Family Influences on Child Health Promotion

On completion of this chapter the reader will be able to:

Discuss definitions of family.

Discuss definitions of family.

Describe three major family theories.

Describe three major family theories.

Identify different family structures found in the United States.

Identify different family structures found in the United States.

Discuss the effect of family size and configuration on personality development.

Discuss the effect of family size and configuration on personality development.

Discuss the role transition experienced by new parents.

Discuss the role transition experienced by new parents.

Explain various parenting behaviors such as parenting styles, disciplinary patterns, and communication skills.

Explain various parenting behaviors such as parenting styles, disciplinary patterns, and communication skills.

Demonstrate an understanding of special parenting situations such as adoption, divorce, single parenting, parenting in reconstituted families, and dual-earner families.

Demonstrate an understanding of special parenting situations such as adoption, divorce, single parenting, parenting in reconstituted families, and dual-earner families.

GENERAL CONCEPTS

The term family has been defined in many different ways according to the individual’s own frame of reference, value judgment, or discipline. There is no universal definition of family; a family is what an individual considers it to be. Biology describes the family as fulfilling the biologic function of perpetuation of the species. Psychology emphasizes the interpersonal aspects of the family and its responsibility for personality development. Economics views the family as a productive unit providing for material needs. Sociology depicts the family as a social unit interacting with the larger society, creating the context within which cultural values and identity are formed. Others define family in terms of the relationships of the persons who make up the family unit. The most common type of relationships are consanguineous (blood relationships), affinal (marital relationships), and family of origin (family unit a person is born into).

Earlier definitions of family emphasized that family members were related by legal ties or genetic relationships and lived in the same household with specific roles. Later definitions have been broadened to reflect both structural and functional changes. A family can be defined as an institution where individuals, related through biology or enduring commitments, and representing similar or different generations and genders, participate in roles involving mutual socialization, nurturance, and emotional commitment (Lerner, Sparks, and McCubbin, 1999).

Considerable controversy has been generated about the newer concepts of family, such as communal families, single-parent families, and homosexual families. To accommodate these and other varieties of family styles, the descriptive term household is frequently used.

Nursing of infants and children is intimately involved with care of the child and the family. Family structure and dynamics can have an enduring influence on a child, affecting the child’s health and well-being (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003). Consequently, nurses must be aware of the functions of the family, various types of family structures, and theories that provide a foundation for understanding the changes within a family and for directing family-oriented interventions.

FAMILY THEORIES

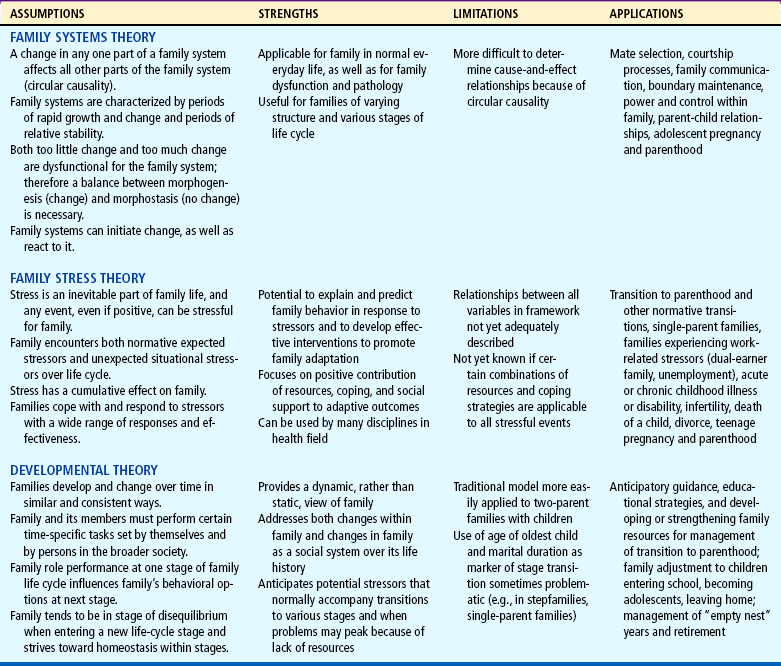

A family theory can be used to describe families and how the family unit responds to events both within and outside the family. Each family theory makes assumptions about the family and has inherent strengths and limitations. Most nurses use a combination of theories in their work with children and families. Commonly used theories are family systems theory, family stress theory, and developmental theory (Table 3-1).

Family Systems Theory

Family systems theory is derived from general systems theory, a science of “wholeness” that is characterized by interaction among the components of the system and between the system and the environment. General systems theory expanded scientific thought from a simplistic view of direct cause and effect (A causes B) to a more complex and interrelated theory (A influences B, but B also affects A). In family systems theory, the family is viewed as a system that continually interacts with its members and the environment. The emphasis is on the interaction between the members; a change in one family member creates a change in other members, which in turn results in a new change in the original member. Consequently, a problem or dysfunction does not lie in any one member but rather in the type of interactions used by the family. Because the interactions, not the individual members, are viewed as the source of the problem, the family becomes the patient and the focus of care. Examples of the application of family systems theory to clinical problems are nonorganic failure to thrive and child abuse. According to family systems theory, the problem does not rest solely with the parent or child but with the type of interactions between the parent and child and the factors that affect their relationship.

The family is viewed as a whole that is different from the sum of the individual members. For example, in a household of parents and one child, there are not only three individuals, but four interactive units. These units include three dyads (the marital relationship, the mother-child relationship, and the father-child relationship) and a triangle (the mother-father-child relationship). The family system functions within a larger system composed of the extended family, the subculture, the culture, and society. This ecologic model of family systems theory places the family dyads in the center of a circle surrounded by the extended family, the subculture, and the culture, with the larger society at the periphery. The concept of nonsummativity—“the whole is greater than the sum of its parts”—implies that the nurse must consider relationships between family members as well as the family’s relationship to its environment. To effect positive change in a family, it is necessary to work with and through the various systems that affect family life.

Another concept, adaptability, views the family as a highly adaptable unit. When problems exist within the family, change occurs by altering the interaction or feedback messages that perpetuate disruptive behavior. Feedback refers to processes in the family that help identify strengths and needs and determine how well goals are accomplished. Positive feedback initiates change; negative feedback resists change. When the family system is disrupted, change can occur at any point in the system. Although family systems theorists pursue the family history to understand current family interaction and problem patterns, the emphasis is on what is occurring now and how to change that pattern. This focus allows for sometimes rapid and dramatic changes.

A major factor that influences a family’s adaptability is its boundary, an imaginary line that exists between the family and its environment. Families have varying degrees of openness and closure in these boundaries. For example, one family has the capacity to reach out for help, whereas another considers help threatening. Knowledge of boundaries is critical when teaching or counseling families. Families with open boundaries may demonstrate a greater receptivity to interventions, whereas families demonstrating closed boundaries often require increased sensitivity and skill on the part of the nurse to gain their trust and acceptance. The nurse who uses family systems theory should assess the family’s ability to accept new ideas, information, resources, and opportunities and to plan strategies.

Family Stress Theory

Family stress theory explains how families react to stressful events and suggests factors that promote adaptation to stress. Families encounter stressors (events that cause stress and have the potential to effect a change in the family social system), including those that are predictable (e.g., parenthood) and those that are unpredictable (e.g., illness, unemployment). These stressors are cumulative, involving simultaneous demands from work, family, and community life. Too many stressful events occurring within a relatively short period (usually 1 year) can overwhelm the family’s ability to cope and place it at risk for breakdown or physical and emotional health problems among its members. When the family experiences too many stressors for it to cope adequately, a state of crisis ensues. For adaptation to occur, a change in family structure or interaction is necessary.

The resiliency model of family stress, adjustment, and adaptation emphasizes that the stressful situation is not necessarily pathologic or detrimental to the family but demonstrates that the family needs to make fundamental structural or systemic changes to adapt to the situation (McCubbin and McCubbin, 1994). For example, bringing a child with special needs to a treatment facility for therapy might be considered a crisis for a family without a car or money for public transportation, but may be defined as only a minor inconvenience by another family with adequate resources.

Developmental Theory

Developmental theory is an outgrowth of several theories of development. Foremost among the developers is Duvall (1977), who described eight developmental tasks of the family throughout its life span (Box 3-1). The family is described as a small group, a semiclosed system of personalities that interacts with the larger cultural social system. As an interrelated system, changes do not occur in one part without a series of changes in other parts.

Developmental theory addresses family change over time using Duvall’s family life cycle stages, based on the predictable changes in the structure, function, and roles of the family, with the age of the oldest child as the marker for stage transition. The arrival of the first child marks the transition from stage I to stage II. As the first child grows and develops, the family enters subsequent stages. In every stage the family faces certain developmental tasks. At the same time, each member of the family must achieve individual developmental tasks as part of each family life cycle stage.

Developmental theory can be applied to nursing practice. For example, the nurse can assess how well new parents are accomplishing the individual and family developmental tasks associated with transition to parenthood. New applications should emerge as more is learned about developmental stages for nonnuclear and nontraditional families.

FAMILY NURSING INTERVENTIONS

In working with children, the nurse must include family members in their care plan. To discover family dynamics, strengths, and weaknesses, a thorough family assessment is necessary (see Chapter 6). When working with families, the nurse’s choice of interventions depends on the theoretic family model that is used (Box 3-2). For example, in family systems theory, the focus is on the interaction of family members within the larger environment. In this case, using group dynamics to involve all members in the intervention process and being a skillful communicator are essential. Systems theory also presents excellent opportunities for anticipatory guidance. Because each family member reacts to every stress experienced by that system, nurses can intervene to help the family prepare for and cope with changes. Each stress point represents an opportunity for change and learning because families are more open to interventions at this time (Brazelton, 1995). In the family stress theory, crisis intervention strategies are employed to help family members cope with the challenging event. In the developmental theory, the nurse provides anticipatory guidance to prepare members for transition to the next family stage.

FAMILY STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

The family structure, or family composition, consists of individuals, each with a socially recognized status and position, who interact with one another on a regular, recurring basis in socially sanctioned ways. When members are gained or lost through events such as marriage, divorce, birth, death, abandonment, or incarceration, the family composition is altered and roles must be redefined or redistributed.

Traditionally, the family structure was either a nuclear or extended family. In recent years, family composition has assumed new configurations, with the single-parent family and blended family becoming prominent forms. The predominant structural pattern in any society depends on the mobility of families as they pursue economic goals and as relationships change. It is not uncommon for children to belong to several different family groups during their lifetime.

Nurses must be able to meet the needs of children from many diverse family structures and home situations. The particular family structure a child participates in affects the direction of nursing care. The U.S. Census Bureau uses four definitions for families: the traditional nuclear family, the nuclear family, the blended family or household, and the extended family or household.

Traditional Nuclear Family

A traditional nuclear family consists of a married couple and their biologic children. Children in this type of family live with both biologic parents and, if siblings are present, only full brothers and sisters (i.e., siblings who share the same two biologic parents). No other persons are present in the household (i.e., no steprelatives, foster or adopted children, half-siblings, other relatives, or nonrelatives).

Nuclear Family

The nuclear family is composed of two parents and their children. The parent-child relationship may be biologic, step, adoptive, or foster. Sibling ties may be biologic, step, half, or adoptive. The parents are not necessarily married. No other relatives or nonrelatives are present in the household.

Blended Family

A blended family or household, also called a reconstituted family, includes at least one stepparent, stepsibling, or half-sibling. A stepparent is the spouse of a child’s biologic parent but is not the child’s biologic parent. Stepsiblings do not share a common biologic parent; the biologic parent of one child is the stepparent of the other. Half-siblings share only one biologic parent. Nurses may have opportunities to interact with blended families in the community.

Extended Family

An extended family or household includes at least one parent, one or more children, and one or more members (related or unrelated) other than a parent or sibling. Parent-child and sibling relationships may be biologic, step, adoptive, or foster.

In many nations and among many ethnic and cultural groups, households with extended families are common. Within the extended family, grandparents often find themselves rearing their grandchildren (Fig. 3-1). In extended families, young parents are often considered too young or too inexperienced to make decisions independently. Often, the older relative holds the authority and makes decisions in consultation with the young parents. Sharing residence with relatives is also beneficial because this arrangement assists with the management of scarce resources and provides child care for working families. A resource for extended families is the Grandparent Information Center.*

Single-Parent Family

In the United States an estimated 21.7 million children lived in single-parent families in 2005 (Annie E Casey Foundation, 2007). The contemporary single-parent family has emerged partially as a consequence of the women’s rights movement and also as a result of more women (and men) establishing separate households because of divorce, death, desertion, or illegitimacy. In addition, a more liberal attitude in the courts has made it possible for single people, both male and female, to adopt children. Although mothers usually head single-parent families, it is becoming more common for fathers to be awarded custody of dependent children in divorce settlements. With the increased psychologic and financial independence of women and the increased acceptability of illegitimacy in society, more unmarried women are deliberately choosing mother-child families. Frequently, these mothers and children are absorbed into the extended family. The challenges of single-parent families are discussed on p. 47.

Binuclear Family

The term binuclear family is used to describe the situation that allows parents to continue the parenting role while terminating the spousal unit. The degree of cooperation between households and the time the child spends with each can vary. In joint custody, the court assigns divorcing parents equal rights and responsibilities concerning the minor child or children. These alternate family forms are efforts on the part of those concerned to view divorce as a process of reorganization and redefinition of a family rather than as a family dissolution. Joint custody and co-parenting are discussed further on p. 47.

Polygamous Family

Although it is not legally sanctioned in the United States, the conjugal unit is sometimes extended by the addition of spouses in polygamous matings. Polygamy refers to either wives (polygyny) or, rarely, husbands (polyandry). Many societies practice polygyny that is further designated as sororal, in which the wives are sisters, or nonsororal, in which the wives are unrelated. Sororal polygyny is widespread throughout the world. Most often, mothers and their children share a husband and father, with each mother and her children living in the same or separate household.

Communal Family

The communal family emerged from disenchantment with most contemporary life choices. Although communal families may have divergent beliefs, practices, and organization, the basic impetus for formation has been dissatisfaction with the nuclear family structure, social systems, and goals of the larger community. Relatively uncommon today, communal groups share common ownership of property. In cooperatives, there is private ownership of property, but certain goods and services are shared and exchanged without monetary consideration. There is strong reliance on group members and material interdependence. Both provide collective security for nonproductive members, share homemaking and childrearing functions, and help overcome the problem of interpersonal isolation or loneliness.

Gay/Lesbian Family

A same-sex, homosexual, or gay/lesbian family is one in which there is a legal or common-law tie between two persons of the same sex who have children. With the social stigma attached to being gay or lesbian, it is difficult to state the number of children of gay or lesbian parents; estimates range from 1 million to 14 million (Ariel and McPherson, 2000; Pawelski, Perrin, Foy, and others, 2006). Although some children in gay/lesbian households are biologic from a former marriage or relationship, there are other circumstances where children may be present. They may be foster or adoptive parents, lesbian mothers may conceive through artificial fertilization, or a gay male couple may become parents through use of a surrogate mother.

Disclosure of parental homosexuality (“coming out”) to children can be a concern for families. There are a number of factors to consider before disclosing this information to children. Parents should be comfortable with their own sexual preference and should discuss this with the children as they become old enough to understand relationships. Discussions should be planned and take place in a quiet setting where interruptions are unlikely. Children should be assured that the parent’s relationship with them will not change as a result of the discussion (Lynch and Murray, 2000).

There are a growing number of families with same-sex parents in the United States, with an estimated one fourth of all same-sex couples raising children (Pawelski, Perrin, Foy, and others, 2006). The gay/lesbian family environment can be as healthy as any other. Nurses need to be nonjudgmental and to learn to accept differences rather than demonstrate a homophobic prejudice that can have a detrimental effect on the nurse-child-family relationship. Moreover, the more knowledge of the child’s family constellation and lifestyle that nurses have, the more help they can provide to the parents and the child.

FAMILY STRENGTHS AND FUNCTIONING STYLE

Family function refers to the interactions of family members, especially the quality of those relationships and interactions. Researchers are interested in family characteristics that help families function effectively. Knowledge of these factors guides the nurse throughout the nursing process, and helps the nurse to predict ways in which families may cope and respond to a stressful event, to provide individualized support that builds on family strengths and unique functioning style, and to assist family members in obtaining resources.

Family strengths and unique functioning styles (Box 3-3) are significant resources that nurses can use to meet family needs. Building on qualities that make a family work well and strengthening family resources make the family unit even stronger. All families have strengths as well as vulnerabilities.

FAMILY ROLES AND RELATIONSHIPS

Each individual has a position, or status, in the family structure and plays culturally and socially defined roles in interactions within the family. Each family also has its own traditions and values and sets its own standards for interaction within and outside the group. Each determines the experiences the children should have, those they are to be shielded from, and how each of these experiences meets the needs of family members. When family ties are strong, social control is highly effective, and most members conform to their roles willingly and with commitment. Conflicts arise when people do not fulfill their roles in ways that meet other family members’ expectations, either because they are unaware of the expectations or because they choose not to meet them.

PARENTAL ROLES

In all family groups the socially recognized status of father and mother exists with socially sanctioned roles that prescribe appropriate sexual behavior and childrearing responsibilities. The guides for behavior in these roles serve to control sexual conflict in society and provide for prolonged care of children. The degree to which parents are committed and the way they play their roles are influenced by a number of variables and by the parents’ unique socialization experience.

Parental role definitions are changing as a result of the changing economy and increased opportunities for women. Women are achieving equality with men in education, more of them have entered the work force, and the number of women who choose to have fewer children or none at all is increasing. As the role of the woman has changed, the complementary role of the man has also changed. Many fathers are taking a more active role in childrearing and household tasks. As the redefinition of sex roles continues in American families, there may be role conflicts in many families because of a cultural lag of the persisting traditional role definitions.

ROLE LEARNING

Roles are learned through the socialization process. During all stages of development children learn and practice, through interaction with others and in their play, a set of social roles and the characteristics of other roles. They behave in patterned and more or less predictable ways because they learn roles that define mutual expectations in typical social relationships. Although role definitions are changing, the basic determinants of parenting remain the same. Several determinants of parenting infants and young children are parental personality and mental well-being, systems of support, and child characteristics. These determinants have been used as consistent measurements to determine a person’s success in fulfilling the parental role.

Parents, peers, authority figures, and other socializing agents who use positive and negative sanctions to ensure conformity to their norms transmit role conceptions. Role behaviors positively reinforced by rewards such as love, affection, friendship, and honors are strengthened. Negative reinforcement takes the form of ridicule, withdrawal of love, expressions of disapproval, or banishment.

In some cultures the role behavior expected of children conflicts with desirable adult behavior. For example, in the United States, children are expected to be submissive in childhood but dominant as adults. This conflict of expectations is known as role discontinuity. Other cultures value the same behaviors, such as courage and aggression, in both children and adults; this provides role continuity.

One responsibility of the family is to develop culturally appropriate role behavior in children. Children learn to perform in expected ways consistent with their position in the family and culture. The observed behavior of each child is a single manifestation—a combination of social influences and individual psychologic processes. In this way the uniting of the child’s intrapersonal system (the self) with the interpersonal system (the family) is simultaneously understood as the child’s conduct.

Role structuring initially takes place within the family unit, in which the children fulfill a set of roles and respond to the roles of their parents and other family members. The roles of the children are shaped primarily by the parents, who apply direct or indirect pressures to induce or force children into the desired patterns of behavior or direct their efforts toward modification of the role responses of the child on a mutually acceptable basis. Parents have their own techniques and determine the course that the process of socialization follows.

Children respond to life situations according to behaviors learned in reciprocal transactions. As they acquire important role-taking skills, their relationships with others change. For instance, when a teenager is also the mother but lives in a household with the grandmother, the teenager may be viewed more as an adolescent than as a mother. Children become proficient at understanding others as they acquire the ability to discriminate their own perspectives from those of others. Children who get along well with others and attain status in the peer group have well-developed role-taking skills.

Family Size and Configuration

Parenting practices differ between small and large families. In small families, more emphasis is placed on the individual development of the children. Parenting is intensive rather than extensive, and there is constant pressure to measure up to family expectations. Children’s development and achievement are measured against those of other children in the neighborhood and social class. In small families, there is more democratic participation by the children than in larger families. Adolescents in small families identify more strongly with their parents and rely more on their parents for advice. They have well-developed, autonomous inner controls as contrasted with adolescents from larger families, who rely more on adult authority.

Children in a large family are able to adjust to a variety of changes and crises. There is more emphasis on the group and less on the individual (Fig. 3-2). Cooperation is essential, often because of economic necessity. The large number of people sharing a limited amount of space requires a greater degree of organization, administration, and authoritarian control. A dominant family member (a parent or older child) wields control. The number of children reduces the intimate, one-to-one contact between the parent and any individual child. Consequently, children turn to each other for what they cannot get from their parents. The reduced parent-child contact encourages individual children to adopt specialized roles to gain recognition in the family.

Older siblings in large families often administer discipline. Siblings are usually attuned to what constitutes misbehavior. Sibling disapproval or ostracism is frequently a more meaningful disciplinary measure than parental interventions. In situations such as death or illness of a parent, an older sibling often assumes responsibility for the family at considerable personal sacrifice. Large families generate a sense of security in the children that is fostered by sibling support and cooperation. However, adolescents from a large family are more peer oriented than family oriented.

Sibling Interactions

Spacing of Children.: Age differences between siblings affect the childhood environment, but to a lesser extent than does the sex of the sibling. The arrival of a sibling is difficult for toddlers and preschool children, especially between the ages of 2 and 3 years old. At this age, they are still very attached to their parents and do not understand the concept of sharing. An older child is able to understand the situation and is less likely to see the newcomer as a threat, although the child does feel the loss of the only-child status. In general, the narrower the spacing between siblings, the more the children influence one another, especially in emotional characteristics. The wider the spacing, the greater the influence of the parents.

Traditionally, sibling relationships were viewed from a Freudian perspective that emphasized the concept of sibling rivalry. Recently, researchers have viewed siblings through developmental or ecologic frameworks that focus on interactions within family systems (Friedman, Bowden, and Jones, 2003). The results of these broader perspectives provide a picture of rich and varied sibling interactions (Fig. 3-3).

Sibling Functions.: The sibling relationship’s most unique feature is its duration. The longest relationship one will share with another human being is the sibling relationship, which lasts through a lifetime (often 50 to 80 years), compared with the child-parent relationship of approximately 30 to 50 years. Siblings spend long periods together and get to know each other at their best and worst.

Siblings exert power, exchange services, and express feelings in reciprocal ways that are often not revealed in the presence of the parents. They see themselves in their brother or sister, experience life vicariously through their sibling’s behavior, and begin to expand on their own possibilities. Siblings can also be touchstones for what the other would not like to be, and they use each other as yardsticks for comparison. They provide a sounding board for each other and offer a safe forum for experimenting with new behaviors and roles. Brothers and sisters provide each other with tangible services (e.g., lending money, clothing, toys, or sports equipment; teaching a skill), help each other with childhood problems, provide support in dealing with parents or others outside the family, and provide introductions to new friendship groups. Children learn to negotiate and bargain, and sometimes to manipulate, from their siblings. Their interactions with each other provide opportunities for conflict and conflict resolution. They protect one another from parental-executive abuse of power and can form a coalition to deal with the issues of authority, power, and emotional support. Negotiating with parents is stronger when siblings act together rather than singly.

Siblings interpret the outside world for each other and perform educative functions for the parents. A related function is pioneering, in which one sibling initiates a process, thereby giving the others permission to follow. These patterns include breaking explicit family rules, taking new pathways (such as leaving the family), or adopting different moral or political codes and lifestyles.

Tattling can be an important lever in sibling interactions. On the other hand, there is often a conspiracy of silence among siblings, leaving the parents feeling isolated and excluded. A willingness to maintain each other’s privacy often serves as a powerful bond of loyalty that distinguishes the relationship between siblings from that between friends.

More Active Sibling Relationships.: Sibling relationships vary among cultures. Some factors may be giving the sibling relationship greater significance in American families than in the past. Shrinking family size, longer life spans, divorce and remarriage, geographic mobility, maternal employment, alternative sources of child care, competitive pressures, stress, and parental insufficiency may be propelling siblings into greater contact and emotional interdependence than ever before. Siblings often join forces to confront the trauma of divorce, and they frequently rely on each other for support when parents remarry. The large number of working mothers means that young siblings today have significant amounts of time when a personally committed adult does not monitor their relationship. Often an older sibling is required to baby-sit, resulting in children spending more and more time together unsupervised. In a worried, mobile, small-family, high-stress, fast-paced, parent-absent society, children often turn to a brother or sister to meet their needs for contact, constancy, and permanency.

Ordinal Position

Researchers have observed that the birth position of children affects their personalities. Parents treat children differently, and sibling interactions are different, depending on the child’s position within the family. Power is unequally distributed among siblings. Older siblings attempt to dominate younger ones. Therefore younger siblings develop interpersonal skills, the ability to negotiate, and an ability to accept unfavorable outcomes to a greater extent than older siblings. Later-born children are obliged to interact with other siblings from birth and seem to be more outgoing and make friends more easily than firstborns. Children vary tremendously, and generalizations do not always apply to the individual. General characteristics of children in the various ordinal positions are presented in Box 3-4.

The Only Child.: Being the only child in a family has traditionally been considered a disadvantage. Only children have been described as selfish, spoiled, dependent, and lonely. However, they do not demonstrate more evidence of maladjustment or self-centeredness than other children and tend to strongly resemble firstborn children in respects such as higher educational goals. Only children perform better on cognitive tests, are more mature, are more socially sensitive, and demonstrate superiority in language facility compared with other children.

Only children also enjoy the advantage of having parents who can devote more time to them, talk to them, and stimulate them in intellectual activities. However, parents also exert greater pressure for mature behavior at an early age and for achievement. Relative isolation from peers contributes to intellectual pursuits and encourages a rich fantasy life, independence, and originality.

Multiple Births

A deviation in early development that occurs with variable frequency is multiple births. Twins are not uncommon in the population, but triplets are rare and quadruplets or quintuplets are extremely unusual. In any of these situations, the offspring can be of the like or unlike sex (i.e., derived from a single ovum; from multiple ova; or from a combination of the two, which can involve one or more cell divisions). The cause of twinning is unknown, but the increase in the number of larger multiples (quintuplets, sextuplets) during recent years has been associated with fertility treatments such as ovulation-inducing drugs or in vitro fertilization. Because women in their thirties are almost 2.5 times as likely as women in their twenties to have higher-order plural births, the rise in the multiple-birth ratio has been associated with increased childbearing among older women and the expanded use of fertility drugs (Hamilton, Minino, Martin, and others, 2007).

Twins are of two distinct types: identical, or monozygotic (MZ), and fraternal (Fig. 3-4), or dizygotic (DZ) (Box 3-5). In 2004 in the United States the overall rate of twin birth was 32.2 per 1000 births, a record high (Hamilton, Minino, Martin, and others, 2007); one third are MZ twins, and two thirds are DZ twins.

A special kind of sibling relationship is observed in twins, although getting along with each other and quarreling are not much different from these behaviors in any other two siblings, especially if they are different-sex fraternal twins. Twins tend to work out a relationship that is reasonably satisfactory to both and demonstrate early independence from parental attention. They develop a remarkable capacity for cooperative play and considerable loyalty and generosity toward each other. It is not uncommon for them to evolve a private language between themselves that may interfere with the development of the family language.

In a twinship, one member of the pair, to a greater or lesser extent, is more dominant, outgoing, and assertive than the other, often to the consternation of their parents. However, the seemingly more passive twin is able to accomplish as much and get his or her way as frequently as the more assertive twin.

Researchers have also observed a difference in behavior between identical and fraternal twins. There is near-unison in the actions of identical twins (although they alternate in assuming the leadership), but fraternal twins, even of the same sex, do not display this quality. Sibling rivalry can be pronounced in fraternal twins, especially in different-sex twins.

Identical twins also differ in their response to the tendency of some parents to treat twins exactly alike. The present philosophy is to determine the degree to which the children demonstrate an inclination toward togetherness. Some twins thrive best when they are constantly in each other’s company; others prefer more individuality and separateness. The conservative approach is to allow the children to follow their natural inclinations. Early years of togetherness are often the basis of the children’s security, and separating them too early may produce unnecessary stresses. Fostering individual differences as they become evident could ease the process of separation when it becomes advisable.

Parental Adjustment.: The entrance of any new member into a household creates stress, but with multiple births two or more new members must be incorporated into the family at the same time. The problems are obvious. Two infants must be provided with physical care, including feeding, diapering, and all of the purchasing and preparation that accompanies the care of any infant. Scheduling becomes crucial, and advancement in development brings new problems and adjustments (e.g., space and sleeping arrangements, selection of a stroller and other equipment). Care must be observed in selecting toys. As play becomes a serious business, some toys that would be safe and appropriate for a single child become weapons when two infants share a playpen. It is a good idea to select different toys for each child as they grow older and encourage sharing.

It is especially important for parents to maintain relationships with each other and other family members. It is doubly important for parents to arrange time together as often as possible. The National Organization of Mothers of Twins Clubs, Inc.,* has local chapters throughout the United States to offer information and support to parents of twins and is highly recommended as a resource for all new parents of twins. Twins Magazine† is a place to seek and give advice about parenting multiples.

PARENTING

A dominant characteristic in all societies is that adults are expected to become parents and to be gratified by the experience. Pressures of tradition, sentiment regarding the state of parenthood, and religious beliefs influence decision making because conformity to social-role expectations is a strong influence in family planning.

Factors that influence family size are social class, religion, race, financial stability, type of conjugal-role relationships, and the social-psychologic aspects of sexual relations. In the case of divorce and remarriage, an individual may decide to have more children with the new spouse.

PREPARATION FOR PARENTHOOD

The basic goals of parenting are to promote the physical survival and health of children, to foster the skills and abilities necessary to be a self-sustaining adult, and to foster behavioral capabilities for optimizing cultural values and beliefs. However, new parents often approach parenthood with limited experience and knowledge. Parents learn by trial and error, committing the same mistakes committed by countless other parents, but they somehow manage to accomplish the task, becoming more skilled with each additional child. Tradition, rather than rational planning, furnishes the chief norms for childrearing. Experience in having been nurtured as a child is an essential component of successful parenting.

Their own parents are probably the only persons whom parents observe intimately in the parental role. This results in a generational continuity—parents rear their own children in much the same way as they themselves were reared. Other essential skills that parents need to feel comfortable in the parenting role include a basic understanding of childhood growth and development, bathing, feeding, use of play, and interpersonal communication skills.

TRANSITION TO PARENTHOOD

Although experts disagree as to whether the birth of the first child should be labeled a crisis, the early weeks of an infant’s life call for parents to make drastic adjustments. Even though the parents have anticipated and prepared for the child’s arrival, the birth presents the challenge of providing total care 24 hours a day for a new member of the family. A crisis may occur if the event is perceived as disturbing old habits and relationships and eliciting new responses. The birth requires role changes or significantly modifies former relationships. In addition to the roles of husband and wife, the couple must assume the roles of father and mother.

The advent of a new family member requires that the family cope with greater financial responsibilities, a possible loss of income, changes in sleeping habits, and less time for the parents to spend with each other (especially if it is a firstborn) and with other children. If these events are perceived as aversive, it can disrupt the couple’s bond and reduce the couple’s intimacy and affection.

Parental Factors Affecting Transition to Parenthood

No amount of preparation can fully prepare prospective parents for the constant and immediate needs of an infant. The importance of early parent-infant interactions is addressed in the discussion of the neonate, especially the attachment process (see Chapter 8). Factors affecting parenting are the age of the parents, the quality of the parental relationship, the amount of previous experience with childrearing, parental support systems, and the effects of stress on parental behavior.

Parental Age.: From a physiologic health perspective, the most satisfactory ages for childbearing are the years between 18 and 35. During this time, parents are considered to be in optimum health, with a predicted life span that allows sufficient time and vigor to raise a family. However, the age at which parents begin their families has changed over the past few decades in the United States, with a substantial increase in the birth rate for women 30 to 44 years of age and a decline for women ages 20 to 29 years.

Father Involvement.: Current practices that encourage early father-infant interaction indicate that fathers are as intrigued with their newborns as mothers are (see discussion on paternal engrossment under Promote Parent-Infant Bonding [Attachment], Chapter 8). Even fathers who have little initial contact with their newborn become involved with them over the next few months (Fig. 3-5), although the type of interaction is different from that of the mother. For example, mothers are more likely to hold, soothe, care for, or play quietly with their infants, whereas fathers are more boisterous and engage in more physically stimulating activities. However, fathers are more than just playmates. They are often successful at soothing a distressed infant. A secure attachment to the father can help offset the consequences of an insecure attachment to the mother.

Parenting Education.: First-time parents who have prepared themselves to be parents experience less stress adjusting to the birth of new baby than those who have not. Programs designed to take place near the time of birth or soon after can be more helpful in easing transitional stress than programs that take place earlier.

Many parents are looking for ways to be a better parent. Nurses can offer a number of suggestions: being an active listener, having an active role in education, keeping up with technology, keeping up with regular visits to the child’s health care provider and vaccinations, ensuring safety in and out of the home, spending quality time with the child, and focusing on improving overall family communication (Fig. 3-6).

Other factors influencing the transition to the parental role include the following:

Parents with previous experience, such as another child, appear to be more relaxed, have less conflict in disciplinary relationships, and are more aware of normal growth and development.

Parents with previous experience, such as another child, appear to be more relaxed, have less conflict in disciplinary relationships, and are more aware of normal growth and development.

The amount of stress experienced by one or both parents may interfere with their ability to exhibit patience and understanding and to cope with their children’s behavior.

The amount of stress experienced by one or both parents may interfere with their ability to exhibit patience and understanding and to cope with their children’s behavior.

Special characteristics of the infant, such as being temperamentally difficult, can cause the parents to lose confidence and doubt their abilities. Infants with special care needs (such as those associated with a disability) can be a significant source of added stress.

Special characteristics of the infant, such as being temperamentally difficult, can cause the parents to lose confidence and doubt their abilities. Infants with special care needs (such as those associated with a disability) can be a significant source of added stress.

Stressed marital relationships can have a negative effect on parental transition because marital tension can alter caregiving routines and interfere with enjoyment of the infant. Conversely, parents’ support and encouragement of one another serve as positive influences on establishing a satisfying parental role.

Stressed marital relationships can have a negative effect on parental transition because marital tension can alter caregiving routines and interfere with enjoyment of the infant. Conversely, parents’ support and encouragement of one another serve as positive influences on establishing a satisfying parental role.

Support Systems.: Successful adaptation to the stress of transition to parenthood involves at least two types of family resources (McCubbin and McCubbin, 1994). Internal resources such as adaptability and integration are the first type of resource. Changing from an orderly, predictable life to a relatively disordered, unpredictable one is a universal adaptation that families must make. Rigid schedules are impossible to maintain, and former activities must be curtailed or abandoned. Adaptation is reflected in learning to be patient, becoming better organized, and becoming more flexible. Integration refers to the couple’s attempt to continue some activities they engaged in before they became parents. In this way couples are able to maintain a sense of continuity and appreciate the importance of the husband-wife relationship.

The second resource for coping with stress is the use of coping strategies that strengthen the organization and functioning of the family. These include the use of social support systems and community resources and the adoption of a future orientation. Interpersonal supports that provide information, advice, and caretaking can be derived from friends, relatives, and neighbors. Relationships with family, friends, and community are essential. For parents, positive, supportive work relationships are important. Equally important is time spent with friends. Arranging for time away from the child or children is also beneficial. One parent can assume care of the family to allow the other parent some time to himself or herself. Adoption of a future orientation provides reassurance to parents that things will get better, that they will cope, and that it is realistic to plan for the time when they will be able to engage in self-fulfilling activities.

It is also reassuring to know that others experience ambivalent feelings toward parenthood and share the same difficulties and frustrations. Exchanging ideas and experiences with other parents and each other provides an opportunity to voice concerns and to learn new ways to cope with multiple childrearing problems (Fig. 3-7).

PARENTING BEHAVIORS

Parenting styles can be described as authoritarian, permissive, or authoritative. Authoritarian or dictatorial parents try to control their children’s behavior and attitudes through unquestioned mandates. They establish rules and regulations or standards of conduct that they expect to be followed rigidly and unquestioningly. They value and reward absolute obedience, mute acceptance of their word, and unfailing respect for the family’s principles and beliefs. They forcefully punish any behavior that is contrary to parental standards. Parental authority is exercised with little explanation and little involvement of the child in decision making. The message is: “Do it because I say so.”

Punishment need not be corporal but may be stern withdrawal of love and approval. Careful training often results in rigidly conforming behavior in the children, who tend to be sensitive, shy, self-conscious, retiring, and submissive. They are more apt to be courteous, loyal, honest, and dependable but docile. These behaviors are more typically observed when close supervision and affection accompany parental authority. If not, this style of parenting may be associated with both defiant and antisocial behavior.

Permissive or laissez-faire parents exert little or no control over their children’s actions. They avoid imposing their own standards of conduct and allow their children to regulate their own activity as much as possible. These parents consider themselves to be resources for the children, not role models. If rules do exist, the parents explain the underlying reason, elicit the children’s opinions, and consult them in decision-making processes. They employ lax, inconsistent discipline; do not set sensible limits; and do not prevent the children from upsetting the home routine. These parents rarely punish the children. Consequently, the children control the parents and are often disobedient, disrespectful, and generally defiant of authority.

Authoritative or democratic parents combine practices from both of the previously described parenting styles. They direct their children’s behavior and attitudes by emphasizing the reason for rules and negatively reinforcing deviations. They respect the individuality of each child and allow the child to voice objections to family standards or regulations. Parental control is firm and consistent but tempered with encouragement, understanding, and security. Control is focused on the issue, not on withdrawal of love or the fear of punishment. These parents foster “inner-directedness,” a conscience that regulates behavior based on feelings of guilt or shame for wrongdoing, not on fear of being caught or punished. Parents’ realistic standards and reasonable expectations produce children with high self-esteem who are self-reliant, assertive, inquisitive, content, and highly interactive with other children.

There are differing philosophies in regard to parenting. Childrearing is a culturally bound phenomenon, and children are socialized to behave in ways that are important to their family. In the authoritative style, authority is shared and children are included in discussions, fostering an independent and assertive style of participation in family life. When working with individual families, nurses should give these differing styles equal respect.

LIMIT SETTING AND DISCIPLINE

In its broadest sense, discipline means to teach or refers to a set of rules governing conduct. In a narrower sense, it refers to the action taken to enforce the rules after noncompliance. Limit setting refers to establishing the rules or guidelines for behavior. For example, parents can place limits on the amount of time children spend watching television or chatting online. The clearer the limits that are set and the more consistently they are enforced, the less need there is for disciplinary action.

Nurses can help parents establish realistic and concrete “rules.” Limit setting and discipline are positive, necessary components of childrearing and serve several useful functions as they help children:

Achieve in areas appropriate for mastery at their level

Achieve in areas appropriate for mastery at their level

Channel undesirable feelings into constructive activity

Channel undesirable feelings into constructive activity

Children want and need limits. Unrestricted freedom is a threat to their security and safety. Through testing the limits imposed on them, children learn the extent to which they can manipulate their environment and gain reassurance from knowing that others are there to protect them from potential harm.

Minimizing Misbehavior

The reasons for misbehavior may include attention, power, defiance, and a display of inadequacy (e.g., the child misses classes because of a fear that he or she is unable to do the work). Children may also misbehave because the rules are not clear or consistently applied. Acting out behavior, such as a temper tantrum, may represent uncontrolled frustration, anger, depression, or pain. The best approach is to structure interactions with children so that unacceptable behavior is prevented or minimized (see Family-Centered Care box).

General Guidelines for Implementing Discipline

Regardless of the type of discipline used, certain principles are essential to ensure the efficacy of the approach (see Family-Centered Care box). Many strategies, such as behavior modification, can only be implemented effectively when principles of consistency and timing are followed. A pattern of intermittent or occasional enforcement of limits actually prolongs the undesired behavior because children learn that if they are persistent, the behavior is permitted eventually. Delaying punishment weakens its intent, and practices such as telling the child, “Wait until your father comes home,” are not only ineffectual, but also convey negative messages about the other parent.*

Types of Discipline

To deal with misbehavior, parents need to implement appropriate disciplinary action. Many approaches are available. Reasoning involves explaining why an act is wrong and is usually appropriate for older children, especially when moral issues are involved. However, young children cannot be expected to “see the other side” because of their egocentrism. Children in the preoperative stage of cognitive development (toddlers and preschoolers) have a limited ability to distinguish between their point of view and those of others. Sometimes children use “reasoning” as a way of gaining attention. For example, they may misbehave thinking the parents will give them a lengthy explanation of the wrongdoing and knowing that negative attention is better than no attention. When children use this technique, parents should end the explanation by stating, “This is the rule, and this is how I expect you to behave. I won’t explain it any further.”

Unfortunately, reasoning is often combined with scolding, which sometimes takes the form of shame or criticism. For example, the parent may state, “You are a bad boy for hitting your brother.” Children take such remarks seriously and personally, believing that they are bad.

Positive and negative reinforcement is the basis of behavior modification theory—behavior that is rewarded will be repeated; behavior that is not rewarded will be extinguished. Using rewards is a positive approach. By encouraging children to behave in specified ways, the parents can decrease the tendency to misbehave. With young children, using paper stars is an effective method. For older children, the “token system” is appropriate, especially if a certain number of stars or tokens yields a special reward, such as a trip to the movies or a new book. In planning a reward system, the parents must explain expected behaviors to the child and establish rewards that are reinforcing. A chart should be used to record the stars or tokens, and an earned reward should be given promptly. Verbal approval should always accompany extrinsic rewards.

Consistently ignoring behavior will eventually extinguish or minimize the act. Although this approach sounds simple, it is often difficult to implement consistently. Parents frequently “give in” and resort to previous patterns of discipline. Consequently, the behavior is actually reinforced because the child learns that persistence gains parental attention. For ignoring to be effective, parents should (1) understand the process, (2) record the undesired behavior before using ignoring to determine whether a problem exists and to compare results after ignoring is begun, (3) determine whether parental attention acts as a reinforcer, and (4) be aware of “response burst.” Response burst is a phenomenon that occurs when the undesired behavior increases after ignoring is initiated because the child is “testing” the parents to see if they are serious about the plan.

The strategy of consequences involves allowing children to experience the results of their misbehavior. It includes three types:

Natural—Those that occur without any intervention, such as being late and missing dinner

Logical—Those that are directly related to the rule, such as not being allowed to play with another toy until the used ones are put away

Unrelated—Those that are imposed deliberately, such as no playing until homework is completed or the use of time-out

Natural or logical consequences are preferred and effective if they are meaningful to children. For example, the natural consequence of living in a messy room may do little to encourage cleaning up, but allowing no friends over until the room is neat can be motivating! Withdrawing privileges is often an unrelated consequence. After the child experiences the consequence, the parent should refrain from any comment, because the usual tendency is for the child to try to place blame for imposing the rule.

Time-out is actually a refinement of the common practice of “sending the child to his or her room” and is a type of unrelated consequence. It is based on the premise of removing the reinforcer (i.e., the satisfaction or attention the child is receiving from the activity). When placed in an unstimulating and isolated place, children become bored and consequently agree to behave in order to reenter the family group (Fig. 3-8). Time-out avoids many of the problems of other disciplinary approaches. No physical punishment is involved; no reasoning or scolding is given; and the parent does not need to be present for all of the time-out, thus facilitating his or her ability to consistently apply this type of discipline. Time-out offers both the child and the parent a “cooling off” time. To be effective, however, time-out must be planned in advance (see Family-Centered Care box).

Corporal or physical punishment most often takes the form of spanking. Based on the principles of aversive therapy, inflicting pain through spanking causes a dramatic short-term decrease in the behavior. However, there are serious flaws in this approach: (1) it teaches children that violence is acceptable; (2) it may physically harm the child if it is the result of parental rage; and (3) children become “accustomed” to spanking, requiring more severe corporal punishment each time. Spanking can result in severe physical and psychologic injury, and it interferes with effective parent-child interaction. In addition, when the parent is not around, the misbehavior is likely to occur, since children have not learned to behave well for their own sake. Parental use of corporal punishment may also interfere with the child’s development of moral reasoning.

SPECIAL PARENTING SITUATIONS

Parenting is a demanding task under the most ideal circumstances, but when parents and children are faced with situations that deviate from what is considered the norm, the potential for family disruption is increased. Situations that are encountered frequently are divorce, single parenthood, blended families, adoption, and dual-career families. In addition, as cultural diversity increases in our communities, many immigrants are making the transition to parenthood and a new country, culture, and language simultaneously. Other situations that create unique parenting challenges are parental alcoholism, homelessness, and incarceration. Although these topics are not addressed here, the reader may wish to investigate them further.

PARENTING THE ADOPTED CHILD

Adoption establishes a legal relationship between a child and parents who are not related by birth, but who have the same rights and obligations that exist between children and their biologic parents. In the past the biologic mother alone made the decision to relinquish the rights to her child. In recent years the courts have acknowledged the legal rights of the biologic father regarding this decision. Concerned child advocates have questioned whether decisions that honor the father’s rights are in the best interests of the child. As the rights of the child have become recognized, older children have successfully dissolved their legal bond with their biologic parents to pursue adoption by adults of their choice. Furthermore, there is a growing interest and demand within the gay and lesbian community to adopt.

Unlike biologic parents, who prepare for their child’s birth with prenatal classes and the support of friends and relatives, adoptive parents have few sources of support and preparation for the new addition to their family. Nurses can provide the information, support, and reassurance needed to reduce parental anxiety regarding the adoptive process and refer adoptive parents to state parental support groups. Such sources can be contacted through a state or county welfare office.

Most problems faced by adoptive parents are not different from those encountered by natural parents, but the desire to be a good parent is often intensified in adoptive parents. Adoptive parents have been portrayed as more apprehensive, insecure, and in need of more assistance than biologic parents. However, some adoptive parents may actually need less assistance than biologic parents. This situation may be related to the adoptive parents’ completely voluntary decision to become parents, the relatively long time they have to prepare for parenting, and the maturity associated with adopting.

The sooner infants enter their adoptive home, the better the chances of parent-infant attachment. However, the more caregivers the infant has had before adoption, the greater the risk for attachment problems. The infant must break the bond with the previous caregiver and form a new bond with the adoptive parents. Difficulties in forming an attachment depend on the amount of time the infant has spent with earlier caregivers (e.g., the birth mother, nurse, adoption agency personnel).

Siblings, adopted or biologic, who are old enough to understand should be included in decisions regarding the commitment to adopt, with reassurance that they are not being replaced. Ways that the siblings can interact with the adopted child should be stressed (Fig. 3-9).

Issues of Origin

The task of telling children that they are adopted can be a cause of deep concern and anxiety. There are no clear-cut guidelines for parents to follow in determining when and at what age children are ready for the information. Parents are naturally reluctant to present the children with such potentially unsettling news. However, it is important that parents not withhold the adoption from the child, since it is an essential component of the child’s identity (see Critical Thinking Exercise).

The timing arises naturally, as parents become aware of the child’s readiness. Most authorities believe that children should be informed at an age young enough so that, as they grow older, they do not remember a time when they did not know they were adopted. The time is highly individual, but must be right for both the parents and the child. It may be when children ask where babies come from, at which time children can also be told the facts of their adoption. If they are told in a way that conveys the idea that they were active participants in the selection process, they will be less likely to feel that they were abandoned victims in a helpless situation. For example, parents can tell children that their personal qualities drew the parents to them. It is wise for parents who have not previously discussed adoption to tell children that they are adopted before the children enter school to avoid third parties inadvertently telling the children before the parents have had the opportunity to do so. Complete honesty between parents and children strengthens the relationship.

Parents should anticipate behavior changes after the disclosure, especially in older children. Children who are struggling with the revelation that they are adopted may benefit from individual and family counseling. Children may use the fact of their adoption as a weapon to manipulate and threaten parents. Statements such as “My real mother would not treat me like this” or “You don’t love me as much because I’m adopted” hurt parents and increase their feelings of insecurity. Such statements may also cause parents to become overpermissive. Adopted children need the same undemanding love, combined with firm discipline and limit setting, as any other child.

Adolescence

Adolescence may be an especially trying time for parents of adopted children. The normal confrontations of adolescents and parents assume more painful aspects in adoptive families. Adolescents may use their adoption to defy parental authority or as a justification for aberrant behavior. As they attempt to master the task of identity formation, the feeling of abandonment by their biologic parents comes into awareness and may be intensified. Gender differences in reacting to adoption may surface.

Adopted children fantasize about their biologic parents and may feel the need to discover their parents’ identity to define themselves and their own identity. It is important for parents to keep the lines of communication open and to reassure their child that they understand the need to search for their identity. In some states, birth certificates are made legally available to adopted children when they come of age. It is important for parents to be honest with questioning adolescents and to tell them of this possibility (the parents themselves are unable to obtain the birth certificate; it is the children’s responsibility if they desire it).

Cross-Racial and International Adoption

Adoption of children from racial backgrounds different from that of the family is commonplace. In addition to the problems faced by adopted children in general, children of a cross-racial adoption must deal with physical and sometimes cultural differences. It is advised that parents who adopt such children do everything to preserve the adopted children’s racial heritage.

Although the children are full-fledged members of an adopting family and citizens of the adopted country, if they have a strikingly different appearance from other family members or exhibit distinct racial or ethnic characteristics, challenges may be encountered outside the family. Bigotry may appear among relatives and friends. Strangers may make thoughtless comments and talk about the children as though they were not members of the family. It is vital that family members declare to others that this is their child and a cherished member of the family.

In international adoptions the medical information the parents receive may be incomplete or sketchy; weight, height, and head circumference are often the only objective information present in the child’s medical record. Many internationally adopted children were born preterm, and common health problems such as infant diarrhea and malnutrition delay growth and development. Some children have serious or multiple health problems that can be very stressful for the parents.

PARENTING AND DIVORCE

Since the mid-1960s, a marked change in the stability of families has been reflected in increased rates of divorce, single parenthood, and remarriage. In 2005 the divorce rate for the United States was 3.8 per 1000 total population (Munson and Sutton, 2006). The divorce rate has changed little since 1987. In the previous decade, the rate increased yearly, with a peak in 1979. Although almost half of all divorcing couples are childless, it is estimated that more than 1 million children experience divorce each year.

The process of divorce begins with a period of marital conflict of varying length and intensity, followed by a separation, the actual legal divorce, and the reestablishment of different living arrangements (Box 3-6). Because a function of parenthood is to provide for the security and emotional welfare of children, disruption of the family structure often engenders strong feelings of guilt in the divorcing parents.

During a divorce, parents’ coping abilities may be compromised. The parents may be preoccupied with their own feelings, needs, and life changes and unable to be available and supportive to their children. Newly employed parents, usually mothers, are likely to leave children with new caregivers, in strange settings, or alone after school. The parent may also spend more time away from home, searching for or establishing new relationships. Sometimes, however, the adult feels frightened and alone and begins to depend on the child as a substitute for the absent parent. This dependence places an enormous burden on the child.

Common characteristics in the custodial household after separation and divorce include disorder, coercive types of control, inflammable tempers in both parents and children, reduced parental competence, a greater sense of parental helplessness, poorly enforced discipline, and diminished regularity in enforcing household routines. Noncustodial parents are seldom prepared for the role of visitor, may assume the role of recreational and “fun” parent, and may not have a residence suitable for children’s visits. They may also be concerned about maintaining the arrangement over the years to follow.

Impact of Divorce on Children

Numerous studies indicate that divorce has a profound effect on children. Many youngsters suffer for years from psychologic and social difficulties associated with continuing or new stresses in the postdivorce family. Even when a divorce is amicable and open, children recall parental separation with the same emotions felt by victims of a natural disaster: loss, grief, and vulnerability to forces beyond their control.

The impact of divorce on children depends on several factors, including the age and sex of the children, the outcome of the divorce, and the quality of the parent-child relationship and parental care during the years following the divorce. Family characteristics are more crucial to the child’s well-being than specific child characteristics, such as age or sex. High levels of ongoing family conflict are related to problems of social development, emotional stability, and cognitive skills for the child.

Complications associated with divorce include efforts on the part of one parent to subvert the child’s loyalties to the other, abandonment to other caregivers, and adjustment to a stepparent. A major problem occurs when children are “caught in the middle” between the divorced parents. They become the message bearer between the parents, are often quizzed about the activities of the other parent, and have to listen to one parent criticize the other. A nurse may be able to intercede by helping the child get out of the middle by stating “I messages” based on the formula of “I feel … (state the feeling) when you … (state the source). I would like it if you ….” This approach empowers the child to feel in control. An example of an “I message” is: “I do not feel comfortable when you ask me questions about mom; maybe you could ask her yourself.”

Feelings of children toward divorce vary with age (Box 3-7). Some children feel a sense of shame and embarrassment concerning the family situation. Some feelings cause children to see themselves as different, inferior, or unworthy of love, especially if they feel responsible for the family dissolution. Although the social stigma attached to divorce no longer produces the emotions it did in the past, such feelings may still exist in small towns or in some cultural groups and can reinforce children’s negative self-image. The lasting effects of divorce depend on the children’s and the parents’ adjustment to the transition from an intact family to a single-parent family and, often, to a reconstituted family.

Although most studies have concentrated on the negative effects of divorce on youngsters, some positive outcomes of divorce have been reported. A successful postdivorce family, either a single-parent or a reconstituted family, can improve the quality of life for both adults and children. If conflict is resolved, a better relationship with one or both parents may result, and some children may have less contact with a disturbed parent. Greater stability in the home setting and the removal of arguing parents can be a positive outcome for the child’s long term well-being.

Age- and Sex-Related Responses to Divorce.: Previously, it was believed that divorce had a greater impact on younger children, but recent observations indicate that divorce constitutes a major disruption for children of all ages. The feelings and behaviors of children may be different for various ages and gender, but all children suffer stress second only to the stress produced by the death of a parent. Although considerable research has looked at sex differences in children’s adjustments to divorce, the findings are not conclusive.

Telling the Children.: Parents are understandably hesitant to tell children about their decision to divorce. Most parents neglect to discuss either the divorce or its inevitable changes with their preschool child. Without preparation, even children who remain in the family home are confused by the parental separation. Frequently, children are already experiencing vague, uneasy feelings that are more difficult to cope with than being told the truth about the situation. If possible, the initial disclosure should include both parents and siblings, followed by individual discussions with each child. Sufficient time should be set aside for these discussions, and they should take place during a period of calm, not after an argument. Parents who physically hold or touch their children provide them with a feeling of warmth and reassurance. The discussions should include the reason for the divorce (if age appropriate) and reassurance that the divorce is not the fault of the children.

Parents should not fear crying in front of the children, because their crying gives the children permission to cry also. Children need to ventilate their feelings. Children may feel guilt, a sense of failure, or that they are being punished for misbehavior. They normally feel anger and resentment and should be allowed to communicate these feelings without punishment. They also have feelings of terror and abandonment. They need consistency and order in their lives. They want to know where they will live, who will take care of them, if they will be with their siblings, and if there will be enough money to live on. Children fear that if their parents stopped loving each other, they could stop loving them. Their need for love and reassurance is tremendous at this time. Children may also wonder what will happen on special days such as birthdays and holidays, whether both parents will come to school events, and whether the child will still have the same friends.

Custody and Parenting Partnerships

In the past, when parents separated, the mother was given custody of the children with visitation agreements for the father. Now both parents and the courts are seeking alternatives. Current belief is that neither fathers nor mothers should be awarded custody automatically. Custody should be awarded to the parent who is best able to provide for the children’s welfare. In some cases, children experience severe stress when living or spending time with a parent. Many fathers have demonstrated both their competence and their commitment to care for their children.

Often overlooked are the changes that may occur in the children’s relationships with other relatives, especially grandparents. Grandparents on the noncustodial side are often kept from their grandchildren, whereas those on the custodial side may be overwhelmed by their adult child’s return to the household with grandchildren.

Two other types of custody arrangements are divided custody and joint custody. Divided, or split, custody means that each parent is awarded custody of one or more of the children, thereby separating siblings. For example, sons might live with the father and daughters with the mother.

Joint custody takes one of two forms. In joint physical custody, the parents alternate the physical care and control of the children on a equitable basis while maintaining shared parenting responsibilities legally. This custody arrangement works well for families who live close to each other and whose occupations permit an active role in the care and rearing of the children. In joint legal custody, the children reside with one parent but both parents are the children’s legal guardians, and both participate in childrearing.