Chapter 1 Patient intake

Recording a solid case history, deciphering presenting symptoms and developing a treatment strategy are among the most challenging aspects of any health care practice. Choosing where to begin, knowing where and when not to work, prioritizing elements of the treatment time, and designing a home care program, are just a few of the critical components of a successful manual therapy practice.

As the practitioner begins to classify the (often considerable degree of) detail acquired through the case history, patient interviews, physician reports, manual tests and palpation exams, the process abstractly resembles that of putting together a jigsaw puzzle. The history and interview build the framework of the case, just as the puzzle side pieces frame the picture. Sorting the symptoms into potential categories, such as neurological, orthopedic, nutritional, and habitual use, is as valuable as sorting the puzzle pieces by color, patterns and design. Ideally, one would like to view the box cover to see what the full picture should look like, but, in the treatment room, the situation is seldom that clear. It is often more like holding a plastic bag filled with pieces, with no accompanying box, no idea how many pieces are missing, and possibly a few extra pieces thrown in that have nothing to do with that particular puzzle. How can one possibly have success with this as the starting position?

Where to begin?

This opening chapter will help lay the foundation upon which the treatment strategies will be built. It makes some suggestions regarding the initial sifting and sorting required, in order to make sense of a new patient’s needs. Applying this as a routine sequence, a virtual checklist of what needs to be done, helps to turn a potentially confusing and stressful encounter into one that is reassuring for the patient and vitally helpful for the practitioner.

If the sort of information-gathering exercise outlined below is to be followed, involving a detailed interview as well as a physical examination, adequate time has to be allowed. Not less than an hour, and ideally 90 minutes, should enable this process to be accomplished without any sense of feeling rushed.

Outline

An outline of the intake procedure might include the following, or these might be used as a guideline for designing a written case history form.

Health and family history

• the patient’s previous medical history

• pertinent family history, particularly as it pertains to this condition

• current medications and nutritional supplements

• nutritional habits, sleep patterns and use of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs

• any unusual features (congenital problems, drug reaction history).

Presenting complaint(s)

• the main symptom(s) – including what aggravates the condition, makes it better, what it affects (work, sleep, recreation, relationships, etc.)

• a history of the presenting complaint – etiology (if known)

• a review of the main systems associated with the complaint (musculoskeletal, nervous, endocrine, etc.)

Current clinical evidence and treatment plan

• physical examination, including range of motion, functional assessments, palpation, strength evaluation

• special tests or referral for these

• clinical impression and reasoning

• formulation of a treatment plan and home/self care suggestions.

Much of the above is expanded further within this chapter, with numerous specific ‘key questions’ offered that can be used within the interview or as a written case history. Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques: practical case study exercises, a study guide designed to accompany this textbook and its companion, can assist in the development of skill to usefully apply the information gathered in the above procedures.

Expectations

What do the two parties to a consultation encounter expect? Much depends on the nature of the consultation. If it relates to a simple musculoskeletal problem, the depth of inquiry need not be as great as in the case of someone with, for example, a rheumatic or systemic disease, such as fibromyalgia syndrome or osteoporosis. However, even in apparently simple presentations, such as ‘low back pain’, there are many pitfalls and darker possibilities (see Box 10.1 in Chapter 10, regarding ‘impostor’ symptoms or, as Grieve (1994) calls them, ‘masqueraders’; see also Box 1.1).

Grieve (1994) has described ‘impostor’ symptoms (see Box 10.1 page 228).

If we take patients off the street, we need more than ever to be awake to those conditions which may be other than musculoskeletal; this is not ‘diagnosis’, only an enlightened awareness of when manual or other physical therapy may be more than merely unsuitable and perhaps foolish. There is also the factor of perhaps delaying more appropriate treatment.

He suggests that we should be suspicious of symptoms which present as musculoskeletal if:

• the symptoms as presented do not seem ‘quite right’; for example, if there is a discrepancy between the patient’s story and the presenting symptoms

• the patient reports patterns of activity which aggravate or ease the symptoms, which are unusual in the practitioner’s experience.

Grieve cautions that practitioners should remain alert to the fact that symptoms that arise from sinister causes (neoplasms, for example) may closely mimic musculoskeletal symptoms or may co-exist with actual musculoskeletal dysfunction.

If a treatment plan is not working out, if there is lack of progress in the resolution of symptoms or if there are unusual responses to treatment, the practitioner should urgently review the situation.

A lengthy, in-depth gathering of information is therefore ideal, if time allows.

The patient is (usually) hoping that his problem(s) will be heard and understood and that helpful suggestions, and possibly treatment, will result. For this to occur, the practitioner needs to be able to listen to, summarize and take notes on the information provided. Ideally, the practitioner should be satisfied that the patient is presenting an accurate history and is answering reasonably, honestly and frankly.

In the first consultation some structured direction and guidance may be called for, to prevent the symptoms, along with the history (often involving multiple life-events and influences), from being presented in a jumbled and uncoordinated manner. The more anxious the patient, the more likely this is to occur. Anxious or not, some patients seem incapable of actually giving direct answers to the questions posed and drift into delivering rambling discourses of what they think the practitioner should know. Care should always be taken when interrupting the patient’s flow; if necessary, this should be done in such a way that it does not inhibit his willingness to discuss his problems. A gentle firmness is needed to redirect the individual. ‘That’s interesting, and I am sure we will have time to discuss it, but so that I don’t lose track of the information I am looking for right now, please answer the last question I asked you.’ Such tactics frequently require repetition until a flow of appropriate responses is achieved. When information is confusing, it is best to seek clarification immediately, with a comment such as, ‘I haven’t quite understood that. Let’s try to make it clearer, so that I am not mistaken, tell me again about…’

Humor

Somewhere in the initial interview humor may be useful and appropriate. Some patients, however, may see this as making light of their undoubted anxieties, so care is needed. In most instances, a carefully moderated sense of fun may be interjected, to lighten the atmosphere and put the patient at ease, although this should never be at the expense of the patient’s dignity.

Attention should also be paid as to whether the patient is using an excessive degree of humor or is constantly joking about his/her condition. This could be a result of being shy about discussion of a physical condition (particularly in more intimate body regions) or to cover hidden emotions from having been ‘dismissed’ by other practices as being ‘psychosomatic’. Although psychological problems can certainly be the root cause or a perpetuating factor in myofascial pain, mysterious symptoms that are often associated with trigger points and other myofascial conditions often baffle practitioners who have no training or skill in treating them. It is easy to dismiss this person as having a problem that is ‘all in the head’, a diagnosis that may significantly affect the attitude and outlook of the patient.

Thick-file patients

The patient who arrives bearing a thick folder, or even a satchel or box, containing notes, records, cuttings and computer print-outs, deserves a special mention. In Europe (and possibly elsewhere) these are often labeled ‘heart-sink’ patients, since this is the effect they may have on the practitioner. Commonly these patients will have been to many other therapists and practitioners and you are probably just one more disappointment-in-waiting, since they seldom seem to find what they are seeking, which is someone whose professional opinion tallies with their perception of what is happening (which may have bizarre elements of pseudoscience embedded in it). Many such patients may be categorized as having ‘chronic everything syndrome’, ranging from fatigue to pain, insomnia, gut dysfunction and a host of other problems, including anxiety and sometimes depression. Some will have been labeled as ‘neurotic’, others may have acquired a diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia, sometimes appropriately and sometimes not. There are no easy solutions to handling such patients, except to dig deep into the compassion resources that hopefully have not been exhausted.

Conversely, many times this type of patient actually turns out to be a very committed person, who has been consistent in looking for help and has not lost confidence that someone, somewhere can help him. He may have tried everything except soft tissue manipulation. The thick file is a result of a multitude of tests, which have been performed without finding the source of his pain. The missing element in this file may well be a thorough trigger point examination. It is seldom performed in medical examinations and, in the experience of the authors, is very commonly a significant part of this patient’s problem. (Lymphatic drainage is often another key element missing from these files.)

It is important that the manual practitioner should not become discouraged or intimidated by the fact that the patient has already seen a host of physicians (often the ‘best in town’ or those at famous clinics). The fact that there may have been a vast array of negative tests, which have ruled out serious pathologies, should encourage a search for alternative etiological patterns, possibly associated with myofascial trigger points, lymphatic stasis, hyperventilation or any of a number of ‘low-tech’ contributory factors, which have thus far been overlooked. Once treatment of trigger points has been applied to this ‘thick-folder’ patient, who very often has been suffering for many years, pain patterns may resolve very quickly. Although there will indeed be a collection of patients who fit the first description above, the attitude of the practitioner should always be one which offers (realistic) hope and encouragement, especially in the initial and early treatment sessions.

Unspoken questions

One unspoken area of the consultation involves the concerns the patient really wants answered. Seldom said, but always present, are questions such as ‘Will I get better (and, if so, how long will it take)?’ and ‘How serious is this (and, if serious, can you help)?’ It is well established that understanding the nature of the problem, knowing something about its causes and influences is a major therapeutic step forward for the patient. The practitioner’s role should be to educate and reassure (honestly), just as much as to offer treatment. By offering explanations, a prognosis and a plan of action, the practitioner can help to lift the burden. Where there was doubt and confusion, now there is a degree of understanding and hope, but this hope must be grounded in reality and not fiction. This calls for methods of communication between the practitioner and the patient that are clear, non-evasive and not embroidered with fantasy. It also requires a comprehensive grasp of foundational anatomy, physiology, function and dysfunction on the part of the practitioner, in order to be able to confidently (and accurately) convey these details.

Starting the process

‘Where shall I begin?’ is a frequent query when the patient is sitting comfortably and has been asked something such as ‘How can I help you?’ or ‘Why have you come to see me?’ or even ‘Tell me when you were last completely well’. Another approach is to say, ‘Start at the beginning, and from your point of view, tell me what’s causing you most concern, and how you think it began’.

After such a start it is appropriate to ask for a list of current symptoms (‘What’s giving you the most trouble at present? Tell me about it and any other symptoms that are bothering you’). It is useful to ask for symptoms to be discussed in the order of their importance, as the patient perceives things. Following this, a question-and-answer filtering of information can begin, which tries to unravel the etiology of the patient’s problems. During this process it is useful to make a record of dates (of symptoms appearing, life events, other medical consultations/tests/treatments) as the story unfolds, even if not presented strictly chronologically. If the patient has already prepared this in advance, the practitioner should read through the list with the patient as other (and often significant) details may emerge during the discussion.

Whatever method starts the disclosure of the patient’s story, a time needs to come, once the essentials have been gathered, when detailed probing by the practitioner is called for, perhaps involving a ‘system review’ in which details of general well-being, cardiovascular, endocrine, alimentary, genitourinary, nervous and locomotor systems are inquired after (as appropriate to the particular presenting symptoms, for such detailed inquiry would clearly be inappropriate in the case of a strained knee joint but might be important in more widespread constitutional conditions). For the practitioner whose scope of practice and training does not include a comprehensive understanding of these systems, a more generalized inquiry in the form of a case history questionnaire might point to the need to refer the patient to confirm, or rule out, possible contributory problems.

Leading questions

It is important when questioning a patient not to plant the seed of the answer. Patients, especially if nervous, may answer in ways that they believe will please you. Leading questions suggest the answer and should be avoided. See Box 1.2.

Box 1.2 Essential information relating to pain

If pain is involved as a presenting symptom the following information is of great importance.

• Where is the pain? Have the patient physically point out where the pain is experienced, as a comment such as ‘in my hip’ may mean one thing to the patient and quite another to the practitioner.

• Has this happened before or is this the first time you have had this problem?

• If you have had this before, how long did it take to get better (and was treatment needed)?

• Does the pain spread or is it localized?

• Describe the pain. What does it feel like?

• If not, when is it present/worst (at night, after activity, etc.)?

An example might involve the patient informing you that ‘My back pain is often worse after my lunch-break at work’. You might suspect a wheat intolerance and inappropriately ask ‘Do you eat bread or any other grain-based foods at lunch time?’ instead of less obviously suggesting ‘Tell me what sort of food you usually have at lunchtime’. And, of course, the increase in back pain may have nothing to do with food at all. Therefore, a more appropriate question might be ‘Is there anything about the lunch-break at work that might stress your back?’. A response that the seating in the café where the patient normally eats is particularly unsupportive of his back could be the reward for such an open query.

Questions need to be widely framed in order to allow the patient the opportunity to fill the gaps, rather than having too focused a direction which leads him toward answers that may be meaningless in the context of his problem or support your own pet theories (wheat intolerance, for example).

Some key questions

The following questions offer considerable and significant information. These can be included in the initial interview or can be presented as an ‘on paper’ interview to be completed prior to the initial visit. The latter option may offer the patient more time to consider a full range of memories that might not surface under the time constraints and pressures of a live interview.

• Summarize your past health history, from childhood, especially any hospitalizations, operations or serious illnesses.

• Have you any history of serious accidents, including those that were not automobile accidents?

• What has brought you to see me and what do you believe I might be able to do for you?

• Have you used or do you now use social drugs?

• If not, what was the cause of death?

• If they are living tell me about their health history. (Note: family history can sometimes be extremely useful, especially regarding genetically inherited tendencies, for example sickle cell anemia. However, more often answers to these questions offer little value.)

• If so, tell me about their health history. Include any that are deceased, as well as cause(s) of death.

• How often do you catch cold/flu and when was the last time?

• When was the last time you consulted a physician and what was this for?

• Have you ever consulted a physician for an extended time or serious condition?

• Are you currently undergoing any treatment or doing anything at home in the way of self-treatment?

• Are you currently or have you in the past been on prescription medication? If so, summarize these (when, for what, for how long, especially if steroids or antibiotics were involved).

• How long have your current symptoms been present?

• Have the symptoms changed (for better or worse) and, if so, in what way(s)?

• Do the symptoms alter or are they constant?

• If they alter, is there a pattern (do they change daily, periodically, after activity, after meals, associated with phases of the menstrual cycle, etc.)?

• What seems to make matters worse?

• What seems to make matters better?

• Tell me about your sleep patterns, the quality and quantity of sleep.

• Tell me about any of the positions in which it is easy for you to fall asleep, those in which you sleep comfortably or those in which you awake with pain.

• What activities do the symptoms stop you (or hinder you) from doing?

• What diagnosis and/or treatment has there been and what was the effect of any treatment you have received?

• Are you settled and satisfied in your relationship(s)?

• Are there any relationships that are stressful or unfulfilling for you, including family, work and social?

• Would you describe yourself as anxious, depressed, an optimist or pessimist?

• If you are in a relationship tell me a little about your partner.

• Are you settled and satisfied in your home life?

• Are you settled and satisfied in your work/occupation/career or studies?

• Tell me a little about your work.

• Do you have any immediate or impending economic anxieties? Lawsuits?

• Are you satisfied with your present weight and state of general health (apart from the problems you have consulted me for)?

• What are your energy levels like (possibly with supplementary questions such as: Do you wake tired? Do you have periods of the day where energy crashes? Do you use stimulants such as caffeine, alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs, to boost energy? Do you use sugar-rich foods as a source of energy?)?

• Tell me about your hobbies and leisure activities.

• Do you smoke (and if so, how many daily)?

• Do you live, or work, with people who smoke?

• What elements of your life or lifestyle do you think might help your health problem, if you changed them?

• What are the main ‘stress’ influences in your life?

• Do you practice any forms of relaxation? Meditation? Focused breathing?

If the patient is female it is also important to know if she is menopausal, perimenopausal, taking (or has taken) contraceptive or hormone replacement medication (which many do not report when asked about their medication history), is sexually active, has children (if so, how many and what ages and was each labor normal?). If she is still menstruating, information regarding the cycle may be useful, especially in relation to influence on symptoms.

If appropriate, questions can be discreetly asked about eating disorders, mental health and physical or emotional abuse. Unless the patient has freely offered this information in the above questioning, it is often best to postpone questions until a relationship of trust has been established.

Additionally, it is useful to have a sense of the patient’s diet, drinking habits (alcohol, water, coffee, cola, etc.), use of supplements, sleep pattern (how much? what quality? tired or fresh on waking?), exercise and recreation habits and, if appropriate, their digestive and bowel status.

Having the patient fill out a detailed questionnaire ahead of the consultation can certainly save time and assure that many of the basic details are recorded. However, it is it almost always much more effective to hear the answer, because the answer to a question is often less important than the way it is answered.

As questions are asked and answered, it is important that the practitioner avoids even a semblance of judgmental response, such as shaking of the head or ‘tut-tutting’ or offering verbal comments that imply that the patient has done something ‘wrong’. The practitioner is present as a sounding board, a recorder of information, a prompt to the reporting of possibly valuable data. There should be time enough after all the details have been gathered to inform, guide, suggest and possibly even to cajole, but not usually at the first meeting.

It is important that the practitioner be familiar with any listed medications the patient is taking, including potential side effects of those drugs. For instance, some blood pressure medications may induce muscular spasms and when such symptoms are present this may be an indication that the dosage requires modification. Referral to the prescribing physician would then be appropriate. Any anticoagulant (an effect of many pain medications) should be noted, as deep tissue work may cause bruising. For many years a physician’s desk reference, nurse’s guide to prescription drugs or similar handbook was consulted for any medications for which the practitioner was not familiar. Today these handbooks are almost obsolete since the information load changes so frequently that the internet has virtually replaced the printed copies as the most up-to-date reference source.

Similarly, the Merck Manual has always been useful to consult regarding any diagnosed conditions that the patient lists with which the practitioner is unfamiliar. These and other diagnostic handbooks are now available online, at little or no cost, making the latest edition easily searchable and readily available for any practitioner who has internet access. Information about the diagnosis may be of value when formulating a treatment plan or could suggest a contraindication to treatment or at the least flag a need for caution regarding certain procedures (see also Chapter 10, Box 10.1, on impostor symptoms). It is always possible, of course, that a previous diagnosis is not correct but understanding its nature may still offer value to the current analysis.

Body language

During the inquiry phase particular attention should be paid to changes in the patient’s breathing pattern, altered body positioning (shifting, twitching, slumping, etc.), increased rate of swallowing, evidence of light perspiration or of sighing. If any such signs are noted, their association with particular areas of discussion (relationship, job, finance, etc.) should be noted. These may be areas where much remains unsaid and much needs to be revealed.

Out of this sort of questioning and careful listening to responses, a picture should emerge that offers some explanation for the presenting symptoms. Hopefully, over a period of time the story will add up; the causes and effects will make sense. This is not necessarily a process aimed at making a diagnosis; rather, it is an insurance against inappropriate treatment being offered. If the story does not add up and if symptoms do not seem to derive from a process that your experience suggests to be logical, based on the history you have been presented, you should hear a first alarm bell ringing. Never ignore such alarm bells. A ‘gut feeling’ that this story does not make sense is more likely to be right than wrong. Something may have been missed, either in the history that the patient presented, in your understanding of that story or in previous investigations. It is also possible that undiagnosed, sinister causes (such as bone loss, systemic failure or cancer) are at the root of the situation, and these alarm bells may serve as your ‘red flag’ warnings to refer the patient for further investigation.

The purpose of this first interview/consultation is twofold: to gather information and to create a trusting professional relationship. You have to trust that what the patient tells you is true and the patient has to trust that because you have heard the whole story, combined with the examination and assessment which follows, you will be able to offer appropriate advice and help.

There is often a subtext in consultations: many things are unsaid, hinted at, half expressed in body language rather than verbally and the focused practitioner may pick up such clues, subliminally or overtly. Some of these unspoken issues may relate to unexpressed hopes and fears. There is time enough when hands-on work is under way, or at subsequent sessions, to dig a little deeper, once trust has been established and confidence built.

Once the note taking is complete it is extremely useful to read back to the patient what you have noted down, taking them through their own history, step by step. This allows any errors to be corrected or additions to be made, and offers the patient a chance to realize that you have not only heard the story but have understood it.

The physical examination

Petty (2006) has provided a summary of what is needed in any physical exam, from a physical and occupational therapy perspective (Table 1.1). Lee (2004) has detailed her perspective on the ingredients for a full objective musculoskeletal examination (Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 Summary of the physical examination*

| Area of examination | Procedure |

|---|---|

| Observation | Informal and formal observation of posture, muscle bulk and tone, soft tissues, gait, function and patient’s attitude |

| Joint integrity tests | For example, knee abduction and adduction stress tests |

| Active physiological movements with overpressure | Active movement with overpressure |

| Passive physiological movements | |

| Muscle tests | Strength, control, length, isometric contraction, diagnostic |

| Nerve tests | Neurological integrity, neurodynamic, diagnostic |

| Special tests | Vascular, soft tissue, cardiorespiratory, etc. |

| Palpation | Superficial and deep soft tissues, bone, joint, ligament, muscle, tendon and nerve |

| Joint tests | Accessory movements, natural apophyseal glides, sustained natural apophyseal glides and mobilizations with movement |

* (reproduced with permission from Petty 2006)

Table 1.2 Objective examination**

| FUNCTION |

| Gait |

| Posture |

| Regional movement tests |

| FORM CLOSURE – LUMBAR SPINE |

| Lumbar spine: positional tests |

| Lumbar spine: passive tests of osteokinematic function (PIVM) |

| Lumbar spine: passive tests of arthrokinematic function (PAVM) Superioanterior glide – zygapophyseal joint Inferoposterior glide – zygapophyseal joint Lumbar spine: passive tests of arthrokinetic function Compression Rotation Anterior translation Posterior translation Lateral translation |

| FORM CLOSURE – PELVIC GIRDLE |

| Pelvic girdle: positional tests Innominate Sacrum |

| Pelvic girdle: passive tests of osteokinematic function (PIVM) Anterior/posterior rotation – innominate Nutation/counternutation – sacrum |

| Pelvic girdle: passive tests of arthrokinematic function (PAVM) Inferoposterior glide – sacroiliac joint Superoanterior glide – sacroiliac joint |

| Pelvic girdle: passive tests of arthrokinetic function Horizontal translation – sacroiliac joint and pubic symphysis Vertical translation – sacroiliac joint and pubic symphysis Vertical translation – pubic symphysis |

| Pelvic girdle: pain provocation tests Long dorsal ligament Sacrotuberous ligament Anterior distraction – posterior compression Posterior distraction – anterior compression |

| FORM CLOSURE – HIP |

| Hip: positional tests |

| Hip: passive tests of osteokinematic function (PIVM) Flexion Extension Abduction/adduction Lateral/medial rotation Combined movement test (in flexion) Combined movement tests (in extension) |

| Hip: passive tests of arthrokinematic and arthrokinetic function (PAVM) Lateral/medial translation Distraction/compression Anteroposterior/posteroanterior translation |

| Hip: pain provocation and global stability Torque test Inferior band of the iliofemoral ligament Iliotrochantric band of the iliofemoral ligament Pubofemoral ligament Ischiofemoral ligament |

| FORCE CLOSURE AND MOTOR CONTROL |

| Anterior abdominal fascia – test for diastasis of the linea alba Deep fibers of multifidus |

| Active straight leg raise test Simulation of the local system Simulation of the global system |

| Active bent leg raise test |

| Local system – co-contraction analysis |

| Local system and the neutral zone |

| Real time ultrasound analysis |

| Global system slings – strength analysis The posterior oblique sling The anterior oblique sling The lateral sling |

| Global system slings – length analysis The posterior oblique sling and the latissimus dorsi The anterior oblique sling and the oblique abdominals The longitudinal sling and the erector spinae The longitudinal sling and the hamstrings Psoas major, rectus femoris, tensor fascia latae, adductors Piriformis/deep external rotators of the hip |

| Pain provocation tests – contractile lesions |

| NEUROLOGICAL CONDUCTION AND MOBILITY TESTS |

| Motor conduction tests |

| Sensory conduction tests |

| Reflex tests |

| Dural/neural mobility tests Femoral nerve Sciatic nerve |

| VASCULAR TESTS |

| ADJUNCTIVE TESTS |

** (reproduced with permission from Lee 2004)

Information garnered through sequential assessment involving observation, joint tests, muscle tests, neurological tests, specialized tests (for trigger points, for example), functional tests, palpation and evaluation of accessory movements can be added to the information gathered from the patient’s history and presenting complaint(s). This should create the basis for formulation of a therapeutic action plan. Many of these tests, for different regions of the body, are described in the appropriate chapters in this book.

In osteopathic medicine, four basic characteristic signs are evaluated when seeking evidence of localized musculoskeletal (somatic) dysfunction. The acronym TART has been used to describe these criteria.

• Tissue texture changes/abnormalities

• Asymmetry of palpated or observed landmarks

Where a combination of these and other characteristics is located by observation, palpation and assessment, a dysfunctional musculoskeletal area exists. This does not, however, provide evidence as to why the dysfunction has occurred, only that it is present.

Clinical reasoning

Tests, palpation and observation assessments offer ‘what’ answers, such as ‘these tissues are sensitive, asymmetrical, restricted, short, tight, weak’ – and so on.

None of these findings, however, actually offer indications as to what to do clinically.

By asking the ‘why?’ question, we can begin to narrow the therapeutic target.

‘Why are these tissues restricted?’, ‘Why is this sensitive to pressure?’, ‘What is helping to cause/maintain these findings?’

Answers to such questions can focus attention on biomechanical factors, or on neurological influences – and from such indications we can move toward a therapeutic plan.

An additional series of questions also require answering in order to develop a strategic plan. (Kappler 1996):

• Is this somatic dysfunction related to the patient’s symptoms and, if so, how?

• Can/should the dysfunctional area be beneficially modified by manual or movement therapy?

• If so, which methods are best suited to achieving this, taking account of the patient’s condition?

• The answers to these questions may relate to the answers to supplementary questions.

The therapeutic plan

In formulating a treatment plan an objective is essential. The means by which the objective is achieved may vary but until there is a review and possible revision, the objective(s) should remain unchanged. This may sound obvious but it lies at the heart of the process of creating a plan of action. Before considering objectives a sifting process is useful, in which the patient and the condition are evaluated in relation to the following types of queries.

• Is this a condition which is likely to improve/resolve on its own? If it is, therapeutic intervention should be refined to avoid inhibiting the natural process of recovery. An example might be a strained joint, which in time would recover unaided. Intervention might be focused on ensuring sound muscle balance and joint mobility, possibly including normalization of localized soft tissue fibrosis.

• Is this a condition that might improve on its own but is more likely to remain a background problem unless suitable treatment is offered? In such a case a plan of action, with clear objectives and regular review of progress, is appropriate. Self-help rehabilitation strategies and re-education of use patterns (posture, breathing, etc.) might be appropriate.

• Is this a problem that is unlikely to improve, is more likely to deteriorate (involving arthritic changes, for example) but which has the potential to be eased symptomatically? In such a case therapeutic objectives need to take account of the likely progression of the condition, with palliative and self-help interventions designed to retard degeneration and to encourage better adaptation. ‘Progress’, in many instances of chronic pain and dysfunction, is measured not by improvement but by slowing the seemingly inevitable process of degeneration.

• Is this a condition that has almost no chance of either improvement or even slowing the degenerative processes? In such cases, palliation is the likely objective, to ease discomfort and to make the process of decline as comfortable as possible.

• All these objectives may be of value to the patient. The likelihood that improvement is not possible should not mean that the patient should not be helped to cope better with the inevitable decline.

• In designing a treatment plan the following questions might also usefully be considered.

• What is it that needs to be achieved (reduction/removal of a particular pain; restoration of movement to a restricted joint; improved function, etc.)?

• What are the best ways available of achieving those ends (which of the techniques available are most likely to help in reaching the objectives)?

• Am I capable of delivering these methods/techniques or would referral be more appropriate?

• How long is it likely to take before progress is noted (taking account of the acuteness/chronicity of the problem, exacerbating features and the condition of the patient)?

• Are there things the patient could be doing to assist in the process (home stretching, hydrotherapy, change in diet, relaxation procedures, etc.)?

• After an appropriate period of time, depending on the nature of the condition and the patient, progress should be reviewed.

• Have the original objectives been partly or wholly achieved?

• If not, are there other ways of trying to achieve them?

The treatment plan needs to take account of the patient’s ability to respond, which depends largely on the patient’s vitality levels. Kappler (1996) summarizes this need by saying:

‘The dose of treatment is limited by the patient’s ability to respond to the treatment. The practitioner may want to do more and go faster; however the patient’s body must make the necessary changes toward health and recovery.’

The old adage ‘Less is more’ is an important lesson that most practitioners learn by experience, often after discovering that too much of a good thing is still ‘too much’ or because a particular approach worked well once, doing more of the same often did not. These thoughts highlight a truth that can never be emphasized too strongly – that the body alone contains the ability for recovery. Healing and recovery are achieved via the expression of self-healing potentials inherent in the mind-body complex (broken bones mend, cuts heal, etc., without external direction). Treatment is a catalyst, a trigger, which should encourage that self-healing process by removing factors that may be retarding progress or by improving functional abilities.

The summary below of possible approaches to treatment of problems such as fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) offers insights into the need for care in making treatment choices in complex cases and conditions.

A summary of approaches to chronic pain problems (Chaitow 2007, 2010)

When people are very ill (as in FMS and chronic fatigue syndrome – CFS), where homeostatic adaptive functions have been stretched to their limits, any treatment (however gentle) represents an additional demand for adaptation (i.e. it is yet another stressor to which the person has to adapt). It is therefore essential that treatments and therapeutic interventions are carefully selected and modulated to the patient’s current ability to respond, as well as this can be judged.

When symptoms are at their worst only single changes, simple interventions may be appropriate, with time allowed for the body/mind to process and handle these.

It may also be worth considering general, whole-body, constitutional, approaches (dietary changes, hydrotherapy, non-specific ‘wellness’ massage, relaxation methods, etc.), rather than specific interventions, in the initial stages and during periods when symptoms have flared. Recovery from FMS is slow at best and it is easy to make matters worse by overenthusiastic and inappropriate interventions. Patience is required by both the health-care provider and the patient, in an effort to avoid raising false hopes, while realistic, therapeutic and educational methods that do not make matters worse are used and which offer ease and the best chance of improvement.

Assessment of gross musculoskeletal dysfunction

• Sequential assessment and identification of specific shortened postural muscles, by means of observed and palpated changes, functional evaluation methods, etc. (Greenman 1996)

• Sequential assessment of weakness and imbalance in phasic musculature

• Subsequent treatment of short muscles by means of MET or self-stretching will allow for regaining of strength in antagonist muscles that have become inhibited. At the same time, gentle toning exercise may be appropriate.

Identification of local dysfunction

• Off-body scan for temperature variations (cold may suggest ischemia, hot may indicate irritation/inflammation).

• Evaluation of fascial adherence to underlying tissues, indicating deeper dysfunction.

• Assessment of variations in local skin elasticity, where loss of elastic quality indicates a hyperalgesic zone and probable deeper dysfunction (e.g. trigger point) or pathology.

• Evaluation of reflexively active areas (trigger points, etc.) by means of very light single-digit palpation seeking phenomenon of ‘drag’ (Lewit 1992).

• NMT palpation utilizing variable pressure, which ‘meets and matches’ tissue tonus.

• Functional evaluation to assess local tissue response to normal physiological demand, as in functional evaluation of muscular behavior during hip abduction, or hip extension, as described in Chapter 11 (Janda 1988).

Treatment of local (i.e. trigger points) and whole muscle problems

• Tissues held at elastic barrier to await physiological release (skin stretch, myofascial release techniques involving ‘C’ or ‘S’ bend methods or direct lengthening approaches, gentle NMT, etc.).

• Use of positional release methods – holding tissues in ‘dynamic neutral’ (strain/counterstrain, functional technique, induration technique, fascial release methods, etc.) (Jones 1981).

• MET methods for local and whole muscle dysfunction (involving acute, chronic and pulsed [Ruddy’s] MET variations as described in Chapter 9).

• Vibrational techniques (rhythmic/rocking/oscillating articulation methods; mechanical or hand vibration).

• Deactivation of myofascial trigger points (if sensitivity allows) utilizing trigger point pressure release, INIT or other methods (acupuncture, ultrasound, etc.) (Baldry 2005).

Re-education/rehabilitation/self-help approaches

• Postural (Alexander, Aston patterning, structural bodywork, etc.)

• Breathing retraining (Chaitow et al 2002, Garland 1994)

• Cognitive behavioral modification

• Yoga-type stretching, tai chi

• Deep relaxation methods (autogenics, etc.)

Choices: soft tissue or joint focus?

In this book, when you are confronted by a series of descriptions of therapeutic modalities and procedures, you will no doubt wonder which should be chosen in relation to treating a particular condition. For example, in the descriptions in Chapters 10 and 11 of low back and sacroiliac dysfunction and pain, a variety of strategies are offered for normalizing the region and/or the restricted joint. The following queries will guide decisions regarding protocols, while still maintaining diverse choices based upon what is found in examination.

Q. Should manipulation/mobilization of joints be used?

A. Possibly. However, in our experience, soft tissue imbalances, which might be causing or maintaining a joint problem, are usually best dealt with first. Manipulation of the joint may require referral to an appropriately licensed practitioner and usually best follows the creation of a suitable soft tissue environment in which shortness/weakness imbalances have been lessened. For example, the information in Chapter 11 demonstrates just how complex muscular and ligamentous influences on the SI joint can be. For instance, during walking there is a ‘bracing’ of the ligamentous support of the SI joint to help stabilize it, involving all or any of the following muscles: latissimus dorsi, gluteus maximus, iliotibial band, peroneus longus, tibialis anterior, the hamstrings and more (Vleeming et al 2007). Since any of these muscles could conceivably be involved in maintaining compression/locking of the joint, they should be considered and evaluated (and, if necessary, treated) when dysfunction of the joint occurs, before (or in many instances, instead of) manipulation of the joint (see Box 1.5).

Q. Are there soft tissue or other techniques which could destabilize joints?

A. In the case of joints where ligamentous support is greatest (e.g. SI joint, knee) it is possible that frequent, overenthusiastic or repetitive adjustment/manipulation could create, or aggravate, joint instability, reinforcing the suggestion that soft issue methods be utilized initially and joints assessed for hypermobility issues. However, the same caution regarding the possible creation of instability applies to overenthusiastic stretching of the tissues that support joints, particularly where hypermobility is a pre-existing feature and where taut bands (such as those associated with trigger points) are providing a means of stability. This is as true of stretching applied passively to a patient in the treatment room as it is of home stretching, whether or not it is well structured and appears appropriate (see hypermobility discussion in Box 1.3, on p. 8–9). (Greenman 1996, Lewit 1985).

Q. In a patient presenting with low back or sacroiliac pain or dysfunction, should the muscles attaching to the pelvis be evaluated for shortness/weakness and treated accordingly?

A. Almost certainly, as any obvious shortness or weakness in muscles attaching to the pelvis is likely to be maintaining dysfunctional patterns of use, even if it was not part of the original cause of the low back or SI joint problem. Any muscle that has a working relationship (e.g. antagonist, synergist) with muscles involved in stabilizing the low back or SI joint could therefore be helping to create or maintain an imbalance and should be assessed for shortness and/or weakness. Again, the caution must be applied that these muscles may also be offering stability to an unstable joint and attention paid to hypermobility issues as well as whether soft tissue treatment helps or aggravates the region.

Q. Should muscle energy technique (MET) or positional release technique (PRT) or myofascial release (MFR) or neuromuscular therapy (NMT) or mobilization or high velocity, low amplitude (HVLA) thrust or other tactics be used?

A. Yes, to most of the above! The choice of procedure, however, should depend on the training of the individual and the degree of acuteness/chronicity of the tissues being treated. The more acute the situation, the less direct and invasive the choice of procedure should be, possibly calling for positional release methods initially, for example. HVLA (high velocity, low amplitude) thrust methods should be reserved for joints that are non-responsive to soft tissue approaches and, in any case, should follow a degree of normalization of the soft tissues of the region, rather than preceding soft tissue work. In most cases, all the procedures listed will ‘work’ if they are appropriate to the needs of the dysfunctional region and if they encourage a restoration of functional integrity.

Q. Should trigger points be located and deactivated and, if so, in which stage of the therapeutic sequence and which treatment approach should be chosen?

A. Trigger points may be major players in the maintenance of dysfunctional soft tissue status. Trigger points are responsible for a wide variety of sensory and motor disturbances in their referred target zones. Trigger points in the key muscles associated with any joint restriction, or antagonists/synergists of these, could create imbalances that would result in joint pain. Trigger points may therefore (and usually do) need to be located and treated early in a therapeutic sequence aimed at restoring normal joint function, using methods with which the practitioner is familiar. Whether this be employment of procaine injections, acupuncture, ultrasound, spray-and-stretch techniques, prolotherapy to stabilize the joints that trigger points may be trying to support, or any suitable manual approach ranging from ischemic compression to positional release and stretching or, indeed, a combination of these methods will depend upon the practitioner’s skill and scope of practice. What matters is that the method chosen is logical, non-harmful, and effective, and that the practitioner has been trained to use it and licensed, if required.

Box 1.5 Joints and muscles: which to treat first?

(Note: This box is slightly modified from material derived from Chaitow 2007)

There is no general agreement among manual practitioners as to the hierarchy of importance of ‘joints’ and ‘soft tissues’. Both are likely, in different circumstances, to be the predominant factor in a dysfunctional situation. However, the authors favor soft tissue attention before osseous adjustment/manipulation/mobilization (whether this involves articulation or HVLA thrust) with manipulation reserved for those instances where an intraarticular dysfunction exists (see Lewit’s observations below) or where mobilization and manipulative methods assist in the objectives being targeted by soft tissue methods.

Janda (1988) acknowledges that it is not known whether dysfunction of muscles causes joint dysfunction or vice versa. However, he suggests that it is possible that the benefits noted following joint manipulation derive from the effects such methods (HVLA thrust, mobilization, etc.) have on associated soft tissues.

Lewit (1985) addressed this controversy in an elegant study that demonstrated that some typical restriction patterns remain intact even when the patient is observed under narcosis with myorelaxants. He tries to direct attention to a balanced view when he states:

The naive conception that movement restriction in passive mobility is necessarily due to articular lesion has to be abandoned. We know that taut muscles alone can limit passive movement and that articular lesions are regularly associated with increased muscular tension.

He then goes on to point to the other alternatives, including the fact that many joint restrictions are not the result of soft tissue changes, using as examples those joints not under the control of muscular influences – tibiofibular, sacroiliac, acromioclavicular. He also points to the many instances where joint play is more restricted than normal joint movement; since joint play is a feature of joint mobility which is not subject to muscular control, the conclusion has to be that there are indeed joint problems in which the soft tissues are a secondary factor in any general dysfunctional pattern of pain and/or restricted range of motion (blockage).

This is not to belittle the role of the musculature in movement restriction, but it is important to reestablish the role of articulation, and even more to distinguish clinically between movement restriction caused by taut muscles and that due to blocked joints, or very often, to both.

In later chapters, where clinical application is detailed (Chapters 12, 13 and 14, in particular), the importance of assessing and enhancing joint play will be highlighted as being clinically useful.

Steiner (1994) discusses the influence of muscles in disc and facet syndromes and describes a possible sequence as follows

• A strain involving body torsion, rapid stretch, loss of balance, etc. produces a myotactic stretch reflex response in, for example, a part of the erector spinae

• The muscles contract to protect excessive joint movement and spasm may result if there is an exaggerated response and they fail to assume normal tone following the strain

• This limits free movement of the attached vertebrae, approximates them and causes compression and bulging of the intervertebral discs and/or a forcing together of the articular facets

• Bulging discs might encroach on a nerve root, producing disc syndrome symptoms

• Articular facets, when forced together, produce pressure on the intraarticular fluid, pushing against the confining facet capsule, which becomes stretched and irritated

• The sinuvertebral capsular nerves may therefore become irritated, provoking muscular guarding and initiating a self-perpetuating process of pain–spasm–pain.

From a physiological standpoint, correction or cure of the disc or facet syndromes should be the reversal of the process that produced them, eliminating muscle spasm and restoring normal motion.

He argues that before discectomy or facet rhizotomy is attempted, with the all too frequent ‘failed disc syndrome surgery’ outcome, attention to the soft tissues and articular separation to reduce the spasm should be tried, in order to allow the bulging disc to recede and/or the facets to resume normal motion.

Bourdillon (1982) tells us that shortening of muscle seems to be a self-perpetuating phenomenon, which results from an overreaction of the gamma-neuron system. It seems that the muscle is incapable of returning to a normal resting length as long as this continues. While the effective length of the muscle is thus shortened, it is nevertheless capable of shortening further. The pain factor seems related to the muscle’s inability thereafter to be restored to its anatomically desirable length. The conclusion he reaches is that much joint restriction is a result of muscular tightness and shortening. The opposite may also apply, where damage to the soft or hard tissues of a joint is a factor. In such cases the periarticular and osteophytic changes, all too apparent in degenerative conditions, would be the major limiting factor in joint restrictions.

Restriction, which takes place as a result of tight, shortened muscles, is usually accompanied by some degree of lengthening and weakening of the antagonists. A wide variety of possible permutations exists in any given condition involving muscular shortening, which may be initiating, or secondary to, joint dysfunction, combined with weakness of antagonists. Norris (1999) has pointed out that:

The mixture of tightness and weakness seen in the muscle imbalance process alters body segment alignment and changes the equilibrium point of a joint. Normally the equal resting tone of the agonist and antagonist muscles allows the joint to take up a balanced position where the joint surfaces are evenly loaded and the inert tissues of the joint are not excessively stressed. However, if the muscles on one side of a joint are tight and the opposing muscles relax, the joint will be pulled out of alignment towards the tight muscle(s).

Such alignment changes produce weight-bearing stresses on joint surfaces and result also in shortened soft tissues chronically contracting over time. Additionally, such imbalances result in reduced segmental control with chain reactions of compensation emerging.

The authors believe that trying to make an absolute distinction between soft tissue and joint restrictions is frequently artificial. Both elements are almost always involved, although one may well be primary and the other secondary. The actual dysfunctional elements, as identified by assessment and palpation, require attention and in some instances this calls for treatment of intraarticular blockage, by manipulation, as described by Lewit. In others (the majority, the authors suggest) soft tissue methods, combined with assiduous use of home rehabilitation procedures, will resolve apparent joint dysfunction. In some instances both soft tissue and joint normalization will be required and the sequencing will then be based on the training, personal belief and understanding of the practitioner.

Benign hypermobility has long been recognized as a connective tissue variant, although at times it relates to specific disease processes such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and Marfan’s syndrome (Jessee et al 1980). A link between hypermobility and FMS has also been suggested (Wolfe et al 1990).

It is worth considering that the tender points, used to confirm the existence of FMS are located mostly at musculotendinous sites (Wolfe et al 1990). Tendons and ligamentous structures, in their joint stabilizing roles, endure repetitive high loads and stresses during movement and activity. A possible reason for recurrent joint trauma in hypermobile people may be the proprioceptive impairment observed in hypermobile joints (Hall et al 1995, Mallik et al 1994). Recurrent microtrauma to ligamentous structures in hypermobile individuals may well lead to repeated pain experience and could possibly trigger disordered pain responses.

Prevalence rates of hypermobility

• Caucasian adults 5% (Jessee et al 1980)

• Middle Eastern (younger) women 38% (Al-Rawi et al 1985)

• Hypermobility among Caucasian rheumatology patients is reported as ranging from 3% to 15% (Bridges et al 1992, Hudson et al 1995)

Various studies of hypermobility among Finnish schoolchildren (Jessee et al 1980), rural Africans (Crofford 1998) and healthy North American blood donors (Jessee et al 1980) failed to find a link with musculoskeletal problems. However, when rheumatology clinic patients have been evaluated there is strong support for a link between loose ligaments and musculoskeletal pain (Hall et al 1995, Hudson et al 1998, Mallik et al 1994).

Hudson et al (1998) in particular noted that what they termed soft tissue rheumatism (STR), i.e. tendinitis, bursitis, fasciitis and fibromyalgia, accounts for up to 25% of referrals to rheumatologists, while they report that the estimated prevalence of generalized hypermobility in the adult population ranges from 5% to 15%. In order to evaluate suggestions that hypermobile individuals may be predisposed to soft tissue trauma and subsequent musculoskeletal pain, a study was designed to examine the mobility status and physical activity level in consecutive rheumatology clinic attendees with a primary diagnosis of STR. Of 82 patients up to age 70 years with STR, 29 (35%) met criteria for generalized hypermobility. Hypermobile compared to non-hypermobile individuals reported significantly more previous episodes of STR, as well as more recurrent episodes of STR at a single site.

It is therefore possible that lax ligaments may result in structural joint instability, leading to repeated minor, or possibly more serious, traumatic or overuse episodes. A study of military recruits supports the idea that strenuous physical activity in hypermobile subjects results in musculoligamentous dysfunction (Acasuso-Diaz et al 1993).

There is increasing evidence that at least a subgroup of patients with soft tissue musculoskeletal pain, widespread pain or FMS are hypermobile and although hypermobility is not the only, or even the major, factor in the development of widespread pain or FMS, it seems to be a contributing mechanism in some individuals. Researchers such as Hudson et al (1998) suggest that physical conditioning and regular but not excessive exercise are probably protective.

Lewit (1985) notes that ‘what may be considered hypermobile in an adult male may be perfectly normal in a female or an adolescent or child.’ (Fig. 1.1).

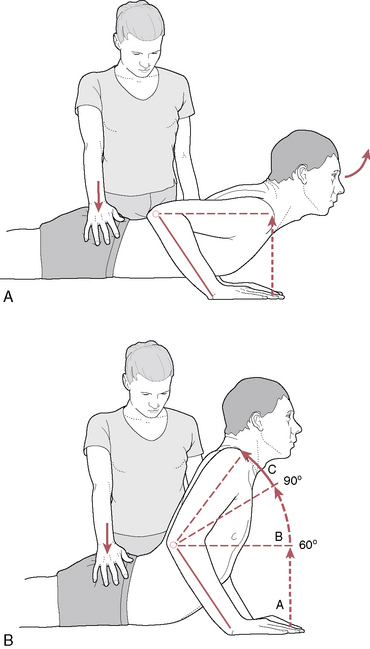

Figure 1.1 Testing lumbar extension with patient prone, showing ranges from the starting position shown in Fig. A to varying ranges as shown in Fig. B. A: normal to hypomobile; B: slight hypermobility

(adapted from Lewit 1985).

Greenman (1996) discusses three types of hypermobility.

• Those due to conditions such as Marfan’s and Ehlers–Danlos syndromes in which there is an altered biochemistry of the connective tissue, which often reflects as extremely loose skin and a tendency for cutaneous scarring (‘stretch marks’). There may also be vascular symptoms such as mitral valve prolapse and dilation of the ascending aorta.

• Physiological hypermobility as noted in particular body types (e.g. ectomorphs) and in ballet dancers and gymnasts. Joints such as fingers, knees, elbows and the spine may demonstrate greater than normal degrees of range of motion. Greenman reports that ‘Patients with increased physiological hypermobility are at risk for increased musculoskeletal symptoms and diseases, particularly osteoarthritis’.

• Compensatory hypermobility resulting from hypomobility elsewhere in the musculoskeletal system (Fig. 1.2). Patients with compensation of this sort are very likely to present with painful joint and spinal symptoms. Greenman, discussing the spine, points out that ‘Segments of compensatory hypermobility may be either adjacent to or some distance from the area(s) of joint hypomobility. Clinically there also seems to be relative hypermobility on the opposite side of the segment that is restricted’. (See the discussion of the ‘loose/tight’ phenomenon in Volume 1, Chapter 8.)

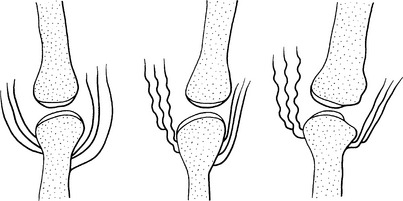

Figure 1.2 Muscular imbalance altering joint mechanics. A: symmetrical muscle tone; B: unbalanced muscle tone, with hyper- and hypomobile elements contralaterally; C: joint surface degeneration resulting from this imbalance

(reproduced with permission from Chaitow & DeLany 2008).

• Because it is often the hypermobile segment which is most painful, Greenman points out that the practitioner can get ‘trapped into treating the hypermobile segment and not realizing that the symptom is secondary to restricted mobility elsewhere’. He confirms that ‘In most instances hypermobile segments need little or no direct treatment but respond nicely to appropriate treatment of hypomobility elsewhere’.

• Sclerosing type injections are frequently used by some practitioners to increase connective tissue proliferation and enhance stability (see notes on prolotherapy in Chapter 11, Box 11.6. p. 327).

See also Box 1.4 in this chapter.

Box 1.4 Algometer usage in trigger point treatment

(Note: These concepts are discussed more fully in Volume 1, Chapter 6.)

There are several ways in which the use of a pressure gauge (algometer) can assist in assessment and treatment of myofascial pain, as well as in the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.

In evaluating people with the symptoms of fibromyalgia, a diagnosis depends upon 11 of 18 specific test sites testing as positive (hurting severely) on application of 4 kilograms (approximately 10 pounds) of pressure (Wolfe et al 1990). The 18 (nine sets of bilateral) points tested in diagnosing fibromyalgia are common trigger point sites. In order for a diagnosis to be made 11 of the tested points need to be reported as painful, as well as the patient reporting a number of associated symptoms (Chaitow 2010).

1. At the suboccipital muscle attachments to the occiput (close to where rectus capitis posterior minor inserts)

2. At the anterior aspects of the intertransverse spaces between C5 and C7

3. At the mid-point of the upper border of upper trapezius muscle

4. At the origins of supraspinatus muscle above the scapula spines

5. At the second costochondral junctions, on the upper surface, just lateral to the junctions

6. 2 cm (almost an inch) distal to the lateral epicondyles of the elbows

7. In the upper outer quadrants of the buttocks, in the anterior fold of gluteus medius

8. Posterior to the prominence of the greater trochanter (piriformis attachment)

9. On the medial aspect of the knees, on the fatty pad, proximal to the joint

Establishing a myofascial pain index

When assessing and treating myofascial trigger points the term ‘pressure threshold’ is used to describe the least amount of pressure required to produce a report of pain and/or referred symptoms.

When treating trigger points it is also useful to know whether the degree of pressure required to produce typical local and referred/radiating pain changes before and after treatment. For research and clinical purposes, an algometer can be used to standardize the intensity of palpation or to measure the degree of pressure used to evoke a painful response over selected trigger points.

• An algometer can be used as an objective measurement of the degree of pressure required to produce symptoms involving trigger points and the surrounding soft tissues.

• It also helps the practitioner in training herself to apply a standardized degree of pressure and to ‘know’ how hard she is pressing.

• Researchers (Hong et al 1998, Jonkheere & Pattyn 1998) have used algometers to identify what they term the myofascial pain index (MPI).

• In order to achieve this, various standard locations are tested (for example, some or all of the 18 test sites used for fibromyalgia diagnosis, listed above).

• Based on the results of this (the total poundage required to produce pain in all the points tested, divided by the number of points tested), a myofascial pain index (MPI) is calculated.

• The MPI can be used to suggest the maximum pressure required to evoke pain in an active trigger point.

• If greater pressure than the MPI is needed to evoke symptoms, the point may be regarded as ‘inactive’.

• At the very least, use of an algometer can help the practitioner to appreciate how much pressure she is using and can give rapid feedback of changes in pain perception before and after treatment, whatever form that takes.

Additionally, as mentioned above and discussed elsewhere within this text, there may be times when trigger points may be serving in a protective or stabilizing role in a complex compensatory pattern. Their treatment may then be best left until after correction of the adaptational mechanisms that have caused their formation. Indeed, with correction of the primary compensating pattern (forward head position and tongue position, for instance), the referred pain from trigger points (in this case, within masticatory muscles) may spontaneously clear up without further intervention (Simons et al 1999).

Q. When should postural re-education and improved use patterns (e.g. sitting posture, work habits, recreational stresses, etc.) be addressed?

A. The process of re-education and rehabilitation should start early on, through discussion and provision of information, with homework starting just as soon as the condition allows (e.g. it would be damaging to suggest stretching too early after trauma while consolidation of tissue repair was incomplete or to suggest postures which in the early stages of recovery caused pain). The more accurately the individual (patient) understands the reasons why homework procedures are being requested, the more likely is a satisfactory degree of concordance. Reinforcement of the concepts being taught within the treatment room has great value. Suggesting or providing educational material (book, brochure, website, DVD, etc.) that is written for the patient’s comprehension level, will be appreciated by some and ignored by others. What works for one person may not be enjoyed (and, therefore, not used) by another. Overload of too much information is to be avoided. Overwhelming the mind has a similar effect as too much therapy that is applied too quickly; lifestyle changes need time for adaptation and integration. Pacing the information to match (parallel) the treatment room discussion has inherently more value than expecting a lot of moderate changes all at once.

Q. Should factors other than manual therapies be considered?

A. Absolutely! The need to constantly bear in mind the multifactorial influences on dysfunction can never be overemphasized. Biochemical and psychosocial factors need to be considered alongside the biomechanical ones. For discussions on this vital topic, see Essential Information before chapter 1 in this volume and also Volume 1, Chapter 4 for details of the concepts involved.

Acasuso-Diaz M., Collantes-Estevez E., Sanchez Guijo P. Joint hyperlaxity and musculoligamentous lesions: study of a population of homogeneous age, sex and physical exertion. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32:120-122.

Al-Rawi Z.S., Adnan J., Al-Aszawi A.J., et al. Joint mobility among university students in Iraq. Br J Rheumatol. 1985;24:326-331.

Baldry P. Acupuncture, trigger points and musculoskeletal pain, ed 3. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

Bourdillon J. Spinal manipulation, ed 3. London: Heinemann, 1982.

Bridges A.J., Smith E., Reid J. Joint hypermobility in adults referred to rheumatology clinics. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51:793-796.

Chaitow L. Muscle energy techniques, ed 3. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007.

Chaitow L. Fibromyalgia syndrome: a practitioner’s guide to treatment, ed 3. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2010.

Chaitow L., DeLany J. Clinical application of neuromuscular techniques, volume 1, the upper body, ed 2. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2008.

Chaitow L., Bradley D., Gilbert C. Multidisciplinary approaches to breathing pattern disorders. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.

Crofford L.J. Neuroendocrine abnormalities in fibromyalgia and related disorders. Am J Med Sci. 1998;6:359-366.

Garland W. Somatic changes in hyperventilating subject. Presentation at Respiratory Function Congress. 1994. Paris

Greenman P. Principles of manual medicine, ed 2. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1996.

Grieve G. The masqueraders. In Boyling J., Palastanga N., editors: Grieve’s modern manual therapy of the vertebral column, ed 2, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994.

Hall M.G., Ferrell W.R., Sturrock R.D., et al. The effect of the hypermobility syndrome on knee joint proprioception. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:121-125.

Hong C.Z. Algometry in evaluation of trigger points and referred pain. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 1998;6:47-59.

Hong C.Z., Chen Y.N., Twehous D., et al. Pressure threshold for referred pain by compression on the trigger point and adjacent areas. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 1996;4:61-79.

Hudson N., Starr M., Esdaile J.M., et al. Diagnostic associations with hypermobility in new rheumatology referrals. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:1157-1161.

Hudson N., Fitzcharles M.A., Cohen M., et al. The association of soft tissue rheumatism and hypermobility. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:382-386.

Janda V. In. Grant R., editor. Physical therapy of the cervical and thoracic spine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1988.

Jessee E.F., Owen D.S., Sagar K.B. The benign hypermobile joint syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:1053-1056.

Jones L. Strain and counterstrain. Colorado Springs: Academy of Applied Osteopathy, 1981.

Jonkheere P., Pattyn J. Myofascial muscle chains. Brugge, Belgium: Trigger vzw; 1998.

Kappler R. Osteopathic considerations in diagnosis and treatment. In: Ward R., editor. Fundamentals of osteopathic medicine. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins, 1996.

Lee D. The pelvic girdle: an approach to the examination and treatment of the lumbopelvic-hip region, ed 3. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Lewit K. The muscular and articular factor in movement restriction. Manual Medicine. 1985;1:83-85.

Lewit K. Manipulative therapy in rehabilitation of the locomotor system, ed 2. London: Butterworths, 1992.

Mallik A.K., Ferrell W.R., McDonald A.G., et al. Impaired proprioceptive acuity at the proximal interphalangeal joint in patients with the hypermobility syndrome. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:631-637.

Norris C. Functional load abdominal training (part 1). Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 1999;3(3):150-158.

Petty N. Neuromusculoskeletal examination and assessment: a handbook for therapists. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

Simons D., Travell J., Simons L. Myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual, vol 1, upper half of body, ed 2. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

Steiner C. Osteopathic manipulative treatment – what does it really do? J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1994;94(1):85-87.

Vleeming A., Mooney V., Stoeckart R. Movement, stability & lumbopelvic pain: integration of research and therapy, ed 2. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2007.

Wolfe F., Smythe H.A., Yunus M.B. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160-172.