Small Animal Surgical Nursing

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

1 Describe the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative responsibilities of the veterinary technician in surgical assistance.

2 Describe indications and use of prophylactic antibiotics for surgical patients.

3 Describe signs of blood loss in the postoperative patient.

4 Discuss concerns related to hypothermia in anesthetized patients and describe methods for increasing patient body temperature intraoperatively and postoperatively.

5 Describe postoperative abnormalities that can occur in surgical incisions.

6 Describe the procedure for removal of skin sutures.

7 Discuss general considerations for care of bandages and drains.

8 List and describe indications, preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative considerations for common elective procedures in dogs and cats.

9 List and describe indications, preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative considerations for common nonelective procedures in dogs and cats.

10 List considerations related to client education for discharged surgical patients.

PREOPERATIVE PATIENT ASSESSMENT

The veterinary surgical candidate should undergo a complete preoperative assessment. It is important to know what the primary problem is so that specific needs can be anticipated. Elective surgical procedures will not require the same demands that emergency or urgent surgical procedures will. Eating, drinking, urination, and defecation habits of the animal should be ascertained. An animal that has not been eating or drinking will likely require rehydration before anesthesia and surgery. Rehydration may then necessitate a blood or plasma transfusion because dilution of the blood cell volume occurs with rehydration. Fluids should not be withheld to prevent anemia. If the animal has eaten the day of scheduled surgery, the procedure will have to be delayed to decrease the risk of aspiration (inhalation of stomach contents into the trachea and lungs). The animal should not have food for at least 12 hours before anesthesia, but water should not be withheld. Emergency surgeries will have to be performed whether the animal has eaten or not, but owners should be warned of the increased risk of aspiration. Temperature, pulse rate and quality, respiration rate and character, capillary refill time, mucous membrane color, body weight, and demeanor should be assessed before surgery. Abnormalities should be brought to the attention of the surgeon.

Preanesthetic screening will depend on the animal’s condition and reason for surgery. Specifics of this are covered in Chapter 27. From a nursing standpoint, it is important to discuss with the surgeon what diagnostics are appropriate before surgery and ensure that they are performed in a timely manner. Diagnostics might include blood work, such as packed-cell volume (PCV), total plasma protein (TP) concentration, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) concentration, blood glucose concentration, complete blood count (CBC), complete biochemical analysis, and heartworm test; blood gas analysis; electrocardiogram (ECG); radiographs; fine-needle mass aspiration; fecal analysis; and/or urinalysis. Abnormalities detected on the preanesthetic screen should be brought to the attention of the surgeon.

SURGICAL PREPARATION AND ANIMAL POSITIONING

It is the veterinary technician’s responsibility to inquire about the surgical procedure to be performed and what instrumentation will be required. The technician should have all the necessary equipment readily accessible and prepared for use. The operating room should be clean and anesthesia equipment checked for functionality and ready for use. A heated circulating water blanket should be placed on the operating table, turned on, and covered with a towel so that it is warm by the time the animal is positioned on the table. A heated water blanket should also be set up in the recovery cage (or the warmed blanket from the operating table can be placed in the cage with the animal). Hair clippers and skin cleansing solutions should also be made available for use.

Inadequate animal preparation or inappropriate positioning can hinder surgical technique and will result in wasted time spent correcting deficiencies. Aseptic protocol should always be followed with animal preparation and draping and with surgical instrument handling. The hair should be liberally clipped around the surgical site and the skin cleansed appropriately (see Chapters 28 and 29). The veterinary technician should be familiar with the type of surgery performed so that animal preparation is consistent and adequate.

PERIOPERATIVE ANTIBIOTICS

Prophylactic antibiotics are used to decrease the risk of infection in clean or clean-contaminated surgeries, but their use will not entirely eliminate infections associated with a surgical procedure. Using antibiotics to treat active infection is a completely different process and will not be discussed here. Antibiotics should never be given indiscriminately to animals undergoing surgery. All antibiotics have potential side effects, and their use also increases surgery cost. More importantly, indiscriminant use of antibiotics contributes to the development of resistant strains of bacteria (hospital “superbugs”) that are difficult to treat.

Indications for Prophylactic Antibiotics

• Operative time is more than 90 minutes. Open surgical wounds are constantly exposed to bacteria from the animal’s skin, the operative team, and the air. The longer the wound is open, the higher the chance of infection. Prolonged anesthesia also increases the risk.

• The patient is at increased risk of infection. Things that might increase the risk of infection include immunosuppressive drugs (steroids), Cushing’s disease (hyperadrenocorticism), some cancers, chemotherapy or radiation therapy, feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and/or feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) positive, or any other immunosuppressive factor.

• A hollow viscus is to be entered (i.e., gastrointestinal [GI] tract, urinary bladder).

• The incision is to involve an area that is difficult to aseptically prepare (such as a toe or ear).

• Orthopedic implants are placed.

• Joint procedures that are long and aggressive or certain joint procedures that require multiple entrances into the joint (arthroscopy).

• Consequences of infection could be devastating, such as total hip replacement or spinal surgery of any kind.

• Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for short, clean surgical procedures, such as simple mass removal, osteochondritis cartilage flap removal, ovariohysterectomy, castration, and simple biopsy.

Therapeutic drug levels must be present in the wound fluid (serum) at the time of surgical incision or the antibiotics will not be effective. They should be given at least 20 minutes before the surgical incision is made. Antibiotics given 3 or more hours before the procedure select for resistant bacteria. Prophylactic antibiotics given more than 3 to 5 hours after the surgical incision has been made will likely not be effective in preventing infection. There is no advantage to continuing antibiotics beyond 6 to 24 hours after surgery unless it is necessary to treat an active infection or a break in sterile technique occurred during surgery. The appropriate antibiotic should be of narrow spectrum (but effective against the potential contaminant), achieve good tissue concentrations, and have minimal side effects. The veterinarian in charge should be questioned as to what antibiotic is appropriate for what surgical procedure and when antibiotic prophylaxis is needed. If a break in sterile technique occurred or the animal has an active infection, antibiotics are continued in the postoperative period according to the manufacturer’s dosing recommendations and under the supervision of the veterinarian in charge. Continuing antibiotics for other reasons (i.e., you want to be on the safe side) is a misuse of prophylactic antibiotics.

MONITORING

Intraoperative and postoperative monitoring are critical to proper surgical nursing care. Chapter 27 covers anesthetic monitoring in detail, and the reader should refer to that chapter for further information. Some important components of patient monitoring as they pertain to surgery and recovery after surgery will be covered here.

During surgery, a surgical plane of anesthesia is crucial to appropriate surgical technique and animal well-being, and careful monitoring in the perioperative period might alert the observer to potential fatal complications. The postoperative phase is a critical transition period from general anesthesia to consciousness, and continual monitoring should be provided until the animal is safely extubated, normothermic, and in sternal recumbency. Surgery can result in several potential problems, including blood loss, hypothermia, pain, and cardiac and respiratory problems. The veterinary surgical technician must be prepared to deal with changes in animal status during and after surgery and address issues as the need arises. Monitoring should involve a series of evaluations and tests. Suspected complications during anesthesia and recovery are based on a group of signs consistent with a problem, not just one abnormality.

Patient monitoring does not stop once the animal has recovered from anesthesia. As long as the animal is hospitalized, vital signs, behavior, appetite, and the surgical incision should be evaluated. Depending on animal status, daily or more frequent observation of these parameters is performed. Abnormalities should be reported to the veterinarian in charge.

BLOOD LOSS

Many procedures can result in substantial blood loss as a complication, or blood loss could be due to the inherent nature of the procedure. PCV and TP should always be assessed before surgery to obtain a baseline value. Preoperative anemia should be brought to the attention of the veterinarian in charge, and, if present, a CBC should be performed. If substantial blood loss occurred during surgery, the PCV and TP should also be assessed postoperatively. It can be difficult to determine if an animal is hemorrhaging or has lost a substantial amount of blood immediately postoperative because a painful, recovering animal can have similar clinical signs. Temperature, heart rate, pulse quality, respiration, and character of mucous membranes should be examined periodically during and after surgery. Animals with substantial blood loss may experience continued hypothermia or a drop in body temperature, rapid heart rate with weak peripheral pulses, rapid respiratory rate, and pale or white mucous membranes. Abnormalities should be promptly reported to the veterinarian in charge. Other signs include abdominal enlargement if intraabdominal hemorrhage occurs, incision swelling or oozing of blood, and dyspnea and decreased ventral lung sounds if intrathoracic hemorrhage occurs. Another important thing to remember is that changes in PCV and TP may not occur immediately with blood loss, and these tests may need to be repeated a few hours after the incident of blood loss to document abnormalities or to assess continued blood loss. It is not unusual for the PCV and TP to drop 10% just as a result of anesthesia and surgery, even when no major blood loss occurred.

Besides PCV and TP determination, abdominocentesis (aspiration of fluid from the abdomen), thoracocentesis (aspiration of fluid from the thoracic cavity), or fine-needle aspiration beneath the incision can be performed when the patient is suspected of having substantial bleeding. If the sampled fluid has a PCV nearly equal to the systemic PCV and clinical signs are consistent with hemorrhage, the index of suspicion should be high. Treatment strategies include crystalloid fluid bolus, colloidal fluid administration, blood transfusion, oxygen carrier fluid administration (Oxyglobin), pressure bandages, and/or reoperation with ligation of bleeding vessels. The treatment of choice depends on the animal’s status and ability to maintain a stable condition. The reader should review the clinical signs and treatment strategies for various types of shock as discussed in Chapter 33.

HYPOTHERMIA

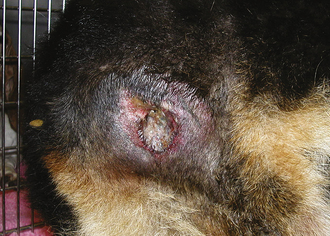

Hypothermia is defined as a subnormal body temperature. Once an animal is anesthetized, its body temperature begins to drop. It is important to monitor body temperature throughout general anesthesia and during recovery. All anesthetized animals should be placed on a heated circulating water blanket that is covered with a towel to help maintain body temperature, especially small dogs and all cats, during surgery. Although rare, if the body temperature rises above normal during the procedure, the heat source can be turned off. Small animals become hypothermic quickly when placed under general anesthesia, especially if a body cavity is opened. It is important to remember that the more surface area exposed (i.e., large incision exposing the abdominal organs), the faster and lower the body temperature is expected to drop. If the exposed area is moist, evaporative cooling occurs. Mechanisms to maintain body temperature during surgery include placing animals on heated circulating water blankets; wrapping paws and the body in plastic wrap to prevent heat loss (Figure 30-1); wrapping warm water bottles (or gloves filled with warm water) with a towel and placing them next to the animal; covering areas not involved in the surgical procedure with an insulated blanket; and using a warm air blanket (Bair Hugger, Arizant Healthcare, Inc.) on areas not involved in the surgical procedure. Heat lamps are not recommended because they can cause thermal burns, especially in an anesthetized animal that cannot respond to painful, concentrated heat. It must be remembered that electric heating pads should never be used to warm anesthetized animals. Electric heating pads concentrate heat and cause thermal burns (Figure 30-2). The veterinarian is liable for burns caused by electric heat units because it is a known cause of thermal skin injury during anesthesia.

FIGURE 30-1 One method of heat retention during surgery is to wrap the animal in plastic. This works well for small dogs and cats.

FIGURE 30-2 The area of denuded skin over the rump of this dog is a result of a thermal burn sustained from an electric heating pad used to maintain body temperature during ovariohysterectomy.

After surgery, the animal is placed in a warm area to recover with a heated circulating water blanket. If the patient is severely hypothermic, a warm air blanket and/or warm water bath can be used to raise the temperature quickly (Figure 30-3). A warm water bath is made by filling a large, deep pan, big enough to place the entire animal in, three-fourths full with warm water, placing a thick garbage bag over the pan and water, and placing a towel over the garbage bag where the animal is to be placed (similar to a heated water bed). The animal is placed in the water bath allowing the warm water to “wrap” around the animal; the plastic prevents soaking. The animal must be monitored closely to prevent accidental puncture of the plastic and drowning (Figure 30-4). Only small dogs and cats can be warmed in this way.

FIGURE 30-3 Blankets that blow warm air and warm water baths can be used to bring the body temperature up quickly. Notice the dog placed under the blue hot air blanket in a well-constructed water bath.

FIGURE 30-4 This is a close-up of a water bath. A large container is filled with warm water and covered with thick plastic and a towel. The dog or cat is placed on the towel in the container and is allowed to sink down into the warm water with the plastic preventing soaking. The animal must be monitored carefully to prevent accidental puncture of the plastic and drowning.

Body temperature should show a steady rise as the animal recovers. When the animal’s temperature approaches 100° F, heating sources can be discontinued, but the animal should be kept covered, and body temperature should be reevaluated periodically to ensure that it returns to and remains normal. If the temperature remains low or continues to fall, it may be an indication of a potential problem, and the veterinarian in charge should be alerted. Heat should be reapplied if the animal’s body temperature begins to drop after heat sources are removed.

PAIN

Intraoperative and postoperative pain assessment is important for animal well-being and health. During surgery, increases in heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure and lightening of the anesthetic plane can indicate that the animal is in pain. During recovery, animals that are in pain, among other things, may vocalize, have elevated heart and respiratory rates, thrash, bite or chew at the surgery site, and/or become aggressive. Other signs of pain include a disinterest in the environment, crying upon manipulation, insomnia, and lack of appetite (Figure 30-5). It should be remembered that changes in vital signs can mean numerous things (e.g., elevated heart rate could also signify substantial blood loss). The animal should be carefully evaluated by the technician and surgeon before drug administration. It is best not to allow the animal to experience pain before giving pain medication. If an incision was made, pain is going to be experienced by the animal. It is up to the veterinary technician and surgeon to decide how much pain a particular procedure might cause. Painful procedures include fracture repair, amputation, declaw, joint surgery, and any major abdominal procedure. Moderately painful procedures include minor abdominal procedures (spay, cystotomy) and simple body wall hernia repair. Mildly painful procedures might include simple mass removal or biopsy. It can be difficult to determine how much pain an animal is in because animals respond so differently to pain. Some animals may act as if in pain after spay, whereas others may not, even though they are both likely experiencing pain. When in doubt, it should be assumed that the animal is having some degree of postoperative discomfort.

FIGURE 30-5 Note how the dog in (A) does not turn to face the door even when it is opened. Also note the full food dish in the front of the cage. This is a dog suffering from severe spinal pain and is uninterested in her environment. Comfortable animals are often interested in their surroundings and will come to the cage door to greet you. In spite of her tibia fracture, the dog in (B) is more than willing to interact with those around her.

Pain treatment is accomplished in several ways, and it depends on the animal, availability of pain medications, and the type of procedure that was performed as to what sort of regimen is chosen. Most soft tissue surgical pain will last 4 to 5 days after surgery. For bone and joint procedures, this should be extended another 4 to 5 days. It is best to preemptively manage pain rather than wait for the animal to show pain before administration of pain medication. If the animal is allowed to experience pain before administration of pain medication, then the pain is harder to treat and may not be relieved by the medication administered (see Chapter 26). Pain medication should be administered before surgery in the premedicants, and they should be continued throughout the surgical procedure and into the postoperative period according to the dosing regimen for the particular drug used. A wait-and-see attitude should never be adopted because this allows the animal to experience pain before treatment is given.

Another misconception is that animals will stay quiet and calm if they are in pain, so avoidance of pain medication is a form of treatment. You would never be treated that way in a hospital, and animals should not be treated that way. This is an ethical dilemma many veterinarians and technicians must face. An appropriately managed animal will likely sleep for several hours after surgery, should be comfortable when manipulated, should be alert and interested in its environment when aroused, and will likely be willing to eat and drink.

INCISION EVALUATION

Visual and palpable inspection of the surgical wound should be made daily (see Chapter 34 for detailed information on wounds and healing). The surgical incision is usually left uncovered after surgery. Ointments and creams (even antibiotic topicals) should not be placed on the incision because this can cause irritation, and components of the ointment can delay wound healing. The incision can be covered with an adhesive or a wrap bandage for the first few days after surgery to keep the incision clean, prevent contact with the hospital environment, and absorb seepage.

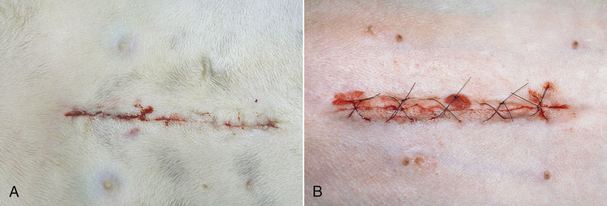

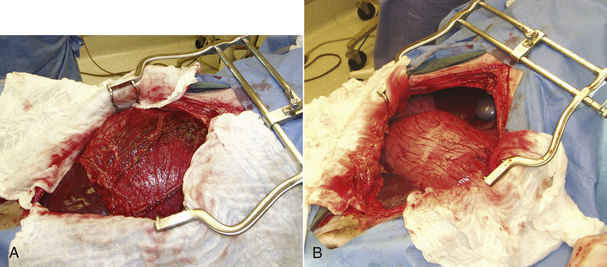

Abnormalities that can occur in the early postoperative period (1 to 3 days) include redness, swelling, drainage, and dehiscence (wound breakdown). An incision should be evaluated with respect to the type of surgical procedure performed. Elective operations, such as ovariohysterectomy and castration, can be expected to produce mild redness and swelling with no drainage from the incision site (Figure 30-6). However, if the wound was contaminated (e.g., laceration, perianal wound) or if the surgical exposure was extensive, the incision is expected to be somewhat swollen, reddened, and warm to the touch and have mild to moderate drainage in the first 24 to 48 hours postoperatively (see Figure 30-6). Swelling secondary to surgical trauma will usually resolve within 3 to 7 days after surgery. However, seromas (serum accumulation under the incision) and hematomas (blood accumulation under the incision) may persist for weeks.

FIGURE 30-6 These photographs were taken 4 hours after surgery. A shows a celiotomy incision following routine ovariohysterectomy, whereas B shows a celiotomy incision following severe traction on the skin during surgery for exposure. Note the minimal redness, swelling, and drainage from incision (A) compared with incision (B).

Surprisingly, most animals will not lick or chew at the surgical incision. Animals will usually lick or chew at the incision only if the character of the incision is irritating. Contributors to incision irritation include sutures placed too tight, traumatic tissue handling, suture reaction, tension on the suture line, clipper burn, prepping irritation, incision infection, and seroma formation. Only rarely will an animal chew the sutures because they are bored. Using appropriate suture technique will minimize incision self-trauma. However, if an animal begins to traumatize the incision via licking or scratching, an Elizabethan collar, bandage, neck brace, T-shirt, and/or chemical restraint should be used to protect the incision.

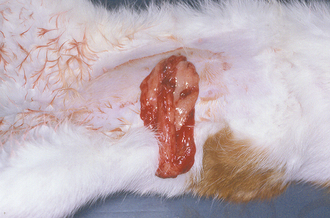

Seromas can form if extensive surgical dissection occurred beneath the incision, tissue planes could not be or were not adequately closed, or excessive motion occurs at the incision site. Seromas are recognized as localized areas of fluctuant swellings that are not usually painful or warm to the touch (Figure 30-7). Seromas will usually resolve without treatment. Warm compresses, hydrotherapy, and bandaging may aid in resolution. If the seroma is large and/or is causing impairment, drainage is warranted. Drainage should be performed aseptically, and an active, closed drain should be placed. It is important to keep animals calm in the postoperative period to decrease the chance of seroma occurrence. Hematomas are treated the same way.

FIGURE 30-7 Note the swelling beneath the incision on cranial thigh of this dog. The swelling was nonpainful, and the dog’s vital signs were normal. The swelling was diagnosed as a seroma.

If incision swelling occurs 4 to 6 days postoperative, is warm to the touch, or is associated with an elevated body temperature, reddened, and/or draining, the possibility of infection or cellulitis (infection along tissue planes) must be considered (Figure 30-8). Abscess or infection or cellulites must be treated by drainage, warm compresses, and systemic antibiotics. Some infected incisions can be flushed and managed with an active, closed suction drain, but others will require open wound management (see Chapter 35 for details on infected and open wound management).

FIGURE 30-8 Incisional infection is recognized by drainage, redness, swelling, fever, dehiscence, and/or abscess formation. Notice the purulent discharge and partial dehiscence of the incision in (A). B shows an abscess that recently ruptured.

Wound dehiscence is defined as the separation of all layers of an incision or wound. Early recognition is imperative in any wound, but especially in abdominal and thoracic incisions. Dehiscence is most often due to technical error in suture technique, but incision complications can also play a role. Things that will contribute to wound dehiscence include using inappropriate suture to close a wound, inappropriate suturing technique, tension on the incision line, incision infection, seroma formation, or disease and/or drug therapy leading to delayed wound healing. Rarely would an animal self-mutilate an incision and cause dehiscence (see previous discussion).

Early detection of surgical incision problems is of paramount importance to help prevent more serious complications. If dehiscence is suspected, the reason for dehiscence should be ascertained. If the external suture layer (skin) is dehiscing and it is only partial, conservative management may be possible. The open portion of the wound will heal by second intention. However, the open wound will likely need to be bandaged and the animal placed in an Elizabethan collar to prevent licking of the open wound and further dehiscence. If the phase of healing is early (first few days after surgery), cleansing and closure of the incision may be necessary depending on the degree of dehiscence. Dehiscence of deeper layers can be more serious and should be brought to the attention of the veterinarian in charge as soon as possible, especially if the incision involves the abdominal or thoracic cavity. Complete dehiscence of an abdominal wound can result in evisceration (exposure) of the abdominal organs, with subsequent contamination and infection (Figure 30-9). Complete dehiscence of a thoracic wound will result in a pneumothorax (air within the chest causing collapse of the lungs), a problem that may result in sudden death.

SUTURE REMOVAL

Suture removal is commonly performed by the veterinary technician. The procedure is usually performed 10 to 14 days after surgery because this is the approximate time that the wound is beginning to strengthen (see Chapter 34). If internal sutures were placed in the dermis with the external skin sutures, external suture removal can be performed in 5 to 7 days because the internal suture layer will hold the incision closed while healing continues. The incision should be inspected carefully for adequate healing before removal. A healed incision is usually confluent, slightly raised, and whitish in color and has no gaps between skin edges (Figure 30-10). An appropriately healed incision should not be draining, severely reddened, or severely swollen. However, if complications were encountered, then some reddening, swelling, and excessive scarring is expected. Incisions that are swollen, draining, reddened, or have obvious separation should be inspected by the veterinarian in charge before suture removal.

FIGURE 30-10 Healed incision. Note that the incision is not red, swollen, or draining. The skin edges are apposed, and the scar is slightly raised. This photo was taken 12 days after surgery.

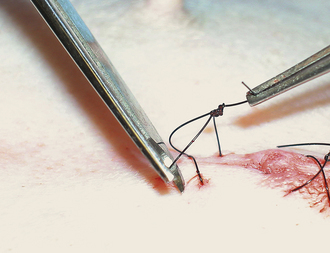

Skin sutures are usually easy to remove in the calm animal. Suture scissors are simple to use and allow removal with minimal discomfort. The suture should be grasped with thumb forceps or your finger. Gentle traction is placed on the suture, and the suture is cut near the skin surface (Figure 30-11). The suture is manually pulled out of the skin after cutting. If metal staples were placed, a staple remover should be used to allow removal with minimal discomfort (Figure 30-12).

BANDAGE CARE

If a bandage was placed, the limb in which the bandage was placed should be monitored carefully. The bandage should be kept clean and dry. A plastic bag or other water-resistant covering should be placed over the bandage when walking the animal outside and removed once back inside. The plastic will prevent the bandage from getting wet, but it should not be left in place because moisture will accumulate under the plastic if left on for extended periods of time. The animal’s toes should be checked twice daily for swelling or coldness as long as a limb bandage is in place. This is especially important immediately after placement. Swollen toes might be an indication the bandage is too tight. If the bandage gets wet, dirty, has an odor, or the toes become swollen or cold, it should be changed. A soiled, wet bandage can lead to sore formation and incision infection. Bandages placed too tight can result in vascular compromise to the skin with death and sloughing. Bandages are changed at intervals designated by the veterinarian in charge and depending on the reason for placement. Bandages covering open wounds will have to be changed daily. Some wounds drain excessively, causing serum to seep through the bandage and extend to the external environment. This is called strike-through (Figure 30-13). Strike-through must be prevented to help prevent wound infection. The bandage must be changed multiple times a day under such circumstances (see Chapter 34 for information on bandaging wounds).

DRAIN CARE

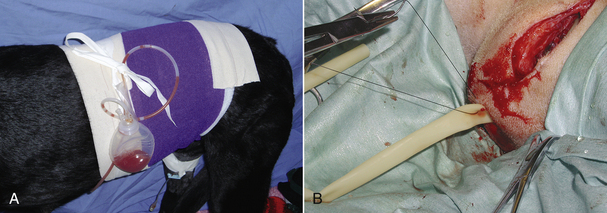

Drains are placed to collect fluid under a wound (surgical incision). They are often placed when large amounts of tissue are resected (mammary chains, amputation, large skin masses) or when a large amount of drainage is expected (a contaminated or infected wound). If a drain is placed, the drain exit site should be kept covered with a bandage. Additionally the animal should be placed in an Elizabethan collar to prevent premature removal or drain breakage by the animal. Active drains (drains that are sealed to the environment and actively collect fluid from the wound into a reservoir) should be emptied as needed (Figure 30-14). Passive drains (drains that provide an exit port for fluid to the external environment) should be avoided because of risk of ascending bacterial infection and difficult maintenance as a result of constant drainage of fluid through the drain exit site, though they are placed under some circumstances (see Figure 30-14). If passive drains are used, the bandage should be changed frequently to prevent strike-through. Drains are removed when the amount of drainage has substantially decreased. Some drainage is expected as long as a drain is in place as a result of tissue irritation by the drain, but it should be minimal.

FIGURE 30-14 Drains. A, Active drains actively suck fluid from the wound bed into a sealed reservoir and are preferred over passive drains. B, Passive drains are placed under incisions and just provide surface area for fluid to drain from the wound with gravitational forces. They are more prone to ascending infection and are harder to manage. In photo B the wound is being closed over a rubber drain (yellow). The incision and drain will be bandaged afterward.

RESTRAINT

Animal restraint is important for appropriate surgical technique. Naturally the animal will have to be manually restrained during the preoperative examination and sample collection; however, surgical restraint involves sedation and/or general anesthesia. The type of surgical procedure dictates whether simple sedation or general or local anesthesia will be required. The specifics of anesthetic drug administration are covered in Chapter 27 and should be reviewed. Appropriate protocol should be discussed with the surgeon before surgery so that preparation of the animal and the operating room can be initiated.

All animals should be well controlled after surgery to minimize complications. The length and severity of confinement depend on the type of procedure performed. Animals undergoing routine sterilization or simple mass removal usually require 10 to 14 days of restricted activity, whereas animals undergoing orthopedic surgery will likely require 6 to 8 weeks of confinement. No animal should be allowed to roam free immediately after surgery. Additionally, self-trauma should be prevented.

Besides crate, leash, and room confinement, chemical agents and mechanical devices can also be used for restraint. Tranquilizers and noxious-tasting substances are commonly used chemical restraints. Tranquilizers must be used with caution because they can have undesirable side effects. They are not meant to be used long term. Phenothiazine derivatives (acepromazine) are commonly used tranquilizers in veterinary medicine, but α2-adrenergic agonists, benzodiazepines, and cyclohexamines are also used (see Chapter 27 for more information on drugs used for sedation). Appropriate crate or room confinement usually will suffice without the addition of tranquilization.

Noxious-tasting agents are used to prevent animals from licking or chewing, and they must also be used with discretion. Some commonly used substances include Bandguard Cream (Schering-Plough), Bitter Apple (Grannick’s), Tabasco, and various thumb-sucking preparations. The agent can be impregnated into bandage material, and some can be placed directly on the skin around the incision. These agents should never be placed directly on the incision because they can burn, irritate the incision, and have the potential to delay wound healing.

Mechanical restraint devices include the Elizabethan collar, the body brace, the side bar, hobbles, and various bandages. These devices are used to limit motion, prevent licking and chewing, and prevent weight bearing. The assembly, materials necessary, specific indications, contraindications, and complications have been adequately described elsewhere (see Chapter 34 and Recommended Reading) and are beyond the scope of this chapter. A properly selected, constructed, and applied device will be well tolerated by the animal and effective for its desired purpose.

COMMON SURGICAL PROCEDURES

The veterinary technician must have a working knowledge of common surgical procedures to properly prepare an animal preoperatively, act as an efficient surgical assistant, and manage the immediate and long-term postoperative care. The remainder of this chapter reviews common small animal surgical procedures performed in veterinary practice. A brief description of the procedure, with emphasis on the role of the veterinary technician, will be given.

ELECTIVE VERSUS NONELECTIVE SURGERY

Surgical procedures are divided into elective and nonelective. Elective procedures are performed at the veterinarian and owner’s convenience, usually in healthy animals. Spay, castration, and declaw are examples of such procedures. Some procedures must be done to improve the animal’s quality of life, but are not necessarily urgent, such as stifle stabilization for cranial cruciate ligament rupture, correction of patella luxation, and cancer resection. For these procedures, if animals are not ideal candidates for surgery at the time of presentation, surgery can be delayed. However, ideally, surgery would be performed at some point to alleviate the animal’s clinical signs or to decrease the chance of tumor spread. Nonelective surgical procedures must be done urgently. These are usually emergency procedures performed on compromised animals.

TAIL DOCKING ON PUPPIES

INDICATIONS

Tail docking in young puppies is specifically performed for aesthetic reasons. Dog breeders have traditionally developed breed standards by alteration of the breed character with surgery. Tails are docked according to breed standards set forth by the American Kennel Club.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The dam can get upset as puppies are removed from her presence for the procedure. Some dams will even become aggressive. Care must be taken with removal and replacement of the puppies from the nest. If the dam becomes too upset, it may be necessary to place her in another room while the procedure is performed on the puppies. Alternatively, some dams are more comfortable in the same room with the puppies.

Tail docking should be performed during the first week of life (3 to 5 days of age). At this age, the procedure can be performed without general anesthesia and is minimally traumatic to the dam and puppies. It must be remembered that puppies of this age are immunogenetically naive. It is important to perform the procedure in an area where the puppies will not be exposed to a high concentration of infectious agents.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The puppy should be cradled in the palm of both hands with the hind limbs held between the index and middle fingers and the tail directed toward the surgeon. The surgical site is prepared using aseptic technique. The desired length of remaining tail is marked, and the skin of the tail is retracted craniad (toward the base of the tail). The tail is amputated with a pair of scissors, bleeding is controlled with electrocautery or pressure, and the skin is released, allowing it to retract over the exposed bone. One simple interrupted absorbable suture is placed to appose the skin edges, or the edges are glued with a tissue adhesive. If a surgical laser is used to remove the claws, the technician should ensure that the appropriate equipment and eye protection is available for the surgical team and that the surgery site is not prepared with alcohol. Furthermore, the technician must also be available to vacuum the emitted smoke from the laser because this smoke is harmful to people and animals.

POSTOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The puppies should be returned to the mother as soon as hemorrhage is controlled. The surgical site should be monitored for the first few hours for excessive bleeding. During the week following surgery, the tail should be monitored for drainage, redness, and swelling daily. The suture remains until it is absorbed or licked out by the mother. Complications are not expected following tail docking, but may include hemorrhage and infection. In some animals, too much skin is removed during the amputation. Those animals may have chronic wound healing problems and bone exposure at the amputation site. Revision of the surgery site may be necessary to correct the problem.

DEWCLAW REMOVAL ON PUPPIES

The claws located on the medial aspect of the forelegs and hind limbs are known as dewclaws. Dewclaw removal is amputation of the claw.

INDICATIONS

Dewclaws are commonly removed from the forefeet and hind feet of purebred dogs for aesthetic reasons and from hunting dogs because they may be torn as the dog runs over terrain densely covered with shrubs. It should be remembered that in certain breeds (e.g., Great Pyrenees, Newfoundland) the presence of dewclaws is necessary for proper show quality.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The preoperative considerations are the same as those described earlier.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Dewclaws should be removed during the first week of life (3 to 5 days). Removal is generally performed at the same time as tail docking in most breeds. The surgical site is prepared aseptically. The puppy is cradled in the palm of one hand, and the extremity is extended with the other hand. Scissors are used to amputate the claw. Hemorrhage is controlled with electrocautery or pressure. The skin edges may be left to heal by second intention or apposed with one absorbable suture.

POSTOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The puppies are returned to the mother immediately. The surgical site should be monitored for the first few hours for excessive bleeding. During the week following surgery, the amputation site should be monitored for drainage, redness, and swelling daily. Complications are not expected following dewclaw removal, but may include hemorrhage and infection.

TAIL DOCKING AND DEWCLAW REMOVAL IN THE ADULT

Tail docking and dewclaw removal should ideally be done within the first week of life if it is performed for aesthetic purposes. In some instances, adult dogs are seen for one or both procedures.

INDICATIONS

Indications for tail docking or dewclaw removal in the adult dog include aesthetics, trauma, infection, and neoplasia.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

One must consider the reason for tail or claw amputation before animal prepping and initiation of the procedure. If it is done to treat cancer, acceptable tumor-free margins should be taken with the removed tissue, and the appropriate amount of skin must be prepared before surgery. Removed tissues will have to be placed in formalin at a 1:10 ratio for eventual histopathologic evaluation. If trauma is the reason for the procedure, the animal may have to be stabilized before surgery can safely be performed. If amputation is performed as a treatment for infection, the veterinary technician should have culture swabs available so that the veterinarian can obtain appropriate cultures at the time of surgery.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS FOR DEWCLAW REMOVAL

The animal must be placed under general anesthesia. The surgical site is clipped and prepared using aseptic technique. The surgeon will make an elliptical incision at the base of the dewclaw. The dewclaw is dissected free and is transected at the carpometacarpal joint in the front paw or the tarsometatarsal joint in the hind paw. Hemorrhage is controlled with suture, electrocautery, laser, and/or direct pressure. If a surgical laser is used to remove the claws, the technician should ensure that the appropriate equipment and eye protection is available for the surgical team and that the surgery site is not prepared with alcohol. Furthermore, the technician must also be available to vacuum the emitted smoke from the laser because this smoke is harmful to people and animals. The skin edges are apposed with suture. The paw is usually bandaged to prevent swelling and self-trauma.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS FOR TAIL AMPUTATION

The tail should be clipped and hung from an intravenous stand. The skin should be prepared using aseptic technique. If the tail is to be amputated near the base, the rump adjacent to the tail base must also be clipped and aseptically prepared. A tourniquet may be placed at the base of the tail to help control hemorrhage and is placed before the animal is draped for surgery. The tail is amputated at the desired location by skin incision and disarticulation of the caudal vertebra at the appropriate site. The skin incision is made 1 or 2 cm distal to the expected amputation site to ensure adequate skin coverage of the stump. Blood vessels are identified and ligated. The skin edges are sutured over the remaining vertebrae, and the tourniquet is removed.

POSTOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

The surgical sites should be monitored for hemorrhage, swelling, drainage, redness, evidence of self-trauma, and dehiscence. Elizabethan collars should be placed on those animals attempting to traumatize the surgical site. Bandages placed on the foot should be maintained as previously discussed. If placed, skin sutures are removed in 10 to 14 days. Pain medication is generally needed for 4 to 5 days following the procedure. Complications are rare for these procedures, even in adult animals.

FELINE ONYCHECTOMY

INDICATIONS

Onychectomy is an elective procedure to prevent scratching of owners and household items. Most veterinarians recommend declawing the front feet only. This does not significantly impair the cat’s ability to climb trees or defend itself from intruders. Onychectomy is often performed at the same time as castration or ovariohysterectomy.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Onychectomy is a painful procedure. Preoperative analgesics should be administered.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

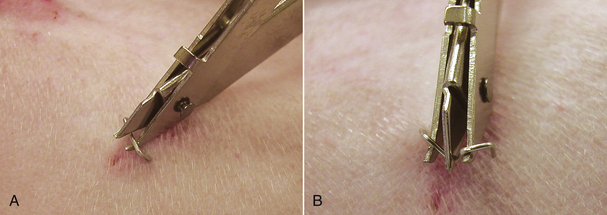

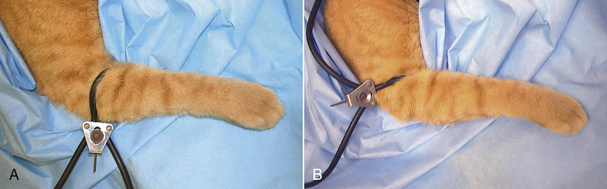

The cat is placed under general anesthesia. The feet are surgically scrubbed, but need not be clipped unless the cat is a long-haired breed. If a laser is to be used during the procedure, alcohol should not be used to prepare the toes because it is flammable and likely to ignite when the laser beam strikes the soaked area. The nails are left long to aid in nail manipulation during the procedure (Figure 30-15). A tourniquet is usually placed to control hemorrhage during the procedure. It should be placed over the foot before aseptic preparation, but tightened when the surgeon is ready to perform the procedure. The tourniquet should always be placed distal to the elbow to prevent nerve damage (Figure 30-16). The radial nerve is more superficial just proximal to the elbow and can be permanently damaged if the tourniquet is tightened over that area (see Figure 30-16). The tourniquet should only remain in place for no more than 1.5 hours. The veterinarian should be alerted as that time approaches so the tourniquet can be removed.

FIGURE 30-16 Declaw. A tourniquet should always be placed, distal to the elbow (A) rather than proximal to the elbow (B) to help prevent permanent radial nerve damage.

Three techniques can be used to remove the claws. The Rescoe (nail trimmer technique), scalpel blade, and the CO2 laser techniques are all effective means to perform the procedure. For the Rescoe technique, a Rescoe nail trimmer is positioned snugly onto the dorsal surface of the toe between the second phalanx and third phalanx. During positioning of the nail trimmer, the claw should be pulled cranially. As little skin as possible should be excised. The cutting edge of the Rescoe nail trimmer is positioned at the cranial edge of the footpad. As the cutting edge is advanced, the pad is moved caudally while rotating the nail dorsally and caudally. The third phalanx is then excised by the Rescoe nail trimmer. Care is taken to prevent cutting the footpad. Each nail is amputated in a similar fashion. A portion of the third phalanx is usually left behind with this technique, but the entire germinal layer is removed to prevent regrowth of the nail. The blade technique amputates the entire third phalanx using a No. 12 scalpel blade. The phalanx is disarticulated dorsolaterally, first by cutting through the collateral ligaments, then the nail is cut away from the underlying tissue and digital pad. The pad is moved out of the way while the nail is removed to prevent inadvertent laceration.

The laser technique is similar to the blade technique except that it uses laser energy to dissect the third phalanx free from the second phalanx instead of a sharp edge. The surgical site usually does not bleed with the laser technique, so a tourniquet is not necessary. If a laser is used, the technician should ensure that plenty of saline-soaked sponges are available to cover the remainder of the cat’s foot, instruments, and surgeon’s fingers to absorb extraneous laser energy and prevent iatrogenic laser burns. It is best to use instruments approved for laser surgery to prevent reflected laser beams from inappropriately penetrating objects and tissues. Everyone in the room should wear safety glasses to prevent inadvertent ocular damage, and the technician should be available to vacuum emitted smoke during the procedure. The technician should be familiar with laser safety before its use.

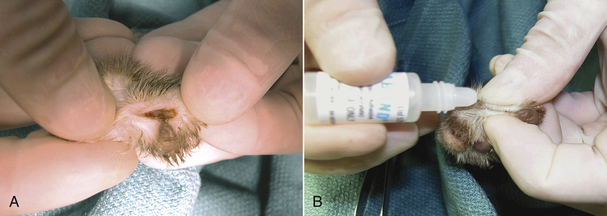

One to two sutures are often placed to appose the skin edges after nail removal. Surgical glue (cyanoacrylic tissue adhesive) is used instead of sutures in some instances. If surgical glue is used, it should never be placed on the exposed bone of the second phalanx or dropped inside the void (wound) created by removal of the third phalanx (Figure 30-17). Instead, the wound should be manually closed and a drop of glue placed only on the skin edges of the closed wound (see Figure 30-17). Dropping glue into the wound can cause chronic lameness and foreign body reaction. Some veterinarians do not appose the skin edges with anything other than a bandage.

FIGURE 30-17 Declaw. A, When applying tissue adhesive to a wound, the glue should never be placed inside the wound created from removing the claw. B, The wound should be manually apposed and the glue placed along the skin edges.

After surgery, the paws are bandaged snugly with a gauze sponge and strips of tape. The sponge is placed over the ends of the digits. Strips of tape are placed longitudinally along the leg and distally around the paw. Tape is then placed circumferentially around the paw up to the elbow. Care is taken to lay tape on the leg and not to pull too tightly. Bandages placed too tight can result in vascular compromise to the foot with skin sloughing. The tourniquet is removed as soon as bandaging is complete.

POSTOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Onychectomy is painful. Pain medication should be administered to all cats in the postoperative period. It is appropriate to administer a pure opioid agonist for the first 24 hours after surgery (see Chapter 26 for details on the administration, advantages, and disadvantages of specific pain medications). A fentanyl patch can be placed the day before surgery to allow the fentanyl to take effect and can last up to 3 days postoperative, but pain control can be variable with the patch, and the cat should be monitored closely for continued pain in spite of having a patch in place. Alternatively, injectable pain medication can be given intermittently. Some nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs can also be used in cats; however, care must be taken to avoid overdosage. A wait-and-see attitude regarding pain medication for this procedure is not acceptable. Instead, medication should be given at the appropriate dosing intervals for at least 4 to 5 days postoperative.

The bandages are kept on for 24 hours, but no longer, and the cat should be hospitalized while the bandage is in place. After surgery, litter should consist of shredded paper or pellets to prevent accumulation of clay or sand in the surgical wounds with resultant irritation and infection. Normal litter should not be reintroduced until 10 days after surgery. The paws should be monitored for hemorrhage, swelling, drainage, and redness. Cats will be fairly sensitive on the front legs after surgery, but this should start improving within 2 weeks of surgery. If sutures were placed, suture removal is generally not necessary because the cats will remove them on their own, but if they are still present after 2½ weeks, the owner should have them removed by the veterinary staff.

Most cats allow removal of the bandages by carefully cutting the bandage apart longitudinally and gently peeling it off the leg. If the cat is intractable, the bandage may be cut and the cat returned to its cage. The cat will then remove the bandage on its own. If this technique is used; however, the cat will have to be monitored to ensure that bandage ingestion does not occur. In severely intractable patients, a light dose of a tranquilizer may be necessary to remove the bandages safely. Cats are monitored carefully for 8 to 12 hours after bandage removal for hemorrhage. Rebandage with prolonged hospitalization will be necessary if hemorrhage occurs.

Onychectomy complications can be divided into those that occur in the early postoperative period and those that occur in the late postoperative period. Early complications include loose bandages and postoperative bleeding. Cats should be checked frequently for evidence of loose, bloody bandages or complete bandage removal and severe hemorrhage. In the event of hemorrhage, the paws should be rebandaged snugly. Infection can also occur and generally becomes evident within the first 3 weeks of surgery. Infection requires antibiotic therapy and/or wound débridement. Late complications include regrowth of the claws, chronic lameness, or both. Claw regrowth requires reoperation and removal of remaining germinal epithelium. Chronic lameness without evidence of regrowth may be seen with incomplete removal of the phalanx or cut footpads. For this reason, it is essential that the pads be preserved during the operative procedure. Other complications include radial nerve damage secondary to tourniquet placement and skin sloughing secondary to tight, prolonged bandage placement.

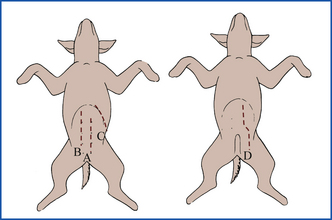

CELIOTOMY

Celiotomy (laparotomy) is a surgical incision into the abdominal cavity. There are several locations in which the incision can be made: ventral midline, paramedian, paracostal, parapreputial, and flank (Figure 30-18). The most commonly used incision site is ventral midline.

INDICATIONS

A celiotomy is performed for both elective and nonelective procedures. Some of the common elective procedures include ovariohysterectomy, organ biopsy, cystotomy, planned cesarean delivery, gastropexy, and retained abdominal testicles. Some common nonelective procedures include emergency cesarean delivery, gastric dilation-volvulus (GDV) (bloated, twisted stomach), intussusception, gastrointestinal foreign bodies, ruptured spleen, penetrating foreign bodies (e.g., knife wound, arrow wound, bullet wound), severe abdominal bleeding, and diaphragmatic hernia. In some instances, the animal is seen for an unknown abdominal problem. These patients may need elective or nonelective celiotomy, referred to as an exploratory celiotomy. Exploratory celiotomy is often performed for abdominal masses of unknown origin and to obtain biopsies for disease diagnosis.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Animals should always be clipped widely for abdominal incisions. At times, the incision must be extended, and an inappropriate prep will hinder surgical exposure. Animals undergoing abdominal incision because of illness or trauma may have to be stabilized before anesthesia is administered. If biopsies or cultures are to be taken, the veterinary technician should make sure that culture supplies and tissue sample cups with formalin are available.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

For ventral midline celiotomy, the patient is placed in dorsal recumbency. Larger dogs should be placed in a V-trough to help stabilize them in that position (Figure 30-19). Smaller dogs and cats can be placed on moldable beanbags or between sandbags. The abdomen is widely clipped from 2 cm cranial to the xiphoid cartilage to 2 cm caudal to the pubis. The skin is aseptically prepared for surgery.

FIGURE 30-19 V-trough is used to stabilize large animals in dorsal recumbency for surgical preparation. A, Trough. B, Proper positioning.

The various incisions (paramedian, paracostal, etc.) are all slight variations of the ventral midline incision and are less commonly used (see Figure 30-18). For this reason, emphasis will be given to the ventral midline incision.

The line of the incision is from the xiphoid process to the pubis. The length used varies with the type of procedure (see specific procedures). A surgical sponge count is performed before entry into the abdominal cavity. The incision is made with a scalpel blade or electrocautery in the cutting mode. The incision is carried through the subcutaneous tissue to the level of the linea alba, which is elevated with forceps to pull it away from the underlying abdominal viscera. This will prevent the inadvertent puncture of abdominal organs when entering the peritoneal cavity. A scalpel blade is used to penetrate the linea alba and enter the peritoneal cavity. The incision is extended the desired length with scissors or scalpel blade and forceps. Moistened laparotomy pads (sponges) are placed along the incision edges for protection during exploratory surgery. This is usually not necessary during ovariohysterectomy because the incision is small and manipulation is minimal. A Balfour self-retaining abdominal retractor can be introduced, if necessary, into the incision to facilitate visualization of abdominal structures (exploratory celiotomy). Surgical lights and air exposure of abdominal organs will quickly dry out abdominal structures. It is important for the surgical assistant to keep exposed tissues moist to prevent damage and decrease adhesion formation. The technician should pay special attention to viscera moved external to the abdominal cavity. Viscera temporarily moved outside of the abdominal cavity should be covered with warm, moist laparotomy pads. Abdominal viscera should be handled carefully and as little as possible. Whenever retraction or manipulation of structures is necessary, atraumatic technique is mandatory. Retract viscera with moistened laparotomy pads, manipulate viscera with moistened gloves, blot any excess hemorrhage with moistened sponges (do not wipe surfaces with sponges), and when using suction, be careful not to suck the walls of visceral structures against the suction orifice. A thorough inspection of the abdomen is performed. A postoperative sponge count should be made before closing the abdomen to ensure that all sponges are accounted for.

The abdomen is sutured closed in three layers. The linea alba is the layer of strength and must be securely closed. The subcutaneous tissues are then sutured to decrease the amount of dead space. This helps reduce the frequency of postoperative hematoma or seroma formation. The skin is sutured to complete the celiotomy closure.

POSTOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

During the first 24 hours, the skin incision should be examined carefully for swelling, drainage, excessive redness, dehiscence, and evidence of self-trauma. An Elizabethan collar should be considered if the animal appears to lick or chew the incision. Incision problems should be brought to the attention of the veterinarian. Incision monitoring should be continued for 2 weeks after surgery or until suture removal. Animals should be exercise restricted until the abdominal wound is healed. If there is evidence of dehiscence, the veterinary technician should notify the veterinarian immediately. Emergency closure may be necessary.

Some animals may be inappetent or vomit after celiotomy. Intestinal and pancreatic manipulation can lead to intestinal ileus (temporary loss of intestinal motility), nausea, and/or pancreatitis. One or two episodes of vomiting or lack of appetite for the first 24 to 48 hours after celiotomy is usually not concerning in and of itself. However, if the animal appears ill or vomiting and inappetence continues, further evaluation should be performed. Animals not eating or drinking after surgery should be supported with intravenous fluid therapy until oral alimentation is resumed.

GASTROINTESTINAL SURGERY

Gastrotomy is incision (opening) into the stomach. Enterotomy is incision into the intestine. These are often done to obtain biopsies or to retrieve foreign material. Anastomosis is suturing portions of the gastrointestinal tract together to allow confluent ingesta flow. Anastomosis is performed after damaged tissue or tumor requires a segment of the gastrointestinal tract to be removed.

INDICATIONS

Gastrointestinal surgery has many indications. Gastrointestinal foreign body lodgment, neoplasia, biopsy for vomiting or diarrhea of unknown origin, GDV, gastrointestinal trauma, and gastrointestinal obstruction of unknown cause can all be reasons for abdominal exploration and gastrointestinal surgery.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Many animals undergoing gastrointestinal surgery have usually been recently vomiting or not eating for several days. The veterinary technician should stabilize the animal with appropriate fluid management to correct dehydration before surgery. The animal should be intubated as soon as possible with a cuffed endotracheal tube to help ward off aspiration of stomach contents should the animal vomit during induction. The veterinary technician should make sure that extra instruments are available in case the primary pack is contaminated with intestinal contents during the procedure. Prophylactic antibiotics are used if the gastrointestinal tract is to be entered.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

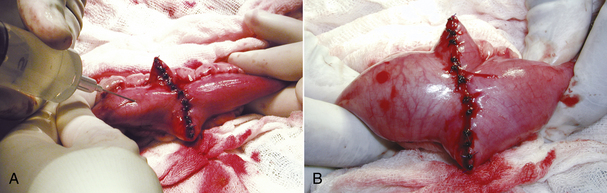

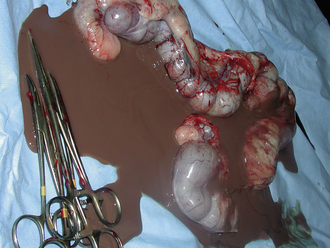

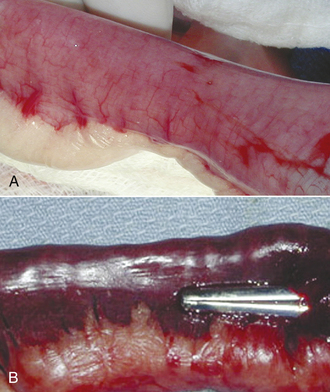

The animal is prepared for a full midline celiotomy (see Figure 30-18). An abdominal exploration is performed. Abnormalities are noted. Foreign bodies leading to gastrointestinal obstruction are removed via gastrotomy or enterotomy. The normal gastrointestinal tract is pink, has visible vasculature on the surface, and has active motility. In some instances, devitalized tissue must be removed via resection and anastomosis. Devitalized intestine is discolored and lacks blood supply. Purple and red discoloration does not necessarily imply devitalization; blood supply must be evaluated by direct visualization of cut sections, Doppler, or injection of vital stains. If the tissue is questionable, it should be resected (Figure 30-20).

FIGURE 30-20 The normal intestine is pink with visible vessels and motility. Note the difference in color of the normal intestine (A) with the devitalized segment of bowel (B).

Characteristics of intestinal devitalization are:

• Severe thinning of the visceral wall

• Lack of bleeding on cut section

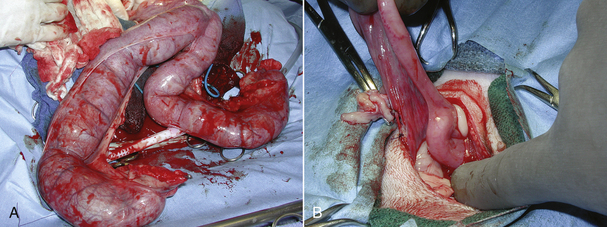

For biopsy or foreign body removal, the affected portion of the gastrointestinal track is isolated with laparotomy pads (Figure 30-21). Laparotomy pads are placed to prevent intestinal contents from leaking into the abdomen if accidental spillage occurs. Stay sutures are placed to steady the tissue on either side of the incision. Biopsy is performed by making a stab incision into the stomach or intestine between the stay sutures and removing a full-thickness portion of the tissue with a blade or scissors. If the incision is made simply to remove intraluminal material, the stab incision is extended enough to remove the material, and no tissue is removed for biopsy. The incision is closed in an interrupted pattern with absorbable, monofilament suture.

FIGURE 30-21 If a biopsy is to be performed on the gastrointestinal tract, the segment is packed off with laparotomy pads to prevent leaking ingesta from contaminating the abdominal cavity. Note the white pads surrounding the intestine. Ingesta is prevented from leaking from the cut surface of the intestine by placement of intestinal clamps or having an assistant gently pinch off the intestinal lumen on either side of the incision with fingers.

If a resection and anastomosis is to be performed, the vasculature to the portion of the intestine to be removed is ligated; the intestines are clamped with Doyen forceps, or the surgical assistant supports the intestines with fingers to prevent ingesta from leaking onto the surgical field (see Figure 30-21); the portion of the intestines to be removed is excised; and the viable intestinal ends are sutured together in an interrupted pattern similar to a biopsy site. After completion of the anastomosis, the intestine is evaluated for leakage. This is accomplished by occluding the intestine on either side of the anastomosis site and filling the enclosed space with sterile saline using a syringe and small-gauge needle. The surgeon and assistant check for leaks along the incision. Leaks are sealed with additional suture (Figure 30-22). The intestine is flushed, and the laparotomy pads are removed from the abdomen and surgical field, being careful not to contaminate the rest of the abdomen or the surgical field with ingesta that might have leaked onto the pads. The technician should ensure that warm isotonic saline is available for flushing the abdominal cavity. Omentum is placed over the incision, and the abdomen is flushed. The celiotomy is closed routinely. Many surgeons will ask for a clean surgical pack, gloves, and drape to perform the celiotomy closure to prevent contamination of the celiotomy wound with ingesta from instruments used during the intestinal procedure.

POSTOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Careful patient monitoring is important following intestinal surgery. The main consideration is evaluation for intestinal leakage. If intestinal dehiscence or leakage occurs, septic peritonitis is likely to follow. Animals should be monitored for inappetence, vomiting, fever, painful abdomen, abdominal enlargement, incision drainage, and shock, which are all potential indicators of peritonitis. Most animals are willing to eat within 24 hours of intestinal surgery. Minor vomiting (one to two times) might be expected. However, protracted vomiting and inappetence should alert the technician to a potential impending problem with the intestinal surgery site. If intestinal leakage is suspected, abdominocentesis is performed. Material collected is evaluated for cell population and bacteria. If enough material is not obtained for evaluation from simple abdominocentesis, but leakage is still suspected, a diagnostic peritoneal lavage should be performed. A septic abdominal tap warrants abdominal exploration and correction of the problem.

Feeding animals after intestinal surgery is also a consideration. The gastrointestinal tract requires food for cellular health and proper function. Intestinal surgery can result in ileus and may cause inappetence, nausea, and vomiting. However, animals without complications are most often willing to eat within 24 hours. Unless the animal is vomiting, oral alimentation should be initiated as soon as the animal has an appetite. Animals should be introduced to water first. If no vomiting occurs after water intake, then food is introduced. A small amount of highly digestible, bland food should be fed initially (e.g., 1 to 2 tbsp of Hill’s Science Diet I/D). If no vomiting occurs over 2 to 4 hours, another small amount can be fed. If vomiting does not occur, the amount fed can be gradually increased and frequency decreased. Animals are reintroduced to their normal or another maintenance diet gradually after recovery.

Monitoring as discussed for routine celiotomy should also be done.

GASTRIC DILATION-VOLVULUS

Gastric dilation-volvulus is dilation of the stomach with ingesta and gas with rotation of the stomach into an abnormal position. This is a life-threatening condition that typically occurs in deep-chested, large, and giant-breed dogs. The cause is not specifically known, but genetics and chest/abdomen configuration play a role. Some animals have often eaten a large meal, drunk a large portion of water, and/or engaged in heavy exercise following either; however, others have not. Some animals develop the condition during times of stress, such as hospitalization or boarding. Vomiting, retching, and bloating (severe distention of the stomach) are classic clinical signs. Gastropexy is attachment of the stomach to the body wall with the goal of creating a permanent adhesion. It is performed to substantially decrease the chance of stomach rotation, but it does not prevent bloating. Partial gastrectomy is removal of part of the stomach. Splenectomy is removal of the spleen.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

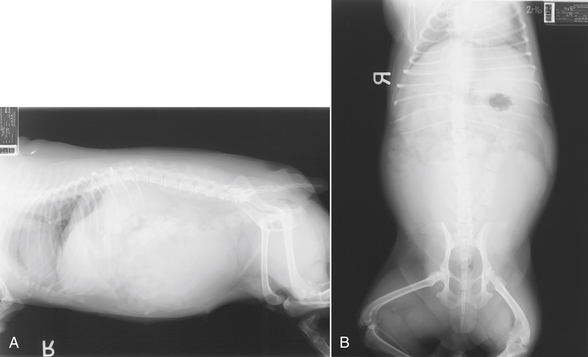

Animals suffering from GDV usually are in shock. If left untreated, these animals will die from cardiovascular collapse. The enlarged stomach compresses the caudal vena cava and affects venous return to the heart. Hypovolemic shock results. Large-bore catheters should be placed immediately. It is important to place the catheters in the front legs or jugular vein because venous return from the caudal half of the body is impaired by the dilated stomach. These dogs are often large and require a substantial amount of fluid. It is best to place at least two catheters. Baseline blood work, ECG, and blood gas should be obtained. The veterinary technician should review treatment of hypovolemic shock (see Chapter 33).

After fluids are started, the stomach must be decompressed to help stabilize the animal and decrease the chance of gastric wall necrosis secondary to vascular compromise from the severe distention. A stomach tube is measured from the nose to the last rib (Figure 30-23). Stomach tubes are large bore and thick. The mouth is held open with a roll of tape or a gag with a hole big enough to pass the tube. An assistant should hold the mouth closed with the gag in place while another person passes the tube (Figure 30-24). The tube is lubricated and gently passed down the esophagus to the stomach up to the premeasured mark. It is difficult to impossible to pass a tube of that size into the trachea, but if the animal begins to cough, the tube should be removed and repassed. It would not be possible to pass the entire measured length of the tube down the trachea without causing severe destruction of the trachea and lungs. Do not forcefully pass the tube if resistance is felt. Overinsertion of the tube may result in gastric rupture if the gastric wall is compromised as a result of vascular impairment. Gas is emptied from the stomach as the tube enters the stomach. Water can be pumped into the stomach to help break up ingesta. If the tube cannot be passed, the animal can be sedated with an opioid and benzodiazepam and another attempt made. The veterinary technician must always remember to pinch off the gastric tube before removing it from the stomach (Figure 30-25). If the tube is not pinched, material from the tube can leak down the trachea as the tube is removed, causing aspiration pneumonia.

FIGURE 30-23 Before passing a stomach tube, the length of tube to be passed is marked by measuring from the nose to the last rib.

FIGURE 30-24 A roll of tape (pictured) or a mouth gag can be used to hold the mouth open while passing a stomach tube. The assistant should hold the mouth gag in place by holding the mouth shut around the gag.

FIGURE 30-25 The assistant passing a stomach tube should pinch the tube off before removing the tube from the animal’s stomach. This helps prevent aspiration of stomach contents into the lungs.

If the tube cannot be passed after sedation, the stomach should be decompressed by trocarization. The disadvantage of trocarization is the potential leakage of gastric contents into the abdominal cavity at the stomach puncture site or stomach rupture. For trocarization, the right side of the stomach is aseptically prepared behind the last rib. A large-bore needle is attached to a 60-ml syringe, a three-way stopcock is gently passed into the dilated stomach percutaneously, and air is aspirated until the stomach is decompressed enough to stabilize the dog.

After stabilization is under way and vital signs are improving, right lateral abdominal radiographs are obtained. This view is best for evaluating whether rotation of the stomach or simple bloat without rotation is present. Thoracic radiographs should also be performed because aspiration is a possibility. As a result of vascular compromise to the stomach wall, the animal should also be started on broad-spectrum antibiotics to help prevent septicemia should intestinal compromise lead to bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract to the bloodstream. The animal is stabilized and prepared for emergency surgery.

Anesthesia can be challenging in these cases. Respiratory compromise is often present as a result of the gas-distended stomach compressing the diaphragm. Blood pressure is often low and difficult to maintain. If possible, an arterial access port should be established for continuous pressure and blood gas monitoring. Additionally, cardiac arrhythmias may also occur and may need to be treated. The veterinary technician should review Chapter 27 for specific anesthetic techniques and monitoring.

TECHNIQUE AND INTRAOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

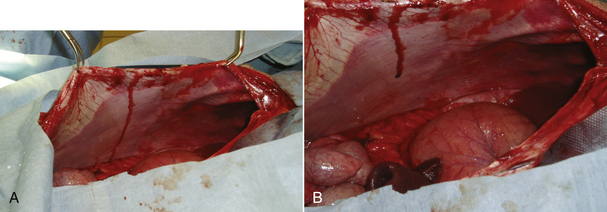

The dog is prepared for a full ventral midline celiotomy. The abdomen is opened carefully to prevent puncture of the stomach because gas distention pushes the stomach against the ventral aspect of the abdomen (Figure 30-26). If the stomach is substantially distended at the time of surgery, further decompression should be performed to make manipulation easier. The veterinary technician should make sure that a stomach tube, bucket, and pump are available in the operating room. The tube should be gently passed down the esophagus after lubrication while the veterinarian manipulates the tube into position within the stomach. The veterinarian can often gently express gas and fluid from the stomach through the tube. If decompression cannot be achieved in this manner, decompression can be performed with a syringe, three-way stopcock, and needle. The stomach must be handled with care. The tissue is often friable as a result of compromise of the tissues. Additionally the ingesta and fluid that accumulates in the stomach following GDV is heavy and can contribute to tissue tearing during manipulation of the stomach back into the normal position. Extreme care must be taken to prevent inadvertent damage. Once the stomach is in its normal position, it is evaluated for viability. The stomach is often discolored at the start of the procedure, but may improve as blood supply and venous drainage returns. A complete abdominal exploratory is performed while circulation is allowed to return to the stomach. The spleen is carefully evaluated. Vascular compromise to the spleen can occur with dilation and rotation of the stomach, or the spleen may rotate. If the spleen is discolored, the vascular pedicle is relieved of compromise, and the spleen is gently placed out of the abdomen and covered with moistened laparotomy pads while a gastropexy is performed. In most instances, the spleen will return to its normal character once blood supply is reestablished. After abdominal exploration, the stomach is reevaluated for viability. Partial resection is performed, if needed.

FIGURE 30-26 A, Note how the dilated, rotated stomach is pressed against the ventral abdominal wall and protrudes out of the abdomen. Inadvertent stomach puncture can occur if the abdomen is not entered carefully. B, The normally positioned stomach is still dilated, but recesses back away from the ventral incision and lies completely within the abdomen.

A gastropexy is then performed on the right ventrolateral aspect of the body wall near the last rib. There are many different techniques for performing gastropexy, and the discussion of each technique is beyond the scope of this chapter. Which technique is used depends on the comfort level and skill of the surgeon performing the procedure. Fixation of the stomach into the celiotomy incision at the time of closure is not recommended because future abdominal surgery can result in accidental perforation of the stomach when the abdominal cavity is entered. The surgical assistant is responsible for retraction of tissues and suture manipulation to keep the procedure running smoothly. It will often help the veterinary surgeon if the assistant stands on the right side of the dog and holds the body wall up with towel clamps during the gastropexy. This will often expose the entire surgical field for the surgeon (Figure 30-27). After gastropexy, the spleen is reevaluated. If all or a portion of the spleen does not appear viable, all or part of the spleen is removed, respectively. The abdomen is flushed, and the celiotomy incision is closed routinely.

POSTOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

Dogs suffering from GDV can have many postoperative complications. Arrhythmias can continue for 2 to 3 days postoperative. Treatment for the arrhythmias should be initiated if vascular compromise is present or is expected based on the abnormality. The veterinarian should be alerted as to the type of arrhythmia present. Hypotension and hypovolemia can continue postoperative and should be treated as needed. Urination should be monitored because prolonged hypotension under anesthesia can affect renal function. A urinary catheter should be placed if urine production is questionable. Some dogs will require a blood transfusion because of hemorrhage associated with tearing of blood vessels during bloating and rotation of the stomach and/or spleen. If a partial gastrectomy was performed, the dogs should be monitored for evidence of gastric wall dehiscence. Some of these dogs continue to develop gastric wall compromise after decompression and surgery. Fever, persistent inappetence, and vomiting may be an indication that this is occurring. Signs are similar to intestinal incision dehiscence as previously discussed. Antibiotics should be continued for at least 7 days postoperative. Immediately after surgery, antibiotics should be given intravenously to avoid oral administration. Gastrointestinal protectants, such as H2 blockers, should also be administered for 3 to 5 days postoperative. Finally, gastric dilation can again occur in the postoperative period necessitating decompression. However, gastropexy should prevent rotation of the stomach.

Oral alimentation should be initiated slowly. Water is given in small amounts to start. If no vomiting occurs, food is gradually introduced. Feeding can start as soon as the animal is willing to eat; this is often within 24 hours of surgery. Some animals may require antiemetics in the perioperative period to help control nausea and vomiting. Long-term dietary management should be considered. When home, these dogs should be on a three- to four-times-a-day feeding schedule. If possible, a three-times-a-day feeding schedule should be continued for the rest of the dog’s life. Water should always be available, but gulping of water should be avoided. Heavy activity should be avoided after feeding. Owners should be warned that bloating can still occur, even though gastropexy was performed, but surgery is likely to prevent gastric rotation, which is more life threatening. Stomach decompression may be needed if bloat is severe.

OVARIOHYSTERECTOMY IN THE DOG AND CAT

INDICATIONS

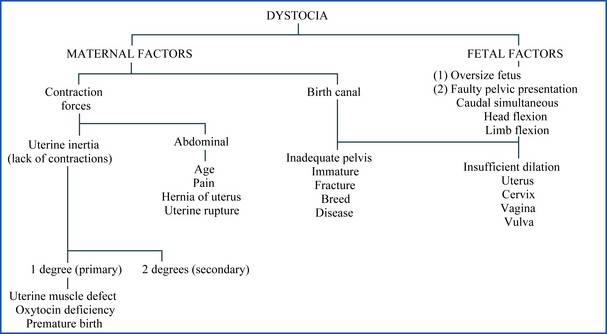

The primary indication for ovariohysterectomy is prevention of pregnancy and subsequent production of unwanted puppies and kittens. Other indications for ovariohysterectomy include endocrine imbalances, infections, injuries, cysts, tumors, prevention of unwanted behavior, and congenital abnormalities. Endocrine disturbances are associated with varied clinical manifestations, such as sterility, skin lesions, mammary tumors, pseudocyesis (false pregnancy), and nymphomania. Ovariohysterectomy before the first estrus will greatly decrease the chance of mammary neoplasia in dogs. Uterine diseases that may require ovariohysterectomy include metritis, pyometra, uterine prolapse, endometrial hyperplasia, neoplasia, injury, neglected dystocia, and congenital abnormalities.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS