Chapter 5 Social behavior

Chapter contents

Social organization

Social interactions between horses have been the focus of several recent studies. This is good news for domestic horses because by understanding the relationships between horses, humans can learn to build a better understanding with their equine companions. That said, there are limitations on the extent to which horses use elements of their social repertoire to communicate with humans.1 Fundamentally, we do well to remind ourselves of this, especially when riding since, clearly, horses never mount one another to take a ride.

As the nature of social hierarchies in free-ranging horses, the effects of domestication and the significance of behavioral and social needs are better understood, our ability to comment on equine welfare issues is necessarily enhanced. For example, studies of groups of free-ranging horses have provided information on the roles of stallions, mares and juveniles within their natal groups (Fig. 5.1). This may provide the rationale for single-sex grouping of horses in some domestic contexts, especially where social flux is constant and agonistic interactions must be modulated for the sake of horse safety. Thoughtful planning of social groups can help to ensure normal social development, reduce some of the undesirable effects of pair-bonding on ridden work and minimize injuries from conspecifics in the paddock. It is usually better to find the optimal social milieu for horses than take the ‘safe’ option of isolation in a paddock or, worse still, a stable.2

Figure 5.1 Feral horses and herds that receive minimal management, such as these Konik horses in Oostvaarders Plassen, the Netherlands, provide critical information on normal horse behavior.

Domestic horses are not the only beneficiaries of studies of free-ranging equids, since the humane control of feral horses is also facilitated with this sort of information. For example, given the importance of a stable social group, the relocation and confinement of feral horses, while sounding reasonably simple, is likely to modify current social structure and range use, ultimately leading to fights and injuries in the short term and the need for more intensive management in the longer term.3

Groups of horses

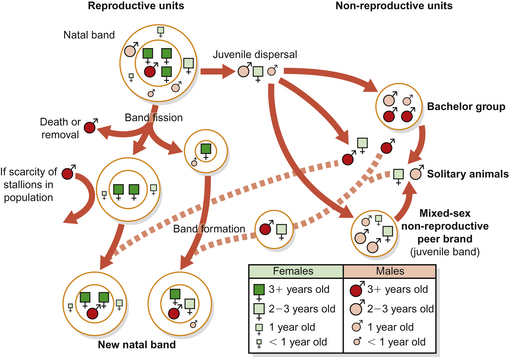

Other than occasional solitary individuals (which are more often than not transiently drifting between groups), two main groupings of horses occur within herds: the natal band (or birth band or family group) and the bachelor group (Fig. 5.2).4 Traditionally, horse herds are thought of as harems, comprising one stallion, his mares and foals and juveniles. This simplistic view fails to embrace the leadership role of mares and the context-specificity of the stallion’s place in the social order.

In a group of horses, the lead animal shows the way to resources, such as water, saltlicks and rolling sites, as well as initiating activities such as grazing or resting. This individual is often an older experienced mare but, depending on the context, the stallion may also direct its herd by herding and snaking, for example when he detects predators or competitors. Increasingly, the importance of mares as the functional core of the group is being recognized, with 25% of them staying permanently in their original natal band4 and with matrilineal dynasties spanning generations. Mares and their filly foals often share strong bonds and this affiliation may facilitate vertical transmission of information about optimal use of a home range. Those mares that disperse into a fresh band often remain within it for life. It is important to note that the stallion may not always be the highest ranking member of the natal band.5–7 Similarly, sex has been demonstrated to be a poor predictor of rank in foals.8

Bands with more than one stallion are not uncommon. Subject to the above, stallions within these groups establish a dominance hierarchy that helps to define roles. If there are several stallions associated with the family band, the dominant stallion copulates more than subordinate stallions.4 Band cohesion is a task shared by stallions in multi-stallion bands but the subordinate males tend to herd and occasionally mate with the lower-ranking females. One study noted that mares are more likely to leave single-stallion harems and that therefore harems with several stallions are generally more stable.9

Linklater10 defines a natal band as a stable association of mares, their pre-dispersal offspring and one or more stallions who defend and maintain the mare group, and their mating opportunities, from other males year round. For example, in New Zealand’s Kaimanawa ranges, the horse population has a social structure like that of other feral horse populations, with an even adult sex ratio, year-round breeding groups (bands) with stable adult membership consisting of 1–11 mares, 1–4 stallions, and their predispersal offspring, and bachelor groups with unstable membership.3 Changes in the adult composition of natal bands are rare (e.g. Miller11 suggests 0.75 adult changes per year). However, harems may split into smaller groups based on social attachment, when fodder becomes scarce.12

Found in all free-ranging horse populations, the bachelor group comprises males that have dispersed from natal bands. Although most colts leave the natal band at around the birth of a sibling, or when there is a shortage of playmates or food, some remain.13 However, as they mature and begin to represent a threat to a resident stallion’s mating rights, pubescent males may occasionally be ostracized from their natal band. More generally, colts gravitate to bachelor groups because that is where they find many potential play partners. Bachelor groups also provide sanctuary to older stallions, including some that have been unsuccessful in defending their bands from other stallions.14 Bachelors live in their groups adjacent to natal bands, waiting for opportunities to capture dispersing mares, perform sneak matings, herd away mares and to challenge natal band leaders. For this reason, membership of the bachelor band is subject to the greatest flux during the breeding season. Despite the companionship it offers, bachelor groups are literally full of competitors that engage in agonistic encounters that may persist over several months and may end in dispersal.15 It is therefore perhaps predictable that young stallions usually spend some time alone before forming their own harems.13 The bachelor group provides valuable physical and social learning opportunities for its transient members. In juveniles there is a relationship between time spent in the bachelor group and latency to form a harem.13

Role of stallions in natal band cohesion

The main roles of a resident stallion involve monitoring and maintaining the integrity of his band and protecting it from predators and other stallions that may attempt to steal or perform sneak matings with mares and fillies. The reproductive success of a harem stallion is limited not least by his ability to prevent such matings.16 Harem stability is not affected by the size of the harem nor by the age of the stallion, but is thought to be enhanced by the presence of subordinate stallions attached to the harem.9 Depending on the terrain, the stallion will protect his band by patrolling a radius of 10–15 m around the group as they move through the home range.6 For this reason natal band stallions are less likely than mares, juveniles or bachelors to form pair bonds. The relationships they form tend to be heterosexual (usually with all adult females in the natal band) or paternal.17

Being less timid than mares and fillies,18 stallions and colts usually take the initiative when the band encounters a potential threat. That said, the stallion’s response to a challenge depends on whether the cause of the threat is a predator or another stallion. If a predator threatens, the stallion will herd his group together and lead or drive them away from the threat using snaking gestures (Fig. 5.3). Feist19 noted that in 77% of band movements, the stallion was either driving or leading the group. Stallions sometimes herd wandering foals back to the band and protect them from danger.20

Figure 5.3 Snaking behavior used by a stallion to move other horses, especially members of his natal band.

By placing himself between the band and a predator the stallion can reduce the fragmenting effects such stimuli can have on the group. The role of the stallion in responding to potential predators is illustrated by the report that Camargue foals born into bands in which two stallions have an alliance are 20% more likely to survive than those in single-stallion bands because of reduced predation.21

If the threat is from another stallion, the initial response by the band’s stallion will be to attempt to chase the challenger away. Agonistic behaviors are discussed later, but the resident stallion’s motivation to fight depends on a number of variables summarized in a notional equation that forms the central tenet of game theory (Fig. 5.4).22 Whenever two horses dispute access to any resource, both must weigh up the value of the resource, the cost of defending it and their ability to retain it (also known as their resource-holding potential). Without performing any calculations as such, the would-be protagonists (a and b) compare

Figure 5.4 Stallions (a) and (b) approaching one another spend time assessing each other’s fitness and readiness to fight.

where: V is the value of the resource to that individual; RHP is the resource-holding potential of that individual; C is the cost of a fight to that individual. Factors on which these variables depend are given in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Game theory variables predicting conflict between horses, and factors on which the variables depend

| Variable | Factors include |

|---|---|

| Value | Experience of the resource, investment in the resource, short-term and long-term future needs |

| Resource-holding potential | Size, physical fitness (as evidenced by display used when the challenge is detected), ability to deceive observers, fighting experience and number of individuals involved in the dispute |

| Cost | Risks of being injured (with consequent risk of infection at the site), killed or displaced from natal band |

This theory helps to explain why interactions between the resident stallions of two interfacing bands are less intense than those between a resident stallion and an interloping bachelor. The latter has a lower cost to pay for fighting more intensely since he is already outside a core group. The value of the home range is greater for the resident than the intruder so the resident may be more likely to persist in combat. This helps to explain why the forays of bachelors into the home range of natal bands are only rarely successful.

Snaking and herding are most likely to be seen in domestic contexts when the stallion is introduced to a group or when an existing family group is moved to a new pasture.23 After either of these interventions the stallion’s response generally returns to baseline levels by the third day.23 The addition of new mares to an established natal band does not induce herding of the original mares. However, primarily because they are chased by the stallion for up to 3 days, the introduced mares are kept at a distance (of approximately 8–12 mare lengths) from the original mares.23 Band integrity is further enhanced by a harem stallion when he facilitates bonding between mares and their neonatal foals by keeping other conspecifics away from them. Again, snaking and herding may be used for this purpose.

Despite the benefits of having the company of a stallion, band members lose some of their freedom. In the absence of a stallion, mares mutually groom more, form more stable pair bonds and have a better-developed social order.24

Role of mares in natal band cohesion

The chances of inbreeding between stallions and their daughters is reduced by the experience of having lived together before the filly’s maturity, a factor thought to prompt migration of fillies from their natal band.25 While 75% of the fillies disperse to other bands, the females that remain are the most fixed and stable members of most natal bands, often taking leadership roles in governing the band’s daily activities. Although regarded as the resident core of the equine family group, mares will disperse from natal bands notably when resources are scarce: e.g. up to 30% of adult females have been observed changing harems during the winter.9

Affiliative behavior between females is important because mares of an established band remain together even in the absence of a stallion.26 We should never underestimate the strength of social bonds among mares. Indeed there are anecdotal reports of mares abandoning their own foals to reach the comfort of their herd mates. These affiliations may have their origins in foal associations since fillies tend to spend more time with other fillies than with colts.27 Daughters also tend to remain closely associated with their dams.17,28

As discussed in detail later in this chapter, the concept of hierarchy is controversial since some commentators fear that it legitimizes human domination of and violence toward horses. However, as we use clearer terminology that provides the most parsimonious explanation of effective and safe human–horse and horse–human interactions and thus advances the welfare of horses, we must not deny the importance of social order, since it is highly adaptive in reducing intraspecific aggression. The rank of a mare has a predictive effect on her role in band cohesion. For example, as a reflection of the investment they have made in the group, dominant mares are more likely to defend the area around the group. Although territorial behavior is an irregular feature of the equine ethogram,29 in some free-ranging populations, such as those in Shackleford Banks on the eastern coast of the USA, which show defense of a territory rather than simply maintenance of the integrity of the band,30 higher-ranking mares within the natal band are more often involved in mutual grooming with the resident stallion, while lower-ranking mares are the chief recipients of his snaking and herding attention when he rounds up the band. Most adult mares in a natal band will contribute to band cohesion by responding to the sound of the resident stallion’s call.31

Role of juveniles in natal band cohesion

In a natal band, the juveniles issue the least amount of aggressive behavior and conduct the most non-agonistic behavior.7 One of the main behaviors of foals is play: it is very important that they learn how to interact with one another and to establish pair bonds (see Ch. 10). Play in foals is unrelated to rank. So, the play-rank order of foals, as measured by the number of times a foal left a bout of play, is not significantly correlated with social rank order determined by agonistic interactions.32 Yearlings and two- and three-year-olds continue to be involved in play activity but are also seen nipping and wrestling each other as they consolidate their social order and as they practice herding or fighting for adulthood.

Group size and home ranges

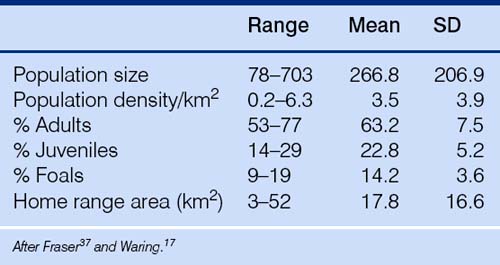

Herds of horses may be as large as 600 (Machteld van Dierendonck, personal communication 2002). Bands within herds form relatively stable nuclei33–35 that are often at their most discrete when resting but may graze in close proximity to one another and usually unite when fleeing from a predatory threat. Band size tends to vary with population density. For example it can range from 12.3 in Shackleford Banks,30 with a population density of 11 individuals/km2 to 3.3 in Wassuk Ridge, in the Nevada Desert, with a population density of 0.1.36 Because of the terrain and its resources, horse density in a given ecological sector can vary: e.g. while the population density in the Auahitotara of New Zealand averaged 3.6 horses/km2, it ranged from 0.9–5.2 horses/km2 within different zones.3 Group size therefore is dependent on the density and pattern of distribution of resources, and this is why, when external resources are provided, groups can become larger than those observed in the free-ranging state. For example, in working ponies that are seasonally managed on a free-living basis, groups of 30 or more can exist.37 Island populations, such as those on Sable Islands and Shackleford Banks, have higher population densities than those with fewer limitations on their ability to spread.30,38 Demographic data on feral horse groups in North America are given in Table 5.2.

Home ranges incorporate grazing sites, waterholes, rolling sites, shade, windbreaks and refuges from insects and can vary in area from 0.9–52 km2.39 Exploitation of the home range depends on numerous variables including the climate, the season, predation risk and the prevalence of biting insects. For example, Auahitotara horses generally avoid high altitudes, southern aspects, steeper slopes, bare ground and forest remnants.3 Instead they tend to occupy north-facing slopes (because they have warmer aspects) with short vegetation and zones with well-nourished swards. In spring and summer when subsistence is less of a challenge and there is less need to forage in hostile terrain, they tend to be found on gentler slopes.3

Horse populations do not use all parts of their home range equally since the grazing is rarely of uniform value and the emergence of latrine areas is normal (see Chs 8 and 9). Thus bands tend to spend much of their time in relatively small focal areas within the home range.17 Natal bands often shift with the season such that in spring they gravitate to river basin and stream valley floors for the beginning of foaling and mating and, when there is a chance of frost, to higher altitudes in autumn and winter.3 The appeal of certain areas changes with the season. For example, whereas during the winter months they may avoid standing in water, during the summer months horses may be driven into surf or shallow bays by biting insects. Equally, the cooling effect of rolling and standing in water should not be underestimated. That said, in some groups of horses no pattern of cyclical use of areas has emerged.17 Since the use of terrain seems to be initiated by leading members of the group and since a change of leader may bring a change in a band’s use of resources, this finding may have arisen because behavioral observations were coincidentally made at a time of flux in the band’s composition or social order.

Social behavior in feral horse populations is more common than territorial behavior, in that if one band of horses encounters another, any defensiveness shown usually appears to be an attempt to maintain the integrity of the band rather than to defend a site.17 Although the home range of one natal band often overlaps entirely with the home ranges of others, natal bands and bachelor groups are loyal to undefended home ranges with central core use areas.3

In cases where home ranges overlap, a social order among groups can be observed that allows the predictable displacement of subordinate (usually smaller) bands and individuals from shared resources such as watering-holes. Although linked to the size of the group, its relative rank compared with others is not a function of the number of males it contains.34 This is illustrated by the deference exhibited by bachelor groups to natal bands and by the way in which the rank of a bachelor is enhanced once he has acquired a mare.34 Disputes between bands are generally resolved by interaction between one or occasionally two high-ranking representatives from each. The remainder of both bands typically look on and await the outcome before accessing resources in an order determined by their representatives.34

Social order

The establishment of defined social status within any group of equids promotes stability within the band. A stable social order within the band decreases the accumulative amount of injury by allowing threats of kicks and, perhaps more importantly, bites to replace the aggressive responses themselves.7

Each horse’s position within the band is held through a blend of aggression and appeasement behavior. Aggressive behavior can be biting, kicking, circling and displacement, but the most common response to a competitor is a threat to kick or bite. Rank is determined not only by threats issued but also deference to threats received. Such submission may involve lowering the head and averting the gaze. Unfortunately, the intraspecific harmony seen in stable horse groups (facilitated largely by deference) is sometimes hijacked by humans seeking to justify the use of force to render horses submissive.1

Houpt et al40 found that although individual rank order is unidirectional it may not be linear throughout the group. Thus A may dominate B who may dominate C, but C may dominate A.40 This facilitates the formation of so-called social triangles. While rank orders are generally linear in the top and bottom of a band’s organization, most triangles occur in the middle.41

Also one must consider the role of protected threats that allow individuals to enhance their rank by associating with a higher ranking band member – for example as seen in foals that attain rank enhancement when with their dams. Thus the possible influence of the dam may help to explain why Icelandic yearlings often have a higher rank than their 2-year-old siblings (Machteld van Dierendonck, personal communication 2002).

If a social order were not developed and maintained, each horse would need to affirm its rank by increasing levels of aggression during every dispute with a conspecific over a resource. Without a hierarchy, injury and distress associated with social flux may have reproductive costs, e.g. the rate of conception might be decreased and there could be an increase in the rate of fetal and foal mortality.42 In general, a social structure is important for organization, especially during times of emergency such as when a predator approaches (Fig. 5.5). A defined social structure based on affiliative relationships allows the band to mount an appropriate response, be it fight or flight, as the lead animal rises to the defense of the group or herds it together to escape. Social order per se is highly adaptive. However, the concept of hierarchy unsettles some applied ethologists because, being resource-dependent, it is complex and therefore the outcomes of agonistic interactions between two or more individuals are sometimes difficult to predict but also because it has been used to justify fear-eliciting activities within the human–horse dyad.

Figure 5.5 A mare moves forward to defend her group by attacking an approaching dog.

(Photographs courtesy of Michael Jervis-Chaston.)

The empirical determination of rank is complex and not easily predicted. Height or weight or both have been found to correlate with rank in many studies43–45 but not all.5,41 Age more usually shows a correlation with rank in studies of feral E. caballus6,43,46 and E. przewalski47 but again this is not always the case.42 It is appropriate that age should contribute to social status since it is likely to reflect experience in dealing with local challenges and a wealth of knowledge about how best to exploit the resources in the home range.7 That said, in their dotage the oldest mares may relinquish leadership but occupy a beta position, much more elevated than their body condition would suggest. Perhaps this reflects some sort of respect earned earlier in life (Machteld van Dierendonck, personal communication 2002). In managed herds, the length of residency within a band also contributes to the determination of rank.41,48 In geldings, rank seems strongly influenced by an individual’s position in the social hierarchy at the time of castration (see Ch. 11).

Either sex can out-rank the other because there is little sexual dimorphism in the sizes of hooves and teeth, which are a horse’s main weapons.6 Stallions’ ranks are very much context-dependent. They may rarely dominate, as they have less contact with the band than female peers because of their need to patrol around rather than within the band. Furthermore they do not participate in many aggressive encounters if they enter the band chiefly during sexual situations.6 Therefore when a youthful stallion secures mating rights in a band containing mares older than himself, the oldest yet healthiest mare will tend to prevail in a leadership role. Although over 80% of threats are directed down the dominance hierarchy,32 the use of the term ‘dominance’ is somewhat controversial since some authors highlight avoidance behavior on the part of subordinates as being the main activity necessary to maintain the order. In view of this, it has been argued37 that avoidance order is a better measure of the social system than the ‘aggression order’.

In the process of learning to recognize their place in the hierarchy, yearlings receive the largest number of attacks (46% according to Keiper & Receveur7). Significant positive correlations have been found between rank of mares and foals and the rate at which they directed aggression to other herd members.8

As suckling foals play away from their dams, they establish a hierarchy based largely on birth order such that there is a linear relationship between age and social position.7,8 Although weaning tends to have a disruptive effect on the ranks of foals (so that birth order no longer correlates with rank), significant correlations have been found between mare rank and the rank of foals both before and after weaning.8,32 This would suggest that the influence of the dam is relatively constant over time.8

Since the adult offspring of a high-ranking mother does not necessarily become high-ranking, it cannot be said that resource-holding potential is purely genetic.6 Status is a learned relationship between two individuals, and learning plays a role in the development of effective displacing strategies, which can include deceptive responses such as bluffing. Additionally there may be heritable behavioral predispositions in the high-ranking dynasties within a herd. Although offspring may learn aggressive behavior from their mothers this is challenged in part by evidence of inverse correlations between aggression rates and rank in foals.32 Perhaps they have only to learn how to impose their rank rather than doing so frequently. One alternative is that status is bestowed upon the foals of high-ranking mares simply by association with their dams, since mares may assist their foals in agonistic encounters with other foals.8 It is acknowledged that foals share their mother’s rank while she is in close proximity17 but that they are more likely to show displays thought to be deferential such as snapping (tooth-clapping, yawing, champing, yamming; Fig. 5.6) to adults when beyond her protection.43 Furthermore the rates of aggression towards foals rise with weaning as the mare’s support is withdrawn.8 The relative contribution of environmental and genetic factors will be better understood when the influence of non-biological mothers can be measured from studies of foals that have been transferred as embryos or cross-fostered after birth.

Figure 5.6 Youngster showing snapping response to an older horse.

(Photograph courtesy of Francis Burton.)

Although mares may undergo significant changes in social behavior at the time of foaling,49 no coincident changes in social status have been reported with foaling,43 so mares with foals at foot do not necessarily rank higher than a mare without a foal.

The effect of rank on behavior

By definition, with higher rank comes priority access to most resources. In every dispute the rank of protagonists correlates with their resource-holding potential and contributes to the prediction of the outcome. However, rank alone is not a simple, absolute predictor, since game theory applies, too. Therefore the outcome must also remain a function of the value of the resource (i.e. the motivation to acquire the resource) and the cost of any fight to possess it. For these reasons rank is also context-dependent, especially in stallions.

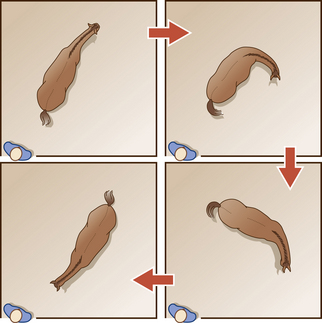

Rank has been correlated with the priority bestowed on those horses that gain first access to maintenance resources such as resting sites and watering holes,34 unless they have been distracted by having to repel another band. Conversely, rank dictates the order in which bachelors eliminate on one another’s excrement,24 and all bands use rolling sites50 (Fig. 5.7). Rank influences social dynamics within a band, including the selection of nearest neighbors and mutual grooming partners.46

The rank of an individual horse does not influence its sociability rate in any group.8 However, the debate continues about the role of the higher-ranking partner in mutual grooming pairs, with evidence that high status animals may be both more likely46 and less likely43 to start a bout when grooming started asynchronously.

Despite the relationship between age and rank, difference in the ages of band members influences social networks. Bonded pairs with less difference in age that demonstrate frequent grooming, usually remain in close proximity to one another, beyond the effects of rank and kinship.51 Additionally, middle-ranking horses tend to be more frequently in the close vicinity of another horse than high-ranking or low-ranking horses.41 Again, the mid-ranks are also characterized by social triangles.41

There are a number of ways in which social rank affects reproductive behavior. Just as stallions can reject maiden mares, they have been reported to select high-ranking estrous mares for mating when offered a choice.52 Males outside the natal band and low-ranking (juvenile) males within it are seldom able to mate with mature mares unless by sneak matings, because the resident stallion consorts with these mares when they are in estrus. The peripheral and subordinate stallions can therefore usually mate only with lower-ranking mares with reduced biological fitness. The trade-off for these males is that they have not invested time in protecting these females. For mares, elevated rank means they are less likely to be harassed by these males seeking sneak matings. As they solicit the attentions of the senior stallion they may also be seen chasing away subordinate females that would otherwise divert his attention.50

The benefits of high rank in terms of biological fitness are clear. For example, since the foals of high-ranking mares may grow bigger and faster than other foals in the natal band, they may breed earlier and the colts among them may be more likely to gain a harem.8,53 Other, less favorable associations with high rank are becoming better understood, with studies in wild dogs indicating that rank is positively correlated with cortisol concentrations.54 In horses, one might predict this to be the case in herd leaders because of the associated burden of having to maintain band integrity and investigate potentially dangerous stimuli. Similarly, recent data demonstrate that the foals of higher-ranking mares are more likely to develop oral stereotypies than foals of middle- or low-ranking dams.55 It is speculated that this may reflect the influence of mares’ behavior towards foals prior to weaning or may relate to the nature of the mare–foal bond and effects of severance at weaning. Low-ranking mares and those in poor condition are more likely to have female foals, which are better able to reproduce than colts from dams on marginal nutrition.56

Certainly this is an area that merits more study. The role of rank in competitive success of race and sports horses continues to fascinate both ethologists and punters alike. It is possible that high-ranking animals in a race allow others to take the lead and with it the potential risks of what may lie ahead. This, however, may be offset by the reluctance of subordinate animals to overtake them, an abiding argument for the use of blinkers that may reduce the ability of horses to detect threatening behaviors from conspecifics as they overtake them in a race.

Measuring rank

The factors that influence rank are complex, as is determining rank within a group of horses. The absence of an established protocol for measuring social hierarchies in horses accounts for the lack of consensus among studies. Perhaps because there are fewer complexities such as social triangles and because of the complete absence of mare–foal dyads, measuring rank is easier in all-male groups than in natal bands.24 The importance of deference displays by subordinate horses when withdrawing from disputes over resources is now being recognized, so instead of establishing hierarchy solely on the basis of threats given,7 the trend is towards including submissive gestures32,45 and calculating rank only from submission data.8

It is generally true that one can best see the dominance relations between individuals at the site of limited resources: water holes, saltlicks, sandy places to roll, shelter, etc. It is natural for horses to attempt to displace each other as they compete for affiliates, mates, food, salt or water. For this reason, some studies of hierarchy tend to record all occurrences of agonistic behavior between pairs of subjects during feeding of supplemental grain.8 However, the desire to acquire or defend food pellets in competitive situations is not necessarily the same for all individuals involved. Additionally, rank in an isolated dyad is not necessarily a true reflection of what applies in an unmanipulated group that may feature coalitions, social triangles, leadership and defense.

Because simply recording the outcome of a bout is an inelegant measure of rank, submissive and aggressive behaviors should be analyzed in detail. This approach has shown that agonistic responses involving the head are related to offensive behaviors, while the hindquarters are used both offensively and defensively.41 So, when scoring a dispute between two horses to determine rank, it is advisable to summate bites and bite threats separately from kicks and threats to kick because the latter may be less useful for determining hierarchy.41

Affiliations

Under free-range conditions, even where the territory is extensive, group bonding is important to the extent that horses maintain continual visual and, to some extent olfactory, contact with each other.37 A central mechanism of band cohesion is the establishment of affiliations, notably pair bonds and mare–foal bonds.57 Pair bonds in bachelor groups are generally weaker than those observed in natal bands and become more tenuous as bachelors mature and are driven to establish reproductive relationships.17

While domestic horses generally group together according to certain sex or sex–age classes – adult mares, adult geldings, foals, juveniles – mares sometimes socialize according to their reproductive state: pregnant, postpartum and barren (Machteld van Dierendock, personal communication 2002). Most horses have one or more preferred associates with whom they maintain closer proximity than with other herd members.46 The resilient bonds between such paired affiliates are of particular importance among equids and are demonstrated by reciprocal following, mutual grooming and standing together (Table 5.3).58 In youngsters, they are demonstrated chiefly by play. The cardinal signs of stability among groups of horses include group activities such as rolling and trekking and mutual maintenance behaviors including insect control and grooming.

Table 5.3 Features of the ethogram (as described for bachelor bands15) characteristic of stable groups

| Response | Description |

|---|---|

Trekking  |

Two or more animals moving together, typically following one another |

Mutual grooming  |

Two horses standing beside one another, usually head-to-shoulder or head-to-tail, grooming each other’s neck, mane, rump or tail by gentle nipping, nuzzling or rubbing |

Although one recent study showed that a foal’s sex had no significant effect on the choice of preferred associate,8 others have found that foals tend to preferentially associate with other foals of the same sex.32,59 Both before and after weaning, foals associated preferentially with the foal of their dam’s most preferred associate.8 As further confirmation of the influence of the mare on the social behavior of the foal, it has been reported that the sociability rates of mares and their foals are correlated prior to weaning but not after.8

Horses tend to bond with conspecifics of similar age and rank.45,46 This means that in biological terms they associate with their closest competitors, and this may account for ongoing disputes, however mild, over resources. Preferred associates receive more total aggression than do other herd members, but proportionately more of the aggression directed against preferred associates is mild, such as laying back of the ears, when compared with more severe aggressions, such as kicking.45 This is supported by a study that compared 2-year-old colts that had been group-reared and single reared for 9 months.60 Whereas group-reared colts tended to make more use of subtle agonistic interactions (displacements, submissive behavior), more aggressive behaviors, i.e. bite threats, were recorded in the group of singly reared colts.60 Increasingly, therefore the concept of a hierarchy based on dominance and subordination has been challenged by one based on tolerance and attachment.58

Social groupings have evolved for individual protection against predators, and cohesion is maintained by a variety of mutually beneficial behaviors such as mutual grooming and tail-to-tail fly-swatting. More than half (51%) of allogrooming contacts occur at the preferred site in front of the shoulder blade and include the cranial aspect of the withers.61 This behavior (Fig. 5.8) has been reported in foals only 1 day old.43

Figure 5.8 Pair-bonded foals can often be seen mutually grooming. Of all horses, foals seem to find being scratched in hard-to-reach places most gratifying.

(Photograph courtesy of Francis Burton.)

Attachment between foals increases after the first 2 or 3 weeks of life, as the initial protectiveness of mares and the intensity of the foal–mare bond subsides.17 As confidence with an affiliate increases, so does the boldness of play and the strength of the bond with a given peer, as shown by the frequency of mutual grooming bouts. Mutual grooming characterizes the relationship in filly–filly and colt–filly partnerships. This is regularly interspersed with sustained episodes of playfighting if the partners are both colts.43 Since natal bands are largely female, the bonds formed between fillies at this stage can be lifelong, other partnerships being destined to dissolve at the time of juvenile dispersal (see below).17 Exceptions to these generalizations include the occasional formation of trios and the dispersal of juveniles in pairs.17 As testament to the robust memory horses boast, pair-bonds can withstand extended periods of separation (e.g. 6 months in the case of two New Forest pony mares43 and 5 years in the case of some Icelandic mares (Machteld van Dierendock, personal communication 2002).

Pair-bonded horses sometimes defend their affiliates from other band members (e.g. by intervening in mutual grooming that involves their preferred partner) as though they are possessive of the resource their affiliates represent.17 Similarly, mares sometimes attack stallions found courting their female affiliates.

Pair-bonded individuals conduct most of their daily activities together. Penetration of the personal space tends to cause avoidance more often than defense on the part of the subordinate horse. This means that while affiliative behaviors are active, affirmatory actions shown by pair-bonded horses, in many cases proximity reflects simple passive acceptance of conspecifics.

The social distance of horses is defined as the spatial limit companions will occupy, and beyond which they will either return to their affiliates or await their arrival.17 Social distance is shortest in mare–foal dyads but begins to increase after only 1 week of life.43 Depending on the scarcity of forage the social distance may extend to 50 m.31 However, it is rapidly reduced as a transient response to alarming stimuli. On the other hand, even affiliated horses can be too close for comfort when they encroach on one another’s personal space, usually within a radius of 1.5 m of the forequarters.24

Dispersal

The proximate causes of dispersal from the natal band vary with the youngster’s sex.62 The resident stallion plays a cardinal role in the dispersal of colts and only rarely allows a member that has been driven away to rejoin the natal band. If the stallion is not active in causing the departure of a surplus member, he may passively facilitate dispersal by simply allowing a member to drift away (i.e. in contrast to his usual band maintenance activities). Lead mares may also take a role in driving away colts that are beginning to make sexual overtures.

Because they reach puberty earlier, colts tend to leave before fillies. However, the age of departure from the natal band also varies with the experience of the departee and demographics (e.g. colts leave if they have no playmates) and social pressure in the natal band.17 Most of the juveniles that eventually leave the natal band, most will do so by the age of 4 years.43

When she matures sexually a filly will solicit attention from males. Since this is rarely effective with resident stallions in natal bands, the filly will consort with immature males in the natal band or males at the periphery of the group. Such behavior is rarely tolerated by the resident stallion, who precipitates dispersal by driving the couple away. Occasionally a stallion may drive away a female with whom he has failed to form a sociosexual bond.17 Sometimes the birth of a sibling is a catalyst for the departure of a filly.25 Once they have emigrated, females are usually quick to find established reproductive groups or form new ones. Most fillies leave the natal band during an estrus period63 between the ages of 1.5 and 2.5 years and rapidly find companions, usually males.64 Sometimes they join with colts with whom they have previously affiliated as members of the original natal band.65 Exiled males, on the other hand, may remain solitary for months or sometimes years.17

The home ranges of neighboring bands often overlap, and freshly dispersed youngsters regularly consort with adjacent groups since the value of their home range is enhanced by its familiarity compared with a completely novel area. Some juveniles leave their natal bands with a companion and consort with another group as a bonded pair or provide the nidus of a new group after encountering a small bachelor group or a similar mixed-sex juvenile band.17 Sometimes aged horses drift between bands.24 As their rank slips, agonistic encounters escalate until they become untenably frequent and cause dispersal.

Agonistic behavior

This term describes a whole suite of behaviors associated with aggression, protest, threat appeasement, defence and avoidance between conspecifics.66 From the everyday alerts and flight responses of stable groups to the drama of stallions in combat, these behaviors are of tremendous significance to humans working with horses. They provide the cardinal signs of behavioral conflict that establish thresholds of spatial infringement.67 Moreover, when ignored they form the basis of potentially lethal responses.

The frequency and character of agonistic displays depend on herd size, since triangular and more complicated relationships, such as reversals, are more likely to occur in large herds.49 Agonistic encounters within a band are often repeated in a series that eventually diminishes to leave the protagonists grazing alongside one another.15 As a social order becomes established, the intensity of repeated encounters declines and aggression can become ritualized.15 Non-agonistic interactions outnumber agonistic ones for all horses except adult males that have yet to secure a natal band, i.e. bachelors.7 The agonistic ethogram of the bachelor group has been described in detail and includes a total of 49 elemental behaviors, three complex behavioral sequences and five distinct vocalizations.15

Responses to potential danger

One advantage of social living is the increased surveillance afforded by the group members’ eyes and ears as they scan for potentially dangerous stimuli. In grazing animals it is important for all members of the group to remain alert since, with their heads to the ground, the bodies of other horses can block some of the views around them.

The chief alert response in horses is an elevated head and neck and intense orientation of the eyes (facilitating binocular vision) and ears. This tends to evoke similar responses in other members of the group, and false alarms can amount to a cost of social living. As a means of reducing this risk, natal bands tend to take their cue from the stallion and will soon calm down, despite having been originally alarmed, if the stallion remains calm.24

After alert responses come flight and investigation that is usually conducted by a high-ranking member of the group (Table 5.4). The advantage of investigation over constant fleeing is that it may allow the group to continue grazing in an otherwise ideal part of their home range. Species that lack this response pay a heavy price because they are obliged to spend a great deal of time and energy in flight. Horses tend to investigate potential threats by wheeling round and adopting a circuitous approach. Depending on the novelty of the stimulus, the horse may trot as it conducts a visual appraisal of the situation. This may have the advantage of preparing its muscles for a possible flight response and, as a symmetrical gait, does not impose any lateral bias to the horse’s locomotion should it need to take flight. The circuitous approach may be deployed in both directions before the horse gets any closer to the stimulus, thus increasing the information gained without a related increase in danger. Dilation of the nares and blowing of air accompany visual examination of the stimulus, and the noise made by this blowing often alerts band members that have not picked up on the visual indications of their peers’ concern. Snorting may have the added advantage of causing some approaching animals to flee or simply disperse either because they did not intend to prey or, if they did, because they appreciate that they have been detected.

Table 5.4 Features of the ethogram (as described for bachelor groups15) employed in investigation of a potential threat

| Response | Description |

|---|---|

Alert  |

Rigid stance with neck elevated and head oriented toward the object or animal of focus. The ears are held stiffly upright and forward and the nostrils may be slightly dilated. The whinny may accompany this response |

Approach  |

Forward movement at any gait or speed toward the potential threat via a straight or curving path. The head may be elevated and ears forward or the head may be lowered and the ears pinned back |

Arched neck threat  |

Neck tightly flexed with the muzzle drawn toward the chest. Especially characteristic of stallions, arched neck threats are observed during close aggressive encounters and ritualized interactions and may complement or coincide with other responses such as olfactory investigation, parallel prance, posturing, pawing and strike threat |

Avoidance/retreat  |

Movement that maintains or increases an individual’s distance from an approaching threat. The head is usually held low and the ears turned back. The retreat can be at any gait but typically occurs at the trot |

Balk  |

Abrupt halt or reversal of direction with movement of the head and neck in a rapid sweeping dorsolateral motion away from an apparent threat, while the hindlegs remain stationary. The forelegs may lift off the ground. Typically associated with an approach or lunge of another horse |

Olfactory investigation  |

As part of interaction between conspecifics, this investigation of the head and/or body is seen after horses have approached one another nose-to-nose. After mutually sniffing face to face, typically one horse works its way along the other’s body length, sniffing any or all of the following: neck, withers, flank, genitals, and tail or perineal region. During the investigation, it is common for one or both to squeal, snort, kick threat, strike threat or bite threat |

Often a horse has to get quite close to the threatening stimulus to sniff it thoroughly. For this reason it may make a series of false starts before getting close. While increasing the approaching horse’s confidence, these false approaches may invite a naïve predator to launch a premature attack. When approaching a conspecific, dominant horses may be accompanied by one or two affiliates to form assemblies.15 Solitary horses confronted with any potential threat tend to make more cautious approaches than when accompanied.

If the auditory or olfactory investigation confirms the presence of a potential predator the horse takes flight. Intriguingly humans evoke a swifter flight response by naïve, unhandled horses when they assume a quadrupedal stance.69 Similarly, two familiar humans who combine to form the shape of a quadruped will elicit flight. The putative role of human actions in roundpen work (see Ch. 13) solely as analogues of predatory responses should be considered conjecture in the light of this finding. Fundamentally, this view assumes that horses have a concept of predation,1 rather than the more parsimonious explanation that some stimuli are simply aversive. Possibly because it is the most economical (see Ch. 7), the trot is the gait adult horses tend to use for withdrawal from a threat, while the gallop is often employed by foals. Postural tonus increases with arousal and brings the horse into a state of readiness for flight and alerts conspecifics to the possible need for escape. This response is regularly accompanied by defecation and occasional pawing at the ground.

Aggression

As we have seen, aggression is generally associated with head threats and bites whereas defense involves responses by the hindquarters. Since horses are primarily in the company of affiliated band members, more demonstrations of (mild) aggression are exchanged between pair-bonded individuals than between other members of the group. Gestures used differ in their frequency depending on the sex and age of the horse making them, e.g. mares have been shown to make more kick threats than stallions and juveniles.69

The most common form of aggression among all horses is the head threat, which involves the extension of the aggressor’s head and neck towards another individual while flattening the ears against the head. Head threats are economical and can achieve results without the aggressive animal having to move away from the resource it is seeking to protect. If the mouth is open and biting motions are included but no contact is made with the recipient, the response is labeled a bite threat. Such a threat may or may not be used before an actual bite. Similar gestures are seen when horses respond to other annoyances such as flying insects and abdominal pain.17 Bites delivered to the hindquarters of conspecifics may be used to drive other horses forward, and bite threats have the same effect. This is most notable in the snaking gestures offered by stallions when herding and driving his band. Here lateral swinging of the lowered head and neck is accompanied by the ubiquitous pinning of the ears to repel band members. Another sort of threat a horse can give using its forequarter is the threat to strike which again is accompanied by ear-pinning but is characterized by movement of one or both forelimbs outward and forward in the direction of the recipient.8

If the object of a horse’s displeasure is closer to its hindquarters than its forequarters then kick threats and kicks are the more likely response (Fig. 5.9).17 The hindlegs can be especially effective in aggression, and threats to use them involve simply moving the hindquarters near another animal, or lifting, occasionally hopping and ultimately kicking with the hindlegs. As with other threats, the ears are laid back as a cardinal element of these responses and the more the ears are flattened the more serious is the threat (and with it the more likely will be the emergence of physical contact). Tail-swishing and squealing often accompany kick threats. Horses are remarkably accurate when they choose to strike with their hindlegs,70 and this is why kicks that do not engage on the protagonist are described as threats rather than misses. If threats given with the fore or hindquarters are ineffective, the aggressor may give chase (Fig. 5.10).

Figure 5.9 Two horses exchanging threats. Aggression between horses is accompanied by liberal signaling, i.e. threats that are used primarily to repel protagonists in a bid to avoid physical combat.

(Photograph courtesy of Francis Burton.)

Figure 5.10 Chasing by band members is costly in terms of energy so it occurs only when threats have not been heeded.

(Photograph courtesy of Francis Burton.)

Where there is a lack of deference, for example when two band members are virtually level in the hierarchy or when an interloping bachelor makes a bid to displace a resident stallion, fights typically ensue. Mares tend to engage in kicking fights whereas stallions are more likely to rear. The specific ritualized displays stallions offer in a bid to offset the need for combat are described in Chapters 6, 9 and 11.

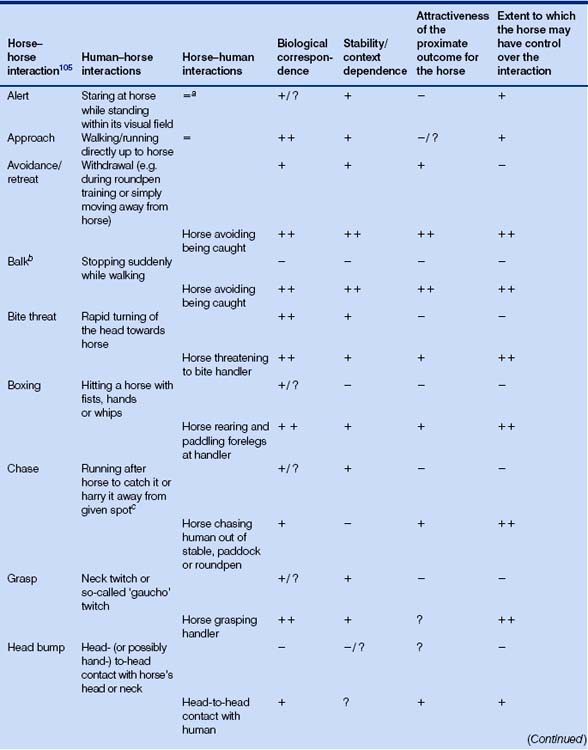

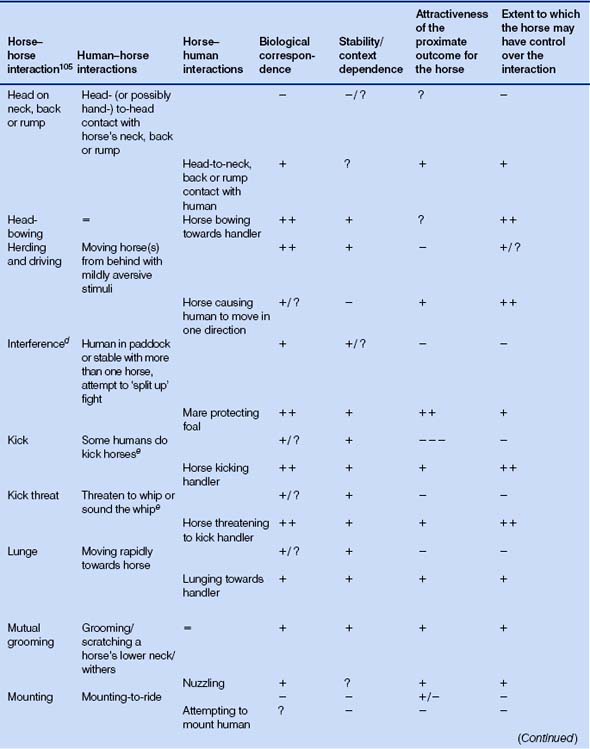

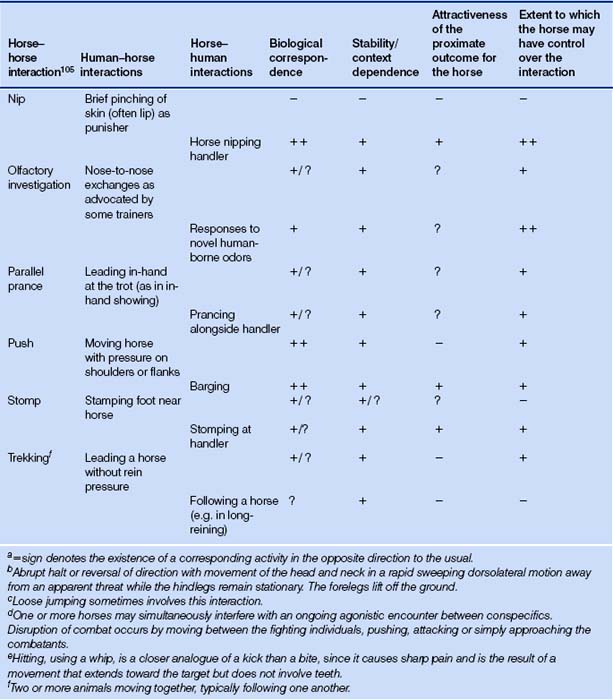

Posturing describes a suite of responses that are not ritualized but often seen together before combat.15 It includes generalized muscular stiffening of the limbs, olfactory investigation, stomping, prancing and head-bowing and arched neck threatening. If displays are ineffective in dispelling aggression between stallions, fights of tremendous intensity and violence may arise. These may include circling or rearing and striking. Biting is very common and serves to impair the balance or nerve of the combatant. If one of the protagonists is knocked to the ground his chances of defeat and serious injury are increased. Broken bones are a not uncommon result of fights between feral and, for that matter, domestic stallions. The repertoire of behaviors that arise in horse–horse interactions, human–horse interactions and horse–human interactions are summarized in Tables 5.5–5.7 and Box 5.1, along with an estimate of their biological correspondence and their dependence on context.

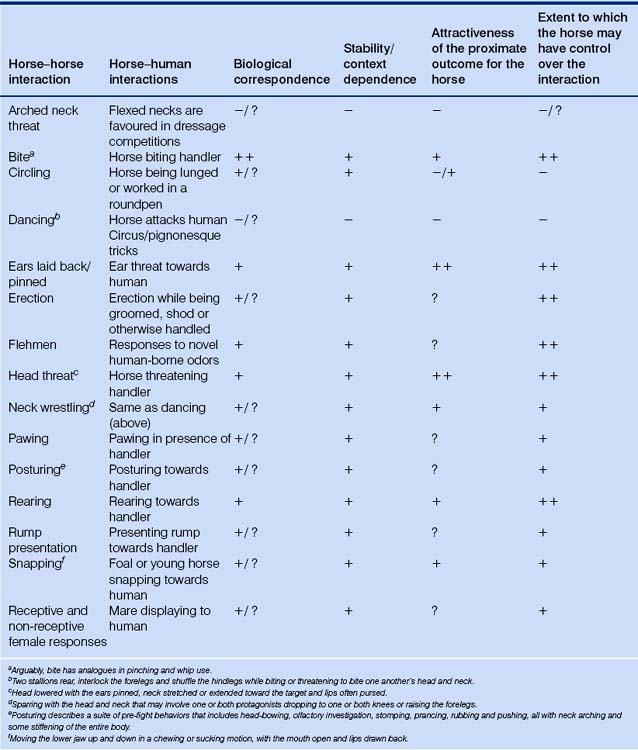

Table 5.5 Activities for which naturally occurring analogues exist in both directions: human–horse and horse–human1

Table 5.6 Activities for which a naturally occurring analogue exists in only one direction: horse–human1

Table 5.7 Activities for which no naturally occurring analogues exist (things horses never do to each other) (i.e. no biological correspondence)1

| Human–horse interaction | Attractiveness of outcome for horse | Extent of horse’s control |

|---|---|---|

| Picking feet up, hoof trimming and shoeing | + | + |

| Leading into trailer or box | +/− | +/− |

| Trailer loading without leading | +/− | + |

| Feeding by hand or from bucket | ++ | + |

| Invasive veterinary work (e.g. injecting and suturing) | − | − |

| Grooming inguinal, ventral and perineal regions | +/− | +/− |

| Pulling hairs from the mane and tail | − | +/− |

| Spraying against flies | +/− | − |

| Clipping | +/− | − |

| Branding | −− | − |

| Driving in close proximity to other horses (e.g. driving horses side-by-side demands tolerance of breached individual space) | +/− | +/− |

| Mounting-to-ride | +/− | +/−−− |

Other things we make or train horses to do: bow, hyperextension, capriole, jump over another horse, walk on hindlegs, tolerate predator on back, vaulting, towing, jumping, racing, driving, showing/parading, treadmill training, semen collection.

Box 5.1 Elements of the ethogram that do not appear in horse–human dyads (horse–horse activities, but not horse–human or human–horse)1

• Maternal licking (although sponging may equate)

• Suckling (although equivalent may appear as hand-stripping prior to bottle feeding)

• Blocking (defined in ethogram as foal stopping in front of and perpendicular to mare)

• Mutual insect control (although a human may swat flies away from horse, and may also be target of tail swishing from horses, these two activities rarely occur simultaneously, so it seems inappropriate to call it ‘mutual’).

Submission

Submission, in the form of deference and withdrawal, is the cement of equine social integrity but, perhaps because it involves signaling that is less obvious to human observers than that of aggression, it is often overlooked and its importance underestimated.15,58 It allows subordinate animals to avoid injury and is similarly helpful to dominant individuals since it can conserve energy and thus reduce the cost of holding a resource. The same principle applies for inter-band aggression, with fewer than 25% of interactions between bands of horses over resources such as water and winter grazing ending in physical contact.31,44

When in close proximity with their aggressors, submissive horses often simply have to turn their heads away from their protagonists to switch off the aggression. If this fails, then they must give ground. If the subordinate horse finds that it is unable to get out of the way of an aggressor to the fore, it may throw its head with a rapid swing and roll its eyes thus exposing their sclera. The presence of an ongoing threat from the rear will usually cause the horse to tuck its tail and drop its croup as it tries to shuffle out of the way.

Other signals of deference may be given when horses are at a greater distance from one another. Signs of submission in a colt transiently exiled from the band (as described by Roberts71) are said to include lowering his head to the ground, chewing, and licking his lips. That said, head-lowering or licking-and-chewing may be displacement responses. They are reported less in intra-specific encounters in roundpens than has been suggested by roundpen advocates.72 Their presence in free-ranging horses is the subject of ongoing discussion.58 These oral responses are slightly reminiscent of the snapping (tooth-clapping, champing, yawing, yamming) gestures illustrated in Figure 5.6 and the jaw movements of estrous mares, especially maidens43 and Standardbreds.73 An alternative explanation is that such oral movements are the behavioral manifestation of a physiological response. As part of the plasma response to the distress of being in the pen with inescapable aversive stimuli, circulating adrenaline will rise and lead to a relatively dry mouth. This prompts licking, which may elicit saliva secretion when the balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic discharges returns to normal (Francis Burton, personal communication 2002).

The true snapping display involves extending the head, often while splaying the ears laterally and drawing the corners of the mouth back. It is characteristic of horses 3 years of age and younger. The mouth is opened and closed but without any true biting, i.e. the teeth usually fail to meet. Usually performed while approaching the head of another horse at an angle, the snapping display exposes the incisors. A sucking sound may be made as the tongue is drawn against the roof of the mouth. Typically the head and neck are extended, with the ears relaxed and oriented back or laterally.

There is some debate surrounding the communication intended by animals performing these gestures, the frequency of which declines with age. For example, it has been suggested that this response has its origins in allogrooming74 and that the performer is trying to placate the recipient by demonstrating an intention to consolidate a putative pair-bond.24 Foals that have become displaced from their dams snap as they approach adults in the band and continue to do so until they have recognized their dams.43 It is interesting to note that stallions evoke more of this response than do other adults, and that male foals offer it more often than females.69 However, studies have shown that snapping fails to inhibit aggression and in some cases may even seem to precipitate it.8,27 This breadth of circumstance and consequence has led some to suggest that the interpretation of snapping may be context-dependent or alternatively a displacement response derived from a suckling behavior.27,58

Homing

Being less opportunistic than other species, the horse has evolved to be able to find its way back to its home range – for instance, after being pursued by a predator.75 In addition to the promise of finding its companions there, the value of the home range to its occupant reflects the comfort of knowing tracks and escape routes within the area as well as the topographical location of resources such as food, water and shelter. The role of olfaction (and the detection of familiar fecal material) in homing is likely to be significant.76 Horses have been recorded homing over distances of more than 15 km, and Icelandic horses are thought to be especially good at finding their way home.68

The tendency to increase speed when turned for home, shared by most horses, speaks of the motivation to remain in the home range. Bolting is far more often in the direction of home than in any other direction, and riders of horses not intended for high-speed performance do well to avoid reinforcing this tendency, e.g. by never racing in the direction of home. Horses are generally more wary of novel stimuli away from their home range, and this is one of the reasons why schooling at home is often easier than at a competition.

Social organization in donkeys

The social structure adopted by donkeys in any particular area is dependent on the availability of resources such as food and water. In bountiful environments, donkeys use a natal band system, similar to those of horses and ponies, with complex social order within the groups, in which rank is not a simple function of age, sex, aggression or weight (Jane French, personal communication). In arid and semi-arid regions, a loose social structure (also typical of African asses and Grevy’s zebras) exists with temporary groups of males, or females, or males and females predominating while some jacks become solitary. Small aggregations in this system rarely last more than a few days – membership is very fluid with mixing and splitting of groups occurring when animals congregate, e.g. at watering sources. There is no aggression between groups. Dominant jacks do not maintain a harem but dominate breeding activity within a large area, called a lek. The only permanent association is between a female and her foal, who travel together unassociated with others. This behavioral characteristic has a profound effect on the frequency of interactive behaviors, e.g. social play is rare in donkeys when compared with harem equids.77

The characteristic flexibility of hemionine social structure has practical implications for the management of grazing and the housing of donkeys with horses. Since donkeys are good mixers they are used as companion animals for performance horses. Being familiar and calm, they are valued as travel companions when particularly reactive sports horses leave their home yard for competitions and shows.

Although separation-related distress expressed with the drama of bolting back to the herd is less common in donkeys than in horses, some donkeys show some signs of extreme separation-related distress, such as braying, pacing and general pining, most notably when the individual is one of a bonded pair. These coping strategies do not become stereotypic. If one of a bonded pair dies, allowing the companion contact with the body for about 30 minutes seems sufficient to prevent the onset of overt separation-related distress.

Aggression toward people is very rare among donkeys (Jane French, personal communication 2001). In contrast, aggression toward other species, such as dogs and sheep, is more common in donkeys than aggression toward other equids. Indeed, along with llamas, donkeys are recognized as an effective guardian species.78

Applying the data from free-ranging horses to domestic contexts

When considering the effect of domestication on the social behavior of the horse, it is appropriate to compare the social structure of domestic groups with Przewalski horses and those that have had an opportunity to revert to type. The organization of social structure in wild, feral and domestic horses is similar enough to suggest that domestication has not had an effect on this facet of horse behavior. Perhaps because of artificial selection of passivity in E. caballus over the past 6000 years, E. przewalskii in captive environments were said to have a higher level of aggression than domesticated and feral horses.7 That said, it is worth noting that reintroduced E. przewalskii stallions do not show the high aggression recorded in confined populations. Furthermore, we should be cautious about making inferences about behavior of male E. przewalskii, because the extant population has only one Y chromosome since a single-stallion cohort was originally salvaged from the wild. So, presumed aggressiveness may not be a case of a characteristic of the species, but an individual variation on that chromosome (Machteld van Dierendock, personal communication 2002).

Horses naturally defend a space around them, and this accounts for the reluctance of many horses to stand close to one another when being ridden. Notwithstanding the need to maintain such a distance between horses, there are excellent reasons for riding naïve horses in the company of calmer, more experienced animals. Just as free-ranging horses after being alarmed soon calm down if the stallion remains calm,24 so do domestic horses take their cues from companions. It is advisable to capitalize on this tendency as often as possible when introducing naïve horses to novel stimuli. It is likely that, in the process of domestication, while we have found innate reactivity desirable in racing breeds, we have selected some breeds to be less reactive than their wild forebears. This is especially so for draft work that requires animals to be docile. Cold-blooded types are therefore generally preferred as exemplars and propagators of desirable behavior in potentially fearful situations such as heavy traffic.70

Since it is natural for horses to develop bonds and social order based on affiliations and hierarchies, managers and owners must understand that, once relationships have formed, the introduction of new horses increases the risk of injury and stress in the group. Youngsters receive the largest number of attacks in any group of horses as they are naïve and may be less responsive to threats. Just as horses in free-ranging groups tend to bond with conspecifics of similar age, so when establishing long-term groups it is appropriate to provide companions of similar ages and sufficient space for bonded pairs in a paddock to avoid one another. It has been suggested that the restrictions associated with human management may precipitate higher rates of aggression than would be seen in the free-ranging state.5,8 This should be borne in mind when horse-holding facilities are designed, e.g. paddocks should have rounded corners to prevent subordinate animals becoming trapped and kicked by dominant ‘bullies’.70 Structures in paddocks that provide a visual screening or baffling effect may be used for sanctuary by subordinate field-mates.

Since most aggression occurs near resources it is best to place water, feeding stations and even gates away from corners. The extent to which an individual can monopolize a resource can be limited by providing one more portion of that resource than there are horses in the enclosure. To avoid low-ranking individuals failing completely to access concentrates, it is worth providing them with feeding havens or removing them from the group for supplementary feeding. Even pair-bonded affiliates may maintain a personal space of 1.5 m when feeding, and so this should be used as the approximate minimum distance between individual feeding bays. Wire partitions along a feeding trough have been shown to reduce aggression by allowing subordinate horses to eat alongside more assertive individuals.79

Horses adapt poorly to the constant introduction of newcomers to a social group. Indeed, equine physiologists have used social instability to induce chronic stress as indicated by elevated free plasma cortisol concentrations (i.e. a reduction in corticosteroid-binding globulin).80 It can take 3 weeks for a new social order to be established.81

Fighting can lead to severe injuries especially when animals are crowded or continuously grouped or regrouped.15 Where there is a continuous flux in the complexion of a domestic group such as on a livery yard, placing mares and geldings in separate groups is thought to help reduce agonistic encounters that are reproductive in origin. The adoption of single-sex groups provides an analogue of the social dynamics that prevail in natal bands without a stallion (in which mare–mare bonds are successful) and bachelor groups that offer a model for male-only groupings. Providing an even number of horses in all groups may facilitate pair-bonding and, if the space is available, large groups seem to be associated with less aggression than small groups, perhaps because the increased choice of preferred partners reduces the need to defend key field-mates.

In some domestic contexts mixed groups can work well, but they are more often avoided because of over-bonding between individuals of the opposite sex. Most commonly, this manifests when geldings become difficult to ride away from mares with which they have bonded. Such animals often demonstrate signs of considerable anxiety, and in their hurried return to the group they show little consideration for their own safety, let alone that of their riders. Sometimes a gelding may entirely monopolize one mare in a group to the extent that she is prevented from socializing with any other horses. Equally, one gelding may harass another for the monopoly of a given mare.

Before placing new horses in a group, it is preferable to introduce horses to one another individually so that they have the opportunity to form pair bonds. The first meeting of two strangers can be facilitated if both are sufficiently hungry to be distracted by food sources placed a safe distance apart. To facilitate the establishment of social hierarchies in very small groups, horses of disparate predicted rank (e.g. old and young horses) can be mixed. Conversely, placing horses of similar ages in the same paddock has the potential to extend the period of flux (Fig. 5.11) during which peers challenge each other repeatedly until a hierarchy emerges. It is therefore not the preferred blend for transient groupings.

Figure 5.11 Horses that have very recently been introduced to one another posture and jostle to form a hierarchy.

(Reproduced by permission of the University of Bristol, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science.)

Allowing horses to meet for the first time with a fence between them has its merits but only if the barrier is safe and solid. Injuries, especially to the legs, should be expected if the fence is of wire or barbed wire. If there is no choice but to mix a new horse directly with an established group, it is best to first turn out the newcomer alone so that it can explore the paddock before it has to cope with the intensity of the whole group at once with their ‘home ground advantage’. With particularly reactive animals that are likely to run rather than graze when turned out, it is advisable to walk them around the fenceline before release since this may reduce the chances of them running into the fence. This is most likely to work if other horses that may distract new arrivals are out of sight.

The overall effect of isolation of mares from an established group with or without a companion for short periods has been described as minimal.82 Its behavioral effects include increased whinnying, urination and rolling.82 In contrast, the effects of long-term isolation on youngsters are profound. The complete isolation of foals and juveniles is particularly inadvisable since it can lead to mal-imprinting in foals83 and compromise social skills in juveniles.70 Animals that have undergone such isolation as youngsters regularly offer undesirable social behaviors upon being introduced to other horses.14 The same animals can learn to be assertive with humans, and this seems to have the capacity to foster aggression. By way of an example, young horses that have been inadvertently reinforced for pushing humans bearing supplementary feed, can ultimately defend the resource with frank aggression.70 Providing foals with conspecific peers is the best way to channel play-fighting in an appropriate direction and reduce the extent to which dangerous coltish responses such as rearing are directed towards humans. As the colts mature, fights become less playful when estrous mares are detected, and separation of males is advisable. This management decision should not mean that colts have to be isolated completely, as this can result in undesirable and maladaptive responses such as self-mutilation. Two-year-old colts have been shown to be sensitive to social deprivation in that stabling in isolation has long-term effects, lasting 6 weeks at least, on their social behavior.50 Stallions can be successfully pastured together if the paddock is spacious and several watering holes are available.15

The companionship of an older horse can help to teach youngsters social decorum (so-called ‘manners’). Meanwhile providing colts intended for breeding with a mature female companion may even help them learn mounting techniques.

Wherever possible, horses should be kept in social groups with a variety of age and sex classes. The horse responds poorly to isolation (Fig. 5.12) and is likely to show physiological and behavioral distress responses including stereotypies if deprived of contact with conspecifics.84 Horses without conspecific company have been shown to spend 10% less time eating and are three times more active than those that could make auditory, visual and tactile contact with other horses.85 There is also evidence of physiological stress reactions with increasing time spent confined in stalls and in isolation.86 Affiliations cannot be imposed on horses by simply housing them beside one another. This is borne out by comparisons of 2-year-old colts that had been group-reared and single reared for 9 months.60 Once released together, group-reared colts frequently had a former group mate as their nearest neighbor, whereas singly reared colts did not associate more with their former neighbors with whom they had limited physical contact via bars between stalls.60 Instead of guessing which horses will enjoy being neighbors, stable managers should take care to stable beside one another horses that have demonstrated some affiliation in the paddock. This may serve to reduce the distressing effects of confinement. There is evidence that mirrors can provide some of the stimuli that isolated horses need (Fig. 5.13).70 Horses do not appear to recognize the mirror images as their own, since they will sometimes show transient aggression towards them.70 For this reason, feed should be provided at a safe distance from the mirror, especially when the mirror has only recently been introduced.

Figure 5.13 When given mirrors, isolated horses often stand beside their own image. Mirrors used in this way should have rubber backing that prevents dispersal of shards should any damage occur.

(Reproduced by permission of the University of Bristol, Department of Clinical Veterinary Science.)

Housing horses together in the long term allows stress reduction activities (such as mutual grooming) to take place.67 Furthermore it is even possible for managed herds to be more stable and therefore involve less risk of injury than free-ranging groups, since most changes in the social hierarchy are due to changes in the younger age classes.69,87

Although housing horses together is better than isolating them, care must be taken to avoid unwelcome analogues of herd responses. Social facilitation can cause hysteria to spread through a group of horses, and this is why stabling should be designed to facilitate visual and auditory contact between close neighbors but not between large numbers of horses.

Homing tendencies can be put to good use as in the case of most racecourses that have the stabling beyond the finishing line (being the site of some food and company, the stables are likely to represent the horses’ temporary home range). Similarly desirable responses can be reinforced when providing horses with access to their band or affiliates, e.g. when jumping novice horses it is best to ride them over obstacles towards rather than away from other horses. Social bonds can sometimes be used to riders’ advantage. For example, one horse can help to lead another through water (Fig. 5.14).

Social behavior problems

Mal-imprinting and over-bonding

Hand-reared foals often show evidence of mal-imprinting, such as when they prefer human company to that of other horses.83,88 The first suspicion that a foal is adopting an individual human caregiver as a surrogate mother may be when it offers the snapping response to humans.88 This rule of thumb should be used with caution since naturally reared foals occasionally offer the same greeting to humans. Mal-imprinting is less likely if the foal is housed in visual contact with its own kind (any non-aggressive conspecific will serve the purpose) during the sensitive period that has been estimated to end at approximately 48 hours of age.17 While this so-called window period remains ill-defined, it is worth noting that the vocalization rate of foals experimentally separated from their dams peaks just before 4 weeks of age. This implies that their needs are maximal during this time, and therefore the possibility of bonding to a surrogate caregiver can also be considerable at this time. So there is a strong argument for fostering such orphans or, failing that, rearing them within a group of conspecifics.