Health Problems of School-Age Children and Adolescents

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

Outline a care plan for the child or adolescent with a health problem.

Outline a care plan for the child or adolescent with a health problem.

Demonstrate an understanding of the types, causes, and prevention of sports injuries in middle childhood and adolescence.

Demonstrate an understanding of the types, causes, and prevention of sports injuries in middle childhood and adolescence.

Describe the most common causes of physical growth or maturation failure in later childhood.

Describe the most common causes of physical growth or maturation failure in later childhood.

Demonstrate an understanding of common disorders of the male and female reproductive systems.

Demonstrate an understanding of common disorders of the male and female reproductive systems.

Demonstrate an understanding of health problems related to adolescent sexuality.

Demonstrate an understanding of health problems related to adolescent sexuality.

Outline a plan for discussing sexuality issues with adolescents.

Outline a plan for discussing sexuality issues with adolescents.

Outline a care plan for the child or adolescent with an eating disorder.

Outline a care plan for the child or adolescent with an eating disorder.

Discuss the manifestations and nursing management of selected emotional or behavioral problems.

Discuss the manifestations and nursing management of selected emotional or behavioral problems.

PROBLEMS RELATED TO ELIMINATION

Enuresis (bed-wetting), or nocturnal enuresis, is a common and troublesome disorder that is defined as intentional or involuntary passage of urine into bed (usually at night) in children who are beyond the age when voluntary bladder control should normally have been acquired. The inappropriate voiding of urine must occur at least twice a week for at least 3 months, and the chronologic or developmental age of the child must be at least 5 years. The predominant symptom is urgency that is immediate and accompanied by acute discomfort, restlessness, and urinary frequency. Enuresis is more common in boys; nocturnal bed-wetting usually ceases between 6 and 8 years of age. Enuresis can also be defined as primary (bed-wetting in children who have never been dry for extended periods) or secondary (the onset of wetting after a period of established urinary continence). The passage of urine may occur only during nighttime sleep with the child remaining dry during the day (monosymptomatic); or it may be polysymptomatic, wherein the child has daytime urinary urgency, an occasional daytime accident, in conjunction with other conditions such as sleep apnea, urinary tract infection, neurologic impairment, constipation, or emotional stressors (Berry, 2006). The nocturnal, monosymptomatic type is most common. The condition may be particularly distressing to adolescents, who may refuse therapy. Although enuresis may occur during the daytime, the following discussion primarily focuses on nocturnal enuresis.

Before psychogenic factors are considered, organic causes that may be related to enuresis should be ruled out. These include structural disorders of the urinary tract; urinary tract infection; neurologic deficits; disorders that increase the normal output of urine, such as diabetes; and disorders that impair the concentrating ability of the kidneys, such as chronic renal failure or sickle cell disease. A bladder volume of 300 to 350 ml (10 to 12 ounces) is sufficient to hold a night’s urine. Normal bladder capacity (in ounces) is the child’s age plus 2. In other cases the enuresis is influenced by emotional factors, although it is doubtful that they are causative factors. Parents report that these children sleep more soundly than other children; however, the depth of sleep has not been identified as the cause of nocturnal enuresis (Berry, 2006). Nocturnal enuresis has a strong familial tendency.

Therapeutic techniques used to manage nocturnal enuresis include medications, bladder training, restriction or elimination of fluids after the evening meal, interruption of sleep to void, and various devices designed to establish a conditioned reflex response to waken the child at the initiation of voiding (alarms).

Three types of drugs are used to treat enuresis: tricyclic antidepressants, antidiuretics, and anticholinergics. A drug used frequently to inhibit urination is the tricyclic antidepressant imipramine. Another anticholinergic drug, oxybutynin, reduces uninhibited bladder contractions and may be helpful for children with daytime urinary frequency. Desmopressin (DDAVP) nasal spray, an analog of vasopressin, reduces nighttime urinary output to a volume less than functional bladder capacity. Drugs are usually considered second-line management, and parents should be cautioned not to think that these agents will cure the condition; parents are also advised of the drug’s side effects (Sethi, Bhargava, and Shipra, 2005).

Nursing Care Management

Regardless of the techniques used, the nurse can help both children and parents understand the problem of enuresis, the treatment plan, and the difficulties they may encounter in the process. The nurse can also provide consistent support and encouragement to help sustain both the child and the parents through the inconsistent and unpredictable treatment process. Parents need to understand that punishment is contraindicated because of its negative emotional impact and limited success in reducing the behavior. Positive reinforcement of the desired behavior may be beneficial (Sethi, Bhargava, and Shipra, 2005). Children need to believe that they are helping themselves, and they need to sustain feelings of confidence and hope.

Parents should also be taught to observe for side effects of any medications used. All children with primary enuresis should be encouraged to void before bedtime. Diapering should be avoided. Positive reinforcement in the form of keeping diaries to record dry nights has been effective in motivating children.

ENCOPRESIS

Encopresis is the repeated voluntary or involuntary passage of feces of normal or near-normal consistency in places not appropriate for that purpose according to the individual’s own sociocultural setting. The event must occur at least once per month for at least 3 months, and the chronologic or developmental age of the child must be at least 4 years. The fecal incontinence must not be caused by any physiologic effect, such as a laxative, or a general medical condition.

Primary encopresis is identified by age 4 when the child has not achieved fecal continence. Secondary encopresis is fecal incontinence occurring in a child older than 4 years of age after a period of established fecal continence. The disorder is more common in boys than in girls.

One of the most common causes of encopresis is constipation, which may be precipitated by environmental change. Chronic, severe constipation has a tendency to impair the usual movement and contractions of the colon, which can lead to fecal obstruction. Abnormalities in the digestive tract (e.g., Hirschsprung disease, anorectal lesions, malformations, and rectal prolapse) and medical conditions such as hypothyroidism, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, lead intoxication, myelomeningocele, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, and irritable bowel syndrome are also associated with constipation, which can lead to encopresis (Coughlin, 2003). Children with encopresis often feel ashamed and may wish to avoid situations that might lead to embarrassment. School performance and attendance are affected as the child’s offensive odor becomes a target for scorn and ridicule from classmates.

Therapeutic management consists of determining the cause of the soiling and using appropriate interventions to correct the problem. Diet, lubricants, and a toilet ritual that encourages the child to establish normal defecation are used. Fecal impaction is relieved by lubricants such as mineral oil; osmotic laxatives such as lactulose, sorbitol, or polyethylene glycol (PEG or MiraLAX); and magnesium hydroxide. Customary dosages are usually insufficient. Mineral oil should be avoided in children who have dysphagia or vomiting to prevent risk of aspiration. Dietary changes may be helpful, including elimination of milk and dairy products; consumption of increased amounts of high-fiber foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and cereals; and increased fluids. Behavioral therapy may be indicated to eliminate any fear that has developed as a result of painful defecation. Frequently, psychotherapeutic intervention with the child and the family becomes necessary.

Nursing Care Management

The nursing care of the child with encopresis involves education and support of the family and treatment of existing constipation. Education regarding the physiology of normal defecation, toilet training as a developmental process, and the treatment outlined for the particular family is essential to a successful outcome. Family counseling is directed toward reassurance that most problems resolve successfully, although relapses during periods of stress are possible (see Family Focus box).

HEALTH PROBLEMS RELATED TO SPORTS PARTICIPATION

Every sport has the potential for injury to the participant—whether the adolescent engages in serious competition or participates for enjoyment. Serious injury occurs most often during rough contact sports or to persons who are not physically prepared for the activity. Injuries also occur when the children’s or adolescents’ bodies are not suited to the sport, when their muscles and body systems (respiratory and cardiovascular) are not conditioned to endure physical stress, or when they lack the insight and judgment to recognize that an activity exceeds their physical abilities. Rapidly growing bones, muscles, joints, and tendons are especially vulnerable to unusual strain. More injuries occur during recreational sports participation than during organized athletic competition.

The environment and the sports or recreational equipment can also present risks (Fig. 17-1). Children who participate in physical activity or sports do so in many different environments: indoors and outdoors, on floors, on the ground and snow, on or beneath water surfaces, and sometimes in free air space. Most of these activities also involve equipment, which children and adolescents may not be physically mature enough to manage safely. A common example of this would include skateboarding when the child or adolescent does not take safety precautions and perceives increased risk-taking as a part of the sport.

Acute overload injuries are those that occur suddenly during an activity and produce immediate symptoms. A blow or overstretching, twisting, or sudden stress to tissues can cause these injuries. For descriptions and management of traumatic injuries see Chapter 31.

OVERUSE SYNDROMES

To excel in sports, the young athlete is forced to train longer, harder, and earlier in life than previously. The rewards are an increased level of fitness, better performance, faster times, and the satisfaction of attaining a personal goal. With the increase in the number of children participating in sports year-round, more overuse injuries are being seen in the pediatric age-group (Lord and Winell, 2004).

The risk of overuse injury is always present and can be related to several factors: training errors, muscle-tendon imbalance, anatomic malalignment (e.g., femoral anteversion, excessive lumbar lordosis, tibial torsion), incorrect footwear or playing surface, an associated disease state, and growth (growth cartilage is less resistant to microtrauma). Athletes who run extensively frequently experience shin splints. The ligaments tear away from the tibial shaft, and this creates the pain. Ice, rest, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen or naproxen, are the usual treatment. Shin splints are rarely serious.

Chronic pain in athletes is often associated with overuse injury, which can occur at any level of athletic participation. The common feature in overuse injuries is the repetitive microtrauma that occurs to a particular anatomic structure (Lord and Winell, 2004). Performing the same movements time and time again can cause several types of injury:

Frictional, or rubbing of one structure against another

Frictional, or rubbing of one structure against another

Tractional, or repeated pull on a ligament or tendon

Tractional, or repeated pull on a ligament or tendon

Cyclic, or repetitive loading of impact forces (stress fractures)

Cyclic, or repetitive loading of impact forces (stress fractures)

The end result is inflammation of the involved structure with complaints of pain, tenderness, swelling, and disability.

Bursae, tendons, muscles, ligaments, joints, and bones are all subject to overuse. Plantar fasciitis is common in athletes, and Osgood-Schlatter disease is seen in children who do a lot of jumping. The occurrence of overuse-type injuries, such as sore shoulders and strained elbows, may indicate that too much is being requested of the child in too short a period.

Stress Fractures

Given the intensity and duration of sports training, many young athletes suffer stress fractures, especially after a recent increase in training regimens. These fractures occur as a result of repeated muscle contraction and are seen most often in sports involving repetitive weight bearing such as running, gymnastics, and basketball. They occur less often in swimming (in the upper extremities). Tibial fractures are most common.

The most common symptom of stress fracture is a sharp, persistent, progressive pain or a deep, persistent dull ache located over the bone. Sometimes there is pain on impact (heel strike), but the most important clinical sign is pain over the involved bony surface. Diagnosis is based on clinical observation. Plain radiographs are rarely diagnostic of stress fractures during the initial few weeks, since callus formation is not yet evident. Occasionally a bone scan may be needed and will indicate a “hot spot.”

Therapeutic Management

Development of inflammation is common to all overuse syndromes; therefore management involves rest or alteration of activities, physical therapy, and medication. Rest is the primary therapy, usually interpreted as reduced activity and the use of alternative exercise—not bed rest or immobilization with casting. The main purpose is to alleviate the repetitive stress that initiated the symptoms. It is important to keep the child or adolescent mobile, and training can be continued. Alternative exercise is selected that maintains conditioning without aggravating the injury. For example, pool running (treading water in the deep end of a pool) can use the same movements as running but without the weight bearing; bicycling, swimming, and rowing are viable alternatives.

Other modalities include cryotherapy and cold whirlpool baths. Sometimes taping, bracing, splinting, and other orthoses are employed, depending on the injury. NSAIDs are often prescribed to reduce inflammation and pain. Topical medications are of questionable value.

NURSE’S ROLE IN SPORTS FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Nurses are often involved in sports activities in the areas of preparation and evaluation for activities, prevention of injury, treatment of injuries, and rehabilitation after injury. Selecting an appropriate sport for both recreation and competition is a joint effort of the adolescent, parents, and health professionals. The best approach to counseling children, adolescents, and parents regarding sports participation is to encourage activities that are most likely to provide pleasure and physical benefits throughout childhood and into adulthood. Exposure to a variety of activities is better for young children than limiting them to one sport. Parents should be cautioned against overcommitting children to sports activities so they have time for other activities.

When children sustain athletic injuries, nurses are often responsible for instructions regarding care. Instructions (e.g., schedule for appointments, application of ice, any restrictions in activity) should be clear and accompanied by written directions. The importance of taking medications as prescribed is emphasized, especially if medications are needed for an extended period and if adherence is an issue. Medications given an hour before practice or competition may help children continue their activities.

Prevention of sports injuries is the most important aspect of athletic programs. Children should be suited to the activity; the environment and the equipment must be safe. Children should be prepared for the sport, especially if it requires strenuous or continuous physical exertion. Nurses, coaches, and athletic trainers must collaborate to ensure that safety measures are implemented. Stretching exercises, warm-up and cool-down activities, and appropriate training are requirements for safe participation. Protective measures such as pads, taping, and wrapping are also important to prevent injury. Finally, nurses must be aware of environmental safety risks.

ALTERED GROWTH AND MATURATION

The absence of physical or sexual maturation at a time when other children are experiencing positive evidence of sexual development and its associated spurt in growth and physical strength is an important concern to both the parents and their affected child. In most instances the delay in development is a simple physiologic or constitutional delay that represents one end of the normal genetically influenced variation of pubertal growth. These adolescents will go through a delayed but normal puberty and finally catch up, in their late teens, with their more rapidly developing age-mates. Growth delay may be proportionate or disproportionate; either require careful evaluation by a multidisciplinary team. Less benign causes of delayed development may be endocrine disorders such as growth hormone deficiency, a disease process such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or chronic malabsorption, or a chromosomal abnormality such as Turner syndrome. Additional causes of delayed development include asthma, cystic fibrosis, malabsorption syndromes, cardiac anomalies, and chronic renal conditions. Skeletal disorders that affect growth in stature are those described as dwarfism. Most disorders are caused by congenital defects, such as achondroplasia, and by inborn errors of metabolism such as Hurler syndrome or Hunter syndrome.

The rate of maturation is important during the school years, but at puberty it assumes significant proportions to both teens and their parents. Girls or boys who lag behind their peers in physical maturation are painfully aware of their difference in growth. Adolescent girls with delayed maturation may feel out of place among companions whose hips and breasts are developing, feel cheated if they have not yet menstruated, and feel left out when their friends giggle and talk about boys. Adolescent boys with delayed maturation may feel inferior and small compared with their more muscular companions with whom they can no longer compete physically. Serial measurements of height and weight, as well as other anthropometric data, are obtained and plotted on standard growth charts to determine the pattern of growth and to compare the individual child with the norms for his or her age-group (Appendix B). When children are in the extremes of height ranges, it is important to compare their height with that of their parents and siblings.

Psychosocial, or deprivation, dwarfism is a stress-induced growth failure. It is defined as growth restriction in children older than 2 years of age that is caused by environmental (emotional) stress and is associated with a marked delay in physical growth, delayed developmental skills, and immature behavior. When these children are removed from the deprived environment, their growth proceeds at a normal or increased rate.

Management of growth delay in childhood and adolescence includes continued medical observation, attention to general health and nutrition, and psychologic support. Growth hormone is often recommended to treat growth hormone deficiency (see Hypopituitarism, Chapter 29).

Nursing Care Management

Deviation from the normal course of puberty is a significant concern for affected adolescents. For some adolescents, this concern assumes monumental proportions. Many cases of delayed development are caused by simple constitutional delay of puberty, and the child can be assured that normal development will eventually take place.

One difficulty related to a size that is incongruent with chronologic and mental age is the manner in which others relate to the child. People often respond to children with short stature as though they were younger than their age. Consequently, these children may react with babyish or juvenile behavior, thus establishing a circular pattern of behavior and response. Conversely, children who are tall or physically advanced for their age are frequently treated as though they were more advanced than their years. They are often considered clumsy, cognitively delayed, or immature when they perform according to the normal behavioral expectations for their age.

Listening to distressed adolescents and conveying interest and concern are important interventions. Slowly maturing adolescents need support and reassurance that they are unique individuals who have an important contribution to society that is equally as important as that of their peers. Counseling and therapy are individualized for each youth. Encouraging these children to focus on the positive aspects of their bodies and personalities and to adopt sound health practices and practice good grooming fosters a more positive self-image.

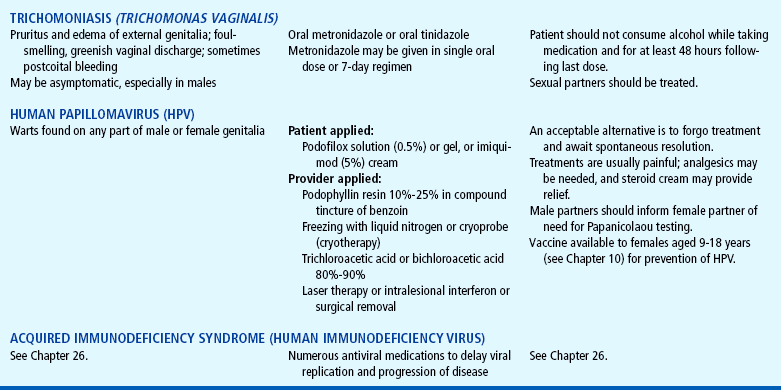

SEX CHROMOSOME DISORDERS

Most sex chromosome abnormalities are caused by an alteration in sex chromosome number (Table 17-1). The majority of these conditions are due to nondisjunction. An alteration in the number of sex chromosomes usually does not produce the profound defects that are associated with the autosomal disorders (trisomies). Intelligence may be normal or low normal, or the child may have some learning disabilities. Moderate or severe mental retardation is less common.

Turner Syndrome

Turner syndrome is caused by absence of one of the X chromosomes. Most girls who have this disorder have one X chromosome missing from all cells (45,XO). This disorder is often recognized at birth if the newborn has a webbed neck, low posterior hairline, widely spaced nipples, and edema of the hands and feet. This condition is often diagnosed in the preschool child because growth is restricted or delayed around 3 to 4 years of age. In some cases it may be diagnosed at puberty because of three features: short stature, delayed sexual development, and amenorrhea; individuals with Turner syndrome are generally infertile. They may also have difficulty with peer relationships and understanding social cues. They frequently exhibit behavioral problems, especially immature, socially isolated behavior. Diagnosis is confirmed on the basis of a negative sex chromatin test.

Therapy is individualized for these girls and consists primarily of female hormone treatment and psychologic counseling for both the child and parents. Linear growth can be increased by the administration of growth hormone if therapy is begun early. Estrogen therapy is initiated during the usual time for puberty to promote the development of secondary sex characteristics. Responses to estrogen therapy vary from girl to girl, but gradual feminization is accomplished to some degree in most individuals.

Klinefelter Syndrome

Klinefelter syndrome, the most common of all sex chromosome disorders, is caused by the presence of one or more additional X chromosomes and only one Y chromosome. Most males with this syndrome have a chromosome complement of 47,XXY. The disorder is infrequently diagnosed before puberty, at which time varying degrees of failure of adolescent virilization occur. Some males are not diagnosed until they appear for evaluation for infertility. All have absence of sperm in the semen (azoospermia), small testes, and defective development of secondary sex characteristics (gynecomastia, hypogonadism). In 80% of these boys there is a chromatin-positive buccal smear, and the extra chromosome is apparent on chromosome analysis.

Cognitive impairment is a frequent clinical finding and appears to be related to the number of X chromosomes. Boys may also have gross motor skill difficulties, a developmental language delay, poor verbal skills, reduced auditory memory, shyness, passivity, behavioral problems, and school difficulties. Therapy is directed toward enhancing the masculine characteristics through administration of testosterone.

Nursing Care Management

The nursing care of children with Turner or Klinefelter syndrome is primarily supportive. Nurses assist in the diagnosis, explain tests and therapies, and provide support and encouragement to the child and family. Because both disorders render the individual unable to reproduce, psychologic counseling is an important aspect of care. In young adults marriage and sexual relationships are possible, but alternative reproductive options, such as artificial insemination and adoption, should be discussed.

DISORDERS RELATED TO THE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Menarche, or the first menstrual period, occurs relatively late in female pubertal development. Although girls vary in the onset and rate of progression of pubertal development, the sequence and tempo should be the same. When an adolescent is seen with a complaint of absence of menses, a careful history of the timing of her pubertal development will help to determine if there is a need for further evaluation or if reassurance is all that is necessary.

Primary amenorrhea is an absence of secondary sex characteristics and no uterine bleeding by 14 to 15 years of age, or absence of uterine bleeding with secondary sex characteristics by 16 years of age (Master-Hunter and Heiman, 2006). No uterine bleeding after attaining a sexual maturity rating of 5 on the Tanner scale (see Figures 16-1 and 16-2) for 1 year, or after breast development for 4 years, is also considered primary amenorrhea (American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2006). The cause of primary amenorrhea may be anatomic, hormonal, genetic, or idiopathic. A thorough patient and family history and physical examination will provide clues to the etiology.

Secondary amenorrhea is defined as the absence of menses for 6 months or at least three cycles after menstruation was previously established. Irregular menstrual cycles are common within the first year or two after menarche. These early cycles may be anovulatory, resulting in regular, irregular, or absent bleeding; however, cycle lengths outside the range of 21 to 45 days should be investigated (American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2006). Girls with a later onset of menarche will take longer to establish regular ovulatory cycles.

Pregnancy is the most common cause of secondary amenorrhea and should be ruled out in both types of amenorrhea, even if the adolescent denies sexual activity. Other factors that disturb the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and cause secondary amenorrhea include physical or emotional stress; sudden environmental change; hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism; polycystic ovary disease; chronic illness; extreme weight loss or gain; intensive exercise; anorexia nervosa or bulimia; ovarian disturbance; and extrinsic pharmacologic agents, especially phenothiazines, contraceptive steroids, and heroin.

DYSMENORRHEA

A certain amount of discomfort during the first day or two of the menstrual flow is extremely common. Most girls experience cramping, abdominal pain, backache, and leg ache, but in a few cases the pain is intolerable and incapacitating. Primary dysmenorrhea is painful menses not related to any pelvic disease. Secondary dysmenorrhea is defined as painful menses with a pathologic condition such as endometriosis, salpingitis, or congenital anomalies of the müllerian system.

Primary dysmenorrhea usually begins at the time of menarche or within 6 to 12 months. The pain begins with menstrual flow or hours before the onset of bleeding each month, usually continuing for 48 to 72 hours. The exact etiology is unknown, but the pain is clearly related to ovulatory cycles. The overproduction of uterine prostaglandins has been implicated; women with dysmenorrhea have higher levels of prostaglandins. Overproduction of vasopressin (a hormone that stimulates the contraction of muscular tissue) may also contribute to dysmenorrhea.

A careful history should include the onset of symptoms; the duration, type of pain, and relationship to menstrual flow; age at menarche; family history of dysmenorrhea; and sexual history. The nurse should also ask about previous treatments, including dosages of medications. Associated symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and leg and back pain are helpful for diagnosis and treatment. Depending on the results of the history, the physical examination may include a gynecologic examination.

Therapeutic Management

First-line treatment for adolescents with dysmenorrhea is the administration of NSAIDs, which block the formation of prostaglandins for 2 to 3 days of the menstrual cycle. The girl should be instructed to begin the medication at the first sign of cramping or bleeding. Girls with regular menstrual cycles benefit from beginning the medication 1 or 2 days before the onset of their menses. The medications should be taken with food.

Cyclic estrogen therapy and oral contraceptives are also effective. Simple exercises such as pelvic rocking, assuming the knee-chest position, and breathing exercises may be beneficial. Adequate personal hygiene, participation in regular activities, and methods to decrease stress should be discussed with the adolescent. Dietary changes, supplements, and herbal medications are often used to treat dysmenorrhea. Randomized controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that vitamins B1 and E are effective in the treatment of dysmenorrhea (Dennehy, 2006).

Nursing Care Management

All adolescent girls need reassurance that menstruation is a normal function. When nurses are asked for advice regarding menstrual problems, they have a valuable opportunity to engage in health teaching concerning menstrual physiology; hygiene; and the importance of a well-balanced diet, exercise, and general health maintenance. Health teaching can dispel myths about menstruation and femininity. When assessment indicates a potential problem and the need for evaluation, referral to an appropriate practitioner, health service, or clinic may be necessary.

One of the most difficult experiences facing the adolescent girl is the gynecologic examination. Whether it is her first experience or not, she is often filled with apprehension. Almost all adolescents are extremely self-conscious about their bodies and the changes taking place. They need continuing support in the form of anticipatory guidance regarding what to expect and suggestions of what to do to relax during the procedure. Most girls favor a semisitting position, which has the additional advantage of allowing eye contact during the procedure. Sometimes a pillow helps the patient feel more comfortable and less vulnerable. The provision of a mirror for the girl to see what is taking place if she so desires helps the examiner explain various aspects of anatomy. When possible, it is important to respect the adolescent’s request for a female provider.

VAGINITIS

Vaginitis can be caused by physical, chemical, or infectious agents. Physical causes may include a forgotten tampon; chemical irritants include bubble bath, douching, deodorant pads, and tampons. Removing the offending material or discontinuing use of the irritating substance is usually all that is necessary to treat physical or chemical vaginitis. Infectious vaginitis can be caused by Candida fungi (yeast), Trichomonas protozoa parasites, or bacteria. Diagnosis is confirmed with microscopic evaluation of vaginal secretions or vaginal culture. Treatment varies depending on the infectious agent.

Health teaching is important in the prevention and management of vaginitis. Adolescent girls need reassurance that increased vaginal mucus can occur at the time of ovulation, before menstruation, or with sexual excitement. Many teenage girls mistake these variations as signs of infection. Girls should be taught to wipe from front to back after toileting and to realize that vaginitis can result from irritation, foreign objects, and sexual activity. Nurses should stress the importance of an evaluation to determine the exact cause.

DISORDERS OF THE MALE REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM

Most obvious anomalies, such as hypospadias, hydrocele, phimosis, and cryptorchidism, are identified with corrective measures instituted during early childhood. The most frequent problems related to the reproductive organs in later childhood are:

Infections, such as urethritis (see Urinary Tract Infection, Chapter 27)

Infections, such as urethritis (see Urinary Tract Infection, Chapter 27)

Penile problems, such as nonretractable foreskin in uncircumcised males, carcinoma, and trauma

Penile problems, such as nonretractable foreskin in uncircumcised males, carcinoma, and trauma

Scrotal conditions, such as varicocele (elongation, dilation, and tortuosity of the veins superior to the testicle)

Scrotal conditions, such as varicocele (elongation, dilation, and tortuosity of the veins superior to the testicle)

Testicular torsion (a condition in which the testicle hangs free from its vascular structures, which can result in partial or complete venous occlusion with rotation)

Testicular torsion (a condition in which the testicle hangs free from its vascular structures, which can result in partial or complete venous occlusion with rotation)

Tumors of the testes are not common, but when manifested in adolescence, they are generally malignant and demand immediate evaluation. Testicular cancer is the most common solid tumor in males 15 to 34 years of age. The usual presenting symptom for testicular cancer is a heavy, hard, painless mass (either smooth or nodular) that is palpated on the testis. Treatment involves surgical removal of the affected testicle (orchiectomy) and possibly chemotherapy and radiation if metastasis has occurred.

Nursing Care Management

The adolescent boy is also self-conscious about his changing body and needs preparation for a genital examination. The most successful approach is to assume a matter-of-fact attitude toward the examination, explain precisely what will take place, and maintain a continuous commentary about what is being done and the findings at each phase of the examination.

The routine health assessment of every adolescent boy should include teaching about testicular cancer and how to perform a testicular self-examination (TSE) every month. This rare malignancy is curable if detected early. Nurses are in an ideal position to teach TSE in a manner that is respectful of the adolescent boy’s anxieties and that promotes early treatment (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

The normal testicle is a firm organ with a smooth, egg-shaped contour; the epididymis is palpated as a raised swelling on the superior aspect of the testicle and should not be taken for an abnormality.

GYNECOMASTIA

The male breast, although not strictly part of the male reproductive system, responds to hormonal changes. Some degree of bilateral or unilateral breast enlargement occurs frequently in boys during puberty. It is estimated that approximately half of adolescent boys have transient gynecomastia, usually lasting less than 1 year, which subsides spontaneously with achievement of male development. A careful assessment of the pubertal stage at the onset of gynecomastia; medication history, including anabolic steroids; and the exclusion of renal, liver, thyroid, and endocrine disorders or dysfunction allow the examiner to reassure the adolescent that the changes are pubertal gynecomastia and that no further assessment is indicated.

If the condition persists or is extensive enough to cause embarrassment or to produce doubts about gender identity in the young boy, plastic surgery may be indicated for cosmetic and psychologic considerations. Administration of testosterone has no effect on breast development or regression and may aggravate the condition.

Nursing Care Management

Treatment usually consists of assurance to the adolescent and his parents that this is a benign and temporary situation. A physical examination with palpation is necessary to differentiate gynecomastia from increased adiposity caused by being overweight. Adolescents who are distressed about physical integrity and masculinity may benefit from the knowledge that this condition occurs in more than 50% of all adolescent boys.

HEALTH PROBLEMS RELATED TO SEXUALITY

It is estimated that by the time adolescents finish high school, more than half of them will have had at least one sexual experience with a member of the same or opposite gender (Mosher, Chandra, and Jones, 2005). Many serious health consequences are associated with adolescent sexual activity, including unplanned pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs); additional health problems may arise from an increased number of sexual partners over time and incomplete education regarding sexual practices in adolescents. Health professionals must understand the issues related to adolescent sexual activity and the psychosocial dynamics that influence them.

ADOLESCENT PREGNANCY

In recent years the teenage pregnancy rate has shown a continual downward trend. Between 1990 and 2003, birth rates for teenagers 15 to 17 and 18 to 19 years of age declined nationally for all races. In 2005 the teenage birth rate decreased 2% (from 2004) to 40.4 births per 1000 women ages 15 to 19 (Hamilton, Martin, and Ventura, 2006). The decline over the past decade has been attributed to a drop in the number of repeat pregnancies and an increase in the use of condoms and long-term hormonal contraceptive methods among adolescents. However, adolescent birth rates still remain high in the United States compared with those in other developed countries (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2005a). The number of teens initiating sexual intercourse before the age of 15 has significantly decreased in the past 10 years (Anderson, Santelli, and Morrow, 2006). Teens who postpone the initiation of sexual intercourse decrease their risk for STDs, including HIV.

The reduction in teen pregnancy is an important national goal because of the risk for negative outcomes for both mother and child. A wide range of factors put an adolescent at risk for pregnancy, including having sex with an older partner, the type of contraception used; living in poverty; having a mother who was a teen parent; school failure; lack of access to confidential health care; and living in a poor community where access to education, health care, and work may not be optimal.

With better facilities available for care, the mortality associated with teenage pregnancies is decreasing, but morbidity remains high. Teenage girls and their unborn infants are at greater risk for complications of both pregnancy and delivery. The most frequent complications are premature labor and low-birth-weight infants, high neonatal mortality, iron deficiency anemia, fetopelvic disproportion, and prolonged labor. The pregnancies of adolescents less than 15 years old are more frequently complicated by obstetric problems and neonatal morbidity and mortality than those of adolescents ages 15 to 19. The increased risk has traditionally been thought to be related to incomplete growth and physiologic immaturity. However, pregnancy can take place only after the girl has achieved an advanced state of growth and sexual maturity. Therefore concerns are dietary habits, substance use (especially cigarettes), STDs, the effects of poverty, and a late onset of prenatal care.

Nursing Care Management

A pregnant teenager needs careful assessment by the nurse to determine the level of social support available to her and her partner. The adolescent needs to make many important decisions and may not have the life experience to know how to cope with this stress. Whenever possible, guidance from the adults in her life will be invaluable. Information about options to continue the pregnancy and parent the child, continue the pregnancy with adoption, or terminate the pregnancy with abortion should be given in a nonjudgmental manner. If the adolescent chooses to continue the pregnancy, prenatal care should be initiated as soon as possible. No matter what the teenager decides, nutrition information will be necessary.

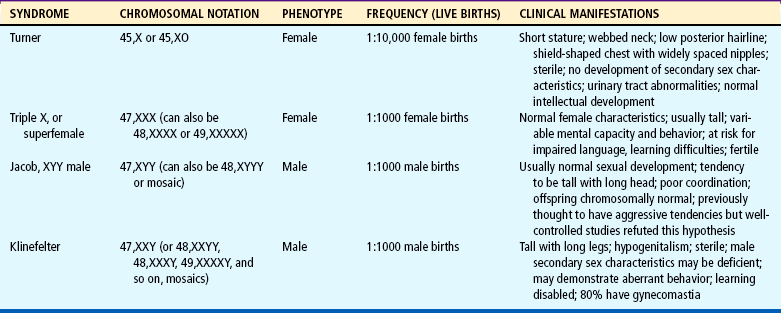

CONTRACEPTION

Family planning services have developed and expanded during recent years, but the need for contraceptive services as part of the health care of adolescents remains great. The birth control pill and condom remain the most popular methods for adolescents; 3-month injectable contraception is more popular among lower-income adolescents. Adolescents commonly delay seeking contraceptive information. The typical interval from onset of sexual intercourse until the first visit for contraception is 1 year. A pregnancy scare is usually the precipitating event for the contraception appointment. Counseling about contraceptive options should be conducted in a manner that is consistent with the cognitive level of the adolescent. The adolescent should be given accurate information about the risks and benefits of each method before making a choice.

Many teenagers feel ambivalent regarding their sexual activity and avoid many contraceptives because their use seems too premeditated and implies that sex is planned rather than a spontaneous activity. Most of these girls believe that sex is all right if it is not planned. This may often play a role in adolescents delaying contraception, waiting for a relationship that is “close enough.” A close relationship would allow the adolescents to accept and acknowledge their sexual activity.

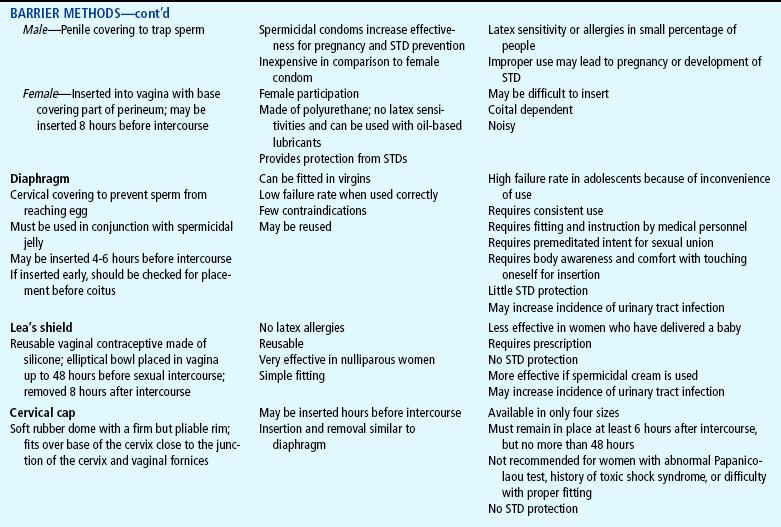

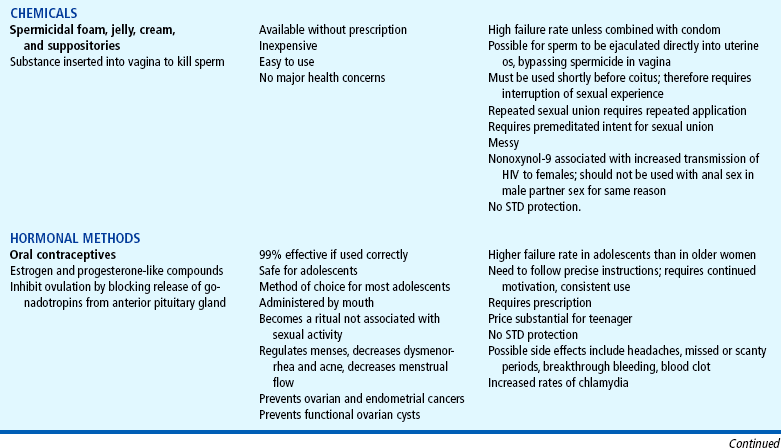

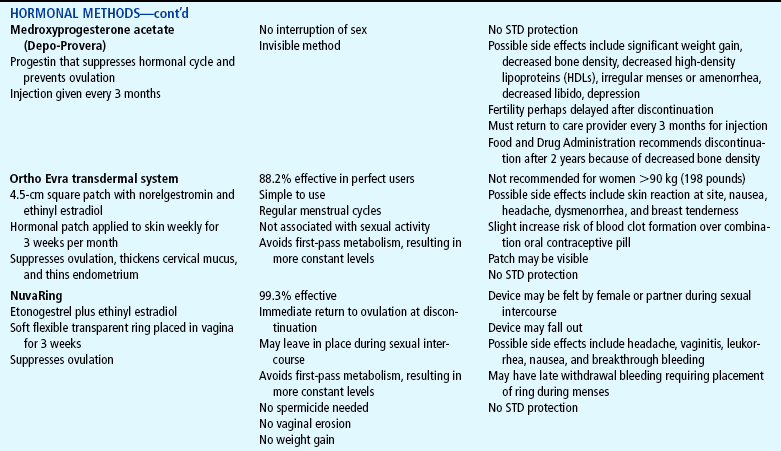

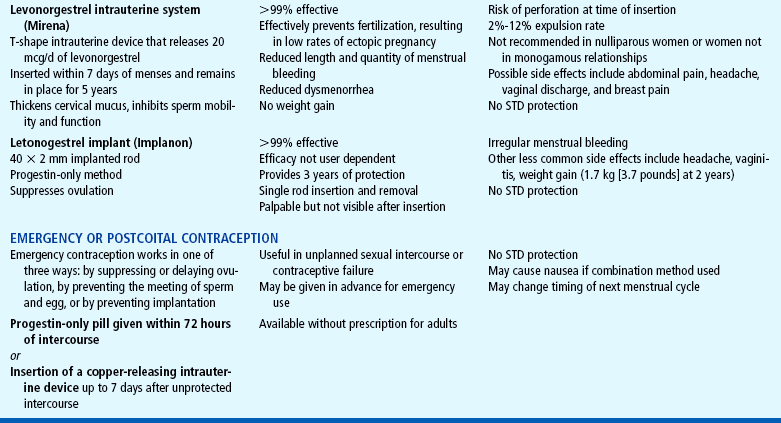

The choice of a safe and effective contraceptive method must be suited to the individual (Table 17-2). The choice is based on preference after the adolescent is informed of the benefits and disadvantages. Motivation is necessary for most methods. For example, the pill is effective if used correctly, but the adolescent must remember to take the pill at approximately the same time every day. For many young women, a medroxyprogesterone injection (Depo-Provera) is an ideal choice because it is extremely effective and is administered every 12 weeks, but side effects such as weight gain and decreased bone mineralization may make it undesirable. Sexually active adolescents need to know that contraceptive devices other than condoms do not prevent STDs. Condom use is still important and must be discussed with all sexually and non–sexually active adolescents.

Confidentiality is a critical issue when discussing contraception with adolescents. Privacy is important to adolescents as they struggle to forge a personal identity and establish social relationships. Adolescents are particularly concerned about the judgments of others. The predominant belief among many health professionals is that parental notification is important but that the “parents’ rights” view is not necessarily sensitive to the health needs and basic rights of youth. No evidence substantiates the belief that providing contraceptive guidance contributes to sexual irresponsibility and promiscuity.

Nursing Care Management

Nurses are often involved in providing education about contraception. Such education is ideally combined with ongoing sex education. Although sexual abstinence is a highly desirable form of contraception for teenagers, nurses working with adolescents must recognize that teens feel multiple pressures to engage in sexual intercourse. Postponing sexual involvement requires effective communication and decision-making skills. Adolescents benefit from role-playing refusal skills and opportunities to practice making decisions in a safe environment. Information about safe sex must be provided, and role-playing how to discuss condom use with a partner is helpful to teenagers.

Education concerning contraception should be provided in both oral and written form. All available methods, including their benefits, disadvantages, and side effects, should be discussed. Concrete, concise language must be used, demonstrations of how to use the contraceptive should be provided, and adolescents should repeat all instructions in their own words. If teenagers are using oral contraceptive pills, they should be encouraged to use a daily activity as a reminder or cue to take the pill. A knowledgeable phone triage person should be available for questions and concerns. Parents or other important adults may be included in all discussions, with the adolescent’s permission.

SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASES

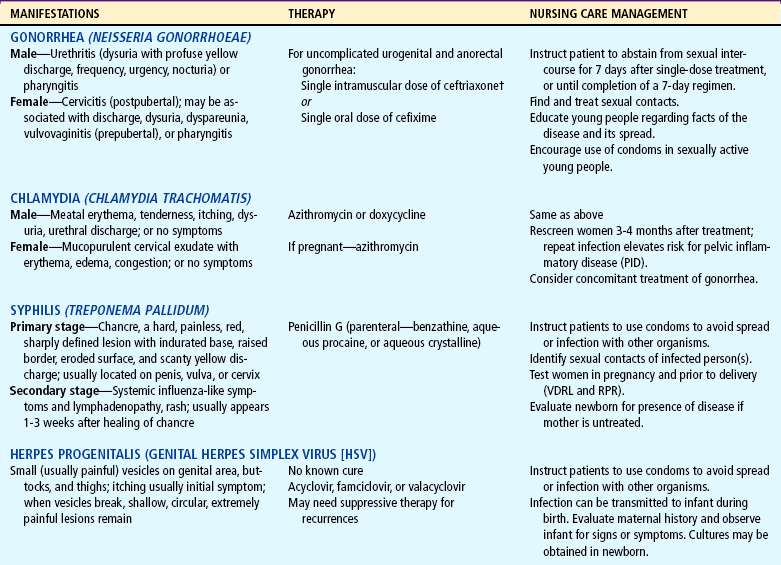

Sexually active adolescents are at increased risk (compared with adults) for the acquisition of STDs. Physiologically, the adolescent girl’s cervix has a large ectropion, which is composed of columnar epithelial cells that are much more susceptible to STDs, especially human papillomavirus (HPV) and Chlamydia infection. The adolescent’s immune system also contributes to the increased risk because the adolescent has not had an opportunity to develop resistance to these organisms (Shrier, 2004). Behavioral factors contributing to increased risk include initiating sexual intercourse at an early age, high disease prevalence among sexual partners, and inconsistent use of barrier or other types of contraceptives. In addition, adolescents may participate in unprotected oral or anal sex in the belief that STDs cannot be transmitted through those activities (Shrier, 2004). A listing of common STDs is included in Table 17-3.

TABLE 17-3

Selected Sexually Transmitted Diseases*

*Updated information on specific treatment of STDs may be accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment.

†Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Update to CDC’s Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2006: fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections, MMWR 56(14):332-336, 2007.

The rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea are reported to be highest among adolescent girls ages 15 to 19 years, and high rates of HPV exist in the adolescent population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006a). Whereas much emphasis has been placed on prevention of HIV in the past decade, other STDs have received little attention in regards to prevention. Lack of awareness regarding one’s susceptibility to STDs when engaged in unprotected sexual activity, be it oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse, is perhaps one of the greatest dangers adolescents face.

Therapeutic Management

Effective treatment of both males and females with an STD involves administration of the appropriate therapeutic agent. Treatment of sexual partners is also an essential part of therapy. Adolescents need help to develop strategies to inform their partner and to abstain from sex until both have completed treatment.

A totally effective prophylaxis against infection is not yet available; therefore preventive efforts must be directed toward finding and treating affected persons, locating and examining contacts of affected persons, educating young people regarding the facts of the disease and its spread, and encouraging the use of condoms in sexually active young people.

Nursing Care Management

Nursing responsibilities encompass all aspects of STD education, confidentiality, prevention, and treatment. Part of the sex education of young people should include providing information about these diseases, including their symptoms and treatment, and dispelling the myths associated with their mode of transmission. Many vulnerable adolescents are uninformed or misinformed about STDs.

Primary prevention efforts for STDs include encouraging abstinence and postponing sexual involvement; encouraging condom use; and ensuring vaccination for hepatitis A and B and HPV. Nurses play a role in secondary prevention by helping to identify early cases and referring adolescents for treatment. Nurses can also be involved in tertiary prevention by decreasing the medical and psychologic effects of STDs; conducting support groups for adolescents with HIV, herpes simplex virus, and HPV infections; and assisting pregnant adolescents in obtaining adequate prenatal screening and treatment of STDs.

PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is an infection of the upper genital tract (endometrium, fallopian tubes, and ovaries), most commonly caused by sexually transmitted bacteria, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and a variety of other anaerobic bacteria.

The long-term effects of PID include infertility because of tubal scarring, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic abdominal pain. It is estimated that each year 1 million females of reproductive age experience an episode of PID, with approximately 20% of cases occurring in teenagers. Women under the age of 25 years have a one in eight chance of experiencing PID compared with those over age 25 years, whose risk is one in 80.

Presenting symptoms in the adolescent may be generalized, including fever; abdominal pain; urinary tract symptoms; and vague influenza-like manifestations, such as malaise, nausea, diarrhea, or constipation. A pelvic examination is indicated for every sexually active female who complains of lower abdominal pain to evaluate for the possibility of PID.

PID is of major concern to nurses because of its devastating effects on the reproductive tract. Approximately 25% of females experiencing PID may have short-term complications, such as acute abscess formation in the fallopian tubes (tubo-ovarian abscess), or long-term complications, such as chronic pelvic pain, dyspareunia (painful coitus), or adhesion formation. Most significant, however, is the increased risk for ectopic pregnancy or infertility, which results from tubal scarring.

Prevention is the primary concern of health care professionals. Barrier contraceptive methods, such as condoms, seem to offer the best protection for preventing STDs and PID. Sexually active female teenagers should be screened every 6 months to detect asymptomatic STDs, and treatment should be initiated to prevent PID and all associated complications. Reinfection with Chlamydia organisms is associated with a higher incidence of PID. Females who have had a Chlamydia infection should be rescreened for Chlamydia 3 months after treatment.

SEXUAL ASSAULT (RAPE)

The adolescent girl is particularly vulnerable to sexual assault, and 75% of adolescents who are raped know their assailant (Clements, Speck, Crane, and others, 2004). Females are more likely to report these experiences than males (Neinstein, 2002). In each instance the victim is potentially subjected to serious physical or emotional harm. There is no typical victim. Sexual assault victims are of all ages, ethnic groups, and economic groups and are of either gender, although adolescents and children with a physical or developmental disability are more vulnerable to sexual abuse than their peers. Acquaintance rape is far more common than stranger rape; however, stranger rape is reported more often.

An understanding of the legal definitions of sexual assault, rape, acquaintance rape, and statutory rape is essential for the nurse to identify, treat, and manage adolescent victims (Box 17-1).

Statutory rape laws have been revised in many states across the country. The motivation for tougher laws and greater enforcement is to decrease teen pregnancy, increase male responsibility, and decrease welfare dependency. Traditionally, statutory rape laws have been concerned with the protection of girls. In the past 20 years, many laws have been rewritten to be gender neutral. Statutory rape laws require reporting to child protective services or local law enforcement. One risk of strict statutory rape enforcement is that girls may not seek health care for reproductive care, prenatal care, or domestic violence. Young people may fear not only for themselves, but also for their partner. However, sexual coercion of teens by adults remains a problem and results in STDs and adolescent pregnancy.

In the United States, it is illegal for anyone to have sexual intercourse with a child under the age of 12 years. These laws protect the health and safety of children incapable of protecting themselves. When consensuality is considered in statutory rape laws and cases, it implies that adolescents are morally and socially responsible for sexual contact that occurs with adults. This does not afford adolescents the same protections provided to children under the age of 12 (Kandakai and Smith, 2007).

Nurses can obtain information about their state statutory rape reporting responsibilities from state or local child protective services agencies, legal counsel, rape crisis organizations, state or local law enforcement agencies, or the state nurses’ association. The limits of confidentiality should be clearly reviewed with each adolescent patient before beginning the interview about sexual activity.

There has been a reported increase in the use of drug-facilitated sexual assaults. Older adolescents and young adults at parties, bars, and raves are at risk for having a drug slipped into their beverage when they are not looking. Substances most often referred to as “date rape” drugs are flunitrazepam (Rohypnol), a sedative-hypnotic benzodiazepine; γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), a sleep aid; and ketamine, an anesthetic agent (Schwartz, Milteer, and LeBeau, 2000). However, alcohol is the most widely used drug in such assaults. These fast-acting drugs cause disinhibition, passivity, relaxation of muscles, and lasting amnesia. The victim wakes up in strange surroundings and realizes she has been sexually assaulted. She may not report the crime for days or weeks or may never report it. Acquaintance rape is frequently underreported because the victim may believe she contributed to the act in some way. The victim may not identify the experience as rape because it does not fit the standard concept.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The rape victim may exhibit a variety of reactions (Box 17-2), and the circumstances of the initial medical evaluation may be frightening and stressful. The initial contact with the rape victim must be supportive because the interrogation and associated activities have the potential to add to the trauma of the sexual assault. First of all, the victim needs to know that she (or he) is (1) all right and (2) not being blamed for the situation.

It is important to obtain a clear account of the circumstances of an alleged rape without forcing the victim to relive a painful experience. Information includes date, time, location, and an accurate description of any type of sexual contact. The physical examination is carried out as soon as possible, since physical evidence deteriorates rapidly. The victim should not bathe or shower before the examination.

The young person is always told in advance in understandable terms exactly what to expect in the way of tests and procedures, and the explanation is accompanied by strong emotional support. The victim is examined thoroughly, including nongenital areas, for evidence of injury that might substantiate the use of force.

The forensic examination of a sexual assault victim must follow strict legal requirements. The medical record may provide key evidence for the legal case. Practitioners specially trained for rape examination should be used when possible. Nurses are often members of this group and are known as sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs). Evaluation for STDs is an important part of the evaluation. All potential infection sites are tested to detect gonorrhea, chlamydia, and trichomoniasis. Blood samples for syphilis, hepatitis B virus, and HIV are obtained as a baseline (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001a). The adolescent is reexamined at appropriate intervals (4 to 6 weeks for syphilis; 2 to 3 days for gonorrhea) to determine if a disease was acquired from the assailant.

Prophylactic treatment for chlamydia and gonorrhea is recommended. Female victims should be provided with emergency contraception. The recommendation for HIV prophylaxis varies depending on the geographic area, the circumstances of the assault, and the known HIV status of the perpetrator. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2006a) maintains updates and recommendations for treatment of STDs incurred as a result of sexual assault.*

Therapeutic Management

Adolescents who have been raped arrive at the emergency department or practitioner’s office under a variety of circumstances. They are usually brought by parents, friends, or police officers, but some may seek medical help on their own. It is advisable to obtain parental consent for examination, but the examination may be performed without parental consent if the adolescent is mature and the parents are unavailable. A female observer should be present during the history and examination of female victims who are examined by a male practitioner. Whether a parent should be present during the examination is determined on an individual basis. The parent’s presence is usually encouraged if the parent is supportive and the young person agrees.

Rape Trauma Syndrome

The term rape trauma syndrome refers to the victim’s reaction to a sexual assault. The syndrome involves two phases: (1) the acute phase of disorganization of lifestyle and (2) a long-term process of reorganization. These phases encompass behavioral, somatic, and psychologic reactions to the stressful event. Counseling should begin immediately upon the adolescent’s entrance into the emergency department with follow-up within the first 24 hours. Early intervention has been shown to be effective in decreasing the extent of rape trauma syndrome (Patel and Minshall, 2001).

Nursing Care Management

Many of the approaches that have been described for the sexually abused child (see Chapter 14) apply to the adolescent. Sexual assault is a devastating experience with long-lasting effects. The primary goal of nursing care is to avoid inflicting further stress on the adolescent, who is often angry, confused, frightened, embarrassed, and filled with self-blame. The nurse must do everything possible to reduce the stress of the interrogation and examination. Although most health professionals and law enforcement officers are sensitive to the needs of the adolescent and attempt to make the process as nonstressful as possible, the nurse should be alert to cues that indicate the victim is being overstressed.

Follow-up care of the rape victim is essential and extends over a long period. Aside from the universal need for emotional support, the needs of rape victims vary widely and depend on the nature of the incident, the victim’s age when the rape occurred, the physical and emotional injuries sustained by the victim, the legal actions being considered as a result, the resources available for informal support, and the anticipated reactions of persons in the informal support network (see Family Focus box).*

EATING DISORDERS

Few problems in childhood and adolescence are so obvious to others, are so difficult to treat, and have such long-term effects on health as obesity. Several different definitions have been proposed for obesity and overweight. Obesity has been defined as an increase in body weight resulting from an excessive accumulation of body fat relative to lean body mass. Overweight refers to the state of weighing more than average for height and body build. Currently, the body mass index (BMI) measurement is recommended as the most accurate method for screening children and adolescents for obesity. The BMI measurement is strongly associated with subcutaneous and total body fat and also with skinfold thickness measurements. It is also highly specific for children with the greatest amount of body fat. Pediatric growth charts that include BMI for age and gender are available from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.* Children with a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles are considered overweight, and obesity is defined by a BMI greater than the 95th percentile (Moran, 2003).

Regardless of the definition used, the number of overweight children in the United States is increasing and may be approaching epidemic status (Shulman, 2004). In children ages 6 to 11 years, the prevalence of childhood overweight remained fairly constant in the years 1963 and 1974 at approximately 4% and 5.5%, respectively. However, in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, those numbers have steadily climbed to reach 16% in both 6- to 11-year-olds and 12- to 19-year-olds in 2001 to 2002; almost 32% of children ages 6 to 19 were at risk for overweight (Hedley, Ogden, Johnson, and others, 2004). African-American and Hispanic children and youth are disproportionately represented by a higher prevalence of overweight (21.5% and 21.8%, respectively) when compared with non-Hispanic Caucasian children (12.3%) (National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, 2003). These numbers double if they include children defined as being at risk for overweight (<85th percentile on growth chart). A study of 9464 American Indian schoolchildren ages 5 to 18 years found that 39% were overweight, and a further review of tribes across the United States found that 30% to 46% of American Indians were at risk for overweight (<85th percentile) (Hardy, Harrell, and Bell, 2004).

Because adult obesity is associated with increased mortality and morbidity from a variety of complications, both physical and psychologic, adolescent obesity is a serious condition. Research indicates that overweight children and adolescents are at risk of continuing to be obese as adults, thereby experiencing the health and social consequences of obesity much earlier than children and adolescents of normal weight. Parental obesity increases the risk of overweight by twofold to threefold (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, and others, 2005). The probability that overweight school-age children will become obese adults is estimated at 50%, whereas the likelihood that overweight adolescents will become obese adults is estimated at 70% to 80% (National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, 2003).

Obesity in childhood and adolescence has been related to elevated blood cholesterol, high blood pressure, respiratory disorders, orthopedic conditions (Taylor, Theim, Mirch, and others, 2006), cholelithiasis, some types of adult-onset cancer (MacKenzie, 2000), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, and others, 2005; Angulo, 2002), and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Ehtisham, Barrett, and Shaw, 2000). The incidence of metabolic syndrome was 50% in a study group of overweight and obese adolescents (Weiss, Dziura, Burgert, and others, 2004). Common emotional consequences of obesity include poor body image, low self-esteem, social isolation, and feelings of depression and rejection (Sjöberg, Nilsson, and Leppert, 2005).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

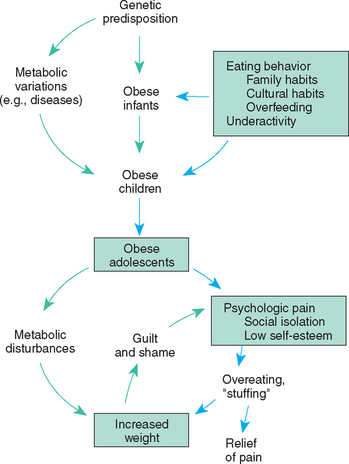

Obesity results from a caloric intake that consistently exceeds caloric requirements and expenditure and may involve a variety of interrelated influences, including metabolic, hypothalamic, hereditary, social, cultural, and psychologic factors (Fig. 17-2). Because the etiology of obesity is multifactorial, the treatment requires multilevel interventions.

Birth weight is not a contributing factor in detection and prediction of childhood obesity; obese children do not have higher birth weights than nonobese children. There is, however, a high correlation between childhood adiposity and parental adiposity.

A balance between energy intake and energy expenditure is a critical factor in regulating body weight. Factors that raise energy intake or decrease energy expenditure by even small amounts can have a long-term impact on the development of overweight and obesity. For example, a positive balance of one serving of a sweetened juice or soft drink (about 120 kcal) per day would produce a 50 kg (110 pound) increase in body mass over a 10-year period (Hill, Wyatt, Reed, and others, 2003).

Familial influence is an epidemiologic consideration in regard to a child’s weight. Twin studies suggest that approximately 50% to 70% of the tendency toward obesity is inherited (Kiess, Galler, Reich, and others, 2001). Twin studies have also suggested that this tendency is a combination of genetic and environmental factors. If both parents are lean, the likelihood of the child becoming overweight is just 9%. When both parents are obese, there is a 60% to 80% increase in the likelihood of the child becoming obese (Koeppen-Schomerus, Wardle, and Plomin, 2001). The specific influences of genes and environment within the developing child is not well defined. The increasing rates of obesity within genetically stable populations suggest that environmental and some perinatal factors (e.g., bottle feeding) are contributors to the current increases in childhood obesity (National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, 2003).

Fewer than 5% of the cases of childhood obesity can be attributed to an underlying disease. Such diseases include hypothyroidism; adrenal hypercorticoidism; hyperinsulinism; and dysfunction or damage to the central nervous system as a result of tumor, injury, infection, or vascular accident. Obesity is a frequent complication of muscular dystrophy, paraplegia, Down syndrome, spina bifida, and other chronic illnesses that limit mobility.

A major focus of obesity research has been on appetite regulation. The expression of appetite is chemically coded in the hypothalamus by distinctive circuitry. Orexigenic substances produce signals that promote eating behaviors, and anorexigenic substances promote the cessation of eating behaviors. Feedback loops between signals have been identified where one signal peptide is able to alter the secretion of another signal peptide. No one signal has been identified as the gatekeeper of appetite. It is apparent that an entire network of signals, including their frequency and amplitude, is responsible for triggering eating behaviors.

There is little evidence to support a relationship between obesity and “low metabolism.” Small differences may exist in regulation of dietary intake or metabolic rate between obese and nonobese children that could lead to an energy imbalance and inappropriate weight gain, but these small differences are difficult to accurately quantify. No differences in basal metabolic rate, sleeping metabolic rate, respiratory quotient, heart rate, or total energy expenditure have been found in normal weight children with or without a familial predisposition to overweight (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, and others, 2005). In childhood, overeating is the dominant feature in obesity, whereas in adult life, reduced physical activity with normal intake is more likely.

The tendency toward obesity is manifested whenever environmental conditions are favorable to excessive caloric intake, such as an abundance of food, limited access to low-fat foods, reduced or minimum physical activity, and snacking combined with excessive television viewing. Family and cultural eating patterns, as well as psychologic factors, play an important role; many families and cultures consider fat to be an indication of good health. It is not uncommon for obese children to have families that emphasize large meals or admonish children for leaving food on their plates. Parents may have an exaggerated concept of the amount of food children require and expect them to eat more than they need. The prevalence of obesity shows a marked difference between upper- and lower-class children, with differences often becoming apparent before 6 years of age. Lower socioeconomic groups have a greater prevalence of obesity, especially in girls. Physical activity may also be influenced by sociocultural factors.

Some community factors that influence activity patterns include unsafe neighborhoods that keep children from playing outside. Many communities lack affordable and accessible areas for low-income youth to be active, thus limiting opportunities for young people to participate in physical activities. Social policies also contribute to obesity. The increased availability of high-fat foods, pricing strategies that promote unhealthy food choices, and overzealous food advertising that targets children and adolescents with high-fat and high-sugar foods are some examples.

Institutional factors also influence patterns of obesity and decreased physical activity. Many school policies allow students to leave school for lunch. Vending machines in school often are filled with high-fat and high-calorie foods and soft drinks. Although well-balanced, nutritious school lunches may be available to students, they will often opt for less nutritious choices such as high-fat snacks.

Physical inactivity has also been identified as an important contributing factor in the development and maintenance of childhood overweight. There is little doubt that physical activity has decreased in elementary and secondary schools in the United States. Consequently, most of a child’s physical activity must occur within the family or outside of school. Decreased physical activity within the family is a powerful influence on children, since children imitate their parents and other adults. Parental obesity and low levels of physical activity are correlated with decreased physical activity in children.

The growing attraction and availability of many sedentary activities, including television, video games, computers, and the Internet, have greatly influenced the amount of time that children spend participating in sedentary behaviors. A study conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation demonstrated that children watch an average of 2½ hours of television per day, and that one in five kids watches TV for 5 hours or more every day (Rideout, Foehr, Roberts, and others, 1999). When combining television viewing with video games, it is estimated that children may spend as much as 6½ hours per day on various media, which takes time away from meaningful activities such as exercise and reading (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001b).

Psychologic factors also affect eating patterns. In infancy, children experience relief from discomfort through feeding and learn to associate eating with a sense of well-being, security, and the comforting presence of a nurturing person. Eating is soon associated with the feeling of being loved. In addition, the pleasurable oral sensation of sucking provides a connection between emotions and early eating behavior. Many parents use food as a positive reinforcer for desired behaviors. This practice may become a habit, and the child may continue to use food as a reward, a comfort, and a means of dealing with depression or hostility. Many individuals eat when they are not hungry or in response to boredom, loneliness, sadness, depression, or tiredness. Difficulty in determining feelings of satiety can lead to weight problems and may compound the factor of eating in response to emotional rather than physical hunger cues.

Eating behaviors are closely related to memory. Memory and appetite are chemically encoded, with each individual having his or her own circuitry relating to eating behaviors. Like memory, the circuitry can be modified over time (Feldman, Friedman, and Sleisenger, 2002).

Diagnostic Evaluation

A careful history is obtained regarding the development of obesity, and a physical examination is performed to differentiate simple obesity from increased fat that results from organic causes. A family history of obesity, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and dyslipidemia should be obtained for all children who are overweight or at risk for overweight. Specific information from the patient and family about the effects of obesity on daily functioning—for example, problems with nighttime breathing and sleep, daytime sleepiness, pain in the joints, ability to keep up with family activities and peers at school—will be helpful. The physical examination should focus on identifying comorbid conditions and identifiable causes of obesity. For some, psychologic assessment, by interviews and standardized personality tests, may provide insight into the personality and emotional problems that contribute to obesity and that might interfere with therapy.

It is useful to estimate the degree of obesity to determine the component of body weight that can be modified. All the following methods have been used to assess obesity: BMI, body weight, weight-height ratios, weight-age ratios, hydrostatic (underwater) weight, skinfold measurements, bioelectrical analysis, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and neutron activation. Each of these methods has advantages and disadvantages. Hydrostatic, or underwater, weighing provides the most accurate measurement of lean body weight.

BMI is currently considered the best method to assess weight in children and adolescents. The calculation is based on the individual’s height and weight. In adults, BMI definitions are fixed measures without regard for sex and age. The BMI in children and adolescents varies to accommodate age- and gender-specific changes in growth. The formula for BMI calculation is:

BMI measures in children and adolescents are plotted on growth charts that enable heath care professionals to determine BMI-for-age for the patient (see Appendix B).

The initial assessment of obese children and adolescents should include screening to evaluate for comorbidities. The history is an important guide to determine the workup. A complete physical examination is important. Some areas to focus on include (1) skin for stretch markings and discolorations (e.g., acanthosis nigricans), (2) joints for swelling and evidence of pain, and (3) airway for evidence of obstruction and enlarged tonsils. Basic laboratory studies include a fasting lipid panel; fasting insulin level; fasting glucose hepatic enzymes, including γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT); and, in some institutions, hemoglobin A1c. Other studies, such as a sleep study, metabolic studies, and radiographic evaluations, may be added based on the history and physical examination. These assessments may determine whether the patient needs a referral to specialty services for more focused evaluation and treatment, such as endocrinology (insulin resistance, diabetes), hepatology (elevated liver enzymes, NAFLD), orthopedics (Blount disease), or pulmonary medicine (sleep-disordered breathing, continuous positive airway pressure).

Therapeutic Management

The best approach to the management of obesity is a preventive one. Early recognition and control measures are essential before the child or adolescent reaches an obese state. Health care providers must educate families about the medical complications of obesity, and families are encouraged to be involved in the treatment plan.

The treatment of obesity is difficult. Many approaches do not achieve long-term success. The average individual only loses about 5% to 10% of his or her weight with available therapies. Losing weight can have a significant positive effect on many comorbidities, but unfortunately the lost weight is frequently regained in a year or two (Yanovski and Yanovski, 2002).

Diet modification is an essential part of weight-reduction programs. Dietary counseling is directed toward improving the nutritional quality of the diet rather than on dietary restriction. Children should avoid fad diets. Most dietitians and nutrition experts recommend a diet with low-saturated fat, moderate total fat (≤30%), and five servings of fruits and vegetables, consistent with the MyPyramid* food guide for children. Also, promoting high-fiber foods and avoiding highly refined starches and sugars will decrease caloric intake. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans† may be used as a guide for caloric intake for adolescents concerned about weight control; these guidelines also emphasize daily exercise in weight management for children and adolescents. Many programs recommend using a food diary as a helpful tool to increase awareness of food choices and eating behaviors. The goal is to encourage the individual to make healthier choices in food selection and discourage eating food by habit or to appease boredom.

In patients with severe obesity, strict diets have been used, such as the protein-sparing modified fast, a hypocaloric, ketogenic diet that is designed to provide enough protein to minimize loss of lean body mass during weight loss. Such diets need to be closely monitored and should be used only with multidisciplinary teams that include a physician, nutritionist, and behavioral therapist. Generally, the diet consists of 1.5 to 2.5 g of protein per kilogram. The intake of carbohydrates is low enough to induce ketosis. The benefits of the diet are relatively rapid weight loss and anorexia induced by ketosis. Potential complications include protein losses, hypokalemia, hypoglycemia, inadequate calcium intake, and orthostatic hypotension. Potassium and calcium supplements and adequate calorie-free beverages can minimize these complications (Baker, Barlow, Cochran, and others, 2005). It is difficult to sustain such diets over the long term, and the long-term outcomes of using these diets have not been established.

Some drugs have been used to promote weight loss in children with certain conditions such as metformin in obese adolescents with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinism, octreotide for hypothalamic obesity caused by intracranial tumors, growth hormone in children with Prader-Willi syndrome, and leptin for congenital leptin deficiency. The drug sibutramine, in addition to behavioral therapy, significantly reduced BMI and body weight more than placebo; however, the drug was associated with side effects (tachycardia and hypertension) (Berkowitz, Fujioka, Daniels, and others, 2006).