Health Promotion of the Toddler and Family

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

Identify the major biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, and social developments during the toddler years.

Identify the major biologic, psychosocial, cognitive, and social developments during the toddler years.

Relate separation anxiety and negativism to developmental tasks.

Relate separation anxiety and negativism to developmental tasks.

Recognize readiness for toilet training and offer parents guidelines.

Recognize readiness for toilet training and offer parents guidelines.

Provide parents with information to prepare toddlers for the birth of a sibling.

Provide parents with information to prepare toddlers for the birth of a sibling.

Provide parents with guidelines for handling temper tantrums.

Provide parents with guidelines for handling temper tantrums.

Provide parents with feeding recommendations.

Provide parents with feeding recommendations.

Outline a preventive dental hygiene plan for toddlers.

Outline a preventive dental hygiene plan for toddlers.

Provide anticipatory guidance to parents regarding injury prevention based on the toddler’s developmental achievements.

Provide anticipatory guidance to parents regarding injury prevention based on the toddler’s developmental achievements.

PROMOTING OPTIMAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

At times the term terrible twos is used to describe the toddler years, the period from 12 to 36 months of age. It is a time of intense exploration of the environment as children attempt to find out how things work and how to control others through temper tantrums, negativism, and obstinacy. Although this can be a challenging time for parents and child as each learns to know the other better, it is an extremely important period for developmental achievement and intellectual growth.

BIOLOGIC DEVELOPMENT

Physical growth slows considerably during toddlerhood. The average weight gain is 1.8 to 2.7 kg (4 to 6 pounds) per year. The average weight at 2 years is 12 kg (26.5 pounds). The birth weight is quadrupled by 2½ years of age. The rate of increase in height also slows. The usual increment is an addition of 7.5 cm (3 inches) per year and occurs mainly in elongation of the legs rather than the trunk. The average height of a 2-year-old is 86.6 cm (34 inches). In general, adult height is about twice the 2-year-old child’s height. Accurate measurement of height and weight during the toddler years should reveal a steady growth curve that is steplike in nature rather than linear (straight), which is characteristic of the growth spurts during the early childhood years.

The rate of increase in head circumference slows somewhat by the end of infancy, and head circumference is usually equal to chest circumference by 1 to 2 years of age. The usual total increase in head circumference during the second year is 2.5 cm (1 inch). Then the rate of increase slows until at age 5 years the increase is less than 1.25 cm (0.5 inch) per year. The anterior fontanel closes between 1 and 1½ years of age.

Chest circumference continues to increase in size and exceeds head circumference during the toddler years. The chest’s shape also changes as the transverse, or lateral, diameter exceeds the anteroposterior diameter. After the second year the chest circumference exceeds the abdominal measurement, which, in addition to the growth of the lower extremities, makes the child appear taller and leaner. However, the toddler retains a squat, “pot-bellied” appearance because of the less developed abdominal musculature and short legs. The legs retain a slightly bowed or curved appearance during the second year from the weight of the relatively large trunk.

Sensory Changes

Visual acuity of 20/40 is considered acceptable during the toddler years. Full binocular vision is well developed, and any evidence of persistent strabismus requires professional attention as early as possible to prevent amblyopia. Depth perception continues to develop, but because of the child’s lack of motor coordination, falls from heights continue to be a persistent danger.

The senses of hearing, smell, taste, and touch become increasingly well developed, coordinated with each other, and associated with other experiences. All of the senses are used to explore the environment. Toddlers will visually inspect an object by turning it over; they may taste it, smell it, and touch it several times before they are satisfied with their investigation. They will shake it to see if it makes noise and vigorously test its durability.

Another example of the integrated function of the senses is the toddler’s development of specific taste preferences. The child is much less likely than infants to try a new food because of its appearance, texture, or smell, not just its taste.

Maturation of Systems

Most of the physiologic systems are relatively mature by the end of toddlerhood. Volume of the respiratory tract and growth of associated structures continue to increase during early childhood, lessening some of the factors that predisposed the child to frequent and serious infections during infancy. The internal structures of the ear and throat continue to be short and straight, and the lymphoid tissue of the tonsils and adenoids continues to be large. As a result, otitis media, tonsillitis, and upper respiratory tract infections are common. The respiratory and heart rates slow, and the blood pressure increases (see inside back cover). Respirations continue to be abdominal.

Under conditions of moderate variation in temperature, the toddler rarely has the difficulties of the young infant in maintaining body temperature. The mature functioning of the renal system serves to conserve fluid under times of stress, decreasing the risk of dehydration.

The digestive processes are fairly complete by the beginning of toddlerhood. The acidity of the gastric contents continues to increase and has a protective function, since it is capable of destroying many types of bacteria. Stomach capacity increases to allow for the usual schedule of three meals a day.

One of the more prominent changes of the gastrointestinal system is the voluntary control of elimination. With complete myelination of the spinal cord, control of the anal and urethral sphincters is gradually achieved. The physiologic ability to control the sphincters probably occurs somewhere between ages 18 and 24 months. Bladder capacity also increases considerably. By 14 to 18 months of age the child is able to retain urine for up to 2 hours or longer.

The defense mechanisms of the skin and blood, particularly phagocytosis, are much more efficient in toddlers than in infants. The production of antibodies is well established. However, many young children demonstrate a sudden increase in colds and minor infections when they enter preschool or other group situations, such as daycare, because of their exposure to pathogens.

Rapid growth in neurobehavioral organization contributes to greater regularity of sleep-wake cycles, the diminishing of crying and unexplained fussiness, and the enhanced predictability in mood. Valuable stimulants of early brain development include the various interactions (talking, singing, and playing) between the toddler and caregivers. Adequate nutrition; protection from environmental toxins such as lead, various drugs, and stress; and promotion of good health care all contribute to healthy brain growth.

Gross and Fine Motor Development

The major gross motor skill during the toddler years is the development of locomotion. By 12 to 13 months of age toddlers walk alone using a wide stance for extra balance, and by 18 months they try to run but fall easily. Between 2 and 3 years of age, refinement of the upright, biped position is evident in improved coordination and equilibrium. At age 2 years, toddlers can walk up and down stairs, and by age 2½ years they can jump using both feet, stand on one foot for a second or two, and manage a few steps on tiptoe. By the end of the second year they can stand on one foot, walk on tiptoe, and climb stairs with alternate footing.

Fine motor development is demonstrated in increasingly skillful manual dexterity. For example, by age 12 months toddlers are able to grasp a very small object but are unable to release it at will. At 15 months they can drop a raisin into a narrow-necked bottle. Casting or throwing objects and retrieving them become almost obsessive activities at about 15 months. By 18 months of age toddlers can throw a ball overhand without losing their balance. By 2 years of age toddlers use their hands to build towers, and by 3 years of age they draw circles on paper.

Mastery of gross and fine motor skills is evident in all phases of the child’s activity, such as play, dressing, language comprehension, response to discipline, social interaction, and propensity for injuries. Activities occur less in isolation and more in conjunction with other physical and mental abilities to produce a purposeful result. For example, the toddler walks to reach a new location, releases a toy to pick it up or to choose a new one, and scribbles to look at the image produced. The possibilities of the exploration, investigation, and manipulation of the environment–and its hazards–are endless.

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

Toddlers are faced with the mastery of several important tasks. If the need for basic trust has been satisfied, they are ready to give up dependence for control, independence, and autonomy. Some of the specific tasks to be dealt with include:

Differentiation of self from others, particularly the mother

Differentiation of self from others, particularly the mother

Toleration of separation from parent

Toleration of separation from parent

Ability to withstand delayed gratification

Ability to withstand delayed gratification

Mastery of these goals is only begun during late infancy and the toddler years; tasks such as developing interpersonal relationships with others may not be completed until adolescence. However, crucial foundations for successful completion of such developmental tasks are laid during these early formative years.

Developing a Sense of Autonomy (Erikson)

According to Erikson, the developmental task of toddlerhood is acquiring a sense of autonomy while overcoming a sense of doubt and shame. As infants gain trust in the predictability and reliability of their parents, environment, and interaction with others, they begin to discover that their behavior is their own and that it has a predictable, reliable effect on others. Although they realize their will and control over others, they are confronted with the conflict of exerting autonomy and relinquishing the much-enjoyed dependence on others. Exerting their will has definite negative consequences, whereas retaining dependent, submissive behavior is generally rewarded with affection and approval. However, continued dependence creates a sense of doubt regarding their potential capacity to control their actions. This doubt is compounded by a sense of shame for feeling this urge to revolt against others’ will and a fear that they will exceed their own capacity for manipulating the environment. Skillful monitoring and balance of controls by parents allows a growing rate of realistic successes and the emergence of autonomy.

Just as the infant has the social modalities of grasping and biting, the toddler has the newly gained modality of holding on and letting go. To hold on and let go is evident with the use of the hands, mouth, eyes, and, eventually, the sphincters, when toilet training is begun. These social modalities are expressed constantly in the child’s play activities, such as throwing objects; taking objects out of boxes, drawers, or cabinets; holding on tighter when someone says, “No, don’t touch”; and refusing or spitting out food as taste preferences become very strong.

Several characteristics, especially negativism and ritualism, are typical of toddlers in their quest for autonomy. As toddlers attempt to express their will, they often act with negativism, the persistent negative response to requests. The words “no” or “me do” can be the sole vocabulary. Emotions become strongly expressed, usually in rapid mood swings. One minute, toddlers can be engrossed in an activity, and the next minute they might be angry because they are unable to manipulate a toy or open a door. If scolded for doing something wrong, they can have a temper tantrum and almost instantaneously pull at the parent’s legs to be picked up and comforted. Understanding and coping with these swift changes is often difficult for parents. Many parents find the negativism exasperating and, instead of dealing constructively with it, give in to it, which further threatens children in their search for learning acceptable methods of interacting with others (see Temper Tantrums and Negativism, p. 421).

In contrast to negativism, which frequently disrupts the environment, ritualism, the need to maintain sameness and reliability, provides a sense of comfort. Toddlers can venture out with security when they know that familiar people, places, and routines still exist. One can easily understand why any change in the daily routine represents such a threat to these children. Without comfortable rituals, they have little opportunity to exert autonomy. Consequently, dependency and regression occur (see Regression, p. 422).

Erikson focuses on the development of the ego, which may be thought of as reason or common sense, during this phase of psychosocial development. The child struggles to deal with the impulses of the id and attempts to tolerate frustration and learn socially acceptable ways of interacting with the environment. The ego is evident as the child is able to tolerate delayed gratification. Toddlers also have a rudimentary beginning of the superego, or conscience, which is the incorporation of the morals of society and the process of acculturation.

With the development of the ego, children further differentiate themselves from others and expand their sense of trust within themselves. But as they begin to develop awareness of their own will and capacity to achieve, they also become aware of their ability to fail. This ever-present awareness of potential failure creates doubt and shame. Successful mastery of the task of autonomy necessitates opportunities for self-mastery while withstanding the frustration of necessary limit setting and delayed gratification. Opportunities for self-mastery are present in appropriate play activities, toilet training, the crisis of sibling rivalry, and successful interactions with significant others (Fig. 12-1).

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT: SENSORIMOTOR AND PREOPERATIONAL PHASE (PIAGET)

The period from 12 to 24 months of age is a continuation of the final two stages of the sensorimotor phase. During this time the cognitive processes develop rapidly and at times seem similar to those of mature thinking. However, reasoning skills are still primitive and need to be understood to effectively deal with the typical behaviors of a child of this age.

Tertiary Circular Reactions.: In the fifth stage of the sensorimotor phase (13 to 18 months of age), the child uses active experimentation to achieve previously unattainable goals. Newly acquired physical skills are increasingly important for the function they serve rather than for the acts themselves. The child incorporates the old learning of secondary circular reactions with new skills and applies the combined knowledge to new situations, with emphasis on the results of the experimentation. In this way there is the beginning of rational judgment and intellectual reasoning. During this stage there is further differentiation of oneself from objects. This is evident in the child’s increasing ability to venture away from the parent and to tolerate longer periods of separation.

Awareness of a causal relationship between two events is apparent. After flipping a light switch, toddlers are aware that a reciprocal response occurs. However, they are not able to transfer that knowledge to new situations. Therefore every time they see what appears to be a light switch, they must reinvestigate its function. Such behavior demonstrates the beginning of categorizing data into distinct classes and subclasses. There are innumerable examples of this type of behavior as toddlers continuously explore the same object each time it appears in a new place.

Because classification of objects is still rudimentary, the appearance of an object denotes its function. For example, if the child’s toys are stored in a paper bag or large container, that toy receptacle is no different from the garbage pail or laundry basket. If allowed to turn over the toy receptacle, the child will just as quickly do the same to other similar containers because, in the child’s mind, there is no difference. Expecting the child to judge which receptacles are permissible to explore and which are not is inappropriate for this age-group. Instead, the forbidden object, such as the garbage pail, should be placed out of reach.

The discovery of objects as objects leads to the awareness of their spatial relationships. Children are able to recognize different shapes and their relationship to each other. For example, they can fit slightly smaller boxes into each other (nesting) and can place a round object into a hole, even if the board is turned around, upside down, or reversed. Children are also aware of space and the relationship of their body to dimensions such as height. They will stretch, stand on a low stair or stool, and pull a string to reach an object.

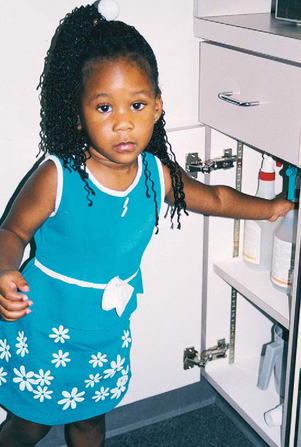

Object permanence has also advanced. Although they still cannot find an object that has been invisibly displaced or moved from under one pillow to another without their seeing the change, toddlers are increasingly aware of the existence of objects behind closed doors, in drawers, and under tables. Parents are usually acutely aware of this developmental achievement and find high places and locked cabinets the only places inaccessible to toddlers.

Invention of New Means Through Mental Combinations.: From ages 19 to 24 months the child is in the final sensorimotor stage. During this stage the child completes the more primitive, autistic-like thought processes of infancy and is prepared for the more complex mental operations that occur during the phase of preoperational thought. One of the most dramatic achievements of this stage is in the area of object permanence. Children will now actively search for an object in several potential hiding places. In addition, they can infer a cause when only experiencing the effect. They can infer that an object was hidden in any number of places even if they only saw the original hiding place.

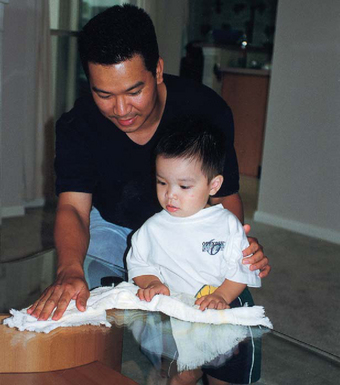

Imitation displays deeper meaning and understanding. There is greater symbolization to imitation. The child is acutely aware of others’ actions and attempts to copy them in gestures and in words. Domestic mimicry (imitating household activities) and sex-role behavior become increasingly common during this period and during the second year. Identification with the parent of the same gender becomes apparent by the second year and represents the child’s intellectual ability to differentiate different models of behavior and to imitate them appropriately (Fig. 12-2).

The conception of time is still embryonic, but children have some sense of timing in terms of anticipation, memory, and the limited ability to wait. They may listen to the command, “Just a minute,” and behave appropriately. However, their sense of timing is exaggerated–1 minute can seem like an hour. Toddlers’ limited attention spans also indicate their sense of immediacy and concern for the present.

Preoperational Phase.: At approximately 2 years of age the child enters the preconceptual phase of cognitive development, which lasts until about age 4 years. The preconceptual phase is a subdivision of the preoperational phase, which spans ages 2 to 7 years. The preconceptual phase is primarily one of transition that bridges the purely self-satisfying behavior of infancy and the rudimentary socialized behavior of latency. Preoperational thought implies that children cannot think in terms of operations—the ability to manipulate objects in relation to each other in a logical fashion. Rather, toddlers think primarily on the basis of their perception of an event. Problem solving is based on what they see or hear directly rather than on what they recall about objects and events. Several characteristics are unique to preoperational thought (Box 12-1).

Within the second year the child increasingly uses language symbolically and is concerned with the “why” and “how” of things. For example, a pencil is “something to write with,” and food is “something to eat.” However, such mental symbolization is closely associated with prelogical reasoning. For instance, a needle is “something that hurts.” Such painful experiences take on new significance because memory is associated with the specific event, and fears are likely to develop, such as resistance to people who wear colored uniforms or rooms that look like the practitioner’s office. Because of the vulnerability of these early years, it is essential to prepare children for any new experience, whether it is a new baby-sitter or a visit to the dentist.

SPIRITUAL DEVELOPMENT

Spiritual development in children is often discussed in terms of the child’s developmental level because the evolution of spirituality often parallels cognitive development (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). The child’s family and environment strongly influence the child’s perception of the world around him or her, and this often includes spirituality. Furthermore, family values, beliefs, customs, and expressions of these will influence the child’s perception of his or her spiritual self (Elkins and Cavendish, 2004). The relationship between spirituality, illness in childhood, and nursing has been studied in the context of suffering, terminal illness such as cancer, and end-of-life care. In the past two decades there has been an increased interest in and focus on spiritual care in adults and children as further understanding of the influence of one’s spirituality on health, illness, and well-being has progressed.

Toddlers learn about God through the words and the actions of those closest to them. They have only a vague idea of God and religious teachings because of their immature cognitive processes; however, if God is spoken about with reverence, young children associate God with something special. During this period the assignment of powerful religious symbols and images is strongly influenced by the manner in which it is presented; therein lies the potential for the development of guilt and fear or, conversely, love and companionship with religious symbols (Roehlkepartain, King, Wagener, and others, 2006).

Toddlers begin to assimilate behaviors associated with the divine (folding hands in prayer). Routines such as saying prayers before meals or at bedtime can be important and comforting. Because toddlers tend to find solace in ritualistic behavior and routines, they incorporate routines associated with religious practices into their behavioral patterns, without Box 12-1 understanding all the implications of the rituals until later. Near the end of toddlerhood, when children use preoperational thought, there is some advancement of their understanding of God. Religious teachings, such as reward or fear of punishment (heaven or hell) and moral development (see Chapter 5), may influence their behavior (Fosarelli, 2003).

DEVELOPMENT OF BODY IMAGE

As in infancy, the development of body image closely parallels cognitive development. Developing psychologic understanding provides greater self-awareness, and young children learn to answer the question “Who am I?” During the second year, children recognize themselves in a mirror and make verbal references to themselves (“Me big”). With increasing motor ability, toddlers recognize the usefulness of body parts and gradually learn their names. They also learn that certain parts of the body have various meanings; for example, during toilet training the genitalia become significant and cleanliness is emphasized. By 2 years of age they recognize gender differences and refer to themselves by name and then by pronoun. Gender identity is developed by age 3 years. Also by this time the child begins to remember events with reference to their personal significance, forming an autobiographic memory that helps to establish a continuous identity throughout life’s events (Thompson, 2001).

After they begin preoperational thought, toddlers can use symbols to represent objects, but their thinking may lead to inaccuracies. For example, if someone who is pregnant is called “fat,” they will describe all “fat” women as having babies. They begin to recognize words used to describe physical appearance, such as pretty, handsome, or big boy. Such expressions eventually influence how children view their own bodies.

Although little research has been done on body-image development in young children, it is evident that body integrity is poorly understood and that intrusive experiences are threatening (Dahlquist, Busby, Slifer, and others, 2002). For example, toddlers forcefully resist procedures such as examining the ear or mouth or taking a rectal temperature. Toddlers also have unclear body boundaries and may associate nonviable parts, such as feces, with essential body parts. This can be seen in a toddler who is upset by flushing the toilet and watching the stool disappear.

Nurses can assist parents in fostering a positive body image in their child by encouraging them to avoid negative labels, such as “skinny arms” or “chubby legs”—self-perceptions that can last a lifetime. Body parts, especially those related to elimination and reproduction, should be called by their correct names. Respect for the body should be practiced.

DEVELOPMENT OF GENDER IDENTITY

Just as toddlers explore their environment, they also explore their bodies and find that touching certain body parts is pleasurable. Masturbation can occur and involves manual stimulation of genitals and posturing movements against objects. Other demonstrations of sensual activities include rocking, sucking on fingers and toes, swinging, and hugging people and toys. During the activity the child may perspire, and the activity may be difficult to interrupt. If performed in public, the behavior should be ignored. The child should be taught that it is more acceptable to perform the behavior in private (Meyer, 2002).

Children in this age-group are learning vocabulary associated with anatomy, elimination, and reproduction. Certain associations between words and functions become significant and can influence future sexual attitudes. For example, if parents refer to the genitalia as dirty, especially in the context of elimination, this association between “genitalia” and “dirty” may be transferred to sexual functions.

Sex-role differences become obvious to children and are evident in much of their imitative play. A sense of maleness or femaleness, gender identity, is formed by age 3 years. Early attitudes are formed about affectionate behaviors between adults from observing parental and other adult sexual or sensual activities. (See also Sex Education, Chapter 13.) The quality of relationships with parents is important to the child’s capacity for sexual and emotional relationships later in life (DeLamater and Friedrich, 2002).

SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

A major task of the toddler period is differentiation of self from significant others, usually the mother. The differentiation process consists of two phases: separation, the children’s emergence from a symbiotic fusion with the mother; and individuation, those achievements that mark children’s expression of their individual characteristics in the environment. Although the process begins during the latter half of infancy, the major achievements occur during the toddler years.

Toddlers have an increased understanding and awareness of object permanence and some ability to withstand delayed gratification and tolerate moderate frustration. As a result, toddlers react differently to strangers than do infants. The appearance of unfamiliar persons does not represent such a significant threat to their attachment to mother. They have learned from experience that parents exist when physically absent. Repetition of events such as going to bed without the parents but waking to find them there again reinforces the reliability of such brief separations. Consequently, toddlers are able to venture away from their parents for brief periods because of the security of knowing that the parents will be there when they return. Verbal and visual reassurance from the parent gradually replaces some of the previous need to be physically close for comfort.

According to Harpaz-Rotem and Bergman (2006), the separation-individuation phase encompasses the phenomenon of rapprochement; as the toddler separates from the mother and begins to make sense of experiences in the environment, he or she is drawn back to the mother for assistance in verbally articulating the meaning of the experiences. Developmentally the term rapprochement means the child moves away and returns for reassurance. If the mother’s response to the toddler is inappropriate, the toddler may experience insecurity and confusion.

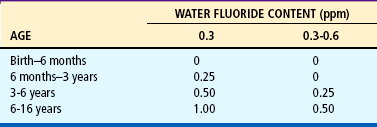

Transitional objects, such as a favorite blanket or toy, provide security for children, especially when they are separated from parents, dealing with a new stress, or just fatigued (Fig. 12-3). Security objects often become so important to toddlers that they refuse to let them be taken away. Such behavior is normal; there is no need to discourage this tendency. During separations, such as daycare, hospitalization, or even staying overnight with a relative, transitional objects should be provided to minimize any fear or loneliness.

FIG. 12-3 Transitional objects, such as a warm and fuzzy stuffed animal, are sources of security to a toddler.

Learning to tolerate and master brief periods of separation is an important developmental task for children in this age-group. In addition, it is a necessary component of parenting, since brief periods of separation allow parents to restore their energy and patience and to minimize directing their irritations and frustrations at the children.

Language

The most striking characteristic of language development during early childhood is the increasing level of comprehension. Although the number of words acquired—from about four at 1 year of age to approximately 300 at age 2 years–is notable, the ability to comprehend and understand speech is much greater than the number of words the child can say. Bilingual children can also achieve their early linguistic milestones in each of the languages at the same time and produce a substantial number of semantically corresponding words in each of their two languages from the very first words or signs (Petitto, Katerlos, Levy, and others, 2001).

At age 1 year the child uses one-word sentences or holophrases. The word “up” can mean “pick me up” or “look up there.” For the child the one word conveys the meaning of a sentence, but to others it may mean many things or nothing. At this age about 25% of the vocalizations are intelligible. By the age of 2 years the child uses multiword sentences by stringing together two or three words, such as the phrases “mama go bye-bye” or “all gone,” and approximately 65% of the speech is understandable. By 3 years the child puts words together into simple sentences, begins to master grammatical rules (syntax development), and acquires five or six new words daily.

Gestures precede or accompany each of the language milestones up to 30 months of age (putting phone to ear, pointing). After sufficient language development, gestures phase out and the pace of word learning increases (Bates and Dick, 2002).

Personal-Social Behavior

One of the most dramatic aspects of development in the toddler is personal-social interaction. Personal-social behaviors are evident in such areas as dressing, feeding, playing, and establishing self-control. Parents frequently wonder why their manageable, docile, lovable infant has turned into a determined, strong-willed, volatile little tyrant. In addition, the tyrant of the terrible twos can swiftly and unpredictably revert back to the adorable infant. All of this is part of growing up, as toddlers acquire a more sophisticated awareness that others’ feelings and desires can be different from their own. Through interactions with caregivers, the child is able to explore these differences and their consequences.

Toddlers are developing skills of independence, which are evident in all areas of behavior. By 15 months children feed themselves, drink well from a covered cup, and manage a spoon with considerable spilling. By 2 years they use a spoon well, and by 3 years they may be using a fork. Between ages 2 and 3 years they eat with the family and like to help with chores such as setting the table or removing dishes from the dishwasher, but they lack table manners and may find it difficult to sit through the family’s entire meal.

In dressing, toddlers also demonstrate strides in independence. The 15-month-old child helps by putting the arm or foot out for dressing and pulls shoes and socks off. The 18-month-old child removes gloves, helps with pullover shirts, and may be able to unzip. By age 2 years the toddler removes most articles of clothing and puts on socks, shoes, and pants without regard for right or left and back or front. Help is still needed to fasten clothes.

Toddlers also begin to develop concern for the feelings of others and develop an understanding of how adult expectations for behavior apply to specific situations (e.g., causing a sibling to cry while playing rough) (Thompson, 2001). As their understanding is fostered, they are able to develop control. Age-appropriate discipline contributes to healthy social and emotional development. Positive reinforcement, redirection, and time-out are appropriate for most toddlers. Social and emotional problems can develop in the youngest children. Early screening and intervention promote more positive outcomes as the young child grows and develops.

Play

Play magnifies the toddler’s physical and psychosocial development. Interaction with people becomes increasingly important. The solitary play of infancy progresses to parallel play—the toddler plays alongside, not with, other children. Although sensorimotor play is still prominent, there is much less emphasis on the exclusive use of one sensory modality. The toddler inspects the toy, talks to the toy, tests its strength and durability, and invents several uses for it. Imitation is one of the most distinguishing characteristics of play and enriches children’s opportunity to engage in fantasy. With less emphasis on gender-stereotyped toys, play objects such as dolls, carriages, dollhouses, balls, dishes, cooking utensils, child-size furniture, trucks, and dress-up clothes are suitable for both genders (Fig. 12-4); however, boys may be more interested than girls in activities related to trucks, trailers, men, and building blocks, whereas girls may prefer doll-related activities.

Increased locomotive skills make push-pull toys, straddle trucks or cycles, a small gym and slide, balls of various sizes, and riding toys appropriate for the energetic toddler. Finger paints, thick crayons, chalk, blackboard, paper, and puzzles with large, simple pieces use the child’s developing fine motor skills. Interlocking blocks in various sizes and shapes provide hours of fun and, during later years, are useful objects for creative and imaginative play. The most educational toy is the one that fosters the interaction of an adult with a child in supportive, unconditional play. Toys are never substitutes for the attention of devoted caregivers, but toys can enhance these interactions (Glassy, Romano, and Committee on Early Childhood, 2003).

Certain aspects of play are related to emerging linguistic abilities. Talking is a form of play for toddlers, who enjoy musical toys such as age-appropriate cassette tape players, “talking” dolls and animals, and toy telephones. Appropriate children’s television programs are excellent for children in this age-group, who learn to associate words with visual images. However, total media time should be limited to 1 to 2 hours of quality programming per day (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001). Toddlers also enjoy “reading” stories from a picture book and imitating the sounds of animals.

Tactile play is also important for the exploring toddler. Water toys, a sandbox with pail and shovel, finger paints, soap bubbles, and clay provide excellent opportunities for creative and manipulative recreation. Adults sometimes forget the fascination of feeling textures such as slippery cream, mud, or pudding; catching air bubbles; squeezing and reshaping clay; or smearing paints. These types of unstructured activities are as important as educational play to allow children freedom of expression.

Selection of appropriate toys must involve safety factors, especially in relation to size and sturdiness. The oral activity of toddlers puts them at risk for aspirating small objects or ingesting toxic substances. Parents need to be especially vigilant of toys played with in other children’s homes or those of older siblings. Toys are a potential source of serious bodily damage to toddlers, who may have the physical strength to manipulate them but not the knowledge to appreciate their danger (Stephenson, 2005) (see Family-Centered Care box: Toy Safety, Chapter 5). Government agencies do not inspect and police all toys on the market. Therefore adults who purchase play equipment, supervise purchases, or allow children to use play equipment need to evaluate its safety, including toys that are gifts or those that are purchased by the children themselves. Adults should also be alert to notices of toys determined to be defective and recalled by the manufacturers. Parents and health care workers can obtain information on a variety of recalled products and can report potentially dangerous toys and child products to the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission* or, in Canada, the Canadian Toy Testing Council.† Printable tips on toy safety are also available from Safe Kids Worldwide.‡

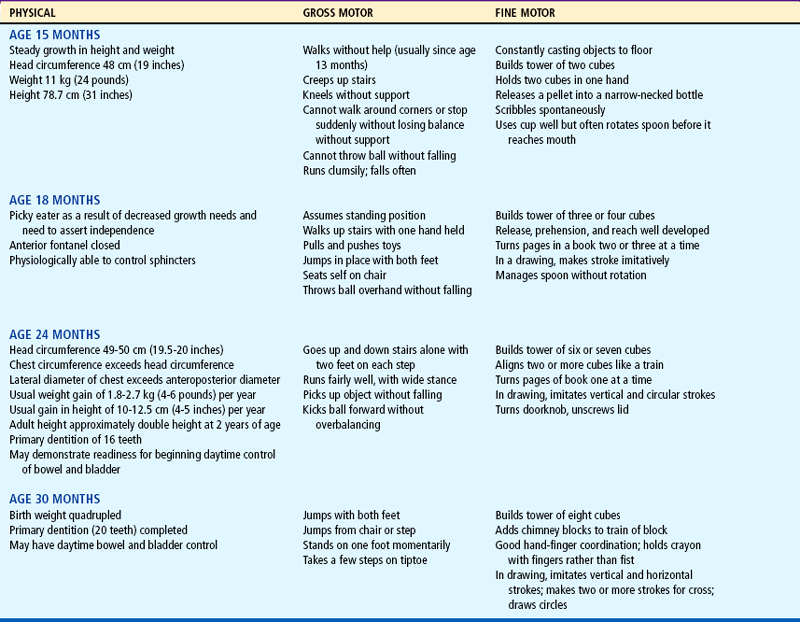

Table 12-1 summarizes the major features of growth and development for the age-groups of 15, 18, 24, and 30 months.

COPING WITH CONCERNS RELATED TO NORMAL GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT

One of the major tasks of toddlerhood is toilet training. Anticipatory guidance and clinical intervention for families surrounding toilet training should begin during routine well-child visits before the child’s developmental readiness to toilet train. Preparation and education reveal and allay misconceptions; lead to the development of appropriate expectations; and provide information, guidance, and support to parents for managing this potentially frustrating process.

Voluntary control of the anal and urethral sphincters is achieved sometime after the child is walking, probably between ages 18 and 24 months. However, complex psychophysiologic factors are required for readiness. The child must be able to recognize the urge to let go and hold on and be able to communicate this sensation to the parent. In addition, some motivation is probably involved in the desire to please the parent by holding on, rather than pleasing oneself by letting go.

Schmitt (2004) notes that comparative studies over the past five decades indicate that children in the 1990s in the United States were toilet trained at a later age (18 months in the 1960s vs 36 months in the 1990s); one possible contributing factor is the availability and convenience of disposable diapers.

Five markers signal a child’s readiness to toilet train: bladder readiness, bowel readiness, cognitive readiness, motor readiness, and psychologic readiness (Schmitt, 2004). According to some experts, physiologic and psychologic readiness is not complete until ages 22 to 30 months (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, and others, 2002); however, Schmitt (2004) emphasizes that parents should begin preparing the child for toilet training earlier than 30 months. By this time the child has mastered the majority of essential gross motor skills, can communicate intelligibly, is in less conflict with parents in terms of self-assertion and negativism, and is aware of the ability to control the body and please the parent. There is no universal right age to begin toilet training or an absolute deadline to complete training. One of the nurse’s most important responsibilities is to help parents identify the readiness signs in their child (see Nursing Care Guidelines box).* On average, girls are developmentally ready to begin toilet training 2 to 2½ months before boys (Schum, Kolb, McAuliffe, and others, 2002).

Nighttime bladder control normally takes several months to years after daytime training begins. This is because the sleep cycle needs to mature so the child can awake in time to urinate. Few children will have night wetting episodes after daytime dryness is totally achieved; however, those children who do not have nighttime dryness by the age of 6 years are likely to require intervention (Mercer, 2003).

Bowel training is usually accomplished before bladder training because of its greater regularity and predictability. There is a stronger sensation for defecation than for urination, and the sensation of defecation can be brought to the child’s attention. A well-balanced diet that includes dietary fiber helps keep stool soft and supports the development and maintenance of regular bowel movements.

A number of techniques can be helpful when initiating training, and cultural differences should be considered. Parents should begin the readiness phase of toilet training by teaching the child about how the body functions in relation to voiding and having a stool. Schmitt (2004) suggests that parents talk about how adults and animals perform such functions on a routine basis. Another suggestion is to make toilet training as easy and simple as possible. The selection of the child’s clothing is an important consideration, as is the potty chair or use of the toilet. A freestanding potty chair allows children a feeling of security. Planting the feet firmly on the floor also facilitates defecation. Another option is a portable seat attached to the regular toilet, which may ease the transition from potty chair to regular toilet (Fig. 12-5). Placing a small bench under the feet helps stabilize the child’s position. It is probably best to keep the potty in the bathroom and to let the child observe the excreta being flushed down the toilet to associate these activities with usual practices. If a potty chair is not available, having the child sit facing the toilet tank provides added support. Practice sessions should be limited to 5 to 8 minutes, and a parent should stay with the child, practicing sanitary habits after every session. Children should be praised for cooperative behavior and successful evacuation. Dressing children in easily removed clothing; using training pants, “pull-on” diapers, or underwear; and encouraging imitation by watching others are other helpful suggestions.

FIG. 12-5 A, Sitting in reverse fashion on a regular toilet provides additional security to a young child. B, Children may begin toilet training sitting on a small potty chair.

When the child begins to experience regular daytime dryness, parents may experiment with underwear during the day. Daytime accidents are common, particularly during periods of intense activity. Young children become so engrossed in play activity that, if they are not reminded, they will wait until it is too late to reach the bathroom. Therefore frequent reminders and trips to the toilet are necessary. Parents often forget to plan ahead when the toddler is being toilet trained; before trips outside the house it is important to remind the child to at least try to urinate to decrease the chance of needing to use the toilet while the car is stuck in traffic.

As the child masters each step of toileting (discussion, undressing, going, wiping, dressing, flushing, and hand washing), he or she gains a sense of accomplishment that parents should reinforce. If the parent-child relationship becomes strained, both may need a break to focus on enjoyable activities together. Regression may coincide with a stressful family situation or the child being pushed too hard and too fast. Regression is a normal part of toilet training and does not mean failure but should be viewed as a temporary setback to a more comfortable place for the child.

Daycare providers also play a role in the support and education of parents regarding toilet training practices. It is important for parents to inform all caregivers of their individual family values and the child’s specific needs when planning for training away from home. Ensuring consistency in care of the toddler, as well as ensuring healthy practices in a sanitary environment, allows for safe and effective toilet practices in all settings.

Sibling Rivalry

Children have a natural jealousy and resentment toward a new child in the family or toward other children in the family when a parent turns his or her attention from them and interacts with their brother or sister; this is referred to as sibling rivalry.

The arrival of a new infant represents a crisis for even the best-prepared toddlers. They do not hate or resent the infant, but the changes that this additional sibling produces, especially the separation from mother during the birth. The parents now share their love and attention with someone else, the usual routine is disrupted, and toddlers may lose their crib or room–all at a time when they thought they were in control of their world. Sibling rivalry tends to be most pronounced in the firstborn, who experiences dethronement (loss of sole parental attention). It also seems to be most difficult for young children, particularly in terms of mother-child interaction.

Preparation of children for the birth of a sibling is individual, but dictated to some extent by age. Time for toddlers is a vague concept. Tomorrow could be yesterday or next week, and a month from now could be never. Preparing children too soon for the birth may lessen their interest by the time the event occurs. A good time to start talking about the baby is when toddlers become aware of the pregnancy and the changes taking place in the home in anticipation of the new member.

Toddlers need to have a realistic idea of what the newborn will be like. Telling them that a new playmate will come home soon sets up unrealistic expectations. Rather, parents should stress the activities that will take place when the baby arrives home, such as diapering, bottle feeding or breastfeeding, bathing, and dressing. At the same time, parents should emphasize which routines will stay the same, such as reading stories or going to the park. If toddlers have had no contact with an infant, it is a good idea to introduce them to one, if feasible. Providing a doll with which toddlers can imitate parental behaviors is another excellent strategy. They can tend to the doll’s needs (diapering, feeding) at the same time the parent is performing similar activities for the infant.

A new sibling in the home is stressful, so any additional stresses for the toddler should be avoided or minimized. For example, moving the toddler to a regular bed or to a different room should be done well in advance of the infant’s arrival.

Pregnancy is an abstraction for toddlers. They need concrete illustrations of how the baby is growing inside the mother. It is an excellent opportunity for introducing aspects of reproduction in simple terms that the child can comprehend. Seeing simple pictures of the uterus and fetus and feeling the fetus move help the child feel involved in the experience. Children also benefit from classes for siblings that may be part of prenatal sessions.

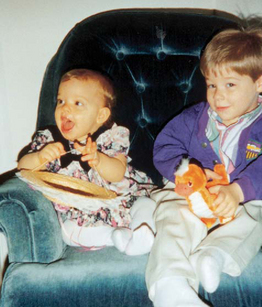

When the new baby arrives, toddlers keenly feel the changed focus of attention. Visitors may initiate problems when they inadvertently shower the infant with attention and presents while neglecting the older child. Parents can minimize this by alerting visitors to the toddler’s needs, having small presents on hand for the toddler, and including the child in the visit as much as possible. The toddler can also help with the care of the newborn by getting diapers and doing other small tasks (Fig. 12-6).

FIG. 12-6 To minimize sibling rivalry, parents should include the toddler during caregiving activities.

How children exhibit jealousy is complex. Some will hit the infant, push the child off the mother’s lap, or pull the bottle or breast from the infant’s mouth. For this reason, infants must be protected by parental supervision of the interaction between the siblings. More often, however, the expressions of hostility and resentment are more subtle and covert. Toddlers may verbally express a wish that the infant “go back inside mommy,” or they will revert to more infantile forms of behavior, such as demanding a bottle, soiling their underpants, clinging for attention, using baby talk, or aggressively acting out toward others. The latter is particularly common in preschoolers, who may seem accepting of the new sibling at home but behave poorly in daycare or preschool. This is a form of displacement that says, “I can’t let my parents know how I feel, so I will tell you.”

Temper Tantrums

Temper tantrums are nearly universal during toddlerhood as independence is established and more complex tasks are attempted that may overwhelm the child emotionally. Toddlers may assert their independence by violently objecting to discipline. They may lie down on the floor, kick their feet, and scream at the top of their lungs. Some have learned the effectiveness of holding their breath until the parent relents. Although holding one’s breath may cause fainting from the lack of oxygen, the accumulation of carbon dioxide will stimulate the respiratory control center, resulting in no physical harm. Rarely, breath-holding spells can involve symmetric tonic-clonic movements, which can be frightening to parents; the child recovers quickly once the spell is over, and there is no residual damage (Stein, 2003). Tantrums are an indication of the child’s inability to control emotions; toddlers are particularly prone to tantrums because their strong drive for mastery and autonomy is frustrated by adult figures or lack of motor and cognitive skills (Needlman, Howard, and Zuckerman, 1995).

The best approach toward tapering temper tantrums requires consistency and developmentally appropriate expectations and rewards. Ensuring consistency among all caregivers in expectations, prioritizing what rules are important, and developing consequences that are reasonable for the child’s level of development help manage the behavior. For example, a popular time for a tantrum is before bed. Active toddlers often have trouble slowing down and, when placed in bed, resist staying there. Parents can reinforce consistency and expectations by stating, “After this story it is bedtime.” Starting at 18 months, time-outs work well for managing temper tantrums.

During tantrums, parents should ignore the behavior, provided the behavior is not injurious to the child, such as violently banging the head on the floor. They should continue to be present to provide a feeling of control and security to the child once the tantrum has subsided. At this time a toy or a favorite activity can be substituted for the request (see also Limit Setting and Discipline, Chapter 3). During periods of no tantrums, parents can practice developmentally appropriate positive reinforcement.

Other suggestions for handling tantrums include (Needlman, Howard, and Zuckerman, 1995):

Offering the child options instead of an “all or none” position

Offering the child options instead of an “all or none” position

Picking one’s battles carefully and ignoring small skirmishes over unimportant issues

Picking one’s battles carefully and ignoring small skirmishes over unimportant issues

Giving comfort once the child is able to control emotions but not giving in to the original request

Giving comfort once the child is able to control emotions but not giving in to the original request

Praising the child for positive behavior when he or she is not having a tantrum

Praising the child for positive behavior when he or she is not having a tantrum

Temper tantrums are common during the toddler years and essentially represent normal developmental behaviors. However, temper tantrums can be signs of serious problems. Nurses should be alert to situations that require further evaluation.

Negativism

One of the more difficult aspects of rearing children in this age-group is their persistent “no” response to every request. The negativism is not an expression of being stubborn or insolent, but a necessary assertion of self-control. Children test limits to gain understanding of the world and to learn to modify their behavior to fit the expectations of society. Negativism begins to subside as most children prepare to enter kindergarten.

One method of dealing with the negativism is to reduce the opportunities for a “no” answer. Asking the child, “Do you want to go to sleep now?” is an example of a question that will almost certainly be answered with an emphatic “no.” Instead, tell the child that it is time to go to sleep and proceed accordingly. In their attempt to exert control, children like to make choices. When confronted with appropriate choices, such as “You may have a peanut butter and jelly sandwich or chicken noodle soup for lunch,” they are more likely to choose one rather than automatically say no. However, if their response is negative, parents should make the choice for the child.

Nurses working with children and parents can assist parents in understanding this concept by role modeling. For example, when the nurse approaches the toddler for taking vital signs, instead of asking “Can I listen to your heart?” the nurse can say, “I am going to listen to your heart.” Because of normal developmental behavior, the toddler is first going to resist attempts at taking vital signs because it is an intrusion on her body. Second, the toddler is most likely going to answer “no,” not because he or she necessarily fears the procedure itself, but because of the tendency to answer all questions with a negative response. If the nurse asks the question and the toddler says “no” but the nurse proceeds anyway, the toddler starts to mistrust the nurse’s actions, since they contradict his or her words.

Regression

The retreat from one’s present pattern of functioning to past levels of behavior is referred to as regression. It usually occurs in instances of discomfort or stress when one attempts to conserve psychic energy by reverting to patterns of behavior that were successful in earlier stages of development. Regression is common in toddlers, since almost any additional stress hinders their ability to master present developmental tasks. Any threat to their autonomy, such as illness, hospitalization, separation from a parent, disruption of established routines, or adjustment to a new sibling, represents a need to revert to earlier forms of behavior, such as increased dependency; refusal to use the potty chair; temper tantrums; demand for the bottle or pacifier; and loss of newly learned motor, language, social, and cognitive skills.

At first, such regression appears acceptable and comfortable for children, but the loss of newly acquired achievements is frightening and threatening, since children are aware of their helplessness. Parents become concerned about regressive behavior and frequently, in their efforts to deal with it, force the child to cope with an additional source of stress: the pressure to live up to expected standards. Brazelton (1999) suggests that these predictable times of regression, or touchpoints, are an opportunity to prepare parents for the next step in their child’s development.

When regression does occur, the best approach is to ignore it while praising existing patterns of appropriate behavior. Regression is a child’s way of saying, “I can’t cope with this present stress and perfect this skill as well, but I will if given patience and understanding.” For this reason, it is advisable not to attempt new areas of learning when an additional crisis is present or expected, such as beginning toilet training shortly before a sibling is born or during a brief period of hospitalization.

PROMOTING OPTIMAL HEALTH DURING TODDLERHOOD

From 12 to 18 months of age, the growth rate slows, decreasing the child’s need for calories, protein, and fluid. However, the requirements for protein (1.2 g/kg) and calories (102 kcal/kg) are still relatively high to meet the demands for muscle tissue growth and high activity level. The requirements for most vitamins and minerals increase slightly during toddlerhood. The need for minerals such as iron, calcium, and phosphorus may be difficult to meet, considering the characteristic food habits of children in this age-group.

At approximately 18 months of age, most toddlers manifest this decreased nutritional need with a decreased appetite, a phenomenon known as physiologic anorexia. They become picky, fussy eaters with strong taste preferences. They may eat large amounts one day and almost nothing the next. Toddlers are increasingly aware of the nonnutritive function of food: the pleasure of eating, the social aspect of mealtime, and the control of refusing food. They are influenced by factors other than taste when choosing food. If a family member refuses to eat something, toddlers are likely to imitate that response. If the plate is overfilled, they are likely to push it away, overwhelmed by its size. If food does not appear or smell appetizing, they will probably not agree to try it. In essence, mealtime is more closely associated with psychologic components than with nutritional ones.

The ritualism of this age also dictates certain principles in feeding practices. Toddlers like to have the same dish, cup, or spoon every time they eat. They may reject a favorite food simply because it is served in a different dish. If one food touches another, they often refuse to eat it. Mixed foods, such as stews or casseroles, are rarely favorites. Because toddlers have unpredictable table manners, it is best to use plastic dishes and cups, for both economic and safety reasons. For some children a regular mealtime schedule also contributes to their desire and need for predictability and ritualism.

Developmentally, by 12 months of age most children are eating many of the same foods prepared for the rest of the family. Some may have mastered using a cup with occasional spilling, although most cannot adeptly use a spoon until 18 months of age or later and generally prefer using their fingers.

Nutritional Counseling

The emphasis on preventing childhood obesity and subsequent cardiovascular disease in the United States has prompted a number of changes in dietary recommendations for children and adults alike. It is now recognized that lifetime eating habits may be established in early childhood, and health care workers are increasingly emphasizing the role of food selection choices, exercise, stress reduction, and other lifestyle choices (tobacco and alcohol use) on the quality of adult life and survival. Conditions such as obesity and cardiovascular disease can be prevented by encouraging healthy eating habits in toddlers and their families.

If food is used as a reward or sign of approval, a child may overeat for nonnutritive reasons. If food is forced and mealtime is consistently unpleasant, the usual pleasure associated with eating may not develop. Mealtimes should be enjoyable rather than times for discipline or family arguments. The social aspect of mealtime may be distracting for young children; therefore an earlier feeding hour may be appropriate. Young children are unable to sit through a long meal and become restless and disruptive. This is particularly common when children are brought to the table just after active play. Calling them in from play 15 minutes before mealtime allows them ample opportunity to get ready for eating while settling down their active minds and bodies.

The method of serving food also takes on more importance during this period. Toddlers need to have a sense of control and achievement in their abilities. Giving them large, adult-size portions can overwhelm them. In general, what is eaten is much more significant than how much is consumed. Small amounts of meat and vegetables supply greater food value than a large consumption of bread or potato. Serving sizes need to be appropriate for age (Box 12-2). Young children tend to like less spicy, bland food, although this is a culturally determined preference. Substitutions can be provided for foods that they do not enjoy, although parents need not cater to all of their desires. Frequent nutritious snacks can replace a meal. Grazing—nibbling and snacking–is a good way to ensure proper nutrition, provided that appropriate foods are offered.

Mastication skills continue to mature, putting children at risk for choking; therefore large round foods (hot dogs, grapes, peas, carrots, popcorn, fruit gel snacks) should be avoided until the child is able to chew them effectively. Active play while eating should be discouraged to prevent choking. Appetite and food preferences are sporadic. Often the interest in food parallels a growth spurt, so that periods of good eating are interspersed with phases of poor eating. If exposed to the same food every day, a young toddler does not learn how to manage the complex sensory information needed to eat new, more difficult foods (vegetables with a different texture vs pureed, slippery fruits). To help prevent “food jags,” it is recommended that parents present food in various physical forms. The child may need to progress to eating new foods in a stepwise fashion: visually tolerating the food, interacting with the food, smelling the food, touching the food, tasting, and then eating the food.

Many authorities consider this period of picky eating to be a developmental phase and stress that most toddlers will consume the necessary amount of food required for growth (Cathey and Gaylord, 2004). It has also been suggested that parents plan a nutritionally balanced week instead of day because of the way toddlers will restrict food intake in their effort to exert control over their environment (Morin, 2007).

Dietary Guidelines

Dietary guidelines are necessary to promote adequate energy and nutrient intake to support physical, emotional, psychologic, and cognitive development. A number of new dietary guidelines have been developed to address the issue of childhood obesity, sedentary lifestyles, and increase in cardiovascular disease mortality in the United States. Guidelines such as the 2005 American Heart Association Dietary Guidelines* provide suggestions for children ages 2 years and up and are discussed in Chapter 11. In addition, Chapter 11 discusses the Dietary Reference Intakes developed by the Institute of Medicine and the food guide pyramids MyPyramid and MyPyramid for Kids (see Fig. 11-1), developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (2005), which provide dietary guidelines for proper food selection and serving sizes tailored to the child’s level of activity and lifestyle.

Nutrition during toddlerhood involves a transition as a young toddler is weaned off milk- or formula-based diets. Milk intake, the chief source of calcium and phosphorus, should average two or three servings (24 to 30 ounces) a day. More than a quart of milk consumption daily considerably limits the intake of solid foods, resulting in a deficiency of dietary iron and other nutrients. After 2 years of age children can be given no-fat or low-fat milk to reduce daily total fat to less than 30% of calories, saturated fatty acids to less than 10% of calories, and cholesterol to less than 300 mg. Other measures to reduce dietary fat include using lean meats, fat-modified products (such as low-fat cheese), and low-fat cooking. Because less fat in children’s diet can also mean fewer calories and nutrients, caregivers must know what kinds of food to choose. Trans fatty acids and saturated fats, however, should be avoided (Allen and Myers, 2006).

Iron-fortified cereals and iron-rich foods are recommended for all children beyond 6 months of age. Parents should be encouraged to provide an iron-rich diet that includes heme and nonheme iron sources (red meats, poultry, fish, green leafy vegetables, dried fruit, beans) and limit whole-milk consumption. Iron supplementation may be necessary in some cases.

Calcium and vitamin D are essential for healthy bone development. Adequate intake of calcium for the child 1 to 3 years of age is 500 mg. Whole milk, cheese, yogurt, legumes (beans), and vegetables (broccoli, collard greens, kale) are good sources for calcium. Popular calcium-fortified foods include waffles, cereals and cereal bars, orange juice, and some white breads. Adequate vitamin D intake is essential to prevent rickets; it is now recommended that children and adolescents have an intake of at least 200 IU of vitamin D daily. Multivitamin preparations containing 400 IU of vitamin D (by tablet or liquid) are adequate if food intake is poor or exposure to sunlight is minimal; commercially available vitamin D vitamin tablets contain too much vitamin D for children at this time (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003). Sources of vitamin D include fish, fish oils, and egg yolks. Fortified cereals, dairy products, and meat are also good sources of zinc and vitamin E.

It is recommended by the American Heart Association (2005) that toddlers have 1 cup of fruit each day. Vitamin C enhances iron absorption. Toddlers should consume approximately 4 to 6 ounces of juice per day. It tastes good to toddlers and is readily available. A 6-ounce glass of fruit juice equals one fruit serving; however, juices lack the fiber of whole fruit and should not be a substitution for whole fruit. High intake of juice can contribute to diarrhea, overnutrition or undernutrition, and the development of caries; thus only 4 to 6 ounces of 100% fruit juice per day are recommended (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2004a). Fruit-flavored drinks advertised as juices may not actually contain 100% juice and should be avoided.

Fat restriction, other than trans fatty acids and saturated fats, is not appropriate for toddlers. Thirty percent of calories should come from fat. Whole milk is recommended as a source of fat until 2 years of age.

SLEEP AND ACTIVITY

Total sleep decreases only slightly during the second year and averages about 12 hours a day. Most children take one nap a day but may relinquish this habit by the end of the second or third year. Children reach an adult pattern of sleep by 3 years of age (Howard and Wong, 2001).

Sleep problems are common, especially going to bed and falling asleep, and are a response to fears and awareness of separation. Fears can be provoked by a child’s daily stressors such as pressure to toilet train, moves, sibling birth, experiences of loss, or separation from parents. Establishing a regular bedtime and routine is helpful, and providing transitional objects, such as a favorite stuffed animal or blanket, can ease the child’s insecurity at bedtime (see Fig. 12-3). Toddlers no longer sleeping in a crib may come out of their rooms after being put to bed. Limit prolonged bedtime rituals by defining a length of time and set of activities (one more story, one more drink). Toddlers who are too immature to respond to the measures identified may need their doorway gated.

A toddler’s activity level is high, and there is rarely a problem with too little physical exercise, provided inappropriate restrictions are not instituted. With increasing numbers of young children being cared for outside the home, attention to the kinds of activity provided is important. For example, children with high activity levels may benefit from an environment in which outdoor play is encouraged. Neurodevelopment is necessary for the developing child to participate in activities.

DENTAL HEALTH

The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2006) now recommends that every child have an oral health examination by a practitioner by 6 months of age; if the child is in a high-risk category for caries, it is recommended that an initial visit to a dentist or pedodontist (pediatric dentist) occur by age 6 months or within 6 months of the eruption of the first tooth. Every child should have an established dental home by the age of 12 months (American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, 2006). Initial visits to the dentist should be nontraumatizing. Because toddlers react negatively to new and potentially frightening experiences, the initial visit can center around meeting the dentist, seeing the equipment, and sitting in the chair. If the child is cooperative, the dentist may just look at the teeth but reserve a more thorough examination for another visit. Modeling, in which the child observes procedures performed on the parent or a cooperative sibling, can also be effective.

Removal of Plaque

Oral hygiene measures should be implemented according to the suggested schedule noted above to remove plaque, soft bacterial deposits that adhere to the teeth and cause dental caries (decay or cavities) and periodontal (gum) disease. Poor oral hygiene and poor dietary habits are associated with the development of caries in children.

The most effective methods for plaque removal are brushing and flossing. Several brushing techniques exist, although there is no universal agreement regarding the best method. One that is suitable for cleaning the primary teeth is the scrub method. The tips of the bristles are placed firmly at a 45-degree angle against the teeth and gums and moved back and forth in a vibratory motion. The ends of the bristles should be wiggling but not moving forcefully back and forth, which can damage the gums and enamel. All the surfaces of the teeth are cleaned in this manner except the lingual (inner) surfaces of the anterior teeth. To clean these surfaces, the toothbrush is placed vertical to the teeth and moved up and down. Only a few teeth are brushed at one time, using six to eight strokes for each section. A systematic approach is used so that all surfaces are thoroughly cleaned (Fig. 12-7).

FIG. 12-7 Young children can participate in toothbrushing, but parents need to brush all of the child’s teeth thoroughly.

For young children the most effective cleaning is done by parents (Fig. 12-8). Several positions can be used that facilitate access to the mouth and help stabilize the head for comfort:

Stand with child’s back toward adult. (When done in front of a bathroom mirror, both child and adult can see what is being done in the mirror.)

Stand with child’s back toward adult. (When done in front of a bathroom mirror, both child and adult can see what is being done in the mirror.)

Sit on a couch or bed with child’s head resting in adult’s lap.

Sit on a couch or bed with child’s head resting in adult’s lap.

Sit on the floor or a stool with child’s head resting between adult’s thighs.

Sit on the floor or a stool with child’s head resting between adult’s thighs.

With all positions, use one hand to cup the chin and one to brush the teeth. For easier access to back teeth, hold the mouth partially open.

For effective cleaning, a small toothbrush with soft, rounded, multitufted nylon bristles that are short and uniform in length is recommended. Nylon bristles dry more rapidly after use and retain their shape better than natural bristles. Toothbrushes are replaced as soon as the bristles are frayed or bent. With young children, brushing may be more easily accomplished using only water, since many children dislike the foam from toothpaste and the foam interferes with visibility. There is also the danger of swallowing fluoridated toothpaste (see following discussion under Fluoride). Introduce toothpaste around 2 years of age and allow children to select the flavor they like to encourage the brushing habit. Use a pea-sized amount of toothpaste (apply across the narrow width of the toothbrush, rather than along its length, to decrease the chance of applying an excessive amount).

After the teeth have been cleaned, the teeth are flossed to remove plaque and debris from between the teeth and below the gum margin, where brushing is ineffective. Because young children do not have the dexterity to manipulate the dental floss, parents must perform the procedure.

A disclosing agent is helpful in identifying those areas of the teeth where plaque accumulates. It also helps motivate children to clean their teeth because plaque is difficult to see. After cleaning, the mouth is inspected to ensure that all traces of plaque have been removed. Where plaque remains, the teeth are rebrushed.

Ideally, the teeth should be cleaned after each meal and especially before bedtime, and the child should be given nothing to eat or drink after the night brushing except water. At those times when brushing is impractical, the “swish-and-swallow” method of cleaning the mouth is taught: with a mouthful of water the child rinses the mouth and swallows, repeating the procedure three or four times.*

Fluoride

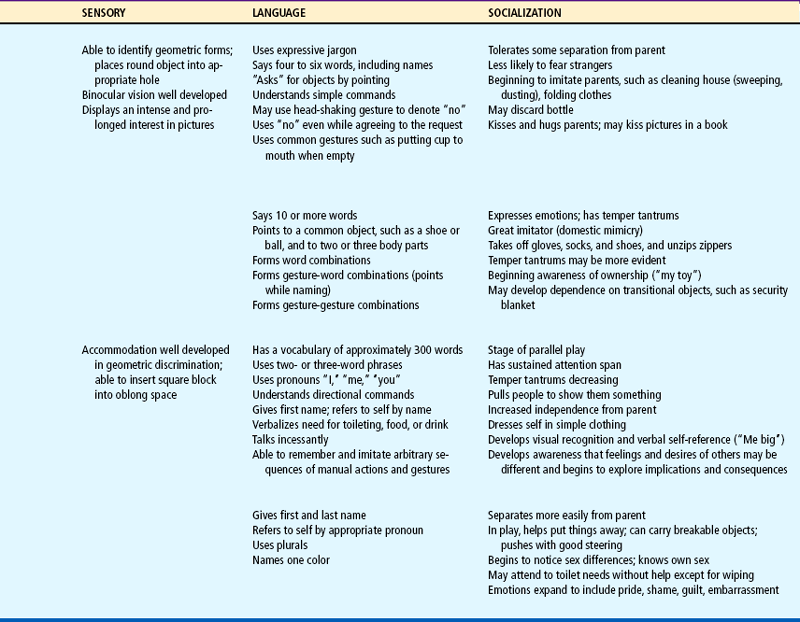

Fluoride supplementation should be considered for any child over the age of 6 months whose drinking water is deficient in fluoride. Supplementation based on fluoride concentration of water supply less than 0.3 ppm (parts per million) is 0.25 mg for a child 6 months to 3 years of age and 0.5 mg for a child 3 to 6 years of age (American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, 2006).

Fluoride, a mineral, is found in water, foods, or drinks in which fluoridated water was used as part of the processing system. Because the water fluoridation process and manufacturing of fluoride toothpaste are almost impossible to standardize in the United States, the dosage of fluoride supplements has been lowered to reduce the incidence of fluorosis (Table 12-2). Increased fluoride ingestion leads to enamel protein retention, hypomineralization of the enamel and dentin, and disturbance of crystal formation. The effects caused by this change range from barely discernible white fiberlike lines or spots to gray-brown stains or pitted areas. Parents should be cautioned against regular use of fluoridated water or beverages such as bottled water containing fluoride if the community water supply already has an adequate amount of fluoride.

TABLE 12-2

Fluoride Supplementation*

From American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Guideline on fluoride therapy. In AAPD reference manual 2005-2006, 2006. ppm, Parts per million.

Low-Cariogenic Diet

Diet is critical to developing good teeth because the carious process depends primarily on fermentable sugars, especially sucrose. Refined table sugar, honey, molasses, corn syrup, and dried fruits such as raisins are highly cariogenic. Complex carbohydrates, such as breads, potatoes, and pasta, also contribute to caries because they lower the plaque pH.

Ideally, highly cariogenic foods, especially those containing complex sugars, should be eliminated. However, because this is impractical, some suggestions can be helpful. First, the frequency with which sugar is consumed is more important than the total amount eaten. Therefore, when sweets are eaten, they are less damaging if consumed immediately after a meal rather than as a snack between meals. When sweets are served as the dessert, the teeth can be cleaned afterward, decreasing the amount of time the sugar is in the mouth.

Second, the form of sugar (sucrose) is important. The more cariogenic foods are those that are sticky or hard, since they remain in the mouth longer. Consequently, sucking on lollipops is more cariogenic than eating a chocolate bar. Sometimes the source of the sugar is “hidden,” as in numerous prescription and nonprescription drugs and in many popular cereals, including the “all-natural” variety. Reading food labels is essential in eliminating sources of sucrose.

Some snacks do not contribute to tooth decay. Aged cheeses, such as cheddar, may alter the pH and retard bacterial growth. Sugarless gum chewed after eating may actually protect against cavities by stimulating saliva that neutralizes acid. The artificial sweeteners saccharin, aspartame, and Splenda are noncariogenic; sorbitol has low cariogenic potential.

A special form of tooth decay in infants and young toddlers is nursing caries (also called nursing bottle caries or bottle-mouth caries), which occurs when the child is routinely given a bottle of milk or juice at nap or bedtime or uses the bottle as a pacifier while awake (Fig. 12-9). The practice of coating pacifiers in honey can also contribute to caries, and honey may be a potential source of botulism in infants (see Chapter 32). As the sweet liquid pools in the mouth, the teeth are bathed for several hours in this cariogenic environment. The maxillary (upper) incisors and molars are affected most, since the mandibular (lower) incisors are protected by the lower lip, tongue, and saliva. Severely decayed teeth may require the application of stainless steel bands to preserve the spacing until the permanent teeth erupt.

Prevention involves eliminating the bedtime bottle completely, feeding the last bottle before bedtime, substituting a bottle of water for milk or juice, not using the bottle as a pacifier, and never coating pacifiers in sweet substances. Juice in bottles, especially commercially available ready-to-use bottles, is discouraged; these beverages are especially damaging because the sugar is more readily converted to acid. Juice should always be offered in a cup to avoid prolonging the bottle-feeding habit. Toddlers should be encouraged to drink from a cup at the first birthday and weaned from a bottle by 14 months of age. Nurses are in an excellent position to counsel parents regarding the dangers of this habit and other aspects of dental care.*

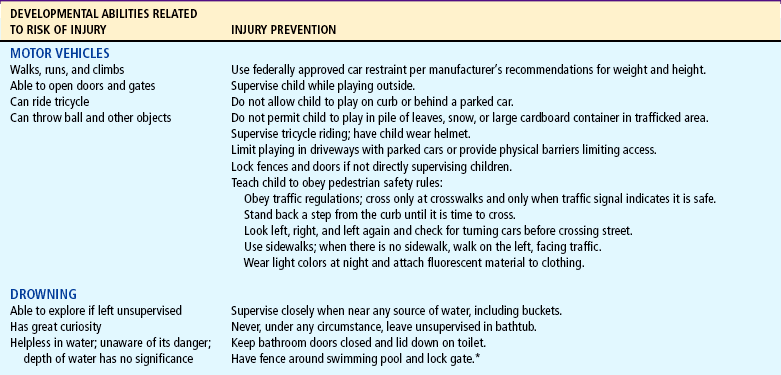

INJURY PREVENTION