chapter 29 Leisure participation after stroke

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

1. Define leisure, types of leisure, and functions of leisure activities.

2. Discuss the changes in an individual’s ability to engage in leisure tasks after a stroke.

3. Describe problems that may interfere with a patient’s participation in leisure tasks.

4. Present possible solutions to these problems.

5. Discuss research addressing leisure participation and occupational therapy interventions after stroke.

6. Outline ways occupational therapists can adapt leisure tasks to allow partial or full participation by someone with a disability caused by a stroke.

Comprehensive stroke rehabilitation must include the consideration of leisure. This is particularly true as there is a renewed focus on decreasing activity limitations and participation restrictions and on improving quality of life as a critical outcome to measure after stroke. Rehabilitation professionals are obligated professionally to address changes in patients’ leisure roles and to use patients’ leisure interests to plan treatment sessions. This area of functioning is critical in the assessment of patients’ motivation, quality of life, and self-esteem. Effective approaches to improving leisure skills and participation usually requires a team approach to meet the complex needs of stroke survivors.

This chapter provides a conceptual framework to help therapists evaluate the leisure skills and improve the leisure participation of patients who have survived a stroke. It focuses on increasing the ability of occupational therapists to improve the leisure skills and the quality of life of this population. Readers are encouraged to review Chapter 3 with this chapter.

Definition of leisure

The Practice Framework1 of the American Occupational Therapy Association includes leisure under the heading Performance in Areas of Occupation. Leisure is described as being “nonobligatory behavior, intrinsically motivated, and engaged in during discretionary time, that is, time not committed to obligatory occupations such as work, self-care, or sleep.”32 The Practice Framework includes the following two subcategories:

1. Leisure exploration: identifying interests, skills, opportunities, and appropriate leisure activities

2. Leisure participation: planning and participating in appropriate leisure activities, maintaining a balance of leisure activities with other areas of occupation, and obtaining, using, and maintaining equipment and supplies as appropriate

The Practice Framework also includes the following related definitions:

Play: “any spontaneous or organized activity that provides enjoyment, entertainment, amusement, or diversion.”32 Play is further broken down into play exploration (identifying appropriate play activities), and play participation defined as “participating in play; maintaining a balance of play with other areas of occupation; and obtaining, using, and maintaining toys, equipment and supplies appropriately.”

Play: “any spontaneous or organized activity that provides enjoyment, entertainment, amusement, or diversion.”32 Play is further broken down into play exploration (identifying appropriate play activities), and play participation defined as “participating in play; maintaining a balance of play with other areas of occupation; and obtaining, using, and maintaining toys, equipment and supplies appropriately.”

Social participation: “organized patterns of behavior that are characteristic and expected of an individual or a given position within a social system.”30 Social participation can include community (engaging in activities that result in successful interaction at the community level), family (engaging in required or desired family roles), and peer/friend (engaging in activities at different levels of intimacy including engaging in sexual activity). See Chapter 25.

Social participation: “organized patterns of behavior that are characteristic and expected of an individual or a given position within a social system.”30 Social participation can include community (engaging in activities that result in successful interaction at the community level), family (engaging in required or desired family roles), and peer/friend (engaging in activities at different levels of intimacy including engaging in sexual activity). See Chapter 25.

Leisure attitude is defined as the expressed amount of affect toward a given leisure-related object. According to Feibel and Springer,14 “this attitude is a multiplicative function of a person’s beliefs that an object has certain characteristics and a personal evaluation of these characteristics.” Many factors affect an individual’s leisure attitudes. These factors include social influences, personality, past experiences, and motivation. Leisure attitudes play an important role in the choice and pursuit of leisure activities. A positive experience during an activity usually results in the person continuing to engage in this pursuit.

A leisure role is defined as a perceived identity associated with a leisure task. Changes in a person’s roles throughout life are accompanied by shifts in leisure participation. Role changes resulting from disability may cause role strain and role conflict: “Role strain refers to the difficulty an individual experiences when attempting to meet role obligations. Role conflict occurs when the occupant of a position perceives that he or she is unable to meet role expectations.”20

Use of time is an important factor in leisure participation. It is well-documented that individuals have impoverished time use after stroke including leisure and social participation. The therapist should analyze the person’s schedule to determine whether intervention is necessary. In an inpatient rehabilitation unit, those with stroke spend more time inactive and alone as compared to those without stroke.6 Additionally, at one month postdischarge, survivors struggle with establishing routines in their day and coping with an increased amount of idle time. Subjects’ strategies for managing increased idle time include “passing time,” “waiting on time,” and “killing time.” 37

Leisure, stroke, and occupational therapy

In their review of the literature regarding the role of occupational therapy and leisure after stroke, Parker, Gladman, and Drummond33 summarized the following:

Stroke survivors often fail to resume full lives, regardless of whether they make a good physical recovery.

Stroke survivors often fail to resume full lives, regardless of whether they make a good physical recovery.

Participation restrictions such as a decline in social and leisure pursuits are prevalent.

Participation restrictions such as a decline in social and leisure pursuits are prevalent.

Customary goals of rehabilitation are focused on mobility and independence in self-care, but recovery in a broader sense may not be maximized if health professionals concentrate exclusively on these goals.

Customary goals of rehabilitation are focused on mobility and independence in self-care, but recovery in a broader sense may not be maximized if health professionals concentrate exclusively on these goals.

Leisure has been shown to be associated closely with life satisfaction and is a worthwhile goal of rehabilitation.

Leisure has been shown to be associated closely with life satisfaction and is a worthwhile goal of rehabilitation.

Elderly persons show a decline in leisure activity, which has been well-studied. This information may provide a useful model for the more rapid decline seen in stroke patients.

Elderly persons show a decline in leisure activity, which has been well-studied. This information may provide a useful model for the more rapid decline seen in stroke patients.

Further research is needed to confirm the finding that specialized occupational therapy can be effective in raising leisure activity and to show whether this translates into improved psychological well-being.

Further research is needed to confirm the finding that specialized occupational therapy can be effective in raising leisure activity and to show whether this translates into improved psychological well-being.

Widen-Holmqvist and colleagues42 studied a community-based sample of 20 patients living at home one to three years after hospitalization for stroke and who perceived that they were in need of rehabilitation services. Their results included the following:

Most of the subjects reported a change in activity and interest patterns after stroke.

Most of the subjects reported a change in activity and interest patterns after stroke.

Subjects had high motivation for current activities.

Subjects had high motivation for current activities.

Cognitive functions were within normal limits for all tested subjects.

Cognitive functions were within normal limits for all tested subjects.

Motor abilities and verbal performances frequently were affected and varied considerably.

Motor abilities and verbal performances frequently were affected and varied considerably.

Social and leisure activities outside the home were identified as the most promising goals for community-based rehabilitation programs and that by focusing on such activities, improvement in quality of life for this population could possibly be achieved by individually planned rehabilitation programs.

Social and leisure activities outside the home were identified as the most promising goals for community-based rehabilitation programs and that by focusing on such activities, improvement in quality of life for this population could possibly be achieved by individually planned rehabilitation programs.

Amarshi, Artero, and Reid2 published a qualitative study of 12 stroke survivors and aimed to investigate the types of social/leisure activities engaged in pre/poststroke, the meaning attributed to leisure pursuits, and the process involved in social/leisure participation following stroke. The authors identified four themes from their data:

Life has changed when characterized by reduced social/leisure activity, giving up favored leisure occupations, and having to rely on others.

Life has changed when characterized by reduced social/leisure activity, giving up favored leisure occupations, and having to rely on others.

Limitations to participation include physical impairments, cognitive impairments, transportation issues, and cost.

Limitations to participation include physical impairments, cognitive impairments, transportation issues, and cost.

Requirements for participation include social supports and interactions with others, fitting in with others, accommodations related to transportation, and organization support such as structured groups and programs.

Requirements for participation include social supports and interactions with others, fitting in with others, accommodations related to transportation, and organization support such as structured groups and programs.

Moving on with life and reengaging in leisure and social participation including initiate new activities, adapting activities, and maintaining a meaning life.

Moving on with life and reengaging in leisure and social participation including initiate new activities, adapting activities, and maintaining a meaning life.

Factors affecting leisure performance

Many factors affect leisure participation, including the following:

Patterns of underlying impairments (i.e, cognitive, motor, psychological, or combinations)

Patterns of underlying impairments (i.e, cognitive, motor, psychological, or combinations)

Types of leisure tasks available

Types of leisure tasks available

Social and cultural environments

Social and cultural environments

Leisure attitudes, roles, and satisfaction

Leisure attitudes, roles, and satisfaction

A strong, well-coordinated person may prefer physical leisure activities such as baseball, soccer, and basketball. Persons with less developed physical skills may be interested in more intellectual leisure tasks such as reading, playing chess, and working puzzles. They also may be interested in creative leisure pursuits such as painting, photography, and quilting.

Geographic location also may affect participation in leisure activities. If a person lives in a rural environment, leisure activities may include hiking, horseback riding, swimming, and fishing. Someone in an urban environment may go shopping or to theaters, lectures, and museums.

Leisure assumes various forms throughout life. The amount and type of leisure activities depend on the person’s developmental stage.18 During adulthood, leisure pursuits are important for establishing and maintaining social networks. A balance between work and play is important. Factors that influence participation in active leisure activities include financial constraints, decreases in functional skills, and decreases in social supports. Many older individuals replace active leisure tasks with more passive ones after experiencing decreases in physical and cognitive abilities.

Leisure activities during occupational therapy

Occupational therapists working with patients who have had a stroke are concerned with the way these individuals spend their time. Often leisure and play interventions are considered secondary during the rehabilitation process as therapists focus on self-care and instrumental activities of daily living (ADL). However, leisure activities can be equally meaningful to patients as they redefine their life roles.2,39 Occupational therapists can integrate leisure activities into the rehabilitation process in two ways: occupation-as-end and occupation-as-means.40

Occupation-as-end40 refers to activities and/or tasks that comprise a role. The patient chooses the occupation as a meaningful activity he or she wants to perform, needs to perform, or has to perform. Therapists may become aware of these activities (e.g., bowling, crossword puzzles, and making jewelry) via an interview process or a semistructured interview such as the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM).25 When a (leisure) activity is defined by the patient, the therapist collaborates with the patient to accomplish the goal through a variety of interventions including adaptation (e.g., enlarged print on books), education (e.g., providing information regarding transportation methods to and from a local pool), using remaining abilities, and/or remediation. Trombly40 pointed out that when a therapist uses occupation-as-ends, the therapist is not focused on using leisure activities to make a change at the impairment level (e.g., improve scanning ability), although this may occur as a secondary gain. Trombly suggested that the therapist use the following principles to implement occupation-as-end:

Organize the subtasks to be learned so the patient will succeed.

Organize the subtasks to be learned so the patient will succeed.

Use feedback to promote success (see Chapter 5).

Use feedback to promote success (see Chapter 5).

Structure the practice to ensure learning (see Chapter 5).

Structure the practice to ensure learning (see Chapter 5).

Make adaptations when needed (see Chapter 28).

Make adaptations when needed (see Chapter 28).

Occupation-as-means40 may be described as using (leisure) occupations as a treatment to improve body system and body structure impairments. The (leisure) activity is the change agent. The therapist may use leisure activities like the Nintendo Wii to remediate impairments such as weakness, postural dyscontrol, and neglect. Valued leisure activities may be incorporated into the treatment plan to improve other functional areas. For example, the patient may achieve postural and motor goals in a standing position while engaging in a game of air hockey. See Chapter 10 for examples of using occupation-as-means to remediate upper extremity motor control dysfunction and Chapter 19 for examples to improve cognitive-perceptual dysfunction (Box 29-1). Therapists should be cautious about relying too much on using occupation-as-means during treatment sessions; patients should be given a clear explanation related to why the activity was chosen. For example, when a patient has mild neglect, the therapist might say, “As we’ve both discovered, you are forgetting to look for items on your left, such as not finding your tooth brush on the left side of the sink or the juice in the left side of the refrigerator. We are going to try to get you to look left more often. We are going to play dominoes, and I will put all of your dominoes on the left side. Try to look left as often as possible, and I will remind you as needed.” After the activity, processing should occur related to whether the patient met the goals of the session (see Chapter 19). If patients are not given this information, they will not be able to make the connection between the therapeutic activity and their functional goals.

Box 29-1 Role of the Occupational Therapist

Evaluate patient’s physical, cognitive, and perceptual skills and environmental factors (social and cultural) that affect leisure participation.

Evaluate patient’s physical, cognitive, and perceptual skills and environmental factors (social and cultural) that affect leisure participation.

Provide treatment to improve patient’s limitations.

Provide treatment to improve patient’s limitations.

Provide adaptive equipment and adapt techniques to improve leisure participation.

Provide adaptive equipment and adapt techniques to improve leisure participation.

Provide education about various community resources and alternative transportation methods to increase participation.

Provide education about various community resources and alternative transportation methods to increase participation.

Evaluation of leisure skills

When evaluating the leisure roles of patients, therapists must consider seven factors that can affect leisure performance:

1. Evaluation findings related to impairments and performance in areas of occupation

2. Types of leisure activities that interest the patient

3. Patient’s stage in the life cycle

4. Physical, social, and cultural environments

5. Patient’s previous leisure attitudes, roles, and satisfaction

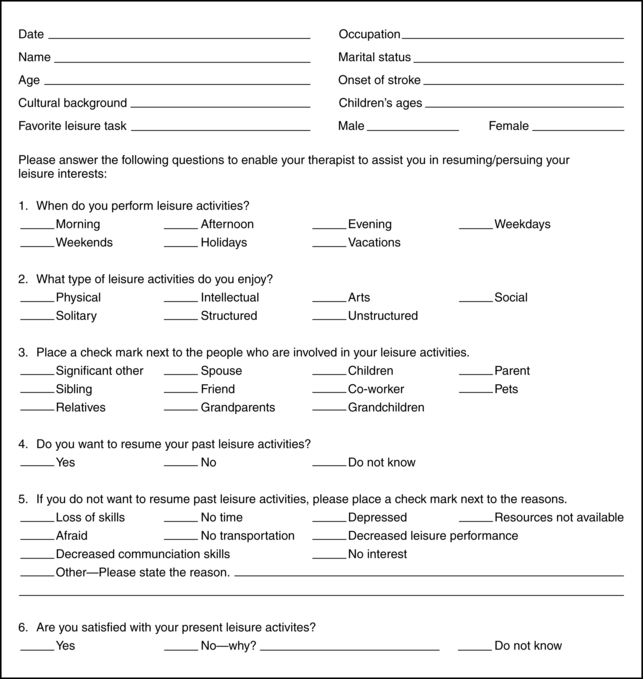

These factors can guide therapists in identifying leisure activities that must be modified and in assisting patients with leisure exploration. A checklist (Fig. 29-1) can assist therapists in determining the type of leisure tasks patients enjoyed before their stroke.17,28

Other usual and customary assessments can assist therapists in making decisions regarding leisure interventions. For example, information regarding range of motion, skeletal muscle activity, strength, endurance, postural control and alignment, motor control, praxis, fine motor coordination, and visual-motor integration is critical. The complete cognitive and perceptual assessment provides necessary information regarding the level of arousal, orientation, recognition, attention span, initiation and termination of activities, memory, sequencing, categorization, concept formation, spatial operations, problem-solving, learning, and generalization.

Therapists should review the type of leisure activities the patient performed before the stroke. For instance, someone who mostly participated in individual leisure tasks may have been content with little social contact. If the person enjoyed relational leisure tasks, social interactions may be important.

The therapist must consider the patient’s stage in the life cycle because participation in leisure changes during the aging process. During adulthood, an individual’s participation in leisure activities decreases because of demands such as work, household maintenance, and childcare. The importance and meaning of leisure also change as a person matures.

The physical, social, and cultural environments are critical in the development of leisure practices and the pursuit of leisure activities during adulthood. Information on the patient’s social and cultural networks helps the therapist focus the treatment plan.

The patient’s leisure attitudes, roles, and satisfaction before the stroke are important factors to consider after the stroke. The therapist should identify the importance of the selected leisure tasks and the patient’s level of satisfaction with them. Identifying the specific aspects of the activity the patient finds enjoyable is helpful. The therapist also should document the patient’s leisure roles by discussing topics such as family expectations.

The therapist can address past and present use of time by asking patients to describe the way they spent their time before the stroke, whether they achieved a balance between work and play, and whether they now require additional time for nonleisure activities.

The therapist must address premorbid barriers to leisure participation, which are obstacles that kept patients from participating in the full scope of leisure activities before their stroke and include intrinsic, environmental, and communication barriers (Box 29-2).

Box 29-2 Factors Affecting Leisure Performance after Stroke

| Type of leisure tasks | Unconditional Compensatory or recuperative Relational Role-determined |

| Stage in the life cycle | Childhood Young adult Middle age Later life |

| Social and cultural environments | Support system (i.e, family and friends) Nationality Religion |

| Leisure attitudes, roles, and satisfaction | Attitudes Roles Satisfaction |

| Use of time | Present Past |

| Barriers to leisure participation | Internal barriers Lack of knowledge Decreased skills Decreased opportunities Environmental barriers Attitudes Architectural Transportation Rules and regulations Barriers of omission Economic Communication barriers Social skills Ability to speak Ability to listen |

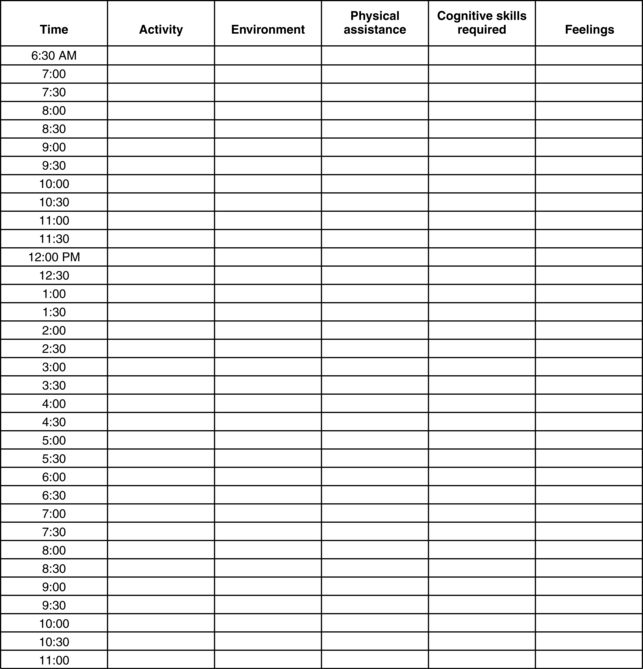

Many ways are available to assess an individual’s leisure interests, such as a leisure interest checklist (see Fig. 29-1), a structured interview form, and a time log (Fig. 29-2) that requires the patient to record previous and current use of time. Therapists should strive to use standardized assessments.

Examples of assessments the therapist can use to assess leisure skills and participation in stroke survivors include the following:

Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire:11,12,35 This assessment was developed to measure the leisure activity of stroke patients. The results of the interrater reliability study were “excellent,” and the results for the test-retest reliability study were “excellent” or “good.” Recently, the Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire has been shortened (from 37 to 30 items) and the response categories have been collapsed (from five to three categories) to make it suitable for mail use.11 Higher Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire scores were associated with higher subscores on the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Scale, and lower Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire scores were associated with living alone and worse emotional health.

Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire:11,12,35 This assessment was developed to measure the leisure activity of stroke patients. The results of the interrater reliability study were “excellent,” and the results for the test-retest reliability study were “excellent” or “good.” Recently, the Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire has been shortened (from 37 to 30 items) and the response categories have been collapsed (from five to three categories) to make it suitable for mail use.11 Higher Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire scores were associated with higher subscores on the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Scale, and lower Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire scores were associated with living alone and worse emotional health.

Activity Card Sort:4 The card sort is used to measure an individual’s participation or lack of participation in instrumental, leisure, and social activities. See Chapter 3 for a full description.

Activity Card Sort:4 The card sort is used to measure an individual’s participation or lack of participation in instrumental, leisure, and social activities. See Chapter 3 for a full description.

Canadian Occupational Performance Measure:25 This semistructured interview covers three areas: leisure, self-care, and productivity. The patient identifies and ranks areas of meaningful occupational performance and rates the level of performance and satisfaction.

Canadian Occupational Performance Measure:25 This semistructured interview covers three areas: leisure, self-care, and productivity. The patient identifies and ranks areas of meaningful occupational performance and rates the level of performance and satisfaction.

Leisure Competence Measure:22,23 This measure provides information about leisure functioning and measures change in leisure function over time. The tool includes nine areas: social contact, community participation, leisure awareness, leisure attitude, social behaviors, cultural behaviors, leisure skills, interpersonal skills, and community integration skills. Items are rated on the 7-point Likert scale.

Leisure Competence Measure:22,23 This measure provides information about leisure functioning and measures change in leisure function over time. The tool includes nine areas: social contact, community participation, leisure awareness, leisure attitude, social behaviors, cultural behaviors, leisure skills, interpersonal skills, and community integration skills. Items are rated on the 7-point Likert scale.

Leisure Satisfaction Scale:5,36 This scale measures the degree to which people’s personal needs are met through their leisure activities (24 items scored from 1 to 5; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction).

Leisure Satisfaction Scale:5,36 This scale measures the degree to which people’s personal needs are met through their leisure activities (24 items scored from 1 to 5; higher scores indicate greater satisfaction).

Leisure Diagnostic Battery:7 The original version includes 95 items, whereas the newer, shorter version includes 25 items. Items are rated on 3-point scale. Assessment areas include playfulness, competence, barriers, and knowledge.

Leisure Diagnostic Battery:7 The original version includes 95 items, whereas the newer, shorter version includes 25 items. Items are rated on 3-point scale. Assessment areas include playfulness, competence, barriers, and knowledge.

Frenchay Activities Index:41 This tool is used for assessing general (i.e, other than personal care) activities of stroke survivors. The tool comprises 15 individual activities summed to give an overall score from 0 (low) to 45 (high).

Frenchay Activities Index:41 This tool is used for assessing general (i.e, other than personal care) activities of stroke survivors. The tool comprises 15 individual activities summed to give an overall score from 0 (low) to 45 (high).

Interventions to improve leisure skills

The intervention process begins with obtaining the patient’s leisure history. The therapist then reviews the results of the evaluation and determines the patient’s strengths and limitations in relation to the performance components. Leisure tasks may be used to achieve the goals of occupational therapy treatment. Leisure activities may be used during treatment sessions to remediate impairments, enhance the skill itself, or adapt the leisure activity itself. Therapists must identify the skills necessary to perform the tasks and modify them according to each patient’s ability. The occupational therapist may provide treatment for neuromuscular, psychological, and cognitive deficits that will enable the patient to engage in the leisure activity.

The National Therapeutic Recreation Society proposes a continuum model of leisure service delivery. According to one description, “the ‘Leisure Ability Model’ serves as a guide for community recreation professionals to facilitate the movement of individuals with disabilities from more intrusive, specialized recreation services into integrated leisure environments.”38 This model consists of a continuum with four levels:

At the first level noninvolvement, the person who has the disability does not participate in any leisure tasks. At the second level segregated, the patient participates in structured activities developed for group members with the same disability group. Examples include community activities through local stroke organizations, stroke support groups, and specialized sports programs (aquatics).

The third level integrated “provides persons with disabilities the opportunity to be mainstreamed into regular community recreation programs and to participate alongside nondisabled participants. This approach appears to go a long way toward helping to change the negative attitudes, stereotypes, stigmas, and myths associated with persons with disabilities and the systems that serve them.”38 The occupational therapist can instruct patients in the use of adaptive equipment and methods to pursue leisure activities successfully in the community.

The fourth level accessible occurs when the individual with a disability “is able to select and access preferred recreation programs with no more effort than his or her counterpart who is not disabled. . . . The participant is able to realize his or her ultimate goal of achieving a satisfying leisure lifestyle, free of any significant individual and external constraints.”38

The therapist can use these levels to improve an individual’s involvement gradually. For instance, if a patient enjoys bowling and wants to return to this activity, the therapist may locate or form a specialized bowling program. When the patient develops skills, he or she may join an integrated bowling program and eventually an accessible bowling program. This model can serve as a guide for occupational therapists when introducing resources for leisure services. Occupational therapists can assist patients in exploring alternative types of leisure tasks that fulfill their needs. This may include expanding their leisure activity repertoires to improve the quality of their lives. Occupational therapists educate patients on available services.

Treatment also can focus on helping patients and family members overcome barriers to leisure participation. Common barriers are intrinsic, environmental, and communication-related.

Intrinsic barriers are the results of the disability. These barriers may include lack of knowledge about leisure activities and programs, decreased educational activities, health problems related to the disability, psychological and physical dependence, and decreased skills.21

Occupational therapists can address intrinsic barriers in a variety of ways. Remaining informed about current community resources, support groups in the area, and professional leisure organizations designed to serve individuals who have a physical disability is essential.8 These organizations include stroke support groups, wheelchair sport leagues, and the American Heart Association.

Environmental barriers include attitudes, architectural and ecological obstacles, transportation, rules and regulations, and barriers of omission.21 The attitudes of others are a serious problem for persons who have disabilities. Attitudinal barriers result in negative behaviors, stigmas, and decreased acceptance and participation in leisure tasks. Occupational therapists can suggest strategies that patients can use to address social prejudices.

Architectural barriers prevent individuals who have physical disabilities from participating in leisure activities. The main problem is accessibility as many buildings and sport facilities are not wheelchair accessible. Occupational therapists can consult with architects, builders, and contractors to determine necessary modifications, such as installing a lift for a swimming pool. See Chapter 27.

Transportation barriers are another issue. Many persons with disabilities cannot drive or take public transportation independently. Public transportation is not always wheelchair-accessible and when it is accessible, it does not always foster independence because a driver may be required to operate the lift for the person to enter. The Americans with Disabilities Act is correcting this problem gradually by requiring wheelchair-accessible transportation. Occupational therapists can educate patients about the Americans with Disabilities Act and alternate methods of transportation. See Chapter 23.

Economic barriers also play a role in preventing individuals with disabilities from performing leisure activities. For example, gym memberships are too costly even for many able-bodied persons. Disabled individuals often live on a fixed income and have many medical and living expenses. Occupational therapists can educate their patients about available resources and community groups and encourage participation.

The final barrier involves communication. Disabilities that affect the ability to speak, listen, or respond lead to poor social interaction during the leisure task. By training patients in the use of assistive technology to improve communication skills, occupational therapists can play an active role in correcting this environmental barrier (see Chapter 20).

Leisure interventions for stroke survivors: evidence-based practice

A number of research studies address the issue of leisure activities after stroke. This literature can provide occupational therapists with valuable information about assessment and adaptation of leisure skills for stroke patients.10,24,26,31 Research has demonstrated that many individuals who sustained a stroke do not resume many of their favorite social and leisure activities.19,29 Factors that affect leisure participation after stroke include the following:

Other studies have found the following:

Individuals who sustained strokes do not resume leisure tasks because they do not have time. Their days usually are filled with exercises and self-care tasks. In addition, subjects reported that time passed slowly and they were bored.19,29

Individuals who sustained strokes do not resume leisure tasks because they do not have time. Their days usually are filled with exercises and self-care tasks. In addition, subjects reported that time passed slowly and they were bored.19,29

Disabilities resulting from stroke can lead to changes in family roles and social relationships, which may result in role strain or role conflict.20

Disabilities resulting from stroke can lead to changes in family roles and social relationships, which may result in role strain or role conflict.20

Depression after stroke is related strongly to a decrease in social activities.14

Depression after stroke is related strongly to a decrease in social activities.14

Stroke survivors do not resume normal social activities after stroke. Factors include social and environmental issues, emotional difficulties, and organic brain dysfunction. Activities outside the home appear more difficult to resume than activities in the home.

Stroke survivors do not resume normal social activities after stroke. Factors include social and environmental issues, emotional difficulties, and organic brain dysfunction. Activities outside the home appear more difficult to resume than activities in the home.

Factors that affect life satisfaction after stroke include depression, poor ADL performance, and decreased social activity outside the home.3

Factors that affect life satisfaction after stroke include depression, poor ADL performance, and decreased social activity outside the home.3

Occupational therapists need to document what types of intervention are most successful in improving engagement in leisure activities after a stroke. At this point, clinical trials focused on this issue had conflicting results.

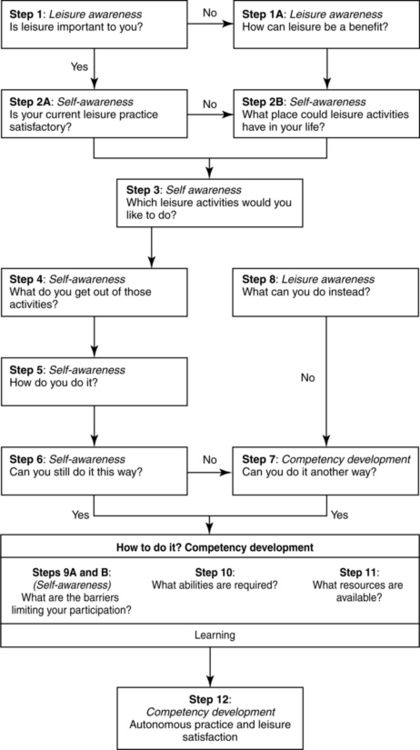

Desrosiers and colleagues9 evaluated the effect of a leisure education program on participation in and satisfaction with leisure activities (leisure-related outcomes), and well-being, depressive symptoms, and quality of life (primary outcomes) after stroke via a randomized controlled trial. Experimental participants received the leisure education program at home once a week for eight to 12 weeks. Control participants were visited at home at a similar frequency. Participants were evaluated before and after the program by a blinded assessor. The leisure education program was carried out by an occupational and recreational therapist for a maximum of 12 sessions. The program was divided into three components, as defined by Desrosiers and colleagues:

Leisure awareness (i.e, the perception and knowledge people have of their leisure activities and how important they consider them)

Leisure awareness (i.e, the perception and knowledge people have of their leisure activities and how important they consider them)

Self-awareness (i.e, people’s perception of themselves, and their values, attitudes, and capacities in regard to leisure activities)

Self-awareness (i.e, people’s perception of themselves, and their values, attitudes, and capacities in regard to leisure activities)

Competency development that encompassed the perceived and real constraints identified by the person and knowledge of alternatives to achieve autonomy in leisure activities (Fig. 29-3)

Competency development that encompassed the perceived and real constraints identified by the person and knowledge of alternatives to achieve autonomy in leisure activities (Fig. 29-3)

Figure 29-3 Summary of the leisure education program. (From Desrosiers J, Noreau L, Rochette A, et al: Effect of a home leisure education program after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 88(9):1095–1100, 2007.)

The authors found that the leisure education program was effective for improving participation in leisure activities, improving satisfaction with leisure, and reducing depression in people with stroke. There were no differences between the groups on the General Well-Being Schedule or the Stroke-Adapted Sickness Impact Profile.

Drummond and Walker13 carried out a randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness of a leisure rehabilitation program on functional performance and mood. Subjects were allocated randomly to three groups: a leisure rehabilitation group, a conventional occupational therapy group, and a control group. The subjects assigned to the leisure and conventional occupational therapy group received individual treatment at home after discharge from hospital. Baseline assessments were carried out on admission to the study and at three and six months after discharge from hospital by an evaluator blind to the trial. The results showed an increase only in the leisure scores for the leisure rehabilitation group, despite an age imbalance in the study. The authors also concluded that subjects receiving leisure rehabilitation performed significantly better in mobility and psychological well-being than the subjects in the other two groups.

Parker and colleagues34 evaluated the effects of leisure therapy and conventional occupational therapy via a randomized controlled trial (multicenter) using the outcomes of mood, leisure participation, and independence in ADL. Subjects included stroke survivors six and 12 months after hospital discharge. In total, the study included 466 patients from five centers in the United Kingdom. The standardized assessments used in the trial included the General Health Questionnaire (12 items), the Nottingham Extended ADL Scale, and the Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire, assessed by mail and with telephone follow-up for clarification. Eighty-five percent of survivors and 78% of survivors responded at six- and 12-month follow-up, respectively. At six months and compared with the control group, those allocated to leisure therapy did not have significantly better General Health Questionnaire scores, leisure scores, and extended ADL scores. The group assigned to ADL did not have significantly better General Health Questionnaire scores and extended ADL scores and did not have significantly worse leisure scores. The results at 12 months were similar. The authors concluded that in contrast to the findings of previous smaller trials, neither of the additional occupational therapy treatments showed a clear beneficial effect on mood, leisure activity, or independence in ADL measured at six or 12 months.

A post hoc analysis by Logan and colleagues27 of the previously mentioned study by Parker and colleagues34 further examined the ADL and leisure groups. The ADL group received significantly more mobility training, transfer training, cleaning, dressing, cooking, and bathing training, while sport, creative activities, games, hobbies, gardening, entertainment, and shopping were used significantly more in the leisure group. Fifteen items from the outcome measures were identified as specific to these interventions. The authors found no evidence that specific ADL or leisure interventions led to improvements in specific relevant outcomes.

Gilbertson and Langhorne15 evaluated a short postdischarge home-based occupational therapy service for stroke patients, including an assessment of the patients’ satisfaction with occupational performance and service provision using a single-site, blind, randomized, controlled trial. One hundred thirty-eight patients were assigned randomly to a conventional outpatient follow-up or conventional services plus six weeks of home-based occupational therapy. The data were collected before discharge and at seven weeks and six months after discharge using the COPM, the Dartmouth Cooperative (COOP) Charts, the London Handicap Scale, and a patient satisfaction questionnaire. At seven weeks, the intervention group reported significantly greater changes in performance and satisfaction (COPM), better emotional scores (Dartmouth COOP Charts), and improved work and leisure activity scores (London Handicap Scale). The authors concluded that a six-week postdischarge home-based occupational therapy service could improve patients’ perceptions of their occupational performance and satisfaction with services but may not have a long-term effect on subjective health outcomes.

Gladman and Lincoln16 reported findings of the Domiciliary Stroke Rehabilitation (DOMINO) study that compared home-based and hospital-based rehabilitation services for stroke patients via a randomized, controlled trial, with 327 subjects enrolled after discharge from the hospital. No difference between the services had been found at six months, but home therapy was better than outpatient therapy related to improving household ability and leisure activity in the subjects who originally were discharged from a stroke unit.

Jongbloed and Morgan19 designed a study to determine the efficacy of occupational therapy intervention related to the leisure activities of stroke survivors. The study included 40 discharged stroke patients who were assigned randomly to an experimental group, which received occupational therapy intervention related to leisure activities, or to a control group. An independent evaluator assessed the patients’ involvement in activities and satisfaction with that involvement on three separate occasions. The authors found no statistically significant differences between the experimental and control groups in activity involvement or satisfaction with that involvement. The authors point out that the lack of significant differences may be due to the intervention being limited in scope (five therapist visits) and the observation that many environmental factors strongly influence activity participation and satisfaction.

Adapting the leisure task

Reintroducing leisure activities to patients who have sustained a stroke is important. If the patient does not regain the skills needed to perform these leisure tasks, many adaptive devices are on the market to enable full participation in these tasks. To select the most effective adaptive aid, the occupational therapist analyzes the skill components necessary to perform the chosen activity. After identifying the components that limit performance, the therapist selects and introduces an appropriate adaptive device. Occupational therapists provide patients with information about various organizations, adaptive methods, and adaptive equipment that enhance and promote participation in leisure activities. Use of these resources enables patients to lead meaningful and productive lives.

Many types of adaptive equipment enable patients who have use of one hand to participate in leisure tasks (e.g, card holders, knitting-needle holders, fishing-pole holders, and needlepoint holders). These products are available from the Internet, catalogs, occupational therapists, and specialized organizations and stores.

Summary

Leisure is a complex phenomenon. A review of the literature reveals that leisure may be defined in various ways. Many factors influence an individual’s participation in leisure activities, such as roles, attitudes, satisfaction, stage in the life cycle, and intrinsic and extrinsic barriers. The role of the occupational therapist is multifaceted, including assessment, intervention through techniques and adaptive equipment, and patient and family education, with an emphasis on community resources. Leisure activities may be used to improve a patient’s motivation, quality of life, and self-esteem.

CASE STUDY Leisure Skills after Stroke

R.S. is a 74-year-old woman who sustained a right-sided stroke four months ago. After completion of the central nervous system assessment, interest checklist, time log, and activity analysis form, the occupational therapist established goals with R.S.

Briefly, the results of the central nervous system assessment were as follows. Right upper extremity function was within normal limits. Left upper extremity function revealed poor motor control with stereotypical patterns present and impaired sensation throughout. Ability to shift weight anteriorly and laterally while in a seated position was fair. Sustained attention skills were limited. She had a minimal left-sided inattention to self and environment and minimal impairments with spatial relations.

R.S. has been widowed for five years and reported feeling lonely, depressed, and fearful of falling. Her three adult children live out of state, and her social network consists of supportive neighbors, church members, and her dog.

Currently a home health aide assists R.S. with self-care and home management tasks. R.S. requires activity set-up for grooming and upper body hygiene, minimal assistance with upper body dressing and bathing, moderate assistance with lower body dressing and bathing, moderate assistance for stand-pivot transfers, minimal assistance for bed mobility, and moderate assistance with meal preparation from a seated level. She is not performing her favorite leisure task of knitting. How can an occupational therapist assist R.S.?

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank early contributors Denise A. Supon and Nancy C. Whyte.

Review questions

1. List and define the types and purposes of leisure tasks.

2. What are the factors the therapist must address when evaluating an individual’s leisure participation and performance after sustaining a stroke? Describe how these factors affect leisure participation and performance.

3. What are leisure attitudes, roles, and satisfaction?

4. List and describe the environmental barriers that affect leisure participation.

5. What is the role of the occupational therapist in assessing and improving a patient’s leisure participation after a stroke?

6. How would the occupational therapist assist a patient and family members in resuming leisure activities in their community?

1. Amarshi F, Artero L, Reid D. Exploring social and leisure participation among stroke survivors. Part two. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2006:13;5:199-208.

2. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy practice framework. Domain and process, 2nd ed. Am J Occup Ther. 2008:62;6:625-683.

3. Astrom M, Asplund K, Astrom T. Psychosocial function and life satisfaction after stroke. Stroke. 1992;23(4):527-531.

4. Baum CM, Edwards DF. Activity Card Sort, 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press; 2008.

5. Beard JG, Ragheb MG. The leisure satisfaction measure. J Leis Res. 1980;12(1):20-33.

6. Bear-Lehman J, Bassile CC, Gillen G. A comparison of time use on an acute rehabilitation unit. Subjects with and without a stroke. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2001:20;1:17-27.

7. Chang Y, Card JA. The reliability of the leisure diagnostic battery short form version B in assessing healthy, older individuals. a preliminary study. Ther Recreation J. 1994:28;3:163.

8. Dattilo J. Inclusive leisure services. responding to the rights of people with disabilities. State College, PA: Venture Publishing. 1994.

9. Desrosiers J, Noreau L, Rochette A, et al. Effect of a home leisure education program after stroke. a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007:88;9:1095-1100.

10. Drummond AE. Leisure activity after stroke. Int Disabil Stud. 1990;12(4):157-160.

11. Drummond AE, Parker CJ, Gladman JR, et al. Development and validation of the Nottingham leisure questionnaire (NLQ). Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(6):647-656.

12. Drummond AE, Walker M. The Nottingham leisure questionnaire for stroke patients. Br J Occup Ther. 1994;57:414-418.

13. Drummond AE, Walker MF. A randomized controlled trial of leisure rehabilitation after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 1995;9(4):283.

14. Feibel JH, Springer CJ. Depression and failure to resume social activities after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63(6):276-277.

15. Gilbertson L, Langhorne P. Home-based occupational therapy. stroke patients’ satisfaction with occupational performance and service provision. Br J Occup Ther. 2000:63;10:464.

16. Gladman JR, Lincoln NB. Follow-up of a controlled trial of domiciliary stroke rehabilitation (DOMINO Study). Age Ageing. 1994;23(1):9-13.

17. Holbrook M, Skilbeck CE. An activities index for use with stroke patients. Age Ageing. 1983;12(2):166-170.

18. Iso-Ahola S, Jackson E, Dunn E. Starting, ceasing and replacing leisure activities over the life span. J Leisure Res. 1994;26(3):227-249.

19. Jongbloed L, Morgan D. An investigation of involvement in leisure activities after a stroke. Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45(5):420-427.

20. Jongbloed L, Stanton S, Fousek B. Family adaptation to altered roles following a stroke. Can J Occup Ther. 1993;60(2):70.

21. Kennedy D, Austin D, Smith R. Special recreation opportunities for persons with disabilities. Dubuque, IA: WC Brown; 1987.

22. Kloseck M, Crilly RG. Leisure competence measure. adult version I. London, Ontario: Data System. 1997.

23. Kloseck M, Crilly RG, Hutchinson-Troyer L. Measuring therapeutic recreation outcomes in rehabilitation. Further testing of the Leisure Competence Measure. Ther Recreation J. 2001:35;1:31-42.

24. Krefting L, Krefting D. Leisure activities after a stroke. an ethnographic approach. Am J Occup Ther. 1991:45;5:429-436.

25. Law M, Baptiste S, Carswell A, et al. Canadian occupational performance measure manual, ed 3. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 1998.

26. Lawrence L, Christie D. Quality of life after stroke. a three year follow-up. Age Ageing. 1979:8;3:167-172.

27. Logan PA, Gladman JR, Drummond AE, Radford KA. A study of interventions and related outcomes in a randomized controlled trial of occupational therapy and leisure therapy for community stroke patients. The interest checklist. 2003;17(3):249-255.

28. Matsutsuyu J. Clin Rehabil. Am J Occup Ther. 1969;23(4):323-328.

29. Morgan D, Jongbloed L. Factors influencing leisure activities following a stroke. an exploratory study. Can J Occup Ther. 1990:57;4:223.

30. Mosey AC. Applied scientific inquiry in the health professions. An epistemological orientation, 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association. 1996.

31. Niemi M, Laaksonen R, Kotila M, et al. Quality of life 4 years after stroke. Stroke. 1988;19(9):1101-1107.

32. Parham D, Fazio L, editors. Play in occupational therapy for children. St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1997.

33. Parker CJ, Gladman JR, Drummond AE. The role of leisure in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 1997;19(1):1-5.

34. Parker CJ, Gladman JR, Drummond AE, et al. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of leisure therapy and conventional occupational therapy after stroke, TOTAL Study Group, trial of occupational therapy and leisure. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15(1):42-52.

35. Parker CJ, Logan PA, Gladman JRF, Drummond AER. A shortened version of the Nottingham Leisure Questionnaire. Clin Rehab. 1997;11(3):68-267.

36. Raghed M, Griffith C. The contribution of leisure participation and leisure satisfaction to life satisfaction of older persons. J Leis Res. 1982;14(4):295-306.

37. Rittman M, Faircloth C, Boylstein C, et al. The experience of time in the transition from hospital to home following stroke. J Rehabil Res Devel. 2004;41(3A):68-259.

38. Schlelen S, Ray M. Community recreation and persons with disabilities. strategies for integration. Baltimore: Paul B Brookes. 1988.

39. Soderback I, Ekholm J, Caneman G. Impairment/function and disability/activity 3 years after cerebrovascular incident or brain trauma. a rehabilitation and occupational therapy view. Int Disabil Stud. 1991:13;3:67-73.

40. Trombly CA. Occupation. In Trombly CA, Radomski MV, editors: Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction, ed 5, New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2002.

41. Wade DT, Legh-Smith J, Langton Hewer R. Social activities after stroke. measurement and natural history using Frenchay activities index. Int Rehabil Med. 1985:7;4:176-181.

42. Widen-Holmqvist L, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Holm M, et al. Stroke rehabilitation in Stockholm. basis for late intervention in patients living at home. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1993:25;4:173-181.