chapter 3 Improving participation and quality of life through occupation

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

1. Describe key concepts of participation, occupation, and quality of life in stroke.

2. Understand key measures occupational therapists can use to address participation, occupation, and quality of life in practice.

3. Address participation in the continuum of care from the acute episode to community reintegration.

4. Describe barriers that threaten participation and quality of life.

5. Identify the key role that therapists have in fostering participation through occupation.

Concepts central to enabling participation

In the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, second edition, the definition of “participation” is adopted from the World Health Organization definition in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) and is said to be the “involvement in a life situation.”2,59 The term participation encompasses the concepts of personal independence and social and community integration.59 Participation must be considered across the life span. A child plays with friends, engages in sports, goes to school, and is a member of a family; an adult participates in family, work, leisure, and community activities; an older adult may want to continue to work, to travel, to do volunteer work, and to spend time with family. These activities reflect the individual’s desire to participate fully in society, performing the occupations that are meaningful and important to them

Participation is supported or limited by the physiological, psychological, cognitive, sensory, and motor capacities of the individual. Likewise, participation is supported or limited by environmental factors. Obvious environmental factors include the physical and social factors associated with accessibility and access to social support; others include governmental and organizational policies, especially as they affect employment.

Participation is easily taken for granted. Being able to do what one wants to do, go where one wants to go, and have freedom in the choice of activities at the time at which one wants do them is central to personal independence. Participation can be compromised after a stroke. Others obviously see that an individual’s participation will be difficult if mobility problems impair balance or if the individual uses a wheelchair and faces stairs, narrow doorways, and steep inclines. What may not be so obvious are impairments not so visible, such as spatial neglect, depression, and loss of executive control.

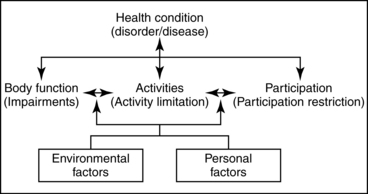

In recent years, the concept of participation has become much more visible, for it is a central concept in the new Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, second edition (Framework-II) and ICF. Within the Framework-II, supporting health and participation through in engagement in occupation is defined as the overarching goal of occupational therapy intervention.2 The ICF defines health as the interaction of body function with engagement in activity and participation as influenced by environmental factors and personal choice (Fig. 3-1).59 The link between health and participation, as defined by these two frameworks, will eventually lead professionals from all of the health fields to eventually organize their services to support participation. One must understand some key concepts to practice with participation as a central concept and outcome. These terms include occupation, client-centered care, and quality of life.

Figure 3-1 Interaction of components of the ICF.

(From International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, 2001: World Health Organization, pg. 18, Figure 1.)

Occupation

To participate fully in a life that has meaning, independence, and choice, the individual engages in “occupations.” Occupation has been defined as the “ordinary and familiar things that persons do every day.”16 Occupations have purpose, and perhaps most importantly, they have meaning for the person engaged in them. When individuals engage in occupations, they are engaged in activities that are directed by goals or are purposeful, are performed in situations or contexts that influence them, can be identified by the doer and others, and are meaningful.15

Occupations usually are classified into general categories; the most common classifications fall into the domains of work (or productivity), play or leisure, and self-maintenance (also referred to as self-care and instrumental tasks). These categories account for the cycle of activities that constitutes the typical day, regardless of the culture being studied.39

Work

Work contributes significantly to life satisfaction, well-being, self-worth, and social identity following stroke.4,30,46,52 Work is difficult to classify, for what is work to one may be play or leisure to another. Primeau points out that some may derive relaxation and enjoyment in performing household chores, whereas others detest the experience.44 She asks readers to consider professional athletes who are paid well to exhibit their skills in tennis, golf, baseball, hockey, and other sports. These same occupations are pursued by amateurs as freely chosen recreational and leisure pastimes. The Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists has used the term productivity as a more useful alternative to work. Productivity is defined as “those activities and tasks which are done to enable the person to provide support to the self, family, and society through the production of goods and services.”12

Play/leisure

Play is a term used interchangeably with leisure to describe the nonwork activities of adults in addition to play as the chosen activities of children. Takata asks one to consider that play is not defined by specific behaviors or activities but rather by attitudes and behavioral styles.47 Because of these characteristics, playfulness (or moments of play) can be experienced during (or enfolded within) work. Play and leisure must be considered central to the activities of individuals following stroke.

Leisure is thought to be a class of activities carried out in discretionary time.22 Freedom of choice in participation without a particular goal other than enjoyment seems to be the defining characteristics of leisure activity.25 No one can imagine lives devoid of play or leisure, and neither should a person who has had a stroke. That person’s engagement in play and leisure should be enabled with tools, skills, and environments (see Chapter 29).

Self-care

Those activities necessary for maintenance of the self within the environment constitute another major classification of occupation. Often included in this category are activities related to personal care (eating, grooming, and hygiene), getting around (mobility), and communicating. For a person to be self-reliant in any community, a level of competence is required that enables the accomplishment of tasks beyond those of basic self-care (which are referred to as physical self-maintenance). For this reason, M. Powell Lawton identified the use of the telephone, food preparation, housekeeping, laundry, shopping, money management, driving or use of transportation, and medication management as important daily activities and proposed the term instrumental activities of daily living (ADL) to describe them35 (see Chapters 14, 21, 22, 23, and 28).

Often when persons are hospitalized, the focus is on achieving independence in self-care. Christiansen suggested that self-care tasks must be viewed as necessary from a societal point of view.14 Although eating and hygiene tasks are essential for survival and health, dressing and grooming are important to social interaction and participation. Some expect persons to care for themselves. Sometimes therapists go too far in expecting an individual to perform self-care; some individuals prefer to spend their time in other occupations and accept the help of others to do basic self-care. Therapists are familiar with the use of personal attendants with persons following spinal cord injuries; persons who have had a stroke benefit from a personal attendant, so that they have choice in how they spend their time in occupations more important and meaningful to them.

A discussion of occupation cannot be complete without a discussion of self-efficacy and self-determination. Bandura used the term self-efficacy to describe the extent to which successes or failures influence expectations of future success or failure.3 The experience of success in doing things (occupations) contributes to a positive sense of oneself as effective or competent. In contrast, a negative view of self and one’s ability to influence events can lead to perceptions of helplessness. Gage and Polatajko observed that perceived self-efficacy has been shown to influence perseverance and well-being and that it can be modified through successful experiences.21

According to self-determination theory, intrinsic sources of motivation lead persons to encounter new challenges.45 An important (and logical) part of this theory is the claim that settings in which persons experience success helps them feel good about themselves. This enables persons to face their daily challenges more readily and in the process to develop an understanding of who they are and their place in the world.

Following stroke, many individuals are not able to engage in their occupations as they have in the past. Therapy must create the environment for learning that fosters a person’s view of self so that successful experiences can be experienced and sustained. Opportunities for success must be fostered as well, so that these persons are motivated to face their daily challenges.

Occupation is a concept that must be understood in terms of planning and describing the activities of an individual; it provides an important process that can and should be used in the rehabilitation program to improve a person’s recovery. Box 3-1 highlights key statements that identify the importance of occupation; these can be translated directly into outcomes that practitioners can address today as they plan client-centered care.

Box 3-1 The Importance of Occupation

Occupation is the vehicle to acquire, maintain, or redevelop skills necessary to fulfill occupational roles and to provide satisfaction.20

Occupation is the vehicle to acquire, maintain, or redevelop skills necessary to fulfill occupational roles and to provide satisfaction.20

The lack of occupation leads to a breakdown in habits and physiological deterioration, which lead to loss of ability and competency to support daily life.28

The lack of occupation leads to a breakdown in habits and physiological deterioration, which lead to loss of ability and competency to support daily life.28

Individuals with cognitive loss who remain engaged in occupations retain higher levels of functional status and demonstrate fewer disturbing behaviors.6

Individuals with cognitive loss who remain engaged in occupations retain higher levels of functional status and demonstrate fewer disturbing behaviors.6

Engagement in individually motivating and ongoing occupations supplies sustenance for survival, safety, and enhanced health.54

Engagement in individually motivating and ongoing occupations supplies sustenance for survival, safety, and enhanced health.54

Meaningful occupations provide individuals with exercise to maintain homeostasis and to keep body parts and neuronal physiology and mental capacities functioning at peak efficiency and enable maintenance and development of satisfying and stimulating social relationships.54

Meaningful occupations provide individuals with exercise to maintain homeostasis and to keep body parts and neuronal physiology and mental capacities functioning at peak efficiency and enable maintenance and development of satisfying and stimulating social relationships.54

Client-centered care

Clients who have had strokes need support to return to their lives as they lived them before the stroke. They require services that help them build endurance, increase movement and strength, increase awareness, obtain assistive devices such as wheelchairs and self-care tools, acquire accessible housing, and gain access to barrier-free workplaces and communities. These needs challenge rehabilitation professionals to extend their interventions beyond the clients’ immediate impairments to focus on their long-term health needs by helping them develop healthy behaviors to improve their health and well-being and to minimize long-term health care costs associated with dysfunction.7

Rehabilitation traditionally has occurred in institutions and is a time-limited process aimed at helping a person with a stroke reach an optimum level of self-care function. This approach labels the recipient of service as a patient, has led the patient to understand that the therapist would fix the problem, and has led the therapist to expect patients and their families to comply with his or her recommendations.38 This approach does not reflect client-centered care. Within the Framework-II, client-centered care must begin with the occupational therapist gathering information to understand what is currently important and meaningful to the client before beginning to address any impairments.2 To move from the traditional approach to a client-centered approach, practitioners must shift from focusing on impairments to understanding why problems occur, what the client views as a problem, and what might be done about them.

A client-centered approach requires a different orientation, one that engages the assistance and support of a therapist to facilitate the client’s problem-solving and goal achievement.38 In a client-centered program, the practitioner and the client bring important information to the partnership. For clients to understand why the practitioner is involved in their care and what they can expect to achieve through therapy is as important as for the therapist to understand the issues and needs of the clients. For clients to understand the scope of the therapist’s knowledge is also important. The client’s knowledge of his or her condition and experience with the problem must become clear for the relationship to progress. If a person has a cognitive limitation, the person selected to be the guardian or caretaker must participate in treatment planning7 to ensure protection of the client’s rights.

Early in the interaction, practitioners should obtain information from clients about their perception of the problem, needs, and goals. The implementation of a client-centered approach requires the use of a top-down approach37,49 in which clients identify what they perceive to be the important issues causing them difficulty in carrying out their daily activities in work, self-maintenance, leisure, and rest.7

A client-centered approach requires practitioners to view clients in the contexts of their lives and help them not only to acquire the skills to handle the immediate issues influencing their health but to also learn strategies and link with community resources that promote, protect, and improve their health over the long term. This approach extends from the agency or institution into the community, requiring the practitioner to take an active role in advocating for healthy communities by removing attitudinal, economical, and physical barriers.7

Quality of life

How do we think about the quality of our lives? In a recent discussion the authors had with students, not one student mentioned quality of life issues related to his or her health. Students’ descriptions included being satisfied with their lives and doing what they want to do when and how they want to do it. In other words, they were expressing terms that relate to life satisfaction, well-being, and participation.

Rehabilitation professionals must think about their clients in terms of what will be the outcome of services as they affect the daily lives of the clients they serve, not merely the outcome achieved in a short-term goal. The client’s perceived quality of life is increasingly being used as a determinant of outcome in health care.2 Quality is not achieved with improved strength, range, coordination, and balance but by having meaningful relationships, having a job, being a good parent, and engaging in leisure interests, all which depend on having cognitive capacity, strength, endurance, and mobility and may require new skills and new ways of doing things.

The concept of life satisfaction is subjective; what is satisfying to one is not necessarily satisfying to another. The concept reminds one of the importance of implementing a client-centered plan to help the person do what he or she wants and needs to do. The concepts central to life satisfaction are happiness, having plans for the future, and engaging in meaningful interests and experiences.42 All of these concepts are threatened when an individual’s life changes abruptly with a stroke.

Well-being is one of the concepts that contributes to the individual’s perception of quality of life. In addition to happiness, well-being includes the person’s perception of confidence and self-esteem. Wilcock encourages practitioners to consider relationships (including social friends, family, partnerships, neighbors, and strangers) and the availability of surroundings (including home, school, place of worship, peace, and weather and terrain) as central to the individual’s perception of well-being.54 The World Health Organization Quality of Life Group defines quality of life as one’s perceptions of one’s position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which one lives and in relation to one’s goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.61

Being able to go where one wants to go and do what one wants to do is central to personal freedom. Participation should be the ultimate goal of medical and rehabilitative care and social services, for it describes the extent to which a person is engaged in life situations in a societal context.59 Interventions must help clients participate in daily life, enabling them to develop the skills or build the adaptive strategies to do what is necessary for them to carry out their occupational roles. Practitioners carrying out their roles and doing what clients want and need them to do makes it possible for them to play a role in the clients’ life satisfaction and sense of well-being. Such an approach contributes to the health and well-being of clients, and collectively to society, for it enables quality in the lives of those served.

With the revisions to the ICF, activity and participation have become issues central to care and must be included in treatment planning.59 Effective rehabilitation treatment begins with a sound assessment. In addition to determining the physical, cognitive, and psychological problems resulting from stroke, one must determine the client’s prior activities to establish the individual’s identity, so the person’s interests are clear to all members of the team, for these interests serve to motivate the person during the rehabilitation.

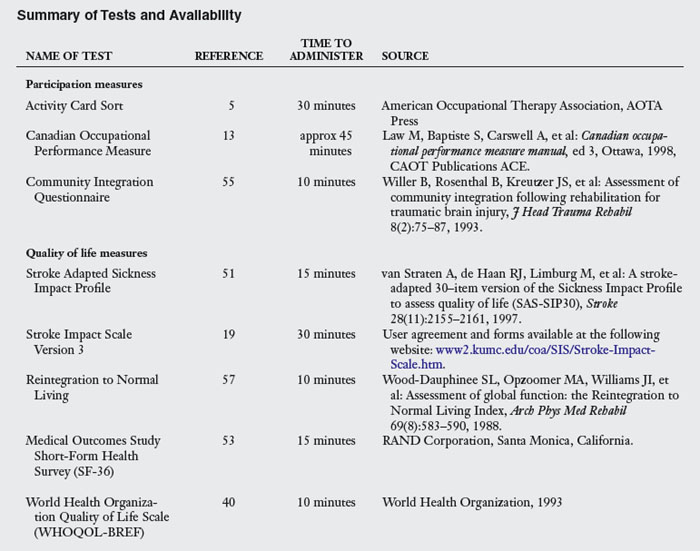

Assessment of participation

A variety of measures are available to determine a client’s prior level of activity.33 Traditionally, therapists have relied on activity checklists and open-ended interviews to obtain information regarding participation before stroke. Unfortunately, these interviews are limited by the client’s memory. Measures have been developed to provide therapists with a systematical and consistent method for evaluating participation. One such measure is the Activity Card Sort, second edition, developed by Baum and Edwards (Fig. 3-2).5 The Activity Card Sort uses a sorting methodology to assess participation in 89 instrumental, social, and high- and low-demand physical leisure activities. Clients sort the cards into different piles to identify activities that were done before stroke, those activities they are doing less often, and those they have given up since their stroke. The Activity Card Sort uses cards with pictures of tasks that people do in their daily lives.

Figure 3-2 Sample cards from the Activity Card Sort. A, Sorting the cards. B, Computer card. C, Cooking card. D, Dishwashing card.

These activities are documented in categories of instrumental, leisure, and social activities. Different versions of the card sort are available for the different contexts in which rehabilitation is occurring. The institutional version (for use in hospitals and nursing homes) sorts 89 cards into categories of activities done before illness and not done afterward. The recovering version identifies activities not done before the illness or injury, those given up because of illness, those one is beginning to do again, and those activities the client is doing now. All versions allow one to determine a current activity level. The card sort takes approximately 30 minutes to administer and results in a score of percent of activities retained. The Activity Card Sort has been found to be a reliable and valid measure and is available in several culture-specific formats.27

The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure, or COPM, is an interview used to assess a client’s perception of recovery and goals.32,34 The COPM is based on a client-centered practice framework. The COPM crosses all diagnoses and is not specific to any age group. The three primary areas identified are self-care, productivity, and leisure. The interview allows identification of problem areas. Satisfaction and importance of the problem areas are rated on a scale from 1 to 10. The COPM takes approximately 45 minutes to administer, but time can vary greatly with the interview. For this reason, the test may be difficult with individuals with cognitive deficits. Despite the length and cognitive difficulty, the assessment validity is good, and the COPM is a client-centered tool that facilitates development of treatment plans and therapeutic goals.13

The Community Integration Questionnaire was originally designed for individuals with traumatic brain injury and is particularly useful with younger stroke clients.55 The Community Integration Questionnaire measures handicap as a function of community integration.36 The questionnaire has 15 items including questions such as “Who does the shopping in your household?” and “How many times a month do you leave the house to go shopping?” Four scores are calculated: home integration, community integration, productivity, and a total score. Each item has a possibility of three responses, with responses weighted numerically. A higher score indicates greater independence.

Assessment of quality of life

The stroke outcome literature historically has reported survival from stroke. Medical advances may prolong life, but knowing how individuals feel regarding their lives after stroke is important.39 A normal neurological examination may not equate to good quality of life for the client. Therefore, well-designed quality of life measures are essential.

The Reintegration to Normal Living57,58 was developed to document reentry into everyday life following a sudden illness or event. The instrument is a functional status measure that quantitatively assesses the degree of reintegration to normal living achieved by clients after illness or trauma and is useful for individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. The Reintegration to Normal Living assesses global function and the individual’s satisfaction with basic self-care, in-home mobility, leisure activities, travel, and productive pursuits. The client is provided with 11 statements. Some examples include “I am able to participate in recreational activities,” “I assume a role in my family that meets my needs and those of the other family members,” and “I am comfortable with how my self-care needs are met.” The test can be completed using a pencil and paper format or an interview format. Reliability and validity have been established for persons with stroke.

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey, or SF-36, is the most commonly used life satisfaction scale.53 The SF-36 has been used extensively with many diagnoses, including stroke, and is quick and easy to administer. The SF-36 is a self-report measure of eight subcategories: physical functioning, physical role limitations, bodily pain, general health perceptions, energy/vitality, social functioning, emotional role limitations, and mental health.

Another quality of life scale is the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS). The SIS is a stroke-specific measure that incorporates function and quality of life into one measure.31 The SIS III is a self-report measure including 59 items that form eight subgroups: strength, hand function, basic and instrumental ADL, mobility, communication, emotion, memory and thinking, and participation. Duncan and colleagues have found the SIS to be valid, reliable, and sensitive to change in stroke populations.19 Furthermore, the SIS is reliable when responses are provided by proxy.18

The Stroke Adapted Sickness Impact Profile (SA-SIP) is a shortened form of the more commonly known Sickness Impact Profile.9,51 The SA-SIP has 30 true/false statements regarding a person’s function and stroke-related symptoms. The statements are separated into seven categories: body care and movement, social interaction, mobility, emotional behavior, household management, alertness behavior, and ambulation. The SA-SIP has good reliability and validity

The World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF)40 was derived from the original WHOQOL-100. It includes 26 items as compared to the original with 100 items. It produces scores for four domains related to quality of life: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. It also includes one facet on overall quality of life and general health. It has been translated into multiple languages (Table 3-1).

Barriers to participation and quality of life

Once the practitioners identify problems with participation and quality of life, they must address barriers to resumption of activities, which can be divided into several subgroups, including disability in basic and complex instrumental ADL, decreased cognition, impaired motor function and balance, limited mobility, urinary incontinence, poor speech and language function, depression, decreased resource use, environmental inaccessibility, and diminishing social and community support. Each is discussed to highlight how rehabilitation can address the issues that may limit an individual’s participation after stroke.

Persons who have had a stroke have impairments that limit their ability to participate in activities outside the home. To go to the grocery store or to church, the individual must be dressed. Dinner with friends requires the motor ability to feed oneself, the cognitive capacity to carry on a conversation, and the judgment to select the appropriate diet. Difficulty with instrumental or more complex ADL affects the person’s ability to return to work, to drive, to manage finances, or to take the bus. See Chapters 21 and 23.

Even in the absence of motor impairment, a cognitive deficit can greatly impair the ability of an individual to return to tasks done before the stroke.23 Cognitive deficits incorporate areas of attention, orientation, perception, praxis, visuomotor organization, memory, executive function, problem solving, planning, reasoning, and judgment.29 Tatemichi and colleagues showed that cognitive dysfunction was a significant predictor for dependent living after discharge and found that quality of life is related to sequential aspects of behavior.48 Reading the newspaper, watching a movie, finding items on a grocery list, or knowing what to do if lost in the mall can be a challenge for some individuals following stroke.26 Clients often report feeling overwhelmed with things that came automatically before the stroke. See Chapters 17, 18, and 19.

Impaired balance is cited in the literature as a key variable to independence in the community because of an increased risk of falls. For someone with impaired balance, a trip to the kitchen for a drink of water is a daunting task. Taking out the trash or resuming bowling may provoke enough fear to stop these activities. Addressing balance impairments in the hospital setting may not transfer to ability in the community, so testing of the individual’s abilities outside of a sheltered rehabilitation clinic is essential. Decreased motor function and coordination contributes to poor participation in prior activities by limiting the ability to write, cut food, or resume playing tennis. See Chapters 8 and 9.

For individuals with limited mobility, home and community access is problematic. Difficulty with stairs or the inability to ambulate long distances limits the scope of activities for survivors of stroke. A home visit before discharge is recommended to resolve any immediate issues with inaccessibility, as individuals commonly receive equipment that does not fit in their homes. Obstacles including stairs, furniture, power cords, lighting, and noise affect the ability to participate in activities inside and outside of the home. For working clients, job site evaluations are necessary for vocational success. For a full-time mother, this may include a comprehensive evaluation of the home and learning what tasks she performs to fulfill her roles. See Chapters 14 and 27.

Speech and language deficits occur in as many as 40% of individuals with strokes.1 Poor speech and language functions deter clients from situations in which conversation is unavoidable. Persisting consequences adversely affect quality of life, ranging from loss of employment to feelings of isolation and depression. Therefore, addressing language barriers and educating clients and families in compensatory strategies alleviates some distress associated with speech and language deficits. Occupational therapists should address participation issues in addition to the interventions provided by speech language pathologists. See Chapter 20.

Depression is another common barrier to participation after stroke. The cause may be directly biological, depending on the location of the lesion in the brain or may be a reaction to a sudden catastrophic event in the client’s life. Depression may affect participation and long-term outcomes adversely,1 and it has been associated with longer hospital length of stay, poor performance in ADL, and decreased socialization. Emotional issues such as fear and depression can lead to decreased reintegration into previous roles and occupations and to decreased quality of life. Following a life-altering event such as a stroke, a person may fear additional illness, injury, or another stroke. For this reason, clients may be hesitant to leave their homes and resume prior roles. In a study by Clarke and colleagues, community-dwelling stroke survivors reported a lower sense of well-being than their healthy community-residing counterparts.17 Clients and their families should be educated regarding risk factors of stroke rehabilitation strategies and medical management following a stroke. Additional education may decrease anxiety regarding a future stroke. Referral to a psychologist may be indicated for some individuals. See Chapter 2.

Urinary incontinence is a barrier to participation frequently overlooked by rehabilitation teams, although it is generally agreed to have a considerable effect on a person’s quality of life and well-being. Between 9% and 40% of the individuals with stroke develop incontinence.10,43 Incontinence has been identified as a predictor for nursing home placement and is associated with poor recovery from stroke.10 Studies in the general population have shown that incontinence is associated with depression50 and higher levels of anxiety.8 Urinary incontinence often leads to a reduction in social activities and relationships, changes in physical activities, and elaborate planning and forethought before activities that previously could be done spontaneously.24,41

Although physical and cognitive impairments constrain the subjective well-being of stroke survivors living in the community, social resources can moderate the adverse effects of residual disabilities. Survivors who have adequate social support are less affected by functional dependence.17 Social supports have been found to be associated with a higher quality of life in stroke survivors.29 Social participation is defined as socially oriented sharing of resources and is an essential component of quality of life.11 Therefore, poor resource use may be predictive of decreased quality of life following stroke. Individuals without family or close friends have difficulty reintegrating into prior roles after stroke. Many family members and friends must return to their prior roles several weeks after their loved one’s stroke. This produces a gradual decrease in support over time. This decrease often occurs when home health staff have discharged the client, and additional resources such as transportation are required for outpatient therapy, grocery shopping, and medical appointments. This is a critical time for case management to secure the support of community organizations, transportation agencies, and outpatient therapy services. Too often, home health care is discontinued without further referral to a nearby outpatient facility. Although clients are no longer homebound following home care services, they are often in need of further rehabilitation to address the cognitive and emotional issues to help them return to activities, tasks, and roles in the family, work, and the community.

The overarching barrier to addressing these limitations in participation following stroke is the fact that rehabilitation services are overly focused on addressing the motor and self-care impairments. Therefore, the needs of the younger, less neurologically impaired stroke survivors are typically overlooked. This was confirmed in a recent study conducted by the Cognitive Rehabilitation Research Group (CRRG) at Washington University School of Medicine who assessed all individuals with stroke being served by Barnes-Jewish Hospital Stroke Service over a 10-year period. The CRRG found that in their stroke population (N=7740): (1) 45% of the patients are under the age of 65-years-old and nearly 27% are under the age of 55-years-old; (2) of all the patients who had strokes, 49% had a mild stroke, 32.8% had moderate strokes, 17.9% had a severe stroke, and 6% did not live, as defined by the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS); and (3) of the individuals who had a mild to moderate stroke, 71% were discharged directly home, were discharged with home services only, or were discharged with outpatient services only, because they did not typically display motor or self-care deficits.56 These same individuals have been found to report problems in their ability to reintegrate into their prestroke activities, community roles, and work following their stroke.56 Since it is known that all of the limitations discussed previously can result from a stroke, it is absolutely essential in a client-centered stroke rehabilitation model to identify these limitations across the continuum of care in order to best support clients.

How to foster participation throughout the continuum of care

No one method of treatment fosters participation in all avenues of rehabilitative care. The stroke team requires commitment and creativity to address the issue. The specific modality applied is not what enhances participation (and hopefully quality of life). Enhancement comes through the activities selected and the contexts in which they are performed. Only with a client-centered plan and the incorporation of meaningful activities in rehabilitation can the team foster participation to bring meaning to the individual in the rehabilitation program.

Acute care

In the acute care setting, acting as a triage team member is essential. This requires a thorough assessment battery. Identifying all the impairments that can improve performance in this setting allows for better discharge planning. Detailed evaluation improves the therapists’ abilities to identify impairments from severe to subtle. Too often, assessments in the acute care setting are brief, increasing the potential for error in discharge placement, because at times it is difficult to assess the presence or absence of the more subtle complex impairments (i.e., cognitive dysfunction) in the acute care setting. If it is not possible to do a complete assessment, then it is imperative for the team member to recommend a follow-up assessment before discharge. Sending the individual home with a “clean bill of health” when in fact these subtle impairments may be present can have a devastating effect on the mental and physical health of the individual. The assessment in this phase of treatment must include not only basic measures of motor impairment, cognition, and language, but also those of higher level functions, including balance, visual perception, and executive function. These elements are key to successful reentry into the community, participation in roles and activities done before the stroke, and maintenance of quality of life. Often the most problematic deficits are those not physically obvious. Clients and families are less likely to understand the impact of poor memory, impaired judgment, decreased language function, and limited balance. Translating these deficits to real-life tasks increases the tangibility for clients and their families and facilitates the transition through other avenues of care. Each level of rehabilitation encompasses increasingly complex tasks in varying contexts.

In some instances, clients do not move through acute care quickly. If treatment time is available, performance of basic tasks is critical. The most basic of self-care is required to go to church, to school, or to work. The acute setting is ideal for beginning of basic ADL including bathing, transfers, eating, and toileting, as they are identified as meaningful for the client. Some clients may choose to have an attendant help them with basic ADL. In such cases, goals can evolve around other client-centered tasks. Goals should include items important to the client, such as talking on the phone or visiting with family. Emotional attachment to such activities is great, and a loss or decrease in independence can produce an emotional response that increases disability (see Chapter 1).

Inpatient rehabilitation

According to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research, rehabilitation seeks to help the person with disabilities achieve the highest possible degree of performance. Rehabilitation is comparable to school in which the client is provided an opportunity for instruction, support, protected practice, education, reassurance, direct assistance, and feedback. This is the “planned withdrawal” of support in which services are provided as needed and are removed when no longer needed. The modalities of inpatient rehabilitation treatment are no different from acute care therapy or outpatient therapy; however, the tasks progress to be more difficult. Once the client has mastered a task in a therapeutic context, the conditions are altered to more real-life situations. Inherent in this progression is that the client is the leader. The therapist must recognize the need for preparing clients to go home beyond using basic ADL performance as a discharge criterion, because this prepares clients to do well inside their homes but does not prepare clients to shop, go to work, or to baby-sit a grandchild. The key to remember in the goal-setting process is the full range of tasks and roles to which the client is returning. Furthermore, a prior level of function must be established and well-documented. An occupational history makes it possible to integrate prior activities into the care plan. If the stroke is impairing prior function, the impairment is treatable and reimbursable. If the prior level of function is documented only in terms of basic self-care, clients will not have access to rehabilitation to return them to community life. By identifying what the person did before admission, one identifies goals to achieve after the prior level of function is achieved. The therapist has more time to achieve those goals once an independent level of self-care is achieved. Response to treatment is better if the client is put in the context of something important to them. For example, a client wants to work on writing. The practitioner provides handwriting exercises every day to complete as homework. However, the client never completes the homework. The client often is labeled unmotivated or uncooperative. The key question to ask is the type of writing the client enjoys. Does the client keep a journal? Does the client enjoy crossword puzzles? These require different writing skills.

When a client enters inpatient rehabilitation, an ongoing evaluation of capacities and client goals is imperative. Through identification of higher-level tasks, clients can be challenged outside the walls of the rehabilitation hospital. For example, a client walks down the hallway of the hospital. What is the response of the other therapists, nurses, and housekeepers in the hallway? What if, one week after discharge, an individual is negotiating a shopping mall? Will the persons in the mall have the same response as the hospital staff? A colleague of the author once referred to this concept as “rehab without walls;” providing rehabilitation in the community rather than restricting it to the hospital setting is the best preparation for life after discharge.

Home health

The advantage to home health therapy is that the intervention takes place in the setting where the skills will be applied as they are being learned. One of the obvious goals of home health is to identify the physical barriers to the client’s success in the home environment. However, identification of the cognitive and perceptual barriers that limit performance in the home setting is critical. In addition, clients may perform better in a familiar environment. As in inpatient rehabilitation, therapeutic activities should evolve around client-centered goals and may include yard work, laundry, or cooking. The therapist has a dual role in home health therapy. In addition to helping remediate impairments from the stroke, the therapist modifies the environment to achieve maximum participation in goals. The environmental approach also involves educating those in the home to the person’s capabilities and how they can enable the person to be active to continue the recovery and help the person gain self-management skills. Preparing the client in the home environment is the first step in preparing the client for community reentry. The downfall of home health therapy is the lack of peer support from other stroke clients and minimal client-team interaction. Referral of the client to outpatient therapy or a community support group once the client is no longer restricted to the home setting is recommended.

Outpatient therapy

A good outpatient program involves a multidisciplinary team working with the client to achieve maximum independence in all aspects of life the client indicates as important. Outpatient therapy forces the client to maintain a schedule of therapies, get ready in time for the appointment, arrange transportation to and from the appointment, and follow through with home programs jointly designed with the therapists. To get to therapy, the client must have the physical endurance to participate in the preparation, the travel, and the therapy itself. The cognitive process involves initiation, planning, attention, organization, and sequencing. Before the client reaches the door of the clinic, therapy has already begun.

A complete assessment includes an inventory of activities, responsibilities, and roles the client likes to do and needs to do every day. Clients can identify the activities most important to them. Often outpatient therapy is difficult because of the broad spectrum of possibilities for clients in this setting. Generating a list of the client’s top five goals is recommended. From that point, additional goals can be formulated. In this setting, vocational issues can be addressed. Meeting with the client’s employer is important to address barriers in the workplace. Meeting with and educating the caregiver assists with the identification of barriers the client may not see in the home. Addressing social support issues with family and friends is also important. An important strategy is to find activities that are enjoyable to the client and the caregiver, so they can be involved in activities that they enjoy doing together.

Community reintegration

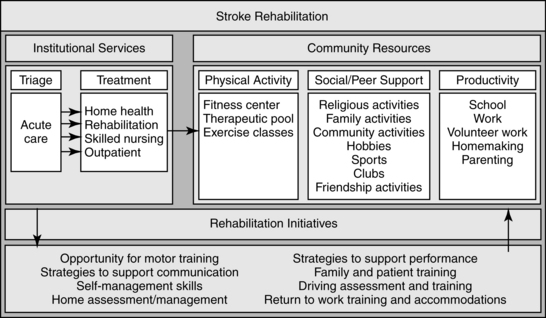

As depicted in Fig. 3-3, an often overlooked but important component to the continuum of care is taking rehabilitation services out into the community. With the age of stroke decreasing, the population of individuals having strokes is increasing engaged in community roles and in particular employment. Inherent in these roles is the need to address more complex activities such as driving, home management, self-management of symptoms, and physical activity. In order to provide client-centered care, this stage in the continuum must be addressed.

CASE STUDY Improving Participation through Occupation

Rosemary awoke one Saturday morning with slurred speech and difficulty walking. She decided to return to bed for additional rest. After sleeping for several more hours, she awoke with left-sided weakness and facial droop, worsening speech, and an inability to walk. She lived alone, was not married, and had no children. She promptly called 911. When paramedics reached her, the dysarthria was severe and she had complete left hemiplegia. She was oriented to her name and where she was but not to the date. In the emergency room, Rosemary was determined to have sustained a large right middle cerebral artery stroke. She was admitted immediately to the hospital and was referred to the stroke team for evaluation and treatment.

Rosemary’s deficits included the following. She was unable to move her left arm or leg. She could roll in bed to her left side using the bed rail, but required maximum assistance to roll to the right. She was dependent with her transfers and basic ADL. She had a left visual inattention and decreased sensation on the left side of her body. She was sleepy and was unable to work with a therapist for more than 30 minutes at a time.

Over her first few days in the hospital, Rosemary began to improve. She was able to tolerate more time in therapy. She could support herself while sitting on the edge of the bed and began to play an active role in her ADL. Rosemary was able to move from her bed to a chair with 75% assistance from the nursing and therapy staff. She was tolerating sitting up in bed and a chair for extended periods throughout the day. The team met to determine the course of Rosemary’s rehabilitation. At the team meeting, Rosemary’s living alone in a two-story home located in the city was revealed. Multiple steps were required to enter. She had two bathrooms in the house; however, the bathroom with a shower was located on the second floor. She had no family locally. Her home was located within walking distance of the doctor and a large grocery store.

Rosemary was a violinist in a local quartet and taught violin on the side. She had few friends other than those in the group with whom she worked. In addition, she was driving (and using public transportation), cooking, shopping, and managing her finances independently before her stroke. Because of these responsibilities and her lack of support at discharge, the team decided Rosemary would benefit from inpatient rehabilitation.

On admission to inpatient rehabilitation, Rosemary was evaluated by nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy staff members. She required moderate to maximum assistance with basic ADL and transfers. She required 100% assistance to walk using a walker and an ankle/foot orthotic. She was able to move from her bed to a chair and back with 75% assistance. Her memory was good; however, she indicated that her attention was not, and she appeared easily distracted in the clinic. She was oriented to person, place, date, and situation. Her speech remained slurred, but her swallow was normal. Rosemary’s endurance improved greatly. She continued to show subtle signs of a left visual inattention, and her left arm continued to be weak throughout. Manual muscle tests indicated strength at the shoulder and elbow was ⅗. Strength in the wrist and hand was ⅖. Sensation was normal to pin prick and temperature. She was diagnosed with depression and was treated medically. The only interests stated in her chart included playing and teaching violin and playing bridge.

Following initial evaluation, the team met to discuss her goals and plans for discharge. Although she was improving daily, her ability to live alone was questionable because of her poor balance, limited attention, and decreased strength. Rosemary and the team set goals for her to be independent with basic ADL and transfers from her bed, the bathtub, and the car. The team chose to address her ability to grocery shop and prepare a simple meal in the microwave. The case manager discussed these goals with Rosemary, and she agreed with the team’s priorities.

At her second week of inpatient rehabilitation, Rosemary was able to dress herself independently using an adaptive strategy. She was walking with some assistance using an ankle/foot orthotic and a walker. She was able to prepare a bowl of cereal, a sandwich, and a microwave dinner. She was taken on trips to the gift shop and grocery store to evaluate her ability to follow a list, obtain objects on the list, and exchange money correctly. These trips were overstimulating to Rosemary, and her depression worsened. She missed her music and felt that her only love in life was the violin. She lived close to the hospital but did not have close friends or family to get her violin. Rosemary desperately wanted to do a home visit and wanted to get her violin; however, the team thought it would increase her depression because her motor impairment would make it impossible for her to play. Despite the discouragement of the team, one of the therapists brought in a violin for Rosemary to play. The therapist went to a quiet treatment room with Rosemary.

Although Rosemary was hesitant, she removed the violin from the case and asked the therapist to leave the room. She did not want anyone else to hear her attempts to play the violin for the first time. As the therapist closed the door, she could see the fear on Rosemary’s face. The therapist returned to the room after 10 minutes. What she heard was amazing. When she opened the door, Rosemary was playing the violin. Her face beamed with pride as the team came in to hear her play. What they all felt was impossible was the key motivator for Rosemary. She began to practice several times a day.

At week 3 of her impatient rehabilitation, the team decided that Rosemary’s progress had reached a plateau and that it was time to schedule discharge. Rosemary did not want to burden her small group of friends. She made the decision to transfer to a residential facility until her status improved. At discharge, she was independent with ADL using some adaptive strategies and independent with transfers using adaptive equipment. Some assistance was required with walking using a quad cane and an ankle/foot orthotic, her speech remained slurred, and her facial droop persisted. Muscle strength throughout her arm was ⅘, with poor coordination distally. She was able to balance a simulated checkbook, prepare simple meals independently (she was most comfortable with the microwave), and play her violin, but she could not drive. Rosemary had difficulty with higher-level tasks involving complex sequencing and organization, and performing multiple tasks at once was difficult for her.

Rosemary transferred to a residential facility for two months before returning home. At that time, she was referred to outpatient therapy. Rosemary remained unable to drive but was proficient at using public transportation. She was independent with most basic and instrumental ADL. A friend would pick her up weekly to take her to the grocery store. Her motor status was unchanged from her inpatient rehabilitation discharge. She continued to show ⅘ muscle strength proximally and improved coordination in her hand and fingers. Her speech was normal, and speech therapy was not required. Her higher-level executive functions were nearly normal. Her balance continued to be problematic, but she was walking with a straight cane and an ankle/foot orthotic. A comprehensive evaluation of her activities and quality of life revealed the following. Her Activity Card Sort showed that she had retained only 35% of the activities she had done before the stroke, with the greatest loss in the areas of social activity and high-demand leisure activity. Rosemary’s priorities indicated by the Activity Card Sort included the following (in order of importance): playing a musical instrument (her violin), driving, shopping, visiting with friends, and traveling. The Stroke Adapted Sickness Impact Profile (SA-SIP) revealed a score of 15 out of 30. Her score was in the midrange, indicating a decreased quality of life. Some of the problematic areas included “body care and movement,” “mobility,” and “ambulation.” Rosemary received a score of 28 on the Reintegration to Normal Living Index. The scoring range of the index is from 11 to 55. A lower score indicates lower satisfaction. Rosemary’s score was in the midrange, indicating some difficulty. Low scores included items regarding travel, spending days occupied with work that is important, getting around the community, and being comfortable in the company of others. The Community Integration Questionnaire indicated some severe difficulties in areas of home, social, and productivity. Rosemary’s home integration score was a 3.6 out of 10 points, her social integration score was a 3 out of 12 points, her productivity score was a 1 out of 6 points, and her total score was 7.75 out of 28 points, indicating a poor level of independence. The team met with Rosemary to set her goals for outpatient therapy. Scores from her assessments were discussed. Rosemary identified that her primary barriers to satisfaction were her decreased ability to play her violin and her inability to drive. Because she was unable to drive, she had difficulty shopping, meeting friends, and traveling. Although she had friends to drive her to events or was able to use public transportation close to home, Rosemary felt a decrease in autonomy. This decrease in autonomy and an inability to continue her work added to her depression. Goals were set according to priorities outlined by Rosemary in her Activity Card Sort. The team set goals with Rosemary to improve her motor performance to improve her violin playing and walking independently while carrying a violin case. A driving evaluation was completed and indicated that she was able to return to driving. A trip to the grocery store and the mall allowed the therapists to determine her best method of negotiating the mall and for carrying bags to the car after shopping. Rosemary returned to therapy the second week with her violin. After an additional week of therapy, Rosemary had met her goals for playing the violin, driving, shopping, and visiting with friends. On discharge from outpatient therapy, Rosemary was able to teach violin again and hoped to return soon to concert performances. Her scores on the SA-SIP had increased to 3 out of 30. Her Community Integration Questionnaire scores returned to normal, and her activity level as measured by the Activity Card Sort returned to 85% of what it was before her stroke.

Review questions

1. Describe the concepts encompassed in the word participation and the factors that affect participation.

2. What are the categories of occupation?

3. How may self-efficacy affect a client’s recovery?

4. Define quality of life. What is the relationship between quality of life and activity and participation?

5. Describe some common assessments of participation and quality of life.

6. What are some common barriers limiting participation and quality of life?

7. How can therapists address participation through the continuum of care from acute care to the community?

8. What may have been done differently with Rosemary’s care to facilitate her recovery? What did the therapists do well with Rosemary?

1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Post-stroke rehabilitation. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1995.

2. American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Occupational therapy practice framework. Domain and process (2nd ed.). Am J Occup Ther. 2008:62;6:625-683.

3. Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977.

4. Banks P, Pearson C. Improving services for younger stroke survivors and their families. (website) www.chss.org.uk/pdf/research/Young_stroke_study_2003.pdf, 2007. Accessed October 30

5. Baum CM, Edwards DF. Activity card sort, ed 2. Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press; 2008.

6. Baum CM, Edwards DF, Morrow-Howell N. Identification and measurement of productive behaviors in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Gerontologist. 1993;33(3):403-408.

7. Baum CM, Law M. Occupational therapy practice. focusing on occupational performance. Am J Occup Ther. 1997:51;4:277-288.

8. Berglund AL, Eisemann M, Lalos O. Personality characteristics of stress incontinent women. a pilot study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1994:15;3:165-170.

9. Bergner M, Bobbitt RA, Carter WB, et al. The Sickness Impact Profile. development and final revision of a health status measure. Med Care. 1981:19;8:787-805.

10. Brittain KR, Peet SM, Castleden CM. Stroke and incontinence. Stroke. 1998;29(2):524-528.

11. Bukov A, Maas I, Lampert T. Social participation in very old age. cross sectional and longitudinal findings from BASE. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002:57;6:510-517.

12. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists. Guidelines for the client-centered practice of occupational therapy. Toronto: The Association; 1995.

13. Chan C, Lee T. Validity of the Canadian occupational performance measure. Occup Ther Int. 1997;4:229-247.

14. Christiansen CH. A social-psychological approach to understanding self-care. In: Christiansen CH, editor. Ways of living: self-care strategies for special needs. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, 1994.

15. Christiansen CH, Baum C. Occupational therapy. overcoming human performance deficits. Thorofare, NJ: Slack. 1997.

16. Christiansen CH, Clark F, Kielhofner G, et al. Position paper. occupation. Am J Occup Ther. 1995:49;10:1015-1018.

17. Clarke P, Marshall V, Black SE, et al. Well-being after stroke in Canadian seniors. findings from the Canadian study of health and aging. Stroke. 2002:33;4:1016-1028.

18. Duncan PW, Lai SM, Tyler D, et al. Evaluation of proxy responses to the Stroke Impact Scale. Stroke. 2002;33(11):2593.

19. Duncan PW, Wallace D, Lai SM, et al. The Stroke Impact Scale version 2.0. evaluation of reliability, validity, and sensitivity to change. Stroke. 1999:30;10:2131-2140.

20. Fidler GW, Fidler JW. Doing and becoming. purposeful action and self-actualization. Am J Occup Ther. 1978:32;5:305-310.

21. Gage M, Polatajko H. Enhancing occupational performance through an understanding of perceived self-efficacy. Am J Occup Ther. 1994;48(5):452-461.

22. Gunter BG, Stanley J. Theoretical issues in leisure study. In: Gunter BG, Stanley J, St Clair R, editors. Transitions to leisure: conceptual and human issues. Landham, MD: University Press of America, 1985.

23. Hochstenbach J, Anderson P, van Limbeek J, et al. Is there a relation between neuropsychologic variables and quality of life after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(10):1360-1366.

24. Hunskaar S, Vinsnes A. The quality of life in women with urinary incontinence as measured by the Sickness Impact Profile. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(4):378-382.

25. Iso-Ahola SE. Basic dimensions of definitions of leisure. J Leisure Res. 1979;1:28-39.

26. Katz N. Cognitive rehabilitation: models for intervention in occupational therapy. Boston Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1992.

27. Katz N, Karpin H, Lak A, et al. Participation and occupational performance. reliability and validity of the Activity Card Sort. Occup Ther J Res. 2003:23;1:10-17.

28. Kielhofner G. Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2004.

29. King RB. Quality of life after stroke. Stroke. 1996;27(9):1467-1472.

30. Koch L, Egbert N, Coeling H, Ayers D. Returning to work after the onset of illness. experiences of right hemisphere stroke survivors. Rehabil Couns. 2005:48;4:209-218.

31. Lai S, Studenski S, Duncan P, et al. Persisting consequences of stroke measured by the stroke impact scale. Stroke. 2002;33(7):1840-1850.

32. Law M, Baptiste S, Mills J. Client–centred practice. what does it mean and does it make a difference. Can J Occup Ther. 1995:62;5:250-257.

33. Law M, Baum CM, Dunn W. Measuring occupational performance: supporting best practice in occupational therapy. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2001.

34. Law M, Cooper BA, Strong S, et al. The person-environment-occupation model. a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther. 1996:63;1:9-23.

35. Lawton MP. The functional assessment of elderly people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1971;19(6):465-481.

36. Levine MN. Quality of life in stage II breast cancer. an instrument for clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 1988:6;12:1798-1810.

37. Mathiowetz V, Bass-Haugen J. Motor behavior research. implications for therapeutic approaches to central nervous system dysfunction. Am J Occup Ther. 1994;48:733-745.

38. McColl MA, Gerein N, Valentine F. Meeting the challenges of disability. models for enabling function and well-being. Christiansen CH, Baum CM, editors. Occupational therapy: enabling function and well being, ed 2, Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1997.

39. Moore A. The band community. synchronizing human activity cycles for group cooperation. Zemke R, Clark F, editors. Occupational science: the evolving discipline. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

40. Murphy B, Herrman H, Hawthorne G, et al. Australian WHOQoL instruments: User’s manual and interpretation guide. Melbourne: Australian WHOQoL Field Study Centre; 2000.

41. Naughton J, Wyman JF. Quality of life in geriatric patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Am J Med Sci. 1997;314(4):219-227.

42. Neugarten BL, Havinghurst RJ, Tobin SS. Measure of life satisfaction. J Gerontol. 1961;16(2):134-143.

43. Patel M, Coshall C, Lawrence E, et al. Recovery from poststroke urinary incontinence. associated factors and impact on outcome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001:49;9:1229-1233.

44. Primeau L. Work versus non-work. the case of household work. Zemke R, Clark F, editors. Occupational science: the evolving discipline. Philadelphia: FA Davis, 1996.

45. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68-78.

46. Stuart H. Stigma and work. Healthcare Papers. 2005;5(2):100-111.

47. Takata N. The play milieu. a preliminary appraisal. Am J Occup Ther. 1971;25:281-284.

48. Tatemichi T, Desmond D, Stern Y, et al. Cognitive impairment after stroke. frequency, patterns, and relationship to functional abilities. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:202-207.

49. Trombly CA. Occupation. purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms. The 1995 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Am J Occup Ther. 1995;49:960-972.

50. Valvanne J, Juva K, Erkinjuntti T, et al. Major depression in the elderly. a population study in Helsinki. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996:8;3:437-443.

51. van Straten A, de Haan RJ, Limburg M, et al. A stroke-adapted 30–item version of the Sickness Impact Profile to assess quality of life (SAS-SIP30). Stroke. 1997;28:2155-2161.

52. Vestling M, Tufvesson B, Iwarsson S. Indicators for return to work after stroke and the importance of work for subjective well-being and life satisfaction. J Rehabil Med. 2003;35(3):127-131.

53. Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36–item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473-483.

54. Wilcock A. A theory of the human need for occupation. Occup Sci Aust. 1993;1(1):17-24.

55. Willer B, Linn R, Allen K. Community integration and barriers to integration for individuals with brain injury. In: Finlayson M, Garner S, editors. Brain injury rehabilitation: clinical considerations. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1993.

56. Wolf T, Baum CM, Connor L. Changing face of stroke. Implications for occupational therapy practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2009:63;5:621-625.

57. Wood-Dauphinee SL, Opzoomer MA, Williams JI, et al. Assessment of global function. The Reintegration to Normal Living Index. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988:69;8:583-590.

58. Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams J. Reintegration to normal living as a proxy to quality of life. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(6):491-502.

59. World Health Organization. The International Classification of Function, Disability and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

61. World Health Organization Quality of Life Group. Development of the 3 WHO quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551-558.