Chronic Illness, Disability, or End-of-Life Care for the Child and Family

PERSPECTIVES ON THE CARE OF CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

THE FAMILY OF THE CHILD WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Impact of the Child’s Chronic Illness or Disability

Coping with Ongoing Stress and Periodic Crises

NURSING CARE OF THE FAMILY AND CHILD WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Provide Support at the Time of Diagnosis

Support Family’s Coping Methods

PERSPECTIVES ON THE CARE OF CHILDREN AT THE END OF LIFE

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

Identify the scope of and changing trends in care of children with special needs.

Identify the scope of and changing trends in care of children with special needs.

Identify the major reactions of and effects on the family of a child with a special need.

Identify the major reactions of and effects on the family of a child with a special need.

Define the stages of adjustment to the diagnosis of a chronic condition.

Define the stages of adjustment to the diagnosis of a chronic condition.

Recognize the impact of the illness or disability on the developmental stages of childhood.

Recognize the impact of the illness or disability on the developmental stages of childhood.

Outline nursing interventions that promote the family’s optimal adjustment to the child’s chronic disorder.

Outline nursing interventions that promote the family’s optimal adjustment to the child’s chronic disorder.

Outline nursing interventions that support the family at the time of death.

Outline nursing interventions that support the family at the time of death.

PERSPECTIVES ON THE CARE OF CHILDREN WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

A number of terms and defining characteristics have been used to describe chronic illness and disability in children (Box 18-1). In recent years there have been continuing efforts to develop a definition that better identifies the numbers of children living with chronic conditions, as well as the impact on health and social services (Jackson, 2000; van Dyck, Kogan, Heppel, and others, 2004). Currently children with special health care needs are defined as children who have or are at increased risk for a chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional condition and who also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that generally required by children (Msall, Avery, Tremont, and others, 2003; Newacheck, Strickland, Shonkoff, and others, 1998).

Ongoing progress in medical and technologic disease management has contributed to the growing number of children with special health care needs (Palfrey, Tonniges, Green, and others, 2005). The number of U.S. children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) diagnosed each year declined by 75% from 1992 to 2000 (Yogev and Chadwick, 2004). Technologic advances have substantially increased the survival of extremely low– and very low–birth-weight infants (Jackson, 2000). Children with disabilities are more likely to be in poor health than children without disabilities (Newacheck and Halfon, 1998). The result of such progress is that an estimated 15% to 18% of the children in the United States live with a chronic illness or disability and require specialized health care of a type or amount beyond that generally required by children (Perrin, 2004).

The most commonly occurring conditions causing disability are diseases of the respiratory tract and impairments of speech, special senses, and intelligence. Mental and nervous system disorders account for about one sixth of all childhood disability (Newacheck and Halfon, 1998).

The impact of chronic illness and disability in children is wide ranging. Chronic conditions in children present most families with additional tasks, responsibilities, and concerns (Ray, 2002). A child’s activity level and developmental opportunities can be affected. Days can be lost from school. Children with chronic illness or disability may be at increased risk for behavior or emotional problems. Parents may lose days from work, experience financial strain, and be challenged both emotionally and physically as they cope with care of the child.

Siblings are also affected by having a “different” brother or sister and may simultaneously feel guilt and anger or jealousy toward their ill sibling. Additionally, secondary losses such as the ability to participate in extracurricular activities or social events occur because of routines imposed by the affected child’s chronic condition.

TRENDS IN CARE

Focusing on the child’s developmental level rather than chronologic age or diagnosis emphasizes the child’s abilities and strengths rather than disabilities. Attention is directed to normalizing experiences, adapting the environment, and promoting coping skills. Nurses often are in vital positions to redirect attention from the pathologic model with its focus on weaknesses and problems to the developmental model to meet the unique needs of the child and family.

A developmental focus also considers family development. The life cycle of the family unit reflects changing ages and needs of family members, as well as changing external demands. A family member’s serious illness or disability can cause significant stress or crisis at any stage of the family life cycle. Just as with individual development, family development may be interrupted or even regress to an earlier level of functioning. Nurses can use the concept of family development to plan meaningful interventions and evaluate care (see Developmental Theory, Chapter 3).

Family-Centered Care

Children’s physical and emotional health, as well as cognitive and social functioning, is strongly influenced by how well their families function (Schor, 2003). The importance of family-centered care—a philosophy that considers the family as the constant in the child’s life—is especially evident in the care of children with special needs (see also Family-Centered Care, Chapter 1). As parents learn about the youngster’s health care needs, they often become experts in delivering care. Health care providers, including nurses, are adjuncts to the child’s care and need to form partnerships with parents. Effective communication and negotiation between parents and nurses are essential to forming trusting and effective partnerships and finding the best ways to meet the needs of the child and family (Corlett and Twycross, 2006). Collaborative relationships are characterized by communication, dialogue, active listening, awareness, and acceptance of differences (Schor, 2003).

Family–Health Care Provider Communication

The disclosure of a serious acute or chronic illness of a child is one of the most stressful aspects of communication between families and health care professionals. Often, parents have suspected for some time that something is wrong with their child and believe that their concerns were minimized or ignored by health care professionals (Whitehead and Gosling, 2003; Thomlinson, 2002; Cohen, 1995). After a diagnosis is made, numerous studies have shown that parents are not always satisfied with the way in which information is given. Factors that influence parent dissatisfaction with communication include unsympathetic and brief diagnostic interviews, lack of privacy during diagnostic discussions, and lack of opportunity to ask questions. Conversely, parents report satisfaction when they perceive the health care providers giving information in an open and honest manner with respect for the parents’ need for privacy and time to express emotions and ask questions (Davies, Davis, and Seibert, 2003). Similar factors are important in communication of changes in the child’s condition throughout the course of the illness.

Providing information to families with a chronically ill child should be a process of repeated discussions to allow the family to process the information and their reactions to that information, and allow them to ask for clarification and further information. Nurses play an important role in ensuring that families’ needs are met during discussions related to the child’s diagnosis, condition, and treatment. This requires assessment regarding how much information the family is comfortable with, what they understand of the information already given to them, and how they are coping with the information both cognitively and emotionally. Nurses should ensure that the appropriate health care professionals address any concerns or further questions that families may have.

Establishing Therapeutic Relationships

Another important aspect of family-centered care of chronically ill children is establishing a therapeutic relationship with the child and family, which has been shown to predict improved health-related outcomes (Denboba, McPherson, Kenney, and others, 2006). Families, most often the mother, take on enormous responsibility in providing technical care and symptom management of their child’s condition outside the health care institution (O’Brien and Wegner, 2002; Raina, O’Donnell, Rosenbaum, and others, 2005; Swallow and Jacoby, 2001). To build successful therapeutic relationships with families, it is necessary for nurses to recognize parents’ expertise with regard to their child’s condition and needs. Care conferences, especially multidisciplinary meetings that include the family and key health professionals, provide an opportunity for sharing ideas and expressing feelings or concerns.

Individual discussions, especially with the case manager, primary nurse, clinical nurse specialist, or nurse practitioner, help establish a consistent and flexible care plan that can prevent conflicts or deal with these conflicts before they disrupt care. In family-centered care, the goal is to maintain the integrity of the leadership role and support the family during times of crisis or stress.

The Role of Culture in Family-Centered Care

Issues of culture, ethnicity, and race affect access to services, utilization, and follow-through with referrals and recommendations (van Dyck, Kogan, McPherson, and others, 2004; Wise, Wampler, Chavkin, and others, 2002; Wood, Smith, Romero, and others, 2002; Zuvekas and Taliaferro, 2003). For some ethnic and minority populations, cultural understandings of illness and disability, the structure of family life, social roles for individuals who are disabled, and other factors related to the perception of children may differ from those of mainstream American culture. These factors may affect family needs and family choices regarding the care of their child with special needs.

Although culture cannot completely explain how an individual will think and act, understanding cultural perspectives can help the nurse anticipate and understand why families may make certain decisions. Cultural attributes such as values and beliefs regarding illness or disability and its causation, social roles for the ill or disabled, family structure, the role of children, childrearing practices, self vs group orientation, spirituality, and time orientation also affect a family’s response to illness or disability in a child (Carnevale, Alexander, Davis, and others, 2006; Carter, 2002; Marshall, Olsen, Mandleco, and others, 2003; Rehm, 1999; Sterling and Peterson, 2003).

When parents are informed of their child’s chronic illness, interpreters familiar with both culture and language should be used. Children, family members, and friends of the family should not be used as translators because their presence may prevent parents from openly discussing the issues. When working with people of cultural backgrounds different from their own, nurses must listen carefully with an initial goal of understanding and articulating the family’s perspective. The ability to interpret the mainstream medical culture to the family is also important. Furthermore, every effort is made to incorporate traditional cultural beliefs of a family into treatment plans. Developing a care plan in conjunction with the family, considering their preferences and priorities, is an important first step in formulating a plan that best meets the family’s needs, no matter what their cultural background (Ahmann, 1994; Ochieng, 2003).

Shared Decision Making

Shared decision making among the child, family, and health care team can result from open, honest, culturally sensitive communication and the establishment of a therapeutic relationship between the family and health care providers. In a shared decision-making model the health care professionals provide honest, clear information regarding diagnosis, prognosis, treatment options, and risk/benefit assessment. The patient and/or family then shares information with the health care team regarding important family values, acceptable levels of discomfort or inconvenience, and the ability to comply with treatments being recommended (Charles, Gafni, and Whelan, 1997). This process allows them to discuss all options in terms of the risks and benefits to the child and family, the prognosis or expected course of the illness, and the impact on the family’s resources (Box 18-2).

Normalization

Normalization refers to behaviors and intentions of the disabled to integrate into society by living life as persons without a disability would (Morse, Wilson, and Penrod, 2000). For the chronically ill or disabled child, such behaviors could include attending school, pursuing hobbies and recreational interests, and achieving employment and a level of independence. For their families, it may entail adapting the family routine to accommodate the ill or disabled child’s health and physical needs (McDougal, 2002).

Children with chronic illness and disability and their families face numerous challenges in achieving normalization. Families move between the “normal” of living with the experience of chronic childhood illness and the “normal” of the healthy outside world; they often redefine “normal” based on their particular experiences, needs, and circumstances (Nelson, 2002; Deatrick, Knafl, and Murphy-Moore, 1999).

Nurses can assist families in normalizing their lives by assessing the family’s everyday life, social support systems, coping strategies, family cohesiveness, and family and community resources. Interventions could include encouraging families to reduce stress through delegation of care and family tasks, identifying ways to incorporate care into current routines, structuring the home environment to encourage the child’s engagement in age-appropriate activities, and ensuring families have access to appropriate community support services (Jokinen, 2004; Shepard and Mahon, 2000). Being supportive of the child’s illness and treatment and actively including the family in all aspects of care will improve their self-esteem and promote further development (Shepard and Mahon, 2000).

Home care represents the return to a system and set of priorities in which family values are as important in the care of a child with a chronic health problem as they are in the care of other children. Home care seeks to achieve goals that are consistent with the developmental model (Stein, 1985):

With appropriate training and support, families provide complex procedures and treatments in the home. Parents are challenged to retain a homelike setting among monitors, ventilators, and other sophisticated equipment. Throughout the text, home care is discussed as appropriate for specific conditions. The process of transition from hospital to home is elaborated on in Chapters 20 and 21.

Paralleling normalization and home care is the process of mainstreaming, or integrating children with special needs into regular classrooms. Just as the home is the natural environment for children, so school must also be included as an essential component of the children’s overall physical, intellectual, and social development. Children who attend school have the advantages of learning and socializing with a wide group of peers. There is an increased focus on individualization as plans are made to meet the academic needs of these children along with those of the rest of the students.

A variety of supplemental programs have been designed in the school system to accommodate special needs, both at school age and younger, through early intervention, which consists of any sustained and systematic effort to assist children from birth to age 3 years who are disabled and developmentally vulnerable. This change and increasing opportunities for normalization for children with special needs in large part have resulted from the passage of (1) the Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (Public Law 94-142) and its 1990 amendments (Public Law 101-476), which changed the name of the act to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA); (2) the Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of 1986 (Public Law 99-457), which directs states to develop and implement statewide comprehensive, coordinated, multidisciplinary interagency programs of early intervention services for infants and toddlers with disabilities, as well as support services for their families; and (4) the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. Nurses can provide parents with information about these laws and in some cases may participate in the development of individualized educational programs (IEPs) or individualized family service plans (IFSPs) for children with special needs.

Managed Care

Managed care programs have become the major form of health care provision in the United States (Jackson, 2000). The transition to this model of care presents both opportunities and challenges with respect to the care of children with special health care needs. Managed care may promote continuity and coordination of care. Children rely on adults for access to health care and follow-up with treatment regimens, making it necessary to manage the child’s care in the context of the family (McPherson, Weissman, Strickland, and others, 2004; van Dyck, Kogan, McPherson, and others, 2004).

THE FAMILY OF THE CHILD WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

A major goal in working with the family of a child with special needs is to support the family’s coping and promote their optimal functioning throughout the child’s life. Long-term, comprehensive, family-centered approaches extend beyond supporting the child and family during the critical periods of diagnosis and hospitalization. Rather, comprehensive care involves forming parent-professional partnerships that can support a family’s adaptation to the many changes that may be necessary in day-to-day life, determine expectations of and for the child, and provide a long-term perspective (Box 18-3).

The impact of a child’s medical or developmental condition is often experienced over time, initially as a crisis at the time of diagnosis, which may occur at birth, after a long period of physical or psychologic testing, or immediately after a tragic injury. The impact may also be felt before the diagnosis is made, when parents are aware that something is wrong with their child but before medical confirmation (Whitehead and Gosling, 2003; Thomlinson, 2002; Cohen, 1995).

The diagnosis and initial discharge home are critical times for parents (Coffey, 2006). Several factors can make it particularly difficult, including a long duration of uncertainty in the diagnostic process, negative perceptions of chronic illness or disability, insufficient information, and lack of mutual trust between parents and their child’s health care team (Cohen, 1995; Garwick, Patterson, Bennett, and others, 1995; Nuutila and Salanterä, 2006). Parental feelings of shock, helplessness, isolation, fear, and depression are common (Coffey, 2006; Nuutila and Salanterä, 2006). Throughout the first year, parents struggle to accept the child’s diagnosis, care, and uncertainty of the future (Coffey, 2006). Providing explicit and uncomplicated information to parents in an empathic way (Nuutila and Salanterä, 2006); assessing the family’s daily routine, living conditions, background knowledge, skills and abilities, and coping behaviors; and evaluating the family’s understanding of the information can encourage optimal support at the time of diagnosis and initial discharge home. It is also necessary to reassess parental needs for information and support on a routine basis (Nuutila and Salanterä, 2006).

Other critical times include the exacerbation of the child’s physical symptoms, which increases parental care; significant milestones for the child and his or her peers, particularly toddlerhood, entering kindergarten, and turning 18 years old, which increases parental stress; and advocating for the child during these times. Supporting parents, respecting their stress and emotions, and acknowledging their role as team members in the care of their child are important aspects of nursing care (Coffey, 2006; Nuutila and Salanterä, 2006).

IMPACT OF THE CHILD’s CHRONIC ILLNESS OR DISABILITY

Each member of a family who has a child with special needs is affected by the experience (Sullivan-Bolyai, Sadler, Knafl, and others, 2003). The effects on the parents and their responses are so critical that they directly influence the other members’ reactions and the child’s own coping.

Parents

In addition to the stress of grieving for the loss of a perfect child, parents are affected by whether or not they receive positive feedback from transactions with their child. Many parents feel satisfaction and fulfillment from the parenting role. For others, parenting may be a series of unrewarding experiences that contribute to feelings of inadequacy and failure (Box 18-4). These responses may be most evident in parents who are responsible for the child’s care. For example, parents may become preoccupied with their ability to carry out certain procedures, overlooking the child’s personal comfort and satisfaction or failing to offer praise for anything less than perfect cooperation or performance. They may pursue a frustrating activity until they achieve “success”–long after the child has become irritable and uncooperative. As a result, parents can become caught in a pattern of interaction that is mutually unrewarding and minimally productive. For these parents, several strategies may be helpful: education regarding what can reasonably be expected of their child, assistance in identifying the child’s strengths, praise for a parental job well done, and respite care so that parents can renew their energies.

Parental Roles.: Parenting a child with a chronic illness or disability requires much more than raising a typical child. In addition to attending to the routine aspects of parenting, parents of chronically ill children take on the added responsibility of performing complex technical care and symptom management, advocating for their child, and seeking and coordinating health and social services for their ill or disabled child. These added responsibilities must then be balanced with the needs of other family members, extended family and friends, and personal health and obligations to minimize consequences to the overall functioning of the family (Coffey, 2006; Ray, 2002).

Enormous demands may be placed on parental time, energy, and financial resources.

Often one partner remains at home to manage existing family responsibilities while the other remains with the ill child. The partner who is not included in the caregiving activities may feel neglected because all of the attention is directed toward the child and resentful that he or she is not sufficiently informed to be competent in the care. Without active participation in the child’s care, the parent has little appreciation of the time and energy involved in performing those activities. When this partner does attempt to participate, the other parent may criticize the less skillful efforts. As a result, communication and support for each other may be adversely affected.

The nurse can assist parents in avoiding role conflicts by providing anticipatory guidance early on. Teaching should address stressors often identified as having an impact on the marriage: (1) the burden of care at home assumed by primarily one parent, (2) the financial burden, (3) the fear of the child dying, (4) pressure from relatives, (5) the hereditary nature of the disease (if applicable), and (6) fear of pregnancy. Other causes of tension may center on the inconveniences associated with care, such as long waits for an appointment, lack of parking near care facilities, or lack of overnight accommodations. Certainly, these last stressors are within health professionals’ domain to minimize, if not eliminate.

Mother-Father Differences.: Mothers and fathers in the same family often adjust and cope differently as parents of a child with special needs. Some mothers experience a peaks-and-valleys periodic crisis pattern, whereas most fathers tend to experience a steady, gradual recovery. Some research suggests that mothers of children with certain conditions may be more susceptible to psychologic distress and fatigue than fathers (Tong, Kandala, Haig, and others, 2002). Mothers are most often the primary caregiver and are more likely than fathers to give up their job to care for their child, often resulting in social isolation (Coffey, 2006). Mothers often have greater needs for social support and positive appraisal of the situation, whereas fathers are more likely to use self-controlling behaviors to cope (Goldbeck, 2001; Mastroyannopoulou, Stallard, Lewis, and others, 1997).

The father of a child with special needs struggles with issues that may be distinct from those of the mother. He may think that his role of protector is challenged because he does not know how to help and cannot protect the family from the seemingly overwhelming recurring problems. With today’s increased emphasis on fathers’ involvement in the lives of their children, this loss is felt more profoundly than in the past. The extensive stresses in the family can leave the father feeling depressed, weak, guilty, powerless, isolated, embarrassed, and angry. Fearful that he will lose control or be viewed as weak or ineffectual, however, the father often hides his feelings and displays an outward confidence that may lead others to believe that everything is fine. Fathers worry about what the future holds for their children, their ability to manage the increasing financial burden, and the daily disruptions of the entire family (Davies, Gudmundsdottir, Worden, and others, 2004). Some fathers escape in their work as a means of dulling the pain. Common coping strategies are problem oriented and include praying, getting information, looking at options, and weighing choices, in addition to withdrawal (Mastroyannopoulou, Stallard, Lewis, and others, 1997).

Single-Parent Families.: Single-parent families are of special concern. The absence of a parent may result from divorce or death, or the parents may never have married. As the only parent of a child who may require extensive, sophisticated, and lifelong care, the single parent may feel an enormous burden. Available financial and emotional resources may already be stretched to the limit. A special effort should be made to assist the single parent in finding financial and support services that can ease the burden of care. Nurses can also assist the single parent in identifying helping roles that may be acceptable to relatives and friends.

Siblings

Results of studies on how siblings, almost exclusively European Americans, are affected by having a brother or sister with special needs are unclear (Barlow and Ellard, 2006). Generally, there is evidence that there is a negative effect on siblings of children with a chronic illness when compared with siblings of healthy children. This effect appears, however, to be decreasing in significance in recent years—most likely because of changes in public attitudes toward the ill and disabled (Sharpe and Rossiter, 2002). Siblings of children with chronic illness or disability report depression and anxiety more often than their peers (Rossiter and Sharpe, 2001). However, most investigators do agree that brothers and sisters of children with special needs are no more at risk for severe psychiatric problems than are siblings of children without chronic or disabling conditions. A number of factors increase the risk of negative effects for siblings of ill children. Responsibility for caregiving, differential treatment by parents, and limitations in family resources and recreational time are often the experience of siblings of ill or disabled children (Lobato and Kao, 2002) (Box 18-5).

An important factor in sibling adjustment and coping is information and knowledge regarding their brother’s or sister’s illness or disability. What siblings piece together or overhear is often much worse than the truth. Often they imagine gruesome things regarding the experiences related to the illness, treatment, and hospitalization (Shepard and Mahon, 2000). Latino siblings have reported less accurate information about their sibling’s condition than non-Latino siblings (Lobato, Kao, and Plante, 2005). Parents are usually in the best position to impart information, although they are often overwhelmed with the medical crisis at hand (Fleitas, 2000). Nurses can encourage parents to talk with the siblings about how they perceive their sick brother or sister and to be accepting of the siblings’ feelings. Nurses can be ideal educators and counselors of siblings during the course of their brother’s or sister’s illness (Shepard and Mahon, 2000).

COPING WITH ONGOING STRESS AND PERIODIC CRISES

Professionals can help families cope with stress by providing anticipatory guidance, providing emotional support, assisting the family in assessing and identifying specific stressors, aiding the family in developing coping mechanisms and problem-solving strategies, and working collaboratively with parents so that they become empowered in the process.

Concurrent Stresses Within the Family

The ability to deal with the overwhelming stress of a lifelong disability or illness is challenged further when additional stresses are present. Stressors may be situational or developmental. They may be related to marital difficulties, sibling needs, homelessness, or social isolation. Some families may simultaneously be struggling with a family member’s alcohol or other drug problem. Even relatively minor stressors, such as arranging care for siblings, managing the home, and traveling to distant treatment centers, can challenge a family’s ability to cope successfully.

Most families, regardless of their income or insurance coverage, have financial concerns. The costs of caring for a child with special needs can be overwhelming. Nurses and social workers can help a family review various options for financial assistance, including insurance, managed care, or health maintenance organization policies; Medicaid; Supplemental Security Income; Women, Infants, and Children program (WIC); the state Program for Children with Special Health Needs; disease-related associations; and local philanthropic organizations.

Coping Mechanisms

Coping mechanisms are behaviors aimed at reducing the tension caused by a crisis. Approach behaviors are coping mechanisms that result in movement toward adjustment and resolution of the crisis. Avoidance behaviors result in movement away from adjustment and represent maladaptation to the crisis. Several approach and avoidance behaviors used in coping with a chronic illness or disability are listed in the Nursing Care Guidelines box. None of the indexes can be used singly to assess the possible success or failure in resolving the crisis. Each behavior must be viewed in the context of all of the variables affecting the family. For example, the observation of several avoidance behaviors in an emotionally healthy family may denote significantly less risk to the successful resolution of the crisis than an equal number of avoidance behaviors in an individual who has few available supports.

Parental Empowerment

Empowerment can be seen as a process of recognizing, promoting, and enhancing competence. For parents of children with chronic conditions, empowerment may occur gradually as strength and capabilities are drawn on to master the child’s care, manage family life, and plan for the future. Advocating for the child and developing parent-professional partnerships are part of taking charge (Ray, 2002).

ASSISTING FAMILY MEMBERS IN MANAGING THEIR FEELINGS

Although some previous research has postulated stages of adaptation to a chronic illness or disability, there is a great deal of individual variation in responses to the diagnosis, adjustments made, and time frames for coming to terms with a diagnosis. It is important that professionals recognize and respect a wide range of reactions and coping mechanisms. In fact, members of the family of a child with a chronic illness or disability may experience a number of difficult emotions, including fear, guilt, anger, resentment, and anxiety. Learning to manage these emotions promotes adaptive coping (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Support from professionals, other family members, and friends can assist family members in managing their feelings. The following discussion examines some common phases of adjustment and emotional reactions.

Shock and Denial

The initial diagnosis of a chronic illness or disability is often met with intense emotion and is characterized by shock, disbelief, and sometimes denial, especially if the disorder is not obvious, as in chronic illness. Denial as a defense mechanism is a necessary cushion to prevent disintegration and is a normal response to grieving for any type of loss. Probably all family members experience various degrees of adaptive denial as they learn of the impact that the diagnosis has on their lives.

Shock and denial can last from days to months, sometimes even longer. Examples of denial that may be exhibited at the time of diagnosis include:

Attributing the symptoms of the actual illness to a minor condition

Attributing the symptoms of the actual illness to a minor condition

Refusing to believe the diagnostic tests

Refusing to believe the diagnostic tests

Delaying consent for treatment

Delaying consent for treatment

Acting happy and optimistic despite the revealed diagnosis

Acting happy and optimistic despite the revealed diagnosis

Refusing to tell or talk to anyone about the condition

Refusing to tell or talk to anyone about the condition

Insisting that no one is telling the truth, regardless of others’ attempts to do so

Insisting that no one is telling the truth, regardless of others’ attempts to do so

Denying the reason for admission

Denying the reason for admission

Asking no questions about the diagnosis, treatment, or prognosis

Asking no questions about the diagnosis, treatment, or prognosis

Generally, these mechanisms should be respected as short-term responses that allow individuals to distance themselves from the tremendous emotional impact and to collect and mobilize their energies toward goal-directed, problem-solving behaviors.

In children, the importance of denial has repeatedly been demonstrated as a factor in their positive coping with the diagnosis. Denial allows the child to maintain hope in the face of overwhelming odds and to function adaptively and productively. Like hope, denial may be an adaptive mechanism for dealing with loss that persists until a family or patient is ready or needs other responses.

Denial is probably the least understood and most poorly dealt-with reaction. Health professionals typically label denial as maladaptive and act inappropriately by attempting to strip it away by repeated and sometimes blunt explanations of the prognosis. However, denial becomes maladaptive only when it prevents recognition of treatment or rehabilitative goals necessary for the child’s optimal survival or development.

Adjustment

For most families, adjustment gradually follows shock and is usually characterized by an open admission that the condition exists. This stage may be accompanied by several responses, which are normal parts of the adaptation process. Probably the most universal of these feelings are guilt and self-accusation. Guilt is often greatest when the cause of the disorder is directly traceable to the parent, as in genetic diseases or accidental injury. However, it can occur even without any scientific or realistic basis for parental responsibility. Frequently the guilt stems from a false assumption that the disability is a result of personal failure or wrongdoing, such as not doing something correctly during pregnancy or the birth. Guilt may also be associated with cultural or religious beliefs. Some parents are convinced that they are being punished for some previous misdeed. Others may see the disorder as a trial sent by God to test their religious strength and faith. With correct information, support, and time, most parents master guilt and self-accusation. The ability to master resentful and self-accusatory feelings of having “caused” the child’s disorder is a crucial factor in determining the parents’ acceptance of their child.

Children, too, may interpret their serious illness as retribution for past misbehavior. The nurse should be particularly sensitive to the child who passively accepts all painful procedures. This child may believe that such acts are inflicted as deserved punishment. It is vital that parents and health care professionals reassure children that their illness is not their fault.

Other common and normal reactions to a diagnosis are bitterness and anger. Anger directed inward may be evident as self-reproaching or punitive behavior, such as neglecting one’s health and verbally degrading oneself. Anger directed outward may be manifested in either open arguments or withdrawal from communication and may be evident in the person’s relationship with any number of individuals, such as the spouse, the child, and siblings. Passive anger toward the ill child may be evident in decreased visiting, refusal to believe how sick the child is, or inability to provide comfort. Among the most common targets for parental anger are members of the staff. Parents may complain about the nursing care, the insufficient time physicians spend with them, or the lack of skill of those who draw blood or start intravenous infusions.

Children are apt to respond with anger as well, and this includes the affected child and the well siblings. Children are aware of the loss engendered by their illness or disability and may react angrily to the restrictions imposed or the feelings of being different. Siblings may also feel anger and resentment toward the ill child and parents for the loss of routine and parental attention. It is difficult for older children and almost impossible for younger children to comprehend the plight of the affected child. Their perception is of a brother or sister who has the undivided attention of their parents, is showered with cards and gifts, and is the focus of everyone’s concern.

During the period of adjustment, four types of parental reactions to the child influence the child’s eventual response to the disorder:

Overprotection, in which the parents fear letting the child achieve any new skill, avoid all discipline, and cater to every desire to prevent frustration (Box 18-6)

Rejection, in which the parents detach themselves emotionally from the child but usually provide adequate physical care or constantly nag and scold the child

Denial, in which parents act is if the disorder does not exist or attempt to have the child overcompensate for it

Gradual acceptance, in which parents place necessary and realistic restrictions on the child, encourage self-care activities, and promote reasonable physical and social abilities

Reintegration and Acknowledgment

For many families the adjustment process culminates in the development of realistic expectations for the child and reintegration of family life with the illness or disability in a manageable perspective. Because a large portion of this phase is one of grief for a loss, total resolution is not possible until the child dies or leaves home as an independent adult. Therefore one can regard adjustment as “increased comfort” with everyday living rather than a complete resolution.

This adjustment phase also involves social reintegration in which the family broadens its activities to include relationships outside of the home, with the child as an acceptable and participating member of the group. This last criterion often differentiates the reaction of gradual acceptance during the adjustment period from total acceptance, or perhaps is more descriptive of the acknowledgment process.

Many parents of children with chronic illnesses experience chronic sorrow, feelings of sorrow and loss that recur in waves over time. As the child’s condition progresses, parents experience repeated losses that represent further declines and new caregiving demands. Consequently, families must be assessed on an ongoing basis and offered appropriate support and resources as their needs change over time (Gravelle, 1997).

ESTABLISHING A SUPPORT SYSTEM

The diagnosis of a child with a serious health problem or disability is a major situational crisis that affects the entire family system. However, families can experience positive outcomes as they successfully deal with the many challenges that accompany a child with chronic illness or disability.

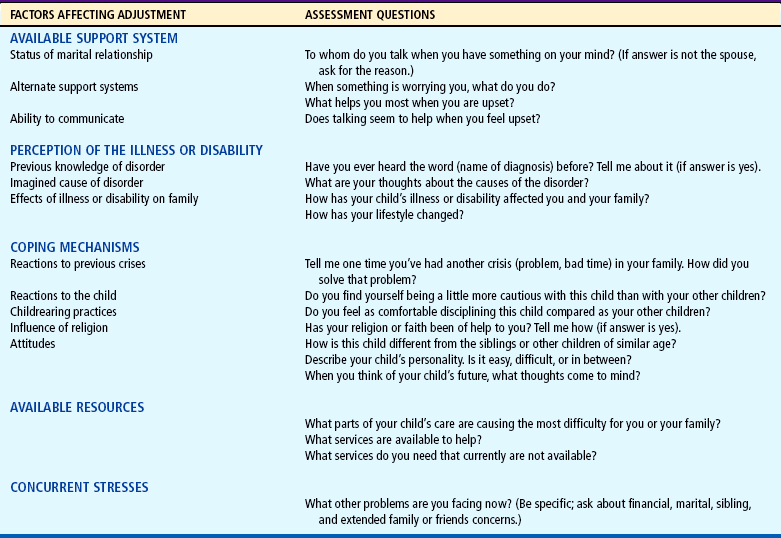

One nursing goal is to assess which families are at greater or lesser risk for succumbing to the effects of the crisis. Several variables—available support system, perception of the event, coping mechanisms, reactions to the child, available resources, and concurrent stresses within the family—influence the resolution of a crisis. Although most families cope well, the needs of families at risk are great. If they receive emotional support and guidance early, there is an increased likelihood that they will also cope successfully.

Although it is easy to assume that families of children with the most severe illnesses or disabilities would have the poorest adjustment, the severity of the condition reflects only one part of the overall picture. The level of adjustment is significantly influenced by the functional burden on the individual family (Stein, 1985). This concept considers the issues related to caring for and living with the child in relation to the family’s resources and ability to cope (Box 18-7). The family of a child with multiple disabilities demanding complex care, yet having many resources and coping skills, may adjust more successfully to the child’s situation than the family of a child with a less serious condition and few resources to counterbalance.

Intrafamilial resources, social support from friends and relatives, parent-to-parent support, parent-professional partnerships, and community resources interweave to provide a flexible web of support for the family of a child with a chronic condition.

THE CHILD WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

The child’s reaction to chronic illness or disability depends to a great extent on his or her developmental level, temperament, and available coping mechanisms; on the reactions of family members or significant others; and, to a lesser extent, on the condition itself. A child’s conceptual understanding of his or her own illness is based not only on age and developmental level, but also on the duration and type of experience accumulated with the disease. Knowledge of these variables is essential in providing the kind of information and support needed by these children to cope with a sometimes overwhelming situation.

DEVELOPMENTAL ASPECTS

The impact of a chronic illness or disability is influenced by the age at onset. Chronic illness affects children of all ages, but the developmental aspects of each age-group dictate particular stresses and risks for the child. The nurse must also recognize that children need to redefine their condition and its implications as they develop and grow. For example, appearance, skills, and abilities are highly valued by peers (Fig. 18-1); a teenager who is limited in any of these qualities is subject to rejection. This is especially marked when a physical disability interferes with sexual attractiveness.

FIG. 18-1 Children with any type of impairment should have the opportunity to develop their skills. (Courtesy Poyo/Hinton Photography.)

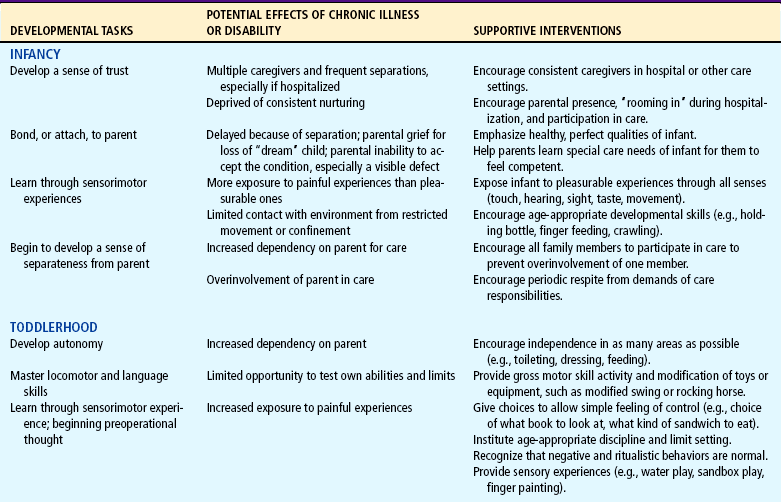

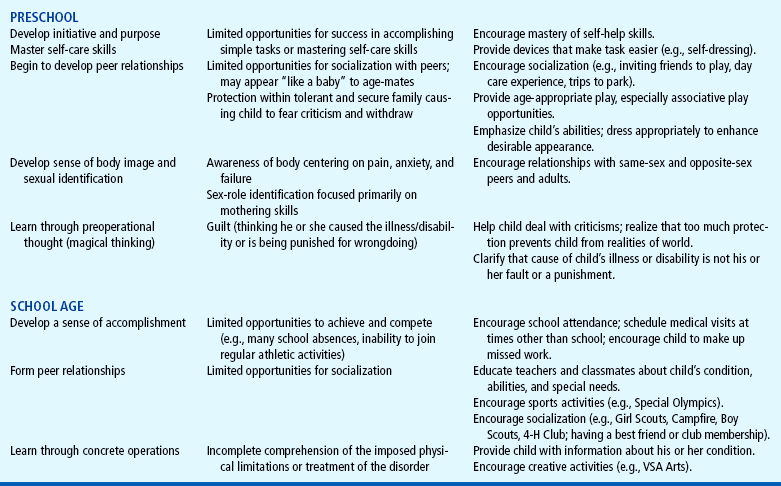

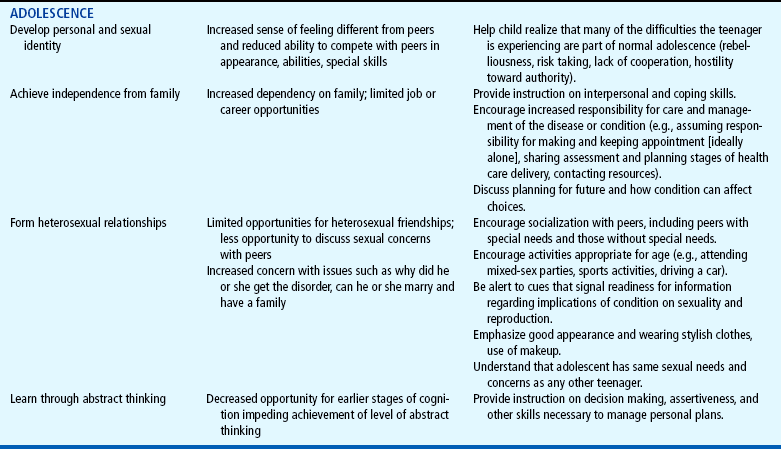

Children’s developmental concepts of illness are discussed in Chapter 21. An understanding of these developmental factors facilitates planning care to support the child and minimize the risks. Developmental aspects of chronic illness or disability on children are described in Table 18-2.

COPING MECHANISMS

Children with chronic conditions tend to use five distinct patterns of coping (Box 18-8). Children with more positive and accepting attitudes about their chronic illness use a more adaptive coping style characterized by optimism, competence, and compliance. They show fewer behavior problems at home and at school. The two maladaptive coping patterns— “Feels different and withdraws” and “Is irritable, is moody, and acts out”—are associated with poorer adaptation; children using these strategies have poorer self-concepts, more negative attitudes about their conditions, and more behavior problems at home and at school.

Well-adapted children gradually learn to accept their physical limitations and find achievement in a variety of compensatory motor and intellectual pursuits. They function well at home, at school, and with peers. They have an understanding of their disorder that allows them to accept their limitations, assume responsibility for care, and assist in treatment and rehabilitation regimens. They express appropriate emotions, such as sadness, anxiety, and anger, at times of exacerbations but confidence and guarded optimism during periods of clinical stability (Fig. 18-2). They are able to identify with other similarly affected individuals, promoting positive self-images and displaying pride and self-confidence in their ability to master a productive, successful life despite the disability.

FIG. 18-2 Periods of sadness and anger are appropriate in the child’s adjustment to a chronic illness or disability, especially during exacerbations of the disorder.

Hopefulness

Children, particularly adolescents, are sensitive to the presence or absence of hope. Hopefulness is an internal quality that mobilizes humans into goal-directed action that may be satisfying and life sustaining. A sense of hopefulness can produce increased participation in health-seeking behaviors and an improved sense of well-being (Ritchie, 2001).

Health Education and Self-Care

Health education is an intervention that promotes coping. Children need information about their condition, the therapeutic plan, and how the disease or the therapy might affect their particular situation. Children nearing puberty also need to understand the maturation process and how their disability may alter this event. For example, a youngster with Crohn disease should understand that this disorder is associated with growth failure and delayed puberty; a child with diabetes needs to know that hormonal changes and increased growth needs will alter food and insulin requirements at this time; and a sexually active girl with sickle cell anemia or systemic lupus erythematosus needs to be aware of the risks of pregnancy. The information should not be given all at once but should be timed appropriately to meet the changing needs of the youngsters, and it should be described and repeated as often as the situation demands.

RESPONSES TO PARENTAL BEHAVIOR

Parental behavior towards the child is one of the most important factors influencing the child’s adjustment. Children’s perceptions of their mothers’ support and maternal perceptions of psychosocial impact of the child’s chronic illness on the family were shown to be two of the greatest predictors of children’s psychologic adjustment (Immelt, 2006). In addition, family organization and illness-related support and involvement of parents influence children’s adjustment to chronic illness (Schor, 2003). They often display pride and confidence in their ability to cope successfully with the challenges imposed by their disorder. Anticipatory guidance by the nurse and encouragement of normalizing practices may assist parents in facilitating positive adjustment in their children.

TYPE OF ILLNESS OR DISABILITY

The type of illness or disability also influences the child’s emotional response. Interestingly, children with more severe disorders often cope better than those with milder conditions. However, the presence of multiple conditions may place a child at risk for more behavioral problems (Newacheck and Halfon, 1998). Considering children’s cognitive ability and their delay in achieving abstract thinking until adolescence, it is likely that an obvious condition is easier to accept because its limitations are concrete. For example, children who are blind or physically disabled are constantly reminded of their inability to run. However, children with cardiac defects not only live by rules they do not understand, but also only vaguely and occasionally sense their illness, such as when they try to run and experience dyspnea and fatigue. Therefore some chronic illnesses pose special threats to children.

The onset of a disabling condition may generate a state of confusion for children, who may have trouble differentiating between actual bodily functions and their image of their bodies. They may also experience problems in identifying themselves and those extensions of self (e.g., wheelchairs, braces, crutches, other mechanical or prosthetic devices) and may have difficulty in accepting functional aids.

NURSING CARE OF THE FAMILY AND CHILD WITH SPECIAL NEEDS

Because the nurse may meet a family during any phase of the adjustment process, several assessment areas are important (see Nursing Process box). The family’s ability to cope with previous stresses influences the current situation, and answers to questions about their usual coping skills are enlightening. Knowledge of concurrent stresses, such as financial, marital or nonmarital, and career or unemployment, helps identify families who may have fewer resources to cope with the child’s needs.

Finally, awareness of the family members’ reactions to the child and the illness or disability is important. Sample questions that the nurse and family can use to evaluate the support system, perception of the illness, coping mechanisms, resources, and concurrent stresses are listed in Table 18-1. Because factors affecting the family’s response may change at any point during the illness, assessment must be a continuous process.

Special challenges exist in assessing the child’s feelings about having a disability. Chapter 6 presents several approaches to encourage a child to discuss feelings about the condition. The nurse should use a variety of communication techniques, such as drawing and play, as assessment tools rather than relying solely on parental reports. Often, children are neglected partners in their care, and their unique needs are not identified (Young, Dixon-Woods, Windridge, and others, 2003; Dixon-Woods, Young, and Henry, 1999).

The needs of working parents and siblings also should be assessed, a goal that requires flexibility in scheduling appointments to include these important family members. When working parents know that their input is valuable, they will often change their work schedule to meet with a health professional. Because siblings can be of any age, the use of appropriate communication strategies for assessment must be considered. Nonverbal techniques such as those discussed in Chapter 6 should be considered for these children.

The main objective in working with the family is to help them cope effectively with those stresses imposed by the child’s special needs. To achieve this goal, the entire family should be considered in every aspect of the implementation process (see Family Focus box).

PROVIDE SUPPORT AT THE TIME OF DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis is a critical time for parents and can influence how they perceive their health care providers throughout care. Although they may not hear or remember all that is said to them, they frequently sense a certain attitude of acceptance, rejection, hope, or despair that may influence their ability to absorb the shock and begin adapting to the family’s altered future.

Parents may be encouraged to be together when they are informed of their child’s condition, thus avoiding the problem of one parent having to interpret complex findings and deal with the initial emotional reaction of the other. The informing session should take place in a private, comfortable setting free of distractions and interruptions, in an atmosphere in which the parents feel free to express their emotions (Fig. 18-3). Their emotional needs are acknowledged by showing acceptance of such expressions as crying, sadness, anger, and disappointment. Emotional support is offered by having tissues available if a family member cries and demonstrating through facial and body language that indeed this is a difficult and painful period. Although touching is a powerful expression of empathy, it must be used wisely. For example, it can prematurely terminate free expression of feelings, especially when combined with statements such as “Everything will be all right.” Nurses should also be aware of cultural issues regarding touching (see Chapter 4).

FIG. 18-3 Informing session should take place in a private, comfortable setting free of distractions and interruptions.

Parents should receive the kind of information they desire. This can be assessed by asking questions such as, “Do you prefer to hear detailed information?” Parents or other family members may have different preferences regarding the amount of information they wish to hear. Most parents want a clear, simple explanation of the diagnosis; a prediction of possible futures for the child; advice on what to do next; an opportunity to ask questions; a warm, sympathetic listener; and, most important, time. Understanding of explanations is elicited with such questions as “Do you see what I mean?” or “Is this clear to you?” Technical terms are used with simple definitions. If the parents are unaware of the term, they are given written literature or at least a written summary of the diagnosis.

Finally, the informing conference does not end with the presentation of devastating news. Instead, the child’s strengths, appealing behaviors, and potential for development are stressed, as are available rehabilitation efforts or treatment. Parents can be encouraged to view their experiences as a series of challenges that they are capable of handling, particularly with available professional feedback. The parents are assured that the nurse will be available to answer questions and to provide further assistance as needed.

The preceding discussion relates primarily to the initial informing interview. However, because of the need for long-term follow-up, it is only one in a series of continuing discussions. In all interactions the family’s input is solicited and incorporated into the care plan. Some situations require consideration of special problems (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

SUPPORT FAMILY’S COPING METHODS

For the family to meet the stresses of optimally adjusting to the child’s condition, each member must be individually supported so that the family system is strong. Although the family can indefinitely support a member who is in need of assistance, its greatest strength lies in every member supporting each other. The nurse should bear in mind that the family member in greatest need is not necessarily the affected child but may be a parent or sibling who is dealing with stresses that require intervention.

Parents

The nurse can provide support by being attentive to families’ responses to their children. Mothers and fathers need to experience success, joy, and pride in their children to give the support they need. Children, too, require support for their interactions, adjustments, and efforts. They must be reinforced for attempts to get to know their care providers and to communicate their needs to them.

It is important for nurses to examine their attitudes to determine their ability to engage in parent-professional partnerships. An essential characteristic is the belief that parents are equal to professionals and are experts regarding their child (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).

Communication among all family members is encouraged. Parent group sessions can help parents verbalize thoughts and feelings to each other but often do not take into account siblings’ or the child’s viewpoint. Therefore the nurse may need to set up a family session, such as during a home or clinic visit. Although the ideal situation is to have all the members present at one time, often this is not possible. Inviting members to participate at various visits is an appropriate alternative.

Parents can be encouraged to discuss their feelings toward the child, the impact of this event on their marriage, and associated stresses such as financial burdens. For most families, regardless of their income or insurance coverage, financial concerns exist. The costs of caring for a child with special needs can be overwhelming. In addition, the family wage earner may have to sacrifice job opportunities to remain close to a medical facility or to avoid losing insurance benefits.*

The nurse regards fathers as able, effective parents, competent and capable of coping with the challenges they face. Every effort is made to include the father in visits, such as to the nursery, clinic, special school, and stimulation programs. The father is included in the assessment process, with specific emphasis on having him describe the child’s strengths and difficulties. It is not unusual to find two parents who have differing views of the child’s abilities, especially in the area of developmental disabilities.

Numerous volunteer and community resources are available that provide assistance, rehabilitation, equipment, and funding for a variety of health problems.* National and local disease-oriented organizations may provide needed assistance and support to families that qualify. Many of these are discussed elsewhere in the text under the specific diagnosis. State and federal departments of health, mental health, social service, and labor may be able to help locate appropriate regional resources. For example, state programs for Children with Special Health Needs (formerly Crippled Children’s Services) provide financial assistance for children with many disabling conditions. Local and national sources of respite care and medical day care may be useful to families. Nurses should become acquainted with those in their communities and with vocational programs for special groups.

Parent-to-Parent Support

Just being with another parent who has shared similar experiences is helpful. It may not need to be a parent of a child with the same diagnosis, since parents in the process of adjusting to a child with special needs—or finding respite services, educational or rehabilitative services, special equipment vendors, and financial counseling—tread a common path. If the agency does not have a parent staff position, the nurse can contact parent groups that will often send a representative. Another strategy is to ask another parent to talk to the parents. The nurse should seek out a parent who is a good listener, has a nonjudgmental approach to differences in families, and possesses good advocacy and problem-solving skills.

The parent self-help group is another way to promote parent-to-parent support.* Group members feel less alone and have the opportunity to observe both coping and mastery role modeling from other members. Parents’ groups are rich resources for information. Even if parents are unable to attend meetings, they can still benefit from group newsletters and other literature that often accompany membership. The nurse can foster parent participation in self-help groups by serving as a referral agent, a group advisory board member, a resource person, a group member, or an assistant in founding a group. Sometimes all that is required in starting a group is identifying one or two parents as leaders; sharing with them the names, telephone numbers, and addresses of other families who have expressed both an interest and a willingness to release their phone number and address; and guiding them in how to initiate a first meeting.

Advocate for Empowerment

Nurses can advocate for methods that foster opportunities for parent empowerment. For example, nurses can suggest reimbursement for travel and child care, plus stipends to enable parents’ voices to be heard at meetings and conferences. They can encourage parent membership on staff, committees, and boards. They can keep parents informed of pending legislation on child health issues or take action when parents inform them.

The Child

Through ongoing contacts with the child, the nurse (1) observes the child’s responses to the disorder, ability to function, and adaptive behaviors within the environment and with significant others; (2) explores the child’s own understanding of his or her illness or condition; and (3) provides support while the child learns to cope with his or her feelings. Children are encouraged to express their concerns rather than allowing others to express them for them, since open discussions may reduce anxiety.

One of the most important interventions is alleviating the child’s feeling of being different and normalizing his or her life as much as possible (see Nursing Care Guidelines box). Whenever possible, the nurse assists the family in assessing the child’s daily routine for indications of a need for normalizing practices. For example, the child who remains in a bedroom all day requires a restructured daily routine to provide activities in different parts of the house, such as eating in the kitchen or dining room with the family. Such children may also be deprived of social, recreational, and academic activities that can be better accommodated by applying normalization practices. For example, home and out-of-home health-related treatments should be planned at times that least interfere with normal daily activities.

Children who are concerned that their condition detracts from their physical attractiveness need attention focused on the normal aspects of appearance and capabilities. Health professionals help strengthen and consolidate the self-image by emphasizing the normal, while allowing children to express anger, isolation, fear of rejection, feelings of sadness, and loneliness. The children need positive reinforcement for compliance and any evidence of improvement. Anything that might improve attractiveness and contribute to a positive self-image is employed, such as makeup for a teenager with a scar, clothing that disguises a prosthesis, or a hairstyle or wig to cover a deformity or lost hair.

Siblings

The presence of a child with special needs in a family may result in parents paying less attention to the other children. Siblings may respond by developing negative attitudes toward the child or by expressing anger in different forms. The nurse can help by using anticipatory guidance, questioning the parents about what they believe is the best way to have siblings respond to the child and guiding them through ways to meet their other children’s needs for attention. This questioning should take place before serious negative effects occur.

Siblings may also experience embarrassment associated with having a brother or sister with an illness or disability. Parents are then faced with the difficulty of responding to this embarrassment in an understanding and appropriate manner without punishing the siblings for how they feel. Parents are encouraged to talk with the siblings about how they view their affected sibling. For example, siblings of a child who is retarded may express fears about their ability to bear normal children. Adolescents in particular may not be able to discuss these vital issues with their parents and may prefer to consult with the nurse. Many siblings benefit from sharing their concerns with other young people who are experiencing a similar situation. Support groups for siblings can help decrease isolation, promote expression of feelings, and provide examples of effective coping skills.

Many parents express concern about when and how to inform the other children in the family about a sibling’s disability. The answer depends on each child’s level of sophistication and understanding. However, it is usually best to inform the siblings before a neighbor or other nonfamily member does so. Uninformed siblings may fantasize or develop apprehensions that are out of proportion to the child’s actual condition. Furthermore, if parents choose to be silent or deceptive about the issue, they are setting a negative precedent for the siblings to follow, rather than encouraging the siblings to cope with the experience in a healthy and nurturing way.

The nurse is sensitive to the reactions of siblings and whenever possible intervenes to promote more positive adjustment. For example, siblings often mention that they are expected to take on additional responsibilities to help the parents care for the child. It is not unusual for them to express a positive reaction to assuming the extra duties but a negative response to feeling unappreciated for doing so. Such feelings can often be minimized by encouraging siblings to discuss this with the parents and by suggesting to parents ways of showing gratitude, such as an increase in allowance, special privileges, and, most significantly, verbal praise.

EDUCATE ABOUT THE DISORDER AND GENERAL HEALTH CARE

Educating the family about the disorder is actually an extension of revealing the diagnosis. Education involves not only supplying technical information, but also discussing how the condition will affect the child. Parents may be able to digest only so much information at a time. It may be helpful to provide essential information and then follow by asking, “What else would you like to know about your child’s condition?” Responding to parents’ questions and concerns ensures that their information needs are met.

Activities of Daily Living

Parents also need guidance in how the condition may interfere with or alter activities of daily living, such as eating, dressing, sleeping, and toileting. One area frequently affected is nutrition. Common problems are undernutrition resulting from food being inappropriately restricted or loss of appetite, vomiting, or motor deficits that interfere with feeding; overnutrition may also occur, usually because of a caloric intake in excess of energy expenditure or boredom and lack of stimulation in other areas. Although the child requires the same basic nutrients as other children, the daily requirements may differ. Special nutritional considerations are discussed as appropriate throughout the text.

Safe Transportation

Modifications may also be needed regarding car safety. Children with conditions such as low birth weight (see Discharge Planning and Home Care, Chapter 9) or orthopedic, neuromuscular, or respiratory problems often cannot safely use conventional car restraints. For example, children with hip spica casts cannot sit properly in child safety seats (see Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip, Chapter 31). Modifications can be made to some commercial models, and for older children a special vest is available that secures the child to the back seat in a lying-down position.*

If a child requires a wheelchair, the family should consult the wheelchair manufacturer for specific instructions regarding safe car transportation. Considerations for wheelchairs used with vehicle transportation must address securing both the wheelchair and the occupant in the wheelchair. Wheelchairs should be secured facing forward with tie downs at four points. The tie-down system should be dynamically crash tested, as should the occupant securement system that secures the child in the wheelchair. For example, use of trays would not be recommended for transportation. With children who must travel with additional medical equipment, this equipment (e.g., oxygen, monitors, or ventilators) should be anchored to the floor or underneath the vehicle seat or wheelchair. Soft padding should be added around the equipment to reduce movement. A second adult should be present to monitor the condition of a medically fragile child while traveling.

Primary Health Care

Children with special needs require all the usual health care recommended for any child. Attention to injury prevention, immunizations, dental health, and regular physical examinations is essential. Nurses can play an important role in reminding parents of these aspects of care that are so often neglected when the concern is focused on the child’s illness or disability. Specific discussions of nutrition, sleep and activity, dental health, and injury prevention are presented in the chapters on health promotion for specific age-groups. Immunizations are discussed in Chapter 10.

Parents also need to be aware of the importance of communicating the child’s condition in the event of a medical emergency. Young children are unable to give information about their disorder, and although older children may be reliable sources, after an accident they may be physically unable to speak. Therefore all children with any type of chronic condition that may affect medical care should wear some type of identification, such as a MedicAlert bracelet,† or carry a card in their wallet that lists the medical condition and a phone number for emergency medical records and other personal information.

PROMOTE NORMAL DEVELOPMENT

Aside from knowledge of the condition and its effect on the child’s abilities, the family must be guided toward fostering appropriate development in their child. Although each stage may take longer to achieve, parents are guided toward helping the child fully realize his or her potential in preparation for the next developmental stage. Table 18-2 outlines developmental aspects of chronic illness or disability and supportive interventions. With appropriate planning and knowledge of strategies to improve the child’s functional abilities, most children can live fulfilling and productive lives.

One important aspect of promoting normal development is to encourage the child’s self-care abilities in both activities of daily living and the medical regimen. An assessment of the child’s age and physical, emotional, and mental capacities, as well as the support and structure provided by the family, should be considered in determining the appropriate level of self-care in the medical regimen. Even toddlers can be involved in their own care by holding supplies for the parent during a procedure. Over time, children should be encouraged toward greater autonomy in the self-care arena.

Early Childhood

During infancy the child is achieving basic trust through a satisfying, intimate, consistent relationship with his or her parents. However, the affected child’s early existence may be stressful, chaotic, and unsatisfying. Consequently, he or she may need more parental support and expressions of affection to achieve trust. Likewise, the parents require assistance in finding ways to meet the infant’s needs, such as how to hold a rigid or flaccid infant, how to feed a child with tongue thrust or episodes of dyspnea, and how to stimulate a child who seems incapable of achieving any skills. If hospitalizations are frequent or prolonged, every effort is made to preserve the parent-child relationship (see also Chapter 21). Hospital policies should promote visitation by and involvement of families.

During early childhood the goal is to achieve separation from parents, autonomy, and initiative. However, the natural parental response to having a sick child is overprotection. Parents need help in realizing the importance of brief separations of the child from them and from others involved in the child’s care and of providing social experiences outside the home whenever possible. Respite care, which provides temporary relief for family members, can be essential in allowing caregivers time away from the daily burdens.

Young children also need the opportunity to develop independence. Frequently the child is able to learn self-help skills, such as holding the bottle, finger feeding, and removing simple articles of clothing, but the parent continues to perform the act. The nurse can guide parents to the usual milestones expected from the child. When a child is unable to perform a skill independently, functional aids should be used. With innovation, many adaptations can be implemented in children’s environments to increase their mobility and independence and allow them to play like other children their age. For example, with slight modifications, a child with physical limitations may be able to ride a tricycle (Fig. 18-4).

FIG. 18-4 A modified tricycle with block pedals, self-adhesive straps for support, and modified seat and handle bars can help a child with disabilities gain mobility.

Another critical component for normal child development is discipline. Discipline and guidance serve several purposes, such as providing children with boundaries on which to test out their behavior and teaching them socially acceptable behavior. Resentment and hostility can arise among siblings if different standards are applied to each child. The nurse’s responsibility is to help parents learn successful methods of managing a child’s behaviors before they become problems (see Limit Setting and Discipline, Chapter 3).

School Age

For school-age children the major tasks are entry into school and achieving a sense of industry. Although the importance of school in the life of all children is well known, school absences are significantly higher among children with chronic illness than among their healthy peers. The more school absences the child experiences, the more difficult it is to resume attendance, and school phobia may result. The child should return to school as soon as possible after diagnosis or treatments.

Preparation for entry into or resumption of school is best accomplished through a team approach with the parents, child, teacher, school nurse, and primary nurse in the hospital. Ideally, this planning should begin before hospital discharge, provided that the child is well enough to resume usual activities. A structured plan should be developed, with attention to those aspects of care that must be continued during school hours, such as administration of medication or other treatments.

Children also need preparation before entering or resuming school. Having a tutor in the hospital or home as soon as children are physically able helps them realize that school will continue and gives them time to consider this prospect (Fig. 18-5). They need to investigate possible answers to the many questions others will ask. One method of anticipatory preparation is to role-play, with the child as the “returned pupil” and the nurse or parent as “other schoolmates.” If the child returns to school with some obvious physical change, such as hair loss, amputation, or visible scar, the nurse might also ask questions about these alterations to prompt preparatory responses from the child.

FIG. 18-5 Children with special needs should continue their schooling as soon as their condition permits.

Classroom peers also need preparation, and a joint plan of the teacher, nurse, and child is best. At a minimum, classmates should be given a description of the child’s condition, prepared for any visible changes in the child, and allowed an opportunity to ask questions. The child should have the option of attending this session. As the child’s condition changes, particularly if the illness is potentially fatal, school personnel, including the students, need periodic apprisal of the child’s status and preparation for what to expect.

Children with special needs are encouraged to maintain or reestablish relationships with peers and to participate according to their capabilities in any age-appropriate activities. Alternative activities may be substituted for those that are impossible or that place a strain on the child’s condition. Programs such as the Special Olympics*. Several pamphlets on sports and recreation for children with disabilities are available from Easter Seals (see footnote, p. 589) and American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 1900 Association Drive, Reston, VA 20191; (703) 476-3400 or (800) 213-7193; http://www.aahperd.org. offer children an opportunity to compete witheir peers and to achieve athletic skill. Summer camps†. allow children to associate with peers and develop a wide variety of skills. Children with special needs can derive enormous benefits from expressive activities, such as art, music, poetry, dance, and drama. With adaptive equipment and imagination, children can participate in a variety of activities. Organizations such as VSA Arts allow children to celebrate and share their accomplishments.*. Children need the opportunity to interact with healthy peers and to engage in activities with groups or clubs composed of similarly affected age-mates. Such organizations as ostomy clubs, diabetes clubs, and cerebral palsy groups share information and provide support related to the special problems the members face.

Adolescence

Adolescence can be a particularly difficult period for the teenager and family. All of the needs discussed previously apply to this age-group as well. Developing independence or autonomy, however, is a major task for the adolescent as planning for the future becomes a prominent concern. Although the emphasis in the past has been on achieving independence from physical assistance, recent developments in the fields of special education, adolescent development, and family systems suggest redefining autonomy in terms of individuals’ capacities to take responsibility for their own behavior, to make decisions regarding their own lives, and to maintain supportive social relationships. Given this understanding, even individuals with severe impairment can be viewed as autonomous if they perceive their own needs and take responsibility for meeting them, either directly or by engaging the assistance of others. As adolescents become more autonomous, the nurse can help them articulate needs, participate in developing their own care plan, and discover and express how others can be of greatest assistance.