Foundations for Occupational Therapy Practice with Children

1 Explain the history and evolution of theories pertaining to child development.

2 Define the term occupation and describe the study of occupation with emphasis placed on the occupations of children.

3 Explain what is meant by person–environment congruence.

4 Articulate the concepts and principles that define family-centered services.

5 Explain the developmental and learning theories of the early and middle 1900s, which provided the foundation for occupational therapy theories.

6 Explain and apply cognitive models of practice.

7 Use a dynamic systems approach to explain how children develop motor skills.

8 Explain how the person-environment-occupation model is used with other specific models of practice in occupational therapy intervention with children.

9 Describe and apply learning theories and approaches.

10 Define and explain the appropriate use of and evidence for neurodevelopmental and sensory integration therapy approaches.

11 Describe strategies that exemplify each practice model using client examples.

12 Compare and contrast intervention activities derived from different theoretical approaches and practice models.

Occupational therapists have developed and used theory as the basis for professional practice for many years. Early developers of occupational therapy focused on the theories of occupation and the use of time.124,172 As stated by Meyer,

Our conception of man is that of an organism that maintains and balances itself in the world of reality and actuality by being in active life and active use, i.e., using and living and acting its time in harmony with its own nature and the nature about it. It is the use that we make of ourselves that gives the ultimate stamp to our [being] (p. 64).124

Meyer posited that humans maintain rhythms of work, play, rest, and sleep that need to be balanced and that “the only way to attain balance in all this is actual doing, actual practice” (p. 64).124 Current practices build on many of the original concepts of the profession’s founders. Meyer’s words are echoed by those of Mandich and Rodger, who explain that through “doing and participation in everyday occupations, children learn and master new skills” (p. 115).117 Furthermore, social engagement (doing with family and friends) enables children to develop a sense of belonging and self-esteem that contributes to health and well-being. Since the time of Meyer, occupational therapists have continued to develop models of practice based on an understanding of humans as occupational beings. They have also integrated the theories and science of psychologists, neuroscientists, and other disciplines into their practices. This chapter describes current occupational theories, models of practice that reflect those theories, and concepts from other disciplines that support occupational therapy practices.

This chapter begins with a brief overview of the historical and current perspectives on the theories that underlie current service provision: development, occupation, and environment. Foundational theories for occupational therapy practice are discussed next. Then, an overall framework for occupational therapy practice with children, based on a person-environment-occupation (PEO) perspective, is presented, followed by descriptions of current models of practice and the interventions that exemplify those models. Finally, these models of practice are applied to specific practice scenarios, demonstrating the interconnection of theories, models of practice, assessment, and interventions.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY PRACTICE WITH CHILDREN

In one version of an ideal childhood, summer is remembered as a time when friends spent the entire day playing outside. Children moved from activity to activity as a group, enjoying one another’s company and participating in a variety of play activities. Life was about running with the dog, playing tag in the woods, climbing trees, playing ball in the alley, and pretending to be a superhero or a princess. Adults often have fond memories of their childhood days. As children, however, they did not think about the reasons they engaged in play activities or why particular activities were enjoyable—it was just fun! Occupational therapists, however, have a different perspective on play.

Play is considered a primary occupation of childhood. Multiple, interrelated factors within the child, family, and environment influence a child’s ability to engage in play, and a child’s play actions become a window for understanding how the child interacts with his environment. Occupational therapists understand that play is essential for development, and they study the concepts and assumptions that underlie the theories of play. It is through play that children learn to adapt to their environments and to develop competencies.155 By playing, children develop skills that they will later employ in work settings. Children with disabilities face challenges to play. Children with disabilities may exhibit less playfulness (see Chapter 18), demonstrate lower levels of physical play,151 and require more support to play.22,175 Play is also a means to the development of other functions (e.g., motor, social, cognitive, and self-care skills).142 Play activities are generally central to an occupational therapy session because these activities engage and motivate the child, elevating his or her focus and performance.

Parham explains that play “is an active ingredient of a healthy lifestyle” and prepares a person for work.147,154 As a child undergoes transition to adolescence and adulthood, this primary occupation of play evolves into the occupations of adulthood—work, activities of daily living, and leisure.

Play theories are but one set of theories applied by occupational therapists, who use theories in a variety of ways as a foundation to their reasoning. Therapists make decisions and select strategies using their synthesized knowledge of practice theories, including evidence for those theories, their own experiences, and their perceptions of the client’s priorities. Through the use of theory, assessment, and professional reasoning, occupational therapists hypothesize and then develop interventions to improve the occupational performance of children.

For purposes of this chapter, a theory is defined as a set of facts, concepts, and assumptions that together are used to describe, explain, or predict phenomena. Using theory, occupational therapists organize knowledge, understand observations, and explain or predict occupational function and dysfunction. Theories, therefore, provide a guide or rationale for occupational therapy intervention. Theories form the foundation for models of practice that guide the day-to-day delivery of occupational therapy services. A model of practice (also called a frame of reference) is the practical expression of theory and provides therapists with specific methods and guidelines for occupational therapy intervention. Models of practice draw from one or more theories and use concepts and assumptions to delineate the specific details of an occupational therapy practice, including who receives intervention, what intervention strategies are used, and when and where intervention is provided. The model of practice a practitioner applies can define the evaluations used, the intervention focus and strategies, and expected outcomes. It is the responsibility of the profession to research the theories and models of practice that are core to its practice; this chapter also explains the role of evidence-based practice in the development and application of theory-based models of practice.

Concepts Influencing Occupational Therapy Practice with Children

Perspectives on development and occupation have changed over the past century with changes in our knowledge about children, the factors affecting their development, and their basic need for engagement in purposeful tasks and activities. Developmental theories focus on explaining the processes by which infants mature and gain skills to become fully functioning adults. At the core of developmental theories is an explanation of the relationship between human biologic capacity and maturation and the influence of the environment on the behavior and performance of the individual. In fact, developmental theories tend to be distinguished from each other by the relative weight given to these two factors, nature or nurture, or by the emphasis on a particular aspect of human biologic function or environment. The theories of Gesell emphasized the genetic and biologic determinants of development; however, more recent theories (e.g., Piagetian theories) focus on interaction of biologic and environmental determinants of behavior.70 In current times, developmental theorists generally agree that human development is both the process and the product of biologic maturation and environmental experiences.

Development may be defined as the sequential changes in function that occur with maturation of the individual or species. These sequential changes should be differentiated from the concept of growth, which refers to maturational changes that are physically measurable. In the past, different dimensions of development have been emphasized. For example, longitudinal development focuses on the stages of development, whereas hierarchical development focuses on the prerequisite skills needed for higher-level skills. Evolving views and theories of development place less emphasis on the stages and components of development and more on the person as a whole and his or her development in relation to environment, roles, and occupations.84 The emerging theories of person–environment relations and complex systems have influenced these changes. Developmental theories are further explained later in the chapter.

Participation in Occupations

Throughout the 1920s and into the 1930s, the focus of occupational therapy was the development of the idea of occupation as a cure for disease and disability. The occupations best suited to cure specific medical problems were identified. Dunton led an effort to analyze occupations systematically.60 Occupational therapists used the principles of graded, purposeful activity and a balance of work, rest, and play as the basis for treatment methods.122,172

In the 1940s, changes in the medical arena (e.g., the discovery of antibiotics and the advancement of specific medical and surgical techniques) had a tremendous influence on the way in which occupational therapists used occupation in treatment. The development of specific techniques increased, and more focus was placed on programs addressing activities of daily living. Occupational therapy treatment focused on the prescription of activities with specific aims.87 For example, the flexion-extension-pronation-supination (FEPS) loom was developed to ensure that targeted ranges of movement were achieved. As a result of these changes, treatment became “medicalized.” In other words, the focus of occupational therapy became a series of technical activities rather than purposeful occupation. The influence of the medical model on the profession dominated for three decades and remains a predominant influence today.

As the 1960s ended, occupational therapists were increasingly uncomfortable with the technical focus of their profession. There was a call for more emphasis on the development of theory and a renewed interest in the roots of the profession: occupation.203 During this time, Reilly described a theory of occupational behavior in which the individual strives to develop skills and competencies directed toward mastery and achievement.153,156 Work and play were viewed as the contexts in which these skills and competencies developed. Fidler and Fidler focused on the importance of purposeful activity, or doing, in the development of self and the prevention of dysfunction.65 Kielhofner and Burke, building on Reilly’s work, described a model of human occupation that incorporated a systems theoretical view of the nature of occupation.91 This model expanded the understanding of life roles and the powerful influence they have on daily life and health.

In the past 20 years, a specific academic discipline called occupational science became a basis of occupational therapy.204 Study of the human as an occupational being is essential to an understanding of the complexity of engagement in occupation and the relationship between occupation and human health. As noted by Parham, “A full understanding of occupation requires the integration of knowledge from many disciplines, such as philosophy, biology, psychology, sociology, and anthropology” (p. 25).142 Wilcock emphasized occupation as purposeful activity and explained that humans need to use time in a purposeful way in order to develop and flourish.195

As the study of occupation has developed, occupational therapy scholars have proposed definitions of occupation. Clark and colleagues defined occupations as “chunks of daily activity that can be named in the lexicon of the culture” (p. 301).36 Christiansen, Clark, Kielhofner, and Rogers defined occupation as the “ordinary and familiar things that people do every day” (p. 1015).34 The definition adopted by the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT) states that “occupation refers to a group of activities and tasks of everyday life, named, organized, and given value and meaning by individuals and a culture” (p. 34).30

Each definition refers to daily activities or “chunks” of activity. Because occupation references daily activity, it is often thought of as simple; that is, the basic activities that people perform each day to look after themselves, to be productive, and to enjoy life. The definition of occupation becomes more complex with the inclusion of its meaning or purpose. The meaning of an occupation for an individual or the value of an occupation determined by a culture begins to show the many layers of occupation and the central relationship of occupation to the human experience.

Participation in occupations meets a basic human need.30 Dunton expressed his belief that occupation is as necessary to life as food and drink.60 Occupation also is an important determinant of health. Health can be strongly influenced by a person’s engagement in meaningful occupations, and conversely, the absence of meaningful occupation can have dire health consequences.196 Occupation serves as a means of organizing time, space, and materials. Patterns, habits, and roles evolve through the organization of occupation.90 Occupations change over the lifespan (as do patterns of time use), representing occupational development.

Play is a key area of occupational focus in practice with children. Chapter 18 describes occupational therapy perspectives on play. Most of the focus in the occupational therapy literature has been on play as a means and an end: as a therapeutic medium (a means to developmental change) and as an indication of developmental level (an outcome of intervention).142 Therefore, play elicits more than enjoyment; it is also a catalyst to the development of motor or cognitive skills. In their survey of pediatric occupational therapists, Couch, Deitz, and Kanny found that pediatric occupational therapists most often use play in therapy as a medium for developing both the skills underlying function (e.g., understanding cause-and-effect relationships, exploring an object by manipulating it) and an understanding of the rules that guide behavior (e.g., taking turns).42 Occupational therapists often observe children’s play and play with them to determine their level of performance and to analyze their performance (Figure 2-1).104 Less often, but probably more importantly, therapists view play as a priority outcome of interest, the end rather than the means. Parham suggested that therapists must understand that “play is a legitimate end in itself because it is a critical element of the human experience” (p. 24).142 Play is therefore a quality-of-life issue that promotes health and well-being.

In a similar way, occupation has a dual role in the profession, as both the focus of intervention and the medium through which occupational therapists often intervene. For example, a child may be struggling at school to successfully fulfill his role as a student because he has Asperger’s syndrome. The student struggles with his academic occupations because he is anxious and overaroused. His social participation is limited because he has limited ability to read the social cues of his peers. The occupational therapist evaluates the school activities in which this child is expected to participate and determines the personal and environmental factors that are influencing the child’s performance. These occupations become the focus of intervention; for example, the occupational therapist helps the teacher make accommodations to the classroom environment to decrease the student’s overarousal and improve his concentration in class. The occupational therapist also helps the student interpret social cues and gestures. The therapist models and instructs the student in appropriate social responses and creates opportunities for him to interact with peers with therapist support. Scaffolding the child’s participation in social activities with peers at school is likely to develop skills that generalize to other opportunities for social participation. This brief example illustrates intervention principles that enable children’s participation in everyday occupations (Box 2-1).96

The goal of an occupation-based model of practice is the child’s achievement of optimal occupational performance. What do professionals know about the occupational performance of children with special needs? According to the National Health Interview Survey of 1992 to 1994, 6.5% of children in the United States with disabilities are limited to some degree in their participation in daily activities.135 The study investigators reported that children with physical disabilities are “two to three times more likely to be unable to perform their usual activities than children with other conditions (e.g., asthma)” (p. 612).135 Children with special needs also have lower rates of participation in ordinary daily activities.173 Researchers have documented that children with disabilities are more restricted in active recreation and community socialization activities.16 Specifically, Bedell and Dumas found that children with acquired brain injury were most restricted in participating in structured community events, managing daily routines, and socializing with peers and they were least restricted in physical mobility.17

Australian studies113 and Canadian studies101 have found an inverse relationship in children with disabilities between amount of physical activity and age, with a significant decline in active leisure participation from childhood to adolescence. Although healthy children are less physically active as adolescents, they continue to participate in a wide range of leisure activities. In contrast, adolescents with disabilities engage in fewer leisure and social activities, and their activities tend to be more often home-based than community-based.168 See Chapter 4 for a discussion of adolescent participation.

In their systematic review of studies of leisure activities in children and youth with physical disabilities, Shikako-Thomas et al. found that children with disabilities participate more in informal activities (e.g., those activities that require little or no planning and are often self-initiated [reading, playing with toys]) than in formal activities (e.g., those with a formally designated coach or instructor [music or art lessons, organized sports]).168

Both intrinsic (personal) and environmental (family and community) factors influence the diversity of activities and the intensity of participation. The intrinsic factors include motor function,140 personality, social skills, age, and gender. Girls tend to participate more in arts and social activities, and boys participate more in group activities involving physical activity and sports.61,168 Family support can have a positive or negative effect. Children’s activities may be restricted by family time constraints, financial burden, and lack of supportive mechanisms (e.g., babysitting).101 Participation for children with disabilities is positively influenced by high levels of family cohesion, high incomes, strong family coping skills, and low levels of stress.101,168 Community barriers to children’s participation include barriers to physical access, lack of programming, and negative attitudes. Clearly, encouraging participation in the typical activities of childhood needs to be the major focus of pediatric occupational therapy.

Environment

Human ecology is the study of human beings and their relationships with their environments. Environments are the contexts and situations that occur outside individuals and elicit responses from them, including personal, social, institutional, and physical factors. Environmental factors can facilitate or limit engagement in occupation. A concept prevalent in the human development literature and more recently in health care is person–environment congruence, or environmental fit, which is described as the congruence between individuals and their environments.176

Over the past two decades, occupational therapists have stressed the importance of the interaction between individual and environment. Specific models of practice have been developed with a focus on environment.57,99 Systems theory, emphasizing the interdependent relationship between individual and environment, forms the basis for concepts that define occupational therapy and models of practice. Primary models of practice address the environment in terms of its cultural, social, institutional, and physical dimensions and the transactional relationship between people and the environments in which they live, work, and play.158,204

Psychologists who created theories and models about the relationship between humans and their environments that have influenced occupational therapy include Bronfenbrenner,25 E. Gibson,71 and J. Gibson.72 Bronfenbrenner, with a background in developmental psychology, studied how the child’s social and cultural environments influenced development.25 He believed that an interdependent relationship exists between a person and his or her social and cultural environments. Different levels of social support and social interactions surround the individual, including informal (e.g., family and friends) and formal (e.g., occupational therapists and teachers). Levels of the environment are defined by their proximity to the individual; that is, family is most important, then friends and extended family, and then the community and society. Children interact with and are influenced by all levels of the social environment. Changes at any level of the environment influence a person’s behavior. Throughout his or her life, a person constantly adapts to and influences changes in his or her social environments.

According to Bronfenbrenner’s theories of social development, occupational therapists are part of a person’s social environment.25 These theories help the therapist understand lifespan changes in clients in the context of their social settings. The interdependence between a person and the social environment helps therapists to expand intervention strategies to include families and communities.

Ecologic psychologists E. Gibson and J. Gibson considered the interdependence of a person with his or her environment to be an explanation of perceptual development. E. Gibson understood that manipulative play had a key role in the infant’s cognitive development.71 She believed that the child’s intrinsically motivated exploratory actions lead to perceptual, motor, and cognitive development through the concept of affordance. An affordance is a quality of an object or an environment that allows an individual to perform an action. Action and perception are tightly linked: the child’s first actions are to gather new information about the environment and those actions form the basis for perceptual development (the child’s understanding of the environment). “As new action systems mature, new affordances open up and new experiments on the world can be undertaken” (p. 7).71 As explained by E. Gibson:

The young organism grows up in the environment (both physical and social) in which his species evolved, one that imposes demands on his actions for his individual survival. To accommodate to his world, he must detect the information for these actions—that is, perceive the affordances it holds. How does the infant creature manage this accomplishment? … I think evolution has provided him with action systems and sensory systems that equip him to discover what the world is all about. He is “programmed” or motivated to use these systems, first by exploring the accessible surround, then acting on it … extending his explorations further. The exploratory systems emerge in an orderly way that permits an ever-spiraling path of discovery. The observations made possible via both exploratory and performatory actions provide the material for his knowledge of the world—a knowledge that does not cease expanding, whose end (if there is an end) is understanding (p. 37).71

Successful adaptation to the environment occurs when a person matches his or her activities to the affordances of the environment or when the person modifies the environment to ensure successful completion of an activity.

The Gibsons’ theories emphasize the importance of understanding a child’s development in the context of daily surroundings and activities. Occupational therapists are encouraged to provide activities (based on their understanding of the activity’s inherent affordances) that allow a child to explore and learn about the environment, enabling achievement of the child’s goals. Figure 2-2 demonstrates an infant’s motivation to explore.

Risk and Resilience

Several theories and research programs have been developed to explain the ways the environment influences the developmental outcomes of children and adolescents. Most of this work focuses on the participation of children and youth in everyday activities and on factors that either place children and adolescents at risk for poor outcomes or help them achieve optimal outcomes. For example, psychologist Emmy Werner studied the people of Kauai for more than 40 years. Her research indicated that participation in extracurricular activities plays an important role in the lives of resilient adolescents, especially when they participate in cooperative activities.192

Resilience can be defined as the characteristic of an individual who achieves a positive outcome in the context of risk, or factors known to be associated with negative outcomes. Research on risk and resilience has attempted to explain why some children have better outcomes than others who were raised in similar circumstances. The study of resilience has implications for increasing understanding of child development and for developing new interventions to improve outcomes for children at risk. When the concept of resilience was first studied, it was believed to be a stable personality characteristic, such as temperament or IQ. If resilience were an internal, stable characteristic, it would explain why one child did better than another in a particular environment. Currently, researchers understand resilience to be a dynamic process that is refined over time through ongoing transactions between a child and the environment.110

What are the risk factors for children who receive occupational therapy? Often the disability is not a primary risk; however, it can add to cumulative risk when the family has socioeconomic disadvantage, negative parental relationships, parental mental illness or physical illness, and lack of extended family support. Emerging evidence indicates that it is the total number of risk factors to which a child is exposed and the resources available to promote resilience for that child that ultimately are predictive of the child’s vulnerability to future adverse events and developmental outcomes.62,163

Protective factors are defined as characteristics of the child, family, and wider environment that reduce the negative effect of adversity on the child.120 These protective factors may be specific to the risk factor; for example, having warm and loving parents is a protective factor in early childhood, but may not serve as a protective factor when the child become an adolescent and is more influenced by peers and the teen culture. Researchers such as Rutter162 and Garmezy68 have identified general protective factors related to the child, the family milieu, and the social environment. Understanding these general protective factors may be helpful in designing interventions for at-risk children. Child protective factors include strong self-esteem and positive communication skills.68,192,193 Other child attributes that are associated with positive outcomes include intelligence, emotion regulation, temperament, coping strategies, and attention.184 Children who can effectively process information and problem-solve can use these abilities in adverse situations. Children who can regulate their emotions can monitor and modify the intensity and duration of their emotional reactions, enabling them to better function at school and in social relationships. An easygoing temperament is also a protective factor because it may evoke more positive attention from adults. Coping skills are also important because children with strong coping skills can moderate the impact of a difficult situation.

Essential resources that lead to resilience in the child are family resources such as love, nurturance, and a sense of safety and security. These must be accompanied by material resources such as nutrition and shelter.184 Attributes of the family that influence positive outcomes include family cohesion and harmony.68 Researchers have shown that a high-quality relationship with at least one parent, characterized by high levels of warmth and openness and low levels of conflict, is associated with positive outcomes across level of risk and stages of development.109

Protective factors in the community also contribute to the child’s development. Neighborhood quality, youth community organizations, quality of school programs and after-school activities can all influence a child’s ability to cope with risk factors and overcome adversity.184 Attributes of the social environment that promote resilience include extended social support and availability of external resources.68 Environmental factors, such as family-centered service delivery, acceptance of community attitudes, supportive home environments, and mentoring relationships with adults, have been shown to have a positive influence on child development.157,189,193

Family-Centered Service

During the past 20 years, families of children with disabilities have increased their role in determining and implementing services for their children. Families have been leaders in promoting family-centered service, a philosophy of service provision that emphasizes the central role of families in making decisions about the care their children receive. Challenged by the changes in the health services field and an increased demand by consumers for involvement in the services they receive, health care providers have made great strides in implementing family-centered service.

The term family-centered service arose from early intervention programs. Three important concepts define family-centered service: (1) parents know their children best and want the best for their children; (2) families are different and unique; and (3) optimal child functioning occurs in a supportive family and community context. Chapter 5 explains the rationale for and application of family-centered practice.

In family-centered service the family’s right to make autonomous decisions is honored. The relationship between the family and professionals is a partnership in which the family defines the priorities for intervention and, with the service providers, helps direct the intervention process.59 In working with families, service providers emphasize education to enable parents to make informed choices about the therapeutic needs of their child. Comprehensive education about services and community resources can help families understand the disability, acquire tools to manage behavior, and develop strategies for obtaining community resources. In family-centered practice intervention is based on the family’s visions and values; service providers recognize their own values and do not impose them on the family. The family’s roles and interests, the environments in which the family members live, and the family’s culture make up the context for service provision. Individualization of both the assessment and intervention processes is essential to family centeredness. Intervention is viewed as a dynamic process in which clients and parents work together as partners to define the therapeutic needs of the child with a disability. Services are designed to fit the needs of the family, rather than to force the family to fit the needs of the service providers or the intervention policies already in place. DeGrace explains that occupational therapy intervention needs to fit into a family daily routine because how a family participates in daily routines “defines who that family is and plays a key role in determining its health” (p. 348).50 Because each family is unique, practitioners need to ask about and learn how each family defines their routines, habits, and values, and to adapt their services to this family-constructed definition.

Research has demonstrated that parents feel more positive about their roles when service providers solicit and value parental participation. Increasing evidence in the literature indicates that interdisciplinary, family-centered service for children with disabilities leads to increased family satisfaction and may lead to greater functional improvement in children with disabilities.114,161 Parents are less likely to act on behalf of their child when practitioners are unresponsive to the family’s needs, are paternalistic, or fail to recognize and accept family decisions.58

Family-centered practice is characterized by appreciation and valuing of the family’s concerns and priorities, family support, and family education. Therapists who practice family-centered care seek information about how the disability impacts family occupations and what occupations are important to the family.51 Other examples of family-centered practice include helping families find social supports and network with other families19 and supporting families in gathering needed resources.77

The findings of a recent survey completed by 494 parents and 324 service providers from children’s rehabilitation centers indicate that parental satisfaction with service is primarily determined by the family-centered culture of the organization and by parental perceptions of family-centered service.100 Families’ satisfaction with services also decreases feelings of distress and depression and improves feeling of wellbeing.92 Occupational therapists who work with children enhance the effectiveness of their services when they practice from a family-centered perspective.

World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health

The World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification system, which is used in the broad rehabilitation and disability arena, influenced the structure of the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework2 and has been used to guide the structure of occupational therapy evaluation. The International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps (ICIDH) was first developed and published in 1980.201 The revised classification system is titled the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF).202 The ICF views human functioning at three levels: the body (structure and function), the person (activities), and society (participation). It also includes the domain of environmental factors, which can have a significant influence on a person’s functioning and health. The ICF model of functioning, disability, and health depicts the dynamic interaction between a person and his or her environment at all levels of functioning. A recent extension of the ICF, the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY) has been developed to address the unique concerns of developing children.107 Recently developed measures align with the ICF and enable practitioners to assess children at multiple levels. The School Function Assessment is an example of scale that rates function at two levels, activities and participation.41 The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) has acknowledged the strong connection between its practice framework and the ICF by establishing the domain of the profession as “supporting health and participation in life through engagement in occupation” (pp. 626-627).2

FOUNDATIONAL THEORIES

Foundational theories form the basis of occupational therapy intervention approaches. These theories come from many fields of study, ranging from the biologic sciences to social sciences to humanities. Occupational therapists draw from a wide range of foundational theories to explain occupational performance. Most theories used by occupational therapists who work in pediatrics are concerned with change. Such theoretical perspectives complement the therapist’s view of human development as growth that occurs over time in the function of an individual or a species. Considering the complex nature of the PEO perspective and the transactions involved in occupational performance, a number of foundational theories are relevant. This section reviews the theories most commonly used by occupational therapists who work with children and adolescents with disabilities.

Developmental Theories

Developmental theories explain and describe the components of a person as they relate to occupational performance. Different theorists have focused on particular components of the individual in an effort to explain developmental function and dysfunction. The most common theories used by occupational therapists are presented.

Piaget and Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget was concerned with the developmental adaptation of the individual in response to ongoing environmental experiences.145 He defined adaptation as the child’s ability to adjust to change to fit into his or her environment, and he examined adaptation through the child’s relationships with human and nonhuman objects and through time and space. Piaget144 introduced the idea that children are intrinsically motivated to learn from their surroundings and that they act on, rather than simply react to, their environment.95 Piaget used the terms cognitive structures, or schema, to describe the way in which children represent objects, events, and relationships in their minds. Piaget viewed every interaction as an opportunity either to assimilate new knowledge into existing structures or to adapt existing structures to accommodate new information. Accommodation is new learning, and it is believed to be the way that the cognitive progress is made. Piaget’s developmental stages have been the focus of research and critique; however, his descriptions of the gradual accumulation of knowledge in specific content areas remain valid concepts in child development.

Piaget believed the child organizes his experiences into mental schemes (concepts) through mental operations. Operations may be defined as the cognitive methods used by the child to organize his or her schemes and experiences to direct his or her actions. The totality of operational schemes available to the child at any given time constitutes the adapted intelligence, or cognitive competence, of the child.

Piaget believed that an invariant, hierarchical development of cognition proceeded from the simple to the complex, from the concrete to the abstract, and from personal to worldly concerns. He specified four maturational levels or periods of cognitive function: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.37,67 He believed that this sequence of development leads to the cognitive maturity of adulthood. The culmination of these levels is a person with values, goals, and plans and an understanding of his or her purpose in society. In current times, most child researchers agree that the child is an active learner, but do not view development in discrete stages.

An understanding of Piaget’s theory is important to occupational therapists who plan programs for children. Regardless of the therapeutic approach used in treatment, the therapist interacts with a thinking child who is continually learning from his environment. It is essential that the selection and structure of an activity be in accordance with the operational skills and concepts of the child.

The primary focus of Piaget’s concept is an explanation of cognitive learning, but Schmidt developed the idea further in the area of motor learning.167 He proposed that motor schemas are formed as combinations of (1) the initial conditions of the movement, (2) the specific parameters used to create it, (3) the knowledge of the results in the environment, and (4) the sensory consequences of the movement. Through repeated experiences, the child abstracts relationships among these four features and is considered to have learned a new movement.

Vygotsky and the Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky viewed human development as historically situated and culturally determined.194 The child develops by internalizing the social interactions that he experiences. Vygotsky was primarily interested in speech and language development; however, his concepts have important applications to child development across domains. Like his predecessors (e.g., Gesell and Piaget) Vygotsky understood that genetics has unequivocal influence on psychological development. However, he recognized that psychological function could only be explained by considering the role of social interaction. Social interaction has a fundamental influence on the child’s development of high mental functions. Vygotsky explained that a child’s cognitive processing first requires the assistance of another being within a social interaction before the child can mentally process on his own. Therefore, cognitive processing is a social process before it is an internal process and a child’s development and learning are critically dependent on social interaction. Vygotsky defined a “zone of proximal development” to explain how learning occurs through social interaction. The zone of proximal development is “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or collaboration with more capable peers” (p. 86).188 What a child can achieve and learn with the assistance of another is the zone of proximal development and defines the area in which adults can work with the child to promote his development and independence in a particular skill.

When an adult and a child experience an activity together, they interpret the objects and events differently. Adults use language to help the child redefine the situation so that adult and child have a shared definition. When a learning opportunity is created that provides an optimal balance between the child’s existing skills and the challenge of the task, the adult can model language and behavior that will help the child progress. Vygotsky’s emphasis on the interactions among a child’s learning, his environment, the type of instruction provided, and his culture was a precursor to many of the dynamic systems models that influence learning theory today.

Vygotsky’s concepts about social learning within the zone of proximal development led to a therapeutic principle called scaffolding. Scaffolding is the process by which therapists or adults support or guide a child’s actions to improve his or her competence. Appropriate guidance is the just right amount of support that enables the child to perform at a higher level. When using scaffolding to facilitate the child’s learning, the adult gradually decreases the amount of support provided such that the child performs more independently. Through this process, actions that are externally supported become internalized. Wertsch makes the point that the child’s help-seeking in an activity can be as important to his learning as receiving that assistance.194 By asking questions and help-seeking, the child becomes more self-directed in his learning; he also develops an understanding about his own learning and how to direct social interactions that can lead to his learning. When the occupational therapist understands a child’s zone of proximal development and perceives methods for scaffolding his learning, she or he can design an optimal activity to promote the child’s learning. Case Study 2-1 presents an example of applying Vygotsky’s theories.

Maslow and the Hierarchy of Basic Needs

Abraham Maslow is generally considered the father of humanistic psychology in the United States.76 He outlined a hierarchy of basic human needs that is believed to follow a longitudinal sequence.118,119 An individual’s most basic needs, those at the base of this hierarchy, are physiologic needs, such as food, water, rest, air, and warmth, that are necessary to basic survival. The next level is characterized by the need for safety, broadly defined as the need for both physical and physiologic security. The need for love and belonging promotes the individual’s search for affection, emotional support, and group affiliation. The need for a sense of self-esteem, which is defined as the ability to regard the self as competent and of value to society, is evidenced as an individual grows. The need for self-actualization, which represents the highest level, is attained through achievement of personal goals.

Maslow proposed that each of these needs serves as a motivator to achieve a higher level of human potential. Throughout development, individuals must satisfy their most basic needs before they are motivated by or interested in other life goals. Foundational biologic and egocentric needs must be satisfied before an individual has social interests and can fully participate in social relationships. With important social relationships established, an individual becomes interested in the broader community and has a broader sense of commitment and responsibility to others within the community. If the lower level needs are not met, the individual is not able to direct his or her energies toward higher levels. For example, a child who comes to school hungry finds it difficult to concentrate on the classroom learning activities. Recognition of a child’s needs and the hierarchy of development of these basic needs helps the occupational therapist understand behaviors that indicate that basic needs are not met and identify needs that should become the focus of goals and interventions.

Learning and Systems Theories

Most important to occupational therapy are theories that integrate concepts about people, their environments, and their occupations. Development has been defined as an “evolution of predictable sequences of interactions between a child and the objects in his or her environment” (p. 446).111 Developmental theories emphasize maturation of the central nervous system as it interacts with the social and physical environment. In addition to maturation, the primary process that results in developmental change is learning.

Learning is the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and occupations through experience that leads to a permanent change in behavior and performance. The basis by which humans are able to learn is neuroplasticity (i.e., the ability of the central nervous system to adapt to and assimilate novel information or tasks). Learning theories foundational to occupational therapy practice models include behavioral theories and social cognitive learning. Dynamic system theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding a child’s development in context. Learning principles and system theories foundational to occupational therapy are discussed in the following section.

Behavioral Theories

The past 60 years have witnessed tremendous progress in the field of learning theories. Early learning theorists, such as Thorndike, emphasized the association between a behavior and the resulting reward or punishment as a simple explanation of behavioral change. Skinner described perhaps the best known learning theory from this era. He believed that the environment shapes all human behaviors and that behaviors may be randomly emitted in response to an environmental stimulus.170 In other words, a person tries a behavior that worked in a previous situation, or an involuntary, reflexive response is elicited by an environmental stimulus. The behavior is then reinforced by the environmental consequences that follow. This sequence—stimulus situation, behavioral response, and environmental consequence—constitutes a contingency of behavior, the mechanism by which the environment shapes behavior.

Skinner stated that through natural occurrences in the environment, a child’s adaptive behaviors are reinforced, and behaviors that are not adaptive are ignored or punished.171 The Skinnerian concept that became fundamental to interventions for children is instrumental or operant learning or the use of reinforcement to modify behavior. Behavior is strengthened and maintained when it results in positive reinforcement (rather than punishment). If reinforcement is absent (i.e., not given) and therefore is negative, positive behaviors may be extinguished.

Skinner believed that all behavior is a result of the environmental control of the individual, culture, and species. He specified that humans, species, and culture are all part of the environment; therefore, they control as much as they are controlled. Problems arise when an environment changes and becomes inconsistent with prior contingency patterns. For example, children use one set of behaviors with their families and another set with friends. Behaviors that are reinforced by friends may bring complaints from or may be ignored by parents. Critics of this theory cite its failure to explain personality traits (e.g., motivation) and cognitive abilities (e.g., imagination and creativity) and its tendency to generalize across age and gender spectrums with no recognition of developmental differences. Chapter 14 provides further explanation of behavioral interventions.

Extensive research has confirmed that when particular behaviors result in specific, consistent consequences, these behaviors can be modified.40 Therapists using a behavioral approach can help a child achieve a higher level of performance through a process called shaping. Shaping involves breaking down a complex behavior into components and reinforcing each behavior individually and systematically until it approximates the desired behavior (Box 2-2).

In recent years, learning and behavioral theories used with young children have evolved into approaches that can be applied broadly across settings. Applied behavioral interventions primarily use operant conditioning in highly controlled environments in which a therapist or teacher gives the child an instruction and then rewards the child for an appropriate response (reinforcement). Applied behavioral interventions are successful in developing skill; however, skills learned in an isolated setting, as in discrete trial training, do not always generalize into new or higher level behaviors across all settings. Educators have developed behavioral approaches that also use Skinner’s framework of instrumental (operant) learning and can be implemented in the child’s natural environment to teach children adaptive behaviors that generalize across environments.94 Educators in early childhood programs have advocated for naturalistic teaching procedures that can be implemented in minimally structured sessions, in a variety of locations and contexts, with a variety of stimuli. Although educators who used naturalistic teaching procedures hold the same developmental goals for children as those who use classical behavioral theory, their procedures are much less structured, incorporate peers, and use naturalistic conditions and reinforcers.43 Two types of these naturalistic learning procedures, incidental teaching and pivotal response training, are frequently used with young children in early childhood programs.

In incidental teaching, a play environment is created to stimulate the young child’s interest and curiosity. It is important that toys used be developmentally appropriate, with both novel and familiar toys. The goal is for the child to select an activity and spontaneously begin to play. The therapist builds on the child’s play selection by expanding the play scenario so that it becomes more challenging or creates a problem for the child to solve. The therapist may cue the child to perform a different action and reward the child for attempting more challenging actions. These teaching sessions take a different approach than do behavioral interventions, which use discrete trial training in which the child is given specific directives and rewarded for a specific response. Table 2-1 compares incidental teaching and discrete trial training.

TABLE 2-1

Comparison of Discrete Trial Training and Incidental Teaching in Early Childhood Programs

| Discrete Trial Training | Incidental Teaching |

| The therapist plans highly structured sessions with planned stimulus and reward. | The therapist plans a loosely structured session with environment designed to elicit specific responses, but directives are not used. |

| The therapist gives instructions to direct the child’s actions. | The child initiates and paces the activity. |

| The training session is generally one-on-one in a clinic or the home. | The session generally takes place in the classroom, child care center, or home, in the child’s natural environment. |

| The same stimuli are used repeatedly. | A variety of stimuli are used. These stimuli are selected from the natural environment. |

| The therapist uses artificial reinforcers and often the same reinforcers. | A variety of reinforcers are used and these are selected from the natural environment. The goal is that these reinforcers be available to the child without the presence of the therapist. |

Adapted from Cowan, R. J., & Allen, K. D. (2007). Using naturalistic procedures to enhance learning in individuals with autism: A focus on generalized teaching within the school setting. Psychology in the Schools, 44, 701-715.

Pivotal response training is also a naturalistic teaching and learning approach used with young children.93 The goal of pivotal response training is to teach children a set of pivotal behaviors believed to be central to learning. The desired outcomes of pivotal response training include increasing (1) the child’s motivation to learn, (2) attention to learning tasks, (3) persistence in tasks, (4) initiation of interactions, and (5) positive affect.115 Procedures that are used in pivotal behavioral training are similar to those used in incidental teaching with emphasis on methods to promote generalization of learning. When applying pivotal response training, the therapist gives the child a choice in play materials, uses natural reinforcers, intersperses mastered tasks with learned tasks, and reinforces attempts at new learning (Figure 2-3).43 These theories are further explained in Chapter 23 on early intervention programs.

Social Cognitive Theories

In general, social cognitive theory explains learning that occurs in a social context. The initial acquisition of highly complex and abstract behaviors was difficult for learning theorists to explain until the advent of the social cognitive theory proposed by Bandura.11 Bandura11 and Piaget144 introduced the idea that children can learn by observing the behavior of others. This learning may not be immediately observed in behavior but becomes part of the child’s general understanding of the world. In contrast with the behavioralists, who believe that all learning produces behavioral change, social cognitive theorists believe that learning can occur without observable behavioral changes. A child can learn by observing the behavior of others, such as subtle nonverbal gestures that are used in conversation. These are observed and stored in memory and may not be demonstrated by the child until a much later time, when the child may exhibit similar gestures but with his or her own unique style.

In social cognitive theory, people determine their own learning by seeking certain experiences and focusing on their own goals. Therefore, children do not simply learn random elements from the environment, but they direct their own learning and are goal oriented in what they learn. Social cognitive theorists also believe that children learn indirectly by observing how their peers’ behaviors are rewarded or punished. Direct reinforcement is not always needed when learning new behaviors.138

Social cognitive learning is often indirect, as when the child learns by observing the consequences of behaviors of those around him or her. Learning that occurs when observing the behaviors of others also depends on the child’s goals, interests, and relationship to those observed. Children’s learning increases when they are given an incentive to learning (i.e., an anticipated valued outcome or reward). Learning is also promoted when the child establishes his or her own goals, is given opportunities to work on those goals, and evaluates whether the goal was accomplished. When children set their own goals, they direct their behavior in a specific way, they are more likely to persist in the behavior to achieve the goal, and they are often more satisfied with the outcome.

In this theory, children learn social skills through group experiences. When children have delayed social skills, they can gain an understanding of social gestures and peer interaction by becoming involved in a group where these behaviors are modeled and rewarded. Bandura believed that critical factors in the child influence the learning process, including the child’s perception of his or her competencies (i.e., self-efficacy). The ways in which a strong sense of efficacy can enhance personal accomplishment are described next.

The Influence of Motivation and Self-Efficacy on Learning

A number of factors in the child are believed to influence learning, such as cognition, motivation, attitude, and self-perception. The relationship between learning and other affective components is complex. It is widely accepted that children’s motivation to perform occupations is influenced by their perceptions of their efficacy, regardless of whether these perceptions are correct.11 If children experience success in learning situations, it is assumed that they increase their perceived competence and internal control, gain support from significant others, and show pleasure at mastering the task. The assumption is made that children are more likely to seek out optimal challenges if they have experienced success.13 The corollary of this theory is that children who experience repeated failure begin to avoid challenges and are less likely to seek out new learning situations.79

Motivation to learn and to achieve is developed through (1) casual attributions, (2) outcome expectancy, and (3) personal goals. When children feel self-efficacious, they attribute any failure to lack of effort. When children feel inefficacious, they attribute their failure to low ability. The efficacious child remains motivated to try harder and to improve performance; the inefficacious child believes that there is no point in trying harder because he or she is destined to fail. A child self-motivates by setting a personal goal higher than his or her current skill levels. Then the child mobilizes the energy to achieve that goal. With success the child sets a higher goal and become motivated to achieve a higher-level task.

Self-efficacy beliefs contribute to motivation in several ways. They determine the goals people set for themselves, how much effort they expend, how long they persevere in the face of difficulties, and how they respond to failure.11 All of these decisions contribute to success in a particular goal and contribute to learning. Perceived self-efficacy also contributes to a child’s coping ability, which is discussed later in this chapter.

Therapists need to be aware of the importance of providing successful learning opportunities and optimal challenge situations. It is also important to note, however, that when children are young, they may not have the metacognitive awareness required to compare their own performance accurately against that of others. This lack of awareness may actually have an adaptive purpose in childhood. The fact that young children do not evaluate their own performance increases the likelihood that they will put energy and effort into practicing skills in a wide variety of environments with little concern about their actual competency.21 As children develop, however, their expectation of competence becomes more specific to the type of task and is influenced by their prior experiences with that task, their observations of typically developing peers performing it, and the evaluative feedback provided by credible adults.12

Dynamic Systems Theory

Emerging theoretical ideas from systems theory influence today’s thinking in many areas of development in children, and these ideas are beginning to lead to creation of alternative models of practice for therapy intervention. In contrast with a hierarchical model of neural organization, systems theory (also called dynamic systems theory) proposes a flexible model of neural organization in which the functions of control and coordination are distributed among many elements of the system rather than vested in a single hierarchical level.186 Work that led to the development of dynamic systems theory includes research by Bernstein,20 who used concepts from physics related to movement and applied these ideas to motor development. Bernstein proposed that the central nervous system (CNS) controls groups of muscles (not individual muscles) and that these groups can change motor behavior on their own without CNS control. He believed that motor control could emerge spontaneously from relationships among kinematics (muscles) and biomechanics (joints and bones) that naturally limit the degrees of freedom of movement. Therefore the motor system is self-organizing.169

Systems theory has its roots in geometric concepts, and at the most basic level, a dynamic system is simply something that changes over time. Dynamic systems theorists emphasize that learning does not occur just in the brain and that the body and environment are all constantly changing and simultaneously influencing each other.185 In this theoretical approach, instead of viewing behavior (e.g., motor skills) as predetermined in the CNS, systems theory views motor behavior as emerging from the dynamic cooperation of the many subsystems in a task-specific context. It implies that all factors contributing to the motor behavior are important and exert an influence on the outcome by either facilitating performance or constraining it.

In this approach, the therapist looks for periods of stability in learning and watches for signs that a child is ready to shift to a qualitatively different type of behavior. Identification of the system variables that drive the transition from one level to another facilitates learning.27 These variables can be related to the child, the task, or the environment. Thelen suggested that variables such as physical growth and biomechanics may be more important for motor learning in infancy, whereas factors such as experience, practice, and motivation may be more influential in the learning of motor activities in an older child.180

Dynamic systems theory is an ecologic approach that assumes that a child’s functional performance depends on the interactions of the child’s inherent and emerging skills, the characteristics of the desired task or activity, and the environment in which the activity is performed. Self-organization is optimal in a functional task that has a goal and outcome. Most functional tasks (e.g., eating and drinking) elicit a predictable pattern of movement; therefore, the task itself can organize the movements attempted. These features suggest that dynamic systems theory aligns well with occupational therapy.

Research in dynamic systems theory has focused on explaining the ways new skills are learned.64,133,181,182 The learning of new movements or ways of completing an activity requires that previously stable movements be broken down or become unstable. New movements and skills emerge when a critical change occurs in any of the components that contribute to motor behavior. These periods of change are called transitions. Motor change in young children is envisioned as a series of events during which destabilization and stabilization of movement take place before the transitional phase movement becomes stable and functional.147

The period of instability that occurs in a transitional phase is seen as the optimal time to effect changes in movement behavior. Three characteristic situations mark the transitional stage:

1. Variability in motor performance increases. The child experiments with different movement patterns.

2. Through these exploratory movements, the child determines which pattern is the most adaptive.

3. The child selects the movement that is most adaptive, the movement that meets his or her goals given environmental demands and constraints (e.g. which pattern makes it easiest to rise from sit to stand given the effects of gravity and available supports). During this phase, the child repeatedly practices the same movement pattern.

In children with impairments such as cerebral palsy, constraints hinder the emergence of motor functions. Such constraints are limitations imposed on motor behaviors by the child’s physical, social, cognitive, and neurologic characteristics. The constraint that traditionally has received most attention is the integrity of the CNS; less frequently, other biomechanical constraints are considered, such as biomechanical forces, muscle strength, or a disproportionate trunk-to-limb ratio. Environmental constraints include physical, social, and cultural factors not related to a specific task. One example of a physical constraint is a suboptimal surface for the child’s activity (e.g., a slippery or inclined surface); a social constraint could be a parent’s lack of reinforcement of the acquisition of motor behaviors. Task constraints are restrictions on motor behavior imposed by the nature of the task. Established motor behaviors may be altered by specific task requirements. For example, when faced with the task of crawling on rough terrain, infants may alter motor behavior by straightening the knees and “bear walking.” When a child reaches for a ball, the ball’s size influences the shape of the child’s hand and the approach taken (e.g., one hand versus two). The unique features of these tasks have shaped the child’s motor behavior. See Table 2-2 for a list of dynamic systems theory principles. Dynamic systems theory has many similarities to the emerging occupational therapy theories that focus on person, environment, and occupation relationships. This theory is further explained in Chapters 3 and 9.

TABLE 2-2

Principles of Dynamic Systems Theory Applied to Motor Development

| Dynamic System Theory Principle | Application to Motor Development |

| Sensory perception and motor systems are coupled. These systems continually interact in learning new motor skills. The infant’s perceptions guide his or her movements, which in turn create the infant’s perception of the world. | Haptic sense, discrimination of the physical properties of objects through touch, is acquired through object manipulation. Sensory information is gained as the infant’s fingers move over the object’s surfaces. |

| Functional synergies are the basis of motor behavior. Movement synergies are based on kinematic (e.g., muscles) and biomechanic (e.g., joints) constraints and are the basic units that control movement. Therefore, the basic units of motor behavior are functional synergies or coordinated structures rather than specific muscle actions. These functional synergies are “soft”—assembled (i.e., they are highly adaptable and highly reliable). | Similar synergies are used for eating and drinking that involve shoulder internal rotation and adduction, elbow extension followed by flexion, forearm pronation followed by slight supination, and a neutral wrist position. This functional synergy is also used, with slight modification in combing one’s hair and cleansing face and teeth. This is a stable but flexible synergy. |

| Transition to new movement patterns involves exploration, selection, and practice phases. The infant or child first explores many different patterns and exhibits high variability in movement. Then the infant selects an optimal pattern to achieve his goal. This pattern is practiced and becomes more adaptable to a variety of environmental demands. | When first learning to eat with a spoon, the infant exhibits a variety of patterns with the spoon, including banging, stabbing, and waving. Then the infant selects a functional pattern that successfully meets the environmental demand (e.g., the toddler learns to supinate the forearm when bringing the spoon to mouth so that the food reaches the mouth rather than spilling down the chest). This adaptive pattern is repeatedly practiced as the toddler insists on always self-feeding. |

| The infant’s unique motor patterns are the result of input from multiple systems that interact in dynamic ways to both facilitate and constrain movement. Behavior is multiply determined and children develop in context. Behavior is determined by an integrated system of perception, action, and cognition. These elements are integrated over time to form a child’s unique developmental trajectory. | The pattern an infant uses to reach for an object is determined by many variables. Variables that may influence reaching include biomechanic and kinematic factors such as weight of his or her arm, stiffness of joints, strength, and eye-hand coordination. However, the reaching pattern is also influenced by how successful the child was in previous reach and grasp (did the object move before the child could obtain it?), how motivated the child is to attain the object, general energy level, and curiosity. |

Adapted from Case-Smith, J. (1996). Analysis of current motor development theory and recently published infant motor assessments. Infants and Young Children, 9(1), 29-41; Spencer, J. P., Corbetta, D., Buchanan, P., Clearfield, M., Ulrich, B., & Schoner, G. (2006). Moving toward a grand theory of development: A memory of Esther Thelen. Society for Research in Child Development, 77, 1521-1538.

MODELS OF PRACTICE USED BY OCCUPATIONAL THERAPISTS

Occupational therapy practitioners recognize that health is supported and maintained when clients are able to engage in occupations and activities that allow desired or needed participation in home, school, workplace, and community life.2 Thus, occupational therapy practitioners are concerned not only with the child’s performance in everyday activities but also the environmental influences that enable a child’s engagement and participation in those activities.197

This section of the chapter focuses on models of practice developed specifically for occupational therapy assessment and intervention with children. An example of a theoretical framework that focuses on occupation and performance is presented first. Discussion of this overall framework is followed by overviews of specific models of practice used with children and youth. These models of practice are used in conjunction with an overall focus on occupation and occupational performance.

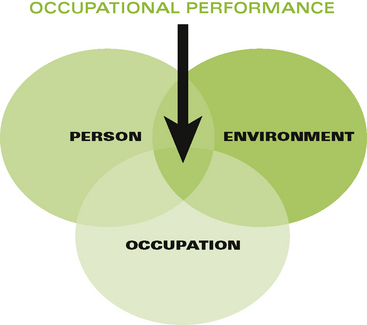

Most occupational therapy practice models explain the interaction of person, occupation, and environment. They recognize the premise that human performance cannot be understood outside of context.57 In earlier models (e.g., person-environment-performance,32 person-task-environment81), the focus of primary intervention is on the person, with relatively less emphasis on changing environments. Law and colleagues developed the person-environment-occupation (PEO) model, which focuses equally on facilitating change in the person, occupation, and/or environment.99

The PEO model was developed using theoretical foundations from the Canadian Guidelines for Occupational Therapy, environmental-behavioral theory, and work by Csikszentmihalyi & Csikszentmihalyi45 on the theory of optimal experience. The PEO model outlines the concepts of person, environment, and occupation as follows99:

• Person: A unique being who, across time and space, participates in a variety of roles important to him or her.

• Environment: Cultural, socioeconomic, institutional, physical, and social factors outside a person that affect his or her experiences.

• Occupation: Any self-directed, functional task or activity in which a person engages over the life span.

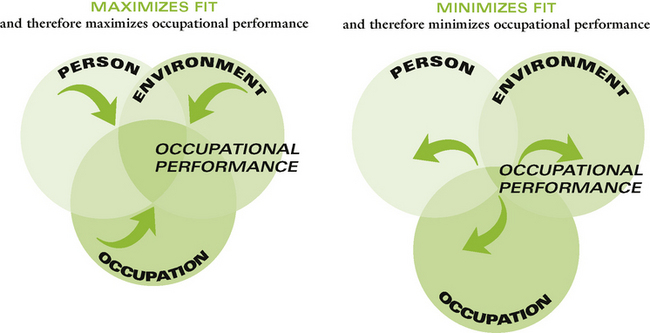

The PEO model suggests that occupational performance is the result of the dynamic, transactive relationship involving person, environment, and occupation (Figure 2-4, A). Across the lifespan and in different environments, the three major components—person, environment, and occupation—interact continually to determine occupational performance. Increased congruence, or fit, among these components represents more optimal occupational performance (Figure 2-4, B).

FIGURE 2-4 A, Person-environment-occupation model. B, Person-environment-occupation analysis. (From Law, M., Cooper, B., Strong, S., Stewart, D., Rigby, P., & Letts, L. [1996]. The person-environment-occupation model: A transactive approach to occupational performance. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63[1], 9-23.)

The PEO model is used as an analytic tool to identify factors in the person, environment, or occupation that facilitate or hinder the performance of occupations chosen by the person. Occupational therapy intervention can then focus on facilitating change in any of these three dimensions to improve occupational performance. Specific models of practice, as outlined next, can be used in conjunction with the PEO model to address specific performance limitations or environmental conditions that impede occupational performance.

Specific Models of Practice

The models of practice or frames of reference currently used in occupational therapy operate within systems theory, as each considers the interaction of person, environment, and activity or occupation. A discussion of systems theory as it influences occupational therapy interventions is presented first; then specific practice models used by occupational therapists in their work with children are explained.

A Systems Approach

Occupational therapists approach intervention with a child by first gaining an understanding of the environmental, family, and child factors that influence the performance of specific activities. From the literature that discusses the application of systems theory or dynamic systems theory to occupational therapy intervention, the following principles emerge:

• Assessment and intervention strategies must recognize the inherent complexity of task performance. The most useful assessment strategy is to develop a “picture” or “profile” of the ways performance components and environmental and task factors affect performance of the tasks the child wants to accomplish. Assessment of only one or a few components (e.g., balance, mood, strength) is not likely to lead to the most effective identification of constraints.

• The focus of assessment and intervention is on the interaction of the person, the environment, and the occupation. Therapy begins and ends with a focus on the occupational performance tasks a child or youth wants to, needs to, or is expected to perform. When a child shows readiness and motivation to attempt a task or activity, the focus of intervention on that particular activity can effect changes in his or her performance.97

• The therapy process focuses on identification and change of child, task, or environmental constraints that prevent the achievement of the desired activity. Some of these factors may be manipulated to enhance the functional motor task or goal; others may be managed by providing the missing component during the execution of the task. Parts of activities can be changed (e.g., different toy sizes, different position for child or activity). Activities should be practiced in a variety of environments that can facilitate completion of the task and promote the flexibility of movement patterns. Activities incorporated into the child’s daily routine provide opportunities for finding solutions for functional motor challenges (Figure 2-5).

FIGURE 2-5 In this functional activity, a slant board is used to promote improved posture and grasp of the pencil. A weight on the pencil provides added proprioceptive input.

• When preparing therapeutic activities, the therapist identifies playful activities that would motivate the child, are developmentally appropriate, match the child and family’s goals, provide a challenge to current skills levels, and match an expected or hoped for outcome.

• With intervention through the systems approach, the focus on changing environments and occupations is at least as great as the focus on changing the inherent skills of the child or adolescent. Intervention is best accomplished in natural, realistic environments. The accomplishment of whole occupations, not parts of them, is emphasized. The goal in therapy is to enable a child to accomplish an identified activity, rather than promote change in a developmental sequence or improve the quality of the movement.