Surface Anatomy

1 Define and pronounce the key terms and anatomic terms in this chapter.

2 Discuss how the surface anatomy of the face and neck may impact dental clinical procedures.

3 Locate and identify the regions and associated surface landmarks of the head and neck on a diagram and a patient.

4 Correctly complete the review questions and activities for this chapter.

5 Integrate an understanding of surface anatomy into the clinical practice of dental procedures.

Guidelines used to consider the facial view of the anterior teeth or the vertical dimensions of the face to create a pleasing proportion.

Surface Anatomy Overview

The dental professional must be thoroughly familiar with the surface anatomy of the head and neck in order to examine patients. Surface anatomy is the study of the structural relationships of the external features of the body to the internal organs and parts. The features of the surface anatomy provide essential landmarks for many of the deeper anatomic structures that will be discussed and examined in subsequent chapters. Thus the examination of these accessible surface features by visualization and palpation can give vital information about the health of deeper tissue (Appendix B). Any changes noted in these surface features must be recorded by the dental professional in the patient record. In addition, procedures in dental practice are related to the anatomic features of the head and neck (see Chapter 1).

A certain amount of variation in surface features is within a normal range. However, a change in surface features in a given person may signal a condition of clinical significance. Thus it is not variations among individuals but changes in a particular individual that should be noted. The underlying histologic and embryologic concerns may also help in the study of a patient’s head and neck; therefore, related reference materials may need to be reviewed (Appendix A).

The study of anatomy of the head and neck begins with the division of the surface into regions. Within each region are certain surface landmarks. Practice finding these surface landmarks in each region on your own face and neck using a mirror to improve the skills of examination. Later, locate them on peers and then on patients in a clinical setting.

In this text, the illustrations of the head and neck, as well as any structures associated with them, are oriented to show the patient’s head in anatomic position, unless otherwise noted (see Chapter 1). This is the same as if the patient is viewed straight on while sitting upright in the dental chair.

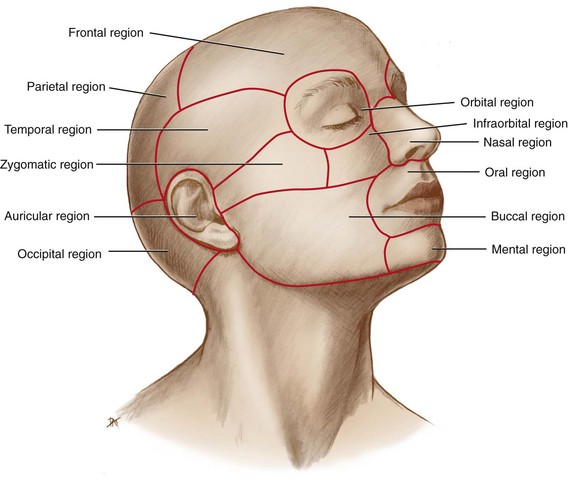

Regions of Head

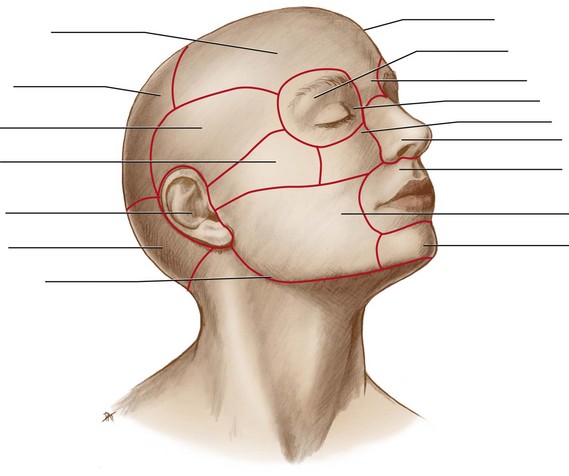

The regions of the head include the frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal, auricular, orbital, nasal, infraorbital, zygomatic, buccal, oral, and mental regions (Figure 2-1). These regions are all noted during an overall evaluation of the head. During an extraoral examination, seat the patient upright and in a relaxed manner, while noting the symmetry and coloration of the surface (see Appendix B).

FIGURE 2-1 Regions of the head noted that include the frontal, parietal, occipital, temporal, auricular, orbital, nasal, infraorbital, zygomatic, buccal, oral, and mental regions.

The superficial to deep relationships of the head are relatively simple over most of its posterior and superior surfaces but are more difficult in the region of the face. The underlying bony structure of the head is covered in Chapter 3. The underlying muscles of the head are covered in Chapter 4. The underlying glandular tissue, such as the salivary, lacrimal, and thyroid glands, is covered in Chapter 7. Lymph nodes that are located throughout the tissue of the head are covered in Chapter 10, and the vascular and nervous systems are covered in Chapters 6 and 8, respectively.

Frontal Region

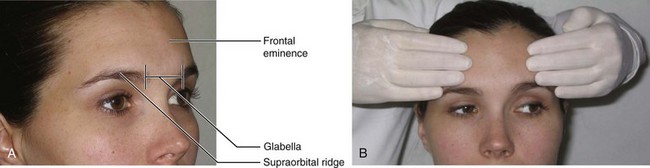

The frontal region of the head includes the forehead and the area superior to the eyes (Figure 2-2). Just inferior to each eyebrow is the supraorbital ridge (soo-prah-or-bit-al) or superciliary ridge. The smooth elevated area between the eyebrows is the glabella (glah-bell-ah), which tends to be flat in children and adult females and to form a rounded prominence in adult males. The prominence of the forehead, the frontal eminence (em-i-nins), is also evident. The frontal eminence is usually more pronounced in children and adult females, and the supraorbital ridge is more prominent in adult males. During an extraoral examination, stand near the patient to visually inspect the forehead and bilaterally palpate (Figure 2-2, B).

Parietal and Occipital Regions

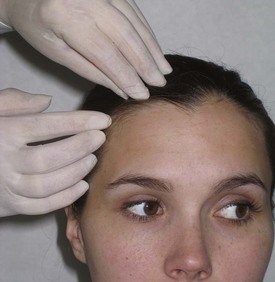

Both the parietal region (pah-ri-it-al) and occipital region (ok-sip-it-al) of the head are covered by the scalp. The scalp consists of layers of soft tissue overlying the bones of the braincase. Large areas of the scalp may be covered by hair. Trying to fully survey these areas during an extraoral examination is important because many lesions may be hidden visually from the clinician as well as the patient. During an extraoral examination, stand near the patient to visually inspect the entire scalp by moving the hair, especially around the hairline, starting from one ear and proceeding to the other ear (Figure 2-3).

Temporal and Auricular Regions

Within the temporal region (tem-poh-ral) is the temple, the superficial side of the head posterior to each eye.

The auricular region (aw-rik-yuh-lar) of each side of the head has the external ear as a prominent feature (Figure 2-4). The external ear is composed of an auricle (aw-ri-kl) or oval flap of the ear and the external acoustic meatus (ah-koos-tik me-ate-us). The auricle collects sound waves. The external acoustic meatus is a tube through which sound waves are transmitted to the middle ear within the skull.

FIGURE 2-4 Lateral view of the right external ear with its landmarks within the auricular region noted during an extraoral examination.

The superior and posterior free margin of the auricle is the helix (heel-iks), which ends inferiorly at the lobule (lob-yule), the fleshy protuberance of the earlobe. The upper apex of the helix is usually level with the eyebrows and the glabella, and the lobule is approximately at the level of the apex of the nose.

The tragus (tra-gus) is the smaller flap of tissue of the auricle anterior to the external acoustic meatus. The tragus, as well as the rest of the auricle, is flexible when palpated due to its underlying cartilage. The other flap of tissue opposite the tragus is the antitragus (an-tie-tra-gus). Between the tragus and antitragus is a deep notch, the intertragic notch (in-ter-tra-gic). The external acoustic meatus and tragus are important landmarks to note when taking certain radiographs and administering certain local anesthesia blocks. During an extraoral examination, visually inspect and manually palpate the external ear, as well as the scalp and face around each ear (Figure 2-5).

Orbital Region

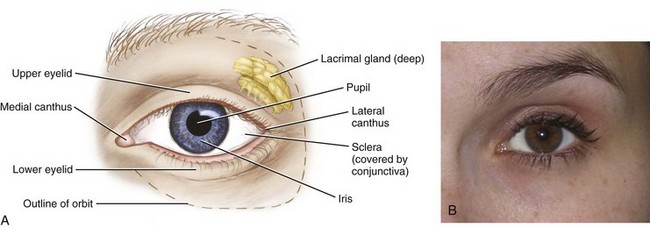

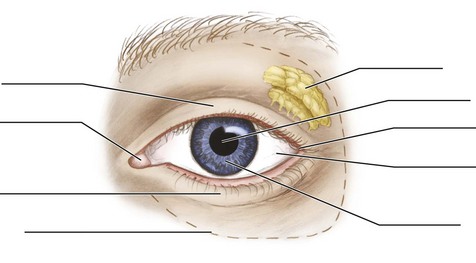

In the orbital region (or-bit-al) of each side of the head, the eyeball and all its supporting structures are contained in the bony socket or orbit (or-bit) (Figure 2-6). The eyes are usually near the midpoint of the vertical height of the head. The width of each eye is usually the same as the distance between the eyes. On the eyeball is the white area or sclera (skler-ah) with its central area of coloration, the circular iris (eye-ris). The opening in the center of the iris is the pupil (pew-pil), which appears black and changes size as the iris responds to changing light conditions.

FIGURE 2-6 Frontal view of the left eye with the landmarks of the orbital region noted (A) with visualization of the eye during an extraoral examination (B).

Two movable eyelids, upper and lower, cover and protect each eyeball. Behind each upper eyelid and deep within the orbit are the lacrimal glands (lak-ri-mal), which produce lacrimal fluid or tears.

The conjunctiva (kon-junk-ti-vah) is the delicate and thin membrane lining the inside of the eyelids and the front of the eyeball. The outer corner(s) where the upper and lower eyelids meet is the lateral canthus (plural, canthi) (kan-this, kan-thy) or outer canthus. The inner angle(s) of the eye is the medial canthus (plural, canthi) or inner canthus. These canthi are important landmarks to use when taking extraoral radiographs. During an extraoral examination, stand near the patient to visually inspect the eyes with their movements and responses to light and action (Figure 2-6, B).

Nasal Region

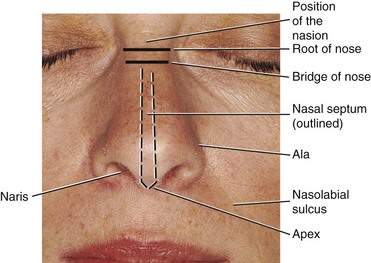

The main feature of the nasal region (nay-zil) of the head is the external nose (Figure 2-7). The root of the nose is located between the eyes. Inferior to the glabella is a midpoint landmark of the nasal region that corresponds with the junction between the underlying bones, the nasion (nay-ze-on). Inferior to the nasion is the bony structure that forms the bridge of the nose. The tip or apex of the nose is flexible when palpated because it is formed from cartilage.

FIGURE 2-7 Frontal view of the face with the landmarks of the nasal region noted during an extraoral examination.

Inferior to the apex on each side of the nose is a nostril(s) or naris (plural, nares) (nay-ris, nay-rees). The nares are separated by the midline nasal septum (nay-zil sep-tum). The nares are bounded laterally on each side by a winglike cartilaginous structure(s), the ala (plural, alae) (a-lah, a-lay) of the nose. The width between the alae should be about the same width as one eye or the space between the eyes. Both the nasion and the alae of the nose are landmarks used when taking extraoral radiographs. Stand near the patient to visually inspect the external nose and palpate it during an extraoral examination by starting at the root of the nose and proceeding to its apex (Figure 2-8).

Infraorbital, Zygomatic, and Buccal Regions

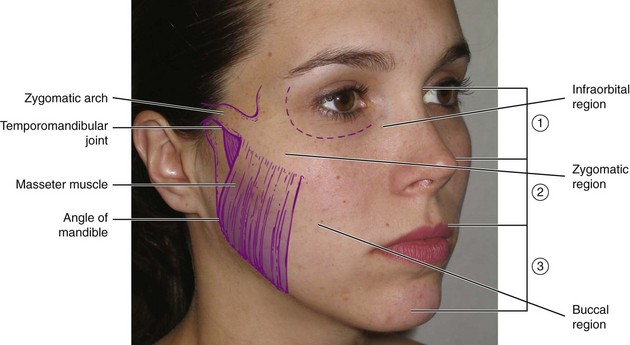

The infraorbital, zygomatic, and buccal regions of each side of the head are all located on the facial aspect (Figure 2-9). The infraorbital region (in-frah-or-bit-al) of the head is located inferior to the orbital region and lateral to the nasal region. Farther laterally is the zygomatic region (zy-go-mat-ik), which overlies the cheekbone, the zygomatic arch. The zygomatic arch extends from just inferior to the lateral margin of the eye toward the middle part of the ear.

FIGURE 2-9 Lateral view of the face with landmarks of the zygomatic and buccal regions noted as well as the vertical dimension of the face, where the face is divided into thirds, which allows a comparison of the three parts of the face for functional and esthetic purposes using the Golden Proportions.

Inferior to the zygomatic arch, and just anterior to the ear, is the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) (tem-poh-ro-man-dib-you-lar), which is discussed in detail in Chapter 5. This is where the upper skull forms a joint with the lower jaw. The movements of the joint can be felt when opening and closing the mouth or moving the lower jaw to the right or left. After palpating the joint during various movements, feel the lower jaw moving at the temporomandibular joint on a patient by gently placing a finger into the outer part of the external acoustic meatus.

The buccal region of the head is composed of the soft tissue of the cheek. The cheek forms the side of the face and is the broad area between the nose, mouth, and ear. Most of the upper cheek is fleshy and is mainly formed by a mass of fat and muscles. One of these is the strong masseter muscle (mass-et-er), which is felt when a patient clenches the teeth. The sharp angle of the lower jaw inferior to the ear’s lobule is the angle of the mandible. During an extraoral examination, stand near the patient to visually inspect and palpate bilaterally the infraorbital, zygomatic, and buccal regions, as well as the temporomandibular joint.

The face can be divided into thirds, and this perspective is the vertical dimension of the face. A discussion of vertical dimension allows a comparison of the three parts of the face for functional and esthetic purposes using the Golden Proportions, a set of guidelines. Loss of height in the lower third, which contains the teeth and jaws, can occur in certain circumstances such as with aging and periodontal disease.

Oral Region

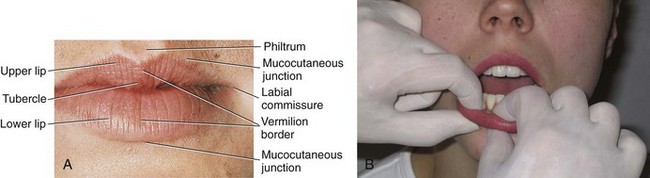

The oral region of the head has many structures within it such as the lips, oral cavity, palate, tongue, floor of the mouth, and parts of the throat. The lips are the gateway of the oral region, and each lip’s vermilion border (ver-mil-yon) or zone has a darker appearance than the surrounding skin (Figure 2-10, A). The lips are outlined from the surrounding skin by a transition zone, the mucocutaneous junction (moo-ko-ku-tay-nee-us). Both lips are covered externally by skin and internally by the same mucous membranes that line the oral cavity (see discussion next). The width of the lips at rest should be about the same distance as that between the irises of the eyes.

FIGURE 2-10 Frontal view of the lips within the oral region (A) with bidigital palpation of the lips during an intraoral examination (B).

Superior to the midline of the upper lip, extending downward from the nasal septum, is a vertical groove on the skin, the philtrum (fil-trum). Inferior to the philtrum, the midline of the upper lip terminates in a thicker area or tubercle of the upper lip (too-ber-kl). The upper and lower lips meet at each corner of the mouth or labial commissure (kom-i-shoor). The groove running upward between each labial commissure and each ala of the nose is the nasolabial sulcus (nay-zo-lay-be-al sul-kus) (see Figure 2-7). The lower lip extends to the horizontally placed labiomental groove (lay-bee-o-ment-il), which separates the lower lip from the chin in the mental region (see Figure 2-22). During intraoral examination, bidigitally palpate the lips and visually inspect them in a systematic manner from one commissure to the other (see Figure 2-10, B).

Oral Cavity

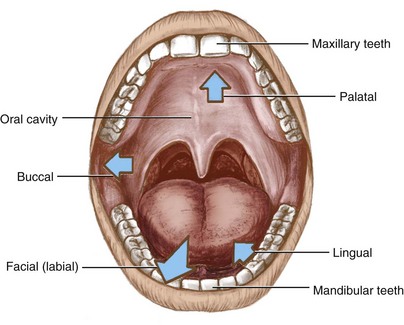

The inside of the mouth is known as the oral cavity. The jaws are within the oral cavity and deep to the lips (Figure 2-11). Underlying the upper lip is the upper jaw or maxilla(e) (mak-sil-ah, mak-sil-lay). The bone underlying the lower lip is the lower jaw or mandible (man-di-bl) (see Figure 3-4).

FIGURE 2-11 Oral cavity and jaws with the designation of the terms lingual, palatal, buccal, facial, and labial within the oral cavity.

An understanding of the divisions of the oral cavity is aided by knowing its boundaries; many structures of the face and oral cavity mark the boundaries of the oral cavity (see Figure 2-1). The lips of the face mark the anterior boundary of the oral cavity, and the pharynx or throat is the posterior boundary. The cheeks of the face mark the lateral boundaries, and the palate marks the superior boundary. The floor of the mouth is the inferior border of the oral cavity.

Many areas in the oral cavity are identified with orientational terms based on their relationship to other orofacial structures such as the facial surface, lips, cheeks, tongue, and palate. Structures closest to the facial surface or lips are facial and labial. Facial structures closest to the inner cheek are considered buccal. Structures closest to the tongue are lingual, and those closest to the palate are palatal.

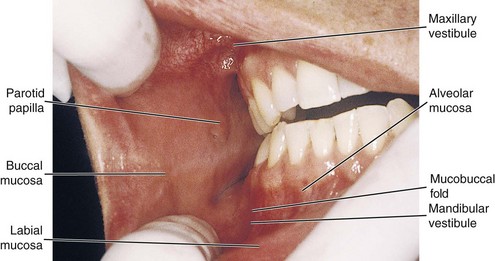

The oral cavity is lined by a mucous membrane or oral mucosa (mu-ko-sah) (Figure 2-12). The inner parts of the lips are lined by a pink and thick labial mucosa. The labial mucosa is continuous with the equally pink and thick buccal mucosa that lines the inner cheek. Both the labial and buccal mucosa may vary in coloration, as do other regions of healthy oral mucosa, in individuals with pigmented skin. The buccal mucosa covers a dense pad of inner tissue, the buccal fat pad. To visually examine the labial mucosa during an intraoral examination, ask the patient to open the mouth slightly and pull the lips away from the teeth. Then gently pull the buccal mucosa slightly away from the teeth so as to be able to bidigitally palpate the inner cheek, using circular compression.

FIGURE 2-12 Oral view of the buccal and labial mucosa of the oral cavity with landmarks noted during an intraoral examination.

Further landmarks can be noted in the oral cavity. On the inner part of the buccal mucosa, just opposite the maxillary second molar, the parotid papilla (pah-rot-id pah-pil-ah) is a small elevation of tissue that protects the duct opening from the parotid salivary gland. During an intraoral examination, observe the salivary flow from each duct after drying it. An elevation on the posterior aspects of the maxilla just posterior to the most distal molar is the maxillary tuberosity (mak-sil-lare-ee too-beh-ros-i-tee).

The upper and lower horseshoe-shaped spaces in the oral cavity between the lips and cheeks anteriorly and laterally and the teeth and their soft tissue medially and posteriorly are considered the maxillary and mandibular vestibules (ves-ti-bules). Deep within each vestibule is the vestibular fornix (for-niks), where the pink and thick labial or buccal mucosa meets the redder and thinner alveolar mucosa (al-vee-o-lar) at the mucobuccal fold (mu-ko-buk-al). The labial frenum (plural, frena) (free-num, free-nah) or frenulum is a fold(s) of tissue located at the midline between the labial mucosa and the alveolar mucosa on both the maxilla and mandible (Figure 2-13).

FIGURE 2-13 Frontal view of the oral cavity with its landmarks noted during an intraoral examination.

Teeth are located within the upper and lower jaws of the oral cavity. The teeth of the maxilla are the maxillary teeth, and the teeth of the mandible are the mandibular teeth (man-dib-you-lar). The maxillary anterior teeth should overlap the mandibular anterior teeth, and posteriorly, the maxillary buccal cusps should overlap the mandibular buccal cusps. Both dental arches in the adult have permanent teeth that include the incisors (in-sigh-zers), canines (kay-nines), premolars (pre-mo-lers), and molars (mo-lers).

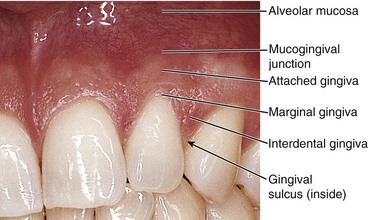

Surrounding both the maxillary and mandibular teeth are the gums or gingiva (jin-ji-vah) (or more accurately, but not commonly by the dental community, using its plural form, gingivae [jin-ji-vay]), composed of a firm, pink oral mucosa (Figure 2-14; see also Figure 2-13). The gingiva that tightly adheres to the bone around the roots of the teeth is the attached gingiva. The attached gingiva may have areas of pigmentation. The line of demarcation between the firmer and pinker attached gingiva and the movable and redder alveolar mucosa is the scallop-shaped mucogingival junction (mu-ko-jin-ji-val).

FIGURE 2-14 Close-up of the gingiva with its associated landmarks noted during an intraoral examination.

At the gingival margin of each tooth is the nonattached or marginal gingiva or free gingiva. The inner surface of the marginal gingiva faces a space(s) or gingival sulcus (plural, sulci) (sul-kus, sul-ky). The interdental gingiva (in-ter-den-tal) or interdental papilla is an extension of attached gingiva between the teeth. During an intraoral examination, retract the buccal and labial mucosal tissue in order to visually inspect and bidigitally palpate the vestibular area and the gingival tissue, using circular compression.

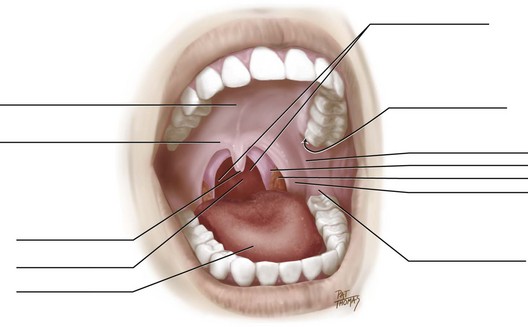

Palate

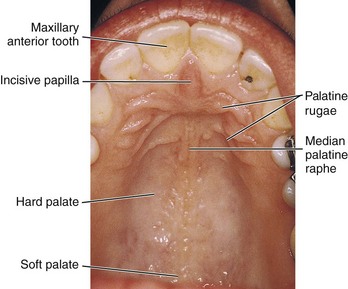

The roof of the mouth, or palate (pal-it), has two parts: hard and soft (Figure 2-15). The firmer, whiter, anterior part is the hard palate. A small bulge of tissue at the most anterior part of the hard palate, lingual to the anterior teeth, is the incisive papilla (in-sy-ziv pah-pil-ah). Directly posterior to this papilla are palatine rugae (ru-gay), which are firm, irregular ridges of tissue.

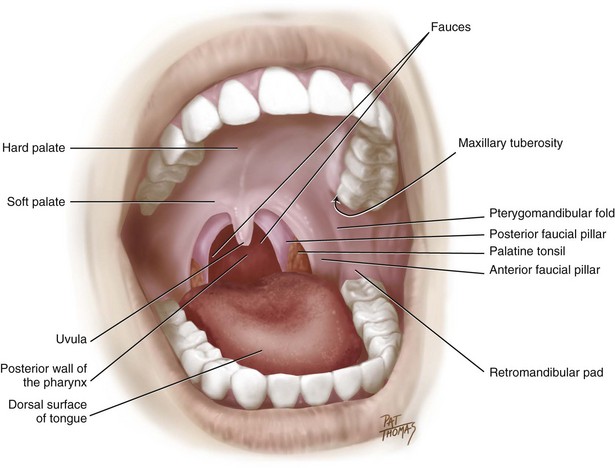

The yellower and looser posterior part of the palate is the soft palate; it is the smaller part of the palate as it only comprises 15% of the total surface (see Figures 2-15 and 2-21). It is connected to the hard palate but it can be separately elevated and depressed by muscles (see Chapter 4).

A midline muscular structure, the uvula of the palate (u-vu-lah), hangs from the posterior margin of the soft palate. A midline ridge of tissue on the hard palate is the median palatine raphe (pal-ah-tine ra-fe), which runs from the uvula to the incisive papilla.

The pterygomandibular fold (teh-ri-go-man-dib-yule-lar) is a fold of tissue that extends from the junction of the hard and soft palates on each side down to the mandible, just posterior to the most distal mandibular molar, and stretches when the patient opens the mouth wider. This fold covers a deeper fibrous structure and separates the cheek from the throat. In addition, in this area just posterior to the most distal mandibular molar is a dense pad of tissue, the retromolar pad (re-tro-moh-ler).

During an intraoral examination, have the patient tilt his or her head back slightly and extend the tongue to visually inspect the soft palate. Use the overhead dental light and a mouth mirror to intensify the light source and view the palatal and pharyngeal regions. Then, gently place the mouth mirror with the mirror side down on the middle of the tongue and ask the patient to say “ah” (see Figure 4-31). As this is done, visually observe the uvula and any visible parts of the pharynx. Then, compress the hard and soft palates with the first or second finger of one hand, avoiding circular compression to prevent initiating the gag reflex.

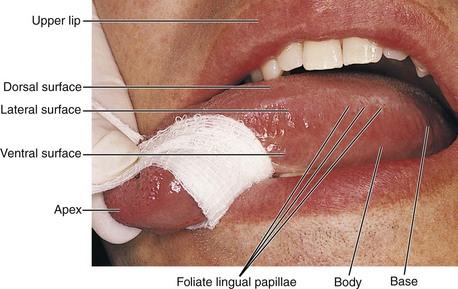

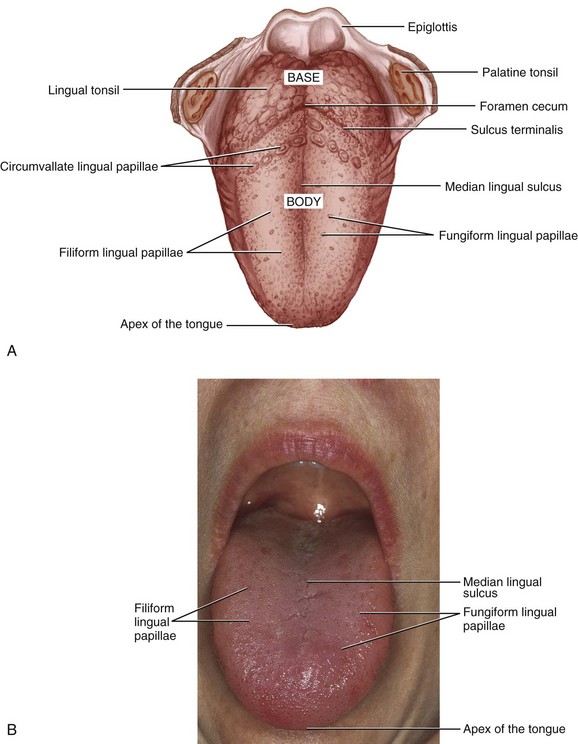

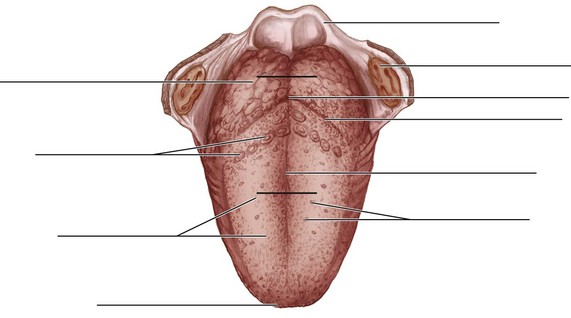

Tongue

The tongue is a prominent feature of the oral region (Figure 2-16). The posterior third is the base of the tongue or pharyngeal part. The base of the tongue attaches to the floor of the mouth. The base of the tongue does not lie within the oral cavity but within the oral part of the throat. The anterior two thirds of the tongue is termed the body of the tongue or oral part since it lies within the oral cavity. The tip of the tongue is the apex of the tongue. Certain surfaces of the tongue have small elevated structures of specialized mucosa, the lingual papillae (pah-pil-ay), some of which are associated with taste buds.

FIGURE 2-16 Lateral view of the tongue with its parts and their landmarks noted during an intraoral examination.

The side or lateral surface of the tongue is noted for its vertical ridges, the foliate lingual papillae (fo-lee-ate), which contain taste buds. These lingual papillae are more prominent in children.

The top surface or dorsal surface of the tongue has a midline depression, the median lingual sulcus, corresponding with the position of a midline fibrous structure deep within the tongue (Figure 2-17). In the tongue, dorsal and posterior are not equivalent terms, nor are ventral and anterior the same either. Instead, they are four different locations. This is because the human tongue still has the same orientation as the tongue of four-footed animals, in which anterior and posterior originally meant toward the nose and tail, respectively, and dorsal and ventral refer to the back and belly, respectively (see Chapter 1). Our upright posture on our two feet is the reason that dorsal and posterior have become synonyms in the rest of the body and now are used in that manner when referring to these surfaces.

FIGURE 2-17 Dorsal view of the tongue with its landmarks noted (A) and during an intraoral examination (B).

The dorsal surface of the tongue also has many lingual papillae. The slender, threadlike lingual papillae are the filiform lingual papillae (fil-i-form), which give the dorsal surface its velvety texture. The red mushroom-shaped dots are the fungiform lingual papillae (fun-ji-form). These latter lingual papillae are more numerous on the apex and contain taste buds.

Farther posteriorly on the dorsal surface of the tongue and more difficult to see clinically is a V-shaped groove, the sulcus terminalis (ter-mi-nal-is). The sulcus terminalis separates the base from the body of the tongue. Where the sulcus terminalis points backward toward the throat is a small, pitlike depression, the foramen cecum (for-ay-men se-kum). The circumvallate lingual papillae (serk-um-val-ate), which are 10 to 14 in number, line up along the anterior side of the sulcus terminalis on the body. These large mushroom-shaped lingual papillae have taste buds. Even farther posteriorly on the dorsal surface of the tongue base on each side is an irregular mass of lymphoid tissue, the lingual tonsil (ton-sil).

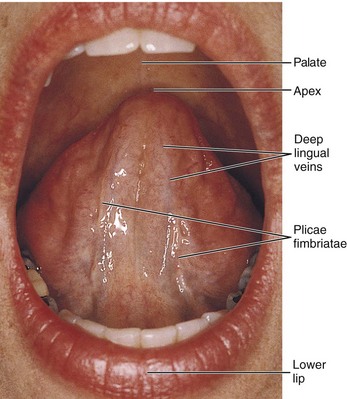

The underside or ventral surface of the tongue is noted for its visibly large blood vessels, the deeper lingual veins, running close to the surface (Figure 2-18). Lateral to the deep lingual veins on each side is the plica fimbriata (plural, plicae fimbriatae) (pli-kah fim-bree-ay-tah, pli-kay fim-bree-ay-tay), a fold(s) with fringelike projections. Again, the term used for the underside of the tongue, ventral, referred originally to four-footed animals in anatomic position and now is used for that surface for our upright position on our two feet.

To examine the dorsal and lateral surfaces of the tongue, have the patient slightly extend the tongue and wrap gauze around the anterior third of the tongue in order to obtain a firm grasp (see Figure 2-16). First, digitally palpate the dorsal surface. Then, turn the tongue slightly on its side to visually inspect and bidigitally palpate its base and lateral borders. To examine the ventral surface, have the patient slightly lift the tongue to visually inspect and digitally palpate its surface.

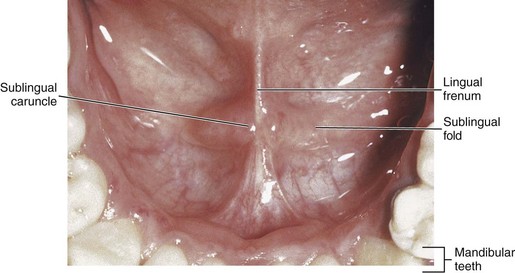

Floor of the Mouth

The floor of the mouth is located inferior to the ventral surface of the tongue (Figure 2-19). The lingual frenum (free-num) or frenulum is a midline fold of tissue between the ventral surface of the tongue and the floor of the mouth.

FIGURE 2-19 View of the floor of the mouth with its landmarks noted during an intraoral examination.

A ridge of tissue also exists on each side of the floor of the mouth, the sublingual fold (sub-ling-gwal) or plica sublingualis. Together these folds are arranged in a V-shaped configuration from the lingual frenum to the base of the tongue. The sublingual folds contain duct openings from the sublingual salivary gland. The small papilla or sublingual caruncle (kar-unk-el) at the anterior end of each sublingual fold contains the duct openings from both the submandibular and sublingual salivary glands.

While the patient lifts the tongue to the palate, visually inspect the mucosa of the floor of the mouth. Use the overhead dental light as well as a mouth mirror to intensify the light source. Bimanually palpate the sublingual area by placing an index finger intraorally and the fingertips of the opposite hand extraorally under the chin, compressing the tissue between the fingers (see Figure 7-10). Palpate the lingual frenum and then dry each sublingual caruncle with gauze to observe the salivary flow from the ducts.

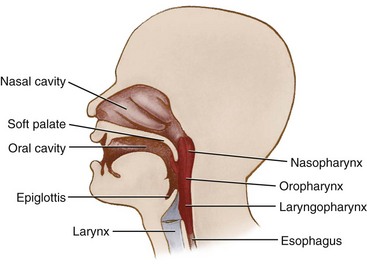

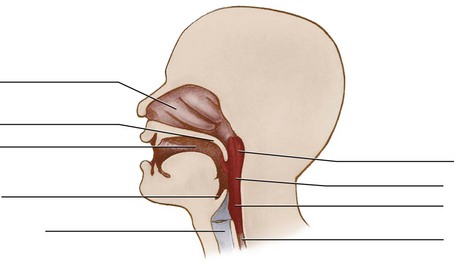

Pharynx

The oral cavity also provides the entrance into the throat or pharynx (far-inks). The pharynx is a muscular tube that serves both the respiratory and digestive systems. The pharynx consists of three parts: nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx (Figure 2-20). Parts of the nasopharynx and oropharynx are visible during an intraoral examination when examining the palatal area with the patient saying “ah.” The laryngopharynx (lah-ring-go-far-inks) is located more inferior, close to the laryngeal opening, and thus is not visible in an intraoral examination.

The part of the pharynx that is superior to the level of the soft palate is the nasopharynx (nay-zo-far-inks). The nasopharynx is continuous with the nasal cavity. The part of the pharynx that is between the soft palate and the opening of the larynx is the oropharynx (or-o-far-inks) (Figure 2-21; see Chapter 4 on the muscles of the pharynx).

Behind the base of the tongue and in front of the oropharynx is the epiglottis (ep-ih-glah-tis), a flap of cartilage (see Figure 2-20). At rest, the epiglottis is upright and allows air to pass through the larynx and into the rest of the respiratory system. During swallowing, it folds back to cover the entrance to the larynx, preventing food and liquid from entering the trachea and then entering the lungs.

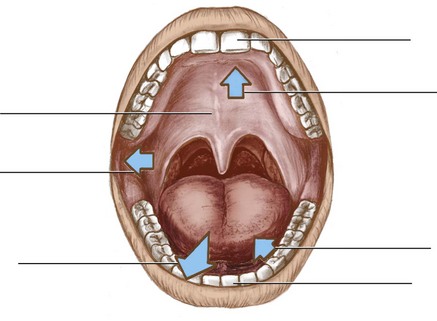

The opening from the oral region into the oropharynx is the fauces (faw-seez) or faucial isthmus. The fauces are formed laterally on each side by both the anterior faucial pillar (faw-shawl pil-er) and the posterior faucial pillar (also called tonsillar pillars, or palatal arches). Tonsillar tissue, the palatine tonsils (pal-ah-tine), is located between each of these pillars or folds of tissue created by underlying muscles (Figure 2-21; also see Figure 4-31). The palatine tonsils are the tonsillar tissue that patients call their “tonsils.”

Mental Region

The chin is the major feature of the mental region (ment-il) of the head (Figure 2-22). The mental protuberance (pro-too-ber-ins) is the prominence of the chin. The mental protuberance is often more pronounced in adult males. The labiomental groove (lay-bee-o-ment-il), a horizontal groove between the lower lip and the chin mentioned in the description of the oral region, should be approximately midway between the apex of the nose and the chin and level with the angle of the mandible.

FIGURE 2-22 Frontal view of the mental region with its landmarks noted (A) and with palpation of the mental region during an intraoral examination (B).

Also present on the chin in some individuals is a midline depression or dimple that marks the underlying bony fusion of the lower jaw. Visually inspect and bilaterally palpate the chin during an extraoral examination (see Figure 2-22).

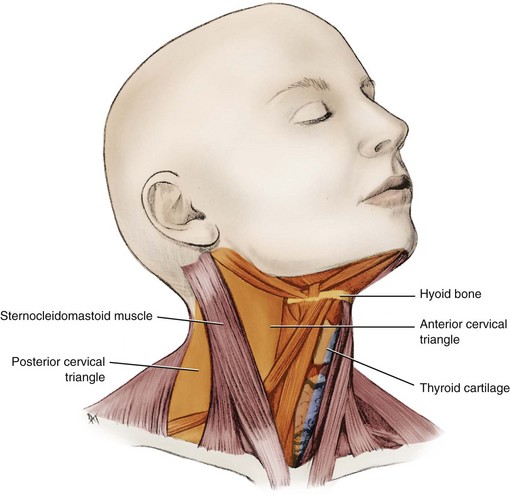

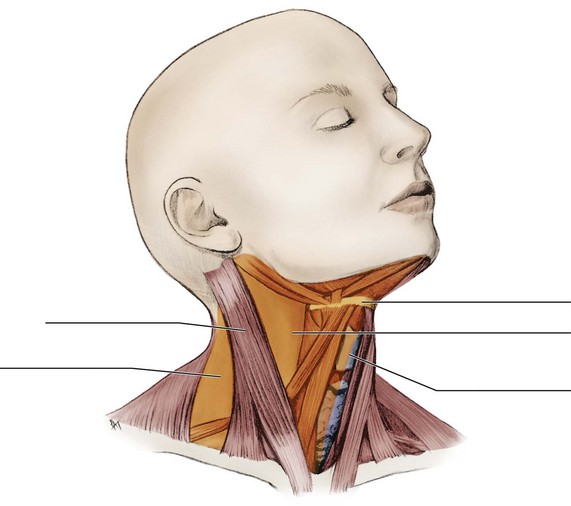

Regions of Neck

The neck extends from the skull and mandible down to the clavicles and sternum. The posterior neck is higher than the anterior neck to connect cervical viscera with the posterior openings of the nasal and oral cavities.

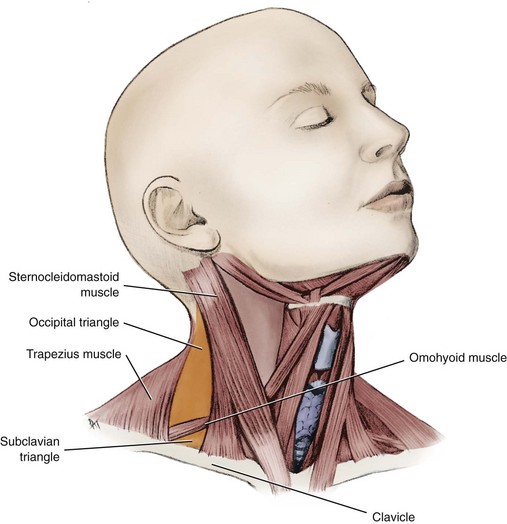

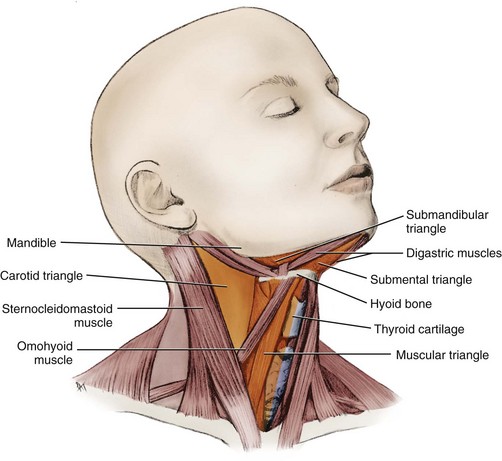

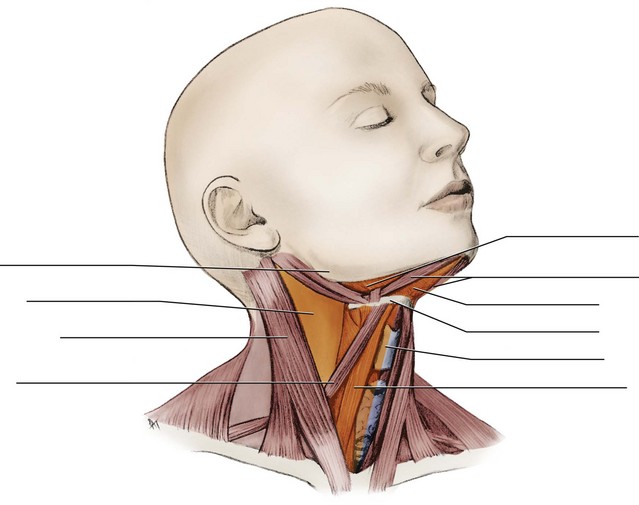

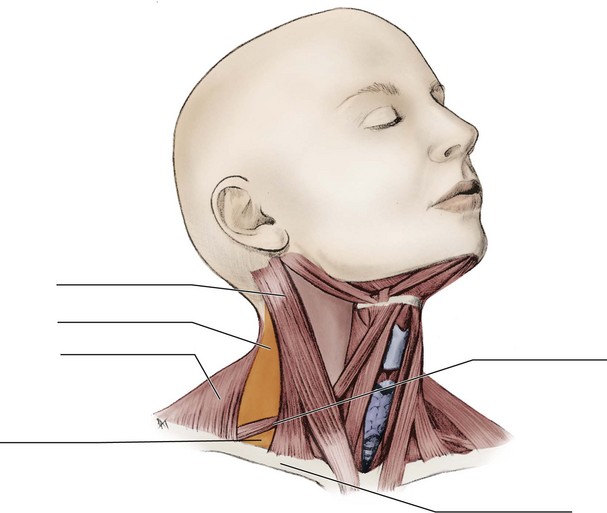

The regions of the neck can be divided into different cervical triangles on the basis of the large bones and muscles in the area, with each triangle containing structures that are palpated during an extraoral examination (Figure 2-23). Chapters 3 and 4 further describe these bones and muscles, respectively, with their cervical triangles as well as extraoral examination of these structures (see Appendix B). Structures deep to the surface of these cervical triangles are also discussed in other chapters.

FIGURE 2-23 Neck region divided into the anterior cervical triangle and posterior cervical triangle.

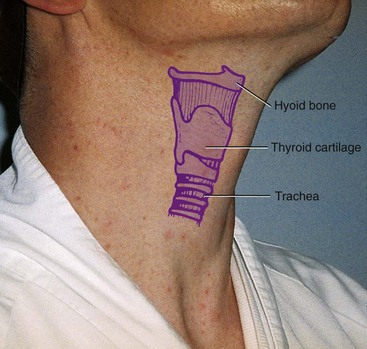

The large strap muscle, the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM) (stir-no-kli-do-mass-toid), divides each side of the neck diagonally into an anterior cervical triangle (ser-vi-kal) and posterior cervical triangle. The SCM is palpated during an extraoral examination as are the regions anterior and posterior to it. The anterior region of the neck corresponds with the two anterior cervical triangles, which are separated by a midline. Major structures that pass between the head and thorax can be accessed through the anterior cervical triangle. The lateral region of the neck, posterior to the SCM, is considered the posterior cervical triangle on each side.

At the anterior midline, the largest of the larynx’s cartilages, the thyroid cartilage (thy-roid), is visible as the laryngeal prominence or “Adam’s apple,” especially in adult males. This cartilage is superior to the thyroid gland, which is also palpated during an extraoral examination (discussed in detail in Chapter 7) (Figure 2-24 and see Figure 7-10). The superior thyroid notch of the thyroid cartilage is just superior to the laryngeal prominence and is also a palpable landmark of the neck. The vocal cords or ligaments of the larynx (lare-inks) or “voice box” are attached to the posterior surface of the thyroid cartilage.

FIGURE 2-24 Lateral view of the anterior cervical triangle of the neck with a superimposition of its skeletal landmarks.

The hyoid bone (hi-oid) is also located in the anterior midline and suspended in the neck, superior to the thyroid cartilage (see Figure 2-24). Many muscles attach to the hyoid bone, which controls the position of the base of the tongue. Effectively palpate the hyoid bone by feeling inferior to and medial to the angles of the mandible; it can also be moved side to side. Do not confuse the hyoid bone with the inferiorly placed thyroid cartilage when palpating the neck region.

The anterior cervical triangle on each side can be further subdivided into smaller triangular regions by muscles in the area that are not as prominent as those of the SCM (Figure 2-25). For example, the superior part of each anterior cervical triangle is demarcated by the main parts of the digastric muscle (both bellies) and the mandible, forming a submandibular triangle (sub-man-dib-you-lar). The inferior part of each anterior cervical triangle is further subdivided by the omohyoid muscle into a carotid triangle (kah-rot-id) superior to it and a muscular triangle inferior to it. A midline submental triangle (sub-men-tal) is also formed by the two main parts of the digastric muscle (its right and left anterior bellies) and the hyoid bone.

FIGURE 2-25 Division of the anterior cervical triangle into the submandibular, submental, carotid, and muscular triangles.

Each posterior cervical triangle can also be further subdivided into smaller triangular regions on each side by muscles in the area (Figure 2-26). The omohyoid muscle divides the posterior cervical triangle into the occipital triangle (ok-sip-it-al) superior to it and the subclavian triangle (sub-klay-vee-an) inferior to it on each side.

Identification Exercises

Identify the structures on the following diagrams by filling in each blank with the correct anatomic term. You can check your answers by looking back at the figure indicated in parentheses for each identification diagram.

1. (Figures 2-1, 2-2, 2-4, and 2-9)

2. (Figure 2-6, A)

3. (Figure 2-11)

4. (Figure 2-17, A)

5. (Figure 2-20)

6. (Figure 2-21)

7. (Figure 2-23)

8. (Figure 2-25)

9. (Figure 2-26)

1. Those structures in the oral region that are closest to the tongue are considered

2. Which of the following terms is used to describe the smooth, elevated area between the eyebrows in the frontal region?

3. In which region of the head and neck is the tragus located?

4. The tissue at the junction between the labial or buccal mucosa and the alveolar mucosa is the

5. Into which cervical triangles does the sternocleidomastoid muscle divide the neck region?

6. The parietal and occipital regions are covered by the

7. Which of the following statements concerning the location of the medial canthus is CORRECT when comparing it with the lateral canthus?

8. Which of the following structures extends from just inferior to the lateral margin of the eye toward the ear?

9. The opening from the oral region into the oropharynx is the

10. Which of the following terms is used for the small papilla at the anterior end of each sublingual fold?

11. Which of the following structures is the opening in the center of the iris?

12. Which of the following structures is located between the tragus and the antitragus?

13. Which of the following structures separates the lower lip from the chin?

14. Which of the following structures is located on the dorsal surface of the tongue?

15. Which of the following structures is located directly posterior to the incisive papilla?