The normal space between the eyes is up to 3 cm.

The mouth

The mouth can be opened easily by pressing against the angle of the jaw. This allows visual inspection of the tongue, gums and palate. The palate should be high arched, intact and the uvula central. Epithelial pearls (Epstein’s pearls) may be observed. They occur as a cluster of several white spots in the mouth at the junction of the soft and hard palate in the midline. Less commonly, they occur in the alveolar margin or on the prepuce. They are of no significance, but occasionally are mistaken for infection, and they disappear spontaneously. The midwife uses her little finger to feel the palate for any submucous cleft. A normal baby will respond by sucking the finger. Precocious teeth may protrude through the central part of the lower gum. Though usually covered by epithelial tissue, such teeth may have erupted and be loose, requiring extraction in the early neonatal period to prevent their inhalation. A tight frenulum will give the appearance of tongue-tie: no treatment is necessary for this.

The ears

These are inspected, noting their position. The upper notch of the pinna should be level with the canthus of the eye. Patency of the external auditory meatus is verified. Accessory auricles (small tags of tissue) are sometimes noted lying in front of the ear. Ear abnormalities can be associated with chromosomal anomalies and syndromes, and should be reported to a paediatrician.

The head and neck bones

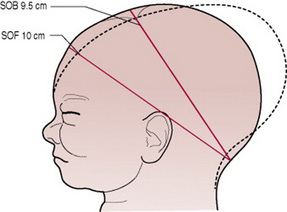

By palpating the vault of the skull, the midwife can determine the degree of moulding by the amount of overriding of the bones at the sutures and fontanelles. The bones should feel hard in a term baby. A wide anterior fontanelle and splayed sutures may indicate hydrocephalus or immaturity. The shape of the baby’s head as a result of moulding gives an indication of the presentation in utero (Fig. 40.1). An oedematous swelling, caput succedaneum, may be noted overlying the presenting part. This is a result of pressure from the cervical os and will disappear spontaneously within 24 hrs. Parents can be reassured that moulding usually resolves within a few days after birth.

Figure 40.1 Type of moulding in a vertex presentation (SOB, suboccipitobregmatic; SOF, suboccipitofrontal).

The short thick neck of the baby must be examined to exclude the presence of swellings and to ensure that rotation and flexion of the head are possible.

The chest and abdomen

Observation of respiratory movement should reveal that chest and abdominal movements are synchronous. The respirations may still be irregular at this stage. The space between the nipples should be noted; widely spaced nipples being associated with chromosomal abnormality.

The shape of the abdomen should be rounded. The midwife notes any variation, including a scaphoid (boat-shaped) abdomen (which may indicate a malnourished fetus or diaphragmatic hernia, see Ch. 46) or any protrusions, particularly at the base of the umbilical cord.

The artery forceps securing the umbilical cord should be replaced by a plastic disposable clamp, or elastic bands (according to hospital policy) applied approximately 2 cm from the umbilicus. Excess cord is discarded.

Haemostasis of the umbilical cord is vital. A blood loss of 30 mL from a baby is equivalent to almost half a litre of blood from an adult. Prophylactic Vitamin K 1 mg can be given orally or intramuscularly to promote prothrombin formation (Jørgensen et al 1991, Shearer 1995). Midwives must be aware of their local hospital policy regarding consent and administration of Vitamin K (see Ch. 45).

Normally three cord vessels are present. Absence of one of the arteries is occasionally associated with renal anomalies and must be reported to the paediatrician.

The genitalia and anus

The genitalia should be examined carefully. If the sex is uncertain, the paediatrician will initiate investigations. Depending on local policy, the baby’s temperature may be taken rectally to detect any excessive cooling and to confirm patency of the anus. This method is less commonly used today. The preferred methods are via the axilla (under the arm), tympanic (ear), or in the groin. The normal baby’s skin temperature should range from 36.5 °C to 37.3 °C.

The limbs and digits

In addition to noting length and movement of the limbs, it is essential that the digits are counted and separated to ensure that webbing is not present. The hands should be opened fully as any accessory digits may be concealed in the clenched fist. The feet are examined for any deformity such as talipes equinovarus, as well as looking for extra digits. The axillae, elbows, groins and popliteal spaces should also be examined for abnormalities. Normal flexion and rotation of the wrist and ankle joints should be confirmed.

The spine

With the baby lying prone, the midwife should inspect and palpate the baby’s back. Any swellings, dimples or hairy patches may signify an occult spinal defect. (All abnormalities must be reported to a paediatrician.)

Measurements

The baby’s head circumference, length and weight are measured to provide parameters against which future growth can be monitored. The head circumference is measured, encircling it at the occipital protuberance and the supraorbital ridges with a measuring tape. Moulding may reduce this measurement and for this reason, this estimate is sometimes delayed until the 3rd day when the head shape has resumed its normal contours.

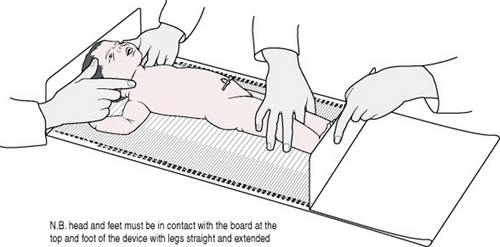

Accurate measurement of the baby’s crown–heel length is extremely difficult; this can only be measured accurately using calibrated equipment (Fig.40.2). In circumstances where this is not available, only an approximation of length can be achieved. The midwife should comply with local policy and procedures in this regard.

When the baby is weighed and the identity bands are verified as correct, they are then attached one to the arm and one on the leg, although this may vary according to local hospital policy. The baby is then dressed and wrapped in warm blankets.

Documentation

The midwife records her findings in the baby’s case notes, and any abnormalities are brought to the attention of the paediatrician, or GP if a home birth and receiving midwife in the postnatal ward. Midwives must adhere to the guidelines for records and record-keeping (NMC 2007).

Daily examination and care

Each day, the baby should be examined by a midwife, to evaluate progress and identify problems as they arise. The examination is similar to that undertaken at birth but is now concerned with monitoring daily changes with the baby.

In caring for the normal baby, the midwife should ensure that the baby is comfortable, is feeding well and that facilities are available for the parents to help them with the attachment process. It is also important that midwives are aware of the signs of airway obstruction, infection, jaundice and hypothermia. They should report any deviation from the normal to the paediatrician.

Prevention of airway obstruction

Babies are obligatory nose breathers; patency can be assessed by watching the baby breathe in a quiet state. If one nostril is blocked, occlusion of the other results in cyanosis with unsuccessful attempts to breathe through the mouth. Bilateral nasal obstruction is of major significance if due to bilateral choanal atresia, which is a major medical emergency. Observe the colour of the baby’s skin and mucous membranes. In the normal baby, the lips and mucous membranes are pink and well perfused.

Choking can occur during feeding if coordination is poor, and also following vomiting or regurgitation of mucus or feed. Suction apparatus should be readily available, so that aspiration of the baby’s airway can be carried out effectively and quickly in an emergency situation.

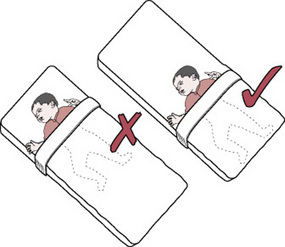

According to guidelines it is important for a baby to sleep in the supine position (on its back) with the feet at the foot of the cot (Fig. 40.3) (Lerner 1993).

Prevention of infection

The baby’s skin is a barrier to infection provided its integrity and pH balance are maintained. Babies should be provided with their own equipment. Adequate linen supplies are essential. This is especially important in hospital. The number of people handling the baby should be restricted. Members of staff who are liable to be a source of infection should not handle babies, and friends and relatives who have colds or sore throats (especially children) should not visit. Parents should be taught the proper technique for hand-washing and instructed that hand-washing before and after handling babies is essential. Cross-infection can be a particular problem in hospitals and most hospitals now have a hand sanitizing agent at every bedside. For this reason rooming-in and keeping the baby with the mother is highly recommended. The wearing of gowns for parents when handling babies is not necessary.

A newborn baby usually sleeps for most of the time between feeds but should be alert and responsive when awake. Erratic sleep patterns may prove disconcerting to new parents and they should be reassured by the midwife that this can be normal if the baby looks healthy, is alert and is feeding well. Undue lethargy or irritability may indicate cerebral damage or infection.

Prevention of hypothermia

Overexposure of the baby should be avoided to prevent heat loss. Where possible, the room temperature should be maintained at 18–21 °C. In hospital, and where higher ambient temperatures are able to be maintained, the baby should be dressed in a cotton gown or sleep suit and covered by two cellular blankets. An additional blanket underneath the bottom sheet will provide extra warmth for babies who are having difficulty in maintaining a stable body temperature. At home, or in cold environments, extra blankets may be required. Bath water should be warm (36 °C) and wet clothing should be changed as soon as possible. It is essential also to avoid overheating (Bacon 1991, Rutter 2005, Thomas 1994). Advice regarding clothing and bedding can only be a guide, as babies have marked individual variations in their metabolic rates (Hull et al 1996a). Parents should be advised to take account of environmental temperature when dressing their baby. Swaddling should be loose enough to permit movement of arms and legs, allowing adjustment to posture in response to the need for a change in temperature (Hull et al 1996b).

Baby cleansing

The timing of the first bath is not critical, although it has been suggested that removal of blood and liquor reduces the risk of transmission of HIV and other organisms to staff (Penny-MacGillivray 1996). Bathing should be deferred until the baby’s temperature is above 36.5 °C. The temperature of the bath water should be 36 °C. The hair is washed and dried carefully at the first bath but need not be washed daily. If the baby has been regurgitating mucus, a thin layer of petroleum jelly may be applied to the cheek to prevent soreness. Petroleum jelly applied to the buttocks will prevent meconium adhering to the skin and causing excoriation.

Daily bathing is not essential but the mother should be given sufficient opportunities to bath her baby in order to increase her confidence. ‘Topping and tailing’ (cleansing the baby’s face, skin flexures and napkin area only) may be carried out once or twice a day. It should be noted that greater heat loss may be incurred during this procedure than when the baby is bathed (Perry 2002).

Cleanliness of the umbilical cord is essential. The umbilical cord base is inspected for redness and the mother is instructed about cord care. Hand-washing is required before and after handling the cord. No specific cord treatment is required, although a wide variety of preparations have been used to promote early separation. However, it should be noted that topical applications could interfere with the normal process of colonization and delay separation. Cleansing with tap water and keeping the cord dry have been shown to promote separation (Barclay et al 1994, Trotter 2003). It is advisable to ensure that the cord is not enclosed within the baby’s napkin where contamination by urine or faeces may occur. The cord clamp may be removed on the 3rd day provided the cord is dry and necrosed (WHO 1999). In some Maternity Units, the cord clamp is routinely left in situ because it is thought to help separation due to the added weight (Trotter 2003).

The baby’s eyes do not need to be cleansed unless a discharge is present. Sticky eyes are cleaned with sterile water after obtaining a swab for culture and sensitivity testing. The mouth should be clean and moist. Adherent white plaques indicate oral thrush infection. Sucking blisters on the baby’s lips may be observed, especially after feeding. These do not require any treatment.

General observation of skin

The skin, between the digits, is inspected for rashes, septic spots, excoriation or abrasions. Skin rashes such as erythema toxicum, a red blotchy rash, are of little significance. Sometimes a harlequin colour change may be noted; this is a very rare but dramatic colour change, with vivid midline demarcation of colour. The baby is red on one side of the trunk and pale on the other side. This is caused by vasomotor instability and is of little importance. However, its appearance is startling and can alarm the mother, so reassurance should be given by the midwife.

Attention should be paid to the washing and drying of skin flexures to prevent excoriation. Promotion of skin integrity is enhanced by avoiding friction against hard fabrics or soiled or wet clothing, and by minimizing the length of time the skin is in contact with irritants, such as gastric contents, urine and stool. Cleansing of the skin should be carried out gently to prevent damage to the epidermis. Skin care preparations should be used with caution to prevent irritation and disturbance of the skin. Research has suggested that the usage of baby products is superfluous to the care of the baby’s skin (Trotter 2004). The use of biological powders, fabric softeners and starch should be avoided when laundering babies’ clothing (Michie 1996).

All neonates have a transient rise in bilirubin, and some become visibly jaundiced. Babies who become jaundiced in the first 24 hrs of life or who have significant jaundice within 48 hrs need investigation. If a baby remains jaundiced on discharge from hospital, the midwife must contact the community midwife to monitor levels of bilirubin and instruct the parent to report to their GP if the baby’s stools become pale or if the urine becomes dark, which may be suggestive of biliary atresia (see Ch. 47).

The fingertips and toes are examined for ragged nails and paronychia. Septic spots must be differentiated from milia, which do not require treatment. Even a few septic spots must be taken seriously. The paediatrician may prescribe topical applications or systemic antibiotics and consider possible isolation of the baby.

In some areas, the baby’s temperature is recorded with a low-recording thermometer. This may be taken in the axilla, ear, in the groin or rectally. If the rectal route is used it is essential that the baby’s legs and the thermometer are held firmly to prevent sudden movement, which could cause the thermometer to break and perforate the rectum. The midwife should ensure that the bulb of the thermometer is inserted no further than 2.5 cm into the rectum. Concern regarding the risk of injury has led to an increased use of alternative methods of measuring babies’ temperatures. This concern must be balanced against the need for an accurate estimate of core temperature when babies are ill (Morley 1992). Midwives should comply with local policy in regard to rectal temperature taking.

Newborn babies’ stools are observed for changes in relation to the baby’s age and the type of milk ingested (Ch. 41). Non-passage of stools or vomiting helps to identify abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract, inborn errors of metabolism and infection. Constipation may be alleviated by offering the baby water between feeds. Loose, watery stools may signify sugar intolerance or infection and may cause sore buttocks. Sore buttocks may be treated by exposure to the air, but care must be taken to avoid chilling the baby. The frequency of passing urine and stools in the preceding 24 hrs should be noted and recorded by the midwife.

At feed time, the midwife should observe the baby’s eagerness or reluctance to feed and the coordination of sucking and swallowing reflexes, as well as noting the frequency with which the baby demands feeds. During feeding, babies clench their fists, tuck them under the chin and wriggle their toes while grasping their mother’s fingers. Eye contact also occurs, which enhances communication between mother and baby. Sucking is interspersed with rest periods. Abnormal feeding behaviour may signify cerebral damage, congenital abnormality or illness. Breast engorgement and pseudomenstruation require no treatment but explanation to the mother is essential. No attempt should be made to express engorged breasts.

If the baby is to be weighed, this is done before dressing, and the result compared with his birth weight. Weight loss is normal in the first few days but more than 10% body weight loss is abnormal and requires investigation. Most babies regain their birth weight in 7–10 days, thereafter gaining weight at a rate of 150–200 g per week.

It is important for the midwife to note responses to handling and noise as she undresses the baby. She can use this time to inspect the identity bands, and have a discussion with the mother about feeding or any other concerns that she may have.

All findings at the daily examination are entered in the baby’s records and abnormalities reported to the paediatrician.

Advice to mother

A baby should not be left unattended at any time, especially not on the bed as vigorous activity may result in injury from a fall. When a baby needs transporting from one area to another it should be placed in a cot and not carried in the carer’s or parent’s arms. The cot design should comply with safety standards and have a tight fitting mattress. Babies do not require a pillow until the age of 2 years and mothers should be advised that placing a pillow behind the baby’s head is unsafe. Similarly, polythene bags or sheeting should not be used near a baby and waterproof mattress covers must be tight fitting and enclose the mattress completely to prevent suffocation of the baby by a loose cover.

If safety pins are used to secure the napkin, they should be inserted into the cloth from side-to-side (not vertically) and with one hand protecting the baby’s abdomen to avoid penetration of the skin or genitalia. Cotton mittens should be worn to prevent facial scratches.

Advice and information leaflets about safety in the home and reducing the risk of cot death should be given and discussed with parents. Safety in the home should address such issues as use of cat-nets, fireguards, cooker guards, stair gates, pram brakes and car seats. Reducing the risk of cot death concentrates on smoking, back to sleep, feet-to-foot and advice on the importance of seeking early medical advice if the baby becomes unwell.

Discharge examination by the doctor/midwife

All newborn babies should be examined by one of the following: paediatrician, obstetrician, general practitioner, advanced neonatal nurse practitioner or midwife with appropriate training, within the first 72 hrs of life (NICE 2006). Moss et al (1991) believe that a second examination is of little value, apart from a repeat examination of the hips. The mother should be present for the examination. Some of the examination duplicates what has been described above and so only the medical aspects are considered here.

A general appraisal of the baby’s colour, overall appearance, muscular activity and response to handling is made throughout the examination.

Head assessment

To start this assessment, the occipital frontal circumference (OFC) is measured using a non-stretchable tape measure. The average OFC in a term baby is 34–38 cm. Next, the size and tension of the anterior fontanelle is checked and suture lines palpated noting cranial moulding, caput succedaneum and cephalhaematoma. Any abnormality detected should be reported to a senior paediatrician and documented in the baby’s case notes. Parents should be reassured that moulding, caput and cephalhaematoma usually resolve within a few weeks after birth.

Examination of the face should begin with observing the relationships between all the facial components: eyes, ears, nose and mouth, remembering that unusual facial characteristics may be familial (Boyer Johnson 1996). A general inspection of the eyes for conjunctivitis, cataracts, aniridia and coloboma is carried out before using an ophthalmoscope. The ophthalmoscope is held in the right hand, with the viewing aperture as close as possible to the right eye, and using the right index finger to turn the lens selector dial to the appropriate lens for proper focus (Honeyfield 1996). While positioning the baby’s head with the free hand, the illuminating light is aligned along the baby’s visual plane, observing for the red reflex and pupil reaction. Parents will need reassurance about common eye trauma such as bruising or oedema of the eyelids and haemorrhage seen around the iris (Boyer Johnson 1996). These can occur after a normal vaginal birth and usually resolve within 1–2 weeks. The ears should be assessed for size, shape and placement; abnormal formation or placement can be associated with chromosomal anomalies and syndromes. The nose should be symmetric and placed vertically in the midline. Its size and shape may be familial (Boyer Johnson 1996).

To examine the mouth a gloved finger should be inserted into the baby’s mouth with the fingerpad up, to ensure continuity of the hard and soft palates and to assess suck and gag reflexes. Small white clusters of Epstein’s pearls may be seen at the junction of the hard and soft palate and on the gums (Boyer Johnson 1996); these should not be mistaken for the white plaque of oral thrush.

Cardio/respiratory assessment

After inspection of the baby’s colour, the next step is to auscultate the heart sounds. It is necessary to have a paediatric stethoscope with a double-headed chest piece; both sides are necessary to listen to the heart. The stethoscope should be placed firmly on bare skin, to assess the heart rate and evaluate cardiac rhythm and regularity (Honeyfield 1996). The practitioner carefully listens to the rhythm of the heart to determine whether there is any irregularity; a note is made of patterns and frequencies of the irregularity, which help identify the type of arrhythmia (Fraser Askin 1996). Murmurs are described as additional heart sounds and must be discussed and reported to a senior paediatrician.

To assess the chest and lungs, the shape of the chest is noted, and the rate and regularity of the respirations. Normal respirations are 40–60/min and relaxed, symmetrical diaphragmatic respirations are normal. Breath sounds can now be assessed using a stethoscope; sounds are louder and coarser in the baby than in the adult. Breath sounds should be assessed for pitch, intensity and duration. The practitioner begins at the top of the chest and moves the stethoscope systematically from side-to-side. Breath sounds in the lower lobes can be assessed adequately only through the baby’s back (Fraser Askin 1996). Any irregularities detected must be reported to the paediatrician.

Abdomen

This assessment requires inspection, palpation and auscultation. The practitioner palpates the abdomen with warm hands and observes for pain responses, starting at the groin by placing the index finger just above the groin parallel to the right costal margin and, with a gentle compressing motion, gradually moving the finger upward until the liver edge is felt. The normal liver is smooth and firm with a sharp and well-defined edge, and is felt 1–2 cm below the right costal margin. The spleen is normally not palpable unless infection is present. Next the kidneys and bladder are examined. The bladder when full is easily palpated 1–4 cm above the symphysis pubis, and can be associated with abnormalities if frequently or continuously distended. The kidneys are sometimes difficult to palpate; the left kidney is more easily palpated than the right, unless the descending colon is filled with meconium. The kidney is palpated using a deep smooth firm pressure by placing one hand under the baby’s flank and pressing downward with the other. Next, the practitioner auscultates for bowel sounds; using a stethoscope to listen to all four abdominal quadrants, breath sounds are usually heard in the upper abdominal region. Bowel sounds are absent immediately after birth. With crying and sucking, the abdomen begins to fill with air, and bowel sounds become audible within the first 15 min after birth. The sounds have a metallic, tinkling quality and are usually heard every 15–20 s. (The above description follows that by Keels Conner 1996.)

Neurological system

The baby’s reflex responses are elicited in order to establish normality of the neurological system. These are tested while the baby is in a quiet alert state. Absent or weak responses may indicate immaturity, cerebral damage or abnormality.

In comparison with the other body systems, the nervous system is remarkably immature both anatomically and physiologically at birth. This results in predominantly brain stem and spinal reflex activity with minimal control by the cerebral cortex in the early months, though social interaction occurs early. After birth, brain growth is rapid, requiring constant and adequate supplies of oxygen and glucose. The immaturity of the brain renders it particularly vulnerable to hypoxia, biochemical imbalance, infection and haemorrhage. Temperature instability and uncoordinated muscle movement reflect the incomplete state of brain development and incomplete myelination of nerves.

The baby is equipped with a wide range of reflex activities, the presence of which at varying ages provides an indication of the normality and integrity of the neurological and skeletomuscular systems (Gandy 1999).

Moro reflex

This reflex occurs in response to a sudden stimulus. The baby is held supine, with the trunk and head supported from below. When the head and shoulders are suddenly allowed to fall back, the baby responds by abduction and extension of arms with fingers fanned, and sometimes accompanied by a tremor. The arms then flex and embrace the chest. A similar response may be seen in the legs which, following extension, flex on to the abdomen (Fig. 40.4). The Moro reflex is often accompanied by a cry and may be demonstrated unintentionally when briskly placing a baby in the supine position. Babies do not seem to like this reflex, so it should not be elicited as a routine procedure. The reflex is symmetrical and is present for the first 8 weeks of life. The most common cause of an asymmetric Moro response is a fracture of the humerus or clavicle, or a brachial plexus palsy. Absence of the Moro reflex may indicate brain damage or immaturity. Persistence of the reflex beyond the age of 6 months is suggestive of learning difficulties (Thomas & Harvey 1992).

Rooting reflex

In response to stroking of the cheek or side of the mouth the baby will turn towards the source of stimulus and open the mouth ready to suckle.

Sucking and swallowing reflexes

These are well developed in the normal baby and are coordinated with breathing. This is essential for safe feeding and adequate nutrition.

Grasp reflexes

A palmar grasp is elicited by placing a finger or pencil in the palm of the baby’s hand. The finger or pencil is grasped firmly. A similar response can be demonstrated by stroking the base of the toes (plantar grasp).

Walking and stepping reflexes

When supported upright with his feet touching a flat surface, the baby simulates walking. If held with the tibia in contact with the edge of a table, the baby will step up on to the table (limb placement reflex).

Asymmetrical tonic neck reflex

In the supine position the limbs on the side of the body to which the head is turned extend, while those on the opposite side flex. Muscle tone is reflected in the baby’s response to passive movements.

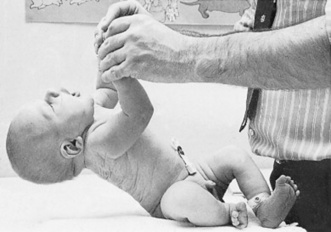

Traction response

When pulled upright by the wrists to a sitting position, the head will lag initially (Fig. 40.5) then right itself momentarily before falling forward on to the chest.

Ventral suspension

When held prone, and suspended over the examiner’s arm, the baby momentarily holds the head level with the body and flexes the limbs (Fig. 40.6).

These reflexes and responses are self-defence mechanisms, which are designed to attract the mother to her baby and so promote the mother–child attachment.

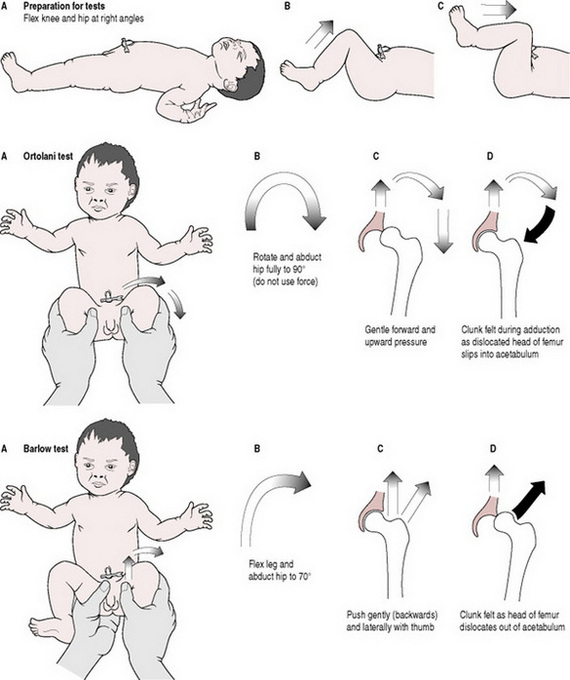

Examination of hips

It is essential that all babies undergo specific examination to detect developmental dysplasia of the hips (Aronsson et al 1994, Beverley & Nathan 1995). In some centres, the midwife performs this; in others the paediatrician is the person responsible. Care must be taken in order to avoid producing an iatrogenically unstable hip (Beverley & Nathan 1995). The examination should not be undertaken by inexperienced staff. To examine the hips the examiner must place the baby on a firm flat surface at waist height.

Ortolani’s test (Fig. 40.7)

The baby’s legs are grasped with the flexed knees in the palms of the examiner’s hands and the femur splinted between the index and middle fingers and the thumb. Both hips are examined simultaneously. The baby’s thighs are flexed on to the abdomen and rotated and abducted through an angle of 70–90° towards the examining surface. No force should be exerted. If the hip is dislocated a ‘clunk’ will be felt as the head of the femur slips into the acetabulum during adduction and the dislocation is reduced.

Barlow’s test

With the baby’s legs flexed (as above), the head of the femur is held between the examiner’s thumb and index finger while the other hand steadies the pelvis. Following the initial movement of flexion and rotation, as the hip is abducted to 70° gentle pressure is exerted in a backward and lateral direction. A ‘clunk’ will be felt as the head of the femur dislocates out of the acetabulum.

In some centres a modified Ortolani/Barlow procedure is followed. This incorporates the essential elements of both of the above manoeuvres (Hall et al 1994). Early referral to a paediatrician is essential if effective treatment for a dislocated, or dislocatable, hip is to be achieved (see Ch. 46).

Circumcision

Although not commonly practised in the UK, in other parts of the world neonatal circumcision may be undertaken while the baby is in hospital. There is little evidence to support this practice as beneficial; rather it is a traditional cultural custom (Gonik & Barrett 1995). It is recommended that appropriate anaesthesia, dorsal penile nerve block is used for this procedure and that postoperative analgesia is also prescribed (Rabinowitz & Hulbert 1995). After care involves the use of a non-adherent dressing, observing for haemorrhage and keeping the area clean and dry.

Blood tests

Certain inborn errors of metabolism and endocrine disorders are detected by means of a blood test, for example the Guthrie test. Blood, obtained from a heel prick made with a stilette on the lateral aspect of the heel to avoid nerves and blood vessels, is dripped on to circles on an absorbent card on to which full details of the baby’s identity and history are entered (see Plate 13). This is taken on day 4–6 after birth for detection of phenylketonuria, hypothyroidism and cystic fibrosis and if the baby is <35 weeks’ gestation, the sample is repeated when the baby reaches 36 weeks. If the baby has received a blood transfusion, the sample cannot be taken until 48 hrs post-transfusion and if for any reason the baby or mother is receiving antibiotics, this information should be recorded on the card. Some centres also test routinely for galactosaemia (see Ch. 48.)

The above examination, when completed, must be recorded in the Personal Child Health Record to inform the General Practitioner and Health Visitor.

Child health surveillance

The midwife will hand over care of the mother and baby on the 10th day but may continue to visit until day 28 or to the end of the puerperium to support the mother with, e.g. breastfeeding. Following discharge from the care of the midwife to that of the health visitor, the screening of the baby is continued on a regular basis at the child health clinic.

Vaccination and immunization

While the baby was developing in the uterus it received natural immunity IgG which affords immunity against specific viral infections. A comprehensive immunization programme is in place, which starts when the baby reaches 2 months of age and continues into childhood. Tuberculosis screening is now undertaken at birth and BCG vaccination if applicable will be offered to the baby during the early neonatal period. The date of the immunization, type of vaccine, batch number and injection site, should always be recorded in the baby’s record. Consent must be obtained from parents or legal guardian before a baby can receive any vaccinations.

Promoting family relationships

Parent–infant attachment

Positive responses from the baby to his parents reinforce parental attachment and stimulate further interaction. Knowledge of the reflexes, general abilities and sleep and awake states of babies enables the midwife to teach the parents how to take advantage of the occasions when their baby is likely to be most responsive. The resulting interactions continue the process of attachment initiated at birth (see Ch. 39). To help the mother in her new role, it is important to use the baby’s name and to speak positively about his/her appearance and activities.

Parents develop their relationship with their babies in individual ways and at their own pace. Some mothers feel somewhat distant from their baby at first; others experience an overwhelming protective urge and intense absorption with their baby (Jowitt 1996). It is important not to overemphasize ‘bonding’, as this may create non-productive guilt feelings in parents who do not experience instant love for their child and result in negative attitudes towards the baby (Barclay & Lupton 1999, Billings 1995, Rutter 1995).

It is suggested that the parents’ relationship with one another is enhanced when the father is encouraged to be involved in discussions, choices and decisions about baby care and to share the responsibility for care. The resultant maternal confidence is reflected in her responsiveness toward her baby, thus promoting the baby’s feeling of security (Adams & Cotgrove 1995). The father’s reactions to and feelings about his baby should be afforded expression (Heath 1995, McLennan 1995, Ratnaike 2007). Parents may express anxiety about the possible reactions of siblings to the new arrival. A positive attitude on the part of the midwife can do much to allay fears, which are often unfounded (Gullicks & Crase 1993).

Promoting confidence and competence

It is important that the midwife does not let her own maternal feelings ‘take over’, thus denying the mother opportunity to provide care for her baby. Involvement by the mother and father in the baby’s care should be encouraged by the midwife and as the parents gain confidence, they should take over total care of their baby. Teaching the principles and discussing individual care can help to overcome any anxieties the parents may be experiencing.

Promoting communication

The increasing interest in baby massage in recent years capitalizes on the knowledge that the baby is sensitive and responsive to touch (Barnett 2005, Lim 1996). Aromatherapy oils should not be used as the extent of their absorption is unknown. The naked baby is stroked and caressed in a leisurely manner using the fingertips and palms of the hands. Throughout this quiet time together, eye-to-eye contact is promoted by the close proximity of the baby, and the mother (or father) instinctively interacts with the baby’s pleasurable responses. This assists in reinforcing the developing emotional relationship.

By applying her knowledge of the physiological and psychological capabilities and potential complications of the newborn, the midwife can ensure that all care is given in a professional manner which will nurture and enhance a happy family relationship.

The foregoing discussions in this chapter have endeavoured to illustrate how the midwife can enhance the parent–baby relationship. Her teaching, support and encouragement of the mother as she learns to provide for her baby’s needs is of paramount importance and should culminate in a happy, confident and competent mother being discharged from the midwife’s care. The midwife can also do a great deal to encourage a father’s interaction with his baby and should take every opportunity to do so. These aspects of midwifery practice are described more fully in Chapters 34 and 36.

Adams L, Cotgrove A. Promoting secure attachment patterns in infancy and beyond. Professional Care of Mother and Child. 1995;5(6):158-160.

Aronsson DD, Goldberg MJ, Kling TF, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pediatrics. 1994;94(2):201-208.

Bacon CJ. The thermal environment of sleeping babies and possible dangers of overheating. In: David TJ, editor. Recent advances in paediatrics. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1991.

Barclay L, Lupton D. The experience of new fatherhood: a sociocultural analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;29(4):1013-1020.

Barclay L, Harrington A, Conroy R, Royal R, et al. A comparative study of neonates’ umbilical cord management. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1994;11(3):34-40.

Barnett L. Keep in touch: The importance of touch in infant development. Infant Observation. 2005;8(2):115-123.

Beverley M, Nathan S. Diagnosing developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). Maternal and Child Health. 1995;20(4):122-124.

Billings JR. Bonding theory – tying mothers in knots? A critical review of the application of a theory to nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 1995;4(4):207-211.

Blackburn ST. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal physiology: a clinical perspective, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier Science, 2007. Chs 8–15

Boyer Johnson C. Head, eyes, ears, nose, mouth and neck assessment. In Tappero EP, Honeyfield ME, editors: Physical assessment of the newborn, 2nd edn, California: NICU INK, 1996.

Brazelton TB. Neonatal behavioural assessment scale, 2nd edn. London: Spastics International Medical Publications, Blackwell Scientific, 1984.

Brazelton TB, Nugent JK. Neonatal behavioural assessment scale, 3rd edn. London: Mackeith Press, 1995.

Cetta F, Lambert GH, Ross SP. Newborn chemical exposure from over the counter skin-care products. Clinical Pediatrics. 1991;30:289. 289

Crockett M. Physiology of the neonatal immune system. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1995;24(7):627-634.

Day M. Babies at risk as maternity units fail to step up security. Nursing Times. 1995;91(28):6.

DeCasper A, Fifer W. Of human bonding: newborns prefer their mothers’ voices. In: Oates J, Sheldon S, editors. Cognitive development in infancy. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Open University, 1987.

Field T. Touch and massage in early childhood development. LLC USA: Johnson&Johnson Paediatric Institute, 2004.

Fraser Askin D. Chest and lungs assessment. In Tappero EP, Honeyfield ME, editors: Physical assessment of the newborn, 2nd edn, California: NICU INK, 1996.

Fry T. Monitoring children’s growth: introducing the new child growth standards. Professional Care of Mother and Child. 1994;4(8):231-233.

Gandy GM. Examination of the neonate including gestational age assessment. In Roberton NRC, editor: Textbook of neonatology, 3rd edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999. Ch. 17

Gonik B, Barrett K. The persistence of newborn circumcision: an American perspective. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1995;102(12):940-941.

Grunau R, Oberlander T, Holsti L, et al. Bedside application of the neonatal facial coding system in pain assessment of premature neonates. Pain. 1998;76:277-286.

Gullicks JN, Crase SJ. Sibling behaviour with a newborn: parents’ expectations and observations. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1993;22(5):438-444.

Hall D, Hill P, Elliman D. The child surveillance handbook, 2nd edn. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 1994.

Heath T. New fatherhood. New Generation. 1995;June:11.

Honeyfield ME. Principles of physical assessment. In Tappero EP, Honeyfield ME, editors: Physical assessment of the newborn, 2nd edn, California: NICU INK, 1996.

Hull D, McArthur AJ, Pritchard K, et al. Metabolic rate of sleeping infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1996;75(4):282-287.

Hull D, McArthur AJ, Pritchard K, et al. Individual variation in sleeping metabolic rates in infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1996;75(4):288-291.

Irving V. Caring for and protecting the skin of pre-term neonates. Journal of Wound Care. 2001;10(7):253-256.

Janssen PA, Selwood BL, Dobson SR, et al. To Dye or Not to Dye: A randomized clinical trial of a triple dye/alcohol regime versus dry cord care. Paediatrics. 2003;111(1):15-20.

Jørgensen FS, Felding P, Vinther S, et al. Vitamin K to neonates. Per oral versus intramuscular administration. Acta Paediatrica. 1991;80:304-307.

Jowitt M. Birth and bonding. Midwifery Matters. 1996;69(Summer):3.

Keels Conner G. Abdomen assessment. In Tappero EP, Honeyfield ME, editors: Physical assessment of the newborn, 2nd edn, California: NICU INK, 1996.

Laurent C. A mother’s nightmare. Nursing Times. 1992;88(52):18.

Lerner H. Sleep position of infants: applying research to practice. Maternal and Child Nursing. 1993;18(Sept/Oct):275-277.

Lim P. Baby massage. British Journal of Midwifery. 1996;8:439-441.

McLennan I. Ian’s story. New Generation. 1995;June:13.

McLintock F. Baby massage. Connections. 1995;26(2):4-6.

Michie M. A delicate concern: caring for neonatal skin. British Journal of Midwifery. 1996;4(3):159-163.

Morley C. Measuring infants’ temperatures. Midwives Chronicle and Nursing Notes. 1992;Feb:26-29.

Moss GD, Cartlidge PHT, Speides BD, et al. Routine examination in the neonatal period. British Medical Journal. 1991;302:878-879.

National Health Service Screening. Antenatal and newborn screening programmes. Online. Available www.screening.nhs.uk, 2006.

NICE guidelines The postnatal care guidelines. National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Online. Available www.nice.org.uk, July 2006.

Nursing & Midwifery Council. Guidelines for records and record keeping, NMC, London, 2007. Online. Available www.nmc-uk.org/aArticle.aspx?ArticleID=1673.

Penny-MacGillivray T. A newborn’s first bath: when? Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1996;25(6):481-487.

Perry SE. Nursing care of the newborn. In: Bobak IM, Lowdermilk DL, Jensen MD, et al, editors. Maternity nursing. 6th edn. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2002:461-513.

Rabinowitz R, Hulbert WC. Newborn circumcision should not be performed without anaesthesia. Birth. 1995;22(1):45-46.

Ratnaike D. Fathers present or just in the room. Midwives. 2007;10(3):106.

Righard L. How do newborns find their mother’s breast? Birth. 1995;22(3):174-175.

Roberton NRC. Care of the normal term newborn baby. In Rennie JM, editor: Roberton’s textbook of neonatology, 4th edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

Roberton NRC. A manual of normal neonatal care, 3rd edn. London: Edward Arnold, 1996.

Rushforth JA, Levene MI. Behavioural response to pain in healthy neonates. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1994;70(3):F174-F176.

Rutter N. Temperature control and its disorders. In Rennie JM, editor: Roberton’s textbook of neonatology, 4th edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

Rutter M. Clinical implications of attachment concepts: retrospect and prospect. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1995;36(4):549-571.

Saigal S, Nelson N, Bennett K, et al. Observation on the behavioral state of newborn babies during the first hours of life. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;139:715.

Shearer MJ. Vitamin K. Lancet. 1995;345(8944):229-234.

Stern CM. Neonatal immunology. In Roberton NRC, editor: Textbook of neonatology, 3rd edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999. Ch. 43

Thomas K. Thermoregulation in neonates. Neonatal Network. 1994;13(2):15-22.

Thomas R, Harvey D. Neonatology colour guide, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1992.

Trotter S. Management of the umbilical cord – a guide to best care. RCM Midwives Journal. 2003;6(7):308-311.

Trotter S. Care of the newborn: Proposed new guidelines. British Journal of Midwifery. 2004;3:152-157.

World Health Organization. Care of the umbilical cord: a review of the evidence. Reproductive Health (technical support). Maternal and Newborn Health/Safe Motherhood. WHO, Geneva, 1999.

Klaus MH, Kennell JH. Bonding: building the foundations of secure attachment and independence. London: Cedar, 1996.

This book will give the midwife insight into other aspects and studies regarding the parent infant attachment and should be read to compliment the information in this chapter.

Perry SE. The newborn. In Bobak IM, Lowdermilk DL, Jensen MD, editors: Maternity nursing, 6th edn, Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2002. Ch. 19

This book will expand on the physiology of the baby’s systems at birth, which is discussed in this chapter

Tappero EP, Honeyfield ME. Physical assessment of the newborn. A comprehensive approach to the art of physical examination, 2nd edn. NICU INK, California, 1996.

This newborn assessment book is a valuable resource for all midwives involved in the care of the newborn baby. It will also assist the midwife who has extended her role to include the final examination of the newborn baby.

Thomas R, Harvey D. Neonatology colour guide, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1992.

This is a concise text, clearly integrated with high quality colour clinical photographs; it is an essential resource for midwives involved in the examination of the newborn baby.