Introduction to Screening for Referral in Physical Therapy

It is the therapist’s responsibility to make sure that each patient/client is an appropriate candidate for physical therapy. In order to be as cost-effective as possible, we must determine what biomechanical or neuromusculoskeletal problem is present and then treat the problem as specifically as possible.

As part of this process, the therapist may need to screen for medical disease. Physical therapists must be able to identify signs and symptoms of systemic disease that can mimic neuromuscular or musculoskeletal (herein referred to as neuromusculoskeletal or NMS) dysfunction. Peptic ulcers, gallbladder disease, liver disease, and myocardial ischemia are only a few examples of systemic diseases that can cause shoulder or back pain. Other diseases can present as primary neck, upper back, hip, sacroiliac, or low back pain and/or symptoms.

Cancer screening is a major part of the overall screening process. Cancer can present as primary neck, shoulder, chest, upper back, hip, groin, pelvic, sacroiliac, or low back pain/symptoms. Whether there is a primary cancer or cancer that has recurred or metastasized, clinical manifestations can mimic NMS dysfunction. The therapist must know how and what to look for to screen for cancer.

The purpose and the scope of this text are not to teach therapists to be medical diagnosticians. The purpose of this text is twofold. The first is to help therapists recognize areas that are beyond the scope of a physical therapist’s practice or expertise. The second is to provide a step-by-step method for therapists to identify clients who need a medical (or other) referral or consultation.

As more states move toward direct access and advanced scope of practice, physical therapists are increasingly becoming the practitioner of choice and thereby the first contact that patient/clients seek,* particularly for care of musculoskeletal dysfunction. This makes it critical for physical therapists to be well versed in determining when and how referral to a physician (or other appropriate health care professional) is necessary. Each individual case must be reviewed carefully.

Even without direct access, screening is an essential skill because any client can present with red flags requiring reevaluation by a medical specialist. The methods and clinical decision-making model for screening presented in this text remain the same with or without direct access and in all practice settings.

Evidence-Based Practice

Clinical decisions must be based on the best evidence available. The clinical basis for diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention must come from a valid and reliable body of evidence referred to as evidence-based practice. Each therapist must develop the skills necessary to assimilate, evaluate, and make the best use of evidence when screening patient/clients for medical disease.

Every effort has been made to sift through all the pertinent literature, but it remains up to the reader to keep up with peer-reviewed literature reporting on the likelihood ratios, predictive values, reliability, sensitivity, specificity, and validity of yellow (cautionary) and red (warning) flags and the confidence level/predictive value behind screening questions and tests. Each therapist will want to build his or her own screening tools based on the type of practice he or she is engaged in by using best evidence screening strategies available. These strategies are rapidly changing and will require careful attention to current patient-centered peer-reviewed research/literature.

Evidence-based clinical decision making consistent with the patient/client management model as presented in the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice1 will be the foundation upon which a physical therapist’s differential diagnosis is made. Screening for systemic disease or viscerogenic causes of NMS symptoms begins with a well-developed client history and interview.

The foundation for these skills is presented in Chapter 2. In addition, the therapist will rely heavily on clinical presentation and the presence of any associated signs and symptoms to alert him or her to the need for more specific screening questions and tests.

Under evidence-based medicine, relying on a red-flag checklist based on the history has proved to be a very safe way to avoid missing the presence of serious disorders. Efforts are being made to validate red flags currently in use (see further discussion in Chapter 2). When serious conditions have been missed, it is not for lack of special investigations but for lack of adequate and thorough attention to clues in the history.2,3

Some conditions will be missed even with screening because the condition is early in its presentation and has not progressed enough to be recognizable. In some cases, early recognition makes no difference to the outcome, either because nothing can be done to prevent progression of the condition or there is no adequate treatment available.2

Statistics

How often does it happen that a systemic or viscerogenic problem masquerades as a neuromuscular or musculoskeletal problem? There are very limited statistics to quantify how often organic disease masquerades or presents as NMS problems. Osteopathic physicians suggest this happens in approximately 1% of cases seen by physical therapists, but little data exist to confirm this estimate.4,5 At the present time, the screening concept remains a consensus-based approach patterned after the traditional medical model and research derived from military medicine (primarily case studies).

Efforts are underway to develop a physical therapists’ national database to collect patient/client data that can assist us in this effort. Again, until reliable data are available, it is up to each of us to look for evidence in peer-reviewed journals to guide us in this process.

Personal experience suggests the 1% figure would be higher if therapists were screening routinely. In support of this hypothesis, a systematic review of 64 cases involving physical therapist referral to physicians with subsequent diagnosis of a medical condition showed that 20% of referrals were for other concerns.6 Physical therapists involved in the cases were routinely performing screening examinations, regardless of whether or not the client was initially referred to the physical therapist by a physician.

These results demonstrate the importance of therapists screening beyond the chief presenting complaint (i.e., for this group the red flags were not related to the reason physical therapy was started). For example, one client came with diagnosis of cervical stenosis. She did have neck problems, but the therapist also observed an atypical skin lesion during the postural exam and subsequently made the referral.6

Key Factors to Consider

Three key factors that create a need for screening are:

If the medical diagnosis is delayed, then the correct diagnosis is eventually made when

1. The patient/client does not get better with physical therapy intervention.

There are times when a patient/client with NMS complaints is really experiencing the side effects of medications. In fact, this is probably the most common source of associated signs and symptoms observed in the clinic. Side effects of medication as a cause of associated signs and symptoms, including joint and muscle pain, will be discussed more completely in Chapter 2. Visceral pain mechanisms are the entire subject of Chapter 3.

As for comorbidities, many patient/clients are affected by other conditions such as depression, diabetes, incontinence, obesity, chemical dependency, hypertension, osteoporosis, and deconditioning, to name just a few. These conditions can contribute to significant morbidity (and mortality) and must be documented as part of the problem list. Physical therapy intervention is often appropriate in affecting outcomes, and/or referral to a more appropriate health care or other professional may be needed.

Finally, consider the fact that some clients with a systemic or viscerogenic origin of NMS symptoms get better with physical therapy intervention. Perhaps there is a placebo effect. Perhaps there is a physiologic effect of movement on the diseased state. The therapist’s intervention may exert an influence on the neuroendocrine-immune axis as the body tries to regain homeostasis. You may have experienced this phenomenon yourself when coming down with a cold or symptoms of a virus. You felt much better and even symptom-free after exercising.

Movement, physical activity, and moderate exercise aid the body and boost the immune system,7-9 but sometimes such measures are unable to prevail, especially if other factors are present such as inadequate hydration, poor nutrition, fatigue, depression, immunosuppression, and stress. In such cases the condition will progress to the point that warning signs and symptoms will be observed or reported and/or the patient/client’s condition will deteriorate. The need for medical referral or consultation will become much more evident.

Reasons to Screen

There are many reasons why the therapist may need to screen for medical disease. Direct access (see definition and discussion later in this chapter) is only one of those reasons (Box 1-1).

Early detection and referral is the key to prevention of further significant comorbidities or complications. In all practice settings, therapists must know how to recognize systemic disease masquerading as NMS dysfunction. This includes practice by physician referral, practitioner of choice via the direct access model, or as a primary practitioner.

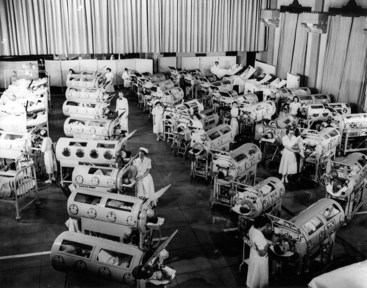

The practice of physical therapy has changed many times since it was first started with the Reconstruction Aides. Clinical practice, as it was shaped by World War I and then World War II, was eclipsed by the polio epidemic in the 1940s and 1950s. With the widespread use of the live, oral polio vaccine in 1963, polio was eradicated in the United States and clinical practice changed again (Fig. 1-1).

Fig. 1-1 Patients in iron lungs receive treatment at Rancho Los Amigos during the polio epidemic of the 1940s and 1950s. (Courtesy Rancho Los Amigos, 2005.)

Today, most clients seen by therapists have impairments and disabilities that are clearly NMS-related (Fig. 1-2). Most of the time, the client history and mechanism of injury point to a known cause of movement dysfunction.

Fig. 1-2 (Courtesy Jim Baker, Missoula, Montana, 2005.)

However, therapists practicing in all settings must be able to evaluate a patient/client’s complaint knowledgeably and determine whether there are signs and symptoms of a systemic disease or a medical condition that should be evaluated by a more appropriate health care provider. This text endeavors to provide the necessary information that will assist the therapist in making these decisions.

Quicker and Sicker

The aging of America has impacted general health in significant ways. “Quicker and sicker” is a term used to describe patient/clients in the current health care arena (Fig. 1-3).10 “Quicker” refers to how health care delivery has changed in the last 10 years to combat the rising costs of health care. In the acute care setting, the focus is on rapid recovery protocols. As a result, earlier mobility and mobility with more complex patients are allowed.11 Better pharmacologic management of agitation has allowed earlier and safer mobility. Hospital inpatient/clients are discharged much faster today than they were even 10 years ago. Patients are discharged from the intensive care unit (ICU) to rehab or even home. Outpatient/client surgery is much more common, with same-day discharge for procedures that would have required a much longer hospitalization in the past. Patient/clients on the medical-surgical wards of most hospitals today would have been in the ICU 20 years ago.

Fig. 1-3 The aging of America from the “traditionalists” (born before 1946) and the Baby Boom generation (“boomer” born 1946-1964) will result in older adults with multiple comorbidities in the care of the physical therapist. Even with a known orthopedic and/or neurologic impairment, these clients will require a careful screening for the possibility of other problems, side effects from medications, and primary/secondary prevention programs. (From Sorrentino SA: Mosby’s textbook for nursing assistants, ed 7, St. Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Today’s health care environment is complex and highly demanding. The therapist must be alert to red flags of systemic disease at all times but especially in those clients who have been given early release from the hospital or transition unit. Warning flags may come in the form of reported symptoms or observed signs. It may be a clinical presentation that does not match the recent history. Red warning and yellow caution flags will be discussed in greater detail later in this chapter.

“Sicker” refers to the fact that patient/clients in acute care, rehabilitation, or outpatient/client setting with any orthopedic or neurologic problems may have a past medical history of cancer or a current personal history of diabetes, liver disease, thyroid condition, peptic ulcer, and/or other conditions or diseases.

The number of people with at least one chronic disease or disability is reaching epidemic proportions. According to the National Institute on Aging,12 79% of adults over 70 have at least one of seven potentially disabling chronic conditions (arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, respiratory diseases, stroke, and cancer).13 The presence of multiple comorbidities emphasizes the need to view the whole patient/client and not just the body part in question.

In addition, the number of people who do not have health insurance and who wait longer to seek medical attention are sicker when they access care. This factor, combined with the American lifestyle that leads to chronic conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, results in a sicker population base.14

Natural History

Improvements in treatment for neurologic and other conditions previously considered fatal (e.g., cancer, cystic fibrosis) are now extending the life expectancy for many individuals. Improved interventions bring new areas of focus such as quality-of-life issues. With some conditions (e.g., muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy), the artificial dichotomy of pediatric versus adult care is gradually being replaced by a lifestyle approach that takes into consideration what is known about the natural history of the condition.

Many individuals with childhood-onset diseases now live well into adulthood. For them, their original pathology or disease process has given way to secondary impairments. These secondary impairments create further limitation and issues as the person ages. For example, a 30-year-old with cerebral palsy may experience chronic pain, changes or limitations in ambulation and endurance, and increased fatigue.

These symptoms result from the atypical movement patterns and musculoskeletal strains caused by chronic increase in tone and muscle imbalances that were originally caused by cerebral palsy. In this case, the screening process may be identifying signs and symptoms that have developed as a natural result of the primary condition (e.g., cerebral palsy) or long-term effects of treatment (e.g., chemotherapy, biotherapy, or radiotherapy for cancer).

Signed Prescription

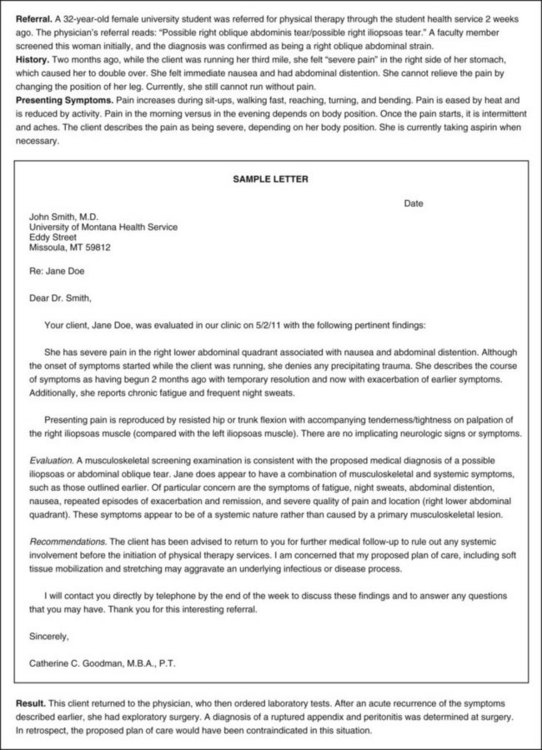

Under direct access, the physical therapist may have primary responsibility or become the first contact for some clients in the health care delivery system. On the other hand, clients may obtain a signed prescription for physical therapy from their primary care physician or other health care provider, based on similar past complaints of musculoskeletal symptoms, without actually seeing the physician or being examined by the physician (Case Example 1-1).

Medical Specialization

Additionally, with the increasing specialization of medicine, clients may be evaluated by a medical specialist who does not immediately recognize the underlying systemic disease, or the specialist may assume that the referring primary care physician has ruled out other causes (Case Example 1-2).

Progression of Time and Disease

In some cases, early signs and symptoms of systemic disease may be difficult or impossible to recognize until the disease has progressed enough to create distressing or noticeable symptoms (Case Example 1-3). In some cases, the patient/client’s clinical presentation in the physician’s office may be very different from what the therapist observes when days or weeks separate the two appointments. Holidays, vacations, finances, scheduling conflicts, and so on can put delays between medical examination and diagnosis and that first appointment with the therapist.

Given enough time, a disease process will eventually progress and get worse. Symptoms may become more readily apparent or more easily clustered. In such cases, the alert therapist may be the first to ask the patient/client pertinent questions to determine the presence of underlying symptoms requiring medical referral.

The therapist must know what questions to ask clients in order to identify the need for medical referral. Knowing what medical conditions can cause shoulder, back, thorax, pelvic, hip, sacroiliac, and groin pain is essential. Familiarity with risk factors for various diseases, illnesses, and conditions is an important tool for early recognition in the screening process.

Patient/Client Disclosure

Finally, sometimes patient/clients tell the therapist things about their current health and social history unknown or unreported to the physician. The content of these conversations can hold important screening clues to point out a systemic illness or viscerogenic cause of musculoskeletal or neuromuscular impairment.

Yellow or Red Flags

A large part of the screening process is identifying yellow (caution) or red (warning) flag histories and signs and symptoms (Box 1-2). A yellow flag is a cautionary or warning symptom that signals “slow down” and think about the need for screening. Red flags are features of the individual’s medical history and clinical examination thought to be associated with a high risk of serious disorders such as infection, inflammation, cancer, or fracture.15 A red-flag symptom requires immediate attention, either to pursue further screening questions and/or tests or to make an appropriate referral.

The presence of a single yellow or red flag is not usually cause for immediate medical attention. Each cautionary or warning flag must be viewed in the context of the whole person given the age, gender, past medical history, known risk factors, medication use, and current clinical presentation of that patient/client.

Clusters of yellow and/or red flags do not always warrant medical referral. Each case is evaluated on its own. It is time to take a closer look when risk factors for specific diseases are present or both risk factors and red flags are present at the same time. Even as we say this, the heavy emphasis on red flags in screening has been called into question.16,17

It has been reported that in the primary care (medical) setting, some red flags have high false-positive rates and have very little diagnostic value when used by themselves.5 Efforts are being made to identify reliable red flags that are valid based on patient-centered clinical research. Whenever possible, those yellow/red flags are reported in this text.5,18,19

The patient/client’s history, presenting pain pattern, and possible associated signs and symptoms must be reviewed along with results from the objective evaluation in making a treatment-versus-referral decision.

Medical conditions can cause pain, dysfunction, and impairment of the

For the most part, the organs are located in the central portion of the body and refer symptoms to the nearby major muscles and joints. In general, the back and shoulder represent the primary areas of referred viscerogenic pain patterns. Cases of isolated symptoms will be presented in this text as they occur in clinical practice. Symptoms of any kind that present bilaterally always raise a red flag for concern and further investigation (Case Example 1-4).

Monitoring vital signs is a quick and easy way to screen for medical conditions. Vital signs are discussed more completely in Chapter 4. Asking about the presence of constitutional symptoms is important, especially when there is no known cause. Constitutional symptoms refer to a constellation of signs and symptoms present whenever the patient/client is experiencing a systemic illness. No matter what system is involved, these core signs and symptoms are often present (Box 1-3).

Medical Screening Versus Screening for Referral

Therapists can have an active role in both primary and secondary prevention through screening and education. Primary prevention involves stopping the process(es) that lead to the development of diseases such as diabetes, coronary artery disease, or cancer in the first place (Box 1-4).

According to the Guide,1 physical therapists are involved in primary prevention by “preventing a target condition in a susceptible or potentially susceptible population through such specific measures as general health promotion efforts” [p. 33]. Risk factor assessment and risk reduction fall under this category.

Secondary prevention involves the regular screening for early detection of disease or other health-threatening conditions such as hypertension, osteoporosis, incontinence, diabetes, or cancer. This does not prevent any of these problems but improves the outcome. The Guide outlines the physical therapist’s role in secondary prevention as “decreasing duration of illness, severity of disease, and number of sequelae through early diagnosis and prompt intervention” [p. 33].

Although the terms screening for medical referral and medical screening are often used interchangeably, these are really two separate activities. Medical screening is a method for detecting disease or body dysfunction before an individual would normally seek medical care. Medical screening tests are usually administered to individuals who do not have current symptoms, but who may be at high risk for certain adverse health outcomes (e.g., colonoscopy, fasting blood glucose, blood pressure monitoring, assessing body mass index, thyroid screening panel, cholesterol screening panel, prostate-specific antigen, mammography).

In the context of a human movement system diagnosis, the term medical screening has come to refer to the process of screening for referral. The process involves determining whether the individual has a condition that can be addressed by the physical therapist’s intervention and if not, then whether the condition requires evaluation by a medical doctor or other medical specialist.

Both terms (medical screening and screening for referral) will probably continue to be used interchangeably to describe the screening process. It may be important to keep the distinction in mind, especially when conversing/consulting with physicians whose concept of medical screening differs from the physical therapist’s use of the term to describe screening for referral.

Diagnosis by the Physical Therapist

The term “diagnosis by the physical therapist” is language used by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). It is the policy of the APTA that physical therapists shall establish a diagnosis for each patient/client. Prior to making a patient/client management decision, physical therapists shall utilize the diagnostic process in order to establish a diagnosis for the specific conditions in need of the physical therapist’s attention.20

In keeping with advancing physical therapist practice, the current education strategic plan and Vision 2020, Diagnosis by Physical Therapists (HOD P06-97-06-19), has been updated to include ordering of tests that are performed and interpreted by other health professionals (e.g., radiographic imaging, laboratory blood work). The position now states that it is the physical therapist’s responsibility in the diagnostic process to organize and interpret all relevant data.21

The diagnostic process requires evaluation of information obtained from the patient/client examination, including the history, systems review, administration of tests, and interpretation of data. Physical therapists use diagnostic labels that identify the impact of a condition on function at the level of the system (especially the human movement system) and the level of the whole person.22

The physical therapist is qualified to make a diagnosis regarding primary NMS conditions, though we must do so in accordance with the state practice act. The profession must continue to develop the concept of human movement as a physiologic system and work to get physical therapists recognized as experts in that system.23

Further Defining Diagnosis

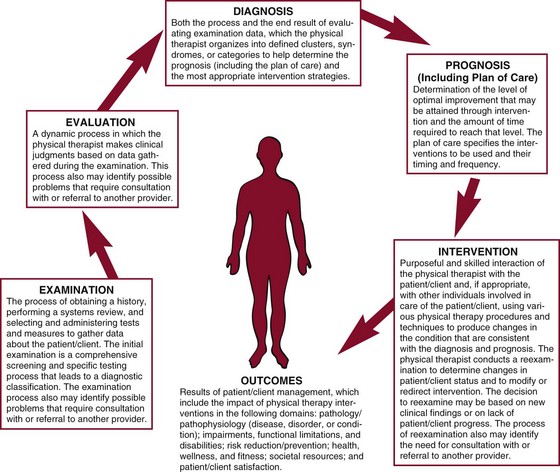

Whenever diagnosis is discussed, we hear this familiar refrain: diagnosis is both the process and the end result of evaluating examination data, which the therapist organizes into defined clusters, syndromes, or categories to help determine the prognosis and the most appropriate intervention strategies.1

It has been described as the decision reached as a result of the diagnostic process, which is the evaluation of information obtained from the patient/client examination.20 Whereas the physician makes a medical diagnosis based on the pathologic or pathophysiologic state at the cellular level, in a diagnosis-based physical therapist’s practice, the therapist places an emphasis on the identification of specific human movement impairments that best establish effective interventions and reliable prognoses.24

Others have supported a revised definition of the physical therapy diagnosis as: a process centered on the evaluation of multiple levels of movement dysfunction whose purpose is to inform treatment decisions related to functional restoration.25 According to the Guide, the diagnostic-based practice requires the physical therapist to integrate five elements of patient/client management (Box 1-5) in a manner designed to maximize outcomes (Fig. 1-4).

Fig. 1-4 The elements of patient/client management leading to optimal outcomes. Screening takes place anywhere along this pathway. (Reprinted with permission from Guide to physical therapist practice, ed 2 [Revised], 2003, Fig. 1-4, p. 35.)

One of those proposed modifications is in the Elements of Patient/Client Management offered by the APTA in the Guide. Fig. 1-4 does not illustrate all decisions possible.

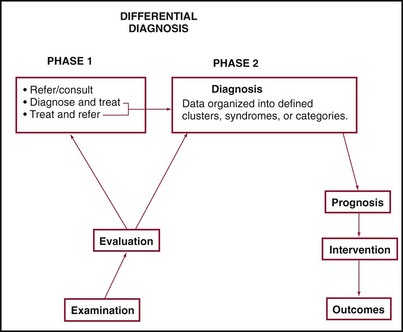

Boissonnault proposed a fork in the clinical decision-making pathway to show three alternative decisions6,26 (Fig. 1-5), including

Fig. 1-5 Modification to the patient/client management model. On the left side of this figure, the therapist starts by collecting data during the examination. Based on the data collected, the evaluation leads to clinical judgments. The current model in the Guide gives only one decision-making option and that is the diagnosis. In this adapted model, a fork in the decision-making pathway allows the therapist the opportunity to make one of three alternative decisions as described in the text. This model is more in keeping with recommended clinical practice. (From Boissonnault WG, Umphred DA: Differential diagnosis phase I. In Umphred DA, editors: Neurological rehabilitation, ed 6, St. Louis, 2012, Mosby.)

1. Referral/consultation (no treatment; referral may be a nonurgent consult or an immediate/urgent referral)

The decision to refer or consult with the physician can also apply to referral to other appropriate health care professionals and/or practitioners (e.g., dentist, chiropractor, nurse practitioner, psychologist).

In summary, there has been considerable discussion that evaluation is a process with diagnosis as the end result.27 The concepts around the “diagnostic process” remain part of an evolving definition that will continue to be discussed and clarified by physical therapists. We will present some additional pieces to the discussion as we go along in this chapter.

APTA Vision Sentence for Physical Therapy 2020

By 2020, physical therapy will be provided by physical therapists who are doctors of physical therapy, recognized by consumers and other health care professionals as the practitioners of choice to whom consumers have direct access for the diagnosis of, interventions for, and prevention of impairments, functional limitations, and disabilities related to movement, function, and health.28

The vision sentence points out that physical therapists are capable of making a diagnosis and determining whether the patient/client can be helped by physical therapy intervention. In an autonomous profession the therapist can decide if physical therapy should be a part of the plan, the entire plan, or not needed at all.

When communicating with physicians, it is helpful to understand the definition of a medical diagnosis and how it differs from a physical therapist’s diagnosis. The medical diagnosis is traditionally defined as the recognition of disease.

It is the determination of the cause and nature of pathologic conditions. Medical differential diagnosis is the comparison of symptoms of similar diseases and medical diagnostics (laboratory and test procedures performed) so that a correct assessment of the patient/client’s actual problem can be made.

A differential diagnosis by the physical therapist is the comparison of NMS signs and symptoms to identify the underlying human movement dysfunction so that treatment can be planned as specifically as possible. If there is evidence of a pathologic condition, referral is made to the appropriate health care (or other) professional. This step requires the therapist to at least consider the possible pathologic conditions, even if unable to verify the presence or absence of said condition.29

One of the APTA goals is that physical therapists will be universally recognized and promoted as the practitioners of choice for persons with conditions that affect human movement, function, health, and wellness.30

Purpose of the Diagnosis

In the context of screening for referral, the purpose of the diagnosis is to:

• Treat as specifically as possible by determining the most appropriate plan of care and intervention strategy for each patient/client

More broadly stated the purpose of the human movement system diagnosis is to guide the physical therapist in determining the most appropriate intervention strategy for each patient/client with a goal of decreasing disability and increasing function. In the event the diagnostic process does not yield an identifiable cluster, disorder, syndrome, or category, intervention may be directed toward the alleviation of symptoms and remediation of impairment, functional limitation, or disability.20

Sometimes the patient/client is too acute to examine fully on the first visit. At other times, we evaluate nonspecific referral diagnoses such as problems medically diagnosed as “shoulder pain” or “back pain.” When the patient/client is referred with a previously established diagnosis, the physical therapist determines that the clinical findings are consistent with that diagnosis20 (Case Example 1-5).

Sometimes the screening and diagnostic process identifies a systemic problem as the underlying cause of NMS symptoms. At other times, it confirms that the patient/client has a human movement system syndrome or problem after all (see Case Examples 1-531 and 1-7).

Historical Perspective

The idea of “physical therapy diagnosis” is not a new one. In fact, from its earliest beginnings until now, it has officially been around for at least 20 years. It was first described in the literature by Shirley Sahrmann32 as the name given to a collection of relevant signs and symptoms associated with the primary dysfunction toward which the physical therapist directs treatment. The dysfunction is identified by the physical therapist based on the information obtained from the history, signs, symptoms, examination, and tests the therapist performs or requests.

In 1984, the APTA House of Delegates (HOD) made a motion that the physical therapist may establish a diagnosis within the scope of their knowledge, experience, and expertise. This was further qualified in 1990 when the Education Standards for Accreditation described “Diagnosis” for the first time.

In 1990, teaching and learning content and the skills necessary to determine a diagnosis became a required part of the curriculum standards established then by the Standards for Accreditation for Physical Therapist Educational Program. At that time the therapist’s role in developing a diagnosis was described as:

• Engage in the diagnostic process in an efficient manner consistent with the policies and procedures of the practice setting.

• Engage in the diagnostic process to establish differential diagnoses for patient/clients across the lifespan based on evaluation of results of examinations and medical and psychosocial information.

• Take responsibility for communication or discussion of diagnoses or clinical impressions with other practitioners.

In 1995, the HOD amended the 1984 policy to make the definition of diagnosis consistent with the then upcoming Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. The first edition of the Guide was published in 1997. It was revised and published as a second edition in 2001; the second edition was revised in 2003.

Classification System

According to Rothstein,33 in many fields of medicine when a medical diagnosis is made, the pathologic condition is determined and stages and classifications that guide treatment are also named. Although we recognize that the term diagnosis relates to a pathologic process, we know that pathologic evidence alone is inadequate to guide the physical therapist.

Physical therapists do not diagnose disease in the sense of identifying a specific organic or visceral pathologic condition. However, identified clusters of signs, symptoms, symptom-related behavior, and other data from the patient/client history and other testing can be used to confirm or rule out the presence of a problem within the scope of the physical therapist’s practice. These diagnostic clusters can be labeled as impairment classifications or human movement dysfunctions by physical therapists and can guide efficient and effective management of the client.34

Although not diagnostic labels, the Guide groups the preferred practice patterns into four categories of conditions that can be used to guide the examination, evaluation, and intervention. These include musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, cardiovascular/pulmonary, and integumentary categories. An individual may belong to one or more of these groups or patterns.

Diagnostic classification systems that direct treatment interventions are being developed based on client prognosis and definable outcomes demonstrated in the literature.1,35 At the same time, efforts are being made and ongoing discussions are taking place to define diagnostic categories or diagnostic descriptors for the physical therapist.36-40 There is also a trend toward identification of subgroups within a particular group of individuals (e.g., low back pain, shoulder dysfunction) and predictive factors (positive and negative) for treatment and prognosis.

Diagnosis Dialog

Since 2006, a group of physical therapists across the United States have been meeting to define diagnosis, the purpose of diagnoses, and developing a template for universal use for all physical therapists to use in making a diagnosis. In keeping with our expertise in the human movement system, it has been suggested that the primary focus of the physical therapist’s diagnostic expertise should be on diagnosing syndromes of the human movement system.41 To see more about this group and the work being done, go to http://dxdialog.wusm.wustl.edu.

Earlier in this text discussion, we attempted to summarize various opinions and thoughts presented in our literature defining diagnosis. Here is an added component to that discussion. The “working” definition of diagnosis put forth by the Diagnosis Dialog group is:

Diagnosis is both a process and a descriptor. The diagnostic process includes integrating and evaluating the data that are obtained during the examination for the purpose of guiding the prognosis, the plan of care, and intervention strategies. Physical therapists assign diagnostic descriptors that identify a condition or syndrome at the level of the system, especially the human movement system, and at the level of the whole person.41

In keeping with the APTA’s Vision 2020 establishing our professional identity with the movement system, the human movement system has become the focus of the physical therapist’s “diagnosis.” The suggested template for this diagnosis under discussion and development is currently as follows41:

Differential Diagnosis Versus Screening

If you are already familiar with the term differential diagnosis, you may be wondering about the change in title for this text. Previous editions were entitled Differential Diagnosis in Physical Therapy.

The new name Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral, first established for the fourth edition of this text, does not reflect a change in the content of the text as much as it reflects a better understanding of the screening process and a more appropriate use of the term “differential diagnosis” to identify and describe the specific movement impairment present (if there is one).

When the first edition of this text was published, the term “physical therapy diagnosis” was not yet commonly used nomenclature. Diagnostic labels were primarily within the domain of the physician. Over the years, as our profession has changed and progressed, the concept of diagnosis has evolved.

A diagnosis by the physical therapist as outlined in the Guide describes the patient/client’s primary dysfunction(s). This can be done through the classification of a patient/client within a specific practice pattern. The diagnostic process begins with the collection of data (examination), proceeds through the organization and interpretation of data (evaluation), and ends in the application of a label (i.e., the diagnosis).1

As part of the examination process, the therapist may conduct a screening examination. This is especially true if the diagnostic process does not yield an identifiable movement dysfunction. Throughout the evaluation process, the therapist must ask himself or herself:

• Is this an appropriate physical referral?

• Is there a problem that falls into one of the four categories of conditions described in the Guide?

• Is there a history or cluster of signs and/or symptoms that raises a yellow (cautionary) or red (warning) flag?

The presence of risk factors and yellow or red flags alerts the therapist to the need for a screening examination. Once the screening process is complete and the therapist has confirmed the client is appropriate for physical therapy intervention, then the objective examination continues.

Sometimes in the early presentation, there are no red flags or associated signs and symptoms to suggest an underlying systemic or viscerogenic cause of the client’s NMS symptoms or movement dysfunction.

It is not until the disease progresses that the clinical picture changes enough to raise a red flag. This is why the screening process is not necessarily a one-time evaluation. Screening can take place anywhere along the circle represented in Fig. 1-4.

The most likely place screening occurs is during the examination when the therapist obtains the history, performs a systems review, and carries out specific tests and measures. It is here that the client reports constant pain, skin lesions, gastrointestinal problems associated with back pain, digital clubbing, palmar erythema, shoulder pain with stair climbing, or any of the many indicators of systemic disease.

The therapist may hear the client relate new onset of symptoms that were not present during the examination. Such new information may come forth anytime during the episode of care. If the patient/client does not progress in physical therapy or presents with new onset of symptoms unreported before, the screening process may have to be repeated.

Red-flag signs and symptoms may appear for the first time or develop more fully during the course of physical therapy intervention. In some cases, exercise stresses the client’s physiology enough to tip the scales. Previously unnoticed, unrecognized, or silent symptoms suddenly present more clearly.

As mentioned, a lack of progress signals the need to conduct a reexamination or to modify/redirect intervention. The process of reexamination may identify the need for consultation with or referral to another health care provider (Guide,1 Figure 1: Intervention, p. 43). The medical doctor is the most likely referral recommendation, but referral to a nurse practitioner, physician assistant, chiropractor, dentist, psychologist, counselor, or other appropriate health care professional may be more appropriate at times.

Scope of Practice

A key phrase in the APTA standards of practice is “within the scope of physical therapist practice.” Establishing a diagnosis is a professional standard within the scope of a physical therapist practice but may not be permitted according to the therapist’s state practice act (Case Example 1-6).

As we have pointed out repeatedly, an organic problem can masquerade as a mechanical or movement dysfunction. Identification of causative factors or etiology by the physical therapist is important in the screening process. By remaining within the scope of our practice the diagnosis is limited primarily to those pathokinesiologic problems associated with faulty biomechanical or neuromuscular action.

When no apparent movement dysfunction, causative factors, or syndrome can be identified, the therapist may treat symptoms as part of an ongoing diagnostic process. Sometimes even physicians use physical therapy as a diagnostic tool, observing the client’s response during the episode of care to confirm or rule out medical suspicions.

If, however, the findings remain inconsistent with what is expected for the human movement system and/or the patient/client does not improve with intervention,16,42 then referral to an appropriate medical professional may be required. Always keep in mind that the screening process may, in fact, confirm the presence of a musculoskeletal or neuromuscular problem.

The flip side of this concept is that client complaints that cannot be associated with a medical problem should be referred to a physical therapist to identify mechanical problems (Case Example 1-7). Physical therapists have a responsibility to educate the medical community as to the scope of our practice and our role in identifying mechanical problems and movement disorders.

Staying within the scope of physical therapist practice, the therapist communicates with physicians and other health care practitioners to request or recommend further medical evaluation. Whether in a private practice, school or home health setting, acute care hospital, or rehabilitation setting, physical therapists may observe and report important findings outside the realm of NMS disorders that require additional medical evaluation and treatment.

Direct Access and Self-Referral

Direct access and self-referral is the legal right of the public to obtain examination, evaluation, and intervention from a licensed physical therapist without previous examination by, or referral from, a physician, gatekeeper, or other practitioner. In the civilian sector, the need to screen for medical disease was first raised as an issue in response to direct-access legislation. Until direct access, the only therapists screening for referral were the military physical therapists.

Before 1957 a physician referral was necessary in all 50 states for a client to be treated by a physical therapist. Direct access was first obtained in Nebraska in 1957, when that state passed a licensure and scope-of-practice law that did not mandate a physician referral for a physical therapist to initiate care.43

One of the goals of the APTA as outlined in the APTA 2020 vision statement is to achieve direct access to physical therapy services for citizens of all 50 states by the year 2020. At the present time, all but a handful of states in the United States permit some form of direct access and self-referral to allow patient/clients to consult a physical therapist without first being referred by a physician, dentist, or chiropractor. Direct access is relevant in all practice settings and is not limited just to private practice or outpatient services.

It is possible to have a state direct-access law but a state practice act that forbids therapists from seeing Medicare clients without a referral. A therapist in that state can see privately insured clients without a referral, but not Medicare clients. Passage of the Medicare Patient/Client Access to Physical Therapists Act (PAPTA) will extend direct access nationwide to all Medicare Part B beneficiaries who require outpatient physical therapy services, in states where direct access is authorized without a physician’s referral or certification of the plan of care.

Full, unrestricted direct access is not available in all states with a direct-access law. Various forms of direct access are available on a state-by-state basis. Many direct-access laws are permissive, as opposed to mandatory. This means that consumers are permitted to see therapists without a physician’s referral; however, a payer can still require a referral before providing reimbursement for services. Each therapist must be familiar with the practice act and direct-access legislation for the state in which he or she is practicing.

Sometimes states enact a two- or three-tiered restricted or provisional direct-access system. For example, some states’ direct-access law only allows evaluation and treatment for therapists who have practiced for 3 years. Some direct-access laws only allow physical therapists to provide services for up to 14 days without physician referral. Other states list up to 30 days as the standard.

There may be additional criteria in place, such as the patient/client must have been referred to physical therapy by a physician within the past 2 years or the therapist must notify the patient/client’s identified primary care practitioner no later than 3 days after intervention begins.

Some states require a minimum level of liability insurance coverage by each therapist. In a three tiered–direct access state, three or more requirements must be met before practicing without a physician referral. For example, licensed physical therapists must practice for a specified number of years, complete continuing education courses, and obtain references from two or more physicians before treating clients without a physician referral.

There are other factors that prevent therapists from practicing under full direct-access rights even when granted by state law. For example, Boissonnault44 presents regulatory barriers and internal institutional policies that interfere with the direct access practice model.

In the private sector, some therapists think that the way to avoid malpractice lawsuits is to continue operating under a system of physician referral. Therapists in a private practice driven by physician referral may not want to be placed in a position as competitors of the physicians who serve as a referral source.

Internationally, direct access has become a reality in some, but not all, countries. It has been established in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Direct access is not uniformly defined, implemented, or reimbursed from country to country.45

Primary Care

Primary care is the coordinated, comprehensive, and personal care provided on a first-contact and continuous basis. It incorporates primary and secondary prevention of chronic disease states, wellness, personal support, education (including providing information about illness, prevention, and health maintenance), and addresses the personal health care needs of patient/clients within the context of family and community.25 Primary care is not defined by who provides it but rather it is a set of functions as described. It is person- (not disease- or diagnosis-) focused care over time.46

In the primary care delivery model, the therapist is responsible as a patient/client advocate to see that the patient/client’s NMS and other health care needs are identified and prioritized, and a plan of care is established. The primary care model provides the consumer with first point-of-entry access to the physical therapist as the most skilled practitioner for human movement system dysfunction. The physical therapist may also serve as a key member of a multidisciplinary primary care team that works together to assist the patient/client in maintaining his or her overall health and fitness.

Through a process of screening, triage, examination, evaluation, referral, intervention, coordination of care, education, and prevention, the therapist prevents, reduces, slows, or remediates impairments, functional limitations, and disabilities while achieving cost-effective clinical outcomes.1,47

Expanded privileges beyond the traditional scope of the physical therapist practice may become part of the standard future physical therapist primary care practice. In addition to the usual privileges included in the scope of the physical therapist practice, the primary care therapist may eventually refer patient/clients to radiology for diagnostic imaging and other diagnostic evaluations. In some settings (e.g., U.S. military), the therapist is already doing this and is credentialed to prescribe analgesic and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications.48

Direct Access Versus Primary Care

Direct access is the vehicle by which the patient/client comes directly to the physical therapist without first seeing a physician, dentist, chiropractor, or other health care professional. Direct access does not describe the type of practice the therapist is engaging in.

Primary care physical therapy is not a setting but rather describes a philosophy of whole-person care. The therapist is the first point-of-entry into the health care system. After screening and triage, patient/clients who do not have NMS conditions are referred to the appropriate health care specialist for further evaluation.

The primary care therapist is not expected to diagnose conditions that are not neuromuscular or musculoskeletal. However, risk factor assessment and screening for a broad range of medical conditions (e.g., high blood pressure, incontinence, diabetes, vestibular dysfunction, peripheral vascular disease) is possible and an important part of primary and secondary prevention.

Autonomous Practice

Autonomous physical therapist practice is the centerpiece of the APTA Vision 2020 statement.49 It is defined as “self-governing;” “not controlled (or owned) by others.”50 Autonomous practice is described as independent, self-determining professional judgment and action.51 Autonomous practice for the physical therapist does not mean practice independent of collaborative and collegial communication with other health care team members (Box 1-6) but rather, interdependent evidence-based practice that is patient- (client-) centered care. Professional autonomy meets the health needs of people who are experiencing disablement by providing a service that supports the autonomy of that individual.49

Five key objectives set forth by the APTA in achieving an autonomous physical therapist practice include (1) demonstrating professionalism, (2) achieving direct access to physical therapist services, (3) basing practice on the most up-to-date evidence, (4) providing an entry-level education at the level of Doctor of Physical Therapy, and (5) becoming the practitioner of choice.51

APTA Vision Statement for Physical Therapy 2020

Physical therapy, by 2020, will be provided by physical therapists who are doctors of physical therapy and who may be board-certified specialists. Consumers will have direct access to physical therapists in all environments for patient/client management, prevention, and wellness services.

Physical therapists will be practitioners of choice in patient/clients’ health networks and will hold all privileges of autonomous practice. Physical therapists may be assisted by physical therapist assistants who are educated and licensed to provide physical therapist–directed and supervised components of interventions.28

Self-determination means the privilege of making one’s own decisions, but only after key information has been obtained through examination, history, and consultation. The autonomous practitioner independently makes professional decisions based on a distinct or unique body of knowledge. For the physical therapist, that professional expertise is confined to the examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention of human movement system impairments.

Physical therapists have the capability, ability, and responsibility to exercise professional judgment within their scope of practice. In this context, the therapist must conduct a thorough examination, determine a diagnosis, and recognize when physical therapy is inappropriate, or when physical therapy is appropriate, but the client’s condition is beyond the therapist’s training, experience, or expertise. In such a case, referral is required, but referral may be to a qualified physical therapist who specializes in treating such disorders or conditions.52,53

Reimbursement Trends

Despite research findings that episodes of care for patient/clients who received physical therapy via direct access were shorter, included fewer numbers of services, and were less costly than episodes of care initiated through physician referral,54 many payers, hospitals, and other institutions still require physician referral.44,55

Direct-access laws give consumers the legal right to seek physical therapy services without a medical referral. These laws do not always make it mandatory that insurance companies, third-party payers (including Medicare/Medicaid), self-insured, or other insurers reimburse the physical therapist without a physician’s prescription.

Some state home-health agency license laws require referral for all client care regardless of the payer source. In the future, we hope to see all insurance companies reimburse for direct access without further restriction. Further legislation and regulation are needed in many states to amend the insurance statutes and state agency policies to assure statutory compliance.

This policy, along with large deductibles, poor reimbursement, and failure to authorize needed services has resulted in a trend toward a cash-based, private-pay business. This trend in reimbursement is also referred to as direct contracting, first-party payment, direct consumer services, or direct fee-for-service.56 In such an environment, decisions can be made based on the good of the clients rather than on cost or volume.

In such circumstances, consumers are willing to pay out-of-pocket for physical therapy services, bypassing the need for a medical evaluation unless requested by the physical therapist. A therapist can use a cash-based practice only where direct access has been passed and within the legal parameters of the state practice act.

In any situation where authorization for further intervention by a therapist is not obtained despite the therapist’s assessment that further skilled services are needed, the therapist can notify the client and/or the family of their right to an appeal with the agency providing health care coverage.

The client has the right to make informed decisions regarding pursuit of insurance coverage or to make private-pay arrangements. Too many times the insurance coverage ends, but the client’s needs have not been met. Creative planning and alternate financial arrangements should remain an option discussed and made available.

Decision-Making Process

This text is designed to help students, physical therapist assistants, and physical therapy clinicians screen for medical disease when it is appropriate to do so. But just exactly how is this done? The proposed Goodman screening model can be used in conducting a screening evaluation for any client (Box 1-7).

By using these decision-making tools, the therapist will be able to identify chief and secondary problems, identify information that is inconsistent with the presenting complaint, identify noncontributory information, generate a working hypothesis regarding possible causes of complaints, and determine whether referral or consultation is indicated.

The screening process is carried out through the client interview and verified during the physical examination. Therapists compare the subjective information (what the client tells us) with the objective findings (what we find during the examination) to identify movement impairment or other neuromuscular or musculoskeletal dysfunction (that which is within the scope of our practice) and to rule out systemic involvement (requiring medical referral). This is the basis for the evaluation process.

Given today’s time constraints in the clinic, a fast and efficient method of screening is essential. Checklists (see Appendix A-1), special questions to ask (see companion website; see also Appendix B), and the screening model outlined in Box 1-7 can guide and streamline the screening process. Once the clinician is familiar with the use of this model, it is possible to conduct the initial screening exam in 3 to 5 minutes when necessary. This can include (but is not limited to) the following:

• Use the word “symptom(s)” rather than “pain” during the screening interview

• Watch for red flag histories, signs, and symptoms

• Review medications; observe for signs and symptoms that could be a result of drug combinations (polypharmacy), dual drug dosage; consult with the pharmacist

If a young, healthy athlete comes in with a sprained ankle and no other associated signs and symptoms, there may be no need to screen further. But if that same athlete has an eating disorder, uses anabolic steroids illegally, or is on antidepressants, the clinical picture (and possibly the intervention) changes. Risk factor assessment and a screening physical examination are the most likely ways to screen more thoroughly.

Or take, for example, an older adult who presents with hip pain of unknown cause. There are two red flags already present (age and insidious onset). As clients age, the past medical history and risk factor assessment become more important assessment tools. After investigating the clinical presentation, screening would focus on these two elements next.

Or, if after ending the interview by asking, “Are there any symptoms of any kind anywhere else in your body that we have not talked about yet?” the client responds with a list of additional symptoms, it may be best to step back and conduct a Review of Systems.

Past Medical History

Most of history taking is accomplished through the client interview and includes both family and personal history. The client/patient interview is very important because it helps the physical therapist distinguish between problems that he or she can treat and problems that should be referred to a physician (or other appropriate health care professional) for medical diagnosis and intervention.

In fact, the importance of history taking cannot be emphasized enough. Physicians cite a shortage of time as the most common reason to skip the client history, yet history taking is the essential key to a correct diagnosis by the physician (or physical therapist).57,58 At least one source recommends performing a history and differential diagnosis followed by relevant examination.58

In Chapter 2, an interviewing process is described that includes concrete and structured tools and techniques for conducting a thorough and informative interview. The use of follow-up questions (FUPs) helps complete the interview. This information establishes a solid basis for the therapist’s objective evaluation, assessment, and therefore intervention.

During the screening interview it is always a good idea to use a standard form to complete the personal/family history (see Fig. 2-2). Any form of checklist assures a thorough and consistent approach and spares the therapist from relying on his or her memory.

The types of data generated from a client history are presented in Fig. 2-1. Most often, age, race/ethnicity, gender, and occupation (general demographics) are noted. Information about social history, living environment, health status, functional status, and activity level is often important to the patient/client’s clinical presentation and outcomes. Details about the current condition, medical (or other) intervention for the condition, and use of medications is also gathered and considered in the overall evaluation process.

The presence of any yellow or red flags elicited during the screening interview or observed during the physical examination should prompt the therapist to consider the need for further tests and questions. Many of these signs and symptoms are listed in Appendix A-2.

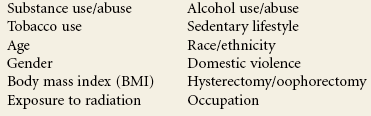

Psychosocial history may provide insight into the client’s clinical presentation and overall needs. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, occupation, family system, health habits, living environment, medication use, and medical/surgical history are all part of the client history evaluated in the screening process.

Risk Factor Assessment

Greater emphasis has been placed on risk factor assessment in the health care industry recently. Risk factor assessment is an important part of disease prevention. Knowing the various risk factors for different kinds of diseases, illnesses, and conditions is an important part of the screening process.

Therapists can have an active role in both primary and secondary prevention through screening and education. According to the Guide,1 physical therapists are involved in primary prevention by preventing a target condition in a susceptible or potentially susceptible population through such specific measures as general health promotion efforts.

Educating clients about their risk factors is a key element in risk factor reduction. Identifying risk factors may guide the therapist in making a medical referral sooner than would otherwise seem necessary.

In primary care, the therapist assesses risk factors, performs screening exams, and establishes interventions to prevent impairment, dysfunction, and disability. For example, does the client have risk factors for osteoporosis, urinary incontinence, cancer, vestibular or balance problems, obesity, cardiovascular disease, and so on? The physical therapist practice can include routine screening for any of these, as well as other problems.

More and more evidence-based clinical prediction rules for specific conditions (e.g., deep venous thrombosis) are available and included in this text; research is needed to catch up in the area of clinical prediction rules and identification of specificity and sensitivity of specific red flags and screening tests currently being presented in this text and used in clinical practice. Prediction models based on risk that would improve outcomes may eventually be developed for many diseases, illnesses, and conditions currently screened by red flags and clinical findings.59,60

Eventually, genetic screening may augment or even replace risk factor assessment. Virtually every human illness is believed to have a hereditary component. The most common problems seen in a physical therapist practice (outside of traumatic injuries) are now thought to have a genetic component, even though the specific gene may not yet be discovered for all conditions, diseases, or illnesses.61

Exercise as a successful intervention for many diseases, illness, and conditions will become prescriptive as research shows how much and what kind of exercise can prevent or mediate each problem. There is already a great deal of information on this topic published, and an accompanying need to change the way people think about exercise.62

Convincing people to establish lifelong patterns of exercise and physical activity will continue to be a major focus of the health care industry. Therapists can advocate disease prevention, wellness, and promotion of healthy lifestyles by delivering health care services intended to prevent health problems or maintain health and by offering annual wellness screening as part of primary prevention.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation, including pain patterns and pain types, is the next part of the decision-making process. To assist the physical therapist in making a treatment-versus-referral decision, specific pain patterns corresponding to systemic diseases are provided in Chapter 3. Drawings of primary and referred pain patterns are provided in each chapter for quick reference. A summary of key findings associated with systemic illness is listed in Box 1-2.

The presence of any one of these variables is not cause for extreme concern but should raise a yellow or red flag for the alert therapist. The therapist is looking for a pattern that suggests a viscerogenic or systemic origin of pain and/or symptoms. This pattern will not be consistent with what we might expect to see with the neuromuscular or musculoskeletal systems.

The therapist will proceed with the screening process, depending on all findings. Often the next step is to look for associated signs and symptoms. Special follow-up questions (FUPs) are listed in the subjective examination to help the physical therapist determine when these pain patterns are accompanied by associated signs and symptoms that indicate visceral involvement.

Associated Signs and Symptoms of Systemic Diseases

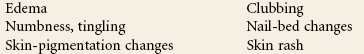

The major focus of this text is the recognition of yellow- or red-flag signs and symptoms either reported by the client subjectively or observed objectively by the physical therapist.

Signs are observable findings detected by the therapist in an objective examination (e.g., unusual skin color, clubbing of the fingers [swelling of the terminal phalanges of the fingers or toes], hematoma [local collection of blood], effusion [fluid]). Signs can be seen, heard, smelled, measured, photographed, shown to someone else, or documented in some other way.

Symptoms are reported indications of disease that are perceived by the client but cannot be observed by someone else. Pain, discomfort, or other complaints, such as numbness, tingling, or “creeping” sensations, are symptoms that are difficult to quantify but are most often reported as the chief complaint.

Because physical therapists spend a considerable amount of time investigating pain, it is easy to remain focused exclusively on this symptom when clients might otherwise bring to the forefront other important problems.

Thus the physical therapist is encouraged to become accustomed to using the word symptoms instead of pain when interviewing the client. It is likewise prudent for the physical therapist to refer to symptoms when talking to clients with chronic pain in order to move the focus away from pain.

Instead of asking the client, “How are you today?” try asking:

This approach to questioning progress (or lack of progress) may help you see a systemic pattern sooner than later.

The therapist can identify the presence of associated signs and symptoms by asking the client:

The patient/client may not see a connection between shoulder pain and blood in the urine from kidney impairment or blood in the stools from chronic nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use. Likewise the patient/client may not think the diarrhea present is associated with the back pain (gastrointestinal [GI] dysfunction).

The client with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain from a cardiac source usually has some other associated symptoms, and in most cases, the client does not see the link. If the therapist does not ask, the client does not offer the extra information.

Each visceral system has a typical set of core signs and symptoms associated with impairment of that system (see Box 4-19). Systemic signs and symptoms that are listed for each condition should serve as a warning to alert the informed physical therapist of the need for further questioning and possible medical referral.

For example, the most common symptoms present with pulmonary pathology are cough, shortness of breath, and pleural pain. Liver impairment is marked by abdominal ascites, right upper quadrant tenderness, jaundice, and skin and nailbed changes. Signs and symptoms associated with endocrine pathology may include changes in body or skin temperature, dry mouth, dizziness, weight change, or excessive sweating.

Being aware of signs and symptoms associated with each individual system may help the therapist make an early connection between viscerogenic and/or systemic presentation of NMS problems. The presence of constitutional symptoms is always a red flag that must be evaluated carefully (see Box 1-3).

Systems Review Versus Review of Systems

The Systems Review is defined in the Guide as a brief or limited exam of the anatomic and physiologic status of the cardiovascular/pulmonary, integumentary, musculoskeletal, and neuromuscular systems. The Systems Review also includes assessment of the client’s communication ability, affect, cognition, language, and learning style.

The specific tests and measures for this type of Systems Review are outlined in the Guide1 (Appendix 5, Guidelines for Physical Therapy Documentation, pp. 695-696). As part of this Systems Review, the client’s ability to communicate, process information, and any barriers to learning are identified.

The Systems Review looks beyond the primary problem that brought the client to the therapist in the first place. It gives an overview of the “whole person,” and guides the therapist in choosing appropriate tests and measures. The Systems Review helps the therapist answer the questions, “What should I do next?” and “What do I need to examine in depth?” It also answers the question, “What don’t I need to do?”63

In the screening process, a slightly different approach may be needed, perhaps best referred to as a Review of Systems. After conducting an interview, performing an assessment of the pain type and/or pain patterns, and reviewing the clinical presentation, the therapist looks for any characteristics of systemic disease. Any identified clusters of associated signs and symptoms are reviewed to search for a potential pattern that will identify the underlying system involved.

The Review of Systems as part of the screening process (see discussion, Chapter 4) is a useful tool in recognizing clusters of associated signs and symptoms and the possible need for medical referral. Using this final tool, the therapist steps back and looks at the big picture, taking into consideration all of the presenting factors, and looking for any indication that the client’s problem is outside the scope of a physical therapist’s practice.

The therapist conducts a Review of Systems in the screening process by categorizing all of the complaints and associated signs and symptoms. Once these are listed, compare this list to Box 4-19. Are the signs and symptoms all genitourinary (GU) related? GI in nature?

Perhaps the therapist observes dry skin, brittle nails, cold or heat intolerance, or excessive hair loss and realizes these signs could be pointing to an endocrine problem. At the very least the therapist recognizes that the clinical presentation is not something within the musculoskeletal or neuromuscular systems.

If, for example, the client’s signs and symptoms fall primarily within the GU group, turn to Chapter 10 and use the additional, pertinent screening questions at the end of the chapter. The client’s answers to these questions will guide the therapist in making a decision about referral to a physician or other health care professional.

The physical therapist is not responsible for identifying the specific systemic or visceral disease underlying the clinical signs and symptoms present. However, the alert therapist who classifies groups of signs and symptoms in a Review of Systems will be more likely to recognize a problem outside the scope of physical therapy practice and make a timely referral.

As a final note in this discussion of Systems Review versus Review of Systems, there is some consideration being given to possibly changing the terminology in the Guide to reflect the full measure of these concepts, but no definitive decision had been made by the time this text went to press. The concept will be discussed, and any decision made will go through both an expert and wide review process. Results will be reflected in future editions of this text.

Case Examples and Case Studies

Case examples and case studies are provided with each chapter to give the therapist a working understanding of how to recognize the need for additional questions. In addition, information is given concerning the type of questions to ask and how to correlate the results with the objective findings.

Cases will be used to integrate screening information in making a physical therapy differential diagnosis and deciding when and how to refer to the physician or other health care professional. Whenever possible, information about when and how to refer a client to the physician is presented.

Each case study is based on actual clinical experiences in a variety of inpatient/client and outpatient/client physical therapy practices to provide reasonable examples of what to expect when the physical therapist is functioning under any of the circumstances listed in Box 1-1.

Physician Referral

As previously mentioned, the therapist may treat symptoms as part of an ongoing medical diagnostic process. In other words, sometimes the physician sends a patient/client to physical therapy “to see if it will help.” This may be part of the medical differential diagnosis. Medical consultation or referral is required when no apparent movement dysfunction, causative factors, or syndrome can be identified and/or the findings are not consistent with a NMS dysfunction.

Communication with the physician is a key component in the referral process. Phone, email, and fax make this process faster and easier than ever before. Persistence may be required in obtaining enough information to glean what the doctor knows or thinks to avoid sending the very same problem back for his/her consideration. This is especially important when the physician is using physical therapy intervention as part of the medical differential diagnostic process.

The hallmark of professionalism in any health care practitioner is the ability to understand the limits of his or her professional knowledge. The physical therapist, either on reaching the limit of his or her knowledge or on reaching the limits prescribed by the client’s condition, should refer the patient/client to the appropriate personnel. In this way, the physical therapist will work within the scope of his or her level of skill, knowledge, and practical experience.

Knowing when and how to refer a client to another health care professional is just as important as the initial screening process. Once the therapist recognizes red flag histories, risk factors, signs and symptoms, and/or a clinical presentation that do not fit the expected picture for NMS dysfunction, then this information must be communicated effectively to the appropriate referral source.

Knowing how to refer the client or how to notify the physician of important findings is not always clear. In a direct access or primary care setting, the client may not have a personal or family physician. In an orthopedic setting, the client in rehab for a total hip or total knee replacement may be reporting signs and symptoms of a nonorthopedic condition. Do you send the client back to the referring (orthopedic) physician or refer him or her to the primary care physician?

Suggested Guidelines

When the client has come to physical therapy without a medical referral (i.e., self-referred) and the physical therapist recommends medical follow-up, the patient/client should be referred to the primary care physician if the patient/client has one.

Occasionally, the patient/client indicates that he or she has not contacted a physician or was treated by a physician (whose name cannot be recalled) a long time ago or that he or she has just moved to the area and does not have a physician.

In these situations the client can be provided with a list of recommended physicians. It is not necessary to list every physician in the area, but the physical therapist can provide several appropriate choices. Whether the client makes or does not make an appointment with a medical practitioner, the physical therapist is urged to document subjective and objective findings carefully, as well as the recommendation made for medical follow-up. The therapist should make every effort to get the physical therapy records to the consulting physician.

Before sending a client back to his or her doctor, have someone else (e.g., case manager, physical therapy colleague or mentor, nursing staff if available) double check your findings and discuss your reasons for referral. Recheck your own findings at a second appointment. Are they consistent?

Consider checking with the medical doctor by telephone. Perhaps the physician is aware of the problem, but the therapist does not have the patient/client records and is unaware of this fact. As mentioned it is not uncommon for physicians to send a client to physical therapy as part of their own differential diagnostic process. For example, they may have tried medications without success and the client does not want surgery or more drugs. The doctor may say, “Let’s try physical therapy. If that doesn’t change the picture, the next step is …”

As a general rule, try to send the client back to the referring physician. If this does not seem appropriate, call and ask the physician how he or she wants to handle the situation. Describe the problem and ask: