Screening the Shoulder and Upper Extremity

The therapist is well aware that many primary neuromuscular and musculoskeletal conditions in the neck, cervical spine, axilla, thorax, thoracic spine, and chest wall can refer pain to the shoulder and arm. For this reason, the physical therapist’s examination usually includes assessment above and below the involved joint for referred musculoskeletal pain (Case Example 18-1).

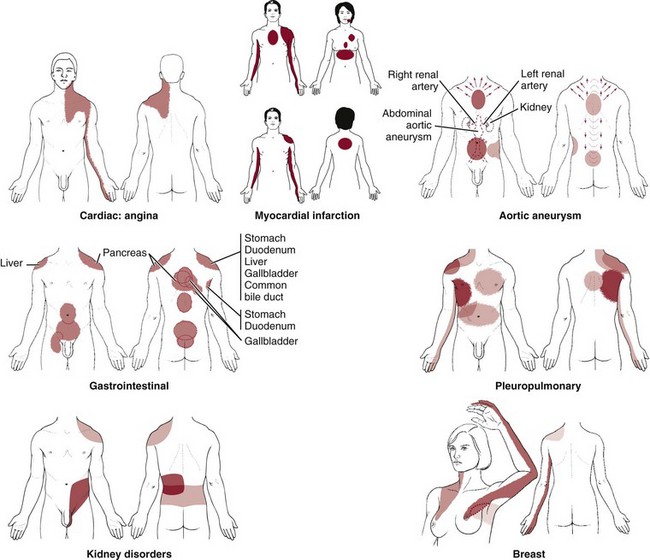

In this chapter, we explore systemic and viscerogenic causes of shoulder and arm pain and take a look at each system that can refer pain or symptoms to the shoulder. This will include vascular, pulmonary, renal, gastrointestinal (GI), and gynecologic causes of shoulder and upper extremity pain and dysfunction. Primary or metastatic cancer as an underlying cause of shoulder pain also is included. The therapist must know how and what to look for to screen for cancer.

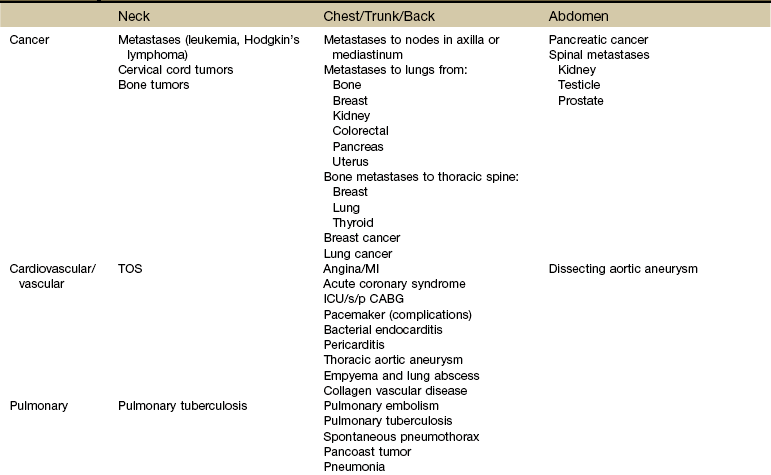

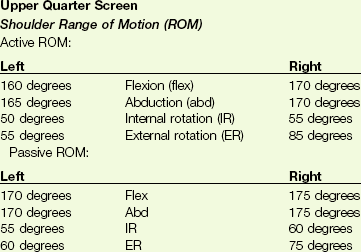

Systemic diseases and medical conditions affecting the neck, breast, and any organs in the chest or abdomen can present clinically as shoulder pain (Table 18-1).1 Peptic ulcers, heart disease, ectopic pregnancy, and myocardial ischemia are only a few examples of systemic diseases that can cause shoulder pain and movement dysfunction. Each disorder listed can present clinically as a shoulder problem before ever demonstrating systemic signs and symptoms.

TABLE 18-1

Systemic and Medical Conditions as Causes of Shoulder and Upper Extremity Symptoms

TOS, Thoracic outlet syndrome; MI, myocardial infarction; ICU/s/p CABG, intensive care unit status post coronary artery bypass graft.

Using the Screening Model to Evaluate Shoulder and Upper Extremity

As you look over the various potential systemic causes of shoulder symptomatology listed in Table 18-1, think about the most common risk factors and red flag histories you might see with each of these conditions. For example, a history of any kind of cancer is always a red flag. Breast and lung cancer are the two most common types of cancer to metastasize to the shoulder.

Heart disease can cause shoulder pain, but it usually occurs in an age specific population.2,3 Anyone over 50 years old, postmenopausal women, and anyone with a positive first generation family history is at increased risk for symptomatic heart disease. Younger individuals may be more likely to demonstrate atypical symptoms such as shoulder pain without chest pain.4

Alternately, although atherosclerosis has been demonstrated in the blood vessels of children, teens, and young adults, they are rarely symptomatic unless some other heart anomaly is present.5,6

Hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia are other red flag histories associated with cardiac-related shoulder pain. Of course, a history of angina,7 heart attack, angiography, stent or pacemaker placement, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), or other cardiac procedure is also a yellow (caution) flag to alert the therapist of the potential need for further screening.

Knowledge of risk factors associated with pathologic conditions, illnesses, and diseases helps the therapist navigate the screening process. For example, pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is a possible cause of shoulder pain.8-10 Who is most likely to develop TB? Risk factors include:

• Immunocompromised individuals (e.g., transplant recipients, long-term users of immunosuppressants, anyone treated for long-term rheumatoid arthritis [RA], anyone treated with chemotherapy for cancer)

• Immigrants from areas where TB is endemic

• Malnourished (e.g., eating disorders, alcoholism, drug users, cachexia)

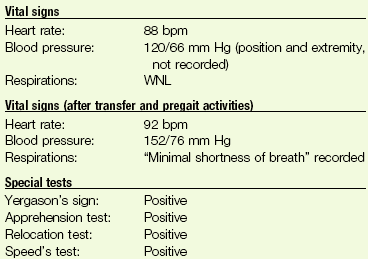

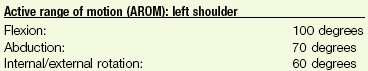

In a case like tuberculosis, there will usually be other associated signs and symptoms such as fever, sweats, and cough. When completing a screening examination for a client with shoulder pain of unknown origin or an unusual clinical presentation, the therapist might look at vital signs, auscultate the client, and see what effect increased respiratory movements have on shoulder symptoms (Case Example 18-2).

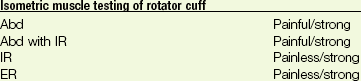

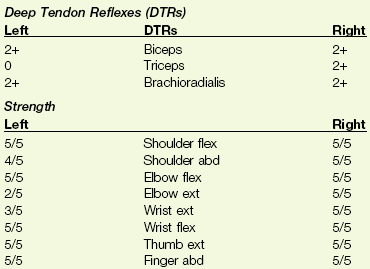

Clinical Presentation

Differential diagnosis of shoulder pain is sometimes especially difficult because any pain that is felt in the shoulder often affects the joint as though the pain were originating in the joint.3 Shoulder pain with any of the components listed in this chapter should be approached as a manifestation of systemic visceral illness, even if shoulder movements exacerbate the pain or if there are objective findings at the shoulder.

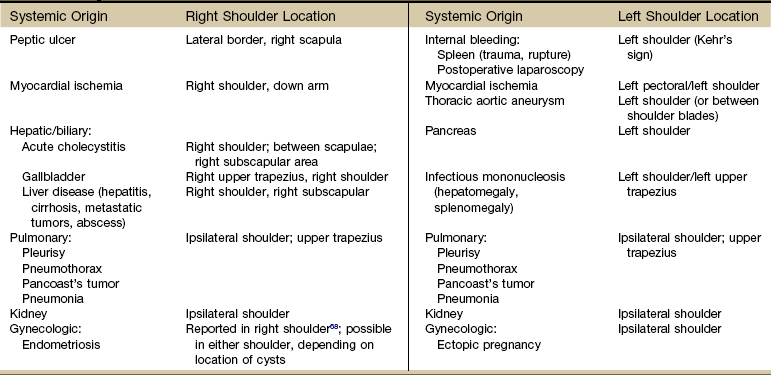

Many visceral diseases present as unilateral shoulder pain (Table 18-2). Esophageal, pericardial (or other myocardial diseases), aortic dissection, and diaphragmatic irritation from thoracic or abdominal diseases (e.g., upper GI, renal, hepatic/biliary) all can appear as unilateral pain.

Adhesive capsulitis, a condition in which both active and passive glenohumeral motions are restricted, can be associated with diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism,11,12 ischemic heart disease, infection, and lung diseases (tuberculosis, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, Pancoast’s tumors) (Case Example 18-3).9,10,13-15

Shoulder pain (unilateral or bilateral) progressing to adhesive capsulitis can occur 6 to 9 months after CABG. Similarly, anyone immobile in the intensive care unit (ICU) or coronary care unit (CCU) can experience loss of shoulder motion resulting in adhesive capsulitis (Case Example 18-4). Clients with pacemakers who have complications and revisions that result in prolonged shoulder immobilization can also develop complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and/or adhesive capsulitis.16

The Shoulder Is Unique

It has been stressed throughout this text that the basic clues and approach to screening are similar, if not the same, from system to system and anatomic part to anatomic part.

So, for example, much of what was said about screening the neck and back (Chapter 14) applied to the sacrum, sacroiliac (SI), and pelvis (Chapter 15); buttock, hip, and groin (Chapter 16); and chest, breast, and rib (Chapter 17). Presenting the shoulder last in this text is by design. These principles do apply to the shoulder but beyond that:

It is not uncommon for the older adult to attribute “overdoing” it to the appearance of physical pain or neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) dysfunction. Any adult over age 65 presenting with shoulder pain and/or dysfunction must be screened for systemic or viscerogenic origin of symptoms, even when there is a known (or attributed) cause or injury.

In Chapter 2, it was stressed that clients who present with no known cause or insidious onset must be screened along with anyone who has a known or assumed cause of symptoms. Whether the client presents with an unknown etiology of injury or impairment or with an assigned cause, always ask yourself these questions:

The client may wrongly attribute onset of symptoms to an activity. The alert therapist may recognize a true causative factor.

Shoulder Pain Patterns

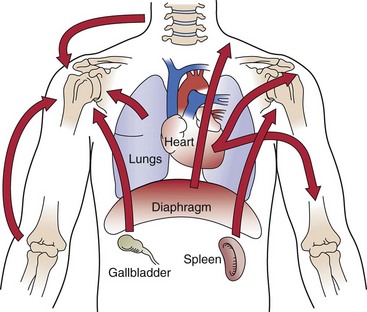

In Chapter 3, we presented three possible mechanisms for referred pain patterns from the viscera to the soma (embryologic development, multisegmental innervations, and direct pressure on the diaphragm). Multisegmental innervations (see Fig. 3-3) and direct pressure on the diaphragm (see Figs. 3-4 and 3-5) are two key mechanisms for referred shoulder pain.

Multisegmental Innervations: Because the shoulder is innervated by the same spinal nerves that innervate the diaphragm (C3 to C5), any messages to the spinal cord from the diaphragm can result in referred shoulder pain. The nervous system can only tell what nerves delivered the message. It does not have any way to tell if the message sent along via spinal nerves C3 to C5 came from the shoulder or the diaphragm. So it takes a guess and sends a message back to one or the other.

This means that any organ in contact with the diaphragm that gets obstructed, inflamed, or infected can refer pain to the shoulder by putting pressure on the diaphragm, stimulating afferent nerve signals, and telling the nervous system that there is a problem.

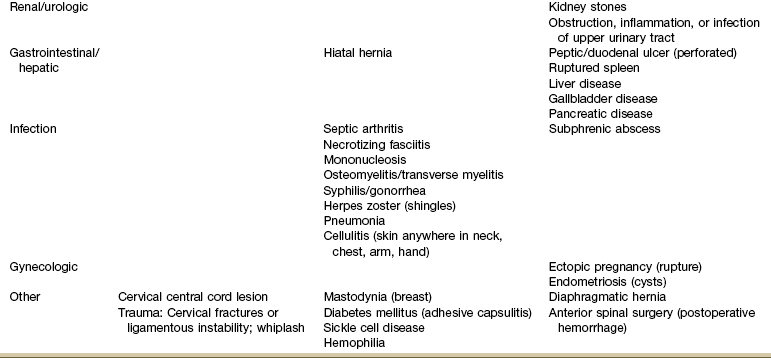

Diaphragmatic Irritation: Irritation of the peritoneal (outside) or pleural (inside) surface of the central diaphragm refers sharp pain to the ipsilateral upper trapezius, neck and/or supraclavicular fossa (Fig. 18-1). Shoulder pain from diaphragmatic irritation usually does not cause anterior shoulder pain. Pain is confined to the suprascapular, upper trapezius, and posterior portions of the shoulder.

Fig. 18-1 Irritation of the peritoneal (outside) or pleural (inside) surface of the central area of the diaphragm can refer sharp pain to the upper trapezius muscle, neck, and supraclavicular fossa. The pain pattern is ipsilateral to the area of irritation. Irritation to the peripheral portion of the diaphragm can refer sharp pain to the ipsilateral costal margins and lumbar region (not shown).

If the irritation crosses the midline of the diaphragm, then it is possible to have bilateral shoulder pain. This does not happen very often and is most common with cardiac ischemia or pulmonary pathology affecting the lower lobes of the lungs on both sides. Irritation of the peripheral portion of the diaphragm is more likely to refer pain to the costal margins and lumbar region on the same side.

As you review Fig. 3-4, note how the heart, spleen, kidneys, pancreas (both the body and the tail), and the lungs can put pressure on the diaphragm. This illustration is key to remembering which shoulder can be involved based on organ pathology. For example, the spleen is on the left side of the body so pain from spleen rupture or injury is referred to the left shoulder (called Kehr’s sign) (Case Example 18-5).18

Either shoulder can be involved with renal colic or distention of the renal cap from any kidney disorder, but it is usually an ipsilateral referred pain pattern depending on which kidney is impaired (see Fig. 10-7; again, via pressure on the diaphragm). Bilateral shoulder pain from renal disease would only occur if and when both kidneys are compromised at the same time.

Look for history of a recent surgery as part of the past medical history and the presence of accompanying urologic symptoms.

The body of the pancreas lies along the midline of the diaphragm. When the body of the pancreas is enlarged, inflamed, obstructed, or otherwise impinging on the diaphragm, back pain is a possible referred pain pattern. Pain felt in the left shoulder may result from activation of pain fibers in the left diaphragm by an adjacent inflammatory process in the tail of the pancreas.

Postlaparoscopic shoulder pain (PLSP) frequently occurs after various laparoscopic surgical procedures. During the procedure air is introduced into the peritoneum to expand the area and move the abdominal contents out of the way. The mechanism of PLSP is commonly assumed to be overstretching of the diaphragmatic muscle fibers due to the pressure of a pneumoperitoneum (residual carbon dioxide [CO2] gas after surgery).19 Pressure from distention causes phrenic nerve–mediated referred pain to the shoulder.20

Keep in mind that shoulder pain also can occur from diaphragmatic dysfunction. For anyone with shoulder pain of an unknown origin or which does not improve with intervention, palpate the diaphragm and assess its excursion and timing during respiration. Reproduction of shoulder symptoms with direct palpation of the diaphragm and the presence of altered diaphragmatic movement with breathing offer clues to the possibility of diaphragmatic (muscular) involvement.

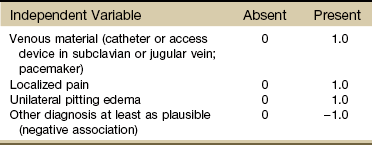

Fig. 18-2 reminds us that shoulder pain can be referred from the neck, back, chest, abdomen, and elbow. During orthopedic assessment, the therapist always checks “above and below” the impaired level for a possible source of referred pain. With this guideline in mind, we know to look for potential musculoskeletal or neuromuscular causes from the cervical and thoracic spine21 and elbow.

Associated Signs and Symptoms

One of the most basic clues in screening for a viscerogenic or systemic cause of shoulder pain is to look for shoulder pain accompanied by any of the following features:

• Recent history of laparoscopic procedure (risk factor)18,22,23

• Coincident diaphoresis (cardiac)

• Associated GI signs and symptoms

• Exacerbation by exertion unrelated to shoulder movement (cardiac)

Shoulder pain with any of these present should be approached as a manifestation of systemic visceral illness. This is true even if the pain is exacerbated by shoulder movement or if there are objective findings at the shoulder.24

Using the past medical history and assessing for the presence of associated signs and symptoms will alert the therapist to any red flags suggesting a systemic origin of shoulder symptoms. For example, a ruptured ectopic pregnancy with abdominal hemorrhage can produce left shoulder pain (with or without chest pain) in a woman of childbearing age.25-27 The woman is sexually active, and there is usually a history of missed menses or recent unexplained/unexpected bleeding.

The client may not recognize the connection between painful urination and shoulder pain or the link between gallbladder removal by laparoscopy and subsequent shoulder pain. It is the therapist’s responsibility to assess musculoskeletal symptoms, making a diagnosis that includes ruling out the possibility of systemic disease.

Review of Systems

Associated signs and symptoms feature heavily in the Review of Systems as we step back and look to see if a cluster of any particular organ-dependent signs and symptoms is present. Based on the results of this review, we formulate our final screening questions, tests, and measures. Always remember to end each client interview with the following (or similar) question:

Screening for Pulmonary Causes of Shoulder Pain

Extensive disease may occur in the periphery of the lung without pain until the process extends to the parietal pleura. Pleural irritation then results in sharp, localized pain that is aggravated by any respiratory movement.

Clients usually note that the pain is alleviated by lying on the affected side, which diminishes the movement of that side of the chest (called “autosplinting”) whereas shoulder pain of musculoskeletal origin is usually aggravated by lying on the symptomatic shoulder.

Shoulder symptoms made worse by recumbence are a yellow flag for pulmonary involvement. Lying down increases the venous return from the lower extremities. A compromised cardiopulmonary system may not be able to accommodate the increase in fluid volume. Referred shoulder pain from the taxed and overworked pulmonary system may result.

At the same time, recumbency or the supine position causes a slight shift of the abdominal contents in the cephalic direction. This shift may put pressure on the diaphragm, which in turn presses up against the lower lung lobes. The combination of increased venous return and diaphragmatic pressure may be enough to reproduce the musculoskeletal symptoms.

Pneumonia in the older adult may appear as shoulder pain when the affected lung presses on the diaphragm; usually there are accompanying pulmonary symptoms, but in older adults, confusion (or increased confusion) may be the only other associated sign.

The therapist should look for the presence of a pleuritic component such as a persistent or productive cough and/or chest pain. Look for tachypnea, dyspnea, wheezing, hyperventilation, or other noticeable changes. Chest auscultation is a valuable tool when screening for pulmonary involvement.

Screening for Cardiovascular Causes of Shoulder Pain

Pain of cardiac and diaphragmatic origin is often experienced in the shoulder because the heart and diaphragm are supplied by the C5 to C6 spinal segment, and the visceral pain is referred to the corresponding somatic area (see Fig. 3-3).

Exacerbation of the shoulder symptoms from a cardiac cause occurs when the client increases activity that does not necessarily involve the arm or shoulder. For example, walking up stairs or riding a stationary bicycle can bring on cardiac-induced shoulder pain.

In cases like this, the therapist should ask about the presence of nausea, unexplained sweating, jaw pain or toothache, back pain, or chest discomfort or pressure. For the client with known heart disease, ask about the effect of taking nitroglycerin (men) or antacids/acid-relieving drugs (women) on their shoulder symptoms.

Vital sign and physical assessment including chest auscultation are important screening tools. See Chapter 4 for details.

Angina or Myocardial Infarction

Angina and/or myocardial infarction (MI) can appear as arm and shoulder pain that can be misdiagnosed as arthritis or other musculoskeletal pathologic conditions (see complete discussion in Chapter 6 and see Figs. 6-8 and 6-9).

Look for shoulder pain that starts 3 to 5 minutes after the start of activity, including shoulder pain with isolated lower extremity motion (e.g., shoulder pain starts after the client climbs a flight of stairs or rides a stationary bicycle). If the client has known angina and takes nitroglycerin, ask about the influence of the nitroglycerin on shoulder pain.

Shoulder pain associated with MI is unaffected by position, breathing, or movement. Because of the well-known association between shoulder pain and angina, cardiac-related shoulder pain may be medically diagnosed without ruling out other causes, such as adhesive capsulitis or supraspinatus tendinitis, when, in fact, the client may have both a cardiac and a musculoskeletal problem (Case Example 18-6).

Using a review of symptoms approach and a specific musculoskeletal shoulder examination, the physical therapist can screen to differentiate between a medical pathologic condition and mechanical dysfunction28 (Case Example 18-7).

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS; types I and II) characterized by chronic extremity pain following trauma is sometimes still referred to by the outdated term shoulder-hand syndrome (see Case Example 1-5). CRPS-I was formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD). CRPS-II was referred to as causalgia.

CRPS was first recognized in the 1800s as causalgia or burning pain in wounded soldiers. Similar presentations after lesser injuries were labeled as RSD.29 Shoulder-hand syndrome was a condition that occurred after an MI (heart attack), usually after prolonged bedrest. This condition (as it was known then) has been significantly reduced in incidence by more up-to-date and aggressive cardiac rehabilitation programs.

Today CRPS-I, primarily affecting the limbs, develops after bone fracture or other injury (even slight or minor trauma, venipuncture, or an insect bite) or surgery to the upper extremity (including shoulder arthroplasty) or lower extremity. Type I is not associated with a nerve lesion, whereas Type II develops after trauma with a nerve lesion.30,31

CRPS-I is still associated with cerebrovascular accident (CVA), heart attack, or diseases of the thoracic or abdominal viscera that can refer pain to the shoulder and arm, which is why it is included here instead of in a section on neurologic conditions. CRPS secondary to deep venous thrombosis (DVT) has also been reported. Individuals developing limb pain and edema after DVT will need further diagnostic investigation to differentiate the cause of symptoms.32

Shoulder, arm, or hand pain and ischemia (usually acute) associated with CRPS that develop without a history of trauma may be attributed to cardiac embolism.33 Structural cardiac causes of upper limb ischemia include a wide variety of conditions (e.g., atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, prosthetic valve, endocarditis, atrial septal defects, aortic dissection).34

This syndrome occurs with equal frequency in either or both shoulders and except when caused by coronary occlusion, is most common in women. The shoulder is generally involved first, but the painful hand may precede the painful shoulder.

When this condition occurs after MI, the shoulder initially may demonstrate pericapsulitis. Tenderness around the shoulder is diffuse and not localized to a specific tendon or bursal area. The duration of the initial shoulder stage before the hand component begins is extremely variable. The shoulder may be “stiff” for several months before the hand becomes involved or both may become stiff simultaneously. Other accompanying signs and symptoms are usually present such as edema, skin (trophic) changes, and vasomotor (temperature, hidrosis) changes.

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Compression of the neurovascular bundle consisting of the brachial plexus and subclavian artery and vein (see Fig. 17-10) can cause a variety of symptoms affecting the arm, hand, shoulder girdle, neck, and chest (Case Example 18-8). Risk factors and clinical presentation are discussed more completely in Chapter 17.

Bacterial Endocarditis

The most common musculoskeletal symptom in clients with bacterial endocarditis is arthralgia, generally in the proximal joints. The shoulder is affected most often, followed (in declining incidence) by the knee, hip, wrist, ankle, metatarsophalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints, and by acromioclavicular involvement.

Most clients with endocarditis-related arthralgias have only one or two painful joints, although some may have pain in several joints. Painful symptoms begin suddenly in one or two joints, accompanied by warmth, tenderness, and redness. One helpful clue: As a rule, morning stiffness is not as prevalent in clients with endocarditis as in those with rheumatoid arthritis or polymyalgia rheumatica.

Pericarditis

The inflammatory process accompanying pericarditis may result in an accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac, preventing the heart from expanding fully. The subsequent chest pain of pericarditis (see Fig. 6-10) closely mimics that of a MI because it is substernal, is associated with cough, and may radiate to the shoulder.35 It can be differentiated from MI by the pattern of relieving and aggravating factors.

For example, pericarditis pain is sharp and relieved by leaning over when seated. If there is irritation of the diaphragm, it can cause shoulder pain. The pain of MI is unaffected by position, breathing, or movement, whereas the chest and shoulder pain associated with pericarditis may be relieved by kneeling with hands on the floor, leaning forward, or sitting upright. Pericardial pain is often made worse by deep breathing, swallowing, or belching.

Aortic Aneurysm

Aortic aneurysm appears as sudden, severe chest pain with a tearing sensation (see Fig. 6-11), and the pain may extend to the neck, shoulders, lower back, or abdomen but rarely to the joints and arms, which distinguishes it from MI.

Isolated shoulder pain is not associated with aortic aneurysm; shoulder pain (usually left shoulder) occurs when the primary pain pattern radiates up and over the trapezius and upper arm(s) (see Fig. 6-11).36 The client may report a bounding or throbbing pulse (heartbeat) in the abdomen. Risk factors and other associated signs and symptoms help distinguish this condition.

Deep Venous Thrombosis of the Upper Extremity

DVT of the upper extremity is not as common as in the lower extremity but incidence may be on the rise due to the increasing use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC lines) or central venous catheters (CVC).37,38 Thrombosis affects the subclavian vein, axillary vein, or both most often with less common sites being the internal jugular and brachial veins.39

CVCs are frequently used in people with hematologic/oncologic disorders in order to administer drugs, stem cell infusions, blood products, parenteral alimentation, and blood sampling. Other risk factors include blood clotting disorders,40 clavicle fracture,41 insertion of pacemaker wires, and arthroscopy of the shoulder or reconstructive shoulder arthroplasty.42,43 Thrombosis is the second-leading cause of death in cancer patients, and cancer is a major risk factor of venous thromboembolism (VTE), due to activation of coagulation, use of long-term CVC, and the thrombogenic effects of chemotherapy and anti-angiogenic drugs.44

Symptoms (when present) are similar as for the lower extremity (see discussion in Chapter 6). The therapist should be aware of the presence of any risk factors and watch for pain and pitting edema or swelling of the entire (usually upper) limb and/or an area of the limb that is 2 cm or more larger than the surrounding area indicating swelling requiring further investigation.

Other symptoms include redness or warmth of the arm, dilated veins, or low-grade fever possibly accompanied by chills and malaise. Bruising or discoloration of the area or proximal to the thrombosis has been observed in some cases.45 Swelling can contribute to decreased neck or shoulder motion. Severe thromboses can cause superior vena cava syndrome; symptoms include edema of the face and arm, vertigo, and dyspnea.46

Unfortunately, the first clinical manifestation of deep thrombosis may be pulmonary embolism (PE; see also Box 6-2 for overall risk factors for DVT and PE); superficial venous thrombosis is usually self-limiting and does not cause PE since the blood flow to deeper veins is through small perforating venous channels.47

PE as a consequence of upper extremity DVT can be fatal.43 Chronic venous insufficiency or postthrombotic syndrome are possible sequelae to upper extremity DVT.45,48

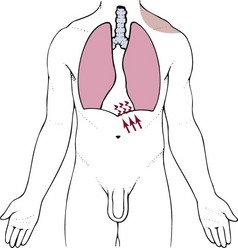

To our knowledge, at this time, a validated screening tool, such as the Wells’ Clinical Decision Rule for DVT, has not been investigated for the upper extremity. A simple model to predict upper extremity DVT has also been proposed and remains under investigation (Table 18-3).49 The best available test for the diagnosis of upper extremity DVT is contrast venography; color Doppler ultrasonography may be preferred for some people because it is noninvasive.50

TABLE 18-3

Possible Predictors of Upper Extremity Deep Venous Thrombosis*

note: As with lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT), a low clinical probability does not exclude the diagnosis of upper extremity DVT. The scoring provides a tool to use in determining the need for additional testing (e.g., ultrasonography, venography).

−1.0 or 0: Low probability of upper extremity DVT

*Concepts presented here are based on one preliminary study validated in a second sample but with a limited patient population; diagnosis was confirmed with ultrasound study.49

Screening for Renal Causes of Upper Quadrant/Shoulder Pain

The anatomic position of the kidneys (and ureters) is in front of and on both sides of the vertebral column at the level of T11 to L3. The right kidney is usually lower than the left.51 The lower portions of the kidneys and the ureters extend below the ribs and are separated from the abdominal cavity by the peritoneal membrane. Because of its location in the posterior upper abdominal cavity in the retroperitoneal space, touching the diaphragm, the upper urinary tract can refer pain to the (ipsilateral) shoulder on the same side as the involved kidney.

Renal sensory innervation is not completely understood; the capsule (covering of the kidney) and the lower portions of the collecting system seem to cause pain with stretching (distention) or puncture. Information transmitted by renal and ureteral pain receptors is relayed by sympathetic nerves that enter the spinal cord at T10 to L1; therefore renal and ureteral pain is typically felt in the posterior subcostal and costovertebral regions (flank).52-54

Renal pain is aching and dull in nature but can occasionally be a severe, boring type of pain. The distention or stretching of the renal capsule, pelvis, or collecting system from intrarenal fluid accumulation (e.g., inflammatory edema, inflamed or bleeding cysts, and bleeding or neoplastic growths) accounts for the constant, dull, and aching quality of reported pain. Ischemia of renal tissue caused by blockage of blood flow to the kidneys can produce either a constant dull or sharp pain. True renal pain is seldom affected by change in position or movements of the shoulder or spine.

If the diaphragm becomes irritated because of pressure from a renal lesion, ipsilateral shoulder pain can be the only symptom or may occur in conjunction with other pain and associated signs and symptoms. For example, generalized abdominal pain may develop accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and impaired intestinal motility (progressing to intestinal paralysis) when pain is acute and severe. Nerve fibers from the renal plexus are also in direct communication with the spermatic plexus, and because of this close relationship, testicular pain may also accompany renal pain in males.55

Elevation in temperature or changes in color, odor, or amount of urine (flow, frequency, nocturia) presenting with shoulder pain should be reported to a physician. Shoulder pain that is not affected by movement or provocation tests requires a closer look.

The presence of constitutional symptoms, constant pain (even if dull), and failure to change the symptoms with a position change will also alert the therapist to the need for a more thorough screening examination. A past medical history of cancer is always an important risk factor requiring careful assessment. This is true even when patients/clients have a known or traumatic cause for their symptoms.

Flank pain combined with unexplained weight loss, fever, pain, and hematuria should be reported to the physician. The presence of any amount of blood in the urine always requires referral to a physician for further diagnostic evaluation because this is a primary symptom of urinary tract neoplasm.

Additionally, therapists need to be cognizant that those at high risk for chronic renal disease with associated neuropathies include anyone with diabetes and those with history of significant nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) or acetaminophen use.56

Screening for Gastrointestinal Causes of Shoulder Pain

Upper abdominal or GI problems with diaphragmatic irritation can refer pain to the ipsilateral shoulder. Perforated gastric or duodenal ulcers, gallbladder disease, and hiatal hernia are the most likely GI causes of shoulder pain seen in the physical therapy clinic. Usually there are associated signs and symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, anorexia, melena, or early satiety, but the client may not connect the shoulder pain with GI disorders. A few screening questions may be all that is needed to uncover any coincident GI symptoms.

The therapist should look for a history of previous ulcer, especially in association with the use of NSAIDs. Shoulder pain that is worse 2 to 4 hours after taking the NSAID can be suggestive of GI bleeding and is considered a yellow (caution) flag. With a true musculoskeletal problem, peak NSAID dosage (usually 2 to 4 hours after ingestion; variable with each drug) should reduce or alleviate painful shoulder symptoms. Any pain increase instead of decrease may be a symptom of GI bleeding.

The therapist must also ask about the effect of eating on shoulder pain. If eating makes shoulder pain better or worse (anywhere from 30 minutes to 2 hours after eating), there may be a GI problem. The client may not be aware of the link between these two events until the therapist asks. If the client is not sure, follow-up at a future appointment and ask again if the client has noticed any unusual symptoms or connection between eating and shoulder pain.

Screening for Liver and Biliary Causes of Shoulder/Upper Quadrant Symptoms

As with many of the organ systems in the human body, the hepatic and biliary organs (liver, gallbladder, and common bile duct) can develop diseases that mimic primary musculoskeletal lesions.

The musculoskeletal symptoms associated with hepatic and biliary pathologic conditions are generally confined to the midback, scapular, and right shoulder regions. These musculoskeletal symptoms can occur alone (as the only presenting symptom) or in combination with other systemic signs and symptoms. Fortunately, in most cases of shoulder pain referred from visceral processes, shoulder motion is not compromised and local tenderness is not a prominent feature.

Diagnostic interviewing is especially helpful when clients have avoided medical treatment for so long that shoulder pain caused by hepatic and biliary diseases may in turn create biomechanical changes in muscular contractions and shoulder movement. These changes eventually create pain of a biomechanical nature.57

Referred shoulder pain may be the only presenting symptom of hepatic or biliary disease. Sympathetic fibers from the biliary system are connected through the celiac and splanchnic plexuses to the hepatic fibers in the region of the dorsal spine. These connections account for the intercostal and radiating interscapular pain that accompanies gallbladder disease (see Fig. 9-10). Although the innervation is bilateral, most of the biliary fibers reach the cord through the right splanchnic nerves, producing pain in the right shoulder.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

There are many potential causes of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), both musculoskeletal and systemic (see Table 11-2). Careful evaluation is required (see Box 9-1). The presence of bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome warrants a closer look. For example, liver dysfunction resulting in increased serum ammonia and urea levels can result in impaired peripheral nerve function.

Ammonia from the intestine (produced by protein breakdown) is normally transformed by the liver to urea, glutamine, and asparagine, which are then excreted by the renal system. When the liver does not detoxify ammonia, ammonia is transported to the brain, where it reacts with glutamate (excitatory neurotransmitter), producing glutamine.

The reduction of brain glutamate impairs neurotransmission, leading to altered central nervous system metabolism and function. Asterixis and numbness/tingling (misinterpreted as carpal tunnel syndrome) can occur as a result of this ammonia abnormality, causing an intrinsic nerve pathologic condition (see Case Example 9-1).

For any client presenting with bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome:

• Ask about the presence of similar symptoms in the feet

• Ask about a personal history of liver or hepatic disease (e.g., cirrhosis, cancer, hepatitis)

• Look for a history of hepatotoxic drugs (see Box 9-3)

• Look for a history of alcoholism

• Ask about current or previous use of statins (cholesterol-lowering drugs such as Crestor, Lipitor, or Zocor)

• Look for other signs and symptoms associated with liver impairment (see Clinical Signs and Symptoms of Liver Disease in Chapter 9)

Screening for Rheumatic Causes of Shoulder Pain

A number of systemic rheumatic diseases can appear as shoulder pain, even as unilateral shoulder pain. The HLA-B27–associated spondyloarthropathies (diseases of the joints of the spine), such as ankylosing spondylitis, most frequently involve the SI joints and spine. Involvement of large central joints, such as the hip and shoulder, is common, however.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and its variants likewise frequently involve the shoulder girdle. These systemic rheumatic diseases are suggested by the details of the shoulder examination, by coincident systemic complaints of malaise and easy fatigability, and by complaints of discomfort in other joints either coincidental with the presenting shoulder complaint or in the past.

Other systemic rheumatic diseases with major shoulder involvement include polymyalgia rheumatica and polymyositis (inflammatory disease of the muscles). Both may be somewhat asymmetric but almost always appear with bilateral involvement and impressive systemic symptoms.

Screening for Infectious Causes of Shoulder Pain

The most likely infectious causes of shoulder pain in a physical therapy practice include infectious (septic) arthritis (see discussion in Chapter 3 and also Box 3-6), osteomyelitis, and infectious mononucleosis (mono). Immunosuppression for any reason puts people of all ages at risk for infection (Case Example 18-9).

Septic arthritis of the acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) or hand can present as insidious onset of shoulder pain. Likewise, septic arthritis of the sternoclavicular joint (SCJ) can present as chest pain. Usually, there is local tenderness at the affected joint. A possible history of intravenous drug use, diabetes, trauma (puncture wound, surgery, human or animal bite), and infection is usually present. Punching someone in the mouth (hand coming in contact with teeth resulting in a puncture wound) has been reported as a potential cause of septic arthritis. With infection of this type, there may or may not be constitutional symptoms.58,59

Osteomyelitis (bone or bone marrow infection) is caused most commonly by Staphylococcus aureus. Children under 6 months of age are most likely to be affected by Haemophilus influenzae or Streptococcus. Hematogenous spread from a wound, abscess, or systemic infection (e.g., fracture, tuberculosis, urinary tract infection, upper respiratory infection, finger felons) occurs most often. Osteomyelitis of the spine is associated with injection drug use.

Onset of clinical signs and symptoms is usually gradual in adults but may be more sudden in children with high fever, chills, and inability to bear weight through the affected joint. In all ages there is marked tenderness over the site of the infection when the affected bone is superficial (e.g., spinous process, distal femur, proximal tibia). The most reliable way to recognize infection is the presence of both local and systemic symptoms.

Mononucleosis is a viral infection that affects the respiratory tract, liver, and spleen. Splenomegaly with subsequent rupture is a rare but serious cause of left shoulder pain (Kehr’s sign).60 There is usually left upper abdominal pain and, in many cases, trauma to the enlarged spleen (e.g., sports injury) is the precipitating cause in an athlete with an unknown or undiagnosed case of mono. Palpation of the upper left abdomen may reveal an enlarged and tender spleen (see Fig. 4-53).

The virus can be present 4 to 10 weeks before any symptoms develop so the person may not know mono is present. Acute symptoms can include sore throat, headache, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, fever, myalgias, and sometimes, skin rash. Enlarged tonsils can cause noisy or difficult breathing. When asking about the presence of other associated signs and symptoms (current or recent past), the therapist may hear a report of some or all of these signs and symptoms.

Screening for Oncologic Causes of Shoulder Pain

A past medical history of cancer anywhere in the body with new onset of back or shoulder pain (or impairment) is a red-flag finding. Brachial plexus radiculopathy can occur in either or both arms with cancer metastasized to the lymphatics (Case Example 18-10).

Questions about visceral function are relevant when the pattern for malignant invasion at the shoulder emerges. Invasion of the upper humerus and glenoid area by secondary malignant deposits affects the joint and the adjacent muscles (Case Example 18-11).

Muscle wasting is greater than expected with arthritis and follows a bizarre pattern that does not conform to any one neurologic lesion or any one muscle. Localized warmth felt at any part of the scapular area may prove to be the first sign of a malignant deposit eroding bone. Within 1 or 2 weeks after this observation, a palpable tumor will have appeared, and erosion of bone will be visible on x-ray films.61

Primary Bone Neoplasm

Bone cancer occurs chiefly in young people, in whom a causeless limitation of movement of the shoulder leads the physician to order x-rays. If the tumor originates from the shaft of the humerus, the first symptoms may be a feeling of “pins and needles” in the hand, associated with fixation of the biceps and triceps muscles and leading to limitation of movement at the elbow (Case Example 18-12).

Pulmonary (Secondary) Neoplasm

Occasionally, the client requires medical referral because shoulder pain is referred from metastatic lung cancer. When the shoulder is examined, the client is unable to lift the arm beyond the horizontal position. Muscles respond with spasm that limits joint movement.

If the neoplasm interferes with the diaphragm, diaphragmatic pain (C3 to C5) is often felt at the shoulder at each breath (at the fourth cervical dermatome [i.e., at the deltoid area]), in correspondence with the main embryologic derivation of the diaphragm.62 Pain arising from the part of the pleura that is not in contact with the diaphragm is also brought on by respiration but is felt in the chest.

Although the lung is insensitive, large tumors invading the chest wall set up local pain and cause spasm of the pectoralis major muscle, with consequent shoulder pain and/or limitation of elevation of the arm.63 If the neoplasm encroaches on the ribs, stretching the muscle attached to the ribs leads to sympathetic spasm of the pectoralis major. By contrast, the scapula is mobile, and a full range of passive movement is present at the shoulder joint.

Pancoast’s Tumor

Pancoast’s tumors of the lung apex usually do not cause symptoms while confined to the pulmonary parenchyma. Shoulder pain occurs if they extend into the surrounding structures, infiltrating the chest wall into the axilla. Occasionally, brachial plexus involvement (eighth cervical and first thoracic nerve) presents with radiculopathy.64

This nerve involvement produces sharp neuritic pain in the axilla, shoulder, and subscapular area on the affected side, with eventual atrophy of the upper extremity muscles. Bone pain is aching, exacerbated at night, and a cause of restlessness and musculoskeletal movement.65

Usually, general associated systemic signs and symptoms are present (e.g., sore throat, fever, hoarseness, unexplained weight loss, productive cough with blood in the sputum). These features are not found in any regional musculoskeletal disorder, including such disorders of the shoulder.

For example, a similar pain pattern caused by trigger points (TrPs) of the serratus anterior can be differentiated from neoplasm by the lack of true neurologic findings (indicating trigger point) or by lack of improvement after treatment to eliminate the trigger point (indicating neoplasm).

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer or breast cancer recurrence is always a consideration with upper quadrant pain or shoulder dysfunction (Case Example 18-13). The therapist must know what to look for as red flags for cancer recurrence versus delayed effects of cancer treatment. See Chapter 13 for a complete discussion of cancer screening and prevention. Breast cancer is discussed in Chapter 17.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown radiation-induced muscle morbidity in cervical, prostate, and breast cancer. Axillary radiation is a predictive factor for the development of shoulder morbidity.66 Soft tissue changes from radiotherapy is dose dependent and may develop immediately or develop several years later.

Primary muscle shortening and secondary loss of muscle activity may produce movement disorders of the shoulder and/or upper quadrant. Radiation-induced changes in vascular networks resulting in ischemia may affect muscle contractility.67

Screening for Gynecologic Causes of Shoulder Pain

Shoulder pain as a result of gynecologic conditions is uncommon, but still very possible. Occasionally a client may present with breast pain as the primary complaint, but most often the description is of shoulder or arm, neck, or upper back pain. When asked if the client has any symptoms anywhere else in the body, breast pain may be mentioned.

Pain patterns associated with breast disease along with a discussion of various breast pathologies are included in Chapter 17. Many of the breast conditions discussed (e.g., tumors, infections, myalgias, implants, lymph disease, trauma) can refer pain to the shoulder either alone or in conjunction with chest and/or breast pain. Shoulder pain or dysfunction in the presence of any of these conditions as part of the client’s current or past medical history raises a red flag.

Ectopic Pregnancy

The therapist must be aware of one other gynecologic condition commonly associated with shoulder pain: ectopic (extrauterine [i.e., outside the uterus]) pregnancy. This type of pregnancy occurs when the fertilized egg implants in some other part of the body besides inside the uterus. It may be inside the fallopian tube, inside the ovary, outside the uterus or even within the lining of the peritoneum (see Fig. 15-5).25-27

If the condition goes undetected, the embryo grows too large for the confined space. A tear or rupture of the tissue around the fertilized egg will occur. An ectopic pregnancy is not a viable pregnancy and cannot result in a live birth. This condition is life threatening and requires immediate medical referral.

The most common symptom of ectopic pregnancy is a sudden, sharp or constant one-sided pain in the lower abdomen or pelvis lasting more than a few hours. The pain may be accompanied by irregular bleeding or spotting after a light or late menstrual period.

Shoulder pain does not usually occur alone without preceding or accompanying abdominal pain, but shoulder pain can be the only presenting symptom with an ectopic pregnancy. When these two symptoms occur together (either alternating or simultaneously), the woman may not realize the abdominal and shoulder pain are connected. She may think there are two separate problems. She may not see the need to tell the therapist about the pelvic or abdominal pain, especially if she thinks it is menstrual cramps or gas. In addition, ask about the presence of lightheadedness, dizziness, or fainting.

The most likely candidate for an ectopic pregnancy is a woman in the childbearing years who is sexually active. Pregnancy can occur when using any form of birth control, so do not be swayed into thinking the woman cannot be pregnant because she is on the pill or some other form of contraception. Factors that put a woman at increased risk for an ectopic pregnancy include:

• History of endometriosis68

• Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

Many of these conditions can also cause pelvic pain and are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 15. If the therapist suspects a gynecologic basis for the client’s symptoms, some additional questions about past history, missed menses, shoulder pain, and spotting or bleeding may be helpful.

Physician Referral

Here in the last chapter of the text there are no new guidelines for physician referral that have not been discussed in the previous chapters. The therapist must remain alert to yellow (caution) or red (warning) flags in the history and clinical presentation, and ask about associated signs and symptoms.

When symptoms seem out of proportion to the injury or persist beyond the expected time of healing, medical referral may be needed.69 Likewise, pain that is unrelieved by rest or change in position or pain/symptoms that do not fit the expected mechanical or NMS pattern should serve as red-flag warnings. A past medical history of cancer in the presence of any of these clinical presentation scenarios may warrant consultation with the client’s physician.

Guidelines for Immediate Medical Attention

• Presence of suspicious or aberrant lymph nodes, especially hard, fixed nodes in a client with a previous history of cancer

• Clinical presentation and history suggestive of an ectopic pregnancy

• Trauma followed by failure of symptoms to resolve with treatment; pain out of proportion to the injury (Fracture, acute compartment syndrome)

Clues to Screening Shoulder/Upper Extremity Pain

• See also Clues to Screening Chest, Breast, or Rib Pain in Chapter 17

• Simultaneous or alternating pain in other joints, especially in the presence of associated signs and symptoms such as easy fatigue, malaise, fever

• Presence of hepatic symptoms, especially when accompanied by risk factors for jaundice

• Lack of improvement after treatment, including trigger point therapy

• Shoulder pain in a woman of childbearing age of unknown cause associated with missed menses (Rupture of ectopic pregnancy)

• Left shoulder pain within 24 hours of abdominal surgery, injury, or trauma (Kehr’s sign, ruptured spleen)

Past Medical History

• History of rheumatic disease

• History of diabetes mellitus (Adhesive capsulitis)

• “Frozen” shoulder of unknown cause in anyone with coronary artery disease, recent history of hospitalization in CCU or ICU/s/p CABG

• Recent history (past 1-3 months) of MI (CRPS; formerly RSD)

• History of cancer, especially breast or lung cancer (Metastasis)

• Recent history of pneumonia, recurrent upper respiratory infection, or influenza (Diaphragmatic pleurisy)

Cancer

Cardiac

• Exacerbation by exertion unrelated to shoulder movement (e.g., using only the lower extremities to climb stairs or ride a stationary bicycle)

• Excessive, unexplained coincident diaphoresis

• Shoulder pain relieved by leaning forward, kneeling with hands on the floor, sitting upright (Pericarditis)

• Shoulder pain accompanied by dyspnea, toothache, belching, nausea, or pressure behind the sternum (Angina)

• Shoulder pain relieved by nitroglycerin (men) or antacids/acid-relieving drugs (women) (Angina)

• Difference of 10 mm Hg or more in blood pressure in the affected arm compared to the uninvolved or a symptomatic arm (Dissecting aortic aneurysm, vascular component of TOS)

Pulmonary

• Presence of a pleuritic component such as a persistent, dry, hacking, or productive cough; blood-tinged sputum; chest pain; musculoskeletal symptoms are aggravated by respiratory movements

• Exacerbation by recumbency despite proper positioning of the arm in neutral alignment (Diaphragmatic or pulmonary component)

• Presence of associated signs and symptoms (e.g., tachypnea, dyspnea, wheezing, hyperventilation)

• Shoulder pain of unknown cause in older adults with accompanying signs of confusion or increased confusion (Pneumonia)

• Shoulder pain aggravated by the supine position may be an indication of mediastinal or pleural involvement. Shoulder or back pain alleviated by lying on the painful side may indicate autosplinting. (Pleural)

Renal

• Shoulder pain accompanied by elevation in temperature or changes in color, odor, or amount of urine (flow, frequency, nocturia); pain is not affected by movement or provocation tests.

• Shoulder pain accompanied by or alternating with flank pain, abdominal pain, or pelvic pain or, in men, testicular pain

Gastrointestinal

• Coincident nausea, vomiting, dysphagia; presence of other GI complaints such as anorexia, early satiety, epigastric pain or discomfort and fullness, melena

• Shoulder pain relieved by belching or antacids and made worse by eating

• History of previous ulcer, especially in association with the use of NSAIDs

Gynecologic

• Shoulder pain preceded or accompanied by one-sided lower abdominal or pelvic pain in a sexually active woman of reproductive age may be a symptom of ectopic pregnancy; there may be irregular bleeding or spotting after a light or late menstrual period.

• Shoulder pain with reports of lightheadedness, dizziness, or fainting in a sexually active woman of reproductive age (Ectopic pregnancy)

• Presence of endometrial cysts and/or scar tissue impinging diaphragm, nerve plexus, or the shoulder itself

1. A 66-year-old woman has been referred to you by her physiatrist for preprosthetic training after an above-knee amputation. Her past medical history is significant for chronic diabetes mellitus (insulin dependent), coronary artery disease with recent angioplasty and stent placement, and peripheral vascular disease. During the physical therapy evaluation, the client experienced anterior neck pain radiating down the left arm. Name (and/or describe) three tests you can do to differentiate a musculoskeletal cause from a cardiac cause of shoulder pain.

2. Which of the following would be useful information when evaluating a 57-year-old woman with shoulder pain?

3. Referred pain patterns associated with impairment of the spleen can produce musculoskeletal symptoms in:

4. Referred pain patterns associated with hepatic and biliary pathology can produce musculoskeletal symptoms in:

5. The most common sites of referred pain from systemic diseases are:

6. A 28-year-old mechanic reports bilateral shoulder pain (right more than left) whenever he has to work on a car on a lift overhead. It goes away as soon as he puts his arms down. Sometimes, he has numbness and tingling in his right elbow going down the inside of his forearm to his thumb. The most likely explanation for this pattern of symptoms is:

7. A client reports shoulder and upper trapezius pain on the right that increases with deep breathing. How can you tell if this results from a pulmonary or a musculoskeletal cause?

a. Symptoms get worse when lying supine but better when right sidelying when it is pulmonary

b. Symptoms get worse when lying supine but better when right sidelying when it is musculoskeletal

8. Organ systems that can cause simultaneous bilateral shoulder pain include:

9. A 23-year-old woman was a walk-in to your clinic with sudden onset of left shoulder pain. She denies any history of trauma and has only a past history of a ruptured appendix three years ago. She is not having any abdominal pain or pain anywhere else in her body. How do you know if she is at risk for ectopic pregnancy?

a. She is sexually active, and her period is late.

b. She has a history of uterine cancer.

10. The most significant red flag for shoulder pain secondary to cancer is:

References

1. Walsh, RM, Sadowski, GE. Systemic disease mimicking musculoskeletal dysfunction: A case report involving referred shoulder pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2001;31(12):696–701.

2. Berg, J. Symptoms of a first acute myocardial infarction in men and women. Gend Med. 2009;6(3):454–462.

3. Lovlien, M. Early warning signs of an acute myocardial infarction and their influence on symptoms during the acute phase, with comparisons by gender. Gend Med. 2009;6(3):444–453.

4. Hwang, SY. Comparison of factors associated with atypical symptoms in younger and older patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24(5):789–794.

5. Rubba, F. Vascular preventive measures: The progression from asymptomatic to symptomatic atherosclerosis management. Evidence on usefulness of early diagnosis in women and children. Future Cardiol. 2010;6(2):211–220.

6. Vercoza, AM. Cardiovascular risk factors and carotid intima-media thickness in asymptomatic children. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30(8):1055–1060.

7. Smith, ML. Differentiating angina and shoulder pathology pain. Phys Ther Case Rep. 1998;1(4):210–212.

8. Ogawa, K. Advanced shoulder joint tuberculosis treated with debridement and closed continuous irrigation and suction. Am J Orthop. 2010;39(2):E15–18.

9. Ba-Fall, K. Shoulder pain revealing tuberculosis of the humerus. Rev Pneumonol. 2009;65(1):13–15.

10. Nagaraj, C. Tuberculosis of the shoulder joint with impingement syndrome as initial presentation. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2008;41(3):275–278.

11. Wohlgethan, JR. Frozen shoulder in hyperthyroidism. Arthritis Rheum. Aug 1987;30(8):936–939.

12. Roy, A, Adhesive capsulitis in physical medicine and rehabilitation. eMedicine Specialties 2009. Available online at Updated Oct. 15 http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/326828-overview. [Accessed March 21, 2011].

13. Lebiedz-Odrobina, D. Rheumatic manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2010;36(4):681–699.

14. Garcilazo, C. Shoulder manifestations of diabetes mellitus. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2010;6(5):334–340.

15. Saha, NC. Painful shoulder in patients with chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1966;94:455–456.

16. Okada, M, Suzuki, K, Hidaka, T, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome type I induced by pacemaker implantation, with a good response to steroids and neurotrophin. Intern Med. 2002;41:498–501.

17. Mennell, JM. The musculoskeletal system: differential diagnosis from symptoms and physical signs. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 1992.

18. Leff, D. Ruptured spleen following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2007;11(1):157–160.

19. Sharami, SH. Randomised clinical trial of the influence of pulmonary recruitment manoeuvre on reducing shoulder pain after laparoscopy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;30(5):505–510.

20. Shin, HY. The effect of mechanical ventilation tidal volume during pneumoperitoneum on shoulder pain after a laparoscopic appendectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):2002–2007.

21. Giles, LGF, Singer, KP. The clinical anatomy and management of thoracic spine pain. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 2000.

22. Kandil, TS. Shoulder pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Factors affecting the incidence and severity. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20(8):677–682.

23. Chang, SH. An evaluation of perioperative pregabalin for prevention and attenuation of postoperative shoulder pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(4):1284–1286.

24. Hadler, NM. The patient with low back pain. Hosp Pract. October 30, 1987:17–22.

25. Biolchini, F. Emergency laparoscopic splenectomy for haemoperitoneum because of ruptured primary splenic pregnancy: a case report and review of literature. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80(102):55–57.

26. Dennert, IM. Ectopic pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):377–379.

27. Bildik, F. Heterotopic pregnancy presenting with acute left chest pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26(7):835.e1–835.e2.

28. Smith, ML. Differentiating angina and shoulder pathology pain. Phys Ther Case Rep. 1998;1(4):210–212.

29. Oaklander, AL, Rissmiller, JG, Gelman, LB, et al. Evidence of focal small-fiber axonal degeneration in complex regional pain syndrome-I (reflex sympathetic dystrophy). Pain. 2006;120(3):235–243.

30. Jänig, W, Baron, R. Is CRPS I a neuropathic pain syndrome? Pain. 2006;120(3):227–229.

31. Jänig, W. The fascination of complex regional pain syndrome. Exp Neurol. 2010;221(1):1–4.

32. Duman, I. Reflex sympathetic dystrophy secondary to deep venous thrombosis mimicking post-thrombotic syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2009;30(2):249–252.

33. Eyers, P, Earnshaw, JJ. Acute non-traumatic arm ischemia. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1340–1346.

34. Brinkley, DM, Hepper, CT. Heart in hand: structural cardiac abnormalities that manifest as acute dysvascularity of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A(12):2101–2103.

35. American Heart Association. Pericardium and pericarditis. Available online at http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4683. [Accessed March 22, 2011].

36. Texas Heart Institute. Aneurysms and dissections. Available online at http://www.texasheartinstitute.org/hic/topics/cond/aneurysm.cfm. [Accessed March 22, 2011].

37. Tran, H. Deep venous thromboses in patients with hematological malignancies after peripherally inserted central venous catheters. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(8):1473–1477.

38. Jones, MA. Characterizing resolution of catheter-associated upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(1):108–113.

39. Shah, MK. Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis. South Med J. 2003;96(7):669–672.

40. Linneman, B. Hereditary and acquired thrombophilia in patients with upper extremity deep-vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;100(3):440–446.

41. Jones, RE. Upper limb deep vein thrombosis: a potentially fatal complication of clavicle fracture. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(5):W36–38.

42. Garofalo, R. Deep vein thromboembolism after arthroscopy of the shoulder: two case reports and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskel Disord. 2010;11:65.

43. Willis, AA. Deep vein thrombosis after reconstructive shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective observational study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):100–106.

44. Farge, D. Lessons from French National Guidelines on the treatment of venous thrombosis and central venous catheter thrombosis in cancer patients. Thromb Res. 2010;125(Suppl 2):S108–S116.

45. Lancaster, SL. Upper-extremity deep vein thrombosis. AJN. 2010;110(5):48–52.

46. Gaitini, D. Prevalence of upper extremity deep venous thrombosis diagnosed by color Doppler duplex sonography in cancer patients with central venous catheters. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(10):1297–1303.

47. Joffe, HV. Upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: a prospective registry of 592 patients. Circulation. 2004;110:1605–1611.

48. Otten, TR. Thromboembolic disease involving the superior vena cava and brachiocephalic veins. Chest. 2003;123(3):809–812.

49. Constans, J. A clinical prediction score for upper extremity deep venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:202–207.

50. Di Nisio, M. Accuracy of diagnostic tests for clinically suspected upper extremity deep vein thrombosis: a systematic review. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(4):684–692.

51. Netter, FH. Atlas of human anatomy, ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2010.

52. Moore, KL. Clinically oriented anatomy, ed 6. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2009.

53. Pedersen, KV. Flank pain in renal and ureteral calculus. Ugeskr Laeger. 2011;173(7):503–505.

54. Pedersen, KV. Visceral pain originating from the upper urinary tract. Urol Res. 2010;38(5):345–355.

55. Delavierre, D. Symptomatic approach to referred chronic pelvic and perineal pain and posterior ramus syndrome. Prog Urol. 2010;20(12):990–994.

56. Myslinski MJ: NSAIDs: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Lecture presented at the APTA Combined Sections Meeting, Las Vegas, NV, February 11, 2009.

57. Rose, SJ, Rothstein, JM. Muscle mutability: general concepts and adaptations to altered patterns of use. Phys Ther. 1982;62:1773.

58. Yung, E. Screening for head, neck, and shoulder pathology in patients with upper extremity signs and symptoms. J Hand Ther. 2010;23:173–186.

59. McKay, P. Osteomyelitis and septic arthritis of the hand and wrist. Curr Ortho Pract. 2010;21(6):542–550.

60. Bonsignore, A. Occult rupture of the spleen in a patient with infectious mononucleosis. G Chir. 2010;31(3):86–90.

61. Cyriax, J. Textbook of orthopaedic medicine, ed 8. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1982.

62. Schumpelick, V. Surgical embryology and anatomy of the diaphragm with surgical applications. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80(1):213–239.

63. Tateishi, U, Chest wall tumors: radiologic findings and pathologic correlation. RadioGraphics 2003;23:1491–1508. Available online at http://radiographics.rsna.org/content/23/6/1491.full. [Accessed March 22, 2011].

64. Bhimji, S. Pancoast tumor. eMedicine Specialties—Thoracic Surgery (Tumors). August 3, 2010. Available online at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/428469-overview. [Accessed March 2, 2011].

65. Cailliet, R. Shoulder pain, ed 3. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1991.

66. Reitman, J. Late morbidity after treatment of breast cancer in relation to daily activities and quality of life: a systematic review. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:229–238.

67. Shamley, DR. Changes in shoulder muscle size and activity following treatment for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(1):19–27.

68. Seoud, AA. Endometriosis: a possible cause of right shoulder pain. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2010;37(1):19–20.

69. Prasarn, ML, Ouellette, EA. Acute compartment syndrome of the upper extremity. JAAOS. 2011;19(1):49–58.

70. McFarland, EG, Sanguanjit, P, Tasaki, A, et al. Shoulder examination: established and evolving concepts. J Musculoskel Med. 2006;23(1):57–64.

71. McFarland, EG. Clinical and diagnostic tests for shoulder disorders: a critical review. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44(5):328–332.

72. Neer, CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg. 1972;54(1):41–50.

73. Labidi, M. Pleural effusions following cardiac surgery: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical features. Chest. 2009;136(6):1604–1611.

74. Ashikhmina, EA. Pericardial effusion after cardiac surgery: risk factors, patient profiles, and contemporary management. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89(1):112–118.

75. Ahmed, WA. Survival after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87(4):1106–1112.

76. Jensen, L. Risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications in coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients. Eur J Cardiovasc. 2007;6(3):241–246.

Key Points to Remember

Key Points to Remember