Recommendations for Selected Immunizations

Two additional vaccines are recommended for children and adolescents at high risk for particular diseases. In February 2006 a new rotavirus vaccine, RotaTeq, received a license from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for distribution in the United States. A second rotavirus vaccine, Rotarix, is licensed for use in Europe, and application to the FDA for use in the United States was made in late 2007. Rotavirus is one of the leading causes of severe diarrhea in infants and young children. A previous rotavirus vaccine was removed from the market in the late 1990s because of its association with intussusception. The new oral rotavirus vaccine is licensed for administration to infants at 6 to 12 weeks of age, with two additional doses administered at 4- to 10-week intervals but not after 32 weeks of age; the dose is 2 ml, and the product must be protected from light until administration (US Food and Drug Administration, 2006) (see Fig. 10-11, A).

A quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, Gardasil, has been approved and is recommended for female children and adolescents to prevent HPV-related cervical cancer. The vaccine is administered intramuscularly in three separate doses; the first dose in the series may be given at 11 to 12 years of age (minimum age 9 years), while the second dose is administered 2 months after the first, with the third dose being given 6 months after the first dose (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2007b) (see Fig. 10-11, B).

Immunizations that may be used in older children and adolescents in the future and that are being evaluated include vaccines for preventing diseases such as herpes simplex virus, human cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus. A vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus is currently being tested in animal models with apparent success. Others, such as the rabies vaccine, are discussed elsewhere in this text.

Reactions

Vaccines for routine immunizations are among the safest and most reliable drugs available. However, minor side effects do occur after many of the immunizations, and, rarely, a serious reaction may result from the vaccine.

With inactivated antigens, such as DTaP, side effects are most likely to occur within a few hours or days of administration and are usually limited to local tenderness, erythema, and swelling at the injection site; low-grade fever; and behavioral changes (drowsiness, fretfulness, eating less, prolonged or unusual cry). Rarely, more severe reactions may occur, especially with pertussis (see Table 10-6). Reactions to DTaP tend to be more severe if they occurred with a previous immunization.

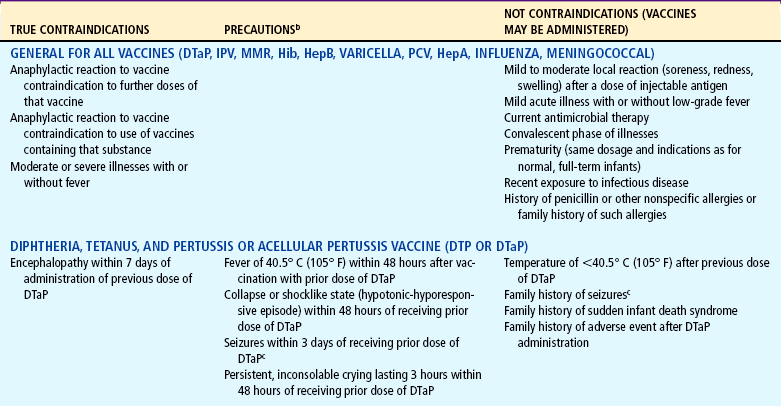

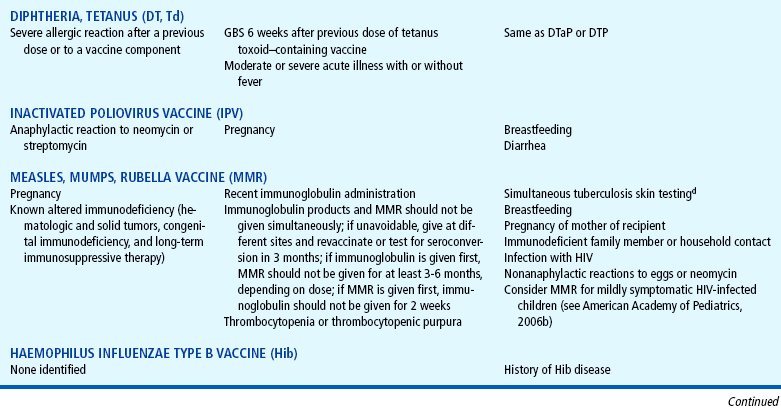

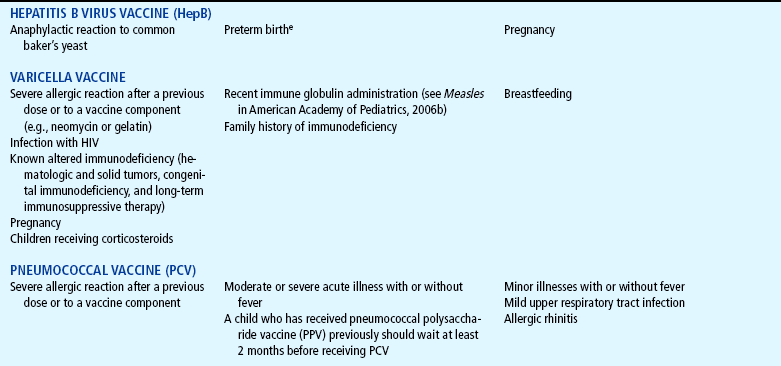

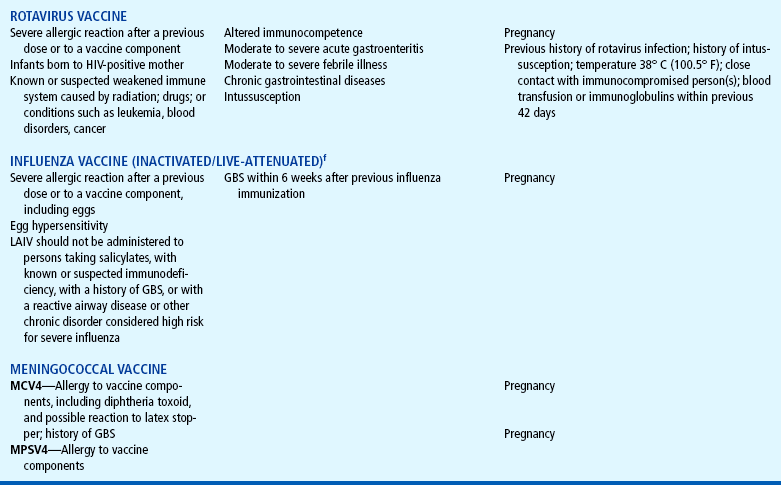

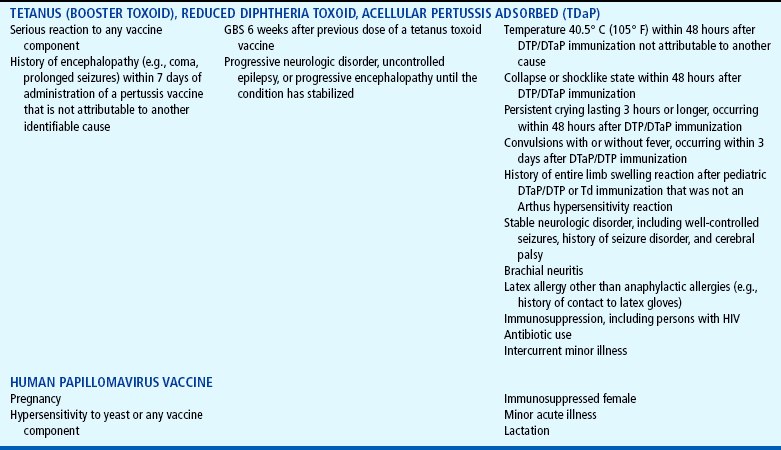

TABLE 10-6

Contraindications and Precautions to Vaccinationsa

HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; GBS, Guillain-Barré syndrome; PPD, purified protein derivative; LAIV, live-attenuated influenza vaccine.

aThis information is based on the recommendations of Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and those of Committee on Infectious Diseases (Red Book committee) of American Academy of Pediatrics. Sometimes these recommendations vary from those contained in manufacturer’s package inserts. For more detailed information, consult published recommendations of ACIP and American Academy of Pediatrics and manufacturer’s package inserts.

bEvents or conditions listed as precautions, although not contraindications, should be carefully reviewed. Benefits and risks of administering a specific vaccine to an individual under the circumstances should be considered. If risks are believed to outweigh benefits, vaccination should be withheld; if benefits are believed to outweigh risks (e.g., during an outbreak or foreign travel), vaccination should be administered. Whether and when to administer DTaP to children with proven or suspected underlying neurologic disorders should be decided on individual basis. It is prudent on theoretic grounds to avoid vaccinating pregnant women.

cAcetaminophen given before administering DTaP and thereafter every 4 hours for 24 hours should be considered for children with personal history or family history of convulsions in siblings or parents.

dMeasles vaccination may temporarily suppress tuberculin reactivity. If testing cannot be done the day of MMR vaccination, the test should be postponed for 4 to 6 weeks.

eBirth weight <2000 g (4.4 pounds) and unknown or hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive mother is not a contraindication for vaccination.

fSee James JM, Zeiger RS, Lester MR, and others: Safe administration of in. uenza vaccine to patients with egg allergies, J Pediatr 133(5):624-628, 1998.

Modified from American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Diseases, Pickering L, editor: Red book: 2006 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, ed 27, Elk Grove Village, Ill, 2006, The Academy.

Hib vaccine is one of the safest vaccines available but may be associated with low-grade fever and mild local reactions at the site of injection, which resolve rapidly. Fever (temperature >38.5° C [101.3° F]) may rarely occur.

A number of inactive components are incorporated in vaccines to enhance their effectiveness and safety. Some of these components include preservatives, stabilizers, adjuvants, antibiotics, and purified culture medium proteins to enhance effectiveness. A child may react to the preservative in the vaccine rather than the vaccine component; an example of this is the HepB vaccine, which is prepared from yeast cultures. Yeast hypersensitivity would preclude one from receiving that particular vaccine (Schuval, 2003). Trace amounts of neomycin are used to decrease bacterial growth within certain vaccine preparations, and persons with documented anaphylactic reactions to neomycin should avoid those vaccines. Most vaccine preparations now contain vial stoppers with a synthetic rubber to prevent latex allergy reactions. In the event that an individual has a severe reaction to a vaccine and subsequent immunizations are required, an allergist may be consulted to determine the best course of action (Schuval, 2003).

A commonly observed reaction includes localized erythema and induration, which may occur when the vaccine is not administered deeply enough into the muscle. This reaction can be prevented by ensuring that needle length is appropriate for the child’s muscle size. Although many vaccine preparations are commercially available in prepackaged form, the enclosed needle may not be of adequate length to penetrate the muscle in certain children (see Atraumatic Care box, p. 360, and Administration, below).

Unlike the inactivated antigens, live attenuated virus vaccines such as MMR multiply for days or weeks, and unfavorable reactions and vaccine-associated disorders can occur for 30 to 60 days. These reactions are usually mild, although reactions to rubella tend to be more troublesome in older children and adults.

Contraindications and Precautions

Nurses need to be aware of the reasons for withholding immunizations—both for the child’s safety in terms of avoiding reactions and for the child’s maximum benefit from receiving the vaccine. Unfounded fears and lack of knowledge regarding contraindications can needlessly prevent a child from having protection from life-threatening diseases. Issues that have surfaced regarding vaccines include the misconception that administering combination vaccines may overload the child’s immune system; the combined vaccines have undergone rigorous study in relation to side effects and immunogenicity rates following administration.

Parents must be given appropriate information regarding vaccine safety, benefits, and risks so they can make informed decisions regarding vaccinations for their children (Koslap-Petraco and Parsons, 2003; Fredrickson, Davis, Arnold, and others, 2004). The advantage of widespread media coverage on television and the Internet is that information is readily available at any given moment; the disadvantage may rest in the fact that information—rather, misinformation—from questionable sources is also readily available and may influence parents to make decisions that may have deleterious consequences for their children’s health. In one survey, parents’ fear of side effects was the most commonly expressed (52%) reason for vaccination refusal; other common reasons included the belief that the disease was not harmful (26%), religious beliefs (28%), and philosophical reasons (26%) (Fredrickson, Davis, Arnold, and others, 2004). The contraindications to the usual childhood vaccines are presented in Table 10-6. See also Family-Centered Care box.

Administration

The principal precautions in administering immunizations include proper storage of the vaccine to protect its potency and institution of recommended procedures for injection. The nurse must be familiar with the manufacturer’s directions for storage and reconstitution of the vaccine. For example, if the vaccine is to be refrigerated, it should be stored on a center shelf, not in the door, where frequent temperature increases from opening the refrigerator can alter the vaccine’s potency. For protection against light, the vial can be wrapped in aluminum foil. Periodic checks are established to ensure that no vaccine is used after its expiration date.

The DTaP vaccines contain the adjuvant alum to retain the antigen at the injection site and prolong the stimulatory effect. Because subcutaneous or intracutaneous injection of the adjuvant can cause local irritation, inflammation, or abscess formation, attention to excellent intramuscular injection technique must be used (see Atraumatic Care box, p. 360, and Table 10-7).

One of the most important features of injecting vaccines is adequate penetration of the muscle for deposition of the drug intramuscularly and not subcutaneously. The use of appropriate needle length is an essential component of administering vaccines. In two studies, the use of longer needles significantly decreased the incidence of localized edema and tenderness when vaccines were administered to a group of infants (Diggle and Deeks, 2000; Diggle, Deeks, and Pollard, 2006) (see Intramuscular Administration, Chapter 22).

The total series requires several injections, and every attempt is made to rotate the sites and administer the injections as painlessly as possible (see Intramuscular Administration, Chapter 22). When two or more injections are given at separate sites, the order of injections is arbitrary. Because allergic reactions can occur after injection of vaccines, appropriate precautions are taken (see Anaphylaxis, Chapter 25).

Nurses often administer vaccines and thus have the responsibility for adequately informing parents of the nature, prevalence, and risks of the disease; the type of immunization product to be used; the expected benefits and the risk of side effects of the vaccine; and the need for accurate immunization records. Referring to immunizations as “baby shots” and limiting the discussion to vague statements about the vaccines are unacceptable practices.

Another important nursing responsibility is accurate documentation. Each child should have an immunization record for parents to keep, especially for families who move frequently. Although immunization rates have increased significantly, health professionals should use every opportunity to encourage complete immunization of all children (see Community Focus box). Blank immunization records may be downloaded from a number of websites, including the Immunization Action Coalition,* which has vaccine information and records in a number of languages.

The following information is documented on the medical record: day, month, and year of administration; manufacturer and lot number of vaccine; and the name, address, and title of the person administering the vaccine. Additional data to record are the site and route of administration and evidence that the parent or legal guardian gave informed consent before the immunization was administered. Any adverse reactions after the administration of any vaccine are reported to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System.*

An additional source of vaccine information that must be given to parents (by law; National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act, 1986) before the administration of given vaccines is the vaccine information statement (VIS) for the particular vaccine being administered. Practitioners are required to fully inform families of the risks and benefits of the vaccines. VISs are designed to provide updated information to the adult vaccinee or parents or legal guardians of children being vaccinated regarding the risks and benefits of each vaccine. Questions regarding the information in the VISs should be answered by the practitioner. VISs are available for the following vaccines: anthrax, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, MMR, IPV, varicella, Hib, influenza, meningococcal, pneumococcal, rabies, smallpox, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, rotavirus, human papillomavirus, typhoid, HPV, HepA, and HepB. An updated VIS should be provided, and documentation in the patient’s chart should state that the VIS was given and include the publication date of the VIS. VISs are available from state or local health departments or from the Immunization Action Coalition* and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.†

In response to the concerns of manufacturers, practitioners, and parents of children with serious vaccine-associated injuries, the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 and the Vaccine Compensation Amendments of 1987 were passed. Basically, these laws are designed to provide fair compensation for children who are inadvertently injured and provide greater protection from liability for vaccine manufacturers and providers.

One survey found that a large percentage (65%) of children under the age of 2 years were not fully immunized in a large health maintenance organization population, perhaps because of the lack of coordinated immunization information. In addition, the study found that more than 51% had at least one immunization error and more than 20% had an unnecessary or incorrect immunization based on current recommendations (Mell, Ogren, Davis, and others, 2005). Therefore recommendations are in place to improve the overall effectiveness of the national vaccination program. It has been suggested that local or national computerized registries and improved record tracking systems be established to improve communication; additional recommendations include improving provider knowledge of immunization status and contraindications for administering vaccines and simplifying the immunization guidelines (Lee and Bernstein, 2005).

ATRAUMATIC CARE

ATRAUMATIC CARE

FAMILY-CENTERED CARE

FAMILY-CENTERED CARE COMMUNITY FOCUS

COMMUNITY FOCUS