Development of Childhood Occupations

1 Explain historical and current theories of child development.

2 Define how a child’s unique characteristics influence skill development

3 Using an occupational therapy perspective, explain how occupations develop.

4 Explain how individual biological systems and cultural, social, and physical contexts contribute to a child’s occupational performance in the first 10 years of life.

5 Describe the development of play and the variables that contribute to the development of play.

An understanding of child development is foundational knowledge for pediatric occupational therapists. Researchers from many disciplines, including medicine, psychology, anthropology, education, sociology, and occupational therapy, have contributed to the literature on human development, and the different perspectives they provide should be woven into a holistic and comprehensive understanding of how children become adults.

Occupational therapists want to know what developmental changes occur in children and how children develop their unique personhood. The answers to these questions provide essential knowledge for evaluating children and for determining the appropriate materials, activities, and environments to support children’s skill development and participation in their communities. They are also interested in how human occupations develop over the life span.

This chapter focuses on child development theories, with emphasis on concepts that have emerged in the past 2 decades. The first section discusses concepts that explain how children develop and what variables and interactions influence developmental outcomes. In the second part of the chapter, a model for the development of childhood occupations is applied to children’s development of play in the first 10 years of life. Chapter 4 describes the development of pre-adolescent and adolescent occupations in the second decade of life.

DEVELOPMENTAL THEORIES AND CONCEPTS

Researchers of the 1930s and 1940s identified a sequence of skill maturation that defined the steps of normal development. Gesell and Colleagues42–44 and McGraw74 assumed that normal development was revealed through a specific skill sequence that reflected maturation of the central nervous system (CNS). These workers believed that the sequence of motor, cognitive, socioemotional, and language skill development was relatively unaffected by the infant’s experiences. The work of these neuromaturational theorists in documenting this developmental sequence has been well respected and has allowed the creation of developmental assessment tools. The sequence of normal development is an important frame of reference for identifying children with disabilities. Gesell and coworkers believed that variations in the normal sequence of development indicate CNS dysfunction. Identifying children with developmental deficits or significant delays remains an important function of physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, and others who provide early intervention services.

Neuromaturation

Neuromaturational theory has been used frequently to explain motor development.34,76 According to neuromaturational theory, brainstem structures develop first, as evidenced by the reflexive responses of the newborn (e.g., automatic grasp, asymmetric tonic neck reflex), which are controlled by neural pathways originating in the brainstem. Cortical structures appear to develop later, as evidenced by the coordinated and planned actions of the child. The infant’s increasing control of action and movement indicates not only development and myelination of the midbrain and cortical structures, but also simultaneous inhibition of brainstem control of movement. Three primary principles of neuromaturational theory are recognized:

1. Movement progresses from primitive reflex patterns to voluntary, controlled movement. In newborn and young infants, motor reflexes provide the first methods of interaction with the environment (e.g., reflexive grasp) and are essential to life (e.g., the sucking and swallowing reflexes). Because early reflexive movements serve functional needs, the newborn appears surprisingly competent. These reflex patterns subside as balance, postural reactions, and voluntary motor control emerge (i.e., when the infant learns to roll, sit, creep, stand, and walk).

2. The sequence and rate of motor development are consistent among infants and children. The developmental scales of Gesell and Amatruda,43 Illingworth,60.61 Bayley,8,9 and others are based on a typical rate and sequence of development. By assuming that the sequence of milestones (i.e., major motor accomplishments) is constant and predictable, the normative developmental sequence can be used to diagnose neurological impairment and disability.9

3. Low-level skills are prerequisites for certain high-level skills. For example, infants develop motor control in a cephalocaudal direction, with head control maturing first, followed by trunk control sufficient for independent sitting, and, finally, pelvic control sufficient for standing and walking.

In assuming a hierarchy of CNS function, the neuromaturational theory limited the thinking on how a child learns to act in the environment. Using current research models,47,52,100,102 it has become apparent that multiple variables at different levels influence the child’s skill development. The child learns occupations through interaction with his or her environment rather than through the emergence of a predetermined scenario reflecting neuromaturational principles.57

Development as an Interplay of Intrinsic and Environmental Factors

Piaget expanded our understanding of a child’s maturation by emphasizing that development occurs through the interplay between the environment and the child’s innate abilities (see Chapter 2).83 Piaget emphasized the maturation of cognitive structures that enable the child to understand the environment, language, and social action. Infants develop an understanding of the world by interacting with the environment. The impact of environment on the child’s development changes as the child becomes increasingly able to assimilate the complexities of physical and social events. Piaget also believed the development is stagelike and discontinuous. The infant is an active learner who is motivated to learn about the world. Piaget documented the child’s maturation through stages to the acquisition of symbolic thought and formal cognitive operations. The developmental stages follow a predictable sequence but vary to the extent that they reflect genetic endowment and the child’s experiences. This interplay between the child’s abilities and his experience can be appreciated in the early development of tool use. Piaget observed that children at 8 to 10 months manipulate two objects and can move an obstacle to reach an interesting or novel object. By 12 months, infants can relate an object to other objects, in addition to relating the objects to themselves. At this stage, infants use a stick to rake in an object out of reach and place objects into containers. By 18 months, infants begin to use trial and error to solve problems. At 24 months of age, they no longer exclusively need physical manipulation to solve problems and begin to demonstrate use of mental manipulation.73,83

Research studies in the 1990s demonstrated that cognitive structures develop at earlier ages than Piaget assumed; they have also demonstrated that child development has more continuity and integration across the stages of development.13,37 Infants as young as 1 month demonstrate the ability to associate learning from one sensory system with another sensory system. For example, they recognize objects with their eyes that they previously felt in their mouths.70 Researchers have also found that 9-month-old infants can remember an event 1 week after it happened.75

Other research that has updated Piaget’s demonstrated that toddlers can manipulate and use tools and can solve problems such as how to grasp and use a spoon. McCarty and colleagues found that children 9 to 14 months of age picked up the spoon using an awkward grasp and then attempted to adjust the spoon’s orientation to get the food into the mouth.73 Children 19 months old planned how to grasp and orient the spoon to get the food before acting, avoiding the use of an awkward grasp that required adjusting. This study showed that children as young as 19 months can solve problems without physical manipulation and trial and error to handle a tool accurately. By this age, the child can scoop food, fill the spoon, and correctly angle it toward the mouth,56 signifying the early emergence of tool use.

Scholars have critiqued and expanded Piaget’s original theories to fully appreciate how the environment influences development. For example, Piaget’s theories lack appreciation of the influence of culture, society, and technology on children’s development. Current occupational therapy theories consider these variables to have important roles in a child’s development.10,116 In addition, Piaget’s theories did not address the development of emotions and did not have a coherent explanation for individual differences, individuality, or variability.37 The importance of variability has been highlighted in the work of other psychologists100,103 and by occupational therapy researchers.59

The Influence of Social Interaction

Following Piaget, another developmental theorist, Vygotsky, believed that children learn through social interaction.109 Vygotsky’s theories emphasized the importance of culture and shared participation in culturally valued activities to children’s development. He demonstrated that children learn when scaffolding, or support, is provided by caregivers and teachers. Parents and other family members intuitively provide environmental challenges that encourage the infant to exhibit a higher skill level and then support the infant’s efforts to reach that level. Parents and siblings naturally promote the infant’s development by modeling actions, assisting the infant’s first attempts to perform an action, and reinforcing his or her efforts with praise and expressions of delight.

Vygotsky explains the role of social interaction in children’s development by defining a “zone of proximal development” as “the distance between the actual development level as determined by [the child’s] independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through [his] problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86).109 He believed that what children can do with the assistance of others was more indicative of their mental development than what they could do independently. When presented with a just right challenge, e.g., a task that is slightly more difficult than the tasks the child has currently mastered, the child generally attempts and succeeds in this challenge, thereby learning the next step in skill development.

Vygotsky and the many subsequent developmental theorists have examined how human development transpires through a dynamic interplay involving the child and the child’s cultural, social, and physical environments. Researchers of child development have documented differences in the rate of development in socioeconomic groups, regions, and individuals. For example, rates of development appear different in rural versus urban areas.106,108 Children’s rate of development also differs among cultural groups and generations, in part because of differences in nutrition and child care practices. In human development research, the emphasis currently is on the variations expressed by individual infants and on how human systems and environmental constraints contribute to these variations.

Studies that analyze the uniqueness of individual performance often use longitudinal and qualitative approaches to analyze the performance of children over time and in natural contexts.11,102 Because these longitudinal studies document the patterns of development over time, they uncover how individual systems are constructed and assembled. Longitudinal approaches make it possible to relate transitions of subsystems to each other and to other dynamic growth parameters.108 Understanding how children acquire qualitative differences in functional performance and how they become unique individuals can begin by focusing on the variables that influence a child’s developmental course. The following sections examine current theories of development that explain the relationships among a child’s biological functions, occupations, and environments.

Dynamical Systems Theory

Dynamical systems theory refers to performance or action patterns that emerge from the interaction and cooperation of many systems, both internal and external to the child.101 In the context of child development, performance patterns emerge from the interaction of an individual’s systems and performance contexts as the child strives to achieve a functional goal.71,72 The dynamical systems theory is useful in describing how specific motor and process skills develop.

In this model, a child’s behaviors and actions are initially highly variable, with many degrees of freedom. The first actions of the infant have been described as random and uncontrolled. Development of skill proceeds by means of constraint of these degrees of freedom as the child gains control of his or her actions. Behavior, therefore, is not prescribed by a hierarchical arrangement of the CNS, but rather emerges from external and internal constraints.97 These constraints provide information to the brain and body systems that set the boundaries or limits for the child’s behavior.22

Humans are complex biological systems comprising many subsystems (e.g., motor sensory, perceptual, skeletal, and psychologic subsystems). These subsystems are in constant flux, interacting according to the task at hand and conditions in the environment. The child’s actions during the performance of a task, therefore, are the result of the subsystems’ interaction with each other and with the environment. These individual systems come together and self-organize in a coordinated way to achieve the child’s goal.97 For example, initially a child is interested in exploring the sensory characteristics of a toy. As he or she reaches for the toy, grasps it, and brings it to midline in hand-to-hand play and then finally to the mouth, the child’s attention and cognitive focus are not on planning each of these actions. Instead, they are on assimilating the toy’s actions and perceptual features.

Longitudinal studies reveal that children demonstrate unique trajectories of development and that variations in functional performance among children persist into adulthood. Thelen and her colleagues demonstrated the uniqueness of motor development in a study of reaching in 4- and 5-month-old infants.102 Each 5-month-old infant was able to reach toward an object, but the patterns demonstrated were unique. Some infants demonstrated a slow, cautious first approach to the object, whereas others made ballistic arm movements in an attempt to reach it. Although all first reaches tended to be circuitous, the amount of correction made to obtain the object, the speed at which the attempt was made, and the angle at which arms were held were different. These investigators concluded that the development of reaching did not reflect changes in a single factor, but rather to reach and grasp an object, the infant needed to (1) be motivated, (2) localize the object in space, (3) understand that the object was reachable, (4) plan the trajectory of the reach, (5) correct the movement as the hand approached the toy, (6) lift and stabilize the arm, and (7) grasp the object. How a 5-month-old infant manages all of these components to reach and grasp a toy successfully varies among infants and for different reasons.

In a similar way, between 8 and 10 months, most infants acquire the motivation to be independently mobile. The need to self-initiate movement from place to place emerges as an important task, or goal, to accomplish. This goal reflects the infant’s curiosity about the environment, a desire to explore space, and a determination to reach a specific play object. Although mobility becomes a common goal for the infant toward the end of the first year, the method used to achieve that mobility varies greatly. Some infants roll to another space in the room, whereas others scoot on their buttocks in a sitting position. Some infants push backward while lying in a prone position, and others creep forward to explore their environment. How the infant achieves mobility is influenced by many contributing body systems (e.g., strength, coordination, and sense of balance and movement). Conditions in the environment also influence infant mobility (e.g., the surfaces on which the child plays, the encouragement provided by caregivers, and the way in which the task is presented). The child’s energy level, motivation, and curiosity about the environment also influence when independent mobility is achieved. In addition to the factors that influence the maturation of mobility skills, becoming mobile influences the development of skills in other performance domains. When an infant achieves mobility, he or she becomes more independent in initiating a social interaction or in seeking help. Therefore, independent mobility contributes to the acquisition of social skills, self-determination, problem solving, and motivation to explore (see Chapter 21). A child learns perceptual skills, spatial relations, form perception, and object relations by moving through the environment.

Perceptual Action Reciprocity

Perception and action are interdependent and inextricably linked. An individual’s perception of the environment informs action, and the individual’s actions provide feedback about movement, performance, and consequences in the environment. Initially, many of the child’s actions are exploratory in nature—that is, the child moves fingers over the surfaces of objects to learn their shape, texture, and consistency. The child waves an object in the air to hear the sounds it makes and feel its weight. These actions help the child perceive sensory and perceptual features (affordances) of objects. Affordance is the fit between the child and his or her environment.46,48,49 The environment and objects in it offer the child opportunities to explore and act. This action is based on what the environment affords, as well as the child’s perceptual capability to recognize affordances in that environment. For example, colorful noise-making toys afford manipulation because they have movable parts and rounded surfaces and fit easily into an infant’s hand. Learning about affordances entails exploratory activities. Individual finger movements, thumb opposition, hand-to-hand transfer, and eye-hand coordination are facilitated by the physical characteristics of the toy.

Manipulation is guided by visual, tactile, and kinesthetic input.86,94 Exploration of objects begins with visual exploration and mouthing.87 By 6 months, infants prefer exploring with their eyes and hands.86 Fingering and manipulation skills increase substantially between 6 and 12 months, enabling infants to gather more precise information about objects. By 12 months, infants detect object properties with increasing specificity and learn to adjust their exploratory action.1 For example, to perceive the consistency of a soft, squishy object, a child squeezes it, and to perceive the texture of velvet or corduroy, he or she runs the fingers back and forth over it.

Through object manipulation, the child develops haptic perception (i.e., an understanding of objects’ shape, texture, and mass). Bushnell and Boudreau propose that specific motor skills are required to develop haptic perception.12 They note that infants learn to identify an object’s sensory qualities (e.g., texture, consistency, temperature, contour) only when they develop the motor skills to explore each different sensory quality. For example, an infant does not accurately discriminate texture until he or she can explore texture by moving the fingers back and forth (at about 6 months). The child also cannot discriminate hardness until 6 months, when he or she can tighten and lessen the grip while holding an object.12 Because configural shape requires that two hands be involved in exploring an object’s surfaces, children typically cannot accurately perceive shape until 12 months. By 2½ years, children can identify common objects through their haptic sense, and by 5 years, children recognize common objects using active touch (without vision).16 By 5 years, the child has also fully developed in-hand manipulation skills,82 suggesting that haptic perception develops in association with the child’s development of manipulation skills. Maturation of haptic perception and manipulation underlies the child’s ability to use tools for written communication (e.g., handwriting and keyboarding) and activities of daily living.

Functional Performance: Flexible Synergies

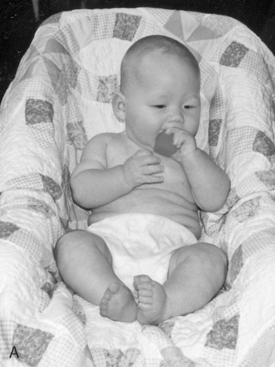

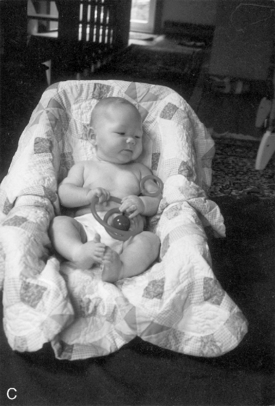

As mentioned, the infant begins life with few constraints on performance, which permits the greatest variability in the system for the generation of spontaneous movements. This variability permits flexibility for exploration of the environment and rapid perceptual and cognitive learning. The infant quickly selects functional synergistic movement patterns. For example, from birth the infant demonstrates a pattern of hand-to-mouth movement (e.g., for self-calming by sucking on a fist) (Figure 3-1). Only minimal adaptive changes are made in this synergistic pattern (shoulder rotation and horizontal adduction, elbow flexion and forearm pronation, followed by supination and neutral wrist position) as the child learns to self-feed with various utensils (Figure 3-2).

FIGURE 3-1 Hand-to-mouth movement is observed throughout the first year, first for sensory exploration of the mouth and hand and then as a feeding behavior. From Henderson, A., & Pehoski, C. [2006]. Hand function in the child: Foundations for remediation [2nd ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.

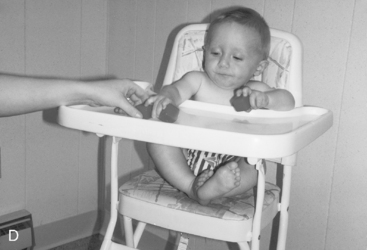

FIGURE 3-2 By 7 to 8 months, an infant finger-feeds, prehending small food pieces and bringing hand to mouth.

Because synergies that enable tool use are softly assembled around the goal of the task at hand, they are stable but flexible units. Synergies have specific consistent characteristics, such as the sequence of movements and the ratio of joint movement, which can be adjusted to accommodate each new situation. This adaptable stability is a hallmark of normal movement.21 Soft assembly is critical to allow the child to act in changing and variable environments. It also allows the child to explore and select a response to the environment, because his or her response patterns are variable and flexible.97

The functional synergies that characterize a child’s development of occupations are highly adaptable and reliable. The child self-organizes these synergies around tasks and goals, and his or her first goals are embedded in and organized around play (as described later in this chapter).

How Do Children Develop New Performance Skills?

How does a child learn new performance skills? Although learning new skills is not limitless and is constrained by biologic and contextual factors, human development is believed to have relative plasticity.66 This concept has obvious importance to occupational therapists, who provide intervention services designed to change and promote children’s performance. Gottlieb defines plasticity as a fusion of the organism (the child) and the environment (including its cultural, physical, and socioeconomic characteristics).52 Individual development involves the emergence of new structural (e.g., cellular) and functional components (e.g., body systems). The child’s experiences produce new neurologic connections (i.e., new associations) and structural changes (e.g., physical growth), and it is the relationships among components, not the components themselves, that are most important to development. Acknowledgment of the system’s plasticity places the focus on the child’s potential for change and on the contextual features that promote or limit the child’s performance.

How does competence develop during childhood? Children generally pass through three stages of learning to acquire a new skill.48,84,103 The first stage involves exploratory activity. The first year of life is primarily a period of sensorimotor exploration. Exploration occurs naturally in all human beings, generally when an individual is presented with a new object or task. Through exploration, a child learns about self and the environment. In this stage, the child experiments with objects and activities using different systems, new combinations of perception and movement, and new sequences of action. In this exploratory stage or when challenged by a new and difficult task, a child tends to demonstrate primitive movement. New challenges tend to elicit lower levels of skills, because these can be accessed more easily than the child’s highest-level skills, which demand more energy and effort.53 By using lower-level skills to address new problems, the child can focus on perceptual learning about the task before beginning to use higher-level skills, which ultimately allow more success in performing the task. Gilfoyle, Grady, and Moore noted that when children are first challenged with a new and difficult performance task (e.g., a first step), they use primitive movement patterns (e.g., balance by stiffening the legs and trunk) before progressing to integrated skill.50

In the second stage of learning, perceptual learning, the child begins to use the feedback and reinforcement received from his or her exploration. In this transitional stage, the child exhibits more consistency in the movement patterns used to accomplish tasks. Because this second stage is a phase of perceptual learning, certain actions that were tried initially are discarded as ineffective. Interest in the activity remains high as perceptual learning continues and is inherently motivating and meaningful to the child. In this stage, the child appears focused on learning and attempts activities multiple times. The child may fluctuate between higher and lower levels of skill. Connolly and Dalgleish found considerable variability when toddlers attempted to use a spoon.26 Greer and Lockman found similar variability when 3-year-olds attempted to use a writing tool.55 At times, the children grasped the tool using an adult gripping pattern, and at other times, they used a primitive, full-hand grasp. Mature patterns are selected more often as children enter the third stage of skill learning.

In the third stage of learning, skill achievement, the child selects the action pattern that works best for achieving a goal. The pattern selected is comfortable and efficient for the child. Selection of a single pattern indicates both perceptual learning and increased self-organization. During this end stage of learning, the child demonstrates flexible consistency in performance. He or she uses the same pattern and approach to the task but easily adapts the pattern according to task requirements. High adaptability is always characteristic of a well-learned task. Another attribute of learned performance is the use of action patterns that are orderly and economical. Children continue to practice performance when given opportunities in the environment. The third stage of learning leads to exploration of new and different activities; therefore, a child’s learning continues into new performance arenas, expanding his or her occupations.

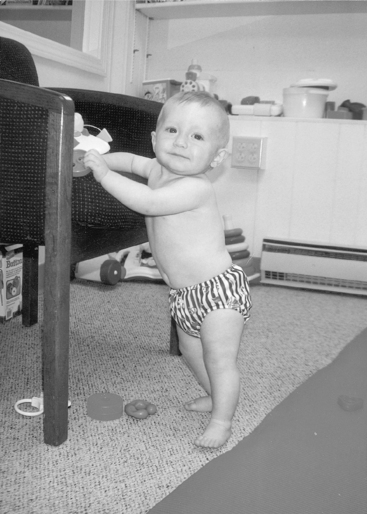

For most children, new experiences and new learning are sought and are a source of pleasure. Learning occurs when children seek opportunities for skill development; it also occurs when children adapt to the natural environment and daily activities in which they participate. Ayres explains that children make adaptive responses to the environment.3,4 An adaptive response is one in which the child responds to an environmental change in “a creative or useful way” (p. 14).4 These adaptive responses allow skill mastery and help to organize the child’s CNS. Therefore, an adaptive response helps to integrate the child’s sensory and perceptual systems to respond more skillfully to new challenges to the sensory system. For example, once the infants can pull themselves up to a standing position using a piece of furniture, they have acquired an adaptive skill that enables them to pull up to the mother’s lap to ask to be held or explore the objects on a coffee table. This organization of movement patterns was achieved because the vestibular, proprioceptive, and visual systems are innately organized toward achieving upright posture (Figure 3-3).

The Role of Motivation and Self-Efficacy

Children engage in the process of learning with innate motivation and apparent enjoyment. An infant’s inner drive motivates her to explore novel objects in the environment, learning their sensory characteristics, their relationships to each other, and their functions. A toddler or young child is motivated to solve problems and to attempt new skills, persevering until it is mastered. The concept of inner drive suggests that children attempt activities that will promote their development without specific teaching by adults. Occupational therapists view this innate drive as the child’s inner motivation to engage in occupations (task with meaning and purpose). Learning occurs when the match among child, task, and environment is optimal; hence, this match becomes the occupational therapist’s goal.58 When a child has a disability, motivation to learn and attempt new activities may be lower and the match among child, occupation, and environment may be less than optimal. In this case, a child may not learn independently and adult support may be needed to motivate, provide a just right challenge, support actions, and reinforce performance.

When a child’s inner drive leads to mastery of tasks, he or she develops a sense of self-efficacy.5–7 Bandura believes that children are inherently self-organizing and goal-directed; they typically have interest in new events and activities, initiate new tasks, and persevere in those tasks. When they succeed, positive self-efficacy is reinforced and they attempt other challenges. When they do not succeed, they are at risk for developing poor self-efficacy and eventually do not attempt new or challenging activities. Therefore, self-efficacy is highly linked to learning and occupational development because it influences levels of motivation, initiative, and perseverance.

Temperament and Emotional Development

The congruence, or goodness of fit, between the child and his or her social and physical context determines the quality of development, influencing which occupations are reinforced and which are hindered. Positive goodness of fit, meaning that the social and physical environment support the child’s skill development, can increase the child’s developmental trajectory. Lack of goodness of fit can create disruption of psychologic development and may put the child at risk for behavioral or academic problems.

Chess and Thomas asserted that if a child’s characteristics provide a good fit (or match) with the demands of a particular setting, adaptive outcomes result.19,20 The child’s temperament is an important determinant in how well a child matches the caregiving environment67 and is an important attribute in the child’s social interaction. According to Thomas and Chess, temperament refers to the child’s behavioral style, and it is believed to be innate and learned.104 Nine areas of temperament have been identified: (1) activity level, (2) approach or withdrawal, (3) distractibility, (4) intensity of response, (5) attention span and persistence, (6) quality of mood, (7) rhythmicity, (8) threshold of response, and (9) adaptability. Each of these areas contributes uniquely to the child’s ability to form social relationships and respond to the social environment.104

Taken together, these areas of temperament have their own continuum: extreme temperament levels are associated with problematic behaviors, and moderate levels are related to easy and appropriate behaviors. Children who exhibit extreme temperament characteristics (e.g., those who are highly active, moody, or irritable) have been identified as difficult. The difficult child may not fit with the expectations and schedules of caregivers. Others with happy moods and moderate intensity of response are considered easy. A child with an easy temperament may be rhythmic (exhibiting regular sleep/wake cycles) and have positive moods and may have a better fit with caregivers. A match of parent and infant temperament can facilitate strong attachment, just as a mismatch can create difficulties in attachment.

To illustrate how temperament affects goodness of fit, children with arrhythmic, poorly regulated sleep/wake cycles were reported to be difficult to manage by European American families in which the parents worked and needed a consistent routine of sleeping patterns. Puerto Rican parents did not have difficulty in accommodating children with poorly regulated sleep/wake cycles because they molded their schedules around them and allowed their children to sleep when they wanted. In the Puerto Rican families, the incidence of child behavior problems was very low, particularly before school age when a school schedule was imposed.66 These studies and many others suggest that the child’s temperament and behavior affect goodness of fit between the caregiver and the child, which in turn influences developmental outcomes.20

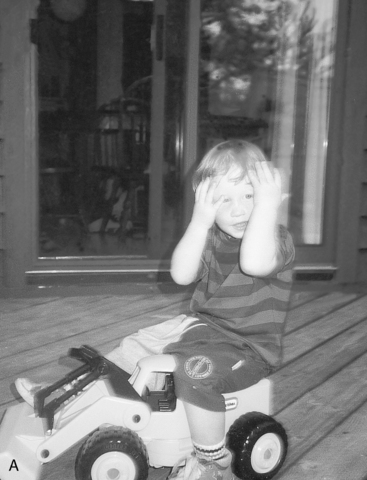

Emotions also play an important part in the child’s appraisal of his or her experience and in the child’s readiness for action in response to contextual change. Emotions relate to how a child evaluates the meaning of an experience in relation to his or her goals. Therefore, if a child engages in an activity with the goal of succeeding but does not, he or she may become disappointed or frustrated. If a child engages in an activity simply to participate and without expectation for success, he or she may experience pleasure irrespective of success. Emotions and temperament (see Chapter 13) influence the child’s interest in attempting new activities, the amount of effort demonstrated, and attempts to engage others. These variables influence how a child approaches an activity (e.g., joyfully, reluctantly) and influences its social nature (e.g., whether the child solicits the involvement of others).

Risk and Resiliency

As suggested in the previous section, developmental outcomes have been attributed to the child’s personality. Research has shown that certain children attain positive developmental outcomes despite a poor caregiving environment. Resiliency refers to a child’s internal characteristics that enable him or her to thrive and develop despite high-risk factors in the environment. The concept of resiliency emerged from studies of child development in which the context included risk factors known to have negative effects (e.g., child abuse, parental mental illness or substance abuse, socioeconomic hardship).107,110 A resilient child has protective factors that enable him or her to develop positive interpersonal skills and general competence despite stressful or traumatic experiences or social environments known to limit developmental potential (e.g., that of an adolescent, single parent). Both child protective factors (e.g., intelligence, prosocial behavior, and social competence) and family protective factors (e.g., material resources, love, nurturance and sense of safety and security, quality of parent-child relationship) are important to positive child outcomes. Researchers have demonstrated that a high-quality relationship with at least one parent, characterized by high levels of warmth and openness and low levels of conflict, is associated with positive outcomes across levels of risk and stages of development.111

A child’s resiliency versus vulnerability also seems to relate to basic physiologic and regulatory characteristics. Children with low cardiovascular reactivity and high immune competence cope better with stressful situations and are less vulnerable to illness when stressed.110 In middle childhood, well-developed problem solving and communication skills are important to a child’s ability to deal with stress. Resilient boys and girls tend to be reflective rather than impulsive, demonstrate an internal locus of control, and use flexible coping strategies in overcoming adversity.110 Therefore, not only are intelligence and competence important to positive outcomes, but so is emotional regulation, that is, being able to monitor, evaluate, and modify the intensity and duration of emotional reactions.107

These concepts suggest that in the interpretation of the influence of environmental factors on a child’s development, variables internal to the child can overcome negative contextual variables, including those believed to have a profound influence (e.g., poor caregiving). Although the evidence suggests that children with strong resilience can overcome a high-risk environment (e.g., abusive situations, poverty), a recent research synthesis of risk and resilience studies found that both internal (e.g., child’s intelligence, positive affect, emotional regulation) and contextual (e.g., supportive family relationships) protective factors are needed for positive outcomes (e.g., school success, positive relationships).107 Taken together, the theories that explain how children grow and develop into competent adults and full participants in the community suggest that a child’s development of occupations must always be understood as an interaction between the child’s biological being and his or her cultural, social, and physical contexts.

AN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PERSPECTIVE

Occupations can be defined as the “patterns of action that emerge through transaction between the child and environment and are the things the child wants to do or is expected to do” (p. 22).58 Although most children accomplish certain occupations and their corresponding tasks in a known sequence, the way these tasks are accomplished is unique for each child. A child learns new occupations based on the facility that she or he brings to the activity. Motor and praxis, sensory-perceptual, emotional regulation, cognitive, and communication and social skills contribute to occupational performance.2 These skill areas are interdependent; that is, they work together in such a way that the strengths of one system (e.g., visual) can support limitations in others (e.g., kinesthetic). Which systems are recruited for a task varies according to the novelty of the activity and the degree to which the task has become automatic. For example, research has shown that self-feeding using a spoon involves visual-perceptual, kinesthetic, visual-motor, and cognitive systems.25,45,56 As previously described, grasp of the spoon initially is guided by vision, and the child uses trial and error to hold the spoon so that he or she can scoop the food. With practice and maturation, grasp of the spoon is guided primarily by the kinesthetic system, and correct grasp becomes automatic; vision plays a lesser role. Once food is in the mouth, chewing skills require primarily oral motor skill and somatosensory perception of food texture and food location within the mouth. The skills involved in occupational performance vary not only according to the learning phase but also according to the child’s learning preferences and styles.

Development of Occupations

Humphry proposes that three broad mechanisms enable children to develop occupations.58 These mechanisms, society’s investment in children and their participation in the community, interpersonal influences including caregiving adults and peers, and the dynamics of the child’s occupational performance, are briefly described next.

The broadest influence on children’s occupations is the community in which the child is raised. Communities and society in general have invested in children’s occupations by providing playgrounds, preschools, child-oriented music, child-oriented restaurants, and soccer fields. A community’s orientation toward children determines available opportunities to play organized sports, learn about art and music, safely play in neighborhoods, and gain friendships with diverse peers. Communities that value organized sports and outdoor activity may have soccer or baseball teams, horseback riding, and swimming specifically designed for children with disabilities (e.g., Special Olympics, Miracle League Baseball, therapeutic horseback riding). Characteristics of the community become barriers or opportunities for the child and family and their desired occupations. As advocates for children with disabilities, occupational therapists can influence the development of programs that are accessible and appropriate for children with a wide range of ability. They can emphasize the importance of supporting the participation of all children in community activities, recognizing the different levels of support and accommodation needed.

Humphry suggests that children learn through both direct and indirect social participation.58 A young child’s first learning about an occupation is often through observing his parents, siblings, and other adults or peers. The first representational pretend play is typically imitation of the mother’s actions when cleaning and cooking. Children imitate their parents’ gestures and speech without being explicitly taught to do so. They also learn the consequences of actions by observing how their parents respond to each other or to their siblings. They can learn that an action is wrong by observing punishment of a peer for that action. Vicarious learning appears to be particularly important to a child’s assuming cultural beliefs and values. Children learn the traditions and rituals of a culture by observing their family’s participation in these. Inclusive models of education are believed to be effective learning environments for children with disabilities based on the known benefit of observing and interacting with typical peer models.31,32 When in a child’s presence, therapists should always be conscious that their actions and words influence children’s learning and of whether these actions are directed toward the child.

Learning is generally more vigorous when the child actively participates in an occupation. Children’s play with each other is an integrated learning experience in which the child acts, observes, and interacts. Play involves most or all performance areas, including affective, sensory, motor, communicative, social, and cognitive. When children play together, they learn from, model for, challenge, and reinforce each other. This flow of interactions occurs in meaningful activities that generally bring pleasure and intrinsic reinforcement and enable learning.

To learn a specific skill, the child must actively practice it. Specific scaffolding, guidance, cueing, prompting, and reinforcement by an occupational therapist can assist the child in learning to perform a skill. This direct support from the therapist (or other adult) can facilitate performance at a higher level or at a more appropriate level so that the fit between the child and desired occupations and context becomes optimal. In the case of a child with disabilities, a more intensive level of direct support and scaffolding may be necessary for learning new skills. Adult guidance and support of the child during play can facilitate a successful strategy, help the child evaluate his or her performance, and encourage and reinforce continued practice. Therapists can also optimize the environment to support and reinforce the child’s performance. Participation in play occupations in a natural environment results in integrated learning across performance areas (e.g., including sensory, motor, cognitive, and affective learning).

The child’s play and actions are always within a social, cultural, and physical context. To understand the development of occupational performance, the occupational therapist must understand the child’s play and actions as coherent occupations within specific contexts.

Contexts for Development

Children develop occupations through participation in family activities and cultural practices. As a child participates in the family’s cultural practices, he or she learns occupations and performance skills that enable him or her to become a full participant in the community. Rogoff explains: “People develop as participants in cultural communities. Their development can be understood only in light of the cultural practices and circumstances of their communities” (pp. 3–4).88 Variations in the child’s play activities (e.g., how he or she builds with wooden blocks, draws a picture of himself or herself, or sings a song) reflect the child’s biological abilities and the influence of cultural, social, and physical contexts.

A child’s cultural, social, and physical contexts change through the course of development and tend to expand as the child matures. The environment surrounds and supports the child’s action; it also forces the child to adapt and assists or accommodates that adaptation. As a child perceives the affordances of the environment, he or she learns to act on those affordances, expanding a repertoire of actions. At the same time, the child’s understanding of how the world responds to his or her actions increases. Rogoff argued that culture affects every aspect of the child’s development, which cannot be understood outside this context.88 The child is nested in his or her family, culture, and community, which have influenced the child’s genetic makeup and continue to provide the learning environment. By recognizing this influence, occupational therapists view each child in his or her cultural context and work as change agents within that context.

Cultural practices are the routine activities common to a people of a culture and may reflect religion, traditions, economic survival, community organization, and regional ideology. The child learns motor and process skills through his or her participation in these cultural practices. Reciprocally, a child’s motor and process skills enable participation in the occupations and cultural practices of the child’s family and community.

Cultural Contexts

To fully understand how children develop through participation in cultural practices, Rogoff and her colleagues have studied child development in various cultures, including the European American culture. Their findings, as well as the findings of occupational therapists,10,30 have expanded our understanding of how children develop and have broadened the definition of typical child development.

Cultures vary in many aspects, such as the roles of women and children, values and beliefs about family and religion, family traditions, and the importance of health care and education. The continuum of interdependence versus autonomy of individuals varies in cultural groups and is a significant determinant of childhood occupations. The value a people or community places on interdependence among its members versus individual autonomy creates differences in child-rearing practices and different experiences for developing children.

Most middle-class European Americans value independence as a primary important goal for their children. U.S. parents encourage individuality, self-expression, and independence in their children’s actions and thoughts. To foster early independence in children, U.S. parents do not sleep with their infants; instead infants sleep in their own crib and/or room. Yet this practice is unusual within other societies in the world, such as Asia, Africa, and South America, where infants sleep in their parents’ bed or room.77 For example, Japanese parents report that co-sleeping facilitates infants’ transformation from separate individuals to persons able to engage in interdependent relationships. Japanese parents are interested in promoting continued reciprocity with their children, encouraging the primacy of family relationships.88

One consequence of the early separation of infants from their parents for sleeping is that middle-class U.S. parents often engage in elaborate and time-consuming bedtime routines. In contrast, Mayan parents reported that they do not use bedtime routines (e.g., stories or lullabies) to coax babies to sleep.89 To encourage interdependence, Mayan parents hold their infants continuously, and they often hold them so that they can orient to the group (i.e., facing other members of the group rather than their mothers). By observing others more than their mother, infants become aware of their adult community. In the Latino culture, which also encourages interdependence, parents are permissive and indulgent with young children. Latino parents do not push developmental skills, in part because they value interdependence with the family as opposed to autonomy of the individual.117

In general, cultures that value independence over interdependence also value competition over cooperation. Korean American children have been found to be more cooperative in play than European American children. Mexican children also are more likely to cooperate than European American children.88 These examples briefly illustrate how cultural beliefs influence the ways parents raise their children and communities support and challenge children.

Social Contexts

Culture influences the social relationships that envelop the child, yet certain aspects of the child’s social context appear to be independent of cultural influences and are consistent across cultures. This section defines elements of the social context particularly important to a child’s development. The most important relationships formed during infancy are those with parents and/or primary caregivers. When caregivers are sensitive and responsive to the infant, healthy socioemotional development results.33,68 Infants’ interactions with parents serve to enhance the infants’ basic physiologic and regulatory systems. When parents attune to the infant’s sensory modulation and arousal needs and support these needs, the infant develops secure attachment. Mothers who modulate their behaviors to match their infants’ needs for stimulation and comfort also promote the infants’ abilities to self-regulate. The child’s interaction with a caregiver gives him or her essential information about how self and other are related, which becomes important to engaging in future relationships. Attachment patterns seem to influence the child’s style of interaction and engagement in later years. Sensitive responding consolidates the infant’s sense of efficacy and provides a foundation of security for confident exploration of the environment.33

Csikszentmihalyi and Rathunde describe parenting as a dance between supporting and challenging the child.29 Supporting the child enables him or her to assimilate or explore the environment—that is, to play. Parental challenge requires a child to accommodate and conform. Parenting provides a combination of these supports and challenges. Rogoff defines the support-challenge combination of guided participation as adults’ challenging, constraining, and supporting children in solving problems.88 All parents use some measure of support to bolster children’s attempts to master skills and some degree of challenge to move children toward higher levels of mastery. These elements are subtly provided by parents in the ways they present tasks and select when and how they instruct or intervene. Effective guidance relies on careful observation of the child’s cues. Sensitivity and responsivity to the child’s needs appear to be among the most important variables in the promotion of child development.66 The concept of guided participation is similar to Vygotsky’s notion of the zone of proximal development. In guided participation, emphasis is placed on parents’ sensitivity to the child’s skills to determine the level of support or challenge needed.

In typical situations, infants receive care from multiple care providers, including child care providers, grandparents, and other adults. The infant may or may not attach to caregivers other than the parents or primary caregivers; however, these social relationships are important to the infant’s emotional development and provide opportunities for the development of social skills. At least 60% of children under 5 years of age participate in non-parent child care, including center-based and family child care.78 A study for the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development revealed that positive caregiving occurred when children were in smaller groups, child-to-adult ratios were low, caregivers did not use an authoritarian style, and the physical environment was safe, clean, and stimulating.79 Family factors predicted child outcomes even for children who spent many hours in child care. The family environment appears to have a significantly greater effect on a child’s development than the child care environment.38

Physical Contexts

The physical environment surrounds and supports the child’s action; it forces the child to adapt his or her actions to meet the demands and constraints of the physical surroundings. As a child perceives the affordances of the environment, he or she learns to act on those affordances, thus expanding a repertoire of actions. At the same time, the child’s understanding of how the world responds to his or her actions increases. Gibson explained how a child’s exploration of physical surfaces and objects allows him or her to develop and practice mobility and manipulation skills.47 Examples of the interactions of a child and his or her physical environments and the developmental consequences are presented next.

CHILDREN’S OCCUPATIONS, PERFORMANCE SKILLS, AND CONTEXTS

This section describes the child’s development of play occupations as enabled by his or her performance skills and cultural, physical, and social contexts. For three age groups—infancy, early childhood, and middle childhood—typical play occupations and activities are described. The contribution of motor, sensory, emotional, cognitive, and social abilities and contexts to the development of play occupations is described. Although children’s occupations are similar within a particular age level, the contexts, individual abilities, and activities are varied and diverse, resulting in a unique occupational performance for each child. Recognition of the uniqueness of a child’s development and of how these components contribute to performance within individuals is key to analysis of occupational performance.

Although the child learns occupations other than play (e.g., those related to school function), occupational therapists most often use play activities to engage the child in the therapeutic process. Play activities serve as the means to improve performance because they are self-motivating and offer goals around which the child can self-organize.81 Play also serves as the end or goal of therapy services. Children put effort and energy into play activities because they are inherently interesting and fun. (A more detailed description of play as a goal and modality of therapy can be found in Chapter 18.) Descriptions of a child’s development of feeding, self-care, and school function are presented in other chapters (Chapters 15,16 and 24). The contribution of communication abilities is also important to the development of play and other childhood occupations, but it is not discussed in this chapter because language and communication are not primary concerns for occupational therapists.

Infants: Birth to 2 Years

The play occupations of infants in the first 12 months are exploratory and social—that is, they are related to bonding with caregivers (Boxes 3-1 and 3-2). As in every stage, these occupations overlap (e.g., bonding occurs during exploratory play with the parent’s hair and face, and the parent’s holding supports the infant’s play with objects). Much of the infant’s awake and alert time is spent in exploratory play, often play that occurs in the caregiver’s arms or with the caregiver nearby.

Exploratory play is also called sensorimotor play. Rubin defined exploratory play as an activity performed simply for the enjoyment of the physical sensation it creates.92 It includes repetitive movements to create actions in toys for the sensory experiences of hearing, seeing, and feeling. The infant places toys in the mouth, waves them in the air, and explores their surfaces with the hands. These actions allow for intense perceptual learning and bring delight to the infant (without any more complex purpose).

In the second year of life, the infant engages in functional, or relational, play; that is, an object’s function is understood, and that function determines the action (Boxes 3-3 and 3-4). Initially, children use objects on themselves (e.g., pretending to drink from a cup or to comb the hair). These self-directed actions signal the beginning of pretend play.83 The child knows cause and effect and repeatedly makes the toy telephone ring or the battery-powered doll squeal to enjoy the effect of the initial action.

By the end of the second year, play has expanded in two important ways. First, the child begins to combine actions into play sequences (e.g., he or she relates objects to each other by stacking one on the other or by lining up toys beside each other). These combined actions show a play purpose that matches the function of the toy. Second, 2-year-old children now direct actions away from themselves. The objects used in play generally resemble real-life objects.67 The child places the doll in a toy bed and then covers it. The child pretends to feed a stuffed animal or drives toy cars through a toy garage. At 2 years of age, play remains a very central occupation of the child, who now has an increased attention span and the ability to combine multiple actions in play. The emergence of symbolic, or imaginary, play with toys and objects offers the first opportunities for the child to practice the skills of living.

The child also engages in gross motor play throughout the day. As he or she becomes mobile, exploration of space, surfaces, and large action toys becomes a primary occupation. Movement is also enjoyed simply as movement; the child delights in swinging and running or attempting to run and moving in water or sand. Deep proprioceptive pressure and touch are craved and requested. As in exploratory play, the child’s exploration of space involves simple, repeated actions in which the goal appears to be sensation. Often, extremes in sensation seem to be enjoyed and are frequently requested. Repetition of these full-body kinesthetic, vestibular, and tactile experiences appears to be organizing to the CNS. In addition, this repetition is important to the child’s development of balance, coordination, and motor planning. Hence, the occupational goal of movement and exploration becomes the means for development of multiple performance areas.

In the first year, the goal of an infant’s social play is attachment, or bonding, to the parents). As described by Greenspan, this is a period in which the infant falls in love with the parents and learns to trust the environment because of the care and attention provided by the parents or caregivers.54 These occupations are critical foundations to later occupations that involve social relating and demonstration of emotions. At 1 year of age, infants play social games with parents and others to elicit responses. Although infants at this age engage readily with individuals other than family, they require their parents’ presence as an emotional base and return to them for occasional emotional refueling before returning to play.105

By the second year, children exhibit social play in which they imitate adults and peers. Imitation of others is a first way to interact and socially relate. Both immediate and deferred imitation of others are important to social play as children enter preschool environments and begin to relate to their peers.

Performance Skills

Sensory and Motor Skills: The newborn can interpret body sensations and respond reflexively. He enjoys and needs a consistent caregiver’s physical contact and tactile stimulation. The neonate turns his head when touched on the cheek, relaxes in his mother’s arms, and expresses discomfort from a wet diaper. Self-regulation of sleep-wake cycles, feeding, and display of emotions and arousal emerge in early infancy. The infant molds himself to the parents’s embrace, clinging to the parent’s arms and chest. The newborn’s vestibular system is also quite mature as he calms from rocking and enjoys the motion of a parent walking him about the room. The neonate demonstrates orientation and attention to visual, auditory, and tactile stimuli. An important fact is that the newborn also exhibits habituation, or the ability to extinguish incoming sensory information (e.g., ability to sleep by blocking out sound in a noisy nursery).

Gross motor activity begins prenatally in response to vestibular and tactile input inside the womb. The first movements of newborns appear to be reflexive; however, on closer examination, they reveal the ability to process and integrate sensory information. The neonate’s motor responses contribute to perceptual development and organization. In the first month of life, the infant moves the head side to side when in a prone position and rights the head when supported in sitting. By 4 months, the prone infant lifts the head to visualize activities in the room. This ability to lift and sustain an erect-head position appears to relate to the infant’s interest in watching the activities of others, as well as improved trunk strength and stability. As the infant reaches 6 months, he or she demonstrates increased ability to lift the head and trunk when in a prone position to visualize the environment when prone. The infant can also move side to side on the forearms, then the hands, and can lift an arm to grasp a toy (Figure 3-4). When supine, the child actively kicks and brings the feet to the mouth. Over the next 6 months, this dynamic, postural stability prepares the infant to become mobile.

FIGURE 3-4 Inprone position, the infant shifts his weight from side to side when playing with toys; later he learns to pivot while prone to expand where he can reach and what he can visualize.

Rolling is normally the infant’s first method of becoming mobile and exploring the environment. Initially, rolling is an automatic reaction of body righting; usually the infant first rolls from the stomach to the side and then from the stomach to the back. By 6 months, the infant rolls sequentially to move across the room. Heavy or large babies may initiate rolling several months later, and infants with hypersensitivity of the vestibular system (i.e., overreactivity to rotary movement) may avoid rolling entirely.

Most infants enjoy supported sitting at a very early age. As their vision improves in the first 4 months, they become more eager to view their environment from a supported sitting position. The newborn sits with a rounded back; the head is erect only momentarily. Head control emerges quickly. By 4 months, the infant can hold the head upright with control for long periods, moving it side to side with ease. Most 6-month-old infants sit alone by propping forward on the arms, using a wide base of support with the legs flexed. However, this position is precarious, and the infant easily topples when tilted. Many 7-month-old infants sit independently. Often their hands are freed for play with toys, but they struggle to reach beyond arm’s length.

By 8 to 9 months, the infant sits erect and unsupported for several minutes. At that time, or within the next couple of months, the infant may rise from a prone posture by rotating (from a side-lying position) into a sitting position. This important skill gives the infant the ability to progress by creeping to a toy and then, after arriving at the toy, to sit and play. By 12 months, the infant can rise to sitting from a supine position, rotate and pivot when sitting, and easily move in between positions of sitting and creeping (Figure 3-5).

FIGURE 3-5 A, In dynamic sitting, the infant has sufficient postural stability to reach in all directions. B, By 10 months, the infant easily moves into and out of sitting positions.

After experimenting with pivoting and backward crawling in a prone position, the 7-month-old infant crawls forward. He or she may first attempt belly crawling using both sides of the body together. However, reciprocal arm and leg movements quickly emerge as the most successful method of forward progression. Crawling in a hands-and-knees posture (sometimes called creeping) requires more strength and coordination than belly crawling. The two sides of the body move reciprocally. In addition, shoulder and pelvic stability are needed for the infant to hold the body weight over the hands and knees. Mature, reciprocal hands-and-knees crawling also requires slight trunk rotation (Figure 3-6). Through the practice of crawling in the second 6 months of life, the child develops trunk flexibility and rotation. Most 10- to 12-month-old infants crawl rapidly across the room, over various surfaces, and even up and down inclines.

FIGURE 3-6 Crawling on all fours allows the infant to explore new spaces. This form of mobility increases shoulder and pelvic stability for upright stance and promote the rotational patterns needed for ambulation. From Henderson, A., & Pehoski, C. [2006]. Hand function in the child: Foundations for remediation [2nd ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.

Infants at 5 and 6 months delight in standing, and they gleefully bounce up and down while supported by their parents’ arms. The strong vestibular input and practice of patterns of hip and knee flexion and extension are important to the development of full upright posture after 1 year. The young infant also prepares for a full upright posture by standing against furniture or the parent’s lap. A 10-month-old infant practices rising and lowering in upright postures while holding onto the furniture. By pulling up on furniture to standing, the infant can reach objects previously unavailable. This new level of exploration and increase in potential play objects motivates infants to practice standing and motivates parents to place breakable objects on higher shelves (Figure 3-7). At 12 months the infant learns to shift the body weight onto one leg and to step to the side with the other leg. The infant soon takes small steps forward while holding onto furniture or the parent’s finger.

The infant’s first efforts toward unsupported forward movement through walking are often seen in short, erratic steps, a wide-based gait, and arms held in high guard. All these postural and mobility skills contribute to the infant’s ability to explore space and obtain desired play objects. By 18 months, the infant prefers walking to other forms of mobility, but balance remains immature, and the infant falls frequently. He or she continues to use a wide-based gait and has difficulty with stopping and turning. Infants remain highly motivated to practice this new skill, however, because walking brings new avenues of exploration and a sense of autonomy, and the parent must now protect the infant from objects that previously could not be reached and from spaces that have not yet been explored.

The newborn moves the arms in wide ranges, mostly to the side of the body. In the first 3 months, the infant contacts objects with the eyes more than with the hands. By 3 months, he follows his mother’s face in a smooth arc, crossing midline. As early as 1 to 2 months, an infant learns to swipe at objects placed at his or her side. This first pattern of reaching is inaccurate, but by 5 months, the accuracy of reaching towards objects increases greatly.91 The infant struggles to combine grasp with reach and may make several efforts to grasp an object held at a distance. As postural stability increases, the infant also learns to control arm and hand movements as a means of exploring objects and materials in the environment. By the time an infant is 6 months old, direct unilateral and bilateral reaches are observed, and the infant smoothly and accurately extends the arm toward a desired object.108

Grasp changes dramatically in the first 6 months (Figure 3-8, A and B). Initially, grasping occurs automatically (when anything is placed in the hand) and involves mass flexion of the fingers as a unit. The object is held in the palm rather than distally in the fingers or fingertips. Three- to 4-month-old infants, therefore, squeeze objects within their hands, and the thumb does not appear to be involved in this grasp. At 4 to 5 months, the infant exhibits a palmar grasp in which flexed fingers and an adducted thumb press the object against the palm (Figure 3-8, C). At 6 months, the infant uses a radial palmar grasping pattern in which the first two fingers hold the object against the thumb. This grasp enables the infant to orient the object so that it can be easily seen or brought to the mouth (Figure 3-8, D). The infant secures small objects using a raking motion of the fingers, with the forearm stabilized on the surface.

FIGURE 3-8 A, Grasping patterns evolve from palmar grasps without active thumb use to radial digital grasps as in B. C, At 4 months, the infant holds the object tight against the palm, with all fingers flexing as a unit. D, At 8 months, the infant holds objects in the radial digits. A and B from Henderson, A., & Pehoski, C. [2006]. Hand function in the child: Foundations for remediation [2nd ed.]. St. Louis: Mosby.

Grasp continues to change rapidly between 7 and 12 months.14,27 A radial digital grasp emerges in which the thumb opposes the index and middle finger pads. At approximately 9 months, wrist stability in extension increases, and the infant is better able to use the fingertips in grasping (e.g., the infant can use fingertips to grasp a small object, such as a cube or cracker). By holding objects distally in the fingers, the infant can move the object while it is in the hand; movement of objects within the hands allows the infant to explore them and use objects for functional purposes. A pincer grasp, with which the infant holds small objects between the thumb and finger pads, develops by 10 to 11 months. The 12-month-old infant uses a variety of grasping patterns, often holding an object in the radial fingers and thumb. The infant may also grasp a raisin or piece of cereal with a mature pincer grasp (i.e., one in which the thumb opposes the index finger).

In the second year of life, grasping patterns continue to be refined. The child holds objects distally in the fingers, where holding is more dynamic. By the end of the second year, a tripod grasp on utensils and other tools may be observed. Other grasping patterns may also be used, depending on the size, shape, and weight of the object held. For example, tools are held in the hand using first a palmar grasp and then a digital grasp. Blended grasping patterns develop toward the end of the second year, allowing the child to hold a tool securely in the ulnar digits while the radial digits guide its use.

Voluntary release of objects develops around 7 and 8 months. The first release is awkward and is characterized by full extension of all fingers. The infant becomes interested in dropping objects and practices release by flinging them from the high chair. By 10 months, objects are purposefully released into a container, one of the first ways the infant relates separate objects. As the infant combines objects in play, release becomes important for stacking and accurate placement. For example, the play of 1-year-old children includes placing objects in containers, dumping them out, and then beginning the activity again.

Between 15 and 18 months, the infant demonstrates release of a raisin into a small bottle and the ability to stack two cubes. Stacking blocks is part of relational play, because the infant now has the needed control of the arm in space, precision grasp without support, controlled release, spatial relations, and depth perception. The infant can also place large, simple puzzle pieces and pegs in the proper areas. At the same time, the infant acquires the ability to discriminate simple forms and shapes. Therefore, the infant’s learning of perceptual skills is supported by improved manipulative abilities, and increased perceptual discrimination promotes the infant’s practice of manipulation.82 Perception of force increases, enabling the infant to hold an object with the just-right amount of pressure (e.g., so cookies are not crushed before eaten).

The complementary use of both hands to play with objects develops between 12 months and 2 years. During this time, one hand is used to hold the object while the other hand manipulates or moves the object. It is not until the third year that children consistently demonstrate use of two hands in simultaneous, coordinated actions (e.g., using both hands to string beads or button a shirt).36

Cognitive Skills: In the first 6 months, the infant learns about the body and the effects of its actions. Interests are focused on the actions with objects and the sensory input these actions provide. The infant’s learning occurs through the primary senses: looking, tasting, touching, smelling, hearing, and moving. The infant enjoys repeating actions for their own sake, and play is focused on the action that can be performed with an object (e.g., mouthing, banging, shaking), rather than the object itself.67 By 8 to 9 months, the infant has an attention span of 2 to 3 minutes and combines objects when playing (e.g., placing favorite toy in a container). At this age, children begin to understand object permanence; that is, they know that an object continues to exist even though it is hidden and cannot be seen.23 They can also find a hidden sound and actively try to locate new sounds.

By 12 months, the infant’s understanding of the functional purpose of objects increases. Play behaviors are increasingly determined by the purpose of the toy, and toys are used according to their function. The infant also demonstrates more goal-directed behaviors, performing a particular action with the intent of obtaining a specific result or goal. Tools become important at this time, because the infant uses play tools (e.g., hammers, spoons, shovels) to gain further understanding of how objects work. At the same time, the infant begins to understand how objects work (e.g., how to activate a switch or open a door).

In the second year, the child can put together a sequence of several actions, such as placing small “people” in a toy bus and pushing it across the floor. The sequencing of actions indicates increasing memory and attention span. Some of the first sequential behaviors illustrate the child’s imitation of parent or sibling actions; therefore, increased ability to imitate and increased play sequences appear to develop concurrently (Figure 3-9).

Social Skills: The infant’s emotional transition from the protective, warm womb to the moment of birth is a dramatic change. The primary purpose of the newborn’s system is to maintain body functions (i.e., the cardiovascular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal systems). However, as the infant matures, the focus shifts to increasing competence in interaction with the environment. The sense of basic trust or mistrust becomes a main theme in the infant’s affective development and is highly dependent on the relationship with the primary caregivers. According to Erikson, the first demonstration of an infant’s social trust is observed in the ease with which he or she feeds and sleeps.35

The basic trust relationship has varying degrees of involvement. Parent-infant bonding is not endowed but is developed from experiences shared between parent and child over time. These feelings are seen in the progression of physical contact between parent and infant. The infant shows a differentiated response to the parent’s voice, usually quieting and calming. Although infants are capable of crying from birth, they begin to express other emotions by 2 months, such as smiling and laughing.

By 5 to 6 months, the infant becomes very interested in a mirror, indicating a beginning recognition of self. By 4 to 5 months, he or she vocalizes in tones that indicate pleasure and displeasure. In the second year of life, the parents (or caregivers) remain the most important people in the child’s life. The 2-year-old infant likes to be in constant sight of the parents and expresses emotions by hugging and kissing them.

Although toddlers practice their autonomy around parents, they have no intention of giving up reliance on them and may become upset or frightened when the parents leave. Two-year-old children are interested in other children, but they tend to watch them rather than verbally or physically interacting with them. In a room of open spaces, these children are likely to play next to each other. Their side-by-side play often involves imitation, with few verbal acknowledgments of each other.

Contexts of Infancy

Cultural Contexts: The family’s cultural beliefs and values influence caregiving practices and determine many of the child’s earliest experiences. For example, feeding and co-sleeping practices both influence the infant’s development. Breast feeding and bottle feeding practices vary in different cultures and ethnic groups. Although practices vary in the United States, European American mothers tend to breast-feed for the first 6 months. Mothers often establish a feeding schedule, separating feedings by longer intervals as the infant matures. African American families expect the infant to make the transition to table food quickly, and infants generally eat only table food by 1 year.113 In contrast, Chinese and Filipino infants are often breast-fed on demand until 2 to 2½ years of age.17,18 These parents are often very attentive, carrying and holding their infants throughout the day, even during naps. When the infants are not held, they are kept nearby and picked up immediately if they cry.18 In many countries, children are fed certain foods as medicine, that is, to improve health or prevent illness. For example, in the Middle East, infants are given tea and herbal mixtures to prevent or cure illness, and a dietary balance of hot and cold foods is believed to be essential to good health.95