Perspectives of Pediatric Nursing

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

Define the terms mortality and morbidity.

Define the terms mortality and morbidity.

Identify two ways that knowledge of mortality and morbidity can improve child health.

Identify two ways that knowledge of mortality and morbidity can improve child health.

List three major causes of death during infancy, early childhood, later childhood, and adolescence.

List three major causes of death during infancy, early childhood, later childhood, and adolescence.

List two major causes of illness during childhood.

List two major causes of illness during childhood.

Describe five broad functions of the pediatric nurse in promoting the health of children.

Describe five broad functions of the pediatric nurse in promoting the health of children.

HEALTH CARE FOR CHILDREN

The major goal for pediatric nursing is to improve the quality of health care for children. There are 73 million children 0 to 18 years of age in the United States, comprising 25% of the population (Dougherty, Meikle, Owens, and others, 2005). The health of children living in the United States has improved in numerous areas, including vaccination coverage, adolescent birth rates, and child mortality. Although child mortality rates have declined dramatically, millions of families have no child health insurance, resulting in lack of access to care and health promotion services. And although most American children are healthy, disparities related to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geography prevail. Patterns of child health are shaped by medical progress and societal trends (Dougherty, Meikle, Owens, and others, 2005; Wise, 2004, 2005). The Healthy People 2010 Leading Health Indicators (Box 1-1) provide a framework for identifying essential components for child health promotion programs designed to prevent future health problems in our nation’s children.

The National Children’s Study is the largest long-term study of children’s health and development conducted in the United States. The study is designed to follow 100,000 children and their families from birth to age 21 to understand the link between children’s environments and their physical and emotional health and development (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2004). It is hoped that a study of this magnitude will provide innovative interventions for families, children, and health care providers to eradicate unhealthy diets, dental caries, and childhood obesity, and bring a significant reduction in violence, injury, substance abuse, and mental health disorders among the nation’s children. This study supports the Healthy People 2010 primary goals to increase the quality and years of healthy life and eliminate health disparities related to race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2007).

HEALTH PROMOTION

Many of tomorrow’s leading causes of death, disease, and disability (cardiovascular disease, cancer, chronic lung diseases, depression, violence, substance abuse, injuries, nutritional deficiencies, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [HIV/AIDS]) can be significantly reduced in children and adolescents by preventing six categories of behavior (World Health Organization [WHO], 2007):

2. Behavior that results in injury and violence

4. Dietary and hygienic practices that cause disease

6. Sexual behavior that causes unintended pregnancy and disease

Child health promotion provides opportunities to reduce differences in current health status among members of different groups and ensure equal opportunities and resources to enable all children to achieve their fullest health potential.

NUTRITION

Nutrition is an essential component for healthy growth and development, and its promotion begins at birth. Human milk is the preferred form of nutrition for all infants. Breastfeeding provides the infant with micronutrients, immunologic properties, and several enzymes that enhance digestion and absorption of these nutrients. Many working mothers tend to wean their infants early to avoid the hassle of breast pumping during the workday. However, over the past several years, there has been resurgence in breastfeeding due to the education of mothers and fathers regarding its benefits.

Young children tend to establish eating habits during the first 2 to 3 years of life, and the nurse is instrumental in guiding parents in the selection of nutritious foods. During childhood, the eating preferences and attitudes related to food habits are established by family influences and culture. During adolescence, parental influence diminishes as the adolescent make food choices related to peer acceptability and sociability; these choices may be detrimental to the chronically ill child with diabetes, hypertension, or heart or renal disease.

Unhealthy diets are common among lower income families, often because of the lack of nutritious fresh fruits and vegetables and adequate milk and protein intake. In addition, the lifestyles of homeless and migrant children place these populations at risk for inadequate food, causing nutrient deficiencies, developmental and growth delays, depression, hunger, and behavior problems.

DENTAL CARE

The Healthy People 2010 project reports that nearly one in five children between the ages of 2 and 4 years, particularly Latino children, has visible cavities (Edelstein, 2005). Dental caries is the single most common chronic disease of childhood (Heuer, 2007). The most common form of early dental disease is early childhood caries, which may begin at the first birthday and progress to pain and infection within the first 2 years of life (Edelstein, 2005). Preschoolers of low-income families are twice as likely to develop tooth decay and only half as likely to visit the dentist as other children (Edelstein, 2005). Since this is a preventable disease, nursing plays an essential role in promoting early tooth care by instructing the children and parents on practicing dental hygiene beginning with the first tooth eruption; drinking fluoridated water, including bottled water; and instituting early dental preventive care.

IMMUNIZATIONS

The two public health interventions that have had the greatest impact on world health are clean drinking water and vaccines. Differences in immunizations rates exist among children of different races and ethnicities, family incomes, states, types of vaccinations, and adolescents and younger children (Dougherty, Meikle, Owens, and others, 2005). A child’s immunization record should be reviewed at each clinic visit, and parents should be instructed to keep immunizations current, reinforcing the Healthy People 2010 goal of vaccinating 90% of 2-year-olds (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2007).

CHILDHOOD HEALTH PROBLEMS

The health of the nation’s children continues to improve in many areas, such as lower pregnancy rates for adolescents and expanded vaccine coverage. However, changes in modern society, including disruptive influences on the family, the explosion of technology, and the proliferation of information systems, are influencing the emergence of significant medical problems that affect the health of children (Lichter, 2005). Recent concern has focused on groups of children who have increased morbidity: homeless and immigrant children, children living in poverty, low-birth-weight (LBW) children, children with chronic illnesses, foreign-born adopted children, and children in daycare centers. A number of factors place these groups at risk for poor health. A major cause is barriers to health care, especially for the homeless, the poverty stricken, and those with chronic health problems. Other factors include improved survival of children with chronic health problems, particularly infants of very low birth weight (VLBW).

In addition to disease and injury, children face behavior, social (family), and educational problems that are referred to as the new morbidity or pediatric social illness. These problems (e.g., poverty, violence, aggression, noncompliance, school failure, and adjustment to divorce or bereavement) interfere with children’s social and academic development. Mental health issues also affect our children and adolescents. One out of five has mental health problems, and one out of 10 has serious emotional problems that affect daily functioning (Coury, 2006). Examples of increasing pediatric problems include obesity, type 2 diabetes, injuries, violence, substance abuse, and emotional and mental health problems during adolescence.

OBESITY AND TYPE 2 DIABETES

Childhood obesity is the most common nutritional problem among American children and is increasing in epidemic proportions, along with type 2 diabetes (Yensel, Preud’Homme, and Curry, 2004). Obesity in children and adolescents is defined as a body mass index at or greater than the 95th percentile for youth of the same age and gender (Dietz, 2005; Covington, Cybulski, Davis, and others, 2001). The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey reported that the prevalence of overweight children doubled and the prevalence of overweight adolescents tripled between 1980 and 2000 (Dietz, 2005).

Advancements in entertainment and technology such as television, computers, and video games have contributed to the growing childhood obesity problem in the United States. Approximately 63% of 8- to 18-years-olds have a television in their bedrooms and watch television an average of 4 hours a day (Robinson and Sargent, 2005). Minority populations, especially African-American and Hispanic children from families of low socioeconomic status, watch more than 4 hours of television daily, exacerbating the effects of sedentary activity with intake of high-caloric, fatty foods (Fitzgibbon and Stolley, 2004).

Lack of outside physical activity because of unsafe environments and inconvenient facilities for physical activities, combined with easy assess to video games and television within the home, tend to promote obesity among low-income minority children. Overweight youth, especially of Hispanic, African-American, and Native American descent, have increased risk for developing diabetes, insulin resistance, hypertension, and heart disease (Jackson, 2001; Yensel, Preud–Homme, and Curry, 2004) (Fig. 1-1). A major nursing health prevention focus, consistent with the Healthy People 2010 primary goals, is the reduction of overweight children, ages 6 to 19 years, from the current 20% in all ethnic groups, to less than 6% (Duderstadt, 2004; US Department of Health and Human Services, 2007).

CHILDHOOD INJURIES

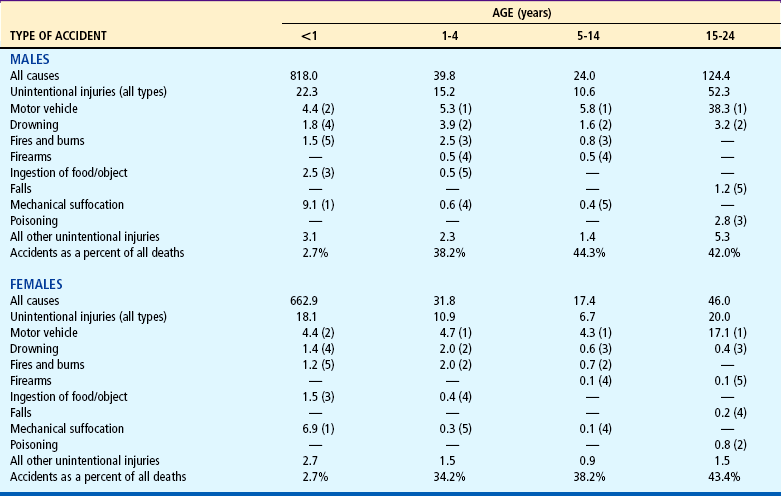

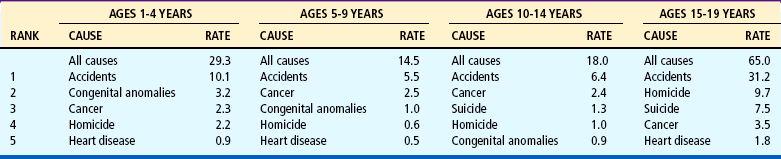

Injuries are the most common cause of death and disability to children in the United States (Schnitzer, 2006) (Table 1-1). Unintentional injuries among children ages 19 and under have dropped to 39%, and the violent death rate has dropped 36% in the same age bracket; however, the trend has now plateaued (Rivara, 2005). Despite the decrease in injuries to children, motor vehicle (MV)–related accidents continue as the most common cause of death in children older than 1 year of age. As children grow older, the percentage of deaths from injuries increases. The most common types of unintentional injuries, in addition to MV accidents, include drowning, burns, and firearm accidents. Many childhood injury fatalities could be avoided. For example, the majority of bicycling deaths are from head injuries. Although helmets reduce the risk of head injury by 85%, few children wear them (National Safety Council, 2000).

TABLE 1-1

Mortality from Leading Types of Unintentional Injuries, United States, 1997 (Rate Per 100,000 Population in Each Age-Group)

Modified from National Safety Council: Injury facts, Itaska, Ill, 2000, The Council. Data from National Center for Health Statistics.

The type of injury and the circumstances surrounding it are closely related to normal growth and developmental behavior (Box 1-2). As children develop, their innate curiosity impels them to investigate activities and to mimic the behavior of others. This is essential to acquire competency as an adult, but it predisposes children to numerous hazards.

The child’s developmental stage partially determines the types of injuries that are most likely to occur at a specific age and helps provide clues to preventive measures. For example, small infants are helpless in any environment. When they begin to roll over or propel themselves, they can fall from unprotected surfaces. The crawling infant, who has a natural tendency to place objects in the mouth, is at risk for aspiration or poisoning. The mobile toddler, with the instinct to explore and investigate and the ability to run and climb, may experience falls, burns, and collisions with objects. As children grow older, their absorption with play makes them oblivious to environmental hazards such as street traffic or water. The need to conform and gain acceptance compels older children and adolescents to accept challenges and dares. Although the rate of injuries is high in children less than 9 years of age, most fatal injuries occur in later childhood and adolescence.

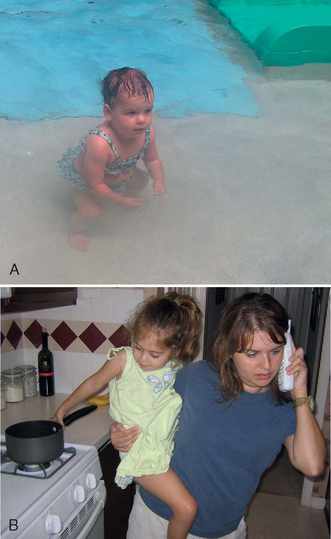

The pattern of deaths caused by unintentional injuries, especially from MVs, drowning, and burns, is remarkably consistent in most Western societies. However, the United States far exceeds other countries in the number of violent deaths. The leading causes of death from injuries for each age-group according to sex are presented in Table 1-1. Although the incidence of violence is increasing in the United States, it is important to note that accidents continue to account for more than three times as many teen deaths as any other cause (Heron, 2007). Fortunately, prevention strategies such as the use of car restraints, bicycle helmets, and smoke detectors have resulted in a significant decrease in fatalities for children. Currently, all states have enacted legislation requiring young children to be properly restrained in MVs. Despite safety efforts, the overwhelming cause of death in children is MV-related fatalities, including occupant, pedestrian, bicycle, and motorcycle deaths. In fact, MV-related accidents now account for more than half of all injury deaths (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2001). The majority of deaths from injuries occur in males. Even though the percentage of infants dying from MV injuries is small compared with the total number of deaths in that age-group, children under 1 year of age still have a high death rate from MV accidents, primarily from a failure to use proper restraints (Fig. 1-2).

FIG. 1-2 Motor vehicle injuries are the leading cause of death in children older than 1 year of age. The majority of fatalities involve occupants who are unrestrained.

Pedestrian injuries in children account for significant numbers of MV-related deaths. Most pedestrian injuries occur at midblock, at intersections, in driveways, and in parking lots. Driveway injuries typically involve small children and large vehicles backing up. Parents may not be alert to the dangers leading to such injuries and consequently fail to protect their children.

Bicycle injuries are another important cause of childhood deaths. Children ages 5 to 9 years are at greatest risk of bicycling fatalities. The majority of bicycling deaths are from head injuries. Helmets reduce the risk of head injury by 85%, but few children wear helmets (National Safety Council, 2000). Community-wide bicycle helmet campaigns and mandatory-use laws have resulted in significant increases in helmet use. Still, issues such as stylishness, comfort, and social acceptability remain important factors in compliance. Nurses can educate children and families about pedestrian and bicycle safety. In particular, school nurses can promote helmet wearing and encourage peer leaders to act as role models.

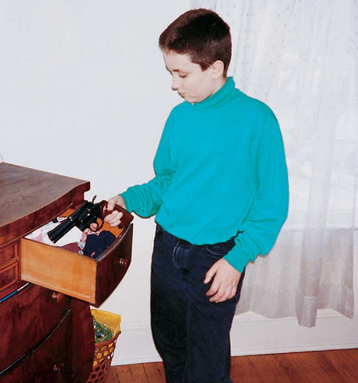

Drowning and burns are among the top five leading causes of deaths for males and females throughout childhood (Fig. 1-3). In addition, improper use of firearms is a major cause of death among males (Fig. 1-4). During infancy, more males succumb to death from aspiration or suffocation than do females (Fig. 1-5). More than half of all poisonings reported in 1999 occurred in children under 6 years of age (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2001) (Fig. 1-6). By ages 4 to 5 years, unintentional poisonings are uncommon. Another increase occurs in the 15- to 24-year age-group, where poisoning is the third leading cause of death in males and second in females. Poisoning in this age-group is typically intentional and usually represents death from suicide (especially among females) or drug abuse.

FIG. 1-3 A, Drowning is one of the leading causes of death. Children left unattended are unsafe even in shallow water. B, Burns are among the top three leading cause of death from injury in children ages 1 to 14 years.

VIOLENCE

Each day, 10 children in the United States are murdered by gunfire, equivalent to approximately one child every 2½ hours (Groves, 2005). Strikingly higher homicide rates are found among minority populations, especially African-American children. Violence permeates American households through television programs, commercials, video games, and movies that tend to desensitize the child toward violence. By the time preschoolers graduate from high school, they will have viewed more than 200,000 violent acts on television (Groves, 2005). Violence also permeates the schools with the availability of guns and illicit drugs and the presence of gangs, exemplified by one of the deadliest school shootings in U.S. history at Columbine High School in Colorado in 1999 (Fisher and Kettl, 2003). Although declines from peak levels in 1993 have been observed in serious violent crimes with children as victims or as offenders (ages 12 to 17) (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2007), assessment of high-risk behaviors in our youth must continue to be a major focus of health promotion.

The causes of increased violence against children and self-inflicted violence are not fully understood. In young children the increase in homicide may represent a more accurate identification of child abuse. In all cases the problem of child homicide is extremely complex and involves numerous social, economic, and other influences. Prevention lies in better understanding of the social and psychologic factors that lead to the high rates of homicide and suicide. Nurses need to be especially aware of young people who are depressed, repeatedly in trouble with the criminal justice system, or associated with groups known to be violent. Prevention requires identification of these young people and therapeutic intervention by qualified professionals.

Pediatric nurses can assess children and adolescents for risk factors related to violence. Families that own firearms must be educated about their safe use and storage. The presence of a gun in a household increases the risk of suicide by about fivefold and the risk of homicide by about threefold. Legislative efforts may focus on preventing specific groups, such as felons and children, from having access to firearms. Technologic changes such as childproof safety devices and loading indicators could improve the safety of firearms (see Community Focus box).

SUBSTANCE ABUSE

Risk-taking behaviors, particularly in males, tends to begin in the first decade of life and continue into adolescence with drinking alcohol while driving, speeding, carrying a weapon, or using illicit drugs. Alcohol and illicit drug use occurs most commonly between ages 12 and 17 years and is associated with violence and injury (Jackson, 2001). About 10.9 million youths between the ages of 12 and 20 (primarily males) report drinking alcohol, with nearly 19.2% reported as being binge drinkers and 6.1% as being heavy drinkers (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004). Sixty-six percent of youths who drank alcohol heavily and 52% of youths from 12 to 17 years of age who smoked cigarettes daily were also users of illicit drugs (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004). An estimated 2.6 million new marijuana users emerged in 2002, with 69% under age 18 years. Use of marijuana, the most commonly used illicit drug, declined slightly from 20.6% in 2002 to 19.6% in 2003 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007). During the same period, decreases were also seen in use of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) (1.3% to 0.6%), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, or ecstasy) (2.2% to 1.3%), and methamphetamine (0.9% to 0.7%) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2007). The slight decline in American youth’s illicit drug use is attributed to education regarding the adverse effects of illicit drugs, parental disapproval, decreased availability of drugs, and consistent participation in church and organized activities such as scouts and sports.

MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS

Mental health problems affect one out of five school-age children in the United States. Children and adolescents with mental health problems are more likely to drop out of school than those with other disabilities (Kelleher, 2005). One of the most common mental health problems is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Kelleher, 2005). ADHD is characterized by inattentiveness, impulsivity, and at times hyperactivity occurring in children as early as 3 years of age (Medd, 2003). ADHD affects every aspect of the child’s life, but is most obvious in the classroom. Family education, counseling, medication, proper classroom placement, environmental manipulation, and behavior therapy are important management strategies for these children.

Suicide is defined as a self-chosen death and is the third leading cause of death in children ages 10 to 19 (Doucette, 2005). The American Association of Suicidology (2007) estimates that in a typical high school classroom, three students (one boy and two girls) have likely made a suicide attempt in the last year. Suicide is a preventable occurrence, placing a heavy burden on the nurse’s ability to identify the at-risk child or adolescent who may display mental health and emotional problems. There is a need to more completely integrate a system of care for children and adolescents that will provide integrated medical and mental health services that promote health (Coury, 2006).

MORTALITY

figures describing rates of occurrence for events such as death in children are referred to as vital statistics. Mortality statistics describe the incidence or number of individuals who have died over a specific period. They are usually presented as rates per 100,000. Mortality rates are calculated from a sample of death certificates. In the United States the National Center for Health Statistics, under the Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, is responsible for the collection, analysis, and dissemination of data on the health of the American people (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2007).

The tabulation of race for live births (the denominator of infant mortality rates) has changed from race of child to race of mother. Formerly, to determine the child’s race in mixed parentage in which one parent was Caucasian, the child was assigned the race of the other parent. In general, this change in assignment of race from child to mother has resulted in more Caucasian births and fewer non-Caucasian births. However, infant deaths are recorded by the decedent’s race, resulting in a lower infant mortality rate for Caucasians than non-Caucasians. As a result of these changes in the early 1990s, figures for births, deaths, and infant mortality rates by race are not comparable to statistics reported before these changes were made.

INFANT MORTALITY

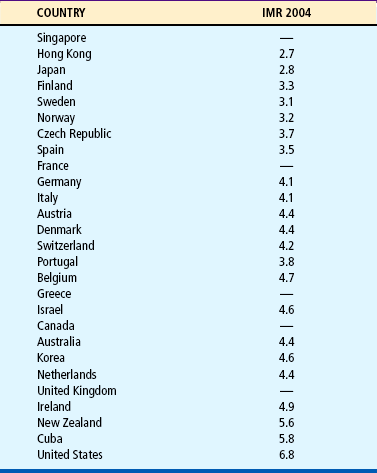

The infant mortality rate is the number of deaths during the first year of life per 1000 live births. It may be further divided into neonatal mortality (<28 days of life) and postneonatal mortality (28 days to 11 months). In the United States infant mortality has decreased dramatically. At the beginning of the twentieth century the rate was approximately 200 infant deaths per 1000 live births. In 2004 the infant mortality rate was 6.78 deaths per 1000 live births (Martin, Kung, Mathews, and others, 2008).

From a worldwide perspective, however, the United States lags behind other nations in reducing infant mortality. In 2004 the United States ranked last among 27 nations that have a population of at least 2.5 million and had infant mortality rates equal to or lower than that of the United States in 2000. Hong Kong, Singapore, and Japan have the three lowest rates, with the United States ranked last behind Cuba and Croatia (Martin, Kung, Mathews, and others, 2008) (Table 1-2).

TABLE 1-2

Infant Mortality Rate (IMR) for Countries of >2,500,000 Population with IMR Equal to or Less Than the U.S. Rate for 2004 (Rate Per 1000 Live Births)

From Martin JA, Kung HC, Mathews TJ, and others: Annual summary of vital statistics: 2006, Pediatrics 121(4):788-801, 2008. —, Data are not available.

Birth weight is considered the major determinant of neonatal death in technologically developed countries. There is a relationship between LBW and infant morbidity and mortality (Martin, Kochanek, Strobino, and others, 2005). The lower the birth weight, the higher the mortality. The relatively high incidence of LBW (<2500 g [5.5 pounds]) in the United States is considered a key factor in its higher neonatal mortality rate when compared with other countries. Access to and the use of high-quality prenatal care is a promising preventive strategy to decrease early delivery and infant mortality. Other factors that increase the risk of infant mortality include African-American race, male gender, short or long gestation, maternal age, and lower level of maternal education (Martin, Kochanek, Strobino, and others, 2005).

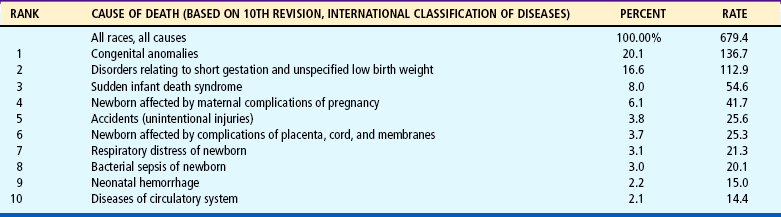

As Table 1-3 demonstrates, many of the leading causes of death during infancy continue to occur during the perinatal period. The first four causes–congenital anomalies, disorders relating to short gestation and unspecified LBW, sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), and newborn affected by maternal complications of pregnancy–accounted for about half (49%) of all deaths of infants under 1 year of age (Heron, 2007). LBW is a major indicator of infant health and a significant predictor of infant mortality (Martin, Kung, Mathews, and others, 2008). Many birth defects are associated with LBW, and reducing the incidence of LBW will prevent congenital anomalies. Infant mortality resulting from HIV infection decreased significantly during the 1990s. In 2003 HIV/AIDS accounted for less than 0.2% of all infant deaths (Hoyert, Heron, Murphy, and others, 2006).

TABLE 1-3

Infant Mortality Rate and Percentage of Total Deaths for 10 Leading Causes of Infant Death in 2004 (Rate Per 1000 Live Births)

Modified from Heron M: Deaths: leading causes for 2004, Natl Vital Stat Rep 56(5):1-96, 2007.

When infant death rates are categorized according to race, a disturbing difference is seen. Infant mortality for Caucasians is considerably lower than for all other races in the United States, with African Americans having twice the rate of Caucasians. Although the infant mortality of all racial groups increased slightly between 2001 and 2002, the gap has remained constant, with the infant mortality rate expressed as a ratio of African-American to Caucasian deaths being relatively unchanged for the past decade (Martin, Kochanek, Strobino, and others, 2005). The LBW rate is also much higher for African-American infants than for any other group. One encouraging note is that the gap in mortality rates between Caucasian and non-Caucasian races other than African Americans has narrowed in recent years. Infant mortality rates for Hispanics and Asian–Pacific Islanders have decreased dramatically during the past 2 decades (Martin, Kochanek, Strobino, and others, 2005).

CHILDHOOD MORTALITY

Death rates for children older than 1 year of age have always been lower than those for infants (see Table 1-2). Children ages 5 to 14 years have the lowest rate of death. However, a sharp rise occurs during later adolescence, primarily from injuries, homicide, and suicide (Table 1-4). In 2005 these causes were responsible for approximately 75% of deaths in teenagers and young adults 15 to 19 years old (Martin, Kung, Mathews, and others, 2008). The trend in racial differences that occurs in infant mortality is also apparent in childhood deaths for all ages and for both sexes. Caucasians have fewer deaths for all ages, and male deaths outnumber female deaths.

TABLE 1-4

Five Leading Causes of Death in Children in the United States: Selected Age Intervals, 2005 (Rate Per 100,000 Population)

Modified from Martin JA, Kung HC, Mathews TJ, and others: Annual summary of vital statistics—2006, Pediatrics 121(4):788-801, 2008.

After 1 year of age, the cause of death changes dramatically, with unintentional injuries (accidents) being the leading cause from the youngest ages to the adolescent years. Violent deaths have been steadily increasing among young people ages 10 through 25 years, especially African Americans and males. Homicide is the second leading cause of death in the 15- to 19-year age-group (see Table 1-4). Children 12 years of age and older tend to be killed by nonfamily members (acquaintances and gangs, typically of the same race) and most frequently by firearms. In 2004 African-American adolescent males were twice as likely to die as a result of a firearm injury as an MV injury (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2007). Suicide, a form of self-violence, is the third leading cause of death among children and adolescents 10 to 19 years of age.

MORBIDITY

Measurements of the prevalence of a specific illness in the population at a particular time are known as morbidity statistics. Morbidity statistics are generally presented as rates per 1000 population. Unlike mortality, morbidity is difficult to define and may denote acute illness, chronic disease, or disability. Source of data also influences the statistics. Common sources include reasons for visits to physicians; diagnoses for hospital admission; or household interviews such as the National Health Interview Survey, Child Health Supplement. Unlike death rates, which are updated annually, morbidity statistics are revised less frequently and do not necessarily represent the general population.

CHILDHOOD MORBIDITY

Acute illness is defined as an illness with symptoms severe enough to limit activity or require medical attention. Respiratory illness accounts for approximately 50% of all acute conditions, 11% are caused by infections and parasitic disease, and 15% are caused by injuries. The chief illness of childhood is the common cold.

The types of diseases that children contract during childhood vary according to age. For example, upper respiratory tract infections and diarrhea decrease in frequency with age, whereas other disorders, such as acne and headaches, increase. Children who have had a particular type of problem are more likely to have that problem again. Morbidity is not distributed randomly in children. Children from poor families do not fare as well on health indicators as children from nonpoor families (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2007). This finding suggests the need for heightened efforts to improve access to health care for low-income children.

Recent concern has focused on groups of children who have increased morbidity: homeless children, children living in poverty, LBW children, children with chronic illnesses, foreign-born adopted children, and children in daycare centers. A number of factors place these groups at risk for poor health. A major cause is barriers to health care, especially for the homeless, the poverty stricken, and those with chronic health problems. Other factors include improved survival of children with chronic health problems, particularly infants of VLBW.

THE ART OF PEDIATRIC NURSING

Nursing of infants, children, and adolescents is consistent with the definition of nursing as “the diagnosis and treatment of human responses to actual or potential health problems.” This definition incorporates the four essential features of contemporary nursing practice (American Nurses Association, 2003):

1. Attention to the full range of human experiences and responses to health and illness without restriction to a problem-focused orientation

2. Integration of objective data with knowledge gained from an understanding of the patient or group’s subjective experience

3. Application of scientific knowledge to the processes of diagnosis and treatment

4. Provision of a caring relationship that facilitates health and healing

FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

The philosophy of family-centered care recognizes the family as the constant in a child’s life. Service systems and personnel must support, respect, encourage, and enhance the strength and competence of the family by developing a partnership with parents (Newton, 2000). Nurses support families in their natural caregiving and decision-making roles by building on their unique strengths and acknowledging their expertise in caring for their child both within and outside the hospital setting (Newton, 2000). The needs of all family members, not just the child’s, are considered (Box 1-3). The philosophy acknowledges diversity among family structures and backgrounds; family goals, dreams, strategies, and actions; and family support, service, and information needs.

Two basic concepts in family-centered care are enabling and empowerment. Professionals enable families by creating opportunities and means for all family members to display their current abilities and competencies and to acquire new ones to meet the needs of the child and family. Empowerment describes the interaction of professionals with families in such a way that families maintain or acquire a sense of control over their family lives and acknowledge positive changes that result from helping behaviors that foster their own strengths, abilities, and actions.

Although caring for the family is strongly emphasized throughout this text, it is highlighted in features such as Cultural Awareness, Family Focus (see p. 17), and Family-Centered Care boxes.

ATRAUMATIC CARE

Although tremendous advances have been made in pediatric care, much of what is done to children to cure illness and prolong life is traumatic, painful, upsetting, and frightening. Unfortunately, attempts to minimize the trauma of medical interventions have not kept pace with technologic advances. With knowledge of the stressors imposed on ill children and their families and armed with interventions that are safe and effective in eliminating or reducing the stressors, health professionals must direct their attention to providing atraumatic care.

Atraumatic care is the provision of therapeutic care in settings, by personnel, and through the use of interventions that eliminate or minimize the psychologic and physical distress experienced by children and their families in the health care system. Therapeutic care encompasses the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, or palliation of chronic or acute conditions. Setting refers to the place in which that care is given–the home, the hospital, or any other health care setting. Personnel includes anyone directly involved in providing therapeutic care. Interventions range from psychologic approaches, such as preparing children for procedures, to physical interventions, such as providing space for a parent to room in with a child. Psychologic distress may include anxiety, fear, anger, disappointment, sadness, shame, or guilt. Physical distress may range from sleeplessness and immobilization to disturbing sensory stimuli such as pain, temperature extremes, loud noises, bright lights, or darkness. Thus atraumatic care is concerned with the who, what, when, where, why, and how of any procedure performed on a child for the purpose of preventing or minimizing psychologic and physical stress (Wong, 1989).

The overriding goal in providing atraumatic care is: first, do no harm. Three principles provide the framework for achieving this goal: (1) prevent or minimize the child’s separation from the family, (2) promote a sense of control, and (3) prevent or minimize bodily injury and pain. Examples of providing atraumatic care include fostering the parent-child relationship during hospitalization, preparing the child before any unfamiliar treatment or procedure, controlling pain, allowing the child privacy, providing play activities for expression of fear and aggression, providing choices to children, and respecting cultural differences.

ROLE OF THE PEDIATRIC NURSE

Pediatric nurses are involved in every aspect of a child’s and family’s growth and development. Nursing functions vary according to regional job structures, individual education and experience, and personal career goals. Just as patients (children and their families) have unique backgrounds, each nurse brings an individual set of variables that affects the nurse-patient relationship. No matter where pediatric nurses practice, their primary concern is the welfare of the child and family.

THERAPEUTIC RELATIONSHIP

The establishment of a therapeutic relationship is the essential foundation for providing high-quality nursing care. Pediatric nurses need to have meaningful relationships with children and their families and yet remain separate enough to distinguish their own feelings and needs. In a therapeutic relationship, caring, well-defined boundaries separate the nurse from the child and family. These boundaries are positive and professional and promote the family’s control over the child’s health care. Effective family advocacy demands that these boundaries be established and promote therapeutic relationships (Jacobson, 2002). Both the nurse and the family are empowered, and open communication is maintained. In a nontherapeutic relationship these boundaries are blurred, and many of the nurse’s actions may serve personal needs, such as a need to feel wanted and involved, rather than the family’s needs.

Exploring whether relationships with patients are therapeutic or nontherapeutic helps nurses identify problem areas early in their interactions with children and families (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Although questions for exploring types of involvement label certain actions negative or positive, no one action makes a relationship therapeutic or nontherapeutic. For example, a nurse may spend additional time with the family but still recognize his or her own needs and maintain professional separateness. An important clue to nontherapeutic relationships is the staff’s concerns about their peer’s actions with the family.

FAMILY ADVOCACY AND CARING

Although nurses are responsible to themselves, the profession, and the institution of employment, their primary responsibility is to the consumer of nursing services–the child and family. The nurse must work with family members, identify their goals and needs, and plan interventions that best address the defined problems. As an advocate, the nurse assists the child and family in making informed choices and acting in the child’s best interest. Advocacy involves ensuring that families are aware of all available health services, informed adequately of treatments and procedures, involved in the child’s care, and encouraged to change or support existing health care practices. The United Nations’ Declaration of the Rights of the Child (Box 1-4) provides guidelines for nursing practice to ensure that every child receives optimum care. The nurse uses this knowledge to adapt care for the child’s optimum physical and emotional well-being.

As nurses care for children and families, they must demonstrate caring, compassion, and empathy for others. Aspects of caring embody the concept of atraumatic care and the development of a therapeutic relationship with patients. Parents perceive caring as a sign of quality in nursing care, which is often focused on the nontechnical needs of the child and family. Parents describe “personable” care as actions by the nurse that include acknowledging the parent’s presence, listening, making the parent feel comfortable in the hospital environment, involving the parent and child in the nursing care, showing interest in and concern for their welfare, showing affection and sensitivity to the parent and child, communicating with them, and individualizing the nursing care. Parents perceive personable nursing care as being integral to establishing a positive relationship.

DISEASE PREVENTION AND HEALTH PROMOTION

Every nurse involved with child care must practice preventive health care. Regardless of the identified problem, the nurse’s role is to plan care that fosters every aspect of growth and development. Based on a thorough assessment process, problems related to nutrition, immunizations, safety, dental care, development, socialization, discipline, or schooling often become obvious. Once the problem is identified, the nurse acts to intervene directly or to refer the family to other health care providers or agencies.

The best approach to prevention is education and anticipatory guidance. In this text each chapter on health promotion includes sections on anticipatory guidance. An appreciation of the hazards or conflicts of each developmental period enables the nurse to guide parents regarding childrearing practices aimed at preventing potential problems. One of the most significant examples is safety. Because each age-group is at risk for special types of injuries, preventive teaching can significantly reduce injuries, lowering permanent disability and mortality rates.

Prevention also involves less obvious aspects of child care. Besides preventing physical disease or injury, the nurse also promotes mental health. For example, it is not sufficient to administer immunizations without regard to the psychologic trauma associated with the procedure. Optimum health care involves providing care with a humane approach; the nurse and all other health care professionals must ensure that humane care is provided.

HEALTH TEACHING

Health teaching is inseparable from family advocacy and prevention. Health teaching may be a direct goal of the nurse, such as during parenting classes, or may be indirect, such as helping parents and children understand a diagnosis or medical treatment, encouraging children to ask questions about their bodies, referring families to health-related professional or lay groups, supplying patients with appropriate literature, and providing anticipatory guidance.

Health teaching is one area in which nurses often need preparation and practice with competent role models, since it involves transmitting information at the child’s and family’s level of understanding and desire for information. As an effective educator, the nurse focuses on providing the appropriate health teaching with generous feedback and evaluation to promote learning.

SUPPORT AND COUNSELING

Attention to emotional needs requires support and, sometimes, counseling. The role of child advocate or health teacher is supportive by virtue of the individualized approach. The nurse can offer support by listening, touching, and being physically present. Touching and physical presence are most helpful with children because they facilitate nonverbal communication.

Counseling involves a mutual exchange of ideas and opinions that provides the basis for mutual problem solving. It involves support, teaching, techniques to foster the expression of feelings or thoughts, and approaches to help the family cope with stress. Optimally, counseling not only helps resolve a crisis or problem but also enables the family to attain a higher level of functioning, greater self-esteem, and closer relationships. Although counseling is often the role of nurses in specialized areas, counseling techniques are discussed in various sections of this text to help students and nurses cope with immediate crises and refer families for additional professional assistance.

COORDINATION AND COLLABORATION

The nurse, as a member of the health care team, collaborates and coordinates nursing services with the activities of other professionals. Working in isolation does not serve the child’s best interests. The concept of holistic care can be realized only through a unified, interdisciplinary approach. Being aware of individual contributions and limitations to the child’s care, the nurse must collaborate with other specialists to provide high-quality health services. Failure to recognize limitations can be nontherapeutic at best and destructive at worst. For example, the nurse who feels competent in counseling but who is really inadequate in this area may not only prevent the child from dealing with a crisis but may also impede future success with a qualified professional.

Even nurses who practice in isolated geographic areas widely separated from other health professionals cannot be considered independent. Every nurse works interdependently with the child and family, collaborating on assessing needs and planning interventions so that the final care plan is one that truly meets the child’s needs. Unfortunately, this aspect of collaboration and coordination frequently is lacking in health care planning. Numerous disciplines often work together to formulate a comprehensive approach without consulting patients regarding their ideas or preferences. The nurse is in a vital position to include patients in their care, either directly or indirectly, by communicating their thoughts to the health care team.

ETHICAL DECISION MAKING

Ethical dilemmas arise when competing moral considerations underlie various alternatives. Parents, nurses, physicians, and other health care team members may reach different but morally defensible decisions by assigning different weights to competing moral values. These competing moral values may include autonomy, the patient’s right to be self-governing; nonmaleficence, the obligation to minimize or prevent harm; beneficence, the obligation to promote the patient’s well-being; and justice, the concept of fairness. Nurses must determine the most beneficial or least harmful action within the framework of societal mores, professional practice standards, the law, institutional rules, the family’s value system and religious traditions, and the nurse’s personal values. Nurses are important role models for demonstrating how to create an environment of mutual respect and understanding for patients and their families. Respect for the individuals they care for is the affirmation that other persons matter in the same way as the nurses themselves (Milton, 2005).

Nurses must prepare themselves systematically for collaborative ethical decision making. This can be accomplished through formal course work, continuing education, contemporary literature, and work to establish an environment conducive to ethical discourse. Moreover, nurses must be educated on the mechanisms for dispute resolution, case review by ethics committees, procedural safeguards, state statutes, and case law (Woods, 2005).

The nurse also uses the professional code of ethics for guidance and as a means for professional self-regulation. The Code of Ethics for Nurses by the American Nurses Association focuses on the nurse’s accountability and responsibility to the patient and emphasizes the nursing role as an independent professional, one that upholds its own legal liability (Box 1-5).

Nurses may face ethical issues regarding patient care, such as the use of lifesaving measures for VLBW newborns or the terminally ill child’s right to refuse treatment. They may struggle with questions regarding truthfulness, balancing their rights and responsibilities in caring for children with AIDS, whistle-blowing, or allocating resources. Throughout the text such dilemmas are addressed in boxes titled Ethical Case Studies. Conflicting ethical arguments are presented to help nurses clarify their value judgments when confronted with sensitive issues.

RESEARCH

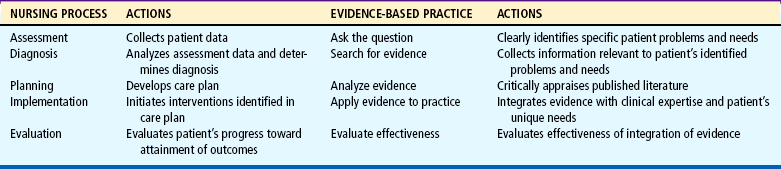

Practicing nurses should contribute to research because they are the individuals observing human responses to health and illness. The current emphasis on measurable outcomes to determine the efficacy of interventions (often in relation to the cost) demands that nurses know whether clinical interventions result in positive outcomes for their patients. This demand has influenced the current trend toward evidence-based practice (EBP), which implies questioning why something is effective and whether a better approach exists. The concept of EBP also involves analyzing and translating published clinical research into the everyday practice of nursing. When nurses base their clinical practice on science and research and document their clinical outcomes, they will be able to validate their contributions to health, wellness, and cure, not only to their patients, third-party payers, and institutions but also to the nursing profession. Evaluation is essential to the nursing process, and research is one of the best ways to accomplish this.

CRITICAL THINKING AND THE PROCESS OF NURSING CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

A systematic thought process is essential to a profession. It assists the professional in meeting the patient’s needs. Critical thinking is purposeful, goal-directed thinking that assists individuals in making judgments based on evidence rather than guesswork (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2005). It is based on the scientific method of inquiry, which is also the roots of the nursing process. Critical thinking and the nursing process are considered crucial to professional nursing in that they constitute a holistic approach to problem solving.

Critical thinking is a complex developmental process based on rational and deliberate thought. Becoming a critical thinker provides a common denominator for knowledge that exemplifies disciplined and self-directed thinking. The knowledge is acquired, assessed, and organized by thinking through the clinical situation and developing an outcome focused on optimum patient care. The cognitive skills used in high-quality thinking include intellectual discipline, self-evaluation, creativity, persistence, risk taking, and intuition (Ignatavicius, 2001). Critical thinking transforms the way in which individuals view themselves, understand the world, and make decisions. In recognition of the importance of this skill, Critical Thinking Exercises are included in this text. These exercises present a nursing practice situation that challenges the student to use the skills of critical thinking to come to the best conclusion. The student is led by a series of questions that explore the evidence, assumptions underlying the problem, nursing priorities, and support for nursing interventions that allow the nurse make a rational and deliberate response based on self-directed thinking. The benefit of these thinking exercises is that they may enhance nursing performance in clinical judgment.

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EBP is the collection, interpretation, and integration of valid, important, and applicable patient-reported, nurse-observed, and research-derived information (Simpson, 2004). Evidence-based nursing practice combines knowledge with clinical experience and intuition. It provides a rational approach to decision making that facilitates best practice (Newhouse, Dearholt, Poe, and others, 2005). EBP is an important tool that complements the nursing process by using critical thinking skills to make decisions based on existing knowledge. The traditional nursing process approach to patient care can be used to conceptualize the essential components of EBP nursing (Table 1-5). During the assessment and diagnostic phases of the nursing process, the nurse establishes important clinical questions and completes a critical review of existing knowledge. EBP also begins with identification of the problem. The nurse asks clinical questions in a concise, organized way that allows for clear answers. Once the specific questions are identified, extensive searching for the best information to answer the question begins. The nurse evaluates clinically relevant research, analyzes findings from the history and physical examinations, and reviews the specific pathophysiology of the defined problem. The third step in the nursing process is to develop a care plan. In evidence-based nursing practice, the care plan is established on completion of a critical appraisal of what is known and not known about the defined problem. Next, in the traditional nursing process, the nurse implements the care plan. By integrating evidence with clinical expertise, the nurse focuses care on the patient’s unique needs. A template for organizing the evidence is found in Box 1-6. The final step in EBP is consistent with the final phase of the nursing process: to evaluate the effectiveness of the care plan.

Searching for evidence in this modern era of technology can be overwhelming. Appropriate resources must be available for nurses to implement EBP. Resources include online search engines and journal access to the most recent information. In many institutions computer terminals are available on patient care units, with the Internet and online journals easily accessible. Another important resource for the implementation of EBP is time. The nursing shortage and ongoing changes that many institutions face have compounded the issue of nursing time allocation for patient care, education, and training. In some institutions nurses are given paid time away from performing patient care to participate in activities that promote EBP. This requires an organizational environment that values EBP and its potential impact on patient care. As knowledge is generated regarding the significant impact of EBP on patient care outcomes, it is hoped that the organizational culture will change to support the staff nurse’s participation in EBP. As the amount of available evidence increases, so does our need to critically evaluate the evidence.

NURSING PROCESS

The nursing process is a method of problem identification and problem solving that describes what the nurse actually does (Alfaro-LeFevre, 2005). The five-step model that is accepted as the nursing process is assessment, diagnosis (problem identification), planning (with outcome development), implementation, and evaluation. The second step of the nursing process, nursing diagnosis, is the naming of the child’s or family’s problem in standardized nursing language. In the American Nurses Association (2003) Standards of Practice, the nursing diagnosis phase of the nursing process is separated into two steps: nursing diagnosis and outcome identification. Throughout this text Nursing Process boxes provide organization for the nursing care, following the template in Box 1-7.

Assessment

Assessment is a continuous process that operates at all phases of problem solving and is the foundation for decision making. Assessment involves multiple nursing skills and consists of the purposeful collection, classification, and analysis of data from a variety of sources. To provide an accurate and comprehensive assessment, the nurse must consider information about the patient’s biophysical, psychologic, sociocultural, and spiritual background.

Nursing Diagnosis

The second stage of the nursing process is problem identification and nursing diagnosis. At this point the nurse must interpret and make decisions about the data gathered. The nurse organizes or clusters these data into categories to identify significant areas and makes one of the following decisions:

No dysfunctional health problems are evident; no interventions are indicated.

No dysfunctional health problems are evident; no interventions are indicated.

Risk for dysfunctional health problems exists; interventions are needed to facilitate health promotion.

Risk for dysfunctional health problems exists; interventions are needed to facilitate health promotion.

Actual dysfunctional health problems are evident; interventions are needed to facilitate health promotion.

Actual dysfunctional health problems are evident; interventions are needed to facilitate health promotion.

The nursing diagnosis is the naming of the cue clusters that are obtained during the assessment phase. According to NANDA International (formerly the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association), the currently accepted definition of the term nursing diagnosis is that it is a clinical judgment about individual, family, or community responses to actual and potential health problems and life processes. Box 1-8 reviews the classification systems for nursing diagnoses. Nursing diagnoses provide the basis for selecting nursing interventions to achieve outcomes for which the nurse is accountable (Johnson, Bulechek, Dochterman, and others, 2001). The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) consists of a standardized list of more than 400 examples of care provided by nurses in clinical practice. The Nursing Outcomes Classification (NOC) is a comprehensive, standardized system of patient outcomes that can be used to evaluate the results of specific nursing interventions. Examples of NIC and NOC concepts are listed in each Nursing Care Plan (NCP) in this text to provide an understanding of the standardized language and its interrelatedness within the individualized NCP.

Not all children have actual health problems; some have a potential health problem, which is a risk state that requires nursing intervention to prevent the development of an actual problem. Potential health problems may be indicated by the presence of risk factors, or signs, that predispose a child and family to a dysfunctional health pattern and are limited to individuals at greater risk than the population as a whole. Nursing intervention is directed toward reducing risk factors. To differentiate actual from potential health problems, the word risk is included in the nursing diagnosis statement (e.g., Risk for Infection).

Signs and symptoms refer to a cluster of cues and defining characteristics that are derived from patient assessment and indicate actual health problems. When a defining characteristic is essential for the diagnosis to be made, it is considered critical. These critical defining characteristics help differentiate between diagnostic categories. For example, in deciding between the diagnostic categories related to family function and coping, the defining characteristics are critical in choosing the most appropriate nursing diagnosis (see Family Focus box).

Planning

Once the nursing diagnoses have been identified, the nurse develops a care plan and establishes outcomes or goals. The outcome is the projected or expected change in a patient’s health status, clinical condition, or behavior that occurs after nursing interventions have been instituted. The ultimate goal of nursing care is to convert the nursing diagnoses into a desired health state. The care plan must be established before specific nursing interventions are developed and implemented.

Implementation

The implementation phase begins when the nurse puts the selected intervention into action and accumulates feedback data regarding its effects (or the patient’s response to the intervention). The feedback returns in the form of observation and communication and provides a database on which to evaluate the outcome of the nursing intervention. It is imperative that continuous assessment of the patient’s status occur throughout all phases of the nursing process, thus making the process a dynamic rather than static problem-solving method. Throughout the implementation stage, the patient’s physical safety and psychologic comfort in terms of atraumatic care are the main concerns.

Evaluation

Evaluation is the last step in the decision-making process. The nurse gathers, sorts, and analyzes data to determine whether (1) the established outcome has been met, (2) the nursing interventions were appropriate, (3) the plan requires modification, or (4) other alternatives should be considered. The evaluation phase either completes the nursing process (outcome is met) or serves as the basis for the selection of other alternatives for intervention in solving the specific problem.

Documentation

Although documentation is not one of the five steps of the nursing process, it is essential for evaluation. The nurse can assess, diagnose and identify problems, plan, and implement without documentation; however, evaluation is best performed with written evidence of progress toward outcomes. The patient’s medical record should include evidence of those elements listed in the Nursing Care Guidelines box.

Currently attention in health care is also focused on patient outcomes. The patient’s care is evaluated not only at discharge but thereafter as well to ensure that the outcomes are met and there is adequate care for assisting the patient in resolving existing or potential health problems.

One federal agency that has developed clinical guidelines is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.*

REFERENCES

Alfaro-LeFevre, R. Applying nursing process: a tool for critical thinking, ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2005.

American Academy of Pediatrics. The National Children’s Study. http://www.aap.org/family/natlchstudy.htm. [retrieved Dec 1, 2004, from].

American Association of Suicidology. About AAS. http://www.suicidology.org. [retrieved Feb 2, 2007, from].

American Nurses Association. Nursing: scope and standards of practice. Washington, DC: The Association, 2003.

Coury, DL. Over the rainbow: advancing child health in the new millennium. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(3):134–137.

Covington, CY, Cybulski, MJ, Davis, TL, et al. Kids on the move: preventing obesity among urban children. Am J Nurs. 2001;101(3):73–77. [79, 81-82,].

Dietz, WH. Overweight: an epidemic. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Doucette, A. Youth suicide. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Dougherty, D, Meikle, SF, Owens, P, et al. Children’s health care in the First National Healthcare Quality Report and National Healthcare Disparities Report. Med Care. 2005;43(3 Suppl):I58–I63.

Duderstadt, KG. Advocacy for reducing childhood obesity. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18:103–105.

Edelstein, BL. Tooth decay: the best of times, the worst of times. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. America’s children: key national indicators of well-being. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2007.

Fisher, K, Kettl, P. Teachers’ perceptions of school violence. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17:79–83.

Fitzgibbon, ML, Stolley, MR. Environmental changes may be needed for prevention of overweight in minority children. Pediatr Ann. 2004;33:45–49.

Groves, BM. Violence in the lives of children. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Heron, M. Deaths: leading causes for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56(5):1–96.

Heuer, S. Family-centered care. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2007;12(1):61–65.

Hoyert, DL, Heron, M, Murphy, SL, et al Deaths: final data for 2003. National Center for Health Statistics, 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/finaldeaths03/finaldeaths03.htm [retrieved Jan 20, 2006, from].

Ignatavicius, D. Critical thinking skills for at the bedside success. Nurs Manage. 2001;32(1):37–39.

Jackson, PL. Healthy people 2010: the pediatric nursing challenge for the next decade. Pediatr Nurs. 2001;27:498–502.

Jacobson, GA. Maintaining professional boundaries: preparing nursing students for the challenge. J Nurs Educ. 2002;41(6):279–281.

Johnson, M, Bulechek, G, Dochterman, J, et al. Nursing diagnosis, outcomes and interventions. St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

Kelleher, K. Mental health. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Lichter, DT. Families: diversity and change. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Martin, JA, Kochanek, KD, Strobino, DM, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2003. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):619–634.

Martin, JA, Kung, HC, Mathews, TJ, et al. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2006. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):788–801.

Medd, SE. Children with ADHD need our advocacy. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17:102–104.

Milton, CL. The ethics of respect in nursing. Nurs Sci Q. 2005;18(1):20–23.

National Center for Health Statistics. About Healthy People 2010. from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/otheract/hpdata2010/abouthp.htm. [retrieved Feb 2, 2007,].

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Injury fact book 2001-2002. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001.

National Safety Council. Injury facts. Itaska, Ill: The Council, 2000.

Newhouse, R, Dearholt, S, Poe, S, et al. Evidence-based practice: a practical approach to implementation. JONA. 2005;35(1):35–40.

Newton, MS. Family-centered care: current realities in parent participation. Pediatr Nurs. 2000;26(2):164–168.

Rivara, FP. Impact of injury. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Robinson, TN, Sargent, JD. Children and media. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Schnitzer, PG. Prevention of unintentional childhood injuries. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(11):1864–1869.

Simpson, R. Evidence-based nursing offers certainty in the uncertain world of healthcare. Nurs Manage. 2004;35(10):10–12.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. 2003 National survey on drug use and health: results. http://www.drugabusestatistics.samhsa.gov/NHSDA/2k3NSDUH/2k3results.htm, 2004. [retrieved Feb 2, 2007, from].

US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010. http://www.healthypeople.gov/default.htm, 2007. [retrieved Jan 8, 2008, from].

Wise, PH. Medical progress and inequalities in child health. In: Cosby AG, Greenberg RE, Southward LH, et al, eds. About children: an authoritative resource on the state of childhood today. Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005.

Wise, PH. The transformation of child health in the United States. Health Affairs. 2004;23(5):9–25.

Wong, D. Principles of atraumatic care. In: Feeg V, ed. Pediatric nursing: forum on the future: looking toward the 21st century. Pitman, NJ: Anthony J Jannetti, 1989.

Woods, M. Nursing ethics education: are we really delivering the good(s)? Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(1):5–18.

World Health Organization. School health and youth health promotion. http://www.who.int/school_youth_health/en, 2007. [retrieved Jan 26, 2007, from].

Yensel, CS, Preud—Homme, D, Curry, DM. Childhood obesity and insulin-resistant syndrome. J Pediatr Nurs. 2004;19:238–246.

*540 Gaither Road, Suite 2000, Rockville, MD 20850; (301) 427-1364; info@ahrq.gov; http://www.ahrq.gov.

IN TEXT

IN TEXT

COMMUNITY FOCUS

COMMUNITY FOCUS

FAMILY FOCUS

FAMILY FOCUS