Health Promotion of the Preschooler and Family

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

Identify the major biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, moral, spiritual, and social developments that occur during the preschool years.

Identify the major biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, moral, spiritual, and social developments that occur during the preschool years.

List the benefits of imaginary playmates.

List the benefits of imaginary playmates.

Prepare preschoolers for preschool or daycare experience.

Prepare preschoolers for preschool or daycare experience.

Provide parents with guidelines for sex education.

Provide parents with guidelines for sex education.

Provide parents with guidelines for dealing with a child’s fears, stresses, aggression, and sleep problems.

Provide parents with guidelines for dealing with a child’s fears, stresses, aggression, and sleep problems.

Recognize the causes of stuttering during the preschool years.

Recognize the causes of stuttering during the preschool years.

Offer parents suggestions for preventing speech problems.

Offer parents suggestions for preventing speech problems.

Recognize feeding patterns of preschoolers.

Recognize feeding patterns of preschoolers.

Provide anticipatory guidance to parents regarding injury prevention based on the preschooler’s developmental achievements.

Provide anticipatory guidance to parents regarding injury prevention based on the preschooler’s developmental achievements.

PROMOTING OPTIMAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

The combined biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, spiritual, and social achievements during the preschool period (3 to 5 years of age) prepare preschoolers for their most significant change in lifestyle: entrance into school. Their control of bodily functions, experience of brief and prolonged periods of separation, ability to interact cooperatively with other children and adults, use of language for mental symbolization, and increased attention span and memory prepare them for the next major period: the school years. Successful achievement of previous levels of growth and development is essential for preschoolers to refine many of the tasks that were mastered during the toddler years.

BIOLOGIC DEVELOPMENT

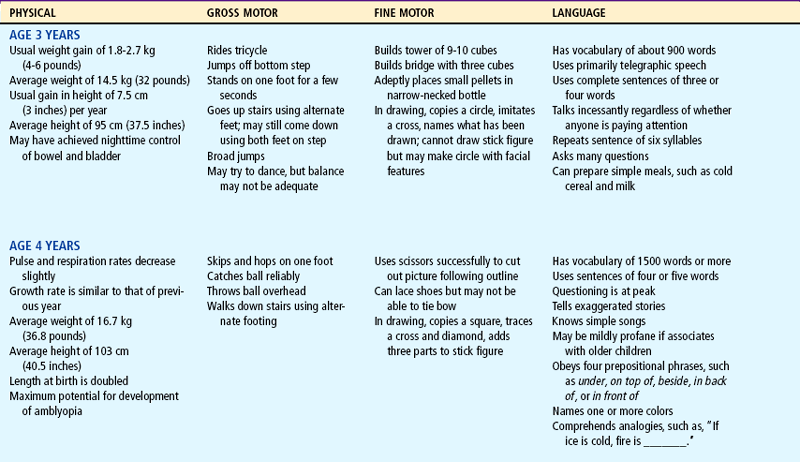

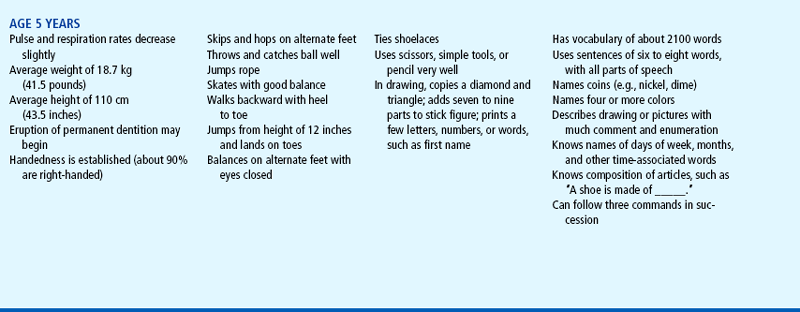

The rate of physical growth slows and stabilizes during the preschool years. The average weight is 14.5 kg (32 pounds) at 3 years, 16.7 kg (36.8 pounds) at 4 years, and 18.7 kg (41.5 pounds) at 5 years. The average weight gain per year remains approximately 2 to 3 kg (4.5 to 6.5 pounds).

Growth in height also remains steady, with a yearly increase of 6.5 to 9 cm (2.5 to 3.5 inches), and generally occurs by elongation of the legs rather than of the trunk. The average height is 95 cm (37.5 inches) at 3 years, 103 cm (40.5 inches) at 4 years, and 110 cm (43.5 inches) at 5 years.

Physical proportions no longer resemble those of the squat, pot-bellied toddler. The preschooler is slender but sturdy, graceful, agile, and posturally erect. There is little difference in physical characteristics according to gender, except as dictated by such factors as dress and hairstyle.

Most organ systems can adjust to moderate stress and change. During this period, most children are toilet trained. For the most part, motor development consists of increases in strength and refinement of previously learned skills, such as walking, running, and jumping. However, muscle development and bone growth are still far from mature. Excessive activity and overexertion can injure delicate tissues. Good posture, appropriate exercise, and adequate nutrition and rest are essential for optimal development of the musculoskeletal system.

Gross and Fine Motor Skills

Walking, running, climbing, and jumping are well established by age 36 months. Refinement in eye-hand and muscle coordination is evident in several areas. At age 3, the preschooler rides a tricycle, walks on tiptoe, balances on one foot for a few seconds, and broad jumps. By age 4, the child skips and hops proficiently on one foot (Fig. 13-1) and catches a ball reliably. By age 5, the child skips on alternate feet, jumps rope, and begins to skate and swim.

Fine motor development is evident in the child’s increasingly skillful manipulation, such as in drawing and dressing. These skills provide readiness for learning and independence for entry into school.

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Developing a Sense of Initiative (Erikson)

After preschoolers have mastered the tasks of the toddler period, they are ready to face the developmental endeavors of the preschool period. Erikson maintained that the chief psychosocial task of this period is acquiring a sense of initiative. Children are in a stage of energetic learning. They play, work, and live to the fullest and feel a real sense of accomplishment and satisfaction in their activities. Conflict arises when children overstep the limits of their ability and inquiry and experience a sense of guilt for not having behaved appropriately. Feelings of guilt, anxiety, and fear may also result from thoughts that differ from expected behavior.

A particularly stressful thought is wishing one’s parent dead. As a sense of rivalry or competition develops between the child and same-sex parent, the child may think of ways to get rid of the interfering parent. In most situations, this rivalry is resolved when the child strongly identifies with the same-sex parent and peers during the school years. However, if that parent dies before the identification process is completed, the preschooler may be overwhelmed with feelings of guilt for having wished and therefore “caused” the death. Clarifying for children that wishes cannot and do not make events occur is essential in helping them overcome their guilt and anxiety.

Development of the superego, or conscience, begins toward the end of the toddler years and is a major task for preschoolers (see Cultural Awareness box). Learning right from wrong and good from bad is the beginning of morality (see Moral Development).

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

One of the tasks related to the preschool period is readiness for school and scholastic learning. Many of the thought processes of this period are crucial for achieving such readiness, and it is intentional that the child begins school between ages 5 and 6 rather than at an earlier age.

Preoperational Phase (Piaget)

Piaget’s cognitive theory does not include a period specifically for children who are 3 to 5 years old. The preoperational phase covers the age span from 2 to 7 years and is divided into two stages: the preconceptual phase, ages 2 to 4, and the phase of intuitive thought, ages 4 to 7. One of the main transitions during these two phases is the shift from totally egocentric thought to social awareness and the ability to consider other viewpoints. However, egocentricity is still evident. (For a review of the characteristics of preoperational thought, see Chapter 12.)

Language continues to develop during the preschool period. Speech remains primarily a vehicle of egocentric communication. Preschoolers assume that everyone thinks as they do and that a brief explanation of their thinking makes the entire thought understood by others. Because of this self-referenced, egocentric verbal communication, it is often necessary to explore and understand the young child’s thinking through other, nonverbal approaches. For children in this age-group, the most enlightening and effective method is play, which becomes the child’s way of understanding, adjusting to, and working out life’s experiences.

Preschoolers increasingly use language without comprehending the meaning of words, particularly concepts of right and left, causality, and time. Children may use the concepts correctly but only in the circumstances in which they have learned them. For example, they may know how to put on shoes by remembering that the buckle is always on the outside of the foot. However, if different shoes have no buckles, they cannot reason which shoe fits which foot. In other words, they do not understand the concept of right and left.

Superficially, causality resembles logical thought. Preschoolers explain a concept as they heard it described by others, but their understanding is limited. An example is the concept of time. Because time is still incompletely understood, the child interprets it according to his or her own frame of reference, such as “A long time means until Christmas.” Consequently, time is best explained in relationship to an event, such as “Your mother will visit you after you finish your lunch.” Avoiding words such as yesterday, tomorrow, next week, or Tuesday to express when an event is expected to occur and instead associating time with expected daily events help children learn about temporal relationships while increasing their trust in others’ predictions.

Preschoolers’ thinking is often described as magical thinking. Because of their egocentrism and transductive reasoning, they believe that thoughts are all-powerful. Such thinking places them in the vulnerable position of feeling guilty and responsible for bad thoughts, which may coincide with the occurrence of a wished event. Their inability to logically reason the cause and effect of illness or an injury makes it especially difficult for them to understand such events.

Preschoolers believe in the power of words and accept their meaning literally. An example of this type of thinking is calling children “bad” because they did something wrong. In the preschooler’s mind, calling them bad means they are a bad person; thus it is better to say that their actions were bad by saying, for example, “That was a bad thing to do.”

MORAL DEVELOPMENT

Preconventional or Premoral Level (Kohlberg)

Young children’s development of moral judgment is at the most basic level. They have little, if any, concern about why something is wrong. They behave because of the freedom or restriction that is placed on actions. In the punishment and obedience orientation, children (ages about 2 to 4 years) judge whether an action is good or bad depending on whether it results in reward or punishment. If children are punished for it, the action is bad. If they are not punished, the action is good, regardless of the meaning of the act. For example, if parents allow hitting, the child will perceive that hitting is good because it is not associated with punishment.

From approximately 4 to 7 years of age, children are in the stage of naive instrumental orientation, in which actions are directed toward satisfying their needs and, less frequently, the needs of others. They have a concrete sense of justice and fairness during this period of development.

SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT

Children’s knowledge of faith and religion is learned from significant others in their environment, usually from parents and their religious beliefs and practices (Fosarelli, 2003). However, young children’s understanding of spirituality is influenced by their cognitive level. Preschoolers have a concrete concept of a God with physical characteristics, often like an imaginary friend. They understand simple Bible stories and memorize short prayers, but their understanding of the meaning of these rituals is limited. Preschoolers benefit from concrete representations of religious practices, such as picture Bible books and small statues, such as those of the Nativity scene. They will imitate the religious practices of their parents without fully understanding the significance of these acts.

Development of the conscience is strongly linked to spiritual development. At this age, children are learning right from wrong and behaving correctly to avoid punishment. Wrongdoing provokes feelings of guilt, and preschoolers often misinterpret illness as a punishment for real or imagined transgressions. It is important that children view God as one who bestows unconditional love, rather than as a judge of good or bad behavior. Observing religious traditions and participating in a religious community can help children cope during stressful periods, such as illness, hospitalization, and other traumatic events (Barnes, Plotnikoff, Fox, and others, 2000). In many religious faiths, cultural practices and religion are closely intertwined (McEvoy, 2003) and are an important part of the child’s and family’s life (see Box 4-2).

DEVELOPMENT OF BODY IMAGE

The preschool years play a significant role in the development of body image. With increasing comprehension of language, preschoolers recognize that individuals have undesirable and desirable appearances. They recognize differences in skin color and racial identity and are vulnerable to learning prejudices and biases. They are aware of the meaning of words such as pretty or ugly, and they reflect the opinions of others regarding their own appearance. By 5 years of age, children compare their size with that of their peers and can become conscious of being large or short, especially if others refer to them as “so big” or “so little” for their age. In one study, negative associations between weight status and self-concept were identified in girls as young as 5 years of age (Davison and Birch, 2001).

Despite the advances in body image development, preschoolers have poorly defined body boundaries and little knowledge of their internal anatomy. Intrusive experiences are frightening, especially those that disrupt the integrity of the skin, such as injections and surgery. They fear that if their skin is “broken,” all of their blood and “insides” can leak out. Therefore bandages are critical to “keep everything from coming out.”

DEVELOPMENT OF SEXUALITY

Sexual development during these years is an important phase in a person’s overall sexual identity and beliefs. Preschoolers are forming strong attachments to the opposite-sex parent while identifying with the same-sex parent. Sex-typing, or the process by which an individual develops the behavior, personality, attitudes, and beliefs appropriate for his or her culture and sex, occurs through several mechanisms during this period. Probably the most powerful mechanisms are childrearing practices and imitations. Gender identification is a result of complex prenatal and postnatal psychologic factors, as well as biologic or genetic factors, and that most children are aware of their gender and the expected sets of related behaviors by 1½ to 2½ years of age.

As sexual identity develops beyond gender recognition, modesty may become a concern. Sex-role imitation and “dressing up” like Mommy or Daddy are important activities. Attitudes and responses of others to role-playing can condition the child to views of self or others. For example, comments such as “Boys shouldn’t play with dolls” can influence a boy’s self-concept of masculinity.

Sexual exploration may be more pronounced now than ever before, particularly in terms of exploring and manipulating the genitalia. Questions about sexual reproduction may come to the forefront in the preschooler’s search for understanding (see Sex Education, p. 443, and in Chapter 15).

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

During the preschool period, the separation-individuation process is completed. Preschoolers have overcome much of the anxiety associated with strangers and the fear of separation of earlier years. They relate to unfamiliar people easily and tolerate brief separations from parents with little or no protest. However, they still need parental security, reassurance, guidance, and approval, especially when entering preschool or elementary school. Prolonged separation, such as that imposed by illness and hospitalization, is difficult, but preschoolers respond to anticipatory preparation and concrete explanation. They can cope with changes in daily routine much better than toddlers, although they may develop more imaginary fears. Preschoolers gain security and comfort from familiar objects, such as toys, dolls, or photographs of family members. They are able to work through many of their unresolved fears, fantasies, and anxieties through play, especially if guided with appropriate play objects (e.g., dolls, puppets) that represent family members, health care professionals, and other children.

Language

During the preschool years, language becomes more sophisticated and complex. Both cognitive ability and environment—particularly, consistent role models—influence vocabulary, speech, and comprehension. Language becomes a major mode of communication and social interaction, and its development during the preschool period sets the stage for later success in school (Needlman, 2004) (Fig. 13-2). Vocabulary increases dramatically, from 300 words at age 2 to more than 2100 words at the end of 5 years. Sentence structure, grammatical usage, and intelligibility also advance to a more adult level. Through language, preschool children learn to express feelings of frustration or anger without acting them out.

Children between the ages of 3 and 4 years form sentences of about three or four words and include only the most essential words to convey a meaning. Such speech is often termed telegraphic for its brevity. Three-year-old children ask many questions and use plurals, correct pronouns, and the past tense of verbs. They name familiar objects, such as animals, parts of the body, relatives, and friends. They can give and follow simple commands. They talk incessantly, regardless of whether anyone is listening or answering them. They enjoy musical or talking toys or dolls and imitate new words proficiently.

From ages 4 to 5 years, preschoolers use longer sentences of four or five words and use more words to convey a message, such as prepositions, adjectives, and a variety of verbs. They follow simple directional commands, such as “Put the ball on the chair,” but can carry out only one request at a time. They answer questions such as “What do you do when you are hungry?” by describing the appropriate action. The pattern of asking questions is at its peak, and children will usually repeat a question until they receive an answer.

By age 6, children can use all parts of speech correctly, except for deviations from the rule. They can define simple things by describing their use, shape, or general category of classification, rather than simply describing their outward appearance. For example, they define a ball as “round,” “something you bounce,” or “a toy,” rather than only describing its color. They can give some opposites, such as “If Mommy is a woman, Daddy is a man.” They can also describe an object according to its composition, such as “A spoon is made of metal.”

Personal-Social Behavior

The pervasive ritualism and negativism of toddlerhood gradually diminish during the preschool years. Although self-assertion is still a major theme, preschoolers demonstrate their sense of autonomy differently. They are able to verbalize their request for independence and perform independently because of their much-refined physical and cognitive development. By 4 or 5 years of age, they need little if any assistance with dressing, eating, or toileting (Fig. 13-3). They can also be trusted to obey warnings of danger, although 3- or 4-year-old children may exceed their boundaries at times.

FIG. 13-3 Most preschoolers are able to dress themselves but need help with more difficult items of clothing.

They are also much more sociable and willing to please. They have internalized many of the standards and values of the family and culture. However, by the end of early childhood they begin to question parental values and compare them with those of their peer group and other authority figures. As a result, they may be less willing to abide by the family’s code of conduct. Preschoolers become increasingly aware of their position and role within the family. Although this is a more secure age for experiencing the addition of another sibling, relinquishing the position of only or youngest is still difficult and requires special parental attention to prevent feelings of desertion and resentment (Brazelton and Sparrow, 2001) (see Sibling Rivalry, Chapter 12).

Play

Various types of play are typical of this period, but preschoolers especially enjoy associative play—group play in similar or identical activities but without rigid organization or rules. Play should provide for physical, social, and mental development.

Play activities for physical growth and refinement of motor skills include jumping, running, and climbing. Tricycles, wagons, gym and sports equipment, sandboxes, wading pools, and activities at water parks can help develop muscles and coordination (Fig. 13-4). Activities such as swimming and skating teach safety as well as muscle development and coordination. Children involved in the work of play do not require expensive toys and gadgets to keep them entertained but often enjoy playing with common household items such as a broom handle or even items adults consider junk (boxes, sticks, rocks, and dirt). The imaginative mind of the preschooler enjoys playing for play’s sake.

FIG. 13-4 Preschoolers enjoy play activities that promote motor skills such as jumping and running. Water play is an exciting activity for preschoolers.

Manipulative, constructive, creative, and educational toys provide for quiet activities, fine motor development, and self-expression. Easy construction sets, large blocks of various sizes and shapes, a counting frame, alphabet or number flash cards, paints, crayons, simple carpentry tools, musical toys, illustrated books, simple sewing or handicraft sets, large puzzles, and clay are suitable toys. Electronic games and computer programs are especially valuable in helping children learn basic skills, such as letters and simple words.

Probably the most characteristic and pervasive preschool activity is imitative, imaginative, and dramatic play. Dress-up clothes, dolls, housekeeping toys, dollhouses, play store toys, telephones, farm animals and equipment, village sets, trains, trucks, cars, planes, hand puppets, and medical kits provide hours of self-expression (Fig. 13-5). Probably at no other time is the reproduction of adult behavior so faithful and absorbing as in 4- and 5-year-old children. Toward the end of the preschool period, children are less satisfied with make-believe or pretend objects and enjoy doing the actual activity, such as cooking and carpentry.

Television and videos also have their place in children’s play, although each should be only one part of children’s total repertoire of social and recreational activities. Parents and other caregivers should supervise the selection of programs, watch and discuss programs with their children, schedule limited time for television viewing, and set a good example of television viewing (Yalçin, Türul, Naçar, and others, 2002; American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001a). Children also enjoy and learn from educational programs; however, television viewing may limit time spent in other meaningful activities such as reading, physical activity, and socialization (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001a).

Television can become an interactive activity when adults view programs with children and discuss program content. In one study, viewing educational programs as preschoolers was associated with higher grades, more book reading, greater emphasis on achievement, increased creativity, and less aggression in adolescent years (Anderson, Huston, Schmitt, and others, 2001). The researchers emphasize that the content of television viewing appeared more important than the amount viewed.

Play is so much a part of the young child’s life that reality and fantasy become blurred. Make-believe is reality during play and only becomes fantasy when the toys are put away or the dress-up clothes are removed. It is no wonder that imaginary playmates are so much a part of this age period. The appearance of imaginary companions usually occurs between ages 2½ and 3 years, and for the most part, such playmates are relinquished when the child enters school. The birth order and number of siblings may influence the creation of imaginary companions, with firstborn and only children being more likely to create imaginary playmates (Gleason, Sebanc, and Hartup, 2000).

Imaginary companions serve many purposes: they become friends in times of loneliness, they accomplish what the child is still attempting, and they experience what the child wants to forget or remember. It is not unusual for the “friend” to have myriad vices and to be blamed for wrongdoing. Sometimes the child hopes to escape punishment by saying, “My friend George broke the glass.” At other times, the child may fantasize that the companion misbehaved and play the role of the parent. This becomes a way of assuming control and authority in a safe situation.

Parents often worry about the imaginary playmates, not realizing how normal and useful they are. Parents need to be reassured that the child’s fantasy is a sign of health that helps differentiate make-believe and reality. Parents can acknowledge the presence of the imaginary companion by calling him or her by name and even agreeing to simple requests such as setting an extra place at the table, but they should not allow the child to use the playmate to avoid punishment or responsibility. For example, if the child blames the companion for messing up a room, parents need to state clearly that the child is the only one they see; therefore the child is responsible for cleaning up.

Children also benefit from play that occurs between them and a parent. Mutual play fosters development from birth through the school years and provides enriched opportunities for learning. Through mutual play, parents can provide tactile and kinesthetic experiences, can maximize verbal and language abilities, and can offer praise and encouragement for exploration of the world. In addition, mutual play encourages positive interactions between the parent and child, strengthening their relationship.*

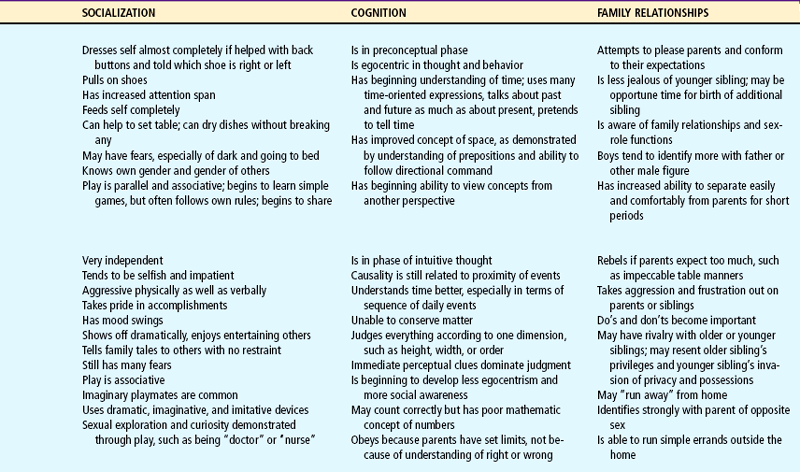

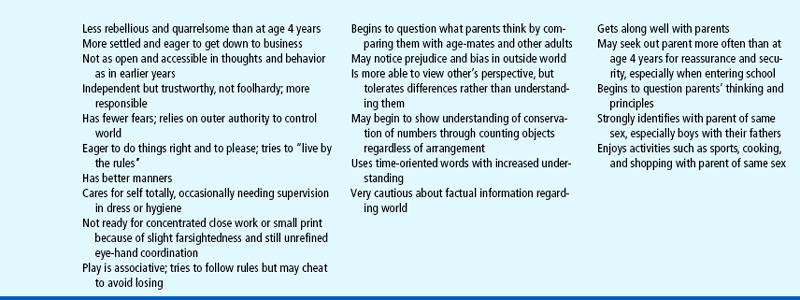

Table 13-1 summarizes the major developmental achievements for children 3, 4, and 5 years of age.

COPING WITH CONCERNS RELATED TO NORMAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

Preschool and Kindergarten Experience

Some children are home schooled, but many children attend some type of early childhood program, usually preschool or a daycare center. Group care has become commonplace with the large number of parents currently employed outside the home (see Alternate Child Care Arrangements, Chapter 10). The effects of early education and stimulation on children have increasingly gained recognition. (For a discussion of the effects of daycare on young children, see Working Mothers, Chapter 3.) Because social development widens to include age-mates and other significant adults, preschool provides an excellent vehicle for expanding children’s experiences with others. It is also excellent preparation for entrance into elementary school.

In preschool or daycare centers, children are exposed to opportunities for learning group cooperation; adjusting to sociocultural differences; and coping with frustration, dissatisfaction, and anger. If activities are tailored to provide mastery and achievement, children increasingly have feelings of success, self-confidence, and personal competence. Whether structured learning is imposed is less important than the social climate, type of guidance, and attitude toward the children that is fostered by the teacher or leader. With a teacher who is aware of preschoolers’ developmental abilities and needs, children will learn from the activity that is provided. Most programs incorporate a daily schedule of quiet play, active outdoor activity, group activities such as games and projects, creative or free play, and snack and rest periods. Preschool is particularly beneficial for children who lack a peer-group experience, such as an only child, and for children from impoverished homes.

One of the issues that parents face is the child’s readiness for preschool or kindergarten. There are no absolute indicators for school readiness, but the child’s social maturity, especially attention span, is as important as his or her academic readiness. Using a developmental screening tool that addresses cognitive (especially language), social, and physical milestones can identify children who may benefit from diagnostic testing and early intervention programs before starting school. Parents play an integral role in their children’s school readiness. They should promote a positive attitude toward learning, read to their children, encourage their children to participate in a variety of activities to explore their talents, and choose appropriate child care or preschool programs (Jellinek, Patel, and Froehle, 2002).

Nurses and other health care workers can guide parents in selecting enriched social and educational early intervention programs, schools, and child care centers. Careful selection of early childhood education is intrinsic to future learning and development. Licensed and regulated programs are mandated to abide by established standards, which represent minimum requirements and safeguards. Regulation is important to protect children from harm and to promote the conditions essential for a child’s healthy development and learning. The National Association for the Education of Young Children serves as the model for optimal care of small children.*

Areas for parents to evaluate include the facility’s daily program, teacher qualifications, staff-to-student ratio, discipline policy, environmental safety precautions, provision of meals, sanitary conditions, adequate indoor and outdoor space per child, and fee schedule. References from other parents help in evaluating a facility, but personal observation of the facility is recommended. Encourage parents to meet the director and some of the employees at a few facilities to make an informed choice.

Evaluation of the facility’s health practices is extremely important. Children in daycare centers have more illnesses than children not in daycare centers, especially gastrointestinal tract infections; respiratory tract infections; and hepatitis A, varicella-zoster virus, and cytomegalovirus infections (Rafanello, 2001). Nurses play an important role in infection control. Not only can they advise parents regarding the evaluation of a facility’s sanitary practices, but they can also take an active part in educating staff in measures to minimize transmission of infection (Fig. 13-6).

Children need preparation for the preschool or kindergarten experience. For young children it represents a change from their usual home environment and prolonged separation from parents. Before children begin school, parents should present the idea as exciting and pleasurable. Talking to children about activities such as painting, building with blocks, or enjoying swings and other outdoor equipment allows children to fantasize about the forthcoming event in a positive manner. When the first day of school arrives, parents should behave confidently. Such behavior requires parents to have resolved their own feelings regarding the experience.

Parents should introduce their child to the teacher and the facility. In some instances, it is helpful for parents to remain with the child for at least part of the first day until the child is comfortable and at ease. Other specific actions that can help reduce separation anxiety include providing the school with detailed information about the child’s home environment, such as familiar routines, favorite activities, food preferences, names of siblings or pets, and personal habits. Such information helps the child feel familiar in the strange surroundings. When schools automatically request this information, the parent has a valuable clue to evaluating the quality of the program because the request represents the staff’s awareness of each child’s needs. Transitional objects, such as a favorite toy, may also help the child bridge the gap from home to school.

Sex Education

Preschoolers have assimilated a tremendous amount of information during their short lifetimes. Although their thinking may not be mature, they search constantly for explanations and reasons that are logical and reasonable to them. The word “why” seems to supplant the word “no,” which was common in toddlerhood. It is only natural that as they learn about “me,” they will also want to know “why me” and “how me.” Questions such as “Where do babies come from?” are as casual as “What makes it rain?” or “Who is that?” It is the way in which questions about procreation are answered that conditions children, even the youngest, to separate these questions from others about their world.

Two rules govern answering sensitive questions about topics such as sex. The first is to find out what children know and think. By investigating the theories children have produced as a reasonable explanation, parents can not only give correct information, but also help children understand why their explanation is inaccurate. Another reason for ascertaining what the child thinks before offering any information is that the “unasked for” answer may be given. For example, 4-year-old Sally asked her father, “Where did I come from?” Both parents quickly took this inquiry as a clue for offering sex education. After the explanation, Sally exclaimed, “I don’t know about all that! All I know is Mary came from New York, and I want to know where I was born.”

The second rule for giving information is to be honest. It is true that much of the correct information will be forgotten or misunderstood by the preschooler, but the correct information can be restated until the child absorbs and comprehends the facts. Even though the correct anatomic words may be hard to pronounce or even more difficult to remember, they become foundational content for explaining other concepts later on.

Honesty does not imply imparting to children every fact of life or allowing excessive permissiveness in sexual curiosity. When children ask one question, they are looking for one answer. When they are ready, they will ask about the other “unfinished” parts of the story. Sooner or later they will wonder how the “sperm meets the egg” and “ how the baby gets out,” but during this period, it is best to wait until they ask.

Regardless of whether children are given sex education, they will engage in games of sexual curiosity and exploration. At about 3 years of age, children are aware of the anatomic differences between the sexes and are concerned with how the other “works.” This is not really “sexual” curiosity because many children are still unaware of the reproductive function of the genitalia. Their curiosity is for the eliminative function of the anatomy. Little boys wonder how girls can urinate without a penis, so they watch girls go to the bathroom. Because they cannot see anything but the stream of urine coming out, they want to observe further. “Doctor play” is often a game invented for just such investigation. Little girls are no less curious about boys’ anatomy. It is intriguing to closely inspect this “thing” that girls do not have.

One question that parents often have is how to handle such sexual curiosity. A positive approach is to neither condone nor condemn the sexual curiosity but to express that if children have questions, they should ask the parents; the parents should then encourage them to engage in some other activity. In this way, children can be helped to understand that there are ways that their sexual curiosity can be satisfied other than through playing investigative games. This in no way condemns the act but stresses alternate methods to seek solutions and answers. Allowing children unrestricted permissiveness only intensifies their anxiety and concern, since exploring and searching usually yield little evidence to satisfy their curiosity.

Many excellent books on sex education are available for preschool children at public libraries. The Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States,* local chapters of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America,† and the American Academy of Pediatrics‡ have bibliographies of suggested reading material. Parents should read the book themselves before giving or reading it to a child.

Another concern for some parents is masturbation, or self-stimulation of the genitalia. This occurs at any age for a variety of reasons and, if not excessive, is normal and healthy. It is most common at 4 years of age and during adolescence. For preschoolers, it is a part of sexual curiosity and exploration. If parents are concerned about their children masturbating, it is essential for nurses to investigate the circumstances associated with the activity because it may be an expression of anxiety, boredom, or unresolved conflicts. Children who openly and publicly masturbate are inviting a reaction, such as discipline, punishment, or criticism. They may be overwhelmed by their sexual feelings and are asking others to help them channel them into more constructive outlets. Masturbation, like other forms of sex play, is a private act, and parents should emphasize this to children when teaching them socially acceptable behavior.

Fears

A great number and variety of real and imagined fears are present during the preschool years, including fear of the dark, being left alone (especially at bedtime), animals (particularly large dogs), ghosts, sexual matters (castration), and objects or persons associated with pain. The exact cause of children’s fears is unknown. Parents often become perplexed about handling the fears because no amount of logical persuasion, coercion, or ridicule will send away the ghosts, boogeymen, monsters, and devils. Inappropriate television viewing by preschoolers may increase fears and anxieties because of the inability to separate reality-based experiences from fantasy portrayed on television.

The concept of animism, ascribing lifelike qualities to inanimate objects, helps explain why children fear objects. For example, a child may refuse to use the toilet after watching a television commercial in which the toilet bowel is portrayed as turning into a monster and swallowing a child.

Preschoolers also experience fear of annihilation. Because of poorly defined body boundaries and improved cognitive abilities, young children develop concerns related to loss of body parts. They fear losing body parts with certain medical procedures such as an intravenous insertion or cast application on a limb and may see these procedures as real threats to their existence.

The best way to help children overcome their fears is by actively involving them in finding practical methods to deal with the frightening experience. This may be as simple as keeping a night-light on in the child’s bedroom for assurance that no monsters lurk in the dark. Exposing children to the feared object in a safe situation also provides a type of conditioning, or desensitization. For instance, children who are afraid of dogs should never be forced to approach or touch one, but they may be gradually introduced to the experience by watching other children play with the animal. This type of modeling, with others demonstrating fearlessness, can be effective if the child is allowed to progress at his or her own rate.

Usually by 5 or 6 years of age, children relinquish many of their fears. Explaining the developmental sequence of fears and their gradual disappearance may help parents feel more secure in handling preschoolers’ fears. Sometimes fears do not subside with simple measures or developmental maturation. When children experience severe fears that disrupt family life, professional help is required.

Stress

Although for parents the preschool years generally are less troublesome than toddlerhood, this period of life presents children with many unique stresses. Some, such as fears, are innate and stem from preschoolers’ unique understanding of the world. Others are imposed, such as beginning school. Although minimal amounts of stress are beneficial during the early years to help children develop effective coping skills, excessive stress is harmful. Young children are especially vulnerable because of their limited capacity to cope. Expression of frustration, fear, or anxiety is hampered by inadequate expressive language.

To help parents deal with stress in their child’s life, they must be aware of signs of stress (see Stress in Childhood, Chapter 5) and be helped to identify the source. Any number of stressors may be present, such as the birth of a sibling, marital discord, divorce and separation, relocation, or illness.

The best approach to dealing with stress is prevention—monitoring the amount of stress in children’s lives so that levels do not exceed their coping ability. In many instances, structuring children’s schedules to allow rest and preparing them for change, such as entering school, are sufficient measures.

Aggression

The term aggression refers to behavior that attempts to hurt a person or destroy property. Aggression differs from anger, which is a temporary emotional state, but anger may be expressed through aggression. Hyperaggressive behavior in preschoolers is characterized by unprovoked physical attacks on other children and adults, destruction of others’ property, frequent intense temper tantrums, extreme impulsivity, disrespect, and noncompliance. Aggression is influenced by a complex set of biologic, sociocultural, and familial variables. Factors that tend to increase aggressive behavior are gender, frustration, modeling, and reinforcement.

Evidence indicates that gender differences exist and that boys are more aggressive than girls (Bendersky, Bennett, and Lewis, 2006). Frustration, or the continual thwarting of self-satisfaction by disapproval, humiliation, punishment, or insults, can lead children to act out against others as a means of release. Especially if they fear their parents, these children will displace their anger on others, particularly peers and other authority figures. This type of aggression often applies to the child who is well behaved at home but a discipline problem at school or a bully among playmates.

Modeling, or imitating the behavior of significant others, is a powerful influencing force in preschoolers. Children who see their parents as physically abusive are observing behavior that they come to know as acceptable and therefore may exhibit this behavior with others (Gershoff, 2002). Another aspect of modeling is the “double standard” for acceptable conduct. For example, in some families, aggression is synonymous with masculinity, and boys are encouraged to defend themselves. Television is also a significant source for modeling at this age. Numerous studies have found a positive correlation between viewing violent programs and developing aggression; therefore parents need encouragement to supervise programs viewed by their preschool children, especially those with aggressive tendencies (Brown and Hamilton-Giachritsis, 2005). The American Academy of Pediatrics (2001a) offers a list of recommendations for healthy television viewing.

Reinforcement can also shape aggressive behavior. Sometimes the reward for aggression is negative (e.g., punishment), yet reinforcing because it brings attention. For example, children who are ignored by a parent until they hit a sibling or the parent learn that this act garners attention.

When children exhibit extreme behaviors, such as aggression, parents may be concerned about the need for professional help. Generally, the difference between “normal” and “problematic” behavior is not the behavior itself but its quantity (number of occurrences), severity (interference with social or cognitive functioning), distribution (different manifestations), onset (when behavior started), and duration (at least 4 weeks).*

Speech Problems

The most critical period for speech development occurs between 2 and 4 years of age. During this period, children are using their rapidly growing vocabulary faster than they can produce the words. Failure to master sensorimotor integrations results in stuttering or stammering as children try to say the word they are already thinking about. This dysfluency in speech pattern is a normal characteristic of language development in children ages 2 to 5 years, affects boys more frequently, and usually resolves during childhood (National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, 2002). When parents or other significant persons place undue emphasis on a child’s dysfluency, an abnormal speech pattern may develop. The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (2002) encourages parents and caregivers of children who stutter to speak slowly and clearly, refrain from correcting or criticizing the child’s speech, resist completing the child’s sentences, and take time to listen attentively.

The best therapy for speech problems is prevention and early detection. Common causes of speech problems are hearing loss, developmental delay, autism, and lack of verbal or psychosocial stimulation (Feldman, 2005). Referral for further evaluation and treatment may be necessary to prevent a problem from interfering with learning. Anticipatory preparation of parents for expected developmental norms may allay caregiver concerns.

Children pressured into producing sounds ahead of their developmental level may develop dyslalia (articulation problems) or revert to using infantile speech. Prevention involves educating parents regarding the usual achievement of speech production during childhood. The Denver Articulation Screening Exam is an excellent tool for assessing articulation skills in the child and for explaining to parents the expected progression of sounds (see Appendix A).

PROMOTING OPTIMAL HEALTH DURING THE PRESCHOOL YEARS*

Nutritional requirements for preschoolers are fairly similar to those for toddlers (Story, Holt, and Sofka, 2002). The requirement for calories per unit of body weight continues to decrease slightly to 90 kcal/kg, for an average daily intake of 1800 calories. Fluid requirements may also decrease slightly to approximately 100 ml/kg/day but depend on the activity level, climatic conditions, and state of health. Protein requirements increase with age, and the recommended intake for preschoolers is 13 to 19 g/day (0.45 to 0.67 oz/day) (Food and Nutrition Board, 2003).

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends the following fat intake levels for children over the age of 2 years: saturated fatty acid consumption should be less than 10% of total caloric intake, and total fat over several days should be no more than 30% and no less than 20% of total caloric intake (Kleinman, 2004). Evidence is increasing that the incidence of coronary heart disease, obesity, and chronic health problems such as diabetes mellitus can be influenced by early eating patterns (Barlow and Expert Committee, 2007). Research supports the efficacy of limiting fat intake, and negative health effects have not been reported (Johnson, 2000). Preschoolers may have a decreased fat intake with substitutes such as soy-enriched foods without affecting overall food taste, energy, and nutrient value (Endres, Barter, Theodora, and others, 2003 ). Parents and others who provide soy substitutes should ensure that the products are vitamin enriched and low in fat content (Endres, Barter, Theodora, and others, 2003).

It is important that all diets contain adequate nutrients such as calcium. The recommendation for daily calcium intake for children 1 to 3 years of age is 500 mg, and the recommendation for children 4 to 8 years of age is 800 mg (Food and Nutrition Board, 2003). Milk and dairy products are excellent sources of calcium and vitamin D (fortified). Low-fat milk may be substituted so the quantity of milk may remain the same while limiting fat intake overall.

Excessive consumption of fruit juices has been associated with adverse health effects such as dental caries and gastrointestinal symptoms; therefore the American Academy of Pediatrics (2001c) recommends limiting the intake of fruit juice to 4 to 6 oz/day for children ages 1 to 6 years. Parents should be educated regarding nonnutritious fruit drinks, which usually contain less than 10% fruit juice, yet are often advertised as healthy and nutritious; sugar content is dramatically increased and often precludes an adequate intake of milk by the child. While counseling parents regarding moderation in fruit juice consumption, providers should offer suggestions for more appropriate sources of nutrients such as ascorbic acid, folate, and potassium. In young children, intake of carbonated beverages that are acidic or that contain high amounts of sugar is also known to contribute to dental caries; large amounts of nonnutritive calories in such beverages may also displace or preclude intake of nutrients necessary for growth.

MyPyramid for Kids is appropriate for preschoolers (see Chapter 6 and Fig. 11-1). This new system is comprehensive and applicable to children as young as 2 years of age. The foods depicted are those commonly eaten by children in this age-group, and the illustrations emphasize the importance of physical activity. Parents and caregivers can provide opportunities for children to learn to like a variety of nutritious foods by exposing them to these foods. The importance of role-modeling by parents cannot be overemphasized in regard to food intake and dietary habits; if the parent will not eat a particular food or if their dietary habits are poor, children are likely to develop the same habits.

Some preschoolers still have food habits that are typical of toddlers, such as food fads and strong taste preferences. When children reach 4 years of age, they seem to enter another period of finicky eating, which is generally characteristic of the more rebellious behavior of children in this age-group. As with the toddler, small portions should be offered of each item being served. The practice of having the child remain at the table until the “plate is clean” should be avoided because this may contribute to overeating and the development of poor eating habits that contribute to poor health later in life. By age 5 years, children are more agreeable to trying new foods, especially if they are encouraged by an adult who allows them to help with food preparation or experiment with a new taste or different dish (Fig. 13-7). Mealtimes can become battlegrounds if parents expect perfect table manners.* Usually the 5-year-old child is ready for the “social” side of eating, but the 3- or 4-year-old child still has difficulty sitting quietly through a long family meal.

FIG. 13-7 Preschool-age children enjoy helping adults and are more likely to try new foods if they can assist in the preparation.

The amount and variety of foods consumed by young children vary greatly from day to day. Consequently, parents sometimes worry about the quantity and quality of food preschoolers consume. In general, the quality is much more important than the quantity, a fact that should be stressed during nutritional counseling.

One way to lessen parental concern is advising parents to keep a weekly record of everything the child eats. In particular, the parents can measure the amount of food, such as setting aside a half cup of vegetables and serving the child from this premeasured amount, to provide a more accurate estimate of food intake at each meal. When parents look at the food chart at the end of the week, they are usually amazed by how much the child has consumed. In general, preschoolers consume only slightly more than toddlers, or about half an adult’s portion.

SLEEP AND ACTIVITY

Sleep patterns vary widely, but the average preschooler sleeps about 12 hours a night and infrequently takes daytime naps. Waking during the night is common throughout early childhood and may be related to social rather than developmental factors (Thiedke, 2001). Motor activity levels continue to be high and allow preschoolers to explore their environment, begin learning physical games and sports, and interact with others. Sedentary activities, such as television and video or computer games, are increasingly appealing and can become an unhealthy substitute for active play.

Preschoolers’ increased gross motor abilities and coordination allow them to engage in many physical activities, if only at a novice level. Whether young children should begin formalized training in an activity at this early age is controversial. Training programs must consider the child’s physical and psychologic immaturity, and readiness to participate in organized sports should be determined individually. The decision to participate should be based on the child’s, not the parent’s, motivation and enjoyment. The American Academy of Pediatrics (2001b) encourages free play and a variety of physical activities; however, the academy also supports organized play when it is developmentally appropriate and occurs in a nonthreatening, fun, and safe environment.

Sleep Problems

The preschool years are a prime time for sleep disturbances. As toddlers and preschoolers cope with autonomy, separation, and object permanence, they begin to have more sleep problems (Thiedke, 2001). Some have trouble going to sleep, especially after so much activity and stimulation during the day. Others may develop bedtime fears, wake during the night, or have nightmares or sleep terrors. Still others may prolong the inevitable through elaborate rituals.

Recommendations for handling a sleep disturbance are offered only after a thorough assessment of the problem. Cultural traditions may dictate sleep practices that are contrary to certain well-accepted professional recommendations; therefore parents may not perceive a particular sleep practice as a problem (see Cultural Awareness box in Chapter 10, p. 349).

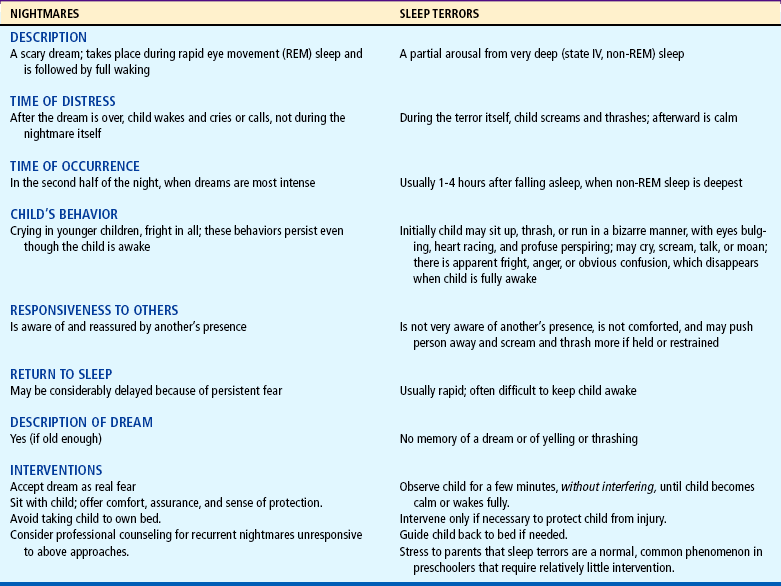

Interventions differ greatly; for example, nightmares (frightening dreams that are followed by full arousal) and sleep terrors (partial arousal from deep, nondreaming sleep) require different approaches (Table 13-2).

TABLE 13-2

Comparison of Nightmares to Sleep Terrors

Modified from Ferber R: Solve your child’s sleep problems, New York, 1985, Simon & Schuster. Simon & Schuster

For children who delay going to bed, a recommended approach involves counseling parents about the importance of a consistent bedtime ritual and emphasizing the normalcy of this type of behavior in young children. Parents should ignore attention-seeking behavior and not take the child into the parents’ bed or allow the child to stay up past a reasonable hour. Other measures that may be helpful include keeping a light on in the room, providing transitional objects such as a favorite toy, or leaving a drink of water by the bed.

Helping children slow down before bedtime also reduces the resistance to going to bed. One strategy is to establish limited rituals that signal readiness for bed, such as a bath or story. Parents can reinforce the pattern by stating, “After this story, it is bedtime,” and consistently carrying out the routine. If anticipated extra stimulation, such as having visitors arrive at bedtime, disrupts this routine, it is advisable to settle children in bed beforehand. Television viewing before bedtime may cause bedtime resistance and delay sleep.

DENTAL HEALTH

By the beginning of the preschool period, the eruption of the deciduous (primary) teeth is complete. Dental care is essential to preserve these temporary teeth and to teach good dental habits (see Chapter 12). Although preschoolers’ fine motor control is improved, they still require assistance and supervision with brushing, and flossing should be performed by parents. Professional care and prophylaxis, especially fluoride supplements (if needed), should be continued. Routine dental care should be well established during preschool years and is recommended at 6- to 12-month intervals depending on the family history, the child’s dental development, and the presence or absence of dental caries (Martof, 2001). For children cared for away from home, parents should be encouraged to monitor the dental care provided by others, including minimizing cariogenic foods in the diet. Trauma to teeth during this period is not uncommon, and prompt evaluation by a dentist is warranted if oral trauma occurs. Preservation of the space previously occupied by an avulsed tooth is necessary for proper eruption of the secondary tooth.

INJURY PREVENTION

Because of improved gross and fine motor skills, coordination, and balance, preschoolers are less prone to falls than are toddlers. They tend to be less reckless; listen more to parental rules; and are aware of potential dangers, such as hot objects, sharp instruments, and dangerous heights. Putting objects in the mouth as part of exploration has all but ceased, although accidental poisoning is still a danger. Pedestrian motor vehicle injuries increase because of activities such as playing in the parking lot, driveway, or street; riding tricycles, bicycles, and other play vehicles; running after balls; or forgetting safety regulations when crossing streets.

In general, the guidelines suggested for injury prevention in Table 12-3 apply to children in this age-group as well. However, emphasis is now on education concerning safety and potential hazards, in addition to appropriate protection. This period is an excellent time to start enforcing the use of safety items such as bicycle helmets to prevent head trauma; children are less likely to warm to the idea later in life because of peer pressure. Because preschoolers are great imitators, it is essential that parents set a good example by “practicing what they preach.” Children quickly observe discrepancies in what they are told to do and what they see others do. Establishing habits at this time, such as wearing protective equipment, can create long-term safety behaviors.

ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE—CARE OF FAMILIES

The preschool years present fewer childrearing difficulties than do earlier years, and this stage of development is facilitated by appropriate anticipatory guidance in the areas already discussed (see Family-Centered Care box). There is a shift in childrearing practices from protection to education. Whereas injury prevention previously focused on safeguarding the immediate environment, with less emphasis on reasoning, now the protective guardrails or electrical outlet caps may replaced by verbal explanations of why danger exists and how to avoid it.

During this period, an emotional transition between parent and child occurs. Although children are still attached to their parents and accept all their values and beliefs, they are nearing the period of life when they will question previous teachings and prefer the companionship of peers. Entry into school marks a separation from home for parents, as well as for children. Parents may need help in adjusting to this change, particularly if one parent has focused his or her daily activities primarily on home responsibilities. All family members must adjust to changes, which is part of the process of growth and development.

REFERENCES

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Public Education. Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107(2):423–426.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Committee on School Health. Organized sports for children and preadolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1459–1462.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. The use and misuse of fruit juices in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1210–1213.

Anderson, DR, Huston, AC, Schmitt, KL, et al. Early childhood television viewing and adolescent behavior: the recontact study. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2001;66(1):I–VIII. [1-147,].

Barlow, SE, Expert Committee. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–S192.

Barnes, LL, Plotnikoff, GA, Fox, K, et al. Spirituality, religion, and pediatrics: intersecting worlds of healing. Pediatrics. 2000;104(6):899–908.

Bendersky, M, Bennett, D, Lewis, M. Aggression at age 5 as a function of prenatal exposure to cocaine, gender, and environmental risk. J Pediatr Psychol Adv Access. 2006;31(1):71–84.

Brazelton, TB, Sparrow, JD. Touchpoints 3 to 6: your child’s emotional and behavioral development. Cambridge, Mass: Da Capo Press, 2001.

Brown, KD, Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. The influence of violent media on children and adolescents: a public-health approach. Lancet. 2005;365(9460):702–710.

Davison, KK, Birch, LL. Weight status and self-concept in young girls. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):46–53.

Endres, J, Barter, S, Theodora, P, et al. Soy-enhanced lunch acceptance by preschoolers. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(3):346–351.

Feldman, HM. Evaluation and management of language and speech disorders in preschool children. Pediatr Rev. 2005;26(4):131–142.

Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes: guiding principles for nutrition labeling and fortification. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2003.

Fosarelli, P. Children and the development of faith: implications for pediatric practice. Contemp Pediatr. 2003;20(1):85–98.

Gershoff, ET. Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: a meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychol Bull. 2002;128(4):539–579.

Gleason, TR, Sebanc, AM, Hartup, WW. Imaginary companions of preschool children. Dev Psychol. 2000;36(4):419–428.

Jellinek, M, Patel, BP, Froehle, MC, eds. Bright futures in practice: mental health, vol 1. Arlington, Va: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health, 2002.

Johnson, RK. Changing eating and physical activity patterns of U.S. children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2000;59(2):295–301.

Kleinman RE, ed. Pediatric nutrition handbook, ed 5, Elk Grove Village, Ill: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2004.

Martof, A. Consultation with the specialist: dental care. Pediatr Rev. 2001;22(1):13–15.

McEvoy, M. Culture and spirituality as an integrated concept in pediatric care. MCN. 2003;28(1):39–43.

McEvoy, M. An added dimension to the pediatric health maintenance visit: the spiritual history. J Pediatr Health Care. 2000;14(5):216–220.

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Stuttering. National Institutes of Health, 2002. retrieved March 2007 from http://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/voice/stutter

Needlman, R. Growth and development: preschool years. In Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, eds.: Nelson textbook of pediatrics, ed 17, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2004.

Rafanello, D. Controlling the spread of infectious disease in child care programs. Healthy Child Care Am. 2001;Winter:1–11.

Spear, BA, Barlow, SE, Ervin, C, et al. Recommendations for treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S254–S288.

Story M, Holt K, Sofka D, eds. Bright futures in practice: nutrition, ed 2, Arlington, Va: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health, 2002.

Thiedke, CC. Sleep disorders and sleep problems in childhood. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(2):277–284.

Yalçin, SS, Türul, B, Naçar, N, et al. Factors that affect television viewing time in preschool and primary schoolchildren. Pediatr Int. 2002;44(6):622–627.

*Recommended books for suggestions on mutual play include Quick and Fun Learning Activities books, by Teacher Created Resources, 6421 Industry Way, Westminster, CA 92683; (800) 662-4321; http://www.teachercreated.com.

*Information about accreditation criteria and procedures of the NAEYC Academy for Early Childhood Program Accreditation is available from the National Association for the Education of Young Children, 1313 L St. NW, Suite 500, Washington, DC 20005; (800) 424-2460 or (202) 232-8777; http://www.naeyc. org. These criteria are excellent guidelines for evaluating preschools or daycare centers.

*130 W. 42nd St., Suite 350, New York, NY 10036; (212) 819-9770; fax: (212) 819-9776; http://www.siecus.org.

†434 W. 33rd St., New York, NY 10001; (212) 541-7800 or (800) 230-7526; fax: (212) 245-1845; http://www.plannedparenthood.org.

‡American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Blvd., Elk Grove Village, IL 60007; (888) 227-1770; fax: (847) 228-1281; http://www.aap.org.

*Information on child development and behavior can be obtained through Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics Online, http://www.dbpeds.org.

*For a more comprehensive understanding, the reader is urged to review Promoting Optimal Health During Toddlerhood, Chapter 12.

*An excellent resource for parents related to mealtimes with toddlers and pre-schoolers is Satter E: How to get your kid to eat … but not too much, Palo Alto, Calif, 1987, Bull Publishing.

IN TEXT

IN TEXT

CULTURAL AWARENESS

CULTURAL AWARENESS

FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

FAMILY-CENTERED CARE